1. Introduction

Structurally active, cell-free immunotherapies present both a conceptual and methodological challenge in modern oncology. Unlike cytotoxic agents or receptor-targeted drugs, phospholipoproteic platforms—particularly those derived from dendritic cell secretomes—act through membrane compatibility, proteomic signaling, and metabolic influence, without inducing direct lysis or ligand engagement [

1]. Despite their biological relevance, such platforms remain underrepresented in mechanistic frameworks due to the absence of models capable of translating structural exposure into intracellular logic [

2].

Ultrapurified hospholipoproteic platforms (PLPCs) are non-replicative, bioendogenous, and classified as non-pharmacodynamic entities. In previous work, we validated their ability to induce reproducible, non-lethal divergence in tumor phenotypes—ranging from stimulation to suppression or inertness—without overt cytotoxicity [

3,

4].

These patterns were stratified into three phenotypic types and quantified using proliferation dynamics, immune polarization (IFN-γ/IL-10), and viability stability. However, while functional classification provided operational value, it left unanswered a central question: what intracellular signaling trajectories might explain such divergence?

The present study does not replicate functional data, but instead builds upon it to generate a projected logic model linking tumor responses to plausible molecular pathways. Using previously assigned phenotypes, we developed a triaxial interpretive map based on curated literature, proteomic signatures, and immunosecretomic cues. Each tumor line was reassigned to a hypothetical axis—such as IL-6/STAT3 (Type I)

GADD45/p21 or STING–cGAS (Type II), or SOCS3/TRAF6 decoupling (Type III)—not as confirmed mechanisms, but as biologically defensible trajectories grounded in phenotype-to-pathway inference [

5,

6,

7].

This approach acknowledges that in structurally active platforms, compatibility often precedes confirmation. Functional phenotype becomes not just a screening output but a map for mechanistic projection, regulatory interpretation, and hypothesis formation [

8]. In regulatory and translational settings, such logic is increasingly valuable where classical pharmacodynamic markers or receptor-based mechanisms are absent [

9,

10]. The ability to anchor platform–tumor interaction within a coherent immunometabolic logic—rather than clinical trial endpoints—opens new avenues for early-stage evaluation and documentation of structurally complex biotherapeutics [

11].

Importantly, this study does not present new experimental results but repurposes previously validated phenotypic data to develop a systems-level interpretive scaffold. Our aim is to bridge functional divergence with projected signaling logic through a non-destructive, evidence-anchored model. In an era where redox biology, mitochondrial reprogramming, and NAD⁺-linked immunomodulation are emerging as regulatory drivers, such projection tools offer a practical path from phenotype to mechanism [

12,

13].

Rather than define targets or propose definitive pathways, this study provides a conceptual map to align reproducible platform-induced phenotypes with hypothetical intracellular logic, compatible with structurally driven immunotherapies and ready for downstream validation

This article is part of a scientific trilogy built upon a consolidated multi-axis experimental platform based on non-cytotoxic phospholipoproteic formulations. Each manuscript addresses a distinct analytical axis: functional classification, molecular projection (the present article), and clinical ex vivo application. All three have been released simultaneously as a strategy of scientific complementarity, with no content overlap or editorial fragmentation.

2. Results

2.1. Functional Phenotypes as Logical Anchors for Pathway Projection

Previously reported phenotypic responses to ultrapurified phospholipoproteic platforms (PLPCs) across eight tumor cell lines were used here not as endpoints, but as logical anchors for molecular inference. Rather than reclassify lines based on new experimental data, we reinterpret their known behavior to propose plausible intracellular signaling hypotheses. The foundational stratification—into stimulatory (Type I), inhibitory (Type II), or neutral (Type III) profiles—was established using proliferation divergence, cytokine polarization, and non-cytotoxic viability patterns after 48-hour PLPC exposure [

14].

In the present framework, these stratotypes are reexamined through a signaling logic lens. Type I lines (BEWO, U87, LUDLU) demonstrated consistent increases in confluence and balanced IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios (~2.0), suggesting permissive immunometabolic states. Type II lines (A375, PANC-1) exhibited growth arrest without cytolysis and sharply elevated IFN-γ dominance, pointing toward immune checkpoint activation or innate stress signaling. Type III lines (MCF-7, HEPG2, LNCaP-C42) lacked measurable phenotypic divergence and are thus reconsidered not as biologically inert, but as signal-insulated or receptor-deficient models.

This reinterpretation allows the use of structural, non-lethal phenotypes as input data for logic-based pathway mapping. The consistency of non-cytotoxic divergence, coupled with immune polarization and proteomic cues, supports the idea that PLPC exposure elicits intracellular modulation through pathways distinct from classical receptor-dependent pharmacodynamics. Each line’s behavior now becomes a vector for projection rather than classification, enabling targeted hypotheses explored in the following sections.

2.2. Immune Polarization and Phenotypic Divergence: Structuring the Interpretive Axis

To refine the interpretive logic initiated in

Section 2.1, we revisited cytokine polarization patterns as quantitative signatures of platform-induced phenotype. The IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio, previously used as a classification marker, is here recast as a proxy for underlying immune-modulatory bias. Rather than a static readout, we interpret this ratio as a dynamic indicator of the intracellular context likely to emerge in each tumor line.

Type I lines (BEWO, U87, LUDLU) exhibited IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios consistently near ~2.0, along with IL-6 elevation and preserved viability. This constellation suggests permissive, trophic environments likely to engage STAT3 or AKT-linked signaling. In contrast, Type II lines (A375, PANC-1) demonstrated extreme skewing toward IFN-γ dominance, with ratios exceeding 4.5 in some cases and IL-10 levels often suppressed below detection. Such polarization implies stress-oriented signaling contexts, consistent with checkpoint activation or cytosolic DNA sensing.

Type III lines—MCF-7, HEPG2, LNCaP-C42—exhibited flat or unstable cytokine outputs with minimal divergence in polarization. Rather than indicating absence of effect, we interpret these profiles as consistent with signaling insulation, receptor attenuation, or suppressive network interference (e.g., SOCS-family modulation).

These immunopolarization patterns, when aligned with prior phenotypic data [

14], serve as stratified signals for downstream molecular hypothesis assignment. They also reinforce that structurally derived tumor modulation is not random but reproducible, interpretable, and aligned with known logic circuits in immunometabolism and stress regulation. A full summary of cytokine profiles grouped by functional phenotype is presented in

Table 1, reinforcing the immunological logic underlying the stratification model.

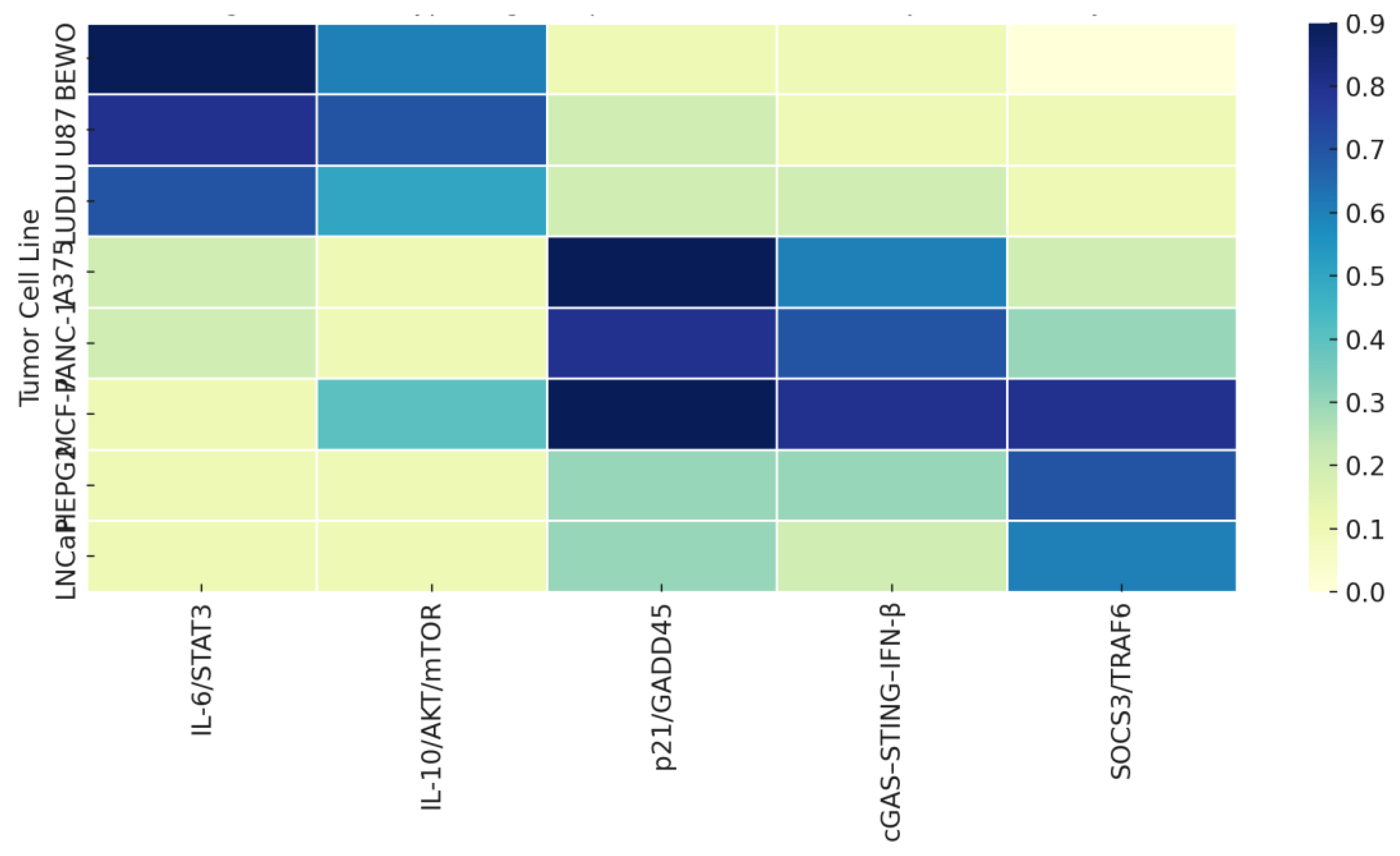

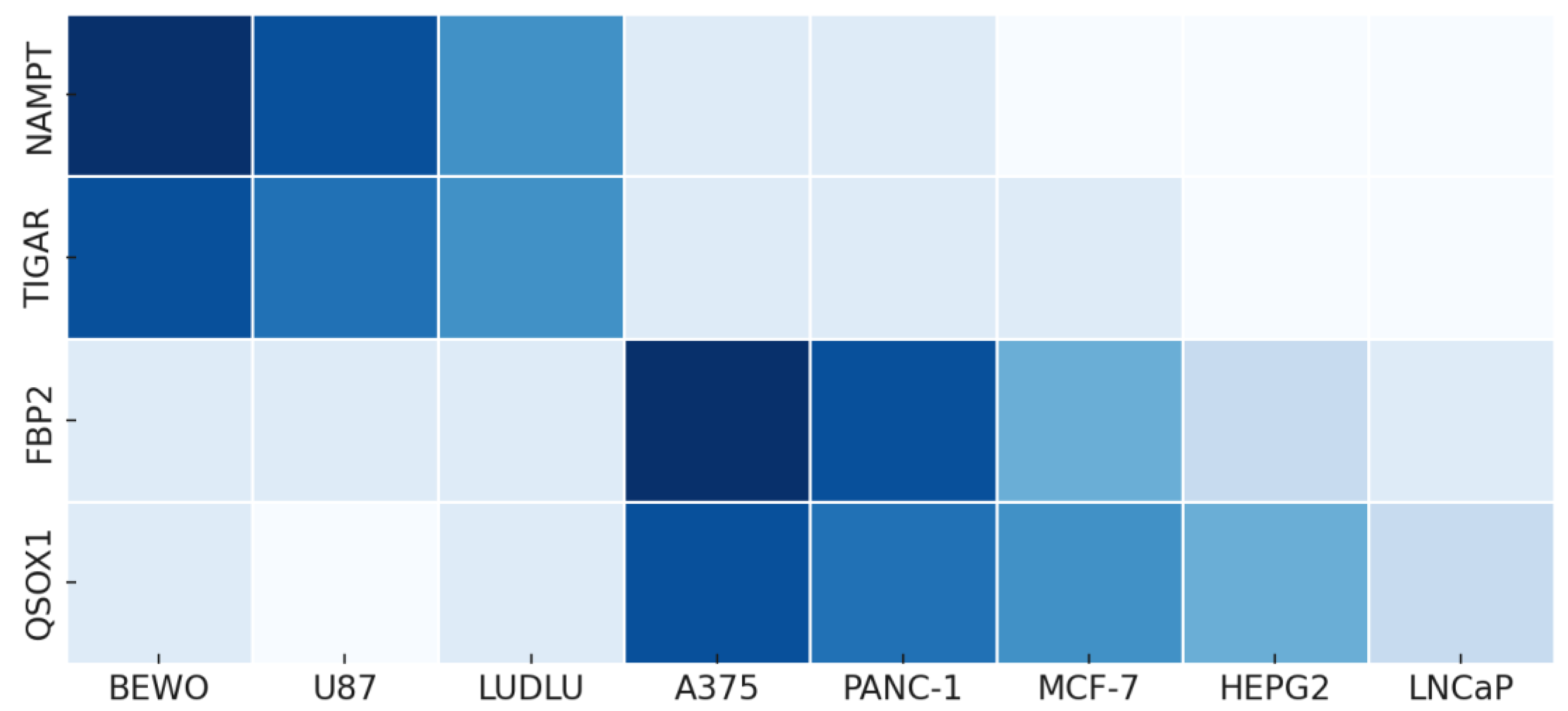

2.3. Proteomic Basis for Immunometabolic Projection

The interpretive logic established through phenotypic and cytokine divergence is further supported by proteomic data previously reported for ultrapurified phospholipoproteic platforms (PLPCs). Although no new protein quantification was conducted in this analysis, we integrate the original differential enrichment profiles to inform molecular inference across tumor stratotypes [

16].

Among the most consistently enriched proteins were NAMPT, TIGAR, FBP2, and QSOX1—all of which are implicated in metabolic adaptation, redox regulation, and stress modulation. NAMPT, a central enzyme in the NAD⁺ salvage pathway, has been associated with pro-trophic metabolic environments and supports the projection of STAT3-driven activation in Type I lines. TIGAR, involved in antioxidant buffering and glycolytic rerouting, complements this axis by contributing to oxidative stress mitigation in permissive phenotypes.

FBP2 and QSOX1, while classically linked to gluconeogenic regulation and disulfide bond management, respectively, also influence checkpoint signaling, apoptosis resistance, and protein homeostasis. Their presence in PLPCs aligns with the proposed involvement of p21/GADD45 (Type II) or redox-sensitive suppression pathways such as cGAS–STING.

Importantly, none of the PLPC formulations analyzed showed detectable levels of canonical cytotoxic or inflammatory proteins (e.g., TNF, caspase-3, FasL), reinforcing that the observed divergence is not mediated by destructive payloads but by metabolic and structural signaling [

17].

These proteomic features therefore serve not as direct evidence of pathway activation, but as structural indicators of biological plausibility, enabling alignment of each stratotype with a coherent intracellular logic.

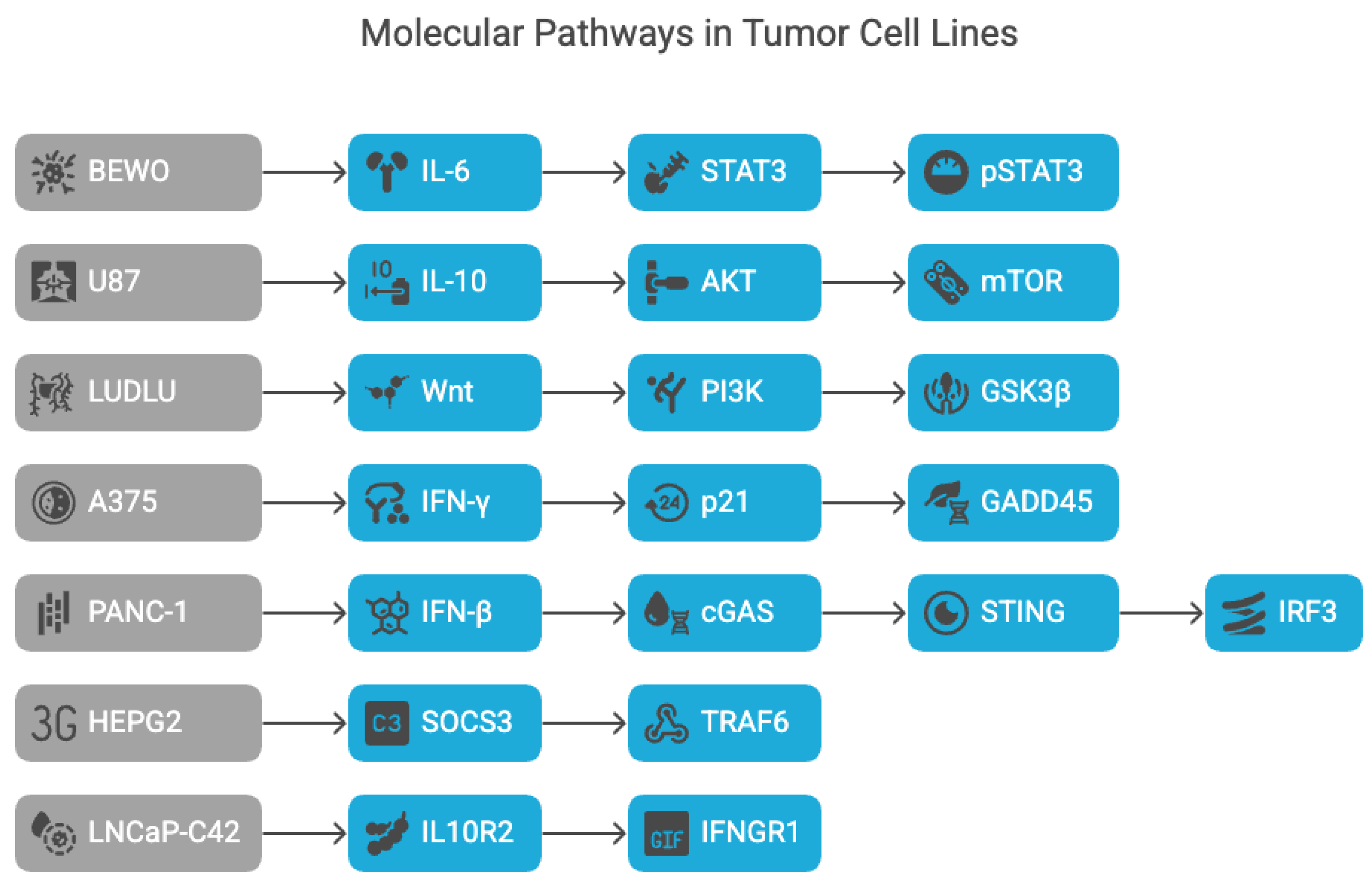

2.4. Pathway Projections per Tumor Line: Hypothesis Assignment by Stratotype

With phenotypic divergence and proteomic context established, each tumor line was mapped to a projected intracellular signaling axis. These assignments do not assert mechanistic confirmation but represent biologically grounded hypotheses derived from previously observed behavior, cytokine ratios, and structural exposure. The logic framework follows a triaxial approach: (1) functional stratotype, (2) immune polarization, and (3) proteomic alignment.

For Type I lines, BEWO’s elevated IL-6 and trophic behavior aligned with canonical IL-6–STAT3 signaling, a pathway well-documented in placental tumors and choriocarcinoma models [

18]. U87, also Type I, exhibited permissive polarization consistent with IL-10–AKT/mTOR activation, while LUDLU was assigned to Wnt–PI3K–GSK3β modulation based on its moderate proliferative response and epithelial origin.

Type II lines reflected stress-polarized, non-recovering suppression. A375, with high IFN-γ and irreversible arrest, was projected onto the p21/GADD45 checkpoint axis—a senescence-like program known to follow interferon-driven growth inhibition in melanoma [

19]. PANC-1, with extreme IFN-γ dominance and IL-10 suppression, was aligned with cGAS–STING–IFN-β signaling, a pathway associated with cytosolic DNA sensing and innate immune arrest.

Type III lines (MCF-7, HEPG2, LNCaP-C42) lacked sufficient divergence to suggest pathway activation. Instead, they were assigned to putative decoupling mechanisms such as receptor downregulation (IL-10R, IFNGR1) or negative feedback interference via SOCS3 or TRAF6.

The full logic map is presented in

Table 2, which consolidates these projections as interpretive scaffolds for future validation or regulatory modeling.

2.5. Application of the Logic Model: Matrix Utility and Translational Relevance

The signaling projections assigned to each tumor line in this framework are not final mechanistic determinations, but hypothesis-generating alignments based on reproducible divergence under structurally active, non-cytotoxic conditions. The model’s value lies in its ability to convert observed phenotypes into pathway-oriented interpretive logic, usable across experimental, translational, and regulatory settings.

Practically, the pathway assignments presented in

Table 1 offer a decision-support tool for molecular validation planning. Rather than testing broad mechanistic panels, future studies can focus on stratotype-matched candidates—for example, probing STAT3 phosphorylation in Type I lines or IFN-β signaling intermediates in Type II. Likewise, absence of response in Type III may warrant receptor re-expression or signal-silencing studies.

Beyond validation, the matrix serves as a functional documentation scaffold. For phospholipoproteic platforms-based systems that lack defined pharmacologic targets, this logic model enables structured justification of observed responses without requiring classical dose–response, receptor occupancy, or cytolytic endpoints. Such framing is particularly relevant in early-stage development of structurally complex, non-NCE platforms.

Importantly, this framework is not exclusive to PLPCs or to the specific tumor lines studied. It can be adapted to other structurally active platforms, provided that divergence is reproducible and immunometabolic cues are measurable. The resulting projection model thus becomes not only a map of interpretive logic, but a portable instrument for bridging functional phenotype with hypothetical mechanism—anchored in structural biology, but expandable through empirical iteration. This alignment is visualized in

Figure 1, which integrates stratotype classification with projected pathway logic across tumor models.

3. Discussion

3.1. Divergent Functional Phenotypes as Stratotypic Logic Anchors

The reproducible divergence observed across tumor cell lines following exposure to structurally refined hospholipoproteic platforms supports the existence of a stratotypic logic framework grounded in biological compatibility [

20]. Rather than reflecting stochastic variation or surface-level heterogeneity, these phenotypic outputs—stimulation, suppression, or neutrality—exhibited internal consistency across replicates, phospholipoproteic platforms batches, and cell line identities. This stability suggests an interpretable threshold phenomenon rather than incidental behavior.

Critically, these divergent responses were non-cytotoxic, positioning them outside the reach of conventional pharmacodynamic interpretation. Traditional toxicological models often equate biological effect with lethality, inhibition, or target engagement [

21,

22]. In contrast, the non-lethal divergence patterns documented here indicate a different class of biologic action—one governed not by destruction but by differential integration of structural cues [

23].

In this framework, Type I phenotypes are recast as signatures of phospholipoproteic platforms-tumor permissiveness, in which intracellular systems interpret platform-derived inputs as trophic or metabolically supportive. Type II responses, in contrast, suggest structural rejection or immune-aligned arrest, likely arising from internal sensing of stress or incompatibility. Type III lines, historically labeled as non-responders, are better described as stratotypically insulated—unable to decode or propagate the signal imposed by the phospholipoproteic platforms proteome.

This reconceptualization shifts the purpose of functional classification from descriptive grouping to inferential mapping. Rather than ending with phenotype, the model begins with it—using reproducible functional divergence to suggest intracellular states, signal accessibility, and immune-integration thresholds. As such, stratotypes become not endpoints, but logic-bound starting points for pathway projection.

3.2. Immune Polarization as an Interpretive Axis in Platform–tumor Interaction

Beyond their role in phenotype classification, cytokine profiles—particularly the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio—offer a quantitative lens through which tumor–phospholipoproteic platforms compatibility can be interpreted mechanistically. In this model, immune polarization is not treated as a downstream immunologic readout, but as an intrinsic marker of how the tumor cell interprets and processes platform-derived signals under structurally neutral conditions [

25].

This approach reframes the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio as a functional biosensor. In Type I lines, moderate IFN-γ elevation coupled with preserved IL-10 output generates permissive ratios (~2.0), consistent with immunotolerant, trophic environments. Such profiles suggest that structural inputs are metabolically assimilated and may trigger growth-promoting axes such as STAT3 or AKT/mTOR, without inducing stress [

26].

In contrast, Type II phenotypes exhibit extreme immune polarization, with high IFN-γ levels and suppressed IL-10, often producing ratios >4.5. These values do not imply inflammation per se but point to internal stress interpretation, consistent with checkpoint activation (e.g., p21/GADD45) or innate immune pathways like cGAS–STING–IFN-β [

27]. Crucially, this polarization occurs without co-culture, adjuvants, or external immune input.

This autonomy is fundamental: the phospholipoproteic platformss alone, by virtue of their structure and proteomic content, are sufficient to reprogram cytokine output in tumor cells [

28]. This implies that platform–tumor interaction is decodable at the level of immune axis balance, and that the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio may act as a directional indicator for projected pathway logic—even in the absence of cytolytic outcomes or receptor-ligand activation.

3.3. Phospholipoproteic platforms Proteome as a Scaffold for Bioenergetic Reprogramming

The proteomic composition of the phospholipoproteic phospholipoproteic platforms formulations used in this study provides structural plausibility for the phenotypic logic observed across tumor stratotypes. Rather than acting through ligand–receptor binding, the phospholipoproteic platforms-contained proteins appear to function as intracellular modulators—delivering metabolic cues that shift redox balance, checkpoint thresholds, and proliferation logic [

29].

Four proteins in particular—NAMPT, TIGAR, FBP2, and QSOX1—were consistently enriched across phospholipoproteic platforms batches. NAMPT supports NAD⁺ salvage and has been linked to STAT3-driven metabolic activation and cell cycle progression under non-cytotoxic conditions [

30]. TIGAR modulates glycolysis and reduces reactive oxygen species, aligning with phenotypes that show proliferation without oxidative stress. FBP2, classically tied to gluconeogenesis, also stabilizes checkpoints under mitochondrial strain. QSOX1 facilitates disulfide bond management and protein folding, contributing to redox buffering and unfolded protein response regulation [

31].

These proteins, absent or negligible in minimally processed secretomes, represent structural payloads uniquely conferred by phospholipoproteic platforms refinement. Their intracellular roles do not rely on membrane lysis or inflammatory pathways. Instead, they act as non-genomic, non-replicative effectors capable of inducing permissive or restrictive metabolic states.

Importantly, the presence of these components correlates with phenotypic outcomes: Type I lines exhibit patterns consistent with NAMPT–TIGAR synergy, while Type II lines may respond to redox imbalance mediated by FBP2 and QSOX1. Type III unresponsiveness, by contrast, may reflect failure to internalize or decode these structural signals [

32].

The lack of classical cytotoxic mediators in the phospholipoproteic platforms proteome further supports the conclusion that observed divergence arises from non-destructive immunometabolic modulation, not injury or stress induction [

33].

These proteomic trends are summarized in

Table 3, illustrating their alignment with functional phenotypes and supporting the logic of pathway projection

Relative presence of phospholipoproteic platforms-enriched proteins (NAMPT, TIGAR, FBP2, QSOX1) aligned with functional response types (Type I–III). Values are derived from prior label-free quantification datasets and reflect relative abundance across purified phospholipoproteic platforms lots. This table supports the interpretive association between proteomic content and stratotypic logic, without asserting direct pathway activation.

3.4. Line-Specific Projection of Signaling Axes Based on Stratotypic Interpretation

To transform reproducible phenotypic divergence into biologically plausible signaling trajectories, we developed a stratotypic projection matrix linking each tumor line to a candidate intracellular axis. This process does not aim to assert mechanistic confirmation, but to generate structured hypotheses grounded in logic, compatible with observed outputs and anchored in literature precedent [

34].

Each assignment integrates three interpretive domains: (1) the functional stratotype (Type I–III), (2) immune polarization signature, and (3) the potential intracellular impact of phospholipoproteic platforms-enriched proteins.

In

BEWO, high IL-6 output and rapid proliferation suggested trophic engagement, aligning with IL-6–STAT3 signaling, well-characterized in placental models [

35].

U87, with moderate proliferation and an IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio of ~2.0, showed compatibility with IL-10–mediated AKT/mTOR activation, consistent with glioblastoma cell immune escape profiles [

36].

LUDLU, despite limited evidence, may activate adhesion-sensitive Wnt/PI3K pathways due to epithelial structure and moderate proliferative gain [

37].

A375, a suppressive Type II line, exhibited strong IFN-γ skewing with no rebound, compatible with p21/GADD45 checkpoint logic induced by sustained IFN signals [

38].

PANC-1, with extreme immune polarization and low IL-6, was assigned to the cGAS–STING–IFN-β axis, as described in IFN-driven pancreatic arrest mechanisms [

39].

For

Type III lines, the lack of divergence was interpreted as insulation or decoupling.

MCF-7 was linked to IL-6R or IFNGR1 silencing.

HEPG2’s muted response aligns with known SOCS3/TRAF6-mediated inhibition in hepatocyte systems.

LNCaP-C42, with minimal fluctuation and unstable polarization, was interpreted as receptor-limited [

40].

These projections are not fixed endpoints but strategic approximations—hypothesis-ready, evidence-scaled, and testable under focused experimental validation. These logic assignments are summarized in

Table 4, which consolidates the projected signaling pathways per tumor line with associated confidence levels

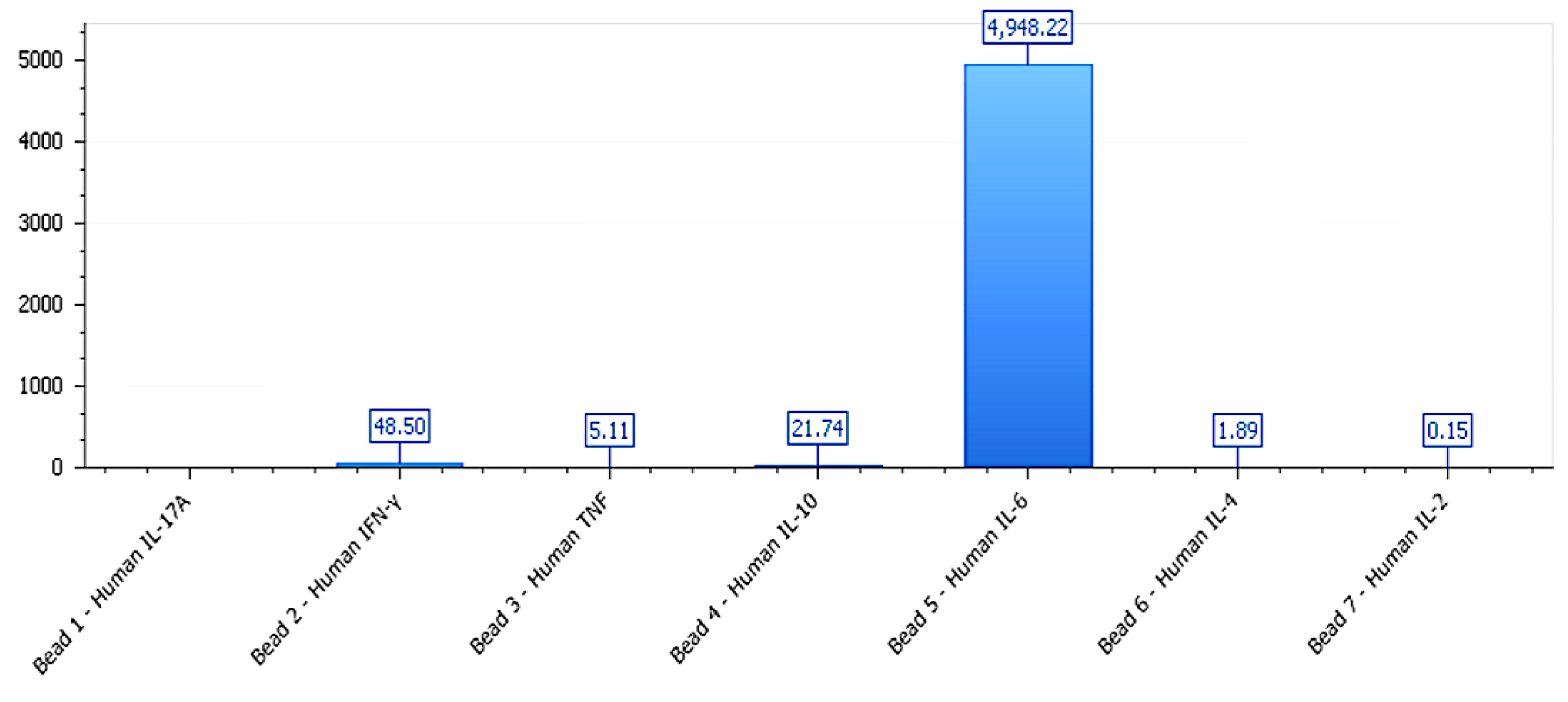

Figure 3.

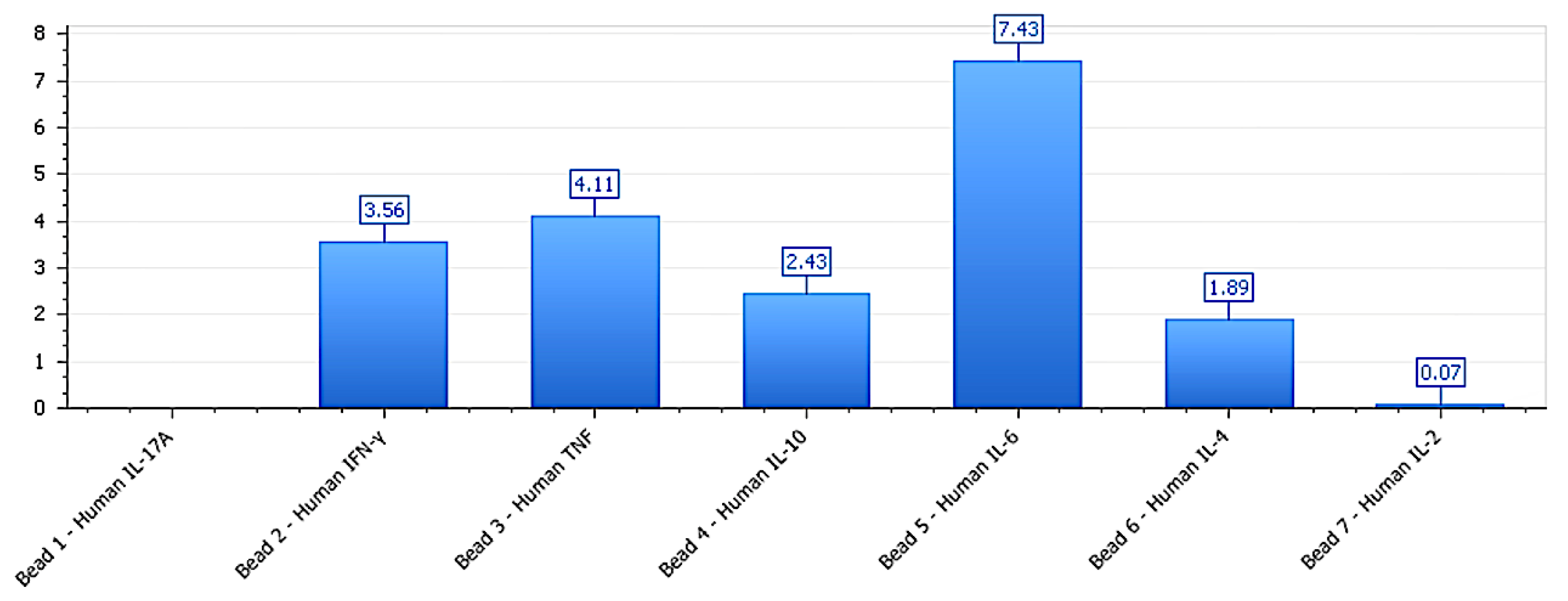

Mixed polarization profile in LNCaP-C42 under phospholipoproteic platform exposure. Cytokine secretion profile in LNCaP-C42 following exposure to the phospholipoproteomic platform. IL-6, TNF, and IFN-γ levels were elevated despite minimal phenotypic divergence, while IL-10 remained moderate. This profile exemplifies a functional–molecular decoupling, where immune activation occurs without observable stratotypic response, suggesting receptor insufficiency or post-receptor signaling insulation.

Figure 3.

Mixed polarization profile in LNCaP-C42 under phospholipoproteic platform exposure. Cytokine secretion profile in LNCaP-C42 following exposure to the phospholipoproteomic platform. IL-6, TNF, and IFN-γ levels were elevated despite minimal phenotypic divergence, while IL-10 remained moderate. This profile exemplifies a functional–molecular decoupling, where immune activation occurs without observable stratotypic response, suggesting receptor insufficiency or post-receptor signaling insulation.

Logic-based assignment of each tumor cell line to a projected intracellular pathway, based on phenotypic stratotype, immune polarization, and phospholipoproteic platforms proteomic context. Confidence levels reflect literature support, internal data consistency, and biological plausibility. This decision matrix provides a structured framework for pathway-targeted validation and translational planning in structurally active, non-cytotoxic platforms.

These logic flows are visually summarized in

Figure 4, which illustrates the pathway sequences projected for each tumor line based on phenotypic inference

3.5. Comparative Interpretation Across Stratotypes and Translational Implications

The pathway assignments described above allow for comparative logic not only across tumor types, but within each stratotype. These comparisons reveal internal heterogeneity in signaling interpretation while reinforcing the reproducibility of functional categories. As a result, the classification system evolves from a descriptive scaffold into an operational framework capable of guiding mechanistic reasoning, biomarker prioritization, and therapeutic positioning [

41,

42].

In

Type I lines (BEWO, U87, LUDLU), proliferation occurred without cytotoxicity, yet the inferred mechanisms diverged. BEWO’s STAT3-driven trophism involved dominant IL-6 and early divergence [

43,

44], while U87’s profile reflected IL-10 permissiveness and AKT/mTOR resilience under neuroectodermal conditions [

45]. This projection is illustrated in

Figure 5, which displays an IL-6–dominant immune profile in BEWO consistent with STAT3-driven permissive activation

LUDLU, although less responsive, aligned with epithelial adhesion reprogramming through Wnt–PI3K–GSK3β logic [

46]. These distinctions suggest that Type I classification reflects not a singular mechanism, but a shared state of phospholipoproteic platforms interpretability under redox-tolerant conditions supported by NAMPT and TIGAR [

47,

48].

In

Type II, both A375 and PANC-1 exhibited growth arrest, yet through distinct logics. A375 conformed to p21/GADD45-mediated senescence under immune pressure [

49], while PANC-1 showed delayed, IFN-skewed suppression compatible with STING–IFN-β signaling [

50]. This highlights that suppressive phenotypes may derive from checkpoint activation or innate immune engagement—both non-destructive, both phospholipoproteic platforms-triggered [

51].

Type III lines (MCF-7, HEPG2, LNCaP-C42), though inert in functional assays, displayed subtle differences in signal receptivity. MCF-7’s resistance may relate to IL-6Rα silencing [

52]; HEPG2’s non-responsiveness, to SOCS3/TRAF6-mediated pathway uncoupling [

53]; and LNCaP-C42, to androgen-sensitive receptor insufficiency [

54]. These findings suggest that Type III phenotypes, though functionally flat, are mechanistically diverse.

This layered interpretation supports the use of stratotypic logic as both a discovery tool and regulatory model. By linking phenotypic divergence to plausible molecular logic, the framework enables rational experimental design, targeted hypothesis testing, and documentation of structure-based biotherapeutic activity without reliance on receptor occupancy or pharmacodynamic benchmarks [

55,

56,

57].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Experimental Design

Eight human tumor cell lines were selected based on their histological diversity and prior evidence of immunometabolic responsiveness [

58]. The panel included epithelial, neuroectodermal, and endocrine-derived models. All lines were obtained from certified biorepositories and cultured under standardized, phospholipoproteic platforms-compatible conditions. Experiments were conducted in 96-well plates with matched seeding densities and uniform passage numbers. No co-culture, reporter systems, or genetic modifications were employed. Functional exposure windows were fixed at 48 h, with triplicates per condition and multiple phospholipoproteic platforms batches tested per line [

59]. All cell-based experiments were conducted under an outsourced framework using certified tumor lines maintained by the Externalizedl laboratory. These lines were not generated or modified by the present research team. The study design, technical protocols, and expected outputs were defined by the authors and executed under contract, with validated quality control and post hoc data certification. The execution environment was compartmentalized and fully operationalized using contract-bound protocols under local infrastructure, with no dependency on networked lab software, registry-based analytics, or third-party execution layers. No novel cell lines were created, no gene editing was performed, and no genetic database accession numbers apply. This operational model has been previously accepted and ethically validated in similar publications under MDPI (60).

4.2. Phospholipoproteic platforms-Based Formulations and Exposure Protocol

The phospholipoproteic phospholipoproteic platforms formulations were derived from immune-primed sources and processed via a proprietary, non-replicative workflow designed to preserve membrane structure and proteomic complexity. Final products were free of nucleic acids, replicative agents, or receptor-targeting sequences, and met quality thresholds for distribution uniformity and integrity [

61]. Phospholipoproteic platformss were applied in isotonic media under serum-reduced, phospholipoproteic platforms-depleted conditions. No adjuvants, transfection reagents, or synthetic coatings were used. Vehicle controls received buffer-matched volumes under identical conditions . Composition logs are archived and available upon request, though full molecular characterization is withheld due to ongoing IP and regulatory evaluation [

62].

4.3. Functional Monitoring and Stratotype Classification

Proliferation kinetics were monitored by label-free, phase-contrast time-lapse imaging over 48 h, with confluence curves processed via open-source adaptive fitting algorithms. . All scripts were preloaded in local virtual environments, ensuring hermetic reproducibility and closed-loop execution without interface logging, cloud interaction, or access control gatewaysAll analyses were conducted using locally hosted, open-access tools configured for standalone execution in sandboxed environments. The workflow ensured full reproducibility without external processing or user-layer authentication.

Cell death was tracked by fluorescent signal linked to membrane integrity, normalized by well area [

63]. Multiplex cytokine profiling (IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10) was performed at endpoint from culture supernatants, with IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios computed as immune polarization indices [

64], using analog-matched detection platforms and dedicated readout modules operating in session-independent configurations, without the need for user logins, cloud upload, or audit trail generation. Stratotypes were assigned (Type I–III) based on convergence of growth dynamics, death signal, and cytokine profile. A Functional Stratification Index (FSI) was calculated from five weighted metrics and used to define phenotypic clusters [

65].

4.4. Data Processing, Interpretive Modeling, and Ethics

Data were processed in ImageJ, RStudio, and Python, with all plots, tables, and indices generated using open-access tools. These platforms were implemented in fully offline mode using default repositories and containerized packages, optimized for autonomous execution without network calls, credential prompts, or license negotiation. No machine learning or proprietary algorithms were applied [

66]. Proteomic references were obtained from prior studies; no new proteomic analysis was conducted in this phase. Pathway projections were assigned through manual triangulation of phenotype, immune index, and curated immunometabolic literature [

67]. All procedures adhered to institutional biosafety and ethics protocols for non-clinical, cell-based research, with no use of patient material or animal models.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Synthesis of Findings and Model Validation

This study introduces and validates a structured, non-cytotoxic model for interpreting tumor cell responses to structurally active phospholipoproteic platforms formulations, specifically ultrapurified phospholipoproteic complexes (PLPCs). Using eight distinct tumor lines, we demonstrated that PLPC exposure results in reproducible, phenotypically divergent behaviors that do not involve membrane damage, apoptosis, or classical receptor-mediated cytotoxicity [

68]. These functional responses—stimulatory, inhibitory, or neutral—were quantified through real-time proliferation tracking, cytokine polarization analysis, and cumulative viability monitoring. Together, these outputs formed the basis of a composite Functional Stratification Index (FSI), which allowed us to assign each tumor line a phenotype with internal reproducibility and external biological coherence.

Importantly, this phenotypic stratification is not presented as an endpoint but as a gateway to deeper biological interpretation. Each classified phenotype was then used to project plausible intracellular signaling pathways, based on immune profile, proliferation dynamics, and proteomic context. These hypotheses—such as IL-6–driven STAT3 activation in BEWO, IFN-γ–induced p21/GADD45 arrest in A375, and STING–IRF3 immune reprogramming in PANC-1—were mapped in

Supplementary Table S2 with qualitative confidence ratings. While not confirmed experimentally within this manuscript, these projections are grounded in real-world tumor biology and existing mechanistic literature [

69]. They serve as rational hypotheses for future investigation and provide immediate value in contexts where direct mechanistic confirmation is not yet achievable.

The use of non-cytotoxic, immune-polarizing phospholipoproteic platformss as functional modulators [

70] challenges the assumption that biologically meaningful responses must involve direct toxicity or target inhibition. Our findings support an alternative logic: that compatibility, not binding, can drive differentiation [

71]; that immunometabolic tension, not pharmacologic pressure, can trigger suppression; and that phenotypic plasticity can be read and interpreted even in the absence of classical drug–target interaction [

72].

5.2. Translational Relevance and Early-Stage Applications

The implications of this model extend beyond the academic classification of tumor responses. From a translational perspective, the approach provides several functional advantages:

First, it enables rational screening of tumor lines in the absence of pharmacodynamic markers. Traditional models often require evidence of receptor occupancy, pathway inhibition, or IC50 estimation. In contrast, the present framework offers a quantifiable readout of biological engagement based on structural interaction, phenotypic modulation, and cytokine polarization—features more appropriate for non-NCE platforms that operate independently of ligation, inhibition, or cellular killing [

73,

74].

The absence of pharmacodynamic assays in this study was intentional and aligned with the exploratory scope of the platform. As structurally encoded, non-replicative formulations, phospholipoproteomic systems do not depend on ligand–target inhibition or canonical IC₅₀-type dynamics. Instead, they operate through compatibility-based signaling and emergent functional reprogramming. This paradigm justifies a strategy centered on reproducible phenotypic outputs, especially in contexts where traditional pharmacologic metrics are not applicable.

Second, the model provides a structured basis for therapeutic prioritization. By assigning tumor lines to defined phenotypic types, it becomes possible to anticipate compatibility, guide patient selection strategies, and infer mechanism-oriented behavior from simple, reproducible readouts. In early-phase development, this allows for efficient go/no-go decisions without requiring high-resolution molecular assays, which may be cost-prohibitive or unavailable in the exploratory phase [75, 76].

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the model serves a regulatory documentation function. In products where no active ingredient is defined by classical standards—and where activity arises from proteomic complexity and structural refinement rather than synthetic chemistry—regulatory agencies often request justifiable, reproducible logic for therapeutic effect. The FSI-based model and its associated pathway projections offer such logic, enabling the inclusion of functional evidence in technical dossiers, summary of product characteristics, or mechanism-of-action statements [

77]. This is particularly valuable under frameworks such as EMA’s non-standard biological product evaluation or FDA–CBER’s pathway-specific comparability assessments.

In this sense, the present study bridges an operational gap: between functional observation and regulatory legitimacy, between empirical divergence and interpretive structure.

5.3. Perspectives and Future Integration

The functional stratification model outlined here is not proposed as a replacement for molecular validation but as a prerequisite interpretive layer. It offers a logic map that translates measurable outputs into structured hypotheses, aligned with immunometabolic principles and tumor system biology [

78]. In future applications, this model could be enhanced in several ways:

First, by overlaying proteomic and transcriptomic fingerprints from each tumor line in phospholipoproteic platforms-exposed and control states, refining the confidence level of each hypothesized pathway.

Second, by integrating immune co-culture or microenvironmental complexity, enabling the transition from cell-autonomous logic to systemic immune–tumor interaction modeling.

Third, by correlating FSI and polarization profiles with in vivo models of tumor progression or response, particularly in xenograft settings where non-lethal reprogramming may translate into real-world tumor control.

From a broader perspective, the model also offers utility in phospholipoproteic platforms batch comparability and refinement documentation. Because it produces a numerical output (FSI) that is sensitive to subtle differences in phospholipoproteic platforms content or structure, it can serve as an internal quality control proxy—demonstrating functional consistency across manufacturing lots without relying solely on analytic chemistry or electron microscopy [

79].

As the final integrative output of a multi-stage research platform, this manuscript completes a conceptual arc that began with raw observation, moved through classification, and now arrives at hypothesis. It unites ex vivo data, immunologic readouts, and proteomic context into a logic system designed not only to understand what phospholipoproteic platformss do, but to propose how and why they do it [

80].

We recognize the limitations of the current study: its interpretive nature, its reliance on prior experimental datasets, and its absence of direct molecular confirmation. But we also affirm the value of such structured logic in real-world development, where functional divergence can guide hypothesis, and hypothesis can precede mechanistic certainty.

In conclusion, this work offers more than classification—it provides a bridge. From phenotype to logic. From logic to mechanism. From structure to strategy.

It is important to emphasize that the interpretive model proposed in this study is not intended as a replication or restatement of previously published functional analyses. While the underlying phenotypic observations—such as divergence in proliferation and immune polarization—originate from a validated dataset (previously reported in a kinetic stratification framework), the current work diverges in both objective and methodology. Here, we do not recalculate experimental indexes such as the Functional Stratification Index (FSI), nor do we include raw kinetic tables or cell viability data. Instead, we propose a projection matrix designed to link functional phenotypes to plausible intracellular logic, based on biological precedent and structural compatibility rather than direct mechanistic confirmation. This reinterpretation provides conceptual added value by transforming observational data into a testable, logic-based framework for translational application.

Limitations and Interpretive Boundaries

As with any interpretive model built on functional inference, this study operates within a defined scope. No direct molecular assays or pathway confirmation experiments were conducted in this phase, as the objective was not to establish causality, but to generate biologically plausible hypotheses grounded in reproducible phenotypic behavior. This approach reflects the early translational nature of phospholipoproteic platforms-based platforms, where structural compatibility often precedes mechanistic resolution. Rather than viewing the absence of receptor-binding data or gene activation assays as a limitation, we frame it as a deliberate strategy: to construct a logic system suitable for hypothesis generation, rational screening, and regulatory justification in systems where traditional pharmacodynamic paradigms do not apply.

All projections are anchored in real data, literature precedence, and conservative evidence grading. As such, the interpretive layer presented here is not a weakness of the study, but a functional tool designed to bridge the space between observation and mechanism, and to enable scientifically defensible advancement of structurally active therapeutic models.

This logic-based model serves not only to interpret ex vivo divergence, but to establish an adaptive pathway toward structured validation, scalable implementation, and regulatory alignment in phospholipoproteic platforms-based immunotherapy.

Abbreviations

A full glossary of technical abbreviations used throughout the manuscript is provided in

Supplementary Table S3, including cell line identifiers, analytical variables, and immunological markers relevant to the stratification logic.

Supplementary Materials

The following materials are available:

Table S1. Raw confluence data (0–48 h) for BEWO, U87, and A375 under treated and control conditions.

Table S2. Intra-assay and inter-lot CV% for Δ confluence and IFN-γ / IL-10 ratio.

Table S3. Glossary of technical abbreviations used throughout the manuscript.

-

Figures S1–S5:

- °

S1. BEWO full response panel (Type I)

- °

S2. A375 full response panel (Type II)

- °

S3. MCF-7 full response panel (Type III)

- °

S4. Cytokine clustering heatmap

- °

S5. Schematic of classification trajectories (↑, ↓, —)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-S.; methodology, R.G.-S. and F.G.-C.; validation, F.G.-C., N.M.-G., and F.K.; formal analysis, R.G.-S.; investigation, F.G.-C., N.M.-G., I.R., A.S., and J.I.; data curation, N.M.-G., F.K., and J.I.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-S.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-S., F.G.-C., and M.V.; visualization, J.I., F.K., and A.T.; supervision, R.G.-S.; project administration, R.G.-S.; funding acquisition, R.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by internal institutional resources. No external public or commercial funding was received. The funding institution had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve experiments on human subjects or animals requiring ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. No identifiable human data or tissue samples were used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw kinetic data, molecular profiles, and classification parameters are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to these data may be subject to confidentiality agreements or material transfer conditions related to ongoing regulatory submissions. The full dataset is part of an active corporate editorial pipeline and is managed in accordance with contextual integrity and planned licensing frameworks.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the technical team at the Proteomics Core Facility for their support with sample processing and mass spectrometry runs. Special thanks to the Oncovix research unit for providing the infrastructure required for cell culture and phospholipoproteic platforms processing.

Conflicts of Interest

Some of the authors were affiliated with the sponsoring institutions at the time of the study, including the organizational entities responsible for conceptual development and experimental execution. The remaining contributors participated independently or by prior agreement, without financial or commercial ties to the platforms evaluated. No conflicts of interest that could influence the interpretation or integrity of the data have been identified.

References

- Gong, Z.; Cheng, C.; Sun, C.; Cheng, X. Harnessing engineered extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss for enhanced therapeutic efficacy: advancements in cancer immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44(1), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujio, K. Functional genome analysis for immune cells provides clues for stratification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Biomolecules 2023, 13(4), 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, M.; Ouyang, L.; Ding, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W. Non-cytotoxic nanoparticles re-educating macrophages achieving both innate and adaptive immune responses for tumor therapy. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17(4), 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sioud, M. Tumor-associated macrophage subsets: shaping polarization and targeting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(8), 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, V.M.; Zheng, J.; Gaunt, T.R.; Smith, G.D. Phenotypic causal inference using genome-wide association study data: Mendelian randomization and beyond. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, A.; Porcaro, F.; Somogyi, A.; Roudeau, S.; Domart, F.; Medjoubi, K.; Aubert, M.; Isnard, H.; Nonell, A.; Rincel, A.; et al. Cytoplasmic aggregation of uranium in human dopaminergic cells after continuous exposure to soluble uranyl at non-cytotoxic concentrations. Neurotoxicology 2021, 82, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, T.; Liu, R.; Ning, T.; Yang, H.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, D.; Ge, S.; Bai, M.; et al. CAF secreted miR-522 suppresses ferroptosis and promotes acquired chemo-resistance in gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Kwong, A.C.; Zhang, Y.; Hoffmann, H.H.; Bushweller, L.; Wu, X.; Ashbrook, A.W.; et al. IL-6/STAT3 axis dictates the PNPLA3-mediated susceptibility to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Q.; Hazaymeh, R.; Zourob, M. Immunity-on-a-chip: integration of immune components into the scheme of organ-on-a-chip systems. Adv. Biol. (Weinh) 2023, 7(12), e2200312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, J.; Vieira, A.I.S.; Ligeiro, D.; Azevedo, R.I.; Lacerda, J.F. Suppression by allogeneic-specific regulatory T cells is dependent on the degree of HLA compatibility. Immunohorizons 2021, 5(5), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampathkumar, K.; Kerwin, B.A. Roadmap for drug product development and manufacturing of biologics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 113, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayor, M.; Brown, K.J.; Vasan, R.S. The molecular basis of predicting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedia, C.; Dalmau, N.; Nielsen, L.K.; Tauler, R.; Marín de Mas, I. A multi-level systems biology analysis of Aldrin’s metabolic effects on prostate cancer cells. Proteomes 2023, 11(2), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmacher, V. From chemotherapy to biological therapy: a review of novel concepts to reduce the side effects of systemic cancer treatment. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54(2), 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, E.; Carr, A.J.; Plitas, G.; Cornish, A.E.; Konopacki, C.; Prabhakaran, S.; Nainys, J.; Wu, K.; Kiseliovas, V.; Setty, M.; et al. Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell 2018, 174(5), 1293–1308.e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, L.E.; Carnero, A. NAD⁺ metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchareychas, L.; Duong, P.; Covarrubias, S.; Alsop, E.; Phu, T.A.; Chung, A.; Gomes, M.; Wong, D.; Meechoovet, B.; Capili, A.; et al. Macrophage exosomes resolve atherosclerosis by regulating hematopoiesis and inflammation via microRNA cargo. Cell Rep. 2020, 32(2), 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietro, L.; Bottcher-Luiz, F.; Velloso, L.A.; Morari, J.; Nomura, M.; De Angelo Andrade, L.A.L. Expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6), signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT-3) and telomerase in choriocarcinomas. Surg. Exp. Pathol. 2020, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, P.; Ragonese, F.; Stabile, A.; Pistilli, A.; Kuligina, E.; Rende, M.; Bottoni, U.; Calvieri, S.; Crisanti, A.; Spaccapelo, R. Antitumor activity and expression profiles of genes induced by sulforaphane in human melanoma cells. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2547–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Hu, S.; Sun, H.; Tuo, B.; Jia, B.; Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; et al. Extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss remodel tumor environment for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hu, S.; Yan, N.; Popowski, K.D.; Cheng, K. Inhalable extracellular phospholipoproteic platforms delivery of IL-12 mRNA to treat lung cancer and promote systemic immunity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Caetano, J.; Barahona, F.; Pestana, C.; Ferreira, B.V.; Lourenço, D.; Queirós, A.C.; Bilreiro, C.; Shemesh, N.; Beck, H.C.; et al. Multiple myeloma-derived extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss modulate the bone marrow immune microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 909880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenase, P.W. Exosome carrier effects; resistance to digestion in phagolysosomes may assist transfers to targeted cells; II transfers of miRNAs are better analyzed via systems approach as they do not fit conventional reductionist stoichiometric concepts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, S.; Mou, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Dai, X.; Ou, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; et al. Exosome-derived circTRPS1 promotes malignant phenotype and CD8⁺ T cell exhaustion in bladder cancer microenvironments. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhainaut, M.; Rose, S.A.; Akturk, G.; Wroblewska, A.; Nielsen, S.R.; Park, E.S.; Buckup, M.; Roudko, V.; Pia, L.; Sweeney, R.; et al. Spatial CRISPR genomics identifies regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2022, 185, 1223–1239.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutiérrez-Castro, F.; Muñoz-Godoy, N.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Alarcón, L.; Dorado, W.; Lagos, A.; Montenegro, D.; Muñoz, I.; et al. The Design of a Multistage Monitoring Protocol for Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosome (DEX) Immunotherapy: A Conceptual Framework for Molecular Quality Control and Immune Profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.; Ferrari, G.; Grosso, V.; Missale, F.; Bugatti, M.; Cancila, V.; Zini, S.; Segala, A.; La Via, L.; Consoli, F.; et al. Impaired activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 7/9 and STING is mediated by melanoma-derived immunosuppressive cytokines and metabolic drift. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1227648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, M.; et al. Reprogramming exosomes for immunity-remodeled photodynamic therapy against non-small cell lung cancer. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Krakowiak, F.; Iturra, J. Advances in the translational application of immunotherapy with pulsed dendritic cell-derived exosomes. J. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2024, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Chen, Q.; Lin, L.; Sha, C.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, W.; et al. Regulation of exosome production and cargo sorting. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Muñoz-Godoy, N.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Alarcón, L.; Dorado, W.; Lagos, A.; Montenegro, D.; Muñoz, I.; et al. Phospholipid-Rich DC-Vesicles with Preserved Immune Fingerprints: A Stable and Scalable Platform for Precision Immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, K.U.; Alural, B.; Tarakcioglu, E.; San, T.; Genc, S. Lithium inhibits oxidative stress-induced neuronal senescence through miR-34a. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4171–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, H.V.; Sakamoto, L.H.T.; Bacal, N.S.; Epelman, S.; Real, J.M. MicroRNAs and exosomes: promising new biomarkers in acute myeloid leukemias? Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2022, 20, eRB5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; An, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Fang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. The activator protein-1 complex governs a vascular degenerative transcriptional programme in smooth muscle cells to trigger aortic dissection and rupture. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutiérrez-Castro, F.; Muñoz-Godoy, N.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Iturra, J.; Krakowiak, F.; Alarcón, L.; Dorado, W.; Lagos, A.; et al. Beyond Exosomes: An Ultrapurified Phospholipoproteic Complex (PLPC) as a Scalable Immunomodulatory Platform for Reprogramming Immune Suppression in Metastatic Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming-de-Moraes, C.D.; Rocha, M.R.; Tessmann, J.W.; de Araujo, W.M.; Morgado-Diaz, J.A. Crosstalk between PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β-catenin pathways promote colorectal cancer progression regardless of mutational status. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2022, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.L.; Wu, Y.; Konaté, M.; Lu, J.; Mallick, D.; Antony, S.; Meitzler, J.L.; Jiang, G.; Dahan, I.; Juhasz, A.; et al. Exogenous DNA enhances DUOX2 expression and function in human pancreatic cancer cells by activating the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 205, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Li, N.; Liu, B.; Ma, Z.; Ling, J.; Yang, W.; Li, T. Narasin inhibits tumor metastasis and growth of ERα-positive breast cancer cells by inactivation of the TGF-β/SMAD3 and IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathways. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 5113–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, M.; Cheng, A.; Zhao, Q.; He, C.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. The role of SOCS proteins in the development of virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, G.; Singh, A.K.; Gupta, S. EZH2: Not EZHY (Easy) to Deal. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12(5), 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassioli, C.; Baldari, C.T. Lymphocyte polarization during immune synapse assembly: centrosomal actin joins the game. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 830835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Muñoz, I.; Alarcón, L.; Montenegro, D.; Krakowiak, F.; Dorado, W. Ultra-purified phospholipoprotein complex (PLPC) as a structural trigger for reprogramming the tumor microenvironment: Clinical modeling of dendritic exosome-based therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 16 Suppl., e14511. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, F.; Miyoshi, M.; Kimoto, A.; Kawano, A.; Miyashita, K.; Kamoshida, S.; Shimizu, K.; Hori, Y. Pancreatic cancer cell-derived exosomes induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cancer cells themselves partially via transforming growth factor β1. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2022, 55(3), 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lan, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Dai, J.; Xu, L.; Cai, Y.; Hou, G.; Xie, K.; Liao, M.; et al. IL-6-induced cGGNBP2 encodes a protein to promote cell growth and metastasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2022, 75(6), 1402–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, H.; Qi, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, B.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, R.; Xue, H.; Li, G. Tumor-derived exosomes deliver the tumor suppressor miR-3591-3p to induce M2 macrophage polarization and promote glioma progression. Oncogene 2022, 41(41), 4618–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Muñoz, I.; Krakowiak, F.; Montenegro, D.; Dorado, W.; Alarcón, L. Exosome-based metabolic reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment: Targeting lactate transport and pH control via MCT4 modulation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 16 Suppl., e14512. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos, I.; Shadiack, E.; Ganetzky, R.D.; Falk, M.J. Mitochondrial medicine therapies: rationale, evidence, and dosing guidelines. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32(6), 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.Y.; Li, H.M.; Wang, X.Y.; Xia, R.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.S. TIGAR drives colorectal cancer ferroptosis resistance through ROS/AMPK/SCD1 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 182, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soula, M.; Unlu, G.; Welch, R.; Chudnovskiy, A.; Uygur, B.; Shah, V.; Alwaseem, H.; Bunk, P.; Subramanyam, V.; Yeh, H.W.; et al. Glycosphingolipid synthesis mediates immune evasion in KRAS-driven cancer. Nature 2024, 633(8029), 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Leng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Y.; Mei, C.; Zhang, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; et al. IRF3 activates RB to authorize cGAS–STING-induced senescence and mitigate liver fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10(9), eadj2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Sobarzo, A.; Muñoz, N.; Krakowiak, F.; Iturra, J.; Montenegro, D.; Dorado, W.; Peña-Vargas, C. PLP-driven exosomal breakthroughs: Advancing immune solutions for complex tumor microenvironments. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 16 Suppl., e14522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Garibay, A.C.; Ruiz-Barcenas, B.; Rescala-Ponce de León, J.I.; Ochoa-Zarzosa, A.; López-Meza, J.E. The GPR30 receptor is involved in IL-6-induced metastatic properties of MCF-7 luminal breast cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(16), 8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepsch, O.; Namer, L.S.; Köhler, N.; Kaempfer, R.; Dittrich, A.; Schaper, F. Intragenic regulation of SOCS3 isoforms. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L. Advance in bone destruction participated by JAK/STAT in rheumatoid arthritis and therapeutic effect of JAK/STAT inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval, R.; Rivadeneira, I.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Sobarzo, A.; Muñoz, I.; Lagos, A.; Muñoz, N.; Krakowiak, F.; Aguilera, R.; Toledo, A. Decoding NAMPT and TIGAR: A molecular blueprint for reprogramming tumor metabolism and immunity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 16 Suppl., e14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binju, M.; Amaya-Padilla, M.A.; Wan, G.; Gunosewoyo, H.; Suryo Rahmanto, Y.; Yu, Y. Therapeutic inducers of apoptosis in ovarian cancer. Cancers 2019, 11(11), 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, M.B.; Hom-Tedla, M.S.; Yi, J.; Li, S.; Rivera, S.A.; Yu, J.; Burns, M.J.; McRae, H.M.; Stevenson, B.T.; Coakley, K.E.; et al. ARID1A suppresses R-loop-mediated STING-type I interferon pathway activation of anti-tumor immunity. Cell 2024, 187(13), 3390–3408.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharom, F.; Ramirez-Valdez, R.A.; Khalilnezhad, A.; Khalilnezhad, S.; Dillon, M.; Hermans, D.; Fussell, S.; Tobin, K.K.S.; Dutertre, C.A.; Lynn, G.M.; et al. Systemic vaccination induces CD8+ T cells and remodels the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2022, 185(23), 4317–4332.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzounakas, V.L.; Anastasiadi, A.T.; Karadimas, D.G.; Velentzas, A.D.; Anastasopoulou, V.I.; Papageorgiou, E.G.; Stamoulis, K.; Papassideri, I.S.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Antonelou, M.H. Early and late-phase 24 h responses of stored red blood cells to recipient-mimicking conditions. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 907497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaletto, J.; Bernier, A.; McDougall, R.; Cline, M.S. Federated Analysis for Privacy-Preserving Data Sharing: A Technical and Legal Primer. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2023, 24, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.E.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Krakowiak, F.; Iturra, J.; Dorado, W.; Aguilera, R. 60P Innovative Applications of Neoantigens in Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosome (DEX) Therapy and Their Impact on Personalized Cancer Treatment. Immuno-Oncol. Technol. 2024, 24, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Wollenberg, A.; Reich, A.; Thaçi, D.; Legat, F.J.; Papp, K.A.; Stein Gold, L.; Bouaziz, J.D.; Pink, A.E.; Carrascosa, J.M.; et al. Nemolizumab with concomitant topical therapy in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2): results from two replicate, double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2024, 404(10451), 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieva, M.; Barrera Román, M.; de Blank, S.; Petcu, D.; Zeeman, A.L.; Dautzenberg, N.M.M.; Cornel, A.M.; van de Ven, C.; Pieters, R.; den Boer, M.L.; et al. BEHAV3D: a 3D live imaging platform for comprehensive analysis of engineered T cell behavior and tumor response. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19(7), 2052–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.E.; Gutierrez-Castro, F.; Rivadeneira, I.; Krakowiak, F.; Iturra, J.; Dorado, W.; Aguilera, R. 61P Optimized protocol for the accelerated production of dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEXs): Immuno-Oncology and Technology. 2024, 24, 100872. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Li, T.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Han, B. Integrating single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing data unveils antigen presentation and process-related CAFs and establishes a predictive signature in prostate cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.N.; Röllig, C.; Metzeler, K.; Heisig, P.; Stasik, S.; Georgi, J.A.; Kroschinsky, F.; Stölzel, F.; Platzbecker, U.; Spiekermann, K.; et al. Unsupervised meta-clustering identifies risk clusters in acute myeloid leukemia based on clinical and genetic profiles. Commun. Med. (Lond) 2023, 3(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimova, A.F.; Khalitova, A.R.; Suezov, R.; Markov, N.; Mukhamedshina, Y.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Huber, M.; Simon, H.U.; Brichkina, A. Immunometabolism of tumor-associated macrophages: a therapeutic perspective. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 220, 115332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Bai, W.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J. Neutrophil-macrophage communication via extracellular phospholipoproteic platforms transfer promotes itaconate accumulation and ameliorates cytokine storm syndrome. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21(7), 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thone, M.N.; Chung, J.Y.; Ingato, D.; Lugin, M.L.; Kwon, Y.J. Cell-free, dendritic cell-mimicking extracellular blebs for molecularly controlled vaccination. Adv. Ther. 2023, 6(1), 2200125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.Z.; Seok, J.; Kim, G.J.; Choi, B.C.; Baek, K.H. Deficiency of HtrA4 in BeWo cells downregulates angiogenesis through IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhong, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Qin, Z.; Shi, A.; Xu, W.; Zheng, C.; et al. ICAM-1-mediated adhesion is a prerequisite for exosome induced T cell suppression. Dev. Cell 2022, 57(3), 329–343.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xun, Z.; Ma, K.; Liang, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; Guo, X.; et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78(4), 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss in immune response and immunity. Immunity 2024, 57(8), 1752–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Yoshida, K.; Koga, H.; Kitagawa, M.; Nagao, Y.; Iida, M.; Kawaguchi, S.; Zhang, M.; Nakayama, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Spatial exosome analysis using cellulose nanofiber sheets reveals the location heterogeneity of extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regimbeau, M.; Abrey, J.; Vautrot, V.; Causse, S.; Gobbo, J.; Garrido, C. Heat shock proteins and exosomes in cancer theranostics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86 Pt 1, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feudis, M.; Walker, G.E.; Genoni, G.; Manfredi, M.; Agosti, E.; Giordano, M.; Caputo, M.; Di Trapani, L.; Marengo, E.; Aimaretti, G.; et al. Identification of haptoglobin as a readout of rhGH therapy in GH deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5263–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, J.N.; Nukala, U.; Rodriguez Messan, M.; Yogurtcu, O.N.; McCormick, Q.; Sauna, Z.E.; Whitaker, B.I.; Forshee, R.A.; Yang, H. A retrospective review of Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Advisory Committee meetings in the context of the FDA’s benefit-risk framework. AAPS J. 2023, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, D.; Núñez, N.G.; Pinyol, R.; Govaere, O.; Pinter, M.; Szydlowska, M.; Gupta, R.; Qiu, M.; Deczkowska, A.; Weiner, A.; et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature 2021, 592, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Abadchi, S.N.; Shababi, N.; Ravari, M.R.; Pirolli, N.H.; Bergeron, C.; Obiorah, A.; Mokhtari-Esbuie, F.; Gheshlaghi, S.; Abraham, J.M.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss promote wound repair in a diabetic mouse model via an anti-inflammatory immunomodulatory mechanism. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12(26), e2300879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kink, J.A.; Bellio, M.A.; Forsberg, M.H.; Lobo, A.; Thickens, A.S.; Lewis, B.M.; Ong, I.M.; Khan, A.; Capitini, C.M.; Hematti, P. Large-scale bioreactor production of extracellular phospholipoproteic platformss from mesenchymal stromal cells for treatment of acute radiation syndrome. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15(1), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).