1. Introduction

A great deal of valuable information can be obtained from the breeding biology of birds, e.g. on population dynamics (Holmes et al. 1996), the life strategy of the species (Grant et al. 2005), reproduction rate (Rotella et al. 2004), nest biology (Dinsmore et al. 2002), predation pressure or habitat quality (Robinson et al. 1995). However, the breeding success is not easy to estimate and requires knowledge of the complete nest history, from the nest construction to laying of the first egg to nest abandonment (Schneider and McWilliams 2007), or at least data from key stages of breeding (Croston et al. 2018). To improve our understanding of the factors that determine avian reproductive success, it is important to obtain data on bird behaviour during breeding, the timing of breeding, and data on nest attendance during incubation, or the duration of incubation breaks (Croston et al. 2018).

The oldest method to obtain these data is direct observation of breeding progress during frequent visits (Normant 1995), but this method is time consuming and can cause excessive disturbance. However, constant advances in technology allow continuous collection of data from the breeding process using a variety of sophisticated methods and technologies. For example, cameras are a highly effective tool for monitoring nest attendance (Bulla et al. 2016, Croston et al. 2018, Khamcha et al. 2018, Guillette and Healy 2019). However, this method of data collection requires external power, cameras can be conspicuous to predators, and processing nest visitation data from recorded video is time consuming (Weidinger 2006, Dallmann et al. 2016). There are a number of methods that focus on monitoring of incubation progress, such as the Remote Incubation Monitoring System (RIMS). This method is based on pressure switches located in the nests, the data is transmitted wirelessly to receivers located further away from the nest, and then the data is sent by cable to the control panel (Bottitta et al. 2002). Incubation behaviour can also be studied using a transponder system that records the identity of the parents on their nest. The system consists of a small chip attached to the tail of the parent, an antenna buried under the nest and a recording device buried nearby (Kosztolanyi and Szekely 2002). Another method based on recording the presence of tagged parents at the nest is a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) reader. This technology consists of a reader in the nest and a passive integrated tag attached to the parents. Light recorders attached to the parents are used to record the start and the end of the incubation period. A sudden change in light intensity followed by a period of low or high light intensity indicates the beginning or the end of the incubation period. Another method of obtaining incubation data is through automatic receivers that record the signal strength of a radio tag attached to the bird (signal strength is constant during incubation; Bulla et al. 2016). Telemetric eggs are used to monitor microclimate during incubation (Stetten et al. 1990, Manlove and Hepp 2000, Loos and Rohwer 2004, Clauser and McRae 2017). These methods are also costly (Bottitta et al. 2002, Hoover et al. 2004).

In recent years, small temperature loggers have been used to monitor breeding progress, allowing nest occupancy to be determined by evaluating recorded changes in nest temperature over time (e.g. Hartman and Oring 2006, Schneider and McWilliams 2007, Sutti and Strong 2014, Croston et al. 2018, Hoppe et al. 2018, Croston et al. 2020). Temperature loggers are most commonly used to detect the start of incubation (Ruiz-De-Castañeda et al. 2012), to record nest attendance (Cooper and Phillips 2002, Schneider and McWilliams 2007, Bueno-Enciso et al. 2017, Croston et al. 2020, Sullivan et al. 2020), but also to obtain data on nest fate (Hartman and Oring 2006). These temperature loggers can provide high-resolution nest temperature data without the need to place bulky equipment inside the nests (Croston et al. 2018). This method of monitoring of breeding progress has been used in different types of open bird nests. Schneider and McWilliams (2007) tested this method with plovers (Charadrius melodus) that nest in scrapes, small depressions in the sand created during sand excavation. Hoppe et al. (2018) used temperature loggers to determine nest attendance in female greater prairie chickens (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus). Croston et al. (2020) also used temperature loggers to determine nest attendance in mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) and gadwalls (Mareca strepera). Temperature loggers were used in a range of bird species with different types of nest openings or nest boxes (Ruiz-De-Castañeda et al. 2012, Bueno-Enciso et al. 2017), but not in a natural closed nest, e.g. nest burrows, and rarely in tree holes. Only Lill and Fell (2007) used temperature loggers to study the microclimate in the nest hole of Rainbow Bee-eaters (Merops ornatus), but not to monitor breeding progress.

The aim of this study was to test the method of monitoring of the breeding progress using temperature sensors in a closed nest, specifically in a naturally occupied nest holes of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), and to find out whether it is possible to derive information from the temperature data about the individual transitions between the breeding phases: a) egg-laying, b) the start of incubation, c) the hatching of the nestlings and d) the fledging of the chicks from the nest hole. The study represents the first ever attempt to describe the whole breeding event of a burrow nesting bird species based on continuous temperature data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species

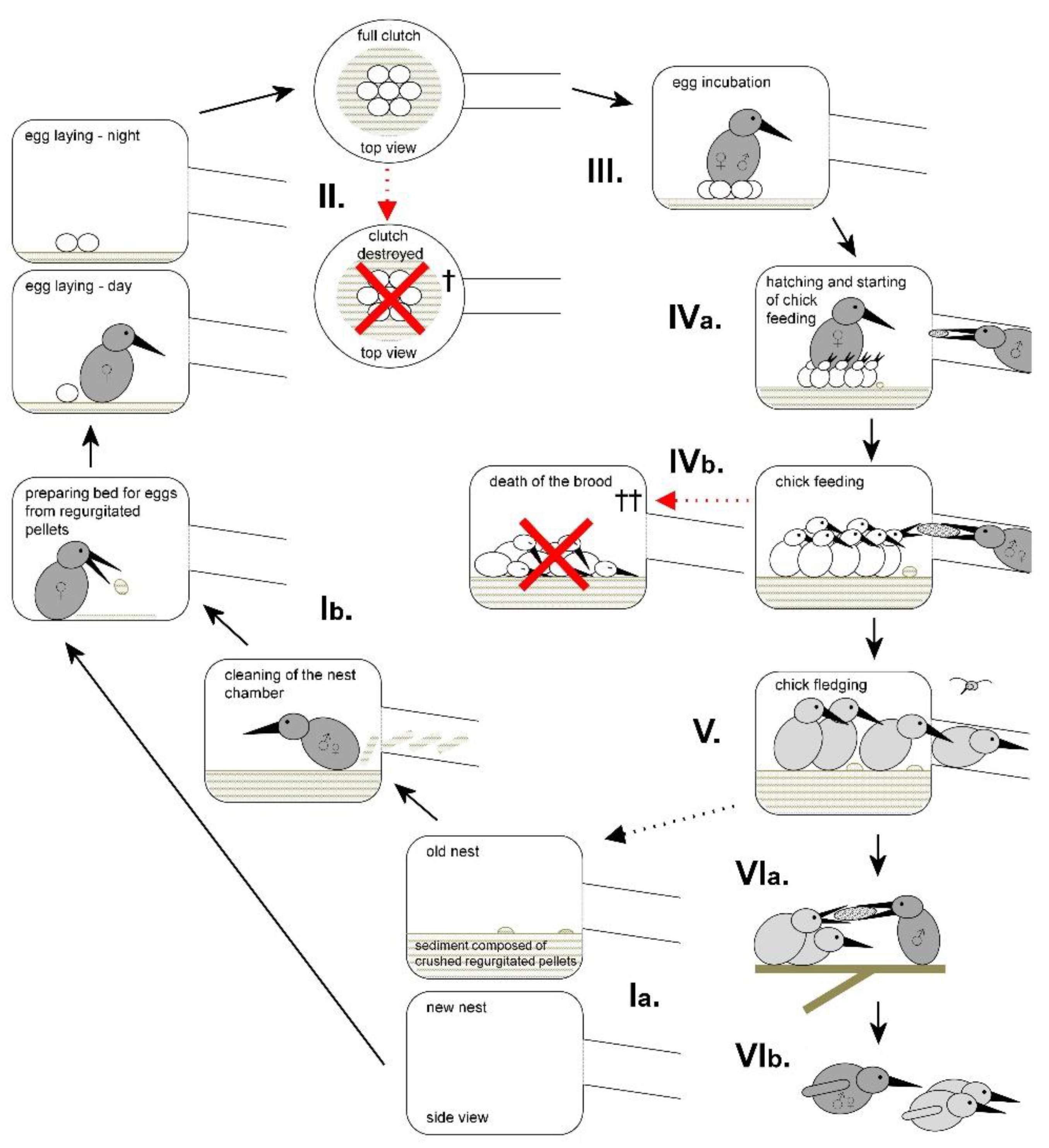

The common kingfisher (

Alcedo atthis) digs a nest hole that is 40-70 cm long on the steep banks of watercourses and reservoirs, as well as in the meanders of streams. Nest holes lack substantial insulation structures and are primarily influenced by the relatively stable temperature of the soil. The nest consists of a corridor and a nest chamber where the female lays 4-7 eggs on a thin layer of crushed regurgitate pellets (undigested prey remains, mostly fish bones, since fish absolutely dominated the diet at most localities; cf. Čech and Čech 2011, 2015). Incubation begins after the last egg is laid and lasts 18-21 days. Both parental birds participate in incubation. It is common for nestlings to hatch at different times, but the difference is usually no more than two days. Parents continue to warm the chicks for up to 5-7 days after hatching. Chicks leave the nest hole at 23-25 days of age (

Figure 1; Čech 2007, Hadravová 2019, Čech and Čech 2022).

2.2. Study Area and Selection of the Nest Hole for Temperature Measurement

The study was carried out on the Radotínský, Botič and Rokytka streams in the Czech Republic. The Radotínský stream is a naturally meandering lowland stream that belongs to the Berounka River basin and flows through central Bohemia and the capital city of Prague. The Botič stream and Rokytka stream are a part of the lower Vltava River basin and flows through central Bohemia and the capital city of Prague.

On the 3 streams mentioned above, 5 nest holes and 6 broods were monitored during 3 nesting seasons (

Figure 2) - 2 nest hole on the Radotínský stream - 49°59'51.699"N, 14°19'35.110"E (1 measurement in 2018) and 49°59'48.332"N, 14°18'18.762"E (2 consecutive breeding attempts in full length in 2020), 2 nest hole in the same nest wall on the Botič stream - 50°3'3.689"N, 14°31'15.127"E (1 measurement in 2018) and 50°3'3.693"N, 14°31'15.085"E (1 measurement in 2019) and 1 nest hole on the Rokytka stream - 50°6'27.503"N, 14°31'18.140"E (1 measurement in 2019). All these nest holes are among the nest holes monitored annually in Prague district (for details see

Table 1).

It was important that the nest hole had certain parameters for the installation of the temperature sensors. The nest had to be high enough above the water level to prevent it from being washed away during rainy periods, it had to be not too long (optimum up to 65 cm) and it had to be straight (location of the nest chamber in a straight direction). The presence of vegetation around the nest hole was necessary to hide the temperature data logger. With regard to the implementation of the research in the urban environment of the capital city of Prague, another important parameter was the location of the nest hole in a less disturbed area (further away from busy roads, not in places where dogs go to bathe, etc.), so that breeding would not be disturbed and the temperature data loggers would not be at risk of theft or destruction. All these parameters fit to less than 1/13 of the nests monitored in Prague district (A. Hadravová, unpubl. data).

2.3. Temperature Measurement

A temperature data logger with two external probes (Comet logger S0121, declared accuracy ±0.2°C from -50 to +100°C, resolution 0.1°C) was used. The external probes are connected by a 2 m long shielded PVC cable (P1000TR160/E, measuring range -30 to +80°C, tolerance ±(0.3 +0.005* |t|)°C). The measurement interval was chosen according to the memory capacity to ensure that all temperature changes during the breeding period were recorded with acceptable effort. The temperature in the nest chambre does not change quickly and the measurement interval was 1 minute, which meant that data was downloaded approximately every 10 days. At each data download, the position of the sensor was checked and the breeding period was detected using a special mini-camera (control duration max. 2 minutes). During the inspection of the nest hole, the nesting process was virtually undisturbed. During the incubation and chick warming, if a parent was present, the parent either continued to sit on the eggs/chicks during the inspection or retreated briefly to the rear of the nest chamber, with the parent not leaving the nest hole after the inspection. During chick feeding, an inspection took place after the chicks had been fed and the parent had left the nest hole.

The temperature datalogger was hidden in a cut plastic bottle (protection from rain) attached to vegetation (most often the roots of trees or bushes), all thoroughly covered by the surrounding vegetation (

Figure 3). An external probe was placed inside an occupied nest chamber (during egg laying). The probe was placed in the chamber outside the egg so that it lay freely on the nest sediment and did not touch the wall of the chamber (

Figure 3d). The cable of the temperature probe was fed through the centre of the corridor of the nest hole - a groove was made in which the cable was placed, then everything was buried with the surrounding material. A special mini-camera was a necessary tool for the installation. This installation took no more than 15 minutes. The second sensor was placed in a man-made hole at the same depth and height as the occupied nest hole. The hole was situated close to the occupied nest hole where the measurement was taking place (distance 50 cm in the same nest wall). The remainder of the cable between the temperature datalogger and the nest hole and between the temperature datalogger and the artificial opening was also run through a groove, secured with metal clips and covered with nest wall material.

Ambient temperature was measured using a CEM DT-171 data logger (temperature accuracy ±1% from -10 to +40°). The nest hole where the measurements were taken was located in the area of the capital city of Prague, so the effect of altitude on the ambient temperature was not assumed, and therefore the air temperature near each nest hole was not measured. Another reason was the problem with the location of this data logger near the nest hole - in the shade, at a height of 2 m above the ground, further away from the water. According to the meteorological convention, the data logger was placed in the shade at a height of 2 m above the ground in Prague (50°0'47.845"N, 14°28'28.565"E). Placing another temperature data logger near the nest hole could also attract human attention, potentially disrupting breeding and possibly leading to data logger theft. The temperature measurement interval was 1 minute, and the data were downloaded every 7 to 11 days. Permission to install temperature sensors at the kingfisher's natural nesting site was obtained from Prague City Hall (the local nature conservation authority).

2.4. Data Processing

Temperature data from the nest chamber and parallel "soil" hole were downloaded using the manufacturer's COMET VISION version 2.1 programme. Ambient air temperature data were downloaded using a program from the manufacturer Wheather Datalogger.Ink. The data were processed using Rx64 3.1.2 statistical software (R Core Team 2017) and Excel 2019. The data were analysed using a two-sample Wilcoxon test to compare the temperature difference during incubation and chick feeding and a paired Wilcoxon test was used to compare the temperature during egg laying between day and night.

Based on the knowledge of the length of the individual rearing phases (laying, incubation, feeding; Čech 2007, Hadravová 2019), the individual transitions of these phases were first approximately located on the temperature curve and then these parts of the temperature curve were analysed. The decile method was used to visualise the breeding phases. It was assumed that there would be noticeable differences between days and nights, so the data series were split into days and nights, each theoretically having around 720 data points. The 1st and 9th deciles of the half-day data was used to reduce the short extremes ("peaks"), which simply but effectively reduced these short extremes. The decile distance can be used to describe what is happening in the nest hole. If the deciles D1 and D9 are very close to each other, there is little variation in temperature; if the deciles are further apart, there is more variation in temperature. To correct the data for soil temperatures, which fluctuate slowly with cyclonic periods and increase continuously as summer progresses, the data were rectified as the difference between the measured temperature in the occupied nest chamber and the control soil temperature in a man-made parallel hole. Deciles were calculated from this temperature difference. The information obtained from the individual checks of the nest hole (

Appendix A) was used to verify the correctness of the localised transitions of the breeding phases on the temperature curve.

To determine the length of each day and night, the actual astronomic values of dawn and dusk were used (Meteogram.cz) - day (the end of dawn to the beginning of dusk), night (beginning of dusk to the end of dawn). Astronomic twilight is defined by a very dark sky when the stars are clearly visible. Astronomical dawn is when the sun is less than 18° below the horizon. The above times were chosen to ensure that the birds were not active during this period.

3. Results

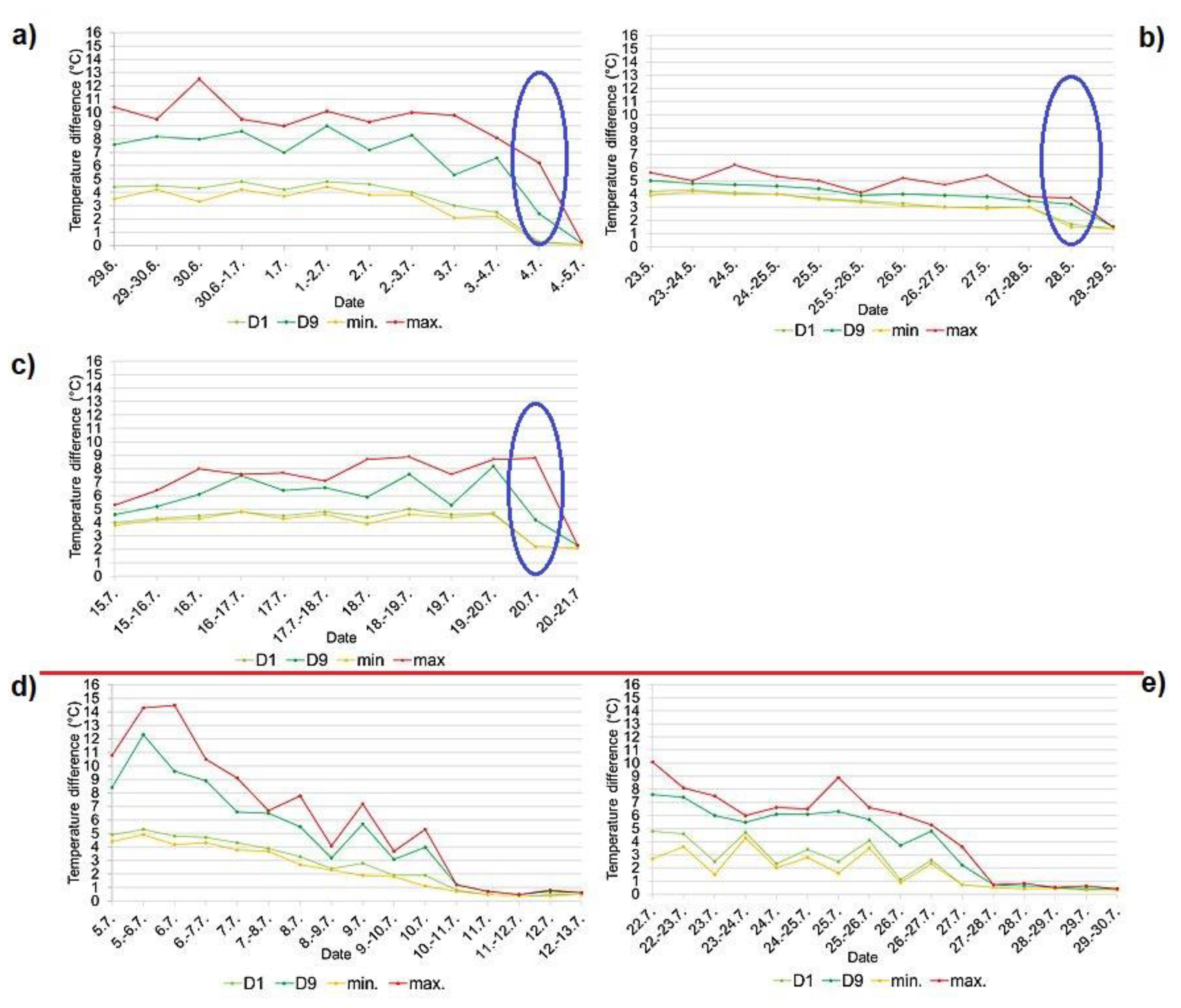

The raw data show relatively high short-term stability, but also contain short extremes (

Figure 4a, b, c, d,

Figure 5a, b), probably due to random events such as the piston effect when the parents enter the nest or random movements around the clutch. The temperature curves (

Figure 4a, b, c, d) demonstrate a gradual increase in temperature during the breeding period. During incubation, only one parent provides heat, but in the second half of a breeding event, especially in its final part, thermal heat is produced not only by incubating or rearing parent, but also by increasing amount of body mass of growing chicks.

The temperature measurements in 2018 were carried out continuously from 1 June (7 eggs in the nest chamber) to 5 July (a total of 35 days or 48,915 minutes of recording) in the occupied kingfisher nest chamber on the Radotínský stream (see

Figure 4a) and from 18 June (7 eggs in the nest chamber) to 18 July (a total of 31 days or 43,287 minutes of recording) on the Botič stream (

Figure 5a). Measurements of temperature in 2019 were taken from 24 May (2 eggs in the nest chamber) to 11 July (a total of 49 days or 69 002 minutes;

Figure 4b) on the Rokytka stream and from 3 July (7 eggs in the nest chamber) to 30 July on the Botič stream (a total of 28 days or 38 372 minutes;

Figure 5b). The temperature measurements at the Radotínský stream were taken continuously from 16 April to 21 July 2020 (

Figure 4c, d,

Appendix B) - the first breeding event from 16 April (6 eggs in the nest chamber) to 28 May (a total of 28 days or 38 372 minutes;

Figure 4c) and the second breeding event from 30 May (laying of the first egg) to 20 July (

Figure 4d).

In two cases it was possible to record the temperature course already during the laying phase, namely in 2019 at the Rokytka stream (see

Figure 6a) and in 2020 at the Radotínský stream during the second breeding event (

Figure 6b). The results clearly showed, that there was an expected temperature difference between the egg-laying phase and the incubation phase.

Figure 6a,b demonstrate that the distance between deciles D1 and D9 is greater during the day but almost overlap at night (egg-laying phase). This suggests that the female is only present in the nest chamber during the day, thus the egg laying takes place during the day (the temperature in the nest chamber is higher during the day than at night - V = 2037566, p-value < 2.2e-16). After the last egg has been laid, the parent is present in the nest chamber both day and night, as can be seen from the distance between deciles D1 and D9, the deciles do not overlap at any time, but the distance between the deciles is smaller and more constant (

Figure 6a, b).

Hatching of chicks was detected from the temperature curves in 3 out of 6 measurements, namely on the Radotínský stream in 2018 (

Figure 7a), on the Botič stream in 2018 (

Figure 7e) and on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (

Figure 7b). The hatching of nestlings was always indicated by a “jump” in the temperature curve (

Figure 4a, b,

Figure 5a). This jump was also evident from a distance of deciles (

Figure 7a, b, e). At hatching, deciles D1 and D9 moved apart due to the warmth of the hatchlings, but then moved closer together during both day and night due to the insulation provided by the parent. The temperature jump mentioned above was not very noticeable for the other measurements conducted on the Botič stream in 2019 and on the Radotínský stream in 2020.

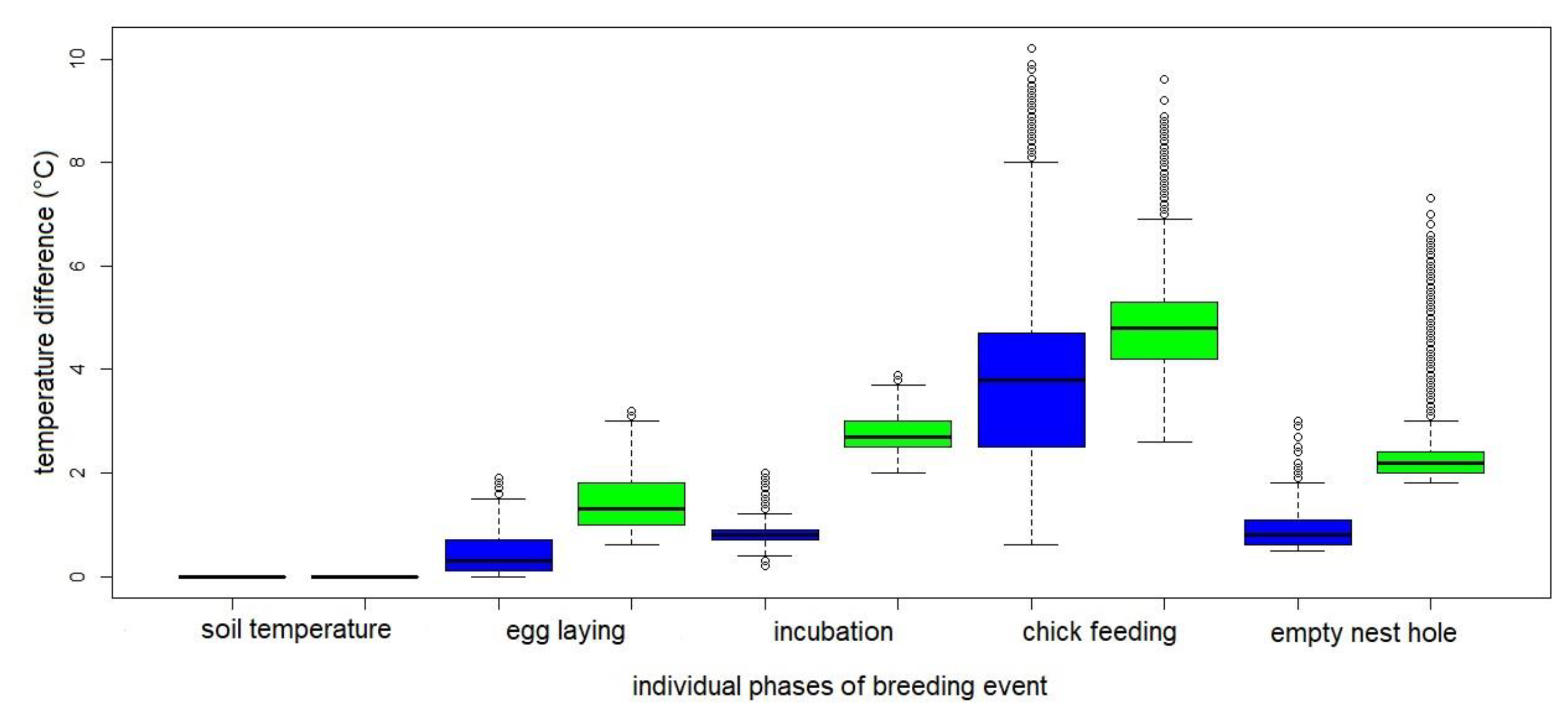

There was noticeable difference in temperature when the parent and chicks were present (first 5-7 days after hatching) and when the chicks were alone in the nest chamber. A statistically significant difference was found when comparing the temperature during the first five days (mean 2.8 °C above the surroundings) and 6-10 days after hatching (mean 4.2 °C above the surroundings; Wn= 28798, 28791 = 647333467, p-value < 2.2e-16) and when comparing the temperature during the first five days (mean 2.8 °C) and the last five days before fledging (mean 4.4 °C; Wn= 28815, 28791 = 669472972, p-value < 2.2e-16). The temperature during incubation (mean 2.8°C) was lower than during the feeding (mean 4.4°C; Wn= 129252, 153112 = 4501860161, p-value < 2.2e-16 calculated from the difference between the temperature in the occupied nest chamber and the control temperature of the soil).

For all successful breeding events (on the Radotínský stream in 2018, on the Rokytka stream in 2019 and on the Radotínský stream in 2020 - both events), during the fledging time a rapid decrease in temperature was evident in the graphs (

Figure 4a, b, c d). At night, the empty nest chamber is indicated by the overlap of deciles D1 and D9 (

Figure 8a, b, c).

The unsuccessful breeding event (on the Botič stream in 2018 and 2019), when the chicks gradually died in the nest hole, was always manifested in the same way on the temperature curve, by a gradual decline in temperature (the bodies of the chicks gradually cooled.;

Figure 5a, b). The gradual death of the chicks is evident on the decile graph, deciles D1 and D9 gradually approaching each other (

Figure 8d, e).

4. Discussion

This study tested a method of monitoring of the breeding progress of soil cavity nesting common kingfishers by using temperature sensors placed in occupied nest holes. The data recorded by temperature data loggers provided information on the presence or absence of a parent in the nest, the start of incubation, or when the brood failure occurred, similar to other nest types (Hartman and Oring 2006, Schneider and McWilliams 2007, Sutti and Strong 2014). Temperature data from the kingfisher's nest chamber provided also information on the last egg laid and the start of incubation (it is not possible to determine the exact time, only the day). The incubation period began when the parent, female or male, was present in the nest chamber both during the day and at night (in contrast, during the egg-laying period the female was only present during the day).

Temperature data loggers are frequently used in open bird nests to monitor nest attendance, as in the study by Schneider and McWilliams (2007) or Hoppe et al. (2018). The length of the breaks when the parents were not present in the nest chamber during incubation could not be determined from the temperature curve, probably because of the rapid exchange of parents due to the low temperature in the nest hole. The incubating bird leave the nest only at the time the second bird, in close proximity to the nest wall, uses the signal call that it is ready to assume the parental care (M. Čech, pers. observation). On the other hand, the presence or absence of the parents in the nest chamber during the egg-laying period could be easily determined (presence of the female during the day, abandoned nest at night).

The temperature curve allowed for the determination of when the chicks left the nest chamber. This was indicated by a rapid temperature drop and deciles overlapping the following night after the chick fledging. Hartman and Oring (2006) obtained information on when the nest failed from the temperature data of the nest of the Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), as did Sutti and Strong (2014) from the temperature data of different bird species. Temperatures inside the kingfisher's nest chamber also indicated that the nest failed. Both breeding failures occurred during the feeding phase, and in both cases the chicks died gradually in the nest chamber, as evidenced by the gradual decrease in temperature in the nest chamber and the gradual approach of the deciles. However, determining the exact date of death for the chicks is not possible due to the possibility that their misery may have slowed their development. Therefore, the age of the dead chicks found may not fully correspond to the reality. It is important to note that the dead chicks were to some extent conserved in the nest chamber (A. Hadravová, pers. observation).

It was assumed that it would not be possible to estimate the hatching date from the temperature data collected from the kingfisher nest chamber. Reason for this assumption was that during the hatching and for the next 5-7 days after hatching, the parent is still warming the chicks, so the temperature in the nest chamber should not be affected by the small warm bodies of the chicks, as the chicks, like the eggs, are well insulated by the incubating parent. Also, indeed, for some reason, the hatching stage of chicks is not included in studies where temperature loggers have been used to collect data from individual phases of breeding event (Hartman and Oring 2006, Schneider and McWilliams 2007, Ruiz-De-Castañeda et al. 2012, Bueno-Enciso et al. 2017, Croston et al. 2020, Sullivan et al. 2020). Sutti and Strong (2014) even state that hatch date cannot be determined from temperature data and that nest inspections around the predicted hatch time are required to accurately estimate this date. It was surprising to find that for 3 measurements (on the Radotínský and Botič streams in 2018 and on the Rokytka stream in 2019) it was possible to estimate when the chicks hatched from the temperature curves. A temperature increase was observed in the temperature curves, which corresponded to the hatching of the chicks, in the decile plot, the deciles were further apart during this period, and closer together after hatching (the influence of a well-insulated parent warming the newly hatched chicks). A possible explanation for the fact that only in some cases it was possible to estimate the date of hatching from the temperature curves could be the different behaviour of the parent birds at higher ambient temperatures, in which case the newly hatched chicks could remain alone in the nest chamber for longer, which would probably be reflected in a higher temperature - the unfeathered warm bodies of the chicks would heat the nest chamber. However, this phenomenon was observed during inspections of long-term monitored kingfisher nests when the chicks were older (from about 4 to 7 days old), not during the hatching phase when the parental bird was almost always present (A. Hadravová, pers. observation). On the other hand, on the Botič stream in 2019 or from the continuous measurement of the 1st and 2nd breeding period on the Radotínský stream in 2020, it was not possible to determine when the chicks hatched from the course of temperatures in the nest chamber. In order to understand why it is not always possible to estimate the hatching date from the temperature curves, and to be able to estimate the hatching date, it would be appropriate to take further measurements and also to place a camera trap near the nests (to catch the beginning of a consecutive chick feeding phase).

Although the temperature curves do not clearly show a gradual increase in temperature in the nest chamber, statistical results have demonstrated that a gradual increase in temperature does occur, probably due to the rapid growth of the young (increase in biomass in the chamber) and the slow growth of feathers. The metabolic heat of chicks, combined with minimal insulation caused by relatively slow development of a feather cover (absence of down feathers, feathers are extremely long period unfolded in shafts) is substantial, therefore the uninsulated chicks heat up the nest chamber considerably. A typical kingfisher chick weighs ~37 g on the 12th day (Čech and Čech 2017), a complete brood at this age overcome the weight of a parent almost 6.5 times (~260 g as a cumulative weight of 7 chicks; ~40 g as a weight of one average parental bird). At this age, the chicks still have their feathers unfolded in shafts, but the chicks already seem (somehow) to be isolated. Also, around the 18th day of the feeding phase, when the chicks are the heaviest (an average chick weight ~52 g; Čech and Čech 2017), they are almost fully feathered and cumulatively almost 9 times the weight of the parent, this apparently has an effect on the temperature in the nest chamber.

The use of temperature data loggers to obtain information on the progress of the breeding event or the whole breeding season is a gentler method than direct inspection of nests and is a safe method that does not adversely affect breeding progress (Stephenson et al. 2021). On the other hand, some studies (e.g. Cooper and Phillips 2002, Weidinger 2006, Sutti and Strong 2014, Croston et al. 2018) admit that the interpretation of information from temperature curves alone is to some extent burdened with a certain degree of uncertainty, and therefore they state that for a correct interpretation it would be advisable to have available a camera recording or information obtained by direct inspection of the nest where temperature measurements took place. Installing a camera in a kingfisher's natural nest would be problematic, too invasive, technically demanding and likely to disrupt the natural breeding behaviour (also barely allowed since highly protected, umbrella species of freshwater ecosystems according to both Czech and EU directives). Even the installation of a camera trap would not be possible as all the nest holes where temperature measurements were taken were in an urban environment and placing another device near the burrow could attract human attention, which could disrupt breeding progress and possibly lead to a theft or destruction of the camera trap. While measuring the temperature in the kingfisher's nest chamber, the position of the sensor was regularly checked to avoid burying it in the nest sediment, which could significantly affect the measured temperature. These checks also provided information about the phase of the breeding event and helped to better interpret the results.

The temperature in the occupied nest chamber of the common kingfisher was measured using a temperature data logger with external sensors. The sensors were connected to the data logger by a cable. The temperature data logger with external sensors allowed good manipulation in the nest chamber, placement of the sensor away from the egg, and better fixation to prevent the sensor from being buried in the nest sediment or dislodged. The disadvantage of this type of data logger was that it required a small intervention in the burrow - the creation of a groove along the entire length of the corridor for the cable, at the end of which is the temperature sensor. The installation of the temperature sensor requires the use of a small camera. Temperature data was downloaded from the data logger using a cable connected to the computer (there was minimal interference when downloading data, as the datalogger was located approximately 1 m from the burrow). The most commonly used type of temperature logger to document incubation behaviour and monitor the breeding progress of birds by recording temperature fluctuations in nests is the iButton, which is a wireless temperature logger (Cooper and Phillips 2002, Hartman and Oring 2006, Schneider and McWilliams 2007, Croston et al. 2018, Croston et al. 2020). However, this type of data logger would not be suitable for collecting temperature data from a kingfisher nest hole. The handling of the temperature sensor in a closed nest hole would be problematic, as would fixing the sensor in the chamber to avoid possible burying of the sensor in the nest sediment.

5. Conclusion

Temperature fluctuations in an active natural nest of common kingfisher can be effectively used to monitor breeding phases and even a breeding success. The breeding phases and the transitions between them produce characteristic patterns (Fig. 9). Egg-laying occurs during the day, meaning that rapid temperature changes due to the presence of the female in the nest chamber only occur during the day, not at night. The beginning of incubation is associated with day and night temperature fluctuations in the nest chamber (the parental bird is present during both periods). During the chick feeding phase, there is noticeable difference between the presence of a parental bird with chicks and the presence of grown chicks alone. The fledging of the chick is represented on the temperature curve by a rapid drop, during the following night there is no temperature fluctuation in the nest chamber. The failure of breeding can also be determined from the course of temperatures - if the chicks die gradually in the nest chamber, the temperature in the nest chamber gradually decrease. Determining when the chicks have hatched from temperature curves alone is not always possible. To clarify this phenomenon, further measurements and the placement of a camera trap near the nest hole would be appropriate in a non-urban nest sites.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Czech Academy of Sciences within the program of the Strategy AV21 (project No. RP21 – Land conservation and restoration).

Appendix A. Overview of the Results of Inspections of Occupied Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) Nest Holes Carried Out with a Special Mini-Camera

| |

date of control |

result of inspecting the nesting chamber |

| Radotínský stream 2018 (1 June – 5 July) |

| |

1 June |

7 eggs |

| |

6 June |

the male was warming 7 eggs |

| |

15 June |

7 nestlings about 5 or 6 days old |

| |

25 June |

7 chicks about 14 or 15 days |

| |

3 July |

7 chicks about 22 or 23 days |

| |

4 July |

empty nest chamber |

|

Botič stream 2018 (18 June – 18 July) * |

| |

18 June |

7 eggs |

| |

27 June |

7 nestlings about 1 or 2 days old, the female was warming the nestlings |

| |

6 July |

7 chicks about 9 or 10 days |

| |

13 July |

7 chick deaths at 11 or 12 days of age |

| Rokytka stream 2019 (24 May – 11 July) |

| |

24 May |

2 eggs |

| |

31 May |

the male was warming 7 eggs |

| |

10 June |

the male was warming 7 eggs |

| |

20 June |

7 nestlings about 1 or 2 days old, the female was warming the nestlings |

| |

3 July |

7 chicks about 15 or 16 days |

| |

11 July |

empty nest chamber |

|

Botič stream 2019 (3 July – 30 July) * |

| |

3 July |

7 eggs |

| |

11 July |

the female was warming 6 eggs |

| |

19 July |

the female was warming 6 eggs |

| |

30 July |

7 chick deaths at 3 or 4 days of age |

| Radotínský stream (16 April – 28 May) |

| |

16 April |

6 eggs |

| |

25 April |

the female was warming 7 eggs |

| |

4 May |

the male was warming 6 nestlings about 1 or 2 days old and 1 egg |

| |

12 May |

4 chicks about 9 or 10 days old |

| |

22 May |

4 chicks about 18 or 19 days old |

| |

1 June |

2 eggs (the second breeding period) |

| Radotínský stream (1 June – 27 July) |

| |

1 June |

2 eggs |

| |

10 June |

the female was warming 7 eggs |

| |

19 June |

7 eggs |

| |

30 June |

7 nestlings about 3 or 4 day old |

| |

10 July |

7 chicks about 14 or 15 days old |

| |

20 July |

empty nest chamber |

Appendix B

The course of the temperature in the active nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) from the incubation in the 1st breeding event to the fledglings leave the nest hole at the end of the 2nd breeding event on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (from 16 April to 21 July). The boxes indicate individual phases of breeding events: - I1 incubation of the 1st clutch, I2 incubation of the 2nd clutch, F1 chick feeding period of the 1st clutch and F2 chick feeding period of the 2nd clutch, L2 indicates egg laying of the 2nd brood. Egg laying is defined as the period from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg, incubation as the period of egg heating (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch) and chick feeding is defined by the presence of chicks in the nest chamber (from hatching to the last chick fledging). The empty nest hole is defined from the time the last chick leaves the nest hole. (T1 - temperature in the occupied nest hole, T2 - "soil" temperature, Tmet - ambient temperature)

References

- Bueno-Enciso J., Barrientos R., Sanz J. J. (2017): Incubation behaviour of Blue Cyanistes caeruleus and Great Tits Parus major in a Mediterranean habitat. Acta Ornithologica 52/1: 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Bottitta G. E., Gilchrist H. G., Kift A. K., Meredith M. G. (2002): A pressure-sensitive wireless device for continuously monitoring avian nest attendance. Wildlife Society Bulletin 30: 1033–1038. [CrossRef]

- Bulla M., Valcu M., Dokter A. et al. (2016): Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirds. Nature 540: 109–113. [CrossRef]

- Clauser A. J. and McRae S. B. (2017): Plasticity in incubation behavior and shading by king rails Rallus elegans in response to temperature. Journal of Avian Biology 48: 479–488. [CrossRef]

- Cooper C. and Phillips T. (2002): Rhythm and bluebirds: new devices track temperatures and incubation rhythms at the nest. Birdscope. Newsletter of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Summer 16:8–9.

- Croston R., Hartman C. A., Herzog M. P., Casazza M. L., Ackerman J. T. (2018): A new approach to automated incubation recess detection using temperature loggers. Condor Ornithological Applications 120: 739-750. [CrossRef]

- Croston R., Hartman C. A., Herzog M. P., Casazza M. L., Feldheim C. L., Ackerman J. T. (2020): Timing, frequency, and duration of incubation recesses in dabbling ducks. Ecology and Evolution:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Čech, M., Čech, P. (2011). Diet of the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) in relation to habitat type: a summary of results from the Czech Republic. Sylvia 47: 33 – 47. (in Czech with abstract and extended summary in English).

- Čech, M., Čech, P. (2015). Non-fish prey in the diet of an exclusive fish-eater: the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis. Bird Study 62(4): 457 – 465. [CrossRef]

- Čech M. and Čech P. (2017): Effect of Brood Size on Food Provisioning Rate in Common Kingfishers Alcedo atthis. Ardea 105/1: 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Čech, M., Čech, P. (2022). The role of mammals as Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nest predators. Sylvia 58: 37–51. (in Czech with abstract and extended summary in English).

- Čech P. (Ed., 2007): Methodology of the Czech Association of Conservationists No. 34. Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), its conservation and research. – 1st edition. 02/19 ZO of the Czech Association of Nature Protectors ALCEDO: 1–102. Vlašim.

- Dallmann J. D., Anderson L. C., Raynor E. J., Powell L. A., Schacht W. H. (2016): iButton temperature loggers effectively determine Prairie Grouse nest absences. Great Plains Research 26/2: 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Dinsmore S. J., White G. C., Knopf F. L. (2002): Advanced techniques for modeling avian nest survival. Ecology 83/12: 3476–3488. [CrossRef]

- Grant T. A., Shaffer T. L., Madden E. M., Pietz P. J. (2005): Timespecific variation in passerine nest survival: new insights into old questions. Auk 122/2: 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Guillette L. M. and Healy S. D. (2019): Social learning in nest-building birds watching live-streaming video demonstrators. Integrative Zoology 14(2): 204-213. [CrossRef]

- Hadravová A. (2019): The river kingfisher also nests in Prague, but it doesn't have it simple. Živa 3: 137–139. Prague. (in Czech with abstract in English).

- Hartman C. A. and Oring L. W. (2006): An inexpensive method for remotely monitoring nest activity. Journal of Field Ornithology 77/4: 418–424. [CrossRef]

- Holmes R. T., Marra P. P., Sherry T. W. (1996): Habitat-specific demographic of breeding black-throated blue warbler (Dendroica caerulescens): implication for population dynamics. Journal of Animal Ecology 65/2: 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Hoover A. K., Rohwer F. C., Richkus K. D. (2004): From the field: evaluation of nest temperatures to assess female nest attendance and use of video cameras to monitor incubating waterfowl. Wildlife Society Bulletin 32/2: 581–587. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe I. R., Harrison J. O., Raynor IV E. J., Brown M. B., Powell L. A., Tyre A. J. (2018): Temperature, wind, vegetation, and roads influence incubation patterns of greater prairie chickens (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus) in the Nebraska Sandhills, USA. Canadian Journal of Zoology 97/2: 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Khamcha D., Powell L. A., Gale G. A. (2018): Effects of roadside edge on nest predators and nest survival of Asian tropical forest birds. Global ekology and conservation 16: 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Kosztolanyi A. and Szekely T. (2002): Using a transponder system to monitor incubation routines of snowy plovers. Journal of Field Ornithology 73/2: 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Loos E. R. and Rohwer F. C. (2004): Laying-stage nest attendance and onset of incubation in prairie nesting ducks. Auk 121/2: 587–599. [CrossRef]

- Manlove C. A. and Hepp G. R. (2000): Patterns of nest attendance in female wood ducks. Condor 102:286–291. [CrossRef]

- Meteogram.cz. [online]. Available from: www.meteogram.cz Cited: 15.2.2024.

- Normant C. J. (1995): Incubation patterns in Harris’ sparrows and white- crowned sparrows in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Journal of Field Ornithology 66/4: 553–563.

- Ruiz-De-Castañeda R., Vela A.I., Lobato E., Briones V., Moreno J. (2012): Early onset of incubation and eggshell bacterial loads in a temperate-zone cavity-nesting passerine. The Condor 114/1: 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2011.100230. [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team, R. (2017): A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

- Robinson S. K., Thompson F. R. III, Donovan T. M., Whitehead D. R., Faaborg J. (1995): Regional forest fragmentation and the nesting success of migratory birds. Science 267: 1987–1990. [CrossRef]

- Rotella J. J., Dinsmore S. J., Shaffer T. L. (2004): Modeling nest-survival data: a comparison of recently developed methods that can be implemented in MARK and SAS. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 27/1: 187–205.

- Schneider E. G. and McWilliams S. R. (2007): Using Nest Temperature to Estimate Nest Attendance of Piping Plovers. Journal of Wildlife Management 71/6: 1998-2006. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson M. D., Schulte L. A., Klaver R. W., Niem J. (2021): Miniature temperature data loggers increase precision and reduce bias when estimating the daily survival rate for bird nests. Journal of Field Ornithology 92/4: 492–505. [CrossRef]

- Stetten G., Koontz F., Sheppard C., Koontz C. (1990): Telemetric egg for monitoring nest microclimate of endangered birds. International telemetring konference. Book Subtitle ITC/USA/90 26: 321-327.

- Sullivan J. D., Marbán P. R., Mullinax J. M., Brinker D. F., McGowan P. C., Callahan C. R., Prosser D. J. (2020): Assessing nest attentiveness of Common Terns via video cameras and temperature loggers. Avian Research 11/1: 18 p. [CrossRef]

- Sutti F. and Strong A. M. (2014): Temperature Loggers Decrease Costs of Determining Bird Nest Survival. Wildlife Society Bulletin 38/4: 831–836. [CrossRef]

- Vlček V., Kestřánek J., Kříž H., Novotný S., Píše J. (1984): Streams, Rivers and Reservoirs. Academia, Praha.

- Weidinger K. (2006): Validating the use of temperature data loggers to measure survival of songbird nests. Journal of Field Ornithology 77/4: 357–364. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A diagram showing individual phases of one complete breeding event of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) according to the work of Čech (2007), Hadravová (2019) and Čech and Čech (2017, 2022) (modified). Ia) A new nest burrowed in the soil of the nest wall / an old nest used in one of the previous breeding events. Ib) Nest cleaning and preparation of the thin, soft bed for eggs from regurgitated pellets (composed of undigested prey remains, particularly fish bones; for details see Čech and Čech, 2011, 2015). II) Egg laying with female presence in the nest only during the daylight period. III) Egg incubation with female being present in the nest mostly during the night and male mostly during the day. IVa) Chick hatching and start of chick feeding with parental bird still present (and incubating) in the nest for next few days. IVb) Chick feeding by both parental birds (male provisioning usually prevailed). V) Chick fledging and consecutive leaving of the nest. VIa) Feeding of fledglings out of the nest. VIb) Chasing of young birds away from the nest site by a parental bird. †) Eggs destroyed by the collapse of the nest wall, by predators or by a rival female in a polygyny mating system (when this system failed). ††) The brood destroyed by a flood water (drowned), by predators (eaten) or within the period of severe food provisioning problems (starved).

Figure 1.

A diagram showing individual phases of one complete breeding event of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) according to the work of Čech (2007), Hadravová (2019) and Čech and Čech (2017, 2022) (modified). Ia) A new nest burrowed in the soil of the nest wall / an old nest used in one of the previous breeding events. Ib) Nest cleaning and preparation of the thin, soft bed for eggs from regurgitated pellets (composed of undigested prey remains, particularly fish bones; for details see Čech and Čech, 2011, 2015). II) Egg laying with female presence in the nest only during the daylight period. III) Egg incubation with female being present in the nest mostly during the night and male mostly during the day. IVa) Chick hatching and start of chick feeding with parental bird still present (and incubating) in the nest for next few days. IVb) Chick feeding by both parental birds (male provisioning usually prevailed). V) Chick fledging and consecutive leaving of the nest. VIa) Feeding of fledglings out of the nest. VIb) Chasing of young birds away from the nest site by a parental bird. †) Eggs destroyed by the collapse of the nest wall, by predators or by a rival female in a polygyny mating system (when this system failed). ††) The brood destroyed by a flood water (drowned), by predators (eaten) or within the period of severe food provisioning problems (starved).

Figure 2.

A map of Prague district with marked common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nests where temperature was continuously measured using temperature data loggers. Red points with numbers indicate the locations of kingfisher nests: 1- on the Radotínský stream in 2018, 2 – on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (two consecutive breeding attempts were successfully carried out in one single nest), 3 - on the Botič stream in 2018, 4 – on the Botič stream in 2019, 5 – on the Rokytka stream in 2019. The brown point marked AT indicates the location of the temperature data logger for measuring the ambient temperature.

Figure 2.

A map of Prague district with marked common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nests where temperature was continuously measured using temperature data loggers. Red points with numbers indicate the locations of kingfisher nests: 1- on the Radotínský stream in 2018, 2 – on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (two consecutive breeding attempts were successfully carried out in one single nest), 3 - on the Botič stream in 2018, 4 – on the Botič stream in 2019, 5 – on the Rokytka stream in 2019. The brown point marked AT indicates the location of the temperature data logger for measuring the ambient temperature.

Figure 3.

Installation of a temperature data logger in the nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis): a) temperature data logger after installation (hidden in the surrounding vegetation), b) installation of a temperature data logger prior to concealing it in the surrounding vegetation, c) a temperature data logger hidden in the cut-off part of a PET bottle suspended from a tree root, d) Placement of the temperature sensor in the nest chamber (undisturbed kingfisher male still heating the eggs during a brief control with the mini-camera). The blue arrow indicates an occupied nest hole, the yellow arrow indicates the location of the handmade hole with the second temperature sensor, the red frame indicates the data logger in the cut-off part of a PET bottle.

Figure 3.

Installation of a temperature data logger in the nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis): a) temperature data logger after installation (hidden in the surrounding vegetation), b) installation of a temperature data logger prior to concealing it in the surrounding vegetation, c) a temperature data logger hidden in the cut-off part of a PET bottle suspended from a tree root, d) Placement of the temperature sensor in the nest chamber (undisturbed kingfisher male still heating the eggs during a brief control with the mini-camera). The blue arrow indicates an occupied nest hole, the yellow arrow indicates the location of the handmade hole with the second temperature sensor, the red frame indicates the data logger in the cut-off part of a PET bottle.

Figure 4.

The course of the temperature in the active nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) from the incubation to the chicks fledging a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018 (from 1 June to 5 July), b) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (from 24 May to 11 July), c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 1st breeding event from 16 April to 28 May), d) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 2nd breeding event from 30 May to 28 July). Vertical lines separate different phases of breeding (lines placed based on assumed date and time of breeding phase; length of breeding phases may vary among breeding periods or seasons): L egg laying (from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg), I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch), F chick feeding period (the period when the chicks are present in the nest chamber). (T1 - temperature in the occupied nest hole, T2 - "soil" temperature, Tmet - ambient temperature).

Figure 4.

The course of the temperature in the active nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) from the incubation to the chicks fledging a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018 (from 1 June to 5 July), b) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (from 24 May to 11 July), c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 1st breeding event from 16 April to 28 May), d) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 2nd breeding event from 30 May to 28 July). Vertical lines separate different phases of breeding (lines placed based on assumed date and time of breeding phase; length of breeding phases may vary among breeding periods or seasons): L egg laying (from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg), I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch), F chick feeding period (the period when the chicks are present in the nest chamber). (T1 - temperature in the occupied nest hole, T2 - "soil" temperature, Tmet - ambient temperature).

Figure 5.

The course of the temperature in the active nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) from the incubation to the death of chicks a) on the Botič stream in 2018 (from 18 June to 18 July), b) on the Botič stream in 2019 (from 3 July to 30 July). Vertical lines separate different phases of breeding (lines placed based on assumed date and time of breeding phase; length of breeding phases may vary among breeding periods or seasons): I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the nestlings hatch), F chick feeding period (the period when the chicks are present in the nest chamber). (T1 - temperature in the occupied nest hole, T2 - "soil" temperature, Tmet - ambient temperature).

Figure 5.

The course of the temperature in the active nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) from the incubation to the death of chicks a) on the Botič stream in 2018 (from 18 June to 18 July), b) on the Botič stream in 2019 (from 3 July to 30 July). Vertical lines separate different phases of breeding (lines placed based on assumed date and time of breeding phase; length of breeding phases may vary among breeding periods or seasons): I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the nestlings hatch), F chick feeding period (the period when the chicks are present in the nest chamber). (T1 - temperature in the occupied nest hole, T2 - "soil" temperature, Tmet - ambient temperature).

Figure 6.

Temperature difference during egg laying in the occupied nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) a) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (from 25 May to 29 May – egg laying from the 2nd egg), b) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (2nd breeding event; from 30 May to 5 June); expressed using deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. Vertical lines separate individual phases of breeding event: L egg laying (from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg), I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch). (D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature).

Figure 6.

Temperature difference during egg laying in the occupied nest hole of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) a) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (from 25 May to 29 May – egg laying from the 2nd egg), b) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (2nd breeding event; from 30 May to 5 June); expressed using deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. Vertical lines separate individual phases of breeding event: L egg laying (from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg), I incubation (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch). (D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature).

Figure 7.

Transition between incubation and feeding phase (hatching) of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) recorded by the temperature data a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018, b) on the Rokytka stream in 2019, c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (1st breeding event), d) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (2nd breeding event), e) on the Botič stream in 2018, f) on the Botič stream in 2019 expressed by deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. (D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature). The day on which the chicks hatched is indicated in blue, and a red line separates unsuccessful breedings (two graphs below the line).

Figure 7.

Transition between incubation and feeding phase (hatching) of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) recorded by the temperature data a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018, b) on the Rokytka stream in 2019, c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (1st breeding event), d) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (2nd breeding event), e) on the Botič stream in 2018, f) on the Botič stream in 2019 expressed by deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. (D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature). The day on which the chicks hatched is indicated in blue, and a red line separates unsuccessful breedings (two graphs below the line).

Figure 8.

Fledging of the chicks of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) recorded by the temperature data a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018, b) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 1st breeding event), and c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 2nd breeding event), and dying of the chicks d) on the Botič stream in 2018, and e) on the Botič stream in 2019 expressed using deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature. The day on which the chicks fledged is indicated in blue, the red line separates the unsuccessful broods (two graphs below the line).

Figure 8.

Fledging of the chicks of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) recorded by the temperature data a) on the Radotínský stream in 2018, b) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 1st breeding event), and c) on the Radotínský stream in 2020 (the 2nd breeding event), and dying of the chicks d) on the Botič stream in 2018, and e) on the Botič stream in 2019 expressed using deciles calculated for separate day and night data fractions. D1 – 1st decile, D9 - 9th decile, min. – minimum day/night temperature, max. – maximum day/night temperature. The day on which the chicks fledged is indicated in blue, the red line separates the unsuccessful broods (two graphs below the line).

Figure 9.

Temperature difference during individual breeding phases of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (blue colour) and on the Radotínský stream in 2020 - the 2nd breeding event (green colour). Egg laying is defined as the period from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg, incubation as the period of egg heating (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch) and chick feeding is defined by the presence of chicks in the nest chamber (from hatching to the last chick fledging). The empty nest hole is defined from the time the last chick leaves the nest hole. The box plot displays: the minimum value (the lower whisker), Q1 (the lower bound of the box), the median (the line in the middle of the box), Q3 (the upper bound of the box), and the maximum value (the upper whisker).

Figure 9.

Temperature difference during individual breeding phases of the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) on the Rokytka stream in 2019 (blue colour) and on the Radotínský stream in 2020 - the 2nd breeding event (green colour). Egg laying is defined as the period from the laying of the first egg to the laying of the last egg, incubation as the period of egg heating (from the time the last egg is laid until the chicks hatch) and chick feeding is defined by the presence of chicks in the nest chamber (from hatching to the last chick fledging). The empty nest hole is defined from the time the last chick leaves the nest hole. The box plot displays: the minimum value (the lower whisker), Q1 (the lower bound of the box), the median (the line in the middle of the box), Q3 (the upper bound of the box), and the maximum value (the upper whisker).

Table 1.

Parameters of individual common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nest holes, in which temperature was continuously measured using temperature data loggers (Prague district, Czech Republic).

Table 1.

Parameters of individual common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nest holes, in which temperature was continuously measured using temperature data loggers (Prague district, Czech Republic).

| |

GPS coordinates of the nest |

orientation of the nest wall |

material of the nest hole |

the height of the nest hole above the water level |

the depth of the nest hole, chamber including |

| Radotínský stream (length 22.8 km, average annual discharge 0.17 m3 s-1) ** |

| breeding season 2018 (1)* |

49°59'51.699"N, 14°19'35.110"E |

south-east |

clay |

105 cm |

68 cm |

| breeding season 2020 - 2 breeding events (2)* |

49°59'48.332"N, 14°18'18.762"E |

south-east |

clay |

86 cm |

39 cm |

| Botič stream (length 34.5 km, average annual discharge 0.53 m3 s -1) ** |

| breeding season 2018 (3)* |

50°3'3.689"N, 14°31'15.127"E |

south |

clay loam |

136 cm |

75 cm |

| breeding season 2019 (4)* |

50°3'3.693"N, 14°31'15.085"E |

south |

clay loam |

159 cm |

59 cm |

| Rokytka stream (length 37.5 km, average annual discharge 0.50 m3 s -1) ** |

| breeding season 2019 (5)* |

50°6'27.503"N, 14°31'18.140"E |

south-east |

clay loam |

87 cm |

60 cm |

Table 2.

Temperature values (oC; min., max ., mean) for each breeding phase of individual common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nests at Radotínský, Botič and Rokytka streams in which temperature and parallel measurements of soil and ambient air temperature were taken.

Table 2.

Temperature values (oC; min., max ., mean) for each breeding phase of individual common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) nests at Radotínský, Botič and Rokytka streams in which temperature and parallel measurements of soil and ambient air temperature were taken.

| |

egg laying |

egg incubation |

chick feeding |

| |

min. |

max. |

mean |

min. |

max. |

mean |

min. |

max. |

mean |

| Radotínský stream 2018 (1 June – 5 July) – 7 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

no data |

15.3 |

19.4 |

16.6 |

16.8 |

27.9 |

20.3 |

| „soil“ temperature |

15.6 |

16.0 |

15.8 |

14.6 |

16.7 |

15.7 |

| air temperature |

12.8 |

35.7 |

22.7 |

7.1 |

36.2 |

19.3 |

| Botič stream 2018 (18 June – 18 July)* - 7 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

no data |

17.6 |

27.9 |

19.1 |

17.4 |

32.1 |

22.4 |

| „soil“ temperature |

15.2 |

18.4 |

16.9 |

15.1 |

17.5 |

16.0 |

| air temperature |

10.5 |

36.2 |

18.6 |

7.1 |

35.8 |

19.9 |

| Rokytka stream 2019 (24 May – 11 July) – 7 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

12.8 |

16.2 |

14.2 |

14.6 |

21.5 |

18.3 |

20.5 |

31.8 |

24.4 |

| „soil“ temperature |

12.8 |

14.6 |

13.8 |

13.9 |

20.5 |

17.5 |

19.2 |

22.2 |

20.7 |

| air temperature |

9.2 |

33.7 |

17.4 |

5.4 |

40.0 |

22.2 |

8.8 |

38.3 |

21.7 |

| Botič stream 2019 (3 July – 30 July)* - 4 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

no data |

19.0 |

28.8 |

24.4 |

breeding failed |

| „soil“ temperature |

17.1 |

20.4 |

18.1 |

| air temperature |

8.8 |

32.0 |

18.0 |

| Radotínský stream 2020 – 1st breeding period (16 April – 28 May) – 4 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

no data |

8.6 |

14.0 |

11.7 |

11.1 |

16.9 |

13.8 |

| „soil“ temperature |

7.0 |

10.2 |

8.7 |

9.1 |

10.8 |

9.9 |

| air temperature |

1.3 |

27.5 |

12.9 |

0.5 |

30.4 |

13.3 |

| Radotínský stream 2020 – 2nd breeding period (30 May – 20 July) – 7 chicks |

| occupied nest hole |

11.2 |

14.6 |

12.2 |

13.9 |

18.0 |

15.9 |

16.8 |

25.1 |

19.6 |

| „soil“ temperature |

10.5 |

11.4 |

10.8 |

11.4 |

14.4 |

13.2 |

14.1 |

15.7 |

14.9 |

| air temperature |

6.5 |

29.5 |

15.6 |

9.7 |

32.6 |

18.0 |

8.5 |

38.5 |

20.1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).