1. Introduction

Dengue is among the most important mosquito-borne viral-disease worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Dengue is caused by four genetically related viruses, grouped in serotypes 1-4 [

1,

3]. Its prevalence spans across tropical and subtropical regions and imposes a financial burden to public health. Climate change, urbanization, and the lack of an effective control of the vector [

5] have affected the distribution pattern of the main vector,

Aedes aegypti, which also has led to changes in dengue incidence [

6] and increase in the frequency of epidemics [

7,

8,

9,

10]. The approaches to control dengue have focused on the eradication of the vector and the development of a vaccine. In the Americas, eradication of the mosquito failed due to limitations in the implementation of the control regimes across countries, and the onset of mosquito resistance to insecticides [

11]. Despite the efforts to develop an effective vaccine [

12], there is only a single licensed vaccine implemented in multiple endemic countries, and its use is restricted only to individuals with a previous dengue virus infection [

13]. Furthermore, the high genetic variability of DENV [

14,

15] and the circulation of multiple serotypes in endemic regions [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], require vaccines to protect against the 4 serotypes.

The limitations of vaccine development have opened new avenues to antiviral research focused on host targeted antiviral (HTA). HTA have shown promising results against molecular and cellular targets used by a broad range of viruses including Dengue virus (DENV) [

21,

22]; Hepatitis C virus (HCV) [

23], West Nile (WNV) [

21], SARS-CoV-2 [

24,

25,

26], among others. Moreover, multiple studies have elucidated key cellular mechanisms for dengue virus replication, which can potentially be used for cell-based therapies [

22,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. ABL-family proteins are non-receptor tyrosine kinase proteins and comprises one of the best conserved branches of the tyrosine kinases. Each ABL protein contains an SH3-SH2-TK (Src homology 3-Src homology 2-tyrosine kinase) domain cassette, which autoregulates kinase activity. This cassette is coupled to an actin-binding and bundling domain, which makes ABL proteins capable of connecting phosphorylation with actin-filament reorganization [

34]. ABL protein is encoded by the

ABL1 gene which is activated by growth factors, cytokines, and other signals. Its activation stimulates cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, cell death, retraction or migration, and actin reorganization through its C-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD), which specifies location to F-actin. The large C-terminal region of the mammalian ABL protein contains three functional nuclear localization signals (NLS) that drive the nuclear entry of ABL and DNA interaction [

34,

35,

36].

Studies of the interactions of various pathogens with the cellular machinery have identified the involvement of ABL during infections at the intracellular level, playing different roles during infectious processes of bacteria and viruses, with a crucial impact on antiviral immunity [

37], viral replication [

38], microbial invasion by endocytosis and membrane-fusion [

39], release from host cells, actin-based motility [

40], pedestal formation, as well as cell-cell dissociation involved in epithelial barrier disruption and other responses [

41,

42,

43]. Interestingly, c-Abl participates in different viral infections through the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular trafficking [

44,

45,

46,

47] or by direct interaction with viral proteins [

48,

49]. Specifically, c-Abl regulates attachment of polyomavirus, entry and genome release of HIV and coxsackievirus [

46,

47,

50] and actin tail formation and virion budding of Vaccinia virus [

44,

45]. In the case of DENV virus, c-Abl associates with post-entry events [

51], however the mechanism remains unknown.

Increasing evidence shows that infection by DENV virus remodels actin filaments, microtubules and vimentin to promote viral entry, replication and budding [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Particularly, actin dynamics is critical for viral entry, synthesis of viral structural proteins, and viral release [

56,

57]. Here, we show that either silencing or pharmacological inhibition of c-Abl during DENV infection leads to accumulation of the envelope protein (ENV) at the intracellular level through a mechanism involving actin remodeling. These findings shed light on key cellular mechanisms for DENV infection, that can be targeted for cell-based treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Antibodies

Imatinib mesylate inhibitor (STI571) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals, USA and was dissolved in DMSO at 1mM and stored as a stock solution at -20°C. Primary α-Envelope antibody (α-ENV) and anti Phospho Crk II were purchased from MERCK Millipore. Primary anti c-ABL antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary Alexa Fluor 594 antibody and phalloidin-594 were purchased from Molecular Probes. Hoechst 33258 was purchased from Invitrogen. L-15 medium and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), were supplied by Merck. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and tissue culture antibiotic cocktail Penicillin/Streptomycin (PS) were provided by Invitrogen.

2.2. Cell Lines and Virus

Dengue virus serotype 2 New Guinea strain (DENV-2 NGS) was provided by María Elena Peñaranda and Eva Harris (Sustainable Sciences Institute and the University of California, Berkeley. U.S.A). Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) was used for all experiments and was maintained in DMEM (GIBCO) and supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% for maintenance or 2% for infection experiments, with penicillin (100U/mL)-streptomycin (100ug/mL) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. C6/36 HT cells were grown in L-15 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100U/mL)-streptomycin (100ug/mL) at 34°C to grow DENV-2 NGS. For viral propagation C6/36 HT cells were infected at MOI 0.01 for seven days, and the supernatant was collected and frozen at -80°C to further viral titration in Vero cells.

2.3. Plasmids, Transfection and RNAi

ABL1 gene silencing was achieved using plasmid-based artificial microRNA (miRNA) expression vectors that co-express a GFP reporter [

58]. Specifically, artificial miRNAs harboring small interfering RNAs targeting

ABL1 (miABL1) or scrambled control sequence (miScrambled) were cloned into the expression plasmid pFBAAVmU6mcs-CMVeGFP SV40pA, which is available from the Viral Vector Core at Carver College of Medicine (University of Iowa, USA). Plasmid transfections were done with the Lipofectamine 2000 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following manufacturer´s instructions.

The transfection efficiency of the plasmids pFBAAVmU6miABL1-CMVeGFP SV40pA (mi

ABL1) and pFBAAVmU6miScramble-CMVeGFPSV40pA (scrambled version) was confirmed through the expression of the GFP reporter [

58,

59].

2.4. Imatinib Cytotoxicity and Inhibition Treatments

Cytotoxicity was assessed using the MTT (3- (4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl) -2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. IC50 was determined in Vero cells following a previously standardized protocol for DENV infection. Briefly, Vero cells were seeded at 80% confluence in 96-well plates and incubated with serial dilutions of imatinib ranging between 0,078 nM to 160 μM for either 24 h or 6 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. After each time point, the medium was replaced with 50 μL of MTT followed by 2.5 h at 37°C. Isopropanol was added to dissolve the formazan crystals to further measure absorbance by spectrometry (Benchmark reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). IC50 values were obtained using a linear regression model.

2.5. Virus Binding, Entry and Post-Entry Assays

To determine the effect of imatinib in the different steps of DENV-2 infection, Vero cells were used at a confluency of 80% in 24-well culture plates (2.5 × 104 cells per well). For viral attachment, Vero cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour, followed by infection with DENV-2 (MOI 0.01) in the presence of imatinib (1.25 μM to 10 μM) or without treatment (mock) for 1 h at 4°C. To evaluate viral entry, Vero cells were treated with imatinib (1.25 μM to 10 μM) for 1 h and 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 followed by DENV-2 infection (MOI 1). To evaluate post-entry steps, Vero cells were infected with DENV-2 (MOI 1) for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, and further incubated with the overlay media containing imatinib (1.25 μM to 10 μM) or without treatment (mock). After each treatment condition, an overlay of 1.5% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) was added to the cells. Infected cells were incubated for 6 days at 37°C and CO2 at 5%, and subsequently fixed and stained with 2.5% crystal violet for plaque counting. Plaque forming units (PFU) were counted from three 3 independent experiments.

2.6. Evaluation of Imatinib in c-Crk Phosphorylation

To evaluate the effect of imatinib in c-Abl kinase inhibition, the c-CrkII adapter protein was used as a read-out molecule, given its phosphorylation depends directly on c-Abl kinase activity. c-Crk II phosphorylation at tyrosine 221 was quantified in Vero cells (2.5 × 104 Vero cells per glass coverslips) and treated with imatinib for 24 hours, then the cells were washed with 1X PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and permeabilized with triton X-100. Next, the cells were incubated with anti Phospho-Crk II and Alexa fluor 594 for cytometry detection (BD Facs Canto II, Becton Dickinson). The Analysis was done using FlowJo software from 3 independent experiments.

2.8. c-abl Silencing and Its Downstream Effect on c-CrkII Phosphorylation

c-Abl and phospho c-CrkII expression was measured at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h post-transfection to determine silencing efficiency. Vero cells were transfected with pFBAAVmU6miABL1-CMVeGFP SV40pA (amiABL1) or pFBAAVmU6miScramble-CMVeGFPSV40pA (scrambled) in triplicate and the expression of c-Abl and phospho c-CrkII was measured at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h post-transfection in 96-well culture plates by In-Cell Western (LICOR Biosciences). Cells were fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized with triton X-100 and immuno-labelled with anti c-Abl or anti Phospho Crk II and detected with IRDye 680LT (LI-COR Biosciences). Actin was used as loading control and detected with IRDye 800CW (LI-COR Biosciences). In addition, the expression of c-Abl and phospho c-CrkII was evaluated at 48 and 72 h post-transfection by cytometry. Cytometry results were analyzed with FlowJo software form three independent experiments.

2.9. Effect of c-abl Silencing on DENV-2 Infection

The effect of c-Abl silencing on DENV-2 infection was determined through the quantification of DENV envelope (ENV) protein at 1h.p.i and 22 h.p.i by cytometry (FACS Canto) and fluorescence microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Axio Observer Z1). For ENV detection at 1h.p.i, cells were transfected for 46 hours, then were infected with MOI 5 for 1h at 4°C and 1h at 37°C with 5% CO2. For detection at 22 h.p.i, cells were transfected for 24 hours, then were infected with MOI 5 for 1h at 4°C and 22h at 37°C with 5 % CO2. At the end of the infection, Vero cells were washed with 1X PBS, trypsinized, fixed with 4% PFA in cytoskeletal buffer, blocked with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and immunolabelled with primary α-Envelope antibody (α-ENV) and detected with alexa Fluor 594. Data was analyzed from three independent experiments.

3. Statistical Analysis

Analyses show the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments. p values were determined by two tailed unpaired Student´s t test (***, p < 0.001; **, 0.001 < p < 0.01; *, 0.01 < p < 0.05) using SPSS v.20 software and Graphpad Prism 5. Microscopy fluorescence images were analyzed with Image J software.

4. Results

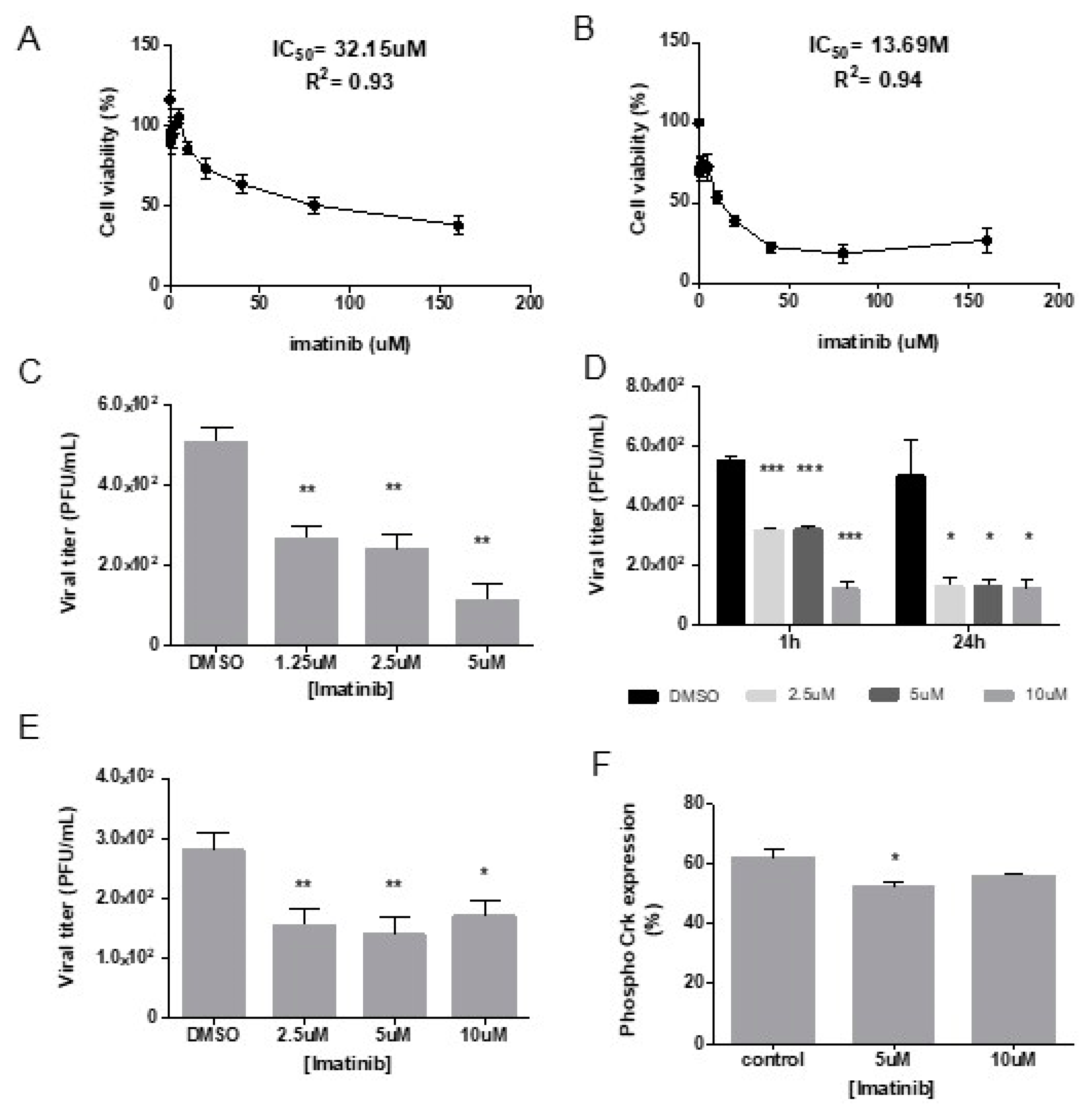

4.1. Inhibition of c-Abl Kinase with Imatinib Reduces Binding, Entry and Post-Entry Events during DENV-2 Infection

We used the inhibitor imatinib (STI571) to determine the role of c-Abl kinase activity during DENV-2 infection. We first evaluated the cytotoxicity of imatinib in Vero cells and determined the inhibitory concentration 50 (IC

50) to establish a concentration range below the IC

50 for further experiments. We determined an IC

50 of 32.15 μM in cells treated with imatinib for 24 h and IC

50 of 13.69 μM in cells treated for 6 days (

Figure 1A,B). We next evaluated the effect of 1.25 μM to 10 μM of imatinib in viral attachment, entry, and post-entry steps.

For binding assays, the quantification of PFU showed a significant reduction at concentrations of 1.25 μM, 2.5 μM and 5 μM, with a reduction of 4.6 folds at 5 μM compared to DMSO control (** P=0.01) (

Figure 1C).

During viral entry, a consistent decline in titer was observed in cells incubated during 1h and 24 h in the presence of imatinib, being 10 μM the concentration that showed the highest reduction in viral entry. Interestingly, the incubation with imatinib during 24 h, revealed that 2.5 and 5 μM of imatinib led to a PFU reduction, closer to that obtained with 10 μM (

Figure 1D).

During post-entry events, a significant inhibition of DENV-2 PFUs was observed when imatinib was used at 2.5 μM and 5 μM (

Figure 1E).

To confirm the effect of imatinib on c-Abl kinase inhibition, c-Crk II phosphorylation at tyrosine 221 was quantified in Vero cells treated with imatinib for 24 h. c-Crk II phosphorylation was significantly reduced at 5uM of imatinib compared with untreated cells (

Figure 1F).

Taken together, these results show that a concentration of 5 μM imatinib inhibits DENV-2 infection in Vero cells through inhibition of kinase activity.

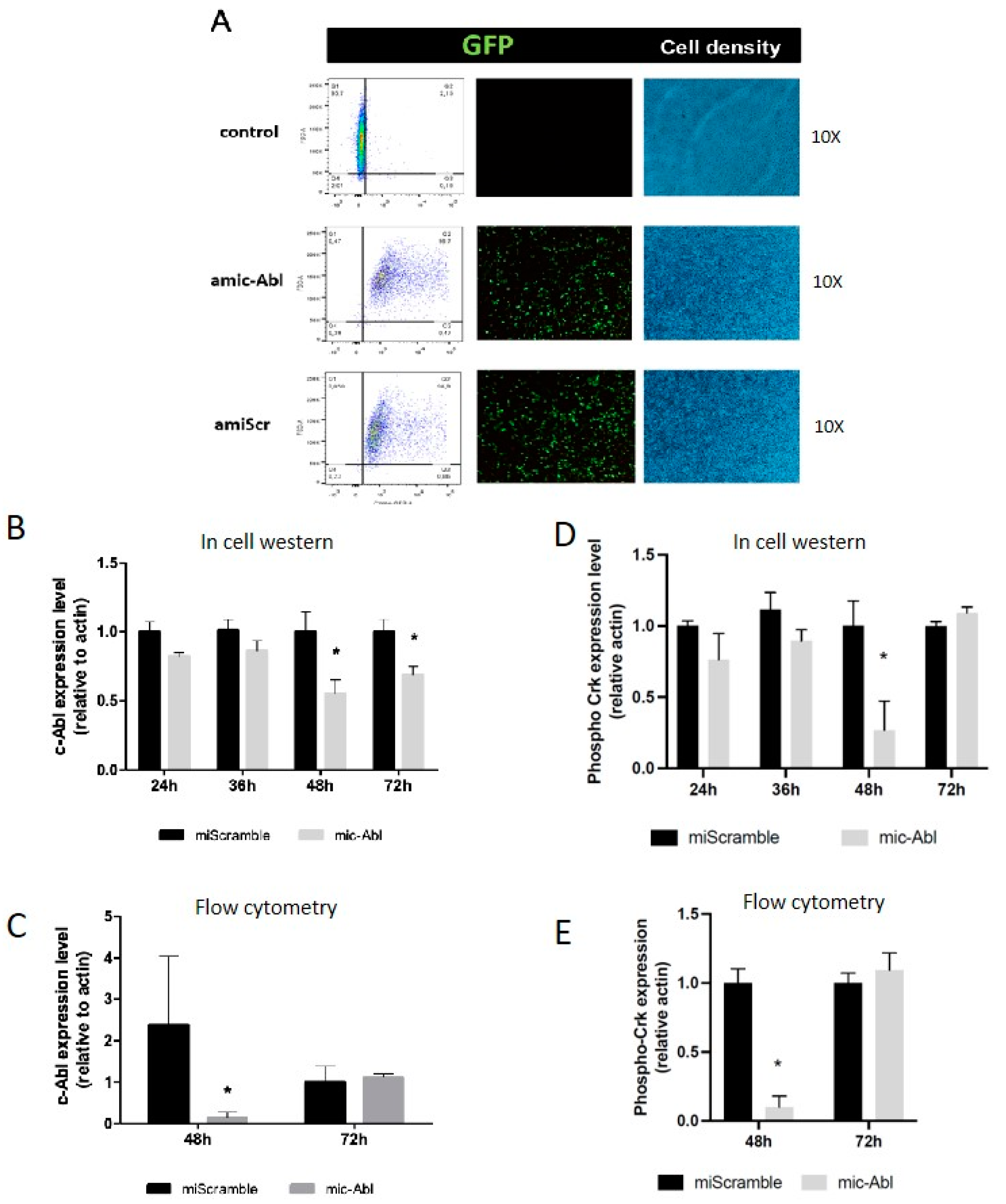

4.2. c-Abl Decrease through ABL1 Knockdown Leads to DENV-2 Envelope Protein Accumulation on Infected Cells

We used a plasmid-based artificial mi

ABL1 to knockdown

ABL1 expression. This expression vector co-expresses a GFP reporter and we determined the efficiency of transfection measuring the percentage of GFP+ cells at 48 h post-transfection. We found a 95% efficiency of transfection in cells transfected with mi

ABL1 or

miScrambled control plasmids (

Figure 2A).

c-Abl expression was measured at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h post-transfection by In Cell Western (ICW) (

Figure 2B) and at 48 and 72 h post-transfection by flow cytometry (

Figure 2C). c-Abl abundance was significantly decreased at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection in

miABL1 transfected cells compared with scrambled transfected cells, showing a 50% decline at 48 h post-transfection. Crk phosphorylation was measured at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h post-transfection by ICW (

Figure 2D) and at 48 and 72 h post-transfection by flow cytometry (

Figure 2E). Phospho Crk level at tyrosine 221 was significantly decreased at 48 h of post-transfection as observed by ICW and flow cytometry, compared to control without artificial miRNA treatment.

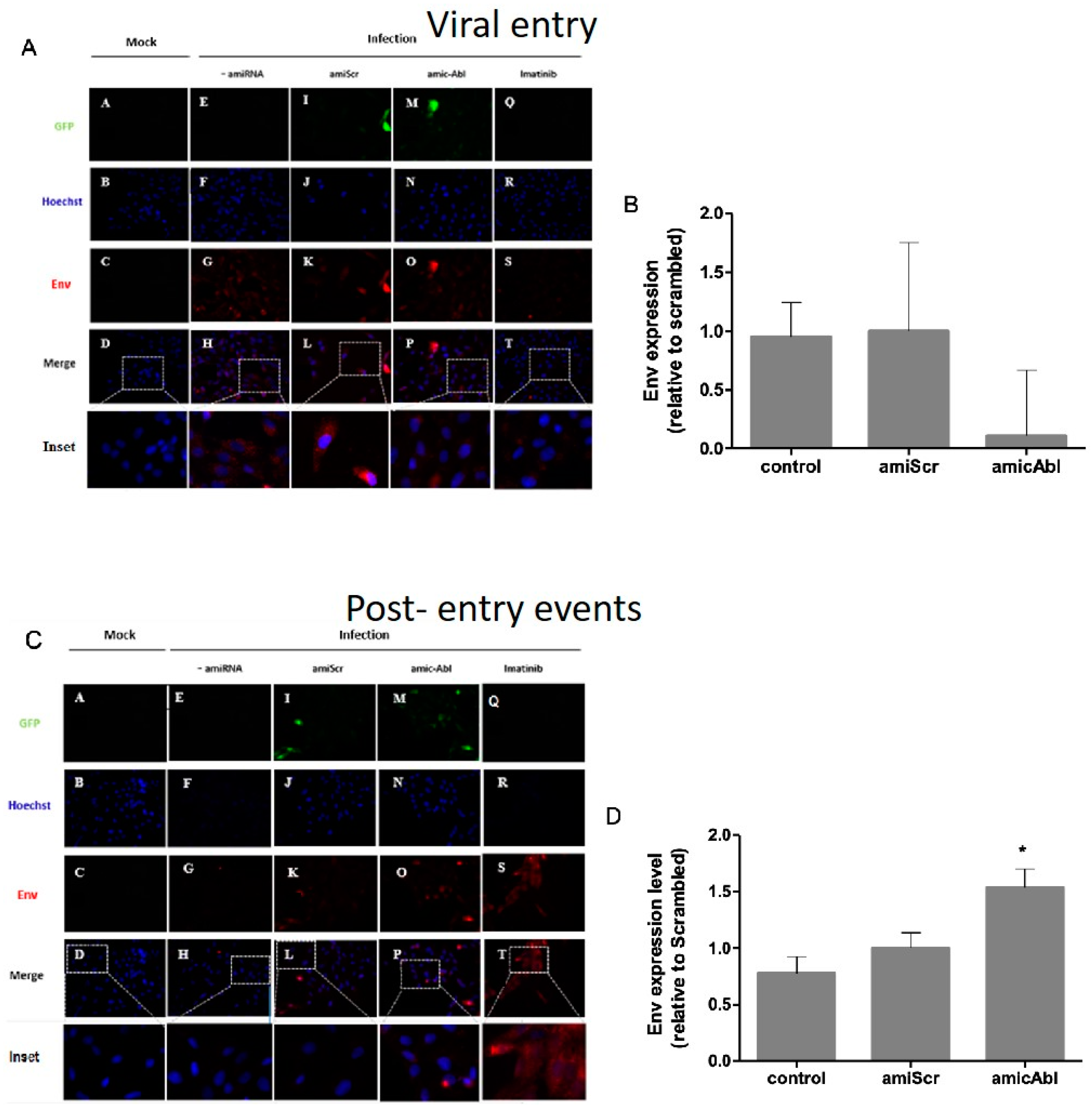

To further analyze the role of c-Abl in viral entry and post-entry events, we quantified envelope (Env) protein during

ABL1 silencing. Based on immunofluorescence assays, no statistically significant change was observed on ENV protein in Vero cells during viral entry in

ABL1 knockdown compared to scrambled control (

Figure 3A,B). In infection controls, either infection alone or under miScrambled transfection, ENV protein is distributed along the cell revealing either a punctate appearance or presenting as bigger blurred spots. Additionally, both in mi

ABL- infected cells and imatinib-infected cells, we observed a decrease in the quantity of small spots or cumulus of Env protein and their distribution is near the periphery of the cell (

Figure 2A). During post-entry events, ENV protein increased in mi

ABL1-treated cells compared with miScrambled (

Figure 3C,D). A pattern of blurred spots with a perinuclear distribution was observed, both in both

ABL1 knockdown-infected cells and imatinib treated-infected cells. In addition, a decrease of ENV protein as spots or cumulus was detected in infection controls, either infection alone or under miScrambled transfection (

Figure 3C). These findings suggest that c-Abl is required for DENV-2 post-entry events and release.

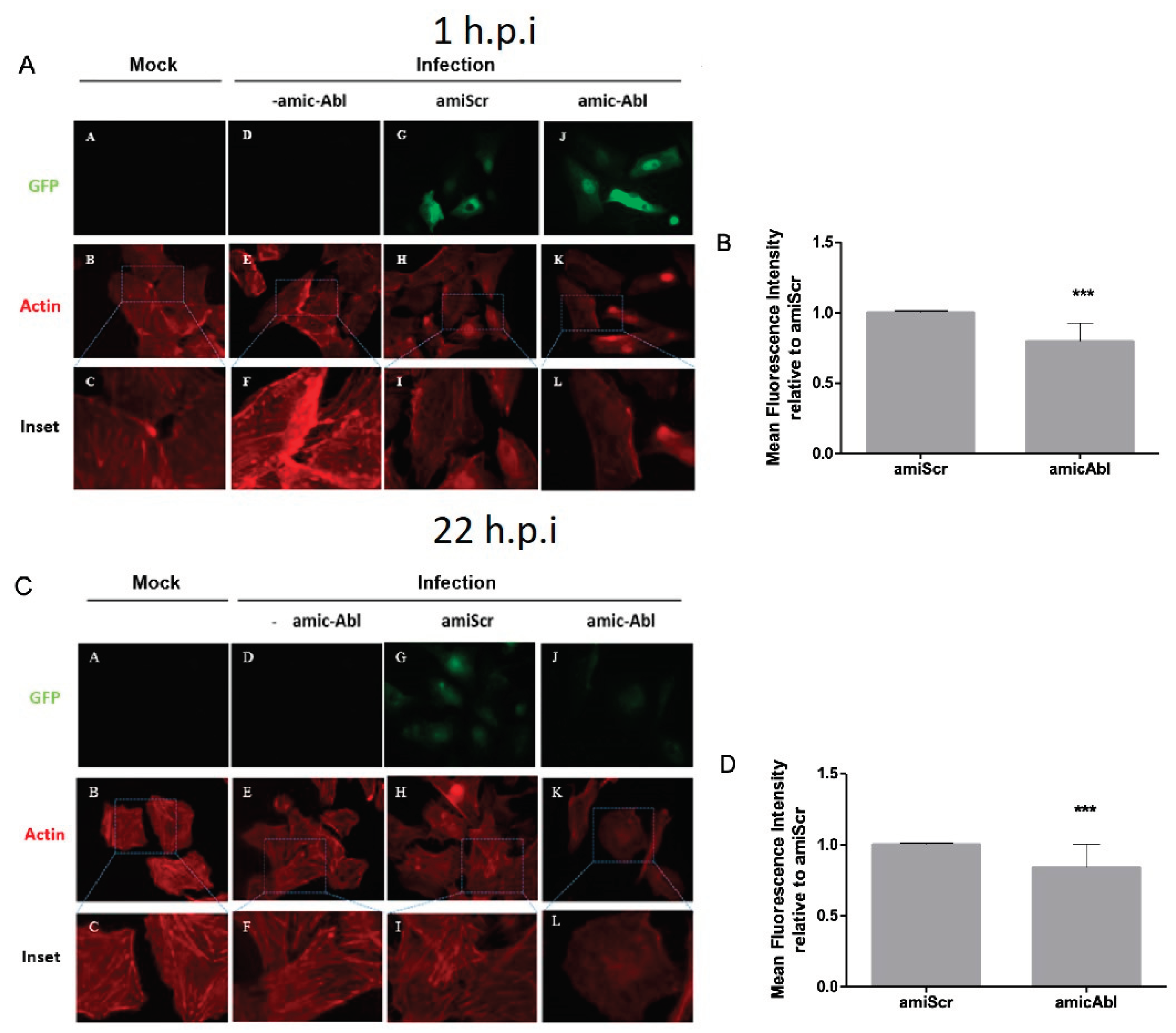

4.3. c-Abl Knockdown Produces Actin Reorganization on Late Events after DENV-2 Infection

Previous studies have shown that DENV-2 infection remodels actin filaments [

32,

56,

60,

61] and due to the role of c-Abl in actin remodeling [

62,

63,

64,

65],we further analyzed the role of c-Abl in the state of F-actin during DENV-2 infection. When Vero cells were infected with DENV-2, we observed a reduction of actin filaments in miABL1-transfected cells compared to miScrambled-transfected cells. During DENV-2 entry (1 h.p.i), we observed an increase in actin filaments at the cell membrane in miScrambled cells, which decreased during

ABL1 silencing (

Figure 4A). Similarly, at late stages of DENV-2 infection (22 h.p.i) we observed well-defined actin filaments in miScrambled cells, which decreased during

ABL1 silencing and displayed a round-shaped phenotype (

Figure 4C,D). Interestingly, the lack of defined actin filaments and the round-shaped phenotype has been previously observed in c-Abl knock out cells [

65].These results suggest that c-Abl is required for actin remodeling during DENV-2 infection.

5. Discussion

The worldwide priority of Dengue infection is summarized in two main aspects: i) the progressive increase of reported cases annually and ii) lack of an effective treatment to control the infection. While the strategies used for years to combat and eradicate dengue have not been successful, new alternatives on antiviral research to develop treatment have focused on host-targeted antivirals (HTA).

Among these, a great interest has focused in the study of the interactions between viruses and cellular proteins that participate in signaling pathways.

The modular structure of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase c-Abl, denoted by its different domains and sequences, explains the diversity of functions in which this kinase is involved either at the nucleus or cytoplasm [

34,

35,

36,

66]. Precisely, the binding domains to G and F-actin located at its c-terminal, explains its importance in events of cytoskeletal reorganization, such as the formation of actin fibers, lamellipodia, filopodia, cell adhesion and migration [

34,

62,

63,

64,

67,

68,

69,

70].

Interestingly, increasing evidence shows how the role of c-Abl in actin remodeling is required for the replication of different pathogens, including viruses [

44,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Previous studies have shown that DENV-2 infection remodels actin filaments [

31,

32,

56] and while c-Abl participates in actin remodeling [

34], its role over the state of F-actin during DENV-2 infection is yet to be determined. Here, we show evidence of the role of c-Abl in DENV-2 infection and actin remodeling. We observed a reduction in DENV-2 release under pharmacological inhibition of c-Abl or during

ABL1 knockdown. Moreover, we observed a reduction of F-actin filaments during ABL1 knockdown, suggesting that c-Abl might participate in DENV-2 infection through its role in actin remodelling.

Previously, the screen of different kinase inhibitors during DENV infection, showed that imatinib acts in pre-infection steps, showing 50% of reduction in the number of fluorescently stained DENV-infected cells and a five-fold decrease in viral titer [

71]. In a different study, imatinib showed inhibition of DENV-2 preferentially at post-entry events [

51]. To confirm the results observed by imatinib inhibition, we analyzed DENV-2 entry and post-entry events during

ABL1 silencing. We observed a significant accumulation of DENV-2 envelope protein at a late stage of infection and under

ABL1 silencing, suggesting that c-Abl participates in DENV-2 release. Interestingly, Clark y cols., showed that c-Abl participates in DENV-2 NGC replication cycle using both c-Abl knockdown in Huh7 cells and c-Abl knockout in fibroblast murine cells [

51]. Recently, results of our group showed the participation of c-Abl in DENV-induced endothelial dysfunction and during early steps of DENV infection, as well as actin cytoskeleton reorganization [

33]. Together, our results suggest that c-Abl plays a crucial role in DENV-2 infection.

Previous studies have shown that DENV-2 requires actin remodeling during the replication cycle [

32,

56,

57,

61,

72,

73,

74]. As it is well documented that c-Abl plays a role in actin dynamics, we hypothesized that c-Abl participates in DENV-2 infection through its function on actin remodeling. Our findings showed a decrease of actin filaments and a round-shaped morphology in

ABL1 silenced and DENV-2 infected epithelial cells, which has been previously observed in cells with impaired c-Abl kinase [

65].

A increasing set of evidence shows the requirement of filopodia and lamellipodia structures for viral entry and budding from infected cells [

75,

76,

77,

78].This specialized structure of actin facilitates virus spreading from cell-to-cell, and can minimize the appearance of virions in the extracellular space, which avoids recognition by the host immune response [

76].

The results presented here shed light on how actin remodeling plays a critical role in DENV-2 infection, through a mechanism involving c-Abl kinase activity. Moreover, elucidating cellular mechanisms involved in DENV-2 infection open new avenues for the treatment of Dengue based on cell-targets as an alternative therapeutic strategy.

6. Conclusions

Growing evidence supports research aimed at blocking cellular proteins used by intracellular pathogens to promote their infection processes. In the case of viral infections, the genetic variability and high mutation rates of genomes, mainly in viruses with RNA genome, make it difficult to identify therapeutic targets directed against viral proteins, which has favored the evaluation of HTA in viral infections. Robust evidence supports the participation of the actin cytoskeleton in several stages of DENV infection. Specifically, in the organization of actin to facilitate viral entry, replication, and release. In this study, we showed the involvement of the protein c-Abl kinase in the context of DENV infection by using silencing or pharmacological inhibition. We observed accumulation of dengue ENV protein and actin remodeling at late stages of infection. The use of kinase inhibitors has promising results

in vitro [

51]. Our results support the growing evidence of the participation of the kinase c-Abl in various steps of the DENV replication cycle, as well as its role in actin remodeling, a key aspect of DENV infection. These results inform about cellular mechanisms that could serve as potential therapeutic alternatives for Dengue management.

Author Contributions

GPCF performed the cellular, molecular, virological experiments, statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JCGG conceived the study, carried out funding acquisition and critically reviewed/corrected this manuscript. RLB designed and cloned the miABL1 and miScrambled constructs, experimentally validated miABL1 gene silencing activity, and contributed to editing the manuscript. MV-M, manuscript writing and correction. AMCL critically reviewed/corrected and wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Colombian Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Minciencias) grant 111584466951, and CODI-UdeA 2020-34137. M.V-M. is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [grant PID2020-116232RB-I00] and ECRIN-M3 from AECC/AIRC/CRUK. RLB is funded by NIHI NHLBI R01 HL148796.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kularatne SA, Dalugama C. Dengue infection: Global importance, immunopathology and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2022, 22, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO PAHO. As dengue cases increase globally, vector control, community engagement key to prevent spread of the disease 2023 [. 2023.

- Malavige GN, Fernando S, Fernando DJ, Seneviratne SL. Dengue viral infections. Postgrad Med J. 2004, 80, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Mosquito Program 2023 [.

- Lorenz C, Chiaravalloti-Neto F. Control methods for Aedes aegypti: Have we lost the battle? Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022, 49, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen LH, Marti C, Diaz Perez C, Jackson BM, Simon AM, Lu M. Epidemiology and burden of dengue fever in the United States: a systematic review. J Travel Med. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar]

- López MS, Gómez AA, Müller GV, Walker E, Robert MA, Estallo EL. Relationship between Climate Variables and Dengue Incidence in Argentina. Environ Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 57008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman MG, Gubler DJ, Izquierdo A, Martinez E, Halstead SB. Dengue infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, 16055.

- Messina JP, Brady OJ, Golding N, Kraemer MUG, Wint GRW, Ray SE, et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemer D, Frickmann H, Krüger A. [Dengue fever : Symptoms, epidemiology, entomology, pathogen diagnosis and prevention]. Hautarzt. 2017, 68, 1011–1020.

- Harapan H, Michie A, Sasmono RT, Imrie A. Dengue: A Minireview. Viruses. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tully D, Griffiths CL. Dengvaxia: the world's first vaccine for prevention of secondary dengue. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 9, 25151355211015839. [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Tsai YT, Wang SF, Wang WH, Chen YH. Dengue vaccine: an update. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021, 19, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aguilar ED, Martínez-Barnetche J, Rodríguez MH. Three highly variable genome regions of the four dengue virus serotypes can accurately recapitulate the CDS phylogeny. MethodsX. 2022, 9, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aguilar ED, Martínez-Barnetche J, Juárez-Palma L, Alvarado-Delgado A, González-Bonilla CR, Rodríguez MH. Genetic diversity and spatiotemporal dynamics of DENV-1 and DENV-2 infections during the 2012-2013 outbreak in Mexico. Virology. 2022, 573, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles TS, da Encarnação Sá-Guimarães T, de Alvarenga ESL, Guimarães-Ribeiro V, de Meneses MDF, de Castro-Salles PF, et al. History, epidemiology and diagnostics of dengue in the American and Brazilian contexts: a review. Parasit Vectors. 2018, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racherla RG, Pamireddy ML, Mohan A, Mudhigeti N, Mahalakshmi PA, Nallapireddy U, et al. Co-circulation of four dengue serotypes at South Eastern Andhra Pradesh, India: A prospective study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2018, 36, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina JP, Brady OJ, Scott TW, Zou C, Pigott DM, Duda KA, et al. Global spread of dengue virus types: mapping the 70 year history. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usme-Ciro JA, Mendez JA, Tenorio A, Rey GJ, Domingo C, Gallego-Gomez JC. Simultaneous circulation of genotypes I and III of dengue virus 3 in Colombia. Virol J. 2008, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño MF, Jiménez-Silva CL, Rey-Caro LA, Conde-Ocazionez SA, Flechas-Alarcón MC, Velandia SA, et al. Dengue in Santander State, Colombia: fluctuations in the prevalence of virus serotypes are linked to dengue incidence and genetic diversity of the circulating viruses. Trop Med Int Health. 2019, 24, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan MN, Garcia-Blanco MA. Targeting host factors to treat West Nile and dengue viral infections. Viruses. 2014, 6, 683–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand YM, Roa-Linares V, Santiago-Dugarte C, Del Olmo E, López-Pérez JL, Betancur-Galvis L, et al. A new host-targeted antiviral cyclolignan (SAU-22.107) for Dengue Virus infection in cell cultures. Potential action mechanisms based on cell imaging. Virus Res. 2023, 323, 198995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani A, Basimi P, Agi E, Bolhassani A. Pharmaceutical Approaches for Treatment of Hepatitis C virus. Curr Pharm Des. 2020, 26, 4304–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek YB, Kwon HJ, Sharif M, Lim J, Lee IC, Ryu YB, et al. Therapeutic strategy targeting host lipolysis limits infection by SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salasc F, Lahlali T, Laurent E, Rosa-Calatrava M, Pizzorno A. Treatments for COVID-19: Lessons from 2020 and new therapeutic options. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik RR, Shakya AK, Aladwan SM, El-Tanani M. Kinase Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Agents in the Treatment of COVID-19. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee MF, Wu YS, Poh CL. Molecular Mechanisms of Antiviral Agents against Dengue Virus. Viruses. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Troost B, Smit JM. Recent advances in antiviral drug development towards dengue virus. Curr Opin Virol. 2020, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu S, Schor S, Karim M, Saul S, Robinson M, Kumar S, et al. BIKE regulates dengue virus infection and is a cellular target for broad-spectrum antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2020, 184, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-Linares VC, Escudero-Flórez M, Vicente-Manzanares M, Gallego-Gómez JC. Host Cell Targets for Unconventional Antivirals against RNA Viruses. Viruses. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Cuartas-López AM, Gallego-Gómez JC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3ß participates in late stages of Dengue virus-2 infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2020, 115, e190357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas-López AM, Hernández-Cuellar CE, Gallego-Gómez JC. Disentangling the role of PI3K/Akt, Rho GTPase and the actin cytoskeleton on dengue virus infection. Virus Res. 2018, 256, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero-Flórez M, Torres-Hoyos D, Miranda-Brand Y, Gallego-Gómez JC, Vicente-Manzanares M. Dengue Virus Infection Alters Inter-Endothelial Junctions and Promotes Endothelial-Mesenchymal-Transition-Like Changes in Human Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Viruses. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Colicelli, J. ABL tyrosine kinases: evolution of function, regulation, and specificity. Sci Signal. 2010, 3, re6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantschel O, Superti-Furga G. Regulation of the c-Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, JY. The capable ABL: what is its biological function? Mol Cell Biol. 2014, 34, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Cui Y, Bai Y, Fang Y, Gao T, Wang G, et al. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl potentiates interferon-mediated antiviral immunity by STAT1 phosphorylation. iScience. 2021, 24, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Lei X, Wang D, Jiang Y, Zhan Y, Li M, et al. Inhibition of Abl or Src tyrosine kinase decreased porcine circovirus type 2 production in PK15 cells. Res Vet Sci. 2019, 124, 1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobelt R, Adler J, Paran N, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Melamed S, Politi B, et al. Imatinib inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection by an off-target-mechanism. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basant A, Way M. The amount of Nck rather than N-WASP correlates with the rate of actin-based motility of Vaccinia virus. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11, e0152923. [Google Scholar]

- Wessler S, Backert S. Abl family of tyrosine kinases and microbial pathogenesis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011, 286, 271–300. [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmeyer N, Harrer A, Rottner K, Backert S. CagA Induces Cortactin Y-470 Phosphorylation-Dependent Gastric Epithelial Cell Scattering via Abl, Vav2 and Rac1 Activation. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Feller SM, Wessler S. Emerging roles of Abl family tyrosine kinases in microbial pathogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008, 33, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome TP, Weisswange I, Frischknecht F, Way M. Abl collaborates with Src family kinases to stimulate actin-based motility of vaccinia virus. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves PM, Bommarius B, Lebeis S, McNulty S, Christensen J, Swimm A, et al. Disabling poxvirus pathogenesis by inhibition of Abl-family tyrosine kinases. Nat Med. 2005, 11, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swimm AI, Bornmann W, Jiang M, Imperiale MJ, Lukacher AE, Kalman D. Abl family tyrosine kinases regulate sialylated ganglioside receptors for polyomavirus. J Virol. 2010, 84, 4243–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne CB, Bergelson JM. Virus-induced Abl and Fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell. 2006, 124, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi S, Takeuchi K, Chihara K, Sun X, Honjoh C, Yoshiki H, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Particle Assembly Involves Phosphorylation of NS5A by the c-Abl Tyrosine Kinase. J Biol Chem. 2015, 290, 21857–21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García M, Cooper A, Shi W, Bornmann W, Carrion R, Kalman D, et al. Productive replication of Ebola virus is regulated by the c-Abl1 tyrosine kinase. Sci Transl Med. 2012, 4, 123ra24. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon B, Campbell N, Ratner L. Role of Abl kinase and the Wave2 signaling complex in HIV-1 entry at a post-hemifusion step. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000956. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Miduturu C, Schmidt AG, Zhu X, Pitts JD, Wang J, et al. GNF-2 Inhibits Dengue Virus by Targeting Abl Kinases and the Viral E Protein. Cell Chem Biol. 2016, 23, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen W, Gao N, Wang JL, Tian YP, Chen ZT, An J. Vimentin is required for dengue virus serotype 2 infection but microtubules are not necessary for this process. Arch Virol. 2008, 153, 1777–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlaya R, Pattanakitsakul SN, Sinchaikul S, Chen ST, Thongboonkerd V. Vimentin interacts with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins and dengue nonstructural protein 1 and is important for viral replication and release. Mol Biosyst. 2010, 6, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei S, Tian YP, Xiao WD, Li S, Rao XC, Zhang JL, et al. ROCK is involved in vimentin phosphorylation and rearrangement induced by dengue virus. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013, 67, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava N, Sripada S, Kaur J, Shah PS, Cecilia D. Insights into the internalization and retrograde trafficking of Dengue 2 virus in BHK-21 cells. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e25229. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Zhang JL, Chen W, Xu XF, Gao N, Fan DY, et al. Roles of small GTPase Rac1 in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton during dengue virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio-Meza H, Castillo-Alvarez A, González-Bonilla C, Meza I. Cross-talk between Rac1 and Cdc42 GTPases regulates formation of filopodia required for dengue virus type-2 entry into HMEC-1 cells. J Gen Virol. 2009, 90 Pt 12, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau RL, Martins I, Davidson BL. Artificial microRNAs as siRNA shuttles: improved safety as compared to shRNAs in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009, 17, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau RL, Monteys AM, Davidson BL. Minimizing variables among hairpin-based RNAi vectors reveals the potency of shRNAs. RNA. 2008, 14, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wu N, Gao N, Yan W, Sheng Z, Fan D, et al. Small G Rac1 is involved in replication cycle of dengue serotype 2 virus in EAhy926 cells via the regulation of actin cytoskeleton. Sci China Life Sci. 2016, 59, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Gao W, Li J, Wu W, Jiu Y. The Role of Host Cytoskeleton in Flavivirus Infection. Virol Sin. 2019, 34, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton EA, Oliver TN, Pendergast AM. Abl kinases regulate actin comet tail elongation via an N-WASP-dependent pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 8834–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart JR, Gonzalez FH, Kawai H, Yuan ZM. c-Abl interacts with the WAVE2 signaling complex to induce membrane ruffling and cell spreading. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281, 31290–31297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring PJ, Meisenhelder J, Johnson SA, Zhou GL, Field J, Shah K, et al. c-Abl phosphorylates Dok1 to promote filopodia during cell spreading. J Cell Biol. 2004, 165, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring PJ, Hunter T, Wang JY. Regulation of F-actin-dependent processes by the Abl family of tyrosine kinases. J Cell Sci. 2003, 116 Pt 13, 2613–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Etten, RA. Cycling, stressed-out and nervous: cellular functions of c-Abl. Trends Cell Biol. 1999, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández SE, Krishnaswami M, Miller AL, Koleske AJ. How do Abl family kinases regulate cell shape and movement? Trends Cell Biol. 2004, 14, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley WD, Koleske AJ. Regulation of cell migration and morphogenesis by Abl-family kinases: emerging mechanisms and physiological contexts. J Cell Sci. 2009, 122 Pt 19, 3441–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng Y, Zhang J, Badour K, Arpaia E, Freeman S, Cheung P, et al. Abelson-interactor-1 promotes WAVE2 membrane translocation and Abelson-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation required for WAVE2 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Etten RA, Jackson PK, Baltimore D, Sanders MC, Matsudaira PT, Janmey PA. The COOH terminus of the c-Abl tyrosine kinase contains distinct F- and G-actin binding domains with bundling activity. J Cell Biol. 1994, 124, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Chu JJ, Yang PL. c-Src protein kinase inhibitors block assembly and maturation of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104, 3520–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitoboam K, Phaonakrop N, Libsittikul S, Thepparit C, Roytrakul S, Smith DR. Actin Interacts with Dengue Virus 2 and 4 Envelope Proteins. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0151951. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zou L, Hu Z, Chen W, Zhang J, Zhu J, et al. Identification and characterization of a 43 kDa actin protein involved in the DENV-2 binding and infection of ECV304 cells. Microbes Infect. 2013, 15, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E O-G, A T-C, JC G-G. Cell Biology of Virus Infection. The Role of Cytoskeletal Dynamics Integrity in the Effectiveness of Dengue Virus Infection. In: Intech, editor. Cell Biology - New Insights2016.

- Carpenter JE, Hutchinson JA, Jackson W, Grose C. Egress of light particles among filopodia on the surface of Varicella-Zoster virus-infected cells. J Virol. 2008, 82, 2821–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang K, Baginski J, Hassan SF, Volin M, Shukla D, Tiwari V. Filopodia and Viruses: An Analysis of Membrane Processes in Entry Mechanisms. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 300. [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnikova L, Bohil AB, Cheney RE, Becker S. Budding of Marburgvirus is associated with filopodia. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudt G, Kolesnikova L, Dolnik O, Sodeik B, Becker S. Live-cell imaging of Marburg virus-infected cells uncovers actin-dependent transport of nucleocapsids over long distances. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110, 14402–14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).