Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV) infection has emerged as an urgent global health threat, with its incidence escalating at an alarming rate and its geographic footprint expanding steadily. Once confined largely to tropical regions, this infection now threatens populations across more than 125 countries[

1,

2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports an eightfold increase in annual DENV cases over the past two decades, estimating

100-400 million infections each year and placing about half of the world’s population at risk[

3]. Multiple converging factors are suggested to drive this surge. These include rapid urbanization and global population growth that have created dense human-mosquito contact zones. At the same time, increased international travel and trade have helped ferry

Aedes mosquito vectors and DENV across borders[

4]. Moreover, warmer climate changes characterized by altered rainfall and humidity are extending the habitat range of

Aedes aegypti and

Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, opening the door for DENV transmission in previously unaffected areas, including parts of the United States, Canada, and Europe[

4,

5]. The result is a burgeoning global DENV infection burden that can potentially strain public health systems and require new strategies to curb its spread. Yet, no specific antiviral therapy or broadly effective vaccine exists to counter DENV[

6], making it imperative to deepen our understanding of Dengue pathogenesis as a foundation for novel interventions.

Dengue’s clinical spectrum ranges from mild to life-threatening hemorrhagic fever[

7], largely shaped by the complex interplay between the virus and the host immune system. A hallmark of DENV pathogenesis is its proclivity to infect and replicate within immune cells that would ordinarily coordinate antiviral defenses. Monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and even B and T lymphocytes are all targets for DENV[

6,

8]. By seeding itself in these cells, DENV actively subverts immune responses: the infection of DCs and monocyte-lineage cells impairs their antigen presentation and cytokine production,

dysregulating antiviral functions and facilitating viral dissemination[9,10]. In essence, the virus turns the body’s defenders into Trojan horses. Concurrently, DENV has evolved mechanisms to

evade innate immune detection and antiviral signaling. Its nonstructural proteins (like NS2A, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) blunt the type-I interferon response, a key early antiviral defense[

11,

12], by targeting critical signaling molecules. For example, DENV can prevent phosphorylation of STAT1 (via NS2A/NS4A/NS4B) and even induce degradation of STAT2 (via NS5)[

13,

14,

15], thereby

antagonizing interferon pathways and allowing the virus to replicate unabated in host cells. This immune evasion is further compounded in secondary infections by antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE)[

16], wherein non-neutralizing antibodies from a prior DENV exposure facilitate increased infection of Fc-receptor-bearing cells, often exacerbating disease severity. Together, the ability of DENV to cripple innate antiviral signaling and exploit the host’s immune cells underlies the uncontrolled viral replication and hyperinflammatory cascades seen in severe Dengue cases.

Amid these virus-host dynamics, an intriguing role has emerged for extracellular vesicles, particularly

exosomes, in DENV pathogenesis[

17,

18,

19]. Exosomes are nanoscale vesicles released by cells, capable of ferrying proteins, RNA, and other biomolecules between cells. During DENV infection, mosquito vectors and human host cells secrete exosomes laden with viral material. Remarkably, exosomes from DENV-infected cells have been found to contain the

full-length viral genome and viral proteins[

20], rendering them infectious to new target cells. These virus-packed exosomes can shuttle DENV between cells covertly, effectively forming a

hidden transmission route that shields the virus from neutralizing antibodies and immune surveillance[

21]. By altering the cargo and even the size of exosomes (DENV-induced exosomes tend to be larger, presumably to accommodate the entire genome), the virus ensures its successful transfer and persistence in the host. The

immunomodulatory effects of these vesicles are also under intense scrutiny: exosomal cargo from DENV-infected cells (such as specific microRNAs, cytokines, and even soluble NS1 protein) can modulate recipient cells’ immune responses[

22], skewing them in ways that may promote virus survival or contribute to vascular leak and other pathogenic outcomes[

22,

23].

Considering DENV’s reliance on host cell machinery for both replication and stealth, host factors that mediate these processes have attracted growing interest. One such factor is

Reticulon 3 (RTN3), an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated protein that has recently been implicated in the life cycles of several flaviviruses[

24]. RTN3 belongs to a family of ER membrane-shaping proteins and is widely expressed in human tissues. Intriguingly, RTN3 appears to be hijacked by flaviviruses to facilitate the formation of viral replication organelles[

24]. A recent study demonstrated that RTN3 (specifically the RTN3.1A isoform) is required for efficient replication of West Nile virus, Zika virus, and

DENV, likely through a direct or indirect interaction with the viral NS4A protein[

24]. NS4A is a DENV nonstructural protein known to remodel ER membranes and create vesicle packets where viral RNA replication occurs[

24,

25]. RTN3, as an ER membrane protein, may serve as a cofactor for NS4A’s membrane-bending activities[

25]. Consistently, the absence of RTN3 was shown to trigger the degradation of viral NS4A and

disrupt the assembly of DENV replication complexes, resulting in impaired production of new viral particles. Beyond supporting replication, RTN3 has also been linked to the

exosome-mediated phase of viral infection. Our recent studies with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) - another positive-strand RNA virus in the Flavivirus family - revealed that RTN3 is upregulated during infection and is incorporated into exosomes carrying infectious viral RNA[

26]. Knocking down RTN3 in HCV-infected cells significantly reduced the release of infectious virus-containing exosomes, whereas RTN3 overexpression enhanced it. These findings led us to conclude that RTN3

acts as a key regulator of viral exosome loading and release, effectively helping to smuggle viral genomes out of the cell under the radar of the immune system[

26]. By analogy, in the context of Dengue, RTN3 might play a dual role: (i) assisting DENV replication by stabilizing critical viral proteins and remodeling membranes, and (ii) facilitating the packaging of DENV RNA into exosomal vesicles for cell-to-cell transmission. This emerging picture places RTN3 at the intersection of two central facets of the DENV life cycle - intracellular replication and intercellular spread - making it a particularly compelling subject for further research.

In all, existing evidence indicates that RTN3 plays a critical role in DENV pathogenesis; however, its precise function in the generation and/ or loading of infectious exosomes remains unresearched. To date, no study has definitively shown whether or how RTN3 contributes to the assembly of these infectious DENV exosomes, revealing a pressing gap in our understanding. Our current research seeks to clarify if and how RTN3 might influence or modulate infectious exosome generation, potentially unveiling new antiviral strategies.

Materials and Methods

Huh7 Cell Culture, Infection, and Co-Culture Experiments

Huh7 hepatoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; ThermoFisher Scientific, Cleveland, OH, USA) supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS. For infection, 2.5 × 105 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and infected with DENV-2 (DENV-2, New Guinea C strain, ATCC VR-1584) at MOI 0.1. After 1 hour of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, unbound virions were removed, and cells were maintained for 72 hours (h). Supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes to remove cell debris. These were used for downstream plaque assay and exosome isolation. Cells were harvested for RNA and protein extraction. For co-culture experiments, 2.5 × 105 Huh7 cells were seeded and treated with titrated infectious exosomes at MOI 0.1, incubated for 72h, and used for downstream RNA, protein extraction, Western blotting, and qPCR analyses.

THP-1 Cell Culture, Infection, and Flow Cytometry Analysis

The THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cell line was cultured in RPMI1640 medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cleveland, OH, USA) supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), and 0.5 nM 2-mercaptoethanol. For infection experiments, 1 × 106 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and infected with DENV-2 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Cells were incubated for 24-, 48-, and 72-hours post-infection. Supernatants were harvested and clarified by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 minutes to remove debris, followed by storage at -80°C for exosome extraction and NanoFCM analysis, or at -150°C for viral titration. Cells were harvested for downstream RNA and protein extraction. Flow cytometry was performed to assess viability and infection efficiency. Cells were stained with Fixable Viability Stain 7-AAD (BD Biosciences Cat# 555815) and antibodies against CD14 (BD Horizon Cat # 563419), CD16 (Biolegend Cat # 302012), and intracellular NS3 (GeneTex Cat # GTX124252). Flowcytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software v10.7.1.

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Conditioned media from THP-1 and Huh7 cultures were centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes, followed by a second centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cell debris. Supernatants were processed using immunomagnetic positive selection with the EasySep Human Pan-Extracellular Vesicle Positive Selection Kit (Stemcell Technologies, Catalog #18000), which isolates exosomes based on surface markers. First, extracellular vesicles (EVs) were isolated using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) with a 2 mL EV SEC Column (Stemcell Technologies, Catalog #100-0415), collecting 500μL fractions. Fractions were analyzed via NanoFCM (nFCM Inc., China), and protein concentration was assessed by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Exosome-rich fractions (typically fraction 13) were resuspended in 100μL PBS with 0.2% Bovine Serum Albumin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for storage. Exosome samples were RNase-treated to eliminate free viral RNA. Exosomes were used for infectivity titration, Western blotting, and protein profiling.

Plaque Assay

Viral titers of infectious exosomes were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates. Monolayers were infected with 10-fold serial dilutions of exosome preparations in 0.2 mL volumes, adsorbed for 1 hour at 37 °C with gentle rocking every 15 minutes. A 1 mL overlay of MEM-CMC was applied, and cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5 days. Plates were fixed with 10% formaldehyde, stained with crystal violet, and plaques counted to calculate PFU/mL.

Exosome Protein Extraction and Cargo Profiling

Exosomes (200-300 µL) were lysed in cytoplasmic extraction buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Samples were incubated on ice for 15 minutes using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail REF. # 11836153001) and incubated an additional 30 minutes on ice. Lysates were vortexed, incubated further on ice, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants containing extracted proteins were collected for analysis.

Western Blotting

Proteins extracted from cells and exosomes were quantified by BCA assay, resolved by SDS-PAGE using 8% or 12% gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes. RTN3 long and short isoforms were detected using ProteinTech 12055-2-AP and BETHYL A302-860A as well as NS3(GeneTex GTX124252). Exosomal markers CD63 (Santacruz Cat. # Sc-365604) and HSP70 (Abcam Cat. # Ab181606) confirmed EV identity; calnexin (Abcam Cat. # Ab181606) was used to exclude ER contamination.

CRISPR/Cas9 Knockdown and Lentiviral Transduction

RTN3S-specific gRNAs were cloned into the LentiCRISPRv2 vector (Addgene #52961, Feng Zhang). HEK293T cells were co-transfected with psPAX2, pMD2.G, and LentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA plasmids. Viral supernatants were collected, filtered (0.45μm), and stored at -80 °C. For titration, HeLa cells were infected with serial dilutions and selected with puromycin (1 µg/mL). Surviving colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. Huh7 cells were transduced with lentivirus at MOI 5-10 in the presence of 8μg/mL polybrene. Supernatants were centrifuged, and exosomes were quantified by NanoFCM.

Overexpression Plasmid Transfection

Huh7 cells were transfected using FUGENE 4K (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) with plasmids encoding RTN3S full-length or truncation mutants (ΔN11, ΔN45, ΔC36) in the Flag-CMV-2 backbone (gift from Prof. Mitsuo Tagaya). Transfection was followed by infection with DENV. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove debris. Total particle and exosome counts were assessed by NanoFCM.

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) and Co-Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Infected Huh7 cells samples were fixed at room temperature with 4% formaldehyde buffered saline for 10 minutes to initiate covalent crosslinking of RNA-protein complexes. Crosslinking was quenched by adding 1/10 volume of 1.25 M glycine (MULTICELL Cat. # 800-045-eg) to reach a final concentration of 125 mM, followed by incubation at room temperature for 5 minutes. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped into cold PBS, transferred to tubes, and pelleted by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. All subsequent steps were performed on ice or at 4 °C to preserve RNA–protein interactions. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500µl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (0.060 g), 150 mM NaCl (0.088 g), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (0.050 g), 0.1% SDS (0.010 g), 1% NP-40 (v/v; 100 µL), 1 mM EDTA (0.0037 g) with 1x protease and RNase inhibitor cocktail. Total cellular proteins were pre-cleared with protein G beads. 100μg of total protein was incubated with anti-dsRNA (GenScript Cat. # A02181-40) and RTN3 (ProteinchTech Cat. #12055-2-AP) antibodies. Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4˚C using 1 in 100 dilution of primary antibody and normal rabbit/mouse IgG (Santa Cruz cat #sc-3877 and sc-69786) non-specific antibody serving as IP control. A mixture of Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (Santa Cruz cat. #sc-2003) was added, and the incubation was continued for an additional 60 minutes. The samples were washed with SDS ChIP lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor and RNase inhibitor. The immunoprecipitants (protein-RNA complexes) were either used for Western blot analysis or RNA purification using the RNeasy kit.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assay for DENV Genomic RNA and Host Gene Transcripts

Cell pellets and purified exosome fractions were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and total RNA was recovered using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, cat. # 74004) according to the supplier’s instructions. One microgram of RNA from each sample was converted to cDNA with the iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The resulting cDNA served as a template for SYBR Green-based quantitative PCR (qPCR) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 instrument. Primer pairs and cycling parameters were identical to those reported previously[

26], and the full primer list is provided in

Table 1. The assay simultaneously quantified DENV genomic RNA and the mRNA levels of selected host genes of interest. Relative expression was calculated with the 2^−ΔΔCt method, normalizing each target to 18S rRNA as an internal control, as outlined in earlier studies[

26].

Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis

We retrieved publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing (ScRNA-seq) data from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy individuals (C), Dengue patients (D), Dengue warning signs (DWS), and severe Dengue patients (SD). These datasets were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which is owned and operated by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), a part of the National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States. The GEO database is a public archive and resource for gene expression data. Specifically, we used datasets with accession code GSM6833297. A total of 4 healthy controls, 8 Dengue, 4 DWS, and 8 SD patients were included. Analyses were performed using Seurat (v5.1.0). Cells expressing 200-5,000 genes, <40,000 counts, and <5% mitochondrial transcripts were retained (n = 154,220). Data was normalized (LogNormalize), top 2,000 variable genes identified, and PCA was applied (top 20 PCs). UMAP and clustering (resolution = 0.4) followed. Cell types were annotated using SingleR and the Human Primary Cell Atlas. For monocyte re-clustering (n = 27,169), standard preprocessing was repeated. Differential gene expression between groups was determined using the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.05, avg_logFC threshold applied).

Data Availability

Upon acceptance and publication of this manuscript, all relevant data files generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3 will be made publicly available. The data will be accessible through a dedicated FigShare repository and on GitHub. Detailed access information, including repository links, will be provided at the time of publication.

Ethics Statement

In this research, we performed a secondary analysis using a publicly available dataset. Therefore, the institutional review board (IRB) and ethical approval were not required, as the participant data had already been anonymized and made publicly accessible. Consequently, there were no additional ethical concerns regarding participant confidentiality or consent for this study.

Discussion

Exosomes are increasingly recognized as critical mediators of viral pathogenesis, functioning as non-canonical vehicles for the cell-to-cell spread of RNA viruses. In hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, for example, serum-derived exosomes were shown to carry replication-competent HCV RNA and assemble a complex of viral RNA with host factors (Ago2, miR-122, HSP90) that could infect naïve hepatocytes in a receptor-independent manner[

27]. These findings underscore that exosomes can subvert classical entry pathways to disseminate infection. By analogy, recent works in flaviviruses (including Dengue virus [DENV]) and coronaviruses (SARS-CoV-2) have revealed that infected cells release EVs containing viral RNAs and proteins, which can promote transmission and modulate immunity. However, until now, the cellular mechanisms that drive the packaging of viral components into infectious exosomes have remained poorly defined. Here, we identify Reticulon-3 (RTN3), an ER-membrane curvature protein, as a key regulator of infectious exosome biogenesis in DENV infection, thereby filling a major gap in our understanding of how infectious vesicles are generated during RNA virus infection.

Our study shows that DENV infection robustly upregulates RTN3 (particularly the short isoform, RTN3S) in host cells and that RTN3 localizes to sites of viral replication and budding. We found that RTN3 co-immunoprecipitated with DENV non-structural protein 3 (NS3) and double-stranded viral RNA, suggesting a direct interaction with the viral replication complex (analogous to RTN3’s known binding of HCV RNA). Functionally, CRISPR-mediated RTN3 knockdown profoundly reduced the release of exosomes and almost abolished the export of DENV NS3 and viral RNA into extracellular vesicles. Conversely, overexpressing RTN3S strongly increased exosome secretion and the infectivity of DENV-containing exosomes. Using a series of RTN3S deletion mutants, we mapped the effect on the carboxy-terminal amphipathic helices of the protein: deletion of the C-terminal 36 amino acids abrogated the ability of RTN3 to enhance exosome release or to load infectious cargo, whereas N-terminal deletions had lesser effects. These gain- and loss-of-function studies definitively establish RTN3 as an ER-shaping factor whose membrane-bending activity is co-opted by DENV to bud vesicles containing viral genomes. Importantly, these findings mirror and extend prior work in HCV[

26]. showed that RTN3 KD decreased the number of infectious HCV-bearing exosomes while RTN3 overexpression increased them. Thus, RTN3 emerges as a novel selective cargo-sorting scaffold that directs viral RNA and proteins into secreted exosomes. In mechanistic terms, RTN3’s C-terminal helices likely induce membrane curvature and recruit the nascent viral RNP complex into intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies, coupling ER morphological remodeling to EV biogenesis. This mode of action is distinct from, yet complementary to, classical vesicle-sorting pathways[

28,

29,

30].

RTN3’s role can be compared with other known ER- or EV-related host factors. The double-stranded RNA-binding protein Staufen1 (STAU1) is a cytosolic regulator that has been shown to bind viral RNAs and promote HCV and influenza replication[

31]. Like RTN3, STAU1 can interact with viral genomic RNA and replication complexes, but STAU1 functions primarily in RNA transport and translational regulation, not membrane shaping. In DENV, STAU1 might theoretically help escort viral RNA, but it would not directly induce vesicle formation as RTN3 does. The ESCRT-III component CHMP2A has been reported to bind Dengue virus RNA and participate in the budding of virus particles and vesicles.[

32] However, CHMP2A’s role in EV formation is broad and not specific to RNA cargo selection[

33,

34]. In contrast, RTN3 appears to be an RNA-sensing factor that specifically enriches viral replication products into vesicles. Similarly, small GTPases like RAB7A regulate endosomal fate: normally, RAB7A drives late endosomes toward lysosomal degradation and thereby limits exosome secretion[

35,

36,

37]. By contrast, RTN3 overexpression effectively increases vesicle output even in the face of high RAB7A, indicating that RTN3 can override endolysosomal routing to favor secretion.

Another ER chaperone, HSPA5 (BiP/GRP78), is induced by DENV infection and is critical for the proper folding of viral proteins[

38]. HSPA5 was identified in recent high-throughput screens as a proviral factor in flaviviruses. We observed that DENV infection of monocytes upregulated HSPA5, along with other ER-stress markers, and these factors were prominent in exosome-associated protein networks. However, unlike HSPA5’s role as a general chaperone and stress sensor, RTN3 provides a structural scaffold. TMEM41B (an ER transmembrane protein important for lipid mobilization and autophagy) is another proviral host factor for DENV, as part of the replication membrane platform. Whereas TMEM41B facilitates membrane lipid flux, RTN3 specifically sculpts the curved ER membranes into vesicular buds[

39]. DNAJC3 (P58^IPK), an ER luminal co-chaperone involved in the unfolded protein response, is also implicated in viral infections, but its function is again chaperone-like rather than membrane-bending[

40]. In summary, RTN3 is unique among these factors: it is an ER-membrane remodeler that directly connects viral replication sites to the extracellular vesicle biogenesis pathway.

Our results also highlight how RTN3-driven EV production tangibly alters immune responses. In DENV-infected monocyte cultures, we observed not only a surge in exosome release but also a phenotypic shift in monocyte subsets. DENV infection induced expansion of CD16+ intermediate monocytes (CD14+CD16+), both in vitro and as reflected in human Dengue patient single-cell data. This population was identified previously in Dengue patients and is associated with stimulating plasmablast and antibody responses. Our flow-cytometry data showed an increased CD16 on THP-1 cells mostly at 48 hours of infection, and our scRNA-seq analysis revealed that patient monocytes in the Dengue cohort co-express FCGR3A (CD16) with RTN3. Transcriptionally, infected monocytes upregulated several exosome/ER-related genes: CHMP2A and RAB7A were induced, and HSPA5 remained elevated. These changes suggest a coordinated antiviral stress program: CHMP2A and RAB7A increases may reflect enhanced endomembrane turnover, while HSPA5 indicates ER stress from viral protein load. Concomitantly, infected monocytes exhibited elevated CXCL10 and IFN-β, consistent with an interferon-driven antiviral state. Thus, DENV not only hijacks RTN3 to make infectious exosomes, but the resulting vesicle traffic and ER remodeling feed back into immune activation pathways. It is plausible that infectious exosomes (laden with viral RNA/NS proteins) contribute to innate sensing in bystander cells, or conversely, could temper immune detection by cloaking viral RNA within host membranes.

These findings have significant implications for DENV pathogenesis and potential therapies. By packaging viral genomes into exosomes, DENV may amplify infection foci and subvert neutralizing antibodies, much as was seen with HCV. Targeting RTN3 or its interactors could therefore block a parallel transmission route. For example, we note that HSP90 inhibitors impaired exosome-mediated HCV spread[

26]; given RTN3 complexes with HSP90-bound RNA[

26], similar strategies might limit DENV EV infectivity. More broadly, viruses that exploit exosomes (including flaviviruses like Zika and even SARS-CoV-2) may share components of this pathway. Indeed, SARS-CoV-2-infected cells release exosomes containing viral RNA and proteins, potentially promoting spread while evading immune recognition. Our discovery of RTN3 as an EV regulator suggests new therapeutic angles: modulation of ER curvature proteins or inhibition of specific cargo-loading domains could attenuate exosome-mediated infection. Notably, RTN3 also influences autophagy and ER-phagy, hinting that autophagy-modulating drugs (e.g., V-ATPase inhibitors) might indirectly affect EV release as we observed in HCV models.

In conclusion, this work advances the field by revealing a direct mechanistic link between the ER membrane-shaping machinery and the genesis of infectious viral exosomes. By identifying RTN3 and its functional domains as critical for packaging DENV RNA into EVs, we address a long-standing knowledge gap in extracellular vesicle biology during viral infection. Our integrated analysis, from molecular virology to single-cell immunophenotyping, highlights how RTN3-driven vesicles reshape the host response and viral spread. These insights open new research directions, such as exploring RTN3 inhibitors or studying ER curvature proteins in other virus systems, intending to disrupt EV-mediated pathogenesis and enhance antiviral strategies.

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and T.N.B.; methodology, R.B. C.N.A. and T.N.B.; formal analysis, R.B., C.N.A., S.S., T.N., J.v.G., S.T.I., P.L., and T.N.B.; investigation, R.B., C.N.A. and B.T.N.; resources, T.N.B.; data curation, R.B. C.N.A. and B.T.N.; writing-original draft preparation, R.B. and T.N.B.; writing -review and editing, R.B., C.N.A., S.S.; T.N.; J.v.G., S.T.I., P.L., and T.N.B.; supervision, R.B. and T.N.B.; project administration, T.N.B; funding acquisition, T.N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

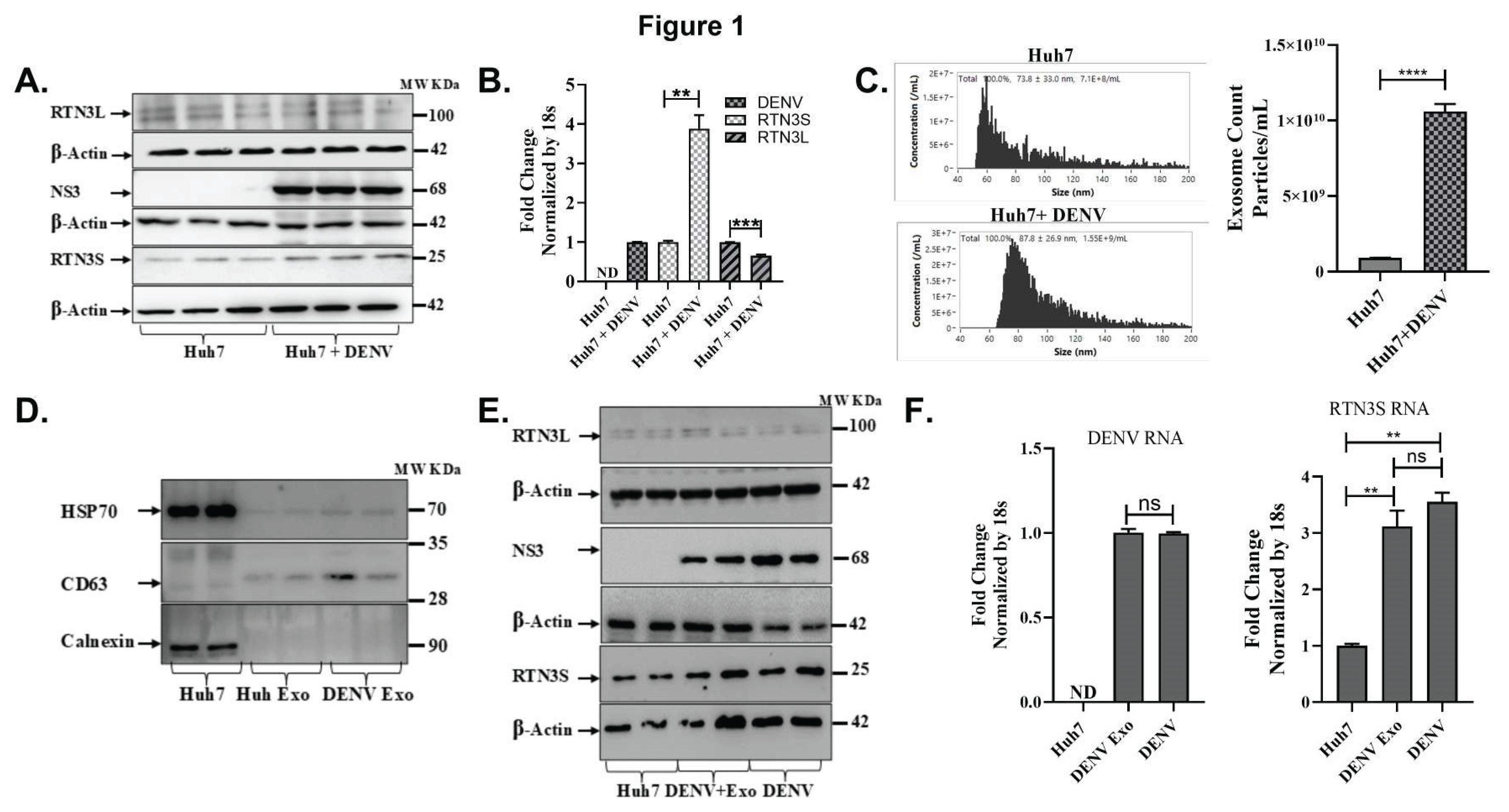

Figure 1.

Dengue virus infection upregulates RTN3 isoforms and promotes exosome release in Huh7 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Huh7 cell lysates without (Ctrl) or with Dengue virus (DENV) infection. Membranes were probed for RTN3 long (RTN3L, ~100 kDa) and short (RTN3S, ~25 kDa) isoforms, Dengue NS3 (~68 kDa), and β-Actin (~42 kDa) as a loading control. (B) RT-qPCR quantification of RTN3L and RTN3S mRNA in Huh7 cells ± DENV, normalized to 18S rRNA. The label ND denotes ‘not detected’. (C) NanoFlow Cytometry analysis (NanoFCM) of purified exosomes from Huh7 culture supernatants. Left: size-distribution histograms (30-150 nm) for exosomes from mock or DENV-infected cells. Right: bar graph of exosome concentration (particles/mL). (D) Western blots of whole-cell lysate (Huh7) and purified exosome fractions (Huh Exo, DENV Exo). Exosomal markers HSP70 and CD63 were assessed, whereas the ER protein Calnexin was probed to ascertain the purity of the exosome preparation. (E) Huh7 cells infected with DENV were either untreated or co-treated with purified DENV-derived exosomes (+Exo). Cell lysates were western blotted then probed for RTN3L/S, DENV NS3, and β-Actin. (F) RT-qPCR quantification of DENV genomic RNA and RTN3S mRNA in Huh7 cells treated with DENV exosomes (+Exo) or with active DENV infection, normalized to 18S rRNA. Data in panels (B), (C), and (F) represent mean ± SEM of ≥3 independent experiments; statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; ns = not significant).

Figure 1.

Dengue virus infection upregulates RTN3 isoforms and promotes exosome release in Huh7 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Huh7 cell lysates without (Ctrl) or with Dengue virus (DENV) infection. Membranes were probed for RTN3 long (RTN3L, ~100 kDa) and short (RTN3S, ~25 kDa) isoforms, Dengue NS3 (~68 kDa), and β-Actin (~42 kDa) as a loading control. (B) RT-qPCR quantification of RTN3L and RTN3S mRNA in Huh7 cells ± DENV, normalized to 18S rRNA. The label ND denotes ‘not detected’. (C) NanoFlow Cytometry analysis (NanoFCM) of purified exosomes from Huh7 culture supernatants. Left: size-distribution histograms (30-150 nm) for exosomes from mock or DENV-infected cells. Right: bar graph of exosome concentration (particles/mL). (D) Western blots of whole-cell lysate (Huh7) and purified exosome fractions (Huh Exo, DENV Exo). Exosomal markers HSP70 and CD63 were assessed, whereas the ER protein Calnexin was probed to ascertain the purity of the exosome preparation. (E) Huh7 cells infected with DENV were either untreated or co-treated with purified DENV-derived exosomes (+Exo). Cell lysates were western blotted then probed for RTN3L/S, DENV NS3, and β-Actin. (F) RT-qPCR quantification of DENV genomic RNA and RTN3S mRNA in Huh7 cells treated with DENV exosomes (+Exo) or with active DENV infection, normalized to 18S rRNA. Data in panels (B), (C), and (F) represent mean ± SEM of ≥3 independent experiments; statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; ns = not significant).

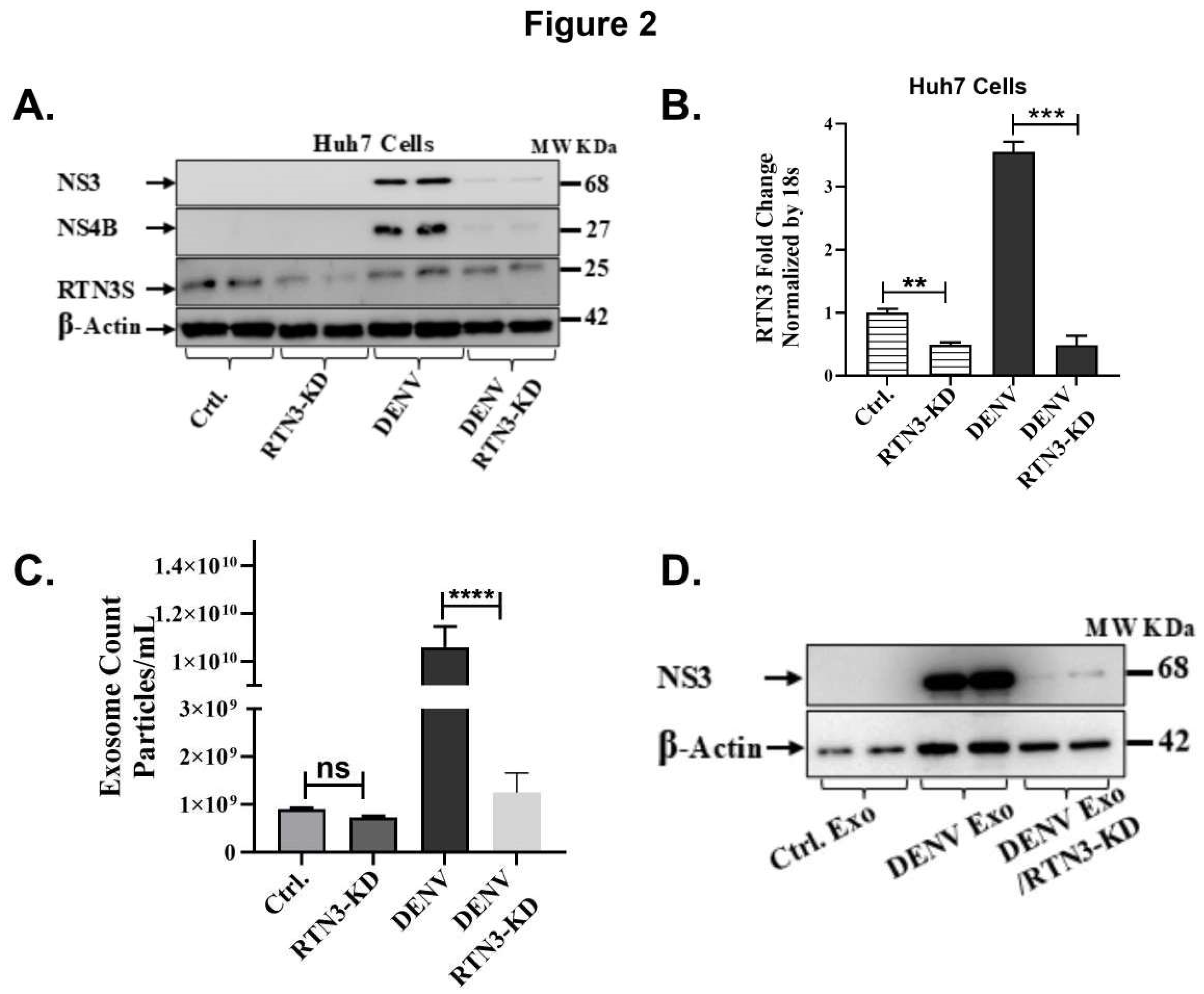

Figure 2.

RTN3 knockdown abrogates RTN3S expression and inhibits Dengue-induced exosome release in Huh7 cells. (A) Western blot of Huh7 cell lysates after transfection with control siRNA (Ctrl) or RTN3-targeting siRNA (RTN3-KD) followed by DENV infection. Blots were probed for DENV NS3 (~68 kDa), NS4B (~27 kDa), RTN3S (~25 kDa, arrow), and β-Actin (~42 kDa). (B) RT-qPCR of RTN3 mRNA in Huh7 cells (Ctrl or RTN3-KD, ± DENV), normalized to 18S rRNA. (C) NanoFCM analysis of exosome release for each condition. Control and RTN3-KD cells without infection release few exosomes (ns). (D) Western blot of exosome preparations from Ctrl (mock), DENV, and DENV+RTN3-KD conditions. Probing for DENV NS3 shows that exosomes from infected cells contain NS3, and this viral cargo is strongly diminished when RTN3 is knocked down. β-Actin is shown as a control. Data (B,C) are mean ± SEM of ≥3 experiments; significance by ANOVA or t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; ns = not significant).

Figure 2.

RTN3 knockdown abrogates RTN3S expression and inhibits Dengue-induced exosome release in Huh7 cells. (A) Western blot of Huh7 cell lysates after transfection with control siRNA (Ctrl) or RTN3-targeting siRNA (RTN3-KD) followed by DENV infection. Blots were probed for DENV NS3 (~68 kDa), NS4B (~27 kDa), RTN3S (~25 kDa, arrow), and β-Actin (~42 kDa). (B) RT-qPCR of RTN3 mRNA in Huh7 cells (Ctrl or RTN3-KD, ± DENV), normalized to 18S rRNA. (C) NanoFCM analysis of exosome release for each condition. Control and RTN3-KD cells without infection release few exosomes (ns). (D) Western blot of exosome preparations from Ctrl (mock), DENV, and DENV+RTN3-KD conditions. Probing for DENV NS3 shows that exosomes from infected cells contain NS3, and this viral cargo is strongly diminished when RTN3 is knocked down. β-Actin is shown as a control. Data (B,C) are mean ± SEM of ≥3 experiments; significance by ANOVA or t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; ns = not significant).

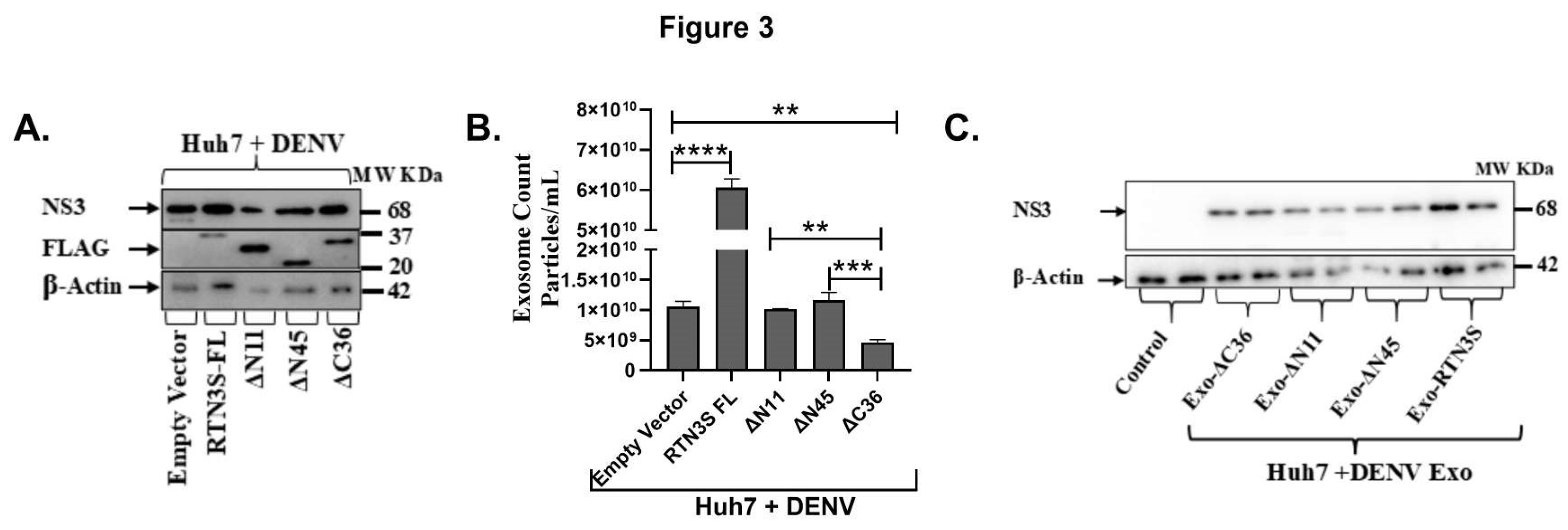

Figure 3.

The C-terminal domain of RTN3S is required for exosome production and viral transfer. (A) Western blot of Huh7 cells infected with DENV and transfected with empty vector (EV), full-length FLAG-RTN3S (FL), or deletion mutants (ΔN11, ΔN45 remove N-terminal regions; ΔC36 removes C-terminal tail). Membranes were probed with anti-FLAG to detect RTN3S constructs (all ~20- 37 kDa) and anti-DENV NS3 (~68 kDa); β-Actin (~42 kDa) is a loading control. (B) NanoFCM quantification of exosome release under each condition. The bar graph shows exosome concentration (particles/mL) for EV, RTN3S-FL, ΔN11, ΔN45, and ΔC36. Data are mean ± SEM (n=3). (C) Huh7 cells were treated with exosomes from donor cells expressing each construct (lanes: no-exosome control, Exo-ΔC36, Exo-ΔN11, Exo-ΔN45, Exo-RTN3S-FL). Cell lysates were blotted for DENV NS3 (~68 kDa) and β-Actin.

Figure 3.

The C-terminal domain of RTN3S is required for exosome production and viral transfer. (A) Western blot of Huh7 cells infected with DENV and transfected with empty vector (EV), full-length FLAG-RTN3S (FL), or deletion mutants (ΔN11, ΔN45 remove N-terminal regions; ΔC36 removes C-terminal tail). Membranes were probed with anti-FLAG to detect RTN3S constructs (all ~20- 37 kDa) and anti-DENV NS3 (~68 kDa); β-Actin (~42 kDa) is a loading control. (B) NanoFCM quantification of exosome release under each condition. The bar graph shows exosome concentration (particles/mL) for EV, RTN3S-FL, ΔN11, ΔN45, and ΔC36. Data are mean ± SEM (n=3). (C) Huh7 cells were treated with exosomes from donor cells expressing each construct (lanes: no-exosome control, Exo-ΔC36, Exo-ΔN11, Exo-ΔN45, Exo-RTN3S-FL). Cell lysates were blotted for DENV NS3 (~68 kDa) and β-Actin.

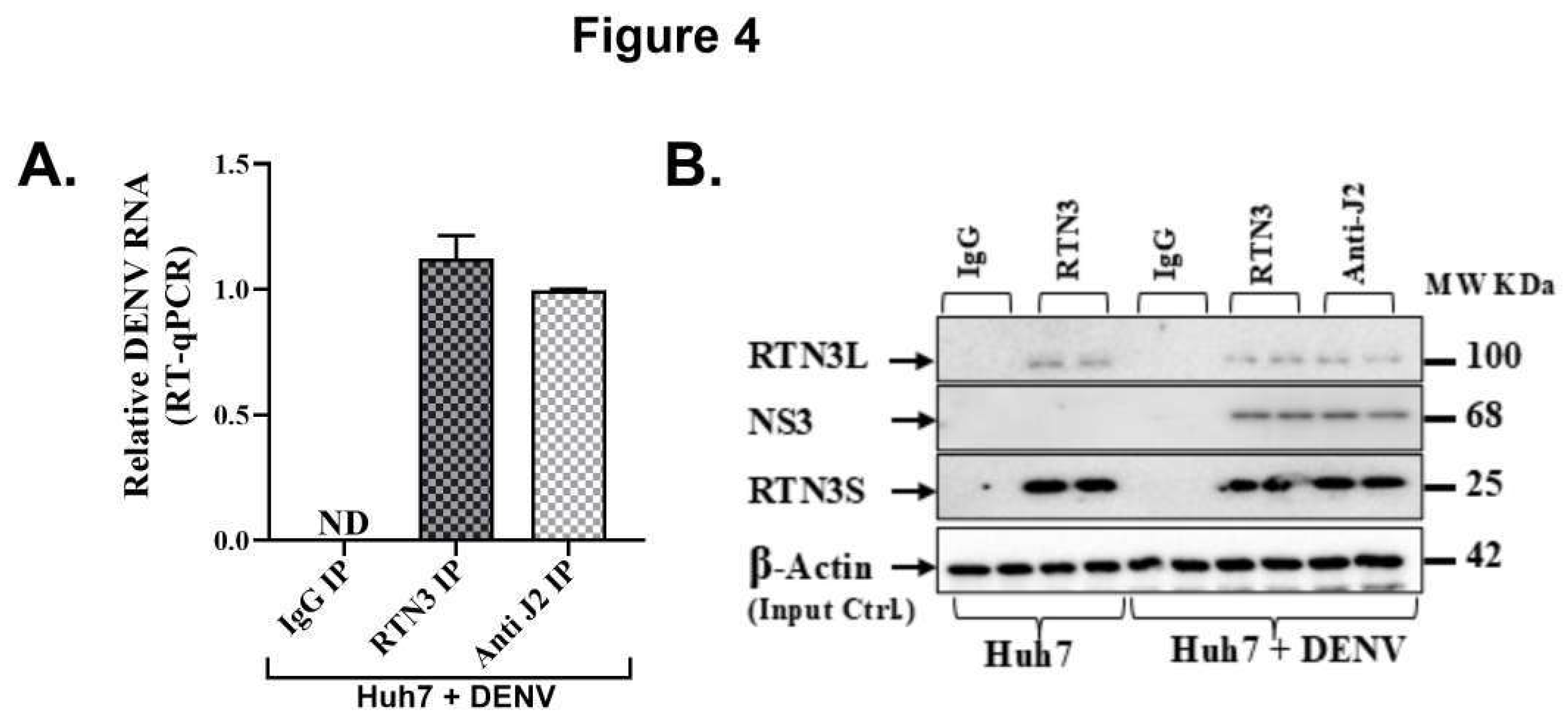

Figure 4.

RTN3 associates with Dengue viral double-stranded RNA and NS3 protein in infected Huh7 cells. (A) RT-qPCR detection of DENV genomic RNA in immunoprecipitated material from Huh7 cells 72 h after DENV infection. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-RTN3 or anti-dsRNA (J2) antibodies; non-specific IgG was used as a negative control. Bars show relative enrichment of viral RNA in each IP (normalized to input). (B) Western blot of the IP eluates from Huh7+DENV lysates. Lanes: IgG IP (Huh7+DENV), RTN3 IP (Huh7+DENV), and anti-dsRNA (J2) IP (Huh7+DENV), with input lysate as control. Blots were probed for RTN3L (~100 kDa), DENV NS3 (~68 kDa), and RTN3S (~25 kDa).

Figure 4.

RTN3 associates with Dengue viral double-stranded RNA and NS3 protein in infected Huh7 cells. (A) RT-qPCR detection of DENV genomic RNA in immunoprecipitated material from Huh7 cells 72 h after DENV infection. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-RTN3 or anti-dsRNA (J2) antibodies; non-specific IgG was used as a negative control. Bars show relative enrichment of viral RNA in each IP (normalized to input). (B) Western blot of the IP eluates from Huh7+DENV lysates. Lanes: IgG IP (Huh7+DENV), RTN3 IP (Huh7+DENV), and anti-dsRNA (J2) IP (Huh7+DENV), with input lysate as control. Blots were probed for RTN3L (~100 kDa), DENV NS3 (~68 kDa), and RTN3S (~25 kDa).

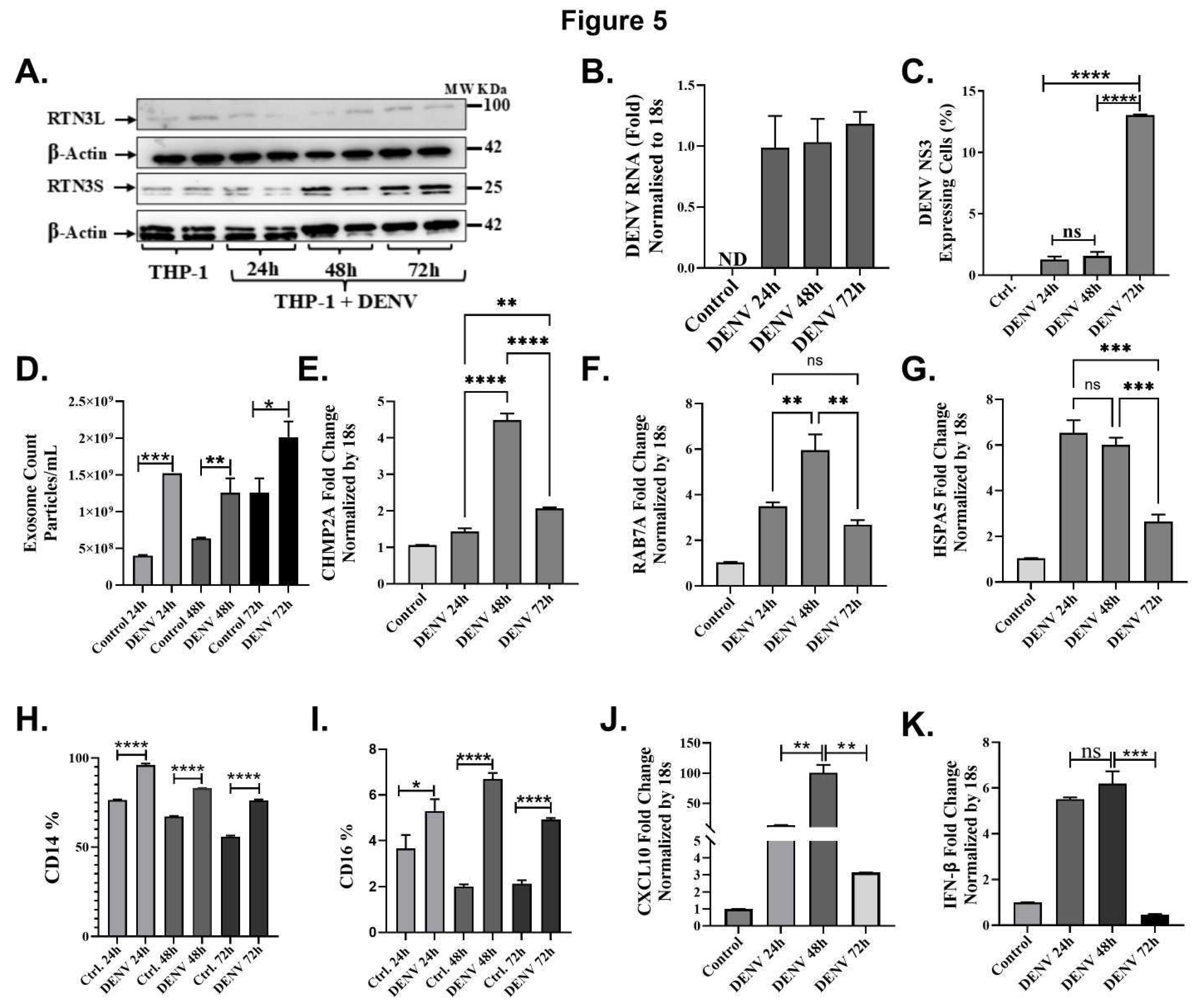

Figure 5.

Dengue virus induces RTN3 expression, exosome release, and innate immune responses in THP-1 monocytes. (A) Western blot of THP-1 cells uninfected (Ctrl) or infected with DENV for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Blots were probed for RTN3L (~100 kDa) and RTN3S (~25 kDa), with β-Actin (~42 kDa) as a loading control. (B) RT-qPCR of DENV genomic RNA in THP-1 cells (normalized to 18S) at each time point. (C) Flow cytometry of THP-1 cells for DENV NS3. (D) NanoFCM evaluation of exosomes in THP-1 culture supernatants with and without DENV infection. (E-G) RT-qPCR of THP-1 mRNA (normalized to 18S) for exosome biogenesis, trafficking genes and chaperone protein: (E) CHMP2A, (F) RAB7A, and (G) HSPA5. (H-I) Flow cytometry quantification of monocyte markers. Bars show the percentage of cells expressing CD14 or CD16 in mock vs DENV samples. (J-K) RT-qPCR of cytokine mRNAs: CXCL10 and IFN-β (normalized to 18S). Data (A–I) are mean ± SEM of triplicates; significance by ANOVA or t-test (ns = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

Dengue virus induces RTN3 expression, exosome release, and innate immune responses in THP-1 monocytes. (A) Western blot of THP-1 cells uninfected (Ctrl) or infected with DENV for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Blots were probed for RTN3L (~100 kDa) and RTN3S (~25 kDa), with β-Actin (~42 kDa) as a loading control. (B) RT-qPCR of DENV genomic RNA in THP-1 cells (normalized to 18S) at each time point. (C) Flow cytometry of THP-1 cells for DENV NS3. (D) NanoFCM evaluation of exosomes in THP-1 culture supernatants with and without DENV infection. (E-G) RT-qPCR of THP-1 mRNA (normalized to 18S) for exosome biogenesis, trafficking genes and chaperone protein: (E) CHMP2A, (F) RAB7A, and (G) HSPA5. (H-I) Flow cytometry quantification of monocyte markers. Bars show the percentage of cells expressing CD14 or CD16 in mock vs DENV samples. (J-K) RT-qPCR of cytokine mRNAs: CXCL10 and IFN-β (normalized to 18S). Data (A–I) are mean ± SEM of triplicates; significance by ANOVA or t-test (ns = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

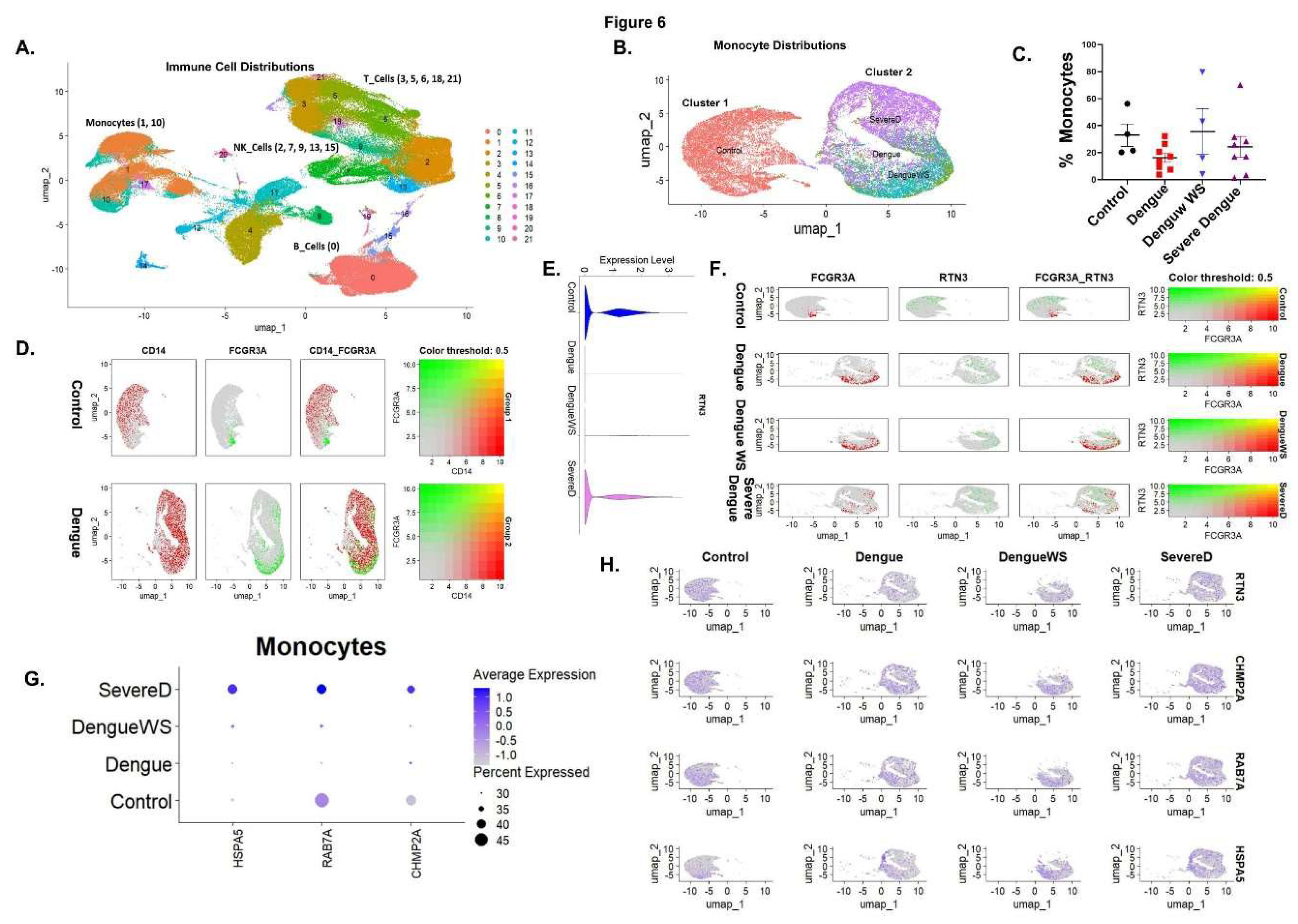

Figure 6.

Single-cell transcriptomics of blood cells reveal monocyte subsets and RTN3-related signatures in Dengue patients. (A) UMAP projection of PBMCs from healthy controls and Dengue patients, colored by major immune cell types (monocytes, T cells, B cells, NK cells, etc.). Monocytes form a distinct cluster (red). (B) UMAP highlighting monocyte subclusters: cluster 1 (blue) contains mainly healthy-donor cells, whereas cluster 2 (orange) is dominated by Dengue patient cells (including DFWS and severe cases). (C) Bar graph of the percentage of monocytes (CD14+ cells) among total PBMCs in each group (healthy control, Dengue fever (DF), Dengue with warning signs (DFWS), and severe Dengue (SD)). (D) Monocyte UMAP colored by expression of CD14 (red) and FCGR3A/CD16 (green) in healthy vs Dengue samples. Classical monocytes (CD14^hi, red) and non-classical monocytes (FCGR3A^hi, green) are indicated. (E) Violin plots of RTN3 mRNA expression in monocytes from each group. Dengue patient monocytes, especially from severe cases, show higher RTN3 expression than controls. (F) Feature scatter plots on the monocyte UMAP showing FCGR3A (red) and RTN3 (green) expression for each condition; yellow indicates co-expression. (G) Dot plot summarizing monocyte expression of HSPA5, RAB7A, and CHMP2A. Dot size corresponds to the proportion of cells expressing the gene; color indicates average expression. Dengue patient monocytes (DFWS, SD) display larger and darker dots for these genes, indicating upregulation. (H) UMAP feature plots of RTN3, CHMP2A, RAB7A, and HSPA5 in monocyte clusters across conditions, confirming stronger expression (yellow) of all four genes in Dengue patient monocytes.

Figure 6.

Single-cell transcriptomics of blood cells reveal monocyte subsets and RTN3-related signatures in Dengue patients. (A) UMAP projection of PBMCs from healthy controls and Dengue patients, colored by major immune cell types (monocytes, T cells, B cells, NK cells, etc.). Monocytes form a distinct cluster (red). (B) UMAP highlighting monocyte subclusters: cluster 1 (blue) contains mainly healthy-donor cells, whereas cluster 2 (orange) is dominated by Dengue patient cells (including DFWS and severe cases). (C) Bar graph of the percentage of monocytes (CD14+ cells) among total PBMCs in each group (healthy control, Dengue fever (DF), Dengue with warning signs (DFWS), and severe Dengue (SD)). (D) Monocyte UMAP colored by expression of CD14 (red) and FCGR3A/CD16 (green) in healthy vs Dengue samples. Classical monocytes (CD14^hi, red) and non-classical monocytes (FCGR3A^hi, green) are indicated. (E) Violin plots of RTN3 mRNA expression in monocytes from each group. Dengue patient monocytes, especially from severe cases, show higher RTN3 expression than controls. (F) Feature scatter plots on the monocyte UMAP showing FCGR3A (red) and RTN3 (green) expression for each condition; yellow indicates co-expression. (G) Dot plot summarizing monocyte expression of HSPA5, RAB7A, and CHMP2A. Dot size corresponds to the proportion of cells expressing the gene; color indicates average expression. Dengue patient monocytes (DFWS, SD) display larger and darker dots for these genes, indicating upregulation. (H) UMAP feature plots of RTN3, CHMP2A, RAB7A, and HSPA5 in monocyte clusters across conditions, confirming stronger expression (yellow) of all four genes in Dengue patient monocytes.

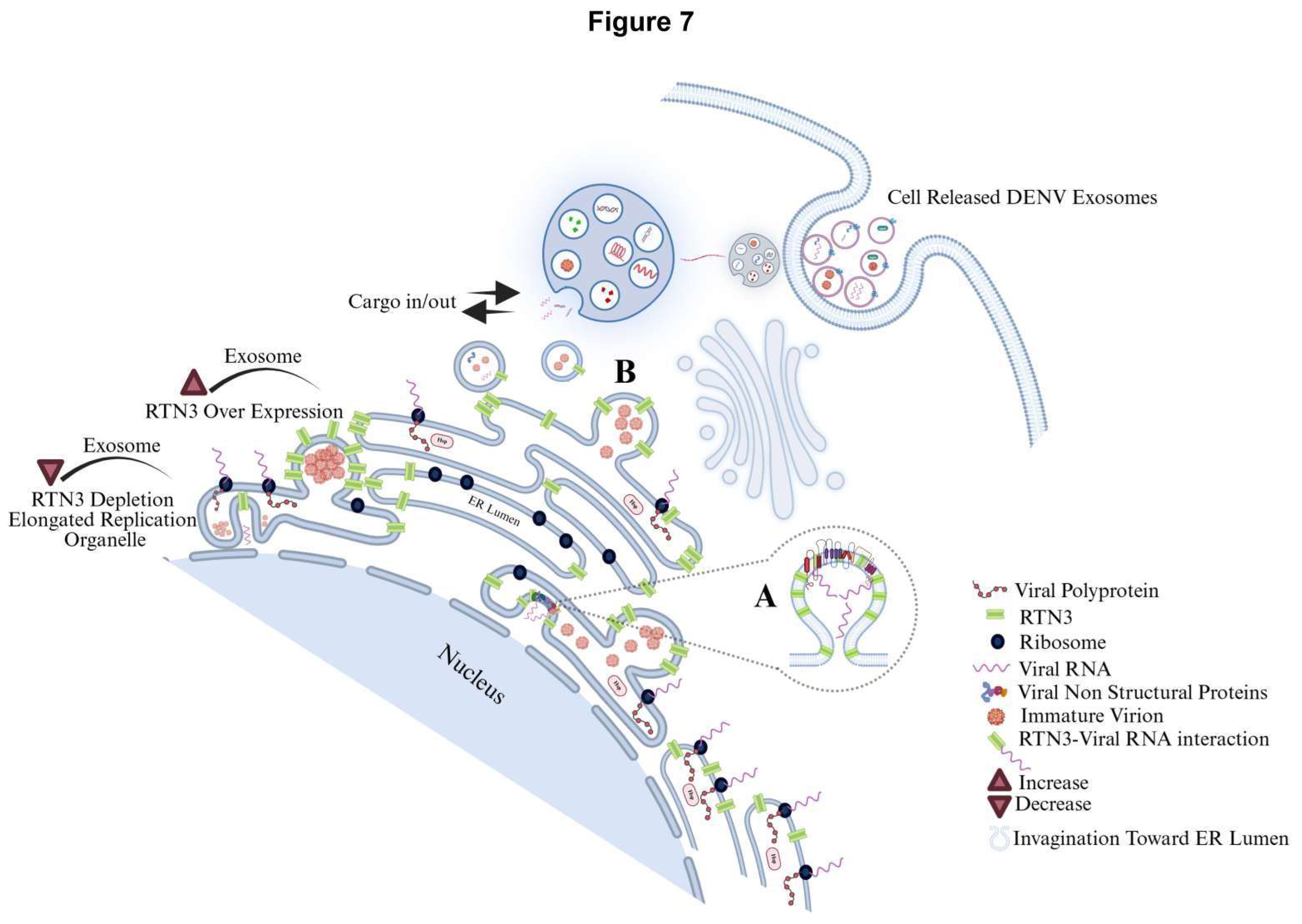

Figure 7.

Dengue virus manipulates the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) landscape through the short Reticulon-3 isoform (RTN3S) to generate infectious exosomes. Following DENV entry, positive-strand genomic RNA is translated on rough ER membranes. RTN3S (green hair-pin elements) accumulates at the peri-nuclear ER and sculpts it into bulb-like invaginations toward the ER lumen. These curved subdomains recruit ribosomes (navy spheres), newly synthesized viral polyprotein (dashed red coils), and non-structural replication factors (lavender icons), forming sealed single-membrane vesicle pockets that entrap double-stranded replicative DENV RNA (magenta helices). (A) Magnified inset in the graphic highlights how RTN3S helices directly clasp dsDENV RNA, creating a selective ribonucleoprotein scaffold that favours viral, over cellular, cargo. (B) Nascent RTN3S-dsDENV RNA vesicles bud from the ER and converge with early endosomes to seed multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Inside the maturing MVB, they become intraluminal vesicles destined to leave the cell as exosomes. A bold “cargo in/out” arrow at the MVB boundary mirrors RTN3S’s dual role: it both guides viral material into the endosomal lumen and licenses its export once the MVB fuses with the plasma membrane. The released exosomes (burgundy triangles) are depicted dispersing from the cell, each carrying replication-competent DENV RNA, non-structural proteins, and occasional immature virions, an immune-evasive inoculum primed for cell-to-cell spread. Modulating RTN3S levels alters every step in this pathway. RTN3S over-expression (upper left) intensifies ER curvature, increases the number of replication organelles, and drives a surge in cargo-rich exosome release. Conversely, RTN3S depletion (lower left) yields elongated, poorly scissioned replication tubules, drastically reduces vesicle trafficking to MVBs, and suppresses exosome output. These opposing phenotypes, annotated directly on the schematic, underscore RTN3S as a gatekeeper that links flaviviral RNA replication to selective exosome biogenesis and extracellular dissemination.

Figure 7.

Dengue virus manipulates the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) landscape through the short Reticulon-3 isoform (RTN3S) to generate infectious exosomes. Following DENV entry, positive-strand genomic RNA is translated on rough ER membranes. RTN3S (green hair-pin elements) accumulates at the peri-nuclear ER and sculpts it into bulb-like invaginations toward the ER lumen. These curved subdomains recruit ribosomes (navy spheres), newly synthesized viral polyprotein (dashed red coils), and non-structural replication factors (lavender icons), forming sealed single-membrane vesicle pockets that entrap double-stranded replicative DENV RNA (magenta helices). (A) Magnified inset in the graphic highlights how RTN3S helices directly clasp dsDENV RNA, creating a selective ribonucleoprotein scaffold that favours viral, over cellular, cargo. (B) Nascent RTN3S-dsDENV RNA vesicles bud from the ER and converge with early endosomes to seed multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Inside the maturing MVB, they become intraluminal vesicles destined to leave the cell as exosomes. A bold “cargo in/out” arrow at the MVB boundary mirrors RTN3S’s dual role: it both guides viral material into the endosomal lumen and licenses its export once the MVB fuses with the plasma membrane. The released exosomes (burgundy triangles) are depicted dispersing from the cell, each carrying replication-competent DENV RNA, non-structural proteins, and occasional immature virions, an immune-evasive inoculum primed for cell-to-cell spread. Modulating RTN3S levels alters every step in this pathway. RTN3S over-expression (upper left) intensifies ER curvature, increases the number of replication organelles, and drives a surge in cargo-rich exosome release. Conversely, RTN3S depletion (lower left) yields elongated, poorly scissioned replication tubules, drastically reduces vesicle trafficking to MVBs, and suppresses exosome output. These opposing phenotypes, annotated directly on the schematic, underscore RTN3S as a gatekeeper that links flaviviral RNA replication to selective exosome biogenesis and extracellular dissemination.

Table 1.

Sequences of Oligonucleotides.

Table 1.

Sequences of Oligonucleotides.

| Primer |

Sequence 5’ to 3’ |

| RTN3S |

F: GGAGAGATGTGAAGAAGACTGCC

R: AGATCCTGAAGCTGATGGTGA |

| RTN3L |

F: GTAGGGAGGCTAAAACTGCA

R: CTCCTGAAACTTTGGATGGAGA |

| DENV |

F: TTATCAGTTCAAAATCCAATGTTGGT

R: AGGAGGAAGCTGGGTTGACA |

| CHMP2A |

F: GAAGACGCCAGAGGAGCTACTGC

R: GCTTGGCCATCTTCTTAATGTCTGC |

| RAB7A |

F: GTCGGGAAGACATCACTCA

R: CTAGCCTGTCATCCACCAT |

| HSPA5 |

F: GGGAGGTGTCATGACCAAAC

R: GCAGGAGGAATTCCAGTCAG |

| CXCL10 |

F: GTGGATGTTCTGACCCTGCT

R: GGAGGATGGCAGTGGAAGTC |

| IFNB |

F: TGGGAGGCTTGAATACTGCCTCAA

R: TCCTTGGCCTTCAGGTAATGCAGA |

| 18S |

F: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT

R: CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG |

| gRNA cloning verification |

F: AGCTGCAGCTCTTCGTC

R: TCGGCGGCCACTCAGTC |

| gRNA sequence targeting RTN3S |

CTCGGCTCCGAAGGACGACG |