Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

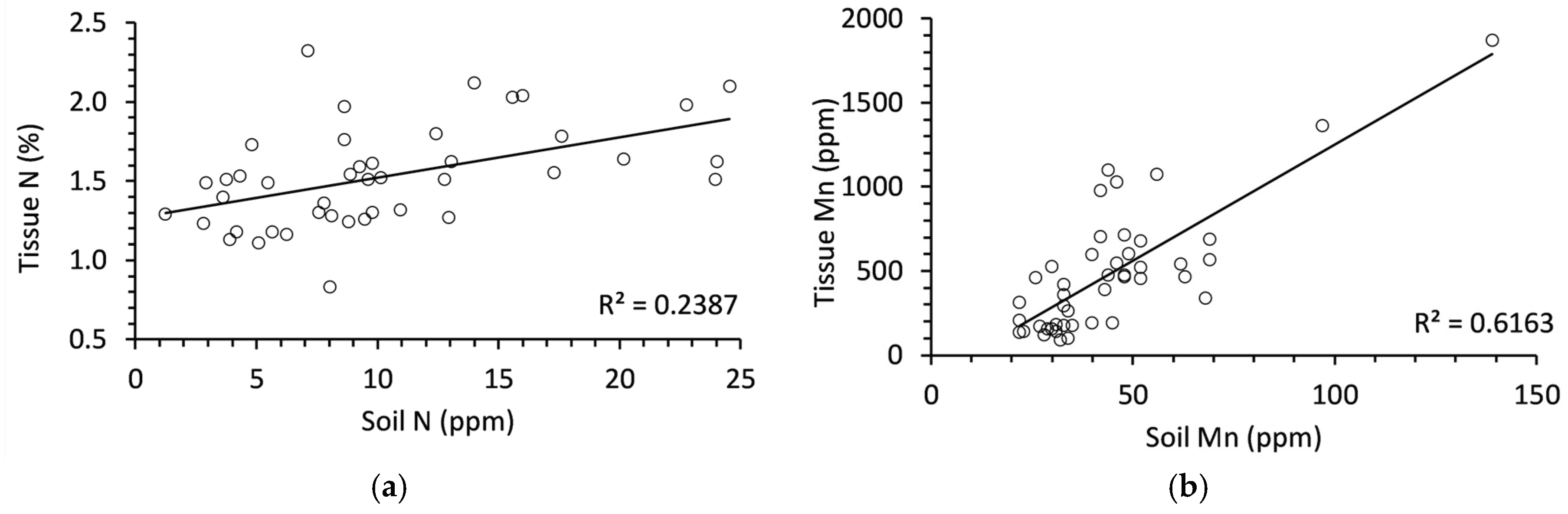

2.1. Soil and Tissue Nutrition

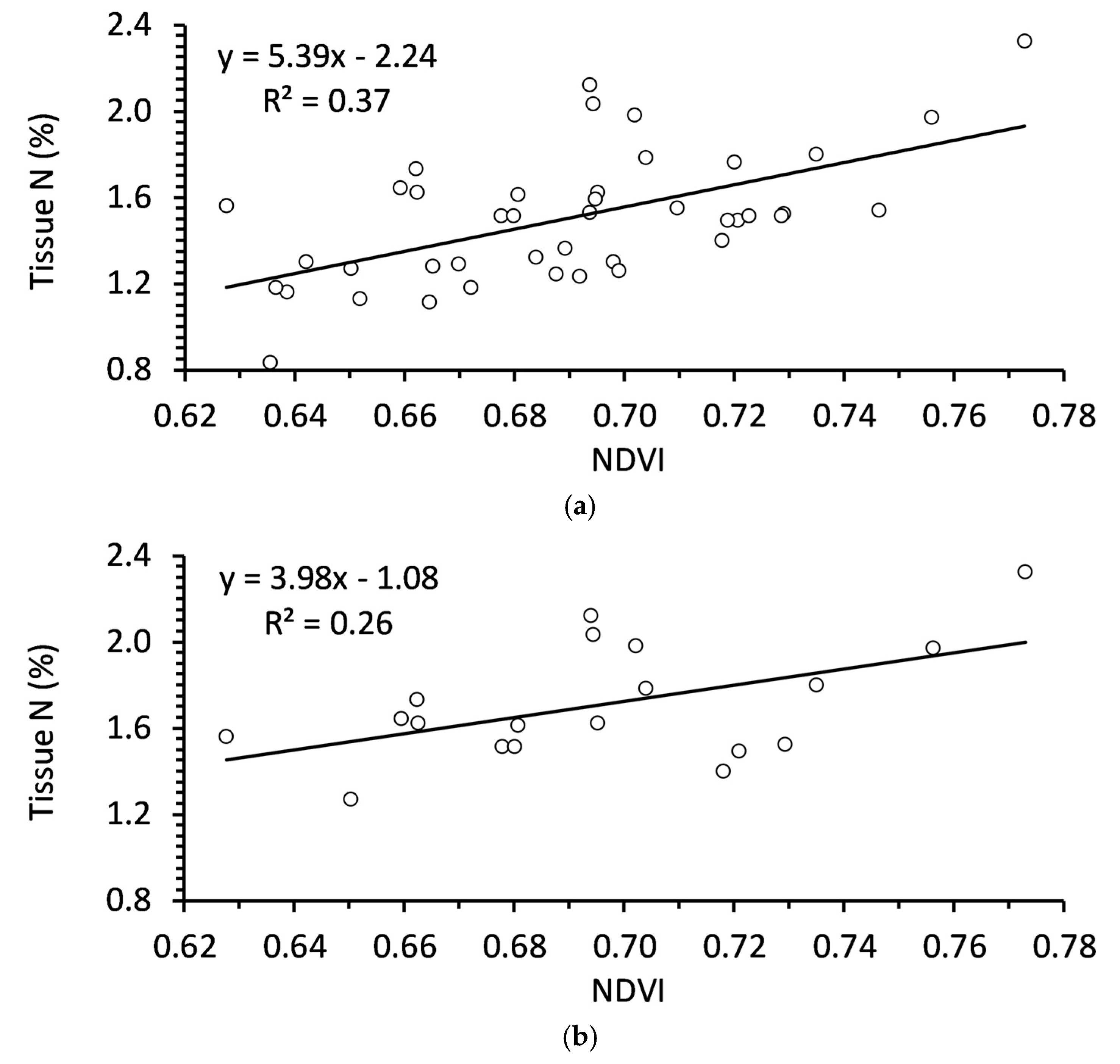

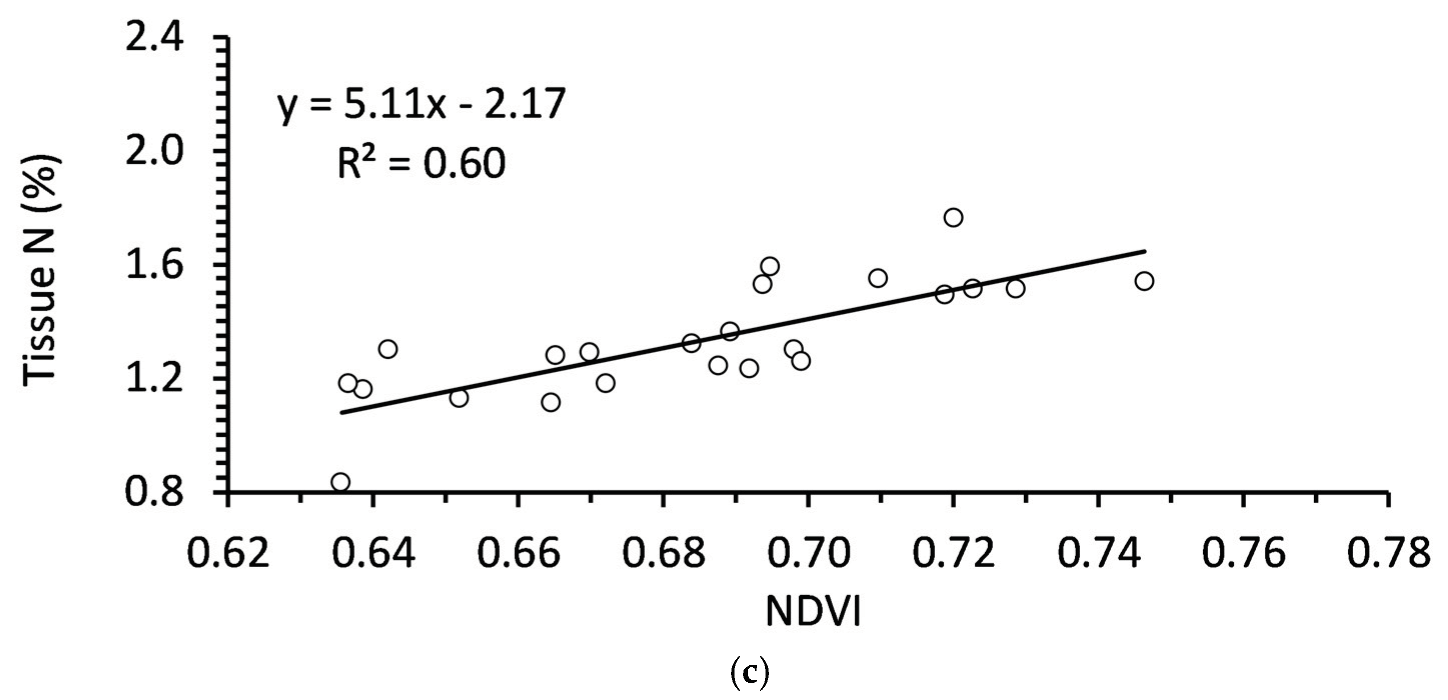

2.2. NDVI and Nutrition

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

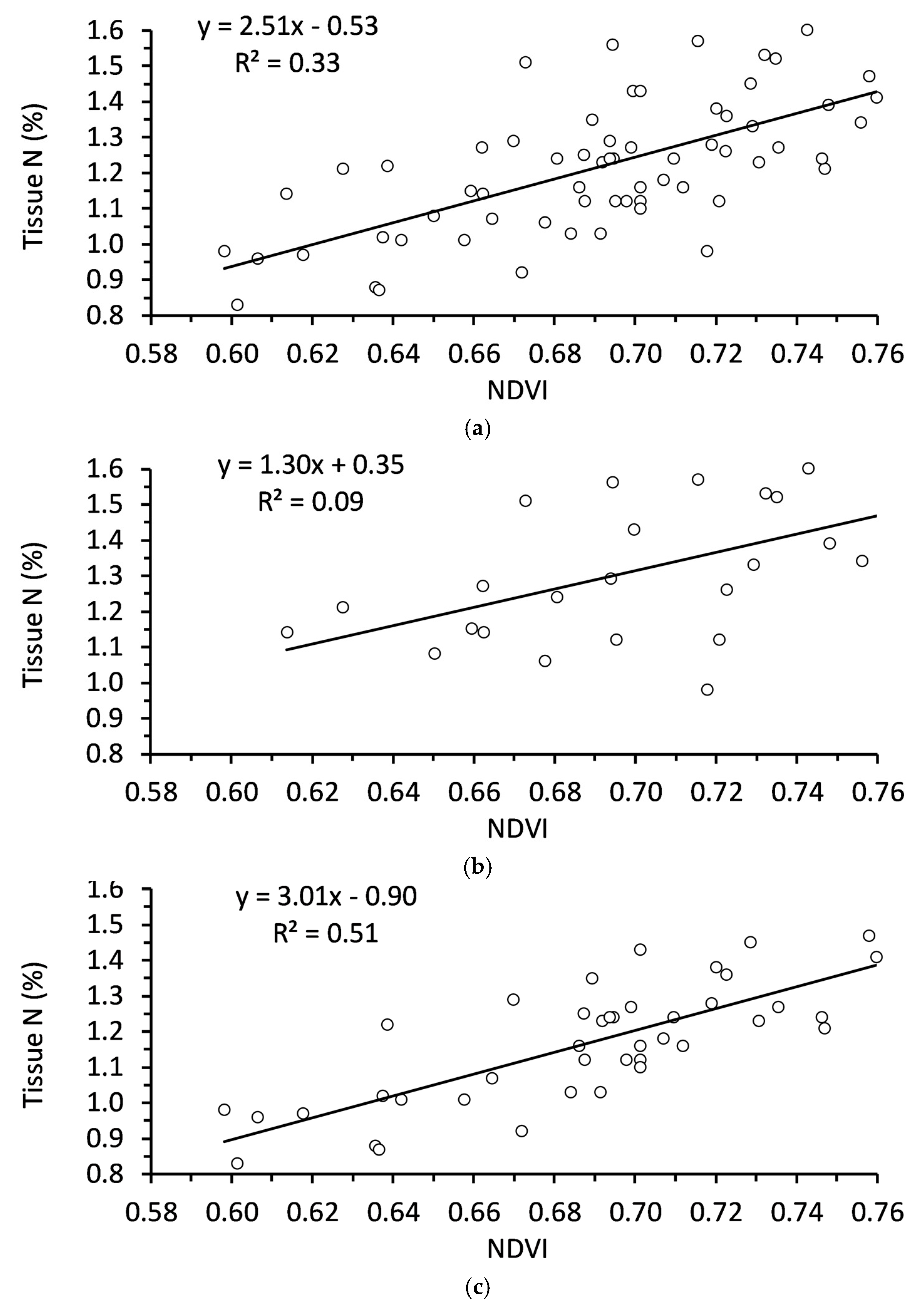

4.1. Site Description

4.2. Nutrient Analysis

4.3. Aerial Image Acquisition and Equipment

4.4. Image Processing

4.5. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collier, J.; MacLean, D.A.; D’Orangeville, L.; Taylor, A.R. A Review of Climate Change Effects on the Regeneration Dynamics of Balsam Fir. The Forestry Chronicle 2022, 98, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.T.; Lada, R.R.; MacDonald, G.E.; Caldwell, C.D.; Udenigwe, C.C. Changes in Polar Lipid Composition in Balsam Fir during Seasonal Cold Acclimation and Relationship to Needle Abscission. IJMS 2023, 24, 15702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.M.; Honkala, B.H. Silvics of North America: Conifers; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbandeh, M. Farm Cash Receipts Christmas Trees Canada 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/449337/farm-cash-receipts-of-christmas-trees-canada/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Thiagarajan, A.; MacDonald, M.T.; Lada, R. Environmental and Hormonal Physiology of Postharvest Needle Abscission in Christmas Trees. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2016, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastagner, G.A.; Benson, D.M. The Christmas Tree: Traditions, Production, and Diseases. Plant Health Progress 2000, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Landgren, C.; Fletcher, R.; Bondi, M.; Withrow-Robinson, B.; Chastagner, G. Christmas Tree Nutrient Management Guide; Oregon State University: Oregon, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne, M.; Adegbidi, H.G.; Assamoi, A.J. Organic Fertilization of Christmas Tree (Abies Balsamea (L.) Mill.) Plantations with Poultry Manure in Northwestern New Brunswick, Canada. The Forestry Chronicle 2019, 95, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.T.; Lada, R.R. Seasonal Changes in Soil and Tissue Nutrition in Balsam Fir and Influences on Postharvest Needle Abscission. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 2018, 33, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.T.; Lada, R.R.; Veitch, R.S. Seasonal Changes in Balsam Fir Needle Abscission Patterns and Links to Environmental Factors. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 2017, 32, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, J.R. Growing Christmas Trees.

- Rideout, J.W.; Overstreet, L.F. A Survey of Fertility Practices, Soil Fertility Status, and Tree Nutrient Status on Eastern North Carolina Christmas Tree Farms. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2004, 35, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A. Christmas Trees for Pleasure; Rutgers University Press: Piskataway, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-8135-3650-7. [Google Scholar]

- Koelling, M.R. Fertilization Recommendations for Fraser Fir: Part II - Established Plantings. Mich Christmas Tree J 2002, 49, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fixen, P.E.; West, F.B. Nitrogen Fertilizers: Meeting Contemporary Challenges. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2002, 31, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slesak, R.A.; Briggs, R.D. Christmas Tree Response to N Fertilization and the Development of Critical Foliar N Levels in New York. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry 2007, 24, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.L. Forest Fertilizers. J Forest 1987, 85, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, H.; Wang, P. Quantitative modelling for leaf nitrogen content of winter wheat using UAV-based hyperspectral data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2017, 38, 2117–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtowicz, M.; Wojtowics, A.; Piekarczyk, J. Application of Remote Sensing Methods in Agriculture. Communications in Biometry and Crop Science 2016, 11, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, M.S.; Pearse, G.D.; Dash, J.P.; Melia, N.; Leonardo, E.M.C. Application of Remote Sensing Technologies to Identify Impacts of Nutritional Deficiencies on Forests. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2019, 149, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillesand, T.; Kiefer, R.W.; Chipman, J. Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation, 7th ed.; Joh Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Shao, G. Drone Remote Sensing for Forestry Research and Practices. J. For. Res. 2015, 26, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R.; Daughtry, C.S.T. What Good Are Unmanned Aircraft Systems for Agricultural Remote Sensing and Precision Agriculture? International Journal of Remote Sensing 2018, 39, 5345–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliti, S.; Ene, L.T.; Gobakken, T.; Naesset, E. Use of Partial-Coverage UAV Data in Sampling for Large Scale Forest Inventories. Remote Sensing Environ 2017, 194, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliti, S.; Ørka, H.; Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E. Inventory of Small Forest Areas Using an Unmanned Aerial System. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 9632–9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Turner, B.J.; Dury, Stephen J. ; Wallis, I.R.; Foley, W.J. Estimating Foliage Nitrogen Concentration from HYMAP Data Using Continuum Removal Analysis. Remote Sensing Environ. 2004, 93, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.E.; Aber, J.D. High Spectral Resolution Remote Sensing of Forest Canopy Lignin, Nitrogen, and Ecosystem Processes. Ecological Applications 1997, 7, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P.A.; Foster, J.R.; Chastain, R.A.; Currie, W.S. Application of Imaging Spectroscopy to Mapping Canopy Nitrogen in the Forests of the Central Appalachian Mountains Using Hyperion and Aviris. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2003, 41, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagolski, F.; Pinel, V.; Romier, J.; Alcayde, D.; Fontanari, J.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.P.; Giordano, G.; Marty, G.; Mougin, E.; Joffre, R. Forest Canopy Chemistry with High Spectral Resolution Remote Sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.-L.; Martin, M.E.; Plourde, L.; Ollinger, S.V. Analysis of Hyperspectral Data for Estimation of Temperate Forest Canopy Nitrogen Concentration: Comparison between an Airborne (Aviris) and a Spaceborne (Hyperion) Sensor. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2003, 41, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Kneubühler, M.; Psomas, A.; Itten, K.; Zimmermann, N.E. Estimating Foliar Biochemistry from Hyperspectral Data in Mixed Forest Canopy. Forest Ecology and Management 2008, 256, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications [Research Article. Journal of Sensors 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A Commentary Review on the Use of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in the Era of Popular Remote Sensing. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegler, F.J. Preprocessing Transformations and Their Effects on Multispectral Recognition.; 1969.

- Pastor-Guzman, J.; Atkinson, P.; Dash, J.; Rioja-Nieto, R. Spatiotemporal Variation in Mangrove Chlorophyll Concentration Using Landsat 8. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 14530–14558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Camarero, J.J.; Olano, J.M.; Martín-Hernández, N.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Gazol, A.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Bhuyan, U.; El Kenawy, A. Diverse Relationships between Forest Growth and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index at a Global Scale. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 187, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.O.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Decuyper, M.; De Bruin, S.; Herold, M. 50 Years of Water Extraction in the Pampa Del Tamarugal Basin: Can Prosopis Tamarugo Trees Survive in the Hyper-Arid Atacama Desert (Northern Chile)? Journal of Arid Environments 2016, 124, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, B.W.; Green, V.S.; Hashem, A.A.; Massey, J.H.; Shew, A.M.; Adviento-Borbe, M.A.A.; Milad, M. Determining Nitrogen Deficiencies for Maize Using Various Remote Sensing Indices. Precision Agric 2022, 23, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Paul, M.; Rahaman, D.M.M.; Debnath, T.; Zheng, L.; Baby, T.; Schmidtke, L.M.; Rogiers, S.Y. Identifying Individual Nutrient Deficiencies of Grapevine Leaves Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, D.; McInerney, D.; De Kerchove, R.V.; Goyens, C.; Balaji, P.; Byrne, K.A. Detecting Nutrient Deficiency in Spruce Forests Using Multispectral Satellite Imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2020, 86, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, C. Advances in Remote Sensing of Agriculture: Context Description: Existing Operational Monitoring Systems and Major Information Needs. Remote Sensing 2013, 5, 949–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow, J. Linear Regression Modeling for the Estimation of Oil Palm Age from Landsat T<. Internation Journal of Remote Sensing 2001, 22, 2243–2264. [Google Scholar]

- Chemura, A.; Mutanga, O.; Dube, T. Integrating Age in the Detection and Mapping of Incongruous Patches in Coffee (Coffea Arabica) Plantations Using Multi-Temporal Landsat 8 NDVI Anomalies. Internation Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2017, 57, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banday, M.; Bhardwaj, D.R.; Pala, N.A. Influence of Forest Type, Altitude and NDVI on Soil Properties in Forests of North Western Himalaya, India. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, N.; Govaerts, B.; Sayre, K.D.; Deckers, J.; François, I.M.; Dendooven, L. Using NDVI and Soil Quality Analysis to Assess Influence of Agronomic Management on Within-Plot Spatial Variability and Factors Limiting Production. Plant Soil 2009, 317, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baligar, V.C.; Fageria, N.K.; He, Z.L. Nutrient Use Efficiency in Plants. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2001, 32, 921–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, J.E.; Carroll, A.L. Development of an Index of Balsam Fir Vigor by Foliar Spectral Reflectance. Remote Sensing Environ 1999, 69, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaugh, T.J.; Lee Allen, H.; Zutter, B.R.; Quicke, H.E. Vegetation Control and Fertilization in Midrotation Pinus Taeda Stands in the Southeastern United States. Ann. For. Sci. 2003, 60, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Allen, H.; Fox, T.R.; Campbell, R.G. What Is Ahead for Intensive Pine Plantation Silviculture in the South? Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 2005, 29, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, H.O.; Fristoe, C. Response of Midrotation Pine Stands to Fertilizer and Herbicide Application in the Western Gulf Coastal Plain. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 2013, 37, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.M. The Complex Regulation of Senescence. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2012, 31, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Slovin, J.P.; Hendrickson, A.M. Two Genetically Discrete Pathways Convert Tryptophan to Auxin: More Redundancy in Auxin Biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci 2003, 8, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.Y.S.; D’Odorico, P.; Arain, M.A.; Ensminger, I. Tracking the Phenology of Photosynthesis Using Carotenoid-Sensitive and near Infrared Reflectance Nvegetation Indices in a Temperatre Evergreen and Mixed Deciduous Forest. New Phytologist 2020, 226, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamon, J.A.; Huemmrich, K.F.; Wong, C.Y.S.; Ensminger, I.; Garrity, S.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Noormets, A.; Peñuelas, J. A Remotely Sensed Pigment Index Reveals Photosynthetic Phenology in Evergreen Conifers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 13087–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MicaSense User Guide for MicaSense Sensors. MicaSense Knowledge Base 2023.

- Agisoft, L.L.C. MicaSense Altum processing workflow (including Reflectance Calibration) in Agisoft Metashape Professional. Helpdesk Portal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, M.; Mather, P.M. Support Vector Machines for Classification in Remote Sensing. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2005, 26, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.S.R.I. Train Support Vector Machine Classifier (Spatial Analyst. In ArcGIS Pro documentation; 2023.

- Antognelli, S. NDVI and NDMI Vegetation Indices: Instructions for Use. Agricolus 2018.

- E.S.R.I. NDVI function. In ArcGIS Pro documentation; 2023.

| Nutrient | Site 1 | Site 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (ppm) | 13.81 | ± | 1.38 | 7.24 | ± | 0.71 |

| P (kg/ha) | 360.86 | ± | 33.37 | 576.88 | ± | 28.28 |

| K (kg/ha) | 248.19 | ± | 19.58 | 130.52 | ± | 7.25 |

| Ca (kg/ha) | 1960.95 | ± | 88.80 | 2070.92 | ± | 71.66 |

| Mg (kg/ha) | 363.57 | ± | 25.57 | 330.04 | ± | 13.26 |

| Na (kg/ha) | 54.62 | ± | 22.09 | 29.44 | ± | 1.32 |

| S (kg/ha) | 24.86 | ± | 0.54 | 23.60 | ± | 0.59 |

| Al (ppm) | 1421.14 | ± | 20.24 | 1399.52 | ± | 24.20 |

| Cu (ppm) | 1.18 | ± | 0.04 | 2.00 | ± | 0.15 |

| Fe (ppm) | 142.10 | ± | 6.77 | 137.72 | ± | 6.67 |

| Mn (ppm) | 31.67 | ± | 1.54 | 54.88 | ± | 4.52 |

| Zn (ppm) | 3.09 | ± | 0.19 | 1.05 | ± | 0.06 |

| Nutrient | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (ppm) | 31.10 | ± | 3.66 | 1.99 | ± | 0.22 | 2.11 | ± | 0.14 |

| P (kg/ha) | 397.92 | ± | 34.15 | 611.68 | ± | 24.82 | 626.76 | ± | 23.20 |

| K (kg/ha) | 359.96 | ± | 34.86 | 166.04 | ± | 10.97 | 334.36 | ± | 17.70 |

| Ca (kg/ha) | 2190.64 | ± | 93.81 | 2264.68 | ± | 73.78 | 1959.68 | ± | 56.03 |

| Mg (kg/ha) | 381.00 | ± | 26.61 | 355.88 | ± | 16.77 | 349.08 | ± | 14.50 |

| Na (kg/ha) | 71.16 | ± | 24.00 | 34.44 | ± | 1.29 | 32.92 | ± | 1.60 |

| S (kg/ha) | 34.60 | ± | 1.21 | 29.36 | ± | 0.55 | 28.16 | ± | 0.50 |

| Al (ppm) | 1538.08 | ± | 20.13 | 1429.24 | ± | 28.66 | 1537.00 | ± | 21.77 |

| Cu (ppm) | 1.26 | ± | 0.04 | 2.09 | ± | 0.14 | 1.30 | ± | 0.16 |

| Fe (ppm) | 136.92 | ± | 6.15 | 147.52 | ± | 7.51 | 143.48 | ± | 5.07 |

| Mn (ppm) | 32.72 | ± | 1.61 | 68.32 | ± | 5.74 | 61.36 | ± | 2.15 |

| Zn (ppm) | 3.63 | ± | 0.19 | 1.99 | ± | 0.22 | 2.11 | ± | 0.14 |

| Nutrient | Site 1 | Site 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 1.75 | ± | 0.06 | 1.32 | ± | 0.05 |

| P (%) | 0.20 | ± | 0.01 | 0.17 | ± | 0.01 |

| K (%) | 0.53 | ± | 0.02 | 0.47 | ± | 0.02 |

| Ca (%) | 0.68 | ± | 0.05 | 1.13 | ± | 0.06 |

| Mg (%) | 0.09 | ± | 0.00 | 0.10 | ± | 0.00 |

| Na (%) | 0.02 | ± | 0.00 | 0.02 | ± | 0.00 |

| B (ppm) | 18.62 | ± | 1.23 | 15.75 | ± | 1.19 |

| Fe (ppm) | 43.67 | ± | 2.72 | 44.95 | ± | 2.85 |

| Mn (ppm) | 238.05 | ± | 30.33 | 694.79 | ± | 82.24 |

| Zn (ppm) | 45.87 | ± | 3.49 | 54.48 | ± | 3.57 |

| Nutrient | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 1.31 | ± | 0.04 | 1.17 | ± | 0.03 | 1.11 | ± | 0.03 |

| P (%) | 0.12 | ± | 0.01 | 0.13 | ± | 0.01 | 0.13 | ± | 0.01 |

| K (%) | 0.31 | ± | 0.01 | 0.44 | ± | 0.02 | 0.44 | ± | 0.01 |

| Ca (%) | 0.74 | ± | 0.05 | 1.00 | ± | 0.05 | 1.08 | ± | 0.03 |

| Mg (%) | 0.07 | ± | 0.01 | 0.08 | ± | 0.01 | 0.10 | ± | 0.01 |

| B (ppm) | 14.62 | ± | 0.85 | 15.76 | ± | 1.07 | 14.37 | ± | 0.68 |

| Fe (ppm) | 58.96 | ± | 3.70 | 127.50 | ± | 26.8 | 37.48 | ± | 7.10 |

| Mn (ppm) | 283.2 | ± | 31.64 | 666.91 | ± | 70.03 | 602.00 | ± | 45.50 |

| Zn (ppm) | 44.89 | ± | 3.37 | 48.40 | ± | 3.08 | 41.36 | ± | 2.84 |

| Nutrient | Autumn 2021 | Spring 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | < 5 year | >5 year | Overall | < 5 year | > 5 year | |||

| N | -0.13 | -0.28 | 0.23 | 0.02 | -0.08 | 0.02 | ||

| P | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.11 | -0.10 | -0.09 | -0.14 | ||

| K | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.20 | -0.26 | -0.13 | -0.35 | ||

| Ca | 0.01 | -0.21 | 0.26 | 0.12 | -0.12 | 0.26 | ||

| Mg | 0.00 | -0.15 | 0.21 | 0.06 | -0.11 | 0.19 | ||

| Na | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.19 | ||

| S | -0.16 | 0.20 | -0.49 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||

| Al | -0.14 | 0.02 | -0.28 | -0.11 | -0.04 | -0.15 | ||

| Cu | -0.13 | 0.24 | -0.20 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.03 | ||

| Fe | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.01 | ||

| Mn | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.02 | ||

| Zn | 0.04 | -0.20 | 0.14 | -0.07 | -0.03 | -0.26 | ||

| Nutrient | Autumn 2021 | Spring 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | < 5 year | > 5 year | Overall | < 5 year | > 5 year | |||

| N | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.67 | ||

| P | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.36 | ||

| K | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.13 | ||

| Ca | -0.04 | -0.09 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.24 | ||

| Mg | -0.04 | -0.31 | 0.29 | -0.11 | 0.00 | -0.15 | ||

| Na | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.32 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| B | 0.08 | -0.03 | 0.17 | -0.08 | -0.47 | 0.03 | ||

| Fe | -0.07 | -0.03 | -0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ||

| Mn | -0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.23 | ||

| Zn | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).