Submitted:

19 March 2024

Posted:

20 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and DNA Extraction

2.2. SSR Genotyping and Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Allelic Diversity and Marker Informativeness

3.3. Genetic Variability

3.4. Distinct Subgroup Identification through Population Structure

3.5. Genetic Relatedness and Diversity Assessment

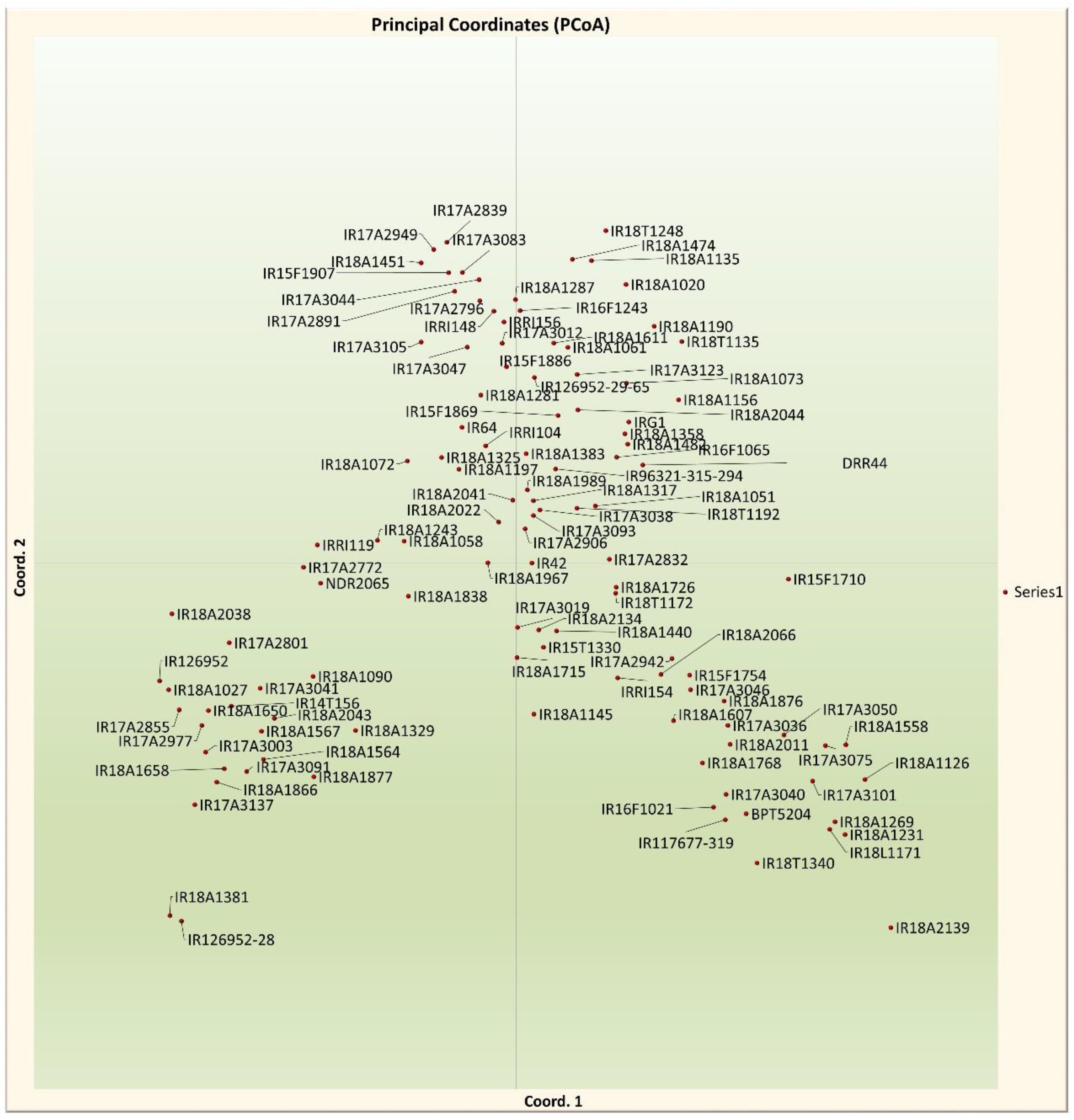

3.6. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)

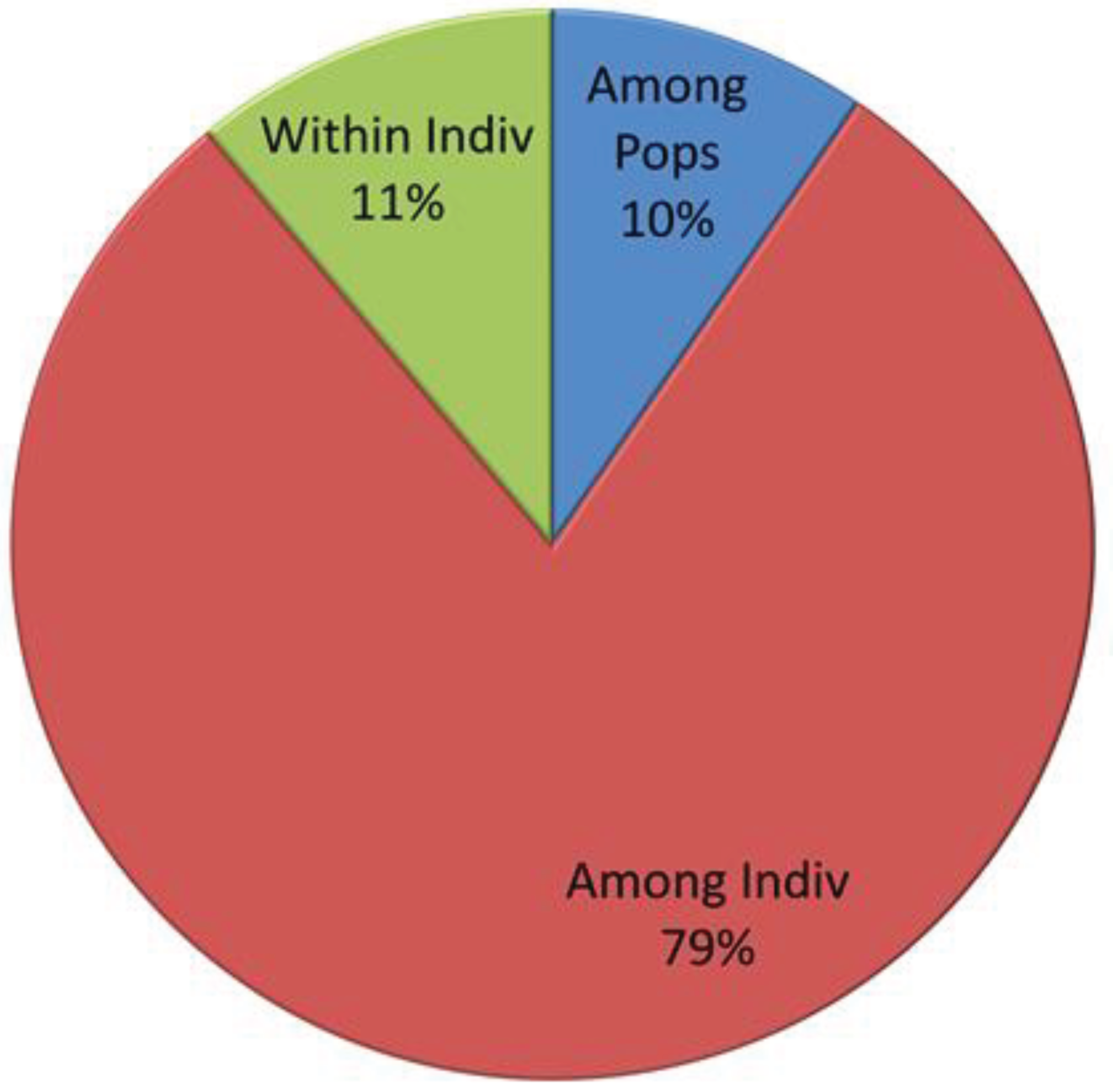

3.7. Genetic Differentiation Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasheed, A.; Fahad, S.; Hassan, M.; Tahir, M.; Aamer, M.; Wu, Z. A REVIEW ON ALUMINUM TOXICITY AND QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCI MAPPING IN RICE (ORYZA SATIVA L). Applied Ecology & Environmental Research 2020, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.; Fahad, S.; Aamer, M.; Hassan, M.; Tahir, M.; Wu, Z. Role of genetic factors in regulating cadmium uptake, transport and accumulation mechanisms and quantitative trait loci mapping in rice. a review. Applied Ecology & Environmental Research 2020, 18. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. WORLD FOOD AND AGRICULTURE STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2022; FAO: 2022.

- Collard, B.C.; Gregorio, G.B.; Thomson, M.J.; Islam, R.; Vergara, G.V.; Laborte, A.G.; Nissila, E.; Kretzschmar, T.; Cobb, J.N. Transforming rice breeding: re-designing the irrigated breeding pipeline at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Crop breeding, genetics and genomics 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lamaoui, M.; Jemo, M.; Datla, R.; Bekkaoui, F. Heat and drought stresses in crops and approaches for their mitigation. Frontiers in chemistry 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Mackill, D.J. A major locus for submergence tolerance mapped on rice chromosome 9. Molecular Breeding 1996, 2, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Subudhi, P.; Senadhira, D.; Manigbas, N.; Sen-Mandi, S.; Huang, N. Mapping QTLs for submergence tolerance in rice by AFLP analysis and selective genotyping. Molecular and General Genetics MGG 1997, 255, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siangliw, M.; Toojinda, T.; Tragoonrung, S.; Vanavichit, A. Thai jasmine rice carrying QTLch9 (Sub QTL) is submergence tolerant. Annals of Botany 2003, 91, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toojinda, T.; Siangliw, M.; Tragoonrung, S.; Vanavichit, A. Molecular genetics of submergence tolerance in rice: QTL analysis of key traits. Annals of Botany 2003, 91, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septiningsih, E.M.; Collard, B.C.; Heuer, S.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Ismail, A.M.; Mackill, D.J. Applying genomics tools for breeding submergence tolerance in rice. Translational genomics for crop breeding: abiotic stress, yield and quality 2013, 2, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, Z.J.C.; Carandang, J.; Sanchez, D.L.; Mackill, D.J.; Septiningsih, E.M. Mapping additional QTLs from FR13A to increase submergence tolerance in rice beyond SUB1. Euphytica 2016, 209, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Mao, H.; Shao, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhang, Q. A G-protein pathway determines grain size in rice. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthi, B.K.; Naravaneni, R. SSR marker based DNA fingerprinting and diversity study in rice (Oryza sativa. L). African Journal of Biotechnology 2006, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.; Morgante, M.; Andre, C.; Hanafey, M.; Vogel, J.; Tingey, S.; Rafalski, A. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR (microsatellite) markers for germplasm analysis. Molecular breeding 1996, 2, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, L.; Noorani, A.; Pagnotta, M.A. Assessing plant genetic diversity by molecular tools. Diversity 2009, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCouch, S.R.; Chen, X.; Panaud, O.; Temnykh, S.; Xu, Y.; Cho, Y.G.; Huang, N.; Ishii, T.; Blair, M. Microsatellite marker development, mapping and applications in rice genetics and breeding. Oryza: from molecule to plant 1997, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebana, K.; Kojima, Y.; Fukuoka, S.; Nagamine, T.; Kawase, M. Development of mini core collection of Japanese rice landrace. Breeding Science 2008, 58, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Lu, Y.; Xiao, P.; Sun, M.; Corke, H.; Bao, J. Genetic diversity and population structure of a diverse set of rice germplasm for association mapping. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2010, 121, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrama, H.A.; Yan, W.; Jia, M.; Fjellstrom, R.; McClung, A.M. Genetic structure associated with diversity and geographic distribution in the USDA rice world collection. Natural Science 2010, 2, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Y. Population structure and genetic diversity in a rice core collection (Oryza sativa L.) investigated with SSR markers. PloS one 2011, 6, e27565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakat Ali, M.; McClung, A.M.; Jia, M.H.; Kimball, J.A.; McCouch, S.R.; Eizenga, G.C. A rice diversity panel evaluated for genetic and agro-morphological diversity between subpopulations and its geographic distribution. Crop Science 2011, 51, 2021–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachimuthu, V.V.; Muthurajan, R.; Duraialaguraja, S.; Sivakami, R.; Pandian, B.A.; Ponniah, G.; Gunasekaran, K.; Swaminathan, M.; KK, S.; Sabariappan, R. Analysis of population structure and genetic diversity in rice germplasm using SSR markers: an initiative towards association mapping of agronomic traits in Oryza sativa. Rice 2015, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrama, H.; Yan, W.; Fjellstrom, R.; Jia, M.; McClung, A. Genetic Diversity and Relationships Assessed by SSRs in the USDA World-Wide Rice Germplasm Collection. In Proceedings of 2008 Joint Annual Meeting (5-9 Oct. 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.; Sengupta, S.; Parida, S.K.; Roy, B.; Ghosh, M.; Prasad, M.; Ghose, T.K. Genetic diversity and population structure of rice landraces from Eastern and North Eastern States of India. BMC genetics 2013, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, B.; Khan, M.L.; Dayanandan, S. Genetic structure and diversity of indigenous rice (Oryza sativa) varieties in the Eastern Himalayan region of Northeast India. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sow, M.; Ndjiondjop, M.-N.; Sido, A.; Mariac, C.; Laing, M.; Bezançon, G. Genetic diversity, population structure and differentiation of rice species from Niger and their potential for rice genetic resources conservation and enhancement. Genetic resources and crop evolution 2014, 61, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, T.; Yao, S.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Nadaf, A.B.; Liang, W.; Lu, K. Genetic dissection of eating and cooking qualities in different subpopulations of cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) through association mapping. BMC genetics 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, B.; Frouin, J.; Greco, R.; Bruschi, G.; Droc, G.; Hamelin, C.; Ruiz, M.; Clément, G.; Evrard, J.C.; Van Coppenole, S. Genetic diversity and population structure in a European collection of rice. Crop science 2012, 52, 1663–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1980, 8, 4321–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S.V. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, X.J.-C., J. DARwin software, 2006.

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, D.A.; Vonholdt, B. Structure Harvester: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genetics Resources 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Laval, G.; Schneider, S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online 2007, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.V.; Shelar, A.; Rai, M.; Laux, P.; Thakur, M.; Dosnkyi, I.; Santomauro, G.; Singh, A.K.; Luch, A.; Patil, R.; Bill, J. Harmonization Risks and Rewards: Nano-QSAR for Agricultural Nanomaterials. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2024, 72, 2835–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.V.; Varma, M.; Rai, M.; Pratap Singh, S.; Bansod, G.; Laux, P.; Luch, A. Advancing Predictive Risk Assessment of Chemicals via Integrating Machine Learning, Computational Modeling, and Chemical/Nano-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Approaches. Advanced Intelligent Systems n/a 2300366. [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Kumar, D.; Babu, B.K. Analysis of genetic divergence and population structure through microsatellite markers in normal and quality protein maize genotypes from NW Himalayan region of India. Vegetos 2020, 33, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Kumar, D.; Singh, A.; Dixit, S.; Khan, N.A.; Kumar, A. Genetic variability, character association and path coefficient analysis in rice (Oryza sativa) genotypes of semi-arid region of India. The Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2023, 93, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarup, S.; Cargill, E.J.; Crosby, K.; Flagel, L.; Kniskern, J.; Glenn, K.C. Genetic diversity is indispensable for plant breeding to improve crops. Crop Science 2021, 61, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, P.; Khaire, A.R.; Korada, M.; Singh, D.K.; Majhi, P.K.; Jayasudha, S. Genetic Variability, Character Association and Path Analysis for Yield and its Related Traits in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotypes. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2021, 33, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswajit, P.; Sritama, K.; Anindya, S.; Moushree, S.; Sabyasachi, K. Breeding for submergence tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and its management for flash flood in rainfed low land area: A review. Agricultural Reviews 2017, 38, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Chabane, K.; Hendre, P.S.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Graner, A. Comparative assessment of EST-SSR, EST-SNP and AFLP markers for evaluation of genetic diversity and conservation of genetic resources using wild, cultivated and elite barleys. Plant Science 2007, 173, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.G.; Thiruvengadam, V.; Vinod, K.K. Genetic diversity among cultivars, landraces and wild relatives of rice as revealed by microsatellite markers. Journal of Applied Genetics 2007, 48, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; He, H.; Zou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, R.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.-M.; Xu, J.-L.; Fan, L.-M. , et al. Development and application of a set of breeder-friendly SNP markers for genetic analyses and molecular breeding of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2011, 123, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrama, H.; Eizenga, G. Molecular diversity and genome-wide linkage disequilibrium patterns in a worldwide collection of Oryza sativa and its wild relatives. Euphytica 2008, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Colowit, P.; Mackill, D. Evaluation of Genetic Diversity in Rice Subspecies Using Microsatellite Markers. Crop Science 2002, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrama, H.; Eizenga, G.; Yan, W. Association mapping of yield and its components in rice cultivars. Molecular Breeding 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Ding, L.; Tang, S.; Qiu, Z.E.; Cao, Y. , et al. Genetic structure and diversity of Oryza sativa L. in Guizhou, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 2007, 52, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wright, M.; Kimball, J.; Eizenga, G.; McClung, A.; Kovach, M.; Tyagi, W.; Ali, M.L.; Tung, C.W.; Reynolds, A. , et al. Genomic diversity and introgression in O. sativa reveal the impact of domestication and breeding on the rice genome. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, F.; Wei, X.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Genetic structure and differentiation of Oryza sativa L. in China revealed by microsatellites. Theor Appl Genet 2009, 119, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, A.L.; Williamson, S.H.; Hernandez, R.D.; Boyko, A.; Fledel-Alon, A.; York, T.L.; Polato, N.R.; Olsen, K.M.; Nielsen, R.; McCouch, S.R. , et al. Genome-wide patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in domesticated rice. PLoS Genet 2007, 3, 1745–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Ding, L.; Wang, F.; Li, Z. Assessing indica-japonica differentiation of improved rice varieties using microsatellite markers. J Genet Genomics 2009, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breseghello, F.; Sorrells, M.E. Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genetics 2006, 172, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Marker | Chromosome no. | SSR Motif | Mini. Mol. weight | Maxi. Mol weight | Number of alleles | Heterozygosity | Gene diversity | PIC Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM 495 | 1 | (CTG)7 | 160 | 180 | 3 | 0.494 | 0.497 | 0.722 |

| RM 283 | 1 | (GA)18 | 150 | 170 | 3 | 0.138 | 0.139 | 0.566 |

| RM 24 | 1 | (GA)29 | 130 | 180 | 6 | 0.811 | 0.815 | 0.969 |

| RM 5 | 1 | (GA)14 | 100 | 140 | 5 | 0.674 | 0.677 | 0.870 |

| HVSSR01-70 | 1 | (GATA)67 | 270 | 300 | 3 | 0.500 | 0.502 | 0.803 |

| RM 3520 | 1 | (CT)31 | 160 | 180 | 5 | 0.540 | 0.543 | 0.763 |

| RM 12329 | 2 | (GA)15 | 240 | 270 | 4 | 0.694 | 0.698 | 0.908 |

| RM 154 | 2 | (GA)21 | 140 | 210 | 8 | 0.819 | 0.823 | 0.925 |

| RM 110 | 2 | (GA)15 | 140 | 200 | 7 | 0.754 | 0.758 | 0.924 |

| RM 12705 | 2 | (TCAC)6 | 180 | 190 | 3 | 0.583 | 0.585 | 0.815 |

| RM 452 | 2 | (GTC)9 | 190 | 210 | 3 | 0.253 | 0.254 | 0.623 |

| RM2634 | 2 | (AT)31 | 150 | 160 | 3 | 0.584 | 0.586 | 0.830 |

| RM 138 | 2 | (GT)14 | 230 | 280 | 6 | 0.518 | 0.520 | 0.836 |

| RM 489 | 3 | (ATA)8 | 230 | 250 | 3 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.860 |

| RM 3716 | 3 | (AG)17 | 120 | 130 | 3 | 0.437 | 0.439 | 0.983 |

| OSR13 | 3 | (GA)n | 90 | 130 | 3 | 0.338 | 0.340 | 0.701 |

| RM 3646 | 3 | (GA)14 | 130 | 150 | 3 | 0.383 | 0.384 | 0.734 |

| RM 422 | 3 | (AG)30 | 380 | 390 | 2 | 0.393 | 0.395 | 0.729 |

| RM 307 | 4 | (AT)14(GT)21 | 120 | 200 | 3 | 0.339 | 0.341 | 0.740 |

| RM 7200 | 4 | (ATAG)8 | 150 | 270 | 8 | 0.868 | 0.872 | 0.980 |

| RGNMS3228 | 4 | (AT)42 | 350 | 360 | 3 | 0.405 | 0.407 | 0.984 |

| RM 241 | 4 | (CT)31 | 100 | 180 | 4 | 0.582 | 0.585 | 0.845 |

| RM 124 | 4 | (TC)10 | 260 | 290 | 3 | 0.323 | 0.325 | 0.959 |

| RM 122 | 5 | (GA)7A(GA)2A(GA)11 | 220 | 290 | 7 | 0.758 | 0.761 | 0.942 |

| RM 413 | 5 | (AG)11 | 80 | 100 | 3 | 0.560 | 0.563 | 0.925 |

| RM 18107 | 5 | (GA)33 | 290 | 300 | 2 | 0.436 | 0.438 | 0.755 |

| RM 5705 | 5 | (AAT)21 | 200 | 220 | 3 | 0.624 | 0.626 | 0.828 |

| HVSSR05-41 | 5 | (AT)58 | 290 | 310 | 3 | 0.400 | 0.402 | 0.799 |

| RM 161 | 5 | (AG)20 | 180 | 210 | 3 | 0.075 | 0.076 | 0.507 |

| RM 26 | 5 | (GA)15 | 110 | 130 | 0.620 | 0.623 | 0.694 | |

| RM 18842 | 5 | (TA)25 | 130 | 160 | 3 | 0.482 | 0.485 | 0.776 |

| RM 31 | 5 | (GA)15 | 150 | 190 | 6 | 0.482 | 0.485 | 0.846 |

| RM 510 | 6 | (GA)15 | 120 | 130 | 2 | 0.454 | 0.456 | 0.515 |

| RM 121 | 6 | (CT)7 | 160 | 170 | 2 | 0.224 | 0.225 | 0.640 |

| RM 6818 | 6 | (TCT)9 | 120 | 140 | 3 | 0.430 | 0.432 | 0.718 |

| RM 162 | 6 | (AC)20 | 210 | 1000 | 5 | 0.167 | 0.168 | 0.495 |

| RM 427 | 7 | (TG)11 | 180 | 190 | 2 | 0.334 | 0.336 | 0.701 |

| RM 11 | 7 | (GA)17 | 100 | 160 | 5 | 0.569 | 0.572 | 0.816 |

| RM 7 | 7 | (GA)19 | 170 | 190 | 2 | 0.238 | 0.239 | 0.684 |

| RM 455 | 7 | (TTCT)5 | 130 | 150 | 3 | 0.277 | 0.278 | 0.649 |

| RM118 | 7 | (GA)8 | 180 | 200 | 2 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.035 |

| RM 125 | 7 | (GCT)8 | 100 | 800 | 7 | 0.413 | 0.415 | 0.682 |

| RM 408 | 8 | (CT)13 | 120 | 130 | 2 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.517 |

| RM 25 | 8 | (GA)18 | 140 | 170 | 4 | 0.486 | 0.488 | 0.719 |

| RM 284 | 8 | (GA)8 | 150 | 160 | 2 | 0.176 | 0.177 | 0.600 |

| RM 433 | 8 | (AG)13 | 120 | 130 | 2 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.663 |

| RM 447 | 8 | (CTT)8 | 110 | 190 | 4 | 0.278 | 0.279 | 0.710 |

| RM 23657 | 9 | (GCC)7 | 260 | 280 | 3 | 0.216 | 0.217 | 0.690 |

| RGNMS3189 | 9 | (TCT)8 | 350 | 360 | 2 | 0.423 | 0.425 | 0.771 |

| RM 444 | 9 | (AT)12 | 110 | 240 | 6 | 0.691 | 0.694 | 0.909 |

| RM 105 | 9 | (CCT)6 | 100 | 160 | 4 | 0.406 | 0.408 | 0.703 |

| RM 271 | 10 | (GA)15 | 90 | 120 | 3 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.564 |

| RM 269 | 10 | (GA)17 | 100 | 130 | 4 | 0.620 | 0.623 | 0.834 |

| RM 26146 | 11 | (AGG)7 | 230 | 240 | 3 | 0.251 | 0.252 | 0.581 |

| RM 1124 | 11 | (AG)12 | 170 | 190 | 3 | 0.130 | 0.131 | 0.656 |

| RM 552 | 11 | (TAT)13 | 180 | 250 | 6 | 0.291 | 0.292 | 0.692 |

| RM 536 | 11 | (CT)16 | 210 | 230 | 3 | 0.434 | 0.436 | 0.709 |

| RM26657 | 11 | (AAAT)5 | 290 | 300 | 3 | 0.603 | 0.606 | 0.846 |

| RM7654 | 11 | (TTTC)9 | 190 | 200 | 3 | 0.550 | 0.553 | 0.800 |

| RM 415 | 12 | (AT)21 | 220 | 230 | 2 | 0.175 | 0.176 | 0.678 |

| RM101 | 12 | (CT)37 | 320 | 330 | 3 | 0.564 | 0.567 | 0.817 |

| RM277 | 12 | (GA)11 | 120 | 130 | 2 | 0.480 | 0.483 | 0.648 |

| HVSSR12-43 | 12 | (TA)62 | 340 | 350 | 2 | 0.655 | 0.658 | 0.734 |

| HVSSR12-44 | 12 | (TA)63 | 330 | 340 | 2 | 0.227 | 0.228 | 0.871 |

| Characters | Mean | Range | Var (g) | Var (p) | GCV (%) | PCV (%) | ECV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFF | 107.65 | 86.60- 125.27 | 93.72 | 95.03 | 8.99 | 9.06 | 1.32 |

| SV | 32.33 | 17.41-56.75 | 70.32 | 75.97 | 25.96 | 26.98 | 5.65 |

| PH (cm) | 118.51 | 71.80-171.80 | 225.48 | 226.44 | 12.67 | 12.70 | 0.97 |

| PL | 113.96 | 52.21-179.08 | 554.43 | 615.66 | 20.65 | 21.76 | 61.23 |

| SPP | 93.84 | 0.00-165.21 | 54.39 | 71.64 | 8.66 | 9.93 | 17.25 |

| BYP | 28.50 | 14.61-48.50 | 28.91 | 31.94 | 18.86 | 19.82 | 3.03 |

| HI | 22.32 | 16.43-35.03 | 6.94 | 9.29 | 11.81 | 13.66 | 2.35 |

| G. No. | Genotypes | Inferred ancestry | Structure group | ||

| Q1 Q2 Q3 | |||||

| RG1 | IRG1 | 0.004 | 0.301 | 0.695 | AD |

| RG2 | DRR44 | 0.004 | 0.695 | 0.3 | AD |

| RG3 | IR18A2044 | 0.006 | 0.362 | 0.631 | AD |

| RG4 | IR17A2832 | 0.025 | 0.704 | 0.272 | AD |

| RG5 | IR18T1172 | 0.02 | 0.595 | 0.386 | AD |

| RG6 | BPT5204 | 0.01 | 0.964 | 0.026 | SG2 |

| RG7 | IR15F1710 | 0.004 | 0.607 | 0.389 | AD |

| RG8 | IR18A1231 | 0.006 | 0.981 | 0.012 | SG2 |

| RG9 | IR18A2011 | 0.028 | 0.887 | 0.085 | SG2 |

| RG10 | IR17A3040 | 0.053 | 0.917 | 0.03 | SG2 |

| RG11 | IR18T1340 | 0.003 | 0.993 | 0.003 | SG2 |

| RG12 | IR17A3075 | 0.004 | 0.986 | 0.011 | SG2 |

| RG13 | IR17A3101 | 0.005 | 0.991 | 0.004 | SG2 |

| RG14 | IR18A1269 | 0.003 | 0.992 | 0.006 | SG2 |

| RG15 | IR17A3046 | 0.015 | 0.975 | 0.01 | SG2 |

| RG16 | IR17A3050 | 0.005 | 0.99 | 0.005 | SG2 |

| RG17 | IR18A1126 | 0.002 | 0.994 | 0.003 | SG2 |

| RG18 | IR18A2139 | 0.003 | 0.995 | 0.002 | SG2 |

| RG19 | IR117677-31 | 0.015 | 0.978 | 0.006 | SG2 |

| RG20 | IR18A1558 | 0.004 | 0.974 | 0.021 | SG2 |

| RG21 | IR18L1171 | 0.003 | 0.995 | 0.003 | SG2 |

| RG22 | IR18A1768 | 0.014 | 0.865 | 0.122 | SG2 |

| RG23 | IR16F1021 | 0.008 | 0.988 | 0.003 | SG2 |

| RG24 | IR17A3036 | 0.015 | 0.977 | 0.007 | SG2 |

| RG25 | IR15F1754 | 0.114 | 0.867 | 0.019 | SG2 |

| RG26 | IR17A2942 | 0.031 | 0.964 | 0.005 | SG2 |

| RG27 | IR18A1876 | 0.007 | 0.985 | 0.008 | SG2 |

| RG28 | IR18A1607 | 0.006 | 0.986 | 0.008 | SG2 |

| RG29 | IR18A2066 | 0.006 | 0.975 | 0.019 | SG2 |

| RG30 | IR18A1726 | 0.027 | 0.927 | 0.046 | SG2 |

| RG31 | IR18A1440 | 0.023 | 0.969 | 0.008 | SG2 |

| RG32 | IR18A1715 | 0.168 | 0.805 | 0.027 | SG2 |

| RG33 | IRRI154 | 0.018 | 0.964 | 0.018 | SG2 |

| RG34 | IR42 | 0.044 | 0.95 | 0.006 | SG2 |

| RG35 | IR18A1051 | 0.024 | 0.915 | 0.061 | SG2 |

| RG36 | IR17A2906 | 0.119 | 0.835 | 0.046 | SG2 |

| RG37 | IR17A3038 | 0.096 | 0.837 | 0.068 | SG2 |

| RG38 | IR17A3019 | 0.089 | 0.896 | 0.016 | SG2 |

| RG39 | IR18A2022 | 0.165 | 0.634 | 0.2 | AD |

| RG40 | IR96321-315 | 0.035 | 0.697 | 0.267 | AD |

| RG41 | IR17A3093 | 0.118 | 0.171 | 0.711 | AD |

| RG42 | IR18A2134 | 0.275 | 0.627 | 0.098 | AD |

| RG43 | IR18A1058 | 0.382 | 0.545 | 0.073 | AD |

| RG44 | IR18A1145 | 0.604 | 0.198 | 0.197 | AD |

| RG45 | IR15T1330 | 0.257 | 0.45 | 0.292 | AD |

| RG46 | IR18A2041 | 0.287 | 0.265 | 0.448 | AD |

| RG47 | IR18A1989 | 0.178 | 0.012 | 0.811 | SG3 |

| RG48 | IR18A1072 | 0.285 | 0.012 | 0.704 | AD |

| RG49 | IR18A1243 | 0.394 | 0.187 | 0.419 | AD |

| RG50 | IR17A2796 | 0.01 | 0.123 | 0.867 | SG3 |

| RG51 | IR126952-29 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.96 | SG3 |

| RG52 | IR17A3047 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.974 | SG3 |

| RG53 | IR15F1907 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.993 | SG3 |

| RG54 | IR17A2891 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.99 | SG3 |

| RG55 | IR18A1451 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.992 | SG3 |

| RG56 | IR17A3083 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.989 | SG3 |

| RG57 | IR17A2839 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.988 | SG3 |

| RG58 | IR17A3123 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.988 | SG3 |

| RG59 | IR18A1474 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.993 | SG3 |

| RG60 | IR18A1020 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.994 | SG3 |

| RG61 | IR18A1190 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.991 | SG3 |

| RG62 | IR18T1248 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.994 | SG3 |

| RG63 | IR18T1135 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.974 | SG3 |

| RG64 | IR18A1358 | 0.077 | 0.027 | 0.896 | SG3 |

| RG65 | IR16F1243 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.991 | SG3 |

| RG66 | IR18A1061 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.993 | SG3 |

| RG67 | IR18A1135 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.992 | SG3 |

| RG68 | IR18A1287 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.99 | SG3 |

| RG69 | IR18A1482 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.94 | SG3 |

| RG70 | IR18A1611 | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.964 | SG3 |

| RG71 | IR18A1383 | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.944 | SG3 |

| RG72 | IR17A2949 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.99 | SG3 |

| RG73 | IR17A3012 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.983 | SG3 |

| RG74 | IRRI148 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.987 | SG3 |

| RG75 | IRRI156 | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.957 | SG3 |

| RG76 | IR18T1192 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.982 | SG3 |

| RG77 | IR18A1197 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.983 | SG3 |

| RG78 | IR18A1325 | 0.02 | 0.005 | 0.976 | SG3 |

| RG79 | IRRI104 | 0.106 | 0.103 | 0.791 | AD |

| RG80 | IR18A1317 | 0.014 | 0.095 | 0.89 | SG3 |

| RG81 | IR17A3105 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.989 | SG3 |

| RG82 | IR17A3044 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.992 | SG3 |

| RG83 | IR64 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.928 | SG3 |

| RG84 | IR15F1869 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.981 | SG3 |

| RG85 | IR15F1886 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.984 | SG3 |

| RG86 | IR18A1281 | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.972 | SG3 |

| RG87 | IR18A1073 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.986 | SG3 |

| RG88 | IR18A1156 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.991 | SG3 |

| RG89 | IR16F1065 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.983 | SG3 |

| RG90 | IR18A1967 | 0.441 | 0.009 | 0.549 | AD |

| RG91 | IR18A1329 | 0.945 | 0.006 | 0.049 | SG1 |

| RG92 | IR17A3041 | 0.984 | 0.004 | 0.012 | SG1 |

| RG93 | IR18A1650 | 0.983 | 0.01 | 0.007 | SG1 |

| RG94 | IR17A2772 | 0.78 | 0.026 | 0.195 | AD |

| RG95 | IR17A3091 | 0.978 | 0.006 | 0.016 | SG1 |

| RG96 | IR17A2801 | 0.959 | 0.005 | 0.036 | SG1 |

| RG97 | IR17A2855 | 0.99 | 0.004 | 0.006 | SG1 |

| RG98 | IR18A1027 | 0.994 | 0.003 | 0.003 | SG1 |

| RG99 | IR18A2038 | 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.007 | SG1 |

| RG100 | IR18A1658 | 0.99 | 0.005 | 0.005 | SG1 |

| RG101 | IR17A3137 | 0.995 | 0.002 | 0.003 | SG1 |

| RG102 | IR18A1877 | 0.985 | 0.01 | 0.005 | SG1 |

| RG103 | IR17A2977 | 0.993 | 0.003 | 0.004 | SG1 |

| RG104 | IR18A1866 | 0.993 | 0.003 | 0.004 | SG1 |

| RG105 | IR18A1567 | 0.989 | 0.007 | 0.004 | SG1 |

| RG106 | IR18A1090 | 0.972 | 0.015 | 0.012 | SG1 |

| RG107 | IR18A2043 | 0.99 | 0.006 | 0.004 | SG1 |

| RG108 | IR18A1838 | 0.955 | 0.02 | 0.024 | SG1 |

| RG109 | NDR2065 | 0.788 | 0.023 | 0.19 | SG1 |

| RG110 | IRRI119 | 0.756 | 0.036 | 0.208 | AD |

| RG111 | IR14T156 | 0.99 | 0.004 | 0.006 | AD |

| RG112 | IR17A3003 | 0.984 | 0.005 | 0.011 | SG1 |

| RG113 | IR126952:17 | 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.007 | SG1 |

| RG114 | IR18A1564 | 0.953 | 0.01 | 0.036 | SG1 |

| RG115 | IR126952-28 | 0.985 | 0.008 | 0.007 | SG1 |

| RG116 | IR18A1381 | 0.988 | 0.004 | 0.009 | SG1 |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among the Population | 3 | 351.793 | 117.264 | 1.575 | 10% |

| Among Individuals | 112 | 3137.005 | 28.009 | 13.099 | 79% |

| Within Individuals | 116 | 210.000 | 1.810 | 1.810 | 11% |

| Total | 231 | 3698.797 | 16.484 | 100% | |

| F-Statistics | Value | P(rand >= data) | |||

| Fst | 0.096 | 0.001 | |||

| Fis | 0.879 | 0.001 | |||

| Fit | 0.890 | 0.001 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).