Introduction

Infectious diseases have emerged at an increased rate over the last decades due to biodiversity loss and climate change (Pfenning-Butterworth et al., 2024). They constitute a major threat to wild animal and human populations but their impacts are hard to predict (Jones et al., 2008). One fundamental challenge when examining the dynamics of disease outbreaks is understanding how host movements influence the spatial spread of diseases within and among populations (Dougherty et al., 2018), but also reversely, how diseases affect host movements, by changing the behaviour of individuals (Romano et al., 2020; Stockmaier et al., 2021).

Host social behaviour is an important factor affecting individual infection susceptibility and disease spread (Nunn et al., 2008; Stockmaier et al., 2021). Disease transmission rates are more likely to increase in group-living individuals compared to solitary individuals (Caillaud et al., 2006; Langwig et al., 2012). Within social groups, individuals with high social status (Höner et al., 2012), good body condition (Dekelaita et al., 2023), lower parasite load (Gaitan & Millien, 2016) and more likely to disperse (Loveridge & Macdonald, 2001) can facilitate disease spread. Yet, those individuals are not always the ones which are more likely to die from the disease. For example, dominant female spotted hyenas Crocuta crocuta are more likely to spread the pathogenic bacterium Streptococcus equi ruminatorum to other individuals but they are less likely to die from the pathogen than yearlings and adult males, which have a lower social status and lower body condition (Höner et al., 2012). Those individual and social differences in disease susceptibility induce non-random mortalities within groups which have strong impacts on social group size and structure (Caillaud et al., 2006). It can relax density-dependence mechanisms which can in turn result in major demographic changes, such as rearrangements of dispersal flows (Genton et al., 2015; Lachish et al., 2011; Nunn et al., 2008) or an increase of recruitment rates (Muths et al., 2011). At the same time, changes in social behaviour can arise from an active response of individuals to disease exposure: individuals can self-isolate, avoid contacts or exclude infectious individuals from the social groups and this can in turn affect reproductive activities and social cohesion within groups and individual movements between groups (Lopes et al., 2016; Stockmaier et al., 2021). For example, silverback male gorillas Gorilla gorilla gorilla were more likely to become solitary and female gorillas tended to disperse more from breeding groups towards non-breeding groups during an Ebola outbreak, weakening social cohesion and altering dispersal patterns between groups (Genton et al., 2015). Landscape structure may also play an important role on disease spread, as it directly enhances or impedes host movements within and between habitat patches (Tracey et al., 2014; Watts et al., 2018).

Non-human primates (hereafter primates), are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases, because the majority of species live in social groups with high frequency of social interactions, which facilitate pathogen transmission between individuals and groups (Bermejo et al., 2006; Berthet et al., 2021; Bicca-Marques & de Freitas, 2010; Leendertz et al., 2004; Morrison et al., 2021; Walsh et al., 2003). Additionally, wild primates suffer from the loss and fragmentation of primary forests, their main habitat, and from hunting, as some of them are used as commercial bushmeat. These threats make them highly endangered worldwide, with 75% of species having declining populations (Estrada et al., 2017). Better understanding and predicting the role of disease on the dynamics of primate populations in degraded and fragmented forests is therefore urgent for their conservation (Smith et al., 2009). If the interactions between host movements and the spread of directly-transmitted pathogens have been widely studied in primates (Bermejo et al., 2006; Caillaud et al., 2006; Genton et al., 2015; Leendertz et al., 2004; Morrison et al., 2021; Walsh et al., 2003), the additional effects of landscape structure on vector-borne diseases have drawn less attention.

Yellow fever is a viral vector-borne disease endemic from the tropical regions of Africa and South America. It is transmitted to humans and primates through the bite of infected mosquitoes and represents a major public health threat despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine for humans (Sacchetto et al., 2020). In South America, yellow fever is mainly restricted to a sylvatic cycle. Arboreal mosquitoes (Haemagogus and Sabethes spp.) circulate the virus through primates which are primary hosts and can potentially amplify outbreaks (Abreu et al., 2020; Possas et al., 2018). In this specific cycle, humans are infected by mosquitoes when they enter the forest or live in rural areas near forest edges but sporadic infections can still lead to broader episodic outbreaks, as the dramatic one observed in Brazil between November 2016 and April2019 when both primates and humans were highly impacted (Giovanetti Marta et al., 2019; Possas et al., 2018).

Golden lion tamarins Leontopithecus rosalia are small, endangered and endemic primates from the highly fragmented lowland Atlantic Forest in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Their population is structured in social territorial groups generally composed of one dominant breeding couple and their subordinate offspring up to 3 years old (Dietz et al., 1997). In the 1970s, golden lion tamarins were on the verge of extinction with less than 400 remaining individuals in the wild. Massive conservation actions restored the population size to more than 3700 individuals in 2014 (Ruiz-Miranda et al., 2019). However, between 2016 and 2019, the population was hit by the worst outbreak of sylvatic yellow fever in about a century. It reduced the population size by at least 30% (Dietz et al., 2019). The lack of dead golden lion tamarins recovered for serological testing has made it difficult to assess the true impact of the outbreak, but surveys of other primate species have documented similar dramatic population reductions (Berthet et al., 2021; Possamai et al., 2022; Strier et al., 2019). A prevalence of 15% was estimated from dead primates recovered in the Brazilian state of Espirito Santo in early 2017 (Coelho Couto de Azevedo Fernandes et al., 2017).

Here, we used data from the long-term monitoring survey carried out on a population of golden lion tamarins Leontopithecus rosalia in Brazil to assess the impacts of the last yellow fever outbreak (2016-2019) on annual survival and dispersal rates at both local and regional scales of a highly fragmented forest. We predicted that the yellow fever outbreak induced a significant decrease in annual adult survival rate. As a result, the local loss of individuals would relax density-dependence and thus competition between social groups, which would lead to a decrease in dispersal rates within forests fragments and/or a shorter period to settle in a group (Lachish et al., 2011). At the same time, dispersal would constitute an active response of individuals to leave infected groups and avoid further exposure so they would disperse more within and/or between forest fragments (Genton et al., 2015; Stockmaier et al., 2021). We did not expect differences in dispersal patterns between males and females (Moraes et al., 2018; Romano et al., 2019).

Material and Methods

Study Area and Monitoring Survey

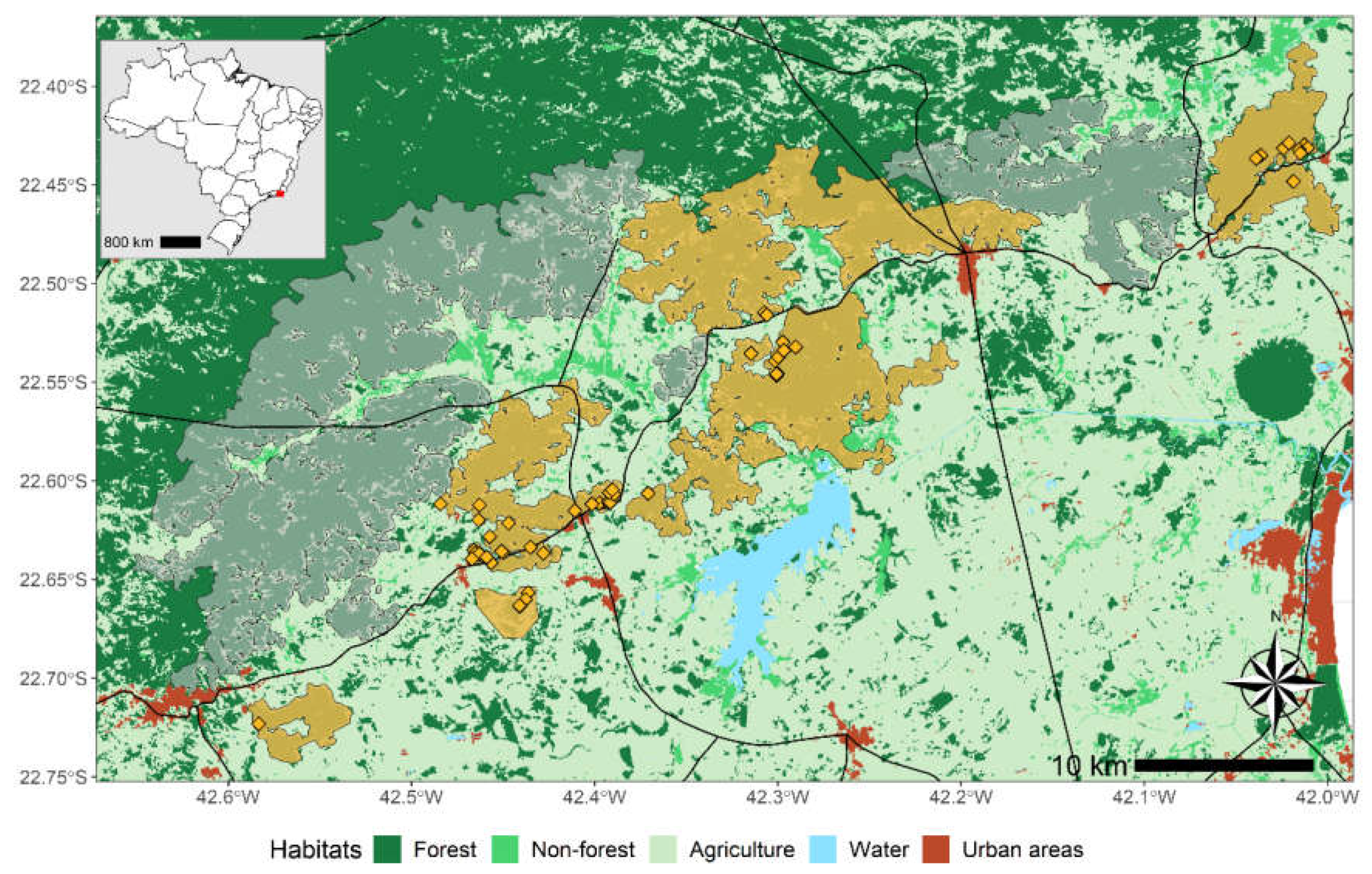

The study population lives in the highly fragmented lowland Atlantic Forest in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It has been surveyed for more than 30 years by the NGO Associação Mico-Leão-Dourado (AMLD) which is responsible for the conservation program of the species (Ruiz-Miranda et al., 2019). The area is subdivided in management units which follow contours of homogeneous forest fragments (

Figure 1) that are known to facilitate the movement of golden lion tamarins’ populations (Moraes et al., 2018; Ruiz-Miranda et al., 2019). Forest fragments have limited connectivity and some of them are separated by tertiary and major roads roads (

Figure 1).

Golden lion tamarins live in social groups of 5 individuals on average (Ruiz-Miranda et al., 2019). Females give birth to 1-2 individuals up to twice a year. After offspring reach sexual maturity (> 18 months), they either disperse outside their social group or take over a dominant breeding status when the parents die. Both sexes disperse but males rather integrate existing social groups while females tend to form new groups (Romano et al., 2019). Each group defends a territory (mean: 45 ± 16 ha) within which individuals usually move together (Dietz et al., 1997). This makes it easy to identify known or new social groups in the forest fragments and count individuals. Within most of monitored groups, one adult is equipped with a VHF transmitter to locate groups more easily in their territory. Individuals are captured at least once a year. New individuals are tattooed and all individuals have their hair dyed with unique patterns on the body for group and individual identification. When not captured, individuals are identified from group location and hair dye patterns.

Data Selection

Since 1989, between 4 and 109 groups have been monitored annually . The observation effort within and between management units and social groups has been highly variable. Observation data are therefore highly spatially and temporally heterogeneous (

Supplemental material figure S1). To correct for this bias, data were retained only after 2009, when monitoring effort became more regular. Additionally, observations of social groups ranged from 1 to 7 times per year, creating a within-year temporal heterogeneity in available data. Capture-recapture models require regular time periods between occasions, so observations were summarized as single yearly occasions. When individuals were observed in different groups during the same year, the group retained corresponded to the group where they were most often seen. If they were seen the same number of times, the group of last observation of the year was retained. Only sexually mature adults (>18 months old, Romano et al., 2019) with verified sex were included. Observations of 42 translocated individuals were included (see Kierulff et al., 2012 for translocation details) but the year of translocation, the name of their social group was unchanged. The final dataset included 234 males and 172 females living in 71 distinct social groups, representing a total of 1689 observations over 13 yearly occasions, from 2010 to 2022 (

Supplemental material figure S2).

Capture-Recapture Analysis

To concurrently estimate annual survival and dispersal probabilities, we used a multi-state capture-recapture model (Lagrange et al., 2014). Three states were defined based on the previous and current social group and forest fragment the individuals were observed, i.e., state 1: living in focal group, state 2: living in another group within the same forest fragment as previous year, state 3: living in another group in a different forest fragment than previous year. Observation data were coded as follow. All first observations of individuals were coded 1. If individuals dispersed to another group in the same forest fragment compared to the previous occasion, it was coded 2 (local dispersal). If they dispersed to another group in a different forest fragment, it was coded 3 (regional dispersal). If individuals were re-observed in the same group the year following dispersal, the new group became their focal group and their state became 1 again. If they kept changing groups for consecutive years, they remained in state 2 (remaining in the same forest fragment) or 3 (dispersing to another forest fragment). It should be noted that all individuals who dispersed never resettle in their initial group or forest fragment.

Goodness-of-fit (GOF) tests for multistate models were run using U_CARE2.3.2. (Choquet, Lebreton, et al., 2009). Three tests were run to check for transience (heterogeneity in survival rate due to an excess of individuals captured the first time and never seen again) and one test to check trap-dependence (heterogeneity in resighting rates due to an excess of individuals resighted more than others). Any significant test (p<0.05) indicates a break in homogeneity assumptions in survival and resighting probabilities and requires a more complex model structure than a time- and state-dependent effect (Choquet, Lebreton, et al., 2009).

The software E-Surge (Choquet, Rouan, et al., 2009) was used to build and fit multi-state models where transition probabilities between states were decomposed into three consecutive steps: survival (s), dispersal (Ψ) and resighting (p). Model selection was performed based on the Quasi-likelihood Akaikes’ information criterion, corrected for small sample size and overdispersion (QAICc, (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). The model with the lowest QAICc was considered the best model. Model structure was defined in 3 steps by testing the effects of time, sex and their interactions for each transition separately. Specifically, one transition was tested with different time and/or sex effects while the two others were kept constant. The model with the lowest QAICc indicated the best structure for the transition considered.

First results showed that sex was uninformative for all transitions, as models including this effect had similar QAICc as the constant ones (difference < 2). Following (Arnold, 2010), sex was thus removed from the initial model structure and GOF tests were rerun on the pooled dataset (

Table 1). Furthermore, models with fully time-dependent dispersal probabilities performed poorly due to the low number of dispersal events in the dataset. Time effect was thus replaced by a categorial time effect (

Table 2). This effect denoted 3T considered three distinct dispersal probabilities before, during and after the outbreak. We compared this three periods effect with a two periods effect, (before/after and during the outbreak (2T), and a constant time effect (1T). Finally, detection probabilities for state 1 and 2 were always equal to 1 so they were grouped together (2f) and fixed to 1 so that the model would only estimate detection probabilities for state 3 (individuals dispersed to another forest fragment). Overall, the best model structure included fully time-dependence for survival, a categorial time effect for dispersal and a state effect for detection probabilities. Full final model selection as well as the different matrices used in E-surge can be found in Appendix 1.

Results

Goodness-of-fit tests run on pooled male and female data detected a significant age effect with Test 3G.Sm (

Table 1), for years 2017 and 2018. New individuals first observed in 2016 or 2017 had a different survival in years 2017 and 2018 compared to individuals first observed before 2016 or after 2018. Test M-ITEC detected a marginal effect of trap-dependence (p=0.05). To account for these two sources of heterogeneity, we used a cohort effect to separate individuals based on the year of their first observation. Up to 3 cohorts (3c) were tested for survival (

Table 2), depending on when individuals were first observed (before, during or after the outbreak). Overall, the best model had fully time-dependent survival probabilities for 2 distinct cohorts for individuals first encountered before/after or during the outbreak (2c.t), two periods for dispersal probabilities (2T) and state-dependent (2f) detection probabilities (

Table 3).

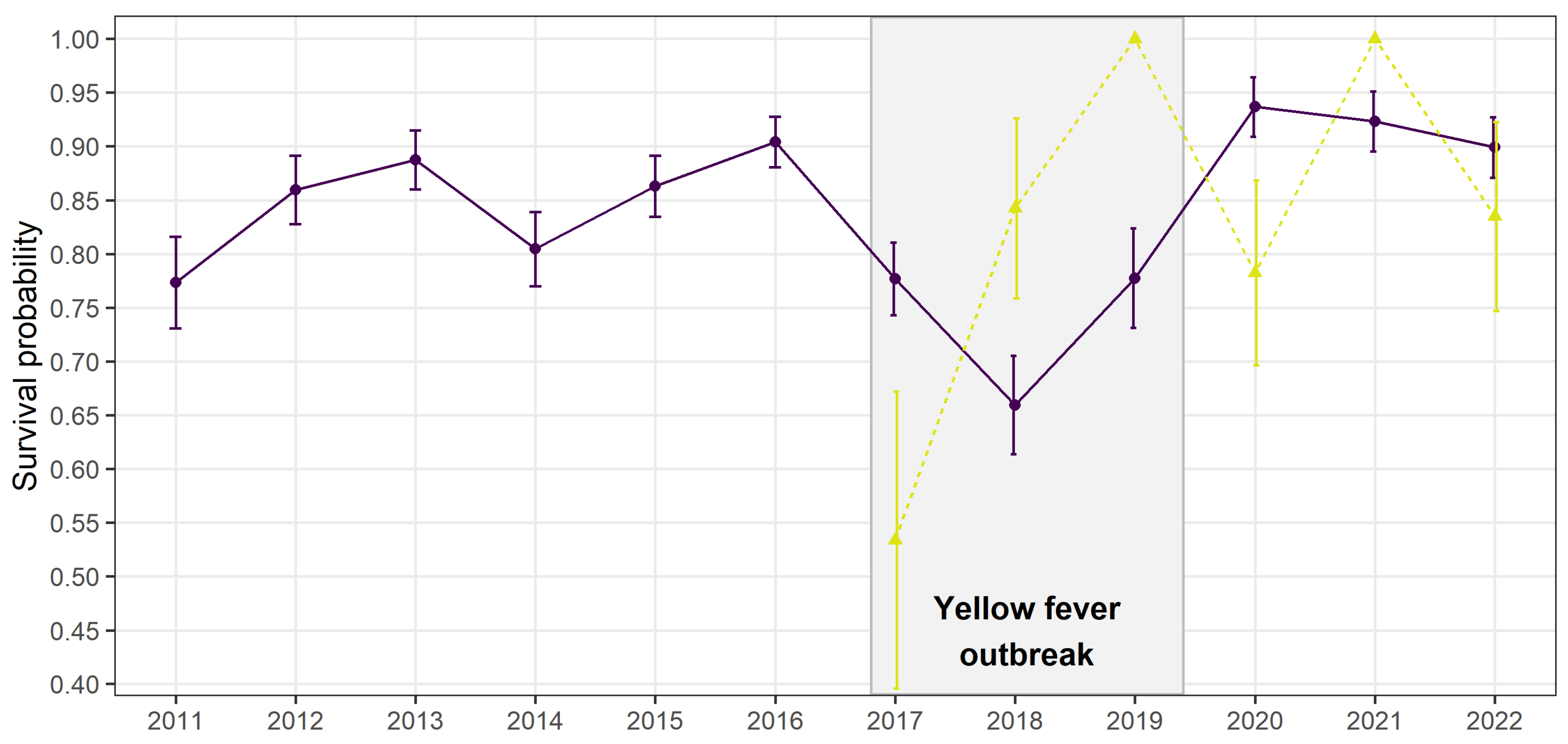

As expected, adult annual survival rate for the first cohort was highly variable over the entire period but drastically decreased in 2017 and 2018, matching the period of the yellow fever outbreak (

Figure 2). From 2019, which coincides with the end of the outbreak, survival bounced back to levels higher than before the outbreak, with survival probabilities higher than 0.9. The second cohort, made of individuals first encountered the year before the outbreak in 2016, had a lower survival rate the first year of the outbreak in 2017 but higher ones the next 2 years (

Figure 2). Following heterogeneous peaks of survival had larger confidence intervals.

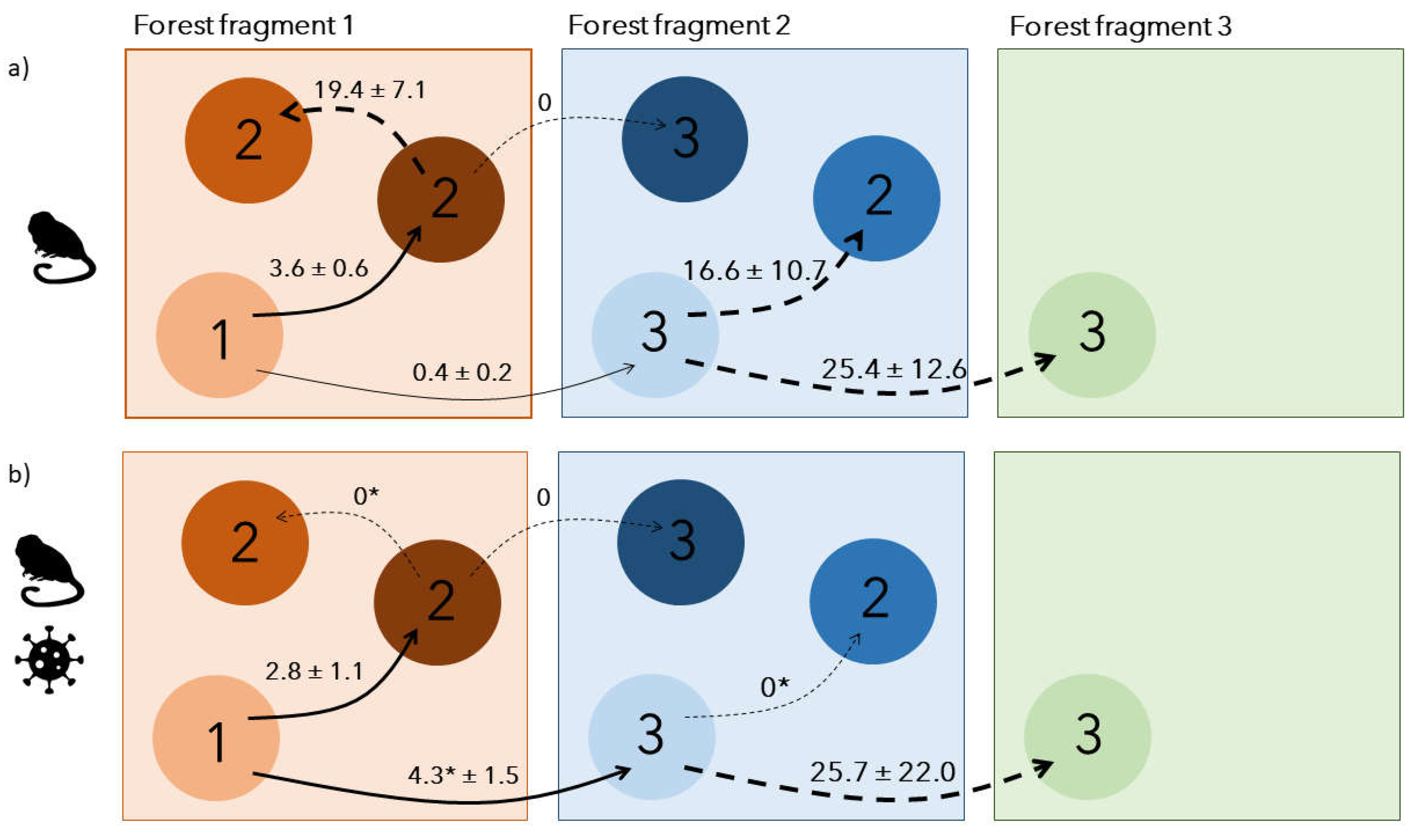

Dispersal was best modelled with 2 sets of distinct dispersal rates (2T;

Table 3): one before/after the outbreak period, in 2012-2016/2019-2022 and one during the outbreak, in 2017-2018. Before the outbreak, dispersal rates were generally low: 3.6 ± 0.6 % of individuals performed a first dispersal event towards groups within the same forest fragment, while 0.4 ± 0.2% dispersed to groups outside their current forest fragment (

Figure 3a). After first dispersal within the same forest fragment, 19.3 ± 7.1 % of individuals continued dispersing to another group of the same forest fragment the following year, while none continued to another forest fragment. For individuals reaching a new forest fragment at first dispersal, 25.4 ± 12.6 % continued dispersing to another forest fragment the following year while 16.6 ± 10.7% dispersed within the same forest fragment (

Figure 3a).

During the outbreak, the total dispersal probability remained low but the spatial dispersal patterns changed (

Figure 3b). While individuals dispersing towards groups of the same forest fragment slightly decreased to 2.8 ± 1.1%, individuals dispersing to a new forest fragment increased by 10-fold, reaching 4.3 ± 1.5%. Once individuals had dispersed once, they either settled for good in their new group or continued dispersing towards a new forest fragment only if they had already changed forest fragment (

Figure 3b). After the outbreak, dispersal rates came back to the same levels as before, as the best selected model included only two periods, outbreak (2017-2018) and before/after the outbreak (2011-2016/ 2019-2022;

Table 3).

Resighting probabilities depended on individual state: all individuals were always resighted when they remained faithful to their initial conservation area, regardless of local dispersal (p=1). However, after dispersing to a new forest fragment, the resighting probability of an individual decreased to 56.5 ± 12.8%.

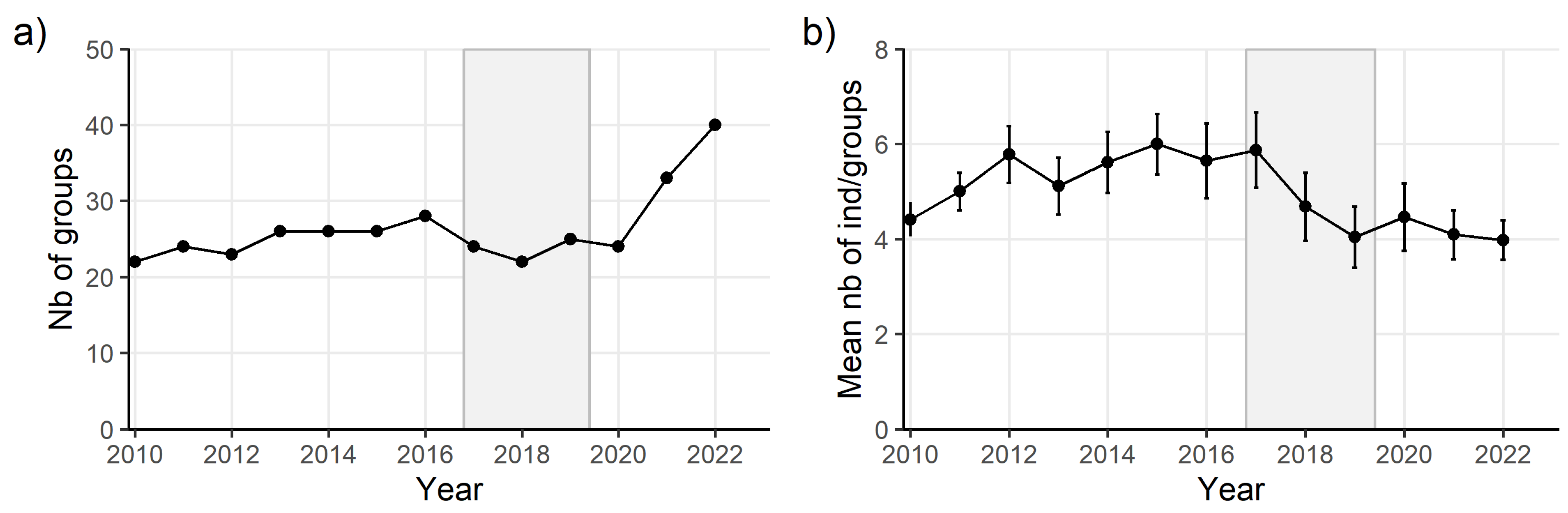

The number of monitored groups remained relatively stable before and during the outbreak (

Figure 4a) but the number of individuals composing groups significantly decreased during the outbreak (

Figure 4b). After the disease, the number of groups substantially increased while the mean number of individuals in groups remained stable (

Figure 4). The constant resighting of monitored individuals remaining within the same forest fragment over years, ensures a robust estimate of the number of monitored groups and of the number of individuals composing those groups.

Discussion

Vector-borne diseases cause major public health issues and drastically impact animal populations. Understanding their eco-epidemiological dynamics is key in predicting their emergence potential and their consequences on animal populations but it is hampered by the complexity of ecological interactions between hosts and vectors, especially in fragmented landscapes (Chala & Hamde, 2021). Here, we inferred individual host movements within and between forest fragments from long-term capture-recapture data to examine primates’ potential response to a disease outbreak and assess their population recovery. We revealed that the adult annual survival of golden lion tamarins was reduced by at least 14% during an important outbreak of yellow fever in 2016-2019. The observed temporary drop in survival was concomitant with a major temporary change in the dispersal patterns of individuals, both within and between forest fragments. Temporary alteration of host movements during major disease outbreaks have already been demonstrated in primates and birds (Dekelaita et al., 2023; Duriez et al., 2023; Genton et al., 2015; Jeglinski et al., 2024; Lachish et al., 2011) but interactions between individual social behaviour, host movements and landscape configuration have never been explicitly and empirically addressed, especially in the case of vector-borne diseases.

Dispersal probabilities within the same forest fragment remained relatively stable and low over the entire study period (2.8 ± 1.1% during the outbreak vs. 3.6 ± 0.6 % outside outbreak), as did the total number of groups. Contrastingly, group size significantly decreased during the outbreak. This suggests a non-random mortality within social groups probably induced by yellow fever, which affected group size but not density of groups in forest fragments. This non-random mortality is supported by the extremely variable annual survival probabilities of a second cohort appearing the first year of the outbreak (

Figure 2). A lack of data on sick individuals prevents us from drawing solid conclusions on the origin of this second cohort but higher susceptibility to yellow fever, lower social status, lower body condition or younger age may be factors explaining the lower survival in 2017 of individuals first observed in 2016 (Caillaud et al., 2006; Höner et al., 2012). The following year, in 2018, those surviving individuals may have developed stronger immunity or rearrangement in group structure and size may have favoured their survival, which outperformed the one from the first cohort (

Figure 2).

Regarding dispersal, with fewer individuals composing social groups, it might have been easier for local dispersing individuals to integrate other existing groups within the same forest fragment because of lower competition to acquire a new breeding status (Lachish et al., 2011; Muths et al., 2011). It may also have opened up new breeding opportunities for immigrants but also local subadults (Romano et al., 2019). Given the simultaneous increase in regional dispersal rate, those locally dispersing individuals may have had higher competitive abilities, forcing other dispersing individuals to find groups at larger spatial scales. As a result, local highly competitive individuals would settle more rapidly after the first dispersal, over shorter distances, leading to a temporary disappearance of secondary local dispersal during the outbreak (

Figure 3). In normal conditions, dispersal between forest fragments was negligible but increased by 10 times to reach 4.3% during the yellow fever outbreak. It even became more important than local dispersal. This increase might be explained by two non-exclusive hypotheses: 1) individuals dispersing regionally may have actively decided to escape from areas highly affected by yellow fever and settle in other potentially safer forest fragments and 2) individuals may not have had sufficient competitive abilities to secure a new social status in surviving local groups so they would have to seek other groups at larger distances and over longer periods, as reflected by the high probability of dispersing again after a first dispersal.

As expected, males and females had the same dispersal probability. This aligns with previous findings indicating that both males and females disperse (Romano et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the general primary dispersal rates < 5% are lower compared to dispersal event counts for the same species (Romano et al., 2019), possibly because we only examined adult dispersal with individuals older than 18 months. By doing so, we excluded potential parallel dispersal of parents with younger individuals but those events remain rare in golden lion tamarins (Romano et al., 2019). Individuals may have also actively left their social group to self-isolate to avoid disease exposure and/or transmission (Genton et al., 2015). But this is unlikely, as the golden lion tamarin is a highly social species (Baker & Dietz, 1996). Moreover, this strategy may be inefficient in response to a vector-borne disease transmitted by mosquitoes.

Mortality rates due to yellow fever in primates are relatively high (Possamai et al., 2022) and infected individuals are likely to be sick, which may directly reduce their movement ability and thereby, their dispersal ability (Binning et al., 2017; Dekelaita et al., 2023; Duriez et al., 2023; Lachish et al., 2011). Infected golden lion tamarins are therefore unlikely to vehiculate the disease through dispersal movements, especially between forest fragments (Possas et al., 2018). Within forest fragments, the low dispersal probabilities suggest that the potential spread of yellow fever towards other groups through host movements is relatively limited as well.

Because of the irregular monitoring effort within and between years, we had to summarise individual observations to annual ones, missing potential short temporary exploratory movements towards other groups (e.g., Baker & Dietz, 1996). As observed in the raw data, individuals can perform prospecting movements, during which they temporally visit other groups than their current one and gather information which help them make informed dispersal decisions (Ponchon, 2024). Those movements have been identified as crucial in an eco-epidemiological context, as they enhance connectivity between social groups and facilitate disease spread (Boulinier et al., 2016). Nevertheless, transmission of vector-borne diseases during host transience mainly depends on the presence of infectious vectors in the environment and the duration of exposure of hosts to vectors (Stoddard et al., 2009). Because prospecting visits are assumed to be relatively short in primates (minutes to hours ; Teichroeb et al. 2011), it is unlikely that such movements may have accelerated the spread of a vector-borne disease to other social groups, especially at a regional scale.

On the contrary, vector movements have been acknowledged as the principal mode of propagation of vector-borne diseases (Sumner et al., 2017), especially in fragmented landscapes (Ribeiro Prist et al., 2022). In the Brazilian state of Sao Paulo, one study has confirmed that yellow fever rapid spread among primates and humans in 2016-2019 was facilitated by the dispersal of vector mosquitoes transiting in areas with roads adjacent to forests and forest edges going along agricultural areas (Ribeiro Prist et al., 2022). Landscape connectivity is therefore extremely important in vector-host-pathogen interactions: whereas roads hamper primate host movements between habitat fragments and thereby negatively affect their population dynamics (Arce-Peña et al., 2019), landscape degradation and fragmentation further facilitate disease spread through vector movements (Ribeiro Prist et al., 2022). Restoring habitat connectivity is thus key not only to enhance host dispersal between habitat fragments and thereby, favour their conservation but also limit the spread of vector-borne diseases over large spatial scales and protect human health (McCallum & Dobson, 2002).

Even though the golden lion tamarin population was dramatically hit by yellow fever, annual adult survival rate started increasing again one year before the reported end of the outbreak in April 2019. It reached rates > 0.9 the following years, even higher rates than the ones recorded before the outbreak (

Figure 2). Along with the strong increase in the number of monitored social groups and low dispersal probabilities, this suggests that new individuals (either new adults born locally during/after the outbreak or immigrants from non-monitored areas)- entered the population by forming new groups rather than competing to integrate existing groups. This is consistent with a recent detailed monitoring survey of the golden lion tamarin population which showed that new forest fragments were colonized after the outbreak and that social groups in general had a lower number of individuals (Dietz et al., 2024). Altogether, those results highlight the resilience potential of the golden lion tamarin population after a high mortality event due to a disease outbreak, as already reported in other primate species which recovered relatively quickly after dramatic outbreaks of directly-transmitted pathogens (Caillaud et al., 2006; Genton et al., 2015). Social flexibility has been highlighted as a key adaptive response to unpredictable environments (Motes-Rodrigo et al., 2025; Schradin et al., 2019). Our study provides new evidence that behavioural changes through dispersal decisions can also be an adaptive response of social species facing deadly infectious disease outbreaks. Detecting those changes will be vital to prevent or respond to outbreaks which may further spill-over to humans.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

References

- Abreu, F. V., Ferreira-de-Brito, A., Azevedo, A. D., Linhares, J. H., de Oliveira Santos, V., Hime Miranda, E., Neves, M. S., Yousfi, L., Ribeiro, I. P., Santos, A. A., dos Santos, E., Santos, T. P., Teixeira, D. S., Gomes, M. Q., Fernandes, C. B., Silva, A. M., Lima, M. D., Paupy, C., Romano, A. P., … Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R. (2020). Survey on Non-Human Primates and Mosquitoes Does not Provide Evidences of Spillover/Spillback between the Urban and Sylvatic Cycles of Yellow Fever and Zika Viruses Following Severe Outbreaks in Southeast Brazil. Viruses, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Arce-Peña, N. P., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Dias, P. A. D., Franch-Pardo, I., & Andresen, E. (2019). Linking changes in landscape structure to population changes of an endangered primate. Landscape Ecology, 34(11), Article 11. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, T. W. (2010). Uninformative Parameters and Model Selection Using Akaike’s Information Criterion. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(6), 1175–1178. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. J., & Dietz, J. M. (1996). Immigration in wild groups of golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia). American Journal of Primatology, 38(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, M., Rodríguez-Teijeiro, J. D., Illera, G., Barroso, A., Vilà, C., & Walsh, P. D. (2006). Ebola Outbreak Killed 5000 Gorillas. Science, 314(5805), 1564–1564. [CrossRef]

- Berthet, M., Mesbahi, G., Duvot, G., Zuberbühler, K., Cäsar, C., & Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2021). Dramatic decline in a titi monkey population after the 2016–2018 sylvatic yellow fever outbreak in Brazil. American Journal of Primatology, 83(12), e23335. [CrossRef]

- Bicca-Marques, J. C., & de Freitas, D. S. (2010). The Role of Monkeys, Mosquitoes, and Humans in the Occurrence of a Yellow Fever Outbreak in a Fragmented Landscape in South Brazil: Protecting Howler Monkeys is a Matter of Public Health. Tropical Conservation Science, 3(1), 78–89. [CrossRef]

- Binning, S. A., Shaw, A. K., & Roche, D. G. (2017). Parasites and Host Performance: Incorporating Infection into Our Understanding of Animal Movement. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(2), 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Boulinier, T., Kada, S., Ponchon, A., Dupraz, M., Dietrich, M., Gamble, A., Bourret, V., Duriez, O., Bazire, R., Tornos, J., Tveraa, T., Chambert, T., Garnier, R., & McCoy, K. D. (2016). Migration, Prospecting, Dispersal? What Host Movement Matters for Infectious Agent Circulation? Integrative and Comparative Biology, 56, 330–342. [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach (2nd Edition). Springer.

- Caillaud, D., Levréro, F., Cristescu, R., Gatti, S., Dewas, M., Douadi, M., Gautier-Hion, A., Raymond, M., & Ménard, N. (2006). Gorilla susceptibility to Ebola virus: The cost of sociality. Current Biology, 16(13), R489-91. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Chala, B., & Hamde, F. (2021). Emerging and Re-emerging Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases and the Challenges for Control: A Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.715759.

- Choquet, R., Lebreton, J.-D., Gimenez, O., Reboulet, A.-M., & Pradel, R. (2009). U-CARE: Utilities for performing goodness of fit tests and manipulating CApture–REcapture data. Ecography, 32(6), 1071–1074. [CrossRef]

- Choquet, R., Rouan, L., & Pradel, R. (2009). Program E-Surge: Software application for fitting multievent models. In D. Thomson, E. Cooch, & M. Conroy (Eds.), Modeling demographic processes in marked populations (Vol. 3, pp. 845–865). Springer US.

- Coelho Couto de Azevedo Fernandes, N., Sequetin Cuhna, M., Mariotti Guerra, J., Albergaria Réssio, R., dos Santos Cirqueira, C., D’Andretta Iglezias, S., de Carvalho, J., Araujo, E. L. L., Catão-Dias, J. L., & Dias-Delagdo, J. (2017). Outbreak of Yellow Fever among Nonhuman Primates, Espirito Santo, Brazil, 2017. Emerging Infectious Disease, 2038–2041.

- Dekelaita, D. J., Epps, C. W., German, D. W., Powers, J. G., Gonzales, B. J., Abella-Vu, R. K., Darby, N. W., Hughson, D. L., & Stewart, K. M. (2023). Animal movement and associated infectious disease risk in a metapopulation. Royal Society Open Science, 10(2), 220390. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J. M., Hankerson, S. J., Alexandre, B. R., Henry, M. D., Martins, A. F., Ferraz, L. P., & Ruiz-Miranda, C. R. (2019). Yellow fever in Brazil threatens successful recovery of endangered golden lion tamarins. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 12926. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J. M., Mickelberg, J., Traylor-Holzer, K., Martins, A. F., Souza, M. N., & Hankerson, S. J. (2024). Golden lion tamarin metapopulation dynamics five years after heavy losses to yellow fever. American Journal of Primatology, 86(7), e23635. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J. M., Peres, C. A., & Pinder, L. (1997). Foraging ecology and use of space in wild golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia). American Journal of Primatology, 41(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, E. R., Seidel, D. P., Carlson, C. J., Spiegel, O., & Getz, W. M. (2018). Going through the motions: Incorporating movement analyses into disease research. Ecology Letters, 21(4), 588–604. [CrossRef]

- Duriez, O., Sassi, Y., Le Gall-Ladevèze, C., Giraud, L., Straughan, R., Dauverné, L., Terras, A., Boulinier, T., Choquet, R., Van De Wiele, A., Hirschinger, J., Guérin, J.-L., & Le Loc’h, G. (2023). Highly pathogenic avian influenza affects vultures’ movements and breeding output. Current Biology, 33(17), 3766-3774.e3. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A., Garber, P. A., Rylands, A. B., Roos, C., Fernandez-Duque, E., Di Fiore, A., Nekaris, K. A.-I., Nijman, V., Heymann, E. W., Lambert, J. E., Rovero, F., Barelli, C., Setchell, J. M., Gillespie, T. R., Mittermeier, R. A., Arregoitia, L. V., de Guinea, M., Gouveia, S., Dobrovolski, R., … Li, B. (2017). Impending extinction crisis of the world’s primates: Why primates matter. Science Advances, 3(1), e1600946. [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, J., & Millien, V. (2016). Stress level, parasite load, and movement pattern in a small-mammal reservoir host for Lyme disease. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 94(8), 565–573. [CrossRef]

- Genton, C., Pierre, A., Cristescu, R., Lévréro, F., Gatti, S., Pierre, J.-S., Ménard, N., & Le Gouar, P. (2015). How Ebola impacts social dynamics in gorillas: A multistate modelling approach. Journal of Animal Ecology, 84(1), 166–176. [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti Marta, de Mendonça Marcos Cesar Lima, Fonseca Vagner, Mares-Guia Maria Angélica, Fabri Allison, Xavier Joilson, de Jesus Jaqueline Goes, Gräf Tiago, dos Santos Rodrigues Cintia Damasceno, dos Santos Carolina Cardoso, Sampaio Simone Alves, Chalhoub Flavia Lowen Levy, de Bruycker Nogueira Fernanda, Theze Julien, Romano Alessandro Pecego Martins, Ramos Daniel Garkauskas, de Abreu Andre Luiz, Oliveira Wanderson Kleber, do Carmo Said Rodrigo Fabiano, … de Filippis Ana Maria Bispo. (2019). Yellow Fever Virus Reemergence and Spread in Southeast Brazil, 2016–2019. Journal of Virology, 94(1), 10.1128/jvi.01623-19. [CrossRef]

- Höner, O. P., Wachter, B., Goller, K. V., Hofer, H., Runyoro, V., Thierer, D., Fyumagwa, R. D., Müller, T., & East, M. L. (2012). The impact of a pathogenic bacterium on a social carnivore population. Journal of Animal Ecology, 81(1), 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Jeglinski, J. W. E., Lane, J. V., Votier, S. C., Furness, R. W., Hamer, K. C., McCafferty, D. J., Nager, R. G., Sheddan, M., Wanless, S., & Matthiopoulos, J. (2024). HPAIV outbreak triggers short-term colony connectivity in a seabird metapopulation. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 3126. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. E., Patel, N. G., Levy, M. A., Storeygard, A., Balk, D., Gittleman, J. L., & Daszak, P. (2008). Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 451(7181), 990–993. [CrossRef]

- Kierulff, M. C. M., Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., de Oliveira, P. P., Beck, B. B., Martins, A., Dietz, J. M., Rambaldi, D. M., & Baker, A. J. (2012). The Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia: A conservation success story. International Zoo Yearbook, 46(1), 36–45. [CrossRef]

- Lachish, S., Miller, K. J., Storfer, A., Goldizen, A. W., & Jones, M. E. (2011). Evidence that disease-induced population decline changes genetic structure and alters dispersal patterns in the Tasmanian devil. Heredity, 106(1), 172–182. [CrossRef]

- Lagrange, P., Pradel, R., Bélisle, M., & Gimenez, O. (2014). Estimating dispersal among numerous sites using capture–recapture data. Ecology, 95(8), Article 8.

- Langwig, K. E., Frick, W. F., Bried, J. T., Hicks, A. C., Kunz, T. H., & Marm Kilpatrick, A. (2012). Sociality, density-dependence and microclimates determine the persistence of populations suffering from a novel fungal disease, white-nose syndrome. Ecology Letters, 15(9), 1050–1057. [CrossRef]

- Leendertz, F. H., Ellerbrok, H., Boesch, C., Couacy-Hymann, E., Mätz-Rensing, K., Hakenbeck, R., Bergmann, C., Abaza, P., Junglen, S., Moebius, Y., Vigilant, L., Formenty, P., & Pauli, G. (2004). Anthrax kills wild chimpanzees in a tropical rainforest. Nature, 430(6998), Article 6998. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P. C., Block, P., & König, B. (2016). Infection-induced behavioural changes reduce connectivity and the potential for disease spread in wild mice contact networks. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 31790. [CrossRef]

- Loveridge, A. J., & Macdonald, D. W. (2001). Seasonality in spatial organization and dispersal of sympatric jackals (Canis mesomelas and C. adustus): Implications for rabies management. Journal of Zoology, 253(1), 101–111. Cambridge Core. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, H., & Dobson, A. (2002). Disease, habitat fragmentation and conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 269(1504), 2041–2049. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A. M., Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., Galetti Jr., P. M., Niebuhr, B. B., Alexandre, B. R., Muylaert, R. L., Grativol, A. D., Ribeiro, J. W., Ferreira, A. N., & Ribeiro, M. C. (2018). Landscape resistance influences effective dispersal of endangered golden lion tamarins within the Atlantic Forest. Biological Conservation, 224, 178–187. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R. E., Mushimiyimana, Y., Stoinski, T. S., & Eckardt, W. (2021). Rapid transmission of respiratory infections within but not between mountain gorilla groups. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Motes-Rodrigo, A., Albery, G. F., Negron-Del Valle, J. E., Philips, D., Cayo Biobank Research Unit, Platt, M. L., Brent, L. J. N., & Testard, C. (2025). A Natural Disaster Exacerbates and Redistributes Disease Risk Among Free-Ranging Macaques by Altering Social Structure. Ecology Letters, 28(1), e70000. [CrossRef]

- Muths, E., Scherer, R. D., & Pilliod, D. S. (2011). Compensatory effects of recruitment and survival when amphibian populations are perturbed by disease. Journal of Applied Ecology, 48(4), 873–879. [CrossRef]

- Nunn, C. L., Thrall, P. H., Stewart, K., & Harcourt, A. H. (2008). Emerging infectious diseases and animal social systems. Evolutionary Ecology, 22(4), 519–543. [CrossRef]

- Pfenning-Butterworth, A., Buckley, L. B., Drake, J. M., Farner, J. E., Farrell, M. J., Gehman, A.-L. M., Mordecai, E. A., Stephens, P. R., Gittleman, J. L., & Davies, T. J. (2024). Interconnecting global threats: Climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(4), e270–e283. [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A. (2024). Prospecting for informed dispersal: Reappraisal of a widespread but overlooked ecological process. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Possamai, C. B., Rodrigues de Melo, F., Mendes, S. L., & Strier, K. B. (2022). Demographic changes in an Atlantic Forest primate community following a yellow fever outbreak. American Journal of Primatology, 84(9), e23425. [CrossRef]

- Possas, C., Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R., Tauil, P. L., Pinheiro, F. de P., Pissinatti, A., Cunha, R. V. da, Freire, M., Martins, R. M., & Homma, A. (2018). Yellow fever outbreak in Brazil: The puzzle of rapid viral spread and challenges for immunisation. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 113.

- Ribeiro Prist, P., Reverberi Tambosi, L., Filipe Mucci, L., Pinter, A., Pereira de Souza, R., de Lara Muylaert, R., Roger Rhodes, J., Henrique Comin, C., da Fontoura Costa, L., Lang D’Agostini, T., Telles de Deus, J., Pavão, M., Port-Carvalho, M., Del Castillo Saad, L., Mureb Sallum, M. A., Fernandes Spinola, R. M., & Metzger, J. P. (2022). Roads and forest edges facilitate yellow fever virus dispersion. Journal of Applied Ecology, 59(1), 4–17. [CrossRef]

- Romano, V., MacIntosh, A. J. J., & Sueur, C. (2020). Stemming the Flow: Information, Infection, and Social Evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35(10), 849–853. [CrossRef]

- Romano, V., Martins, A. F., & Ruiz-Miranda, C. R. (2019). Unraveling the dispersal patterns and the social drivers of natal emigration of a cooperative breeding mammal, the golden lion tamarin. American Journal of Primatology, 81(3), e22959. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., de Morais, M. M., Jr., Dietz, L. A., Rocha Alexandre, B., Martins, A. F., Ferraz, L. P., Mickelberg, J., Hankerson, S. J., & Dietz, J. M. (2019). Estimating population sizes to evaluate progress in conservation of endangered golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia). PLOS ONE, 14(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Sacchetto, L., Drumond, B. P., Han, B. A., Nogueira, M. L., & Vasilakis, N. (2020). Re-emergence of yellow fever in the neotropics—Quo vadis? Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 4(4), 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Schradin, C., Pillay, N., & Bertelsmeier, C. (2019). Social flexibility and environmental unpredictability in African striped mice. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 73(7), 94. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. F., Acevedo-Whitehouse, K., & Pedersen, A. B. (2009). The role of infectious diseases in biological conservation. Animal Conservation, 12(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Stockmaier, S., Stroeymeyt, N., Shattuck, E. C., Hawley, D. M., Meyers, L. A., & Bolnick, D. I. (2021). Infectious diseases and social distancing in nature. Science, 371(6533), eabc8881. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, S. T., Morrison, A. C., Vazquez-Prokopec, G. M., Paz Soldan, V., Kochel, T. J., Kitron, U., Elder, J. P., & Scott, T. W. (2009). The Role of Human Movement in the Transmission of Vector-Borne Pathogens. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 3(7), e481. [CrossRef]

- Strier, K. B., Tabacow, F. P., de Possamai, C. B., Ferreira, A. I. G., Nery, M. S., de Melo, F. R., & Mendes, S. L. (2019). Status of the northern muriqui (Brachyteles hypoxanthus) in the time of yellow fever. Primates, 60(1), 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Sumner, T., Orton, R. J., Green, D. M., Kao, R. R., & Gubbins, S. (2017). Quantifying the roles of host movement and vector dispersal in the transmission of vector-borne diseases of livestock. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Teichroeb, J. A., Wikberg, E. C., & Sicotte, P. (2011). Dispersal in male ursine colobus monkeys (Colobus vellerosus): Influence of age, rank and contact with other groups on dispersal decisions. Behaviour, 148(7), Article 7.

- Tracey, J. A., Bevins, S. N., VandeWoude, S., & Crooks, K. R. (2014). An agent-based movement model to assess the impact of landscape fragmentation on disease transmission. Ecosphere, 5(9), art119. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P. D., Abernethy, K. A., Bermejo, M., Beyers, R., De Wachter, P., Akou, M. E., Huijbregts, B., Mambounga, D. I., Toham, A. K., Kilbourn, A. M., Lahm, S. A., Latour, S., Maisels, F., Mbina, C., Mihindou, Y., Ndong Obiang, S., Effa, E. N., Starkey, M. P., Telfer, P., … Wilkie, D. S. (2003). Catastrophic ape decline in western equatorial Africa. Nature, 422(6932), 611–614. [CrossRef]

- Watts, A. G., Saura, S., Jardine, C., Leighton, P., Werden, L., & Fortin, M.-J. (2018). Host functional connectivity and the spread potential of Lyme disease. Landscape Ecology, 33(11), 1925–1938. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).