1. Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were utilised due to their exceptional chemical and physical properties, with a particular emphasis on fascinating optical characteristics arising from local surface plasmonic resonance (LSPR) [

1,

2,

3]. LSPR is the occurrence of a resonance of the incident electromagnetic field and the plasmon of a particle, which occurs when the frequency of the electromagnetic field is equal to the inherent frequency of oscillation of the cloud of free electrons within the particle. As a result of this resonance, the electronic cloud is excited, generating its own electric field that influences the absorption and scattering of light [

4,

5].

Thin layers of metallic materials undergo propagating surface plasmon resonance (PSPR), where the plasmon propagates along the surface of the film layer. PSPRs exhibit a continuous dispersion relation, enabling their existence across a broad spectrum of frequencies [

6]. In contrast, LSPR are confined to a finite frequency range, due to the constraints imposed by their finite dimensions. The spectral positioning of LSPR is dictated by factors such as the particle's size and shape, along with the dielectric properties of both the metal and the surrounding medium [

4,

5,

6]. Notably, LSPR can undergo direct coupling with propagating light, a capability not shared by PSPRs.

In the case of copper, silver and gold, LSPR occurs in the visible light range [

4,

7]. Therefore, these metallic elements are particularly appealing for optical applications, as they enable controlled manipulation of the light7s properties. This occurrence opens doors to numerous applications, where the unique optical characteristics of these noble metal nanoparticles can be exploited, such as in sensors [

8,

9,

10], biomedical applications [

7,

11,

12], or advanced optical materials [

13,

14].

The Mie theory allows for the prediction of LSPR in particles. For spherical particles there are simplified numerical models that assume various oscillations of the electronic cloud known as discrete dipole approximation (DDA), such as dipole and quadrupole oscillations [

4]. The analytical calculation of LSPR is feasible for spherical particles [

3,

15], whereas complex particle shapes require complex numerical solutions [

4,

16].

Analytical and numerical calculations offer a good prediction of absorption peaks of nanoparticle suspensions, since nanoparticles undergo Brownian motion [

5,

17,

18] and are in contact with other particles for an insignificant amount of time, if any at all, due to the presence of repulsive forces or steric stabilisers. Steric stabilisers are added to nanoparticles` suspensions to stabilise the solution and prevent agglomeration and aggregation when repulsive forces are not sufficient [

5,

19,

20]. Stabilisers can also prevent agglomeration and aggregation of nanoparticles, while removing the dispersion media slowly [

21,

22,

23]. Without the presence of stabilisers the nanoparticles agglomerate and aggregate during the removal of the dispersion media, which changes the colour of the gold nanoparticles directly. A similar phenomenon is expected when AuNPs are layered on each other with direct deposition within the reaction chamber of an ultrasound spray pyrolysis device. No sintering is expected to occur, since the temperatures inside the USP device in the deposition zone are not near the sintering temperature of AuNPs [

23]. No direct deposition of AuNPs from an ultrasonic spray pyrolysis process has been observed in the available literature- Therefore, this research work aims to characterise the optical properties of AuNPs film prepared by this technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis and Gold Nanoparticle Film Preparation

An ultrasonic spray pyrolysis process was used for producing the AuNPs layer on the glass substrate (

Figure 1). The precursor used was Au chloride (HAuCl4, Glentham Life Sciences, UK), dissolved in deionised water at a concentration of 0.5 g Au/L (1.0 g HAuCl4/L). The USP process was carried out using a proprietary device from Zlatarna Celje d.o.o., Slovenia [

24], consisting of a custom built tube furnace, an ultrasonic generator, a precursor supply system and a gas washing system for nanoparticle collection. The ultrasonic generator is constructed with a 1.6 MHz piezoceramic membrane for generating the ultrasound (Liquifog II, Johnson Matthey Piezo Products GmbH, Germany), which is submerged in a chamber for the aerosolisation of the precursor solution. The generated precursor mist was transported in the tube furnace with nitrogen gas at a rate of 6 l/min. The quartz tube furnace has three heating zones, with a length of 400 mm each and an internal diameter of 35 mm. The tube furnace heating zone temperatures were set at 200, 400 and 400 °C. The hydrogen gas was introduced into the tube between the first and second heating zones at a rate of 6 l/min. The glass substrate was positioned inside the reaction tube at an angle of 45°, about 10 cm from the end of the third heating zone. The precursor droplets inside the tube furnace undergo droplet evaporation and shrinkage, diffusion of the gold chloride to the droplet centre, gold chloride reduction with hydrogen gas and final nanoparticle densification, before hitting and depositing a layer of AuNPs on the glass substrate. Four samples were produced, with AuNPs` deposition times of 15 min, 30 min, 1h and 4h on the glass substrate.

2.2. Morphological Characterisation

A scanning electron microscope, Sirion 400 NC SEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), was used for the surface investigations of the prepared layer of AuNPs on the glass substrate,. The SEM was equipped with an INCA 350 EDS detector (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK), for microchemical analysis. The glass substrates with deposited AuNPs from the USP were coated with carbon for providing sufficient conductivity for the SEM imaging and EDS analysis.

2.3. Optical Characterisation

The prepared layers were characterised optically with Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV-vis) and ellipsometry.

The UV-vis measurements were performed with a Tecan Infinite M200 (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland) UV/Vis spectrophotometer, by inserting the sample plates in the light beam path with the following parameters: absorbance range: λ = 400 to 700 nm, no. flashes: 5×.

The samples were investigated by spectroscopic ellipsometry measurements in the spectral range between 0.57 and 3.5 eV with a V-VASE ellipsometer (J.A. Woollam, Lincoln, NE, USA), at incidences of 45°, 55° and 65°. The transmittance measurements at the normal incidence were taken at the same sample point, to increase the reliability of the characterisation results [

25]. In order to fit the experimental measurements, the layer of gold nanoparticles was modelled as a homogeneous thin film, with its optical response determined completely by its effective thickness and optical constants. The effective optical constants were modelled using a multiple oscillator model that can take into account the LSPR of the AuNPs and Au interband transitions in the high energy range, as described elsewhere [

26].

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characterisation

A detailed SEM examination of the samples showed AuNPs deposited in a discontinuous layer across the samples` surfaces (

Figure 2). The number of AuNPs was the lowest for the sample with 15 min of deposition, and increased as more time was given for deposition on the glass substrate. As expected, the sample with 4 h of deposition had the highest number of AuNPs, while the nanoparticle sizes were also the biggest for this sample.

The difference between nanoparticle sizes and shapes can be seen in

Figure 3. Larger particles were produced as more time was given to the AuNPs` deposition. The AuNPs with 15 min deposition were small, with measured sizes from 10-20 nm, with individual nanoparticles that were somewhat larger, mostly around 60-120 nm. An example of nanoparticle measurements of the sample with 1 h deposition is presented in

Figure 4. The smaller nanoparticles were spherical in shape, while the larger ones were spherical and became more irregular in shape as their sizes increased. With longer deposition times (30 min and 1 h), an increasingly higher number of larger nanoparticles around 100 nm and up to 200 nm were present, while the smaller 10-20 nm nanoparticles were still dominating in number. With the longest deposition time of 4 h, the larger particles were more numerous and prevalent on the sample surface as compared to the previous samples. In this sample, the larger irregularly shaped particles and clusters of these particles were measured up to a value of 400 nm. There were also dark spots present on the sample`s surface (

Figure 2(iv) and

Figure 3(iv)), where nanoparticles were not present, or only very small nanoparticles around 10 nm were present in lower numbers.

The EDX analysis of the samples showed the presence of Au, along with elements which were constituents of the glass substrate - Si, O and minor elements of Na, Mg, Ca, Al. The interaction volume of a few µm, from which x-rays are emitted during the EDS analysis, was much larger than the AuNPs` sizes, resulting in the detection of the glass substrate elements, along with the AuNPs. More importantly, no Cl or other impurities were detected in the samples, which would indicate an incomplete synthesis of the nanoparticles from the chloride precursor, or contamination from other elements during the synthesis and deposition of the AuNPs. An example of the EDX analysis for a sample with 1 h of AuNPs` deposition is shown in

Figure 4; the other samples had similar results.

3.2. Optical Characterisation

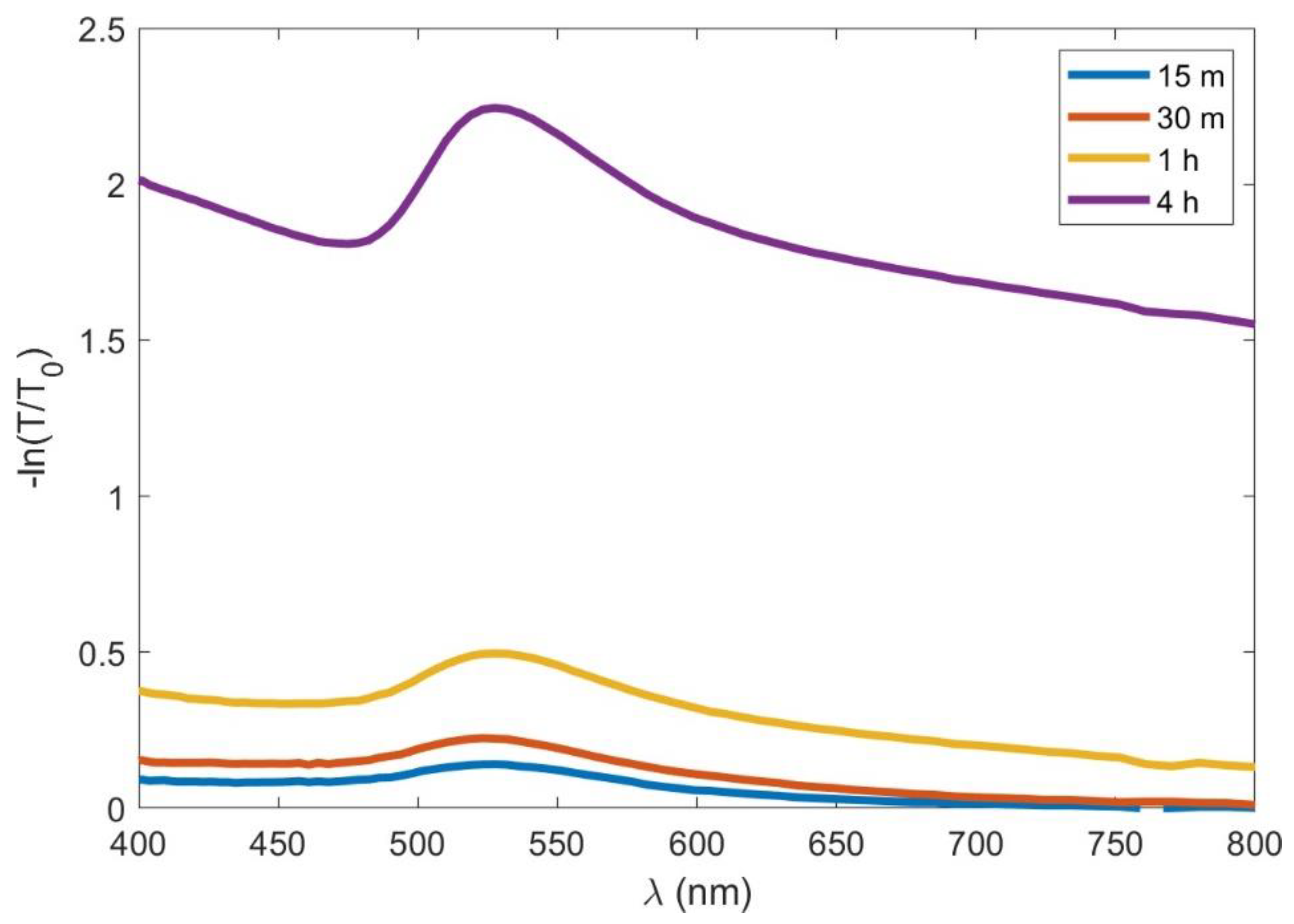

The extinction spectra of the samples with USP deposition for 15 min, 30 min, 1 h and 4h are shown in

Figure 5. The spectra display a clear LSPR signature (peak 520-540 nm), indicating the presence of isolated particles in all the samples. The strength of the extinction peak rose with the deposition time, accounting for the increase of the number of deposited particles. In addition to the LSPR peak, the larger deposition times resulted in a progressive increase of extinction in the long-wavelength range, that might be explained by electromagnetic interaction between the particles and the presence of larger/clustered particles, as discussed in

Section 4.

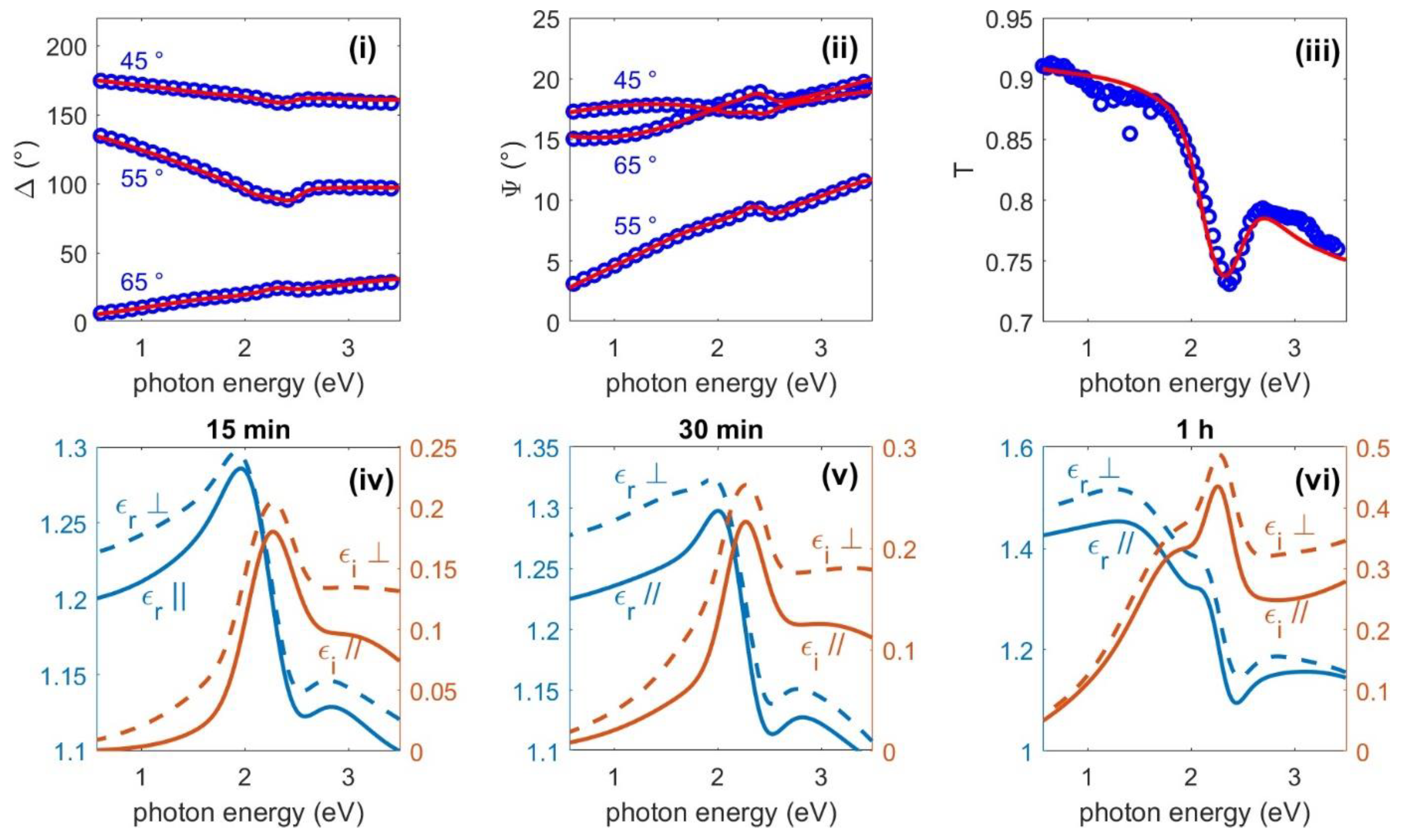

In a first step, ellipsometric measurements were fitted using an isotropic model for the effective optical constants of the AuNPs` layer, leading to a fair agreement with the experimental data. A significantly better agreement was obtained if the AuNPs` film was modelled as a uniaxial anisotropic layer, with different effective dielectric functions for light polarised along the plane parallel (ε//) or perpendicular (ε⏊) to the sample`s surface. As an example, the experimental data fits for the sample obtained for 30 minutes deposition are shown in

Figure 5(i)–(iii). The measurements for the sample obtained after 4 h deposition showed very large depolarisation values, probably due to large scattering, and it was not possible to fit them with the current model.

For all the AuNPs` layers, the imaginary part of both ε// and ε⏊ was dominated by a central peak around 2.2 eV, corresponding to the LSPR of isolated particles, and a high-energy shoulder due to Au interband transitions. It should be noted that the LSPR peak became broader and more intense for longer deposition times, that can be explained by a larger concentration of nanoparticles in the AuNPs` layer that gave place to stronger interparticle electromagnetic interactions [

27]. In general, both the real and imaginary parts of ε⏊ displayed larger values than ε//, which can be explained by the larger polarisability of the particle when light is polarised perpendicularly to the sample surface, due to the presence of the substrate and the resulting image effects [

28].

Finally, the effective thickness of the AuNPs` layer for samples deposited at 15, 30 and 60 min were 79, 97 and 110 nm, suggesting that, as the deposition time increased, the AuNPs` film not only got denser, but also grew in the vertical dimension.

4. Discussion

From the SEM examination it is seen that the initially deposited AuNPs were small, with sizes of about 10-20 nm. This is the mean particle size resulting from the initial precursor gold concentration of 0.5 g/l. As the aerosol droplets travel through the USP reaction tube, they are evaporated, and the gold salt content is reduced with hydrogen gas and densified into AuNPs at a suitable reaction temperature. Such small particles are not kinetically stabilised in the USP flow stream, and have a relatively high surface energy. As the number of AuNPs increases and the coverage of the glass substrate becomes greater, coalescence and aggregation occur to form larger individual particles. In the first stage, these larger individual particles are also spherical, but become increasingly irregular as they grow larger.

Evidence of particles shifting and growing together might be the dark spots observed in the advanced AuNPs` coverage of the sample with 4 h of deposition time, seen in

Figure 2(iv) and

Figure 3(iv). These dark spots are zones of particle depletion, as the very small AuNPs shifted towards the larger particles, where they aggregated and became a part of the larger particles, or as a part of clusters of primary nanoparticles. With additional deposition time these zones would again be filled up with AuNPs, until the larger particles would form an uninterrupted mesh-like structure, and, finally, a continuous Au layer on the glass substrate. Any other potential influence for particle formation was not considered, as the EDX analysis of the AuNPs showed no impurities in the analysed areas.

The samples with deposited AuNPs had a distinctive red transparent colour, and were increasingly less transparent with additional deposition time (supplementary Figure S1). The sample with 4 h of deposition had a visibly more opaque appearance. The ellipsometric measurements of this sample were also not applicable, due to large scattering of the produced particles. For the other samples, the ellipsometric measurements showed an increasingly denser and thicker effective thickness of the AuNP layers, in accordance with the described particle growth.

In order to understand the evolution of the extinction spectra at normal incidence as a function of the deposition time qualitatively (

Figure 5) and the effective dielectric function of the AuNP layer (

Figure 6), we performed simulations based on the multiple-particle Mie theory, as described elsewhere [

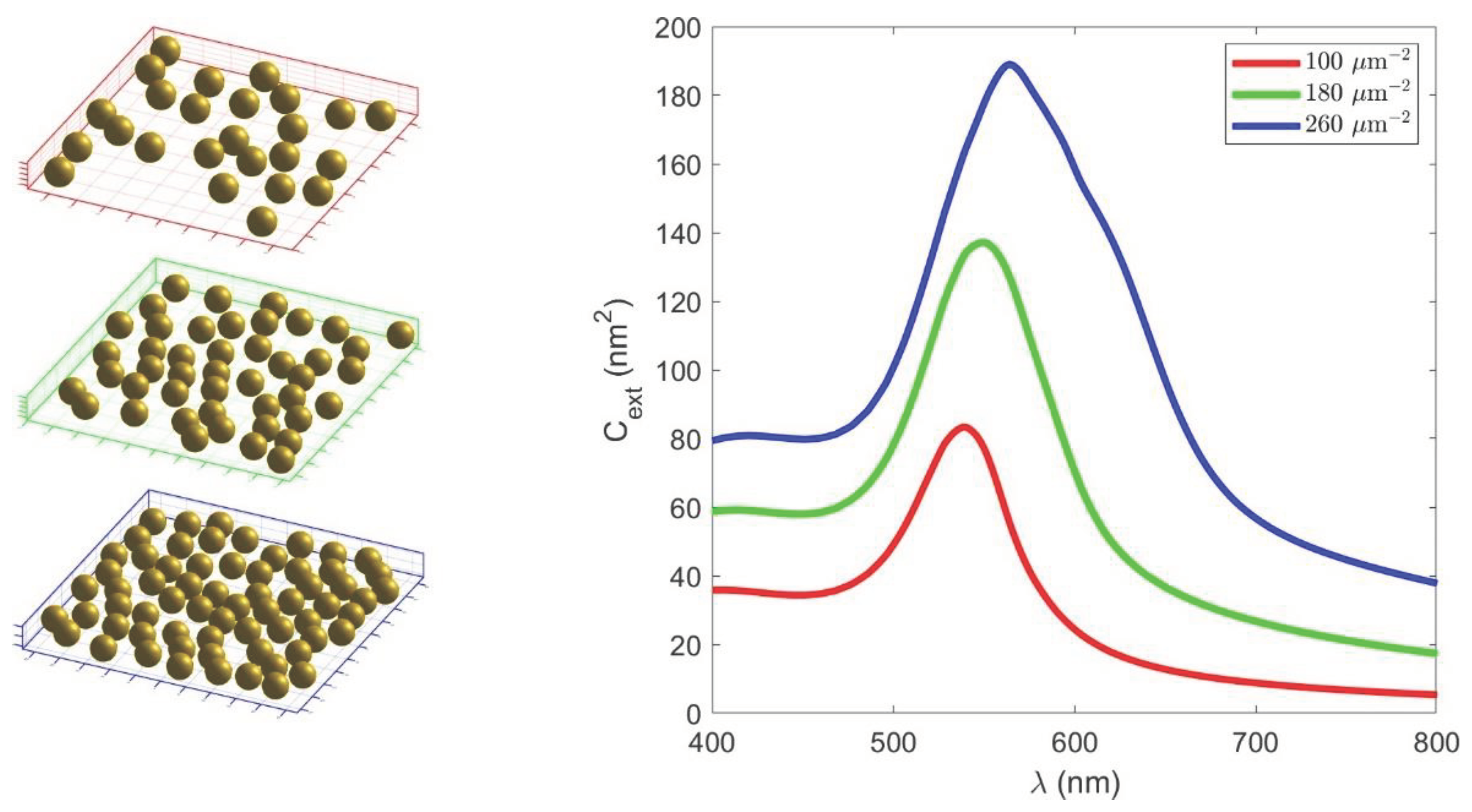

29]. In short, the simulations were based in an extension of the Mie theory, in which particles were excited by the incoming radiation and by the field scattered by other particles. We considered 50 nm Au particles embedded in a medium with a refractive index of 1.25 (i.e, the average of an air and glass refractive index) that were distributed randomly in the planar region of 500 nm x 500 nm, as shown schematically in

Figure 7 (left). The incoming light was assumed to propagate in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the particles, in order to represent normal incidence measurements. It was shown that, as the density of the particles increased, the extinction cross-section grew over the whole spectral range where measurements are taken (

Figure 7, right panel). Thus, the observed optical response can be explained with an enhanced electromagnetic response between the particles, that can be connected to the increase of particle density, but also by the formation of clusters and irregular structures, as reported in the morphological characterisation.

5. Conclusions

The initially deposited AuNPs were small, with sizes of about 10-20 nm. As a higher number of particles were deposited, larger particles were formed and grown through coalescence and aggregation.

The uniaxial anisotropic model showed better agreement with the ellipsometric measurement data compared to the isotropic model.

For all AuNPs` films a distanced peak at 2.2 eV can be observed in the imaginary part of the dielectric function that corresponds to the LSPR of a single AuNP.

The perpendicular effective dielectric function showed larger values than the effective parallel dielectric function.

The effective thickness from the ellipsometry measurements of the AuNPs` layer for samples deposited at 15, 30 and 60 min were 79, 97 and 110 nm.

The higher values of the transmittance and extinction cross-section are related to longer AuNPs` deposition times.

The enhanced electromagnetic response between AuNPs is associated with an increase in their density through the formation of clusters and irregular structures.

Funding

This research was funded by Norway Grants and a corresponding Slovenian contribution within the project: The Recycling of Rapid Antigen LFIA Tests (COVID-19) (LFIA-REC). This research was also funded by the Croatian Science Foundation through the grant number IP-2019-04-5424.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Amendola, V.; Pilot, R.; Frasconi, M.; Maragò, O.M.; Iatì, M.A. Surface plasmon resonance in gold nanoparticles: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 203002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petryayeva, E.; Krull, U.J. Localized surface plasmon resonance: Nanostructures, bioassays and biosensing—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 706, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Lee, K.S.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Calculated Absorption and Scattering Properties of Gold Nanoparticles of Different Size, Shape, and Composition: Applications in Biological Imaging and Biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7238–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.J. Foundations of Colloid Science; Oxford University Press: New York, 1995; ISBN 9780198505020. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, M.L.; Righini, M.; Quidant, R. Plasmon Nano-Optical Tweezers. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Review of Some Interesting Surface Plasmon Resonance-enhanced Properties of Noble Metal Nanoparticles and Their Applications to Biosystems. Plasmonics 2007, 2, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugunan, A.; Thanachayanont, C.; Dutta, J.; Hilborn, J.G. Heavy-metal ion sensors using chitosan-capped gold nanoparticles. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2005, 6, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, C. Detection of chemical pollutants in water using gold nanoparticles as sensors: a review. 2013, 32, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chah, S.; Hammond, M.R.; Zare, R.N. Gold Nanoparticles as a Colorimetric Sensor for Protein Conformational Changes. Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold nanoparticles: Optical properties and implementations in cancer diagnosis and photothermal therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2010, 1, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ali, M.R.K.; Chen, K.; Fang, N.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold nanoparticles in biological optical imaging. Nano Today 2019, 24, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, R.; Shao, M.; Zhuo, S.; Wen, C.; Wang, S.; Lee, S.-T. Highly Reproducible Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering on a Capillarity-Assisted Gold Nanoparticle Assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 3337–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Cronin, S.B. A Review of Surface Plasmon Resonance-Enhanced Photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghlara, H.; Rostami, R.; Maghoul, A.; SalmanOgli, A. Noble metal nanoparticle surface plasmon resonance in absorbing medium. Optik (Stuttg). 2015, 126, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, D.E.; Aherne, D.; Gara, M.; Ledwith, D.M.; Gun’ko, Y.K.; Kelly, J.M.; Blau, W.J.; Brennan-Fournet, M.E. Versatile Solution Phase Triangular Silver Nanoplates for Highly Sensitive Plasmon Resonance Sensing. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, E.E. Brownian movement and thermophoresis of nanoparticles in liquids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 81, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, B.; Aminossadati, S.M. Brownian motion of nanoparticles in a triangular enclosure with natural convection. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2010, 49, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential - What they are and what they are not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, R.I.; Napper, D.H. Depletion stabilization and depletion flocculation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980, 75, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkenschuh, E.; Friess, W. Freeze-drying of nanoparticles: How to overcome colloidal instability by formulation and process optimization. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 165, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beirowski, J.; Inghelbrecht, S.; Arien, A.; Gieseler, H. Freeze drying of nanosuspensions, 2: the role of the critical formulation temperature on stability of drug nanosuspensions and its practical implication on process design. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 4471–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelen, Ž.; Krajewski, M.; Zupanič, F.; Majerič, P.; Švarc, T.; Anžel, I.; Ekar, J.; Liou, S.-C.; Kubacki, J.; Tokarczyk, M.; et al. Melting point of dried gold nanoparticles prepared with ultrasonic spray pyrolysis and lyophilisation. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, R.; Majerič, P.; Štager, V.; Albreht, B. Process for the production of gold nanoparticles by modified ultrasonic spray pyrolysis: patent application no. P-202000079; Office of the Republic of Slovenia for Intellectual Property: Ljubljana, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho-Parramon, J.; Okorn, B.; Salamon, K.; Janicki, V. Plasmonic resonances in copper island films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 463, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Parramon, J.; Janicki, V.; Zorc, H. Tuning the effective dielectric function of thin film metal-dielectric composites by controlling the deposition temperature. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3590238 2011, 5, 051805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedl, E.; Bregović, V.B.; Rakić, I.Š.; Mandić, Š.; Samec, Ž.; Bergmann, A.; Sancho-Parramon, J. Optical properties of annealed nearly percolated Au thin films. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 2023, 135, 113237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Galván, A.; Järrendahl, K.; Dmitriev, A.; Pakizeh, T.; Käll, M.; Arwin, H. Optical response of supported gold nanodisks. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 12093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubaš, M.; Fabijanić, I.; Kenđel, A.; Miljanić, S.; Spadaro, M.C.; Arbiol, J.; Janicki, V.; Sancho-Parramon, J. Unifying stability and plasmonic properties in hybrid nanoislands: Au–Ag synergistic effects and application in SERS. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2023, 380, 133326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).