Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

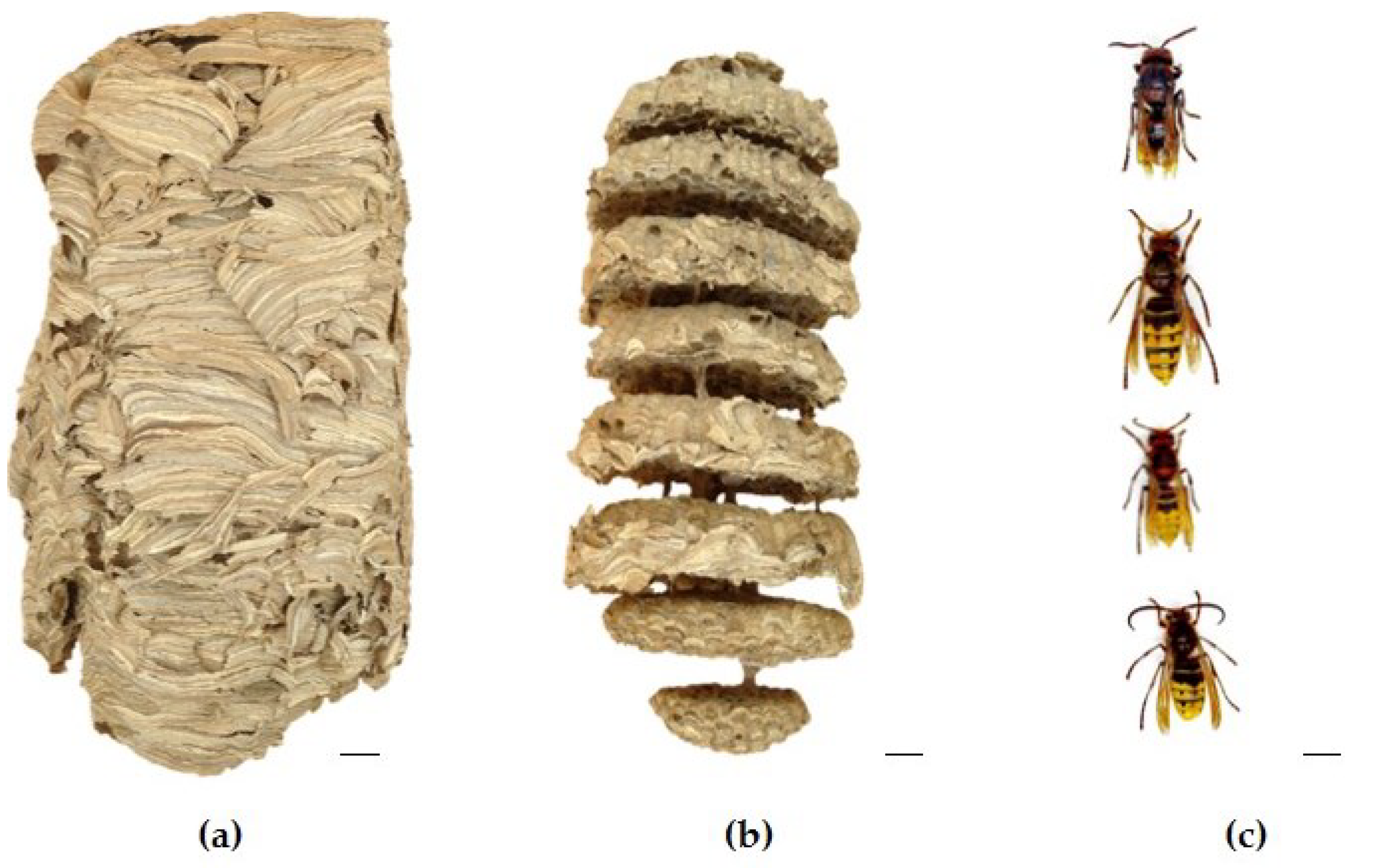

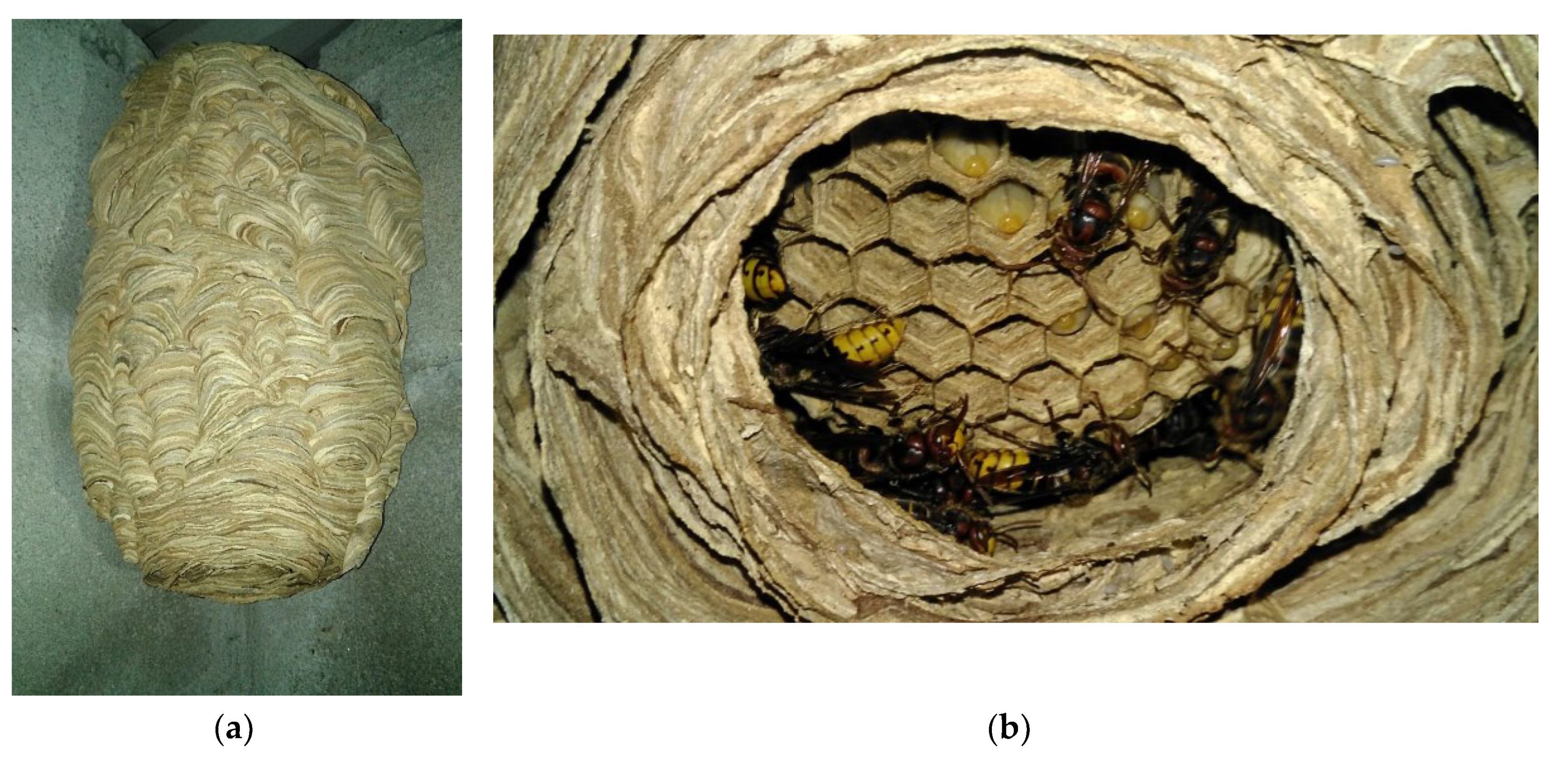

2.1. Source of Insects: the Nest and Colony Composition

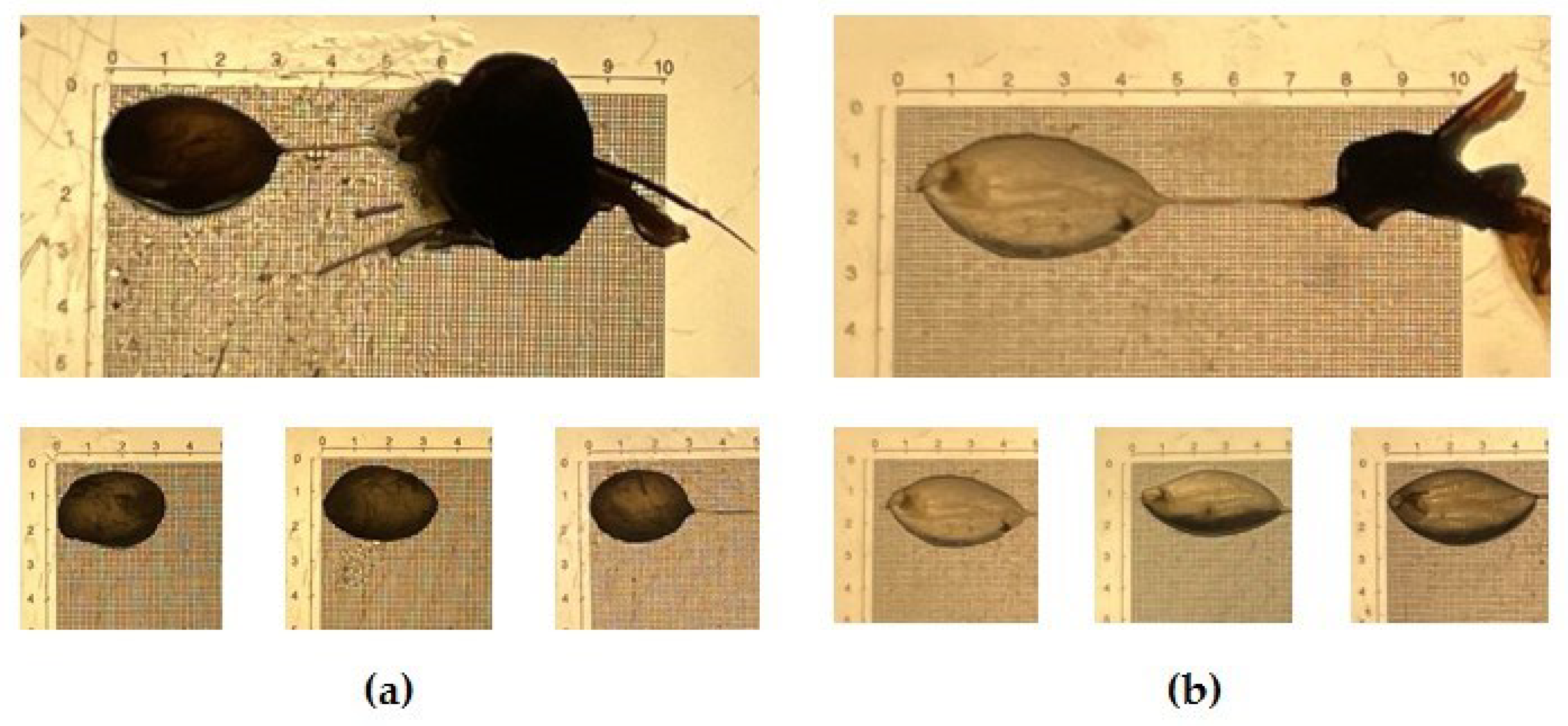

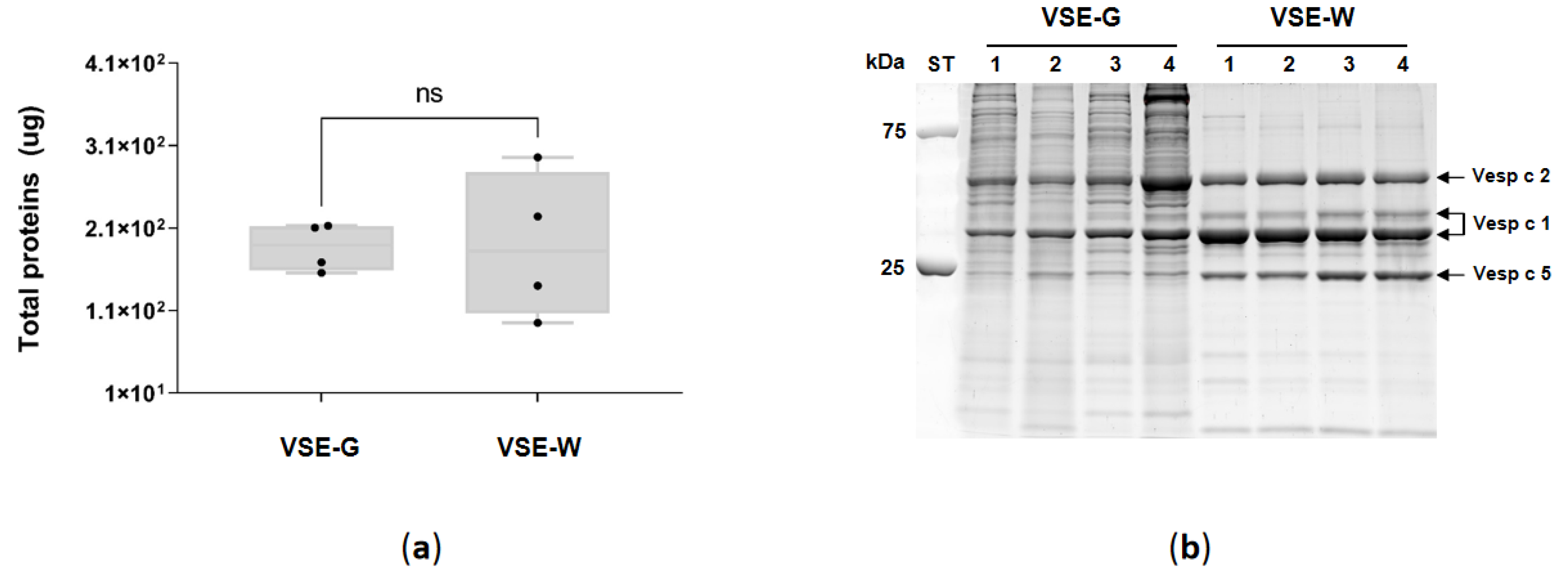

2.2. Venom Sac, Extract Protein Quantitation and SDS-PAGE.

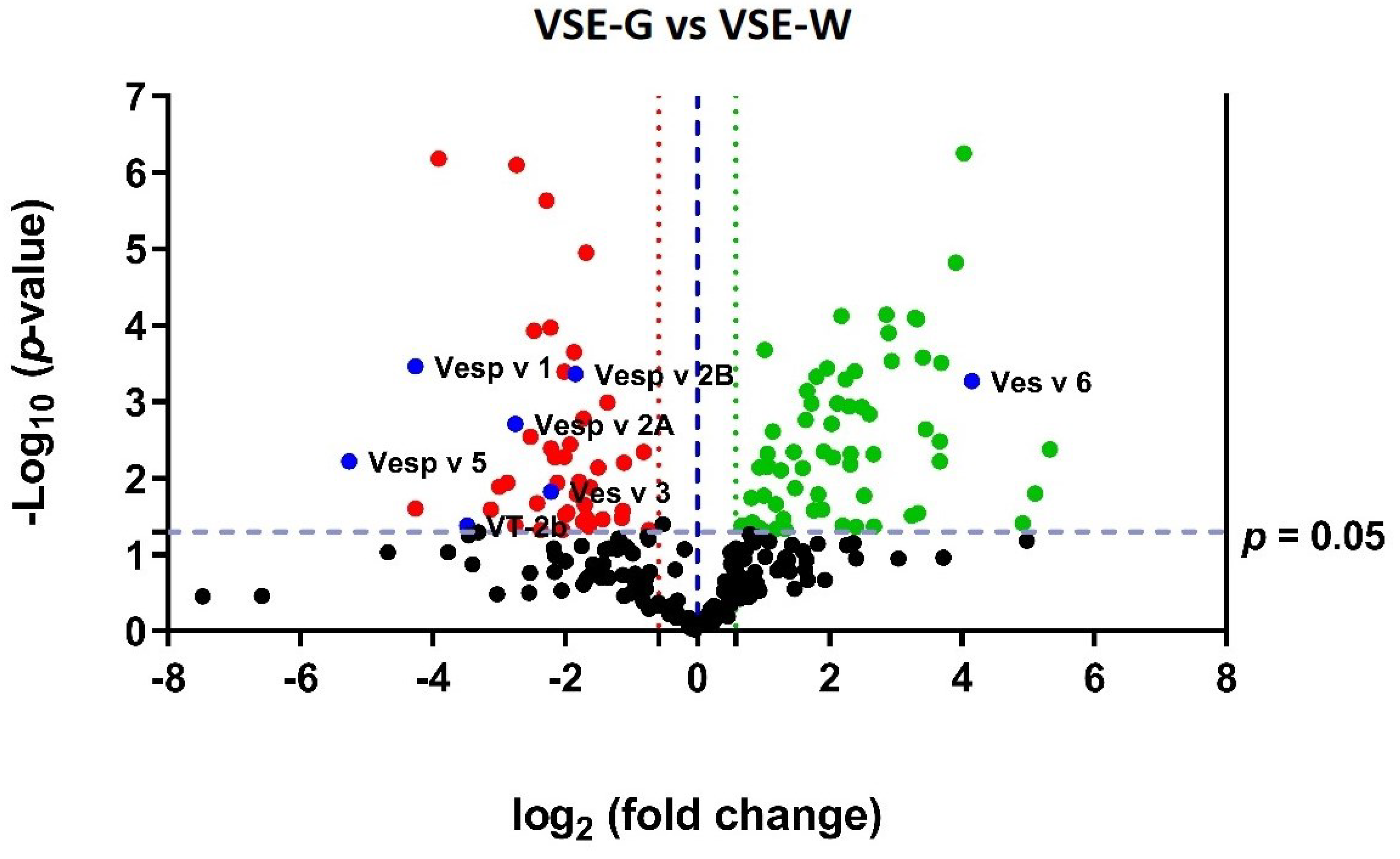

2.3. Proteomic Quantitative Analysis of Total Proteins in the Venom Sac Extract

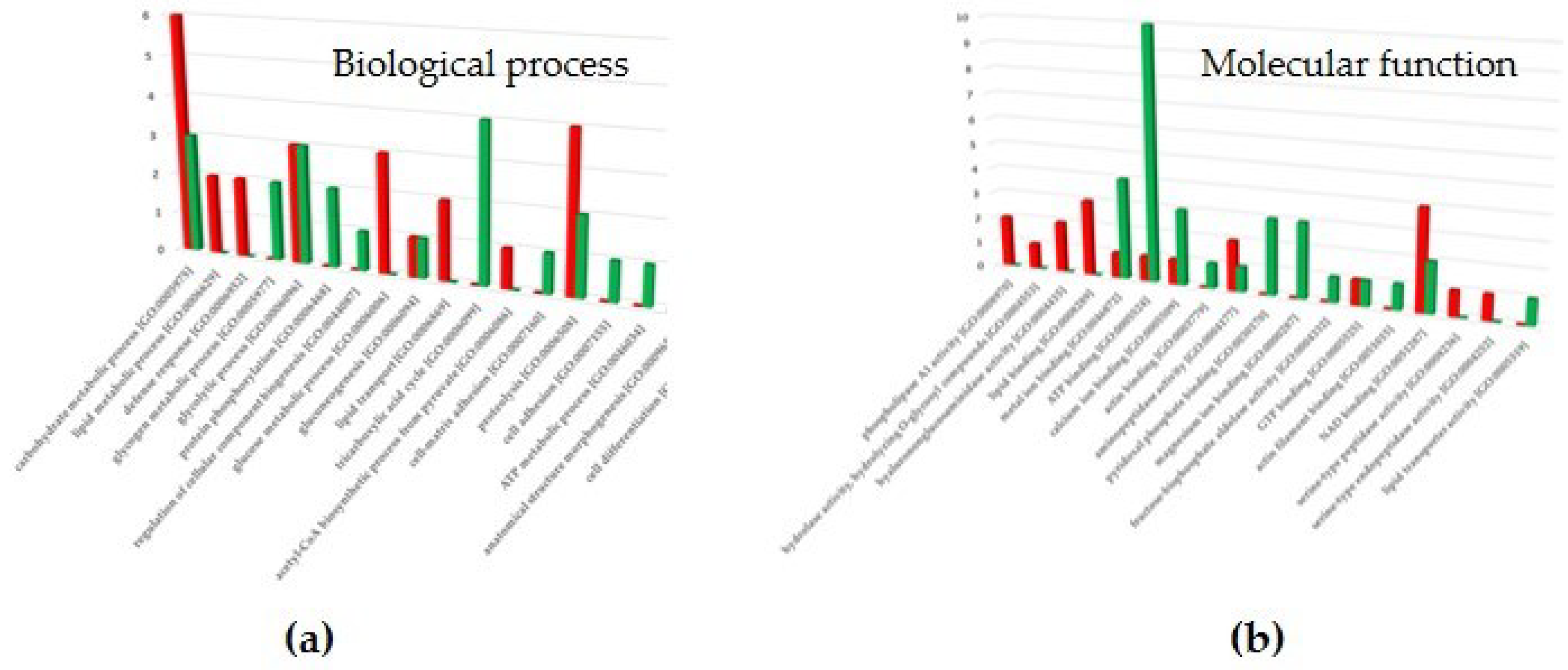

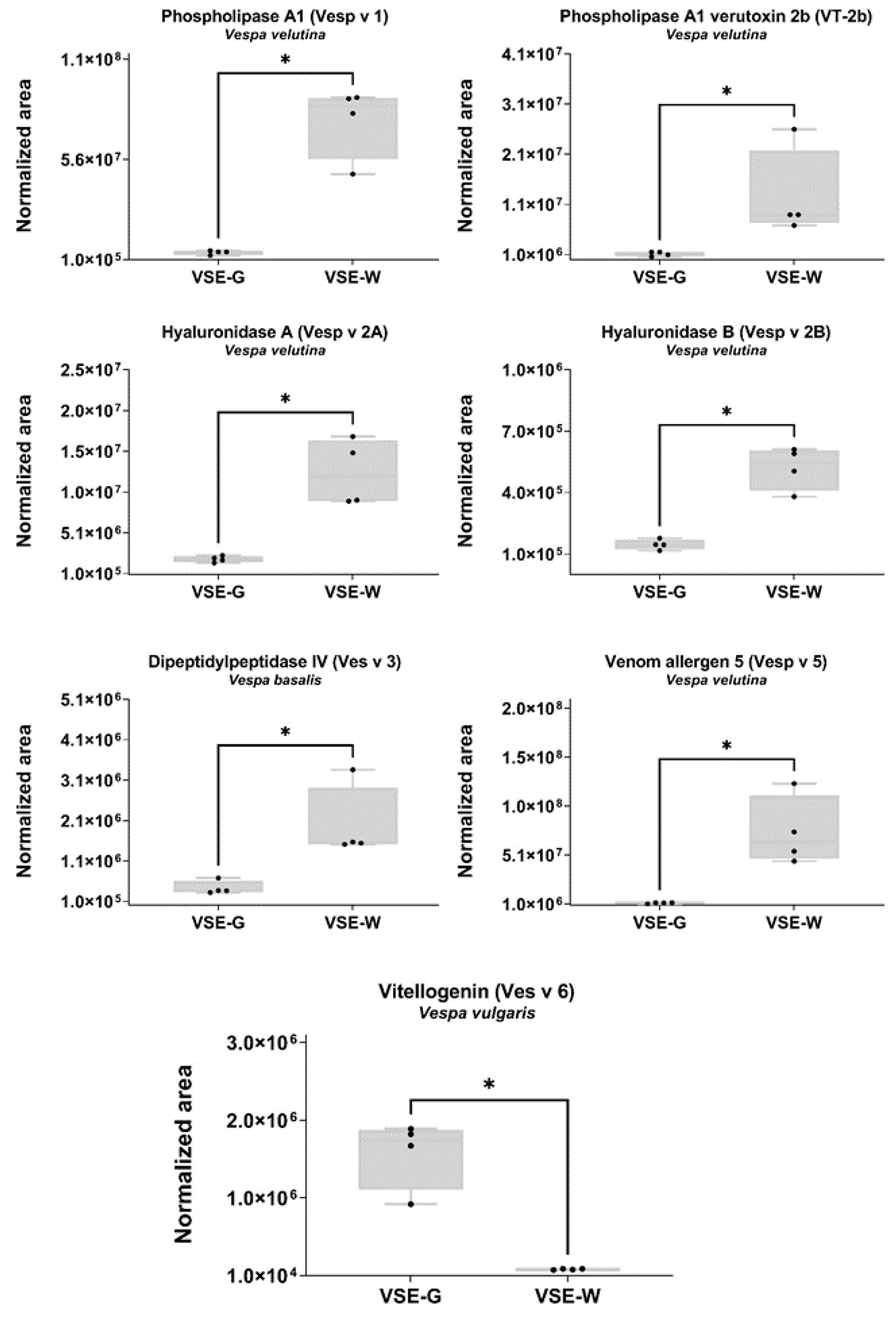

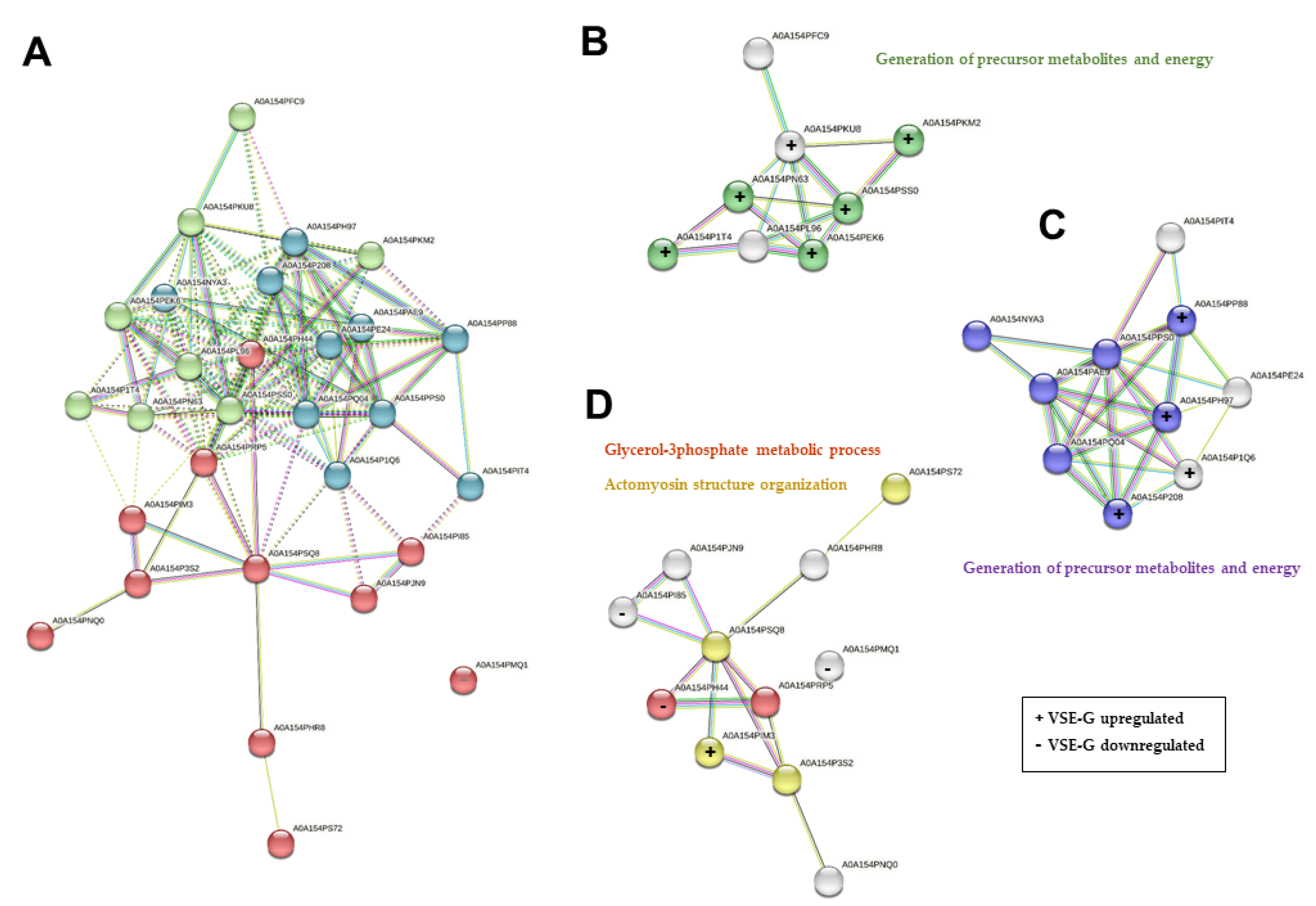

2.4. Proteomic Quantitative Analysis from Dysregulated Proteins of the Class Insecta.

2.5. Proteomic Quantitative Analysis from Dysregulated Proteins of the Other Classes.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Source of Insects

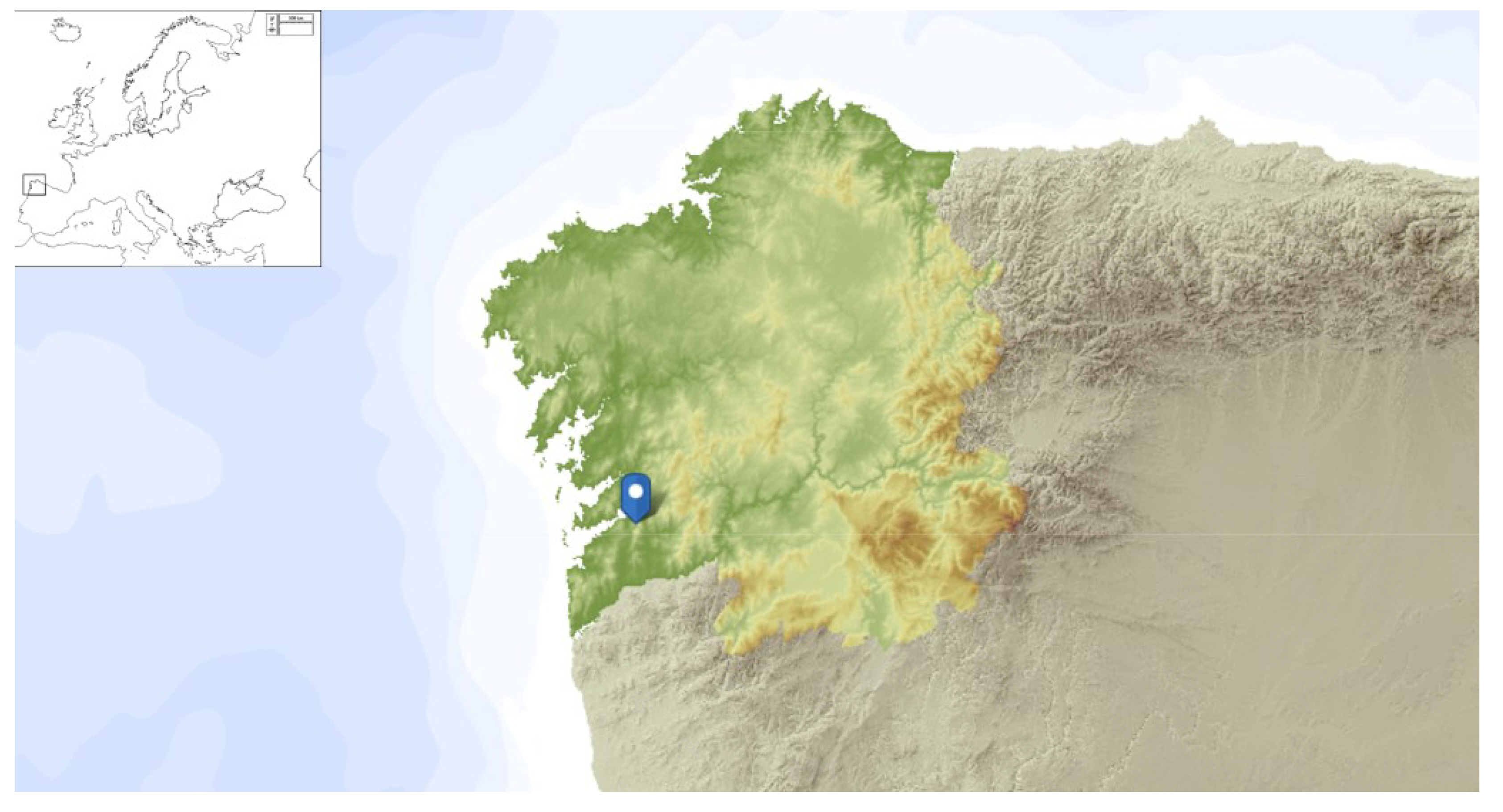

4.1.1. Study Area

4.1.2. Insect Localization and Identification

4.1.3. Identification. Tracking and Locating Nest of Target Species

4.1.4. Nest removal

4.1.5. Nest Colony Composition and Determining Sex

4.2. Venom Sac Extract Obtention

4.3. Venom Sac Extract Protein Quantitation

4.4. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

4.5. Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Quantification Using Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH-MS)

4.6. Protein Functional Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, J. Venomous animals: Clinical toxinology. In: Luch A, editor. Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology. Birkhäuser Verlag AG, 2010. p. 233–291. [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M.A.; Gupta, S.; Dora, C.P.; et al. Venoms classification and therapeutic uses: A narrative review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 1633–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelsen, D.R.; Nisani, Z.; Cooper, A.M.; Fox, G.A.; Gren, E.C.; Corbit, A.G.; Hayes, W.K. Poisons, toxungens, and venoms: Redefining and classifying toxic biological secretions and the organisms that employ them. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2014, 89, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Aziz, T.M.; Soares, A.G.; Stockand, J.D. Advances in venomics: Modern separation techniques and mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020, 1160, 122352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, J.J. Venomics: Integrative venom proteomics and beyond. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaas, Q.; Craik, D.J. Bioinformatics-Aided Venomics. Toxins 2015, 7, 2159–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, A.; Needham, K.; Bennett, A.M.R. First record of Vespa crabro Linnaeus (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in western North America with a review of recorded species of Vespa Linnaeus in Canada. Zootaxa 2022, 5154, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetsun, H.A.; Matushkina, N.A. Sting morphology of the European hornet, Vespa crabro L., (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) re-examined. Entomol. Sci. 2020, 23, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzen, R.; Koren, A.; Selb, J.; Bajrovic, N.; Lalek, N.; Kopac, P.; Zidarn, M.; Korosec, P.; Kosnik, M. Clinical, serological and basophil response to a wasp sting in patients with European hornet sting anaphylaxis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 1641–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.S.; Hoffman, D.R. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) an emerging sting problem in the eastern U.S. J. Allergy Clin. Immunolog. 1985, 75, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosnik, M.; Korosec, P.; Silar, M.; Music, E.; Erzen, R. Wasp venom is appropriate for immunotherapy of patients with allergic reaction to the European hornet sting. Croat. Med. J. 2002, 43, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Macchia, D.; Cortellini, G.; Mauro, M.; Meucci, E.; Quercia, O.; Manfredi, M.; Massolo, A.; Valentini, M.; Severino, M.; Passalacqua, G. Vespa crabro immunotherapy versus Vespula-venom immunotherapy in Vespa crabro allergy: A comparison study in field re-stings. World Allergy Organ. J. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, S.; Bazon, M.L.; Grosch, J.; Schmidt-Weber, C.B.; Brochetto-Braga, M.R.; Bilò, M.B.; Jakob, T. Antigen 5 Allergens of Hymenoptera Venoms and Their Role in Diagnosis and Therapy of Venom Allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzani, R.; Blanca, M.; Sánchez, F.; Juarez, C. Sensitivity to European wasps in a group of allergic patients in Marseille: Preliminary results. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 1994, 4, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Severino, M.G.; Caruso, B.; Bonadonna, P.; Labardi, D.; Macchia, D.; Campi, P.; Passalacqua, G. Cross reactivity between European hornet and yellow jacket venoms. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 42, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korantzopoulos, P.; Kountouris, E.; Voukelatou, M.; Charaktsis, I.; Dimitroula, V.; Siogas, K. Acute myocardial infarction after a European hornet sting--a case report. Angiology 2006, 57, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubrano, D.; Helias, P.; Bach, P.; Leclercq, M.; Fillet, G.; Lecomte, J.; Damas, J. [Case of fatal poisoning with hyperfibrinolysis by multiple wasp stings (Vespa crabro L.)]. Rev. Med. Liege 1985, 40, 844–846. [Google Scholar]

- Okutucu, S.; Sabanov, C.; Abdulhayoğlu, E.; Aksu, N.M.; Erbil, B.; Aytemir, K.; Ozkutlu, H. A rare cause of atrial fibrillation: A European hornet sting. Anadolu. Kardiyol. Derg. 2011, 11, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggese, S. A new fatal case of Vespa crabro sting. Nuovi Ann. Ig. Microbiol. 1956, 7, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antonicelli, L.; Bilò, M.B.; Napoli, G.; Farabollini, B.; Bonifazi, F. European hornet (Vespa crabro) sting: A new risk factor for life-threatening reaction in hymenoptera allergic patients? Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 35, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Baek, J.H.; Yoon, K.A. Differential Properties of Venom Peptides and Proteins in Solitary vs. Social Hunting Wasps. Toxins 2016, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashevsky, D.; Baumann, K.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Nouwens, A.; Ikonomopoulou, M.P.; Schmidt, J.O.; Ge, L.; Kwok, H.F.; Rodriguez, J.; Fry, B.G. Functional and Proteomic Insights into Aculeata Venoms. Toxins 2023, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumari, V.; Nagaraj, R. Antimicrobial and hemolytic activities of crabrolin, a 13-residue peptide from the venom of the European hornet, Vespa crabro, and its analogs. J. Pept. Res. 1997, 50, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argiolas, A.; Pisano, J.J. Isolation and characterization of two new peptides, mastoparan C and crabrolin, from the venom of the European hornet, Vespa crabro. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 10106–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Xi, X.; Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Shaw, C.; Chen, T.; Zhou, M. Evaluation of the bioactivity of a mastoparan peptide from wasp venom and of its analogues designed through targeted engineering. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.A.; Kim, K.; Nguyen, P.; Seo, J.B.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, K.; Seo, H.; Koh, Y.; Lee, S.H. Comparative bioactivities of mastoparans from social hornets Vespa crabro and Vespa analis. J. Asia-Pac Entomol. 2015, 18, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allalouf, D.; Ber, A.; Ishay, J. Hyaluronidase activity of extracts of venom sacs of a number of vespinae (Hymenoptera). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1972, 43, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.R.; Jacobson, R.S.; Zerboni, R. Allergens in hymenoptera venom. XIX. Allergy to Vespa crabro, the European hornet. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1987, 84, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, D.R. Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XXV: The amino acid sequences of antigen 5 molecules and the structural basis of antigenic cross-reactivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1993, 92, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.A.; Kim, K.; Nguyen, P.; Seo, J.B.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, K.G.; Seo, H.-Y.; Koh, Y.H.; Lee, S.H. Comparative functional venomics of social hornets Vespa crabro and Vespa analis. J. Asia-Pac Entomol. 2015, 18, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, U.; Elliott, W.; Reisman, R.; Ishay, J.; Walsh, S.; Steger, R.; Wypych, J.; Arbesman, C. Comparison of biochemical and immunologic properties of venoms from four hornet species. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1981, 67, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turillazzi, S.; Bruschini, C.; Lambardi, D.; Francese, S.; Spadolini, I.; Mastrobuoni, G. Comparison of the medium molecular weight venom fractions from five species of common social wasps by MALDI-TOF spectra profiling. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.A.; Kim, K.; Kim, W.J.; Bang, W.Y.; Ahn, N.H.; Bae, C.H.; Yeo, J.H.; Lee, S.H. Characterization of Venom Components and Their Phylogenetic Properties in Some Aculeate Bumblebees and Wasps. Toxins 2020, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.A.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, S.H. Expression profiles of venom components in some social hymenopteran species over different post-capture periods. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 253, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Sampedro, M.; Feás, X.; Bravo, S.B.; Chantada-Vázquez, M.P.; Vidal, C. Proteomics of Vespa velutina nigrithorax Venom Sac Queens and Workers: A Quantitative SWATH-MS Analysis. Toxins 2023, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotello, R.J.; Veenstra, T.D. Mass Spectrometry Techniques: Principles and Practices for Quantitative Proteomics. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2021, 22, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.; Gillet, L.; Rosenberger, G.; Amon, S.; Collins, B.C.; Aebersold, R. Data-independent acquisition-based SWATH-MS for quantitative proteomics: A tutorial. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishay, J.; Shved, A.; Gitter, S. Lethality of venom sac extracts of the oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis) as related to ontogenesis. Toxicon. 1977, 15, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Da Silva, D.; Colas, C.; Darrouzet, E.; Baril, P.; Leseurre, L.; Maunit, B. Asian hornet Vespa velutina nigrithorax venom: Evaluation and identification of the bioactive compound responsible for human keratinocyte protection against oxidative stress. Toxicon 2020, 176, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koludarov, I.; Velasque, M.; Timm, T.; Greve, C.; Ben Hamadou, A.; Kumar Gupta, D.; Lochnit, G.; el Heinzinger, M.; Vilcinskas, A.; Gloag, R.; et al. A common venomous ancestor? Prevalent bee venom genes evolved before the aculeate stinger while few major toxins are bee-specific. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Morales, V.; Summers, K. A key ecological trait drove the evolution of biparental care and monogamy in an amphibian. Am. Nat. 2010, 175, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, P.H.; Ma, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Ye, W.-G.; Diao, K.-Y.; Dai, P.L. Midgut Bacterial Communities of Vespa velutina Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 934054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenami, S.; Konishi, N.M.; Miyazaki, R. Community analysis of gut microbiota in hornets, the largest eusocial wasps, Vespa mandarinia and V. simillima. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, A.; Meriggi, N.; Bacci, G.; Cappa, F.; Vitali, F.; Cavalieri, D.; Cervo, R. Gut microbial composition in different castes and developmental stages of the invasive hornet Vespa velutina nigrithorax. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantawannakul, P.; Ramsey, S.; vanEngelsdorp, D.; Khongphinitbunjong, K.; Phokasem, P. Tropilaelaps mite: An emerging threat to European honey bee. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feás, X.; Vidal, C.; Remesar, S. What We Know about Sting-Related Deaths? Human Fatalities Caused by Hornet, Wasp and Bee Stings in Europe (1994–2016). Biology 2022, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feás, X. Human Fatalities Caused by Hornet, Wasp and Bee Stings in Spain: Epidemiology at State and Sub-State Level from 1999 to 2018. Biology 2021, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C. The Asian wasp Vespa velutina nigrithorax: Entomological and allergological characteristics. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feás, X.; Vázquez-Tato, M.P.; Seijas, J.A.; Pratima GNikalje, A.; Fraga-López, F. Extraction and Physicochemical Characterization of Chitin Derived from the Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina Lepeletier 1836 (Hym.: Vespidae). Molecules 2020, 25, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feás Sánchez, X.; Charles, R.J. Notes on the nest architecture and colony composition in winter of the yellow-legged Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina Lepeletier 1836 (Hym.: Vespidae), in its introduced habitat in Galicia (NW Spain). Insects 2019, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feás, X.; Vidal, C.; Vázquez-Tato, M.P.; Seijas, J.A. Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina Lepeletier 1836 (Hym.: Vespidae), Venom Obtention Based on an Electric Stimulation Protocol. Molecules 2021, 27, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, C.; Armisén, M.; Monsalve, R.; Gómez-Rial, J.; González-Fernández, T.; Carballada, F.; Lombardero, M.; González-Quintela, A. Vesp v 5 and glycosylated Vesp v 1 are relevant allergens in Vespa velutina nigrithorax anaphylaxis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2020, 50, 1424–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, C.; Armisén, M.; Monsalve, R.; González-Vidal, T.; Lojo, S.; López-Freire, S.; Méndez, P.; Rodríguez, V.; Romero, L.; Galán, A.; et al. Anaphylaxis to Vespa velutina nigrithorax: Pattern of Sensitization for an Emerging Problem in Western Countries.J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 31, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, V.; Gómez-Rial, J.; Monsalve, R.I.; Vidal, C. Consistency of Determination of sIgE and the Basophil Activation Test in Vespa velutina nigrithorax Allergy. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 32, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, V.; Armisén, M.; Gómez-Rial, J.; Lamas-Vázquez, B.; Vidal, C. Immunotherapy with Vespula venom for Vespa velutina nigrithorax anaphylaxis: Preliminary clinical and immunological results. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Leon, B.; Serrano, P.; Vidal, C.; Moreno-Aguilar, C. Management of Double Sensitization to Vespids in Europe. Toxins 2022, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñas-Martínez, J.; Barrachina, M.N.; Cuenca-Zamora, E.J.; Luengo-Gil, G.; Bravo, S.B.; Caparrós-Pérez, E.; Teruel-Montoya, R.; Eliseo-Blanco, J.; Vicente, V.; García, Á.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative comparison of plasma exosomes from neonates and adults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, T.; Lago-Baameiro, N.; Sueiro, A.; Bravo, S.B.; Couto, I.; Santos, F.F.; Teruel-Montoya, R.; Eliseo-Blanco, J.; Vicente, V.; García, Á.; et al. Brown Adipose Tissue Sheds Extracellular Vesicles That Carry Potential Biomarkers of Metabolic and Thermogenesis Activity Which Are Affected by High Fat Diet Intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantada-Vázquez, M.D.P.; Conde-Amboage, M.; Graña-López, L.; Vázquez-Estévez, S.; Bravo, S.B.; Núñez, C. Circulating Proteins Associated with Response and Resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Order | Family | Scientific name | Common name | nº | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinopterygii | Cyprinodontiformes | Nothobranchiidae | Nothobranchius furzeri (Jubb, 1971) | African Turquoise killifish | 1 | NOTFU |

| Perciformes | Siganidae | Siganus canaliculatus (Park, 1797) | White-spotted spinefoot | 1 | SIGCA | |

| Amphibia | Anura | Dendrobatidae | Ranitomeya imitator (Schulte, 1986) | Mimic poison frog | 17 | 9NEOB |

| Arachnida | Mesostigmata | Laelapidae | Tropilaelaps mercedesae (Delfinado & Baker, 1961) | Tropilaelaps mite | 2 | 9ACAR |

| Scorpiones | Buthidae | Centruroides hentzi (Banks, 1940) | Hentz striped scorpion | 2 | 9SCOR | |

| Caraboctonidae | Hadrurus spadix (Stahnke, 1940) | Black back scorpion | 1 | |||

| Bacilli | Lactobacillales | Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus apis (Killer et al. 2014) | Lactic acid bacteria | 1 | 9LACO |

| Streptococcaceae | Lactococcus lactis (Lister 1873) Schleifer et al. 1986 | Lactic acid bacteria | 1 | 9LACT | ||

| Clitellata | Rhynchobdellida | Glossiphoniidae | Helobdella robusta (Shankland, Bissen & Weisblat, 1992) | Californian leech | 1 | HELRO |

| Insecta | Coleoptera | Ptilodactylidae | Anchycteis velutina (Horn, 1880) | Toe-winged beetle | 1 | |

| Hymenoptera | Apidae | Apis cerana (Fabricius, 1793) | Asian honey bee | 31 | APICE | |

| Apis cerana subsp. cerana (Fabricius, 1793) | Asian honey bee | 4 | APICC | |||

| Apis cerana subsp. indica (Fabricius, 1793) | Indian honey bee | 1 | ||||

| Apis mellifera (Linnaeus, 1758) | European honey bee | 41 | APIME | |||

| Apis mellifera ligustica (Spinola, 1806) | Italian honey bee | 2 | APILI | |||

| Bombus festivus(Smith, 1861) | Bumblebee of Sichuan | 1 | ||||

| Bombus humilis(Illiger, 1806) | Brown-banded carder bumblebee | 1 | BOMHU | |||

| Bombus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1758) | Buff-tailed bumblebee | 44 | BOMTE | |||

| Frieseomelitta varia(Lepeletier, 1836) | Yellow marmalade bee | 28 | 9HYME | |||

| Halictidae | Agapostemon leunculus (Vachal, 1903) | Sweat bee | 1 | 9COLE | ||

| Dufourea novaeangliae (Robertson, 1897) | Sweat bee | 29 | DUFNO | |||

| Vespidae | Vespa basalis (Smith, 1852) | Black-bellied hornet | 1 | VESBA | ||

| Vespa crabro (Linnaeus, 1758) | European hornet | 1 | VESCR | |||

| Vespa magnifica (Smith, 1852) | Magnifica hornet | 1 | VESMG | |||

| Vespa mandarinia (Smith, 1852) | Northern giant hornet | 1 | ||||

| Vespa mandarinia subsp. Japonica (Smith, 1852) | Northern giant hornet | 1 | VESMA | |||

| Vespa simillima subsp. xanthoptera (Cameron, 1903) | Yellow hornet | 4 | VESXA | |||

| Vespa velutina (Lepeletier, 1836) | Yellow-legged Asian hornet | 6 | VESVE | |||

| Vespula vulgaris(Linnaeus, 1758) | Common wasp | 1 | VESVU | |||

| Mammalia | Primates | Hominidae | Homo sapiens (Linnaeus, 1758) | Human | 2 | HUMAN |

| Microsporidia | Nosematida | Nosematidae | Nosema apis (Zander 1909) | Nosema | 1 | 9MICR |

| Pisoniviricetes | Picornavirales | Iflaviridae | Deformed wing virus | Deformed wing virus | 1 | 9VIRU |

| Reptilia | Squamata | Viperidae | Crotalus adamanteus (Palisot de Beauvois, 1799) | Eastern diamondback rattlesnake | 1 | CROAD |

| γ-proteobacteria | Enterobacterales | Enterobacteriaceae | Klebsiella sp. RIT-PI-d | Klebsiella | 1 | 9ENTR |

| Cronobacter sakazakii (Farmer et al. 1980) Iversen et al. 2007. | Cronobacter | 1 | CROSK | |||

| Citrobacter freundii (Braak 1928) Werkman & Gillen 1932 | Citrobacter | 1 | CITFR | |||

| Escherichia coli (Migula 1895)Castellani & Chalmers 1919 | coli | 5 | ECOLX |

| Family/Protein | Uniprot code | Specie | P Value (t test) | FC (VSE-G/VSE-W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldo-keto reductase/alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP(+)) | J3SBS4 | adamanteus | < 0.001 | 16.364 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase/Multifunctional fusion protein | A0A1W7RAT0 | H. spadix | 0.007 | 4.969 |

| Heat shock protein/Heat shock 70 kDa protein | A0A2I9LP41 | C. hentzi | 0.004 | 2.081 |

| Intermediate filament/hypothetical protein | A0A822AXZ5 | R. imitator | 0.027 | 0.458 |

| Transferrin/Serotransferrin | A0A822GLX5 | R. imitator | 0.011 | 0.289 |

| Apolipoprotein A1/A4/E/hypothetical protein | A0A822ID78 | R. imitator | 0.004 | 0.216 |

| A0A821UX93 | imitator | 0.006 | 0.465 | |

| Peptidase/Proteasome subunit alpha type | A0A821TAG2 | R. imitator | < 0.001 | 0.313 |

| Globin/hypothetical protein | A0A822FRT2 | R. imitator | 0.004 | 0.265 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | A0A0A5SYN4 | C. freundii | 0.002 | 0.174 |

| A0A821LTU2 | R. imitator | 0.011 | 0.231 | |

| Lpp/Major outer membrane lipoprotein Lpp | A0A0L0AQN9 | Klebsiella sp. | 0.048 | 0.243 |

| Thioredoxin /Thioredoxin | W8TGE9 | E. coli | < 0.001 | 0.214 |

| No family described/Enolase | K4WKC0 | E. coli | 0.005 | 0.247 |

| No family described/TetR family transcriptional regulator | A0A1C4ADY6 | L. apis | < 0.001 | 0.180 |

| No family described/IgG H chain | S6B291 | H. sapiens | < 0.001 | 0.247 |

| No family described/Ig-like domain-containing protein | Q8TCD0 | H. sapiens | 0.007 | 0.353 |

| No family described/hypothetical protein | A0A822HYL0 | R. imitator | 0.005 | 0.571 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).