Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

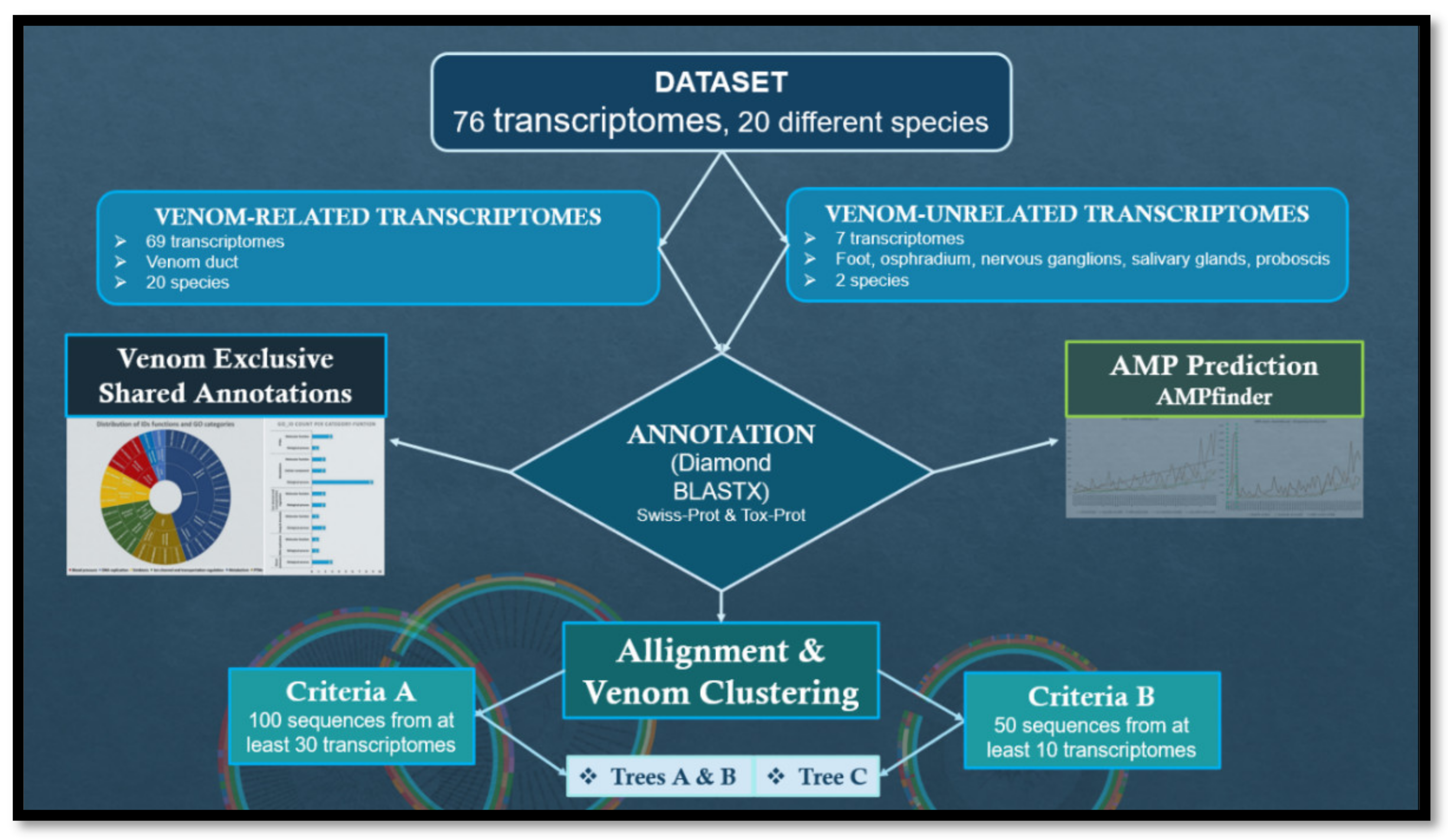

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Criteria A: 100 sequences from at least 30 transcriptomes; the selected sequences would be further annotated according to the database of Tox-Prot;

- -

- Criteria B: 50 sequences from at least 10 transcriptomes; the selected sequences would be further annotated according to the database of UniProt-Trembl.

3. Results

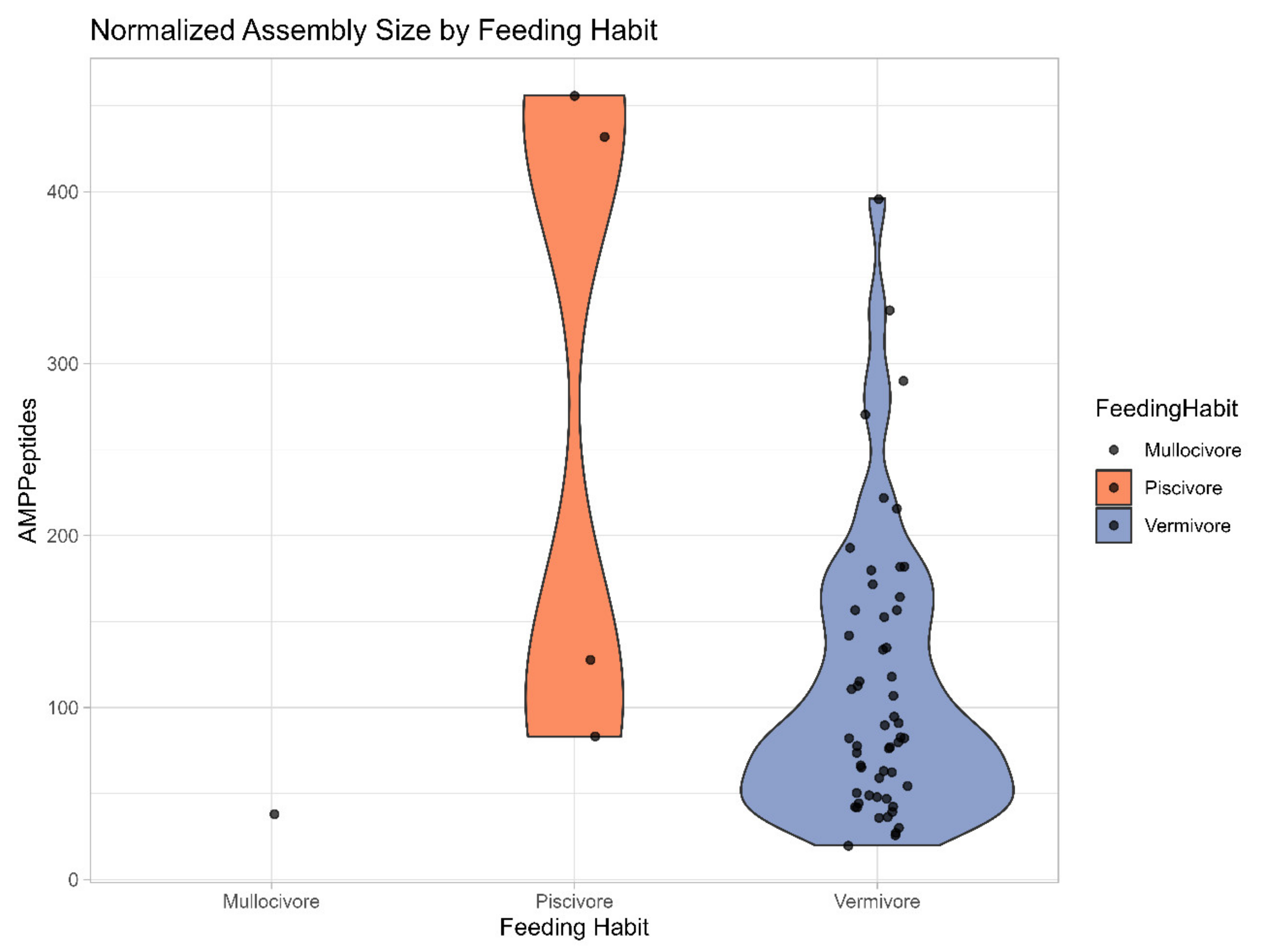

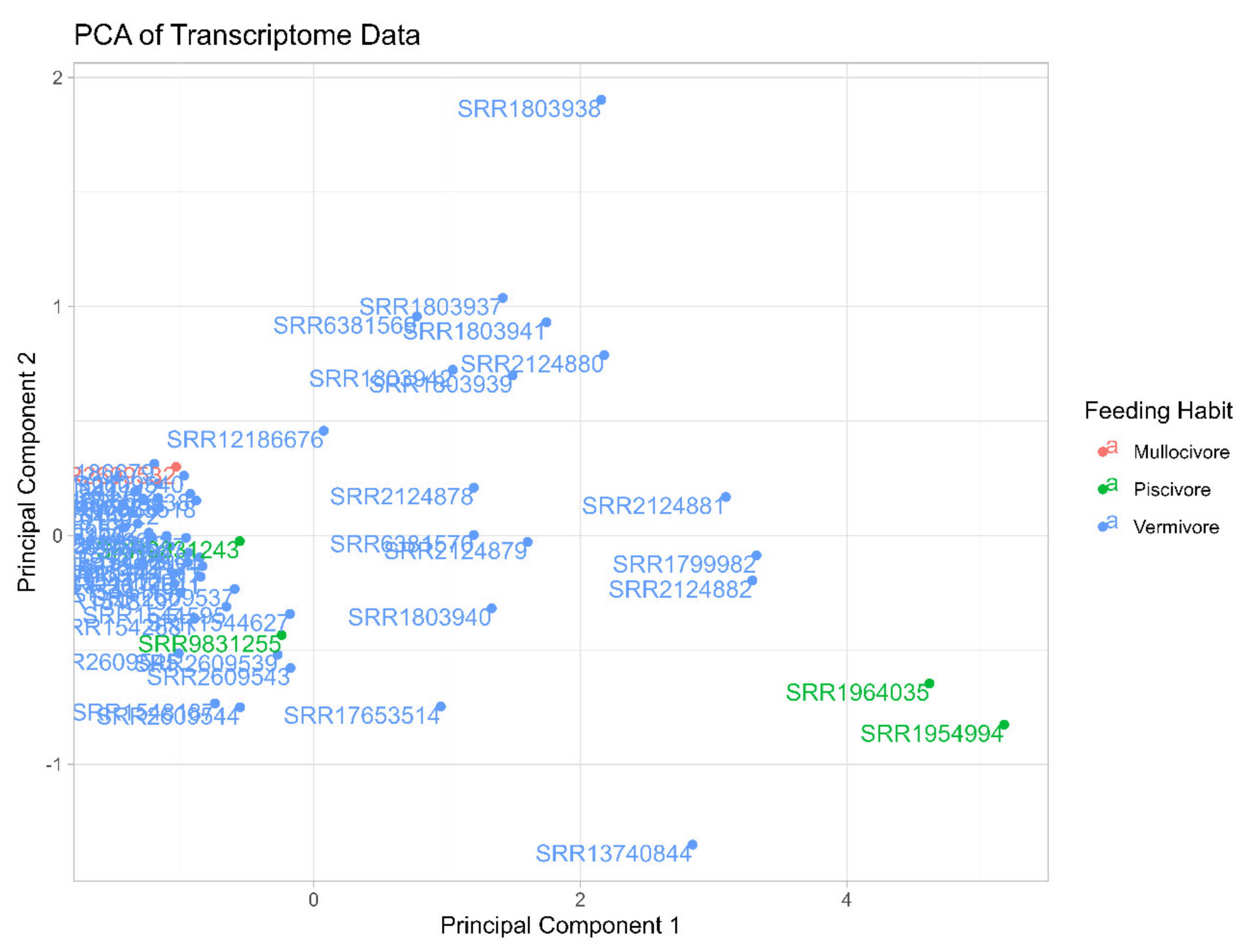

3.1. General Transcriptomes Annotation and Biomedical Predictions

3.2. Shared Transcriptomic Repertoire

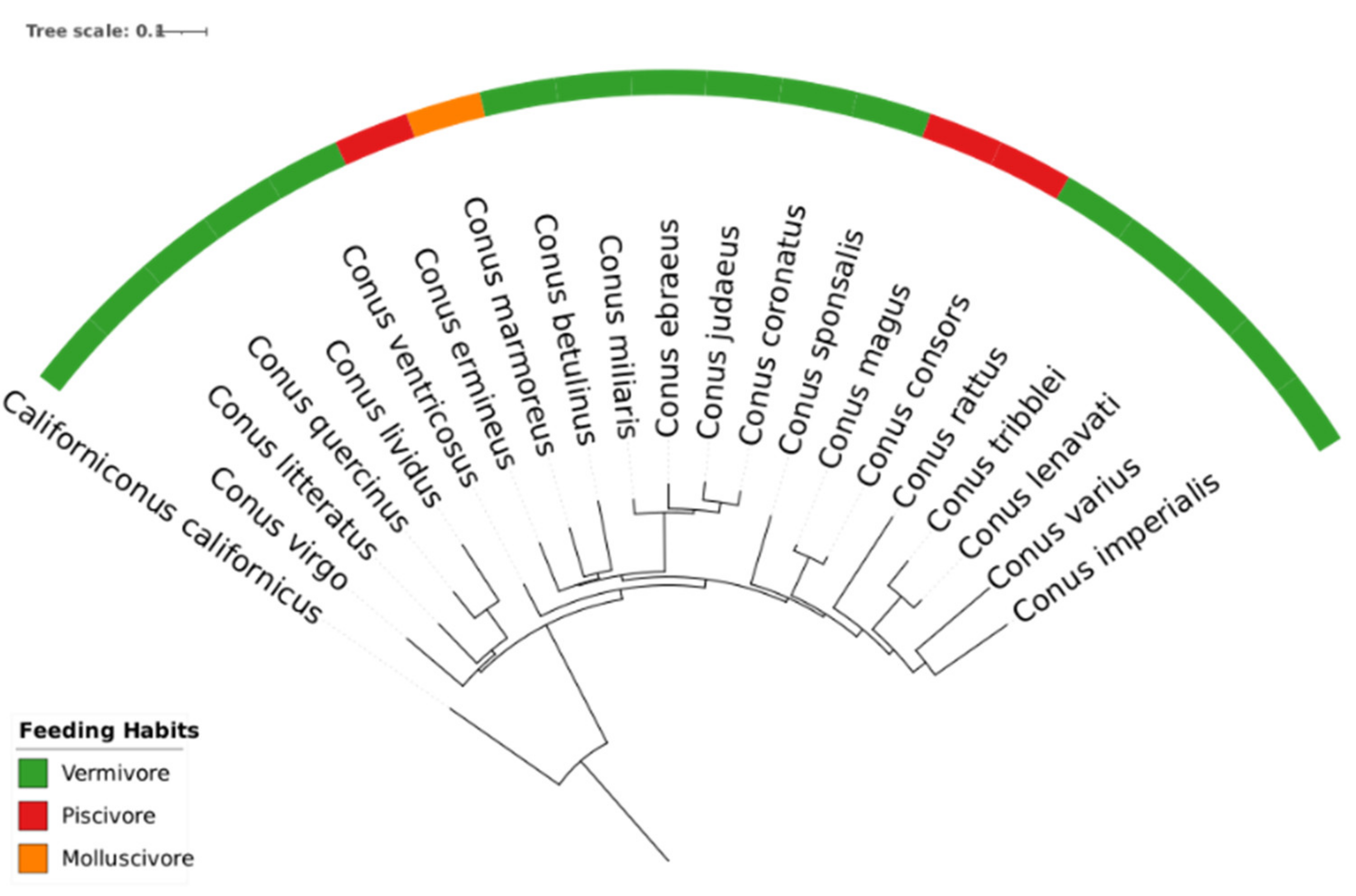

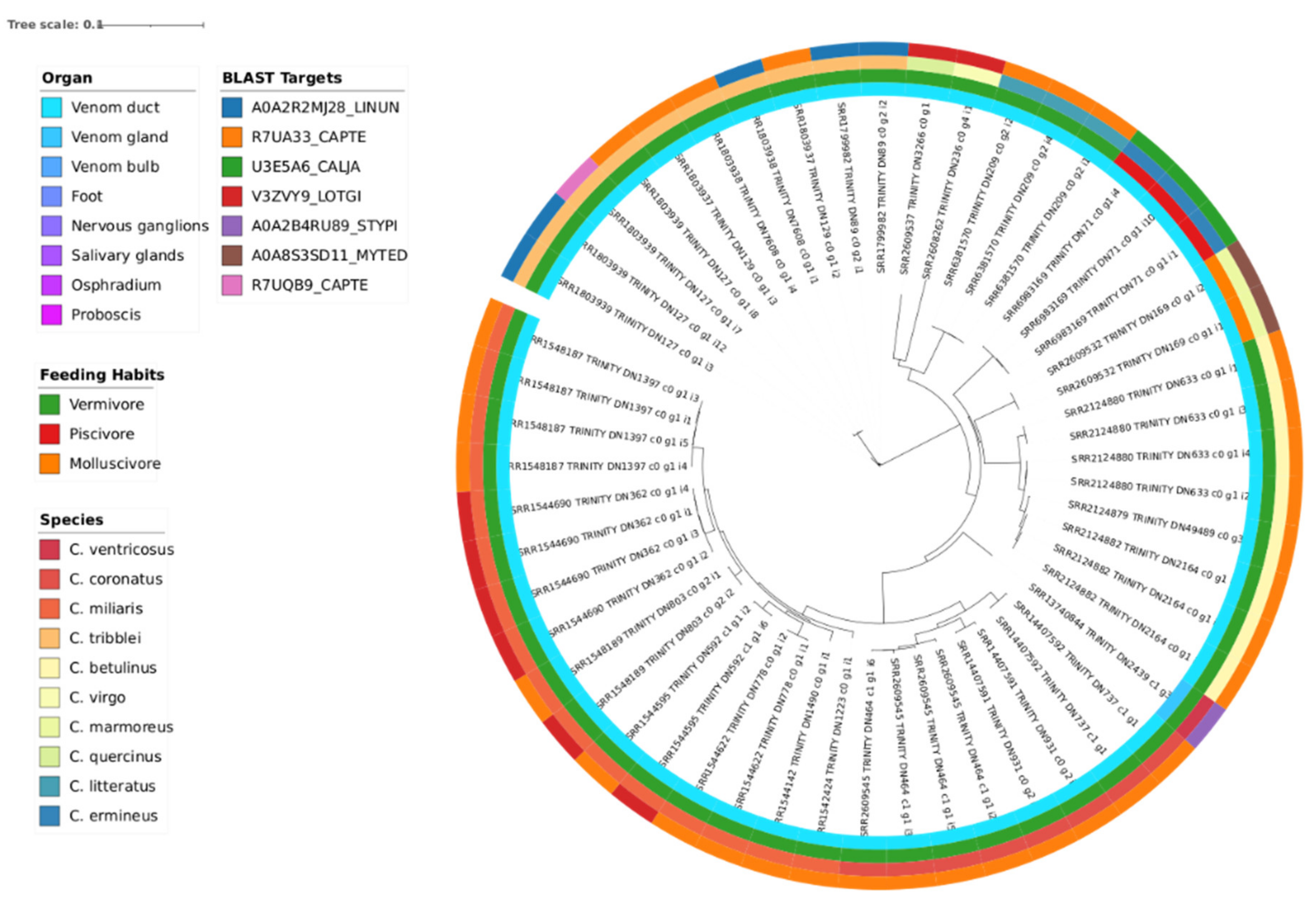

3.3. Phylogeny

3.4. AMP Prediction Results

3.4.1. AMP Potential of the Shared Venom Transcripts

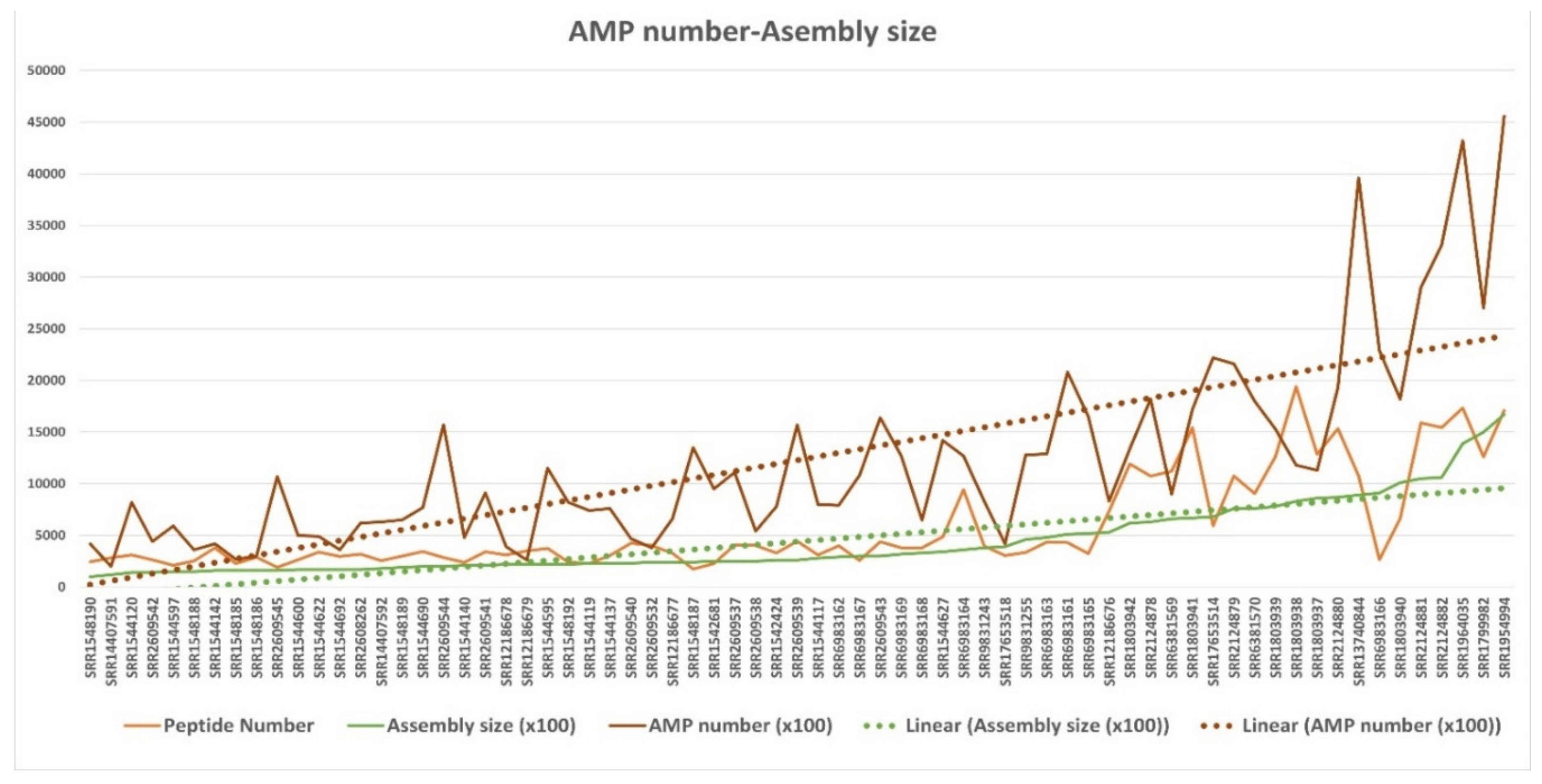

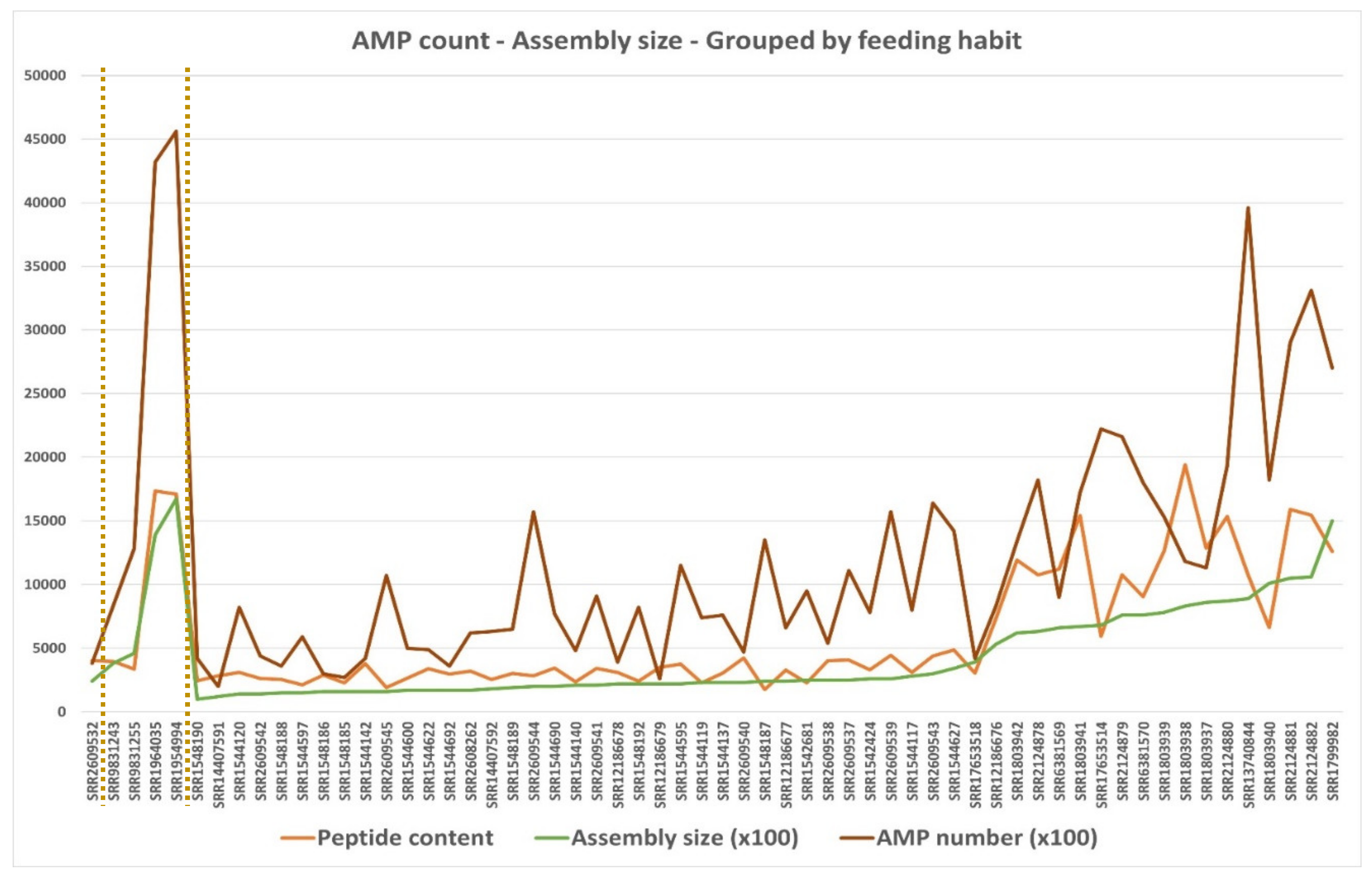

3.4.2. Broad Transcriptomes AMP Potential

4. Discussion

4.1. Symbiosis in Venom Organs

4.2. Predation Impact on Venom Evolution

4.3. Biomedical Findings in Conus Venoms

4.4. ACE2 similarity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| AMP(s) | Anti-Microbial Peptide(s) |

| Mb(s) | Megabyte(s) |

| PTM(s) | Post-Transcriptional Modification(s) |

Appendix A

| GO ID | GO Category | GO Term |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0003081 | Biological process | Regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure by renin-angiotensin |

| GO:0003084 | Biological process | Positive regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure |

| GO:0019882 | Biological process | Antigen processing and presentation |

| GO:0030212 | Biological process | Hyaluronan metabolic process |

| GO:0031288 | Biological process | Sorocarp morphogenesis |

| GO:0071577 | Biological process | Zinc ion transmembrane transport |

| GO:0097067 | Biological process | Cellular response to thyroid hormone stimulus |

| GO:0140206 | Biological process | Dipeptide import across plasma membrane |

| GO:1903052 | Biological process | Positive regulation of proteolysis involved in protein catabolic process |

| GO:1903665 | Biological process | Negative regulation of asexual reproduction |

| GO:1903669 | Biological process | Positive regulation of chemorepellent activity |

| GO:0016532 | Molecular function | Superoxide dismutase copper chaperone activity |

| GO:0016671 | Molecular function | Oxidoreductase activity; acting on a sulphur group of donors; disulphide as acceptor |

| GO:0031545 | Molecular function | Peptidyl-proline 4-dioxygenase activity |

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Sequences | Percentage of Identity |

|---|---|

| >SRR1544119_TRINITY_DN22969_c0_g1_i1 | 51,5% LOC106073291 Biomphalaria glabrata (Bloodfluke planorb) (Freshwater snail) |

| CGGCACTGAAGGACGAGAACAAAGTGGCACGGTTTAACGAGCTAGTGGCCAAGATGTCGGAGATCTACAGCACCGCTCAAGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGGCAACTGTATCTCCCTGGATCCAGACCTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGACTGAAGCCTGGGAGCTGTGGAGAAAGGCCACTGGAGGAAAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTGAGCTGGCGAACGAAGGCGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGATGACTACGAAGACGAA | |

| >SRR1544120_TRINITY_DN2907_c0_g1_i1 | 50% LOC106073291 Biomphalaria glabrata (Bloodfluke planorb) (Freshwater snail) |

| TTGCCAACGCCACCCAGCGGCGCCTGCTGAAGCAAATCCGCAAGATCGGCACGGCGGCACAGAAGGACGAGAACAAAGTGGCACGGTTTAACGAGCTAGTGGCCAAGATGTCGGAGATCTACAGCACCGCTCAGGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGACAACTGTATCTCCCTGGATCCAGACCTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGACTGAAGCCTGGGATCTGTGGAGAAAGGCCACTGGAGGGAAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTGAGCTGGCGAACGAAGGCGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGATGACTACGAAGACGAA | |

| >SRR1544137_TRINITY_DN16819_c0_g1_i1 | 51,5% LOC106073291 Biomphalaria glabrata (Bloodfluke planorb) (Freshwater snail) |

| CGGCACTGAAGGACGAGAACAAAGTGGCACGGTTTAACGAGCTAGTGGCCAAGATGTCGGAGATCTACAGCACCGCTCAAGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGGCAACTGTATCTCCCTGGATCCAGACCTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGACTGAAGCCTGGGAGCTGTGGAGAAAGGCCACTGGAGGAAAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTGAGCTGGCGAACGAAGGCGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGATGACTACGAAGACGAA | |

| >SRR1544140_TRINITY_DN13380_c0_g1_i1 | 52,9% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| AGAACCTGGCGAGGAGCTGGCTACAGAAATACAACCAAGAGCACAAAGACATTTTCTCCAAGTCCTCAGAAATGACCTGGAACTACGCTACCAACGTCACGGACGAAATTCAACAAAAACAAGTGAATGCAGAGCTGCAGGTGGCGCAATGGCAACAGGAGAAGGCAGCAGAAGTGGAACATTACGACTGGGAGCATTTTTCCGACAGCAGTCTTGTACGTCAGTTCCGTTTTGCGAGGAATATAGGCACGTCTGCCATG | |

| >SRR1544595_TRINITY_DN5707_c0_g1_i1 | 61,9% C0Q70_16356 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| CTGAGGCTGGACACAAACTGAGGGCCATGCTGTCCAAAGGATCGTCTGAGGTGTGGACAGTACCATTCCAGGCCCTGACAGGACAGACCAAGATGAGCGCACAATCACTGATCCAGTACTTCCAGCCCCTCATGGACTACCTGGAGCAGTACACCAAGGACCACGGCGTGGAGGTTGGGTGGAAGGAGGAGTGTTCT | |

| >SRR1544600_TRINITY_DN9395_c0_g1_i1 | 56,3% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| TCGTTTTTCATGGCAGACGTGCCTATATTCCTTGCAAAACGGAACTGACGTACAAGACTGCTGTCGGAAAAATGCTCCCAGTCGTAATGTTCCACTTCCGCTGCCTTCCTCTGTTGCCATTGCGCCACCTGCAGCTCTGCATTCACTTGTTTTTGTTGATTTTCGTCCGTGACGTTGGTAGCGTAGTTCCAGGTCATTTCTGAGGACTTGGAGACAATGTCTTTGTGCTCTTGGTTGTATTTCTGTAGCCAGCTCCTCGCCAGGTTCTC | |

| >SRR1544692_TRINITY_DN15875_c0_g1_i1 | 55,8% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| TCGTTGCTCAGCGCCACGAACTCCTCGTAATCGCTCTTCATCAGAGGCCCTGTGACGTCACGCCACTCCTTCCACGCCATCAGCAGTTCGTCATAGTCACGCGATGACGCCATCAGTTTGGTCAGTTCAGGATCCAGATTCAAAATGGCCCCGGTCTTTGGATCCTTCACTTTAGCTTTGGCGTAGATACCTTCAATGGTCGACTGTAGCTCTTTTAGCTCTTTCAGTTTAGTTTCGTTTTTCATGGCAGACGTGCCTATATTCCTTGCAAAACGGAACTGACGTACAAGACTGCTGTCGGAAAAATGCTCCCAGTCGTAATGTTCCACTTCCGCTGCCTTCCTCTGTTGCCATTGCGCCACCTGCAGCTCTGCATTCACTTGTTTTTGTTGATTTTCGTCCGTGACGTTGGTAGCGTAGTTCCAGGTCATTTCTGAGGACTTGGAGATAATGTCTTTGTGCTCTTTGTTGTATTTCTGTAGCCAGCTCCTCGCCAGGTTCTC | |

| >SRR1544692_TRINITY_DN2117_c0_g1_i1 | 68,3% LOC110975981 Acanthaster planci (Crown-of-thorns starfish) |

| TCCTCACTCCAGCCAACGGGCTGGCCGGCGTTCTGCTCCTCCAGCCAATCCTGAAGCGGCCTGAAGTACTCCAGCAGCGGCCTCACGTCCATGTGTCTGGTGCCCGTGATCTGCTCCAGGGCCTC | |

| >SRR6983166_TRINITY_DN44676_c0_g1_i1 | 56,8% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| ACAGCACCGCTCGAGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGACAACTGTATTCCCCTGGACCCGGACGTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGGCTGAAGCCTGGGATCTGTGGAGAGAGGCCACTGGAGGAGAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTCAGCTGGGAAACGAAGGAGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGACGAGTATGAAGACGAA | |

| >SRR6983168_TRINITY_DN6724_c0_g2_i1 | 49% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| CGGACAGCGAGGCAGTGGAAGCCTTCTTGGAGACGCACGACAAGGAGACTAAGAAGAAGCATGAAAAGTACGAGATTCTGTCCTGGAATCACGAAACCAATATCACCGACTACAATCAGGAGCTGAAGGTCAACTACAGCGTAGAGATGTCAGAATTTGCTAAAGAGCACGCCAGGCAGTCGGCCATGTTTGACCTTGATCACCTTGCCAACGCCACCCAGCGGCGCCTGCTGAAGAAAATCGGCAAAATCGGCACGGCGGCACAGAAGGACGAGAACAAAGTGGCACGGTTTAACGAGCTGGTGGCCAAGATGTCGGAGATCTACAGCACCGCTCGAGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGACAACTGTATTCCCCTGGACCCGGACGTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGGCTGAAGCCTGGGATCTGTGGAGAGAGGCCACTGGAGGAGAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTCAGCTGGGAAACGAAGGCGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGACGAGTATGAAGACGAAAATCTGCAAGAAGAGTTAGCGGCCCTGATGGAACAGCTCCGTCCTTTGTACGTGAAGCTCCAC | |

| >SRR6983169_TRINITY_DN17529_c0_g1_i1 | 51% C0Q70_02791 Pomacea canaliculata (Golden apple snail) |

| TTCTGTCCTGGAATCACGAAACCAATATCACCGACTACAATCAGGAGCTGAAGGTCAACTACAGCGTAGAGATGTCAGAATTTGCTAAAGAGCACGCCAGGCAGTCGGCCATGTTTGACCTTGATCACCTTGCCAACGCCACCCAGCGGCGCCTGCTGAAGAAAATCGGCAAAATCGGCACGGCGGCACAGAAGGACGAGAACAAAGTGGCACGGTTTAACGAGCTGGTGGCCAAGATGTCGGAGATCTACAGCACCGCTCGAGTGTGCTTTACGGAAGACAACTGTATTCCCCTGGACCCGGACGTCAAACGGCTCTTTGAACACAGCAGAAACTACACATTGCTGGCTGAAGCCTGGGATCTGTGGAGAGAGGCCACTGGAGGAGAAATGAAAGCCCTGTACGAGGAGTATGTTCAGCTGGGAAACGAAGGCGTTCAGGAACTGGGTTTCAACGACATGGGAGAGTACTGGCGAGACGAGTATGAAGACGAA |

Appendix E

| Protein ID | AMP ID | Abundance | Protein ID | AMP ID | Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P83578|IKP1_PHYSA | AMP_11771 | 7 | P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_14282 | 20 |

| P61095|SFI1_SEGFL | AMP_15699 | 4 | P0DKT2|TU92_GEMSO | AMP_25599 | 20 |

| Q90WJ8|AJL2_ANGJA | AMP_00722 | 3 | P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_14283 | 16 |

| P39060|COIA1_HUMAN | AMP_14664 | 3 | P00738|HPT_HUMAN | AMP_04692 | 15 |

| P01038|CYT_CHICK | AMP_23459 | 2 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_18775 | 11 |

| P0C2D2|OXLA_CRODC | AMP_00139 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_18778 | 11 |

| Q9JHY3|WFD12_MOUSE | AMP_02769 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_18779 | 11 |

| P22887|NDKC_DICDI | AMP_09422 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_18780 | 11 |

| P22355|PSPB_RAT | AMP_00195 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_18781 | 11 |

| Q29075|NKL_PIG | AMP_03456 | 1 | P06702|S10A9_HUMAN | AMP_09443 | 6 |

| Q29075|NKL_PIG | AMP_03457 | 1 | P06702|S10A9_HUMAN | AMP_11387 | 6 |

| Q29075|NKL_PIG | AMP_04409 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_27220 | 6 |

| Q29075|NKL_PIG | AMP_21444 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_27221 | 6 |

| Q8TDE3|RNAS8_HUMAN | AMP_05220 | 1 | P05484|O17A_CONMA | AMP_27222 | 6 |

| A0A7I2V2E9|A0A7I2V2E9_HUMAN | AMP_19944 | 10 | P83952|WAPA_OXYMI | AMP_04982 | 4 |

| P00974|BPT1_BOVIN | AMP_10608 | 76 | B5G6G7|WAPB_OXYMI | AMP_04983 | 4 |

| I2G9B4|VKT_MACLN | AMP_15720 | 76 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_02393 | 2 |

| P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_04915 | 62 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_02394 | 2 |

| P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_04916 | 62 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_02395 | 2 |

| P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_04917 | 62 | A0A0C4G5K0|NDB3_HETSP | AMP_02396 | 2 |

| P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_04918 | 60 | P82427|WTX1E_NEOGO | AMP_02397 | 2 |

| P08311|CATG_HUMAN | AMP_04624 | 56 | P0DJ02|NDB49_HETPE | AMP_08335 | 2 |

| P86810|OXLA_SIGCA | AMP_11257 | 50 | A0A0C4G5K0|NDB3_HETSP | AMP_17099 | 2 |

| P86810|OXLA_SIGCA | AMP_11258 | 50 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_22673 | 2 |

| Q4JHE1|OXLA_PSEAU | AMP_00142 | 48 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_22674 | 2 |

| F8S0Z5|OXLA2_CROAD | AMP_00224 | 48 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_22676 | 2 |

| P04284|PR06_SOLLC | AMP_07416 | 45 | P83240|NDB31_PANIM | AMP_22677 | 2 |

| P04284|PR06_SOLLC | AMP_10197 | 45 | P13487|KAX11_LEIHE | AMP_01368 | 1 |

| P81382|OXLA_CALRH | AMP_00135 | 44 | A9XE60|KBX11_MESEU | AMP_02691 | 1 |

| Q6TGQ8|OXLA_BOTMO | AMP_00137 | 44 | P82656|NDB21_HOFAZ | AMP_03049 | 1 |

| Q90W54|OXLA_GLOBL | AMP_00138 | 44 | F1AWB0|NDB27_VAEME | AMP_03190 | 1 |

| Q6STF1|OXLA_GLOHA | AMP_00422 | 44 | F1AWB0|NDB27_VAEME | AMP_03191 | 1 |

| Q6STF1|OXLA_GLOHA | AMP_00423 | 44 | P83239|NDB23_PANIM | AMP_03236 | 1 |

| Q6TGQ9|OXLA1_BOTJR | AMP_08879 | 43 | P83313|NDB24_OPICA | AMP_03238 | 1 |

| Q9U8W7|TL5B_TACTR | AMP_01246 | 42 | P83313|NDB24_OPICA | AMP_03239 | 1 |

| B5AR80|OXLA_BOTPA | AMP_00127 | 41 | P83314|NDB2S_OPICA | AMP_04307 | 1 |

| B5AR80|OXLA_BOTPA | AMP_00128 | 41 | A0A0C4G489|NDB2_HETSP | AMP_04308 | 1 |

| Q9U8W8|TL5A_TACTR | AMP_10191 | 41 | P0C2F4|KBX3_HETLA | AMP_04346 | 1 |

| P00734|THRB_HUMAN | AMP_09738 | 39 | P56972|KBX3_PANIM | AMP_04348 | 1 |

| P00734|THRB_HUMAN | AMP_09739 | 39 | Q0GY40|KBX3_HOFGE | AMP_04390 | 1 |

| P20160|CAP7_HUMAN | AMP_14281 | 29 | Q5WR03|KBX31_OPICA | AMP_05482 | 1 |

| Q1PHZ4|VM3B1_BOTJR | AMP_01520 | 27 | P13487|KAX11_LEIHE | AMP_10082 | 1 |

| Q6IWZ0|OXLA_APLCA | AMP_01042 | 26 | P0C2F4|KBX3_HETLA | AMP_17928 | 1 |

| Q6IWZ0|OXLA_APLCA | AMP_01043 | 26 | A9XE60|KBX11_MESEU | AMP_23221 | 1 |

Appendix F

Appendix G

| Species and Tissue | Completed - Total | Complete - Single Copy | Complete - Duplicated | Fragmented | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 110 | 94 | 16 | 75 | 769 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 122 | 102 | 20 | 85 | 747 |

| C. coronatus Venom duct | 122 | 108 | 14 | 74 | 758 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 128 | 109 | 19 | 98 | 728 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 128 | 110 | 18 | 98 | 728 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 142 | 119 | 23 | 116 | 696 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 153 | 129 | 24 | 108 | 693 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 153 | 129 | 24 | 106 | 695 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 166 | 135 | 31 | 118 | 670 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 161 | 136 | 25 | 98 | 695 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 174 | 138 | 36 | 113 | 667 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 164 | 140 | 24 | 138 | 652 |

| C. coronatus Venom duct | 166 | 144 | 22 | 122 | 666 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 174 | 145 | 29 | 95 | 685 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 180 | 151 | 29 | 133 | 641 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 176 | 151 | 25 | 104 | 674 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 191 | 161 | 30 | 135 | 628 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 191 | 162 | 29 | 135 | 628 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 190 | 163 | 27 | 111 | 653 |

| C. consors Foot | 244 | 163 | 81 | 129 | 581 |

| C. coronatus Venom duct | 192 | 166 | 26 | 128 | 634 |

| C. sponsalis Venom duct | 203 | 167 | 36 | 127 | 624 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 196 | 173 | 23 | 115 | 643 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 210 | 176 | 34 | 163 | 581 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 230 | 189 | 41 | 133 | 591 |

| C. imperialis Venom duct | 220 | 190 | 30 | 114 | 620 |

| C. virgo Venom duct | 210 | 191 | 19 | 150 | 594 |

| C. imperialis Venom duct | 227 | 192 | 35 | 162 | 565 |

| C. coronatus Venom duct | 222 | 193 | 29 | 114 | 618 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 241 | 196 | 45 | 148 | 565 |

| C. ebraeus Venom duct | 229 | 200 | 29 | 180 | 545 |

| C. imperialis Venom duct | 240 | 207 | 33 | 148 | 566 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 256 | 214 | 42 | 111 | 587 |

| C. lividus Venom duct | 259 | 215 | 44 | 189 | 506 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 256 | 219 | 37 | 184 | 514 |

| C. imperialis Venom duct | 251 | 222 | 29 | 125 | 578 |

| C. marmoreus Venom duct | 247 | 222 | 25 | 151 | 556 |

| C. miliaris Venom duct | 268 | 224 | 44 | 184 | 502 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 271 | 228 | 43 | 110 | 573 |

| C. ebraeus Venom duct | 286 | 232 | 54 | 86 | 582 |

| C. rattus Venom duct | 282 | 234 | 48 | 186 | 486 |

| C. quercinus Venom duct | 267 | 237 | 30 | 161 | 526 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 301 | 249 | 52 | 130 | 523 |

| C. varius Venom duct | 297 | 250 | 47 | 163 | 494 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 294 | 251 | 43 | 175 | 485 |

| C. tribblei Venom duct | 307 | 253 | 54 | 281 | 366 |

| C. tribblei Venom duct | 313 | 256 | 57 | 264 | 377 |

| C. magus Venom duct | 315 | 258 | 57 | 106 | 533 |

| C. tribblei Venom duct | 318 | 267 | 51 | 256 | 380 |

| C. lenavati Venom duct | 343 | 274 | 69 | 262 | 349 |

| C. lenavati Venom duct | 334 | 274 | 60 | 207 | 413 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 356 | 274 | 82 | 104 | 494 |

| C. magus Venom duct | 344 | 279 | 65 | 113 | 497 |

| C. lenavati Venom duct | 365 | 284 | 81 | 253 | 336 |

| C. betulinus Venom duct | 355 | 286 | 69 | 263 | 336 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 364 | 287 | 77 | 103 | 487 |

| C. betulinus Venom duct | 388 | 301 | 87 | 268 | 298 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 390 | 314 | 76 | 116 | 448 |

| C. judaeus Venom duct | 421 | 337 | 84 | 123 | 410 |

| C. litteratus Venom duct | 453 | 357 | 96 | 230 | 271 |

| C. litteratus Venom duct | 500 | 371 | 129 | 218 | 236 |

| C. ventricosus Foot | 471 | 382 | 89 | 121 | 362 |

| C. imperialis Venom duct | 460 | 385 | 75 | 170 | 324 |

| C. ventricosus Foot | 544 | 424 | 120 | 120 | 290 |

| C. ermineus Venom duct | 574 | 429 | 145 | 133 | 247 |

| C. consors Nervous ganglions | 771 | 446 | 325 | 94 | 89 |

| C. consors Venom duct | 750 | 458 | 292 | 90 | 114 |

| C. ventricosus Venom gland | 584 | 463 | 121 | 124 | 246 |

| C. betulinus Venom duct | 568 | 464 | 104 | 208 | 178 |

| C. consors Osphradium | 836 | 465 | 371 | 65 | 53 |

| C. consors Salivary glands | 694 | 480 | 214 | 130 | 130 |

| C. betulinus Venom duct | 662 | 485 | 177 | 154 | 138 |

| C. consors Proboscis | 826 | 489 | 337 | 63 | 65 |

| C. consors Venom bulb | 751 | 489 | 262 | 99 | 104 |

| C. betulinus Venom duct | 600 | 517 | 83 | 205 | 149 |

| C. tribblei Venom duct | 667 | 542 | 125 | 165 | 122 |

References

- C. H. Y. B. C. L. J. L. J. Z. K. Y. X. L. Z. H. Y. C. J. a. L. Y. Peng, “The first Conus genome assembly reveals a primary genetic central dogma of conopeptides in C. betulinus,” Cell Discov., vol. 7, nº 11, 2021.

- J. I. I. A. S. A. C. T. M. a. Z. R. Pardos-Blas, “The genome of the venomous snail Lautoconus ventricosus sheds light on the origin of conotoxin diversity,” Gigascience, vol. 10, 2021.

- J. R. P.-B. C. M. L. A. M. J. T. R. Z. Ana Herráez-Pérez, “Chromosome-level genome of the venomous snail Kalloconus canariensis: a valuable model for venomics and comparative genomics,” GigaScience, vol. 12, 2023.

- T. F. A. J. K. a. S. R. P. Duda Jr, “Origins of diverse feeding ecologies within Conus, a genus of venomous marine gastropods,” Biol. J. Linn. Soc., vol. 73, p. 391–409, 2001.

- N. D. T. F. M. C. O. B. M. &. B. P. Puillandre, “One, four or 100 genera? A new classification of the cone snails,” J. Molluscan Stud., vol. 81, p. 1–23, 2015.

- B. P. C. Y. J. Y. Y. Z. J. &. S. Q. Gao, “Cone snails: A big store of conotoxins for novel drug discovery,” Toxins, vol. 9, nº 397, 2017.

- J. R. S. D. A. H. J. V. L. B. H. F. C. C. J. G. D. J. V. P. F. A. a. R. J. L. Prashanth, “The role of defensive ecological interactions in the evolution of conotoxins,” Mol. Ecol., vol. 25, p. 598–615, 2016.

- L. Nguyen, D. Craik e Kaas, “Bibliometric Review of the Literature on Cone Snail Peptide Toxins from 2000 to 2022,” Mar. Drugs, vol. 21, p. 154, 2023.

- M. R. Richard Georges, Panorama sur La Diversite des Conidae 110 Espèces Prédatrices des Plus Efficaces, 2021.

- R. a. C. D. Endean, “The venom apparatus of Conus magus,” Toxicon, vol. 4, p. 275–284., 1967.

- A.-H. M. M. S. D. S. W. A. H. Q. K. D. J. C. R. J. L. a. P. F. A. Jin, “Conotoxins: Chemistry and Biology,” Chem. Rev., nº 119, p. 11510–11549, 2019.

- K. B. M. M. S. D. Q. K. D. J. C. R. J. L. a. P. F. A. Akondi, “Discovery, synthesis, and structure: Activity relationships of conotoxins,” Chem. Rev., vol. 114, p. 5815–5847, 2014.

- O. G. B. a. B. M. O. Buczek, “Conotoxins and the posttranslational modification of secreted gene products,” Cell. Mol. Life Sci., vol. 62, p. 3067–3079, 2005.

- J. L. Z. L. J. S. I. A. A. V. V. B. M. O. a. E. W. S. Neves, “Small Molecules in the Cone Snail Arsenal,” vol. 17, p. 4933–4935, 2015.

- L. Y. S. X. a. C. W. Lu, “Various Conotoxin Diversifications Revealed by a Venomic Study of Conus flavidus,” Mol. Cell. Proteom., vol. 13, p. 105–118., 2014.

- A.-H. S. D. Q. K. V. L. P. K. R. J. L. a. P. F. A. Jin, “Transcriptomic messiness in the venom duct of Conus miles contributes to conotoxin diversity,” Mol. Cell. Proteom., vol. 12, p. 3824–3833, 2013.

- J. A. W. P. K. a. J. V. S. Jakubowski, “Screening for post-translational modifications in conotoxins using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry: An important component of conotoxin discovery,” Toxicon, vol. 47, p. 688–699, 2006.

- Q. J.-C. W. a. D. J. C. Kaas, “Conopeptide characterization and classifications: An analysis using ConoServer,” Toxicon, vol. 55, p. 1491–1509., 2010.

- K. D. K. L. L. F. S. R. R. M. Laht S, “Identification and classification of conopeptides using profile Hidden Markov Models,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, vol. 1824, nº 3, pp. 488-492, 2012.

- Q. Y. R. J. A. D. S. a. C. D. Kaas, “ConoServer: Updated content, knowledge, and discovery tools in the conopeptide database,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 40, p. D325–D330, 2011.

- J. C. H. a. M. F. Rivera-Ortiz, “Intraspecies variability and conopeptide profiling of the injected venom of Conus ermineus,” Peptides, vol. 32, p. 306–316, 2011.

- C. M. K. a. S. J. Prator, “Venom variation during prey capture by the cone snail, Conus textile,” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, 2014.

- D. S. D. M. L. V. J. A. L. R. a. A. Jin, “Transcriptomic-Proteomic Correlation in the Predation-Evoked Venom of the Cone Snail, Conus imperialis,” Marine drugs, vol. 17, nº 3, p. p.177, 2019.

- B. C. H. P. L. M. Y. N. a. C. N. Junqueira-de-Azevedo, “Venom-related transcripts from Bothrops jararaca tissues provide novel molecular insights into the production and evolution of snake venom,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 32, p. 754–66, 2015.

- C. D. A. A. S. K. A. R. S. D. C. N. M. S. a. C. T. Reyes-Velasco, “Expression of venom gene homologs in diverse python tissues suggests a new model for the evolution of snake venom,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 32, p. 173–83, 2015.

- S. M. H. M. L. D. a. M. J. Hargreaves, “Restriction and recruitment—gene duplication and the origin and evolution of snake venom toxins,” Genome Biol Evol, vol. 6, p. 2088– 95, 2014.

- S. R. P. Thomas F. Duda, “Molecular genetics of ecological diversification: Duplication and rapid evolution of toxin genes of the venomous gastropod Conus,” Biological Sciences, vol. 96, nº 12, pp. 6820-6823, 1999.

- N. W. M. O. B. Puillandre, “Evolution of Conus Peptide Genes: Duplication and Positive Selection in the A-Superfamily,” J Mol Evol, vol. 70, p. 190–202, 2010.

- T. F. D. J. Dan Chang, “Extensive and Continuous Duplication Facilitates Rapid Evolution and Diversification of Gene Families,” Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 29, nº 8, p. 2019–2029, 2012.

- a. B. K. Whittington, “Platypus venom genes expressed in non-venom tissues,” Aust J Zool, vol. 57, p. 199–202, 2009.

- E. A. U. S. A. A. T. N. J. J. D. H. S. T. R. D. M. L. C. D. W. R. N. L. v. d. W. N. V. K. R. I. H. S. P. Bryan G. Fry, “Squeezers and Leaf-cutters: Differential Diversification and Degeneration of the Venom System in Toxicoferan Reptiles,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, vol. 12, nº 7, pp. 1881-1899, 2013.

- R. D. E. C. H. S. J. D. T. G. F. K. T. J. N. J. A. N. R. J. L. R. S. N. C. R. a. R. C. R. d. l. V. Bryan G. Fry1, “The Toxicogenomic Multiverse: Convergent Recruitment of Proteins Into Animal Venoms,” Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, vol. 10, pp. 483-511, 2009.

- K. B. Emily S.W. Wong, “Venom evolution through gene duplications,” Gene, vol. 496, nº 1, pp. 1-7, 2012.

- K. V. L. V. T. S. M. T. K. J. V. R. J. Jana Helsen, “Gene Loss Predictably Drives Evolutionary Adaptation,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 37, nº 10, p. 2989–3002, 2020.

- H. J. G. R. L. F. B. E. L. &. M. H. Virag Sharma, “A genomics approach reveals insights into the importance of gene losses for mammalian adaptations,” Nature Communications, vol. 9, p. 1215, 2018.

- Casewell, “Venom Evolution: Gene Loss Shapes Phenotypic Adaptation,” Current Biology, vol. 26, nº 18, pp. R849-R851, 2016.

- Von Reumont, “Studying Smaller and Neglected Organisms in Modern Evolutionary Venomics Implementing RNASeq (Transcriptomics)—A Critical Guide,” Toxins, vol. 10, nº 7, p. p.292, 2018.

- v. R. B. A. G. C. F. C. M. F. J. H. E. H. B. I. M. J. F. M. P. d. F. T. M. M. M. Y. N. A. P. J. T. A. T. F. V. R. Z. M. A. A. Zancolli G, “Web of venom: exploration of big data resources in animal toxin research,” GigaScience, p. giae054, 2024.

- B. J. H. R. L. A. C. G. O. B. S. E. Peraud O, “Microhabitats within venomous cone snails contain diverse actinobacteria,” Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 75, nº 21, pp. 6820-6826, 2009.

- J. P. e. a. Torres, “Stenotrophomonas-Like Bacteria Are Widespread Symbionts in Cone Snail Venom Ducts,” Applied and environmental microbiology, vol. 83, nº 23, 2017.

- F. S.,. M. W.,. a. B. O. Matías L. Giglio, “Insights into a putative polychaete-gastropod symbiosis from a newly identified annelid worm that predates upon Conus ermineus eggs,” Contributions to Zoology, vol. 92, nº 2, pp. 97-111, 2023.

- D.-P. Y. M.-P. K. C.-M. A. A. Guillermin Agüero-Chapin, “Unveiling Encrypted Antimicrobial Peptides from Cephalopods’ Salivary Glands: A Proteolysis-Driven Virtual Approach,” ACS Omega, vol. 43, p. 43353–43367, 2024.

- G. A.-C. R. S. Y. M.-P. A. A. Ricardo Alexandre Barroso, “Unlocking Antimicrobial Peptides: In Silico Proteolysis and Artificial Intelligence-Driven Discovery from Cnidarian Omics,” Molecules, vol. 3, nº 550, 2025.

- J. Morim, “Deciphering the transcriptomics of the Conus species’ natural venoms [Master’s Dissertation, University of Porto],” 2022.

- J. S. Martin Steinegger, “MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets,” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 35, p. 1026–1028, 2017.

- R. K. D. H. Buchfink B, “Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND,” Nature Methods, vol. 18, p. 366–368, 2021.

- G. O. F. M. Okonechnikov K, “Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit,” Bioinformatics, vol. 8, p. 1166–1167, 2012.

- J. R. K. D. Y. Kazutaka Katoh, “MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization,” Briefings in Bioinformatics, vol. 20, nº 4, p. 1160–1166, 2019.

- T. N. B. Q. C. M. F. Rognes T, “VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics,” PeerJ, vol. 4, 2016.

- B. Ivica Letunic, “Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool,” Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 52, pp. 78-82, 2024.

- Z. Y.,. X. N. Sen Yang, “AMPFinder: A computational model to identify antimicrobial peptides and their functions based on sequence-derived information,” Analytical Biochemistry, vol. 673, 2023.

- L. N. G. Jake R Conway, “UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties,” Bioinformatics, vol. 33, nº 18, p. 2938–2940, 2017.

- K. K. S. S. Gopal Krishna Patro, “Normalization: A Preprocessing Stage,” arXiv, 2015.

- T. M. O. A. P. C. McDougal OM, “Three-dimensional structure of conotoxin tx3a: an m-1 branch peptide of the M-superfamily.,” Biochemistry, vol. 47, p. 2826–2832, 2008.

- M. O. Jacob RB, “The M-superfamily of conotoxins: a review,” Cell Mol Life Sci, vol. 67, nº 1, pp. 17-27, 2010.

- J. R. J. E. W. M. W. C. C. C. G. J. M. O. L. W. G. W. H. D. R. J. M. J. C. L. O. B. Corpuz GP, “Definition of the M-conotoxin superfamily: characterization of novel peptides from molluscivorous Conus venoms,” vol. 44, p. 8176–8186, 2005.

- Y. a. A. A. Zhao, “Biomedical Potential of the Neglected Molluscivorous and Vermivorous Conus Species,” Marine drugs, vol. 20, nº 2, p. p.105, 2022.

- B. M. S. J. H. M. P. &. F. A. E. Olivera, “Prey-Capture Strategies of Fish-Hunting Cone Snails: Behavior, Neurobiology and Evolution,” Brain Behav Evol, vol. 86, nº 1, pp. 58-74, 2015.

- S. M. J. T. C. M. A. a. R. Z. Abalde, “Conotoxin Diversity in Chelyconus ermineus (Born, 1778) and the Convergent Origin of Piscivory in the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Cones,” Genome biology and evolution, vol. 10, nº 10, pp. 2643-2662, 2018.

- S. W. A. H. R. J. L. Aymeric Rogalski, “Coordinated adaptations define the ontogenetic shift from worm- to fish-hunting in a venomous cone snail,” Nat Commun., vol. 14, nº 1, p.:3287, 2023.

- S. &. L. R. Dutertre, Snails: Biology, Ecology and Conservation, N. Gotsiridze-Columbus, Ed., Nova Science Publishers, 2011, pp. 85-104.

- S. J. A. V. I. H. B. S. K. L. V. D. V. F. B. A. A. V. D. a. A. P. Dutertre, “Evolution of separate predation- and defence-evoked venoms in carnivorous cone snails,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, nº 3521, 2014.

- S. D. R. P. F. S. K. C. J. B. A. E. F. M. Y. B. M. O. H. S.-H. Thomas Lund Koch, “Prey Shifts Drive Venom Evolution in Cone Snails,” Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 41, nº 8, p. msae120, 2024.

- J. S. P. R. a. W. S. Kohn, “Preliminary studies on the venom of the marine snail Conus,” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 90, pp. 706-725, 1960.

- L. X. W. Z. Wang G, “APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 44, p. 1087–1093, 2016.

- R. H. K. T. A.-I. Seema Patel, “Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS): The ubiquitous system for homeostasis and pathologies,” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 94, pp. 317-325, 2017.

- I. A. B. I. C. L. G. Z. S. D. G. T. S. R. A. R. a. M. A. Oliveira, “A potential interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors,” Biophysical journal, vol. 120, nº 6, pp. 983-993, 2021.

- J. W. X. Lan J., “Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor,” Nature, vol. 581, pp. 215-220, 2020.

- J. A. Z. R. F. a. M. M. Changeux, “A nicotinic hypothesis for Covid-19 with preventive and therapeutic implications,” Comptes Rendus. Biologies, vol. 343, nº 1, pp. 33-39, 2020.

- U. S. C. J. Camacho, “Omicron and Alpha P680H block SARS-CoV2 spike protein from accessing cholinergic inflammatory pathway via α9-nAChR mitigating the risk of MIS-C,” bioRxiv, 2022.

| Transcriptomic group | Number of peptides | Number of Toxins | AMP predictions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venom-related | 553,878 | 28,805 | 71 (15 unique) |

| Venom-unrelated | 108,466 | 1,902 | 73 (17 unique) |

| Data index | File |

Species (diet) |

Abundance | Data base hit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP_00195 | SRR2124881 | C. betulinus vermivorous | 1 | AGANDLCQECEDIVHLLTKMTKEDAFQDTIRKFLEQECDILPLKLLVPRCRQVLDVYLPLVIDYFQGQIKPKAICSHVGLC | Pulmonary protein B precursor |

| AMP_03456 | SRR6983168 | C. ermineus piscivorous | 1 | GLICESCRKIIQKLEDMVGPQPNEDTVTQAASQVCDKLKILRGLCKKIMRSFLRRISWDILTGKKPQAICVDIKICKEKT | Antimicrobial peptide NK-lysin precursor |

| AMP_03457 | SRR6983168 | 1 | GLICESCRKIIQKLEDMVGPQPNEDTVTQAASQVCDKLKILRGLCKKIMRSFLRRISWDILTGKKPQAICVDIKICKEKTGLI | ||

| AMP_04409 | SRR6983168 | 1 | GYFCESCRKIIQKLEDMVGPQPNEDTVTQAASQVCDKLKILRGLCKKIMRSFLRRISWDILTGKKPQAICVDIKICKE | ||

| AMP_21444 | SRR6983168 | C. ermineus piscivorous | 1 | YFCESCRKIIQKLEDMVGPQPNEDTVTQAASQVCDKLKILRGLCKKIMRSFLRRISWDILTGKKPQAICVDIKICKE | |

| AMP_05220 | SRR17653518 | C. ebraeus vermivorous | 1 | KPKDMTSSQWFKTQHVQPSPQACNSAMSIINKYTERCKDLNTFLHEPFSSVAITCQTPNIACKNSCKNCHQSHGPMSLTMGELTSGKYPNCRYKEKHLNTPYIVACDPPQQGDPGYPLVPVHLDKVV | Ribonuclease, RNase A family, 8 |

| AMP_19944 | SRR6381569 SRR6381570 |

C. literatus vermivorous |

4 | EEQAKTFLDKFNHEAEDLFYQSSLASWNYNTNITEE (See Appendix D for more transcripts sharing similarities with ACE protein) |

ACE2 |

| SRR1542424 SRR1544142 | C. miliaris vermivorous | 2 | |||

| SRR12186679 | C. imperialis vermivorous | 2 | |||

| SRR13740844 |

C. ventricosus vermivorous |

1 | |||

| SRR2609537 |

C. quercinus vermivorous |

1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).