1. Introduction

Neuronal timing plays a critical role in many brain functions including sensory processing [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] or encoding of memory [

7,

8,

9]. In fact, neural information is not solely transmitted through modulation of the firing rate, but also by the fine temporal organization of neuronal discharge [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In simple neuronal networks, the timing between connected neurons is usually described by the synaptic latency which is the sum of the conduction time along the axon that depends on the axon diameter and the presence of myelin, and the synaptic delay [

14]. Synaptic delay is not fixed [

15], but rather it is determined by the calcium concentration in the presynaptic bouton [

16,

17] and the presynaptic release probability (

Pr) [

18]. Synaptic delay is in fact modulated by ~0.5-1 ms during short-term plasticity such as paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) and depression (PPD) or during long-term synaptic enhancement (LTP) or depression (LTD) due to changes in

Pr. In addition, synaptic delay is augmented in sensory-deprived neocortical circuits [

19], confirming that changes in synaptic delay could constitute a putative code for neural information [

18]. In parallel, the duration of the presynaptic waveform (i.e., action potential, AP) strongly determines the synaptic latency. The calcium influx is maximal during the repolarization phase of the AP [

20,

21]. Thus, the broadening of the presynaptic spike prolongs synaptic delay in cortical and hippocampal synapses [

22].

Context-dependent modulation of spike-evoked synaptic transmission has been identified at hippocampal, neocortical and cerebellar synapses [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] and involves either voltage inactivation of presynaptic Kv1 channels [

26,

31,

36], activation of presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels [

30], recovery of axonal Nav from inactivation [

32] or minimization of Nav channel inactivation [

34]. Voltage inactivation of Kv1 channels during depolarization-induced analogue-digital facilitation (d-ADF) broadens the presynaptic AP, increase the spike-evoked calcium influx and thus enhances synaptic transmission [

25,

26,

36,

37]. Then, it is plausible that the

reduced synaptic delay due to the elevation in

Pr would be masked by the

prolonged synaptic delay caused by the Kv1-dependent broadening of the presynaptic AP.

We show here that despite the elevation of Pr and the increased synaptic strength during d-ADF at L5-L5 synapses, the synaptic delay is surprisingly unchanged. As d-ADF is due to a Kv1-dependent broadening in AP with, we conclude that both Pr- and AP duration-dependent changes in synaptic delay compensate for each other. Thus, in contrast with other short-term or long-term presynaptic dynamics, synaptic delay is not changed during context-dependent facilitation.

2. Materials and Methods

Cortical slices (350-400 µm thick) were obtained from 13-to 20-day-old Wistar rats. All experiments were carried out according to the European and Institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Council Directive 86/609/EEC and French National Research Council) and approved by the local health authority (D13055-08, Préfecture des Bouches-du-Rhône). Rats were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate (intraperitoneal, 200 mg kg-1) and killed by decapitation. Slices were cut in an ice-cold solution containing (in mM): 280 sucrose, 26 NaHCO3, 10 D-glucose, 10 MgCl2, 1.3 KCl, 1 CaCl2, and were bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. Slices recovered (1 hr) in a solution containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 3 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.8 NaH2PO4, 10 D-glucose, and were equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Each slice was transferred to a submerged chamber mounted on an upright microscope (Olympus, equipped with a 40x water-immersion objective). L5 pyramidal neurons were visualized using DIC infrared videomicroscopy.

Dual whole-cell recordings were obtained as detailed previously [

38,

39]. Nearby pyramidal neurons with axon initial segment and apical dendrites that run in parallel to the surface of the slice were selected for dual patch-clamp recordings. The external solution contained (in mM) 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO

3, 3 CaCl

2, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl

2, 0.8 NaH

2PO

4 and 10 D-glucose and was equilibrated with 95%0

2/5% C0

2. Patch pipettes (5-10 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (in mM): 120 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na

2ATP, 0.3 NaGTP and 2 MgCl

2, pH 7.4. Some experiments were performed with another pre-synaptic pipette solution containing (in mM): 140 CsMeSO

4, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 4 MgATP and 0.3 NaATP, pH 7.3. Recordings were made at 34°C in a temperature-controlled recording chamber (Luigs & Neumann, Ratingen, Germany). Classically, the presynaptic neuron was recorded in current clamp with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments) and the post-synaptic cell in voltage clamp with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Pre- and post-synaptic cells were held at their resting membrane potential (~-60 / -65 mV). The membrane potential was not corrected for the liquid junction potential (~-13 mV). Presynaptic APs were generated by injecting brief (5-10 ms) depolarizing pulses of current at a frequency of 0.3 Hz. All paired-pulse protocols were performed at a frequency of 20 Hz (i.e., an interval of 50 ms). The voltage and current signals were low-pass filtered (3 kHz) and acquisition of 500 ms sequences was performed at 10-15 kHz with Acquis1 (G. Sadoc, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette France).

Synaptic responses were averaged following alignment of the presynaptic action potentials using automatic peak detection (Detectivent 4.0, N. Ankri, INSERM). The presence or absence of a synaptic connection between two neurons was determined on the basis of averages of 30-50 individual traces, including synaptic failures [

38]. With this technique, even very small responses (<0.2 mV or <10 pA) could be easily detected. In practise, the smaller synaptic responses were 0.1 mV and 4 pA. Nevertheless, the analysis was restricted to a corpus of connections with a mean amplitude larger than 0.3 mV / 10 pA. The latency of individual EPSCs was measured from the peak of the presynaptic AP measured in the cell body to 5% of the EPSC amplitude [

18].

d-ADF was tested by continuously depolarizing or hyperpolarizing the presynaptic membrane potential with injection of holding current. Paired-pulse plasticity was tested using two depolarizing current steps with a delay of 50 ms [

40]. Coefficient of variation was analysed on individual traces [

41]. Data are presented as means ± SEM and paired t-test was used for all comparisons.

3. Results

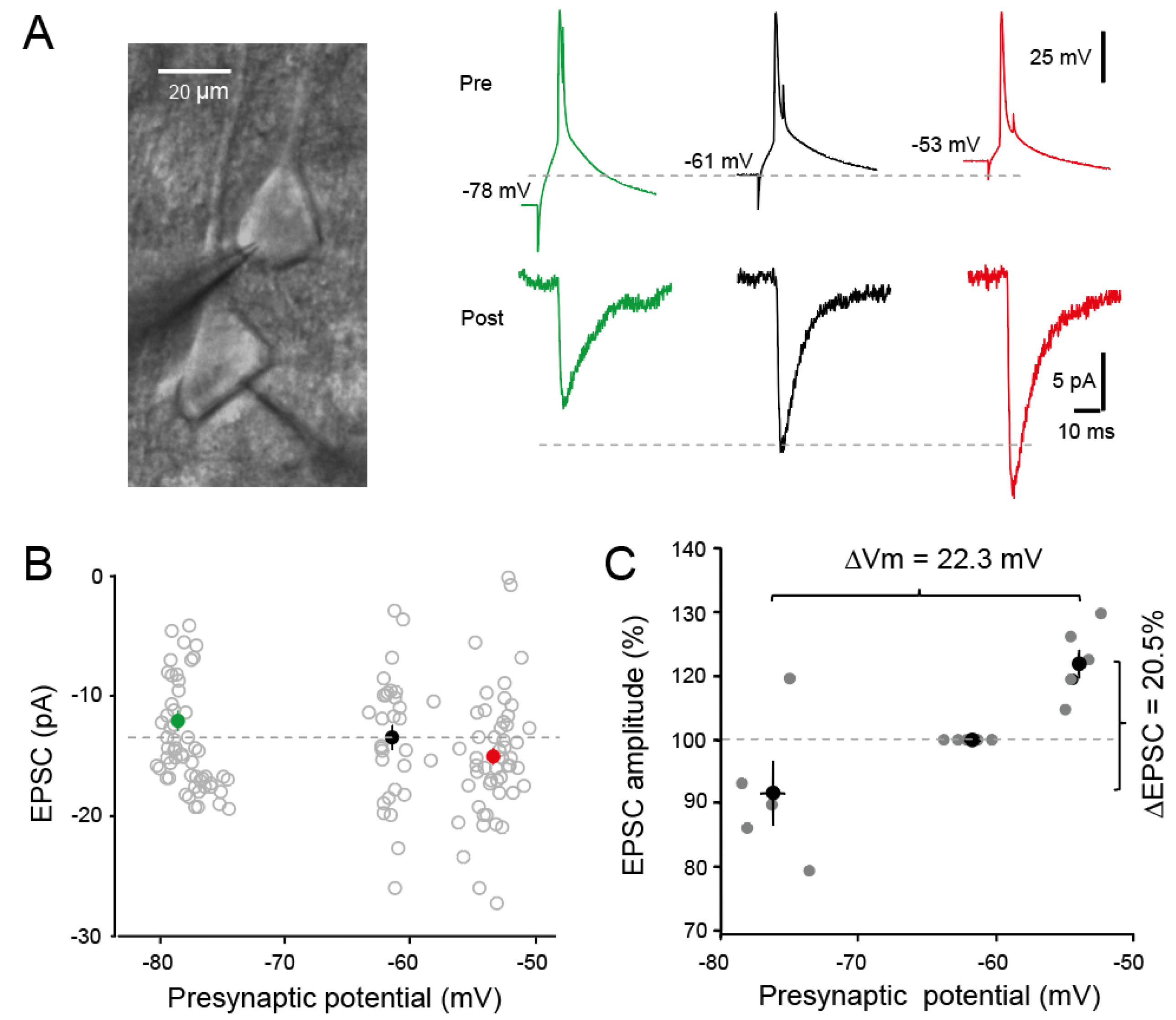

3.1. d-ADF at L5-L5 Synapses

Pairs of connected L5 pyramidal neurons from the sensorimotor cortex of the rat were recorded in whole-cell configuration. To induce depolarization-induced analogue-digital facilitation (d-ADF) and check the impact of the presynaptic membrane potential on the spike-evoked transmission, we changed the holding current from 0 to ± 15-30 pA. Continuous presynaptic hyperpolarization from -61 to -78 mV reduced the amplitude of the spike-evoked EPSC whereas continuous depolarization from -61 to -53 mV increased EPSC amplitude (

Figure 1A,B). On average, a shift in presynaptic membrane potential from -76.4 mV to -54.1 mV (ΔVm = 22.3 mV) induced an EPSC change from -91.4 to 111.9 % (i.e., ΔEPSC = 20.5%; paired t-test, p < 0.05;

Figure 1C), indicating that the facilitation index is ~1 % per mV of presynaptic depolarization, as reported earlier [

26,

31].

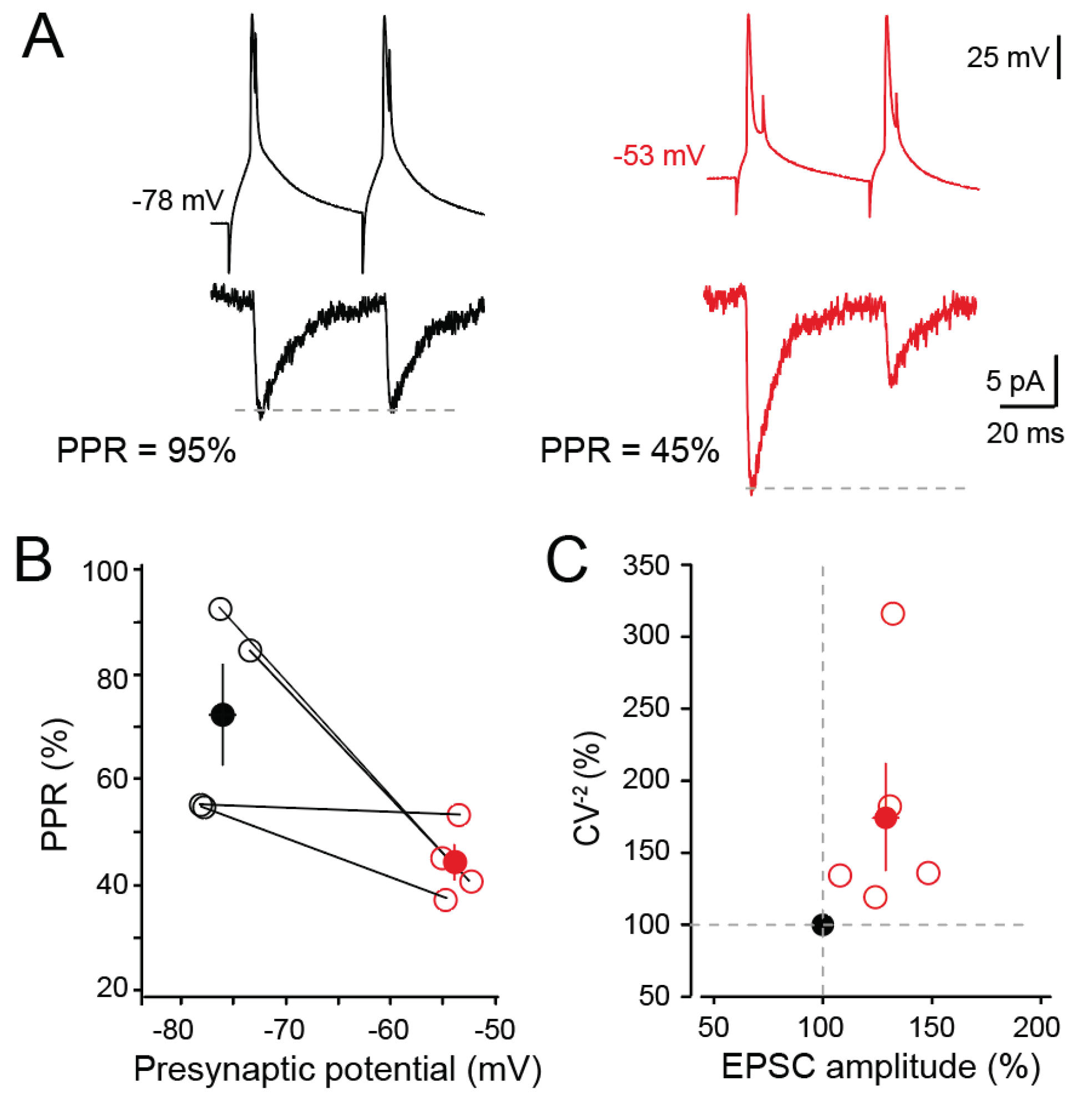

3.2. d-ADF at L5-L5 Synapse Results from an Elevation in Pr

In order to check the presynaptic origin of d-ADF, two successive presynaptic action potentials were triggered with a delay of 50 ms at hyperpolarized (mean: -76.7 mV) and depolarized (mean: -53.8 mV) membrane potentials. d-ADF was associated with a reduced paired-pulse ratio (PPR from 72 ± 10% in control to 44 ± 3% during d-ADF (

Figure 2A,B)). To confirm the presynaptic origin of d-ADF, CV

-2 (coefficient of variation at the power -2) of EPSC fluctuations was analysed. As expected, CV

-2 was elevated (173 ± 37% of the control CV

-2, n = 5; paired t-test p < 0.05) in parallel to that of EPSC amplitude (128 ± 7% of the control, n = 5, paired t-test p < 0.05;

Figure 2C), confirming an increase in

Pr during d-ADF in L5 neurons, as reported earlier [

26,

31].

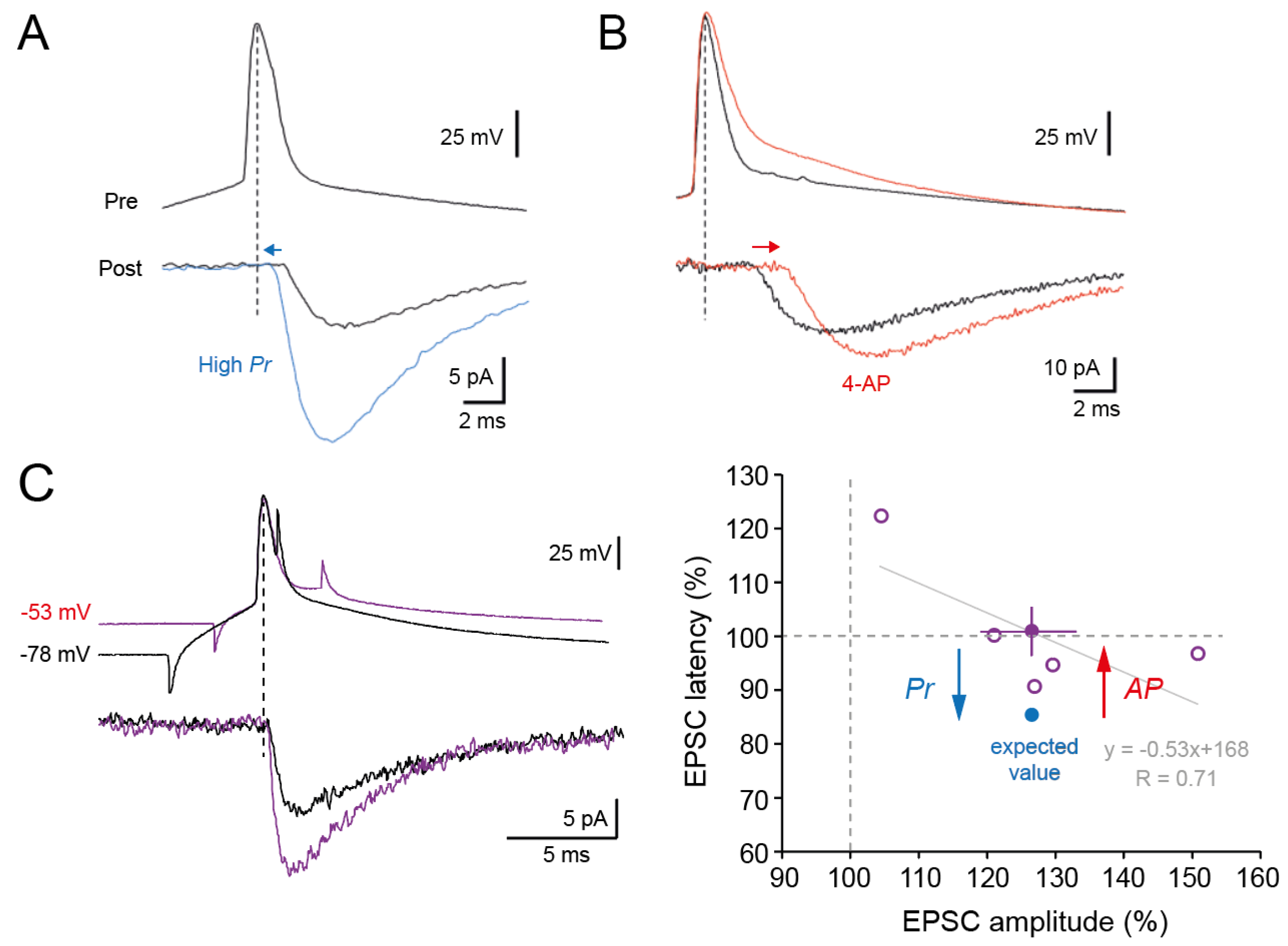

3.3. No Change in Synaptic Delay during d-ADF

We next determined whether synaptic delay was modified during d-ADF. Synaptic delay is reduced (

Figure 3A) when release probability is elevated [

18] and augmented (

Figure 3B) when the duration of the presynaptic AP is broadened [

22]. Whereas

Pr is clearly elevated during d-ADF, no change in synaptic delay is observed (101 ± 6%, n = 5, paired t-test, p > 0.5;

Figure 3C).

In cortical and hippocampal neurons, d-ADF is due to voltage inactivation of Kv1 channels that broadens the presynaptic AP [

26,

31]. Thus, the absence of change in synaptic delay can be explained by the superposition of the two processes, i.e., the reduction of synaptic delay induced by elevation of

Pr is compensated by the increase in synaptic delay produced by the depolarization-induced AP broadening (

Figure 3C). Supporting this hypothesis, changes in synaptic delay were found to be anticorrelated with the magnitude of d-ADF (linear regression, R = 0.71;

Figure 3C).

4. Discussion

Synaptic delay is determined by both the release probability (

Pr) and the presynaptic AP width in opposite ways. Enhanced

Pr reduces synaptic delay whereas presynaptic AP broadening prolongs synaptic delay. While

Pr is clearly enhanced during d-ADF (as indicated by the reduction in PPR and the increase in CV

-2), we show that the synaptic delay is surprisingly unchanged. Indeed, for a presynaptic increase in synaptic transmission of ~25% the synaptic delay should be reduced by ~15% [

18]. The simplest explanation for this observation, is that opposite changes in synaptic delay occur during d-ADF, i.e., the

Pr-dependent reduction in synaptic delay is compensated by the AP-dependent increase in synaptic delay. This assumption is supported by the fact that changes in synaptic delay were anticorrelated with the magnitude of d-ADF. Small d-ADF corresponds to modest increase in

Pr and so to weak reduction of synaptic delay whereas large d-ADF corresponds to large increase in

Pr and so to large reduction in synaptic delay.

Another possible explanation to account for the stability of the synaptic delay during d-ADF would result from the inactivation of voltage-gated channels by the depolarization. Nav channels are critical for AP conduction along the axon and any reduction in the sodium current such as that produced by voltage-inactivation of Nav channels induced by constant depolarization may reduce conduction speed. However, the fact that synaptic delay changes were anticorrelated with EPSP changes cannot be explained by voltage-inactivation of Nav channels.

Synaptic delay is inversely proportional to the presynaptic calcium concentration [

16]. Calcium concentration is supposed to be slightly elevated during d-ADF for the more proximal synapses as a result of activation of P/Q type calcium channels [

31]. However, this mechanism cannot account for the stability of the synaptic delay as it should reinforce the reduction in synaptic delay. The conduction time depends on several parameters such as the axon diameter and the membrane potential of oligodendrocytes. An increase in axon diameter observed following high-frequency stimulation shortens conduction time [

42]. Depolarization of oligodendrocytes also reduces the conduction time [

43]. However, these mechanisms are unlikely to occur during d-ADF as the rate of the stimulation was kept constant in our experiments and the change in membrane potential was imposed only in the presynaptic neuron.

A similar compensatory phenomenon has already been reported at the mossy-fibre synapse during repetitive stimulation [

22]. In this study, the synaptic delay was found to be reduced during the first 3 stimuli but it progressively increased by the 5

th stimuli because of inactivation of presynaptic Kv1 channels [

44]. Other context-dependent forms of facilitation of synaptic transmission such as hyperpolarization-induced ADF (h-ADF, [

32]) or input-synchrony-dependent facilitation (ISF, [

34]) are due to the modulation of presynaptic AP amplitude as a result of changes in inactivation of axonal Nav channels. As the reduction in presynaptic AP shortens synaptic delay [

22], it is conceivable that no change in synaptic delay would be also observed during both h-ADF [

32] and ISF [

34], as the reduced delay due to elevation of

Pr would be again compensated by an increased delay resulting from the increased AP amplitude.

The functional implications of synaptic modulation without changes in synaptic delay is rather difficult to precisely evaluate. However, d-ADF is supposed to occur during “down” to “up” state transitions [

25] or more generally during global shifts in membrane potential that occur during sleep [

45]. If changes in synaptic delay represent a neural code [

11,

18], it could be important that synaptic timing remains constant during synaptic facilitation that may occur during slow-wave sleep and memory consolidation [

46,

47]. Further investigations will be necessary to understand the precise role of synaptic timing in brain function and coding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SB and DD; data acquisition: SB; methodology, SB and DD; formal analysis, SB and DD; writing—original draft preparation, SB and DD; writing—review and editing, SB and DD; supervision, DD; funding acquisition, DD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by INSERM, CNRS, Aix-Marseille University, French Ministry of Research (to SB), A*Midex (AMX-22-RE-V2-0007 to DD) and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-23-CE-16-0020 to DD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was carried out according to the European and Institutional Guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Council Directive 86/609/EEC and French National Research Council) and approved by the local health authority (D13055-08, Préfecture des Bouches-du-Rhône).

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this study are included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical staff of UNIS for excellent assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grothe, B.; Park, T.J. Sensitivity to Interaural Time Differences in the Medial Superior Olive of a Small Mammal, the Mexican Free-Tailed Bat. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 6608–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, W. Neuronal Synchrony: A Versatile Code for the Definition of Relations? Neuron 1999, 24, 49–65, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.; Lanjuin, A.; Madisen, L.; Zeng, H.; Murthy, V.N.; Uchida, N. Olfactory Cortical Neurons Read out a Relative Time Code in the Olfactory Bulb. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, K.E.; Sawtell, N.B. Neural Readout of a Latency Code in the Active Electrosensory System. Cell Rep 2022, 38, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahissar, E.; Nelinger, G.; Assa, E.; Karp, O.; Saraf-Sinik, I. Thalamocortical Loops as Temporal Demodulators across Senses. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.; Torterolo, P.; Tort, A.B.L. Mechanisms and Functions of Respiration-Driven Gamma Oscillations in the Primary Olfactory Cortex. Elife 2023, 12, e83044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, Y.; Poo, M.-M. Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity: From Synapse to Perception. Physiol Rev 2006, 86, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Axmacher, N. The Role of Phase Synchronization in Memory Processes. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanne, D.; Inglebert, Y. Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity and Memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 80, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieke, F.; Warland, D.; Steveninck, R.D.R.V.; Bialek, W. Spikes: Exploring the Neural Code; MIT Press, 1999; ISBN 978-0-262-68108-7. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, S.; Delorme, A.; Van Rullen, R. Spike-Based Strategies for Rapid Processing. Neural Netw 2001, 14, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalk, M.; Gutkin, B.; Denève, S. Neural Oscillations as a Signature of Efficient Coding in the Presence of Synaptic Delays. Elife 2016, 5, e13824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, A.; Belatreche, A.; Li, Y.; Cosma, G.; Maguire, L.P.; McGinnity, T.M. A Review of Learning in Biologically Plausible Spiking Neural Networks. Neural Networks 2020, 122, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, B.L.; Regehr, W.G. Timing of Synaptic Transmission. Annu Rev Physiol 1999, 61, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W.; Faber, D.S. Modulation of Synaptic Delay during Synaptic Plasticity. Trends in Neurosciences 2002, 25, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felmy, F.; Neher, E.; Schneggenburger, R. The Timing of Phasic Transmitter Release Is Ca2+-Dependent and Lacks a Direct Influence of Presynaptic Membrane Potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15200–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, J.H.; Sakmann, B. Control of Synaptic Strength and Timing by the Release-Site Ca2+ Signal. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudkkazi, S.; Carlier, E.; Ankri, N.; Caillard, O.; Giraud, P.; Fronzaroli-Molinieres, L.; Debanne, D. Release-Dependent Variations in Synaptic Latency: A Putative Code for Short- and Long-Term Synaptic Dynamics. Neuron 2007, 56, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.J.; Cheetham, C.E.; Liu, Y.; Bennett, S.H.; Albieri, G.; Jorstad, A.A.; Knott, G.W.; Finnerty, G.T. Delayed and Temporally Imprecise Neurotransmission in Reorganizing Cortical Microcircuits. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 9024–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine, G.J.; Charlton, M.P.; Smith, S.J. Calcium Entry and Transmitter Release at Voltage-Clamped Nerve Terminals of Squid. J Physiol 1985, 367, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedchyshyn, M.J.; Wang, L.-Y. Activity-Dependent Changes in Temporal Components of Neurotransmission at the Juvenile Mouse Calyx of Held Synapse. J Physiol 2007, 581, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudkkazi, S.; Fronzaroli-Molinieres, L.; Debanne, D. Presynaptic Action Potential Waveform Determines Cortical Synaptic Latency. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2011, 589, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awatramani, G.B.; Price, G.D.; Trussell, L.O. Modulation of Transmitter Release by Presynaptic Resting Potential and Background Calcium Levels. Neuron 2005, 48, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alle, H.; Geiger, J.R.P. Combined Analog and Action Potential Coding in Hippocampal Mossy Fibers. Science 2006, 311, 1290–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Hasenstaub, A.; Duque, A.; Yu, Y.; McCormick, D.A. Modulation of Intracortical Synaptic Potentials by Presynaptic Somatic Membrane Potential. Nature 2006, 441, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, M.H.P.; Letzkus, J.J.; Stuart, G.J. Axon Initial Segment Kv1 Channels Control Axonal Action Potential Waveform and Synaptic Efficacy. Neuron 2007, 55, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.; Ruiz, A.; Henneberger, C.; Kullmann, D.M.; Rusakov, D.A. Analog Modulation of Mossy Fiber Transmission Is Uncoupled from Changes in Presynaptic Ca2+. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 7765–7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alle, H.; Geiger, J.R.P. Analog Signalling in Mammalian Cortical Axons. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008, 18, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhours, B.; Trigo, F.F.; Marty, A. Somatic Depolarization Enhances GABA Release in Cerebellar Interneurons via a Calcium/Protein Kinase C Pathway. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 5804–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, J.M.; Chiu, D.N.; Jahr, C.E. Ca(2+)-Dependent Enhancement of Release by Subthreshold Somatic Depolarization. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialowas, A.; Rama, S.; Zbili, M.; Marra, V.; Fronzaroli-Molinieres, L.; Ankri, N.; Carlier, E.; Debanne, D. Analog Modulation of Spike-Evoked Transmission in CA3 Circuits Is Determined by Axonal Kv1.1 Channels in a Time-Dependent Manner. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2015, 41, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, S.; Zbili, M.; Bialowas, A.; Fronzaroli-Molinieres, L.; Ankri, N.; Carlier, E.; Marra, V.; Debanne, D. Presynaptic Hyperpolarization Induces a Fast Analogue Modulation of Spike-Evoked Transmission Mediated by Axonal Sodium Channels. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla de San Martin, J.; Trigo, F.F.; Kawaguchi, S.-Y. Axonal GABAA Receptors Depolarize Presynaptic Terminals and Facilitate Transmitter Release in Cerebellar Purkinje Cells. J Physiol 2017, 595, 7477–7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbili, M.; Rama, S.; Yger, P.; Inglebert, Y.; Boumedine-Guignon, N.; Fronzaroli-Moliniere, L.; Brette, R.; Russier, M.; Debanne, D. Axonal Na+ Channels Detect and Transmit Levels of Input Synchrony in Local Brain Circuits. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaay4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, F.; Kawaguchi, S.-Y. Analogue Signaling of Somatodendritic Synaptic Activity to Axon Enhances GABA Release in Young Cerebellar Molecular Layer Interneurons. Elife 2023, 12, e85971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; McCormick, D.A. Selective Control of Cortical Axonal Spikes by a Slowly Inactivating K+ Current. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 11453–11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foust, A.J.; Yu, Y.; Popovic, M.; Zecevic, D.; McCormick, D.A. Somatic Membrane Potential and Kv1 Channels Control Spike Repolarization in Cortical Axon Collaterals and Presynaptic Boutons. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 15490–15498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debanne, D.; Boudkkazi, S.; Campanac, E.; Cudmore, R.H.; Giraud, P.; Fronzaroli-Molinieres, L.; Carlier, E.; Caillard, O. Paired-Recordings from Synaptically Coupled Cortical and Hippocampal Neurons in Acute and Cultured Brain Slices. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, G.; Yang, D.; Ding, C.; Feldmeyer, D. Unveiling the Synaptic Function and Structure Using Paired Recordings From Synaptically Coupled Neurons. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, S.D.; McPhedrain, R.; Madranges, J.F.; Kennedy, T.E.; Ruthazer, E.S. Approaches and Limitations in the Investigation of Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, J.A.; Thomazeau, A.; Watanabe, A.; Li, S.S.Y.; Sjöström, P.J. A Practical Guide to Using CV Analysis for Determining the Locus of Synaptic Plasticity. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chéreau, R.; Saraceno, G.E.; Angibaud, J.; Cattaert, D.; Nägerl, U.V. Superresolution Imaging Reveals Activity-Dependent Plasticity of Axon Morphology Linked to Changes in Action Potential Conduction Velocity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Abe, Y.; Fujii, S.; Tanaka, K.F. Oligodendrocytic Na+-K+-Cl- Co-Transporter 1 Activity Facilitates Axonal Conduction and Restores Plasticity in the Adult Mouse Brain. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.R.; Jonas, P. Dynamic Control of Presynaptic Ca(2+) Inflow by Fast-Inactivating K(+) Channels in Hippocampal Mossy Fiber Boutons. Neuron 2000, 28, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torao-Angosto, M.; Manasanch, A.; Mattia, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Up and Down States During Slow Oscillations in Slow-Wave Sleep and Different Levels of Anesthesia. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.K.; Wilson, M.A. Memory of Sequential Experience in the Hippocampus during Slow Wave Sleep. Neuron 2002, 36, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodt, S.; Inostroza, M.; Niethard, N.; Born, J. Sleep-A Brain-State Serving Systems Memory Consolidation. Neuron 2023, 111, 1050–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).