Submitted:

29 February 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

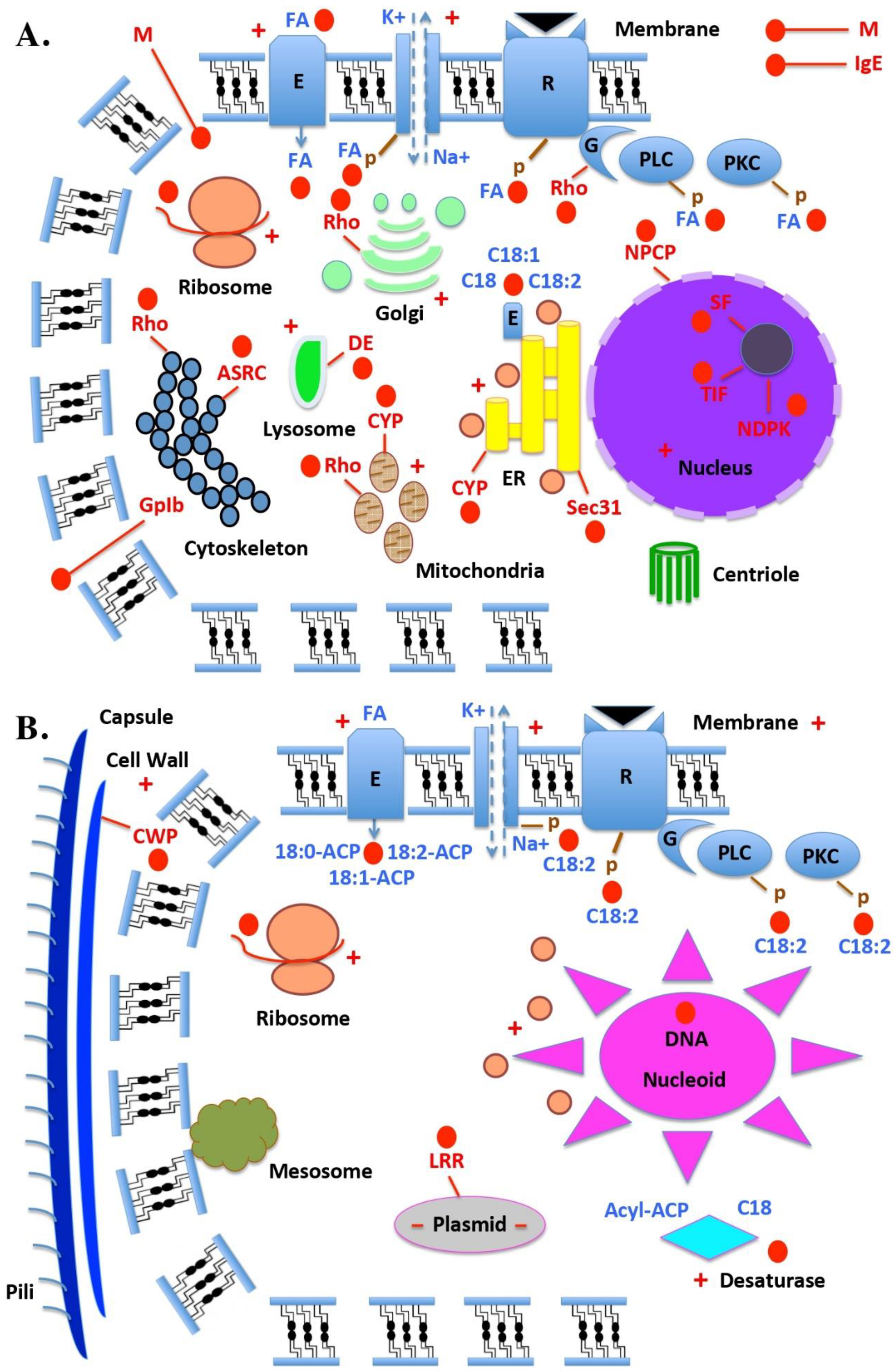

1. Introduction

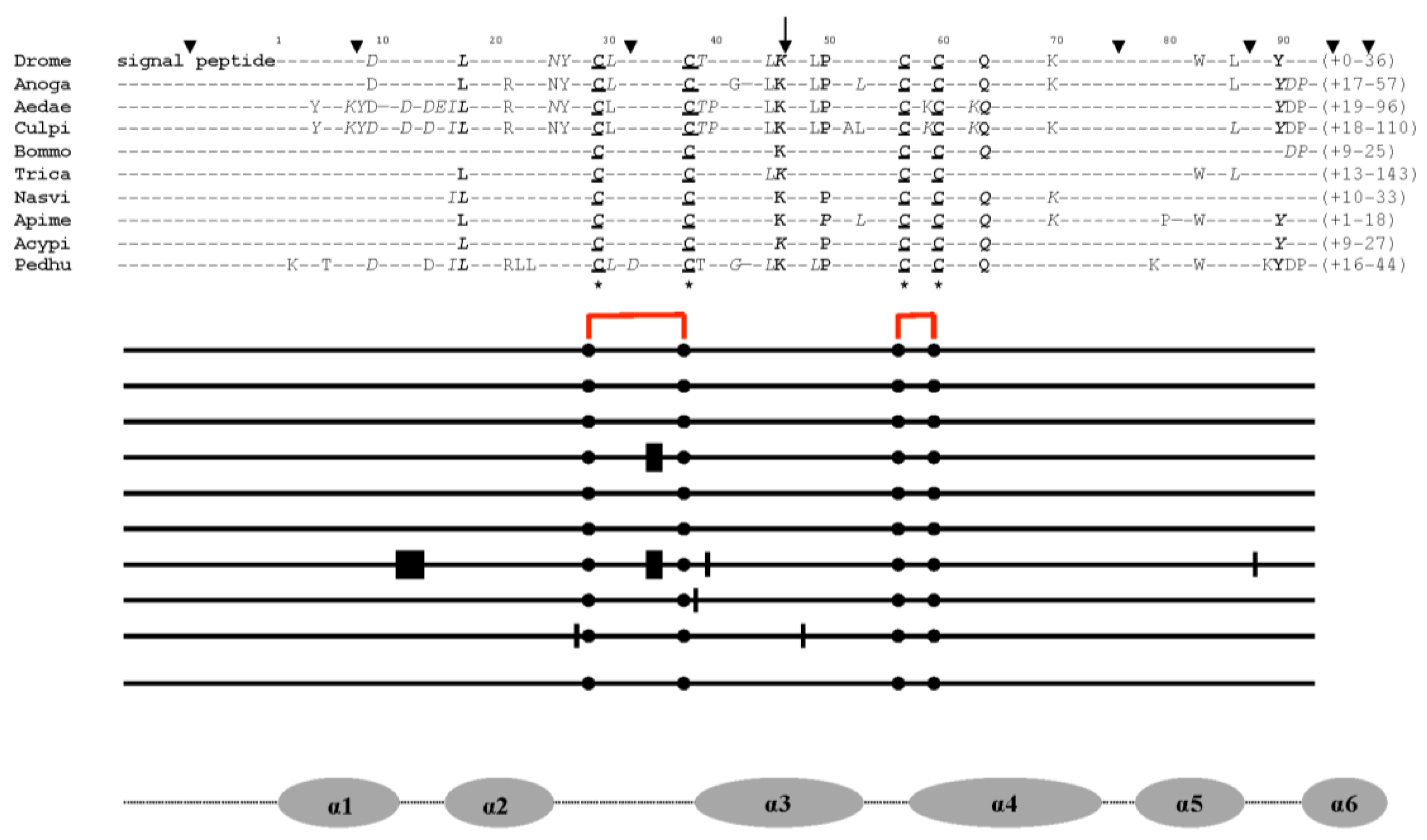

2. Primary Sequence Variation in Various Phenotypes of Insects

3. Existence of “CSPs” in Phenotypes of Bacteria

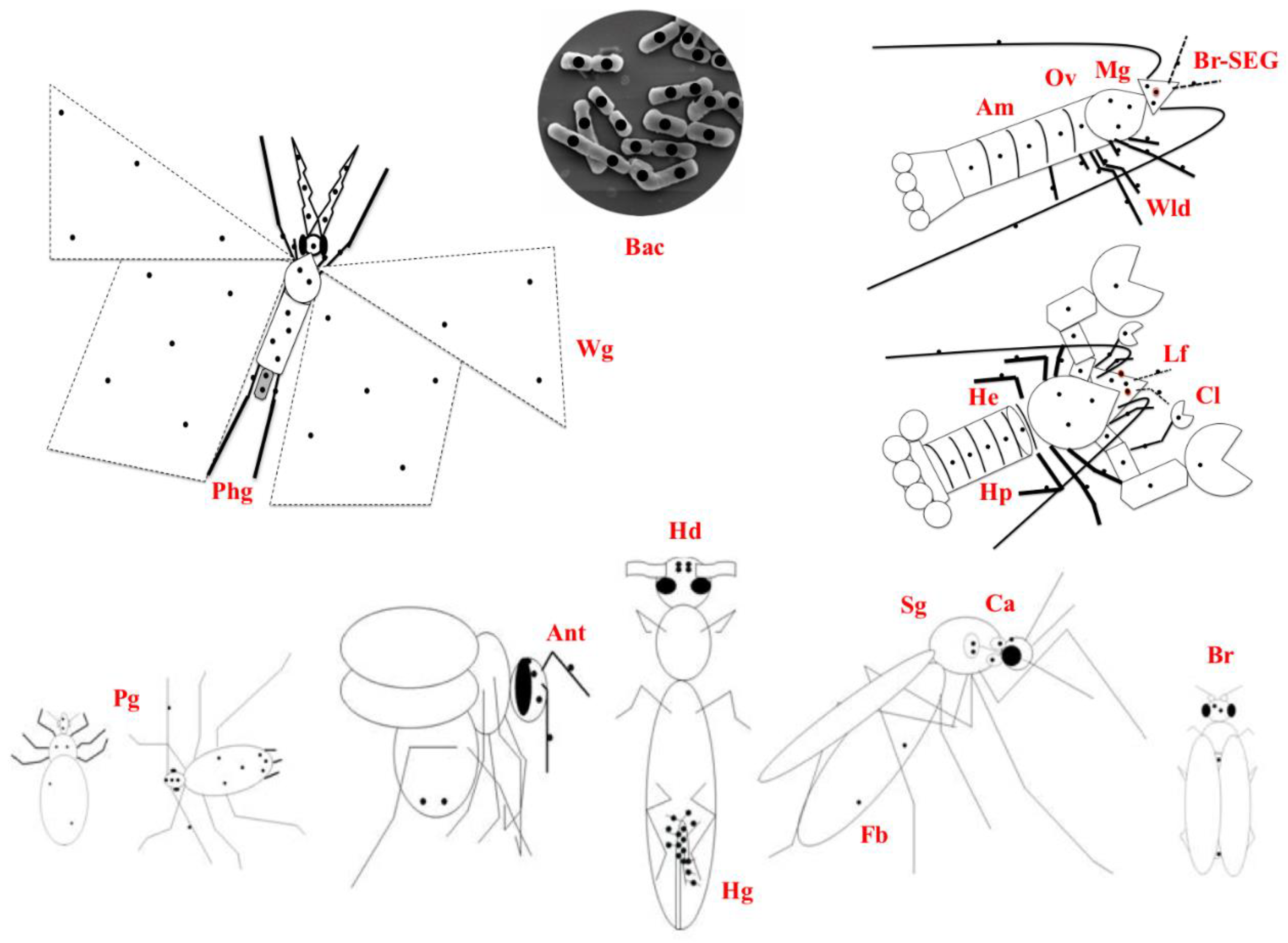

4. Expression Profiling in Development, Organisms, and Tissues

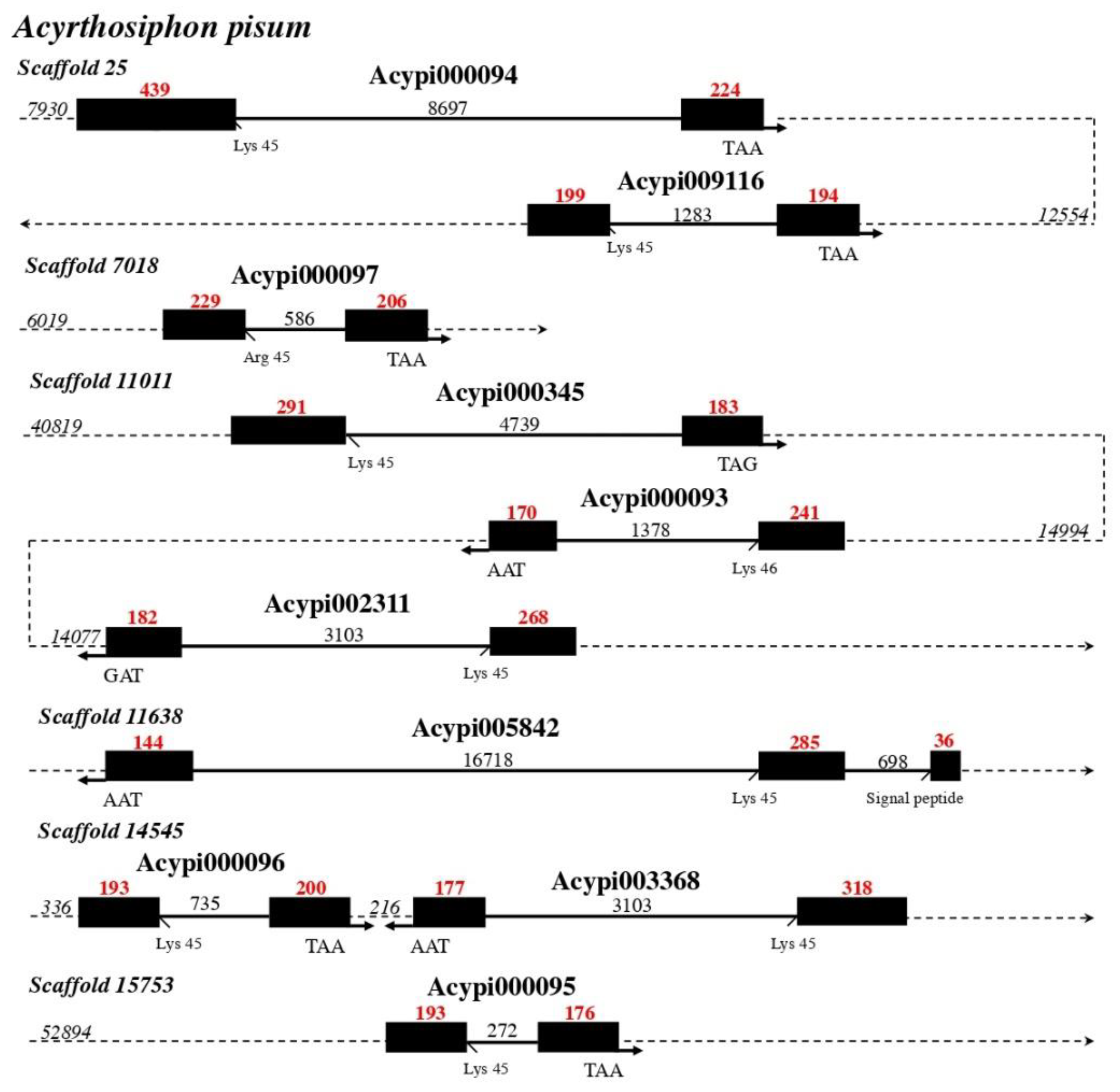

5. The Evolution and Diversity of CSP Genes

6. Ancestral Functions and Lipoid-Binding Properties

7. CSPs’ Intracellular Functions (Gene Regulation to Stress Response)

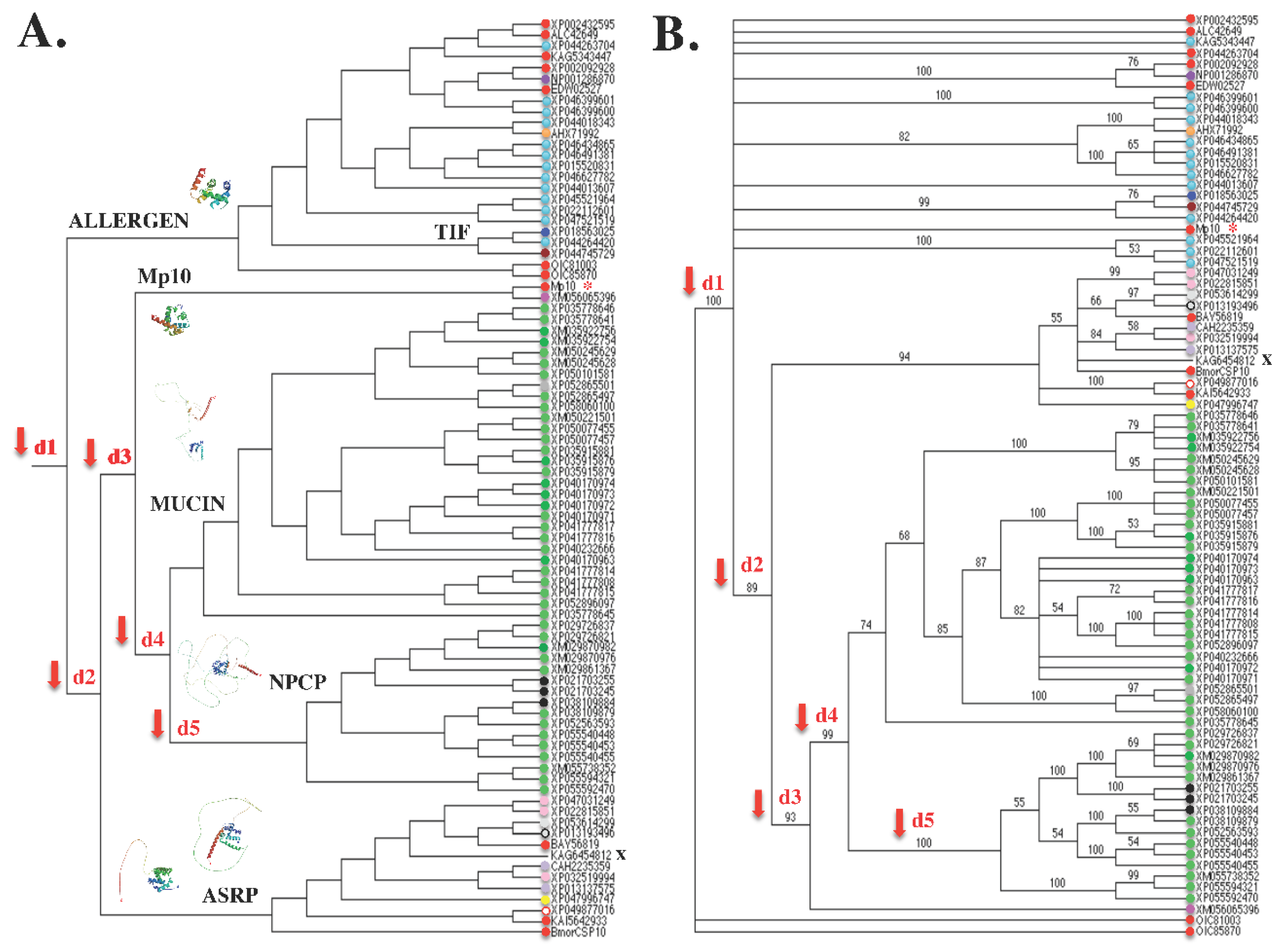

7.1. Evolutionary Evidence Derived from Amino Acid Sequence Phylogenetic Analysis

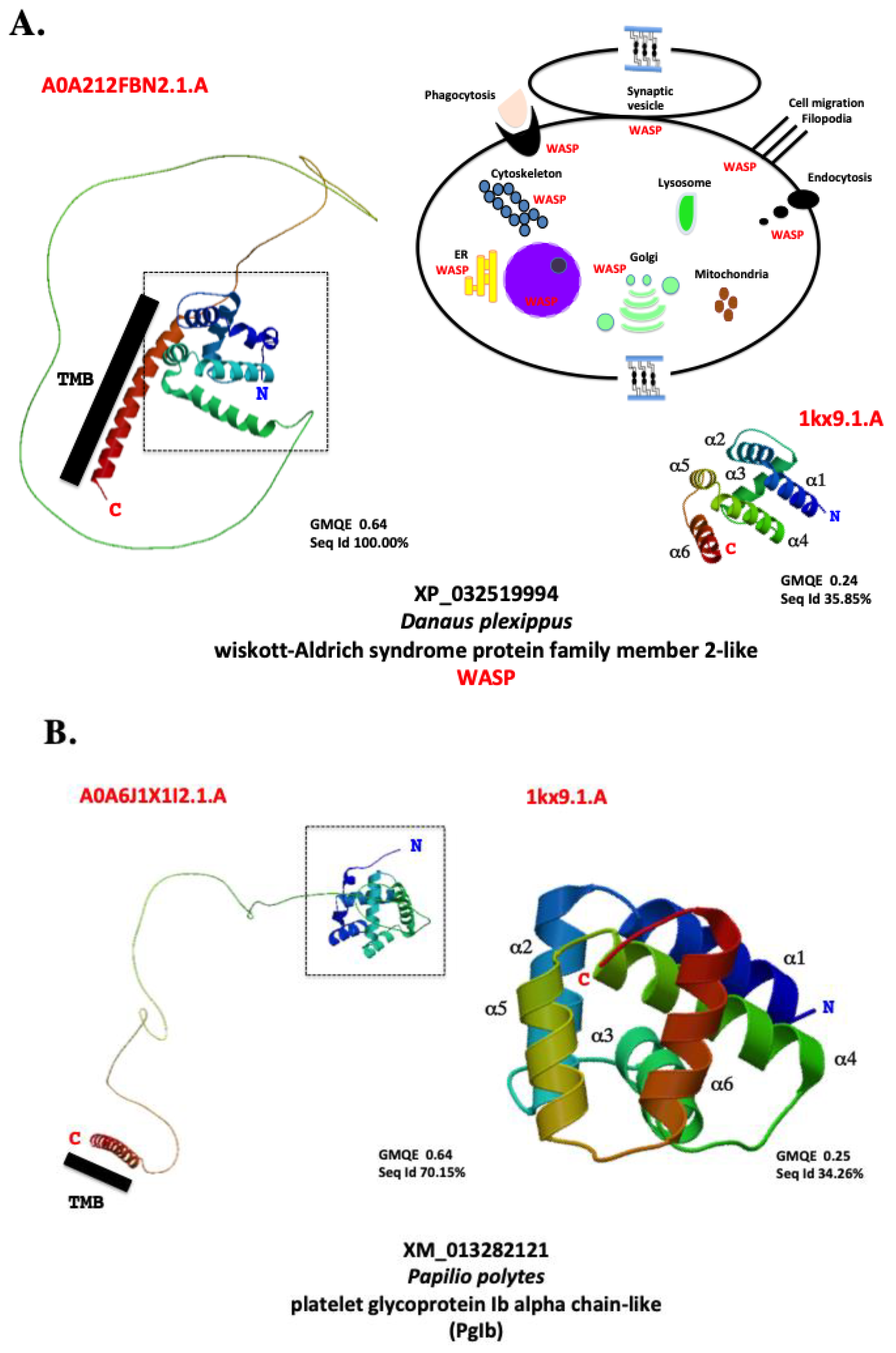

7.2. Molecular Evidence Derived from Amino Acid Sequence Modeling Analysis

7.3. Cellular Evidence Derived from Location, Size, Structure, and Expression in Viruses and Microbes

8. To Design “CSP”, New Terminology Is Needed: Structure or Function?

8. Concluding Remark

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

| 4CSP: 4 Cysteines Soluble Proteins AA: Arachidonic acid AcrR: Regulator of adjacent acrAB efflux genes - functional protein of the transcriptional regulation system that confers bacterial resistance to the antibiotic tetracycline (see TetR and TFTR) - Regulated by FA lipids Acypi: Acyrthosiphum pisum (pea aphid) Aedae: Aedes aegypti (dengue yellow fever mosquito) Anoga: Anopheles gambiae (malaria mosquito) Allergen Tha p 1: IgE-binding protein (15 kDa) and major allergen of pine processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa, Thapi) - variant 1.0101 Apime: Apis mellifera (honey bee) Arp2/3: Actin related protein 2/3 complex ASRC: Actin skeleton regulatory complex ASRP: Actin skeleton regulatory protein Avd: Accessory variability determinant Bacil: Bacillus B-CSP: Bacterial “Chemosensory protein” BioNJ: Bio (improved version) of the Neighbor Joining algorithm based on simple model of sequence data BLASTn: Nucleotide BLAST BLLF1: Epstein-Barr virus envelope glycoprotein encoded by BLLF1 gene Bommo: Bombyx mori (silkworm moth) BemtaCSP1: Bemisia tabaci “Chemosensory Protein”-1 (LA-binding protein) CA: Corpora allata Cocse: Coccinella septempunctata (seven-spot ladybird) CSP: Chemosensory protein Culpi: Culex pipiens (common house mosquito) CWA: Cell wall anchored CWP: Cell wall protein CYP: Cytochrome P450 Cys: Cysteine DAN4: Cell wall mannoprotein expressed under delayed anaerobic conditions (Saccharomyces) Danpl: Danaus plexippus (monarch butterfly) Dd-Rp: DNA-dependent RNA polymerase DE: Degradative enzyme DGR: Diversity generating retroelement DNA-BP: Deoxyribonucleic acid-binding protein DNA-RP: Deoxyribonucleic acid-regulatory protein DP: Diphosphate Drome: Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) Droso: Drosophila species EA: Elaidic acid Ebsp: Ejaculatory bulb-specific protein Epiba: Episyrphus balteatus (marmalade hoverfly) ER: Endoplasmic reticulum EST: Expressed Sequence Tag Eupco: Eupeodes corollae (migrant overfly) FA: Fatty acid GC: Guanine-cytosine content GMQE: Global Model Quality Estimate GTP: Guanosine triphosphate HSV: Herpesvirus IgE-BP: Immunoglobulin E-binding protein Iphpo: Iphiclides podalirius (scarce swallowtail) Jg5928: major outer envelope protein JH: Juvenile hormone JHRP: Juvenile hormone-related protein HSV: Herpesvirus LA: Linoleic acid (C18:2) Locmi: Locusta migratoria (migratory locust) LRR: Leucine-rich repeat protein complex M: Mucin Manse: Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm, sphinx moth) MP: Maximum parsimony Mp10: Myzpe p10-like protein Myzpe: Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) NNK: Nuclear nucleoside kinase NDPK: Nucleoside diphosphate kinase NPCP: Nuclear pore complex protein Nasvi: Nasonia vitripennis (parasitoid jewel wasp) OBP: Odorant-binding protein OR: Olfactory receptor OS-D: Olfactory sensilla-type D protein P: Phosphate P10: Peram 10 kDa protein from regenerating legs PAN: Hexameric ATPase complex PAN-1: Protein encoded by the pan-1 gene in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans Pappo: Papilio polytes (common Mormon) PAUP: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony Pedhu: Pediculus humanus humanus (human body louse) Peram: Periplaneta americana (American cockroach) PBP: Pheromone-binding protein PgIb: Platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha chain-like Phk: Pherokine (hemolymph protein) PKC: Protein kinase C PLC: Phospholipase C Pol: Polymerase Ras: Family of GTPases derived from rat sarcoma virus Rho: Family of GTPases, family of small (~21 kDa) signaling G proteins, subfamily of the Ras superfamily RhoGAP: Rho GTPase-activating protein, regulator of the Rho-related protein family, crucial in many cellular processes, motility, contractility, growth, differentiation, and development RickA: Rickettsia (conorii) surface protein A (activator of Arp2/3) RNA-BP: Ribonucleic acid-binding protein SamkC: Serine/Threonine-protein kinase (from Social amoeba) SA: Stearic acid SAP: Sensory appendage protein Sec31: Protein transport protein encoded by the SEC31A gene (human) SF: Splicing factor TERT: Telomerase reverse transcriptase TetR: Tetracycline repressor TFTR: TetR-family transcriptional regulator TIF: Transcription initiation factor TP: Triphosphate Trica: Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle) TSSC1: Tumor suppressing subtransferable candidate 1 UL36: Large tegument protein deneddylase encoded by UL36 gene (herpesviridae) UPGMA: Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean Uralo: Uranotaenia lowii (pale-footed Uranotaenia) WAS/WASL: Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome/ Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome-like protein WASP: Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein XRE (or Xre): Xenobiotic response element family of DNA-binding transcriptional regulators YhbY: RNA-binding protein (folded like TIF) encoded by YhbY gene (Escherichia coli) YLPM1: YLP motif containing 1 encoded by YLPM1 gene (human) |

References

- Hoffmann, K.H.; Meyerinng-Vos, M.; Lorenz, M.W. Allatostatins and allatotropins: is the regulation of corpora allata activity their primary function? Eur. J. Entomol. 1999, 96, 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Picimbon, J.F. Renaming Bombyx mori chemosensory proteins. Int. J. Bioorg. Chem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, R.G.; Riddiford, L.M. Pheromone binding and inactivation by moth antennae. Nature, 1981, 293, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F.; Leal, W.S. Olfactory soluble proteins of cockroaches. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 30, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, S.; Ceron, F.; Scaloni, A.; Monti, M.; Monteforti, G.; Minnocci, A.; Petacchi, R.; Pelosi, P. Purification, structural characterization, cloning and immunocytochemical localization of chemoreception proteins from Schistocerca gregaria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 262, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F. Biochemistry and evolution of CSP and OBP proteins. In Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The Biosynthesis and Detection of Pheromones and Plant Volatiles; Blomquist, G.J., Vogt, R.G., Eds; Elsevier Academic Press, London & San Diego, UK & USA, 2003; pp. 539-566. [CrossRef]

- Lartigue, A.; Campanacci, V.; Roussel, A.; Larsson, A.M.; Jones, T.A.; Tegoni, M; Cambillau, C. X-ray structure and ligand binding study of a moth chemosensory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 32094-32098. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, S.; Zídek, L.; Löfstedt, C.; Picimbon, J.F.; Sklenar, V. 1 H, 13 C, and 15 N resonance assignment of Bombyx mori chemosensory protein 1 (BmorCSP1). J. Biomol. NMR 2006, 36, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, S.; Chmelik, J.; Zídek, L.; Padrta, P.; Novak, P.; Zdrahal, Z.; Picimbon, J.F.; Löfstedt, C.; Sklenar, V. Structure of Bombyx mori Chemosensory Protein 1 in solution. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2007, 66, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, S.; Crescenzi, O.; Sanfelice, D.; Ab, E.; Wechsel-berger, R.; Angeli, S.; Scaloni, A.; Boelens, R.; Tancredi, T.; Pelosi, P.; Picone, D. Solution structure of a chemosensory protein from the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; Xiao, N.; Tang, J.; Dong, X.; Xie, W. The crystal structure of the Spodoptera litura Chemosensory Protein CSP8. Insects 2021, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanacci, V.; Lartigue, A.; Hällberg, B.M.; Jones, T.A.; Giuici-Orticoni, M.T.; Tegoni, M.; Cambillau, C. Moth chemosensory protein exhibits drastic conformational changes and cooperativity on ligand binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5069–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbah, A.; Campanacci, V.; Lartigue, A.; Tegoni, M.; Cambillau, C.; Darbon, H. Solution structure of a chemosensory protein from the moth Mamestra brassicae. Biochem. J. 2003, 369, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, N.; Bu, X.; Liu, Y.Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, G.X.; Fan, Z.X.; Bi, Y.P.; Yang, L.Q.; Lu, Q.N.; Rajashekar, B.; Leppik, G.; Kasvandik, S.; Picimbon, J.F. Molecular evidence of RNA editing in the Bombyx chemosensory protein family. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picimbon, J.F. Evolution of protein physical structures in insect chemosensory systems. In Olfactory Concepts of Insect Control-Alternative to Insecticides; Picimbon, J.F., Ed; Vol. 2, Springer Nature AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 231-263. [CrossRef]

- Picimbon, J.F.; Dietrich, K.; Breer, H.; Krieger, J. Chemosensory proteins of Locusta migratoria (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 30, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F.; Dietrich, K.; Angeli, S.; Scaloni, A.; Krieger, J.; Breer, H.; Pelosi, P. Purification and molecular cloning of chemosensory proteins from Bombyx mori. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2000, 44, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F.; Dietrich, K.; Krieger, J.; Breer, H. Identity and expression pattern of chemosensory proteins in Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 31, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanner, K.W.; Isman, M.B.; Feng, Q.; Plettner, E.; Theilmann, D.A. Developmental expression patterns of four chemosensory protein genes from the Eastern spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005, 14, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F. Chapter three—bioinformatic, genomic and evolutionary analysis of genes: a case study in Dipteran CSPs. Meth. Enzymol. 2020, 642, 35–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Xue, L.; Han, J.; Yu, D.; Kang, L. CSP and Takeout genes modulate the switch between attraction and repulsion during behavioral phase change in the migratory locust. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Blázquez, R.; Chen, B.; Kang, L.; Bakkali, M. Evolution, expression and association of the chemosensory protein genes with the outbreak phase of the two main pest locusts. Sci. Rep. 2018, 7, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, L.; Scaloni, A.; Brandazza, A.; Angeli, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pelosi, P. Chemosensory proteins of Locusta migratoria. Insect Mol. Biol. 2003, 12, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, N.; Guo, X.; Xie, H.Y.; Lou, Q.N.; Bo, L.X.; Liu, G.X.; Picimbon, J.F. Increased expression of CSP and CYP genes in adult silkworm females exposed to avermectins. Insect Sci. 2015, 22, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Picimbon, J.F.; Ji, S.; Kan, Y.; Chuanling, Q.; Zhou, J.J.; Pelosi, P. Multiple functions of an odorant-binding protein in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 372, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.E.; Delannay, C.; Goindin, D.; Deng, L.; Guan, S.; Lu, X.; Fouque, F.; Vega-Rúa, A.; Picimbon, J.F. Cartography of odor chemicals in the dengue vector mosquito (Aedes aegypti L., Diptera/Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 2020, 9, 8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatier, L.; Jouanguy, E.; Dostert, C.; Zachary, D.; Dimarcq, J.L.; Bulet, P.; Imler, J.C. Pherokine-2 and -3: Two Drosophila molecules related to pheromone/odor-binding proteins induced by viral and bacterial infections. Eur. J. Biol. 2003, 270, 3398–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; et al. Biotype expression and insecticide response of Bemisia tabaci chemosensory protein-1. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 85, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, E.; Imler, J.L. Insect immunity; from systemic to chemosensory organs protection. In Olfactory Concepts of Insect Control-Alternative to Insecticides; Picimbon, J.F., Ed; Vol. 2 Springer Nature AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 205-229. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; Ma, H.M.; Xie, Y.N.; Xuan, N.; Guo, X.; Fan, Z.X.; Rajashekar, B.; Arnaud, P.; Offmann, B.; Picimbon, J.F. Biotype characterization, developmental profiling, insecticide response and binding property of Bemisia tabaci chemosensory proteins: role of CSP in insect defense. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11, e0154706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- [Liu, G.X.; Xuan, N.; Rajashekar, B.; Arnaud, P.; Offmann, B.; Picimbon, J.F. Comprehensive history of CSP genes: evolution, phylogenetic distribution, and functions. Genes 2020, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F. RNA mutations: source of life. Gene Technol. 2014, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, N.; Rajashekar, B.; Picimbon, J.F. DNA and RNA-dependent polymerization in editing of Bombyx chemosensory protein (CSP) gene family. Agri Gene 2019, 12, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picimbon, J.F. RNA + ribosome peptide editing in chemosensory proteins (CSPs), a new theory for the origin of life on Earth’s crust. J. Mol. Evol. 2024. submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, N.; Rajashekar, B.; Kasvandik, S.; Picimbon, J.F. Structural components of chemosensory protein mutations in the silkworm moth, Bombyx mori. Agri Gene 2016, 2, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picimbon, J.F. A new view of genetic mutations. Australas. Med. J. 2017, 10, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; Arnaud, P.; Offmann, B.; Picimbon, J.F. Genotyping and bio-sensing chemosensory proteins in insects. Sensors 2017, 17, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; Yue, S.; Rajashekar, B.; Picimbon, J.F. Expression of chemosensory protein (CSP) structures in Pediculus humanus corporis and Acinetobacter baumannii. SOJ Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2019, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picimbon, J.F. Synthesis of odorant reception–suppressing agents: odorant binding proteins (OBPs) and Chemosensory Proteins (CSPs) as molecular targets for pest management. In Biopesticides of plant origin; Regnault-Roger, C., Philogène, B., Vincent, C., Eds; Intercept Ltd, Hampshire, UK, 2005; pp.245-266.

- Zhu, J.; Iovinella, I.; Dani, F.R.; Pelosi, P.; Wang, G. Chemosensory proteins: A versatile binding family. In Olfactory Concepts of Insect Control-Alternative to Insecticides; Picimbon, J.F., Ed; Vol. 2, Springer Nature AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 147-169. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; Picimbon, J.F. Bacterial origin of insect chemosensory odor-binding proteins. Gene Transl. Bioinf. 2017, 3, e1548. [Google Scholar]

- Ghai, R.; Mizuno, C.M.; Picazo, A.; Camacho, A.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Metagenomics uncovers a new group of low GC and ultra-small marine Actinobacteria. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gonsior, M.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Jiao, N.; Chen, F. Microbial transformation of virus-induced dissolved organic matter from picocyanobacteria: coupling of bacterial diversity and DOM chemodiversity. ISME J. 2019, 13, 2551–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, H.; Guyet, U.; Leconte, J.; Farrant, G.K.; Alric, B.; Ratin, M.; Ostrowski, M.; Ferrieux, M.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Hoebeke, M.; Siltanen, J.; Le Corguillé, G.; Corre, E.; Wincker, P.; Scanlan, D.J.; Eveillard, D.; Partensky, F.; Garczarek, L. Differential global distribution of marine picocyanobacteria gene clusters reveals distinct niche-related adaptive strategies. ISME J. 2023, 17, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, L.D.J.; Sterk, P.J.; Schultz, M.J. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: A systemic review. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taga, M.E.; Bassler, B.L. Chemical communication among bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14549–14554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Junior, E.A.; Ruzzini, A.C.; Paludo, C.R.; Nascimento, F.S.; Currie, C.R.; Clardy, J.; Pupo, M.T. Pyrazines from bacteria and ants: convergent chemistry within an ecological niche. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkin, L.C.; Friesen, K.S.; Flinn, P.W.; Oppert, B. Venom gland components of the ectoparasitoid wasp, Anisopteromalus calandrae. J. Venom Res. 2015, 6, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F. RNA mutations in the moth pheromone gland. RNA Dis. 2014b, 1, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celorio-Mancera, Mde L.; Sundmalm, S.M; Vogel, H.; Rutishauser, D.; Ytterberg, A.J.; Zubarv, R.A.; Janz, N. Chemosensory proteins, major salivary factors in caterpillar mandibular glands. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 42, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Caballero, N.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Ribeiro, J.M.C.; Cuervo, P.; Brazil, R.P. Transcriptome exploration of the sex pheromone gland of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae). Parasit. Vectors 2013, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Guo, H.; Huang, L.Q.; Pelosi, P.; Wang, C.Z. (2014) Unique function of a chemosensory protein in the proboscis of two Helicoverpa species. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 1821–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Iovinella, I.; Dani, F.R.; Liu, Y.L.; Huang, L.Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.Z.; Pelosi, P.; Wang, G. Conserved chemosensory proteins in the proboscis and eyes of Lepidoptera. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 12, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedra, J.H.; Brandt, A.; Li, H.M.; Westerman, R.; Romero-Serverson, J.; Pollack, R.J.; Murdock, L.L.; Pittendrigh, B.R. Transcriptome identification of putative genes involved in protein catabolism and innate immune response in human body louse (Pediculicidae: Pediculus humanus). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 33, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkness, E.F.; et al. Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12168–12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigenobu, S.; Richards, S.; Cree, A.G.; Morioka, M.; Fukatsu, T.; Kudo, T.; Miyagishima, S.; Gibbs, R.A.; Stern, D.L.; Nakabashi, A. A full-length cDNA resource for the pea aphid, Acyrtosiphon pisum. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010, 19, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittendrigh, B.R.; Clark, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, K.S.; Sun, W.; Steele, L.D.; Seong, K.M. Body lice: from the genome project to functional genomics and reverse genetics. In Short views on insect genomics and proteomics, Entomology in focus; Raman, C., Goldsmith, M., Agunbiade, T., Eds; Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2015 ; pp. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, M.; Legeai, F.; Rispe, C. Comparative analysis of the Acyrthosiphon pisum genome and expressed sequence tag-based gene sets from other aphid species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2019, 19, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, K.W.; Willis, L.G.; Theilmann, D.A.; Isman, M.B.; Feng, Q.; Plettner, E. Analysis of the insect os-d-like gene family. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004, 30, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forêt, S.; Wanner, K.W.; Maleszka, R. Chemosensory proteins in the honeybee: Insights from the annotated genome, comparative analysis and expression profiling. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 37, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, G.J.; Tittiger, C.; Jurenka, R. Cuticular hydrocarbons and pheromones of arthropods. In Oils and Lipids: Diversity, Origin, Chemistry and Fate; Wilkes, H., Ed; Hydrocarbons, Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, Springer, Cham, Swizerland, 2018; pp. 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Maleszka, J.; Forêt, S.; Saint, R.; Maleszka, R. RNAi-induced phenotypes suggest a novel role for a chemosensory protein CSP5 in the development of embryonic integument in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Dev. Genes Evol. 2007, 217, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spealman, P.; Burrelli, J.; Gresham, D. Inverted duplicate DNA sequences increase translocation rates through sequencing nanopores resulting in reduced base calling accuracy. Nucl. Acids Res. 2020, 48, 4940–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R.L.; Takada, H.; Kawakami, K. Chromosomal rearrangement involved in insecticide resistance of Myzus persicae. Nature 1978, 271, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrioli, M.; Melchiori, G.; Panini, M.; Chiesa, O.; Giordano, R.; Mazzoni, E.; Manicardi, G.C. Analysis of the extent of synteny and conservation in the gene order in aphids: a first glimpse from the Aphis glycines genome. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 113, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, T.C.; Wouters, R.H.M.; Mugford, S.T.; Swarbreck, D.; van Oosterhout, C.; Hogenhout, S.A. Chromosome-scale genome assemblies of aphids reveal extensively rearranged autosomes and long-term conservation of the X chromosome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 856–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.X.; Ma, H.M.; Xie, H.Y.; Xuan, N.; Picimbon, J.F. Sequence variation of Bemisia tabaci Chemosensory protein 2 in cryptic species B and Q: new DNA markers for whitefly recognition. Gene 2016, 576, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blobel, G. Protein targeting (Nobel lecture). Chembiochem. 2000, 1, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matlin, K.S. The strange case of the signal recognition particle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A.; Batey, R.T. Structural insights into the signal recognition particle. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004, 73, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, A.; Kawasaki, K.; Kubo, T.; Natori, S. Purification and localization of p10, a novel protein that increases in nymphal regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach). Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1992, 36, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Brandazza, A.; Navarrini, A.; Ban, L.; Zhang, S.; Steinbrecht, R.A.; Zhang, L.; Pelosi, P. Expression and immunolocalization of odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins in locusts. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.S.; Kleineidam, C.J.; Leitinger, G.; Römer, H. Ultrastructure and electrophysiology of thermosensitive sensilla coeloconica in a tropical katydid of the genus Mecopoda (Orthoptera, Tettigoniidae). Arthr. Struct. Dev. 2018, 47, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, B.J.; Utterback, T.; Pertea, G.; Koo, H.; Mori, A.; Schneider, J.; Lovin, D.; de Bruyn, B.; Song, Z.; Raikhel, A.; de Fatima, B.M.; Casavant, T.; Soares, B.; Severson, D. Aedes aegypti cDNA sequencing. NCBI 2005, #DV263125, DV263127, DV289920, DV289921, DV297938, DV314711, DV314712, DV316589, DV316619, DV334734, DV334735, DV335057, DV335058, DV344048, DV347318, DV347319, DV365747, DV365766, DV357763, DV368339, DV368340, DV393559, DV400785, DV400787, “…”.

- Verjovski-Almeida, S.; Eiglmeier, K.; El-Dorry, H.; Gomes, S.L.; Menck, S.F.M.; Nascimento, A.L.; Roth, C.W. FAPESP and Institut Pasteur/AMSUD Network Aedes aegypti cDNA sequencing project. NCBI 2005, #EG001037.

- Noriega, F.G.; Ribeiro, J.M.C.; Koener, J.F.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Hernandez-Martinez, S.; Pham, V.M.; Feyereisen, R. Comparative genomics of insect juvenile hormone biosynthesis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 36, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nene, V.; Worthman, J.R.; Lawson, D.; et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science 2007, 22, 1718–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.H.; Pham, V.; Jablonka, W.; Goodman, W.G.; Ribeiro, J.M.C.; Andersen, J.F. A mosquito hemolymph odorant-binding protein family member specifically binds juvenile hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15329–15339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, H.; Borst, D.; Baker, F.C.; Reuter, C.C.; Tsai, L.W.; Schooley, D.A.; Carrasco, C.; Sinkus, M. Identification of a juvenile-hormone-like compound in a Crustacean. Science 1987, 235, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindra, M.; Palli, S.R.; Riddiford, L.M. The juvenile hormone signaling pathway in insect development. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayre, M.; Strambi, C.; Strambi, A. Neurogenesis in an adult insect brain and its hormonal control. Nature 1994, 368, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.; Rossler, W. Plasticity and modulation of olfactory circuits in insects. Cell Tiss. Res. 2021, 383, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, H.X.; Chen, D.B.; Zheng, X.X.; Ma, H.F.; Li, Y.P.; Li, Q.; Xia, R.X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.R.; Liu, Y.Q.; Qin, L. Transcriptomic analysis of the prothoracic gland from two lepidopteran insects, domesticated silkmoth Bombyx mori and wild silkmoth Antheraea pernyi. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hrithik, M.T.H.; Roy, M.C.; Bode, H.; Kim, Y. Phurelipids, produced by the entomopathogenic bacteria, Photorhabdus, mimic juvenile hormone to suppress insect immunity and immature development. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 193, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, M.; Wada-Katsumata, A.; Fujikawa, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Yokohari, F.; Satoji, Y.; Nisimura, T.; Yamaoka, R. Ant nestmate and non-nestmate discrimination by a chemosensory sensillum. Science 2005, 309, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.I.; Prince, D.; Pitino, M.; Maffei, M.E.; Win, J.; Hogenhout, S.A. A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (green peach aphid). PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.A.; Stam, R.; Warbroek, T.; Bos, J.I. Mp10 and Mp42 from the aphid species Myzus persicae trigger plant defenses in Nicotiana benthamiana through different activities. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 2014, 27, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.Y.; Zheng, Y. (2003) Rho GTPase-activating proteins in cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2003, 13, P13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouin, E.; Egile, C.; Dehoux, P.; Villiers, V.; Adams, J.; Gertler, F.; Li, R.; Cossart, P. The RickA protein of Rickettsia conorii activates the Arp2/3 complex. Nature 2004, 427, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronmiller, E.; Toor, D.; Shao, N.C.; Kariyawasam, T.; Wang, M.H.; Lee, J.H. Cell wall integrity signaling regulates cell wall-related gene expression in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. The molecular clock and estimating species divergence. Nat. Educ. 2008, 1, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Granados, R.R. An intestinal mucin is the target substrate for a baculovirus enhancin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 6977–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, R.O.; Cardoso, C.; Pimentel, A.C.; Damasceno, T.F.; Ferreira, C.; Terra, W.R. The roles of mucus-forming mucins, peritrophins and peritrophins with mucin domains in the insect midgut. Insect Mol. Biol. 2018, 27, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachat, S.R.; Goldstein, P.Z.; Desalle, R.; Bobo, D.M.; Boyce, K.; Payne, J.L.; Labandeira, C.C. Illusion of flight? Absence, evidence and the age of winged insects. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2023, 138, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, D.; Löfstedt, C.; Picimbon, J.-F. Molecular characterization and evolution of pheromone binding protein genes in Agrotis moths. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 35, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, L.; Lako, M.; van Herpe, I.; Evans, J.; Saretzki, G.; Hole, N. A role for nucleotide Zap3 in the reduction of telomerase activity during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mech. Dev. 2004, 121, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teparic, R.; Lozancic, M.; Mrsa, V. Evolutionary overview of molecular interactions and enzymatic activities in the yeast cell walls. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, D.W.J.; Read, A.M.; Stephens, F.H.S.; Civetta, A.; Soller, M. Indel driven rapid evolution of core nuclear pore protein gene promoters. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrasse, J.A.; DuBois, K.N.; Devos, D.; Siegel, T.N.; Sali, A.; Field, M.C.; Rout, M.P.; Chait, B.T. Evidence for a shared nuclear pore complex architecture that is conserved from the Last Common Eukaryotic Ancestor. Mol. Cell. Prot. 2009, 8, 2119–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Oliveira, T.; Wollweber, F.; Ponce-Toledo, R.I.; Xu, J.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R.; Klingl, A.; Pilhofer, M.; Schleper, C. Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaeon. Nature 2023, 613, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R.; Schwede, T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nuc. Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, H.-Y.H.; Rohatgi, R.; Ma, L.; Kirschner, M.W. CR16 forms a complex with N-WASP in brain and is a novel member of a conserved proline-rich actin-binding protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11306–11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chereau, D.; Kerff, F.; Graceffa, P.; Grabarek, Z.; Langsetmo, K.; Dominguez, R. Actin-bound structures of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-homology domain 2 and the implications for filament assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16644–1644449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, S.; Letellier, J.; Lippé, R. Herpes simplex virus type 1 capsids transit by the trans-Golgi network, where viral glycoproteins accumulate independently of capsid egress. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 8847–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerio, A.P.; Anibal, F.F. Role of leukotrienes on protozoan and helminth infections. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 595694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.C.; Nam, K.; Kim, J.; Stanley, D.; Kim, Y. Thromboxane mobilizes insect blood cells to infection foci. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 791319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.; Kim, Y. Chapter Eight – Insect prostaglandins and other eicosanoids: from molecular to physiological actions. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2019, 56, 283–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, H.M.; Maitra, N.; Polymenis, M. Lipid biosynthesis: When the cell cycle meets protein synthesis? Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 905–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, H.M.; Perez, R.; He, C.; Maitra, N.; Metz, R.; Hill, J.; Lin, Y.; Johnson, C.D.; Bankaitis, V.A.; Kennedy, B.K.; Aramayo, R.; Polymenis, M. Translational control of lipogenic enzymes in the cell cycle of synchronous, growing yeast cells. EMBO Journal 2017, 36, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999, 44, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Wada, K.; Kabuta, T. Lysosomal degradation of intracellular nucleic acids—multiple autophagic pathways. J. Biochem. 2017, 161, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, N.; Fónagy, A.; Tatsuki, S.; Arie, T.; Yamashita, S.; Matsumoto, S. Ultrastructural studies on the pheromone-producing cells in the silkmoth, Bombyx mori: formation of cytoplasmic lipid droplets before adult eclosion. Acta Biol. Hung. 2003, 54, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.; Fonagy, A. Molecular basis of pheromonogenesis regulation in moths. In Olfactory Concepts of Insect Control-Alternative to Insecticides; Picimbon, J.F., Ed; Vol. 1, Springer Nature AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 115-202. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, A.; Hetzer, M.W. Nuclear pore proteins and the control of genome functions. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.H.; Hoelz, A. The structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex (an update). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 725–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenis, S.; Istiban, M.N.; Van Damme, S.; Vandewyer, E.; Watteyne, J.; Schoofs, L.; Beets, I. Ancestral glycoprotein hormone-receptor pathway controls growth in C. elegans. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1200407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornblihtt, A.R.; de la Mata, M.; Fededa, J.P.; Muñoz, M.J.; Nogués, G. Multiple links between transcription and splicing. RNA 2004, 10, 1489–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescauld, F.; Song, Y.; Dautant, A. Structure, folding and stability of nucleoside diphosphate kinases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangguan, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Rao, W.; Jing, S.; Guan, W.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, R.; Du, B.; Zhu, L.; Yu, D.; He, G. A mucin-like protein of planthopper is required for feeding and induces immunity responses in plants. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Rong, Y.S. JiangShi (僵尸): a widely distributed Mucin-like protein essential for Drosophila development. G3 (Bethesda) 2022, 12, jkac126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaeva, D.N.; Galperin, M.Y.; Mulkidjanian, A.Y. Eukaryotic G protein-coupled receptors as descendants of prokaryotic sodium-translocating rhodopsins. Biol. Direct 2015, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, P.; Ternes, P.; Zank, T.K.; Heinz, E. The evolution of desaturases. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2003, 68, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, D.A.; Murata, N. Chapter 10 – Sensing and responses to low temperature in cyanobacteria. In Cell and Molecular Responses to Stress; Storey, K.B., Storey, J.M., Eds; Vol. 3, Elsevier, ScienceDirect, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2002; pp. 139-153.

- Rock, C.O. Chapter 3 – Fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism in prokaryotes. In Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes Fifth Edition; Vance, D.E., Vance, J.E., Eds; Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008; pp. 59-96. [CrossRef]

- Njenga, R.; Boele, J.; Öztürk, Y.; Koch, H.G. Coping with stress: How bacteria fine-tune protein synthesis and protein transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moto, K.; Suzuki, M.G.; Hull, J.J.; Kurata, R.; Takahashi, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Okano, K.; Imai, K.; Ando, T.; Matsumoto, S. Involvement of a bifunctional fatty-acyl desaturase in the biosynthesis of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori, sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8631–8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damude, H.G.; Zhang, H.; Farrall, L.; Ripp, K.G.; Tomb, J.F.; Hollerbach, D.; Yadav, N.S. Identification of bifunctional delta12/omega3 fatty acid desaturases for improving the ratio of omega3 to omega6 fatty acids in microbes and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9446–9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-García, A.; Monera-Girona, A.J.; Pajares-Martínez, E.; Bastida-Martínez, E.; Pérez-Castaño, R.; Iniesta, A.A.; Fontes, M.; Padmanabhan, S.; Elías-Arnanz, M. A bacterial light response reveals an orphan desaturase for human plasmalogen synthesis. Science 2019, 366, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siroli, L.; Braschi, G.; Rossi, S.; Gottardi, D.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R. Lactobacillus paracasei A13 and high-pressure homogenization stress response. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffers, D.J.; Pinho, M.G. Bacterial cell wall synthesis: new insights from localization studies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005, 69, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, A.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Qiao, L.; Wang, W.W. Enhanced cell wall and cell membrane activity promotes heat adaptation of Enterococcus faecium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, A.; Honma, K.; Sharma, A.; Kuramitsu, H.K. Multiple functions of the leucine-rich repeat protein LrrA of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 4619–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, H.; Hui, X.; Cheng, X.; White, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y. Distribution and evolution of Yersinia Leucine-Rich Repeat proteins. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, D.; Busby, S. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M.P.; Hekmat-Scafe, D.S.; Gaines, P.; Carlson, J.R. Putative Drosophila pheromone-binding-proteins expressed in a subregion of the olfactory system. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16340–16347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikielny, C.W.; Hasan, G.; Rouyer, F.; Rosbach, M. Members of a family of Drosophila putative odorant-binding proteins are expressed in different subsets of olfactory hairs. Neuron 1994, 12, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, H.M.; Martos, R.; Sears, C.R.; Todres, E.Z.; Walden, K.K.; Nardi, J.B. Diversity of odourant binding proteins revealed by an expressed sequence tag project on male Manduca sexta moth antennae. Insect Mol. Biol. 1999, 8, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingham, V.A.; Anthousi, A.; Douris, V.; Harding, N.J.; Lycett, G.; Morris, M.; Vontas, J.; Ranson, H. A sensory appendage protein protects malaria vectors from pyrethroids. Nature 2020, 577, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picimbon, J.F.; Regnault-Roger, C. Composés sémiochimiques volatils, phytoprotection et olfaction: cibles moléculaires de la lutte intégrée. In Biopesticides d’Origine Végétale; Regnault-Roger, C., Philogène, B., Vincent, C., Eds; Lavoisier Tech & Doc, Paris, France, 2008; pp. 383-415.

- Diez-Hermano, S.; Ganfornina, M.D.; Skerra, A.; Guttiérez, G.; Sanchez, D. An evolutionary perspective of the lipocalin protein family. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moelling, K.; Broecker, F. Viruses and Evolution – Viruses First? A Personal Perspective. Front. Microbiol., Sec. Virol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrecht, R.A. What can we learn from localizing lipoclistins? European Symposium For Insect Taste and Olfaction (ESITO VIII) 2003, July 2-7th, Harstad, Norway.

- Steinbrecht, R.A. Fine structure immunocytochemistry—An important tool for research on odorant-binding proteins. Meth. Enzymol. 2020, 642, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W. The exon theory of genes. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1987, 52, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.W. Recent evidence for the exon theory of genes. Genetica 2003, 118, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Imai, K.; Matsumoto, S. Functional characterization of the Bombyx mori fatty acid transport protein (BmFATP) within the silkmoth pheromone gland. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5128–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiRusso, C.C.; Black, P.N. Bacterial long chain fatty acid transport: gateway to a fatty acid-responsive signaling system. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49563–49566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Organism | Authors | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p10 | Periplaneta americana | Nomura et al. | 1992 | [71] |

| Ebsp-3/PebIII | Drosophila melanogaster | Dyanov et al. | 1994 | AAA87058* |

| A10 | Drosophila melanogaster | Pikielny et al. | 1994 | [134] |

| OS-D | Drosophila melanogaster | McKenna et al. | 1994 | [133] |

| Pam | Periplaneta americana | Picimbon & Leal | 1999 | [4] |

| CSP | Schistocerca gregaria | Angeli et al. | 1999 | [5] |

| SAP | Manduca sexta | Robertson et al. | 1999 | [135] |

| Pherokine | Drosophila melanogaster | Sabatier et al. | 2003 | [27] |

| Mp10 | Myzus persicae | Bos et al. | 2010 | [45] |

| LA-BP | Bemisia tabaci | Liu et al. | 2016 | [30] |

| Toxin-BP | Bemisia tabaci | Liu et al. | 2016 | [30] |

| B-CSP | Acinetobacter baumannii | Liu et al. | 2019 | [38] |

| Lipid-BP | Bemisia tabaci | Liu et al. | 2020 | [31] |

| JHRP | Aedes aegypti | Picimbon | 2020 | [20] |

| Mucin module | Aedes aegypti | Liu et al. | 2024 | This paper |

| TIF module | Aedes aegypti | Liu et al. | 2024 | This paper |

| DNA/RNA-BP | Aedes aegypti | Liu et al. | 2024 | This paper |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).