Submitted:

28 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

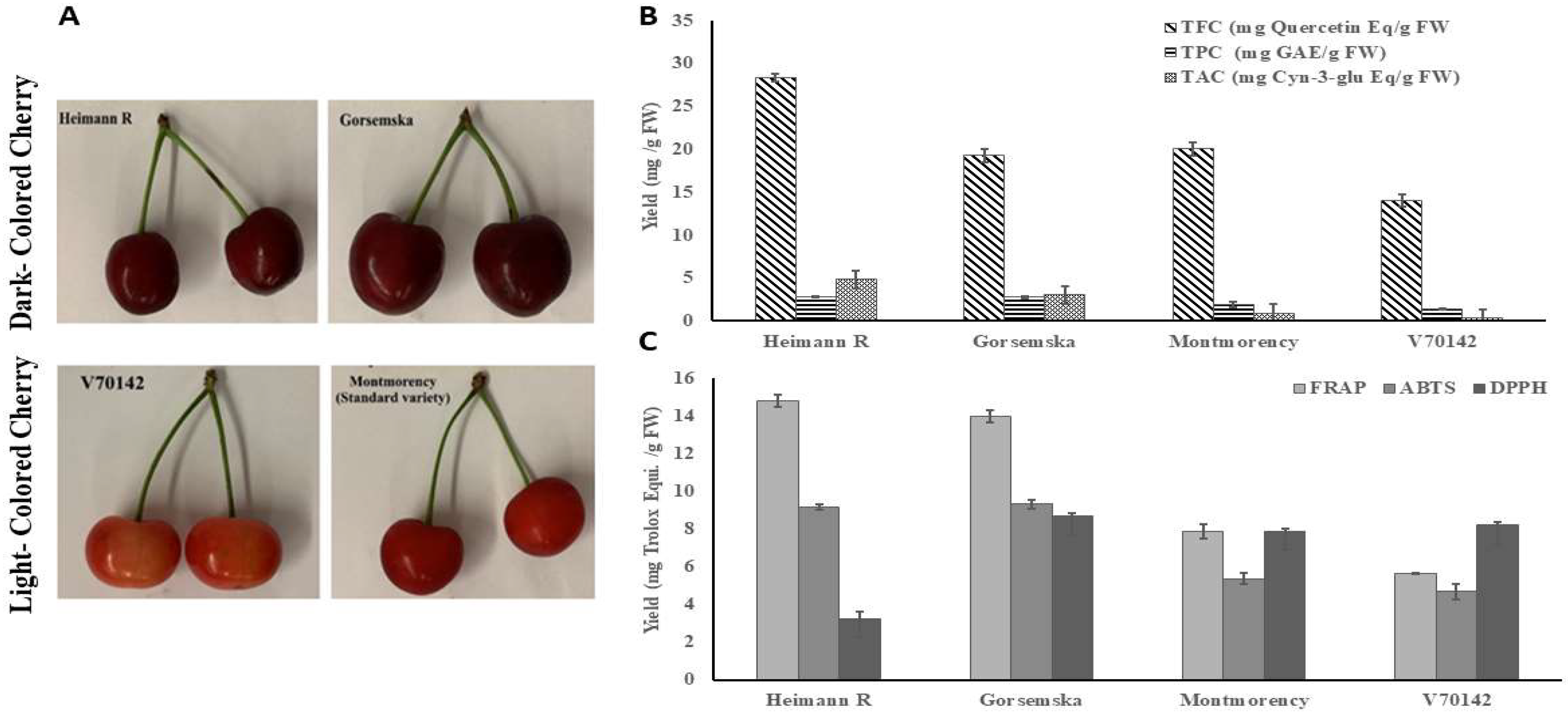

2.1. Quantification of total phenolic, flavonoid, anthocyanin and antioxidant content

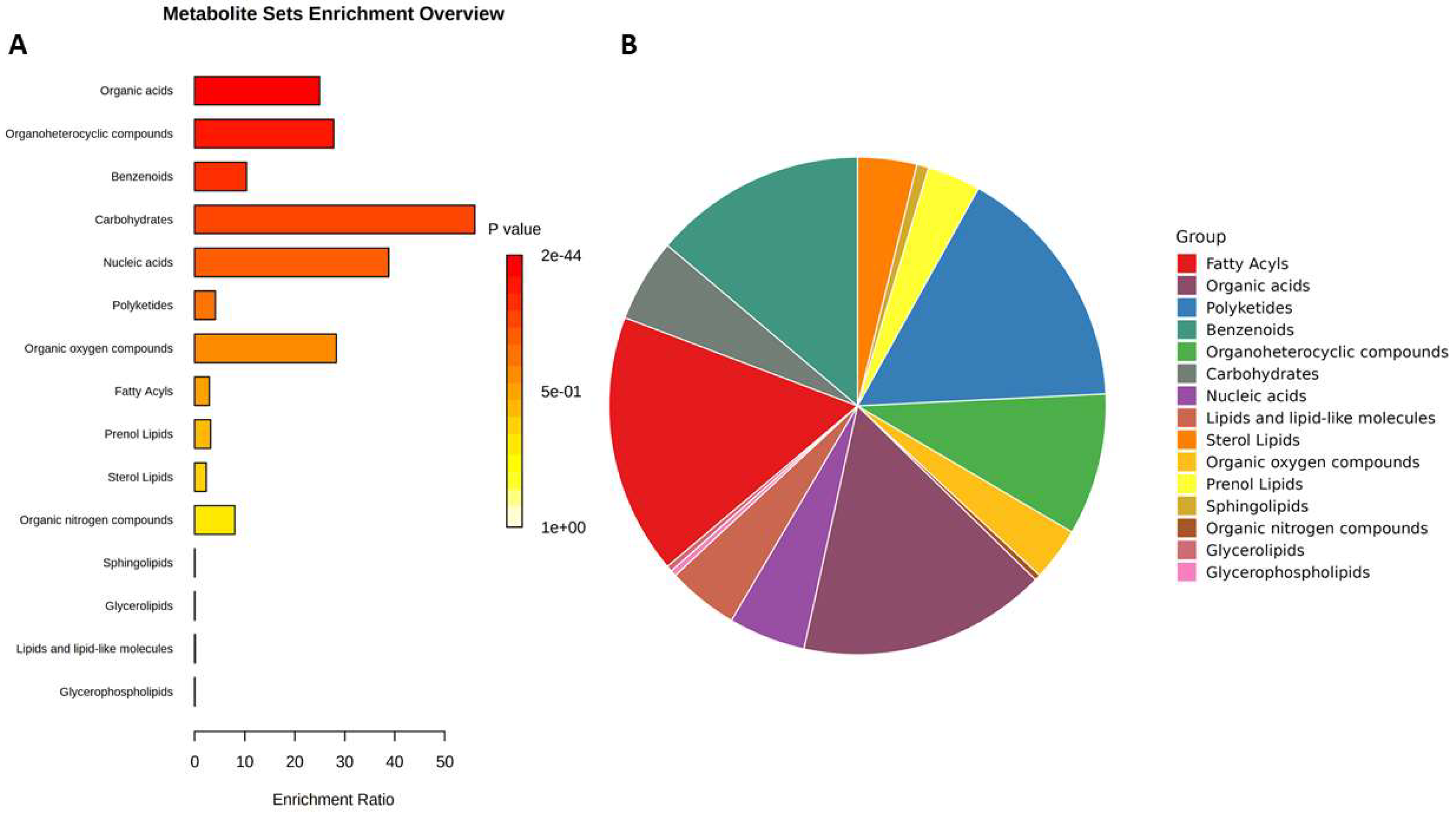

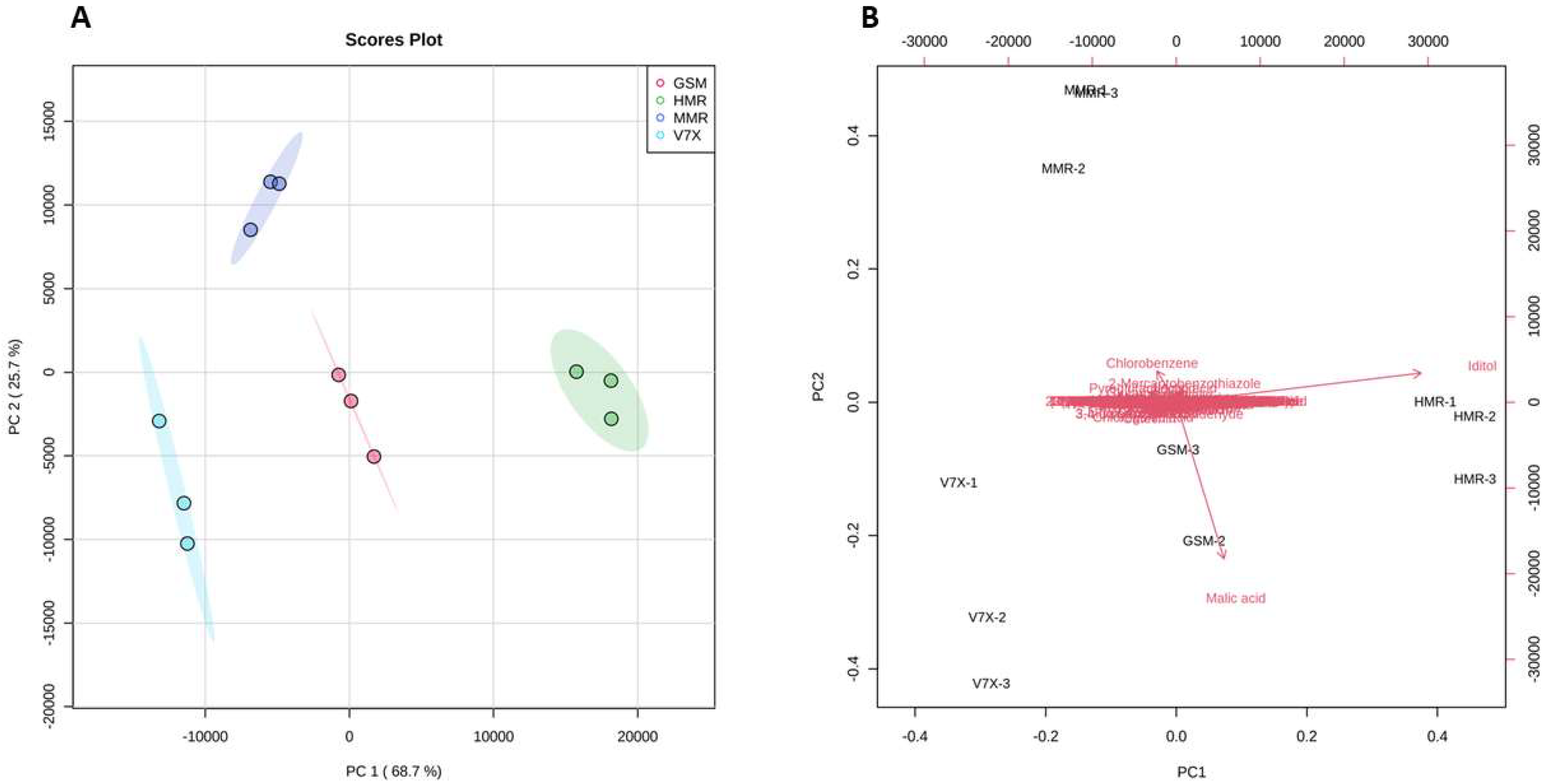

2.2. Untargeted metabolic profiling of selected sour cherry cultivars

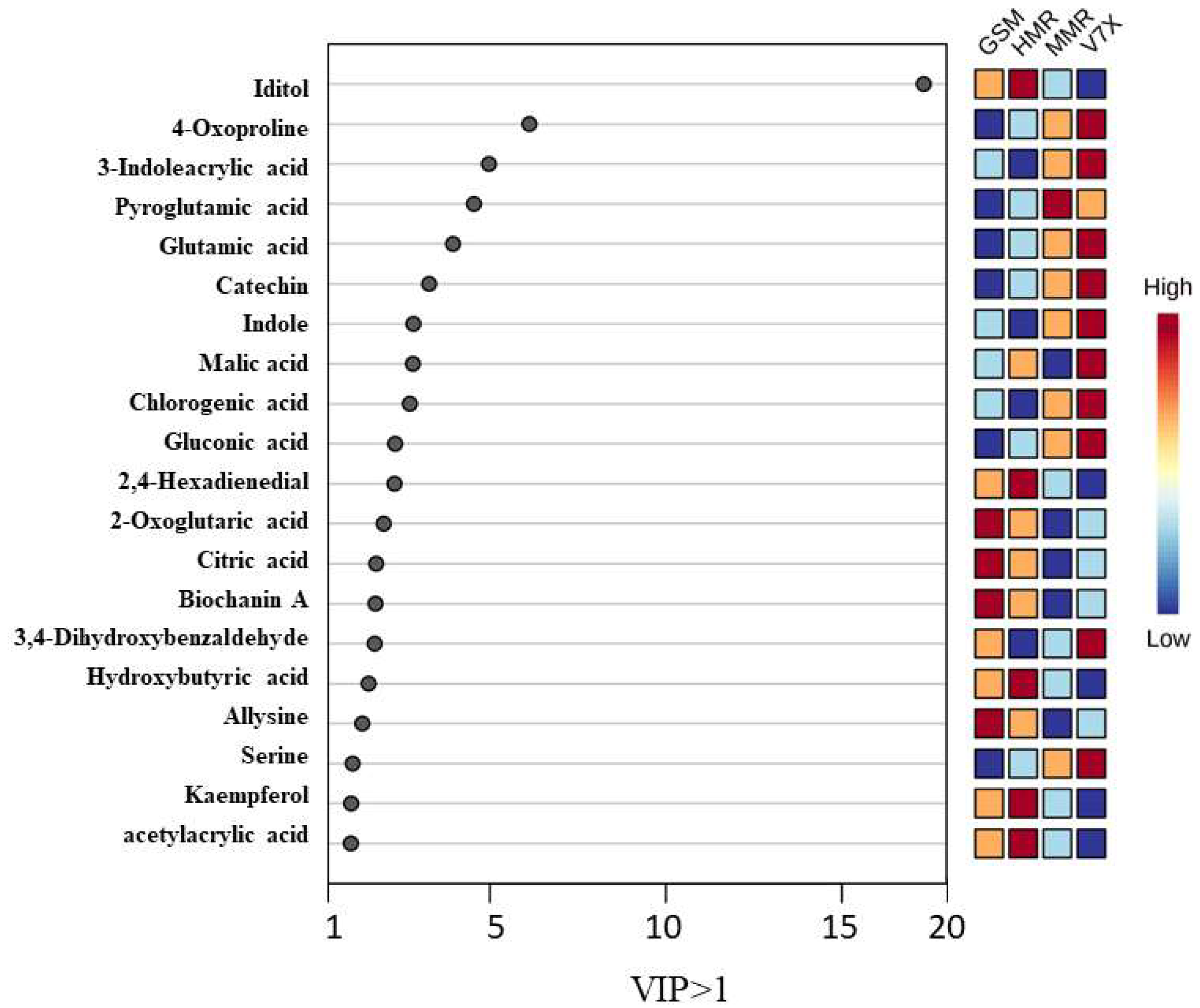

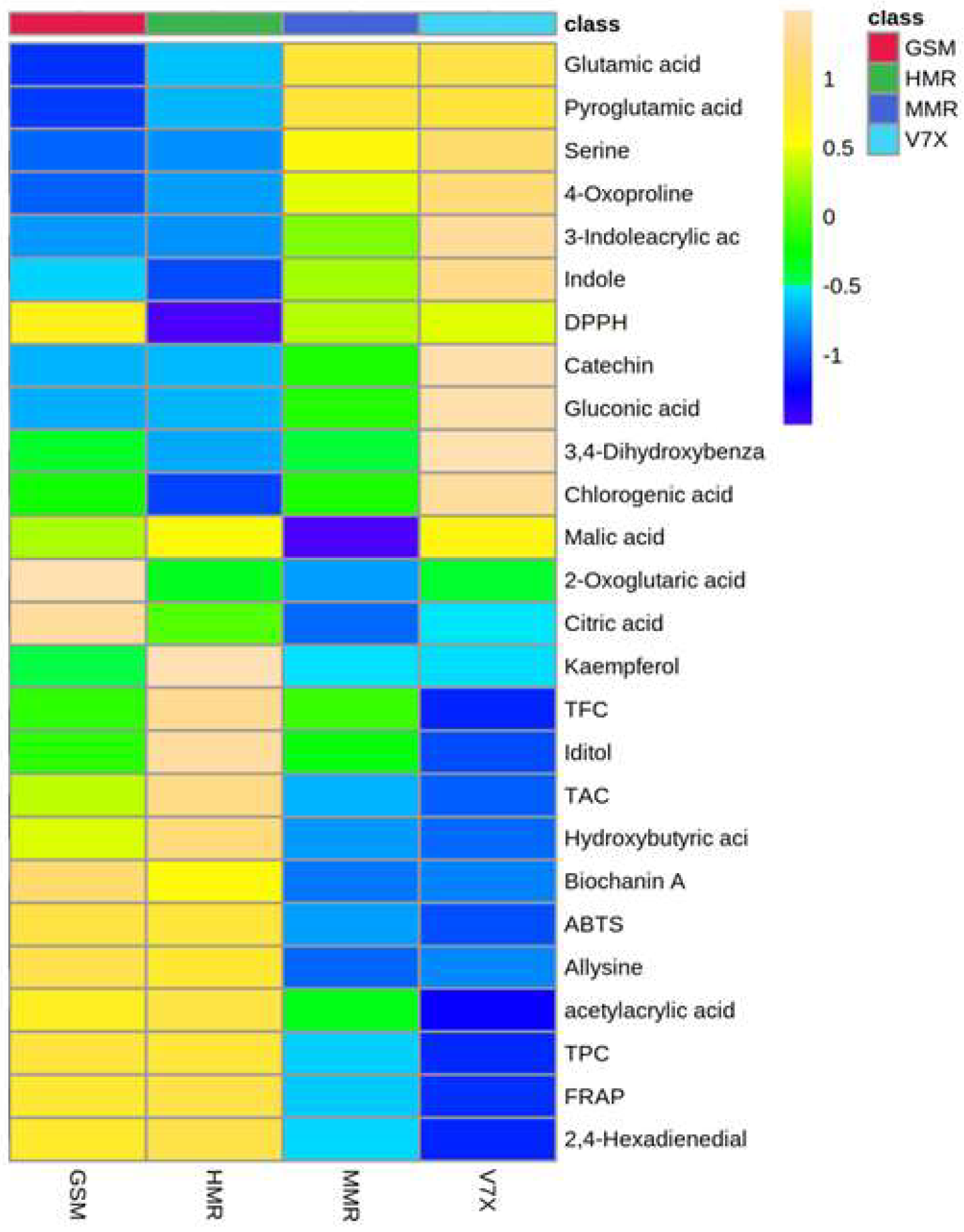

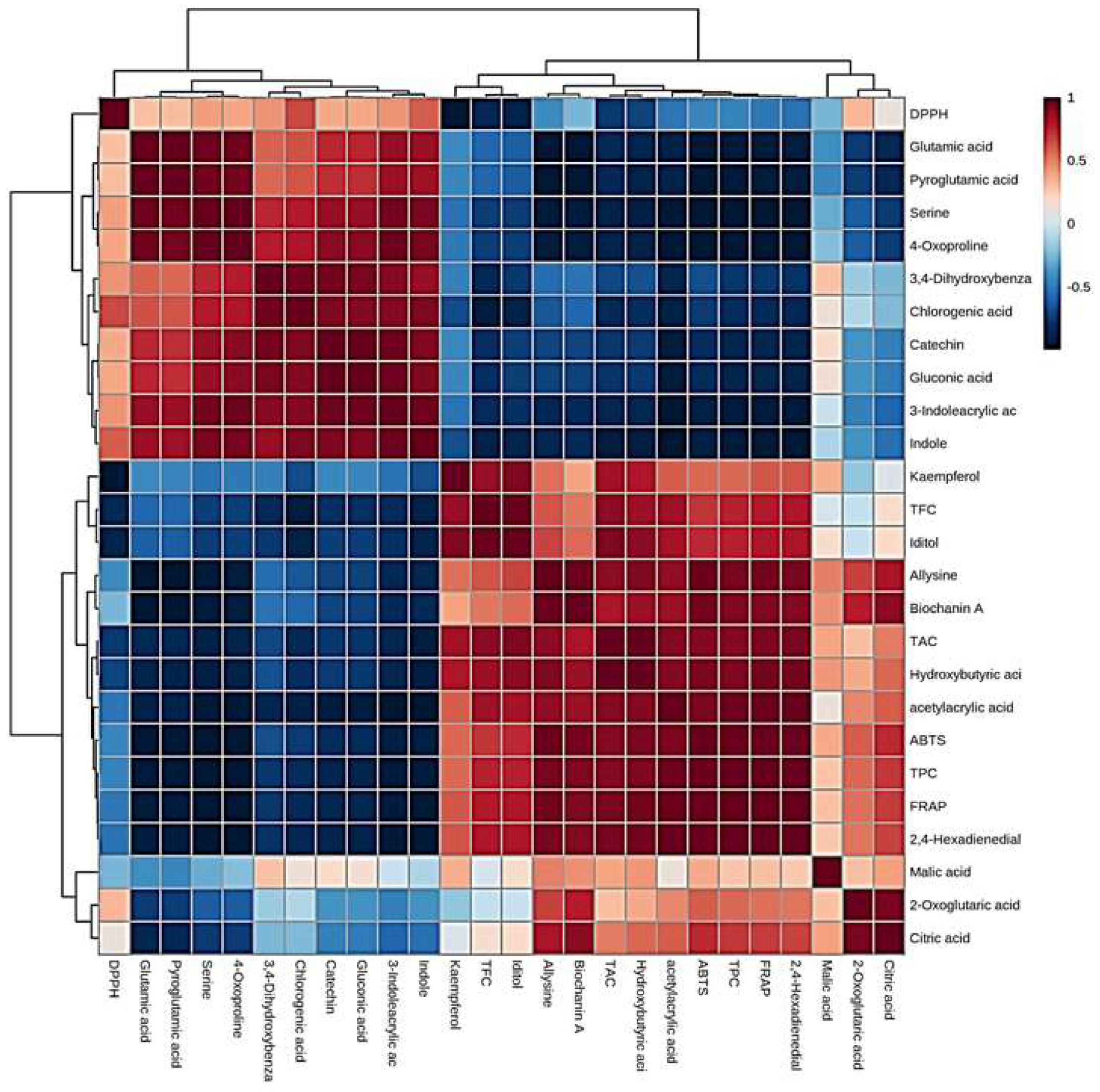

2.3. Biomarker metabolites and their correlation with bioactive components

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cherry samples

3.2. Preparation of cherry extract

3.3. Estimation of Total phenolic, flavonoid, anthocyanin and antioxidants

3.4. Untargeted metabolomics using UPLC-MS.

3.4.1. Metabolite extraction

3.4.2. Metabolomic analysis conditions

3.4.3. Data processing

3.4.4. Metabolites identification

3.4.5. Statistical analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nawirska-Olszańska, A.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Oziembłowski, M.; Ticha, A.; Hyšpler, R.; Zadak, Z.; Židová, P.; Paprstein, F. Comparison of Old Cherry Cultivars Grown in Czech Republic by Chemical Composition and Bioactive Compounds. Food Chem 2017, 228, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Li, R.; Ren, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ma, D.; Luo, Y. A Comparative Metabolomics Study of Flavonoids in Sweet Potato with Different Flesh Colors (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam). Food Chem 2018, 260, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehl, K.S. Cherry Juice Targets Antioxidant Potential and Pain Relief. Acute Topics in Sport Nutrition 2012, 59, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiki, Z.; Papp-Bata, A.; Czompa, A.; Nagy, A.; Bak, I.; Lekli, I.; Javor, A.; Haines, D.D.; Balla, G.; Tosaki, A. Orally Delivered Sour Cherry Seed Extract (SCSE) Affects Cardiovascular and Hematological Parameters in Humans. Phytotherapy Research 2015, 29, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, F.; Haines, D.; Al-Awadhi, R.; Dashti, A.A.; Al-Awadhi, A.; Ibrahim, B.; Al-Zayer, B.; Juhasz, B.; Tosaki, A. Sour Cherry (Prunus Cerasus) Seed Extract Increases Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression and Decreases Proinflammatory Signaling in Peripheral Blood Human Leukocytes from Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2014, 20, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Bosak, K.N.; Brickner, P.R.; Iezzoni, D.G.; Seymour, E.M. Processed Tart Cherry Products—Comparative Phytochemical Content, in Vitro Antioxidant Capacity and in Vitro Anti-inflammatory Activity. J Food Sci 2012, 77, H105–H112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acero, N.; Gradillas, A.; Beltran, M.; García, A.; Muñoz Mingarro, D. Comparison of Phenolic Compounds Profile and Antioxidant Properties of Different Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Varieties. Food Chem 2019, 279, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.T.; Duarte, R.O.; Bronze, M.R.; Duarte, C.M.M. Identification of Bioactive Response in Traditional Cherries from Portugal. Food Chem 2011, 125, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, P.; Martini, C.; Bulzomi, P.; Leone, S.; Bolli, A.; Pallottini, V.; Marino, M. Quercetin-induced Apoptotic Cascade in Cancer Cells: Antioxidant versus Estrogen Receptor A-dependent Mechanisms. Mol Nutr Food Res 2009, 53, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Hu, H.; Ann Cuin, T.; Hao, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, C. Untargeted Metabolomics and Comparative Flavonoid Analysis Reveal the Nutritional Aspects of Pak Choi. Food Chem 2022, 383, 132375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT_data_5-26-2020.

- Kappel, S.J.F.; Jayasankar, S.; Kappel, F. Recent Advances in Cherry Breeding. Fruit, vegetables and cereal sciences and biotechnology. Global Science Book 2011, 63–67.

- Jayasankar, S.; Kappel, F. Recent Advances in Cherry Breeding. Fruit, vegetables and cereal sciences and biotechnology. Global Science Book 2011, 63–67.

- Radičević, S.; Cerović, R.; Lukić, M.; Paunović, S.A.; Jevremović, D.; Milenković, S.; Mitrović, M. Selection of Autochthonous Sour Cherry (Prunus Cerasus L.) Genotypes in Feketić Region. Genetika 2012, 44, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Mu, X.; Du, J.; Gary, Y.; Donghai, G. Flavonoid Content and Radical Scavenging Activity in Fruits of Chinese Dwarf Cherry ( Cerasus Humilis ) Genotypes. J For Res (Harbin) 2018, 29, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Morden, K.; Subramanian, J.; Singh, A. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Characteristics, Bioactive Components, and Volatile Profile of Sour Cherry ( Prunus Cerasus ). Canadian Journal of Plant Science 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokół-Łe̜towska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Hodun, G.; Gołba, M. Chemical Composition of 21 Cultivars of Sour Cherry (Prunus Cerasus) Fruit Cultivated in Poland. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.R.; Darwish, A.G.; Ismail, A.; Haikal, A.M.; Gajjar, P.; Balasubramani, S.P.; Sheikh, M.B.; Tsolova, V.; Soliman, K.F.A.; Sherif, S.M.; et al. Diversity in Blueberry Genotypes and Developmental Stages Enables Discrepancy in the Bioactive Compounds, Metabolites, and Cytotoxicity. Food Chem 2022, 374, 131632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.; Rahr, M.; Hjelmsted, B.; Larsen, E.; Khoo, G.M.; Clausen, M.R.; Pedersen, B.H.; Larsen, E. Bioactivity and Total Phenolic Content of 34 Sour Cherry Cultivars. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011, 24, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Laskowski, P.; Oszmiański, J. Evaluation of Sour Cherry (Prunus Cerasus L.) Fruits for Their Polyphenol Content, Antioxidant Properties, and Nutritional Components. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 12332–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavoura, M. V.; Badeka, A. V.; Kontakos, S.; Kontominas, M.G. Characterization of Four Popular Sweet Cherry Cultivars Grown in Greece by Volatile Compound and Physicochemical Data Analysis and Sensory Evaluation. Molecules 2015, 20, 1922–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toydemir, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Gomez Roldan, M.V.; De Vos, R.C.H.; Boyacioglu, D.; Hall, R.D.; Beekwilder, J. Industrial Processing Effects on Phenolic Compounds in Sour Cherry (Prunus Cerasus L.) Fruit. Food Research International 2013, 53, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serradilla, M.J.; Hernández, A.; López-Corrales, M.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; de Guía Córdoba, M.; Martín, A. Composition of the Cherry (Prunus Avium L. and Prunus Cerasus L.; Rosaceae), In Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars, Elsevier Inc., 2015; ISBN 9780124081178.

- Mousavi, M.; Zaiter, A.; Modarressi, A.; Baudelaire, E.; Dicko, A. The Positive Impact of a New Parting Process on Antioxidant Activity, Malic Acid and Phenolic Content of Prunus Avium L., Prunus Persica L. and Prunus Domestica Subsp. Insititia L. Powders. Microchemical Journal 2019, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Scalzo, R. Organic Acids Influence on DPPH{radical Dot} Scavenging by Ascorbic Acid. Food Chem 2008, 107, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, L.; Bi, F.; Xiang, X. Combined Application of Malic Acid and Lycopene Maintains Content of Phenols, Antioxidant Activity, and Membrane Integrity to Delay the Pericarp Browning of Litchi Fruit During Storage. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; He, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Comparative Metabolomics Profiling Highlights Unique Color Variation and Bitter Taste Formation of Chinese Cherry Fruits. Food Chem 2024, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopjar, M.; Orsolic, M.; Pilizota, V. Anthocyanins, Phenols, and Antioxidant Activity of Sour Cherry Puree Extracts and Their Stability during Storage. Int J Food Prop 2014, 17, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballistreri, G.; Continella, A.; Gentile, A.; Amenta, M.; Fabroni, S.; Rapisarda, P. Fruit Quality and Bioactive Compounds Relevant to Human Health of Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Cultivars Grown in Italy. Food Chem 2013, 140, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.; Rahr, M.; Hjelmsted, B.; Larsen, E. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis Bioactivity and Total Phenolic Content of 34 Sour Cherry Cultivars. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011, 24, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatoniene, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M. The Role of Catechins in Cellular Responses to Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Fang, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Hu, B.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Wang, T.; et al. Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomic Analyses and Biological Activity of Tibetan Tea. Food Chem 2022, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.J.; Lai, W.F. Chemical and Biological Properties of Biochanin A and Its Pharmaceutical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majrashi, M.; Altukri, M.; Ramesh, S.; Govindarajulu, M.; Schwartz, J.; Almaghrabi, M.; Smith, F.; Thomas, T.; Suppiramaniam, V.; Moore, T.; et al. β-Hydroxybutyric Acid Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Improves Markers of Mitochondrial Function in the HT-22 Hippocampal Cell Line. J Integr Neurosci 2021, 20, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, S.; Nagarajan, R.; Kumar, J.; Salemme, A.; Togna, A.R.; Saso, L.; Bruno, F. Antioxidant Activity of Synthetic Polymers of Phenolic Compounds. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tang, G.Y.; Zhao, C.N.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H. Bin Antioxidant Activities, Phenolic Profiles, and Organic Acid Contents of Fruit Vinegars. Antioxidants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevão, M.S.; Carvalho, L.C.; Ribeiro, D.; Couto, D.; Freitas, M.; Gomes, A.; Ferreira, L.M.; Fernandes, E.; Marques, M.M.B. Antioxidant Activity of Unexplored Indole Derivatives: Synthesis and Screening. Eur J Med Chem 2010, 45, 4869–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Kitts, D.D. Role of Chlorogenic Acids in Controlling Oxidative and Inflammatory Stress Conditions. Nutrients 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H.S.; Pereira, G.A.; Pastore, G.M. Optimization of Extraction Parameters of Total Phenolics from Annona Crassiflora Mart. (Araticum) Fruits Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Anal Methods 2017, 10, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinović, A.; Cavoski, I. The Exploitation of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Cultivars and Genotypes from Montenegro as a Source of Natural Bioactive Compounds. Food Chem 2020, 318, 126549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Subramanian, J.; Singh, A. Green Extraction of Bioactive Components from Carrot Industry Waste and Evaluation of Spent Residue as an Energy Source. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).