Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

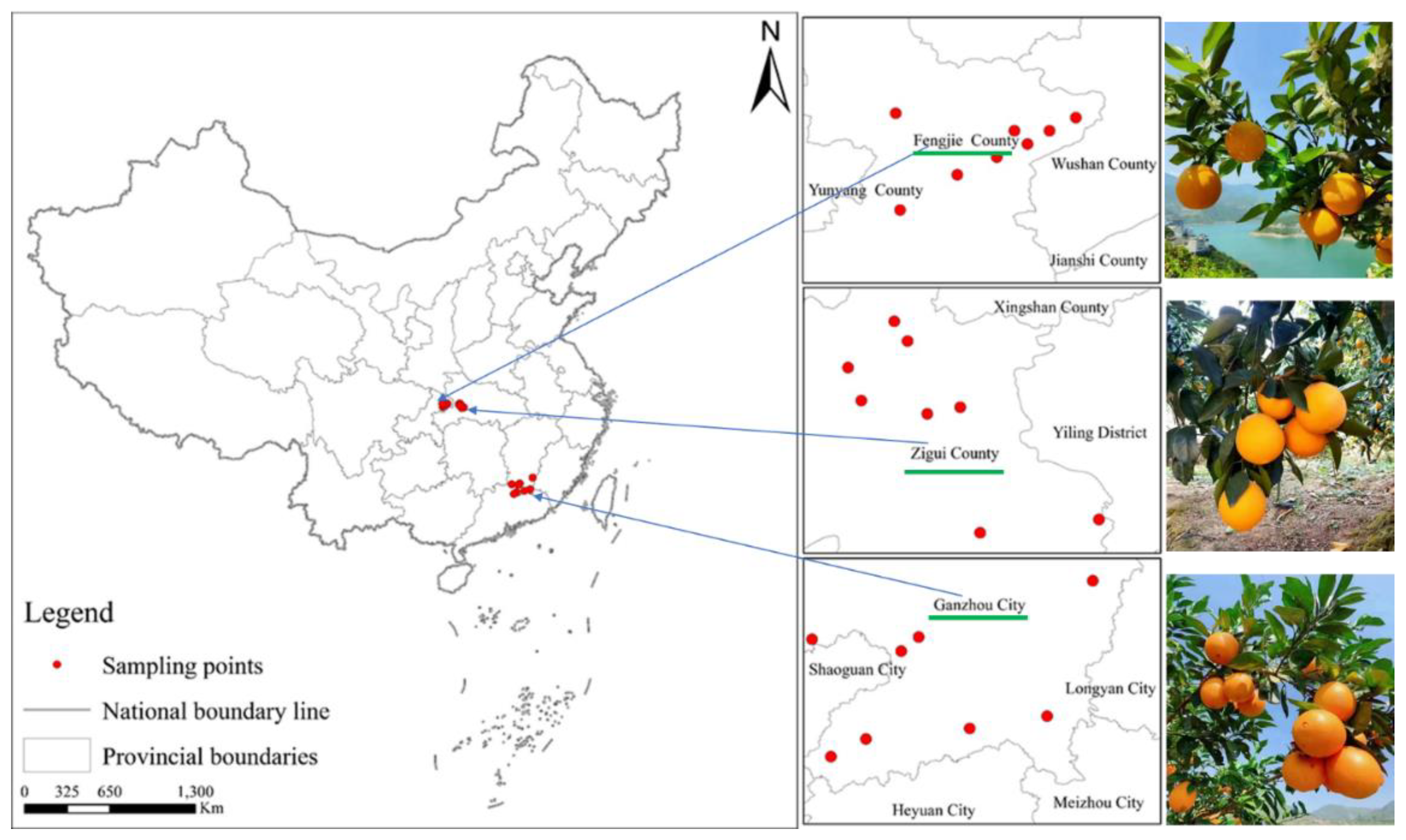

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Determination of Quality Attributes

2.3. Metabolomics Analysis

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

2.3.2. Metabolites Extraction

2.3.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.3.4. Data Processing

2.3.5. Metabolites Identification

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

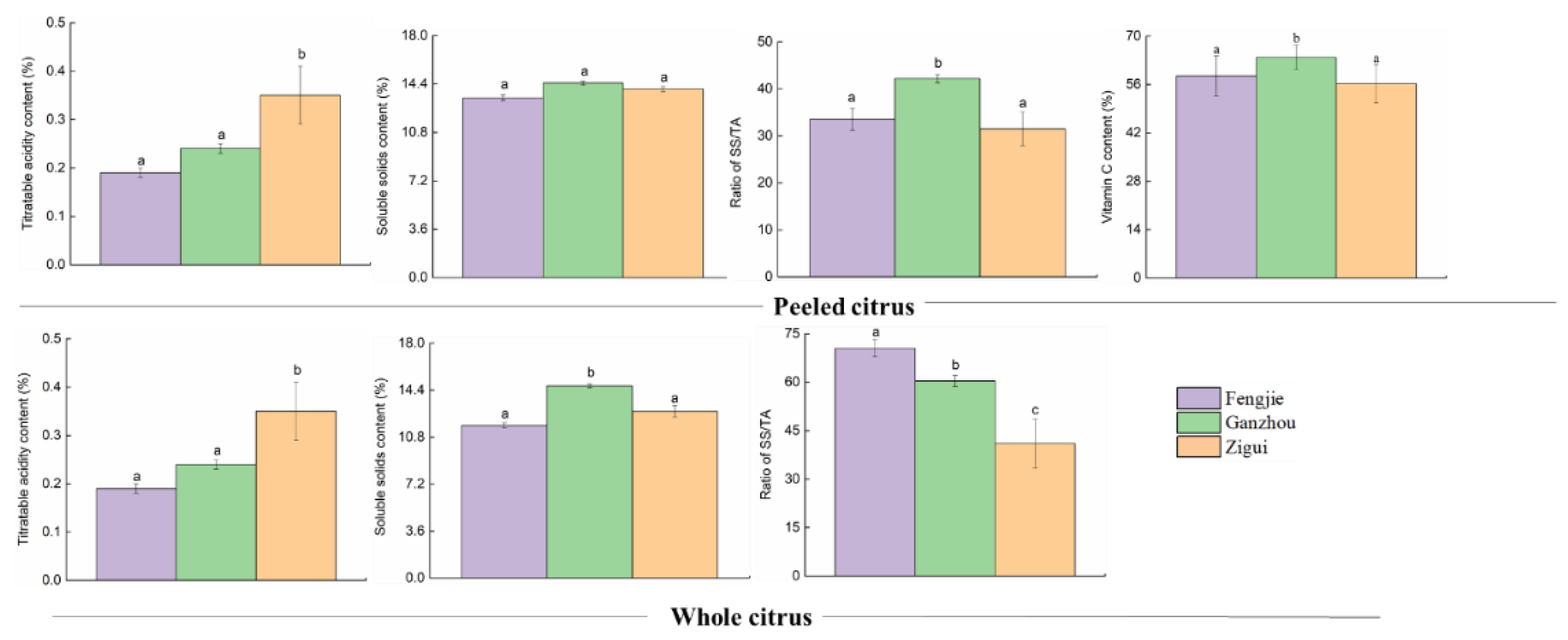

3.1. Quality Attributes

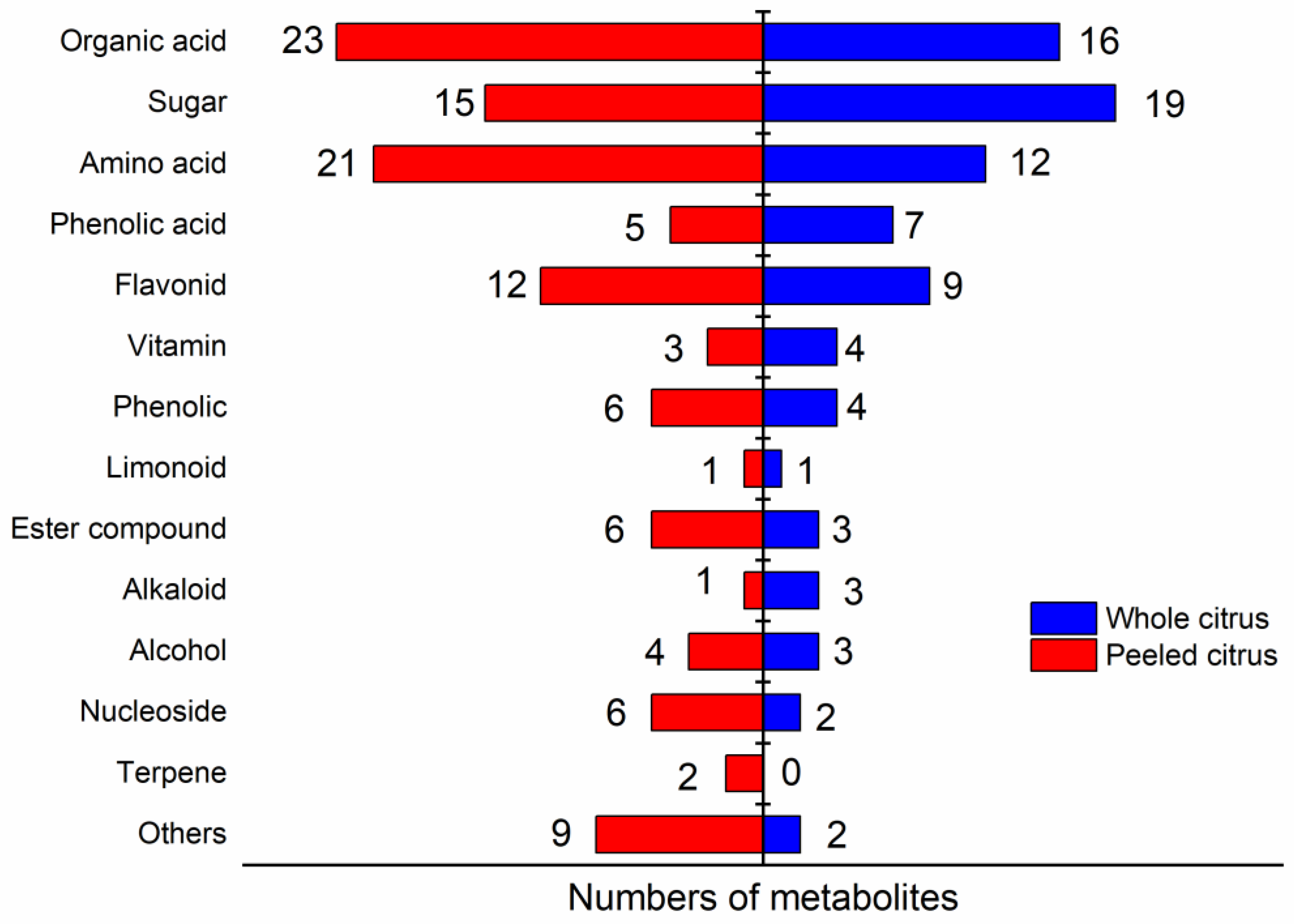

3.2. Compound Identification

3.3. Metabolic Markers Discrimination

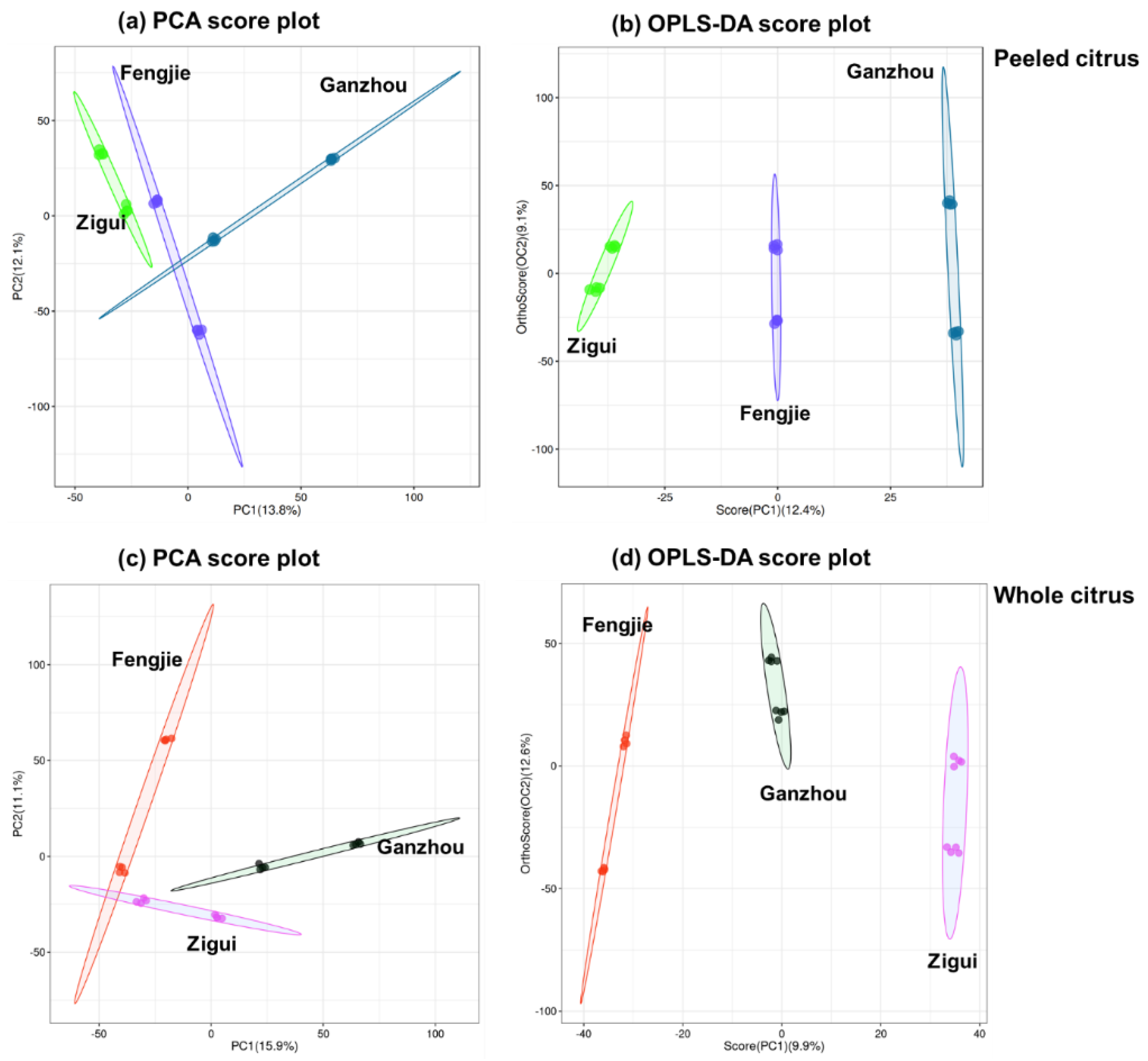

3.3.1. PCA and OPLS-DA Results

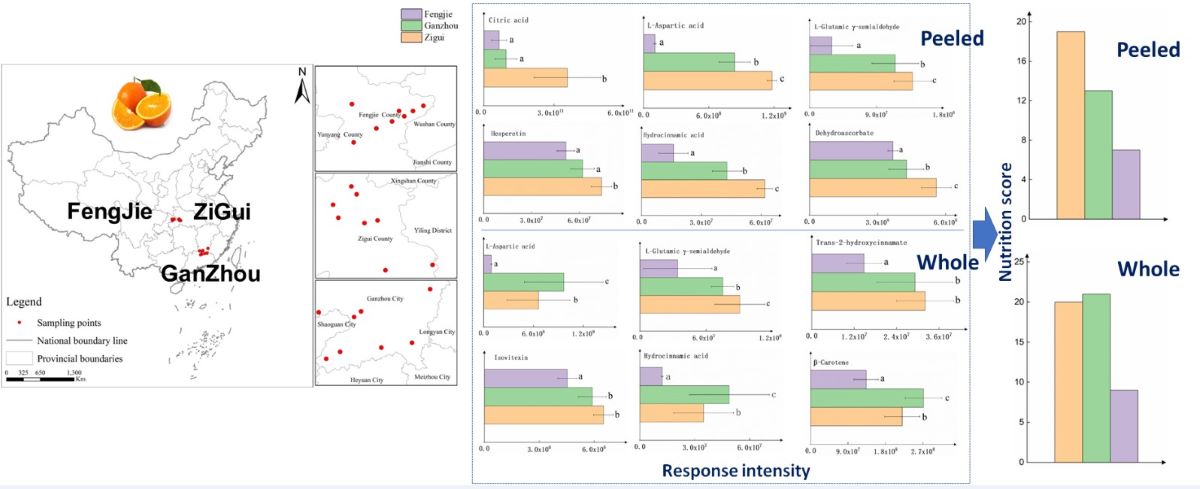

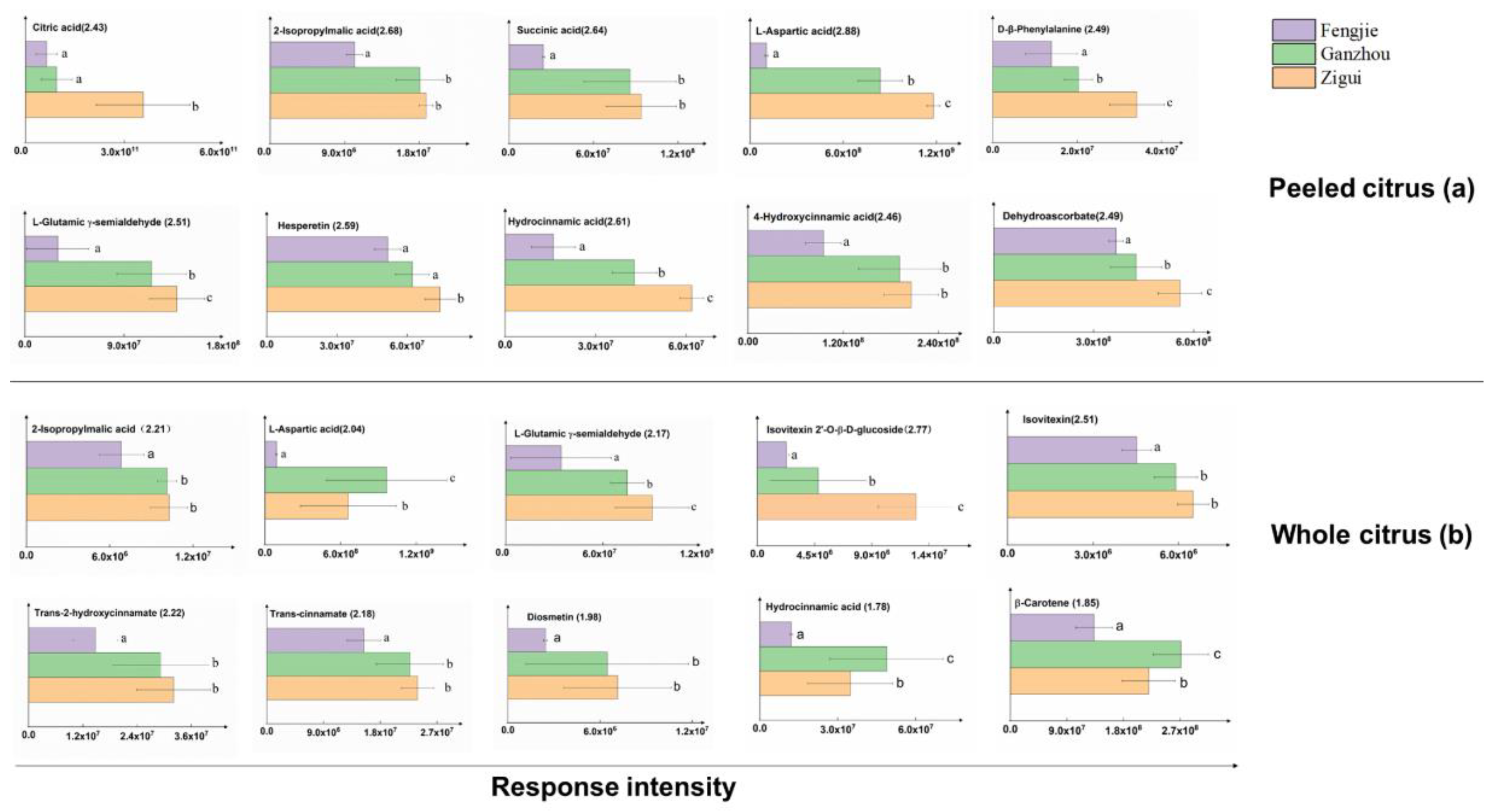

3.3.2. Top Ten Most Important Markers

3.4. Nutrition Evaluation

4. Discussion

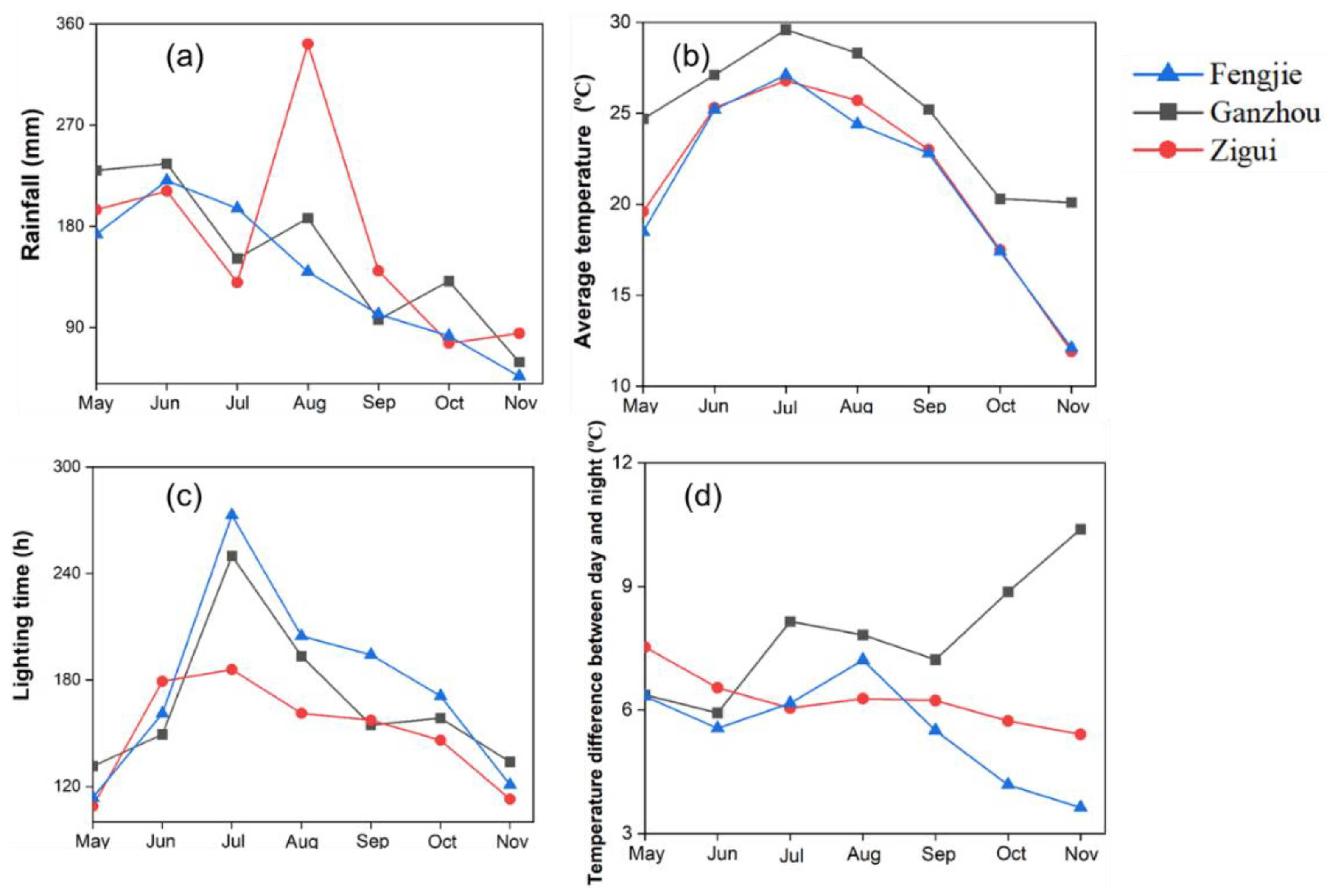

4.1. Quality Attributes

4.2. The Discrimination of GI Orange Samples and Top Ten Most Important Markers

4.3. Nutritional Comparison

4.4. The Potential Association between the Terroir and the Quality of Navel Orange

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, Y H; Liang, L; Xu, C H; Yang, T M; Wang, Y X. UPLC-Q-TOF/MS-based untargeted metabolomics for discrimination of navel oranges from different geographical origins of China. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 110382. [CrossRef]

- Ollitrault, P; Terol, J; Chen, C; Federici, C T; Lotfy, S; Hippolyte, I; Ollitrault, F; Berard, A; Chauveau, A; Cuenca, J; Costantino, G; Kacar, Y; Mu, L; Garcia-Lor, A; Froelicher, Y; Aleza, P; Boland, A; Billot, C; Navarro, L; Luro, F; Roose, M L; Gmitter, F G; Talon, M; Brunel, D. A reference genetic map of C. clementina hort. ex Tan.; citrus evolution inferences from comparative mapping. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 593.

- Lin, H; He, C; Liu, H; Shen, G; Xia, F; Feng, J. NMR-based quantitative component analysis and geographical origin identification of China's sweet orange. Food Control 2021, 130, 108292. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D Y; Liao, Q H; Xie R J; He, S L; Qian, C; Lv, Q; Yi, S L; Zheng, Y Q; Deng, L. Effect of geographical location on physical characteristics and chemical compositions of Newhall navel orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck). Food Sci. 2015, 36, 18–28.

- Sales, C; Cervera, M I; Gil, R; Portolés, T; Pitarch, E; Beltran, J. Quality classification of Spanish olive oils by untargeted gas chromatography coupled to hybrid quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization and metabolomics-based statistical approach. Food Chem. 2017, 216, 365–373.

- Ben Mohamed, M; Rocchetti, G; Montesano, D; Ben Ali, S; Guasmi, F; Grati-Kamoun, N; Lucini, L. Discrimination of Tunisian and Italian extra-virgin olive oils according to their phenolic and sterolic fingerprints. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senizza, B; Ganugi, P; Trevisan, M; Lucini, L. Combining untargeted profiling of phenolics and sterols, supervised multivariate class modelling and artificial neural networks for the origin and authenticity of extra-virgin olive oil: A case study on Taggiasca Ligure. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rituerto, E; Savorani, F; Avenoza, A; Busto, J H; Peregrina, J M; Engelsen, S B. Investigations of La Rioja terroir for wine production using 1H NMR metabolomics. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gougeon, L; Da Costa, G; Le Mao, I; Ma, W; Teissedre, P L; Guyon, F; Richard, T. Wine analysis and authenticity using 1H-NMR metabolomics data: Application to Chinese wines. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 3425–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y; Gu, H W; Lv, Y; Yin, X L; Chen, Y; Long, W J; Fu, H Y; She, Y B. Untargeted metabolomic analysis of Chinese red wines for geographical origin traceability by UPLC-QTOF-MS coupled with chemometrics. Food Chem. 2022, 394.

- Kasiotis, K M; Baira, E; Iosifidou, S; Manea-Karga, E; Tsipi, D; Gounari, S; Theologidis, I; Barmpouni, T; Danieli, P P; Lazzari, F; Dipasquale, D; Petrarca, S; Shairra, S; Ghazala, N A; Abd El-Wahed, A A; El-Gamal, S M A; Machera, K. Fingerprinting chemical markers in the mediterranean orange Blossom Honey: UHPLC-HRMS metabolomics study integrating melissopalynological analysis, GC-MS and HPLC-PDA-ESI/MS. Molecules 2023, 28, 3967.

- Li, Y; Jin, Y; Yang, S P; Zhang, W W; Zhang, J Z; Zhao, W; Chen, L Z; Wen, Y Q; Zhang, Y X; Lu, K Z; Zhang, Y P; Zhou, J H; Yang, S M. Strategy for comparative untargeted metabolomics reveals honey markers of different floral and geographic origins using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1499, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandric, Z; Frew, R D; Fernandez-Cedi, L N; Cannavan, A. An investigative study on discrimination of honey of various floral and geographical origins using UPLC-QToF MS and multivariate data analysis. Food Control 2017, 72, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J H. Critical review: Metabolomics in dairy science-Evaluation of milk and milk product quality. Food Res. Int. 2022, 154, 110984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassini, A; Curone, G; Solè, M; Capuani, G; Sciubba, F; Conta, G; Miccheli, A; Vigo, D. NMR-based metabolomics to evaluate the milk composition from Friesian and autochthonous cows of Northern Italy at different lactation times. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J H; Vinitchaikul, P; Gu, Z B; Mao, H M; Zhang, F L. The use of metabolomics to reveal differences in functional substances of milk whey of dairy buffaloes raised at different altitudes. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5440–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavropoulou, M I; Termentzi, A; Kasiotis, K M; Cheilari, A; Stathopoulou, K; Machera, K; Aligiannis, N. Untargeted ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS) metabolomics reveals propolis markers of Greek and Chinese origin. Molecules 2021, 26, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colantonio, V; Ferra, L F V; Tieman, D M; Bliznyuk, N; Sims, C; Klee, H J; Munoz, P; Resende, M F R. Metabolomic selection for enhanced fruit flavor. PNAS. 2022, 119, e2115865119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septembre-Malaterre, A; Remize, F; Poucheret, P. Fruits and vegetables, as a source of nutritional compounds and phytochemicals: Changes in bioactive compounds during lactic fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2018, 104, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X L; Wu, L X; Qiu, J; Qian, Y Z; Wang, M. Comparative metabolomic analysis of the nutritional aspects from ten cultivars of the strawberry fruit. Foods 2023, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X X; Gong, J P; Zhang, X M; Huang, Y C; Zhang, W; Yang, J Y; Lin, J J; Chai, Y; Liu, J F Evaluation of the combined toxicity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and cadmium on earthworms in soil using multi-level biomarkers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021; 221, 112441. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L; Wang, L; Xu, Z; Zhang, X; Zhang, Z; Qian, Y. Physicochemical quality and metabolomics comparison of the green food apple and conventional apple in China. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q; Yang, S; Li, B; Zhang, C; Li, Y; Li, J. Exploring critical metabolites of honey peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch) from five main cultivation regions in the north of China by UPLC-Q-TOF/MS combined with chemometrics and modeling. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y; He, J; Xu, Y; Zheng, W; Wang, S; Chen, P; Zeng, B; Yang, S; Jiang, X; Liu, Z; Wang, L; Wang, X; Liu, S; Lu, Z; Liu, Z; Yu, H; Yue, J; Gao, J; Zhou, X; Long, C; Zeng, X; Guo, Y-J; Zhang, W-F; Xie, Z; Li, C; Ma, Z; Jiao, W; Zhang, F; Larkin, R M; Krueger, R R; Smith, M W; Ming, R; Deng, X; Xu, Q. Pangenome analysis provides insight into the evolution of the orange subfamily and a key gene for citric acid accumulation in citrus fruits. Nature Genetics 2023, 55, 1964–1975.

- Katz, E; Boo Kh Fau - Kim, H Y; Kim Hy Fau - Eigenheer, R A; Eigenheer Ra Fau - Phinney, B S; Phinney Bs Fau - Shulaev, V; Shulaev V Fau - Negre-Zakharov, F; Negre-Zakharov F Fau - Sadka, A; Sadka A Fau - Blumwald, E; Blumwald, E. Label-free shotgun proteomics and metabolite analysis reveal a significant metabolic shift during citrus fruit development. J. Exp. Bot., 2011, 62, 5367–5384.

- Jayarajan, S.; Sharma, R.R.; Sethi, S.; Saha, S.; Sharma, V.K.; Singh, S. Chemical and nutritional evaluation of major genotypes of nectarine (Prunus persica var nectarina) grown in North-Western Himalayas. J. Food Sci. Technol. -Mysore 2019, 56, 4266–4273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogvar, O B; Rabiei, V; Razavi, F; Gohari, G. Phenylalanine alleviates postharvest chilling injury of plum fruit by modulating antioxidant system and enhancing the accumulation of phenolic compound. Food Technol. Biotech. 2020, 58, 433–444. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cercos, M; Soler, G; Iglesias, D J; Gadea, J; Forment, J; Talon, M. Global analysis of gene expression during development and ripening of citrus fruit flesh. A proposed mechanism for citric acid utilization. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 62, 513–27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashmi, H B; Negi, P S. Phenolic acids from vegetables: A review on processing stability and health benefits. Food Res.Int. 2020, 136, 109298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantharaju, P G; Gowda, P C; Vimalambike, M G; Madhunapantula, S V. An overview on the role of dietary phenolics for the treatment of cancers. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 99. [CrossRef]

- Stuper-Szablewska, K; Perkowski, J. Phenolic acids in cereal grain: Occurrence, biosynthesis, metabolism and role in living organisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. and Nutr. 2017, 59, 664–675.

- dos Santos Rocha, C; Magnani, M; Jensen Klososki, S; Aparecida Marcolino, V; dos Santos Lima, M; Queiroz de Freitas, M; Carla Feihrmann, A; Eduardo Barão, C; Colombo Pimentel, T. High-intensity ultrasound influences the probiotic fermentation of Baru almond beverages and impacts the bioaccessibility of phenolics and fatty acids, sensory properties, and in vitro biological activity. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113372.

- Wan, X; Wu, J; Wang, X; Cui, L; Xiao, Q. Accumulation patterns of flavonoids and phenolic acids in different colored sweet potato flesh revealed based on untargeted metabolomics. Food Chem.-X 2024, 23, 101551. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L L; Chen, L; Jiang, Y Q; Zhou, C; Liang, F H; Duan, L H. Role of exogenous melatonin in quality maintenance of sweet cherry: Elaboration in links between phenolic and amino acid metabolism. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103223.

- Clifford, M N; Ludwig, I A; Pereira-Caro, G; Zeraik, L; Borges, G; Almutairi, T M; Dobani, S; Bresciani, L; Mena, P; Gill, C I R; Crozier, A. Exploring and disentangling the production of potentially bioactive phenolic catabolites from dietary (poly)phenols, phenylalanine, tyrosine and catecholamines. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103068.

- Portu, J; López-Alfaro, I; Gómez-Alonso, S; López, R; Garde-Cerdán, T. Changes on grape phenolic composition induced by grapevine foliar applications of phenylalanine and urea. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 171–180. [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, V P; Papakyriakou, A; Vourloumis, D; Tsatsakis, A M; Spandidos, D A. Dietary flavonoids in cancer therapy and prevention: substrates and inhibitors of cytochrome P450 CYP1 enzymes. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 126, 9–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C; Zhou, X; Long, C; Du, Y; Li, J; Yue, J; Pan, S. Variations of flavonoid composition and antioxidant properties among different cultivars, fruit tissues and developmental stages of Citrus fruits. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, 201900690.

- Carr, A C; Rosengrave, P C; Bayer, S; Chambers, S; Mehrtens, J; Shaw, G M. Hypovitaminosis C and vitamin C deficiency in critically ill patients despite recommended enteral and parenteral intakes. Critical Care 2017, 21, 300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiani, G; Periago Castón, M J; Catasta, G; Toti, E; Cambrodón, I G; Bysted, A; Granado-Lorencio, F; Olmedilla-Alonso, B; Knuthsen, P; Valoti, M; Böhm, V; Mayer-Miebach, E; Behsnilian, D; Schlemmer, U. Carotenoids: Actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53 (Suppl. 2), S194–S218.

- Bernstein, P S; Li, B; Vachali, P P; Gorusupudi, A; Shyam, R; Henriksen, B S; Nolan, J M. Lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin: The basic and clinical science underlying carotenoid-based nutritional interventions against ocular disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 50, 34–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakushima, A; Maoka, T; Ohno, K; Coskun, M; Guvenc, A; Erdurak, C S; Ozkan, A M; Seki, K; Ohkura, K. Major antioxidative substances in Boreava orientalis(Cruciferae). Nat. Prod. Lett. 2000, 14, 441–446.

- Assefa, A D; Saini, R K; Keum, Y-S. Fatty acids, tocopherols, phenolic and antioxidant properties of six citrus fruit species: a comparative study. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 1665–1675. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y; Miura, L A; Araki, T; Yoshie-Stark, Y. Proximate composition and profiles of free amino acids, fatty acids, minerals and aroma compounds in Citrus natsudaidai peel. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 356–363. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A; Smith, J; Fulgoni, V L. The new hybrid nutrient density score NRFh 4:3:3 tested in relation to affordable nutrient density and healthy eating index 2015: analyses of NHANES data 2013-16. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1734. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H; Lee, C H; Nolden, A A; Kinchla, A J; Chen, B. Nutrient density, added sugar, and fiber content of commercially available fruit snacks in the United States from 2017 to 2022. Nutrients 2024, 16, 292. [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A; Fulgoni, V L. New nutrient rich food nutrient density models that include nutrients and myplate food groups. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 107.

- Lin, J J; Hui, D F; Kumar, A; Yu, Z G; Huang, Y H. Climate change and/or pollution on the carbon cycle in terrestrial ecosystems. Front. in Env. Sci. 2023, 11, 1253172.

| samples | number | Metabolites | Assigned score | ||

| FJ | GZ | ZG | |||

| Peeled | 1 | L-aspartic acid | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | D-β-phenylalanine | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 3 | L-glutamic γ-semialdehyde | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 4 | Hesperetin | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 5 | Hydrocinnamic acid | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 6 | 4-hydroxycinnamic acid | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 7 | DHA | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Total score | 7 | 13 | 19 | ||

| Whole | 1 | L-aspartic acid | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | L-glutamic-semialdehyde | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 3 | Isovitexin 2′-O-β-D-glucoside | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 4 | Isovitexin | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 5 | Trans-2-hydrocinnamate | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 6 | Trans-cinnamate | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 7 | Diosmetin | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 8 | Hydrocinnamic acid | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| 9 | β-carotene | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Total score | 9 | 21 | 20 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).