Highlights

-Darna pallivitta (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) has been an invasive pest in Hawaii since 2001.

-Aroplectrus dimerus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) introduced from Taiwan in 2004 and approved for field release in 2010 after rigorous host specificity testing.

-Mean field parasitism was 19% in major infested areas on Oahu Island.

-Number of male moths caught in lure traps was significantly reduced after parasitoid releases.

-An extant secondary pupal parasitoid decreases biocontrol effort on Oahu Island by 27%.

Graphical Abstract

Ventral view of a stinging nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta host (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) and 9 ectoparasitoid larvae (above) of Aroplectrus dimerus (yellow) and its hyperparasitoid Pediobius imbreus (black) in Hawaii, both (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae).

1. Introduction

The nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta (Moore), is a new immigrant pest to Hawaii that was first noticed in September 2001 after workers at a nursery on the east side of the island of Hawaii were being stung by a caterpillar while handling rhapis palms (Rhapis sp.), Arecaceae [1]. The moth was suspected of having entered the state on infested palm seedlings imported from Taiwan [2]. Immediately after its detection, an eradication attempt with pesticides was made but proved unsuccessful [3]. In January 2002, surveys showed its establishment on three surrounding farms where the larvae were found feeding on coconut palm, Cocos nucifera L., areca palm, Chrysalidocarpus lutescens Wendl, rhapis palm, Hawaiian ti, Cordyline terminalis Kunth, and Dracaena sp. Host plants were studied to include native plants also at risk [2,4]. Agricultural crops damaged by D. pallivitta include coffee, Coffea arabica L. (Rubiaceae), and macadamia, Macadamia integrifolia Maiden & Betche (Proteaceae) [3,5].

Darna pallivitta became well established in the Hilo area on the east side of the Hawaii Island (19° 43’ 26.8032’’ N and 155° 5’ 12.5628’’ W) and has slowly moved from the original infestation site southward into the Puna district (19° 32’ 30.4476" N, and 155° 6’ 3.6648" W). It was discovered in Kona on the west side of the island (19° 38’ 23.9784’’ N and 155° 59’ 48.9588’’ W) during September 2006 and at Kohala in the north side (20°7′55″N and155°47′38″W) during February 2007, both infestations likely resulting from movements of infested plants [1]. During June 2007, an infestation at a nursery on Oahu Island (21° 27’ 59.99" N and 157° 58’ 59.99" W) was discovered after nursery workers were being stung while handling areca palm plants, Dypsis lutescens (Wendland) Beentje & Dransfield (Arecaceae). The source of this infestation was believed to be the importation of palms from a nursery on the east side of Hawaii Island, where D. pallivitta is firmly established. A similar scenario occurred on Maui Island (20° 47’ 54.1068” N and 156° 19’ 54.9264” W) during July 2007, where a new infestation was found in an area nearby to plant nurseries [6].

The polyphagous habit of D. pallivitta increases its pest potential in Hawaii since its introduction. Field observations of feeding damage include both weedy (guinea grass, Megathyrsus maximus (Jacq.) B.K.Simon & S.W.L.Jacobs (Poaceae), mondo grass, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. (Asparagaceae), and ornamental plants commonly grown in residences and agriculture lands [2,7]. Damage to ornamental plants, including the many palm species grown in Hawaii, could result in economic losses to the nursery industry and homeowners. Horticulture and nursery products impacted by the limacodid pest are estimated at $84.3 million (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2018 value), [3]. Also potentially threatened by larval feeding are the endemic plant species [2,3]. Of medical importance are the stinging spines of the larva, which cause dermatitis (itching, burning, welts, and blisters) on contact with the skin. Reports of people being stung by D. pallivitta larvae typically increase during the summer months (May – October) due to moth population surges. Outbreaks in residential communities result in homeowners getting stung while working in their back gardens. Symptoms vary, depending on a person’s sensitivity. In some cases, required admission to clinics [7,8].

The distribution of this moth occurs in Asia: China, Indonesia and Java, Japan, western Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam. Host plants in those regions include Adenostemma sp., Areca sp., Breynia sp., coconut, Ficus sp., grasses, maize, and oil palm [9]. In the native region the moth is a minor pest of coconut palms, probably due to the presence of natural enemies that do not occur in Hawaii [10,11,12].

A biological control program was initiated by the Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) to survey the native Asian region for biocontrol agents and import them to Hawaii. Several parasitoids are recorded on Limacodid pests. The ectoparasitoid Aroplectrus dimerus was introduced in 2004 for evaluation. There were no detailed biological studies in the scientific literature for A. dimerus, therefore, host specificity and life cycle investigations were conducted in the HDOA Insect Containment Facility (ICF). We report on the host specificity tests, investigated the biology and identity, colonization on the islands, field assessment on the parasitoid’ performance, and the effect of an extant secondary parasitism. Male lure traps were evaluated for monitoring the population reduction during the years. Implications for biological control elsewhere were discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Explorations and Origin of the Parasitoid Colony

Host plants infested by Darna pallivitta species were located by one of us (LMN) during a survey in Taiwan at a Tien-wei nursery on 8 October 2004 (24° 04’ 18.56” N, 120° 33’ 44.48” E, 76 m). Parasitized larvae on ti plants (Cordyline terminalis), rhapis palms native to southern China and Taiwan, and miniature coconut palms were collected. Adult wasps began emerging from some parasitized caterpillars. Collections of additional live, unparasitized D. pallivitta larvae were made at two Ping-tung nurseries and were used for propagation of the emerging parasitoids from Tien-wei. Parasitoids were placed in perforated plastic snap cap vials (9 drams, 33.4 ml), honey and water were provided. A shipment of the parasitoids was hand-carried to Hawaii for host range study in the HDOA-ICF.

2.2. Identity of the Primary and Secondary Parasitoids

The two parasitoids associated with D. pallivitta in the field were examined. Detail diagnostic features are reported using keys and description of Lin 1963 [13] for Aroplectrus dimerus and Khan and Shafee 1982 [14] for Pediobius imberus. Parasitoids were collected on plants infested by D. pallivitta on Oahu Island. Initial identification of the primary parasitoid was made as Aroplectrus dimerus Lin (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) by Dr. Chao-dang Zhu on 6 December 2004, a taxonomist of the oriental species of Chalcidoidea at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, Peoples Republic of China, who compared the Taiwan specimens with those at the Natural History Museum (London, UK) and made the identification.

The photographs of card mounted specimens produced in this report are taken with a digital camera (Olympus Tough, TG –5) attached to a Leica M 125 stereomicroscope.

2.3. Host Propagation

Darna pallivitta larvae were reared in screened cages (42 x 42 x 62 cm, 70 mesh) and fed leaves of green Hawaiian ti, Cordyline fruticose (L.) A. Chev, (Asparagaceae); or iris, Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora (Lemoine) N.E.Br.; (Iridaceae). After pupating and adult emergence, about five female and five male moths were collected from the stock cage and placed in a wide-mouth, one-gallon glass jar with leaves (3.8 L). The newly emerged pairs were held for mating and egg-laying in the jar, provided with honey drops and water. A bouquet of ti or iris leaves, made with a strip of cotton wrapped around the petioles and snugly inserted into a flower tube vial (1.5 x 7.0 x 1.5 cm), was placed into the jar. The mouth of the jar was covered with organdy cloth and secured with rubber bands. Moths usually laid most eggs on the glass not on plants, the hatched larvae crawled from the glass onto the ti leaves to feed. As the larvae matured, the entire bouquet was transferred to a screened cage (30 x 30 x 60 cm, 70 mesh) for continued feeding and development.

A larval disease, identified as a cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CPV), later became entrenched in the HDOA-ICF, this was eliminated by rearing fewer larvae per cage (20 – 30 larvae).

2.4. Parasitoid Propagation

Aroplectrus dimerus was reared in a one-gallon glass jar (3.8 L) containing 15 host larvae (L6 – L10 instars) and five mated female parasitoids. Honey was dotted inside the jar as a food source for the wasps (SUE BEE® SPUN® siouxhoney.com/sue-bee-spun- honey). After a 7-day exposure period, the female wasps were removed to avoid extreme parasitism. A new generation of adult parasitoids began emerging two weeks after initial exposure.

2.5. Reproductive Parameters and Immature Measurements

The general longevity, fecundity, offspring sex ratio, and life cycle for A. dimerus were determined under insectary conditions (mean ± SEM, temperature 21.8 ± 0.12 °C, mean RH 70.2 ± 2.4 %, Light 12:12, D: L). Tests were performed on 40 newly emerged pairs on generations (July 2021 – April 2022). Pairs were held in Petri dishes (150.0 Ø x15.0 mm height) provided with honey and a water wick and a daily larval host until female death. Reproductive parameters were determined by observations of exposed larvae individually isolated in Petri dishes for microscopic observation. Data on daily fecundity (number of eggs laid/female/day), until the death of female, adult emergence rates, offspring sex ratio, and longevity of males and females were assembled. Immature developmental periods and measurements for eggs, larvae, and pupae were calculated for 15 individuals using a Leica M 125 stereomicroscope provided with eyepiece Micrometer.

2.6. Host Specificity Testing

In Hawaii, there are no other species in the family Limacodidae except

D. pallivitta, and there are no species represented in its superfamily Zygaenoidea (Dalceridae, Epipyropidae, Lacturidae, Limacodidae, Megalopygidae, and Zygaenidae) [15]. Hence, there were no Hawaiian species closely related taxonomically for host testing. Twenty-five Lepidoptera species, representing 13 families, were tested to determine if the parasitoid

A. dimerus would attack any non-target species. These included four beneficial species currently used for weed biological control, two Hawaiian endemics, and 19 immigrant pests (

Table 1). For some species, field-collected larvae were used for testing if they were found in abundance. For others, field-collected eggs, larvae, or adults were propagated in the laboratory for one or more generations to increase their numbers for testing.

All host specificity testing for A. dimerus was conducted in the HDOA-ICF (minimum temperature 18.7 C°, maximum temperature 24.1 C°, minimum RH 61.6 %, maximum RH 84.3 %, Light 12:12, D: L).

Host specificity evaluations were based on no-choice tests. Ten larvae of a Lepidoptera test species were placed in a one-gallon glass jar (3.8 L) with their food source and exposed to five newly emerged A. dimerus females for a 24-hour period. The respective larval food sources were pods, flowers, or leaf bouquets, placed in jars and replenished as necessary. The control replicate was done in the same way but with 10 D. pallivitta larvae and a bouquet of iris leaves as a food source. Honey and water were available for the wasps ad libitum.

After the exposure period, each test larva was removed from the jar and the number of parasitoid eggs counted on its body using a dissecting microscope. The 10 test larvae were then placed in another jar with their respective food source to continue feeding until moth or parasitoid emergence occurred. The same procedure was followed with the 10 control (D. pallivitta) larvae, however, because of their long-life cycle (≈ 10 weeks), [7]; the larvae were only held for parasitoid emergence (≈ 2 – 3 weeks). Parasitoids were used only once during testing, and their ages were the same for a test and control replicate. Two replicates of 10 larvae each were conducted for each Lepidoptera species, for a total of 20 larvae tested per species.

2.7. Colonization and Establishment Records on the Islands

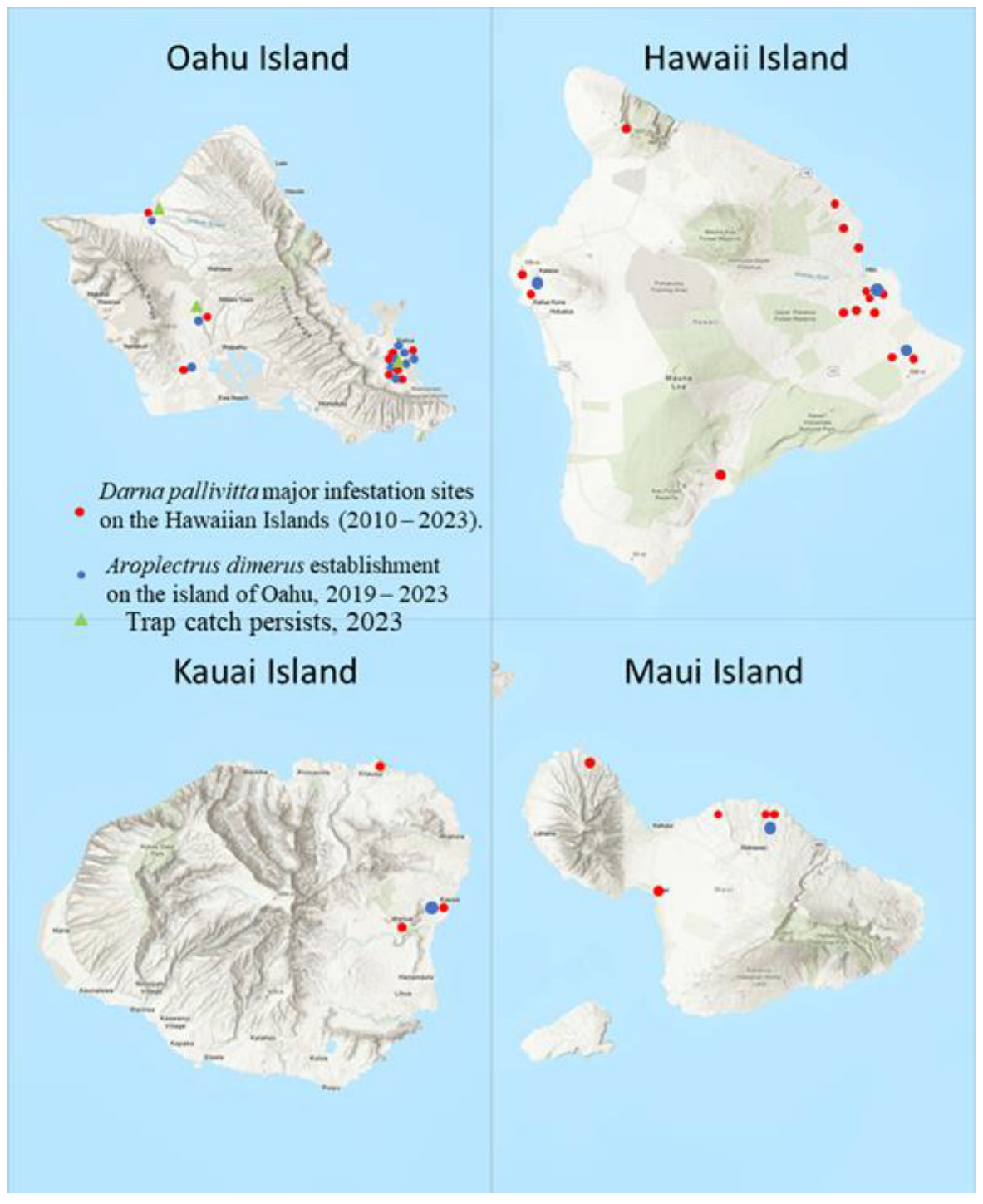

Parasitoids were released periodically on major infested sites on four Hawaiian Islands (Hawaii, Kauai, Maui, and Oahu). Parasitoid releases were conducted during 2010 – 2023 as needed to get the parasitoid established. Release sets and range of wasps per lot and total wasps released were recorded for every location by island. Release sites of major infested nurseries and homes were plotted on a map for all the infested islands. GPS were recorded using Google Earth Pro online, version 7.3 (

Figure 1).

2.8. Infestation Rates on Major Infested Sites on Oahu Island

A survey for pupal count was conducted by eight HDOA staff members during June 2007 before the introduction of parasitoids. Collection of D. pallivitta cocoons at the Tkenaka Nursery, Kipapa Gulch, Central Oahu Island (21° 27’ 32.80” N, 158° 00’ 57.32” W, 215 m), from a group of 1000 infested potted Areca palm plants, Dypsis lutescens. Pupae were examined and counted. Empty cocoons with circular opening in the cocoons were considered as early moths’ emergence, and the rest of the cocoons were held in insectary cages (30 x 30 x 60 cm, 70 mesh) for possible pupal parasitoid emergence. Larvae from infested areas were collected periodically and held in Petri dishes (150.0 Ø x15.0 mm height) with food provided until maturation or parasitoid emergence.

2.9. Rates of Parasitism on Oahu Island

This evaluation was possible on Oahu Island, which had the most parasitoid releases. Numbers of larvae collected, number of samples, total Darna larvae collected were held in Petri dishes under insectary conditions. Rates of parasitism were determined by the number of D. pallivitta larvae produced parasitoids and percentages of parasitism with the hyperparasitoid.

Hyper parasitism rates from field collections were determined by turning over parasitized caterpillars and checking for the amber-colored pupae of the primary parasitoid (A. dimerus) vs. the darkened pupae caused by the hyperparasitoid, Pediobius imbreus.

To confirm P. imbreus as a secondary parasitioid, we conducted a test in a Petri dish (150.0 Ø x15.0 mm height) with two nettle caterpillars previously parasitized by the primary parasitoid A. dimerus. The Aroplectrus larvae were allowed to feed on the caterpillar host for four days, two days before their pupation (i.e. before expelling the meconium the larval fecal waste discharged before pupation). Two female wasps of the hyperparasitoid P. imbreus were introduced into the Petri dish provided with honey and water. The female hyperparasitoids appeared to use their ovipositor to probe through the caterpillar body to locate the Aroplectrus larvae beneath the Darna caterpillar. The Aroplectrus larvae darkened about eight days after being hyperparasitized. Aroplectrus larvae that are not hyperparasitized are normally amber colored in the pupal stage.

2.10. Trapping

Synthetic Pheromone Lures, E7,9-10:COOnBu was synthesized by Pacific Agriscience, Singapore [16]. Red rubber septa were loaded with two amounts of E7,9-10:COOnBu, 250 lg for trap lures [16]. Traps were placed in infested areas and replaced once a month with the new lure. Male D. pallivitta were monitored in Hawaii, Maui, and Oahu islands during the years before and after the parasitoid’ releases. Year and number of traps monitored in Hawaii: 2009 (29 traps); Maui: 2007 (93 traps), 2009 (11 traps); and on Oahu: 2009 (27 traps), 2011 (12 traps), 2021 (67 traps), 2022 (135 traps), 2023 (106 traps). Traps were deployed in infested sites and lures were changed monthly with new traps per site.

2.11. Statistical Analysis and Vouchers

Analysis by One Way ANOVA and tTest analysis were performed for the sex ratio (% female offspring). Means trap catch per month were summarized for before and after evaluation analyzed by ANOVA for Oahu Island trap catches. The survivorship of female and male was recorded daily and analyzed using ANOVA. Mean survival time was also estimated for both sexes. Realized fecundity was estimated using the total number of progeny (±SEM) produced by each female wasp over her lifetime, and oviposition rates were estimated using the mean numbers of progeny (±SEM) produced per day by each female wasp. Statistical analyses and calculations were carried out with JMP Version 11 (SW) [17].

Vouchers specimens of the primary and secondary parasitoids were deposited at the Hawaii Department of Agriculture, and Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii. Vouchers of Aroplectrus dimerus was deposited in Zhu, C.D., Huang collection, Guangxi, China. Specimens of A. dimerus are deposited in the Natural History Museum (London, UK), the collections at the National Museum of Natural History (Washington D.C.), and the National Museum of Natural Science (Taichung, Taiwan). Vouchers of Pediobius imbrues are deposited at HDOA insect collection and the Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

3. Results

3.1. Exploration

The first effort to search for D. pallivitta natural enemies was a collaboration with Sam Ratulangi University located in Manado, Faculty of Agriculture, the Coconut Research Center in Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, collected during September 2003 (1° 27’ 19.94” N, 124° 49’ 37.62” E, 28 m). Three limacodid species were collected for parasitism (Pectinarosa alastor Tams, 30 cocoons; Thosea monoloncha Meyrick, 27 cocoons; both from coconut hybrid leaves; and Darna catenatus Snellen, 352 cocoons from palm oil, Elaeis guineensis Jacq. yielded the parasitoid, Nesolynx sp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) attacking the pupae as an ectoparasitoid emerging from the cocoon stage of D. catenatus. Testing in the HDOA-ICF showed this parasitoid to be a generalist as it parasitized two species of fly puparia (Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel), (Diptera: Tephritidae); and Trichopoda pilipes (Fabricius), (Diptera: Tachinidae), under laboratory conditions. Therefore, additional host range testing was abandoned. An earlier shipment from Manado, North Sulawesi by the same collector in September 2003, was not successful in producing any parasitoids, only dead larvae of limacodid arrived.

The second attempt to collect potential biological control agents was made in collaboration with the National Biological Control Research Center in Thailand during June 2004. Collections showed the limacodid Parasa lepida Cramer being attacked by an undetermined braconid wasp. However, the parasitoids died before any shipment made to Hawaii.

Further exploration was conducted in Taiwan during October 2004 by one of us (LMN) in collaboration with the Agricultural Research Institute (TARI), and Ping-tung University.

Darna pallivitta species was detected at a Tien-wei nursery on 8 October 2004 (Chang hua province, 24° 04’ 18.06” N, 120° 33’ 44.81” E, 77m). Parasitized larvae were found on ti plants (

Cordyline terminalis), rhapis palms, and miniature coconut palms. Adult wasps began emerging from the parasitized caterpillars. Collections of live, unparasitized

D. pallivitta larvae were also made at two Ping-tung nurseries (22° 48’ 40.69” N, 120° 35’ 46.00” 75 m) and those were used for propagation of the parasitoid from Tien-wei. One shipment of parasitoids was hand carried to Hawaii on 19 October 2004, for host range study in the HDOA-ICF. Wasps identified as

A. dimerus reached HDOA alive yielded 53 wasps (60.0%

) that were used for the colony rearing.

3.2. Identity of Parasitoids

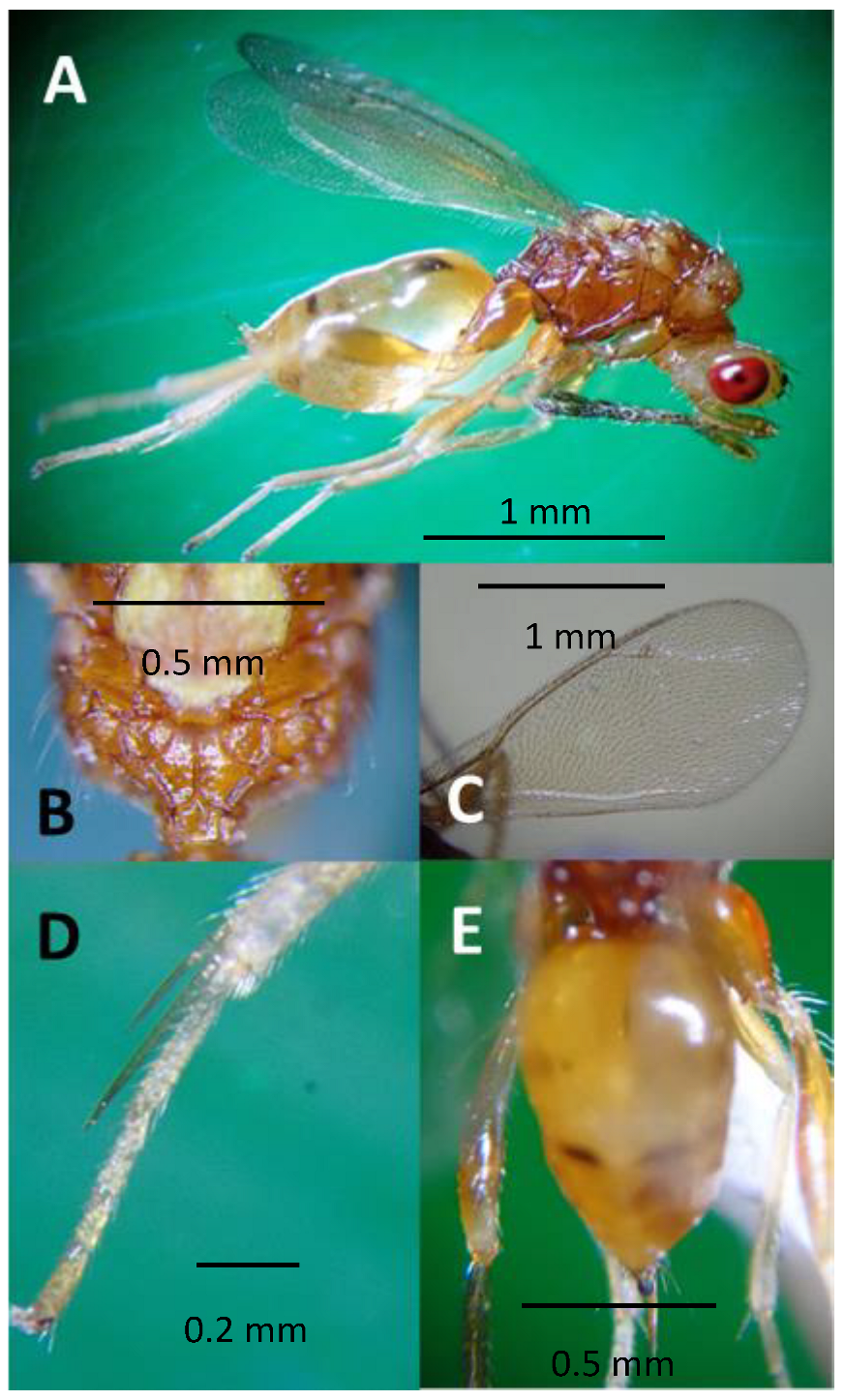

Aroplectrus is a genus of Hymenoptera: Eulophidae: subfamily Eulophinae, tribe Euplectrini, recognized with four segmented funicle, normal size wings, and metatibia with one spur distinctly longer than basitarsus. Six species are recorded: Aroplectrus areolatus (Ferrière), A. contheylae Narendran, A. dimerus Lin, A. flavescens (Crawford), A. haplomerus Lin, and A. noyesi Narendran [18,19].

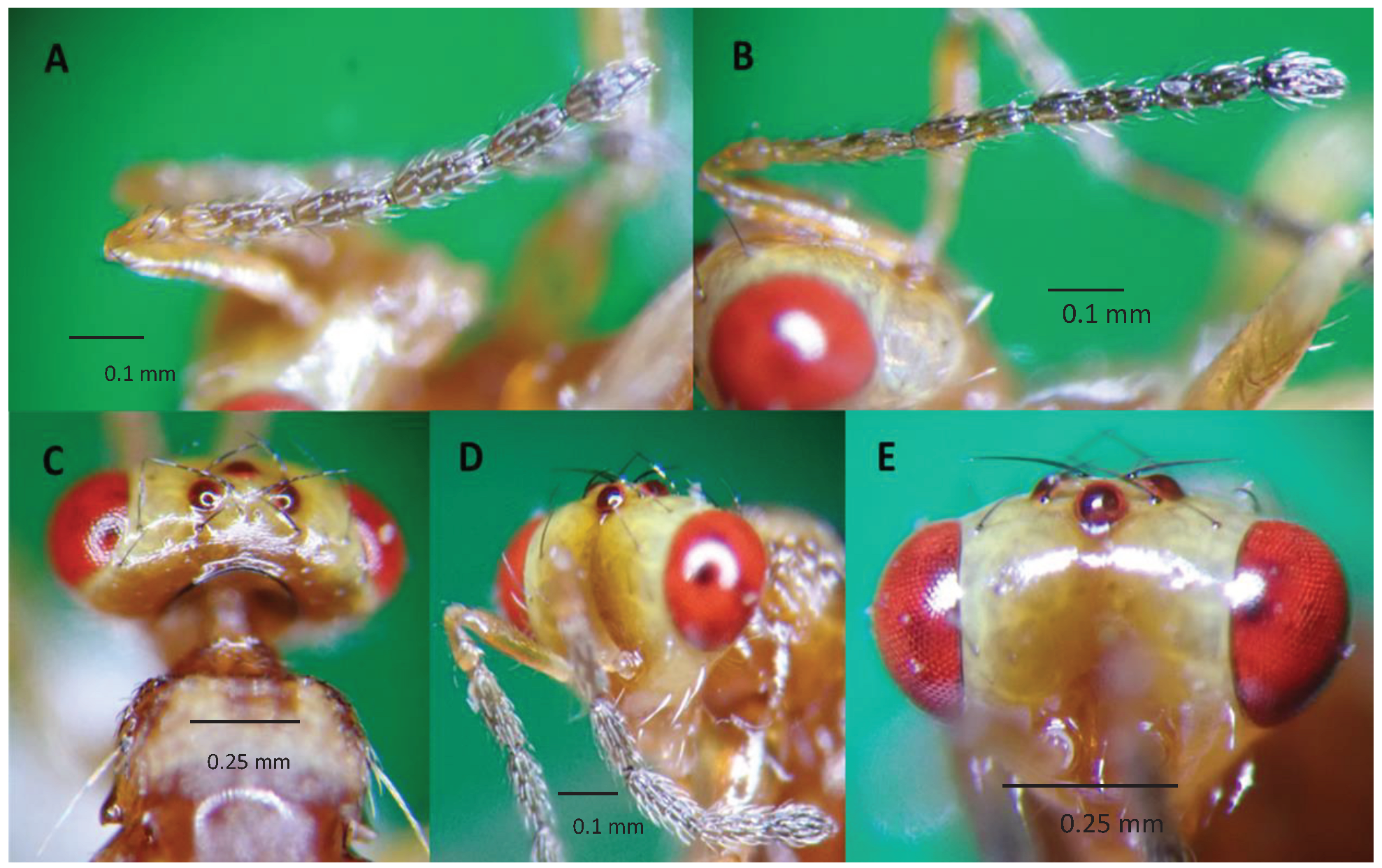

Aroplectrus dimerus has a general body color yellow, scape distinctly longer than eye, recognized with head much narrower than thorax (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), head in front view wider than high, clava shorter than FI (

Figure 3A), submedian propodeal areola divided completely into two sectors by a continuous oblique carina (

Figure 2B), hind basitarsus much longer than second tarsal segment, hind tibial spurs very long and strong reaching apex of second tarsal segment (

Figure 2D), scutellum without lateral grooves, and propodeum with a single strong median carina [13,18,20].

Recorded hosts are Parasa bicolor (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) and Cochliidae. This Oriental species reported to occur in mainland China: Guangxi (Napo, Pingxiang); Hainan (Yaxian), India, Indonesia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Thailand [13]. The parasitoid is specific to members of the family Limacodidae (7 species in 3 genera), [19]. In Hawaii there are no native limacodids.

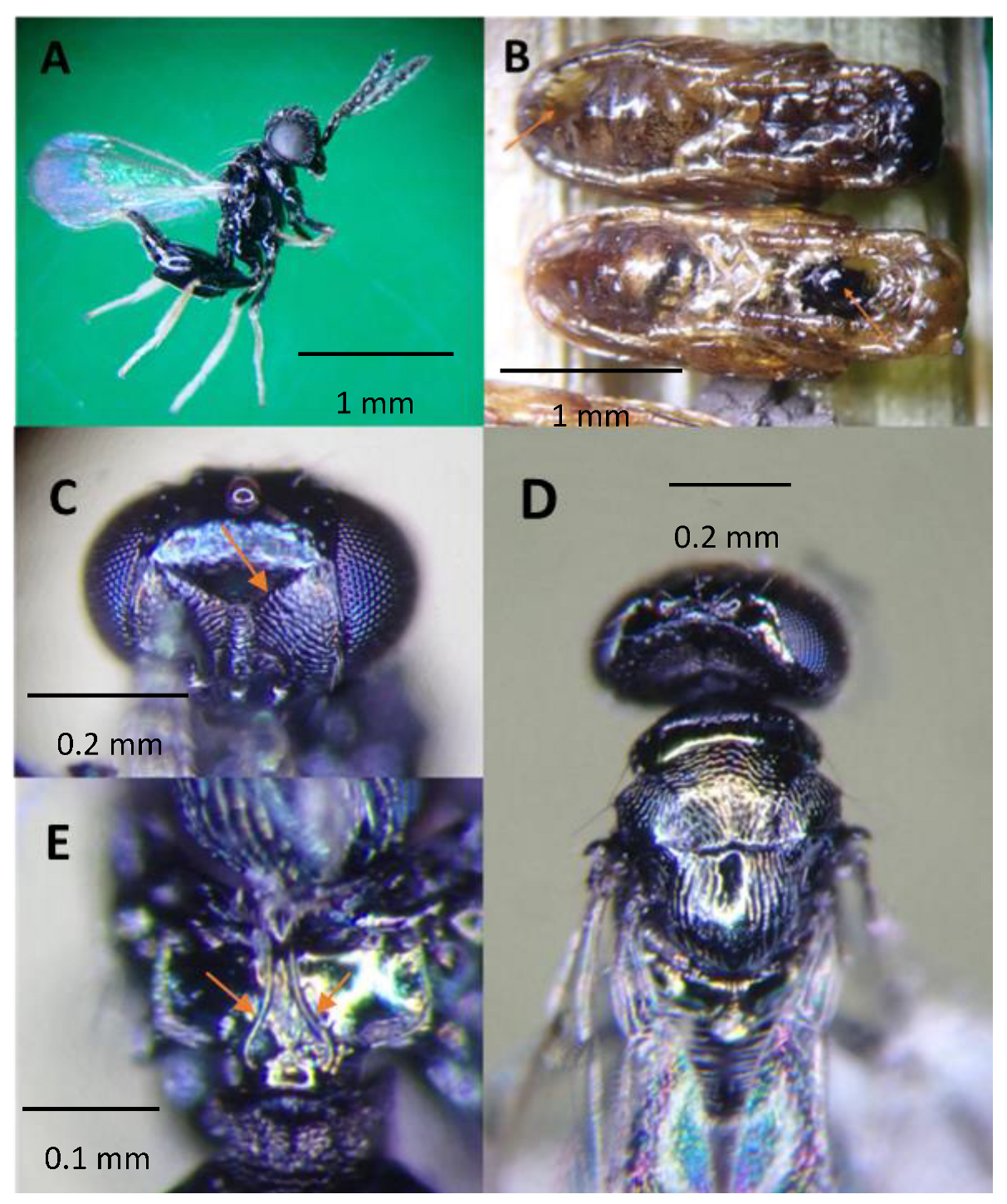

Pediobius is a large genus of Hymenoptera: Eulophidae with 217 known species worldwide [19,21]. It is composed by small wasps (0.8 – 1.6 mm), characterized by having propodeum medially with 2 subparallel carinae diverging posteriorly and with distinct plicae; frontofacial sutures distinct, petiole in most species with ventrally pointed extension [21].

The adult

Pediobius imbreus are hyperparasitoids collected from Waimanalo, Oahu Island are mostly dark with less metallic reflections, the female ≈ 1.6 mm in body length. The original description [23] and a redescription [

24] of

P. imbreus, indicated normal coloration with a blue-green iridescence, that matches older specimens in the HDOA insect collections dated between 1917–1951. However, the latest specimens from Waimanalo, Oahu, have a yellow-green iridescence. This difference may be a color variant. Color variation in specimens collected in 2023 as depicted in

Figure 4 differs in leg coloration. Similarly, the original description by Kerrich 1973 acknowledged the variation in leg and body coloration [

24].

The diagnosis of

P. imbreus includes V-shaped generally complete frontal sulcus, its arms reaching inner eye margins, separated, or somewhat fused, characterized by the relatively wide and robust head with elongate and narrowed lower face. Antennae attached near or below the lower eye margins (

Figure 4A). Propodeum with two submedian carinae diverging posteriorly [

25],

Figure 4E.

Pediobius imbreus hyperparasitoid adults emerged about 3 – 5 days longer than cited in Indian literature [

26], but the life cycle will probably vary for different hosts. Also, this test was done under the insectary air-conditioned laboratory, so the cooler temperature may have slowed the wasp development and increased the life cycle duration. Unlike what we observed in Hawaii, this parasitoid was reported as a primary parasitoid of Limacodid species in India [

27].

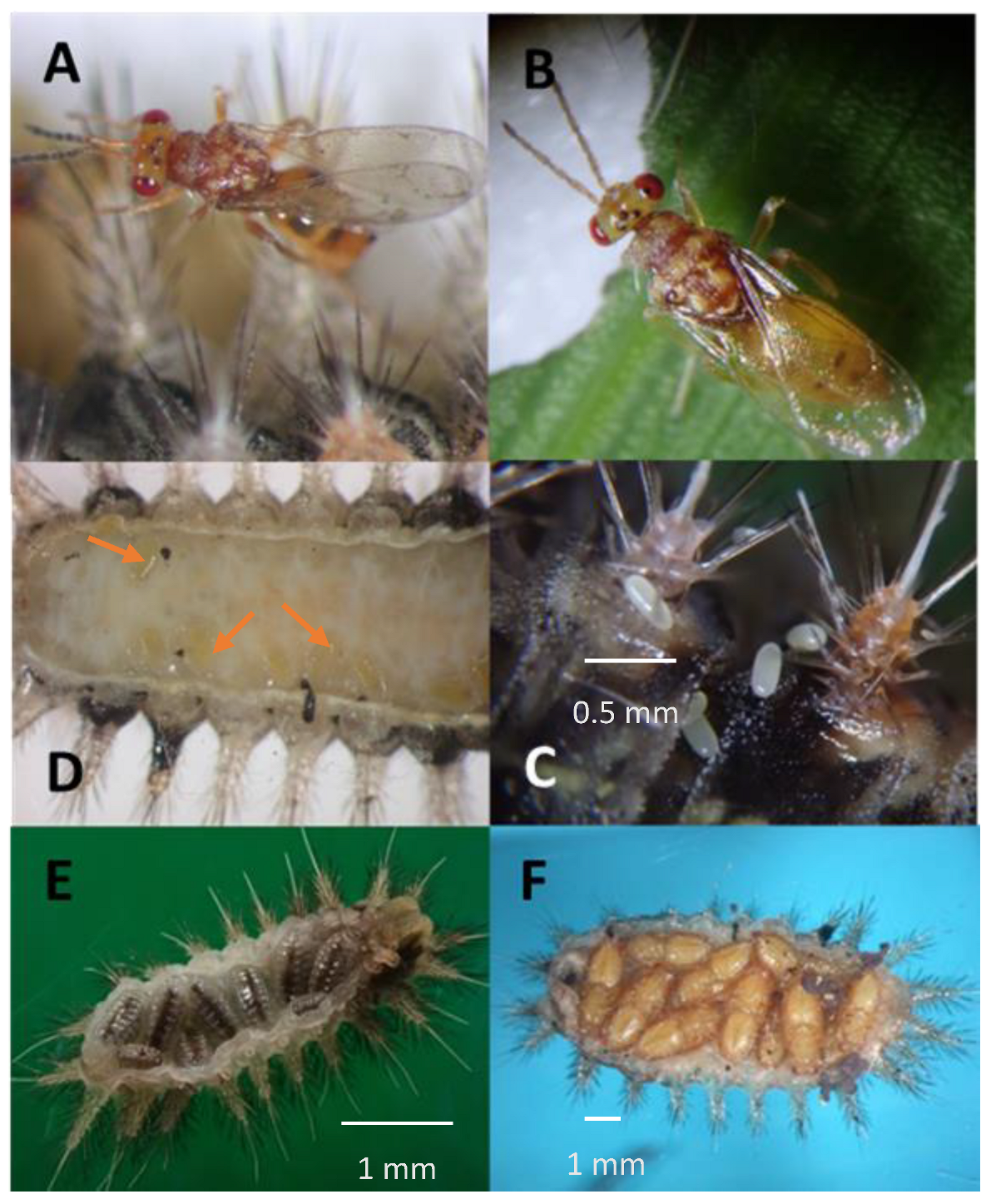

3.3. Life History and Reproductive Performance

Aroplectrus dimerus is a biparental, synovigenic species, i.e., females successively develop eggs to maturity throughout their reproductive life. It is an idiobiont ectoparasitoid and gregarious in habit, typically 5 –10 wasps developing from a single host larva, depending on the host size (

Figure 5E,F). The female first stings the host larva to paralyze it, inserting its ovipositor usually at the edges of the smooth ventral side. Melanized oviposition marks can be seen by microscopic examination on the belly side of larva (

Figure 5A). The

D. pallivitta larva attacked by a wasp may flail wildly and regurgitate a brownish liquid. Sometimes this killed the female parasitoid. The female wasp deposits individual eggs externally on the host larva, most laterally embedded between segments (

Figure 5C). The host larva becomes totally immobilized within two days and remains adhered to the leaf substrate. The wasp larvae hatch from the eggs within two days under laboratory conditions (2.0 ± 0.0 days, n = 14). The first instar migrates to the belly of the host larva (

Figure 5D) and feeds externally for 4.5 ± 0.14 days, n =14. Larvae remain concealed under the host’ body (

Figure 5E). Dark fecal material is clearly seen in the wasp’s gut as parasitoid larvae reach maturity. One day prior to pupation, the parasitoid meconium (waste product) is discharged as a brown, worm-like matter (

Figure 5F). The wasp pupae mature in 5.6 ± 0.2 days, n = 14 (

Figure 5F) and the adults then commence to emerge. The total life cycle is 10.6 ± 0.2 days, n =54 under laboratory conditions (

Table 2).

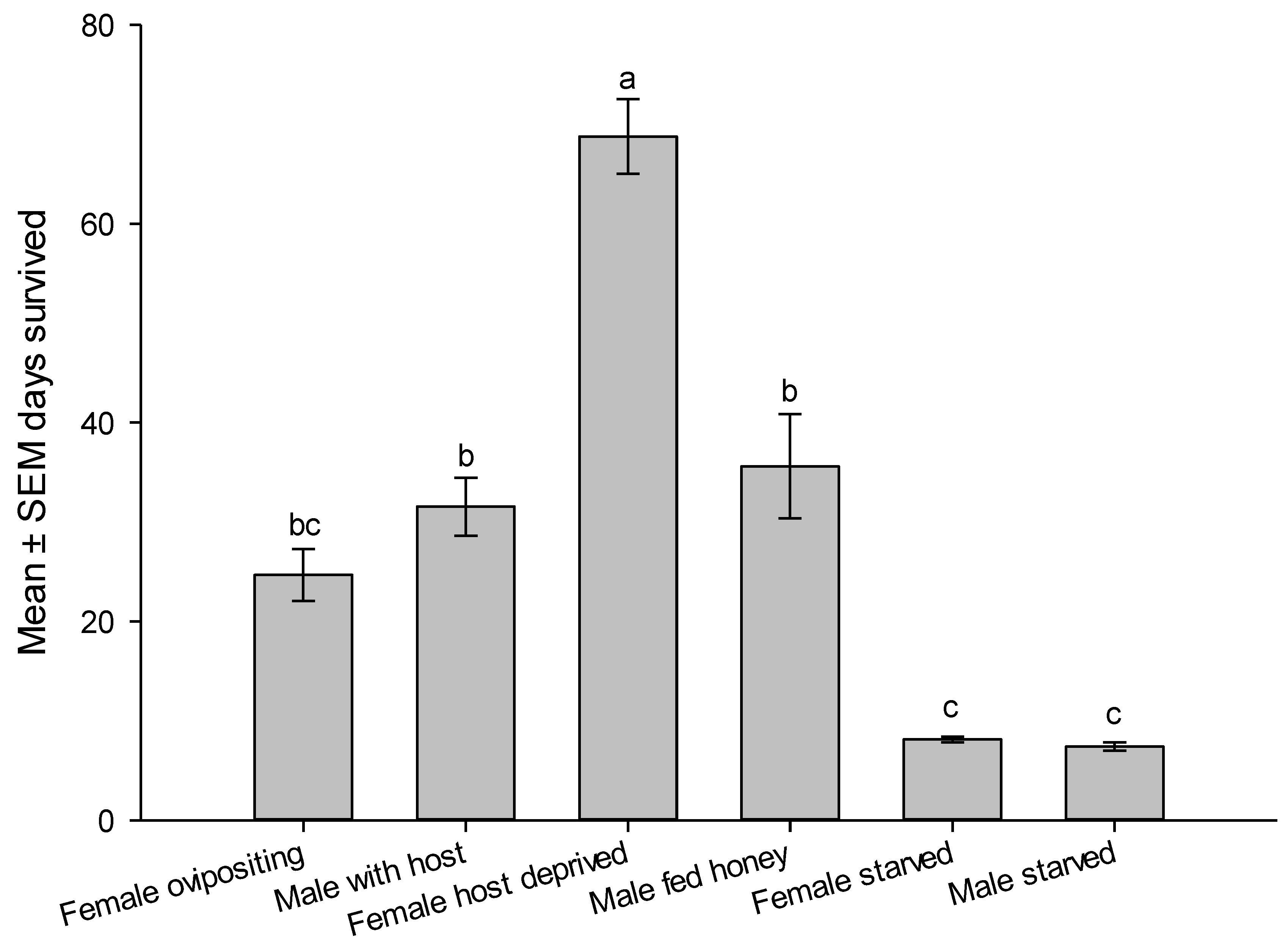

Reproductive parameters showed that female is readily mated as they emerge and ready for oviposition on the second day of emergence. Female continued to lay eggs for a week with a peak oviposition on 7.5 ± 0.8 day and peak laid eggs of 9.5 ± 0.5 eggs/day, n = 40. Realized fecundity was 41.7 ± 4.1eggs/female, n = 40 and 58.2 ± 3.0 % emergence rate, n = 15. Longevity of ovipositing female was 24.7 ± 2.6 days shorter than male longevity 31.5 ± 2.9 days. Males survived longer than ovipositing females (t

78 = 1.750,

P = 0.0420). However, host deprived female survived significantly longer than males or any other category of wasp supplied by honey and water, sometimes reached up to >2 moths (

Figure 6). Mated males survived the same periods as unmated honey fed males. Starved wasps died after one week if not given honey or water sources. Feeding on honey significantly increased survivorship of males and females (

Figure 6).

Percentage sex ratio female offspring (63.2 ± 3.0

, n = 40) was significantly higher than % male offspring (t

46 = – 6.1660,

P < 0.0001),

Table 2.

3.4. Host Specificity Tests

Choice test of host specificity showed that females

A. dimerus did not deposit any eggs on any tested larvae of the 25 non-target Lepidoptera species (

Table 3). Hence, there was no parasitoid emergence. All test larvae examined under a dissecting microscope showed no evidence of oviposition marks due to probing and there were no indications of larval regurgitation in the jar that usually seen due to attack by an

A. dimerus female. The female parasitoids also appeared to have no specific attractiveness to three larval species (

Agraulis vanillae,

Podomachla apicalis, and

Secusio extensa) that have long setae or hairs somewhat like

D. pallivitta.

Parasitism was recorded in all the control (

D. pallivitta) replicates for all Lepidoptera species tested. Analysis by One Way ANOVA showed a significant difference (

P < 0.05) for parasitism among all non-target Lepidoptera species compared with their controls. The number of

D. pallivitta larvae parasitized for a pair of replicates (n = 20 larvae) ranged from 40 – 85%, with an average of 4 –7 wasps emerging per parasitized larva. Sex ratio of offspring showed that all females were mated (

Table 3).

3.5. Colonization Records on the Islands

Parasitoids were released widely in Hawaii for several years 2010 – 2013. Establishment is now recorded throughout Hawaii Islands (

Figure 1). By 2011, infestation reports showed that pest numbers had declined by 80 –100% in HDOA survey sites (J. Yalemar, pers. comm., Hawaii Department of Agriculture). Total wasps released on four Islands was 13379 in 162 release sites in major infested areas during June 2010 – December 2022 (

Table 4,

Figure 1).

Table 4.

Colonization of Aroplectrus dimerus for biocontrol of Darna pallivitta on the Hawaiian Islands (2010 – 2023).

Table 4.

Colonization of Aroplectrus dimerus for biocontrol of Darna pallivitta on the Hawaiian Islands (2010 – 2023).

| Island |

locality |

Release period |

Major infestation release sites

GPS coordinates and elevation |

Release sets and range wasps/lot |

Total wasp released |

| Oahu Island |

Waimanalo, Winward Oahu 2010 |

17 May 2010 –

18 November 2010 |

Ahiki,

(21°20’ 08.42” N, 157° 42’ 58.88” W, 27 m) |

12 (50 – 441) |

1494 |

| “ |

Waimanalo 2010 |

9 October 2010 –

3 December 2010 |

Leilani Nursery,

(21° 20’ 32.52” N, 157° 43’ 26.16” W, 21m)

C & L Nursery,

(21° 19’ 38.78” N, 157° 42’ 57.10” W, 89 m) |

5 (50 –110) |

310 |

| “ |

Waimanalo 2011 |

13 January 2011 –

8 June 2011 |

Ahiki,

(21° 20’ 08.42” N, 157° 42’ 58.88” W, 27 m) |

5 (50 – 100) |

400 |

| “ |

Central Oahu 2010 |

8 June 2010 –

1 November 2010 |

Kipapa Gulch,

21° 27’ 32.80” N, 158° 00’ 57.32” W, 215 m)

Uka Elem. Sch, Mililani

(21° 26’ 14.33” N, 158° 00’ 55.49” W, 179 m)

Poloahilani St, Mililani

(21° 26’ 51.10” N, 158° 00’ 12.34” W, 212 m) |

12 (20 – 386) |

849 |

| “ |

Central Oahu 2011 |

2 February 2011 –

14 June 2011 |

Noholoa Park, Mililani

(21° 26’ 29.16” N, 158V 00’ 29.55” W, 184 m)

Takenaka’s Nursery, Wahiawa

(21° 25’ 44.31” N, 158° 00’55.56” W, 151 m) |

5 (50 –200) |

610 |

| “ |

Windward Oahu 2021 |

3 October 2021 –

16 December 2021 |

Olomana

(21° 21’55.00” N, 157° 44’ 22.61” W, 56 m)

Lanikai

(21° 23’ 30.78” N, 157° 42’ 56.97” W, 5 m)

Enchanted lake,

(21° 23’ 05.17” N, 157° 44’ 04.84” W, 5 m) |

9 (40 – 70) |

526 |

| “ |

Winward and North Oahu 2022 |

15 February 2022 –

20 December 2022 |

Haleiwa

(21° 35’ 33.15” N, 158° 06’ 12.88” W, 1 m)

Pauahilani st. kaillua

(21° 23’29.96” N, 157° 43’ 27.53” W, 21 m) |

22 (50 – 100) |

1465 |

| “ |

Winward and Central Oahu 2023 |

6 February 2023 –

23 August 2023 |

Maunawili

(21° 22’50.57” N, 157° 45’ 22.49” W, 37 m)

Kaululena St. Mililani

(21° 27’ 17.52” N, 158° 00’ 13.31” W, 222 m) |

8 (40 – 220) |

880 |

| Hawaii Island |

North Kona 2010 |

5 August 2010 –

30 October 2010 |

3-Ring ranch, Kailua, Kona

(19° 38’ 37.21´ N, 155° 57’ 55.67” W, 252 m)

Loloa Way

(19° 43’ 29.75” N, 155° 59’ 27.00” W, 325 m)

Hawaiian Sunshine

(21° 20’ 26.44” N, 157° 43’ 0324” W, 13 m) |

7(40–100) |

420 |

| “ |

North Hilo and Puna 2010 |

16 June 2010 –

12 November 2010 |

Umauma,

(19° 54’ 18.50” N, 155° 08’ 28.8” W, 115 m)

Kurtistown,

(19° 35’34.87” N, 155° 03’ 27.95” W, 200 m)

Stainback (UH Exptl. Sta.)

(19° 39’ 11.48” N, 155° 02’ 58.20´W, 77 m) |

7 (50 – 250) |

800 |

| “ |

Kona, North Kohala, North, South Hilo 2011 |

16 January 2011 –

21 March 2011 |

Puna Orchids, Kapoho

(19° 29’ 50.97” N, 154 ° 57’ 03.03” W, 190 m)

Kohala

(20° 14’ 15.25” N, 155° 49’ 07.74” W, 158 m)

Onomea

(19° 48’ 31.67” N, 155° 05’ 45.24” W, 87 m)

Akaka Falls

(19° 51’ 14.25” N, 155° 09’ 07.47” W, 366 m)

Panaewa, Umauma

(19° 39’ 34.28” N, 155° 02’ 50.93” W, 57 m) |

31 (50 – 100) |

2725 |

| “ |

Hilo, Puna, districts 2011 |

27 January 2011 –

8 February 2011 |

Pahua

(19” 27’ 41.80” N, 154” 56’ 25.71 W, 294 m)

Panaewa,

(19° 39’ 34.28” N, 155° 02’ 50.93” W, 57 m)

Kurtistown,

(19° 35’34.87” N, 155° 03’ 27.95” W, 200 m) |

4 (50) |

200 |

| Maui Island |

North shore and East Maui 2010

|

3 August 2010 –

23 November 2010 |

Haiku

(20° 55’ 02.87” N, 156° 19’ 32.93” W, 144 m)

Hana, Maliko Gulch

(20° 55’ 54.48” N, 156° 20’ 19.66” W, 11 m) |

9 (50 – 200) |

910 |

| “ |

North Shore 2011 |

25 February 2011 –

26 August 2011 |

Twin Falls off, Hana.

(20° 54’ 43.80” N, 156° 14’ 34.31” W, 148 m) |

6 (50 – 150) |

640 |

| Kauai Island |

East and North districts 2010 |

19 October 2010 |

Kuamoo Rd, Kapaa

(22° 03’ 27.94” N, 159° 22’ 52.16” W, 98 m)

Kiluea, Kauai Orchids

(22° 11’ 51.05” N, 159° 22’ 34.09” W, 109 m) |

5 (15 – 100) |

200 |

| “ |

East district 2011 |

5 May 2011 –

30 August 2011 |

Kapaa, Transfer Station

(22° 05’ 00.14 “N, 159° 19’ 26.43” W, 21 m) |

15 (25 – 100) |

950 |

| Total releases and mean/locality |

162

(release sites) |

13,379

836.2 ± 158.8 |

3.6. Field Parasitism and Establishment

Total samples of larvae collected on Oahu Island where 3923 larvae had a mean of 18.9 ± 5.6 % parasitism by

A. dimerus. The culprit hyperparasitoid

P. imbrues had a mean rate of 27.3 ± 7.6 % parasitism (

Table 5). Initial hyper parasitism on Oahu nursery during July – September 2010: revealed that out of 100 larvae collected had hypers in 46.8 ± 12.8 % of collected larvae during four dates in July – September 2010 surveys at Waimanalo infested sites, n = 4. Hyper parasitism was also found on Kailua, Kona, Hawaii Island (19° 43’ 05.05” N, 155° 59’ 49.65” W, 438 m) on 20 September 2021. No record of hyper parasitism was reported from other islands.

Table 5.

Darna pallivitta infestation and parasitism rates on the island of Oahu, 2019 – 2023. Hyperparasitoid identified as Pediobius imberus (Hymenotera: Eulophidae).

Table 5.

Darna pallivitta infestation and parasitism rates on the island of Oahu, 2019 – 2023. Hyperparasitoid identified as Pediobius imberus (Hymenotera: Eulophidae).

| date |

locality |

No. of samples |

Total Darna larvae collected |

Darna larvae/sample

Mean ± SEM |

Total larvae Parasitized by Aroplectrus

|

% parasitism by Aroplectrus

|

Total larvae with hyper

parasitoid |

% parasitism by Pediobius

|

| 10 September 2019 |

Enchanted lake, Kailua |

1 |

52 |

52 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

24 September 2009 –

23 December 2019 |

Lanikai |

12 |

812 |

67.7 ± 8.9 |

52 |

6.4 |

5 |

9.6 |

23 October 2019 –

10 December 2019 |

Waimanalo |

3 |

125 |

41.7 ± 7.9 |

10 |

8.0 |

1 |

10.0 |

| 27 November 2019 |

Kipapa Gulch |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

27 January 2020 –

18 October 2020 |

Lanikai |

4 |

77 |

19.3 ± 4.1 |

16 |

20.8 |

4 |

25.0 |

| 28 July 2020 |

Kailua |

1 |

20 |

20 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

16 October 2020 –

16 December 2020 |

Maunawili Loop, Kailua |

3 |

261 |

87.0 ± 27.2 |

2 |

0.8 |

2 |

100 |

| 23 January 2020 |

Waimanalo |

3 |

54 |

18.0 ± 7.2 |

5 |

9.2 |

5 |

100 |

4 January 2021 –

26 July 2021 |

Haleiwa |

4 |

47 |

11.7 ± 6.7 |

3 |

6.4 |

1 |

33.3 |

| 10 March 2021 |

Waimanalo |

7 |

58 |

8.3 ± 3.8 |

38 |

65.5 |

5 |

13.1 |

7 April 2021 –

11 August 2021 |

Maunawili, Kailua |

6 |

51 |

8.5 ± 3.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

7 April 2021 –

20 October 2021 |

Lanikai |

11 |

314 |

28.5 ± 5.9 |

23 |

7.3 |

0 |

0 |

5 August 2021 –

11 November 2021 |

Olomana |

6 |

466 |

77.7 ± 17.9 |

36 |

7.7 |

0 |

0 |

14 June 2021 –

16 December 2021 |

Enchanted Lake, Kailua |

6 |

417 |

69.5 ± 25.3 |

26 |

6.2 |

0 |

0 |

19 January 2022 –

15 October, 2022 |

Enchanted lake, Kailua |

6 |

41 |

6.8 ± 1.8 |

18 |

43.9 |

2 |

11.1 |

23 February 2022 –

6 December 2022 |

Maunawili |

2 |

24 |

12.0 ± 8.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

11 January 2022 –

20 December 2022 |

Lanikai |

8 |

239 |

29.9 ± 7.0 |

26 |

10.9 |

1 |

3.8 |

19 January 2022 –

26 September 2022 |

Olomana |

8 |

262 |

32.7 ± 7.7 |

121 |

46.2 |

65 |

53.7 |

9 March 2022 –

12 July 2022 |

Waimanalo |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

| 10 November 2022 |

kaillua |

1 |

13 |

13 |

0 |

|

|

|

10 January 2023 –

23 October 2023 |

Lanikai |

8 |

248 |

31.0 ± 9.1 |

12 |

4.8 |

1 |

8.3 |

18 January 2023 –

31 October 2023 |

Olomana |

5 |

125 |

25.0 ± 7.0 |

70 |

56.0 |

27 |

38.6 |

18 January 2023 –

28 July 2023 |

Enchanted lake, Kailua |

2 |

5 |

2.5 ± 0.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

28 April 2023 –

23 August 2022 |

Mililani |

4 |

59 |

14.7 ± 6.4 |

5 |

8.5 |

3 |

60.0 |

6 February 2023 –

21 August 2023 |

Waimanalo |

2 |

50 |

25.0 ± 13.0 |

4 |

8.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

Mean ± SEM /site

|

|

|

|

28.22 ± 4.9

|

18.76 ± 5.6 |

18.93 ± 5.6 |

5.86 ± 3.2 |

27.30 ± 7.6 |

All samples

|

|

117 samples (25 sites) |

3923 larvae |

|

469 larvae |

|

123 larvae |

|

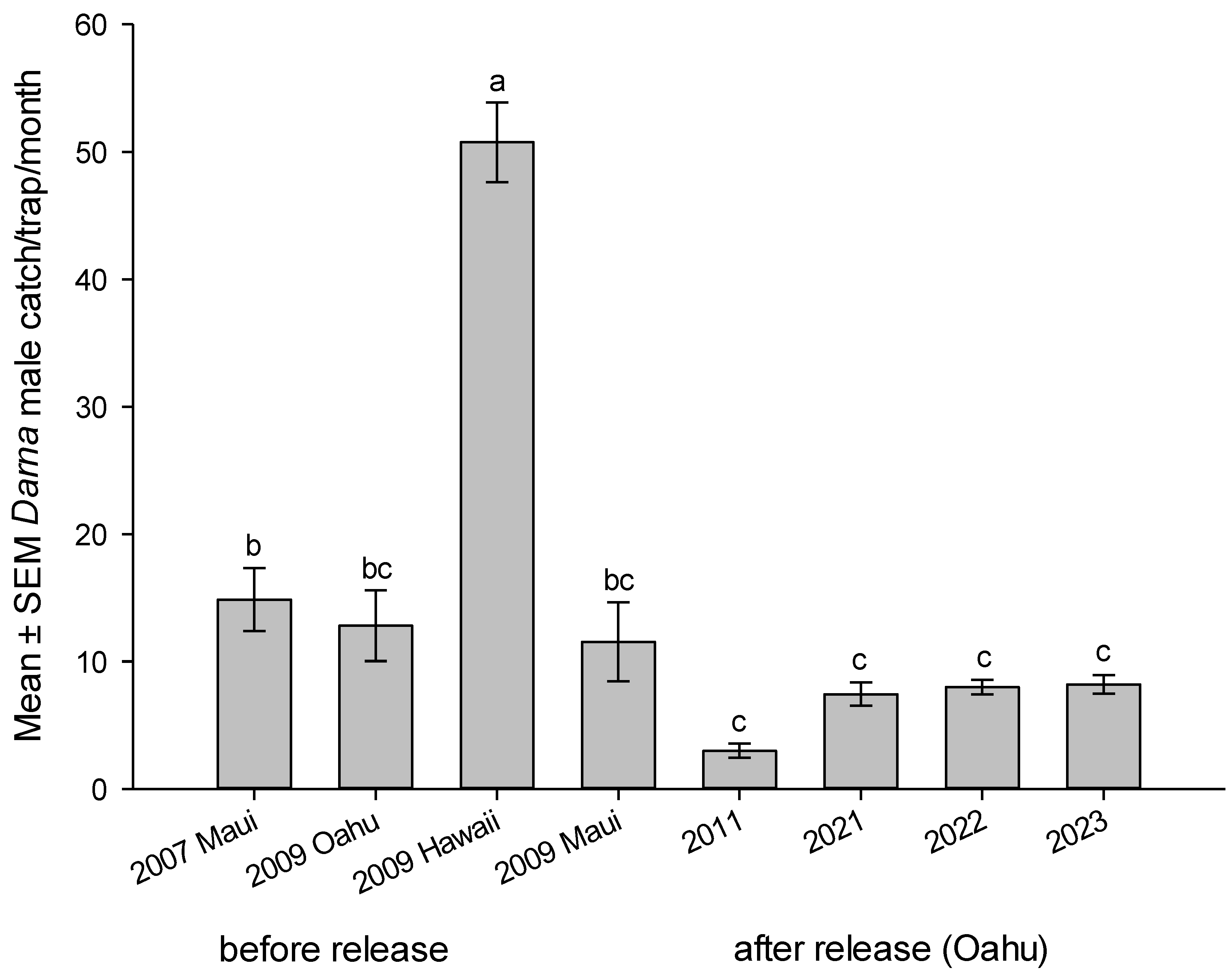

3.7. Male Trap Catches and Pupal Infestation

Pheromone-baited traps are routinely used to monitor

D. pallivitta abundance and spread, and to help document population changes associated with releases of its parasitoid,

A. dimerus [

28]. Numbers of males caught/trap/month was recorded on major infested sited on the islands. Mean number of males caught per month during the years were reported before and after the parasitoid liberations. Results indicated a significant reduction in trap catches during the years before and after parasitoid releases on Oahu Island (2009 vs 2011 – 2023), (F

1, 478 = 81.5149,

P < 0.0001),

Figure 7.

Mean number of

D. pallivitta lured into male pheromone trap per month on the Hawaiian Islands before parasitoid release during 2007, 2009 and after parasitoid establishment during 2011, 2021 – 2023 on Oahu Island was significantly different (F

7, 472 = 31.6429,

P <.0001),

Figure 7. Trends in moth abundance of

D. pallivitta on Oahu and neighboring Islands indicated a significant reduction of the pest. Trap catch after the release of parasitoid (n = 320, mean 7.76 ± 0.39 moths) vs. trap catch before the release (n = 160, mean 22.83 ± 2.23 moths), was significantly different (t ratio 6.663044, df = 169.0413,

P < 0.0001).

Hand-removal of pupae was a rigorous task, and the result was a limited degree of control. Up to 50 cocoons have been removed from a single infested potted plant. The plants had been sprayed with Talstar (

https://www.pedchem.com/products/talstar-proinsecticide? variant=40105878847642), accessed on 2 January 2024. The survey in that nursery revealed high infestation within the two-day survey, some cocoons were empty (700 cocoons / two days survey). Total plants examined was 1308 (327 ± 31.7 plants /day) had a total of 17733 sound pupae (4433.3 ± 949.6 cocoon/day) and a mean of 13.56 ± 2.87 cocoons/plant. This survey was conducted before the introduction of parasitoids illustrates the magnitude of infestation and how the parasitoid mitigated that influx of infested plants,

Figure 8E.

4. Discussions

We report for the first time in literature on various aspects of host range testing, reproductive biology, eventual releases, and field parasitism of the

A. dimerus in the Hawaiian Islands. Our rearing indicates a highly specialized parasitism in the laboratory and after many years of field releases. Besides

A. dimerus, no other parasitoids were detected in Hawaii to mitigate the limacodid pest except for the egg parasitism by

Trichgramma. However, the study did not continue to verify the effectiveness of egg parasitoids as biocontrol agents of Limacodidae. Parasitism of eggs by

Trichogramma papilionis (Nagarkatti) was recorded in Hawaii by Conant et al 2006 [

29] before the introduction of

A. dimerus. Mean parasitism calculated for 70 sentinels exposed egg batches was 4.4 ± 2.19 % parasitism, during September 2003 – December 2004 in the Panaewa area, Hawaii Island [

29]. The number of eggs per survey lot ranged from 1 – 162 eggs [2]. No additional

Trichogramma have ever been discovered in March 2006. This could be another biotic factor undetermined in recent years.

Another unexplored mortality factor for this pest is the larval disease cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CPV). Apparently, the disease was much established in the larval population of D. pallivitta under laboratory conditions. Out of 212 field-collected larvae, a mean of 26.6 ± 9.8 %, n = 13, were diseased by CPV [2].

The reproductive parameters of this parasitoid could be essential information for developing a mass rearing protocol. Field colonization, and determination of rates of parasitism under field condition has greatly enhanced our knowledge on this parasitoid under field conditions. No biological assessments were published in information data for all the tribe Euplectrini [19].

Aroplectrus dimerus is known from China, India, Philippines, and Taiwan [10,

30,

31,

32]. Host records are limited to larvae of Limacodidae [

30,

33]. None of the published records listed

Darna pallivitta as a host prior to this report during exploration and our host testing.

Darna palllivitta was discovered in Okinawa, Japan with no report of utilizing parasitoids [

34].

Aroplectus dimerus has adjusted well to parasitize

D. pallivitta in Hawaii. Prior to oviposition, the female injects a venom that inhibits further ecdyses of the host which hinder further molting of the caterpillar to advanced instars. The parasitoid larvae suck haemolymph out of the caterpillar leaving a dried carcass of the larvae (

Figure 5). Mature larvae of the parasitoid are protected by the dried host remains; therefore, they do not spin cocoons as other members of the tribe Euplectrini [22]. Euplectrini are polyphagous or oligophagous solitary or gregarious ectoparasitoids of lepidopterous larvae. The biology of most Euplectrini species has not been explored or considered for biocontrol elsewhere, with no data in scientific literature from any of the native lands.

Aroplectrus Lin (1963) has not been found in Sri Lanka closer to India [

35].

There are 6 records of Aroplectrus on the Universal Chalcidoidea data base (Aroplectrus areolatus (Ferriere) (from Indonesia, Sulawesi, and Malaysia ectoparasitoid on Darna catenate, and Setora nitens); Aroplectrus contheylae Narendran (from India, Kerala associated with Limacodidae on Arecaceae and Cocos nucifera); Aroplectrus dimerus Lin; Aroplectrus flavescens (Crawford) (from Philippines); Aroplectrus haplomerus Lin, (from Taiwan); and Aroplectrus noyesi Narendran, (from Thailand) [19]. Lin 1963 [13] in his description of A. dimerus did not record any hosts. His materials were collected by sweeping in open grassland and undergrowth of primary forests near Taipei, Taiwan. Leaving this report as the novel host association on D. pallivitta during our exploration in Taiwan.

The biology of this parasitoid and related species of

Aroplectrus and the Euplectrini are not known from literature [

36].

Aroplectrus dimerus distributed in India, Uttar Pradesh, Peoples’ Republic of China, Guangxi (Kwangsi), Philippines, and Taiwan in association of Limacodidae larvae. Among the host larvae are

Parasa bicolor,

Penthocrates sp. infesting mainly Family: Poaceae (

Saccharum officinarum).

In the scientific literature,

A. dimerus has been recorded attacking six limacodid species in the Philippines [10,

31]; these are

Darna mindanensis Holloway,

Penthocrates albicapitata Holloway,

P. rufa Holloway,

P. rufofascia Holloway,

P. styx Holloway, and

P. zelaznyi Holloway. In India, the limacodid

Parasa bicolor Walker is also a recorded host [

30]. In this report we included

D. pallivitta as a new important host record for this parasitoid. Noyes (2019) in his database listed no additional species as hosts [19].

The culprit

Pediobius imbreus is an adventive secondary parasitoid of

A. dimerus larvae and pupae on Oahu and Hawaii Islands [15]. Most associated with species of Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera, and Hymenoptera as primary or secondary parasitoids [

37]. Some species are known from spider egg sacs where they may act as secondary parasitoids [

37]. Limacodid host associations in North America are newly reported herein [

38].

Pediobius imbreus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) was first recorded attacking the beneficial wasp A. dimerus, shortly after its release on Oahu Island. Field collections of parasitized caterpillars during July 2010 showed presence of the hyperparasitoid at a Waimanalo, Oahu nursery. Monthly collections of parasitized caterpillars from September – December 2010 yielded 50% hyper parasitism.

Biologically, species of

Pediobius are quite diverse, acting as primary or secondary parasitoids, utilizing eggs, larvae, and pupae of species in the insect orders Coleoptera, Diptera, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Mantodea and Thysanoptera [

36,

39].

Pediobius imbrues has also been recorded as a primary parasitoid of Limacodiid pests in India [

26,

27]. However, primary parasitism was not observed in the Hawaii infestations.

Pediobius imbrues with a natural incidence ranging from 2 – 10 % was observed in slug caterpillar affected gardens and laboratory studies of this parasitoid revealed that it is a hyper parasitoid on

Bracon hebetor and its parasitization efficiency and longevity on slug caterpillar was recorded [

40].

In preliminary field efficacy study of

P. imbrues against slug caterpillar

M. nararia, 41.4 % patriotization was recorded. Therefore, the advantage of

P. imbrues can be explored as a potential parasitoid for

M. nararia in coconut plantations [

40]. More observations are needed in Hawaii to determine if it has a primary mode of parasitism on

D. pallivitta.

Pediobius imbreus was described from India where it is recorded as a hyperparasitoid of Hymenoptera through their lepidoptera hosts. For example, the coconut black-headed caterpillar,

Opisina arenosella (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae), is attacked by three species of primary parasitoids (

Apanteles taragamae Viereck, and

Bracon brevicornis (Wesmael) (Braconidae) and

Goniozus nephantidis (Muesebeck) (Bethylidae), but each of these were hyperparasitized by

P. imbreus [

26,

27,

40].

Indian literature showed the biology of P. imbreus in a laboratory study using Bracon brevicornis as a host. The female lays a single egg in the prepupal stage of the primary parasitoid. This generalist hyperparasitoid P. imbreus, a wasp that is already established in Hawaii collected in 1917, reared from the cocoon of the braconid wasp Bracon omiodivorus Terry, a common parasitoid of caterpillars in Hawaii. Also, reared from the ichneumonid wasp Cremastus sp. (HDOA insect collection, 1949).

In the Hawaiian literature,

P. imbreus was previously known as

Pleurotropis sp. in 1917, and then later reported as

Pleurotropis detrimentosus. According to Yoshimoto (1965),

P. imbreus is established on all major islands of Hawaii [

41]. It is unknown what impact

P. imbreus could have on the effectiveness of

A. dimerus in Hawaii. Further sampling of field-collected caterpillars will be necessary.

Lastly, we record the importance of our primary parasitoid that we continue to release in Hawaii beginning in 2010 as part of a biological control program against the invasive limacodid

Darna pallivitta [

29,

42,

43]. Although neither

D. pallivitta nor

A. dimerus are currently known from the U.S.A., it is likely that the limacodid will be introduced into California given its history of interception at ports [

44,

45]. Were this to happen, it is possible that

A. dimerus would be introduced for mitigation of a new infestation [

38].

Before this biocontrol agent was introduced to Hawaii, almost all the plants on the farm were heavily infested with pest larvae so that foliage was marked with holes and many plants were close to defoliation. Six to eight months after the release of parasitoids, pest larvae were considerably suppressed, and moth trap catches had dropped dramatically.

Within a year or two of the release of

A. dimerus, the pest had stopped spreading and was becoming difficult to find. Reported rates of parasitism were small and mostly affected by hyper parasitism. Which makes us speculate if we need more new parasitoids for

D. pallivitta in Hawaii. Perhaps more surveys for pupal and egg parasitism are required in Hawaii. At present, we are content because the public has no complaints [

46]. Other islands are still free of infestation [

47].

5. Conclusion

The collection of D. pallivitta on palm plants at a Taiwan nursery in 2004 was an important conclusion because of its minor pest status in that country. The second crucial finding was of the eulophid wasp A. dimerus parasitizing D. pallivitta caterpillars adding a new host record for this important parasitoid unreported in the Chalcidoidea information data sets [19]. Natural enemies found in the native range of a pest are more likely to have evolved with its host and therefore have greater specificity. Our studies showed that A. dimerus is highly specific and did not attack any of the Lepidoptera species tested.

Darna pallivitta is still restricted to the islands of Hawaii, Maui, and Oahu [1,

47].

Aroplectrus dimerus releases could mitigate any new infestation on the islands of Lanai and Molokai. Field collection from infested islands for redistribution of parasitoids for fast biocontrol releases could be achieved. This also could be rendered a quick recovery of established colony for release in mainland USA if that need arose.

Darna pallivitta would probably be able to establish in southern California, Florida, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and southern Texas [

48]. The larvae and cocoons were intercepted several times in California [

48]. A survey in Hawaii in the sites mentioned in this manuscript would be effective in finding a new starter colony for possible release elsewhere.

Data on our rearing and reproductive performance on the D. pallivitta hosts are novel in literature. A petition for field release A. dimerus was successful and the wasps were liberated on the islands of Hawaii in major areas known to harbor Darna infestation after 6 years of its importation. This wasp, however, has had only limited effect on the nettle caterpillar population on Hawaii because of hyper parasitism. A hyperparasitoid affecting the population of this parasitoid reaching up to 27%. No other parasitoids of D. pallivitta were discovered on the islands. Thousands of cocoons were collected during the years with no pupal parasitoids. It seems that A. dimerus is the only parasiotid recorded on this pest until the present time. No further study on the effect of many Trichogramma egg parasitoids on the islands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.T.N., J.A.Y., M.M.R. and L.M.N; methodology, W.T.N. J.A.Y, M.M.R., and R.C.B; software, M.M.R.; validation, M.M.R. and J.A.Y; formal analysis, M.M.R. and W.T.N.; investigation, W.T.N., J.A.Y., M.M.R., and R.C.B; resources, M.M.R. and J.A.Y.; data curation, M.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, W.T.N., L.M.N, and M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, J.A.Y., M.M.R., L.M.N, and R.C.B; visualization, M.M.R.; supervision, W.T.N., J.A.Y., and R.C.B; project administration, W.T.N.; funding acquisition, W..T.N., and R.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the University of Hawaii during the project period. This work was supported by grants from USDA APHIS PPQ, Cooperative agreement no.10-8510-1346-CA (June 1, 2010 – May 31, 2011) USDA APHIS PPQ to HDOA.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the funding provided by UH researcher Arnold Hara. We thank our HDOA colleagues, Clyde Hirayama, Chris Kishimoto, and Patrick Conant for providing D. pallivitta larvae for parasitoid rearing. We also thank Leila Valdivia-Buitriago for providing endemic Udea caterpillars for host testing. Larry Nakahara acknowledges the assistance during exploration in Taiwan provided by Jai-Hsueh Lin, staff of the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute (TARI), nurserymen from Tien-wei Village and Ping-tung County, and entomology students from Ping-tung University for assistance during his survey in Taiwan. The authors greatly value the reviewer’s comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Conant, P. , Hara, A.H., Nakahara, L.M., and Heu, R.A. Nettle caterpillar Darna pallipitta Moore (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae). New Pest Advisory, State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture. 2002, No. 01– 03.

- Kishimoto, C.M. The stinging nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta (Moore) (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Hawaii: its current host range, biology, and population dynamics. Master of Science Thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa. 2006, 91 pp.

- Hara, A.H. , Kishimoto, C.M., Niino-DuPonte, R.Y. Host range of the nettle caterpillar Darna pallivitta (Moore) (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Hawai’i. In: Potential Invasive pests of agricultural crops, [ed. by Peňa, J.E.]. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. 2013, 183 – 191.

- Chun, S. , Hara, A., Niino-DuPonte, R., Nagamine, W., Conant, P., Hirayama, C. In: Stinging nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta, pest alert. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii. 2011, 2 pp. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9fa2bd14-6088-4d29-a9cce40a0b56a6e5/content. 6088. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.B. , Siderhurst, M.S., Conant, P., and Siderhurst, L.A. Phenology and population radiation of the nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta (Moore) (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Hawai’i. Chemoecology. 2009, 19: 7-12.

- Anonymous. Nettle Caterpillar, Darna Pallivitta (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae). Maui Nature, Invasive Species. Nettle Caterpillar https://www.mauiinformationguide.com/nettle-caterpillar.php. (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Nagamine Walter, T. and Epstein Marc E. Chronicles of Darna pallivitta (Moore 1877) (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae): biology and larval morphology of a new pest in Hawaii. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 2007, 83(2):120 –135.

- Ramadan, Mohsen M., Kaufman, Leyla V., Wright, Mark G. Insect and weed biological control in Hawaii: Recent case studies and trends. Biological Control, 2023.Volume 179, 105170. ISSN 1049-9644. [CrossRef]

- Areces-Berazain Fabiola. Darna pallivitta (nettle caterpillar), CABI Compendium. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cock, M.J.W. , Godfray, H.C.J., and Holloway, J.D. editors. Slug and nettle caterpillars: the biology, taxonomy and control of the Limacodidae of economic importance on palms in South-East Asia. 1987, 270 pages. Wallingford: C.A.B. International.

- Holloway, J.D. The moths of Borneo. Part I. Key to families; Families Cossidae, Metarbelidae, Ratardidae, Dudgeoneidae, Epipyropidae and Limacodidae. Malayan Nature Journal (Malaysia). 1986, 40 (1/2).

- Holloway, J.D. The Moths of Borneo. 2006, Accessed on January 8, 2024, http://www.mothsofborneo.com/part-1/limacodidae/limacodidae-42-7.php.

- Lin, K.S. Revision of the tribe Euplectrini from Taiwan. Part 1. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae.) Quarterly Journal of Taiwan Museum. 1963, 16: 113 16(1&2), 101-124. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y. , Shafee, Shaikh Adam. Species of the genus Pediobius Eulophidae Entedontinae from India, The journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1982, 79, Vol. 73; No 2; PP. 370-374. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/156894.

- Nishida, G. Hawaiian terrestrial arthropod checklist, fourth edition. G.M. Nishida, ed. Honolulu. 2002, 262 pp. http://www2.bishopmuseum.org/HBS/checklist/query.asp?grp=Arthropod.

- Siderhurst, Matthew S., Jang, Eric B., Hara, Arnold H., Conant, Patrick. n-Butyl (E)-7,9-decadienoate: sex pheromone component of the nettle caterpillar, Darna pallivitta Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2007, 125: 63–69, 2007. [CrossRef]

- JMP®, Version <11>. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2023.

- Narendran, T.C.; Fousi, K.; Rajmohana, K.; Mohan, C. A new species of Eulophidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) parasitoid on the slug caterpillar pest, Contheyla rotunda Hampson (Lepidoptera: Cochliidae) of coconut in Kerala. Journal of Applied Zoological Researches. 2002, 13(1) pp. 31-34.

- Noyes, J. UCD: Universal Chalcidoidea Database (version Sep 2007). In: Roskov Y., Ower G., Orrell T., Nicolson D., Bailly N., Kirk P.M., Bourgoin T., DeWalt R.E., Decock W., Nieukerken E. van, Zarucchi J., Penev L., eds. (2019). Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life. 2019, Annual Checklist. Digital resource at www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2019. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-884X.

- Narendran, T.C. Fauna of India, Eulophinae (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) pp. iii+442pp, Zoological Survey of India, Eulophidae. 2011, pages 1 – 342.

- Hansson, C. Eulophidae of Costa Rica (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea), 1. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute. 2002, 67: 1-290.

- Hansson C, Smith M.A., Janzen D.H., Hallwachs W. Integrative taxonomy of New World Euplectrus Westwood (Hymenoptera, Eulophidae), with focus on 55 new species from Area de Conservación Guanacaste, northwestern Costa Rica. ZooKeys. 2015, 485:1-236. https://doi. org/10.3897/zookeys.458. 9124.

- Walker, F. Characters of some undescribed species of Chalcidites. (Continued). Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 1846, 17, 177–185.

- Kerrich, G.J. A revision of the tropical and subtropical species of the eulophid genus Pediobius Walker (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Entomology. 1973; 29, 115–200. [Google Scholar]

- Schauff, M.E. The Holarctic genera of Entedoninae (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). Contributions of the American Entomological Institute. 1991, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.M. and Abdurahiman, U.C. On the biology of Pediobius imbreus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), a hyperparasite of Opisina arenosella, the black-headed caterpillar of coconut. COCOS. 1988, 6: 27-30.

- Ghosh, S.M. , Chandrasekharan, K. and Abdurahiman, U.C. The bionomics of Pediobius imbreus (Hymenoptera) and its impact on the biological control of the coconut caterpillar. Journal of Ecobiology. 1993, 5(3): 161-166.

- Siderhurst, Matthew S.; Jang, Eric B.; Carvalho, Lori A. F. N.; Nagata, Janice T.; and Derstine, Nathan T. Disruption of Darna pallivitta (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) by Conventional and Mobile Pheromone Deployment. J. Insect Sci. 2015, 15(1): 67. [CrossRef]

- Conant, P., Hirayama, C. K.; Kishimoto, C. M.; and Hara, A. H. Trichogramma papilionis (Nagarkatti), the first recorded Trichogramma species to parasitize eggs in the family Limacodidae. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 2006, 38: 133–135.

- Singh, B.P.; Singh, R.P.; and Verma, V.D. New record of Aroplectrus dimerus Linn. [sic] and Platyplectrus sp. as a larval parasite of slug caterpillar (Parasa bicolor Walk) [sic] from U.P. Farm Science Journal. 1988, 3(2): 199-200. http://trophort.com/002/169/002169592.html.

- Philippine Coconut Authority. The small limacodid Pethocrates sp. a pest on coconut. CPD Technoguide. 1999, No. 5. http://www.pca.da.gov.ph/pdf/techno/limacodid.pdf.

- Zhu, C.D.; and Huang, D.W. A taxonomic study on Eulophidae from Guangxi, China (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Acta Zootaxonomica Sinica. 2002, 27(3):583-607.

- Fry, J. M. Natural enemy databank, 1987. A catalogue of natural enemies of arthropods derived from records in the CIBC Natural Enemy Databank, p. 94. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxford, UK. 1989, 185 pp.

- Yoshimoto, H. Darna pallivitta (Moore) from Okinawa I., a limacodid moth new to Japan. Japan Heterocerists’ Journal. 1997, 192273-274. http://publ.moth.jp/tsushin/151-200/jhj192.pdf.

- Wijesekara, G.A.W. and Gunawardena, Thelma. A Synopsis of the Tribe Euplectrini of Hymenoptera Eulophidac) of Sri Lanka. Tropical Agricultural Research. 1989, Vol. 1, 114 – 1120.

- Bouček, Z. Australian chalcidoidea (Hy.); A. Biosystematic Revision of genera of fourteen families, with reunification of species. Commonwealth Institution of Entomology. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK. 1988, 832 pp.

- Peck, O. The taxonomy of the Nearctic species of Pediobius (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), especially Canadian and Alaskan forms. Canadian Entomologist. 1985, 117: 647–704. [CrossRef]

- Gates, Michael W.; Lill, John T.; Kula, Robert R.; O’Hara, James E.; Wahl, David B.; Smith, David R.; Whitfield, James B.; Murphy, Shannon M.; and Stoepler, Teresa M. Review of Parasitoid Wasps and Flies (Hymenoptera, Diptera) Associated with Limacodidae (Lepidoptera) in North America, with a Key to Genera. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 2012, 114(1), 24 –110,. [CrossRef]

- Budhachandra Thangjam, Khan; M. A., Pandey, Sunita; and Manhanvi, Kalmesh. A new species of genus Pediobius Walker (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) with new records of eulophid parasitoids from Uttarakhand, India. Pantnagar Journal of Research. 2013, 11(1): 29. [Google Scholar]

- Chalapathi Rao, N.B.V.; Padma, E.; and Ramanandam, G. Pediobius imbrues (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), a promising parasitoid of coconut slug caterpillar, Macroplectra nararia Moore (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Andhra Pradesh J Pest Management in Horticultural Ecosystems. 2017, V 23, P 176-178.

- Yoshimoto, C.M. Title: Synopsis of Hawaiian Eulophidae including Aphelininae (Hym.: Chalcidoidea). Pacific Insects. 1965, 7(4):665 – 699.

- HDOA. Natural enemy of stinging caterpillar to be released on O’ahu. News Release. 2010, 10 – 07. Available from: http://hawaii.gov/hdoa/news/2010-news-releases/natural-enemyof-stinging-caterpillar-to-be-released-on-o-ahu. [accessed May 15, 2011].

- HDOA. Kaua’i residents asked to report sightings of stinging caterpillar. News Release. 2011,11-11. Available from: http://hawaii.gov/hdoa/news/news-releases-2011/kaua-i-residentsasked-to-report-sightings-of-stinging-caterpillar. [accessed 8 June, 2011].

- California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). Darna pallivitta, p. 21. California Plant Pest andDisease Report. 2005, 22: 1–76.

- California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). Darna pallivitta, p. 12. California. Plant Pest and Disease Report. 2006, 23: 1–117.

- Bautista, R.C.; Yalemar, J.A.; Conant, P.; Arakaki, D.K.; and Reimer, N. Taming a stinging caterpillar in Hawaii with a parasitic wasp. Biocontrol News and Information. 2014, 35(2) 9N – 17N. https://www.cabi.org/BNI.

- Matsunaga, Janis N.; Howarth, Francis G.; and Kumashiro, Bernarr R. New State Records and Additions to the Alien Terrestrial Arthropod Fauna in the Hawaiian Islands. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 2019, 51(1) 1–71.

- Koop, A.L. New Pest Advisory Group Report. Darna pallivitta Moore: Nettle Caterpillar. 2006, https://download.ceris.purdue.edu/file/3058www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/cphst/npag/downloads/Darna_pallivitta_NPAG_et_Report_060505.pdf [accessed on 8 February 2024].

Figure 1.

Map of major infestation sites, parasitoid colonization, and establishment on the Hawaiian Islands (sizes of the islands are not in scale). Sampling locations with GPS coordinates are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5. (Oahu Island GPS coordinates of 21°18′56.1708″ N, 157°51′29.1348″ W; Hawaii Island with the GPS coordinates of 19°44′30.3180″ N, 155°50′39.9732″ W; Kauai Island with GPS coordinates of 22°6′30.7548″ N, 159°29′48.3540″ W.; Maui Island with GPS coordinates of 20° 47’ 54.1068’’ N and 156° 19’ 54.9264’’ W. [

https://www.latlong.net (accessed on 13 December 2023)].

Figure 1.

Map of major infestation sites, parasitoid colonization, and establishment on the Hawaiian Islands (sizes of the islands are not in scale). Sampling locations with GPS coordinates are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5. (Oahu Island GPS coordinates of 21°18′56.1708″ N, 157°51′29.1348″ W; Hawaii Island with the GPS coordinates of 19°44′30.3180″ N, 155°50′39.9732″ W; Kauai Island with GPS coordinates of 22°6′30.7548″ N, 159°29′48.3540″ W.; Maui Island with GPS coordinates of 20° 47’ 54.1068’’ N and 156° 19’ 54.9264’’ W. [

https://www.latlong.net (accessed on 13 December 2023)].

Figure 2.

Aroplectrus dimerus A) female side habitus, curved down mesosoma in profile along dorsal margin, overall body color yellow and reddish, scape longer than eye, head narrower than mesosoma, smooth hind coxae; B) scutellum finely granulate with longitudinal carinae, propodeum, median carina weak, submedian areola divided completely into two sectors by a continuous oblique carina; C) forewing hayaline, densely pilose veins brownish wing post-marginal vein longer than stigmal vein; D) elongate metatibial spur longer than basitarsus, not reaching apex of second tarsal segment; E) gaster, female metasoma shorter and narrower than mesosoma, oblong-ovate in dorsal view unicolor, gaster showing dark bands and black ovipositor sheath, ovipositor exerting beyond abdominal apex, smooth hind coxae.

Figure 2.

Aroplectrus dimerus A) female side habitus, curved down mesosoma in profile along dorsal margin, overall body color yellow and reddish, scape longer than eye, head narrower than mesosoma, smooth hind coxae; B) scutellum finely granulate with longitudinal carinae, propodeum, median carina weak, submedian areola divided completely into two sectors by a continuous oblique carina; C) forewing hayaline, densely pilose veins brownish wing post-marginal vein longer than stigmal vein; D) elongate metatibial spur longer than basitarsus, not reaching apex of second tarsal segment; E) gaster, female metasoma shorter and narrower than mesosoma, oblong-ovate in dorsal view unicolor, gaster showing dark bands and black ovipositor sheath, ovipositor exerting beyond abdominal apex, smooth hind coxae.

Figure 3.

Aroplectrus dimerus A) female antenna, funicle 4 segmented and a clava, F1 4X longer than broad, antenna with reddish scape, darker on funicle, female antenna, clava as long as F4; B) male antenna showing slender funicle and shorter clava, antennae more slender, club broader than funicle 1; C) showing vertex and yellow pronotum, head dorso-posterior view showing occipital carina feature, and quadrate pronotum with two side long sitae in the middle; D) dorso frontal view of head showing scape longer than eye and facial epistomal suture distinct straight , vertex with few black sitae and sparse cilia, malar space smooth shorter than eye, antenna with scape much longer than eye; E) head frontal facial view showing head wider than head length.

Figure 3.

Aroplectrus dimerus A) female antenna, funicle 4 segmented and a clava, F1 4X longer than broad, antenna with reddish scape, darker on funicle, female antenna, clava as long as F4; B) male antenna showing slender funicle and shorter clava, antennae more slender, club broader than funicle 1; C) showing vertex and yellow pronotum, head dorso-posterior view showing occipital carina feature, and quadrate pronotum with two side long sitae in the middle; D) dorso frontal view of head showing scape longer than eye and facial epistomal suture distinct straight , vertex with few black sitae and sparse cilia, malar space smooth shorter than eye, antenna with scape much longer than eye; E) head frontal facial view showing head wider than head length.

Figure 4.

Pediobius imbreus A) side habitus of female has body mostly dark with less metallic reflections, antennae inserted at lower level of eyes, coxae, trochanters, femora black, tibiae and tarsus coloration varied between specimens in HDOA collection, some specimens with all dark or all white, with or without metallic bluish reflections; B) exit holes from pupae of Aroplectrus dimerus (red arrows on exit holes anterior with hyper pupal molt, and posterior of pupa); C) head front view showing transverse frontal suture extended close to compound eyes; D) scutum reticulate, scutellum with longitudinal reticulate sculpture having median narrow smooth band, broad head pronotum and reticulate sculptured mesothorax; E) propodium with divergent middle carina and lateral propodeal plicae. Propodeum short, with submedian carinae diverging posteriorly.

Figure 4.

Pediobius imbreus A) side habitus of female has body mostly dark with less metallic reflections, antennae inserted at lower level of eyes, coxae, trochanters, femora black, tibiae and tarsus coloration varied between specimens in HDOA collection, some specimens with all dark or all white, with or without metallic bluish reflections; B) exit holes from pupae of Aroplectrus dimerus (red arrows on exit holes anterior with hyper pupal molt, and posterior of pupa); C) head front view showing transverse frontal suture extended close to compound eyes; D) scutum reticulate, scutellum with longitudinal reticulate sculpture having median narrow smooth band, broad head pronotum and reticulate sculptured mesothorax; E) propodium with divergent middle carina and lateral propodeal plicae. Propodeum short, with submedian carinae diverging posteriorly.

Figure 5.

A) female Aroplectrus dimerus on the host larva; B) female dorsal view showing color peculiarity; C) eggs laid on host larva between scolli; D) first instars A. dimerus migrate to the underside of host larva (black marks are female stinging marks to paralyze the host before oviposition not the feeding wounds by larvae; E) mature larvae consume the host still with uncharged prepupal meconia; F) pupae of the parasitoid underneath the host‘ cadaver, dark material between pupae are the vacated meconia.

Figure 5.

A) female Aroplectrus dimerus on the host larva; B) female dorsal view showing color peculiarity; C) eggs laid on host larva between scolli; D) first instars A. dimerus migrate to the underside of host larva (black marks are female stinging marks to paralyze the host before oviposition not the feeding wounds by larvae; E) mature larvae consume the host still with uncharged prepupal meconia; F) pupae of the parasitoid underneath the host‘ cadaver, dark material between pupae are the vacated meconia.

Figure 6.

Survivorship of male and female Aroplectrus dimerus under laboratory condition. All wasp categories fed honey and had access to water, except starved wasps. Different letters on top of bars indicate significant differences (ANOVA, P < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

Survivorship of male and female Aroplectrus dimerus under laboratory condition. All wasp categories fed honey and had access to water, except starved wasps. Different letters on top of bars indicate significant differences (ANOVA, P < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Mean number of Darna pallivitta lured into male pheromone trap per month on the Hawaiian Islands before parasitoid release during 2007, 2009 and after parasitoid establishment during 2011, 2021 – 2023 on Oahu Island. Different letters on top of bars indicate significant differences (ANOVA, P < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Mean number of Darna pallivitta lured into male pheromone trap per month on the Hawaiian Islands before parasitoid release during 2007, 2009 and after parasitoid establishment during 2011, 2021 – 2023 on Oahu Island. Different letters on top of bars indicate significant differences (ANOVA, P < 0.0001).

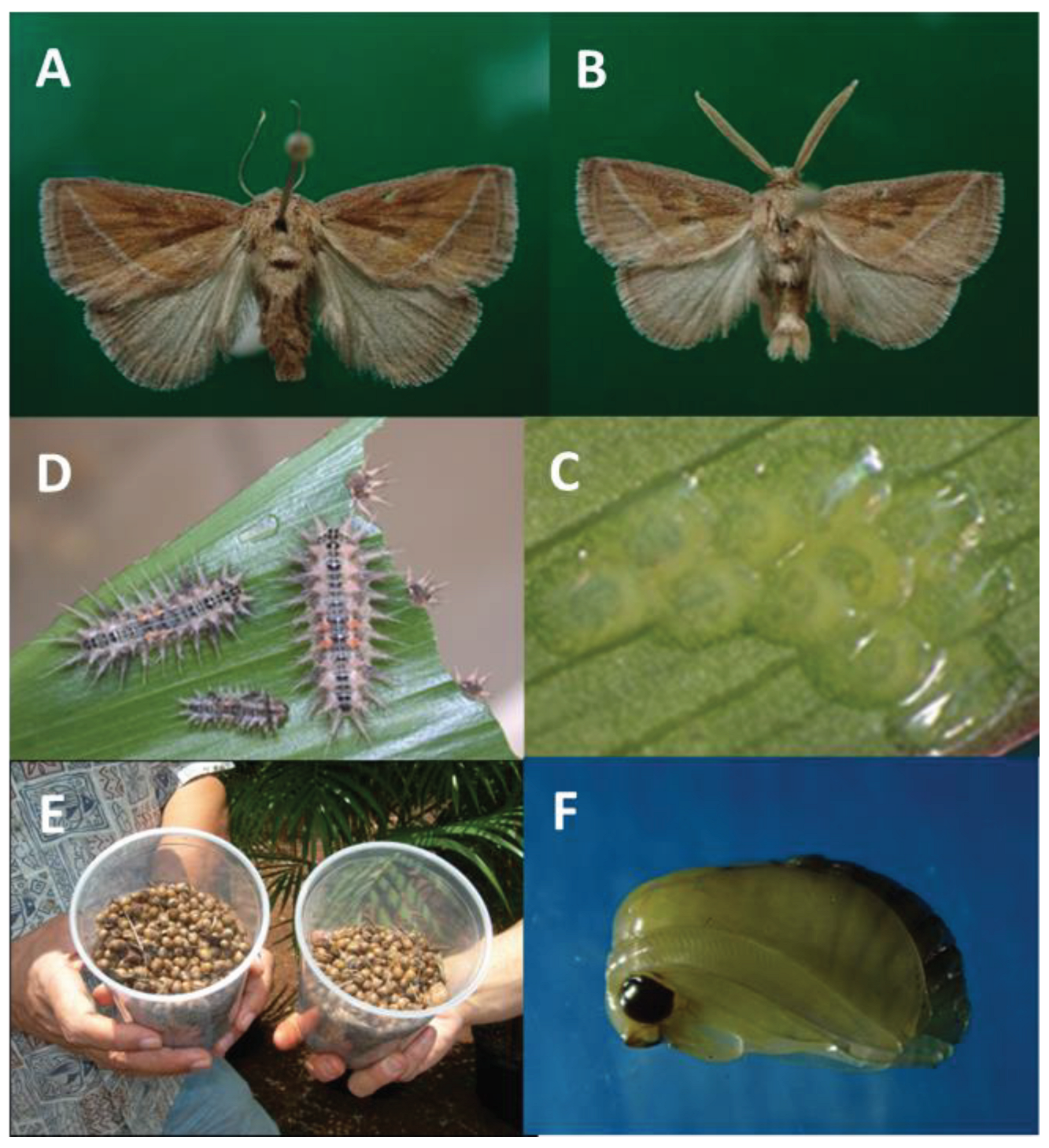

Figure 8.

Darna pallivittus: A) female habitus; B) male habitus see bipectinate antennae and end of abdomen; C) flat eggs (1.6 mm length); D) stinging larvae (L6 – L10); E) spherical cocoons collected from Oahu nursery in thousands in 2007 (6.5 mm Ø); F) male pupa removed from the cocoon.

Figure 8.

Darna pallivittus: A) female habitus; B) male habitus see bipectinate antennae and end of abdomen; C) flat eggs (1.6 mm length); D) stinging larvae (L6 – L10); E) spherical cocoons collected from Oahu nursery in thousands in 2007 (6.5 mm Ø); F) male pupa removed from the cocoon.

Table 1.

Non-target lepidopterous species used in host specificity tests for the parasitoid Aroplectrus dimerus.

Table 1.

Non-target lepidopterous species used in host specificity tests for the parasitoid Aroplectrus dimerus.

| Family of Lepidoptera |

Scientific and common name |

Status and source |

host plant

common and scientific name |

| Erebidae |

Podomachla apicalis (Walker)

a leaf-feeder |

Beneficial,

Lab-reared |

fireweed leaves,

Senecio madagascariensis |

| Erebidae |

Secusio extensa (Butler)

a leaf-feeder |

Beneficial

Lab-reared |

fireweed leaves,

Senecio madagascariensis

|

| Choreutidae |

Choreutis sp.

a leaf-tier |

Pest

Field-collected |

weeping fig leaves,

Ficus benjamina |

| Crambidae |

Diaphania nitidalis Cramer

pickleworm |

Pest

Lab-reared |

cucumber flowers/fruit,

Cucumis sativa, Pipturis albidus

|

| Crambidae |

Omiodes blackburni (Butler)

coconut leaf roller |

Endemic

Lab-reared |

coconut leaves,

Cocos nucifera |

| Crambidae |

Udea stellata (Butler)

a leaf-feeder |

Endemic

Lab-reared, |

mamaki leaves,

|

| Ethmiidae |

Ethmia nigroapicella (Sallmuller)

kou leafworm |

Pest

Field-collected |

kou leaves,

Cordia subcordata |

| Geometridae |

Anacamptodes fragilaria (Grossbeck),

koa haole looper |

Pest

Field-collected |

koa-haole leaves,

Leucaena leucocephala |

| Geometridae |

Macaria abydata Guenee

koa haole moth |

Pest

Field-collected, |

koa-haole leaves,

Leucaena leucocephala |

| Lycaenidae |

Lampides boeticus (Linnaeus)

bean butterfly |

Pest

Field-collected |

rattlepod beans,

Crotalaria sp. |

| Noctuidae |

Achaea janata (Linnaeus)

croton caterpillar |

Pest

Field-collected |

castor bean leaves,

Ricinus communis |

| Noctuidae |

Agrotis sp.

a cutworm |

Pest

Lab-reared

|

cotton leaves,

Gossypium hirsutum

|

| Noctuidae |

Anomis flava (Fabricius)

hibiscus caterpillar |

Pest

Lab-reared |

cotton leaves,

Gossypium hirsutum |

| Noctuidae |

Heliothis virescens (Fabricius)

tobacco budworm |

Pest

Field-collected |

love-in-a-mist flowers,

Passiflora foetida

|

| Noctuidae |

Pandesma anysa Guenee

a leaf-feeder |

Pest

Field-collected |

opiuma leaves,

Pithecellobium dulce |

| Noctuidae |

Spodoptera mauritia (Boisduval),

lawn armyworm |

Pest

Lab-reared |

undetermined grass species |

| Nymphalidae |

Agraulis vanillae (Linnaeus)

passion vine butterfly |

Pest

Field-collected |

passion vine leaves,

Passiflora edulis

|

| Nymphalidae |

Vanessa cardui (Linnaeus)

painted lady |

Pest

Field-collected |

cheeseweed leaves,

Malva parviflora

|

| Pieridae |

Pieris rapae (Linnaeus)

imported cabbageworm |

Pest

Field-collected |

broccoli leaves,

Brassica oleracea |

| Plutellidae |

Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus), diamondback moth |

Pest

Field-collected |

broccoli leaves,

Brassica oleracea |

| Pyralidae |

Hellula undalis (Fabricius)

imported cabbage webworm |

Pest

Field-collected |

mustard cabbage leaves,

Brassica juncea |

| Sphingidae |

Daphnis nerii (Linnaeus)

oleander hawk moth |

Pest

Field-collected |

oleander leaves,

Nerium oleander |

| Tortricidae |

Croesia zimmermani Clarke

a biocontrol agent |

Beneficial

Field-collected |

blackberry leaves,

Rubus argutus

|

| Tortricidae |

Cryptophlebia ombrodelta (Lower),

litchi fruit moth |

Pest

Field-collected |

undetermined legume species |

| Tortricidae |

Episimus utilis Zimmerman

a biocontrol agent |

Beneficial

Field-collected |

x-mas berry leaves,

Schinus terebinthifolius

|

Table 2.

Reproductive attributes, developmental rates of mated Aroplectrus dimerus females, and measurements of immatures. The data is shown for 40 replicates in which a female was fed honey and allowed to oviposit on Darna pallivitta larvae that were replaced every day.

Table 2.

Reproductive attributes, developmental rates of mated Aroplectrus dimerus females, and measurements of immatures. The data is shown for 40 replicates in which a female was fed honey and allowed to oviposit on Darna pallivitta larvae that were replaced every day.

| Reproductive parameter |

n |

Mean ± SEM |

Range |