1. Introduction

1.1. Distribution System Operators

Energy networks form the indispensable backbone through which our society transports energy. Distribution System Operators (DSOs) form the connecting link between the generation and consumption of energy by being responsible for operating and maintaining the energy networks. Managing the energy networks entails more than just the technical care of individual assets, such as transformers, power lines, and switchgear. Instead, Asset Management (AM) is about the purpose of the entire organization, the creation of lasting value for different stakeholders, collaboration, and dealing with long-term change and uncertainty [

1]. In fact, DSOs “plan and control the asset-related activities and their relationships to ensure the asset performance that meets the intended competitive strategy of the organization” [

2].

Whilst managing the energy networks, DSOs take into account relevant regimes (governance, geo-political, economic, social, demographic, and technological) [

3]. One of those currently relevant regimes is the energy transition, which provides a key challenge for DSOs since it requires important strategic technical decisions with long-lasting consequences [

4]. The energy transition is characterized by the shift toward renewable and more sustainable energy sources [

5], the liberalization of the energy sector, and changes in energy consumption patterns [

6]. Furthermore, a broad range of distributed energy resources is emerging, be it distributed generation, local storage, electric vehicles, and demand response [

7]. By maintaining, replacing, and extending the energy networks, DSOs facilitate the transition toward a more sustainable society.

1.2. Circular Action

The shift toward renewable and more sustainable energy sources is crucial for moving from a linear to a circular economy (CE) [

8]. The CE is especially relevant for DSOs since they “have a responsibility to uphold the environmental and sustainable values of society and must respond to a broad set of stakeholders” [

9]. Additionally, the AM of energy networks is resource intensive and therefore, there is a need to close material loops and embed sustainability into the AM practices itself [

10] rather than merely facilitating society becoming more sustainable. The activities of DSOs must therefore be systematically directed toward circularity and should take a life cycle perspective with the consideration of ecological and economic targets [

11].

The CE concept is trending among both scholars and professionals as it is increasingly treated as a solution to resource scarcity, environmental impact, and economic benefits [

12]. Despite sharing a common theme, there are over a hundred definitions of the CE in use in literature alone, proving that the “CE means many different things to different people”[

13]. Additionally, many efforts have been made to clarify the concept of CE, which include design rules, processes, frameworks, and roadmaps [

14,

15]. Several of these frameworks and philosophies have found widespread recognition outside academia such as the Cradle-to-cradle design [

16] and the Butterfly model [

17]. However, Saidani et al. conducted a systematic literature review of circularity indicators developed by scholars, consulting companies, and governmental agencies, stressing the need to translate CE indicators into implementable actions [

18].

1.3. Research Question/Aim

“Despite an increasing demand for considering sustainability aspects in AM, there is a lack of guidance for decision-makers on how this can be achieved”, especially with regard to identifying trade-offs between conflicting objectives (Niekamp et al., 2015). Seamlessly integrating sustainability into decision-making is a challenging task, since sustainability needs to be balanced with other criteria [

19] that are relevant to DSOs. Merli et al. indicate that “despite the interest of academia in the managerial implications of CE implementation, there emerges the absence of a shared framework on how CE should be applied to firms’ operations [

20] and how firms may adapt their business models to CE paradigm [

21]” [

22]. Moreover, there are many barriers to overcome when transitioning to a CE, such as an unclear distribution of responsibilities, sustainability perception, risk aversion, and integration in current processes [

23]. The current CE landscape is not only highly fragmented and granular, but it also rarely touches the implementation level [

12]. Therefore this research aims to understand empirical success factors for circular action and generate prescriptive knowledge on the operationalization of circularity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Description

Liander is the largest DSO in the Netherlands and its main objective is to distribute electricity and natural gas to its 5,9 million customers in a reliable, uninterrupted, and safe way, at the lowest societal costs. Liander manages and owns the electricity grids in its catchment area from low voltage to 150/110 kilovolt (kV) transformers. An important challenge for Liander lies in the energy transition. In 2022 alone, it spent approximately €1228 million on maintenance, replacement, and new construction of its energy infrastructure [

24]. Given Liander’s resource-intensive operations, the CE is a means for Liander to maximize the life cycle, value, and reusability of resources and minimize waste and energy consumption. Through circularity, Liander aims to responsibly operate its assets, such that these remain available, sustainable, and affordable, now and in the future.

Liander started working on circularity in 2014 through the introduction of internal training and a key performance indicator on circular procurement. Real circular change started when the idea to reuse distribution transformers won an internal innovation contest. Since then, the circularity of distribution transformers (from now on referred to as transformers) has grown into a mature and fully integrated circular project and is perceived as Liander’s most successful circularity project. Moreover, this circular project has grown into a team fully committed to the circularity of Liander’s asset portfolio. Therefore, this case was selected to research the operationalization of circularity in the energy sector.

2.2. Longitudinal Case Study

Case research is a powerful method since it offers a full understanding of the nature and complexity of a phenomenon [

27,

28]. Processes of organizational change often are lengthy and therefore a longitudinal case study was particularly useful for researching the developments in the operationalization of circularity over a longer period [

25,

26]. As recommended by Eisenhardt, a case was selected where the operationalization of circularity was successful and could be observed transparently [

29].

The starting point for the longitudinal case was the start of 2014 when Liander started working on circularity. Around that time, the third author of this paper started to collaborate with Liander on Asset Life Cycle Planning [

30]. In 2016, the second author of this paper joined the collaboration, which then shifted focus toward Life Cycle Valuation [

31]. Lastly, the first author of this paper joined in 2020, and the collaboration shifted focus toward the integration of sustainability in the field of AM of which this article is part. This researcher embeddedness allowed the identification of the circularity of transformers as a successful case and to retrospectively research it in detail over a longer period. As the circularity of transformers at Liander is still being optimized, the deadline for submitting this article was decisive for the endpoint of the longitudinal case (the end of 2023).

This research aims to develop prescriptive knowledge that contributes to the further operationalization of circularity, rather than merely describing a change process [

32]. Therefore, the Design Science Research approach of Denyer et al. was followed [

33], which aims to generate design propositions to solve improvement problems. CIMO logic was used to structure the findings, by identifying problematic contexts (C), applied interventions (I), triggered mechanisms (M), and generated outcomes (O). These CIMO-cycles were then translated into design propositions, which aim to generally prescribe how to operationalize circularity when managing energy networks.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

To study the longitudinal case, various types of data were collected from Liander’s intranet and Sharepoint, as summarized in

Table 1. Using a broad array of data from various organizational levels enabled the researchers to slice vertically through the organization and to study the case from multiple perspectives, as recommended by [

34]. Moreover, using different data sources and collection methods contributed to triangulating the evidence [

35].

In addition to Liander’s internal data, previously collected research data was used, such as daily journals of the researchers and previously conducted interview data. To analyze this large amount of retrospective data, a timeline was constructed of the longitudinal case, which marks the most important actions that positively or negatively affected the circularity of transformers. With the construction of this timeline, attention was paid to relevant trends in the organizational context [

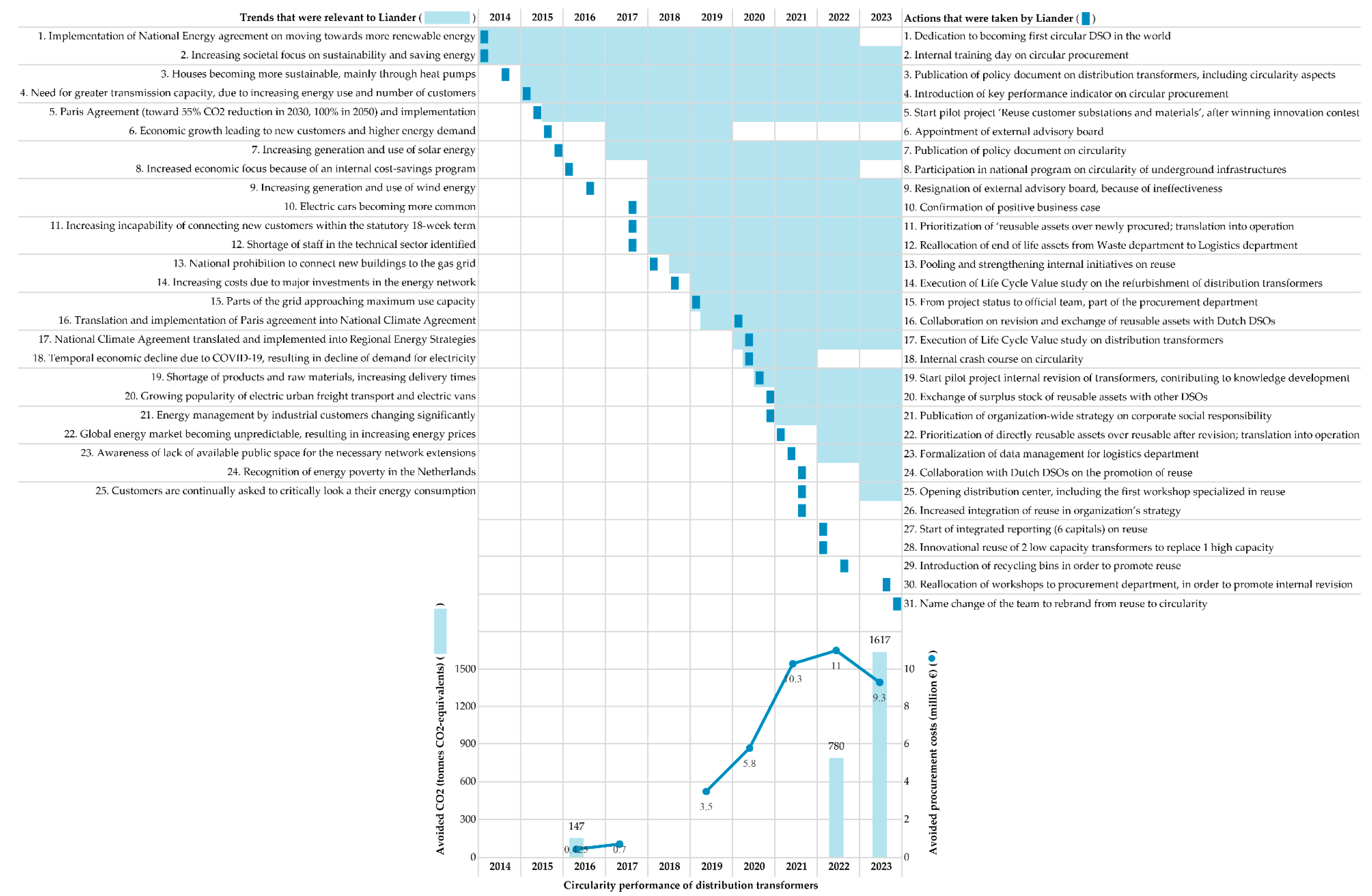

36] and the circular performance of Liander as a result of the actions.

Finally, six semi-structured interviews were conducted with the manager and two (former) members of the circularity team; a policy advisor from the Maintenance department and a supply chain consultant from the Logistics department, who both have/had an important advisory role in the circularity of transformers; and an innovation manager, who sponsored the change process. Hereby, the most knowledgeable members from various hierarchical levels were interviewed, as recommended by [

37,

38]. The interviews contributed to the generation of a rich and full understanding of the change process from the perspective of the people who initiated the most important events themselves, as recommended by [

34].

First of all, the interviews were used to complete and validate the constructed timeline. More importantly, the interviewees were asked what generally recurring interventions (I) were introduced in what problematic contexts (C), what mechanisms were triggered by these interventions, and what outcomes (O) were produced thanks to these interventions [

33]. Together, these contexts, interventions, mechanisms, and outcomes constitute multiple CIMO cycles, which were translated into design propositions. To generalize the findings, the design propositions were compared to literature.

3. Results

Transformers reach their end of life in case of failure or grid reinforcements. After taking it out of the energy grid, a transformer is measured in order to determine if it is reusable directly, and if so, the transformer is sent to Liander’s distribution center. If not, it is first sent to Liander’s revision partner, and then to the distribution center, where the Logistics department adds all incoming transformers to their stock. When the Operations department orders a transformer, the transformers that do not need any revision are first in line. If not available, a revised transformer is delivered. Only if these are not available either, a newly procured transformer is put into service. This whole process is governed by the Procurement department and executed within the technical frameworks provided by the Maintenance department.

This current reuse practice was built from scratch during the timespan of the longitudinal case. Despite the end of the longitudinal case, the operationalization of circularity at Liander still is an ongoing process. Liander is working toward increased circularity of other assets, such as cables and tools. Moreover, other sustainability aspects are getting increased attention now, such as the circularity team becoming a place for the reintegration of incapacitated employees and the retention of intellectual capital through internal revision of assets.

Figure 1 describes the most important actions in the longitudinal case, trends that were relevant to these actions, and the circular improvements caused by the actions. With the help of the interviewees, the wide variety of actions that were executed during the timespan of the longitudinal case could be summarized into six more general and recurrent interventions. These interventions and how they contributed to the successful operationalization of circularity in the longitudinal case will be further discussed below.

3.1. Intervention A: Initiate Small-Scale Circularity Experiments

Through the years, Liander has found her steady state in operating the energy grid. In order to initiate circular change, deviation from this steady state is required. However, employees often fear the risks involved with deviating, and it is very difficult to change the direction of a cumbersome organization like Liander all at once. Therefore, an important step was to initiate small-scale circularity experiments (e.g. actions 5, 19, and 28, see

Figure 1), without asking for permission first. Hereby the potential of circular initiatives was demonstrated, which most likely could not have been demonstrated if asked for permission first. Interviewees described this as acting like an entrepreneur and stated that it takes a lot of courage.

3.2. Intervention B: Involve Technical and Strategic Experts

According to the interviewees, it sometimes felt unsafe to contradict reputable colleagues. In order to deal with potential criticism, it was therefore important to collaborate with some professionals from the old guard. The expertise of technical colleagues contributed to finding circular solutions that fit the technical requirements of transformers. In addition to that, the expertise of strategic colleagues could ensure the right preconditions for the circular solutions, (e.g. through actions 3 and 7). By involving these credible experts, the circular solution became a shared initiative. This sponsorship, as the interviewees called it, provided ground for deviating from the established order and made it easier to convince others to cooperate.

3.3. Intervention C: Synergize Circularity with More Urgent, Primary Goals

Other business objectives (e.g. trends 10 and 13) were often prioritized over circularity which made it difficult to find scope for circular change. The development of a business case (e.g. action 10) was, therefore, an important step in advancing circularity, since it showed the synergies between circularity and more urgent primary goals. It allowed the initiators to provide a solution for at that time urgent challenges (e.g. trend 21). Even though the development of a business case required creativity and flexibility of the circularity team, especially given the rapidly changing environment, it contributed to pitching the circular initiatives and showing the urgency of actual implementation.

3.4. Intervention D: Translate Circular Initiatives Bottom-Up And Top-Down

Along the process, several initiatives were running in parallel, but a uniform approach was lacking. Formulating a shared definition of circularity (e.g. action 7) and setting key performance indicators (e.g. action 4) contributed to steering all initiatives toward the same objective. Setting and conveying standards on the prioritization between putting into service a reusable or a newly procured asset (e.g. action 11 and 22) contributed to reaching the objectives through a uniform approach. And in order to make sure that the objectives were reached and reported on, work instructions were developed, such that operations could be adjusted accordingly.

3.5. Intervention E: Collaborate with Other DSOs

In the beginning, it was very difficult to make an impact, because of a lack of scale and an inefficient way of working. In order to overcome these challenges, Liander collaborated with other DSOs on many levels: they jointly committed to becoming more circular, shared knowledge on how to overcome certain challenges, and jointly anticipated societal developments (e.g. action 8). In the later stages of the longitudinal case, collaboration facilitated the exchange of reusable assets in order to match supply and demand (e.g. actions 16 and 20). Additionally, operations were aligned and each DSO could create their area of expertise, while mutually outsourcing other areas. It also strengthened their leverage toward supply chain partners, for example during the procurement of circular assets.

3.6. Intervention F: Create Multi-Disciplinary Teams

During the scale-up of reusing transformers, the organizational structure was suboptimal for the newly adopted philosophy. Interviewees described the individual departments as ‘small kingdoms’ which all have their own way of working. Therefore, multidisciplinary teams were created (e.g. through action 13) and certain responsibilities were reallocated (e.g. actions 12, 15, 25, and 30). This all resulted in circularity becoming a shared philosophy that was propagated to and practiced by other parts of the organization as well. Despite these interventions, there is still some confusion sometimes about the distribution of responsibilities at Liander. However, the interventions already contributed to moving circular action forward.

4. Discussion

The interventions, described in the results section, were applied by the circularity team based on the contextual factors that were at play at that moment. By applying these interventions (I) in these specific contexts (C), certain mechanisms (M) were triggered, which in turn generated positive outcomes (O). Thereby, each of the discussed interventions was part of a full CIMO cycle. These CIMO cycles provide a better understanding of how and why these interventions contributed to operationalizing circularity and are presented in

Table 2. They will be further discussed, compared to literature, and translated into a generalizable design proposition below.

4.1 CIMO Cycle A: The Creation of a Precedent

Intervention A, initiating small-scale circularity experiments, allowed the initiators to demonstrate the potential of circularity and set examples for future circularity projects. In literature, experimentation is recognized to be crucial in initiating change, “as long as it is accomplished within an organization’s business context and strategic intent” [

39]. The experiments can prove that desirable outcomes can be generated [

40,

41] and moreover, in the context of Liander, the experiments often functioned as precedents: in case of doubt about scaling up the initiatives, the experiments could be relied upon and thereby they contributed to neutralizing criticism [

42]. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition A. In case of a risk-averse environment, initiate small-scale experiments in order to create a precedent and thereby demonstrate the potential of circularity.

4.2 CIMO Cycle B: The Creation of a Supporting Team

During the initiation of small-scale experiments, technical and strategic experts were involved in order to create a supporting team. Many authors recognize the importance of intervention B in similar situations: the implementation of Life Cycle Sustainability Management [

43], the implementation of Sustainability Impact Assessment [

44], and the governance of circular economies [

45]. Remarkably, the importance of the seniority and expertise of the involved experts was stressed in Liander’s case, since it was their credibility that contributed to convincing higher management in case of skepticism about circular change. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition B.

In case of fear of receiving criticism from higher management, involve technical and strategic experts in order to create a supporting team and thereby convince higher management to continue circular change.

4.3 CIMO Cycle C: Circularity as By-Catch to Core Business

By synergizing circularity with more urgent, primary goals, circularity no longer needed to compete with core business objectives. Other authors recognize the need to identify synergies, conflicts, and trade-offs across impacts on different levels [

44]. Considering the economic aspects of the initiatives was important since profit objectives significantly influence strategic decision-making [

46]. Thanks to intervention C, circularity became a by-catch to core business activities and sometimes even provided solutions for urgent matters that linear business activities could not address on time. Moreover, creating a sense of urgency is an important step for initiating change [

41]. Even though circularity would be given higher priority in an ideal world, utilizing the priority of primary goals contributed to increasing the incentive for circular change and thereby moving circularity forward, as demonstrated by Liander’s case. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition C. In case of other business objectives being prioritized over circularity, synergize circularity with more urgent, primary goals in order to reframe circularity as a by-catch to core business and thereby create an incentive for circular change.

4.4 CIMO Cycle D: Alignment of Strategy and Operations (Vertical Alignment)

As with usual AM activities, it was important to create alignment between the circular strategy and operations [

47], through intervention D. Hereby, all initiatives were steered toward the same objective, as recommended for change management processes [

41]. Gemechu et al. also recommend this vertical alignment [

43] and stress the importance of continuous improvement cycles in order to align strategy and operations both bottom-up and top-down depending on the needs at that moment. This continuous vertical alignment is sometimes referred to as the Line of Sight [

48]. Whatever name it is given, it contributed to creating a shared language, as recommended by [

49]. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition D. In case of fragmented circular initiatives without a uniform approach, translate circular initiatives bottom-up and top-down in order to vertically align strategy and operations and thereby remove barriers for organizing circular change.

4.5 CIMO Cycle E: Scaling Through Collaboration

Liander adopted a scaling-through-collaboration strategy through intervention E, which is a “feasible route to tackle the challenges inherent to scaling” [

50,

51,

52]. They collaborated with other DSOs on various functional levels, in order to chase mutual gains, as described by [

53]. Sharing knowledge in a collaborative network also appeared to be essential in a case study in Italy [

54]. In literature, collaboration through for example networks and platforms is regarded critical for transitioning toward a CE [

55,

56] and for enhancing organizational innovativeness in a CE [

57]. Overall, collaboration contributed to realizing economies of scale, with the associated benefits. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition E.

In case of a lack of scale, collaborate with other DSOs in order to scale through collaboration and thereby benefit from economies of scale.

4.6 CIMO Cycle F: Improved Coordination between Silos (Horizontal Alignment)

Intervention F, the creation of multidisciplinary teams was necessary since the interdisciplinary nature of a CE requires a diversity of actors with various missions and skills [

58]. Furthermore, all parts of the organization need to work together, to share and utilize information, to provide transparency, insight, and necessary answers [

59]. The multidisciplinary teams, also referred to as cross-functional teams, improved the coordination between silos by bringing together individuals from different departments. In literature, unclear distribution of responsibilities is described to be a barrier in the transition toward a CE [

23] and therefore, the assignment of responsibilities and accountabilities is crucial for the establishment of a cross-functional team [

60] and for circular action [

43]. All in all, intervention F contributed to the horizontal propagation and the practice of a circular philosophy throughout Liander. This leads to the following design proposition:

Design proposition F. In case of silo mentality, create multidisciplinary teams in order to improve coordination between silos and thereby horizontally propagate and manage circular practice.

5. Conclusions

DSOs have the responsibility to facilitate the transition toward a more sustainable society but this requires many resources. Therefore, they are increasingly expected to consider circularity principles in the AM of their energy networks. However, operationalizing circularity is perceived as a challenging task since there are many barriers, and current theory on CE is rarely translated into implementable actions.

A longitudinal case at Dutch DSO Liander showed that the success of circular action strongly depends on contextual factors, such as a risk-averse environment and other business objectives being prioritized over circularity. On top of that, various mechanisms were at play that were decisive (positively or negatively) for the success of Liander’s circular actions. Therefore, it was important for Liander to select the right circular interventions, based on the specific contextual factors at play at that moment, in order to achieve circularity targets. Additionally, repetition of circular interventions in case of recurring contextual factors, led to a steady increase of circularity, by continually building upon the outcomes of previous interventions.

The findings from the longitudinal case at Liander on successful circular interventions were reflected upon from a scientific perspective. This led to the formulation of generalizable design propositions that could be used by other DSOs. These propositions could assist them in selecting the right circular interventions, depending on changing contextual factors and thereby optimizing their strategy toward circular action. This is particularly relevant for achieving circular targets in the context of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

Future research on empirical success factors at other organizations is necessary to gain a better understanding of design propositions for other contexts and sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H., W.H. and J.B.; methodology, H.H., W.H. and J.B.; validation, H.H., W.H. and J.B.; formal analysis, H.H.; investigation, H.H.; resources, H.H. and W.H.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and J.B..; visualization, H.H.; supervision, W.H. and J.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by LIANDER NV and HOLLAND HIGH TECH with PPP bonus for research and development in the top sector HTSM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to sincerely thank Liander for providing the necessary data for the longitudinal case and their employees for participating in the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

-

ISO/TC 251; Asset Management - Managing Assets in the Context of Asset Management. 2017.

- El-akruti, K.; Dwight, R.; Zhang, T.; Al-marsumi, M. Faculty of Engineering and Information Sciences The Role of Life Cycle Cost in Engineering Asset Management. In Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Engineering Asset Management and Safety; 2013; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pudney, S. Asset Renewal Desicion Modelling with Application to the Water Utility Industry, Queensland University of technology, 2010.

- Förster, O.; Zdrallek, M. Efficient Decision Making Supported by ISO 55000. CIRED - Open Access Proceedings Journal 2017, 2017, 2711–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J. The next Phase of the Energy Transition and Its Implications for Research and Policy. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbong, G.; Geels, F. The Ongoing Energy Transition: Lessons from a Socio-Technical, Multi-Level Analysis of the Dutch Electricity System (1960-2004). Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruester, S.; Schwenen, S.; Batlle, C.; Pérez-Arriaga, I. From Distribution Networks to Smart Distribution Systems: Rethinking the Regulation of European Electricity DSOs. Util. Policy 2014, 31, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, W.; Krausmann, F.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Heinz, M. How Circular Is the Global Economy? An Assessment of Material Flows, Waste Production, and Recycling in the European Union and the World in 2005. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, T.; Wincent, J.; Parida, V. A Definition and Theoretical Review of the Circular Economy, Value Creation, and Sustainable Business Models: Where Are We Now and Where Should Research Move in the Future? Sustain. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, D.R.; Beale, D.J.; Burn, S. A Pathway to a More Sustainable Water Sector: Sustainability-Based Asset Management. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; Götze, U.; Henriques, E.; Ribeiro, I.; Schmidt, A.; Symmank, C. Life Cycle Engineering - Taxonomy and State-of-the-Art. Procedia CIRP 2016, 48, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards Circular Economy Implementation: A Comprehensive Review in Context of Manufacturing Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovea, M.D.; Pérez-Belis, V. Identifying Design Guidelines to Meet the Circular Economy Principles: A Case Study on Electric and Electronic Equipment. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 228, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.; De los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A Conceptual Framework for Circular Design. Sustain. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; Rodale Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Transitioning to a Circular Economy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F.; Kendall, A. A Taxonomy of Circular Economy Indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskä, E.; Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J. Game-Based Learning in Project Sustainability Management Education. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V. Towards a New Taxonomy of Circular Economy Business Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How Do Scholars Approach the Circular Economy? A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzén, S.; Sandström, G.Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy – Integration of Perspectives and Domains. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V., 2017; Vol. 64; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

-

Alliander Annual Report 2022; 2023.

- Barley, S.R. Images of Imaging: Notes on Doing Longitudinal Field Work. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H. An Assessment of Perspectives on Strategic Change. In Perspectives on Strategic Change; Kluwer Academic Press.: Dordrecht, 1993; pp. 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Benbasat, I.; Goldstein, D.K.; Mead, M. The Case Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; 2nd [rev.].; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA SE - XVII, 171 p. : illustrations ; 23 cm, 1994; ISBN 9781412960991. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research Published by : Academy of Management Stable, 1989, Vol. 14.

- Ruitenburg, R.J.; Braaksma, J.J.J.; Van Dongen, L.A.M. Asset Life Cycle Plans: Twelve Steps to Assist Strategic Decision-Making in Asset Life Cycle Management. In Optimum Decision Making in Asset Management; 2017; pp. 259–287. ISBN 9781522506522. [Google Scholar]

- Haanstra, W.; Braaksma, A.J.J.; van Dongen, L.A.M. Designing a Hybrid Methodology for the Life Cycle Valuation of Capital Goods. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestrini, V.; Luzzini, D.; Shani, A.B.; Canterino, F. The Action Research Cycle Reloaded: Conducting Action Research across Buyer-Supplier Relationships. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D.; Van Aken, J.E. Developing Design Propositions through Research Synthesis. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-barton, D. A Dual Methodology for Case Studies: Synergistic Use of a Longitudinal Single Site with Replicated Multiple Sites. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jick, T.D. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Contextualist Research and the Study of Organizational Change Processes. In Doing Research That is Useful for Theory and Practice; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 1985; pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maanen, J. The Fact of Fiction in Organizational Ethnography. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. The Clinical Perspective in Fieldwork; Sage Publications: Newbury park, CA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber, K. Rethinking Organizational Change: Reframing the Challenge of Change Management. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 23, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R.; Heisler, W.; Creary, W.M.C. Leading Change with the 5-P Model “Complexing” the Swan and Dolphin Hotels at Walt Disney World. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change - Why Transformation Efforts Fail; ECON: Dusseldorf, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P..; Darius, B. Chaos, Wandel, Führung - Leading Change; ËCON: Dusseldorf, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gemechu, E.D.; Sonnemann, G.; Remmen, A.; Frydendal, J.; Jensen, A.A. How to Implement Life Cycle Management in Business? In Life Cycle Management; 2015; pp. 35–50. ISBN 9789401772211. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Guidance on Sustainability Impact Assessment; 2010.

- Cramer, J. Effective Governance of Circular Economies: An International Comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komonen, K.; Kortelainen, H.; Räikkönen, M. Corporate Asset Management for Industrial Companies: An Integrated Business-Driven Approach. In Asset Management The State of the Art in Europe from a Life Cycle Perspective Foreword; Springer: Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York, 2012; pp. 47–64. ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 55000 Asset Management - Overview, Principles and Terminology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.K.; Mcmann, O.; Borthwick, F. Challenges and Prospects of Applying Asset Management Principles to Highway Maintenance: A Case Study of the UK. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 97, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.; Mieras, E.; Gaasbeek, A.; Contreras, S. How to Make the Life Cycle Assessment Team a Business Partner Introduction. In Life Cycle Management; 2015; pp. 105–115. ISBN 9789401772211. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulli, F.; Kolk, A.; Bidmon, C.M.; Sprong, N.; Hekkert, M.P. Sustainable Business Model Innovation and Scaling through Collaboration. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2022, 45, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Waes, A.; Farla, J.; Frenken, K.; de Jong, J.P.J.; Raven, R. Business Model Innovation and Socio-Technical Transitions. A New Prospective Framework with an Application to Bike Sharing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1300–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.N.; Chatterji, A.K.; Bloom, P.N.; Chatterji, A.K. Scaling Social Entrepreneurial Impact. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2009, 51, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisbett, E.; Raynal, W.; Steinhauser, R.; Jones, B. International Green Economy Collaborations: Chasing Mutual Gains in the Energy Transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Moggi, S.; Campedelli, B. Spreading Sustainability Innovation through the Co-Evolution of Sustainable Business Models and Partnerships. Sustain. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox-alcantar, P.G.; Hunt, D.V.L.; Rogers, C.D.F. Current and Future Professional Insights on Cooperation towards Circular Economy Adoption. Sustain. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsova, S.; Genovese, A.; Ketikidis, P.H.; Alberich, J.P.; Solomon, A. Implementing Regional Circular Economy Policies: A Proposed Living Constellation of Stakeholders. Sustain. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z.; Mihai, D.; Tanveer, U. Organizational Innovativeness in the Circular Economy: The Interplay of Innovation Networks, Frugal Innovation, and Organizational Readiness. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, R.; Aublet, A.; Laurenceau, S.; Habert, G. Challenges and Opportunities for Circular Economy Promotion in the Building Sector. Sustain. 2022, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 55010: Asset Management - Guidance on the Alignment of Financial and Non-Financial Functions in Asset Management; 2019; Vol. 55010. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough III, E.F. Investigation of Factors Contributing to the Success of Cross-Functional Teams. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2000, 17, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).