Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collaborative Optimal Dispatch of Power Systems

2.2. DEMATEL Method for Complex Systems

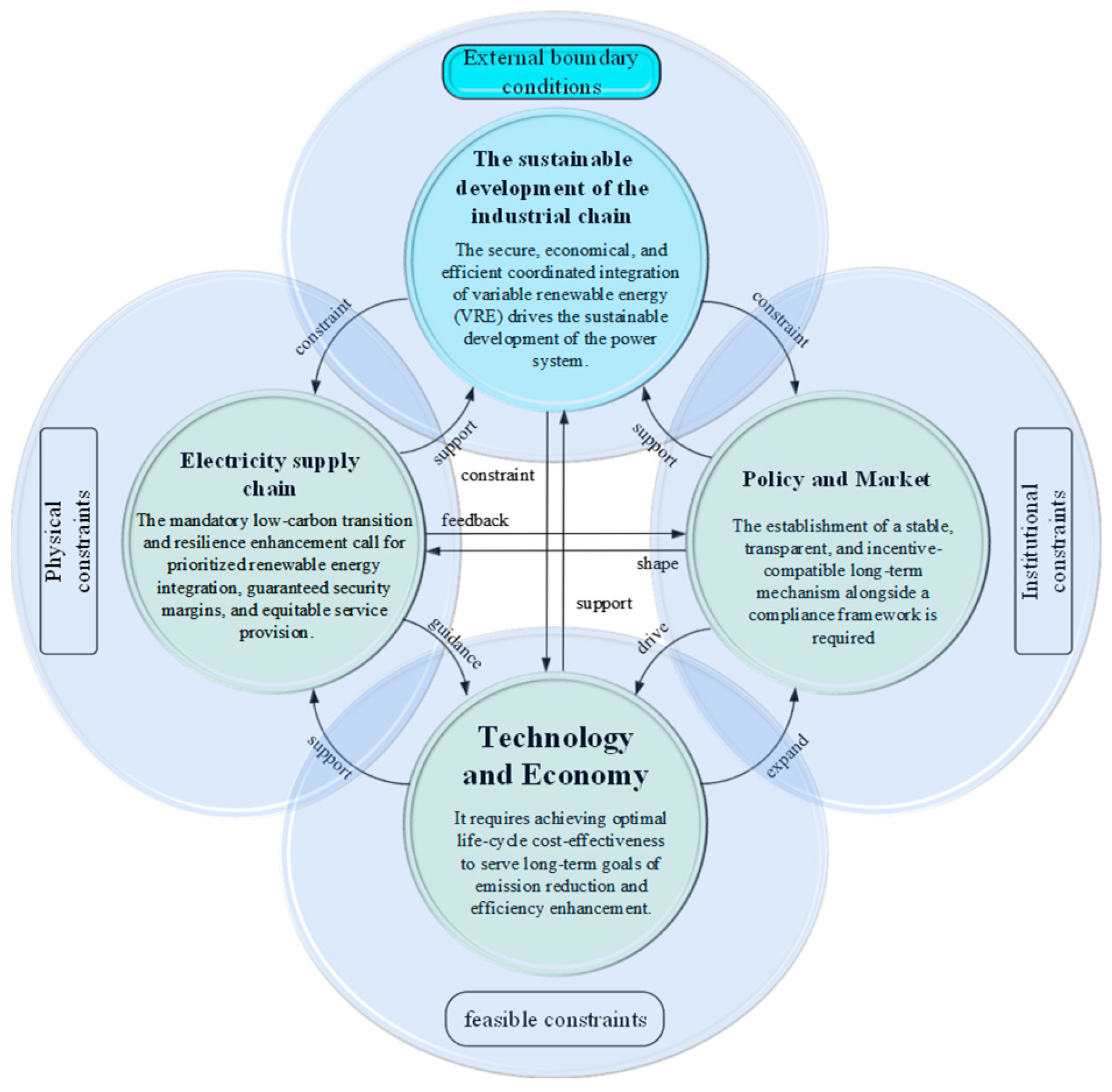

3. Preliminary Identification of Constraints

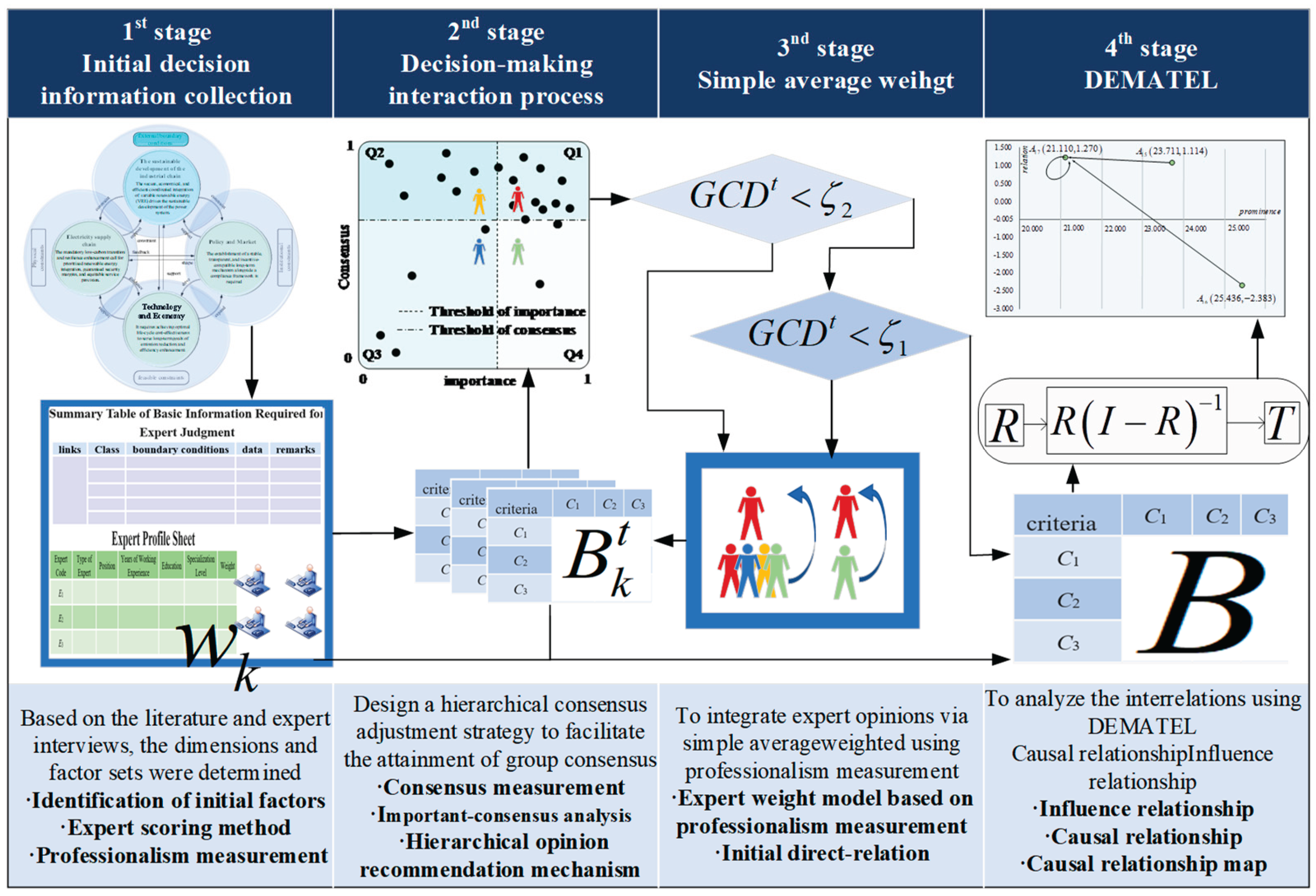

4. Analysis of Key Constraining Factors for Power Load Control Based on a Novel Interactive Group DEMATEL Method

4.1. Expert Weighting Model Based on Quantitative Assessment of Professional Competence

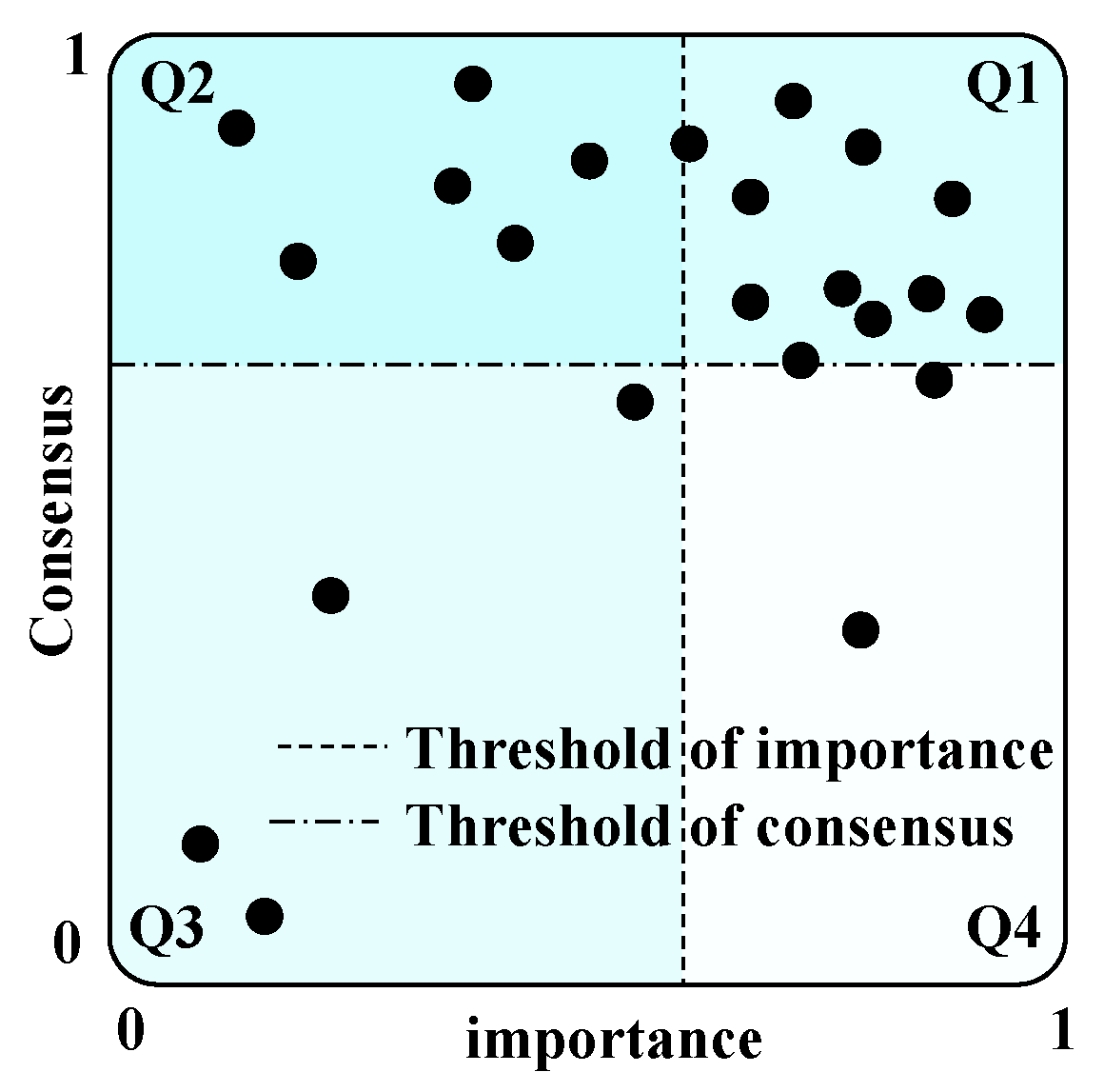

4.2. Expert Consensus Measurement

4.3. Hierarchical Consensus Adjustment Strategy

4.4. Key Constraining Factors Analysis Method for Power Grid Load Control from the Perspective of Industrial Chain Sustainable Development

5. Case Study

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Sardans, J.; Hauglustaine, D.; Liu, W.; Xing, X.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, R.; Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Tang, X.; Zhang, R. Accelerating the Energy Transition towards Photovoltaic and Wind in China. Nature 2023, 619, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hui, H.; Wang, S.; Song, Y. Coordinated Optimization of Power-Communication Coupling Networks for Dispatching Large-Scale Flexible Loads to Provide Operating Reserve. Appl. Energ. 2024, 359, 122705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Shan, X.; Yan, Y.; Leng, X.; Wang, Y. Architecture, Key Technologies and Applications of Load Dispatching in China Power Grid. Mod. Power Syst. and Cle. 2022, 10, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Yan, X.; Tong, D.; Davis, S.; Caldeira, K.; Lin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Ping, L.; Feng, S. L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Chen, D.; He, K.; Zhang, Q. Strategies for Climate-Resilient Global Wind and Solar Power Systems. Nature, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09266-7. 2025; 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Muzhikyan, A.; Farid, A.M.; Youcef-Toumi, K. Demand Side Management in Power Grid Enterprise Control: A Comparison of Industrial & Social Welfare Approaches. Appl. Energ. 2017, 187, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsopoulos, I.; Tassiulas, L. Challenges in Demand Load Control for the Smart Grid. IEEE Netw. 2011, 25, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhai, H.; Wu, X. Research and Application of Multi-Energy Coordinated Control of Generation, Network, Load and Storage. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2021, 36, 3264–3271. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishan, W. Optimized Model of Energy Industry Chain Considering Low-Carbon Development Mechanism. Energ. Source. Part A 2020, 42, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitt, J.R. Implementation of A Large-Scale Direct Load Control System-Some Critical Factors. IEEE Trans. Powe App. Syst. 2007(7), 1663–1669. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, X.; Dou, Z.; Liu, L. A New Medium and Long-Term Power Load Forecasting Method Considering Policy Factors. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 160021–160034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Ming, Zhou, M. ; Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Coordination of Preventive and Emergency Dispatch in Renewable Energy Integrated Power Systems under Extreme Weather. Iet. Renew. Power Gen. 2024, 18, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Miri, M.; McPherson, M. Demand Response Programs: Comparing Price Signals and Direct Load Control. Energy 2024, 288, 129673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, W.; Almutairi, A. Planning Flexibility with Non-Deferrable Loads Considering Distribution Grid Limitations. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 25140–25147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chang, C.Y.; Bernstein, A.; Zhao, C.; Chen, L. Economic Dispatch with Distributed Energy Resources: Co-Optimization of Transmission and Distribution Systems. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2020, 5, 1994–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Liao, J.C.; Zhang, Y.M.; Huang, Y.C. Optimal Economic Dispatch and Power Generation for Microgrid Using Novel Lagrange Multipliers-Based Method with HIL Verification. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 4533–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, W.; Almutairi, A. Planning Flexibility with Non-Deferrable Loads Considering Distribution Grid Limitations. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 25140–25147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, F.; Abdelfatah, A. Economic Dispatch Optimization Strategies and Problem Formulation: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2024, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I. K.; Rahman, I.U.; Zakarya, M.; Zia, A.; Khan, A.A.; Qazani, M.R.C.; AI-Bahri, M.; Haleem, M. A Multi-Objective Optimisation Approach with Improved Pareto-Optimal Solutions to Enhance Economic and Environmental Dispatch in Power Systems. Sci. Rep-Uk. 2024, 14, 13418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Li, J.; He, X.; Huang, T. A Survey on Distributed Optimisation Approaches and Applications in Smart Grids. J. Control Decis. 2019, 6, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Lai, L. A Multi-Timescale Coordinated Optimization Framework for Economic Dispatch of Micro-Energy Grid Considering Prediction Error. IEEE T. Power Syst. 2023, 39, 3211–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H. Optimal Coordinated Operation for A Distribution Network with Virtual Power Plants Considering Load Shaing. IEEE T. Sustain. Energ. 2022, 14, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Chung, C.Y.; Ju, P.; Gong, Y. A Multi-Timescale Allocation Algorithm of Energy and Power for Demand Response in Smart Grids: A Stackelberg Game Approach. IEEE T. Sustain. Energ. 2022, 13, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wen, G.; Wang, S.; Fu, J.; Yu, W. Distributed Multiagent Reinforcement Learning with Action Networks for Dynamic Economic Dispatch. IEEE T. Neur. Net. Lear. 2023, 35, 9553–9564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khattak, A.U.; Khan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Ullah, Z.; Mehmood, F. Intelligent Renewable Energy Agent-Based Distributed Control Design for Frequency Regulation and Economic Dispatch. Int. T. Electr. Energy 2024, 2024, 5851912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xu, B.; Zhang, W.A.; Wen, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, L. Training Deep Neural Network for Optimal Power Allocation in Islanded Microgrid Systems: A distributed learning-based approach. IEEE T. Neur. Net. Lear. 2021, 33, 2057–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Rauniyar, A.; Hu, J.; Singh, A.K.; Chandra, S.S. Modeling Barriers to the Adoption of Metaverse in the Construction Industry: An Application of Fuzzy-DEMATEL Approach. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2024, 167, 112180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H. W.; Lin, S.W. Bottom-Up Green Manufacturing Strategy in the Wire and Cable Industry: A Z-DEMATEL Approach for Identifying Critical Success Criteria. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 44, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Fan, S; Li, H. ; Jones, G.; Yang, Z. Navigating Uncertainty: A Novel Framework for Assessing Barriers to Blockchain Adoption in Freeport Operations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayson, M.; Bai, C.; Sarkis, J.; Hossin, M.A. Evaluating Barriers to Blockchain Technology for Sustainable A Supply Chain: A Fuzzy Hierarchical Group DEMATEL Approach. Oper. Manage. Res. 2024, 17, 728–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakshi, A.; Deepti, A. Performance Evaluation of Sustainable Downstream Logistics: A Hybrid Multi Criteria Decision Making Framework. SN Oper. Res. Forum 2024, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, D.S.; Garshasbi, M.; Kabir, G.; Bari, A.; Ali, S.M. Evaluating Interaction Between Internal Hospital Supply Chain Performance Indicators: A Rough-DEMATEL-Based Approach. Int. J. product. Perfor. 2022, 71, 2087–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Jayant, A.; Singh, K.; Kumar, N. Implementation of Low Carbon Supply Chain Management Practices (LCSCMP) in Indian Manufacturing Industries Using ISM-DEMATEL. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 23, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S.; Eti, S.; Dinçer, H.; Gokalp, Y.; Olaru, G.O.; Oflaz, N.K. Innovative Financial Solutions for Sustainable Investments Using Artificial Intelligence-Based Hybrid Fuzzy Decision-Making Approach in Carbon Capture Technologies. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, H. Factors Influencing Contractors Low-Carbon Construction Behaviors in China: A LDA-DEMATEL-ISM Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2024, 31, 49040–49058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.H.; Huang, J.Y.; Zhong, Q.W.; Zhu, D.W.; Dai, Y. Risk Evaluation for Human Factors of Flight Dispatcher Based on the Hesitant Fuzzy TOPSIS-DEMATEL-ISM Approach: A Case Study in Sichuan Airlines. Int. J. Comput. Int. Sys. 2024, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liang, Z.; Lang, X.; Shi, M.; Qiao, J.; Wei, J.; Dai, H.; Kang, J. A Risk Assessment Method Based on DEMATEL-STPA and Its Application in Safety Risk Evaluation of Hydrogen Refueling Stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024, 50, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.S.; Torabi, S.A.; Tavana, M. An Assessment of the Prominence and Total Engagement Metrics for Ranking Interdependent Attributes in DEMATEL and WINGS. Omega 2025, 130, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Q.; Yu, N.; Guan, M.; Tian, Z.; Huang, J. Management of Products in the Apparel Manufacturing Industry Using DEMATEL-Based Analytical Network Process Technique. Oper. Manage. Res. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Gu, Z.; Chang, F. A Novel Integration Strategy for Uncertain Knowledge in Group Decision-Making with Artificial Opinions: A DSFIT-SOA-DEMATEL Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Huang, Z.H.; Chi, F.D. Analysis of Systemic Factors Affecting Carbon Reduction in Chinese Energy-Intensive Industries: A Dural-Driven DEMATEL Model. Energy 2023, 285, 129319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Ren, J. Distributed Energy System for Sustainability Transition: A Comprehensive Assessment Under Uncertainties Based on Interval Multi-Criteria Decision Making Method by Coupling Interval DEMATEL and Interval VIKOR. Energy 2019, 169, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Zarei, E.; Ansari, M.; Nojoumi, A.; Yarahmadi, R. A System Theory Based AccidentAnalysis Model: STAMP-Fuzzy DEMATEL. Safety Sci. 2024, 173, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, K.; Yao, X.; Li, J. A Method for the Core Accident Chain Based on Fuzzy-DEMATEL-ISM: An Application to Aluminium Production Explosion. J. Loss. Prevent. Proc. 2024, 92, 105414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, T.; Gkritza, K. Examining the Barriers to Electric Truck Adoption as a System: A Grey-DEMATEL Approach. Transp. Res. Interdisc. 2023, 17, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Mao, W.; Dang, Y.; Xu, Y. Optimum Path for Overcoming Barriers of Green Construction Supply Chain Management: A Grey Possibility DEMATEL-NK Approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 164, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, S.; Hsieh, M.; Lin, C.; Tzeng, G. Improving The Poverty-Alleviating Effects of Bed and Breakfast Tourism Using Z-DEMATEL. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 25, 1907–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.C.J.; Liou, J.J.H.; Lo, H.W. A Group Decision-Making Approach for Exploring Trends in the Development of the Healthcare Industry in Taiwan. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 141, 113447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, Z.; Wei, C.; Bai, Q.; Liu, J. A Novel PROMETHEE Method Based on GRA-DEMATEL for PLTSs and Its Application in Selecting Renewable Energies. Inform. Sciences 2022, 589, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Erdebilli, B.; Naji, M.A.; Mousrij, A. A Fuzzy DEMATEL Framework for MaintenancePerformance Improvement: A Case of Moroccan Chemical Industry. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, M.; Liu, J. Analysis of Factors Influencing MOOC Quality Based on I-DEMATEL-ISM Method. Systems and Soft Computing 2025, 7, 200220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.R.; Pandiammal, P.; Nivetha, M. Decision Making on Synthesizing Nanoparticles Using Pythagorean New DEMATEL Approach. Mater. Today 2023, 80, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S.; Ecer, F.; Krishankumar, R.; Dincer, H.; Gökalp, Y. TRIZ-Driven Assessment of Sector-Wise Investment Decisions in Renewable Energy Projects Through a Novel Integrated Q-ROF-DEMATEL-SRP Model. Energy 2025, 314, 133970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadlou, M.; Khoshsepehr, Z. The Role of Society 5.0 in Achieving Sustainable Development: A Spherical Fuzzy Set Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 47630–47654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğdu, E.; Güner, E.; Aldemir, B.; Aygün, H. Complex Spherical Fuzzy TOPSIS Based on Entropy. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetanat, A.; Tayebi, M. Sustainability Prioritization of Technologies for Cleaning Up Soils Polluted with Oil and Petroleum Products: A Decision Support System Under Complex Spherical Fuzzy Environment. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Q.H. Analyzing Barriers for Adopting Sustainable Online Consumption: A Rough Hierarchical DEMATEL Method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 140, 106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, B. Integrated Planning and Operation Dispatching of Source–Grid–Load–Storage in a New Power System: A Coupled Socio–cyber–Physical Perspective. Energies 2024, 17, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J. Research on Short-Term Load Forecasting of New-Type Power System based on GCN-LSTM Considering Multiple Influencing Factors. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedam, V.V.; Raut, R.D.; Priyadarshinee, P.; Chirra, S.; Pathak, P. Analysing the Adoption Barriers for Sustainability in the Indian Power Sector by DEMATEL Approach. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, F. Identification of Key Influencing Factors to Chinese Coal Power Enterprises Transition in the Context of Carbon Neutrality: A Modified Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. Energy 2023, 263, 125427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Gong, X.; Han, B.; Zhao, X. Carbon-Neutral Potential Analysis of Urban Power Grid: A Multi-Stage Decision Model based on RF-DEMATEL and RF-MARCOS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 234, 121026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Xu, S.; Lin, C. Allocating Cost of Uncertainties from Renewable Generation in Stochastic Electricity Market: General Mechanism and Analytical Solution. IEEE T. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 4224–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Qin, X.; Qin, X.; Ding, B. Power System Flexibility Indicators Considering Reliability in Electric Power System with High-Penetration New Energy. ICPEA. 2022, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pu, H.; Li, T. Knowledge Mapping and Evolutionary Analysis of Energy Storage Resource Management Under Renewable Energy Uncertainty: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 121394318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Chen, X.; Yang, A.; Zhu, K. Enhancing Renewable Energy Integration via Robust Multi-Energy Dispatch: A Wind–PV–Hydrogen Storage Case Study with Spatiotemporal Uncertainty Quantification. Energies 2025, 18, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, F.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y. Research and Application of Electricity Substitution Indicators in Industrial Parks. IAEAC 2024, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlela, N.W.; Moloi, K.; Kabeya, M. Comprehensive Analysis of Approaches for Transmission Network Expansion Planning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 195778–195815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkop, E. A Survey on Direct Load Control Technologies in the Smart Grid. IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 4997–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; She, B.; Bao, Z. A General Simplification and Acceleration Method for Distribution System Optimization Problems. Prot. Contr. Mod. Pow. 2025, 10, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Qin, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, W. Review of Research on Evaluation Index System of Integrated Energy System in Low-Carbon Park. IAECST. 2023, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Ghaffarzadeh, N.; Shahnia, F. Optimal Scheduling of Demand Response-Based AC OPF by Smart Power Grid’ Flexible Loads Considering User Convenience, LSTM-Based Load Forecasting, and DERs Uncertainties. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 171617–171633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Baek, K.; Kim, J. Customer Targeting for Load Flexibility via Resident Behavior Segmentation. IEEE T. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Liu, C.; Huang, X. Analytical Dynamic Energy-Carbon Flow Model and Application in Cost Allocation for Integrated Energy Systems. IEEE T. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 2681–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlík, M.; Kurimský, F.; Ševc, K. Renewable Energy and Price Stability: An Analysis of Volatility and Market Shifts in the European Electricity Sector. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmad, Z.K.; Amin, U.; Ijaz, H.U. Efficient Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Effective Energy Management. Sustain. Energy Techn. 2022, 53, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.Y.; Lai, C.C. Toward Improved Load Forecasting in Smart Grids: A Robust Deep Ensemble Learning Framework. IEEE T. Smart. Grid 2024, 15, 4292–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, K.P.; Ramachandaramurthy, K.V.; Kasinathan, P.; Yong, J.Y.; Pasupuleti, J.; Rajagopalan, A. Application and Assessment of Internet of Things Toward the Sustainability of Energy Systems: Challenges and Issues. Sustain. Cities. Soc. 2020, 53, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.; Rabiee, M.; Tarei, P.K.; Coles, P.S. A Diverse, Unbiased Group Decision-Making Framework for Assessing Drivers of the Circular Economy and Resilience in an Agri-Food Supply Chain. Prod. Plan. Control. 2025, 36, 1453–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, Y. Maximum Satisfaction Consensus with Budget Constraints Considering Individual Tolerance and Compromise Limit Behaviors. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Tu, Y.; Martínez, L. Minimum Cost Consensus Model with Altruistic Preference. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 179, 109229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Criteria & Elements | Notes |

|

Power Supply Chain Sources: [62-73] |

Generation Side | |

| Power generation costs | Marginal cost or levelized cost of energy after accounting for system balance and flexibility, with system costs becoming significant under high renewable energy penetration. | |

| Flexibility of conventional energy sources | The ability of conventional generation units to adjust their output to accommodate renewable energy fluctuations is crucial for enhancing system regulation capacity. | |

| Application of energy storage technologies | The technology of storing electrical energy through batteries and other means to mitigate fluctuations and achieve peak shaving and valley filling, with key parameters including capacity and response speed. | |

| Renewable energy volatility | The unpredictability and instability of renewable energy output (such as wind and solar) affect grid balance and regulation requirements. | |

| Clean energy supply proportion | The proportion of renewable energy in total electricity generation is a core indicator of the low-carbon transition in the power sector. | |

| Transmission and Distribution Side | ||

| Maximum transmission capacity of transmission lines | The maximum power that can be transmitted by a transmission line under safe and stable conditions affects the renewable energy integration capacity. | |

| Level of grid intelligence | The capability of utilizing sensing, communication, and AI technologies to achieve grid condition awareness and optimized operation serves as the foundation for precise control. | |

| Distribution equipment capacity | The rated capacity of distribution facilities; integration of distributed energy resources may cause local overloads, necessitating capacity expansion and upgrades. | |

| Energy utilization rate | The ratio of actual transmitted power to rated capacity; improving the utilization rate requires balancing reliability and flexibility. | |

| User Side | ||

| Demand response mechanisms | Guiding electricity consumers to adjust their usage patterns through pricing or incentive mechanisms, thereby tapping into the flexibility resources on the demand side. | |

| User behavior characteristics | User electricity consumption habits, price sensitivity, and participation willingness affect load forecasting accuracy and response effectiveness. | |

| Policy and Market Factors Sources: [74] |

Electricity Pricing Policy | Government-established electricity pricing rules influence power generation revenue, consumer behavior, and the competitiveness of renewable energy. |

| Electricity Market Reform | It refers to the process of reforming the traditional vertically integrated power industry structure by introducing competition mechanisms and establishing wholesale (e.g., spot markets, medium-to-long-term markets) and retail markets. | |

| Government Regulatory Intensity | The intensity of government supervision and management of the electricity market ensures fair competition and reliable system operation. | |

| Technology and Economics Sources: [75-77] |

Load Forecasting Accuracy | The accuracy of future electricity demand forecasting affects system dispatch and renewable energy integration. |

| Multi-Energy Complementary Synergistic Benefits | Quantifying the synergistic optimization potential of power-heat-hydrogen-storage systems, enhancing renewable energy integration efficiency and long-term economic viability through multi-energy complementary conversion. | |

| Equipment Whole-Life-Cycle Cost | Encompassing the total economic investment throughout the entire lifecycle of key grid equipment (such as transformers, energy storage systems), from procurement and installation to decommissioning and recycling, it serves as a core evaluation metric for avoiding short-term behavior and ensuring long-term sustainability. |

| Linguistic Term Set | Evaluation Value |

| No Influence | 0 |

| Relatively Low Influence | 1 |

| Low Influence | 2 |

| High Influence | 3 |

| Relatively High Influence | 4 |

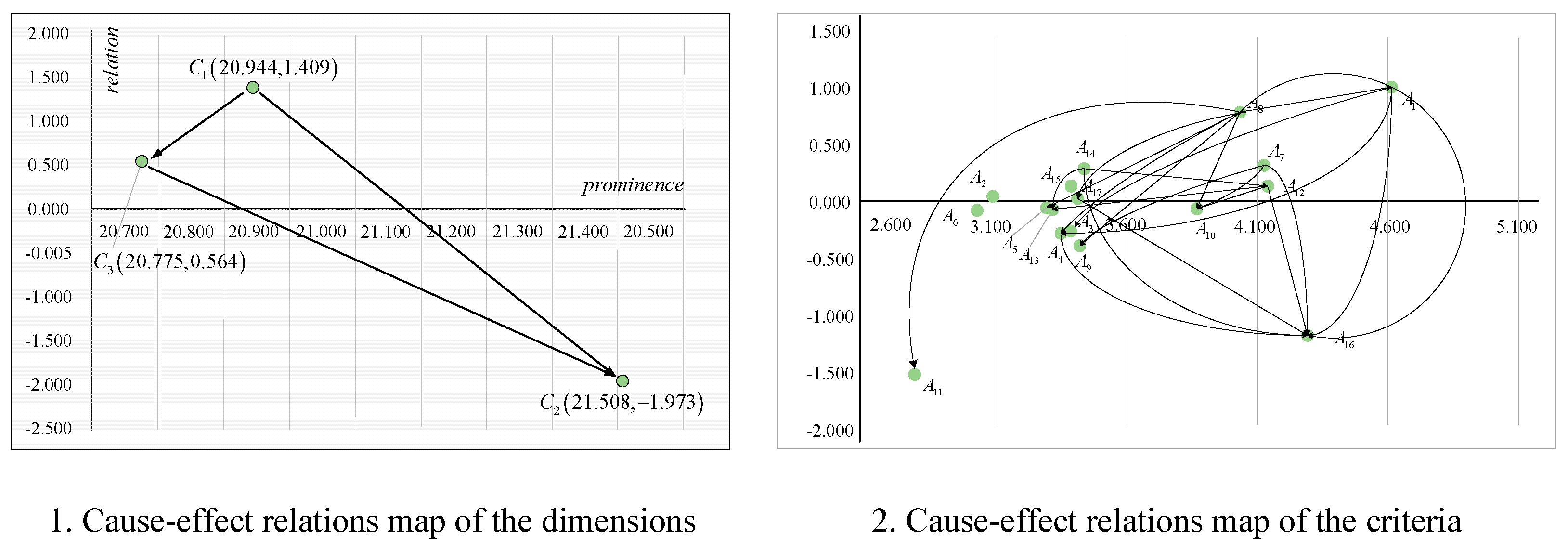

| 因素 | B | R | T | F | G | Z | Y | Cause/effect | ||||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | ||||||

| C1 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 3.25 | 3.13 | 3.39 | 11.18 | 9.77 | 20.94 | 1.41 | cause |

| C2 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 3.87 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 4.26 | 3.41 | 4.07 | 9.77 | 11.74 | 21.51 | -1.97 | effect |

| C3 | 3.32 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 3.67 | 3.23 | 3.21 | 10.67 | 10.11 | 20.78 | 0.56 | cause |

| criteria | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 | A10 | A11 | A12 | A13 | A14 | A15 | A16 | A17 |

| A1 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.89 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| A2 | 2.16 | 0.00 | 2.11 | 3.11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.27 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| A3 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 2.55 | 2.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| A4 | 1.00 | 1.42 | 1.11 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.74 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| A5 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 |

| A6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| A7 | 2.32 | 1.42 | 2.22 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 2.22 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 3.26 | 3.26 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 3.27 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| A8 | 3.11 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 3.13 | 3.11 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 3.36 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| A9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.31 | 2.35 | 2.15 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| A10 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.74 | 1.74 | 1.13 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| A11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.00 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| A12 | 1.66 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.26 | 0.00 | 3.74 | 2.73 | 1.00 | 3.18 | 1.00 |

| A13 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.74 | 1.00 | 3.16 | 0.00 | 3.73 | 1.00 | 1.73 | 1.00 |

| A14 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 3.51 | 1.13 |

| A15 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.47 | 1.00 | 2.24 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| A16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| A17 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

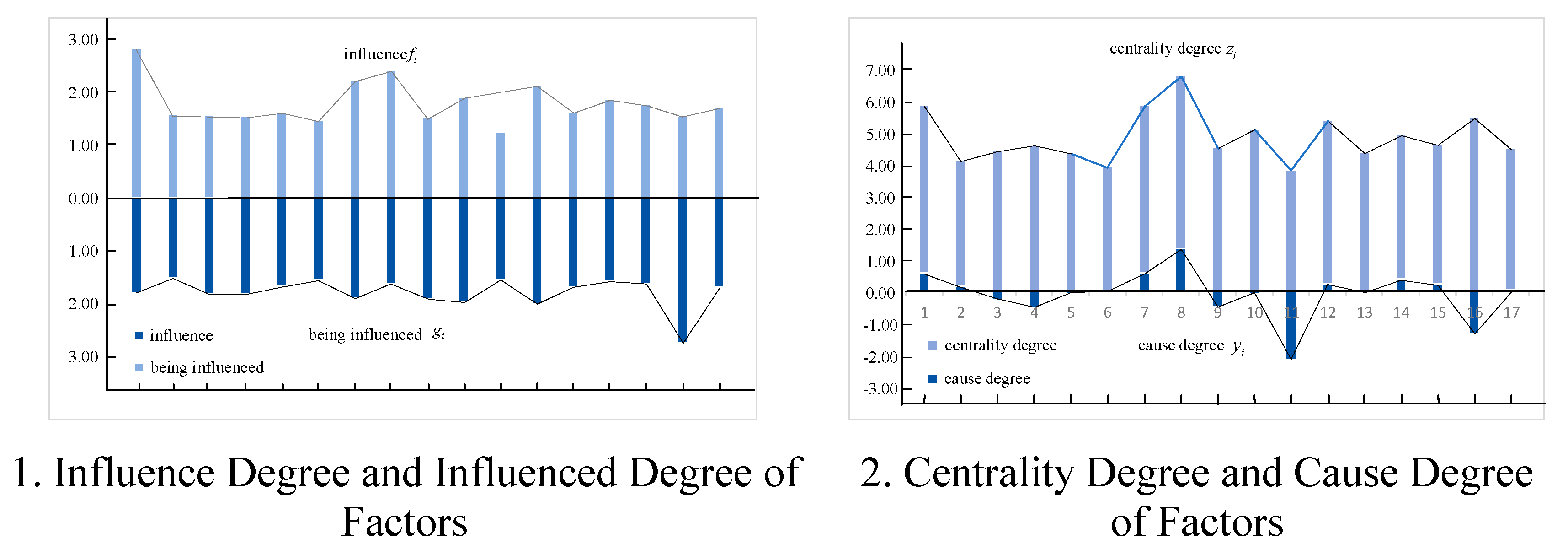

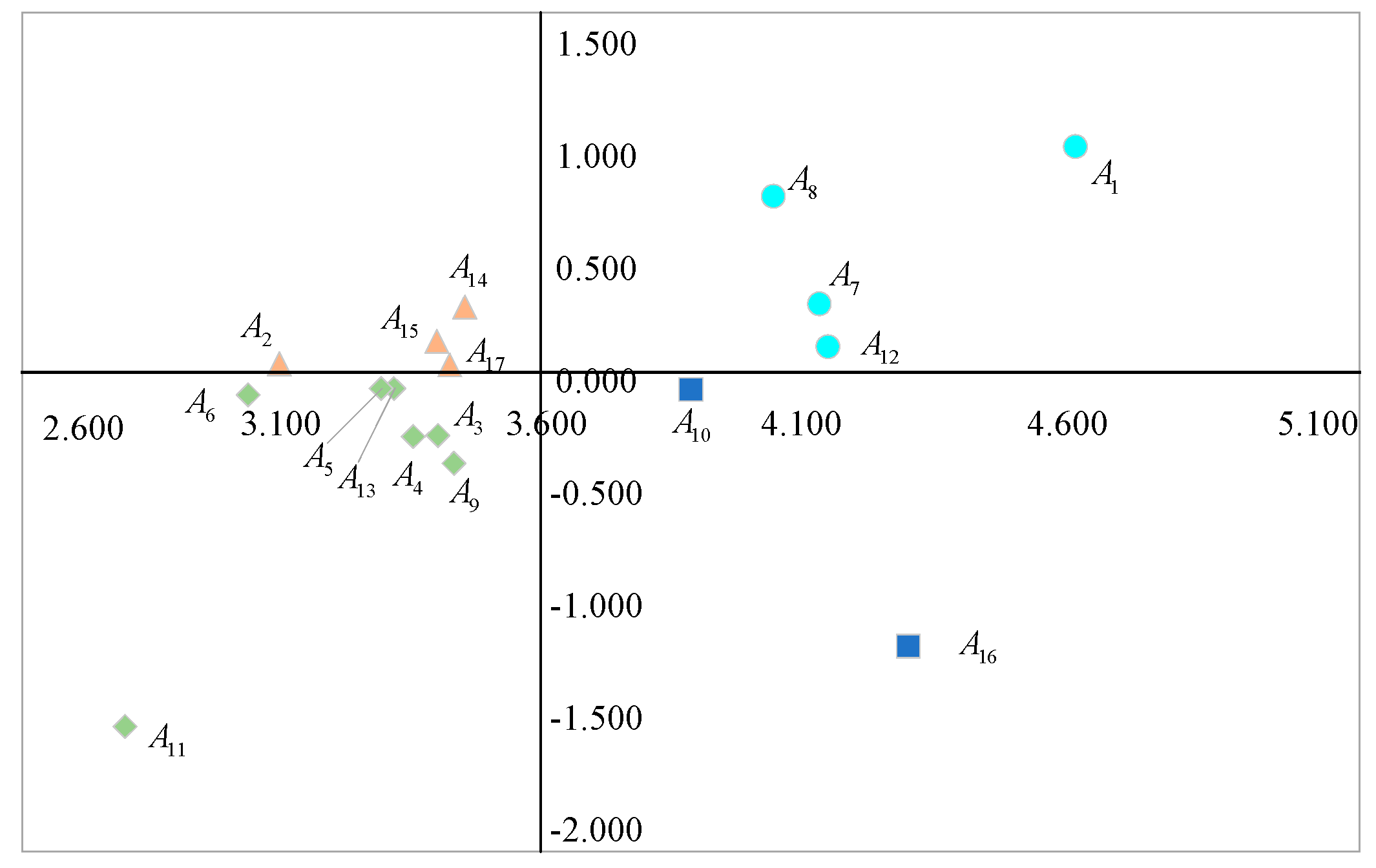

| Code | Dimension | F | G | Z | Y | Cause/effect |

| A1 | Power Generation Costs | 2.814 | 1.798 | 4.666 | 0.499 | cause |

| A2 | Flexibility of Conventional Energy Sources | 1.565 | 1.524 | 3.479 | 0.133 | cause |

| A3 | Application of energy storage technologies | 1.554 | 1.825 | 3.889 | -0.243 | effect |

| A4 | Renewable energy volatility | 1.537 | 1.814 | 4.047 | -0.471 | effect |

| A5 | Clean energy supply proportion | 1.621 | 1.678 | 3.824 | -0.075 | effect |

| A6 | Maximum transmission capacity of transmission lines | 1.471 | 1.556 | 3.450 | -0.005 | effect |

| A7 | Level of grid intelligence | 2.221 | 1.903 | 4.661 | 0.498 | cause |

| A8 | Distribution equipment capacity | 2.412 | 1.624 | 4.788 | 1.181 | cause |

| A9 | Energy utilization rate | 1.510 | 1.911 | 3.981 | -0.443 | effect |

| A10 | Demand response mechanisms | 1.900 | 1.969 | 4.476 | -0.080 | effect |

| A11 | User behavior characteristics | 1.240 | 1.549 | 3.358 | -1.913 | effect |

| A12 | Electricity Pricing Policy | 2.133 | 2.006 | 4.530 | 0.202 | cause |

| A13 | Electricity Market Reform | 1.623 | 1.685 | 3.845 | -0.064 | effect |

| A14 | Government Regulatory Intensity | 1.865 | 1.575 | 4.009 | 0.327 | cause |

| A15 | Load Forecasting Accuracy | 1.759 | 1.629 | 3.889 | 0.188 | cause |

| A16 | Multi-Energy Complementary Synergistic Benefits | 1.546 | 2.746 | 4.803 | -1.200 | effect |

| A17 | Equipment Whole-Life-Cycle Cost | 1.717 | 1.695 | 3.950 | 0.023 | cause |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).