Submitted:

13 February 2024

Posted:

14 February 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Platelet Margination

3. Platelet Adhesion

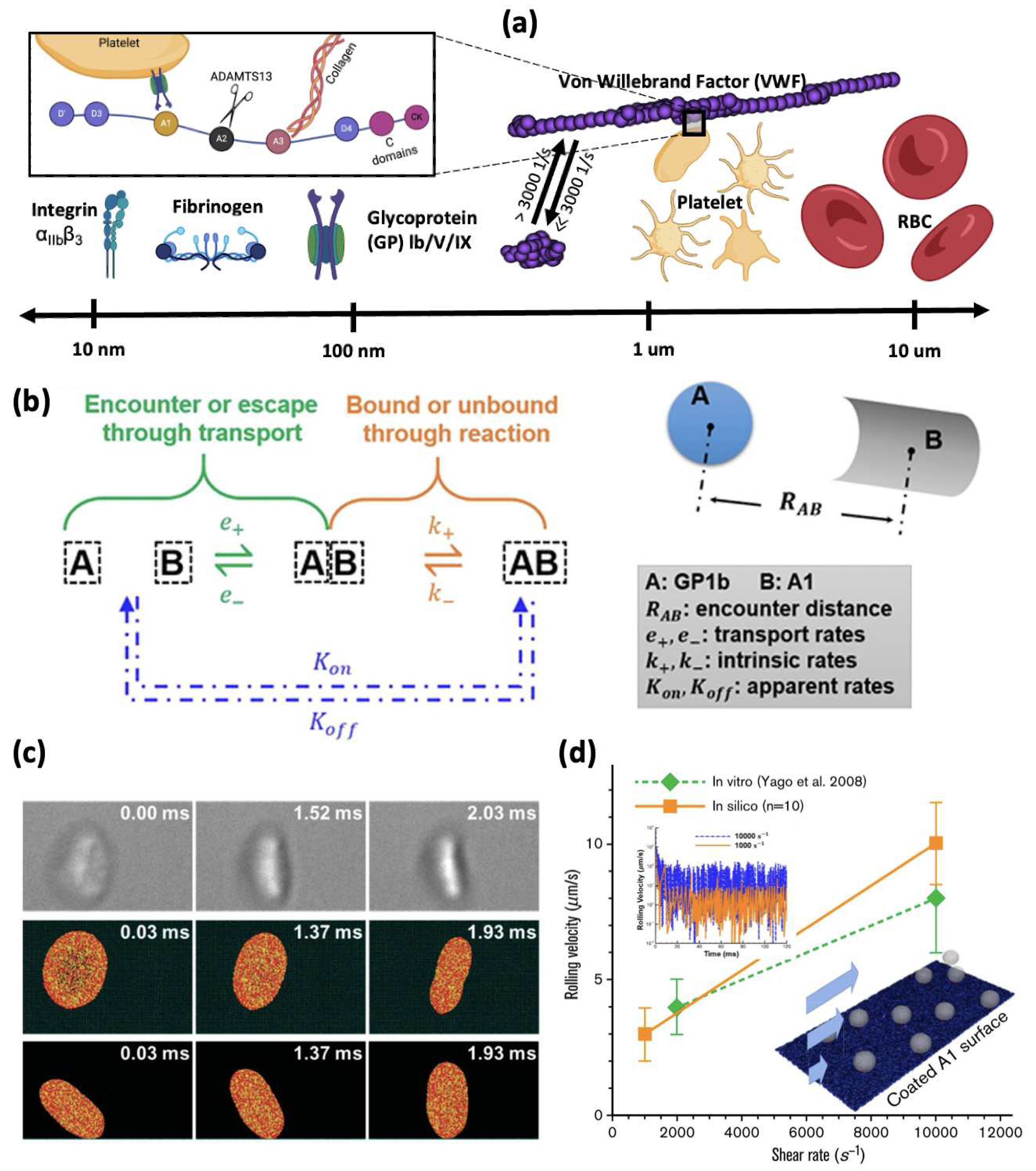

3.1. Binding Kinetics Supporting Platelet Adhesion

3.2. Multiscale Modelling of Platelet Adhesion

4. Platelet Activation

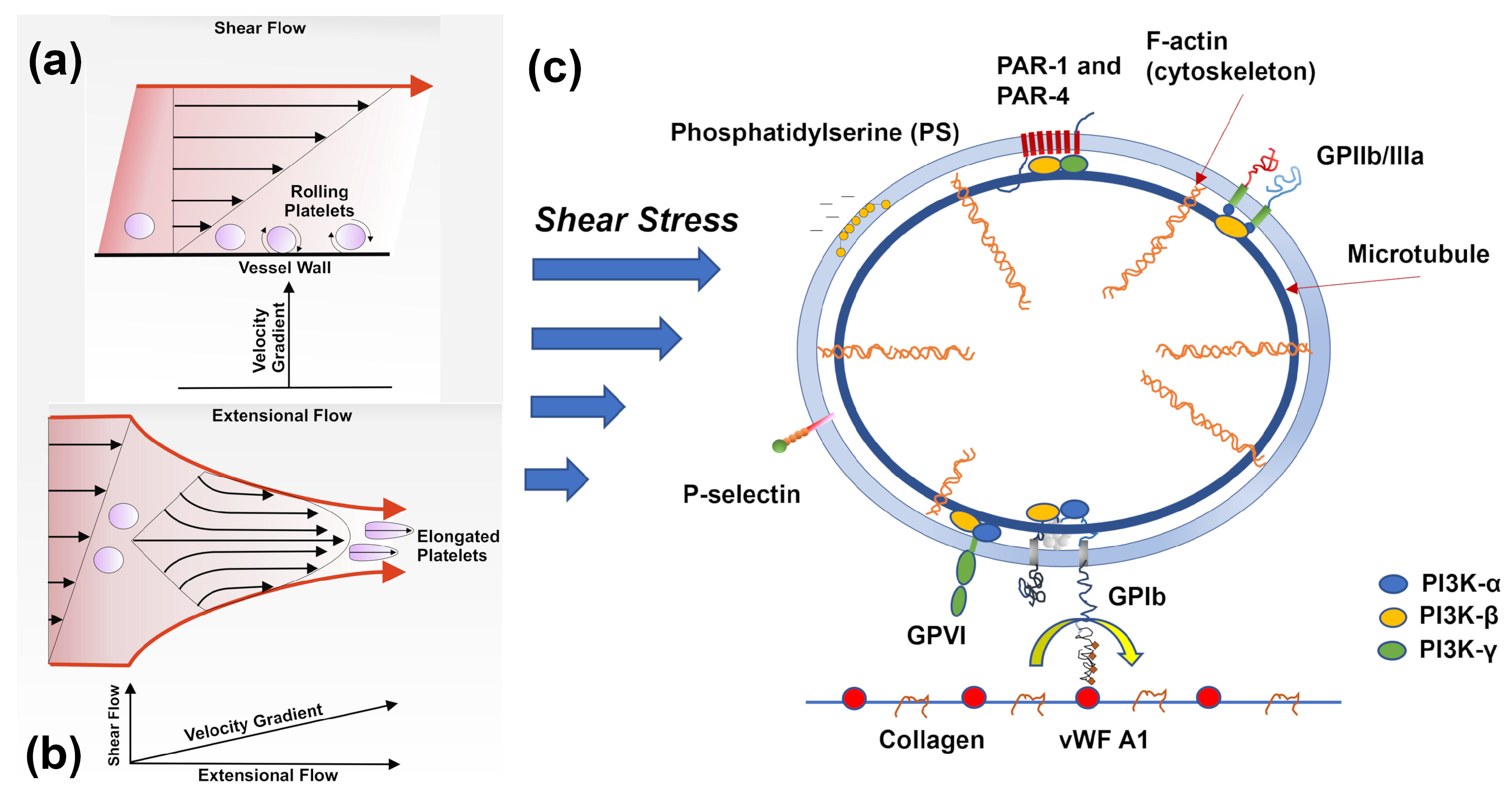

4.1. Platelet Mechanotransduction under Flow Shear Stress

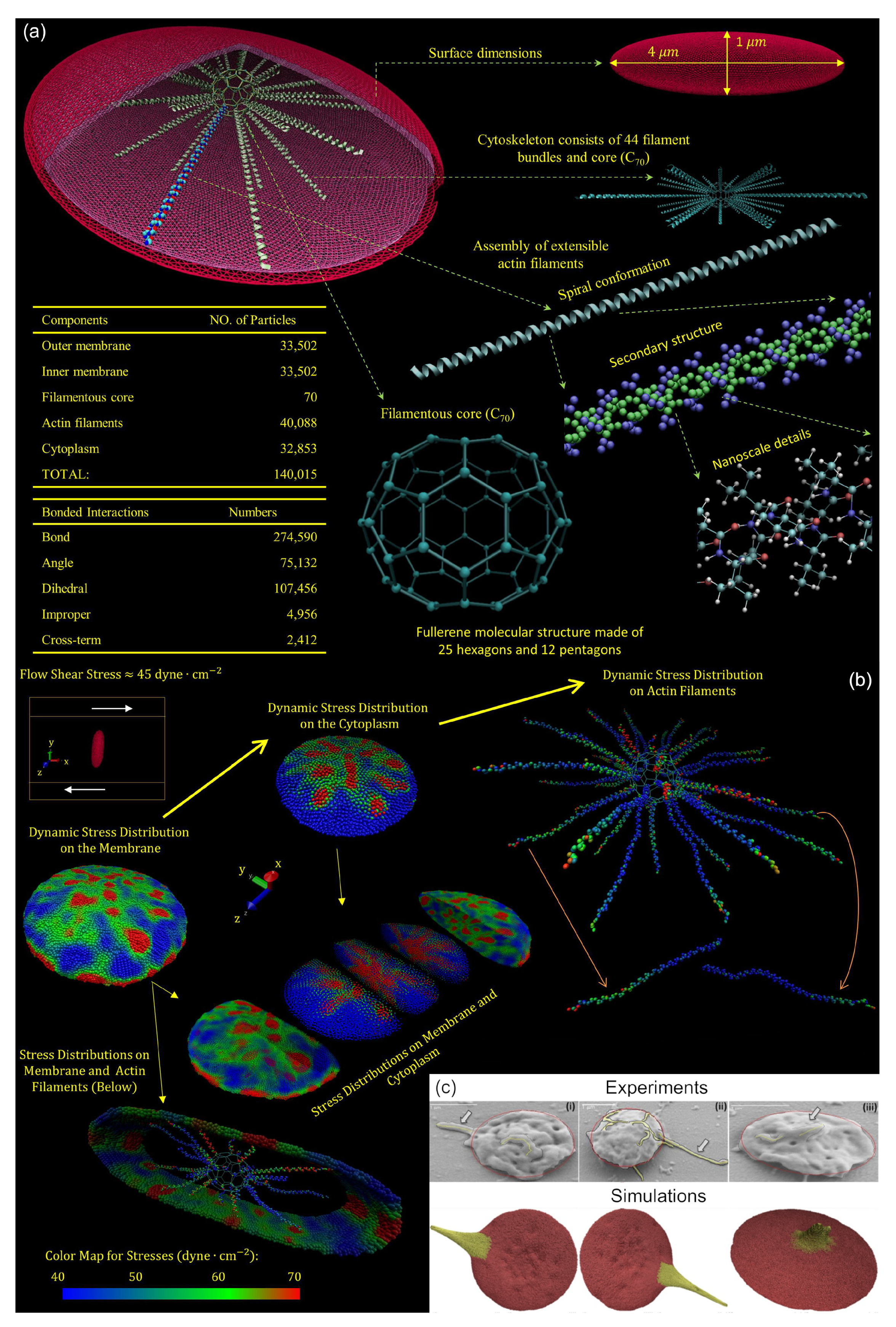

4.2. Resting and Activated Platelet Morphology under Flow Conditions

4.3. Changes in Platelet Mechanobiology due to Aging

4.4. Multiscale Modelling of Shear-induced Platelet Activation

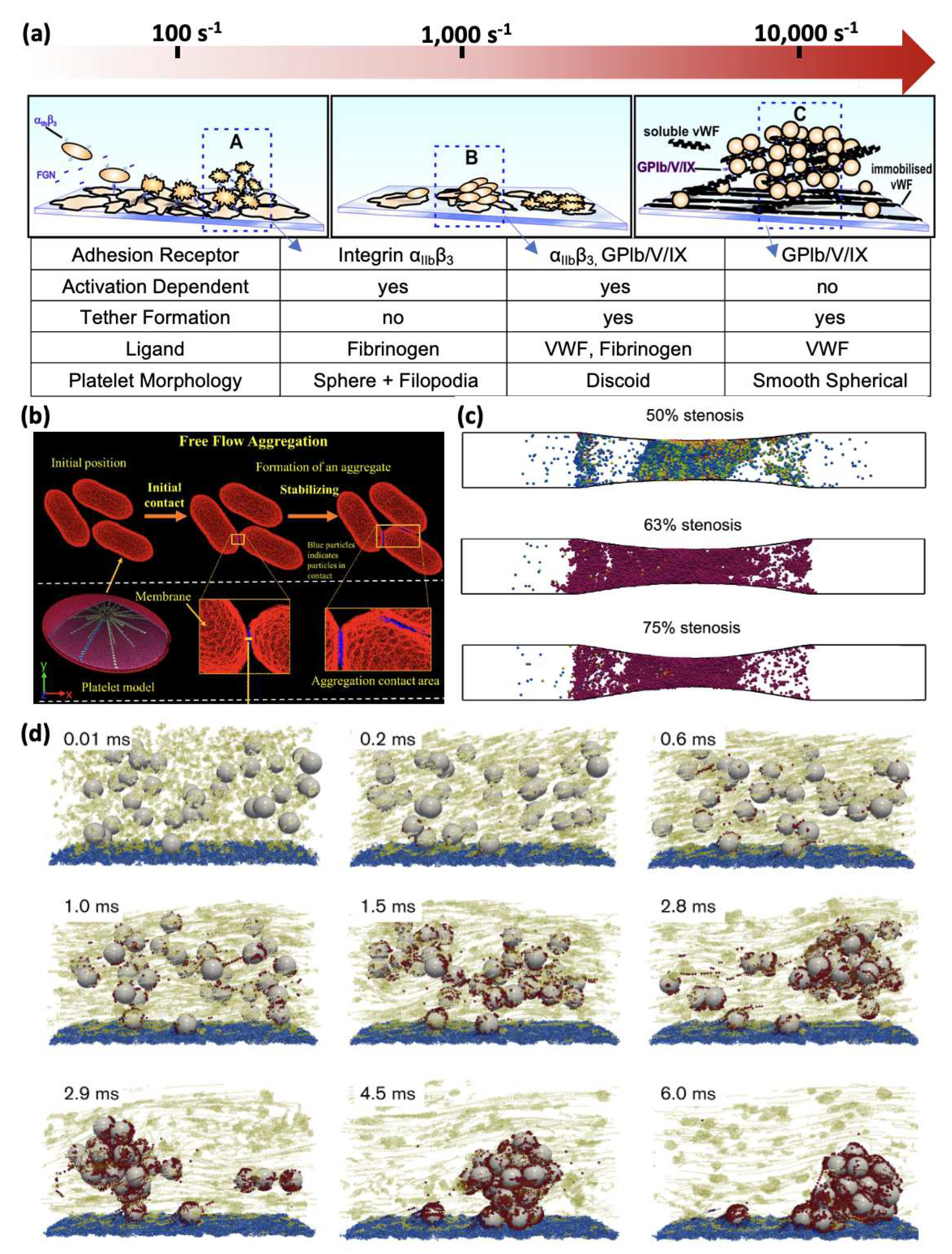

5. Platelet Aggregation

5.1. Multiscale Modelling of Shear-induced Platelet Aggregation

6. Platelet Mechanobiology Modelling in the Age of Data

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, T.; Shantsila, E.; Lip, G.Y. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow’s triad revisited. The Lancet 2009, 373, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, L.D.; Deaton, D.H.; Ku, D.N. Role of high shear rate in thrombosis. Journal of vascular surgery 2015, 61, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.L.; Bresette, C.; Aidun, C.K.; Ku, D.N. SIPA in 10 milliseconds: VWF tentacles agglomerate and capture platelets under high shear. Blood Advances 2022, 6, 2453–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casa, L.D.; Ku, D.N. Thrombus Formation at High Shear Rates. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Bresette, C.; Liu, Z.; Ku, D.N. Occlusive thrombosis in arteries. APL bioengineering 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.P. The growing complexity of platelet aggregation. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2007, 109, 5087–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.L.; Ku, D.N.; Aidun, C.K. Mechanobiology of shear-induced platelet aggregation leading to occlusive arterial thrombosis: A multiscale in silico analysis. Journal of Biomechanics 2021, 120, 110349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, T.W.; Hellums, J.D.; Moake, J.L.; Kroll, M.H. Shear stress-induced von Willebrand factor binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib initiates calcium influx associated with aggregation. Blood 1992, 80, 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.; Nesbitt, W.; Westein, E. Dynamics of platelet thrombus formation. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2009, 7, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moake, J.L.; Turner, N.A.; Stathopoulos, N.A.; Nolasco, L.H.; Hellums, J.D. Involvement of large plasma von Willebrand factor (vWF) multimers and unusually large vWF forms derived from endothelial cells in shear stress-induced platelet aggregation. The Journal of clinical investigation 1986, 78, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, Z.M. Platelet Adhesion under Flow. Microcirculation 2009, 16, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki, S.; Takagi, S.; Goto, S. Prediction of molecular interaction between platelet glycoprotein Ibα and von Willebrand factor using molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis 2016, 23, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, D.; Soley, N.; Kolasangiani, R.; Schwartz, M.A.; Bidone, T.C. Integrin αIIbβ3 intermediates: From molecular dynamics to adhesion assembly. Biophysical Journal 2023, 122, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidun, C.K.; Clausen, J.R. Lattice-Boltzmann method for complex flows. Annual review of fluid mechanics 2010, 42, 439–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, R.D.; Warren, P.B. Dissipative particle dynamics: Bridging the gap between atomistic and mesoscopic simulation. The Journal of chemical physics 1997, 107, 4423–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwinel, W.; Yuen, D.A.; Boryczko, K. Mesoscopic dynamics of colloids simulated with dissipative particle dynamics and fluid particle model. Molecular modeling annual 2002, 8, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dzwinel, W.; Boryczko, K.; Yuen, D.A. A discrete-particle model of blood dynamics in capillary vessels. Journal of colloid and interface science 2003, 258, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri, N.A.; Shyy, W.; Tran-Son-Tay, R. Computational modeling of cell adhesion and movement using a continuum-kinetics approach. Biophysical journal 2003, 85, 2273–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyy and, W.; Francois, M.; Udaykumar, H.S.; N’dri and, N.; Tran-Son-Tay, R. Moving boundaries in micro-scale biofluid dynamics. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2001, 54, 405–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.R.; Clausen, J.; Roberts, S.A.; Lechman, J.B.; Wagner, J.; Butler, K.; Bolintineanu, D.; Brinker, C.J.; Liu, L. Continuum modeling of Nanoparticle Transport in the Vasculature. Technical report, Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States), 2017.

- Rao, R.R.; Wagner, J.; Butler, K.; Clausen, J.; Martin, R.M.; Liu, L. Continuum Modeling of Nanoparticles Transport In Vivo Through Bifurcations. Technical report, Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States), 2018.

- Mehrabadi, M.; Ku, D.N.; Aidun, C.K. Effects of shear rate, confinement, and particle parameters on margination in blood flow. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 93, 023109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowl, L.; Fogelson, A.L. Analysis of mechanisms for platelet near-wall excess under arterial blood flow conditions. Journal of fluid mechanics 2011, 676, 348–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, P.A.; van den Broek, S.A.; Prins, G.W.; Kuiken, G.D.; Sixma, J.J.; Heethaar, R.M. Blood platelets are concentrated near the wall and red blood cells, in the center in flowing blood. Arteriosclerosis (Dallas, Tex.) 1988, 8, 819–824, Place: United States Publisher: Am Heart Assoc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reasor, D.A.; Mehrabadi, M.; Ku, D.N.; Aidun, C.K. Determination of Critical Parameters in Platelet Margination. Ann Biomed Eng 2013, 41, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shaqfeh, E.S. Shear-induced platelet margination in a microchannel. Physical Review E 2011, 83, 061924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shaqfeh, E.S.; Narsimhan, V. Shear-induced particle migration and margination in a cellular suspension. Physics of Fluids 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Graham, M.D. Margination and segregation in confined flows of blood and other multicomponent suspensions. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 10536–10548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Graham, M.D. Mechanism of Margination in Confined Flows of Blood and Other Multicomponent Suspensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Clausen, J.R.; Lechman, J.B.; Rao, R.R.; Aidun, C.K. Multiscale method based on coupled lattice-Boltzmann and Langevin-dynamics for direct simulation of nanoscale particle/polymer suspensions in complex flows. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2019, 91, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Clausen, J.R.; Rao, R.R.; Aidun, C.K. A unified analysis of nano-to-microscale particle dispersion in tubular blood flow. Physics of Fluids 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Clausen, J.R.; Rao, R.R.; Aidun, C.K. Nanoparticle diffusion in sheared cellular blood flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2019, 871, 636–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, Z.M.; Mendolicchio, G.L. Adhesion Mechanisms in Platelet Function. Circulation Research 2007, 100, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, B.; Saldívar, E.; Ruggeri, Z.M. Initiation of platelet adhesion by arrest onto fibrinogen or translocation on von Willebrand factor. Cell 1996, 84, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, B.; Almus-Jacobs, F.; Ruggeri, Z.M. Specific synergy of multiple substrate–receptor interactions in platelet thrombus formation under flow. Cell 1998, 94, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, Z.M.; Orje, J.N.; Habermann, R.; Federici, A.B.; Reininger, A.J. Activation-independent platelet adhesion and aggregation under elevated shear stress. Blood 2006, 108, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, D.; Scheiflinger, F.; Wong, W.P.; Springer, T.A. Flow-induced elongation of von Willebrand factor precedes tension-dependent activation. Nature communications 2017, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellings, P.J.; Ku, D.N. Mechanisms of Platelet Capture Under Very High Shear. Cardiovasc Eng Tech 2012, 3, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantgan, R.R.; Stahle, M.C.; Lord, S.T. Dynamic Regulation of Fibrinogen: Integrin αIIbβ3 Binding. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9217–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yago, T.; Lou, J.; Wu, T.; Yang, J.; Miner, J.J.; Coburn, L.; López, J.A.; Cruz, M.A.; Dong, J.F.; McIntire, L.V. Platelet glycoprotein Ibα forms catch bonds with human WT vWF but not with type 2B von Willebrand disease vWF. The Journal of clinical investigation 2008, 118, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, J.; Yuan, Z.; Li, K.; Liu, B.; Ju, L.A.; Zhu, C. Fast force loading disrupts molecular binding stability in human and mouse cell adhesions. Molecular & cellular biomechanics: MCB 2019, 16, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Ju, L.A.; Zhou, F.; Liao, J.; Xue, L.; Su, Q.P.; Jin, D.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, H.; Jackson, S.P. An integrin αIIbβ3 intermediate affinity state mediates biomechanical platelet aggregation. Nature materials 2019, 18, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, D.A.; Lauffenburger, D.A. A dynamical model for receptor-mediated cell adhesion to surfaces. Biophysical journal 1987, 52, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, D.A.; Apte, S.M. Simulation of cell rolling and adhesion on surfaces in shear flow: general results and analysis of selectin-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Biophysical journal 1992, 63, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, N.A.; Lomakin, O.; Doggett, T.A.; Diacovo, T.G.; King, M.R. Mechanics of transient platelet adhesion to von Willebrand factor under flow. Biophysical journal 2005, 88, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Zhang, P.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. A Multiscale Model for Shear-Mediated Platelet Adhesion Dynamics: Correlating In Silico with In Vitro Results. Ann Biomed Eng 2023, 51, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, A.V.; Kushchenko, Y.K. Biomechanical activation of blood platelets via adhesion to von Willebrand factor studied with mesoscopic simulations. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2023, 22, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosemans, J.M.; Angelillo-Scherrer, A.; Mattheij, N.J.; Heemskerk, J.W. The effects of arterial flow on platelet activation, thrombus growth, and stabilization. Cardiovascular research 2013, 99, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, H.H.; Heemskerk, J.W.M.; Levi, M.; Reitsma, P.H. New Fundamentals in Hemostasis. Physiological Reviews 2013, 93, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.A.; Ashworth, K.J.; Di Paola, J.; Ku, D.N. Platelet α-granules are required for occlusive high-shear-rate thrombosis. Blood advances 2020, 4, 3258–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L. Mechanisms of platelet activation: Need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2009, 102, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, M.H.; Harris, T.S.; Moake, J.L.; Handin, R.I.; Schafer, A.I. von Willebrand factor binding to platelet GpIb initiates signals for platelet activation. The Journal of clinical investigation 1991, 88, 1568–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.L.; Malehsa, D.; Bara, C.; Budde, U.; Slaughter, M.S.; Haverich, A.; Strueber, M. Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome in Patients With an Axial Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device. Circ: Heart Failure 2010, 3, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepian, M.J.; Sheriff, J.; Hutchinson, M.; Tran, P.; Bajaj, N.; Garcia, J.G.; Saavedra, S.S.; Bluestein, D. Shear-mediated platelet activation in the free flow: Perspectives on the emerging spectrum of cell mechanobiological mechanisms mediating cardiovascular implant thrombosis. Journal of biomechanics 2017, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellums, J.; Peterson, D.; Stathopoulos, N.; Moake, J.; Giorgio, T. Studies on the mechanisms of shear-induced platelet activation. In Proceedings of the Cerebral ischemia and hemorheology. Springer, 1987, pp. 80–89.

- Kroll, M.H.; Hellums, J.D.; McIntire, L.V.; Schafer, A.I.; Moake, J.L. Platelets and shear stress. Blood 1996, 88, 1525–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, G.; Bluestein, D. Biological effects of dynamic shear stress in cardiovascular pathologies and devices. Expert Review of Medical Devices 2008, 5, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E.; Wang, N.; Stamenović, D. Tensegrity, cellular biophysics, and the mechanics of living systems. Reports on Progress in Physics 2014, 77, 046603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheriff, J.; Bluestein, D.; Girdhar, G.; Jesty, J. High-Shear Stress Sensitizes Platelets to Subsequent Low-Shear Conditions. Ann Biomed Eng 2010, 38, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, J.; Tran, P.L.; Hutchinson, M.; DeCook, T.; Slepian, M.J.; Bluestein, D.; Jesty, J. Repetitive Hypershear Activates and Sensitizes Platelets in a Dose-Dependent Manner. Artificial Organs 2016, 40, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girdhar, G.; Xenos, M.; Alemu, Y.; Chiu, W.C.; Lynch, B.E.; Jesty, J.; Einav, S.; Slepian, M.J.; Bluestein, D. Device thrombogenicity emulation: a novel method for optimizing mechanical circulatory support device thromboresistance. PloS one 2012, 7, e32463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, J.; Soares, J.S.; Xenos, M.; Jesty, J.; Bluestein, D. Evaluation of Shear-Induced Platelet Activation Models Under Constant and Dynamic Shear Stress Loading Conditions Relevant to Devices. Ann Biomed Eng 2013, 41, 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A.; Wright, J.R.; Mahaut-Smith, M.P. Regulation of Pannexin-1 channel activity. Biochemical Society Transactions 2015, 43, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A.; Wright, J.R.; Vial, C.; Evans, R.J.; Mahaut-Smith, M.P. Amplification of human platelet activation by surface pannexin-1 channels. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2014, 12, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkan, Z.; Wright, J.R.; Goodall, A.H.; Gibbins, J.M.; Jones, C.I.; Mahaut-Smith, M.P. Evidence for shear-mediated Ca2+ entry through mechanosensitive cation channels in human platelets and a megakaryocytic cell line. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292, 9204–9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammadova-Bach, E.; Gudermann, T.; Braun, A. Platelet Mechanotransduction: Regulatory Cross Talk Between Mechanosensitive Receptors and Calcium Channels. ATVB 2023, 43, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainal Abidin, N.A.; Poon, E.K.W.; Szydzik, C.; Timofeeva, M.; Akbaridoust, F.; Brazilek, R.J.; Tovar Lopez, F.J.; Ma, X.; Lav, C.; Marusic, I.; et al. An extensional strain sensing mechanosome drives adhesion-independent platelet activation at supraphysiological hemodynamic gradients. BMC Biol 2022, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Wei, Z.; Xin, G.; Li, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ming, Y.; Ji, C.; Sun, Q.; Li, S.; Chen, X. Piezo1 initiates platelet hyperreactivity and accelerates thrombosis in hypertension. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2021, 19, 3113–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di-Luoffo, M.; Ben-Meriem, Z.; Lefebvre, P.; Delarue, M.; Guillermet-Guibert, J. PI3K functions as a hub in mechanotransduction. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2021, 46, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Li, T.; Kareem, K.; Tran, D.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. The role of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in non-physiological shear stress-induced platelet activation. Artificial Organs 2019, 43, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, C.L.; Anderson, K.E.; Hughan, S.C.; Dopheide, S.M.; Salem, H.H.; Jackson, S.P. Essential role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in shear-dependent signaling between platelet glycoprotein Ib/V/IX and integrin αIIbβ3. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2002, 99, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, G.F.; Canobbio, I.; Torti, M. PI3K/Akt in platelet integrin signaling and implications in thrombosis. Advances in biological regulation 2015, 59, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghigo, A.; Morello, F.; Perino, A.; Hirsch, E. Therapeutic applications of PI3K inhibitors in cardiovascular diseases. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 5, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.P.; Schoenwaelder, S.M.; Goncalves, I.; Nesbitt, W.S.; Yap, C.L.; Wright, C.E.; Kenche, V.; Anderson, K.E.; Dopheide, S.M.; Yuan, Y. PI 3-kinase p110β: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nature medicine 2005, 11, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, P.A.; Séverin, S.; Hechler, B.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Payrastre, B.; Gratacap, M.P. Platelet PI3Kβ and GSK3 regulate thrombus stability at a high shear rate. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2015, 125, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainal Abidin, N.A.; Timofeeva, M.; Szydzik, C.; Akbaridoust, F.; Lav, C.; Marusic, I.; Mitchell, A.; Hamilton, J.R.; Ooi, A.S.H.; Nesbitt, W.S. A microfluidic method to investigate platelet mechanotransduction under extensional strain. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2023, 7, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frojmovic, M.M.; Panjwani, R. Geometry of normal mammalian platelets by quantitative microscopic studies. Biophysical journal 1976, 16, 1071–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnutt, J.K.; Han, H.C. Platelet size and density affect shear-induced thrombus formation in tortuous arterioles. Physical biology 2013, 10, 056003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, A.; Moskalensky, A.; Karmadonova, N.; Nekrasov, V.; Strokotov, D.; Konokhova, A.; Yurkin, M.; Pokushalov, E.; Chernyshev, A.; Maltsev, V. Fluorescence-free flow cytometry for measurement of shape index distribution of resting, partially activated, and fully activated platelets. Cytometry Pt A 2016, 89, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, J.H. The platelet: form and function. In Proceedings of the Seminars in hematology. Elsevier, 2006, Vol. 43, pp. S94–S100.

- White, J.G., CHAPTER 3 - Platelet Structure. In Platelets (Second Edition); Michelson, A.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, 2007; pp. 45–73. Burlington.

- Raucher, D.; Sheetz, M.P. Characteristics of a membrane reservoir buffering membrane tension. Biophysical journal 1999, 77, 1992–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalensky, A.E.; Litvinenko, A.L. The platelet shape change: biophysical basis and physiological consequences. Platelets 2019, 30, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.G.; Rao, G. Microtubule coils versus the surface membrane cytoskeleton in maintenance and restoration of platelet discoid shape. The American journal of pathology 1998, 152, 597. [Google Scholar]

- Italiano Jr, J.E.; Bergmeier, W.; Tiwari, S.; Falet, H.; Hartwig, J.H.; Hoffmeister, K.M.; André, P.; Wagner, D.D.; Shivdasani, R.A. Mechanisms and implications of platelet discoid shape. Blood 2003, 101, 4789–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, J.H.; DeSisto, M. The cytoskeleton of the resting human blood platelet: structure of the membrane skeleton and its attachment to actin filaments. The Journal of cell biology 1991, 112, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, J.; Barkalow, K.; Azim, A.; Italiano, J. The Elegant Platelet: Signals Controlling Actin Assembly. Thromb Haemost 1999, 82, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzenberg, N.; Haghighat Talab, A.T.; Massé, J.M.; Drouin, A.; Jondeau, K.; Kobeiter, H.; Baruch, D.; Cramer, E.M. Platelet shape change and subsequent glycoprotein redistribution in human stenosed arteries. Platelets 2005, 16, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plooy, J.N.; Buys, A.; Duim, W.; Pretorius, E. Comparison of platelet ultrastructure and elastic properties in thrombo-embolic ischemic stroke and smoking using atomic force and scanning electron microscopy. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurzinger, L.J.; Blasberg, P.; Schmid-Schönbein, H. Towards a concept of thrombosis in accelerated flow: rheology, fluid dynamics, and biochemistry. Biorheology 1985, 22, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurzinger, L.J.; Opitz, R.; Wolf, M.; Schmid-Schnöbein, H. Ultrastructural investigations on the question of mechanical activation of blood platelets. Blut 1987, 54, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvis Jr, N.B.; Giorgio, T.D. The effects of elongational stress exposure on the activation and aggregation of blood platelets. Biorheology 1991, 28, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Mondal, N.K.; Ding, J.; Gao, J.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. Shear-induced platelet receptor shedding by non-physiological high shear stress with short exposure time: glycoprotein Ibα and glycoprotein VI. Thrombosis research 2015, 135, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Mondal, N.K.; Ding, J.; Koenig, S.C.; Slaughter, M.S.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. Activation and shedding of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa under non-physiological shear stress. Mol Cell Biochem 2015, 409, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Mondal, N.K.; Zheng, S.; Koenig, S.C.; Slaughter, M.S.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. High shear induces platelet dysfunction leading to enhanced thrombotic propensity and diminished hemostatic capacity. Platelets 2019, 30, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holme, P.A.; Ørvim, U.; Hamers, M.J.A.G.; Solum, N.O.; Brosstad, F.R.; Barstad, R.M.; Sakariassen, K.S. Shear-Induced Platelet Activation and Platelet Microparticle Formation at Blood Flow Conditions as in Arteries With a Severe Stenosis. ATVB 1997, 17, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.I. Platelet function and ageing. Mammalian Genome 2016, 27, 358–366, Place: New York Publisher: Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, J.; Dunne, E.; Oglesby, I.; Byrne, B.; Ralph, A.; Voisin, B.; Müllers, S.; Ricco, A.J.; Kenny, D. Age-related changes in platelet function are more profound in women than in men. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 12235–12235, Place: England Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnla, A.; Reinthaler, M.; Braune, S.; Maier, A.; Pindur, G.; Lendlein, A.; Jung, F. Spontaneous and induced platelet aggregation in apparently healthy subjects in relation to age. Clinical hemorheology and microcirculation 2019, 71, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola-Visner, M. Platelets in the neonatal period: developmental differences in platelet production, function, and hemostasis and the potential impact of therapies. Hematology 2010, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2012, 2012, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, B.; Setty, B.N.; Chen, D.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; Stuart, M.J. Impaired mobilization of intracellular calcium in neonatal platelets. Pediatric research 1996, 39, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israels, S.J.; Rand, M.L.; Michelson, A.D. Neonatal platelet function. In Proceedings of the Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. Copyright© 2003 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New …, 2003, Vol. 29, pp. 363–372.

- Sitaru, A.; Holzhauer, S.; Speer, C.; Singer, D.; Obergfell, A.; Walter, U.; Grossmann, R. Neonatal platelets from cord blood and peripheral blood. Platelets 2005, 16, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, H.; Rosenkranz, A.; Novak, M.; Leschnik, B.; Petritsch, M.; Rehak, T.; Köfeler, H.; Ulrich, D.; Muntean, W. No differences in support of thrombin generation by neonatal or adult platelets. Hamostaseologie 2009, 29, S94–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvirn, G.; Gallistl, S.; Rehak, T.; Jürgens, G.; Muntean, W. Elevated thrombin-forming capacity of tissue factor-activated cord compared with adult plasma. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2003, 1, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, W.; Leschnik, B.; Baier, K.; Cvirn, G.; Gallistl, S. In vivo thrombin generation in neonates. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2004, 2, 2071–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Groberg, S.; Lattimore, S.; Recht, M.; McCarty, O.; Haley, K. Assessment of neonatal platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2016, 14, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Shraga, Y.; Maayan-Metzger, A.; Lubetsky, A.; Shenkman, B.; Kuint, J.; Martinowitz, U.; Kenet, G. Platelet function of newborns as tested by cone and plate (let) analyzer correlates with gestational age. Acta haematologica 2006, 115, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, J.; Malone, L.E.; Avila, C.; Zigomalas, A.; Bluestein, D.; Bahou, W.F. Shear-Induced Platelet Activation is Sensitive to Age and Calcium Availability: A Comparison of Adult and Umbilical Cord Blood. Cell Mol Bioeng 2020, 13, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Perez, E.; Teruel-Montoya, R.; López-Andreo, M.J.; Llanos, M.C.; Rivera, J.; Palma-Barqueros, V.; Blanco, J.E.; Vicente, V.; Martínez, C.; Ferrer-Marín, F. Comprehensive comparison of neonate and adult human platelet transcriptomes. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0183042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saving, K.L.; Jennings, D.E.; Aldag, J.C.; Caughey, R.C. Platelet ultrastructure of high-risk premature infants. Thrombosis research 1994, 73, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, N.A.; King, M.R. Three-dimensional simulations of a platelet-shaped spheroid near a wall in shear flow. Physics of Fluids 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, N.A.; King, M.R. Platelet adhesive dynamics. Part I: characterization of platelet hydrodynamic collisions and wall effects. Biophysical journal 2008, 95, 2539–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, N.A.; King, M.R. Platelet adhesive dynamics. Part II: high shear-induced transient aggregation via GPIbα-vWF-GPIbα bridging. Biophysical journal 2008, 95, 2556–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozrikidis, C. Flipping of an adherent blood platelet over a substrate. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2006, 568, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, C.R.; Chatterjee, S.; Xu, Z.; Bisordi, K.; Rosen, E.D.; Alber, M. Modelling platelet–blood flow interaction using the subcellular element Langevin method. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011, 8, 1760–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Kim, O.; Alber, M. Three-dimensional multi-scale model of deformable platelets adhesion to vessel wall in blood flow. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2014, 372, 20130380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, C.; Zhang, N.; Slepian, M.J.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. Multiscale Particle-Based Modeling of Flowing Platelets in Blood Plasma Using Dissipative Particle Dynamics and Coarse Grained Molecular Dynamics. Cel. Mol. Bioeng. 2014, 7, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Slepian, M.J.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. A multiscale biomechanical model of platelets: Correlating with in-vitro results. Journal of biomechanics 2017, 50, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothapragada, S.; Zhang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Livelli, M.; Slepian, M.J.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. A phenomenological particle-based platelet model for simulating filopodia formation during early activation. Numer Methods Biomed Eng 2015, 31, e02702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Einav, S.; Slepian, M.J.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. A predictive multiscale model for simulating flow-induced platelet activation: Correlating in silico results with in vitro results. Journal of biomechanics 2021, 117, 110275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, M.J.; Westein, E.; Nesbitt, W.S.; Giuliano, S.; Dopheide, S.M.; Jackson, S.P. Identification of a 2-stage platelet aggregation process mediating shear-dependent thrombus formation. Blood 2007, 109, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, Z.M. Mechanisms Initiating Platelet Thrombus Formation. Thromb Haemost 1997, 78, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogelson, A.L.; Neeves, K.B. Fluid Mechanics of Blood Clot Formation. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2015, 47, 377–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamm, M.H.; Colace, T.V.; Chatterjee, M.S.; Jing, H.; Zhou, S.; Jaeger, D.; Brass, L.F.; Sinno, T.; Diamond, S.L. Multiscale prediction of patient-specific platelet function under flow. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2012, 120, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Zhang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Bluestein, D.; Deng, Y. A Multiscale Model for Recruitment Aggregation of Platelets by Correlating with In Vitro Results. Cel. Mol. Bioeng. 2019, 12, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Zhang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Bluestein, D.; Deng, Y. A multiscale model for multiple platelet aggregation in shear flow. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2021, 20, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelson, A.L.; Guy, R.D. Immersed-boundary-type models of intravascular platelet aggregation. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2008, 197, 2087–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, D.; Yano, K.; Tsubota, K.i.; Ishikawa, T.; Wada, S.; Yamaguchi, T. Simulation of platelet adhesion and aggregation regulated by fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor. Thromb Haemost 2008, 99, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shankar, K.N.; Zhang, Y.; Sinno, T.; Diamond, S.L. A three-dimensional multiscale model for the prediction of thrombus growth under flow with single-platelet resolution. PLoS computational biology 2022, 18, e1009850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Kim, D.; Alhawael, G.; Ku, D.N.; Fogelson, A.L. Clot permeability, agonist transport, and platelet binding kinetics in arterial thrombosis. Biophysical journal 2020, 119, 2102–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Fogelson, A.L. A computational investigation of occlusive arterial thrombosis. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, M.J.; Westein, E.; Nesbitt, W.S.; Giuliano, S.; Dopheide, S.M.; Jackson, S.P. Identification of a 2-stage platelet aggregation process mediating shear-dependent thrombus formation. Blood 2007, 109, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.S.; Purvis, J.E.; Brass, L.F.; Diamond, S.L. Pairwise agonist scanning predicts cellular signaling responses to combinatorial stimuli. Nature biotechnology 2010, 28, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yasumoto, A.; Lei, C.; Huang, C.J.; Kobayashi, H.; Wu, Y.; Yan, S.; Sun, C.W.; Yatomi, Y.; Goda, K. Intelligent classification of platelet aggregates by agonist type. Elife 2020, 9, e52938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, C.; Butler, G.; Kuznecova, E.; Taylor, K.A.; Kriek, N.; Little, G.; Sowa, M.A.; Sage, T.; Johnson, L.J.; Gibbins, J.M. Fully automated platelet differential interference contrast image analysis via deep learning. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P.; Sheriff, J.; Bluestein, D.; Deng, Y. Rapid analysis of streaming platelet images by semi-unsupervised learning. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2021, 89, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheriff, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Bluestein, D. In Vitro Measurements of Shear-Mediated Platelet Adhesion Kinematics as Analyzed through Machine Learning. Ann Biomed Eng 2021, 49, 3452–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Han, C.; Cong, G.; Yang, C.C.; Deng, Y. Online machine learning for accelerating molecular dynamics modeling of cells. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2022, 8, 812248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitnik, M.; Nguyen, F.; Wang, B.; Leskovec, J.; Goldenberg, A.; Hoffman, M.M. Machine learning for integrating data in biology and medicine: Principles, practice, and opportunities. Information Fusion 2019, 50, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, K.N.; Zhang, Y.; Sinno, T.; Diamond, S.L. A three-dimensional multiscale model for the prediction of thrombus growth under flow with single-platelet resolution. PLoS computational biology 2022, 18, e1009850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Cong, G.; Kozloski, J.R.; Yang, C.C.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Y. Scalable multiscale modeling of platelets with 100 million particles. J Supercomput 2022, 78, 19707–19724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Han, C.; Zhang, P.; Cong, G.; Kozloski, J.R.; Yang, C.C.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Y. AI-aided multiscale modeling of physiologically-significant blood clots. Computer Physics Communications 2023, 287, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).