Submitted:

10 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of the Adsorbent

2.1.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra

2.1.2. The X-ray Diffraction Pattern

2.1.3. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy

2.1.4. The BET Surface Area and Distribution of Pore Size

2.1.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.1.7. Magnetic Hysteresis Curves

2.2. Adsorption Study on the Fe-SBE/C

2.2.1. Influence of Calcination Conditions

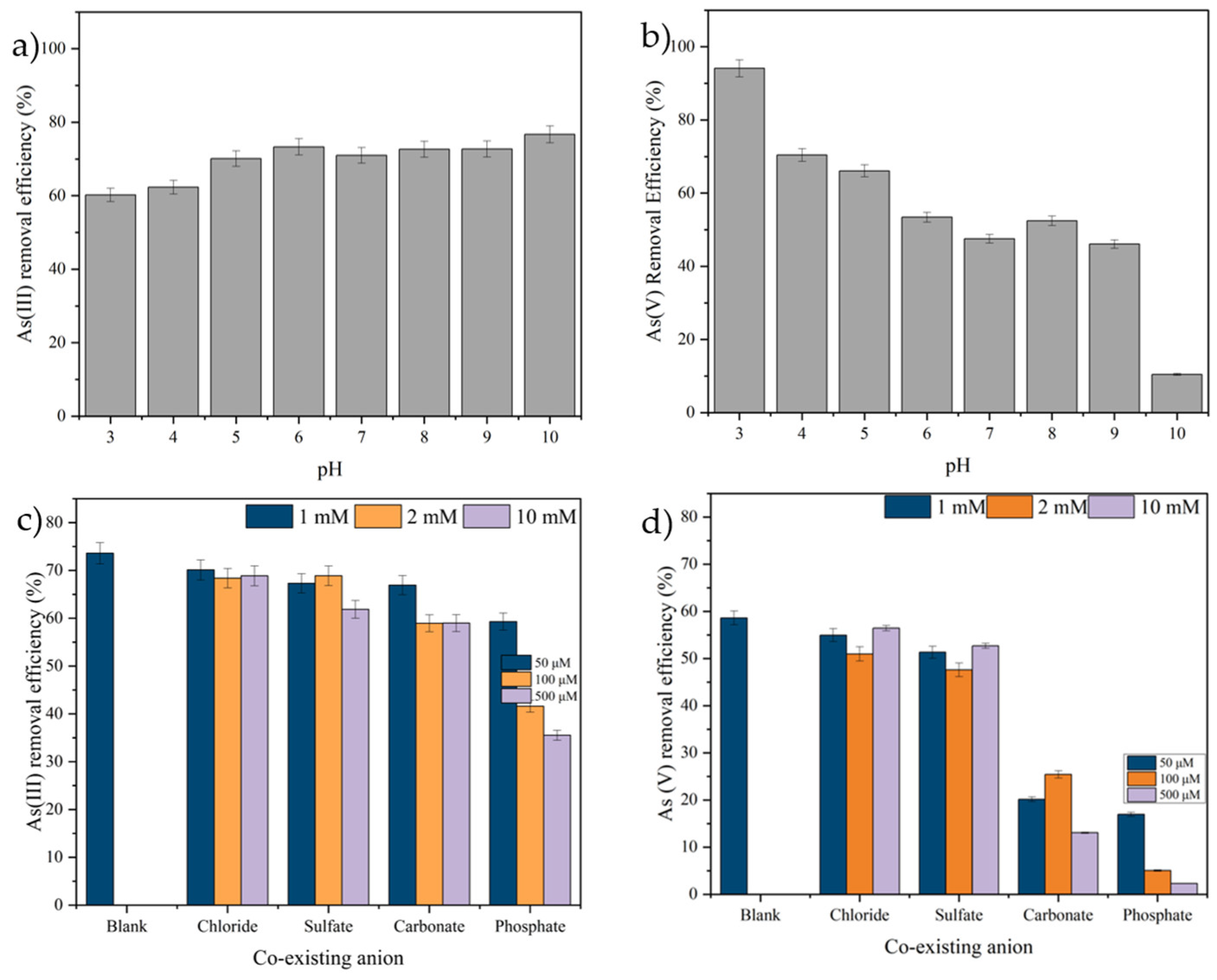

2.2.2. Influence of the Initial pH of Solutions

2.2.3. The Influences of Dosage and Iron Ratio of Fe-SBE/C

2.2.4. The Influence of Co-Existing Ions

2.2.5. Adsorption Kinetics

2.2.6. Adsorption Isotherm

2.2.7. Adsorption Thermodynamics

2.3. Regeneration and Reusability Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of the Materials

3.2.1. Preparation of SBE/C Composite

3.2.2. Modification of Iron-Loaded Spent Bleaching Earth (Fe-SBE/C)

3.2.3. Adsorption of As(III) and As(V) Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- USEPA 2002 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories 2002 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories. 2002, 19.

- Fendorf, S.; Kocar, B.D. Chapter 3 Biogeochemical Processes Controlling the Fate and Transport of Arsenic. Implications for South and Southeast Asia. Adv. Agron. 2009, 104, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, N.; Jung, W.; Halajnia, A.; Lakzian, A.; Kabra, A.N.; Jeon, B.H. Removal of Arsenate and Arsenite from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption on Clay Minerals. Geosystem Eng. 2015, 18, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Pramanik, S.; Singh, P.; Mondal, P.; Chatterjee, D.; Nriagu, J. Arsenic in Groundwater of West Bengal, India: A Review of Human Health Risks and Assessment of Possible Intervention Options. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgorski, J.; Berg, M. Global Threat of Arsenic in Groundwater. Science (80-. ). 2020, 368, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. International Standard for Drinking Water Guidelines for Water Quality. 2011, 1–2.

- Páez-Espino, D.; Tamames, J.; de Lorenzo, V.; Cánovas, D. Microbial Responses to Environmental Arsenic. BioMetals 2009, 22, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, G.; Santos, S.; Boaventura, R.; Botelho, C. Arsenic and Antimony in Water and Wastewater: Overview of Removal Techniques with Special Reference to Latest Advances in Adsorption. J. Environ. Manage. 2015, 151, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Zhou, D. Strengthening Arsenite Oxidation in Water Using Metal-Free Ultrasonic Activation of Sulfite. Chemosphere 2021, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobya, M.; Soltani, R.D.C.; Omwene, P.I.; Khataee, A. A Review on Decontamination of Arsenic-Contained Water by Electrocoagulation: Reactor Configurations and Operating Cost along with Removal Mechanisms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Ponprasath, R.; Rohan, K.; Jahnavi, N. An Effective Separation of Toxic Arsenic from Aquatic Environment Using Electrochemical Ion Exchange Process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigorria, E.; Cano, L.; Sapag, K.; Alvarez, V. Removal Efficiency of As(III) from Aqueous Solutions Using Natural and Fe(III) Modified Bentonites. Environ. Technol. (United Kingdom) 2022, 43, 3728–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silerio-Vázquez, F.; Proal Nájera, J.B.; Bundschuh, J.; Alarcon-Herrera, M.T. Photocatalysis for Arsenic Removal from Water: Considerations for Solar Photocatalytic Reactors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61594–61607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigorria, E.; Cano, L.; Alvarez, V.A. Nanoclays as Eco-Friendly Adsorbents of Arsenic for Water Purification. Handb. Nanomater. Nanocomposites Energy Environ. Appl. Vol. 1-4 2021, 1, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroni, A.L.P.F.; de Lima, C.R.M.; Pereira, M.R.; Fonseca, J.L.C. Tetracycline Adsorption on Chitosan: A Mechanistic Description Based on Mass Uptake and Zeta Potential Measurements. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2012, 100, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Shi, Y.; He, Q.; Chen, J.; Wan, D. Magnetic Spent Bleaching Earth Carbon (Mag-SBE@C) for Efficient Adsorption of Tetracycline Hydrochloride: Response Surface Methodology for Optimization and Mechanism of Action. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Manjaiah, K.M.; Datta, S.C.; Yadav, R.K.; Sarkar, B. Inorganically Modified Clay Minerals: Preparation, Characterization, and Arsenic Adsorption in Contaminated Water and Soil. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 147, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, S.K.; Cheong, K.Y.; Salimon, J. Surface-Active Physicochemical Characteristics of Spent Bleaching Earth on Soil-Plant Interaction and Water-Nutrient Uptake: A Review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 140, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.T.; Chang, Y.M.; Lai, C.W.; Lo, C.C. Adsorption of Ethyl Violet Dye in Aqueous Solution by Regenerated Spent Bleaching Earth. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 289, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eko Saputro, K.; Siswanti, P.; Wahyu Nugroho, D.; Ikono, R.; Noviyanto, A.; Taufiqu Rochman, N. Reactivating Adsorption Capacities of Spent Bleaching Earth for Using in Crude Palm Oil Industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Mu, B.; Zheng, M.; Wang, A. One-Step Calcination of the Spent Bleaching Earth for the Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal Ions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yuan, K.; Yin, K.; Zuo, S.; Yao, C. Clay-Activated Carbon Adsorbent Obtained by Activation of Spent Bleaching Earth and Its Application for Removing Pb(II) Ion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Wan, H.; Shi, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J. Enhanced Removal of Sb(V) by Iron-spent Bleaching Earth Carbon Binary Micro-electrolysis System: Performance and Mechanism. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 2181–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S. Effective Adsorption of Bisphenol A from Aqueous Solution over a Novel Mesoporous Carbonized Material Based on Spent Bleaching Earth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 40035–40048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Yoza, B.A.; Hao, K.; Li, Q.X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S.; Chen, C. A Char-Clay Composite Catalyst Derived from Spent Bleaching Earth for Efficient Ozonation of Recalcitrants in Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wan, D.; Zhao, J.; He, Q.; Liu, Y. Synergistic Adsorption and Advanced Oxidation Activated by Persulfate for Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride Using Iron-Modified Spent Bleaching Earth Carbon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 24704–24715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasri, D.A.; Rhadfi, T.; Atieh, M.A.; McKay, G.; Ahzi, S. High Performance Hydroxyiron Modified Montmorillonite Nanoclay Adsorbent for Arsenite Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 335, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, L.; Tahmasebpoor, M.; Khatamian, M.; Divband, B. Arsenic Removal from Aqueous Solutions Using Iron Oxide-Modified Zeolite: Experimental and Modeling Investigations. AUT J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 5, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, N.L.M.; Hoang Van, D.; Duong, T.; Tinh, M.X.; Khieu, D.Q. Adsorption of Arsenate from Aqueous Solution onto Modified Vietnamese Bentonite. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuutijärvi, T.; Lu, J.; Sillanpää, M.; Chen, G. As(V) Adsorption on Maghemite Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 1415–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asere, T.G.; Stevens, C. V.; Du Laing, G. Use of (Modified) Natural Adsorbents for Arsenic Remediation: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftabtalab, A.; Rinklebe, J.; Shaheen, S.M.; Niazi, N.K.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Schaller, J.; Knorr, K.-H. Review on the Interactions of Arsenic, Iron (Oxy)(Hydr)Oxides, and Dissolved Organic Matter in Soils, Sediments, and Groundwater in a Ternary System. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Zong, L.; Mu, B.; Kang, Y.; Wang, A. Attapulgite/Carbon Composites as a Recyclable Adsorbent for Antibiotics Removal. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.A.; Kumar, R.; Halawani, R.F.; Al-Mur, B.A.; Seliem, M.K. Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Loaded Bentonite/Sawdust Interface for the Removal of Methylene Blue: Insights into Adsorption Performance and Mechanism via Experiments and Theoretical Calculations. Water 2022, 14, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Yu, S. Characterization of Co(II) Removal from Aqueous Solution Using Bentonite/Iron Oxide Magnetic Composites. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011, 290, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Wang, A. One-Pot Fabrication of Multifunctional Superparamagnetic Attapulgite/Fe3O4/Polyaniline Nanocomposites Served as an Adsorbent and Catalyst Support. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, G.; Wang, Y.; Ona-Nguema, G.; Juillot, F.; Calas, G.; Menguy, N.; Aubry, E.; Bargar, J.R.; Brown, G.E. EXAFS and HRTEM Evidence for As(III)-Containing Surface Precipitates on Nanocrystalline Magnetite: Implications for as Sequestration. Langmuir 2009, 25, 9119–9128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Ye, Z.; Hmidi, N. High-Performance Iron Oxide–Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Adsorbents for Arsenic Removal. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 522, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.K.; Jiang, S.J. Synthesis of Magnetically Separable and Recyclable Magnetic Nanoparticles Decorated with β-Cyclodextrin Functionalized Graphene Oxide an Excellent Adsorption of As(V)/(III). J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 237, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Bezbaruah, A.N. Comparative Study of Arsenic Removal by Iron-Based Nanomaterials: Potential Candidates for Field Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, E.; Mäkinen, M.; Rengaraj, S.; Natarajan, G.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sillanpää, M. Lepidocrocite and Its Heat-Treated Forms as Effective Arsenic Adsorbents in Aqueous Medium. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 180, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Kumari, A.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, B. Arsenic Removal from Water by Adsorption onto Iron Oxide/Nano-Porous Carbon Magnetic Composite. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzielwana, R.; Gitari, M.W.; Ndungu, P. Performance Evaluation of Surfactant Modified Kaolin Clay in As(III) and As(V) Adsorption from Groundwater: Adsorption Kinetics, Isotherms and Thermodynamics. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, Y.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Malik, I.; Tyagi, A.; Ramkumar, J.; Kar, K.K. Insights of Arsenic (III/V) Adsorption and Electrosorption Mechanism onto Multi Synergistic (Redox-Photoelectrochemical-ROS) Aluminum Substituted Copper Ferrite Impregnated RGO. Chemosphere 2021, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, R.; Qu, J. Adsorption Behavior and Mechanism of Arsenate at Fe–Mn Binary Oxide/Water Interface. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 168, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullen, J.C.; Saleesongsom, S.; Gallagher, K.; Weiss, D.J. A Revised Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic Model for Adsorption, Sensitive to Changes in Adsorbate and Adsorbent Concentrations. Langmuir 2021, 37, 3189–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Azaiez, J.; Hill, J.M. Erroneous Application of Pseudo-Second-Order Adsorption Kinetics Model: Ignored Assumptions and Spurious Correlations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 2705–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; DasGupta, S.; Basu, J.K.; De, S. Adsorption of Arsenite Using Natural Laterite as Adsorbent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 55, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Li, B.; Feng, S.X.; Mi, X.M.; Jiang, J.L. Adsorption of Cr(VI) and As(III) on Coaly Activated Carbon in Single and Binary Systems. Desalination 2009, 249, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Hasegawa, H.; Maki, T.; Ueda, K. Adsorption of Inorganic and Organic Arsenic from Aqueous Solutions by Polymeric Al / Fe Modified Montmorillonite. 2007, 56, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Din, S.U.; Naeem, A.; Tasleem, S.; Alum, A.; Mustafa, S. Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamics Studies of Arsenate Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions onto Iron Hydroxide. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 3234–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, Y.; Remes, A.; Reyna, A.; Martinez, D.; Villarreal, J.; Ramos, H.; Trevino, S.; Tamez, C.; Martinez, A.; Eubanks, T.; et al. Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Activation Energy Studies of the Sorption of Chromium(III) and Chromium(VI) to a Mn3O4 Nanomaterial. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 254, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebelegi, A.N.; Ayawei, N.; Wankasi, D. Interpretation of Adsorption Thermodynamics and Kinetics. Open J. Phys. Chem. 2020, 10, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuabonah, E.I.; Adebowale, K.O.; Olu-Owolabi, B.I. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies of the Adsorption of Lead (II) Ions onto Phosphate-Modified Kaolinite Clay. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 144, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Deng, S.; Yu, G.; Huang, J.; Lim, V.C. As(V) and As(III) Removal from Water by a Ce–Ti Oxide Adsorbent: Behavior and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 161, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Ma, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qiao, N.; Hu, M.; Ma, H. Adsorption of Methylene Blue onto Fe3O4/Activated Montmorillonite Nanocomposite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 119, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Element content (%) | ||||

| C | O | Fe | Si | Al | |

| SBE | 22.21 | 65.88 | 0.36 | 7.33 | 3.29 |

| SBE/C 350 oC | 11.81 | 64.76 | 1.84 | 15.49 | 2.2 |

| SBE/C 400 oC | 13.86 | 64.53 | 3.93 | 10.89 | 3.94 |

| SBE/C 450 oC | 12.46 | 65.74 | 0.69 | 16.23 | 3.07 |

| SBE/C 500 oC | 8.57 | 65.17 | 1.68 | 17 | 4.58 |

| SBE/C 550 oC | 9.69 | 65.23 | 1.46 | 15.11 | 5.55 |

| Fe-SBE/C 350 oC | 13.34 | 62.41 | 12.3 | 10.1 | 1.1 |

| Fe-SBE/C 400 oC | 10.82 | 61.65 | 14.25 | 11.17 | 1.41 |

| Fe-SBE/C 450 oC | 10.08 | 62.98 | 10.42 | 14.73 | 1.11 |

| Fe-SBE/C 500 oC | 9.84 | 59.36 | 20.98 | 6.82 | 1.88 |

| Fe-SBE/C 550 oC | 9.81 | 61.58 | 14.62 | 11.76 | 1.21 |

| Fe-SBE/C 500 oC after Adsorption | 10.74 | 60.52 | 17.44 | 8.32 | 1.91 |

| Materials | Specific surface area (m2 g-1) | Total Pore volume(cm3 g-1) | Average pore size (nm) |

| SBE | 191.19 | 1.4716 | 30.789 |

| SBE/C 500 oC | 3029.9 | 6.913 | 9.1266 |

| Fe-SBE/C 500 oC | 2865.7 | 8.6964 | 12.138 |

| Type of Kinetic | Parameter | As(III) | As(V) |

| Pseudo-first-order | qeexp (µg g-1) | 36.8077 | 27.9422 |

| qecal (µg g-1) | 33.898 | 25.215 | |

| k1 | 0.1064 | 0.0536 | |

| R2 | 0.8396 | 0.9354 | |

| Elovich model | α (µg g-1 min) | 0.1852 | 0.2039 |

| β (µg g-1) | 1.7652 | 0.3402 | |

| R2 | 0.9971 | 0.9672 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion model 1 | Kdiff (µg g-1/2)-1 | 4.6063 | 3.4548 |

| C (µg g-1) | 5.5599 | 0.2689 | |

| R2 | 0.9568 | 0.9797 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion model 2 | Kdiff (µg g-1/2)-1 | 0.8527 | 1.3477 |

| C (µg g-1) | 25.8081 | 10.3075 | |

| R2 | 0.9318 | 0.9671 |

| Type of Isotherm | Parameters | As(III) | As(V) |

| Langmuir | Qmax (µg g-1) | 202.61 | 187.61 |

| KL (L µg-1) | 0.0173 | 0.0078 | |

| R2 | 0.988 | 0.9901 | |

| Freundlich | KF | 7.2754 | 3.1061 |

| 1/n | 0.6486 | 0.7069 | |

| R2 | 0.978 | 0.9722 | |

| Temkin | B (J mol-1) | 26.8809 | 32.0069 |

| A (L g-1) | 0.5094 | 0.1203 | |

| R2 | 0.8830 | 0.9683 |

| Thermodynamic Parameter | Temperature | As(III) | As(V) |

| ΔGo (kJ mol-1) | 25 oC | -2.298 | -8.472 |

| 35 oC | -2.576 | -8.825 | |

| 40 oC | -2.677 | -9.015 | |

| ΔHo (kJ mol-1) | 5.351 | 2.266 | |

| ΔSo (J mol-1K-1) | 25.682 | 36.0276 | |

| Ea (kJ mol-1) | 65.799 | 21.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).