1. Introduction

Water bodies’ pollution from heavy metals is a serious environmental problem on a global scale [

1]. These metals, including lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic, have diverse origins in industry, mining, agriculture, and urban waste. These tend to accumulate in sediments and living organisms, which can have devastating consequences for aquatic systems, wildlife, and human health [

2].

Aquifers and groundwater contamination by arsenic (As) has emerged as a concern in recent years due to its high toxicity and hazardousness to human health and the environment [

3]. Arsenate As(V) is an inorganic form of arsenic (As) that can introduce water bodies from natural sources and human activities, such as mining and agriculture.

Drinking water chronic exposure to arsenate has been linked to cancer development [

4,

5] and neurological disorders [

6,

7]. Therefore, managing and reducing arsenate contamination is imperative to preserve the aquatic ecosystem’s health and ensure a safe and sustainable water supply.

Currently, several technologies based on coagulation/filtration, biological oxidation, electrochemical oxidation, and ion exchange processes are reported for As removal from groundwater intended for human consumption [

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, the need for further studies to develop techniques that are accessible to the population and guarantee adequate water quality has made the use of pure or modified adsorbents an efficient tool for these purposes [

12,

13,

14].

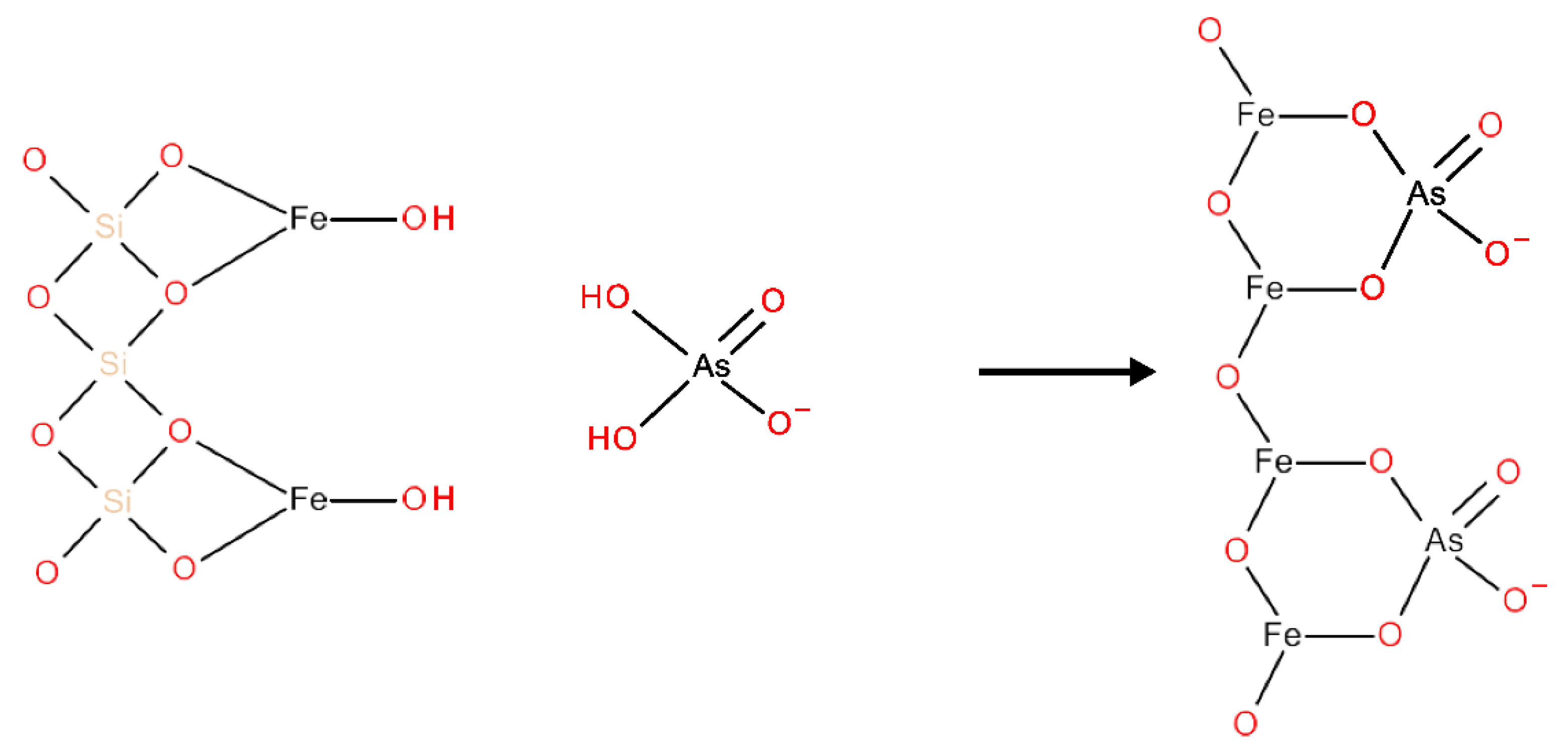

The principle of adsorption technology in the case of iron oxide-coated ignimbrite for arsenic removal is based on the solid chemical affinity between the iron oxide’s functional groups and arsenic ions, particularly arsenate ions (As(V)). Iron oxide contains hydroxyl groups that can bind with arsenic through surface complexation, where arsenate ions replace the hydroxyl groups on the iron oxide surface. This creates a stable bond that effectively removes arsenic from water, making it a highly efficient method for reducing arsenic contamination [

15].

Regarding adsorption efficiency, two key factors are crucial: surface area and porosity. Adsorbents with a high surface area and porous structure, like ignimbrite, offer more active sites for binding arsenic ions, enhancing adsorption capacity. Surface modification also plays a significant role. The iron oxide coating on ignimbrite significantly enhances its adsorptive properties by increasing selectivity for arsenic ions (specifically As(V)). This modification improves the affinity for arsenic and influences adsorption kinetics, allowing faster ion exchange and maximum adsorption capacity, enabling the adsorbent to capture more significant amounts of arsenic. This makes the modified ignimbrite a highly effective material for arsenic removal in water treatment [

16,

17].

Adsorbents can trap and retain contaminants, such as As, through chemical or physical interactions. Pure adsorbents, such as iron oxide and activated carbon, are widely used for As removal in water treatment systems [

14]. In addition, modified adsorbents, which have been specifically designed and treated to increase their adsorption capacity, can also work in As removal. These materials can be modified by metal oxide compounds, clays, and nanoparticles, which improve their efficiency and selectivity for arsenic capture [

12]. In this way, these modified adsorbents can effectively address arsenic contamination in water supplies, ensuring safe drinking water and public health protection.

Ignimbrite is a volcanic stone of igneous origin with a white or cream color and porous texture. It has traditionally been used as a building material for its durability, strength, and distinctive aesthetics in the Arequipa region of southern Peru [

18]. The mineralogical composition of this material has been reported by Lebti et al. (2006). In particular, La Joya ignimbrite is one of the most important outcrops in this region. It has the highest quartz (SiO

2) and sanidine (KAlSi

3O

8) content of all ignimbrites in Arequipa [

19]. Due to its characteristics and properties, enhanced by its coating with iron oxides, it has been proposed as an adsorbent for contaminated water remediation by heavy metals.

Iron oxides, such as haematite, goethite, and magnetite, are widely used as effective adsorbents in heavy metal removal from polluted waters [

13,

20,

21]. Iron oxides possess functional groups on their surface that can interact with metal ions, allowing chemical bond formation and metal retention in solution [

22]. In addition, iron oxides are also attractive for these purposes due to their availability, affordability, and regenerative capacity, making them a sustainable option for heavy metal removal in water pollution management.

This research proposes using iron oxide-coated ignimbrite as an adsorbent material for As (V) removal in an aqueous solution to obtain an effective, accessible, and economical method for water purification intended for human consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ignimbrite Sampling

Ignimbrite samples were collected from a prominent natural outcrop in Arequipa, which has been used in construction and ornamentation for centuries [

23,

24]. The sampling point was located at the geographical coordinates 16°22’14.9” S, 71°32’03.5” W, at 2386 m.a.s.l. altitude, in the Chilina locality, Alto Selva Alegre district, on the Chili River’s east bank.

2.2. Ignimbrite’s Physicochemical Characterization and Mineralogical Composition

2 kg ignimbrite sample was characterized after being disintegrated and sieved into 75 µm - 150 µm, 150 µm - 425 µm, and 425 µm - 850 µm particles. Electrical conductivity (EC), pH, residual moisture, and organic matter content (OM) were determined. In addition, elemental analysis by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was carried out to determine mineralogical composition and metal presence in ignimbrite.

2.3. Ignimbrite Modification by Coating with Iron Oxides

Ignimbrite’s iron oxide coating was performed according to the procedure proposed by Thirunavukkarasu et al. [

25], which consisted of a pre-conditioning and two coating stages. Conditioning consisted of immersing the ignimbrite in a 0.1 M nitric acid solution for 24 h. After triple rinse with distilled water, the sample was dried at 383 K ± 1 K for 20 h.

In the initial stage of the coating process, 7.5 g of Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O was dissolved in 25 mL of distilled water. Subsequently, 2.5 mL of 10 M NaOH was added, and the mixture was continuously homogenized, forming a reddish-brown gelatinous precipitate indicative of Fe(OH)₃. The ignimbrite sample was then incorporated into the solution, and the mixture was homogenized for 10 minutes. The solution was heated for 4 hours at 383 K ± 1 K, followed by an additional 3 hours at 823 K ± 1 K. Finally, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature.

In the second phase of the process, 25 g of Fe(NO3)3∙9H2O were dissolved in 22 mL of distilled water, and 5 mL of 10 M NaOH were added. While homogenizing the mixture, the previously obtained solution (first stage of the coating process) was added, stirring constantly. The mixture was then heated to 383 K ± 1 K for 20 h. After cooling to room temperature, the new solution was mechanically disaggregated and sieved to obtain 150 µm - 425 µm particles. After three repetitions of heating/cooling phases of 4 h at 383 K ± 1 K in each cycle, the solution was cooled for 20 hours at room temperature.

2.4. Quantitative As(V) Analysis by Voltammetry

Voltammetry offers the ability to determine arsenic in its various forms, including arsenite As (III), total As, and As (V), by a potential difference [

26]. However, since As (V) is electroinactive, a prior reduction of As (V) to As (III) is required to determine total As.

Sodium arsenate (Na2HAsO4∙7H2O) solutions were used to reduce As (V) to As (III) and, therefore, to quantify the analyte in the samples. 2 mL of 0.1 M L-cysteine solution was used as the reducing agent, and 1 M HCl was added to the sample, based on the procedure proposed by He et al. (2007). Then, the mixture was heated at 363 K ± 1 K for 10 min in a water bath to accelerate the reduction, avoiding sample loss by evaporation. Subsequently, the solution was cooled to room temperature, and the final volume was adjusted to 10 mL.

As (III) determination required the use of 1 M HCl solution and the presence of Cu (II) and Se (IV) in the voltammetric cell for proper analysis. The voltammetric technique needed to be validated through linearity, precision, accuracy, limit of detection, and limit of quantification parameters, as stated in USP 37 [

27].

2.5. As (V) Removal by Iron Oxide-Coated Ignimbrite

Batch experiments were conducted to analyze sodium arsenate solutions at the beginning and the end of the As (V) adsorption process with iron oxide-coated ignimbrite. An eight-station adsorption unit with thermoregulation, operating between 10 - 40°C, facilitated the experiments by controlling the process through a hot/cold water bath system and a circulation pump. Paddles rotary motion was induced by a pulley system, with a 100 - 450 rpm speed range.

50 mL of As (V) solution (from Na

2HAsO

4·7H

2O) was mixed with the adsorbent (at different volumes) in 100 mL beakers, stirring constantly. Specific interval measurements were made and analyzed using voltammetry after centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min. The adsorbed arsenic amount on the iron oxide-coated ignimbrite was calculated by comparing the initial concentrations and sample concentrations taken at different times according to the following equation:

Likewise, the adsorbed arsenic amount on the iron oxide coated ignimbrite at equilibrium was calculated with the following equation:

Where

qe and

qt are the adsorption capacity of the metalloid at equilibrium and at a defined time t, respectively (mg·g

-1);

C0 is the initial concentration of arsenic (mg·L

-1);

Ce and

Ct are the arsenic concentrations at equilibrium and at a defined time t, respectively (mg·L

-1);

V is the solution volume (mL) and

M is the adsorbent mass (g). Adsorption process efficiency was expressed in As (V) removal percentage, given by the following equation:

Where Cf is the As (V) final concentration after contact time with the adsorbent, and C0 is the As (V) initial concentration. Both the As (V) removal percentage and the adsorption capacity were calculated regarding four variables: adsorbent mass (g), As (V) initial concentration (g·L-1), contact time, and temperature.

2.6. Equilibrium Adsorption Study

Six different As (V) initial concentrations were evaluated between 1.31 and 32.72 mg·L

-1 range. These solutions were prepared from a Na

2HAsO

4·7H

2O stock solution dilution with a 2400 mg·L

-1 As (V) concentration. 47 mL of each As (V) solution mixed with 0.15 g ignimbrite were used, keeping them under constant stirring. Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were used to understand the adsorption mechanism and the arsenic-adsorbent interaction [

28,

29,

30]. The following equation can describe the linear form of Langmuir’s isotherm:

Where qe is the arsenic adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg·g-1); Ce is As (V) concentration at equilibrium (mg·L-1), kL is Langmuir’s isotherm constant (L·mg-1), which is related to the adsorption free energy and qm is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg·g-1).

The following equation gives the linear form of Freundlich’s isotherm:

Where

qe is the arsenic adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg·g

-1),

Ce is As (V) concentration at equilibrium (mg·L

-1),

kf is Freundlich’s isotherm constant, which is related with the adsorption process efficiency;

n is the heterogeneity factor, a dimensionless variable indicative of the adsorption process favorability. If the

n value is 0-10, it indicates chemisorption [

31].

The Langmuir model assumes homogeneous monolayer adsorption on the adsorbent surface with a finite number of identical interaction sites, while the Freundlich model is empirical and allows for multilayer adsorption [

25].

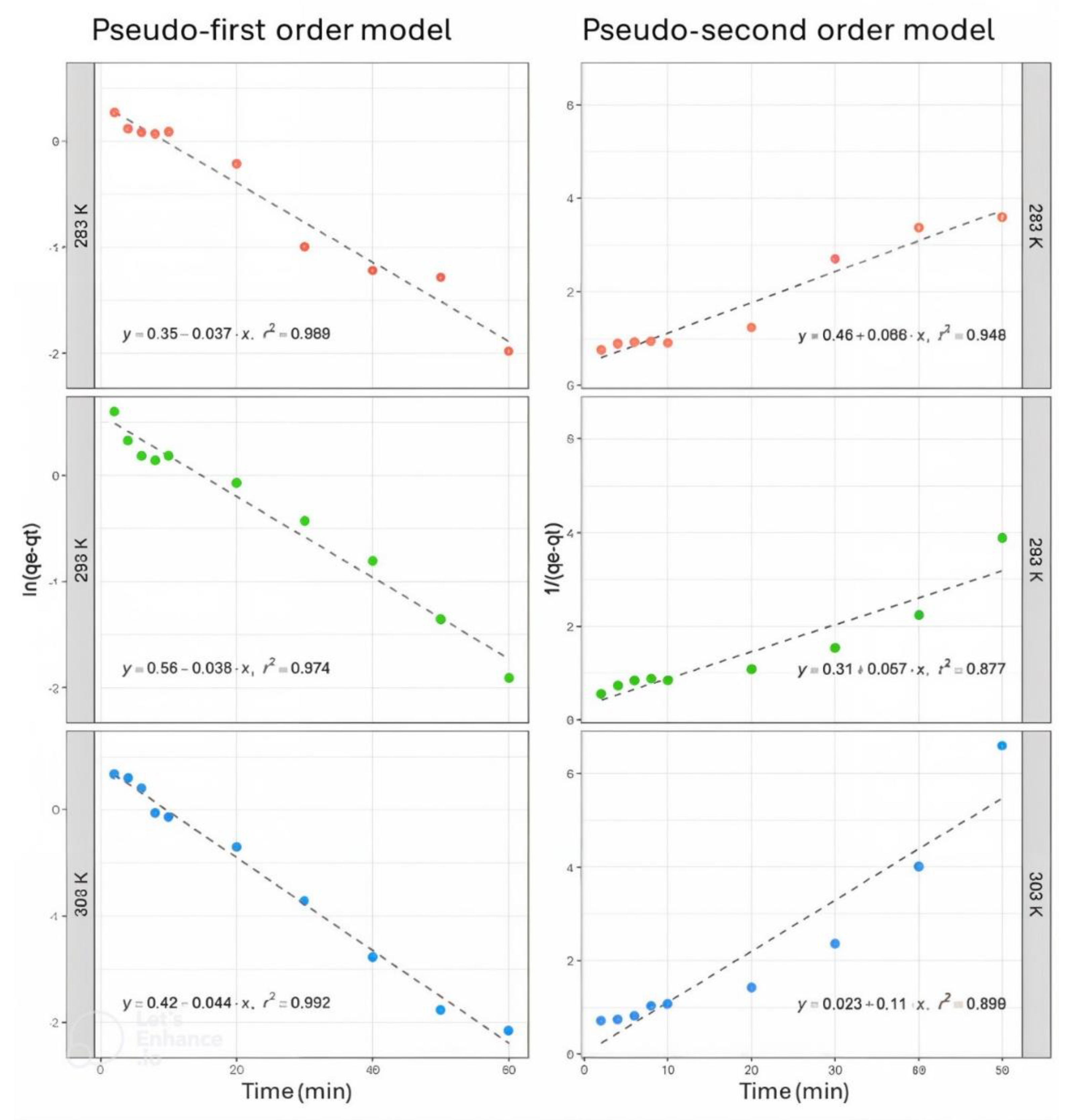

2.7. As (V) Adsorption Kinetics

As (V) adsorption kinetics were evaluated at 283 K, 293 K, and 303 K. 50 mL As (V) 15 mg·L-1 stock solution and 0.15 g iron oxide-coated ignimbrite were used. Readings were taken at different times for 140 min. To evaluate the adsorption process’ kinetic order, pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models were applied, whose equations are expressed in the linear form below:

Pseudo-first-order model:

Where qe and qt are the adsorption capacities at equilibrium and at defined time t, respectively (mg·g-1), and k1t is the pseudo-first-order adsorption rate constant (1∙min-1).

Pseudo-second-order model:

Where qe and qt are the adsorption capacities at equilibrium and at a defined time t, respectively (mg·g-1), and k2t is the pseudo-second-order adsorption rate constant (g·mg min-1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ignimbrite’s Physicochemical Properties and Mineral Composition

Ignimbrite’s particles were 150-425 µm and showed a fine silty-sandy texture, whitish color, and very low solubility. Regarding chemical characteristics, its pH was 8.1, EC was 1.27 dS∙m-1, residual humidity was 0.23% and OM was 0.33%. Carbonate presence is estimated due to the effervescence observed upon adding 0.1 M HCl.

Metal determination by ICP-OES showed the presence of 11 elements (

Table 1). Na and K presented the highest concentration. Thus, some heavy metals (Ba, Cu, Fe, Mo, Sr, Ti) were also determined. Fe and Ti determination suggests the presence of these minerals’ oxides.

3.2. Ignimbrite Modification by Coating with Iron Oxides

A 25 g ignimbrite sample was coated with iron oxides, a product made from ferric salt precipitate. These oxides appear in crystalline forms such as goethite (α-FeOOH), hematite (α-Fe

2O

3), ferrihydrite (Fe

5HO

8∙4H

2O), and lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), which differ from each other in chemical structure, composition, and physical characteristics [

32,

33].

Fe(OH)

3 formation in the ignimbrite immersion solution facilitates dehydration and dehydroxylation reactions during heating that generates α-FeOOH and α-Fe

2O

3 as a final product (10). Possible reactions that take place are detailed below:

Along with their structures, goethite, and hematite present isostructures of other metal oxides: diaspore (α-AlOOH) for goethite and corundum (α-Al

2O

3) for hematite [

25] Furthermore, this oxide crystalline form presents hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structures, implying a cation enclosed by anions forming a hexagonal structure. In goethite, each Fe atom is surrounded by three O

-2 and three OH

— to produce FeO

3(OH)

3 octahedra. In the hematite case, each Fe atom is surrounded octahedrally by six O atoms [

34,

35].

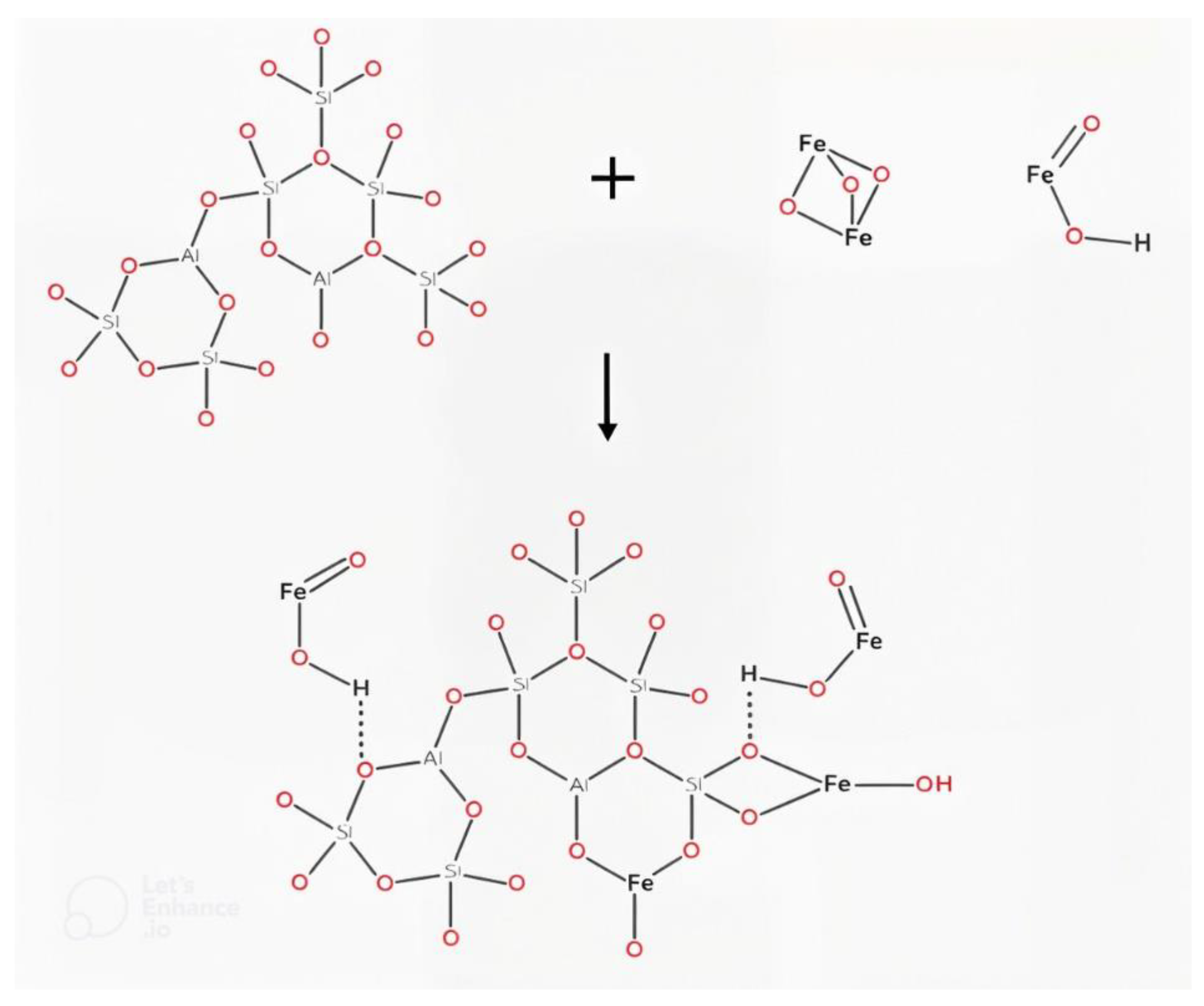

A possible reaction mechanism is proposed considering iron oxide structures formed during the ignimbrite coating process and its mineralogical composition (

Figure 1).

Since goethite and hematite’s specific surface areas are in the 8-200 and 2-90 m

2∙g

-1 ranges, respectively [

34], it is assumed that the coated ignimbrite has a specific surface area in the same range.

At the end of ignimbrite’s iron oxide coating process, an obvious change in its color was noticed, changing to a reddish-orange tone. This fact constituted physical proof of the modification’s success. Furthermore, a 0.119 to 17.729 g·kg-1 increase in Fe concentration was evidenced, so a successful coating was deduced. On the other hand, a Na concentration increase was observed, which can be explained by the NaNO3 formation in the coating solution as a reaction product carried out during this process.

3.3. As (V) Removal by Iron Oxide-Coated Ignimbrite and As (V) Adsorption Capacity

3.3.1. Iron Oxide Coated Ignimbrite Adsorbent Mass Effect

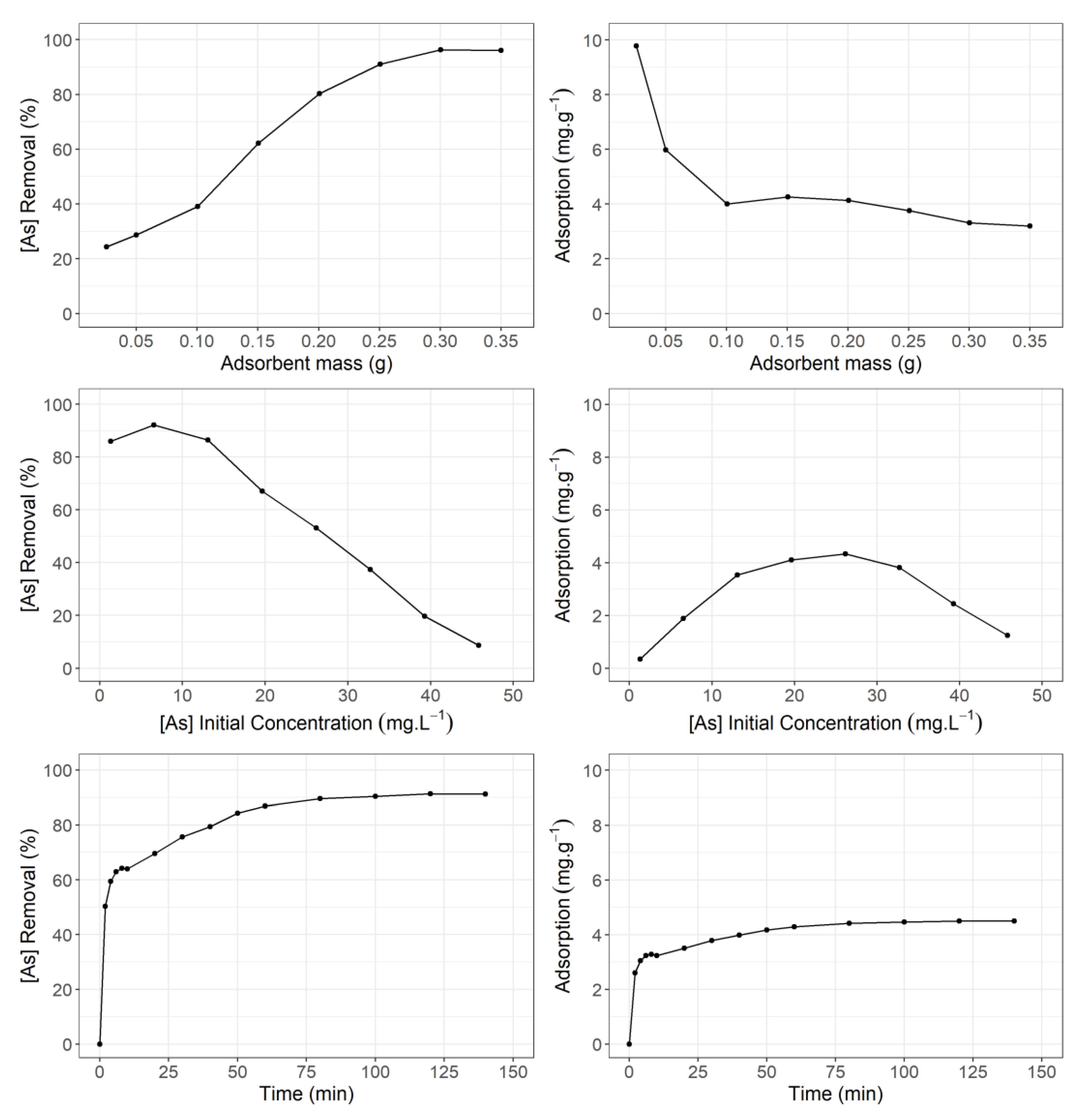

Arsenic (V) removal percentages between 24.39% and 96.01% were observed in 0.025 g to 0.35 g of adsorbent interval (

Figure 2). This is attributable to the increased adsorbent surface area in contact with the As (V) solution. The adsorption capacity decreased from 9.78 to 3.19 mg·g

-1 for the same adsorbent mass range, suggesting that this behavior could indicate multilayer adsorption at fewer particles. However, it is important to clarify that the percentage removal is an extensive variable and depends on the adsorbent mass. The observed decrease in arsenic uptake is attributed to the increase in the number of available adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface, which implies that a major quantity of adsorbate is needed to achieve saturation of the adsorbent. Moreover, it is crucial to highlight that multilayer adsorption is not feasible under tested conditions. According to these results, a 0.15 g adsorbent value was set for subsequent tests.

3.3.2. As (V) Ion Concentration Effect

A 2 h period assay at 293 K ± 1 K was performed to evaluate the As (V) concentration effect on its removal percentage and adsorption capacity, using 0.15 g adsorbent. As (V) removal percentage showed a slight increase for As (V) concentrations between 1 and 6.5 mg·L

-1, from where it decreased from 90% to 8.6% at a 45.8 mg·L

-1 As (V) initial concentration (

Figure 2). This finding may be due to the limited surface area of the modified ignimbrite particles that adsorb As (V) ions in the solution. On the other hand, in terms of adsorption capacity, an adsorption peak of 4.33 mg·g

-1 occurs at a 26.2 mg·L

-1 As (V) initial concentration. With these results, it was decided to use 15 mg·L

-1 As (V) stock solutions for subsequent investigations.

3.3.3. Contact Time Effect

50 mL of a 15 mg·L

-1 As (V) stock solution and 0.15 g adsorbent were used at 293 K ± 1 K temperature to determine the contact time effect in As (V) removal and adsorption capacity. The measurements were carried out at different periods for 140 min. However, a 60-minute contact period was sufficient to achieve equilibrium (

Figure 2). These results suggest a two-step mechanism: a very fast As (V) initial adsorption in the first 10 min, followed by a slower period until equilibrium. Over 85% of As (V) removal occurred in the first 60 minutes. The maximum removal percentage (91.28%) was reached at 120 minutes of contact time.

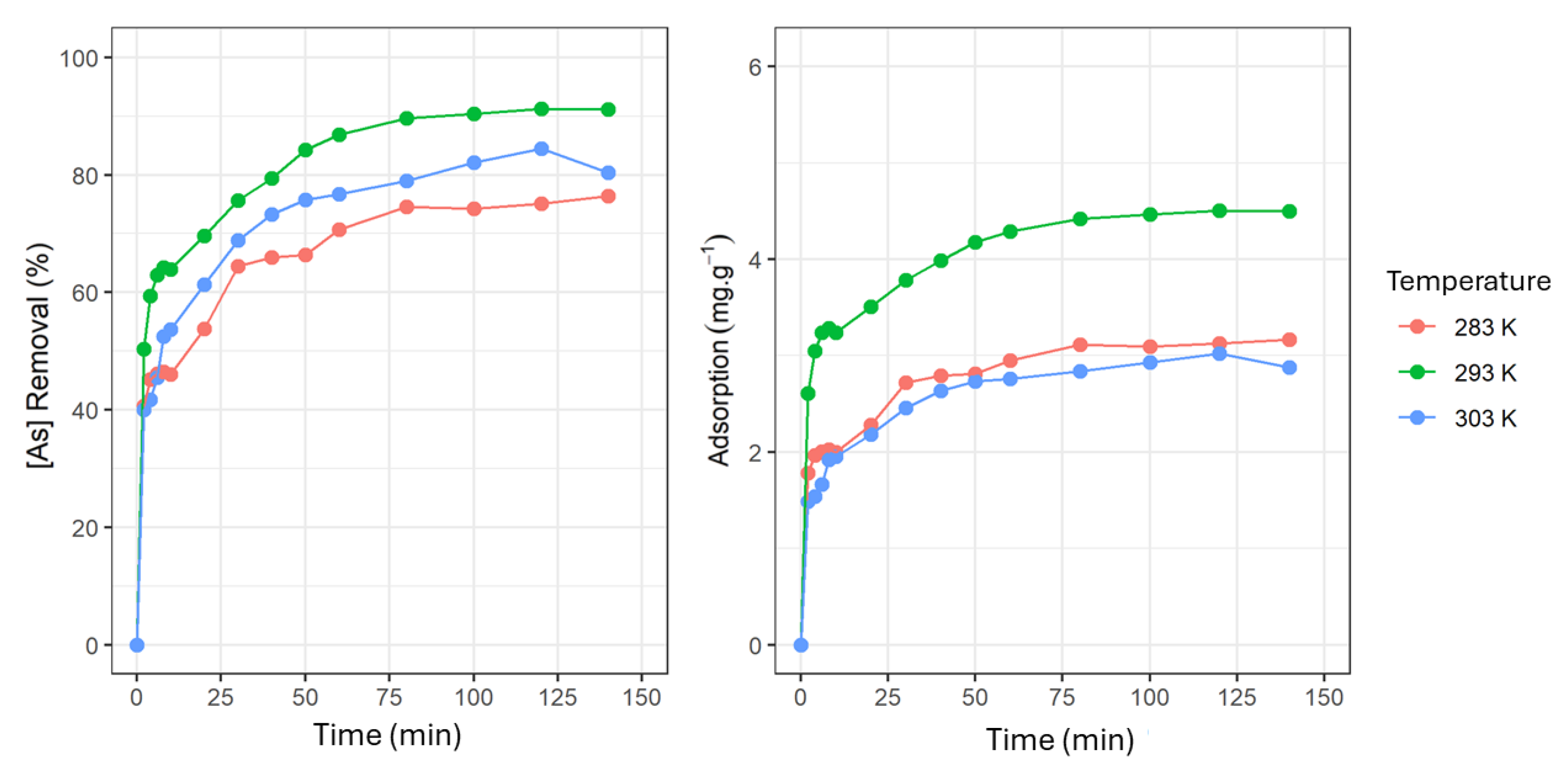

3.3.4. Temperature Effect

50 mL of a 15 mg·L

-1 As (V) stock solution and 0.15 g of adsorbent were used to compare 283 K, 293 K, and 303 K ± 1 K temperature effects. The highest removal percentage (91.18%) was registered at 293 K (

Figure 3). Likewise, at 293 K, the highest adsorption capacity value (4.50 mg·g

-1) was reached. It is noted that to optimize the process, it is advisable to maintain a temperature of 293 K ± 1 K.

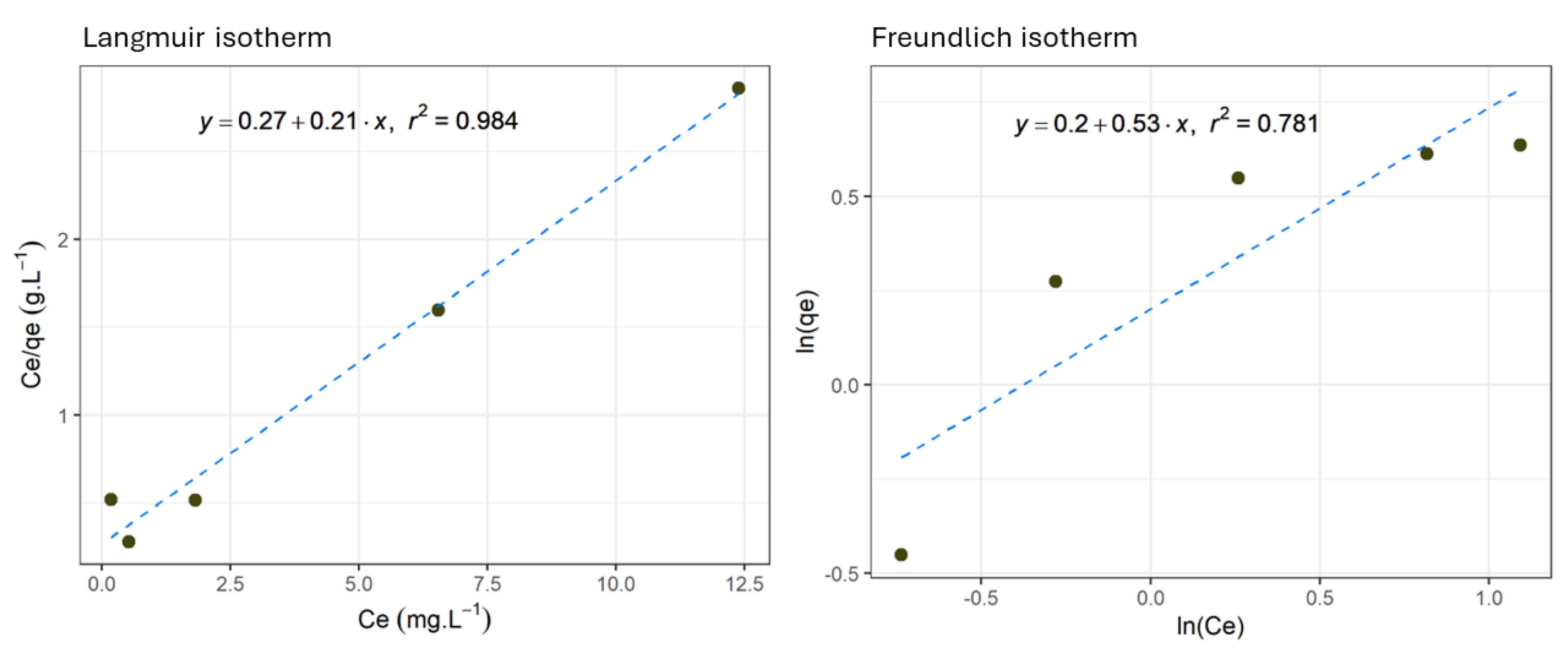

3.4. Adsorption Balance

To elucidate the adsorption mechanism, as well as the interaction between As (V) and the adsorbent under study, Langmuir’s and Freundlich’s isotherm models were used [

29,

30]. The test took place using a 15 g / 47 mL adsorbent concentration for 120 minutes at 293 K ± 1 K. Isotherm constants and correlation coefficients were obtained (

Table 2). These results showed that the Langmuir model presented a higher correlation coefficient (R

2 = 0.9855) than the Freundlich model (R

2 = 0.7268) (

Figure 4), indicating that the experimental data best fit a monolayer-type adsorption model. According to Langmuir’s isotherm, the maximum adsorption capacity is 4.84 mg·g

-1, a close value to the experimental one (4.33 mg·g

-1) found in a previous study.

Although the Freundlich model does not fit the experimental data and the Langmuir model, it is noteworthy that the n value falls within the range of 1-10. This indicates that the adsorption process is likely favorable under the studied conditions, suggesting a chemisorption process. Chemisorption, unlike physisorption, involves stronger chemical bonds between the adsorbent and adsorbate, which can explain the higher efficiency of the adsorption. These findings align with studies by Hsu et al. [

36] and Thirunavukkarasu et al. [

25], where similar n values were also associated with favorable adsorption processes.

3.5. Adsorption Kinetics

Experimental

qe values obtained in the kinetic study showed that the highest adsorbent capacity (4.44 mg·g

-1) occurs at 293 K, followed in a decreasing manner by 3.09 mg·g

-1 and 2.89 mg·g

-1 at 283 K and 303 K, respectively. Correlation coefficients showed that for the three studied temperatures, the most suitable model for experimental data was the pseudo-first-order model (

Figure 5). It was also observed that the R

2 value increases as the system temperature increases (0.9685 ˂ 0.9736 ˂ 0.9917). This same event happened with the speed constant value

k1, while the calculated

qe values are below the experimental

qe values. On the other hand, the R

2 values for the pseudo-second-order model showed that at 293 K, the experimental data fits this model better than at 283 K and 303 K (

Figure 5). Likewise, speed constant

k2 showed similar values for 283 K and 303 K temperatures (0.0698 and 0.0796, respectively). On the contrary, the speed constant

k2 value decreases (0.0390) at 293 K. It was also evidenced that calculated

qe values are closer to the experimental

qe values than in the pseudo-first-order model, at least for 283 K and 303 K.

According to the correlation coefficients, experimental data better fits the pseudo-first-order model, indicating that this model better describes the As (V) adsorption process by iron oxide-coated ignimbrite. This conclusion allowed us to affirm that the external diffusion, internal diffusion, and adsorption processes were carried out simultaneously during the entire adsorption process [

34,

35].

Pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order speed constants,

k1 and

k2, calculated

qe value, and the corresponding correlation coefficient value R

2 for both mathematical models are summarized in

Table 3.

3.6. Adsorption Mechanism

The surface complex formation process is the most widely accepted mechanism for arsenic adsorption by iron oxides, although it is not completely clarified [

25,

36,

37]. The present research suggests a possible mechanism based on the goethite and hematite structure found on the modified ignimbrite surface.

During kinetic studies, the pH of the Na2HAsO4·7H2O solution in contact with the adsorbent was measured. The pH value registered was 3.8 at the beginning of the adsorption process and 3.7 after the first hour. This last value remained constant until the end of the study, at 2h 20 min.

Arsenate in an aqueous medium can exist in four forms: H3AsO4, H2AsO4-, HAsO4-2, and AsO4-3. According to arsenic acid pka values, the predominant species at a pH of 4, as the registered one, is H2AsO4-, so it is assumed that under this ionic form As (V) adsorption by iron oxide- coated ignimbrite occurs.

As proposed in

Figure 6, the modified ignimbrite surface is covered by crystalline structures such as goethite and hematite. Thus, hydroxyl groups would cover the entire surface of the adsorbent particles, allowing them to attract anions in acidic solutions by positively charging the adsorbent surface. However, this property could be lost as the solution pH increased.

As shown in

Figure 6, As (V) adsorption would be due to complexes formation on the adsorbent surface by ligand exchange between surface hydroxyl groups of the modified ignimbrite and protons of H

2AsO

4-. This process could also involve the adsorbent surface deprotonation, forming inner-sphere surface complexes [

38]. According to the proposed mechanism, from a geometric point of view, it is suggested that the AsO

4 tetrahedral structure would join the goethite octahedral structure (FeO

6), forming binuclear bidentate complexes as a result of sharing corners between two O atoms of AsO

4 and a pair of edge-sharing FeO

6 octahedra (

2C in

Figure 7). Likewise, Sherman & Randall [

39] point out that monodentate complexes formation (

1V in

Figure 7) and mononuclear bidentate complexes are feasible due to sharing edges between an AsO

4 tetrahedron and the free edge of a FeO

6 octahedron. (

2E in

Figure 7).

To corroborate the As (V) adsorption by the iron oxide-coated ignimbrite, an ICP-OES analysis was carried out on an adsorbent sample used in one of the kinetic tests. It was determined that arsenic presence in the modified ignimbrite at a 2,203 g As (V) per kg of ignimbrite concentration could confirm covalent bonds formation between them and, therefore, iron oxide-coated ignimbrite efficiency as a potential adsorbent.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates the success of ignimbrite modification using the proposed iron oxide coating procedure. ICP-OES demonstrated at 17.73 g·kg-1 iron concentration in the modified material. Furthermore, a linear, precise, and exact voltammetric technique was established for As (V) quantitative determination in an aqueous medium. Optimal parameters were identified, including an adsorbent concentration of 0.15 g/50 mL, a minimum contact time of 60 min, and 293 K ± 1 K temperature, achieving 15 mg·L-1 As (V) adsorption. Internal sphere surface complex formation was confirmed as an adsorption mechanism for As (V). Iron oxide-coated ignimbrite efficiency was demonstrated, with an arsenic concentration of 2.203 g∙kg-1 at the end of the adsorption process. These findings support the feasibility and effectiveness of the developed adsorbent for As (V) removal in environmental and technological applications.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft, L.V.-A.; Supervision, A.C.-C.; Writing – review & editing, R.S.-A.; Methodology, B.G.-V.; Resources, J.A.V.-S.

Funding

This research was funded by the INIA project CUI 2487112 “Mejoramiento de los servicios de investi-gación y transferencia tecnológica en el manejo y recuperación de suelos agrícolas degradados y aguas para riego en la pequeña y mediana agricultura en los departamentos de Lima, Áncash, San Martín, Cajamarca, Lambayeque, Junín, Ayacucho, Arequipa, Puno y Ucayali”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, V.; Parihar, R.D.; Sharma, A.; Bakshi, P.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Karaouzas, I.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thukral, A.K.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; et al. Global Evaluation of Heavy Metal Content in Surface Water Bodies: A Meta-Analysis Using Heavy Metal Pollution Indices and Multivariate Statistical Analyses. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124364. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.J.; Ali, A.; DeLaune, R.D. Heavy Metals and Metalloid Contamination in Louisiana Lake Pontchartrain Estuary along I-10 Bridge. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2016, 44, 66–77. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro De Oliveira, E.C.; Caixeta, E.S.; Santos, V.S.V.; Pereira, B.B. Arsenic Exposure from Groundwater: Environmental Contamination, Human Health Effects, and Sustainable Solutions. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2021, 24, 119–135. [CrossRef]

- Lamm, S.H.; Boroje, I.J.; Ferdosi, H.; Ahn, J. A Review of Low-Dose Arsenic Risks and Human Cancers. Toxicology 2021, 456, 152768. [CrossRef]

- Palma-Lara, I.; Martínez-Castillo, M.; Quintana-Pérez, J.C.; Arellano-Mendoza, M.G.; Tamay-Cach, F.; Valenzuela-Limón, O.L.; García-Montalvo, E.A.; Hernández-Zavala, A. Arsenic Exposure: A Public Health Problem Leading to Several Cancers. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2020, 110, 104539. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, S. Arsenic Exposure with Reference to Neurological Impairment: An Overview. Rev Environ Health 2019, 34, 403–414. [CrossRef]

- Signes-Pastor, A.J.; Vioque, J.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; Carey, M.; García-Villarino, M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Tardón, A.; Santa-Marina, L.; Irizar, A.; Casas, M.; et al. Inorganic Arsenic Exposure and Neuropsychological Development of Children of 4–5 Years of Age Living in Spain. Environ Res 2019, 174, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Alka, S.; Shahir, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Ndejiko, M.J.; Vo, D.V.N.; Manan, F.A. Arsenic Removal Technologies and Future Trends: A Mini Review. J Clean Prod 2021, 278, 123805. [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, A.; Ge, J.; Meng, X. A Comprehensive Study of Treatment of Arsenic in Water Combining Oxidation, Coagulation, and Filtration. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2015, 36, 178–180. [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, G.; Santos, S.; Boaventura, R.; Botelho, C. Arsenic and Antimony in Water and Wastewater: Overview of Removal Techniques with Special Reference to Latest Advances in Adsorption. J Environ Manage 2015, 151, 326–342. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, D.; Peng, C.; Chen, W. Arsenic Removal from Highly-Acidic Wastewater with High Arsenic Content by Copper-Chloride Synergistic Reduction. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124675. [CrossRef]

- Asere, T.G.; Stevens, C. V.; Du Laing, G. Use of (Modified) Natural Adsorbents for Arsenic Remediation: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 676, 706–720. [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, N.; Li, G. A Critical Review on Arsenic Removal from Water Using Iron-Based Adsorbents. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 39545–39560. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U. Arsenic Removal from Water/Wastewater Using Adsorbents—A Critical Review. J Hazard Mater 2007, 142, 1–53. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; Zengin, A.; Şahan, T. A Novel Material Poly(N-Acryloyl-L-Serine)-Brush Grafted Kaolin for Efficient Elimination of Malachite Green Dye from Aqueous Environments. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2020, 601, 125041. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; Zengin, A.; Şahan, T.; Zorer, Ö.S. Utilization of a Novel Polymer–Clay Material for High Elimination of Hazardous Radioactive Contamination Uranium(VI) from Aqueous Environments. Environ Technol Innov 2021, 23, 101631. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; Zengin, A.; Şahan, T.; Gübbük, İ.H. Efficient Removal of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid from Aqueous Medium Using Polydopamine/Polyacrylamide Co-Deposited Magnetic Sporopollenin and Optimization with Response Surface Methodology Approach. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 36–49. [CrossRef]

- Consideraciones y Reflexiones En Torno a La Ruta Del Sillar En Arequipa – INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL Available online: https://patrimonioculturalperu.com/2019/07/04/consideraciones-y-reflexiones-en-torno-a-la-ruta-del-sillar-en-arequipa/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Lebti, P.P.; Thouret, J.C.; Wörner, G.; Fornari, M. Neogene and Quaternary Ignimbrites in the Area of Arequipa, Southern Peru: Stratigraphical and Petrological Correlations. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2006, 154, 251–275. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Yanful, E.K.; Pratt, A.R. Arsenic Removal from Aqueous Solutions by Mixed Magnetite-Maghemite Nanoparticles. Environ Earth Sci 2011, 64, 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Lin, S.; Nizeyimana, J.C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X. Removal of Copper Ions from Wastewater via Adsorption on Modified Hematite (α-Fe2O3) Iron Oxide Coated Sand. J Clean Prod 2021, 319, 128687. [CrossRef]

- Peter, K.T.; Myung, N. V.; Cwiertny, D.M. Surfactant-Assisted Fabrication of Porous Polymeric Nanofibers with Surface-Enriched Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Composite Filtration Materials for Removal of Metal Cations. Environ Sci Nano 2018, 5, 669–681. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and Soft Acids and Bases, HSAB, Part 1: Fundamental Principles. J Chem Educ 1968, 45, 581. [CrossRef]

- Schwertmann, U.; Cornell, R.M. Iron Oxides in the Laboratory, 2nd, Completely Revised and Enlarged Edition. 2000, 204.

- Thirunavukkarasu, O.S.; Viraraghavan, T.; Subramanian, K.S. Arsenic Removal from Drinking Water Using Iron Oxide-Coated Sand. Water Air Soil Pollut 2003, 142, 95–111. [CrossRef]

- Metodologías Analíticas Para La Determinación y Especiación de Arsénico En Aguas y Suelos. - CONICET Available online: https://bicyt.conicet.gov.ar/fichas/produccion/1867068 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Scheiber, L.; Ayora, C.; Vázquez-Suñé., E.; Cendón, D.I.; Soler, A.; Baquero, J.C. Origin of High Ammonium, Arsenic and Boron Concentrations in the Proximity of a Mine: Natural vs. Anthropogenic Processes. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 541, 655–666. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Locke, D.C. Cathodic Stripping Voltammetric Analysis of Arsenic Species in Environmental Water Samples. Microchemical Journal 2007, 85, 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.M. Carbon Nanomaterials as Adsorbents for Environmental Analysis. Wiley Blackwell 6 2015, 9781118496978, 217–236. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Goyal, P. Biosorbents Used So Far. Environmental Science and Engineering 2010, 51–52. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; Porter, J.F.; McKay, G. Equilibrium Isotherm Studies for the Sorption of Divalent Metal Ions onto Peat: Copper, Nickel and Lead Single Component Systems. Water Air Soil Pollut 2002, 141, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Malana, M.A.; Ijaz, S.; Ashiq, M.N. Removal of Various Dyes from Aqueous Media onto Polymeric Gels by Adsorption Process: Their Kinetics and Thermodynamics. Desalination 2010, 263, 249–257. [CrossRef]

- Matouq, M.; Jildeh, N.; Qtaishat, M.; Hindiyeh, M.; Al Syouf, M.Q. The Adsorption Kinetics and Modeling for Heavy Metals Removal from Wastewater by Moringa Pods. J Environ Chem Eng 2015, 3, 775–784. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M.M.; Sletten, R.S.; Bailey, R.P.; Bennett, T. Sorption and Filtration of Metals Using Iron-Oxide-Coated Sand. Water Res 1996, 30, 2609–2620. [CrossRef]

- Eisazadeh, A.; Eisazadeh, H.; Kassim, K.A. Removal of Pb(II) Using Polyaniline Composites and Iron Oxide Coated Natural Sand and Clay from Aqueous Solution. Synth Met 2013, 171, 56–61. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.C.; Lin, C.J.; Liao, C.H.; Chen, S.T. Removal of As(V) and As(III) by Reclaimed Iron-Oxide Coated Sands. J Hazard Mater 2008, 153, 817–826. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Saini, V.K.; Jain, N. Adsorption of As(III) from Aqueous Solutions by Iron Oxide-Coated Sand. J Colloid Interface Sci 2005, 288, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Yiacoumi, S.; Tien, C. Kinetics of Metal Ion Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions. Kinetics of Metal Ion Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions 1995. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.M.; Randall, S.R. Surface Complexation of Arsenic(V) to Iron(III) (Hydr)Oxides: Structural Mechanism from Ab Initio Molecular Geometries and EXAFS Spectroscopy. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2003, 67, 4223–4230. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).