Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

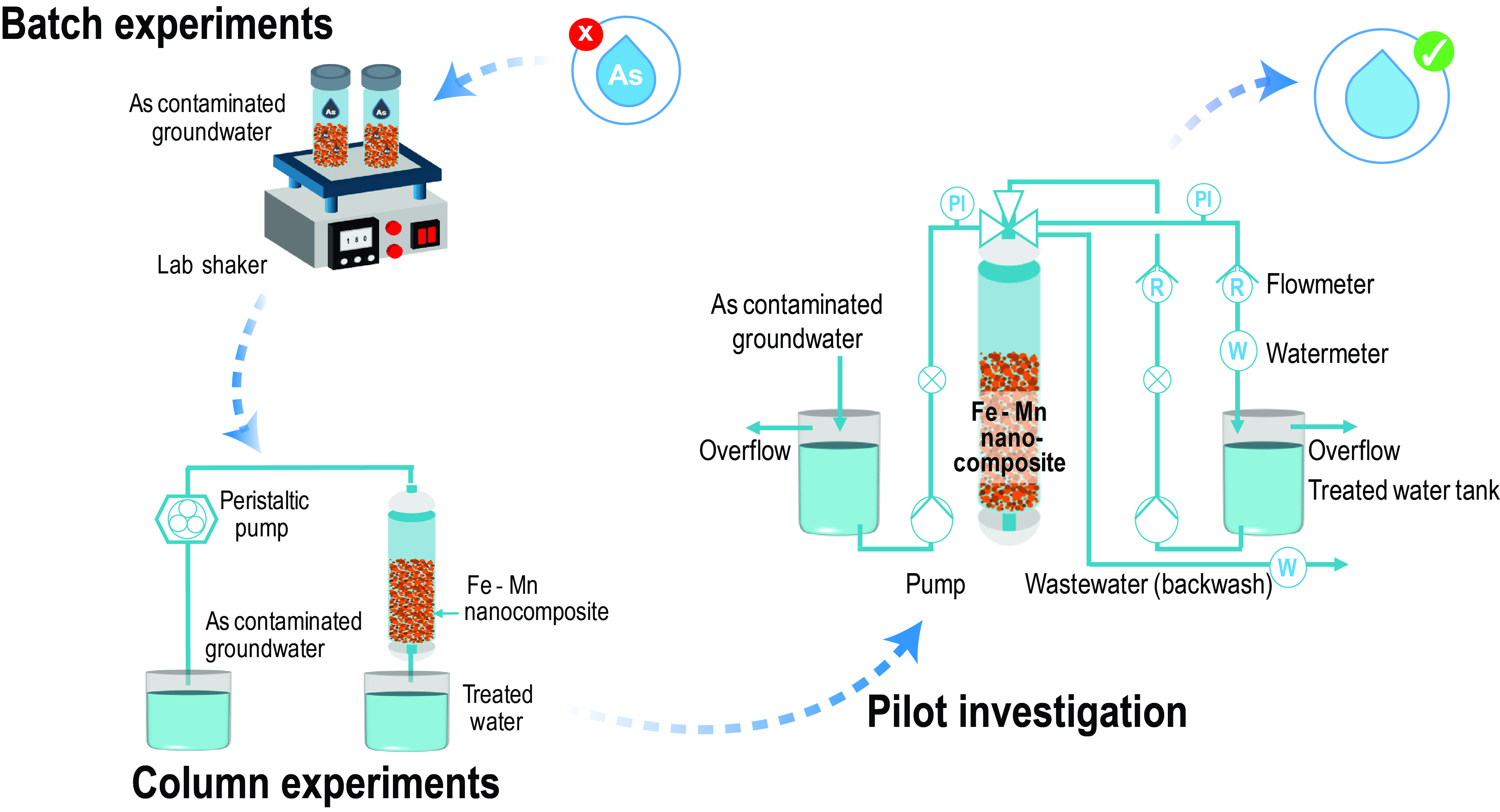

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1. Investigated Water Matrices

2.3. Batch Adsorption Experiment

2.4. Column Adsorption Experiment

2.5. Pilot Experiment

2.6. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

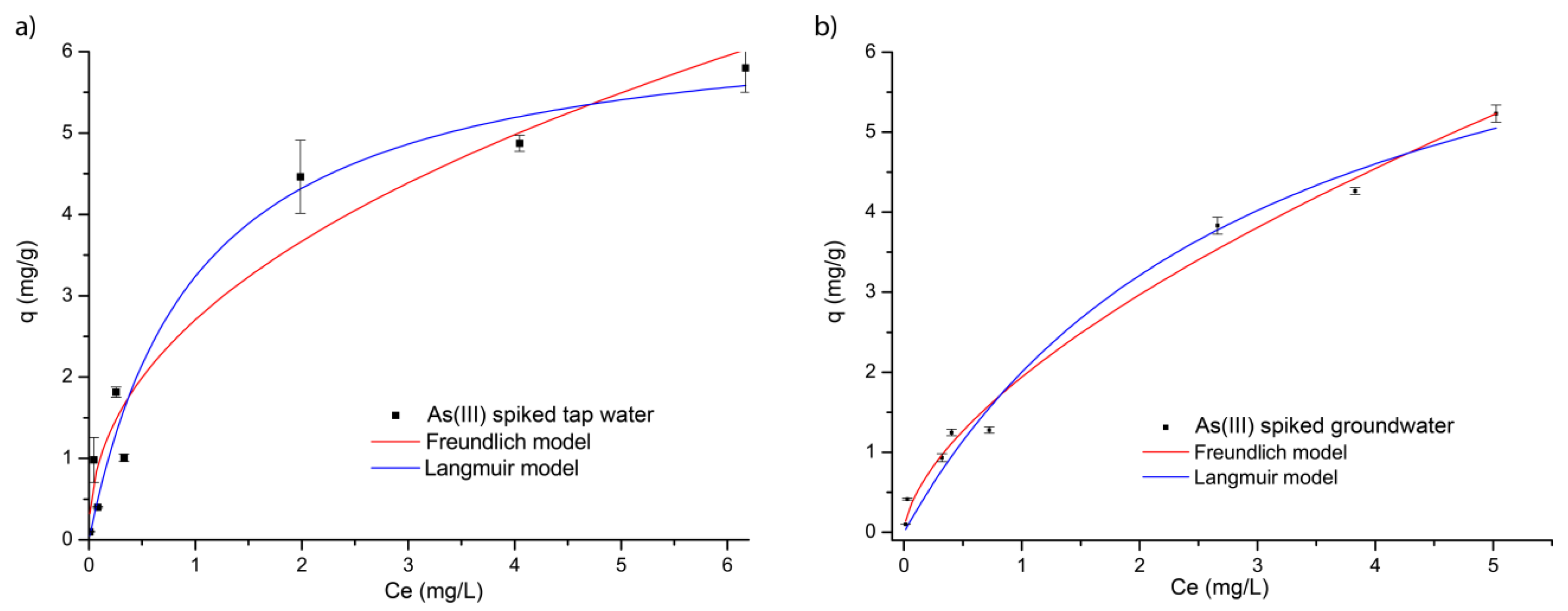

3.1. Batch Adsorption Study

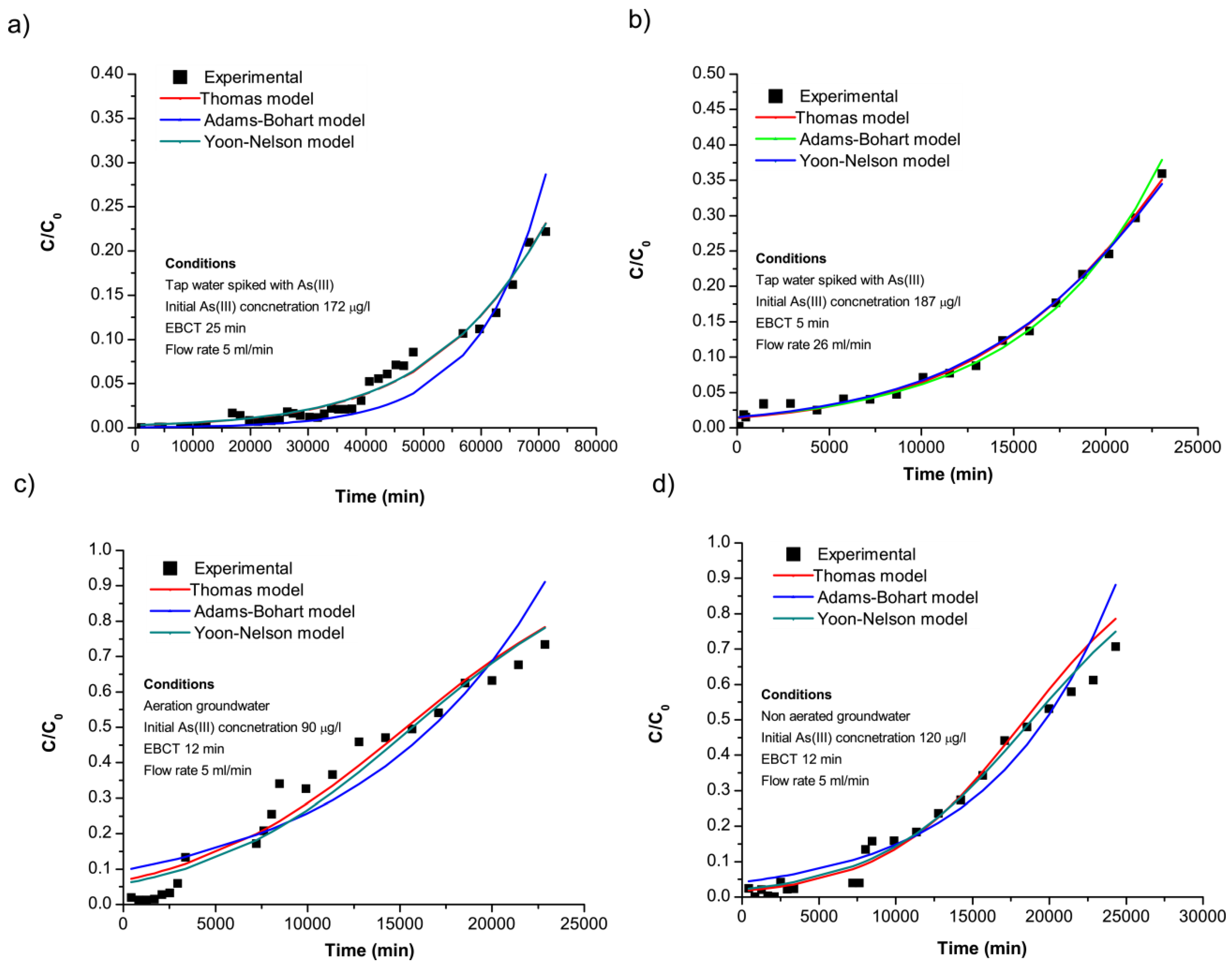

3.2. Column Adsorption Study

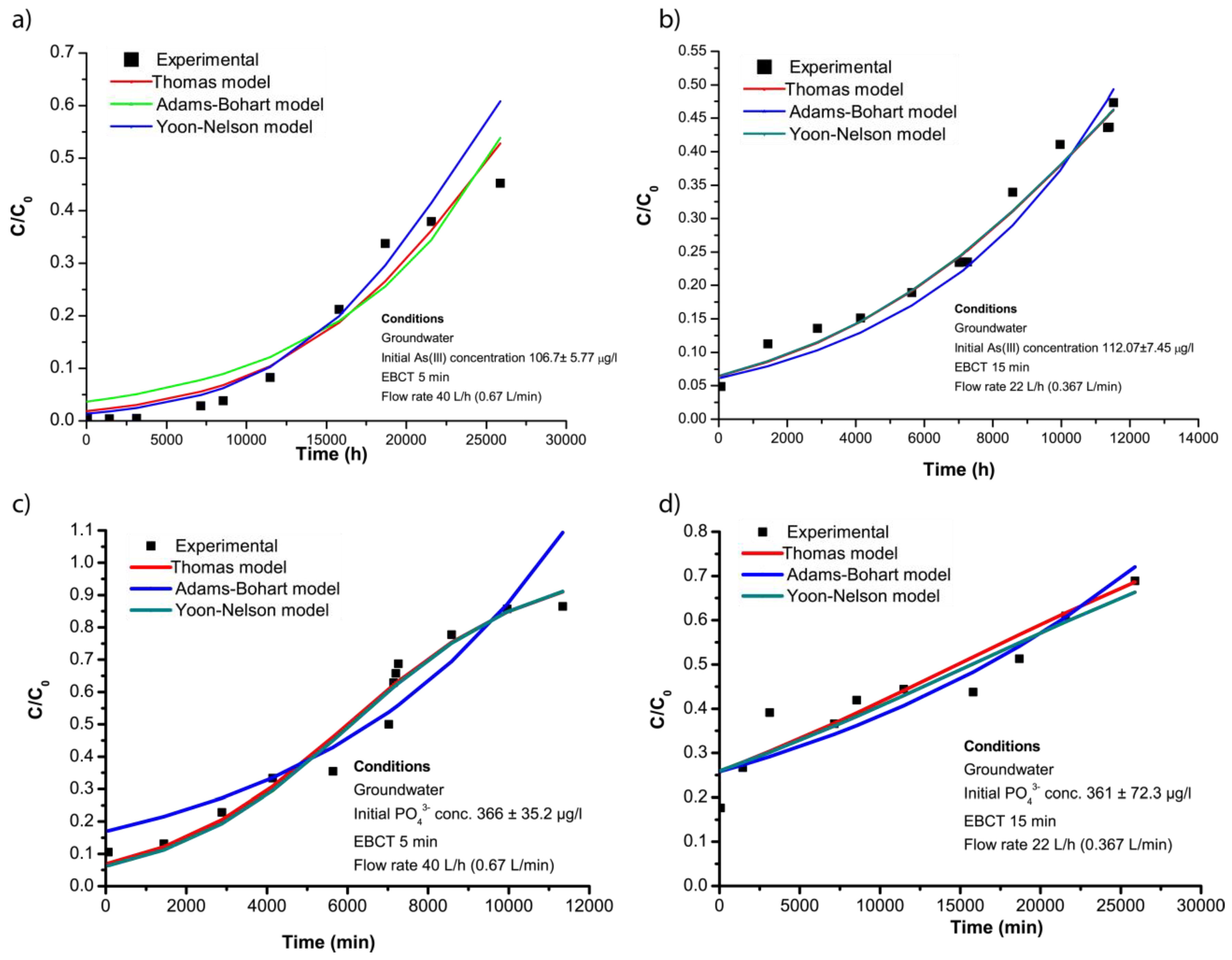

3.2.1. Modelling of Arsenic Adsorption in Fixed-Bed Columns

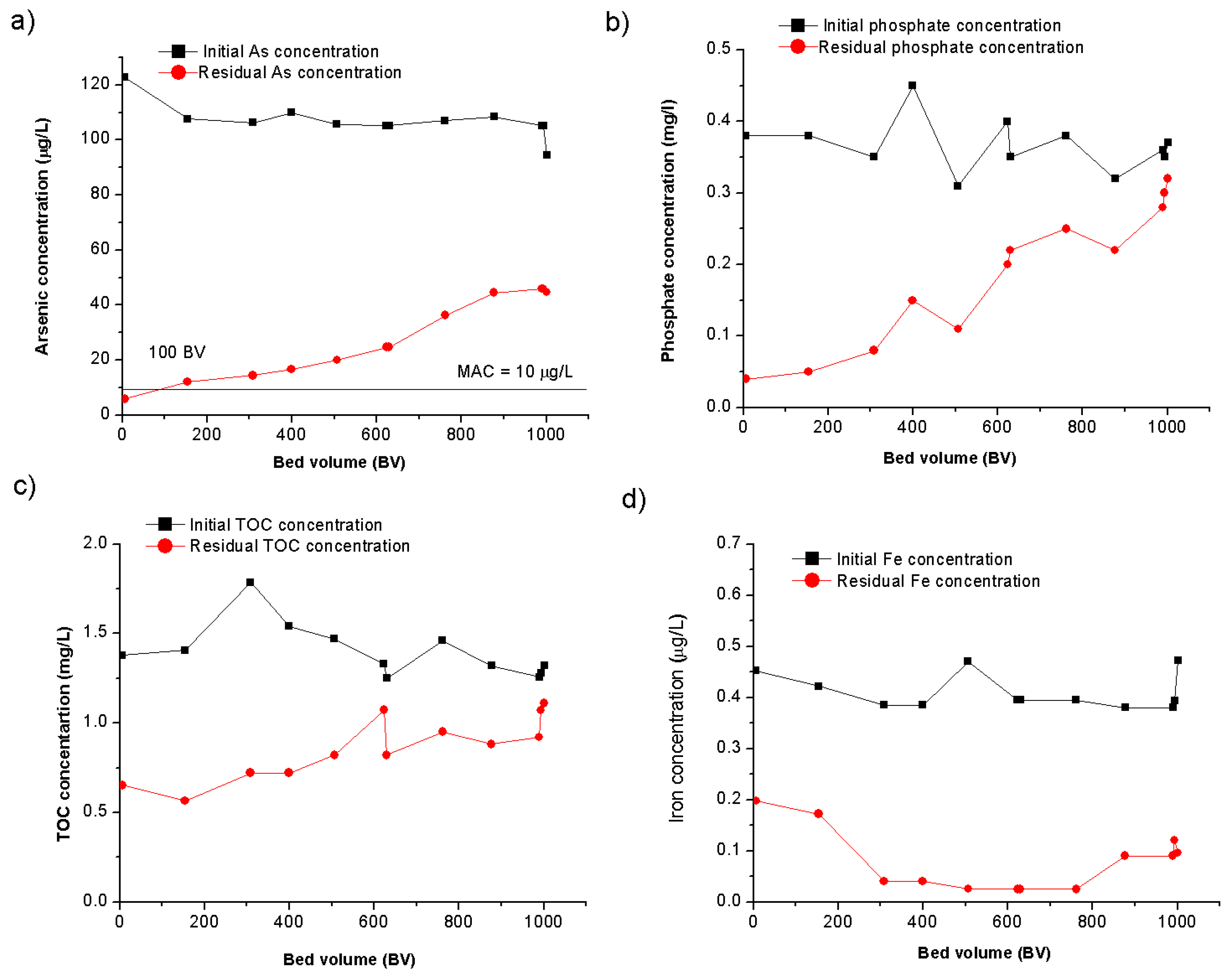

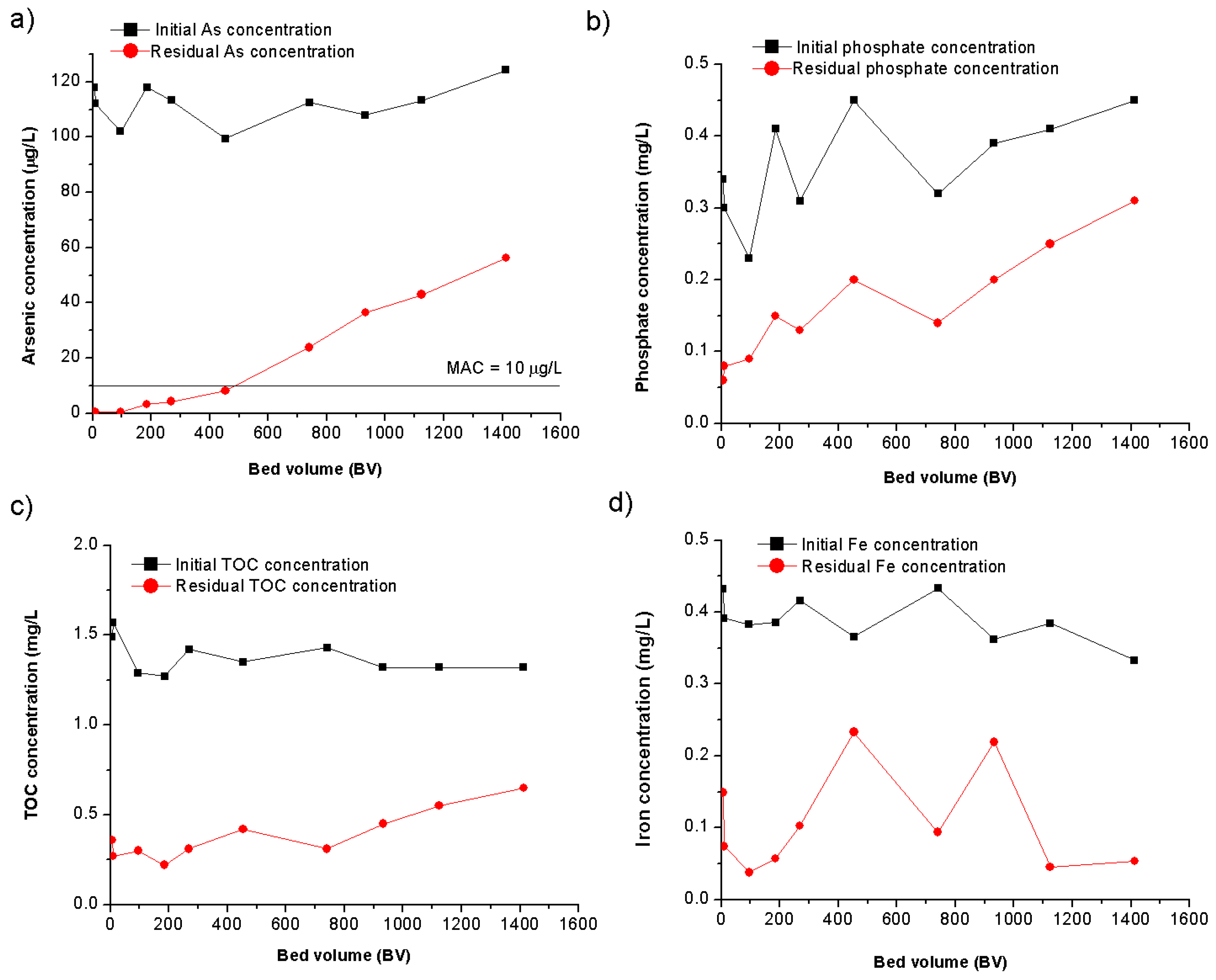

3.3. Pilot Study

3.1.1. Modelling of Arsenic Adsorption Under Realistic Treatment Conditions

3.4. Comparison Between Batch Experiments and Pilot-Scale Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaji, E.; Santosh, M.; Sarath, K.V.; et al. Arsenic contamination of groundwater: A global synopsis with focus on the Indian Peninsula. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cao, W.; Lang, G.; et al. Worldwide Distribution, Health Risk, Treatment Technology, and Development Tendency of Geogenic High-Arsenic Groundwater. Water 2024, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Coomar, P.; Sarkar, S.; et al. Arsenic and other geogenic contaminants in global groundwater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, J.O.; Badmus, J.A. Arsenic as an environmental and human health antagonist: A review of its toxicity and disease initiation. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 5, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Gundaliya, R.; Desai, B.; et al. Groundwater arsenic contamination: impacts on human health and agriculture, ex situ treatment techniques and alleviation. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 1331–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mo, W.; Wei, C.; et al. Fe/Mn-MOF-driven rapid arsenic decontamination: Mechanistic elucidation of adsorption processes and performance optimization. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Song, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Arsenic volatilization in flooded paddy soil by the addition of Fe-Mn-modified biochar composites. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; et al. Enhanced removal of As(III) and As(V) from aqueous solution using ionic liquid-modified magnetic graphene oxide. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; Mo, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. As(III) removal by a recyclable granular adsorbent through doping Fe-Mn binary oxides into graphene oxide chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 124184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Li, Z.; Ding, J.; et al. Arsenate adsorption, desorption, and re-adsorption on Fe–Mn binary oxides: Impact of co-existing ions. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikić, J.; Watson, M.; Jokić Govedarica, J.; et al. Adsorption Performance of Fe–Mn Polymer Nanocomposites for Arsenic Removal: Insights from Kinetic and Isotherm Models. Materials 2024, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Jeon, E.; Yang, J.S.; Baek, K. Adsorption of As(III) and As(V) in groundwater by Fe–Mn binary oxide-impregnated granular activated carbon (IMIGAC). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 72, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikić, J.; Agbaba, J.; Watson, M.A.; et al. Arsenic adsorption on Fe–Mn modified granular activated carbon (GAC–FeMn): batch and fixed-bed column studies. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2019, 54, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikić, J.; Watson, M.; Tenodi, K.Z.; et al. Pilot study on arsenic removal from phosphate rich groundwater by in-line co-agulation and adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 10, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Ghosh, U.D.C. Fixed-bed column performance of Mn-incorporated iron(III) oxide nanoparticle agglomerates on As(III) removal from the spiked groundwater in lab bench scale. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 248, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbenia John, M.; Benettayeb, A.; Belkacem, M.; et al. An overview on the key advantages and limitations of batch and dynamic modes of biosorption of metal ions. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 142051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.A.; Pintor, A.M.A.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; et al. Arsenic and antimony desorption in water treatment processes: Scaling up challenges with emerging adsorbents. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.S.; Qu, J.H.; Liu, H.J.; et al. Removal mechanism of As(III) by a novel Fe-Mn binary oxide adsorbent: Oxidation and sorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikić, J.; Watson, M.; Tubić, A.; et al. Arsenic removal from water using a one-pot synthesized low-cost mesoporous Fe–Mn-modified biosorbent. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2019, 84, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Qu, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Fe-Mn binary oxide incorporated into diatomite as an adsorbent for arsenite removal: Preparation and evaluation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 338, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, K.; Pan, B.; et al. Efficient As(III) removal by macroporous anion exchanger-supported Fe-Mn binary oxide: Behavior and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 193–194, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, H.; Dai, Y.; et al. Arsenic adsorption and removal by a new starch stabilized ferromanganese binary oxide in water. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 245, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; et al. Magnetic nanoscale Fe-Mn binary oxides loaded zeolite for arsenic removal from synthetic groundwater. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 457, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Qiu, W.; Wang, D.; et al. Arsenic removal in aqueous solution by a novel Fe-Mn modified biochar composite: Characterization and mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, H. Efficient removal of arsenic from water using a granular adsorbent: Fe-Mn binary oxide impregnated chitosan bead. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 193, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikić, J.; Watson, M.A.; Isakovski, M.K.; et al. Synthesis, characterization and application of magnetic nanoparticles modified with Fe-Mn binary oxide for enhanced removal of As(III) and As(V). Environ. Technol. 2019, 0, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Enhanced Arsenic Removal from Aqueous Solution by Fe/Mn-C Layered Double Hydroxide Composite. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Mondal, N.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; et al. Removal of arsenic(III) and arsenic(V) on chemically modified low-cost adsorbent: batch and column operations. Appl. Water Sci. 2013, 3, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.P.; Jha, U.; Kumar, S.A.; Swain, S.K. A Simplified and Affordable Arsenic Filter to Prevent Arsenic Poisoning: Lab-Scale Study and Pilot Experiment. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3, 4092–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Acid and organic resistant nano-hydrated zirconium oxide (HZO)/polystyrene hybrid adsorbent for arsenic removal from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 248, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, V.D.; Yamamura, G.; Kobayashi, A.; et al. Enhanced impregnation of iron manganese binary oxide nanoparticles on nylon 6 fibre for rapid and continuous arsenic [As(III)] removal from drinking water. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Qu, J.; Liu, R.; et al. Practical performance and its efficiency of arsenic removal from groundwater using Fe-Mn binary oxide. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, Z.; Chen, Z. Removal of arsenic from drinking water using rice husk. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brion-Roby, R.; Gagnon, J.; Deschênes, J.S.; et al. Investigation of fixed bed adsorption column operation parameters using a chitosan material for treatment of arsenate contaminated water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H. Fixed-bed column adsorption study: a comprehensive review. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apiratikul, R.; Chu, K.H. Improved fixed bed models for correlating asymmetric adsorption breakthrough curves. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunnen, C.; Ye, W.; Chen, L.; et al. Continuous fixed-bed column study and adsorption modeling: Removal of arsenate and arsenite in aqueous solution by organic modified spent grains. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, M.; Nikić, J.; Tubić, A.; et al. Repurposing spent filter sand from iron and manganese removal systems as an adsorbent for treating arsenic contaminated drinking water. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 302, 114115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, M.; Towfighi, H.; Shahbazi, K.; et al. Study of arsenic adsorption in calcareous soils: Competitive effect of phosphate, citrate, oxalate, humic acid and fulvic acid. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 318, 115532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasundara, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Bundschuh, J. Selective removal of arsenic in water: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268B, 115668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe-Mn based adsorbents |

Initial As concentration (mg/l) |

Water matrix | pH | Adsorption capacity in batch system (mg/g) | References | |

| As(III) | As(V) | |||||

| Fe–Mn binary oxide | 1-200 | Synthetic | 5 | 69.8 | 133 | [18] |

| Magnetite coated with FMBO | 0.2-50 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 55.9 | 54.1 | [19] |

| Diatomite coated with Fe–Mn binary oxide | 0.05-20 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 1.68 | - | [20] |

| Macroporous anion exchanger-supported Fe–Mn binary oxide | 1-50 | Synthetic water | 7.0 | 44.9 | 13.17 | [21] |

| Starch-FMBO | 0-300 | Synthetic | 161 | - | [22] | |

| Gelatin-FMBO | 0-300 | 141 | - | [22] | ||

| CMC-FMBO | 0-300 | 104 | - | [22] | ||

| Nanoscale Fe-Mn binary oxides loaded on zeolite(NIMZ) | 2-100 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 47 | 49 | [23] |

| Biochar coated with FMBO | 0.01-10 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 14.4 | 12.2 | [24] |

| GAC-FeMn | 0.01-1 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 2.30 | 2.87 | [13] |

| Chitosan-FMBO | 0-24 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 54.2 | - | [25] |

| Chitosan-FeMn | 0.1-1 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 3.91 | 3.89 | [26] |

| PET-FMBO | 0.1-1 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 8.74 | 13.3 | [11] |

| PE-FMBO | 0.1-1 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 5.29 | 5.37 | [11] |

| Graphene oxide chitosan coated FMBO (Fe/Mn GOCS) |

5-300 | Synthetic | 7.62 | 109 | - | [9] |

| Fe/Mn-C Layered Double Hydroxide Composite | 5-100 | Synthetic | - | 41.9 | 33.6 | [27] |

| Iron-manganese binary oxide nanoparticles on nylon 6 fibre | 1-100 | Synthetic | 7.0 | 134 | - | [6]) |

| Parameter | Water | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater | Aerated groundwater | Spiked tap water | |

| pH | 7.73 ±0.05 | 7.81 ± 0.05 | 7.51±0.04 |

| Conductivity(µS/cm) | 514 ± 43 | 466 ± 12 | 490 ± 22 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 1.55 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 0.31 ±0.07 |

| TOC (mg/L) | 1.38 ±0.10 | 1.53 ± 0.05 | 1.460 ± 0.05 |

| Arsenic (μg/L) | 115 ±6.4 | 90.0 ± 18.7 | 172 ± 20 |

| Iron (μg/L) | 395 ±28.1 | 5.36 ± 3.55 | 26.04 ± 2.20 |

| Manganese (μg/L) | 54 ±4.67 | 6.35 ± 8.52 | 3.22 ± 4.10 |

| Ammonium (mg N/L) | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 0.228 ± 0.12 | 0.454 ± 0.01 |

| Nitrate (mg N/L) | 1.57 ± 0.14 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Orthophosphate (mg PO4/L) | 0.323 ± 0.11 | 0.075 ± 0.02 | 0.024 ± 0.01 |

| Chloride (mg Cl/L) | 3.77 ±3.19 | 0.673.19 | 27.25 ± 0.01 |

| Model | Equation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Freundlich |

qe - Adsorbed amount at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce-Equilibrium concentration (mg/L), KF- Freundlich adsorption constant [(mg/g)(L/mg)^(1/n)] |

|

| Langmuir | qe-Adsorbed amount at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce: Equilibrium concentration (mg/L), qmax: Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), KL: Langmuir constant (L/mg) |

| Models | Equation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas | ct: Concentration at time (mg/L), c0: Initial concentration (mg/L), kTh: Thomas rate constant (L/min·mg), q0: Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), m: Mass of adsorbent (g), Q: Flow rate (L/min), t: Time (min) |

|

| Adams-Bohart | ct: Concentration at time (mg/L), c0: Initial concentration (mg/L), kAB: Adams-Bohart rate constant (L/mg·min), N0: Saturated adsorption capacity (mg/L), L: Packed bed length (cm), t: Time (min), u: Linear velocity (cm/min) |

|

| Yoon-Nelson | ct: Concentration at time (mg/L), c0: Initial concentration (mg/L), kYN: Yoon-Nelson rate constant (L/min), τ: Time required for 50% breakthrough (min), t: Time (min) |

| Filter media volume (L) | Mass of media (kg) | Bed depth (m) | Filtration rate (m/h) |

EBCT (min) |

Flow rate Q (L/h) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot A | 3.5 | 1.6 | 0.11 | 1.25 | 5.12 | 40 |

| Pilot B | 5.5 | 2.5 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 16.5 | 22 |

| Freundlich model | Langmuir model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix type | n | KF (mg/g)/(mg/L)n |

R2 | qmax (mg/g) |

KL (L/mg) |

R2 |

| As(III) spiked tap water | 0.640 | 2.70 | 0.9459 | 6.25 | 0.992 | 0.9577 |

| As(III) spiked groundwater | 0.420 | 1.79 | 0.9349 | 4.63 | 0.343 | 0.9452 |

| Fe-Mn based adsorbent | Length (cm) |

Diameter (cm) |

Mass of adsorbent (g) |

Bed depth (cm) |

Flow rate (mL/min) | EBCT (min) |

Water matrix | BV before MAC breakthrough | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene oxide chitosan coated FMBO (Fe/Mn GOCS) | 3 | 1.6 | 7.67 | - | 1.5 | - | Synthetic water matrix 10 or 50 mg/L As(III) pH 7 |

40 and 3 | [9] |

| Macroporous anion exchanger-supported Fe–Mn binary oxide | 13.0 | 1.2 | - | - | - | 3 | Simulated water As(III) 100 µg/L; Nitrate 150 mg/L; Carbonate 200 mg/L; Chloride 300 mg/L; Sulphate 300 mg/L; pH 8.10 |

2300 | [21] |

| Chitosan coated with Fe–Mn binary |

32 | 1.9 | 30 | 25 | - | 10 | Simulated groundwater As(III)/As(V) 233 μg/L; Nitrate 5 mg/L, Carbonate :159 mg/L; Silicate 12 mg/L; Phosphate 0.13 mg/L; pH 7.3 |

500 and 3200 for As(V) and As(III) |

[25] |

| GAC-FMBO | 80 | 1.7 | - | 30 | 6 | 12 | Groundwater As(III): 120 µg/L; Conduct. 678 mS/cm; DOC 2.00mg/L; Alkalinity 7.68 mmol/L; Chloride 19.7mg/L; Carbonate 118 mg/L; Sulphate 15.7 mg SO4/L; Phosphate 1.33mg/L; Fe 35.4 µg/L Mn 21.5 µg/L; pH 8.22 |

83 | [13] |

| HZO@D201 nanocomposite |

13 | 1.2 | 5 ml | - | - | 3 | Simulated groundwater As(III) 0.1 mg/L; Magnesium 5 mg/L; Sulphate 50 mg/L; Calcium 15 mg/L; Silicate 5 mg/ L; Chloride 40 mg/L; Nitrate 8 mg/L; Carbonate 150 mg/L; pH : 8.2; |

600 | [30] |

| FMBO-diatomite | 40 | 3 | 58 | 24 | 17 | 10 | Anaerobic groundwater; Astot 0.0477 mg/L; As(III) 0.03 mg/L; Turbidity 0.7 NTU; Conductivity 530 mS/cm; TOC 2.84 mg/L; 305 mg/L; Magnesium 16 mg/L; Calcium 28 mg/L; Chloride 40 mg/L; Nitrate 9.8 mg/L; Phosphor 1.21 mg/L; Mn 0.15.1 mg/L; Fe 0.257 mg/L; Nitrogen 66 mg/L; pH: 7.4 |

7000 BVs after 15 regenerations | [20] |

| FMBO-diatomite | 40 | 3 | - | - | 34 | 5 | Spiked DI water with As(III) | 4500 | [32] |

| FMBO impregnated nylon 6 fibre (IMBNP-nylon 6) | 4 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.65 | Spiked RO water with As(III) 0.1 and 0.038 mg/L; Magnesium 5 mg/L; Sulphate 50 mg/L; Calcium 15 mg/L; Silicate 5 mg/ L; Chloride 40 mg/L; Nitrate 8 mg/L; Carbonate 150 mg/L; pH : 8.2 |

5200 and 21000 | [31] |

| Thomas constant | Adams-Bohart | Yoon Nelson | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qexp (mg/g) |

qt (mg/g) |

KTh (L/mg min) |

R2 | No (mg/L) | KAB (L/mg min) |

R2 | kYN (/min−1) | ɼ (min) | R2 | |

| Column I | 1.02 | 1.34 | 0.0003765 | 0.9744 | 588 | 0.000489 | 0.9124 | 0.0000641 | 90014 | 0.9915 |

| Column II | 1.42 | 1.71 | 0.000845 | 0.9920 | 863 | 0.000747 | 0.9909 | 0.000153 | 27248 | 0.9915 |

| Column III | 0.238 | 0.252 | 0.00191 | 0.9824 | 122 | 0.00109 | 0.8754 | 0.000177 | 15690 | 0.9497 |

| Column IV | 0.343 | 0.405 | 0.00183 | 0.9760 | 174 | 0.00104 | 0.9384 | 0.000202 | 18871 | 0.9733 |

| Thomas constant | Adams-Bohart | Yoon-Nelson | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qexp (mg/g) |

qt (mg/g) |

KTb (L/mg min) |

R2 | No (mg/L) | KAB (L/mg min) |

R2 | KYN (min−1) | ɼ (min) | R2 | ||

| Pilot A | Arsenic | 0.337 | 0.551 | 0.00206 | 0.9497 | 327 | 0.00171 | 0.9589 | 0.000218 | 12197 | 0.9802 |

| Phosphate | 0.811 | 0.926 | 0.00118 | 0.9726 | 792 | 0.000448 | 0.8598 | 0.000445 | 6091 | 0.9635 | |

| Pilot B | Arsenic | 0.243 | 0.417 | 0.00139 | 0.9485 | 216 | 0.000924 | 0.9502 | 0.000181 | 23463 | 0.9234 |

| Phosphate | 0.731 | 0.789 | 0.000196 | 0.9864 | 770 | 0.000111 | 0.8818 | 0.0000667 | 15719 | 0.9881 | |

| Scale | mass adsorbent | qexp (mg/g) |

q (Langmuir or Thomas model) (mg/g) | Breakthrough point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch experiments | 20 | mg | 4.71 | ||

| Column III | 28 | g | 0.238 | 0.252 | 587 |

| Column IV | 28 | g | 0.343 | 0.405 | 365 |

| Pilot A | 1.6 | kg | 0.337 | 0.551 | 100 |

| Pilot B | 2.5 | kg | 0.243 | 0.417 | 475 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).