Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

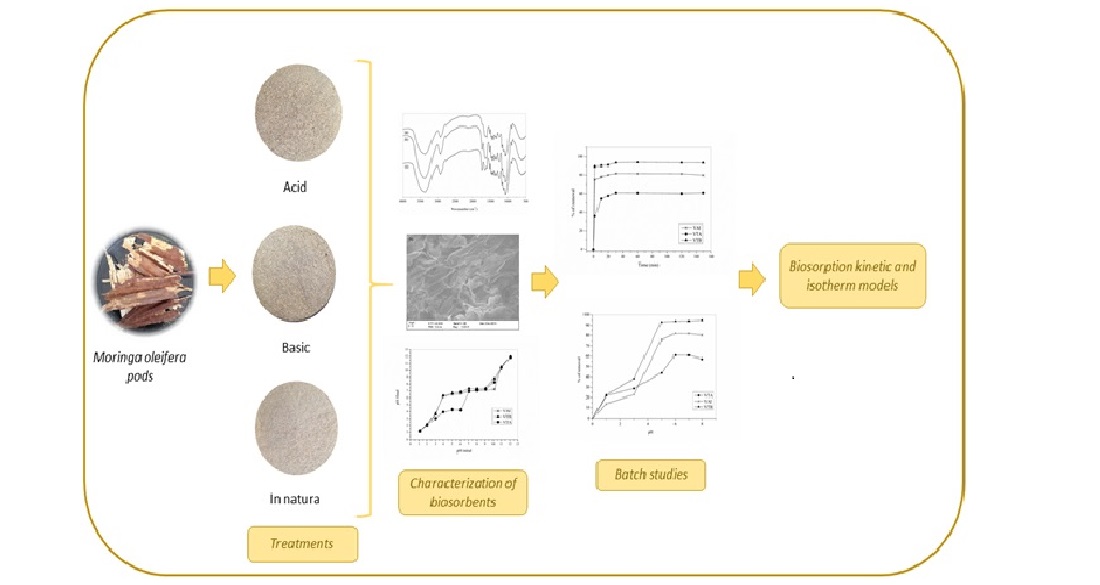

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

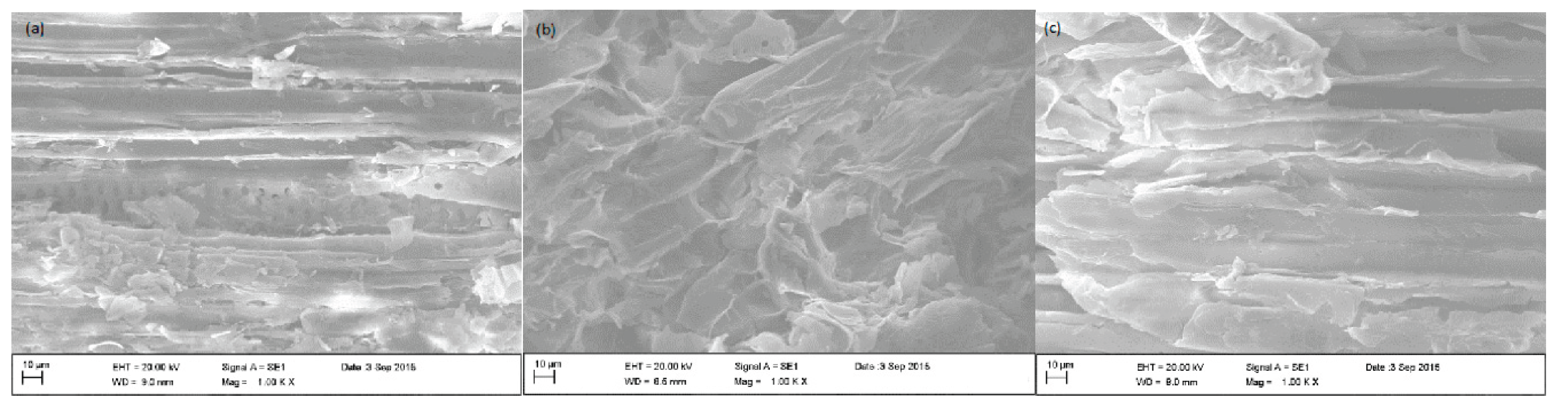

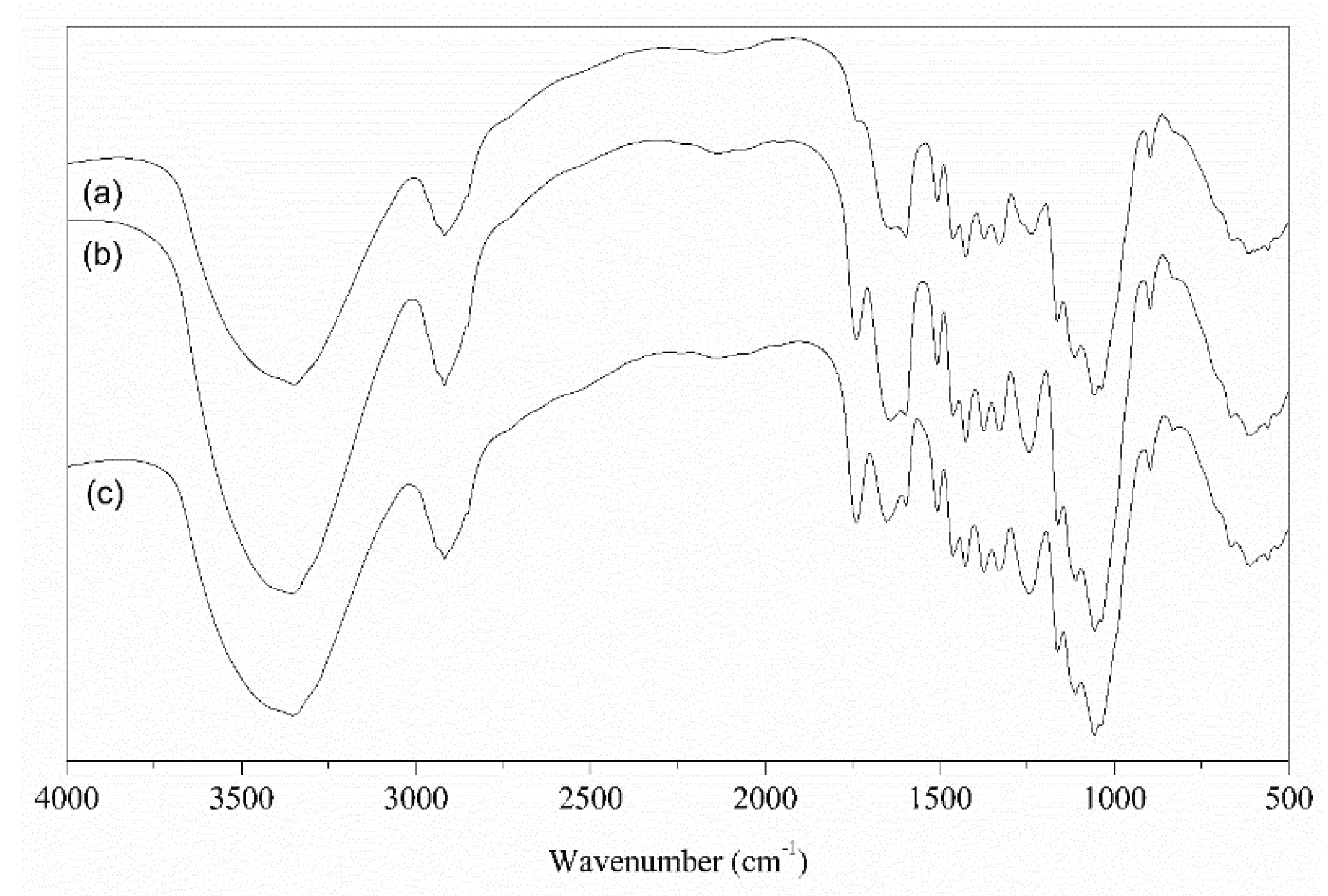

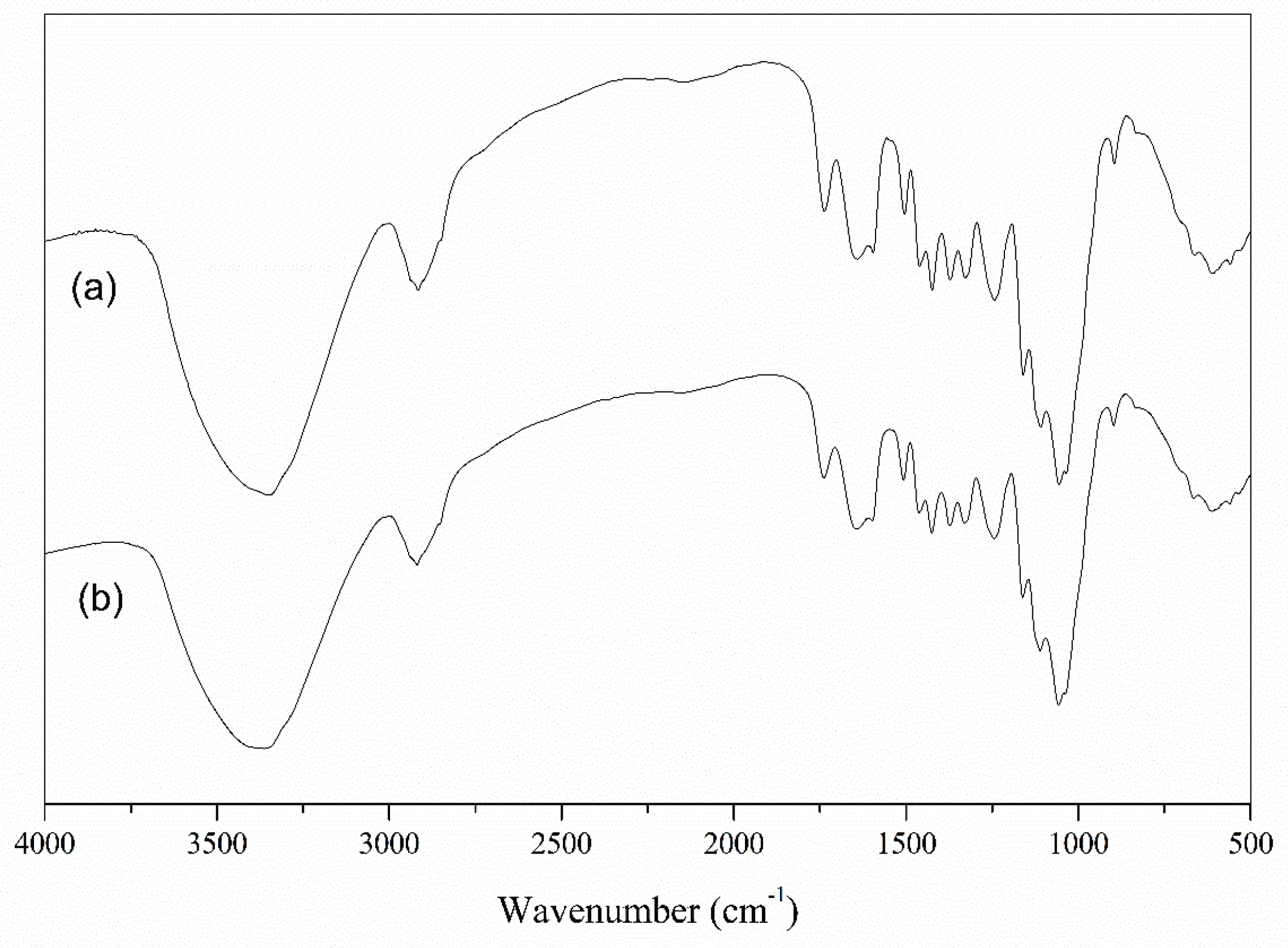

2.1. Biosorbents Characterization

2.2. Biomass Modification

2.3. Biosorption Experiments

3. Results Discussion

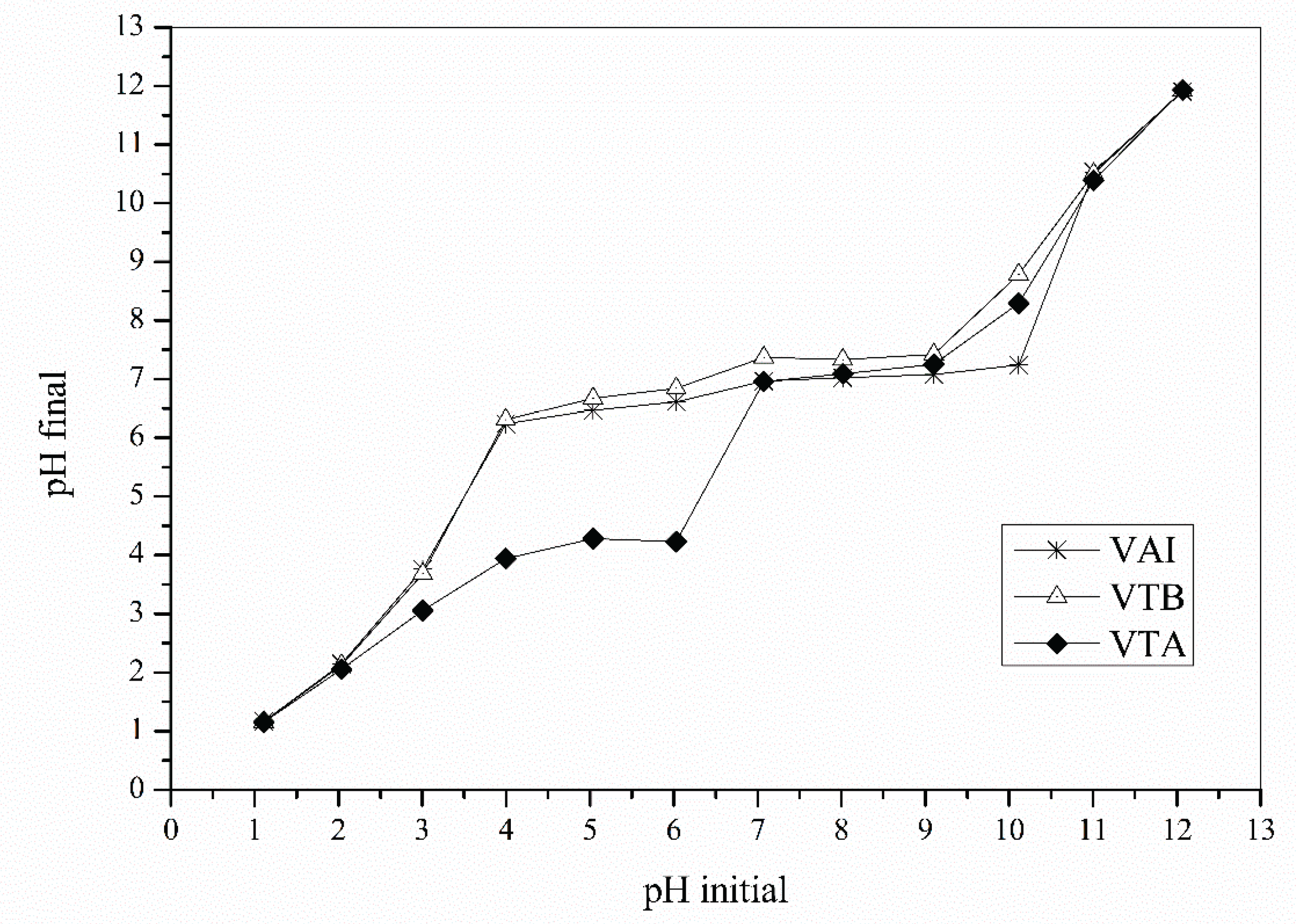

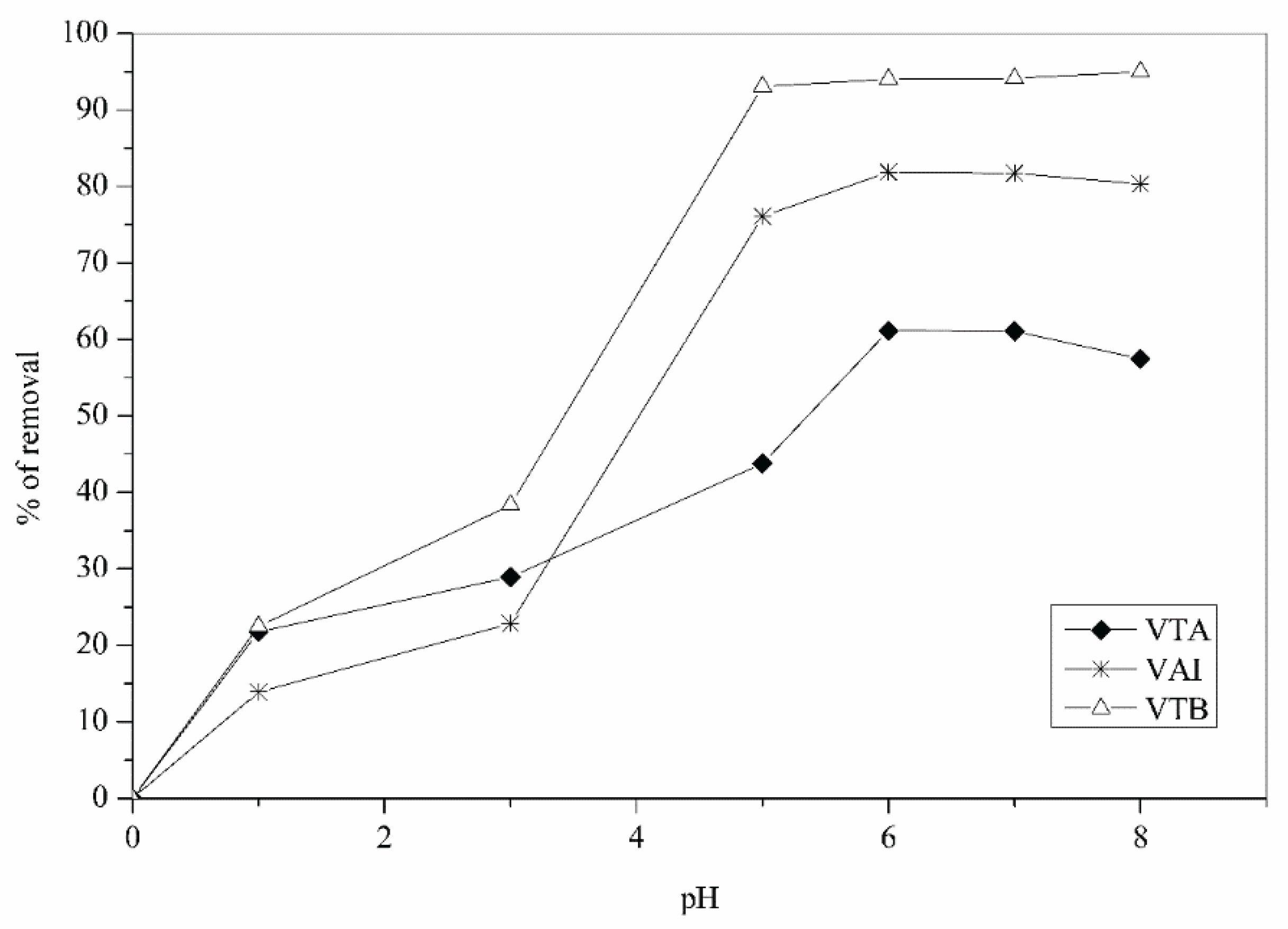

3.1. Biosorbents Characterization

Zero Charge Point

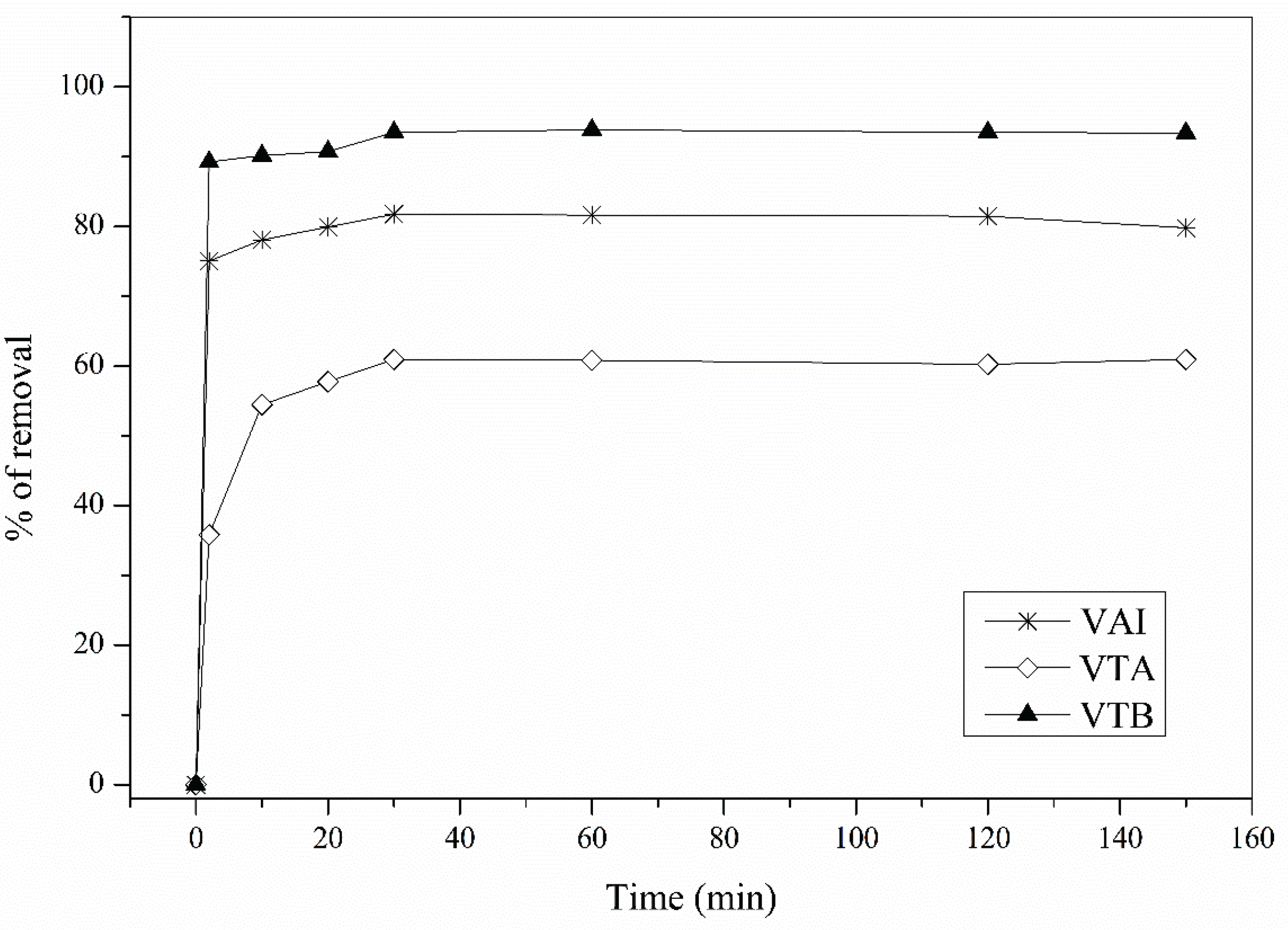

3.2. Contact Time Effect

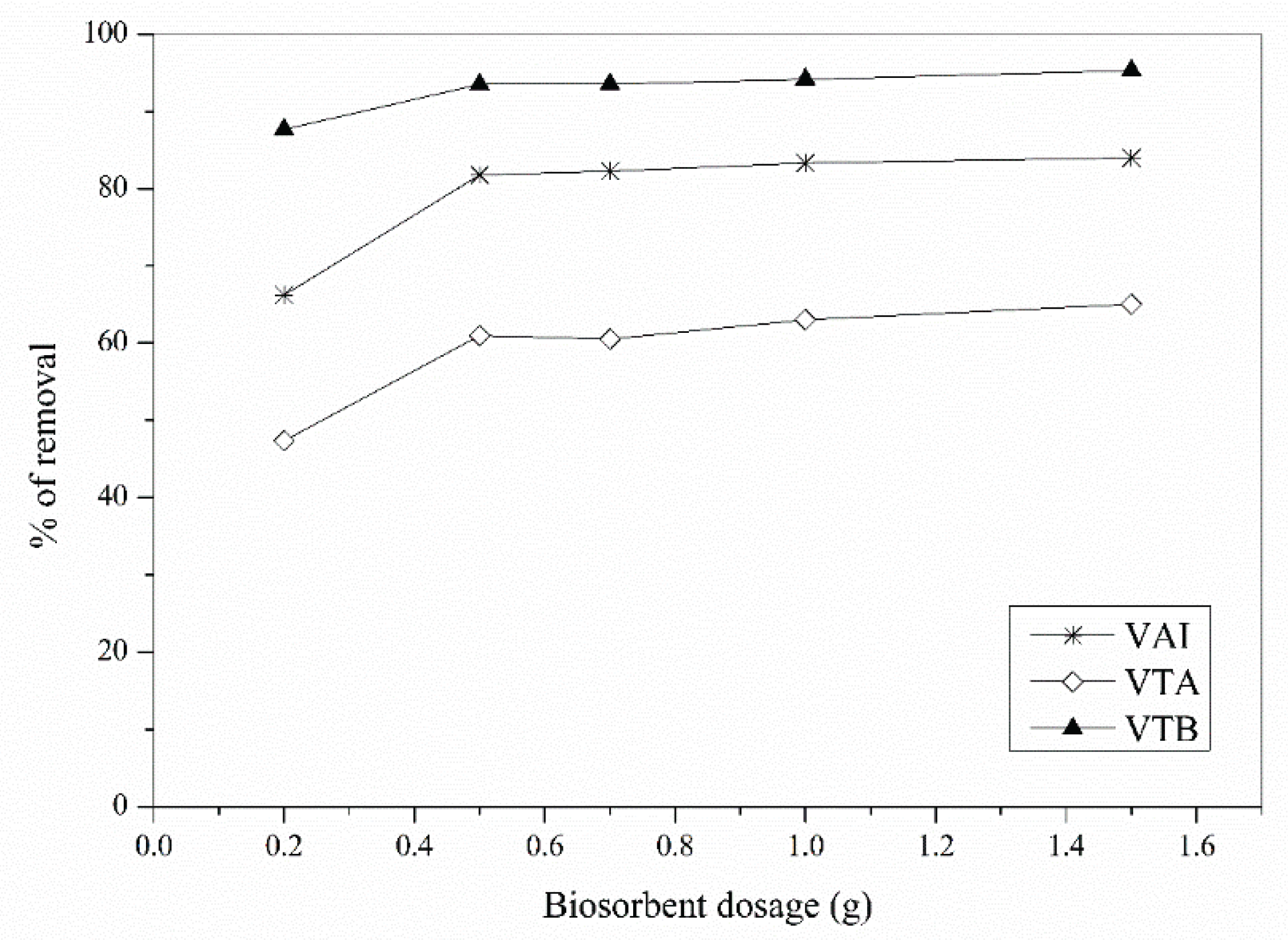

3.4. Biosorbent Dose Effect

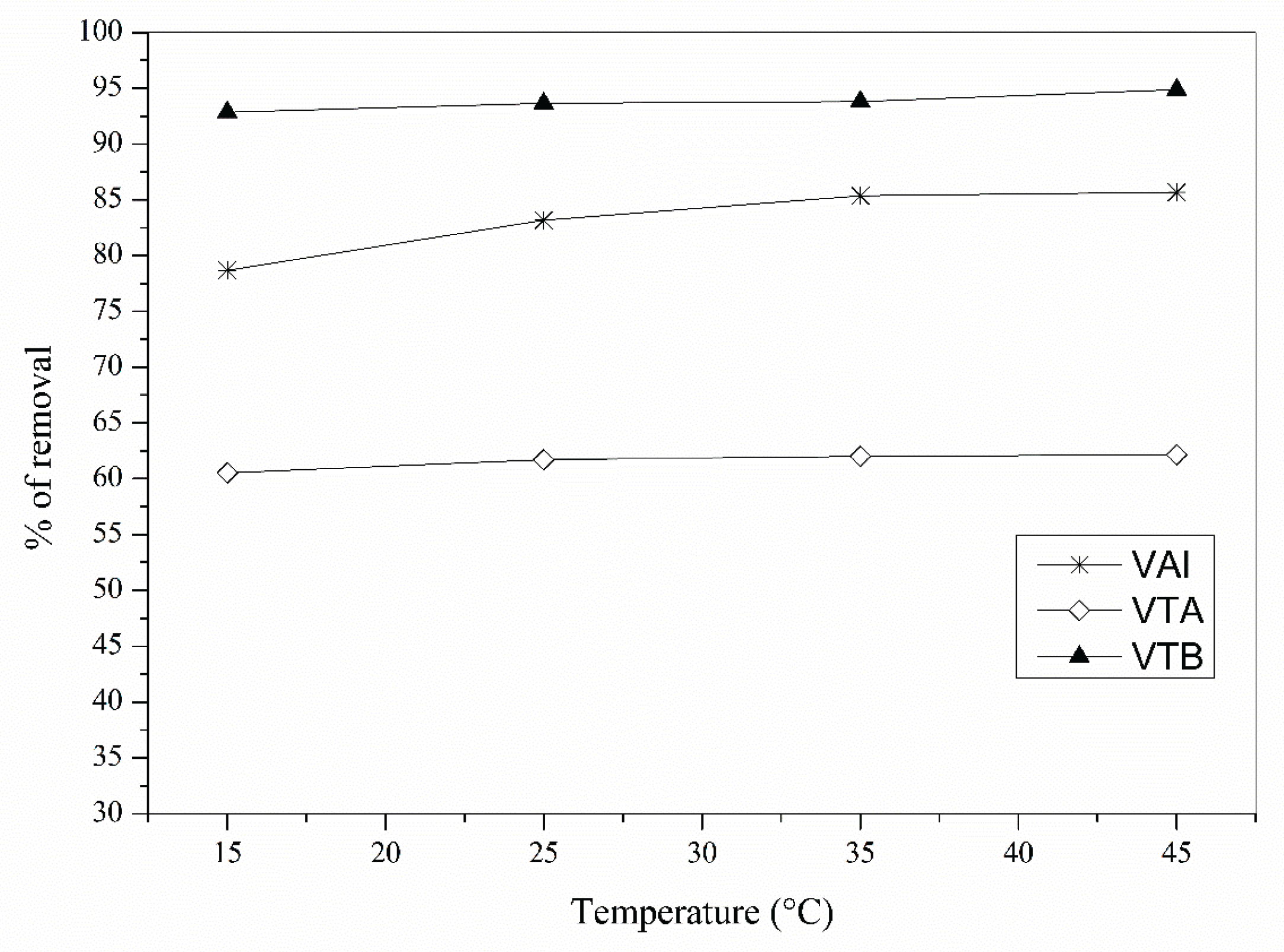

3.5. Temperature Effect in Biosorption

3.6. Kinetic Study

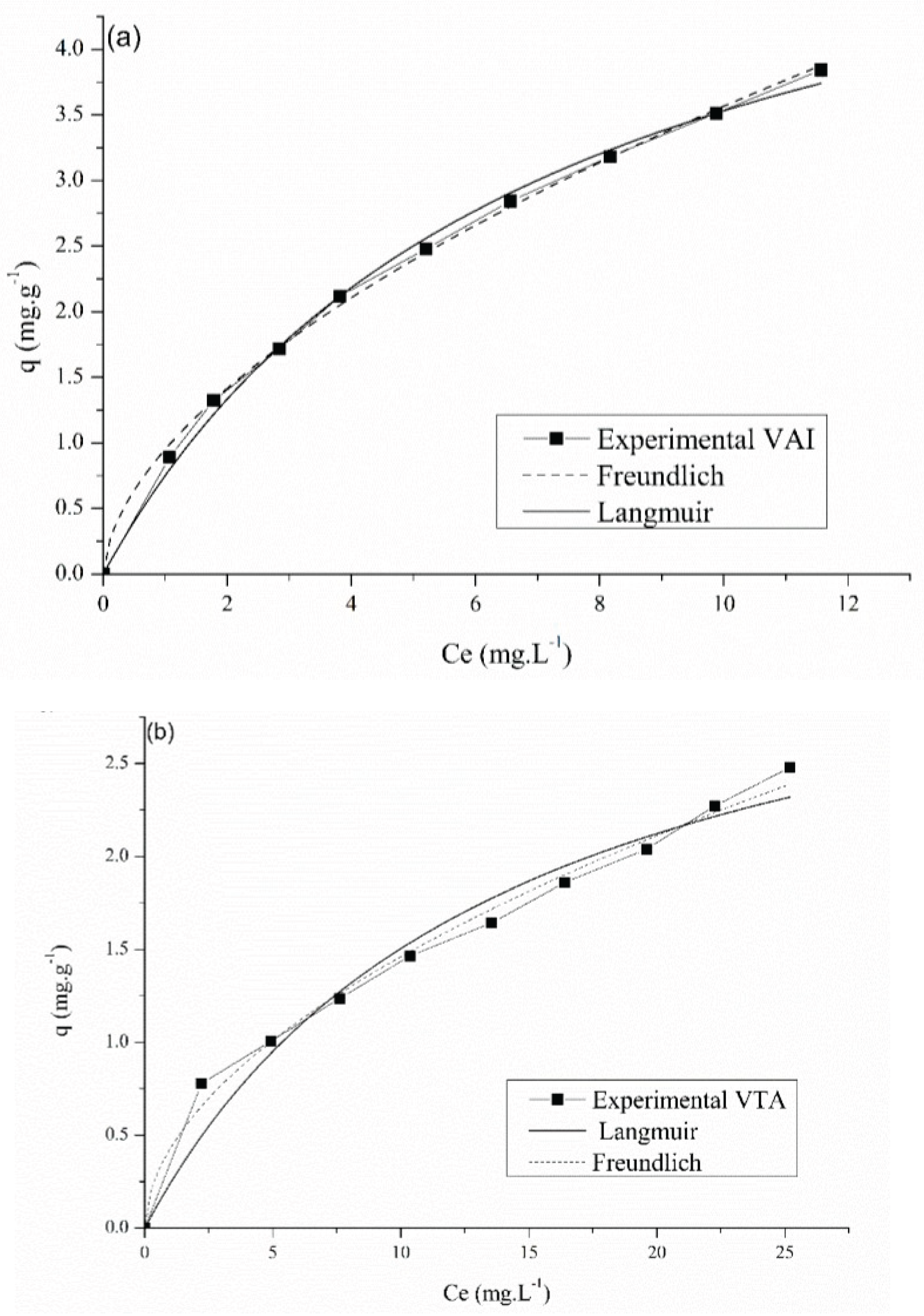

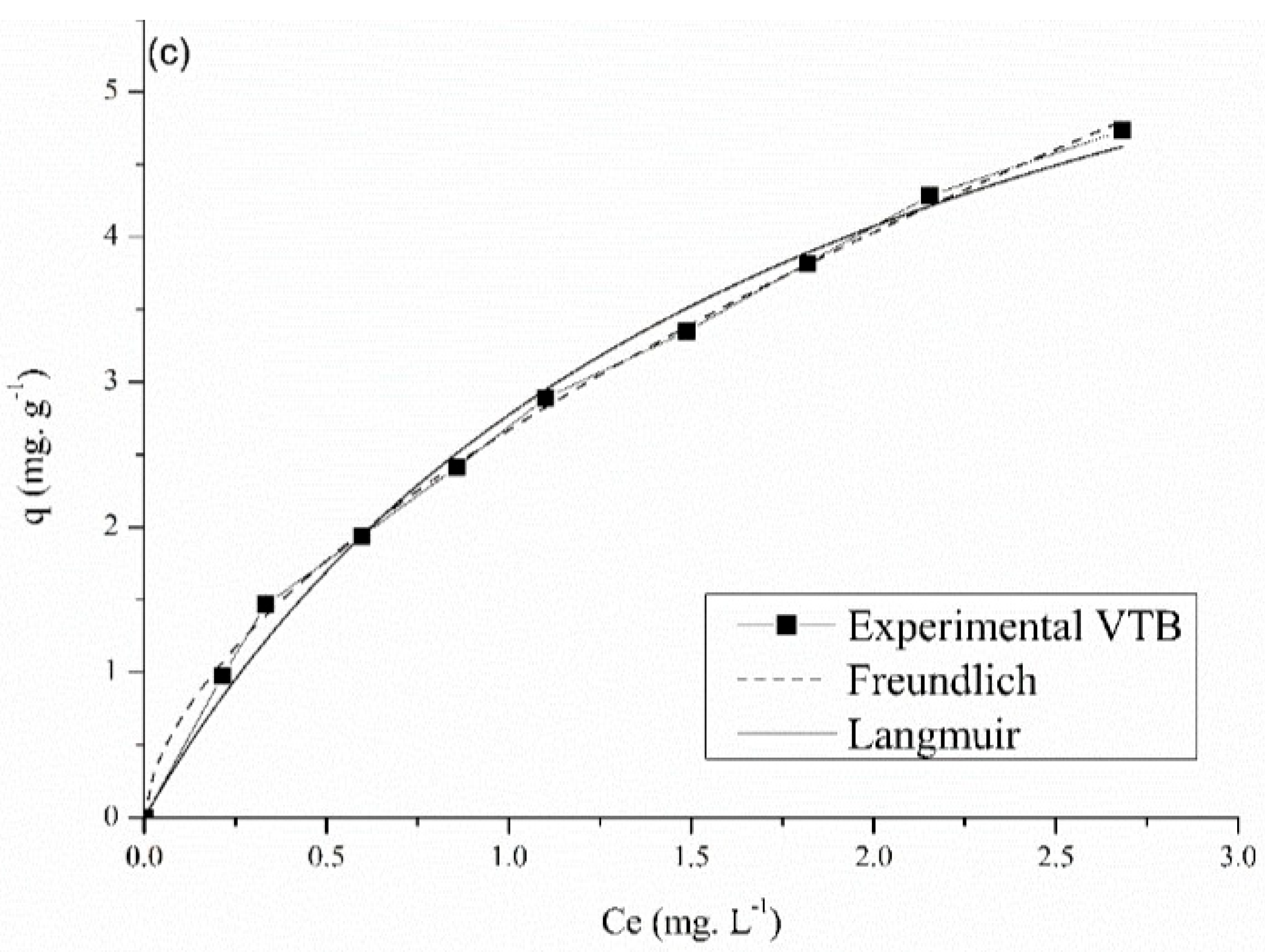

3.7. Equilibrium Isotherms

3.8. Biosorption Thermodynamics

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Abdeen, Z.; Mohammad, S.G.; Mahmoud, M.S. Adsorption of Mn (II) ion on polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan dry blending from aqueous solution. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarin, C.J. M.; Mascareñas, D. R.; Nolos, R.; Chan, E.; Senoro, D. B. Transition Metals in Freshwater Crustaceans, Tilapia, and Inland Water: Hazardous to the Population of the Small Island Province. Toxics 2021, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Moosa Hasany, S.; Bhanger, M.I.; Iqbal, S. Sorption potential of Moringa oleifera pods for the removal of organic pollutants from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarra, S.R.; Ali, E.N. and Yusoff, M. M. Removal of Heavy Metals by Natural Adsorbent. Int. J. Bios., 2014, 4, 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, V.N.; Coelho, N.M.M. Selective extraction and preconcentration of chromium using Moringa oleifera husks as biosorbent and flame atomic absorption spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2013, 109, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulos, I.; Kyzas, G.Z. Progress in batch biosorption of heavy metals onto algae. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 209, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.S. T.; Carvalho, D. C.; Rezende, H. C.; Almeida, I. L. S.; Coelho, L. M.; Coelho, N. M. M.; Marques, T. L.; Alves, V. N. Bioremediation of Waters Contaminated with Heavy Metals Using Moringa oleifera Seeds as Biosorbent. Patil, Y. (Ed.). (2013). Applied Bioremediation - Active and Passive Approaches. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A. P.; Valdiviezo-Gonzales, N. S. C. L.; Veneu, D. M.; Pino, A. H.; Torem, M. L. Comparative evaluation of lead and manganese removal from contaminated water using cocos nucifera shell powder in batch and continuous adsorption systems. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 53, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, N.; Nasernejad, B.; Ebadi, T. Removal of Mn(II) from groundwater by sugarcane bagasse and activated carbon (a comparative study): Application of response surface methodology (RSM). J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 3726–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, N.; Schneider, R.C. S.; Molin, D. D.; Riegel, G. Z.; Costa, A. B.; Corbellini, V. A.; Torres, J. O. M.; Malm, O. Environmental pathways and human exposure to manganese in southern Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2013, 85 (4).

- Ho, Y.S. and Mckay, G. The kinetics of sorption of basic dyes from aqueous solution by sphagnum moss peat. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 1998, 76, 822–827. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland, V.W.; Knocke, W.R.; Falkinham, J.O.; Pruden, A.; Singh, G. Effect of drinking water treatment process parameters on biological removal of manganese from surface water. Water Res. 2014, 66, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavathy, H. and Miranda, M. L.R. Moringa oleifera-A solid phase extractant for the removal of copper, nickel and zinc from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 158, 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kasaai, M.R. Use of Water Properties in Food Technology: A Global View. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1034–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Malik, R.N.; Muhammad, S. Human health risk from Heavy metal via food crops consumption with wastewater irrigation practices in Pakistan. Chemosphere, 2013, 93, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Gaur, J.P. Metal biosorption by two cyanobacterial mats in relation to pH, biomass concentration, pretreatment and reuse. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption gelster stoffe, Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens. Handlingar, 1898, 24, p. [Google Scholar]

- Lalhruaitluanga, H.; Jayaram, K.; Prasad, M.N. V, Kumar, K. K. Lead(II) adsorption from aqueous solutions by raw and activated charcoals of Melocanna baccifera Roxburgh (bamboo)-A comparative study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.L.; Alves, V.N.; Coelho, L.M.; Coelho, N.M.M. Removal of Ni(II) from aqueous solution using Moringa oleifera seeds as a bioadsorbent. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.F.B. C.; Ribeiro, M. H. G.; Albuquerque Junior, E. C.; Gonçalves, E. A. P. Avaliação da Bacia do Rio Una-Pernambuco: Perspectiva da Qualidade da Água após a Construção de 4 Barragens para Contenção de Cheias Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física, 2018, 11, 612-627.

- Meneghel, A.P.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Rubio, F.; Dragunski, D.C.; Lindino, C.A.; Strey, L. Biosorption of cadmium from water using moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam. ) Seeds. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollo, V. M.; Nomngongo, P. N.; Ramontja, J. Evaluation of Surface Water Quality Using Various Indices for Heavy Metals in Sasolburg, South Africa. Water, 2022, 14, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjardin, C. E. , Power, C. , & Senoro, D. B. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Manganese Contamination in Relation to River Morphology: A Study of the Boac and Mogpog Rivers in Marinduque, Philippines. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 8276. [Google Scholar]

- Nwagbara, V. U.; Iyama, W. A.; Chigayo, K.; Kwaambwa, H. M. Efficiency of Moringa Oleifera Seed Biomass in the Removal of Lead (II) Ion in Aqueous Solution. Eur. J. Appl. Sci, 2022, 10, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Guzman, C.; Otalvaro-Alvarez, A.; Jimenez-Ariza, T. Use of oilseed crops biomass for heavy metal treatment in water. Oil Crop Science 9, 2024, 177–186.

- Peng, C.-Y.; Korshin, G. V. , Valentine, R. L., Hill, A.S., Friedman, M.J., Reiber, S.H. Characterization of elemental and structural composition of corrosion scales and deposits formed in drinking water distribution systems. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4570–4580. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Dong, Z.; Naidu, R. Concentrations of arsenic and other elements in groundwater of Bangladesh and West Bengal, India: Potential cancer risk. Chemosphere, 2015, 139, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. , Molla, A. H., Saha, N., Rahman, A.. Study on heavy metals levels and its risk assessment in some edible fishes from Bangshi River, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.H.K.; Seshaiah, K.; Reddy a, V.R.; Lee, S.M. Optimization of Cd(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) biosorption by chemically modified Moringa oleifera leaves powder. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, A.; Ghanbarizadeh, P.; Mirvakili, A.; Moheimani, N.R. Optimizing heavy metal remediation of synthetic wastewater using Chlorella vulgaris and Sargassum angustifolium: A comparative analysis of biosorption and bioaccumulation techniques. STOTEN, 2025, 992, 179938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M. O.; Camacho, F. P.; Ferreira-Pinto, L.; Giufrida, W. M.; Vieira, A. M. S.; Visentainer, J. V.; Vedoy, D. R. L.; Cardozo-Filho, L. Extraction and Phase Behaviour of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil Using Compressed Propane. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 94, 2195–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffarel, S.R.; Rubio, J. Removal of Mn2+ from aqueous solution by manganese oxide coated zeolite. Miner. Eng. 2010, 23, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsadi, H.; Khalidi, A.; Abdennouri, M.; Barka, N. Biosorption potential of Diplotaxis harra and Glebionis coronaria L. biomasses for the removal of Cd(II) and Co(II) from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usepa 2004 Drinking Water Health Advisory for Manganese in:, U.S. Usepa 2004 Drinking Water Health Advisory for Manganese in:, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of WaterWashington, DC EPA-822-R-04-003. pp. 1–49.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid)/montmorillonite superadsorbent nanocomposite. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 322, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.N.; Aslam, I.; Nadeem, R.; Munir, S.; Rana, U.A.; Khan, S.U.-D. Characterization of chemically modified biosorbents from rice bran for biosorption of Ni(II). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 46, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element (%) | ||||||

| Biosorbents | C | O | Mg | Al | Ca | Mn |

| VAI | 53.79 | 45.51 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| VTA | 53.93 | 45.11 | 0.0 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.55 |

| VTB | 52.00 | 47.39 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Biosorbents |

Qeexp (mg g-1) |

Pseudo-first-order | ||

| Qt cal (mg g-1) | K1 (min-1) | R2 | ||

| VAI | 0.34 | 0.32±0.00 | 1.40±0.09 | 0.998 |

| VTA | 0.24 | 0.24±0.01 | 0.37±0.04 | 0.979 |

| VTB | 0.37 | 0.37±0.00 | 1.75±0.08 | 0.999 |

| Pseudo- second-order | ||||

| Qt cal (mg g-1) | K2(g mg-1min-1) | R2 | ||

| VAI | 0.32±0.00 | 19.56±1.10 | 0.999 | |

| VTA | 0.25±0.00 | 2.33±0.19 | 0.996 | |

| VTB | 0.37±0.00 | 36.45±1.25 | 0.999 | |

| Biosorbents | Langmuir | Freundlich | ||||

| qmax (mg g-1) |

KL (L mg -1) |

R2 | Kf (mg1-1/n L1/n g-1) |

n | R2 | |

| VAI | 6.00±0.25 | 0.14±0.01 | 0.99 | 0.95±0.02 | 1.74±0.04 | 0.99 |

| VTA | 3.60±0.42 | 0.07±0.02 | 0.97 | 0.43±0.32 | 1.88±0.94 | 0.99 |

| VTB | 7.64±0.50 | 0.57±0.07 | 0.99 | 1.68±0.04 | 2.67±0.02 | 0.99 |

|

Biosorbent |

(KJ. mol-1) |

ΔH° (KJ.mol-1) |

ΔS° (J. mol -1.K-1) |

|||

| 288 K | 298 K | 308 K | 318 K | |||

| VAI | 9.34 | 12.18 | 14.85 | 15.71 | 11.88 | 52.10 |

| VTA | 1.08 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.08 | 7.49 |

| VTB | 6.12 | 6.64 | 6.95 | 7.67 | 8.94 | 51.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).