1. Introduction

The current challenge the world is facing today is that of waste and pollution of the environment. In a linear economy, natural resources are extracted, processed and ultimately stored as waste. At the end of life, the material (now termed waste) is either deposited in landfills or incinerated. In circular economy the problem of waste and pollution is combated by application of “3 Rs”: Reduction (demand and / or consumption of resources materials and products, Reuse and Recycling.

Food waste, due to its valuable compounds, has gained attention in various applications related to quality of life and environmental concerns. In line with circular economy principles, we propose a valorization method for banana waste by converting it into advanced adsorbents.

Antibiotics in wastewater are a growing concern due to their potential to create antibiotic-resistant genes [

1]. Adsorption has emerged as a promising, cost-effective method for removing antibiotics from water [

2]. Various adsorbents have been studied, with carbon-based materials like biochar, activated carbon, and carbon nanotubes showing high efficiency [

1,

2,

3]. Banana waste, an abundant and low-cost biomass, has gained attention as a precursor for producing effective adsorbents[

4]. A recent study demonstrated that biochar derived from banana peel and activated with potassium hydroxide (KOH-BPB) exhibited a high surface area and effectively removed doxycycline from aqueous solutions, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 121.95 mg g⁻¹ [

5]. This research highlights the potential of banana waste-derived biochar as an environmentally friendly and efficient adsorbent for antibiotic removal from wastewater.

Banana peels and banana peel-based materials have been extensively studied for their potential in removing various pollutants from aqueous solutions. Banana peels have been used as a low-cost biosorbent due to their high adsorption behaviour, attributed to the presence of adsorption active sites and natural components such as lignin and cellulose [

6]. They have been used for the biosorption of pollutants from water, with pH 5.0 to 7.0 being favourable for the removal of cationic pollutants, and pH 2.0 to 4.0 suitable for anionic pollutants[

7]. Removal of Heavy Metals: Banana peels have been used for the removal of heavy metals such as Cr, Cu, Pb, and Zn from synthetic solutions[

8]. Acid-modified banana peels have shown high removal performances for Cr (VI) from wastewater[

9]. Removal of Dyes: Activated carbon synthesized from banana peels has been used for dye removal from aqueous solutions in textile industries [

10]. Banana peel-based materials have been used for removing pharmaceuticals, namely amoxicillin and carbamazepine, from different water matrices [

11]. In conclusion, banana peels and banana peel-based materials have shown promising results in the removal of various pollutants, including antibiotics, from aqueous solutions. Their low cost, availability, and high adsorption capacity make them an attractive option for wastewater treatment. However, more research is needed to fully understand their potential and limitations in real-world applications.

Banana peel-based adsorbents have shown promising results in removing antibiotics from wastewater. Studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in adsorbing various antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin and doxycycline [

12,

13]. The adsorption capacity can be enhanced through modifications such as biochar production and chemical activation [

12,

13]. Factors affecting adsorption include pH, contact time, initial antibiotic concentration, and adsorbent dose [

12,

13]. The adsorption process typically follows pseudo-second-order kinetics and Langmuir isotherms [

12]. Banana peel-based adsorbents have shown removal efficiencies of up to 98% for heavy metal ions and 98.93% for organic and inorganic compounds (Huzaisham et al., 2020). These adsorbents offer a cost-effective and sustainable solution for antibiotic removal from wastewater, with the potential for regeneration and reuse [

12,

14].

In this work spherical beads were produced by encapsulating various forms of banana peel-based particles in sodium alginate beads. The beads were evaluated as potential adsorbents for the removal of pharmaceutical products and heavy metals from wastewater. Tetracycline and hexavalent chromium as model pollutants for antibiotics and heavy metals respectively.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

Otho-phosphoric acid (H3PO4), Potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3.9H2O), iron (II) sulphate heptahydrate (FeSO4.7H2O), sodium hydroxide(NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl), calcium chloride (CaCl); were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich, (Gillingham, United Kingdom). Sodium alginate (NaC6H7O6) was purchased from Fisher Scientific UK Ltd, (Loughborough United Kingdom).

2.2. Production of Biochar

In preparation for the procedure, the banana peel was washed with deionized water and dried before undergoing size reduction by blending, achieving an average particle size of 125 µm. In brief, the samples were pre-treated by soaking and saturating with orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4) at an 85% concentration, using an acid-to-sample ratio of 1:1. The samples were then mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 1 hour to ensure homogeneity.

Subsequently, the samples underwent a two-step heating process. First, they were subjected to a temperature of 150°C for 2 hours, followed by a further 2 hours in a furnace under a flow of nitrogen at 400°C. After cooling, the samples were washed with water and dried for 24 hours.

2.3. Preparation of Magnetic Biochar

The biochar was then activated using iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate and iron(II) sulfate heptahydrate. Specifically, 1 g of biochar was suspended in a 500 mL solution containing 3.5 g of Fe(NO3)3 and 1.3 g of FeSO4·7H2O. The suspension was sonicated at 40 W for 10 minutes. To precipitate the iron oxide, an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH; 0.1 mol) was added drop wise until the pH reached between 11 and 12. The mixture was then vigorously stirred at 50°C for 1 hour. Subsequently, the precipitate was separated from the aqueous dispersion by filtration and washed repeatedly with double-distilled water until the pH was neutral. The magnetic activated carbon was then dried and sealed in a container for later use.

2.4. Preparation of Adsorbent Beads

The beads were produced from four different materials: pure sodium alginate powder, 1:1 blends of sodium alginate powder with powdered banana peel (PBP), banana peel activated powder (AC), and magnetic activated carbon (MAC). These materials were respectively named NaAlg, PBP@NaAlg, AC@NaAlg, and MAC@NaAlg. Spherical adsorbent beads were synthesized using the following gelation procedure:

Mixing: First, 4 g of sodium alginate powder was thoroughly mixed with 4 g of the various materials (including unmodified banana peel, activated carbon, and magnetic activated carbon) in a weigh boat. The resulting mixed powder was slowly added to 400 mL of deionized water while continuously stirring. The mixture was left in the beaker overnight to ensure homogeneity.

Calcium Chloride Solution: Next, a 2 wt% solution of calcium chloride was prepared by dissolving calcium chloride in 400 mL of deionized water. This solution was maintained at room temperature on a hot plate.

Drop-Wise Addition: While the calcium chloride solution was magnetically stirred, the various material solutions were passed through a pear-shaped separating funnel and added dropwise to the beaker.

Gelation Process: Following the gelation process, the beads formed were subjected to gentle magnetic stirring at 350 rpm for 24 hours in their mother liquor.

Harvesting and Drying: Finally, the beads were harvested by filtering the calcium chloride solution and washing them several times with deionized water. Subsequently, the beads were dried at room temperature in a fume cupboard.

2.5. Characterization

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy was employed to identify the functional groups of each sample before and after adsorption, within the range of 4000–600 cm-1. Additionally, X-ray diffraction (XRD) tests were performed using a Philips PANalytical X'pert Pro diffractometer to determine the crystalline and amorphous characteristics of the best adsorbent sample. Surface area and porosity information for each sample were obtained through Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis at 77K, using a Micromeritics Tristar 3020 instrument with nitrogen gas flow. The thermal stability of the samples was assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under nitrogen gas flow, starting at room temperature and heating to 800 °C at a rate of 5 K min-1.

2.6. Adsorption Trials

The different samples of adsorbent beads were tested for the adsorption of chromium and tetracycline. Each sample was contacted with aqueous solutions of either chromium or tetracycline with an initial concentration of 150ppm. The residual concentration of the solutions of chromium and tetracycline were measured using UV spectrophotometry at wavelengths of 540 and 357 nm respectively.

The concentration of the pollutant loaded onto the adsorbent was calculated from the initial concentration,

, residual concentration

, mass of adsorbent sample

and volume of solution

using (1):

The removal efficiency of the adsorbent was calculated from.

The symbols in (2) are as defined previously.

From the adsorption isotherm study the adsorbents were contacted with solutions of the pollutant with various concentrations ranging from 25 to 150 ppm.

2.7. Initial Concentration Effect and Isotherm Modelling

Solutions of chromium with concentration ranging from 25 to 150 ppm (in 25 ppm increments) were prepared from the stock solutions. The pH of the solution where adjusted to pH 2 using either HCL or NaOH. The 20 ml of these solutions were transferred into 6 separate glass vails and 50 mg of the adsorbent PBP beads. This was repeated for the other types of beads. The vails were placed on the shaker at 100 rpm for agitation for a contact time of 24 hours. At the end of the contact time the beads were filtered from the solution and dried for stored for future characterization. A sample were taken from the filtrate and diluted for concentrations determination by UV-Vis spectroscopy using procedure previously reported {Huang, 2024 #46}. 6 ml of each sample was mixed with 2ml of colour development reagent. UV analysis was performed at a wavelength of 540 nm. The same procedure was repeated for the tetracycline, the only difference in the procedure was that no pH adjustment of the solution was required and also no colour development reagent was required prior to UV analysis. The UV analysis was done at a wavelength of 357 nm. Equation (1) was used to calculate qe values.

Isotherm models play a critical role in understanding the interactions between adsorbates and adsorbents. They provide valuable insights into the adsorption capacity of the material, helping to identify the most efficient and cost-effective adsorbent for specific applications. These models also enable the prediction of adsorption performance under varying conditions, which is essential for scaling up laboratory findings to industrial processes.

The data were analyzed using several isotherm models, including Freundlich (3), Langmuir (4).

In equations (3) to (4) where Ce (mmol/L) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate solution; qm (mmol/g) is the maximum amount of adsorbate removed by the adsorbent; qe is the removal capacity at equilibrium (mmol/g); KL (L/mmol) and KF ([mmol.g-1]/[mmol.L-1]1/n) are the Langmuir constant related to the interaction bonding energies and the Freundlich affinity coefficient,

The model parameters were obtained from non-linear regression fits of the isotherm models to the experiment data using custom MATLAB code.

2.8. Re-Use of the Beads

After the adsorption tests, the beads were recovered from the solution through filtration. They were then dried in an oven at 60°C and stored in sealed jars until further use. The beads originally used for tetracycline adsorption were subsequently evaluated for Cr(VI) adsorption, and vice versa.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization Results

- 2.

Ultimate analysis

A CHNS elemental analysis was conducted on powdered banana peel, AC@NaAlg, and MAC@NaAlg. The results, presented in

Table 1, show the total percentages of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur in the samples. The analysis reveals a decrease in carbon content from the initial material, ‘BPP,’ which had a carbon content of 39.38%, to AC@NaAlg with 24.71%, and finally to the synthesized material MAC@NaAlg, which had the lowest carbon content at 19.89%.

This reduction in carbon content from the banana peel to the activated carbon can be attributed to the activation process. The high temperatures and the use of the activating agent H

3PO

4 remove non-carbon components such as ash and various volatile organic compounds. The carbon content of the banana peel powder aligns with values reported in the literature by [

15], which indicate a carbon content of 47.5%. The hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur contents were like those reported in

Table 1.

- 3.

Analysis of functional groups through FTIR

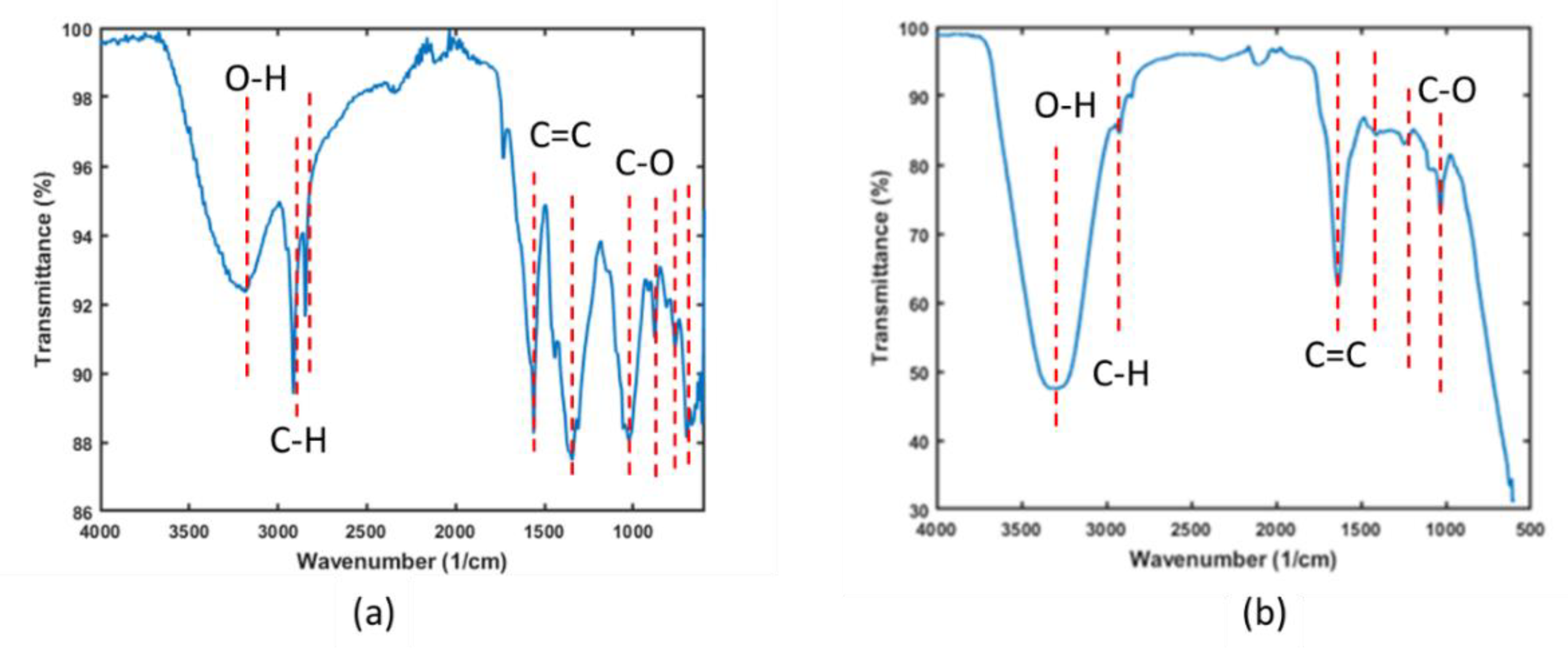

The FTIR spectra presented in

Figure 1 illustrates the functional groups present in both the banana peel powder and the final product, magnetic activated carbon beads. The spectra reveal hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in the banana peel sample, with bands at 3350 cm⁻¹ and 2800 cm⁻¹, respectively.

The band around 1680 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the asymmetric C=C stretch from the ether group [

16]. In the BPP sample, the band at approximately 1010 cm⁻¹ indicates the presence of C-O, C-OH, and C-C stretching, corresponding to the hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in the banana peel powder [

17]. Weak bands observed at around 800 to 600 cm

-1 are attributable to amine groups.

- 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis

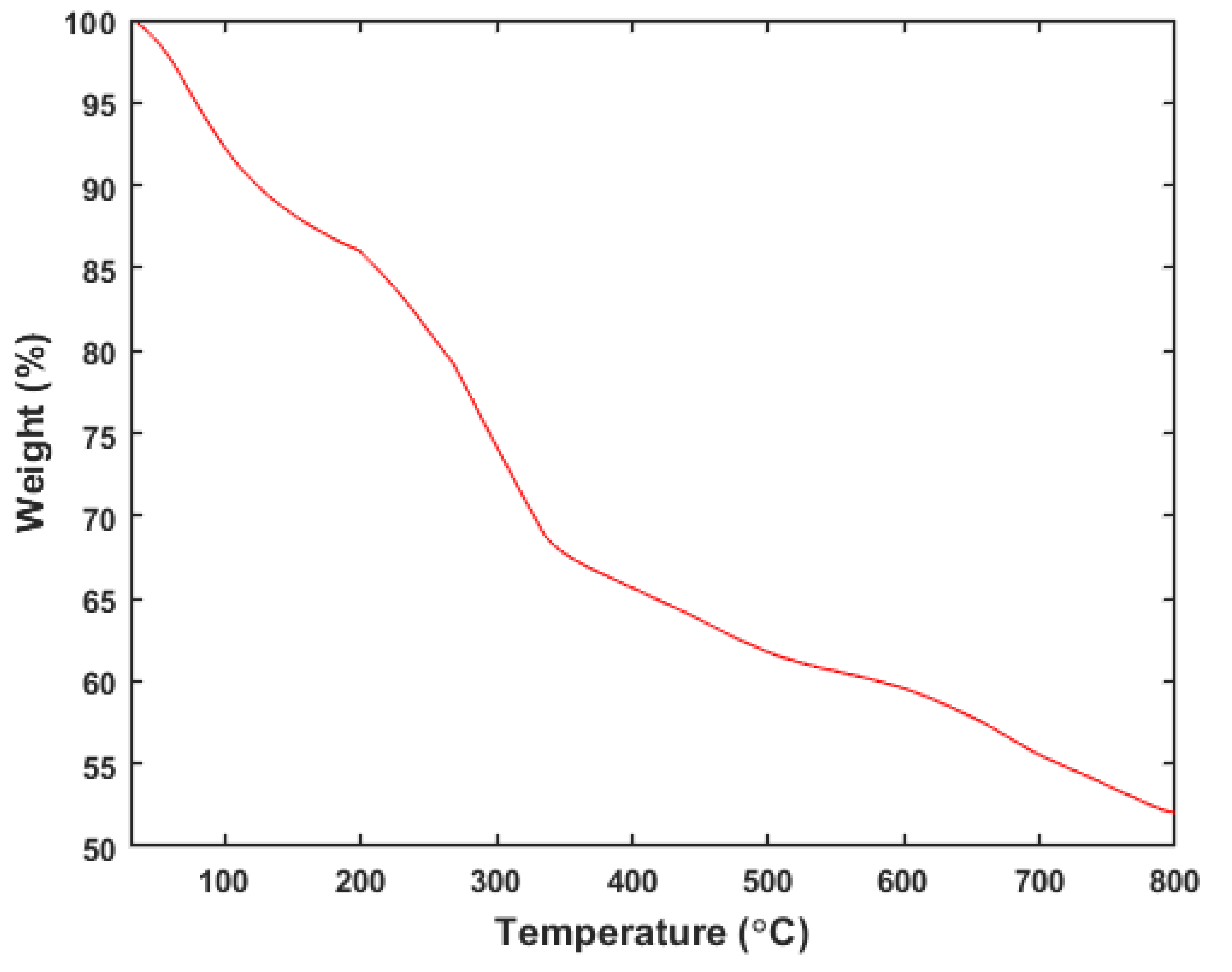

Figure 2 presents the Thermogravimetric (TG) curve for the magnetic activated carbon (MAC) beads, which were obtained at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. As depicted in

Figure 2, a decrease in sample weight of approximately 10% is observed when the temperature is increased from room temperature to 120 °C. This reduction in sample weight is primarily due to the evaporation of water from the beads.

Upon further heating of the sample, a significant weight loss of around 20% occurs between 200 and 320 °C, followed by another decrease in the range of 330 to 600 °C. The weight loss in the first range is indicative of the decomposition of cellulose and hemicellulose in the bead, which originate from the banana peel powder used in the production of the beads [

18].

The subsequent weight loss at higher temperatures can be attributed to the decomposition of other components, such as lignin [

19]. The results demonstrate that the MAC@NaAlg beads exhibit thermal stability up to approximately 180 °C.

3.2. Comparison of Adsorption Performance

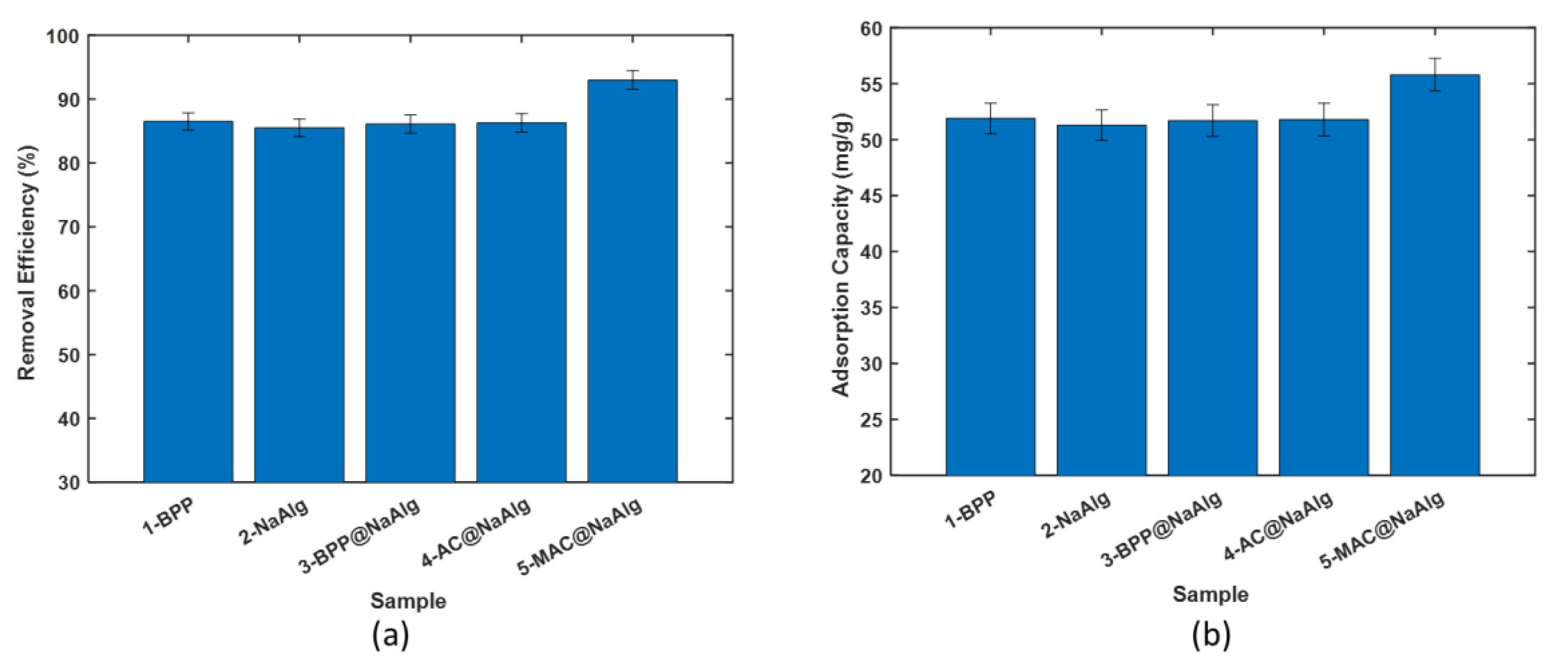

5. Removal of TC with the virgin powder & the beads

Figure 3 (a) presents the comparison of the removal efficiency of various bead types in treating aqueous solutions of tetracycline. The beads demonstrated removal efficiency ranging from 85 to 92%. The highest efficiency was achieved using magnetic activated beads as the adsorbent. Interestingly, the other four bead types achieved a removal efficiency of approximately 86%, with no significant difference among them. This data underscores the benefits of incorporating magnetic nanoparticles into the activated carbon used to create the MAC@NaAlg beads.

Remarkably, despite differences in particle size, the removal efficiency of banana peel powder was comparable to that of NaAlg. Figure3 (b) displays the amount of tetracycline captured by the beads during the removal process, as calculated using (1). The trends observed here mirror those seen in the removal efficiency.

The adsorption capacities of BPP, NaAlg, BPP@NaAlg, and AC@NaAlg were all around 52 mg/g, with the differences between them being statistically insignificant. However, the removal capacity of MAC@NaAlg was significantly higher than the other four materials.

- 6.

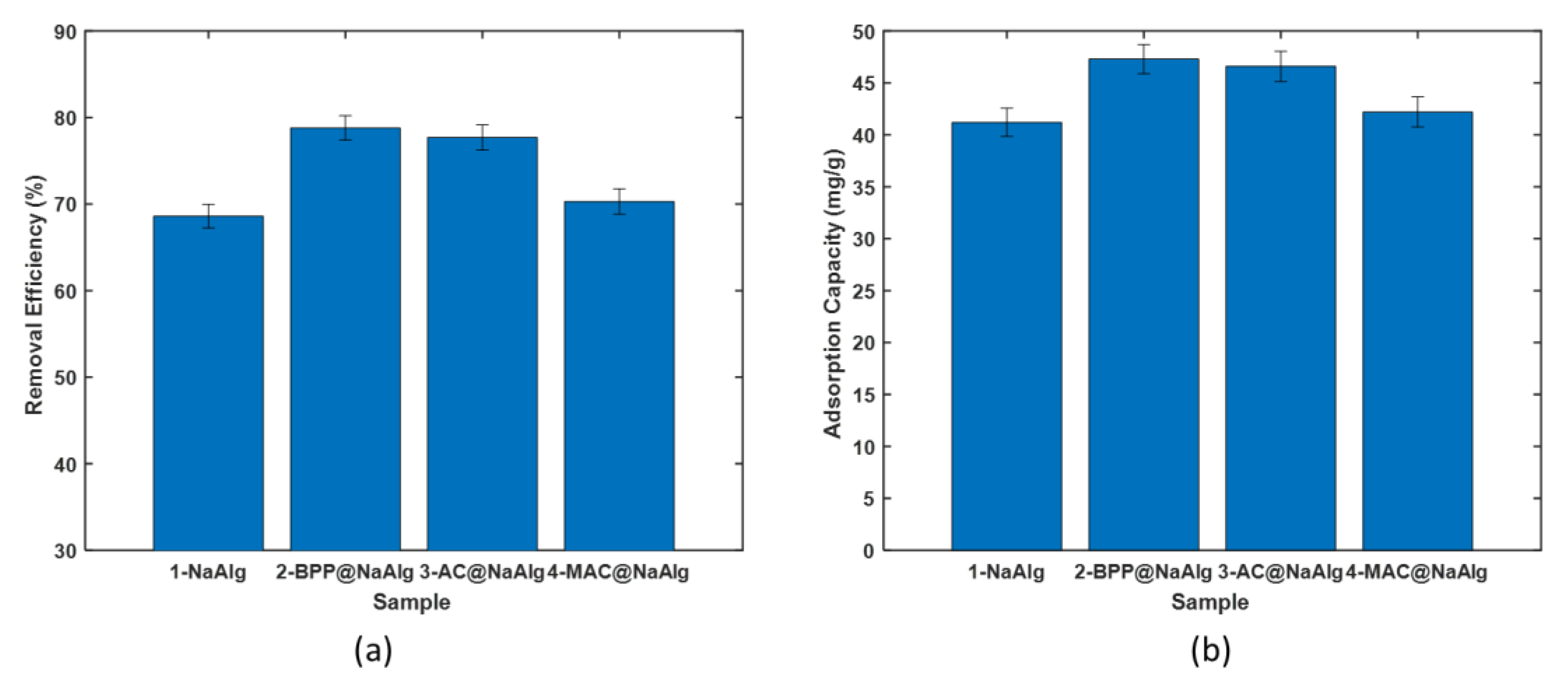

Removal of Cr(VI) with the virgin beads

The comparison of removal efficiency among various bead types for treating aqueous solutions of chromium (VI) is presented in

Figure 4 (a). The beads exhibited a removal efficiency ranging from 68% to 79%. Notably, the removal efficiency was significantly higher for beads encapsulating other materials than for pure sodium alginate beads. The highest efficiency was achieved using magnetic activated beads (MAC) as the adsorbent. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in removal capacities between BPP@NaAlg, BPP@NaAlg, and AC@NaAlg beads.

Figure 4 (b) illustrates the amount of chromium (VI) captured by the beads during the removal process, reflecting trends similar to the removal efficiency. The adsorption capacities of NaAlg, BPP@NaAlg, and AC@NaAlg fell within the range of 41 to 47 mg/g. Pure sodium alginate beads exhibited the lowest adsorption capacity, approximately 41 mg/L.

3.3. Effect of Initial Concentration Study

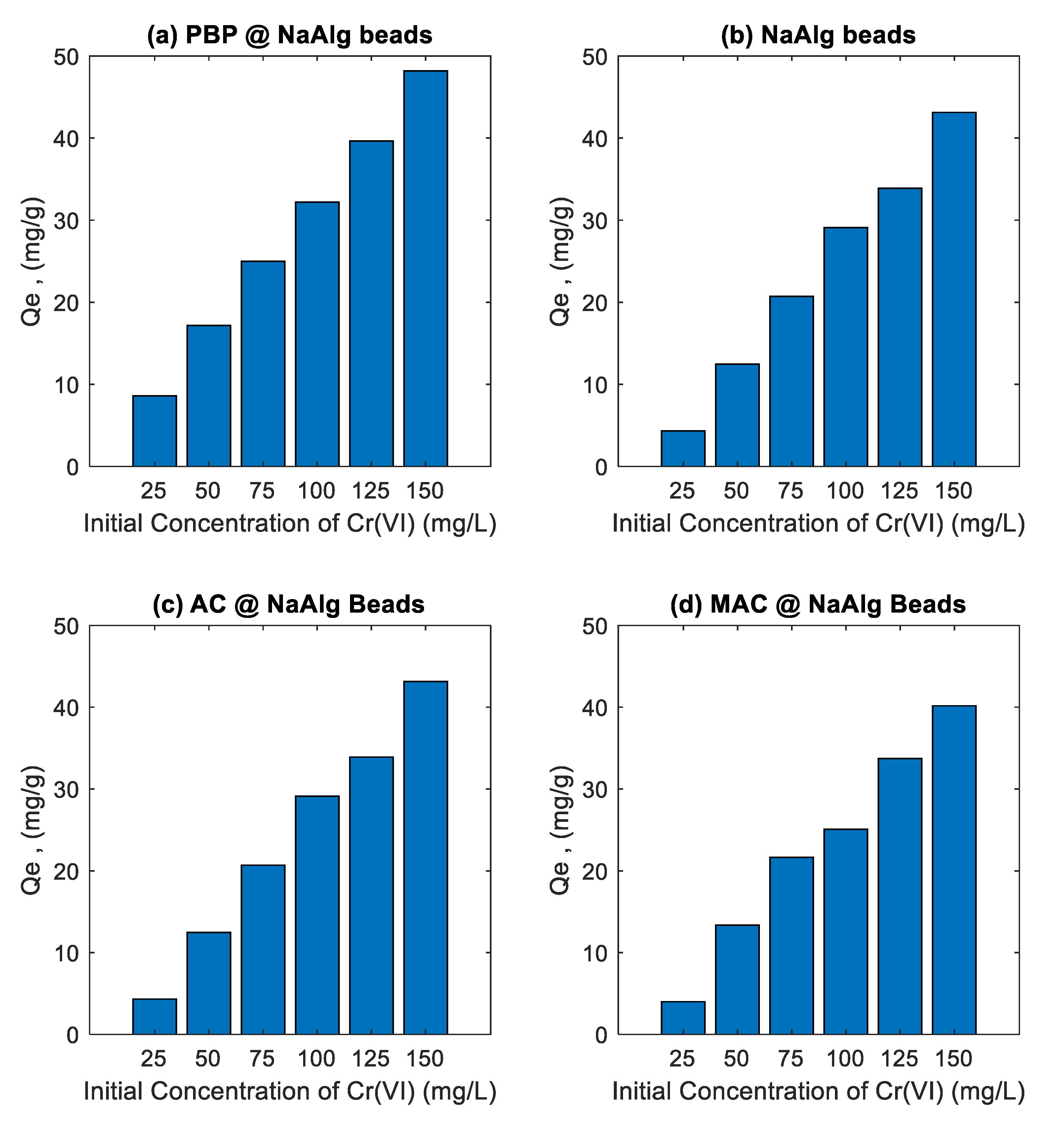

The

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of initial Cr(VI) concentration on the adsorption capacity (Qe) of various banana peel-based adsorbent beads, including sodium alginate beads (NaAlg), activated carbon-loaded sodium alginate beads (AC@NaAlg), magnetic activated carbon beads (MAC@NaAlg), and powdered banana peel beads (PBP@NaAlg). Across all adsorbents, the adsorption capacity increased as the initial Cr(VI) concentration increased from 25 to 150 mg/L. This trend is expected because higher initial Cr(VI) concentrations provide a greater driving force for mass transfer, enhancing adsorption onto the surface of the beads.

Among the tested materials, AC@NaAlg and MAC@NaAlg exhibited the highest adsorption capacities, suggesting that the incorporation of activated carbon, especially in its magnetic form, significantly enhances adsorption performance. This improvement can be attributed to the high surface area, porosity, and functional groups of activated carbon, which facilitate Cr(VI) uptake through both physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms [

24] Similarly, PBP@NaAlg demonstrated a relatively high adsorption performance, which may be due to the functional groups present in banana peel powder, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, that interact with Cr(VI) ions [

25]. In comparison, the pure sodium alginate beads (NaAlg) showed the lowest adsorption capacity, highlighting the limited adsorption potential of alginate alone. This suggests that incorporating fillers like activated carbon or banana peel powder into the alginate matrix significantly improves the adsorption efficiency.

The observed adsorption capacities of AC@NaAlg and MAC@NaAlg align well with previous studies. For instance, magnetic activated carbon composites have been shown to exhibit high Cr(VI) adsorption capacities due to their high surface area and magnetic properties, which facilitate adsorption and subsequent separation [

26,

27]. Additionally, agricultural waste-based adsorbents, such as modified biochar and banana peel-derived adsorbents, have demonstrated adsorption capacities ranging from 20 to 50 mg/g under similar conditions, depending on the preparation method and experimental setup [

28,

29]. The results in the current study suggest that MAC@NaAlg and AC@NaAlg are promising adsorbents for Cr(VI) removal, performing comparably or even superior to conventional and agricultural waste-based materials reported in the literature.

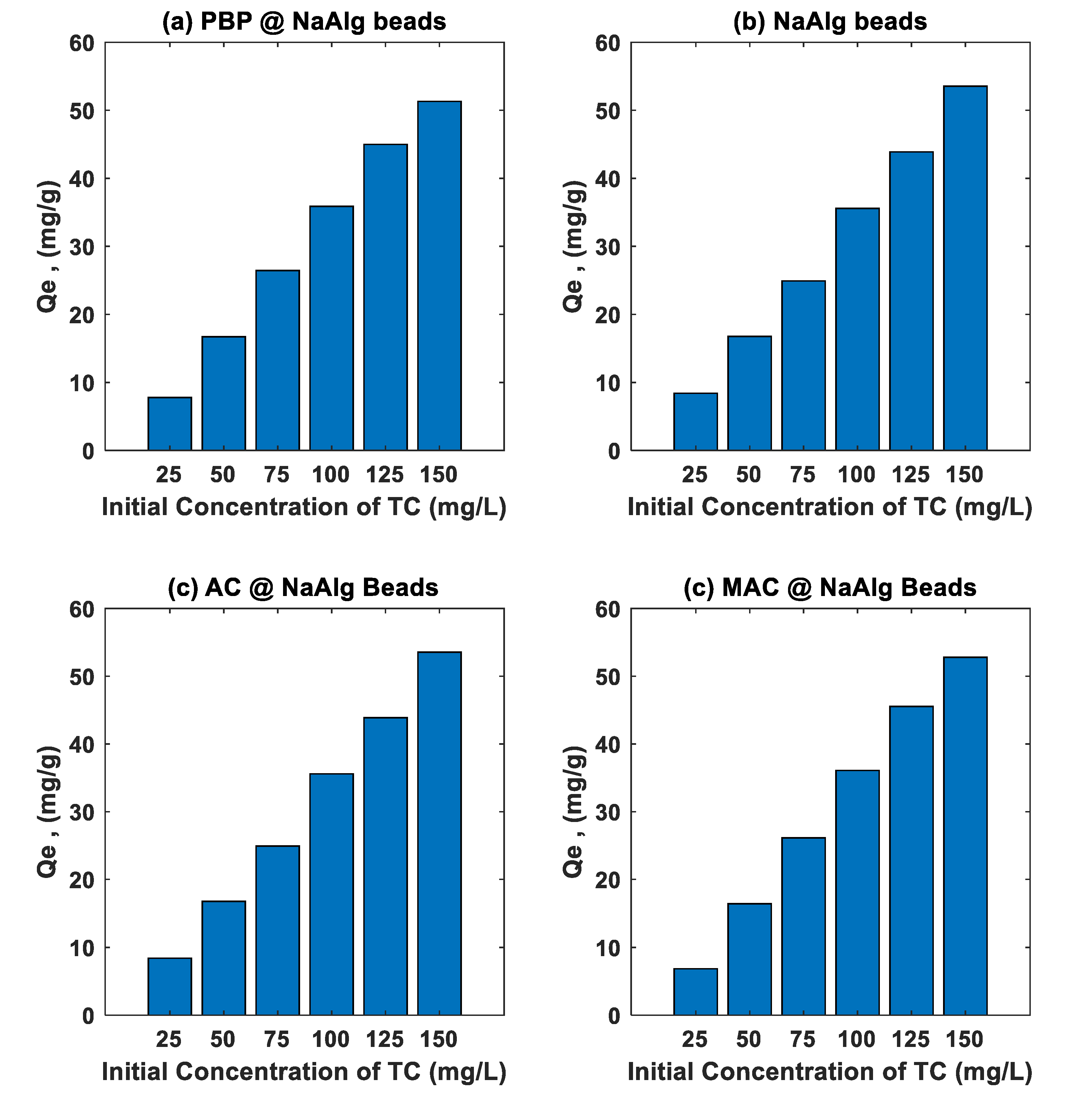

The

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of initial tetracycline (TC) concentration on the adsorption capacity (Qe) of various banana peel-based adsorbent beads, including sodium alginate beads (NaAlg), activated carbon-loaded sodium alginate beads (AC@NaAlg), magnetic activated carbon beads (MAC@NaAlg), and powdered banana peel beads (PBP@NaAlg). The adsorption capacity of all materials increased with increasing initial TC concentration (25–150 mg/L) after 24 hours of contact time with a fixed bead dosage of 2.5 g/L. This behaviour can be attributed to the greater driving force for mass transfer at higher initial concentrations, which enhances the interaction between TC molecules and the adsorbent surfaces.

Among the tested materials, AC@NaAlg and MAC@NaAlg exhibited the highest adsorption capacities, demonstrating the superior adsorption performance provided by the presence of activated carbon. The high surface area and porosity of activated carbon facilitate the effective adsorption of TC molecules via π-π interactions, electrostatic attractions, and hydrogen bonding [

30]. The incorporation of magnetic properties in MAC@NaAlg further enhances its potential due to improved accessibility and separation efficiency after adsorption [

27]. Meanwhile, PBP@NaAlg demonstrated relatively good adsorption performance, which can be attributed to the functional groups present in banana peel powder (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amine groups) that interact with TC molecules [

31]. The pure sodium alginate beads (NaAlg) exhibited the lowest adsorption capacity, suggesting that the alginate matrix alone has limited active sites for TC adsorption.

The adsorption capacities of AC@NaAlg and MAC@NaAlg observed in this study are consistent with values reported for other advanced adsorbents in the literature. For example, biochar-derived adsorbents and magnetic composites have shown adsorption capacities ranging from 30 to 60 mg/g, depending on preparation methods and experimental conditions [

3]. The performance of MAC@NaAlg in this study is particularly noteworthy, as it rivals other magnetic adsorbents like magnetic biochar, which are widely recognized for their efficiency in antibiotic removal from aqueous solutions [

32]. Similarly, agricultural waste-based adsorbents, such as modified banana peel and corncob-derived materials, have exhibited adsorption capacities in the range of 20–50 mg/g under comparable conditions[

31].

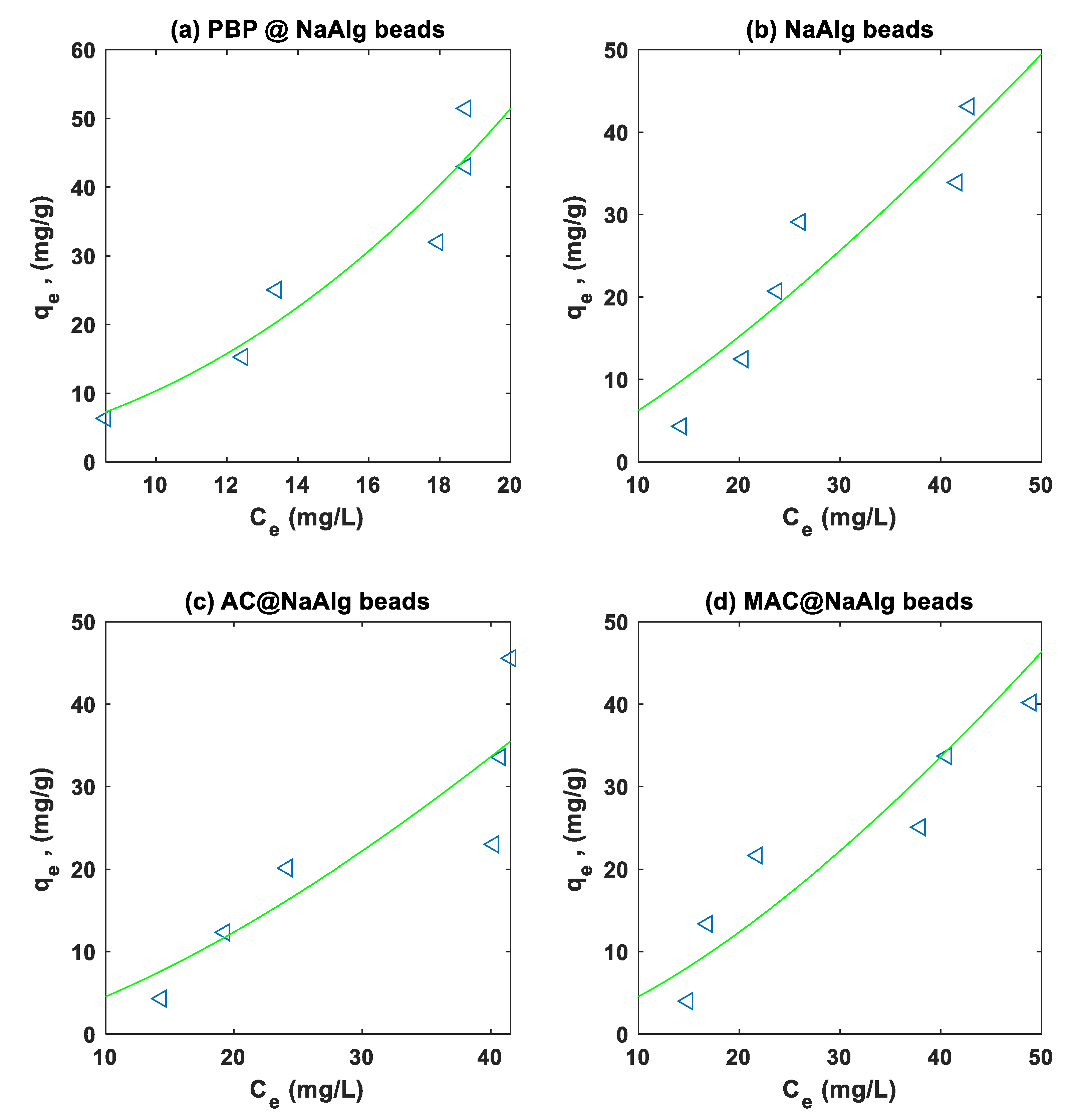

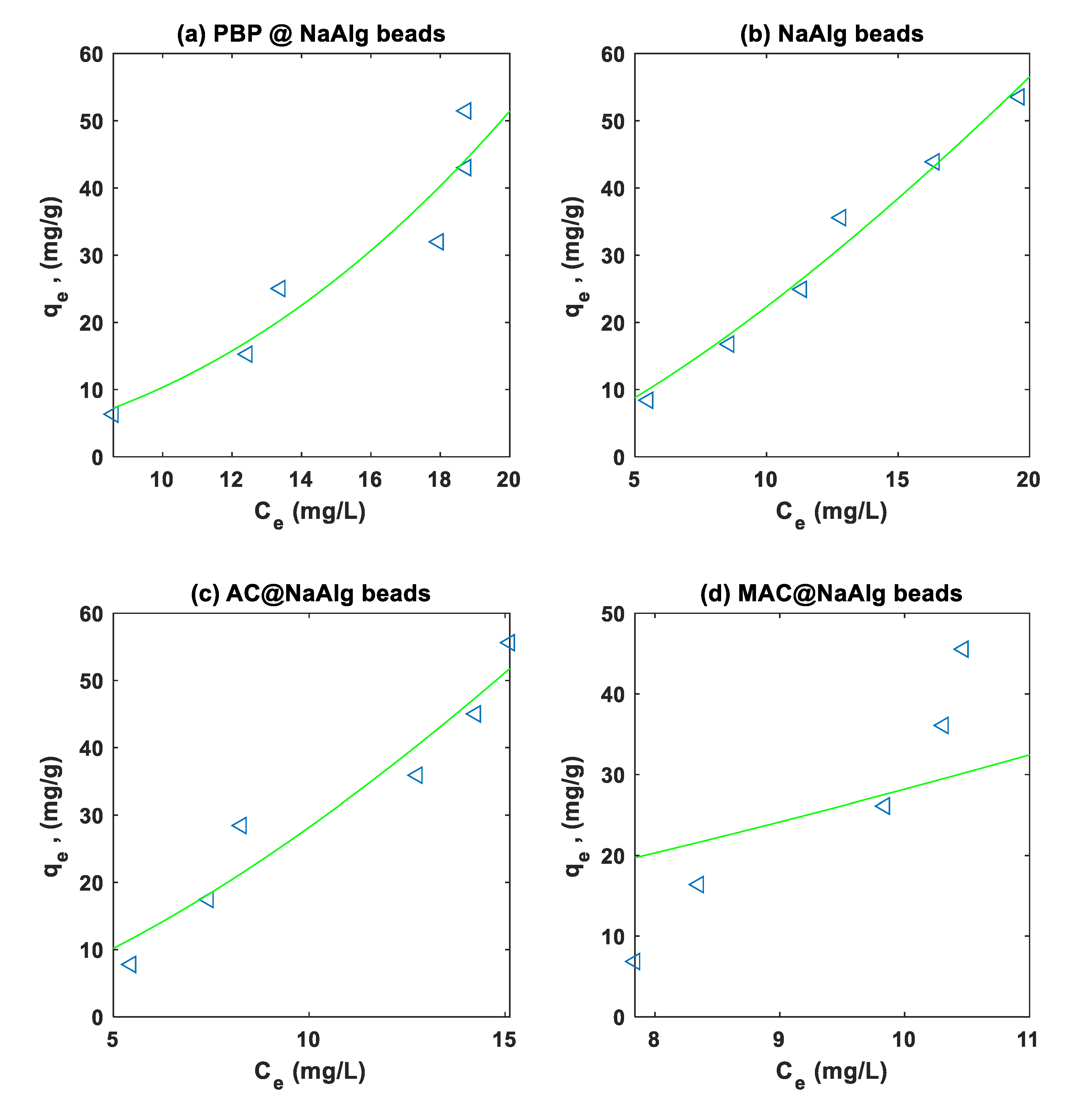

3.4. Isotherm Modelling

The Langmuir and Freundlich models were fitted to the experimental on the adsorption of Cr and TC using non-linear regression. Summary of the regression parameters for the different type of beads is presented in

Table 2. The Freundlich non-linear regression fits to the Cr(VI) and TC experimental data are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 respectively.

The

Table 2 presents the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm parameters obtained from fitting experimental data for the adsorption of tetracycline (TC) and chromium (Cr(VI)) onto four different types of beads: NaAlg, PBP@NaAlg, AC@NaAlg, and MAC@NaAlg. For Cr(VI) adsorption, the Langmuir model shows that MAC@NaAlg has the highest adsorption capacity (

) of 155.5158 with a Langmuir constant (

) of 0.0113, and a strong fit indicated by an (

) value of 0.9519. In contrast, NaAlg has a lower (

) of 1.322e+04 and a K_L of 6.740e-05, with an (

) value of 0.7693, indicating a moderate fit. The Freundlich model reveals that PBP@NaAlg exhibits the highest Freundlich constant (

) of 3.4473 and a heterogeneity factor (n) of 1.2983, with a strong fit demonstrated by an (

) value of 0.9835.

Regarding TC adsorption, the Langmuir model indicates that MAC@NaAlg has the highest () of 8.7443e+04 with a ( ) of 3.5910e-05 and a moderate fit shown by an () value of 0.6215. NaAlg, on the other hand, has a ( of 3.174e+04 and a ( ) of 8.108e-05, with an () value of 0.9315, suggesting a strong fit. The Freundlich model shows that NaAlg has a of 0.8087 and an n of 0.7067, with an excellent fit indicated by an () value of 0.9972. Overall, the results demonstrate that PBP@NaAlg and MAC@NaAlg beads generally exhibit better adsorption performance for both Cr(VI) and TC compared to NaAlg and AC@NaAlg beads, as evidenced by higher () values and lower RMSEs.

3.5. Reuse of the Beads for Successive Adsorption

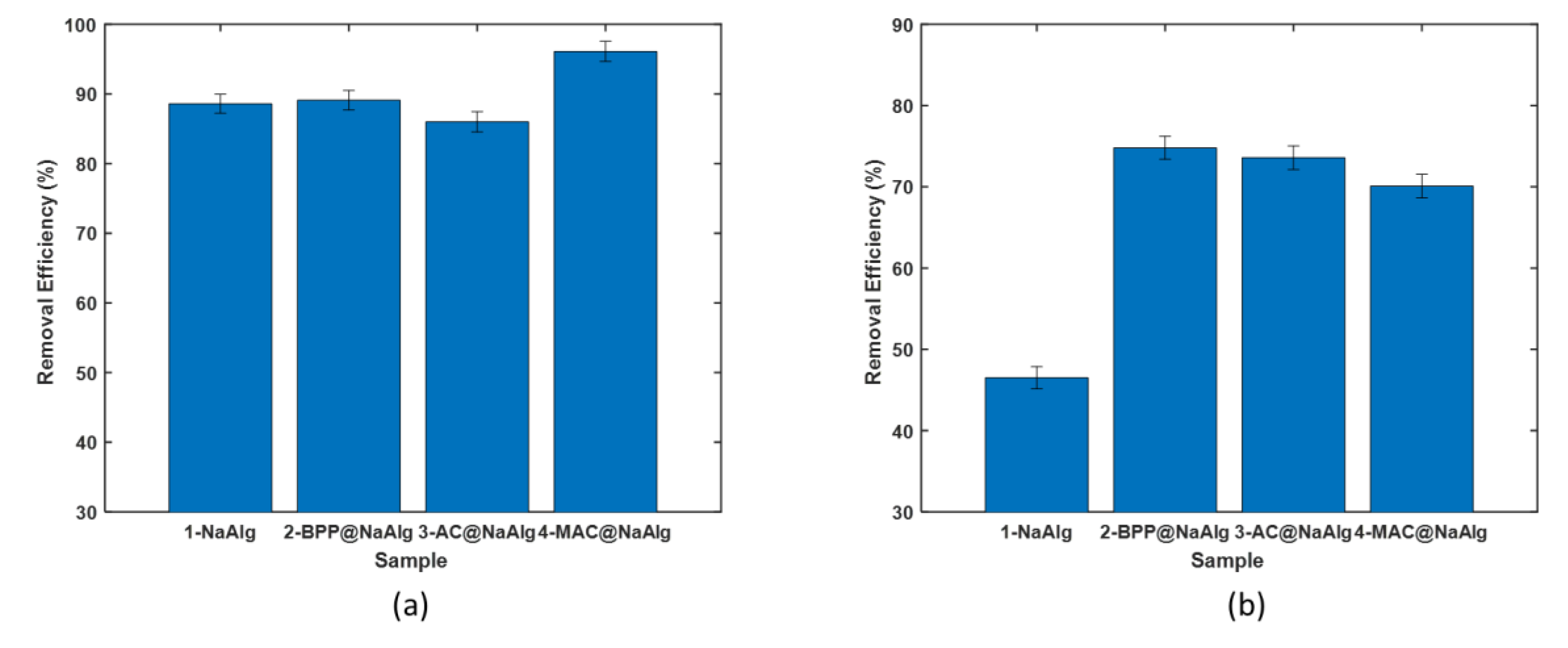

Figure 9 presents the results of the second cycle adsorption studies conducted with various pollutants. As observed in

Figure 9(a), the removal efficiency of tetracycline (TC) by the beads ranged from approximately 88% to 96%. This represents a marginal enhancement compared to the performance of the virgin beads. A similar slight improvement was also noted in the capacity of the MAC@NaAlg.

Figure 9 (b) shows removal Cr(VI) efficiencies of the beads that have been previously used in tetracycline adsorption. The results show that the beads still had reasonable removal efficiency ranging to 46 to 75% which. However, these values were lower than those obtained in the adsorption experiments with virgin beads. Despite the beads demonstrating a remarkable capacity, one might have anticipated a decrease in their removal efficiency. This expectation is based on the assumption that the first adsorption cycle would have occupied some of the active sites and functional groups with Chromium (VI). However, the results contradict this assumption.

A plausible explanation for these findings could be that the functional groups involved in the removal of TC differ from those required for the removal of Chromium (VI). Consequently, there is no competition for active sites. Interestingly, the presence of chromium appears to enhance the removal of TC. Different pollutants might interact with different functional groups. For example, the functional groups that interact with TC might be different from those that interact with Chromium (VI). This could explain why the removal efficiency of the beads did not decrease after the first adsorption cycle: the functional groups that were occupied by Chromium (VI) in the first cycle might not be the same ones needed for the removal of TC in the second cycle.

Furthermore, the presence of chromium might have changed the chemical environment of the beads, possibly making other functional groups more accessible or effective for the removal of TC. This could be the reason why the presence of chromium seemed to enhance the removal of TC. The FTIR analysis results revealed that the adsorbent beads had the following functional groups; hydroxyl groups, carbonyl, -C-O and the C-H groups. The activated carbons can also contain the benzene ring. All these groups are known to interact with tetracycline molecules [

20,

21,

22,

23]. For example, the hydroxyl can interact with tetracycline through ionic exchange; the -NH

2 group in the tetracycline can form π – π interaction and a cation – π bond with the benzene ring in the samples [

20].

3.6. Comparison of Adsorption with Other Materials

Tetracycline (TC) removal from water through adsorption has been studied using various adsorbents. Graphene oxide demonstrated high adsorption capacity (313 mg/g) and rapid kinetics, with adsorption decreasing at higher pH and Na

+ concentrations [

33]. Water treatment residues achieved 91.5% removal efficiency under optimized conditions, with adsorption capacity of 37.194 μmol TC/g[

34]. Struvite showed pH-dependent adsorption, with lowest removal (8.4%) at pH 7.7, and approximately 22% removal during precipitation[

35]. Magnetic nanocomposites exhibited excellent performance, reaching 99.8% removal efficiency at optimal pH 4.5-5.6 [

36].

The removal capacities of the adsorbent beads produced in this work were compared with similar materials from literature in

Table 2.

Recent studies have explored various adsorbent materials for efficient Cr(VI) removal from water and soil. Magnetic alginate hybrid beads (Fe

3O

4@Alg-Ce) demonstrated enhanced sorption capacity of 14.29 mg/g compared to calcium alginate and Fe

3O

4 particles alone [

37]. Chitosan beads modified with sodium dodecyl sulfate showed a maximum adsorption capacity of 3.23 mg/g for Cr(VI) [

38]. Polyvinyl alcohol-alginate beads crosslinked with boric acid and calcium chloride exhibited complete Cr(VI) removal after 1.5 hours under UV light illumination[

39]. A millimeter-sized polyaniline/polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate composite (PPS) demonstrated high adsorption capacity (83.1 mg/g) for Cr(VI) in water and effectively removed 24.17% of total Cr and 52.47% of Cr(VI) from contaminated soil after 30 days [

40]. These studies highlight the potential of various adsorbent materials for Cr(VI) remediation in both aqueous and soil environments.

The results from this research show that the banana peel powder based adsrobent beads produced in this work have great protential as adsorbent material for emerging pollutents suchs as anitbiotics and have materials. Its also been shown that beads still retain reasonale adsorption capacity after the first cycle even without desorbing the first pollutant.

Table 4.

Comparison of chromium (VI) removal capacity of adsorbents beads with other polymeric materials from literature.

Table 4.

Comparison of chromium (VI) removal capacity of adsorbents beads with other polymeric materials from literature.

| Material |

Removal Capacity (mg/g) |

Ref. |

| Fe3O4@Alg-Ce |

14.29 |

[37] |

| Chitosan beads |

3.23 |

[38] |

| Polyvinyl alcohol-alginate beads |

0.17 |

[39] |

| sodium alginate composite (PPS) |

83.1 |

[40] |

| PBP@NaAlg |

47.3 |

This study |

| AC@NaAlg |

46.6 |

This study |

| MAC@ NaAlg |

42.2 |

This study |

| NaAlg` |

41.2 |

This study |

4. Conclusions

The results show that banana peel waste, an abundant and low-cost resource, can be effectively transformed into advanced adsorbent materials, aligning with circular economy principles and promoting waste valorization. The study demonstrates that these adsorbent beads, particularly those containing magnetic activated carbon (MAC), are highly efficient in removing pollutants such as tetracycline (up to 92%) and hexavalent chromium (up to 79%) from aqueous solutions. The characterization of the beads highlights their suitability for adsorption, with functional groups, thermal stability, and surface area contributing to their high performance. Additionally, the beads retain significant adsorption capacity across reuse cycles without requiring the desorption of previously adsorbed pollutants, suggesting that the active sites for different pollutants, such as antibiotics and heavy metals, are distinct and non-competitive.

The research underscores the comparative advantage of banana peel-based beads over many other adsorbents reported in the literature, offering a cost-effective, sustainable, and environmentally friendly solution for wastewater treatment. Furthermore, these adsorbents show potential for broader applications, given their versatile adsorption capabilities. The study highlights the need for further research to optimize and scale up these materials for real-world applications, making them a promising innovation for addressing water pollution while utilizing waste materials effectively.

References

- Ahmed, M.B. , et al., Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from water and wastewater: Progress and challenges. Science of The Total Environment, 2015. 532: p. 112-126.

- Battak, N. , et al., Antibiotics usage in plant agriculture and its removal from wastewater using adsorption process: A short review. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2022. 2610(1).

- Sen, U. , et al., Removal of Antibiotics by Biochars: A Critical Review. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(21): p. 11963.

- Ahmad, T. and M. Danish, Prospects of banana waste utilization in wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 2018. 206: p. 330-348.

- Nguyen, V.-T. , et al., Preliminary study of doxycycline adsorption from aqueous solution on alkaline modified biochar derived from banana peel. Environmental Engineering Research, 2024. 29(3): p. 230196-0.

- Azzam, A.B. , et al., Heterogeneous porous biochar-supported nano NiFe2O4 for efficient removal of hazardous antibiotic from pharmaceutical wastewater. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023. 30(56): p. 119473-119490.

- Akpomie, K.G. and J. Conradie, Banana peel as a biosorbent for the decontamination of water pollutants. A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2020. 18(4): p. 1085-1112.

- Negroiu, M. , et al., Novel Adsorbent Based on Banana Peel Waste for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Synthetic Solutions. Materials, 2021. 14(14): p. 3946.

- Huang, Z., R. Campbell, and C. Mangwandi, Kinetics and Thermodynamics Study on Removal of Cr(VI) from Aqueous Solutions Using Acid-Modified Banana Peel (ABP) Adsorbents. Molecules, 2024. 29(5): p. 990.

- Nadew, T.T. , et al., Synthesis of activated carbon from banana peels for dye removal of an aqueous solution in textile industries: optimization, kinetics, and isotherm aspects. Water Practice and Technology, 2023. 18(4): p. 947-966.

- Al-sareji, O.J. , et al., A Sustainable Banana Peel Activated Carbon for Removing Pharmaceutical Pollutants from Different Waters: Production, Characterization, and Application. 2024. 17(5): p. 1032.

- Azzam, A.B. , et al., Construction of porous biochar decorated with NiS for the removal of ciprofloxacin antibiotic from pharmaceutical wastewaters. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2022. 49: p. 103006.

- Vo, T.D.H., V. T. Nguyen, and T.H. Nguyen, Removal of doxycycline antibiotics in water with adsorbents derived from banana peels. Science & Technology Development Journal: Science of the Earth & Environment, 2023. 7(2): p. 728-740.

- Ajala, O.A. , et al., Adsorptive removal of antibiotic pollutants from wastewater using biomass/biochar-based adsorbents. RSC Advances, 2023. 13(7): p. 4678-4712.

- Lam, S.S. , et al., Pyrolysis production of fruit peel biochar for potential use in treatment of palm oil mill effluent. Journal of Environmental Management, 2018. 213: p. 400-408.

- Rengga, W.D.P. , et al., Kinetic Study of Adsorption Carboxylic Acids of Used Cooking Oil Using Mesoporous Active Carbon.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021. 700(1).

- Malakar, B., D. Das, and K. Mohanty, Evaluation of banana peel hydrolysate as alternate and cheaper growth medium for growth of microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2024. 14(9): p. 10361-10371.

- Szcześniak, L., A. Rachocki, and J. Tritt-Goc, Glass transition temperature and thermal decomposition of cellulose powder. Cellulose, 2008. 15(3): p. 445-451.

- Börcsök, Z. and Z. Pásztory, The role of lignin in wood working processes using elevated temperatures: an abbreviated literature survey. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 2021. 79(3): p. 511-526.

- Cai, Y. , et al., Adsorption and Desorption Performance and Mechanism of Tetracycline Hydrochloride by Activated Carbon-Based Adsorbents Derived from Sugar Cane Bagasse Activated with ZnCl2. Molecules, 2019. 24(24): p. 4534.

- Long, J. , et al., Preparation of Oily Sludge-Derived Activated Carbon and Its Adsorption Performance for Tetracycline Hydrochloride. Molecules, 2024. 29(4): p. 769.

- Sağlam, S., F. N. Türk, and H. Arslanoğlu, Tetracycline (TC) removal from wastewater with activated carbon (AC) obtained from waste grape marc: activated carbon characterization and adsorption mechanism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2024. 31(23): p. 33904-33923.

- Vedenyapina, M.D. , et al., Activated Carbon as Sorbents for Treatment of Pharmaceutical Wastewater (Review). Solid Fuel Chemistry, 2019. 53(6): p. 382-394.

- Bhatnagar, A. and M. Sillanpää, Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—A review. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2010. 157(2): p. 277-296.

- Chen, S. , et al., Removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution using modified corn stalks: Characteristic, equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2011. 168(2): p. 909-917.

- Wu, J. , et al., Upcycling tea waste particles into magnetic adsorbent materials for removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions. Particuology, 2023. 80: p. 115-126.

- Mangwandi, C., H. Chen, and J. Wu, Production and optimisation of adsorbent materials from teawaste for heavy metal removal from aqueous solution: feasibility of hexavalent chromium removal – kinetics, thermodynamics and isotherm study. Water Practice and Technology, 2022. 17(9).

- Rai, M.K. , et al., Removal of hexavalent chromium Cr (VI) using activated carbon prepared from mango kernel activated with H3PO4. Resource-Efficient Technologies, 2016. 2: p. S63-S70.

- Duan, J. , et al., Enhanced adsorption of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions by CTAB-modified schwertmannite: Adsorption performance and mechanism. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 2024. 208: p. 464-474.

- Wang, J. and S. Wang, Removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from wastewater: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 2016. 182: p. 620-640.

- Tran, H.N., S. -J. You, and H.-P. Chao, Effect of pyrolysis temperatures and times on the adsorption of cadmium onto orange peel derived biochar. Waste Management & Research, 2016. 34(2): p. 129-138.

- Yu, F. , et al., Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from aqueous solution using carbon materials. Chemosphere, 2016. 153: p. 365-385.

- Gao, Y. , et al., Adsorption and removal of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solution by graphene oxide. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2012. 368(1): p. 540-546.

- Barbooti, M.M. and S. H. Zahraw. REMOVAL OF TETRACYCLINE FROM WATER BY ADSORPTION ON WATER TREATMENT RESIDUES. 2020.

- Başakçılardan-Kabakcı, S. , et al., Adsorption and Precipitation of Tetracycline with Struvite. Water Environment Research, 2007. 79(13): p. 2551-2556.

- Goyal, S. and R. Auchat, ADSORPTIVE REMOVAL OF TETRACYCLINE ANTIBIOTIC FROM AQUEOUS SOLUTION USING MAGNETIC NANOCOMPOSITES AS ADSORBENT. Journal of Advenced Scientific Research, 2022. 13(2).

- Gopalakannan, V. and N. Viswanathan, Synthesis of magnetic alginate hybrid beads for efficient chromium (VI) removal. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2015. 72: p. 862-867.

- Du, X. , et al., Removal of Chromium(VI) by Chitosan Beads Modified with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS). Applied Sciences, 2020. 10(14): p. 4745.

- Lee Te Chuan, et al., Polyvinyl Alcohol-Alginate Adsorbent Beads for Chromium (VI) Removal. international Journal of Engineering & Technology, 2018. 7 (20).

- Li, Y. , et al., Removal of Cr(VI) by polyaniline embedded polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate beads − Extension from water treatment to soil remediation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022. 426: p. 127809.

- Abed, M.F. and A.A.H. Faisal, Calcium/iron-layered double hydroxides-sodium alginate for removal of tetracycline antibiotic from aqueous solution. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2023. 63: p. 127-142.

- Ranjbari, S. , et al., Efficient tetracycline adsorptive removal using tricaprylmethylammonium chloride conjugated chitosan hydrogel beads: Mechanism, kinetic, isotherms and thermodynamic study. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020. 155: p. 421-429.

- Jaiyeola, O.O., H. Annath, and C. Mangwandi, Synthesis and evaluation of a new CeO2@starch nanocomposite particles for efficient removal of toxic Cr(VI) ions. Energy Nexus, 2023. 12: p. 100244.

- Göçenoğlu Sarıkaya, A. and B. Osman, Tetracycline adsorption via dye-attached polymeric microbeads. Cumhuriyet Science Journal, 2021. 42(3): p. 638-648.

- Liao, Q. , et al., Strong adsorption properties and mechanism of action with regard to tetracycline adsorption of double-network polyvinyl alcohol-copper alginate gel beads. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022. 422: p. 126863.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).