Submitted:

10 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

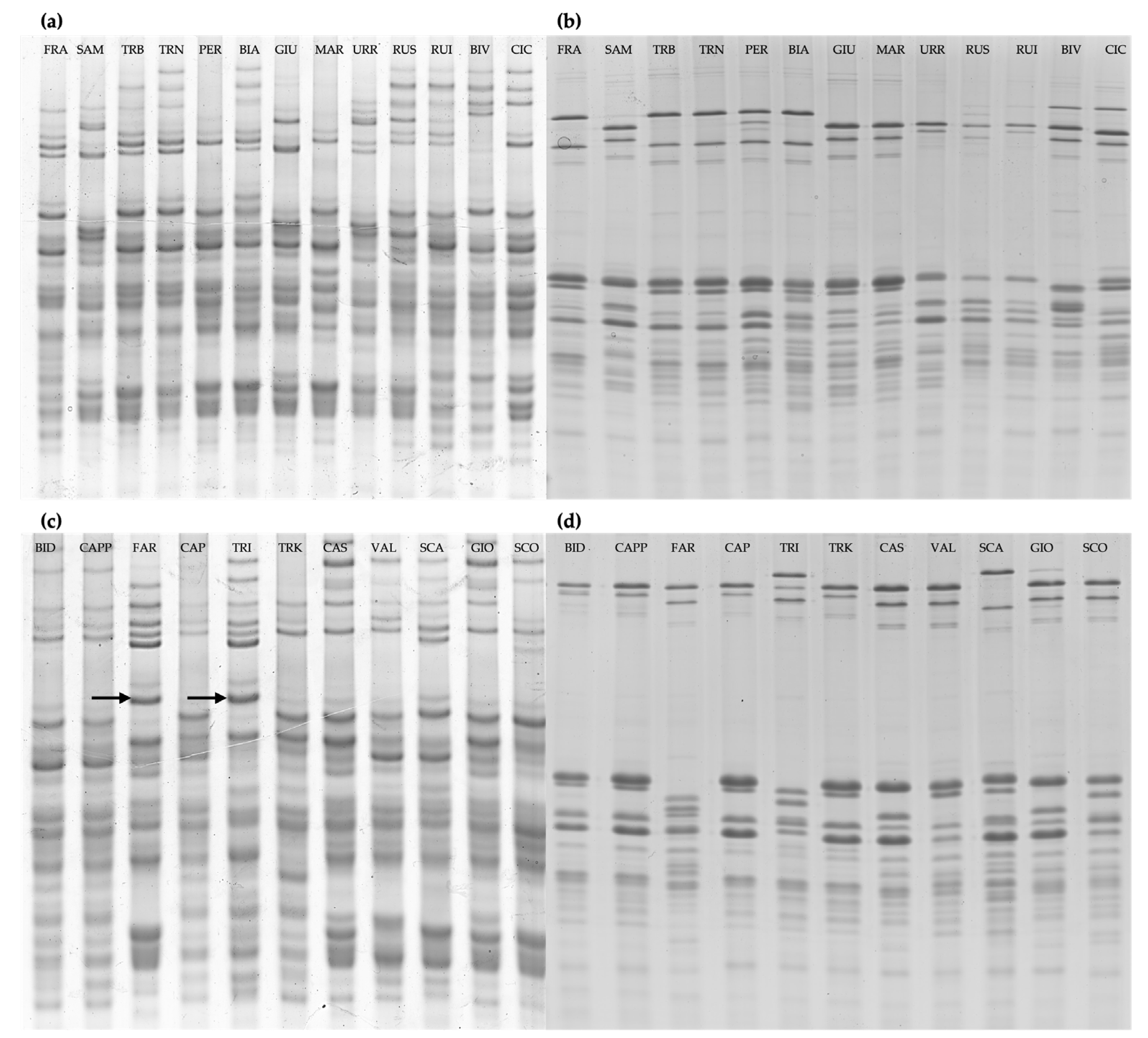

2.1. Analysis of Gluten Protein

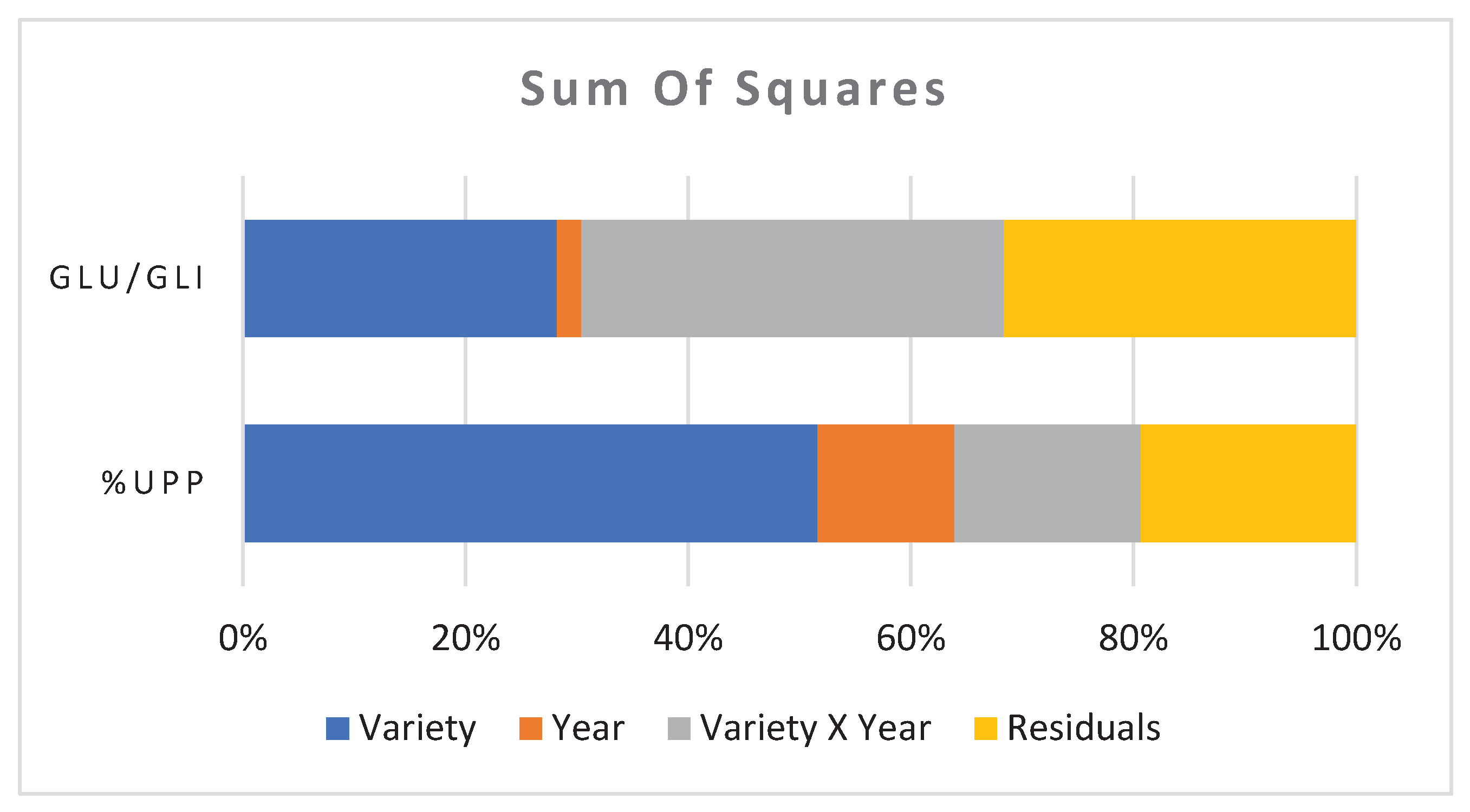

2.2. Measurement of the Polymeric Glutenin

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Experimental Conditions

4.2. Extraction of Gluten Protein

4.3. Electrophoretic Separation

4.4. Analysis Of Unextractable Polymeric Proteins (%UPP) by SE-HPLC

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shewry, P. R. Wheat. J. Exp. Bot 2009, 60, 1537–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTAT, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Available online: http://dati.istat.it//Index.aspx?QueryId=64761. (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Xynias, I. N.; Mylonas, I.; Korpetis, E. G.; Ninou, E.; Tsaballa, A.; Avdikos, I. D.; Mavromatis, A. G. Durum wheat breeding in the Mediterranean region: Current status and future prospects. Agronomy 2020, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicignano, A.; Di Monaco, R.; Masi, P.; Cavella, S. From raw material to dish: Pasta quality step by step. J. Sci. Food Agric 2015, 95, 2579–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vita, P.; Nicosia, O. L. D.; Nigro, F.; Platani, C.; Riefolo, C.; Di Fonzo, N.; Cattivelli, L. Breeding progress in morpho-physiological, agronomical and qualitative traits of durum wheat cultivars released in Italy during the 20th century. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malalgoda, M.; Ohm, J. B.; Manthey, F. A.; Elias, E. M.; Simsek, S. Quality characteristics and protein composition of durum wheat cultivars released in the last 50 years. Cereal Chem. 2019, 96, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, C; Dreisigacker, S.; Ammar, K.; Villegas, D. Agronomic performance of durum wheat landraces and modern cultivars and its association with genotypic variation in vernalization response (Vrn-1) and photoperiod sensitivity (Ppd-1) genes. Eur. J. Agron 2020, 120, 126129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco, M. L.; Siracusa, L.; Dattilo, S.; Venora, G.; Ruberto, G. Phenolic Fingerprint of Sicilian Modern Cultivars and Durum Wheat Landraces: A Tool to Assess Biodiversity. Cereal Chem 2017, 94, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Loreto, A.; Bosi, S.; Montero, L.; Bregola, V.; Marotti, I.; Sferrazza, R. E.; Dinelli, G.; Herrero, M.; Cifuentes, A. Determination of phenolic compounds in ancient and modern durum wheat genotypes. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menga, V.; Giovanniello, V.; Savino, M.; Gallo, A.; Colecchia, S.A.; De Simone, V.; Zingale, S.; Ficco, D.B.M. Comparative analysis of qualitative and bioactive compounds of whole and refined flours in durum wheat grains with different year of release and yield potential. Plants 2023, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficco, D. B. M.; Riefolo, C.; Nicastro, G.; De Simone, V.; Di Gesù, A. M.; Beleggia, R.; Platani, C.; Cattivelli, L.; De Vita, P. Phytate and mineral elements concentration in a collection of Italian durum wheat cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2009, 111, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficco, D. B M.; Prandi, B.; Amaretti, A.; Anfelli, I.; Leonardi, A.; Raimondi, S.; Pecchioni, N.; De Vita, P.; Faccini, A.; Sforza, S.; Rossi, M. Comparison of gluten peptides and potential prebiotic carbohydrates in old and modern Triticum turgidum ssp. genotypes. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 568–576. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry, P. R.; Hey, S. Do “ancient” wheat species differ from modern bread wheat in their contents of bioactive components? J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 65, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.U.; Steiner, D.; Longin, C.F.H.; Würschum, T.; Schweiggert, R.; Carle, R. Wheat and the irritable bowel syndrome – FODMAP levels of modern and ancient species and their retention during bread baking. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Whittaker, A.; Pagliai, G.; Benedettelli, S.; Sofi, F. Ancient wheat species and human health: Biochemical and clinical implications. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry, P. R. Do ancient types of wheat have health benefits compared with modern bread wheat? J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 79, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombieri, S.; Bonarrigo, M.; Cammerata, A.; Quagliata, G.; Astolfi, S.; Lafiandra, D.; Sestili, F.; Masci, S. Characterization of Triticum turgidum sspp. durum, turanicum, and polonicum grown in Central Italy in relation to technological and nutritional aspects. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1269212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P. R.; Hassall, K. L.; Grausgruber, H.; Andersson, A. M.; Lampi, A. M.; Piironen, V.; Rakszegi, M.; Ward, J.L; Lovegrove, A. Do modern types of wheat have lower quality for human health? Nutr. Bull. 2020, 45, 362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pecetti, L.; Boggini, G.; Gorham, J. Performance of durum wheat landraces in a Mediterranean environment (eastern Sicily). Euphytica 1994, 80, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; El-Basyoni, I.; Baenziger, P.S.; Singh, S.; Royo, C.; Ozbek, K.; Aktas, H.; Ozer, E.; Ozdemir, F.; Manickavelu, A.; Ban, T.; Vikram, P. Exploiting genetic diversity from landraces in wheat breeding for adaptation to climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3477–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruisi, P.; Frangipane, B.; Amato, G.; Frenda, AS.; Plaia, A.; Giambalvo, D.; Saia, S. Nitrogen uptake and nitrogen fertilizer recovery in old and modern wheat genotypes grown in the presence or absence of interspecific competition. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Schulthess, A.W.; Bassi, F.M.; Badaeva, E.D.; Neumann, K.; Graner, A.; Özkan, H.; Werner, P.; Knüpffer, H.; Kilian, B. Introducing beneficial alleles from plant genetic resources into the wheat germplasm. Biology 2021, 10, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazco, R., Villegas, D., Ammar, K., Peña, R. J., Moragues, M., & Royo, C. (2012). Can Mediterranean durum wheat landraces contribute to improved grain quality attributes in modern cultivars? Euphytica, 185, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Pandino, G.; Restuccia, A.; Caruso, P.; Lombardo, S.; Mauromicale, G. Allelopathy in Durum Wheat Landraces as Affected by Genotype and Plant Part. Plants 2022, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.C.; Mercati, F.; Spina, A.; Blangiforti, S.; Venora, G.; Dell’Acqua, M.; Lupini, A.; Preiti, G.; Monti, M.; Pè, M.E.; Sunseri, F. High-Throughput Genotype, Morphology, and Quality Traits Evaluation for the Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Wheat Landraces from Sicily. Plants 2019, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.C.; Blangiforti, S.; Preiti, G.; Spina, A.; Bosi, S.; Marotti, I.; Mauceri, A.; Puccio, G.; Sunseri, F.; Mercati, F. Elucidating the Genetic Relationships on the Original Old Sicilian Triticum Spp. Collection by SNP Genotyping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, F.; Di Serio, E.; Miazzi, M. M.; Pavan, S.; Saia, S.; De Vita, P.; D’Agostino, N. Intra-and Inter-Population Genetic Diversity of “Russello” and “Timilia” Landraces from Sicily: A Proxy towards the Identification of Favorable Alleles in Durum Wheat." Agronomy 2022, 12, 1326.

- Laidò, G.; Mangini, G.; Taranto, F.; Gadaleta, A.; Blanco, A.; Cattivelli, L.; Marone, D.; Mastrangelo, A.M; Papa, R.; De Vita, P. Genetic diversity and population structure of tetraploid wheats (Triticum turgidum L.) estimated by SSR, DArT and pedigree data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahri, A.; Chentoufi, L.; Arbaoui, M.; Ardisson, M.; Belqadi, L.; Birouk, A.; Roumet, P.; Muller, M.H. Towards a comprehensive characterization of durum wheat landraces in Moroccan traditional agrosystems: Analysing genetic diversity in the light of geography, farmers’ taxonomy and tetraploid wheat domestication history. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moragues, M.; Moralejo, M.; Sorrells, M.E.; Royo, C. Dispersal of durum wheat [Triticum turgidum L. ssp. turgidum convar.durum (Desf.) MacKey] landraces across the Mediterranean basin assessed by AFLPs and microsatellites. Genet. Resour. CropEvol. 2007, 54, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliuolo, G.; Mazzeo, M.; Greco, I. Temporal variation of diversity in Italian durum wheat germplasm. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007, 54, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Giraldo, P.; Royo, C.; Villegas, D.; Aranzana, M.J.; Carrillo, J.M. Diversity and Genetic Structure of a Collection of Spanish Durum Wheat Landraces. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 2262–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, M.; Sanguineti, M.C.; Donini, P.; Tuberosa, R. Microsatellite analysis reveals a progressive widening of the genetic basis in the elite durum wheat germplasm. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 107, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, A.; Anastasi, U.; Bizzini, M.; Montemagno, S.; Nicotra, C.; Blangiforti, S.; Spina, A.; Cosentino, S.L.; Lo Piero, A.R. Genetic and Morpho-Agronomic Characterization of Sicilian Tetraploid Wheat Germplasm. Plants 2022, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.A.; Giuliani, M.M.; Giuzio, L.; De Vita, P.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.R.; Flagella, Z. Differences in gluten protein composition between old and modern durum wheat genotypes in relation to 20th century breeding in Italy. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 87, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Saletti, R.; Cunsolo, V.; Svensson, B.; Muccilli, V.; De Vita, P.; Foti, S. Dataset of the metabolic and CM-like protein fractions in old and modern wheat Italian genotypes. Data Brief 2019, 27, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Saletti, R.; Cunsolo, V.; Svensson, B.; Muccilli, V.; De Vita, P.; Foti, S. Qualitative proteomic comparison of metabolic and CM-like protein fractions in old and modern wheat Italian genotypes by a shotgun approach. J. Proteom. 2020, 211, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Saletti, R.; Cunsolo, V.; Svensson, B.; Muccilli, V.; De Vita, P.; Foti, S. Quantitative label-free comparison of the metabolic protein fraction in old and modern italian wheat genotypes by a shotgun approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo, A.; Messina, B.; Russo, G. Evaluation of Glycemic Index of Six Different Samples of Commercial and Experimental Pasta Differing in Wheat Varieties and Production Processes. Foods 2021, 10, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blangiforti, S.; Gallo, G.; Porfiri, O. Morpho-agronomic and molecular assessment of a collection of Sicilian wheats [Triticum aestivum L.; Triticum durum Desf.]. Italus Hortus 2006, 13, 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts, I.; Lagrain, B.; Brunnbauer, M.; Delcour, J. A.; Koehler, P. Improved identification of wheat gluten proteins through alkylation of cysteine residues and peptide-based mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P. R.; Halford, N. G.; Lafiandra, D. Genetics of wheat gluten proteins. Adv. Genet. 2003, 49, 111–184. [Google Scholar]

- Shewry, P. R.; Halford, N. G.; Tatham, A. S.; Popineau, Y.; Lafiandra, D.; Belton, P. S. The high molecular weight subunits of wheat glutenin and their role in determining wheat processing properties. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2003, 45:219-302. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, H. Chemistry of gluten proteins. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, C. W.; Békés, F.; Bushuk, W. Gluten: A balance of gliadin and glutenin. Gliadin and glutenin: The unique balance of wheat quality 2006, 3-32.

- Shewry, P. R.; Lafiandra, D. Wheat glutenin polymers 1. structure, assembly and properties. J. Cereal Sci 2022, 103486.

- Lafiandra, D.; Shewry, P. R. Wheat Glutenin polymers 2, the role of wheat glutenin subunits in polymer formation and dough quality. J. Cereal Sci 2022, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woychik, J. H.; Boundy, J. A.; Dimler, R. J. Starch gel electrophoresis of wheat gluten proteins with concentrated urea. Arch Biochem Biophys 1961, 94, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarda, D.D; Adalsteins, A.E; Laird, N.F. Gamma-gliadins with alpha-type structure coded on chromosome 6B of the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar "Chinese Spring". In: Lasztity R and Bekes F (eds) Proc 3rd Int Workshop on Gluten Proteins 1993, Budapest, Hungary, pp. 20–29.

- Ruiz, M.; Giraldo, P. The influence of allelic variability of prolamins on gluten quality in durum wheat: An overview. J. Cereal Sci. 101 (2021): 103304.

- Carrillo J.M., Vazquez, J.F. Orellana J. Relationship Between Gluten Strength and Glutenin Proteins in Durum Wheat Cultivars Plant Breeding 104, 325-333 (1990)J.

- D’Ovidio, R.; Masci, S. The low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits of wheat gluten. J. Cereal Sci. 2004, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, G.; Giannelli, G.; Agrimonti, C.; Spina, A.; Pasini, G. Traceability of Sicilian durum wheat landraces and historical varieties by high molecular weight glutenins footprint. Agronomy 2021, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, P.I.; Holt, L.M.; Lawrence, G.J.; Law, C.N. The genetics of gliadin and glutenin, the major storage proteins in the wheat endosperm. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 1982, 31, 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Metakovsky, E. V. Wheat storage proteins: Genes, inheritance, variability, mutations, phylogeny, seed production, flour quality. Lambert Acad. Pabl. 2015 (in Russian, English summary).

- Metakovsky, E.; Melnik, V.; Rodriguez-Quijano, M.; Upelniek, V.; Carrillo, J. M. A catalog of gliadin alleles: Polymorphism of 20th-century common wheat germplasm. Crop J. 2018, 6, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogna, N.E.; Peruffo, A.D.B.; Boggini, G.; Corbellini, M. Analysis of wheat varieties by gliadin electrophoregrams. II. Nature, origin and quality of biotypes present in six Italian common wheat varieties. Genetica Agraria, 1982 36:143-154.

- Lawrence, G.J.; Moss, H.J.; Shepherd, K.W.; Wrigley, C.W. Dough quality of biotypes of eleven Australian wheat cultivars that differ in high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit composition. J. Cereal Sci. 1987, 6, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag-Strohm, T.; Payne, P.I.; Salovaara, H. Effect of allelic variation of glutenin subunits and gliadins on baking quality in the progeny of two biotypes of bread wheat cv. Ulla. J. Cereal Sci. 1996, 24, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metakovsky, E. V.; Branlard, G. P.; Graybosch, R. A. Gliadins of common wheat: Polymorphism and genetics. Gliadin and glutenin: The unique balance of wheat quality 2006, 35-84.

- De Cillis, U. I Frumenti Siciliani; Tipografia Zuccarello & Izzi: Catania, Italy, 1942; ISBN 88-7751-229-6. [Google Scholar]

- De Cillis, E. I Grani d’Italia. Roma: Tipografia della Camera dei Deputati, 1927173.

- Marzario, S.; Logozzo, G.; David, J. L.; Zeuli, P. S.; Gioia, T. Molecular Genotyping (SSR) and Agronomic Phenotyping for Utilization of Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Ex Situ Collection from Southern Italy: A Combined Approach Including Pedigreed Varieties. Genes 2018, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.B.; Popineau, Y.; Lefebvre, J.; Cornec, M.; Lawrence, G.J.; MacRitchie, F. Biochemical basis of flour properties in bread wheats. II. Changes in polymeric protein formation and dough/gluten properties associated with the loss of low Mr or high Mr glutenin subunits. J. Cereal Sci. 1995, 21, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagati, V.D.; Sestili, F.; Lafiandra, D.; D’Ovidio, R.; Rogniaux, H.; Masci, S. Characterization of durum wheat high molecular weight glutenin subunits Bx20 and By20 sequences by a molecular and proteomic approach. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 51, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibba, M. I.; Kiszonas, A. M.; Guzmán, C.; Morris, C. F. Definition of the low molecular weight glutenin subunit gene family members in a set of standard bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties . J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 74, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.; Carucci, F.; Masci, S.; Flagella, Z.; Gatta, G.; Giuliani, M.M. Effects of genotype, growing season and nitrogen level on gluten protein assembly of durum wheat grown under Mediterranean conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2022, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

| ID_CREA | Conservation Varieties | HMW-GS | LMW-GS Type | g-gliadins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FD-BIA-1 | Biancuccia | null,6+8 | 2 | 42 |

| FD-BID-1 | Bidì | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-BID-2 | Bidì | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-BID-3 | Bidì | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-BID-5 | Bidì | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-BIV-1 | Bivona | 2*,13+16 | 1 | 44 |

| FD-CAP-1 | Capeiti 8 | null,20+20 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-CAS-2 | Castiglione Glabro | null,13+16 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-CAS-3 | Castiglione Glabro | null,13+16 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-CIC-1 | Ciciredda | 2*,32+33 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-FAR-1 | Faricello | null,13+16 | 1 | 42 |

| FD-FAR-2 | Faricello | null,13+16 | 1 | 42 |

| FD-FRA-1 | Francesa | null,6+8 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-GIO-1 | Gioia | null,6+8/13+16 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-GIO-2 | Gioia | null,13+16 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-GIU-1 | Giustalisa | null,13+16 | 2 | 47 |

| FD-MAR-1 | Martinella | null,13+16 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-1 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8/20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-2 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8/20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-3 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-4 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8/20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-6 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-7 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8/20+20 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-8 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-9 | Perciasacchi | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-PER-13 | Perciasacchi | null,6+8 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-RUI-1 | Ruscia | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-RUI-3 | Ruscia | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-RUI-4 | Ruscia | null,20x+20y | 2 | 45 |

| FD-RUS-1 | Russello | 2*,13+16/6+8 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-RUS-3 | Russello | 2*,13+16/6+8 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-RUS-4 | Russello | null,13+16/6+8 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-RUS-6 | Russello | null,13+16 | 1 | 45 |

| FD-SAM-1 | Sammartinara | null,13+16 | 2 | 47 |

| FD SCA-1 | Scavuzza | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-SCO-1 | Scorsonera | null,20 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-SCO-2 | Scorsonera | null,20 | 2 | 45 |

| FD-TRB-1 | Timilia R.B. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRB-2 | Timilia R.B. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRB-4 | Timilia R.B. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRI-1 | Tripolino | null,6+8/13+16 | 1 | 42 |

| FD-TRN-1 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-3 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-6 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-7 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-8 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-9 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-11 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-TRN-12 | Timilia R.N. | null,6+8 | 2 | 44 |

| FD-URR-1 | Urria | null,20x+20y | 2 | 47 |

| FD-VAL-2 | Vallelunga pubescente | null,13+16 | 2 | 45 |

| %UPP | Glu/Gli | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Bidì | Landrace | 33.9 ± 1.0 ab | 38.8 ± 2.6 bc | 0.480 ± 0.021 c | 0.734 ± 0.040 a* |

| Castiglione Glabro | Landrace | 29 ± 1.2 abc | 28.1 ± 0.3 de | 0.639 ± 0.042 ab* | 0.412 ± 0.026 d |

| Gioia | Landrace | 29.4 ± 1.1 abc | 31.2 ± 0.8 de | 0.465 ± 0.037 c | 0.556 ± 0.004 bcd |

| Perciasacchi | Landrace | 25.9 ± 1.7 c | 38.9 ± 3.0 c* | 0.586 ± 0.024 bc | 0.505 ± 0.031 cd |

| Russello | Landrace | 36.9 ± 1.2 a | 44.2 ± 2.0 b* | 0.622 ± 0.018 ab | 0.573 ± 0.029 bc |

| Ruscia | Landrace | 15.1 ± 0.5 d | 25.2 ± 1.3 e* | 0.560 ± 0.016 bc | 0.492 ± 0.056 cd |

| Saragolla | Modern Cultivar | 30.8 ± 3.4 abc | 50.7 ± 2.2 a* | 0.580 ± 0.031 bc | 0.664 ± 0.017 ab* |

| Senatore Cappelli | Old Cultivar | 28.3 ± 1.6 bc* | 22.4 ± 1.9 e | 0.723 ± 0.017 a* | 0.559 ± 0.014 bcd |

| Timilia Reste Bianche | Landrace | 30.1 ± 0.7 abc | 30.3 ± 1.0 de | 0.530 ± 0.022 bc* | 0.424 ± 0.021 d |

| Timilia Reste Nere | Landrace | 27.2 ± 1.4 bc | 33.5 ± 1.1 d* | 0.519 ± 0.031 bc* | 0.428 ± 0.018 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).