1. Introduction:

Physics is well known as one of the most vital branches of science that aims to make life easier. To achieve this goal new technologies were produced to that satisfy human needs. This is done by creating new technologies by changing the physical properties of matter. The wide spread of electronic devices and solar cells increased the importance of the optical and electrical properties of matter [

1]. The optical properties like transmission, reflection and absorption of material are important for electronic devices as well as the solar cells. Although the electronic and the solar technologies are important, but the latter is more important and urgent. This comes from the fact that energy is the spirit that operate all devices and, equipment and instruments. One of the most preferable energy sources is the solar energy. This comes from the fact that it is almost available everywhere beside the fact that it is almost pollution free. The most popular solar energy technology is the one that converted solar energy to electricity. This comes from the fact that electric energy can be converted easily to other useful energy forms. For fabricating solar cells and light sensors [

2], the optical and electric properties of matter are useful. These properties are even useful for other physical phenomena like super conductivity [

3], in which properties like conductivity and electric permittivity [

4] are used in fabricating magnetic trains, electrical and electronic devices. All these devices need energy to operate. Human needs to energy are recently increasing rapidly. Therefore, petroleum products are widely used to satisfy the human needs partially Scientists found that petroleum fuel causes severe biological hazards to people. This encourages researchers to try to improve the performance of the solar cells to be cheaper and more efficient [

5,

6]. The most commercially available one is the silicon solar cells. Unfortunately, silicon cells are expensive, having low efficiency with complex fabrication processes. This requires searching for new solar cells generations that are cheaper and more efficient. The so-called Nano solar cells are now widely paid attention of the scientists to replace silicon cells [

7,

8]. Different types of Nano cells are now fabricated, like polymer cells doped with dyes in addition to zinc and copper oxide cells [

9]. The physical properties of these new generations depend on the so-called Nano science [

10,

11]. Nano science is a new branch of physics that takes care of the behavior of Nano materials. Nano materials are in the form of isolated particles having dimensions ranging from 1 up to 300 Nano meters. One Nano meter is equal to one over 1000 million meters. The laws of quantum mechanics can describe the behavior of such Nano materials [

12,

13]. The physical properties of Nano matter are different from that of the bulk matter.

Most promising one, which has high stability and gives a wide variety of structures and optoelectronic properties are perovskite materials. Perovskite materials are one of the promising materials that can replace silicon solar cells. Perovskite are characterized by its facilitating energy storage, and optoelectronic light electric conversion properties due to its superior photoelectric and catalytic properties.

The first generation of Perovskite is calcium titanium oxide or calcium titanate, with the chemical formula CaTiO3. All materials with the crystal structure as ABX3 structure are considered as a perovskite, where A and B are cations. A is usually an alkaline or rare earth element, B transition metals, and X is, anion may be oxide or halogen. One has two perovskite types, inorganic perovskite, and organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite.

The change of the physical properties of the perovskite materials results from the range of different energy crystal structures and chemical composition due to incorporating different alkaline earth, rare earth, and transition metal ions. among Perovskite material the one based on iron oxides look more promising due to the iron abundance in addition to their large magnetic moment. This encourages fabricating perovskite solar cells based on iron oxides by changing other elements and their concentrations to know the factors that affect the efficiency of the solar cells.

Different attempts were made to fabricate and to study the performance of perovskite solar cells. One of them was done by Yanking Zhu [

14]. Recently, metal halide perovskite materials have attracted interest due to their ease fabrication processes and higher efficiency. Nowadays perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have high efficiency up to 25.7% and 31.3% for the perovskite-silicon tandem solar cells. Bilayer perovskite film composed of a thin low dimensional perovskite layer and a three-dimensional perovskite layer shows high efficiency and good stability conditions.

Anup Bist [

15] in his work exhibit innovative methods such as surface passivation by precursor solutions, doping and composites increase stability. It is shown that only few materials that are used in the fabrication of perovskite can make it commercially available.

In the paper published by Sonali Mehra etal [

16] he studied the behavior of halide perovskites, this work mainly focuses on synthesizing and evaluating the efficiency of methyl ammonium lead halide-based perovskite (MAPbX

3; X=Cl, Br, I) solar cells. Preparation technique is based on the colloidal Hot-injection method (HIM) to synthesize MAPbX

3 (X=Cl, Br, I) perovskites using the specific precursors and organic solvents under ambient conditions. The results obtained indicate that the particle size and morphology of perovskites vary with halide variation. The MAPbI

3 perovskite has a low band gap and low carrier lifetime but has the highest efficiency among other halide perovskite samples. The conversion efficiency of the MAPbX

3 perovskites has been evaluated through extensive device simulations. Here, the optical constants, band gap energy and carrier lifetime of MAPbX

3 were used for simulating three different perovskite solar cells, namely I, Cl or Br halide-based perovskite solar cells. MAPbI

3, MAPbBr

3 and MAPbCl

3 absorber layer-based devices showed efficiencies ~13.7 %, 6.9 % and 5.0 %.

The work done by Asma O. etal [

17] is concerned with the performance of convention perovskite cells. They focused on cubic single crystals. Experimental observations using x- ray photoelectron spectroscopy results indicated that Valence band maximum values consists of states contributed by Br and Pb which agrees with simulation results based on the density functional theory. In the work done by George G. Njema [

18], the deposition technique s, evaporation rate, type of solvents and temperature was shown to have significant effects on the degree of crystallization. This in turn affects the efficiency, which increases upon increasing the crystallization degree. The inorganic perovskite cells are found to be more efficient, with long stability lifetime and ease fabrication processes.

The research done by Saemi Takahashi [

19] studied the effects of TiO

2 interfacial morphology on perovskite solar cells by modifying micro and Nano surface roughness on the crystallinity of the perovskite layer. He found significant improvement of the crystal morphology. This increases the efficiency and reduced V-I hysterias.

Another useful work was done by Ningyu Ren etal, [

20] the performance of polycrystalline perovskite was improved when adding small amounts of Cadmium Acetate (CdAc

2) in the Pbl

2 precursor solution. This results in Nano - hole array films and promotes crystal orientation. This suppresses the non-radiative recombination and results in long carrier lifetime and efficiency of 22.78%. It was also found that the tandem solar cells which is un encapsulate maintain 109.78% of the initial efficiency after 300 hr. at 45 C in nitrogen atmosphere.

The research of Sekai Tombe, etal [

21] is concerned with the behavior of methylammonium (MA) lead halide derivatives MSPb

3-xYx (Cl, Br, I). The energy band width is dependent on the halide type (Cl, Br, I) and its concentration. The r

work done by Masha Moradbeigi [

22] aims to make perovskite cells commercially available. This is done by using simulation. In this work polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is used as a substrate. Plasma polymer fluorocarbon (PPFC) coating is suggested as anti-reflecting layer (ARL). The self-cleaning property was provided by PPFC. The results obtained indicated that four terminal tandem solar cells have high efficiency of 30.14%.

The work done by Nisar Ali, etal [

23] is concerned with the attempts made by different researchers to improve the performance of perovskite materials in addition to also improve the stability, validity, consistency, and reproducibility. These attempts studied the effects of solvent, interface, and structure engineering leading toward increasing efficiency to exceed 25.4%. The paper also investigates the device instability and its role in limiting the practical applications of the hybrid perovskite solar cell. This review provides a summary of the developments to resolve these issues with the uses of different synthesis routes and materials to obtain a stable ABX

3 type structure of the perovskite materials. This review also includes the effects of electron transport layer on hysteresis phenomenon and long-term stability. A comprehensive discussion on the crystal structure, energy level, absorption coefficient, degradation and chemical bonding in perovskite solar cell materials are also investigated.

2. Theoretical model based on the string theory:

The intensity I of the wave can be found in terms of the wave function and the imaginary part of the wave number to be

Consider small particle of mass m moving and vibrating with velocity v, and with force constant k in moving in a resistive medium having coefficient of friction

. Its equation of motion is given by.

One can solve this equation by suggesting the electrons as strings. Thus, the velocity v is given to be.

According to the relation of velocity with the acceleration a and displacement

, one gets.

Using Equations (5) and (6) in Equation (3) yields,

Multiplying both sides by

gives,

Rearranging and using the fact that.

gives

Hence

Therefore, the velocity can be written in a complex from

The current density J is found to be related to the velocity and the conductivity according to the relationship.

The momentum p is also related to the velocity and the wave number according to the relationship.

The wave number and the conductivity can be written in a complex from to be.

Thus, according to Equations (12), (14) and (15) the imaginary part of the wave number is given to be.

Equations (12), (13) and (15) give the real conductivity to be.

For very small mass m and for the high applied frequency compared to the natural frequency

Thus, the imaginary wave number in Equation (16) reduces to be.

While the conductivity in Equation (17) becomes

Taking the nano crystal size to be equal to the atomic radius assuming the proportionality constant to be equal one for simplicity, one gets

But the velocity is related to the frequency and the atomic radius and the crystal size according to the relationship.

Hence one gets the absorption coefficient and the transmission coefficient T to be.

Where the absorption coefficient takes the form

The coefficient of friction is related to the mass m and the relaxation time to be in the form.

The relaxation time can also be expressed in terms of the distance d and the velocity to be.

Thus, the conductivity is given to be.

One can relate the electrical force of the nucleus of the atom to the centrifugal force according to the relationship.

Thus, the velocity is given to be.

Thus, the refractive index takes the form.

Where,

Using the relationship

The magnetic permeability is also given by,

4. Results and Discussion:

The work done by Amira [

24] has been developed and used in this work to see how some optical and electrical properties of the thin films B

xFe

(1-x)TiO

4 can be linked and explained theoretically. According to empirical relation in

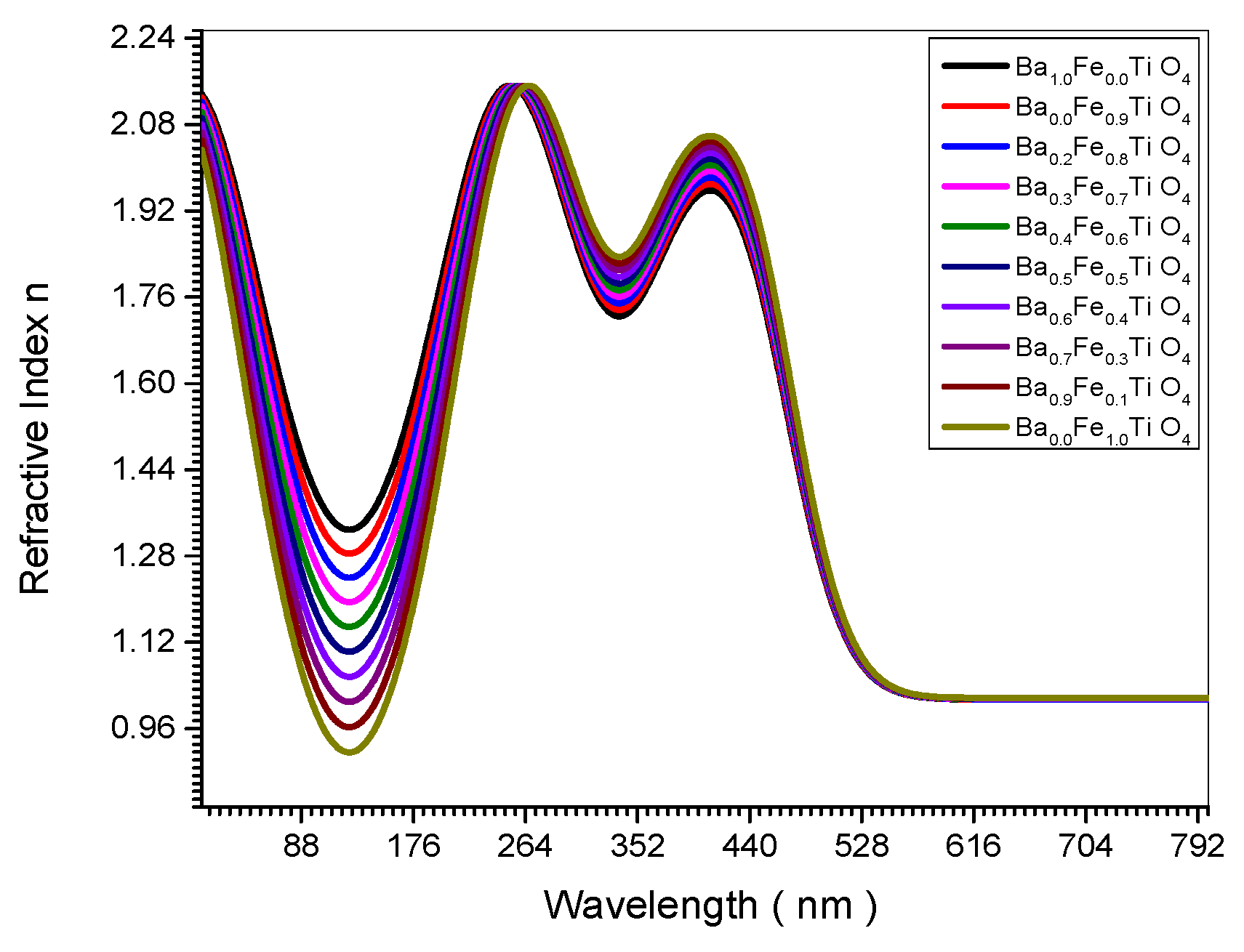

Figure 11 the refractive index increases upon increasing the crystal size.

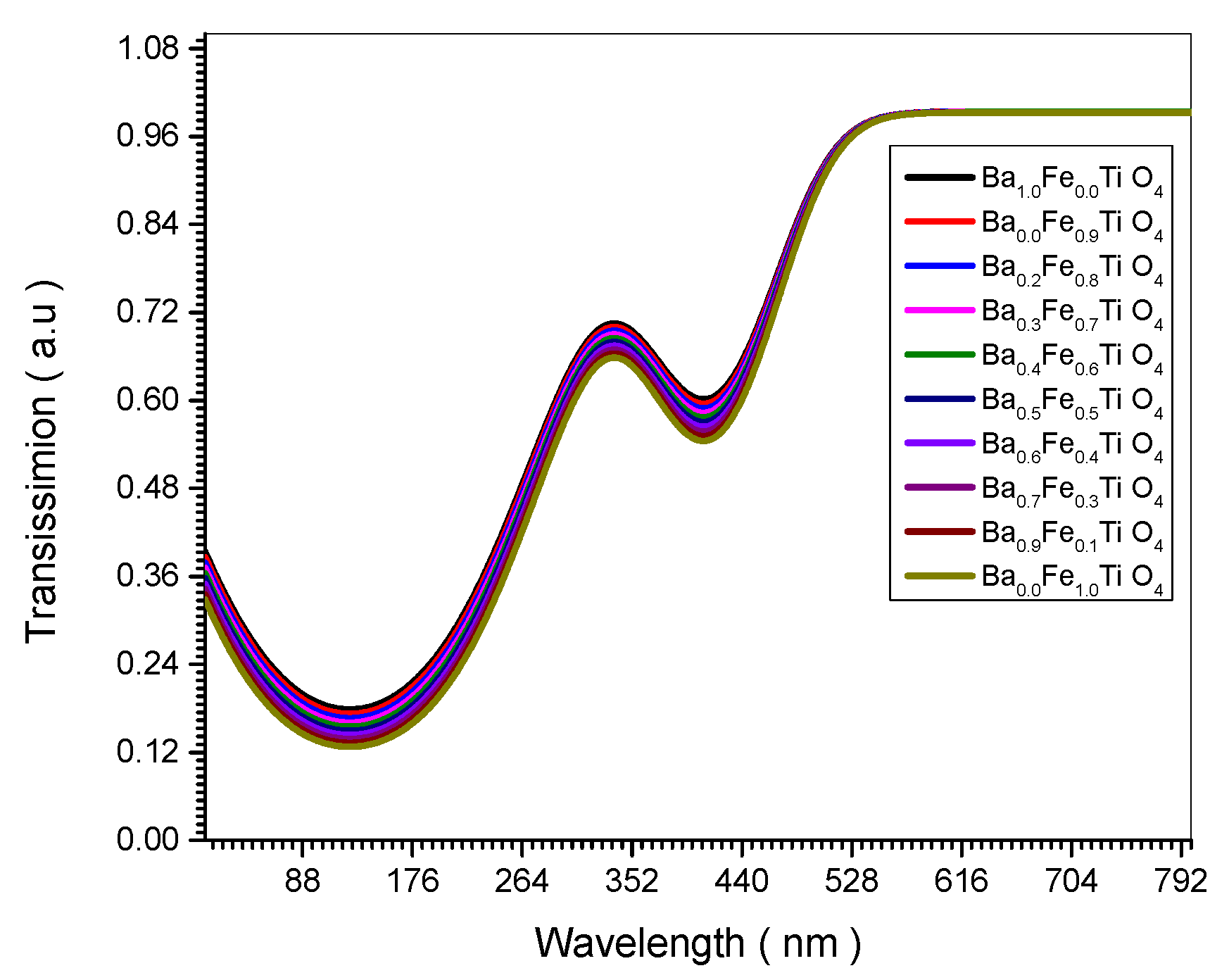

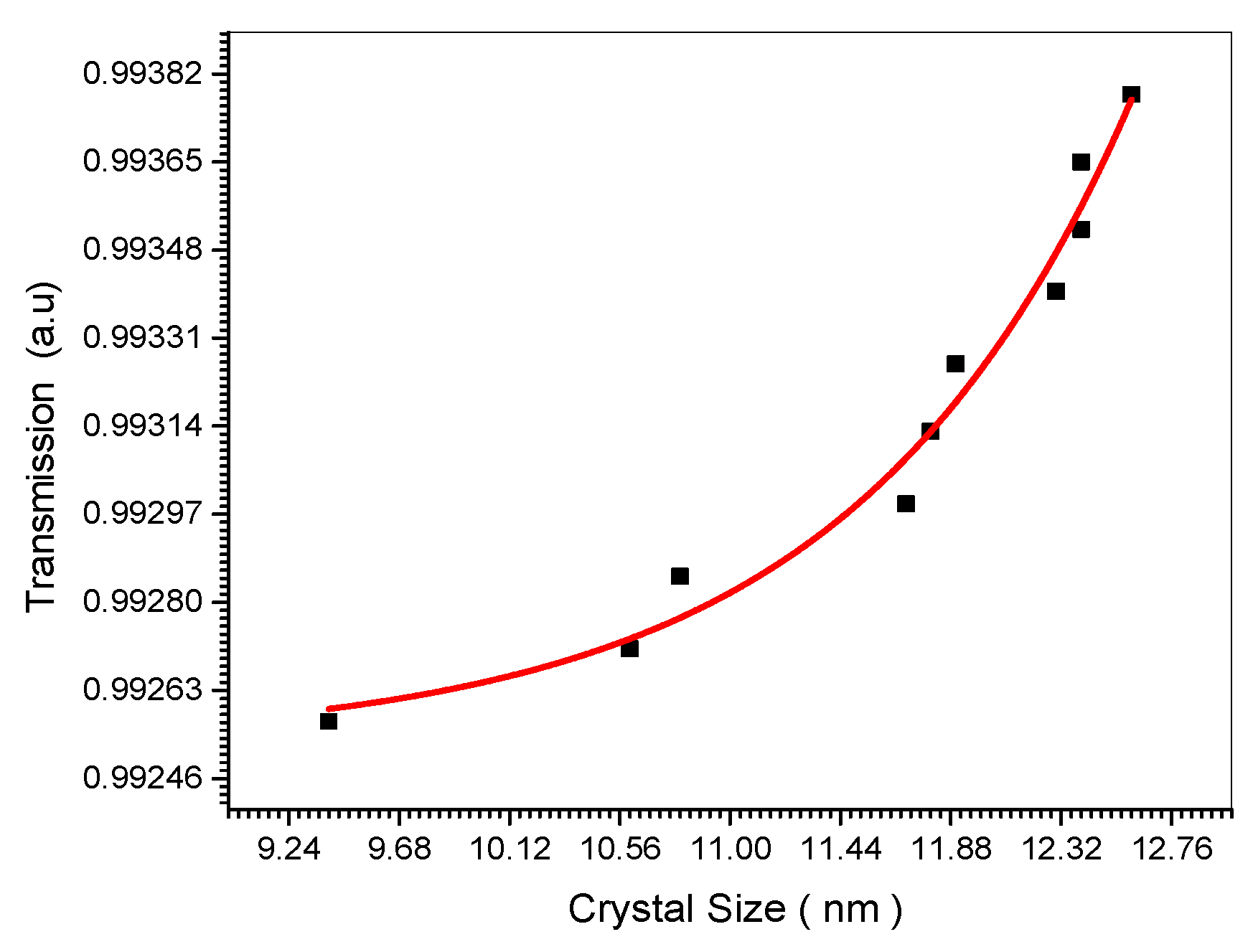

This is confirmed theoretically in Equation (32). The experimental curve in

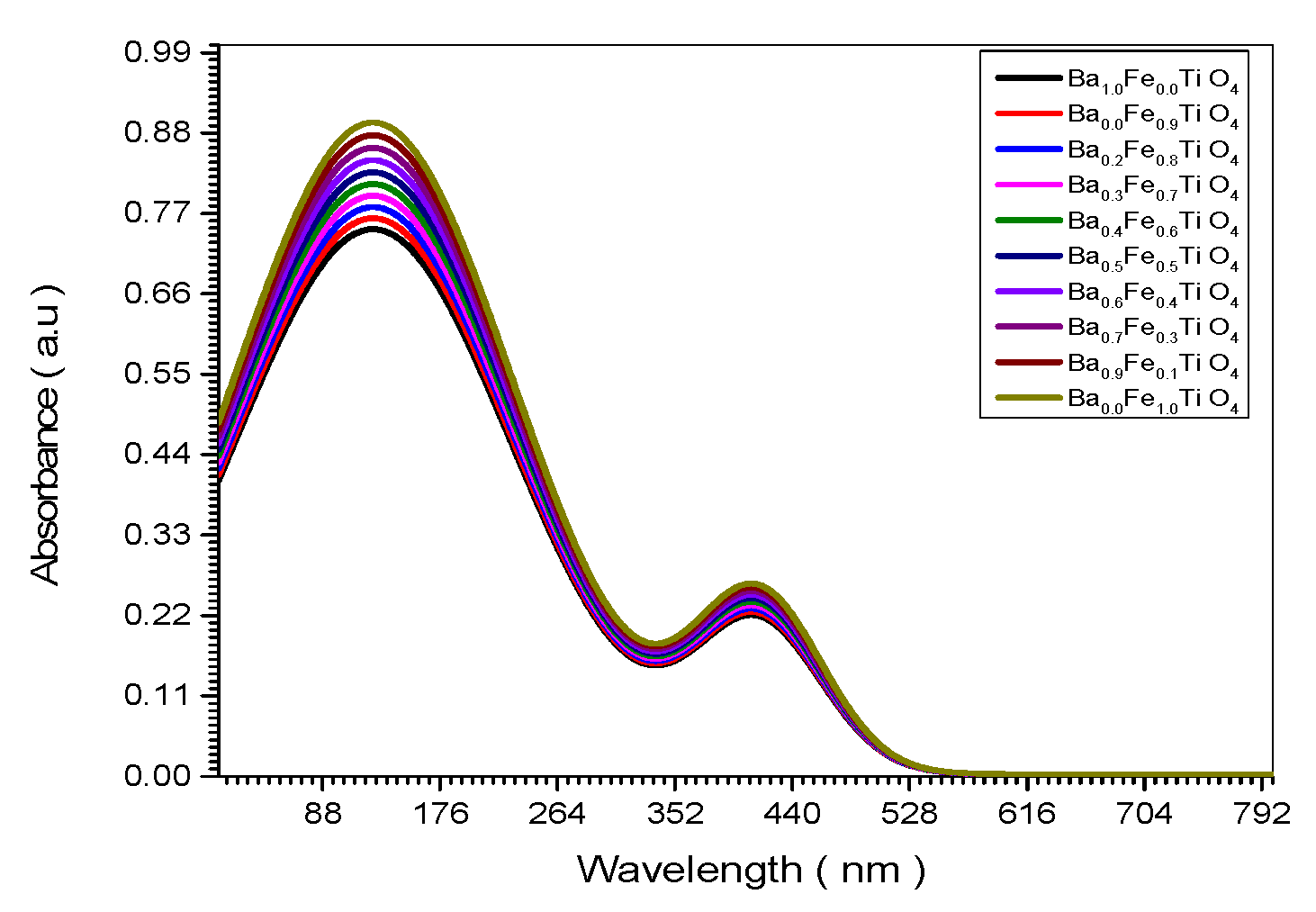

Figure 12 which shows the increase of transmission with the increase of the nano crystal size is explained theoretically in Equations (23) and (24).

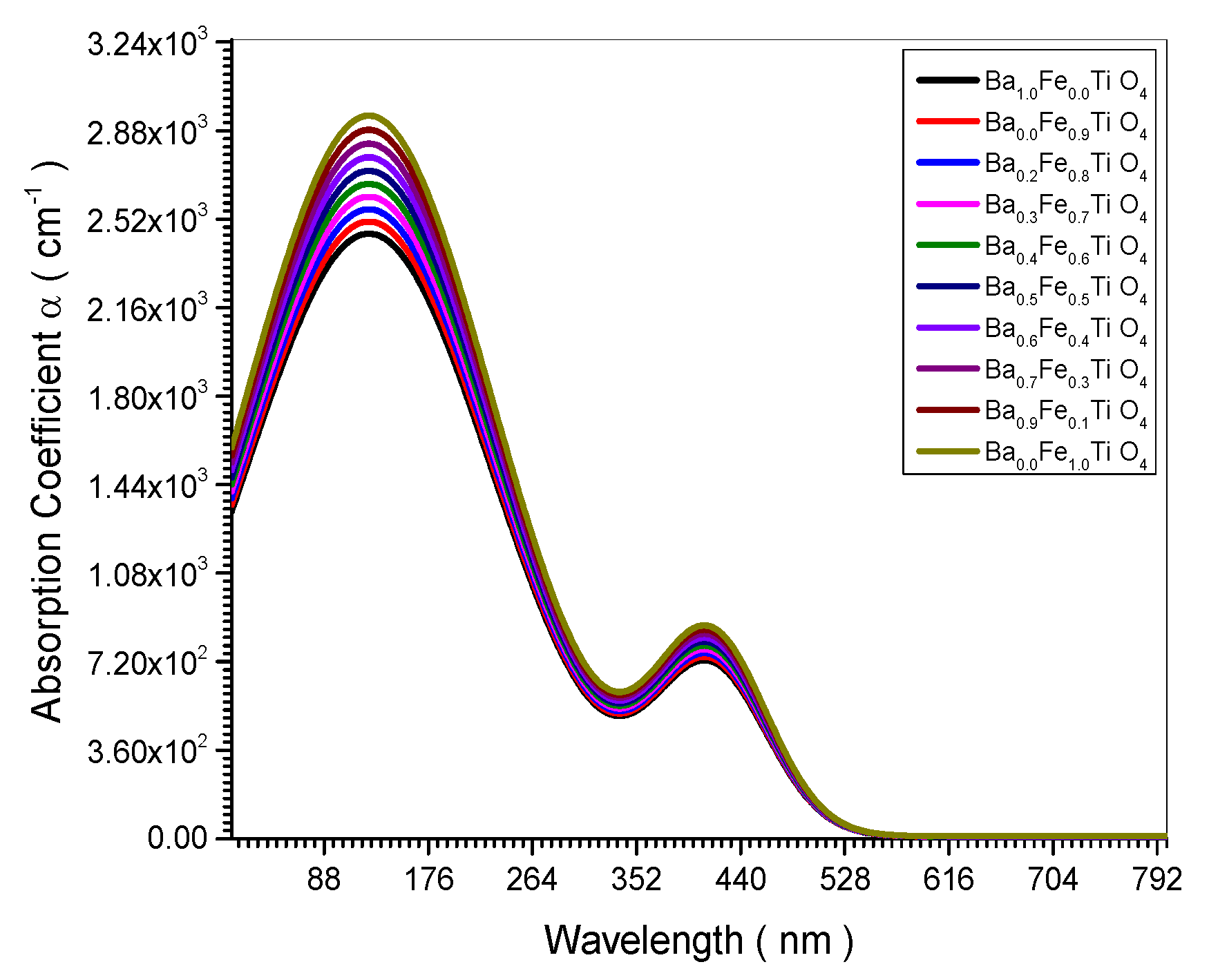

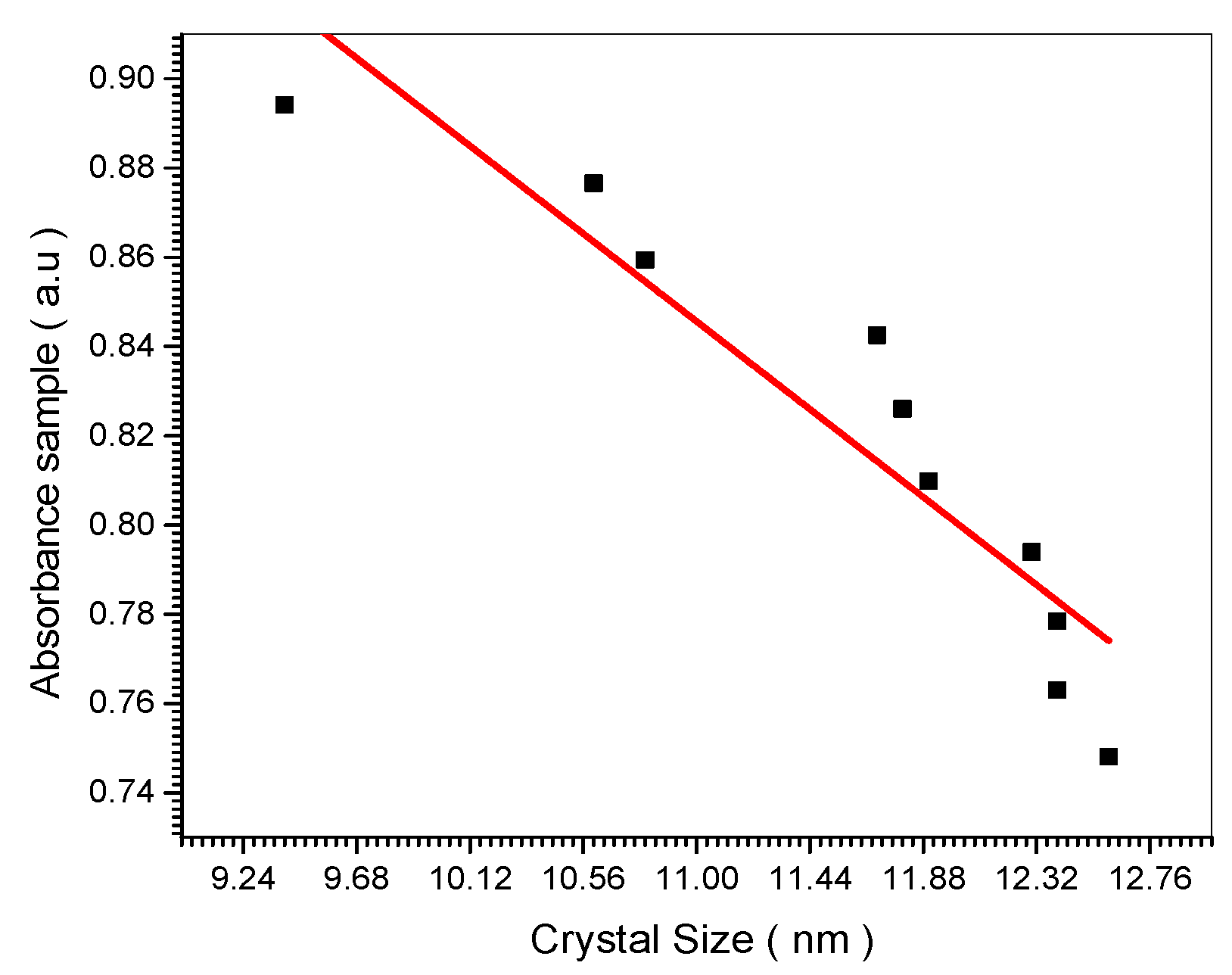

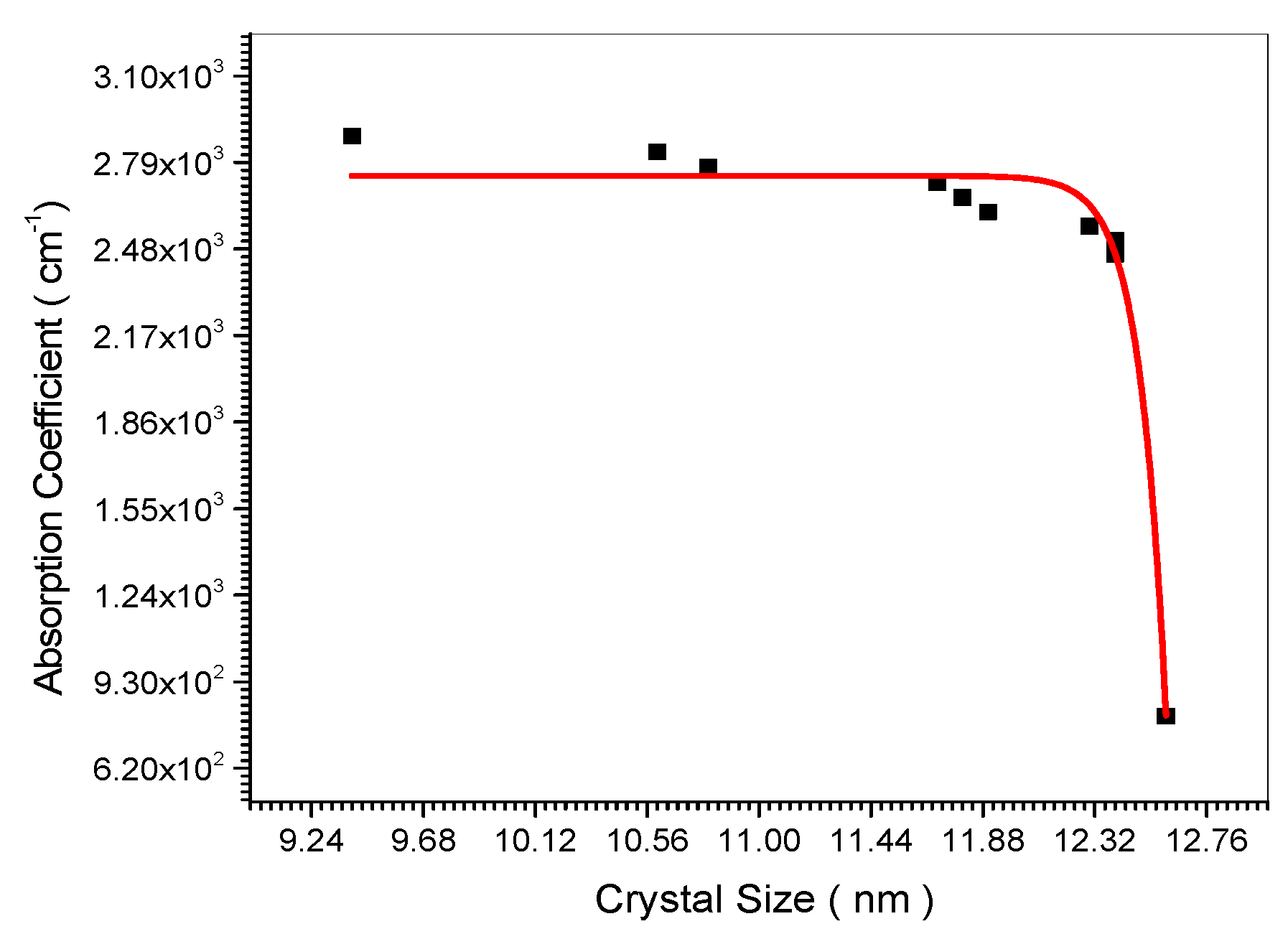

Figure 13 and

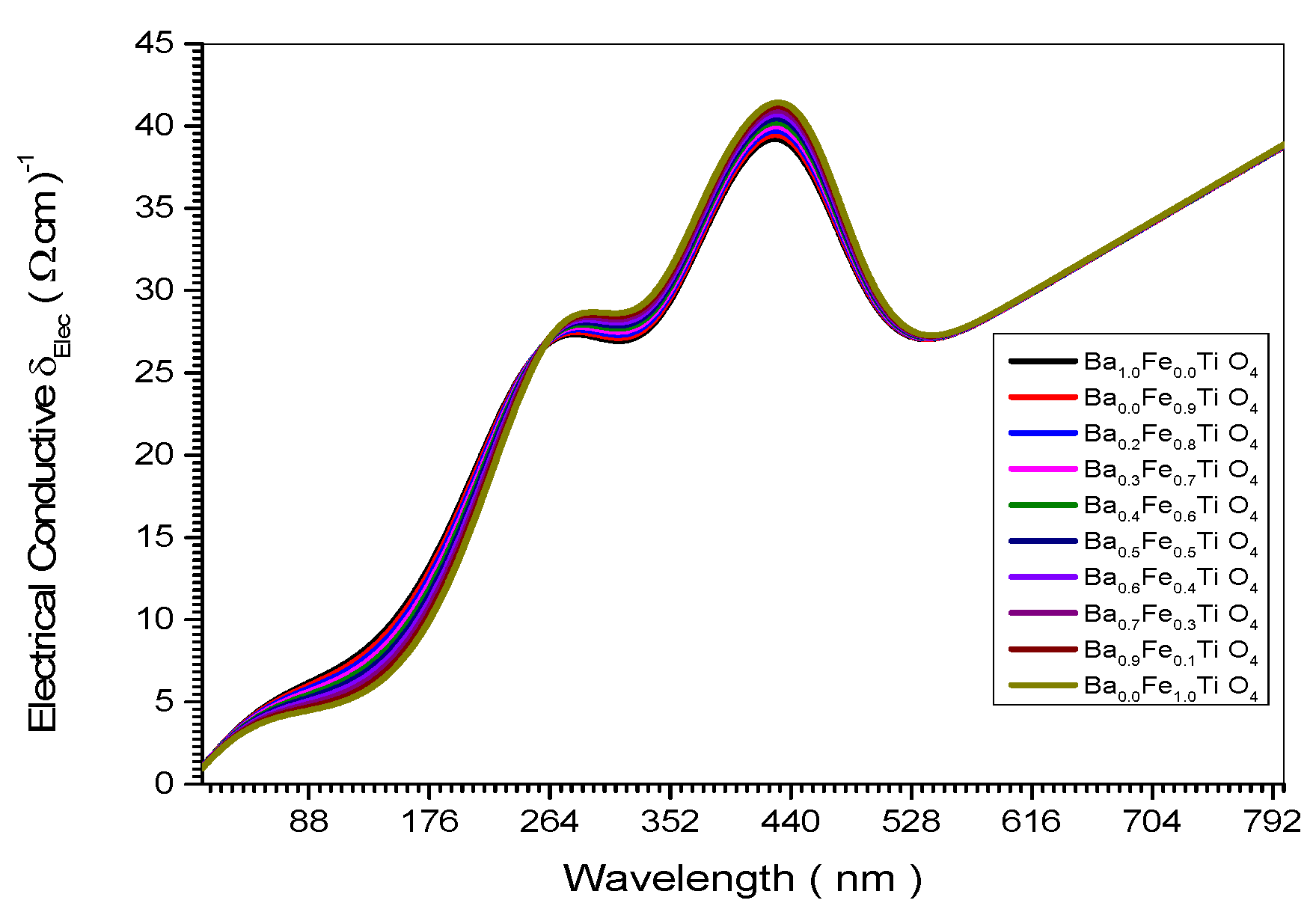

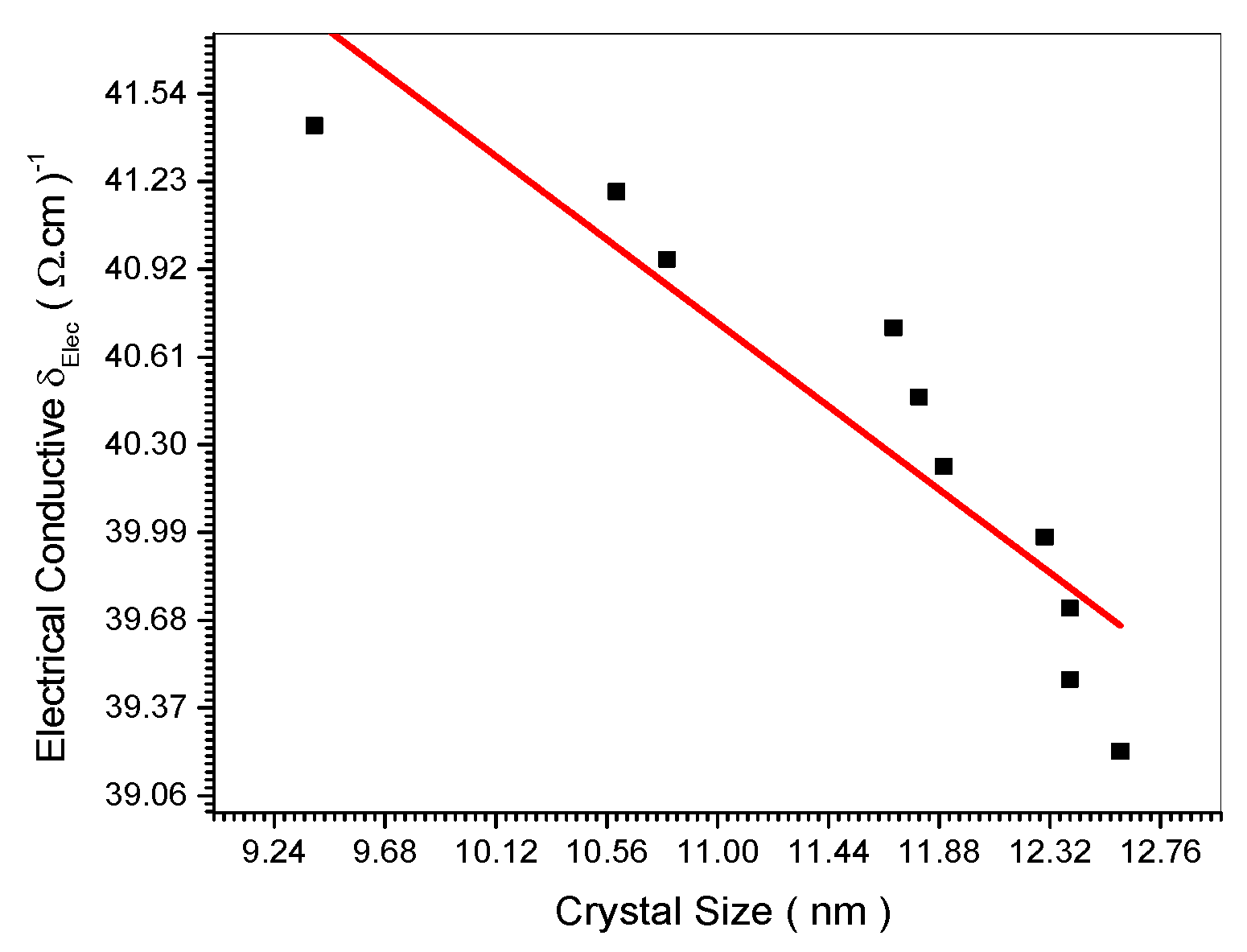

Figure 14 indicated experimentally the decrease of the absorbance and absorption coefficient with the increase of the nano crystal size. This is confirmed theoretically in equation (24). The electrical conductivity decreases upon increasing the nano crystal size as the empirical curve indicated in

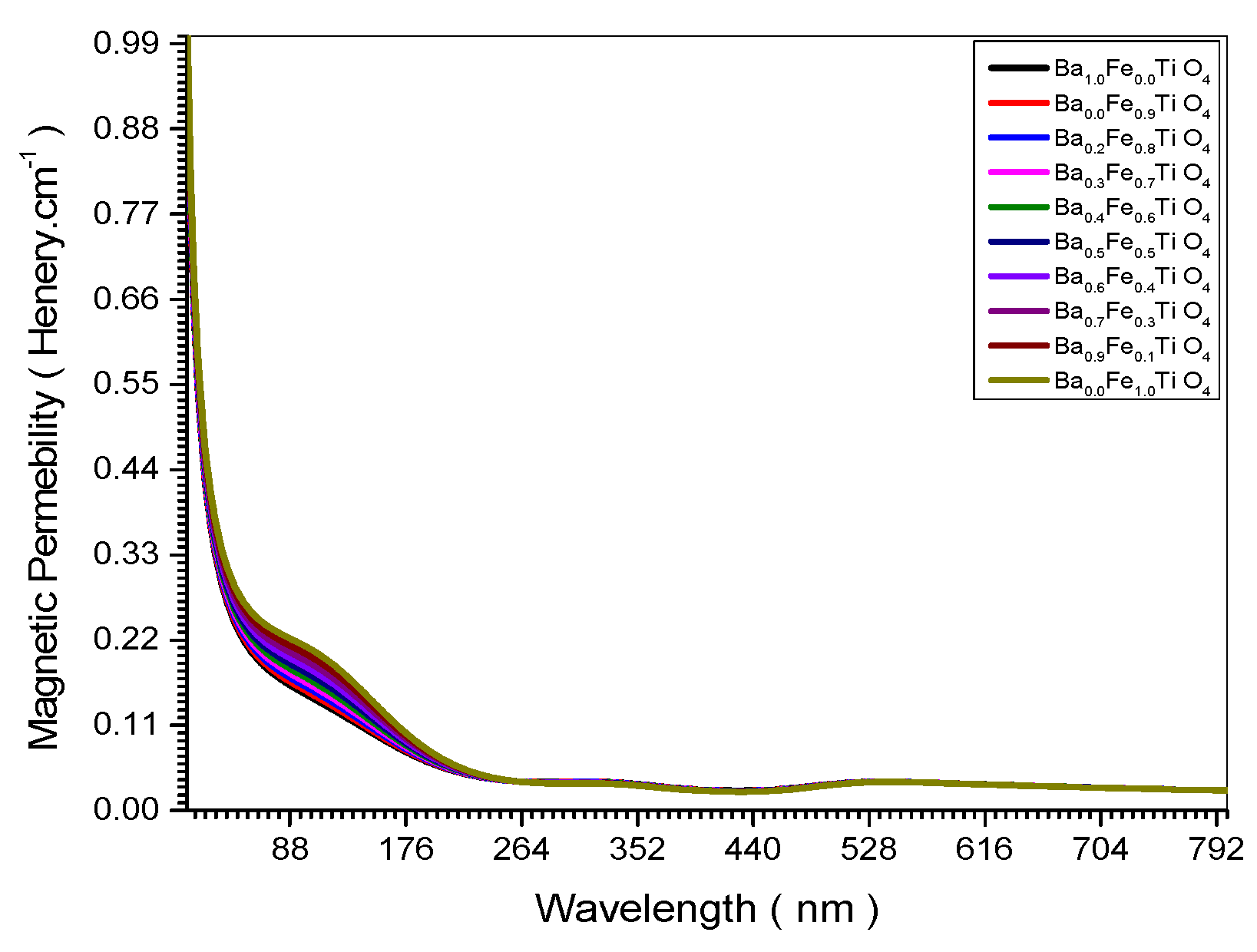

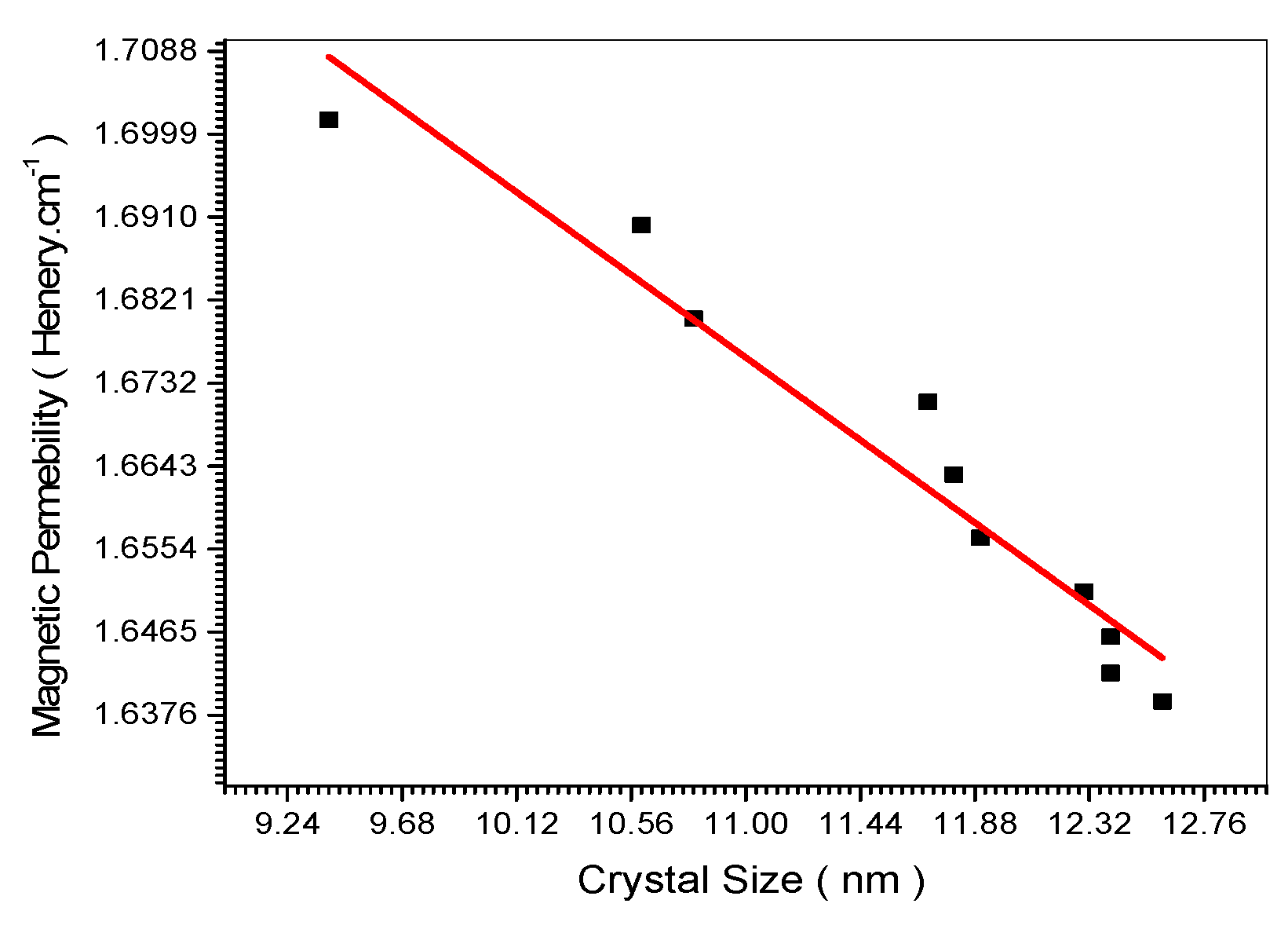

Figure 17. This is confirmed theoretically in Equation (27). The empirical relation in

Figure 18 showed decrease of the magnetic permeability upon increasing the nano crystal size. This is confirmed theoretically in Equation (34).

The present work showed change of absorption coefficient, transmitivity, conductivity, refractive index upon changing the nano size. This agrees with the work of Anup Bist [

15] which indicated that changing nano structure like surface passivation increases stability. Mehra paper [

16] confirm our results which indicated that halide variation changes the band gap which is related to the absorption coefficient. The change of halide doping (Cl, Br, I) Changes the band gap which becomes lower for I. George G.Njema [

18] also obtained the same foundations, since it indicated that increasing crystallization degree increases efficiency which is related to the absorption coefficient and conductivity. The same results were found by Saemi Takahashi [

19] where improving degree of crystallization increases the efficiency. Similarly, Ningya Ren [

20] showed that increase of crystal orientation increases the efficiency. The paper of Sekai Tombe [

21] also indicated as in our work that changing the nano structure by changing the halide doping element changes the band gap width which changes the absorption coefficient. The work of Nisar Ali [

23] which exhibits researcher s attempts to improve the perovskite performance. The paper indicated that the nano size is one of the factors that affect cells efficiency.

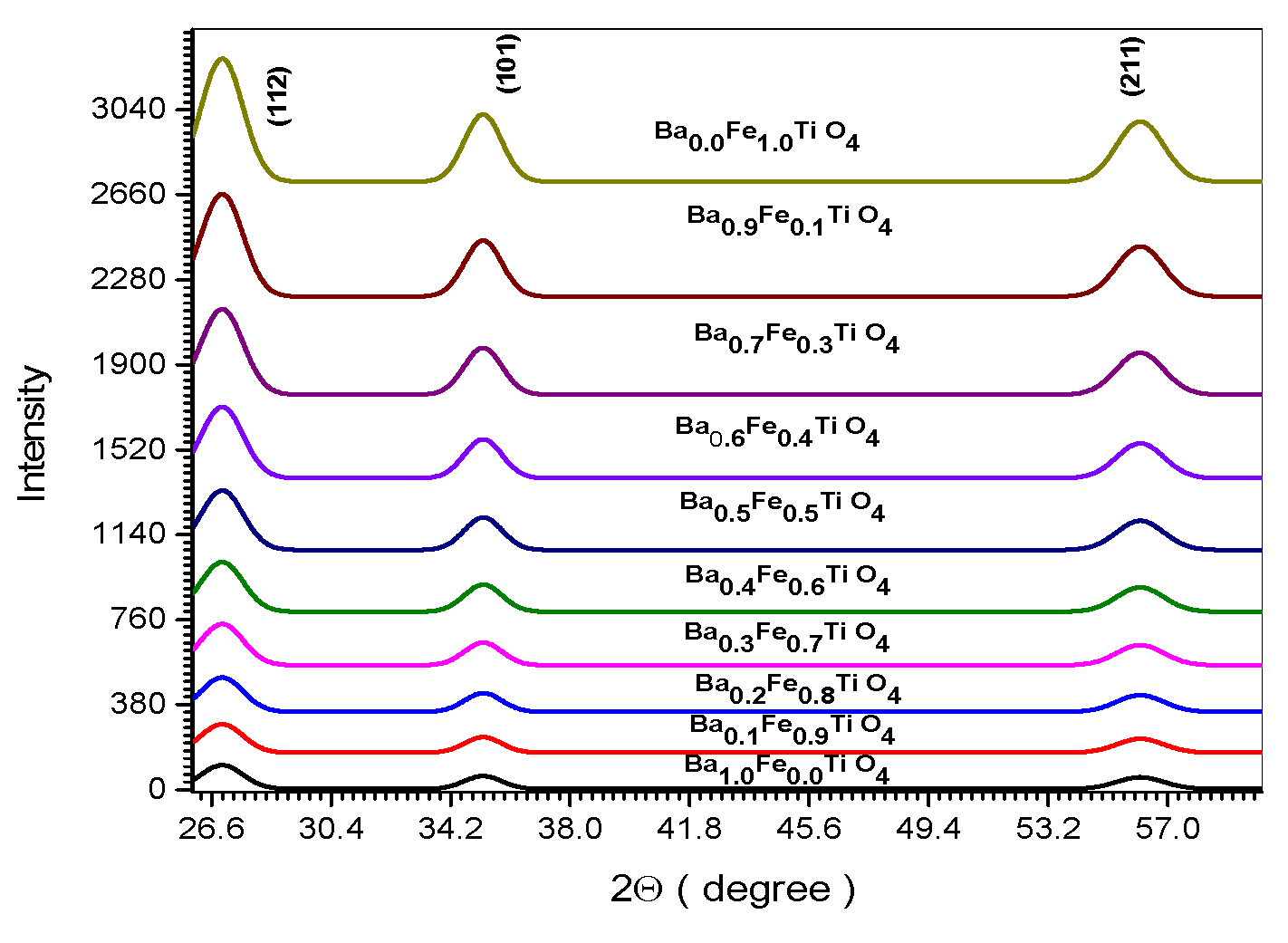

Figure 1.

XRD spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 1.

XRD spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 2.

Absorbance spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 2.

Absorbance spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 3.

Absorption Coefficient spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 3.

Absorption Coefficient spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

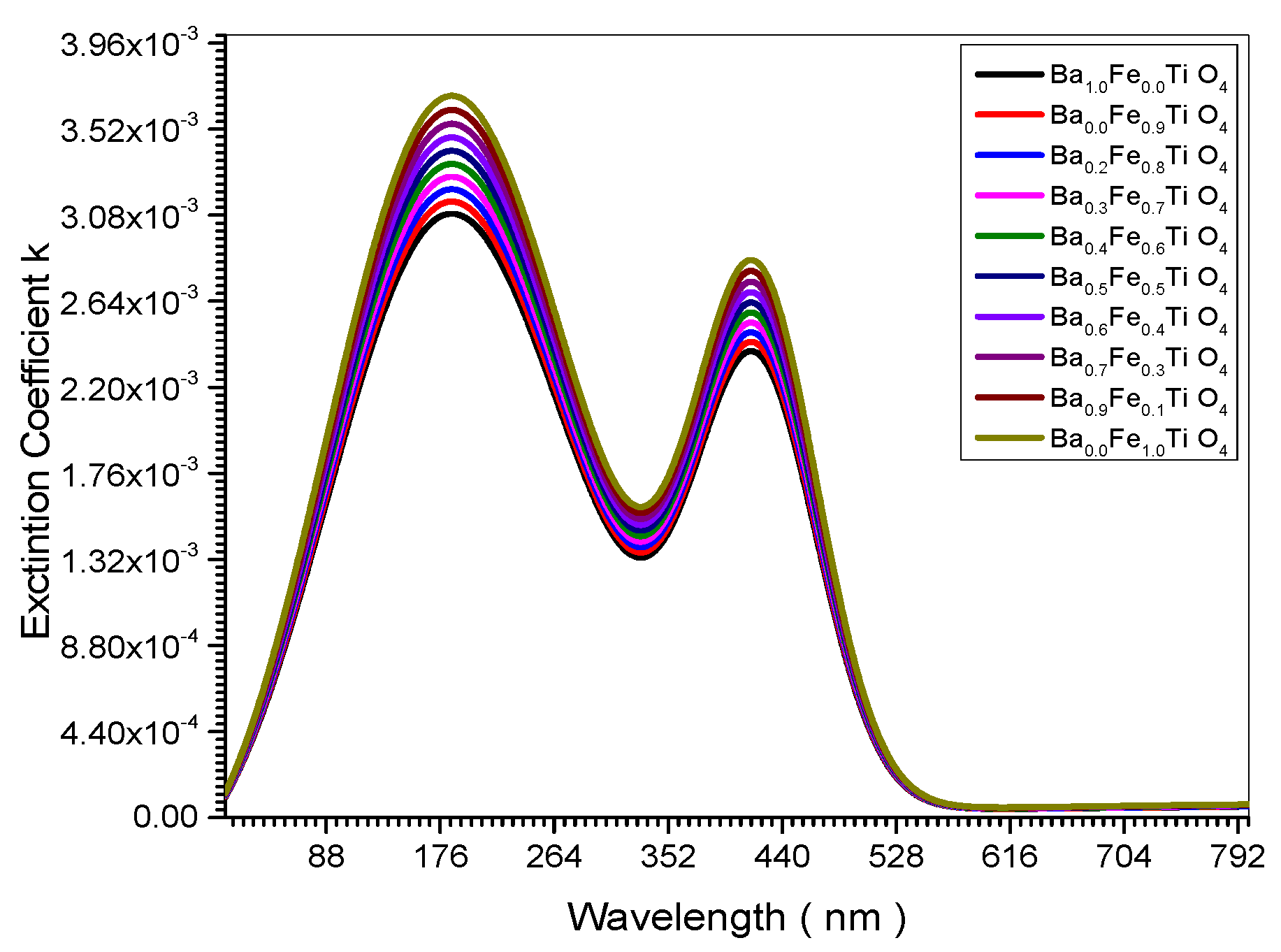

Figure 4.

Absorption Coefficient spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 4.

Absorption Coefficient spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 5.

Transmissions spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 5.

Transmissions spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

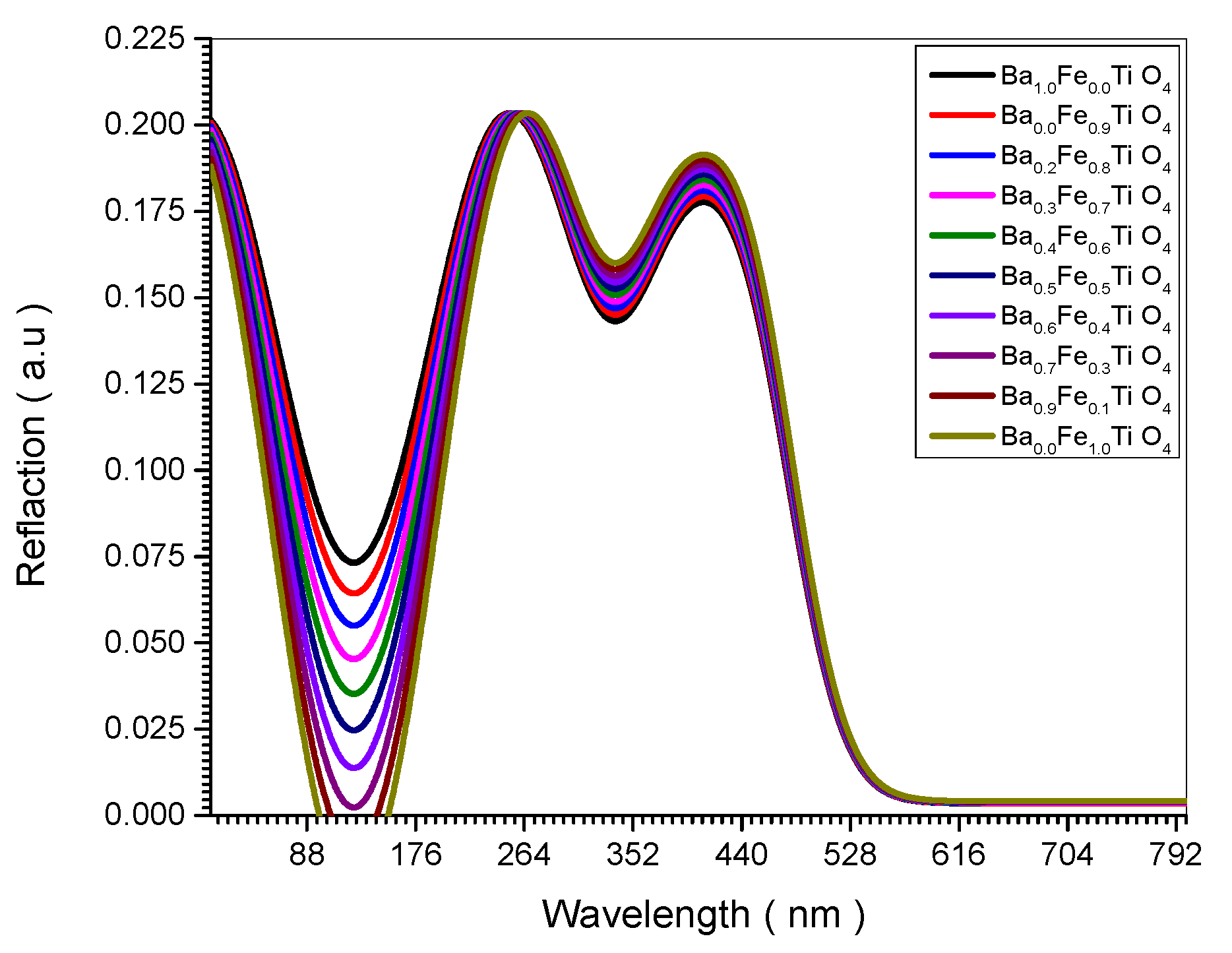

Figure 6.

Reflection spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 6.

Reflection spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 7.

Refractive Index spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 7.

Refractive Index spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

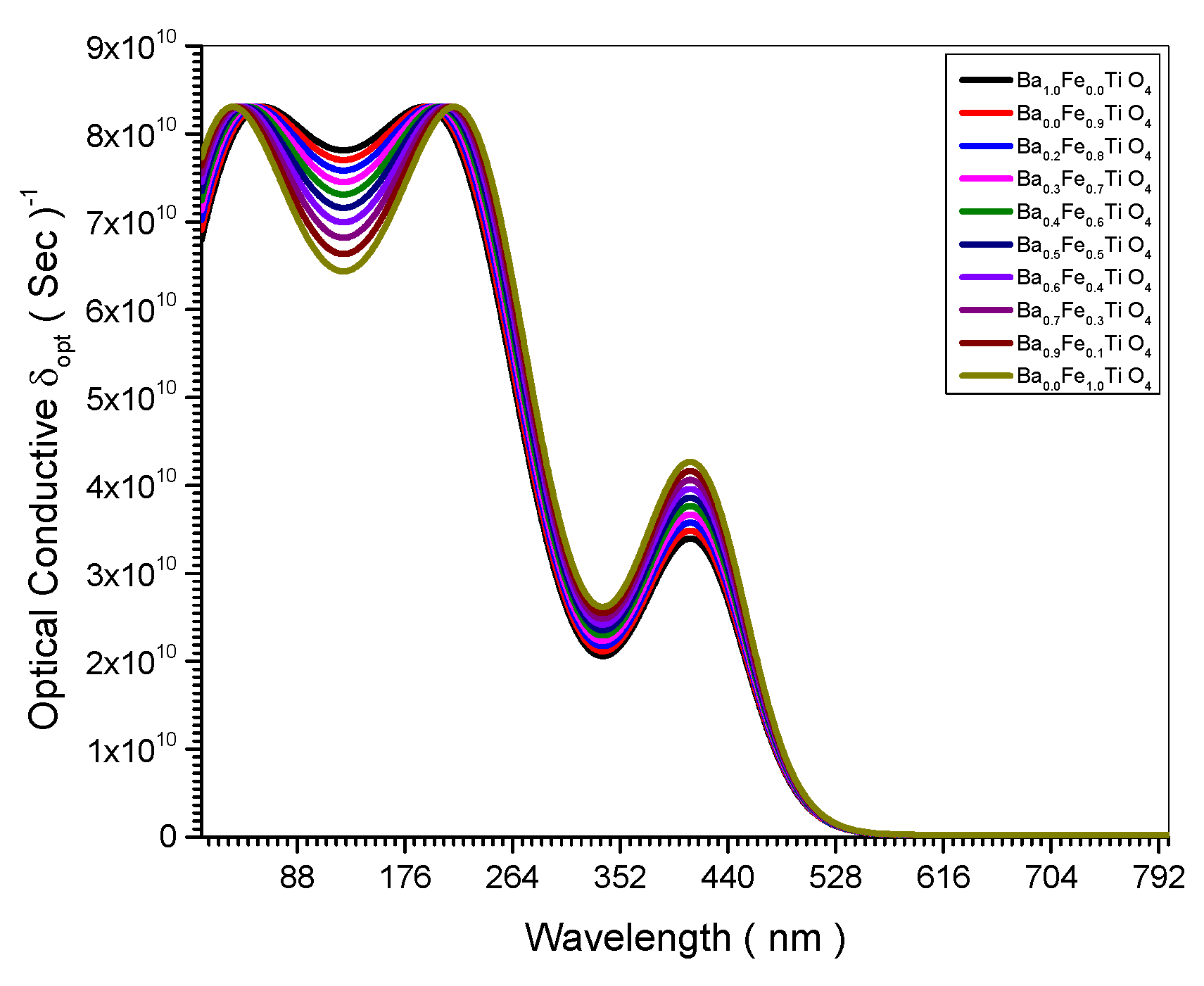

Figure 8.

Optical Conductive spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 8.

Optical Conductive spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 9.

Electrical Conductive spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 9.

Electrical Conductive spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 10.

Magnetic Permeability spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Figure 10.

Magnetic Permeability spectrum of all (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) samples.

Table 1.

some crystallite lattice parameter (Xs (nm) and d – spacing) of (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) (1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7,08 and 0) Molar and Maximum optical properties value (Absorbance, Absorption Coefficient, Extinction Coefficient, Reflection, Refractive Index and Transmissions).

Table 1.

some crystallite lattice parameter (Xs (nm) and d – spacing) of (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) (1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7,08 and 0) Molar and Maximum optical properties value (Absorbance, Absorption Coefficient, Extinction Coefficient, Reflection, Refractive Index and Transmissions).

| Sample |

Absorbance (a.u) |

Absorption Coefficient ( cm-1) |

Extinction Coefficient k |

Reflection ( a.u ) |

Refractive Index |

Transmissions (a.u) |

Xs(nm) |

d-spacing |

| Ba0.0Fe1.0TiO4 |

0.74814 |

806.69706 |

0.00309 |

0.20349 |

2.15244 |

0.99378 |

12.6 |

2.5861 |

| Ba0.1Fe0.9TiO4 |

0.7631 |

2461.38143 |

0.00315 |

0.20349 |

2.15244 |

0.99365 |

12.4 |

2.5860 |

| Ba0.2Fe0.8TiO4 |

0.77837 |

2510.60905 |

0.00321 |

0.20349 |

2.15244 |

0.99352 |

12.4 |

2.5859 |

| Ba0.3Fe0.7TiO4 |

0.79393 |

2560.82124 |

0.00328 |

0.20349 |

2.15244 |

0.9934 |

12.3 |

2.5858 |

| Ba0.5Fe0.5TiO4 |

0.80981 |

2612.03766 |

0.00334 |

0.20349 |

2.15243 |

0.99326 |

11.9 |

2.5856 |

| Ba0.6Fe0.4TiO4 |

0.82601 |

2664.27841 |

0.00341 |

0.20349 |

2.15242 |

0.99313 |

11.8 |

2.5455 |

| Ba0.7Fe0.3TiO4 |

0.84253 |

2717.56398 |

0.00348 |

0.20349 |

2.15242 |

0.99299 |

11.7 |

2.5433 |

| Ba0.8Fe0.2TiO4 |

0.85938 |

2771.91526 |

0.00355 |

0.20349 |

2.15242 |

0.99285 |

10.8 |

2.5432 |

| Ba0.9Fe0.1TiO4 |

0.87657 |

2827.35357 |

0.00362 |

0.20349 |

2.15241 |

0.99271 |

10.6 |

2.5431 |

| Ba10Fe0.0TiO4 |

0.89410 |

2883.90064 |

0.00369 |

0.20349 |

2.15242 |

0.99257 |

9.4 |

2.5430 |

Table 2.

some crystallite lattice parameter (Xs (nm) and d – spacing) of (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) (1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7,08 and 0) Molar and Maximum physical properties value.

Table 2.

some crystallite lattice parameter (Xs (nm) and d – spacing) of (Ba x Fe (1-x) Ti O4) (1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7,08 and 0) Molar and Maximum physical properties value.

| Sample |

Optical Conductive ( 10 10 Sec ) -1

|

Electrical Conductive ( Ω.cm ) -1

|

Magnetic Permeability ( Henery.cm-1) |

Xs(nm) |

d-spacing |

| Ba0.0Fe1.0TiO4 |

8.30733 |

39.21728 |

1.63904 |

12.6 |

2.5861 |

| Ba0.1Fe0.9TiO4 |

8.30733 |

39.4708 |

1.64209 |

12.4 |

2.5860 |

| Ba0.2Fe0.8TiO4 |

8.30734 |

39.72292 |

1.646 |

12.4 |

2.5859 |

| Ba0.3Fe0.7TiO4 |

8.3073 |

39.97391 |

1.65083 |

12.3 |

2.5858 |

| Ba0.5Fe0.5TiO4 |

8.30732 |

40.22262 |

1.6566 |

11.9 |

2.5856 |

| Ba0.6Fe0.4TiO4 |

8.30728 |

40.46884 |

1.66337 |

11.8 |

2.5455 |

| Ba0.7Fe0.3TiO4 |

8.30734 |

40.71322 |

1.67118 |

11.7 |

2.5433 |

| Ba0.8Fe0.2TiO4 |

8.30733 |

40.95416 |

1.68009 |

10.8 |

2.5432 |

| Ba0.9Fe0.1TiO4 |

8.30731 |

41.19251 |

1.69015 |

10.6 |

2.5431 |

| Ba10Fe0.0TiO4 |

8.3073 |

41.42708 |

1.70143 |

9.4 |

2.5430 |

Figure 11.

Relation between Refractive index and crystal size.

Figure 11.

Relation between Refractive index and crystal size.

Figure 12.

Relation between Transmission and crystal size.

Figure 12.

Relation between Transmission and crystal size.

Figure 13.

Relation between Absorbance sample and crystal size.

Figure 13.

Relation between Absorbance sample and crystal size.

Figure 14.

Relation between Absorption coefficient and crystal size.

Figure 14.

Relation between Absorption coefficient and crystal size.

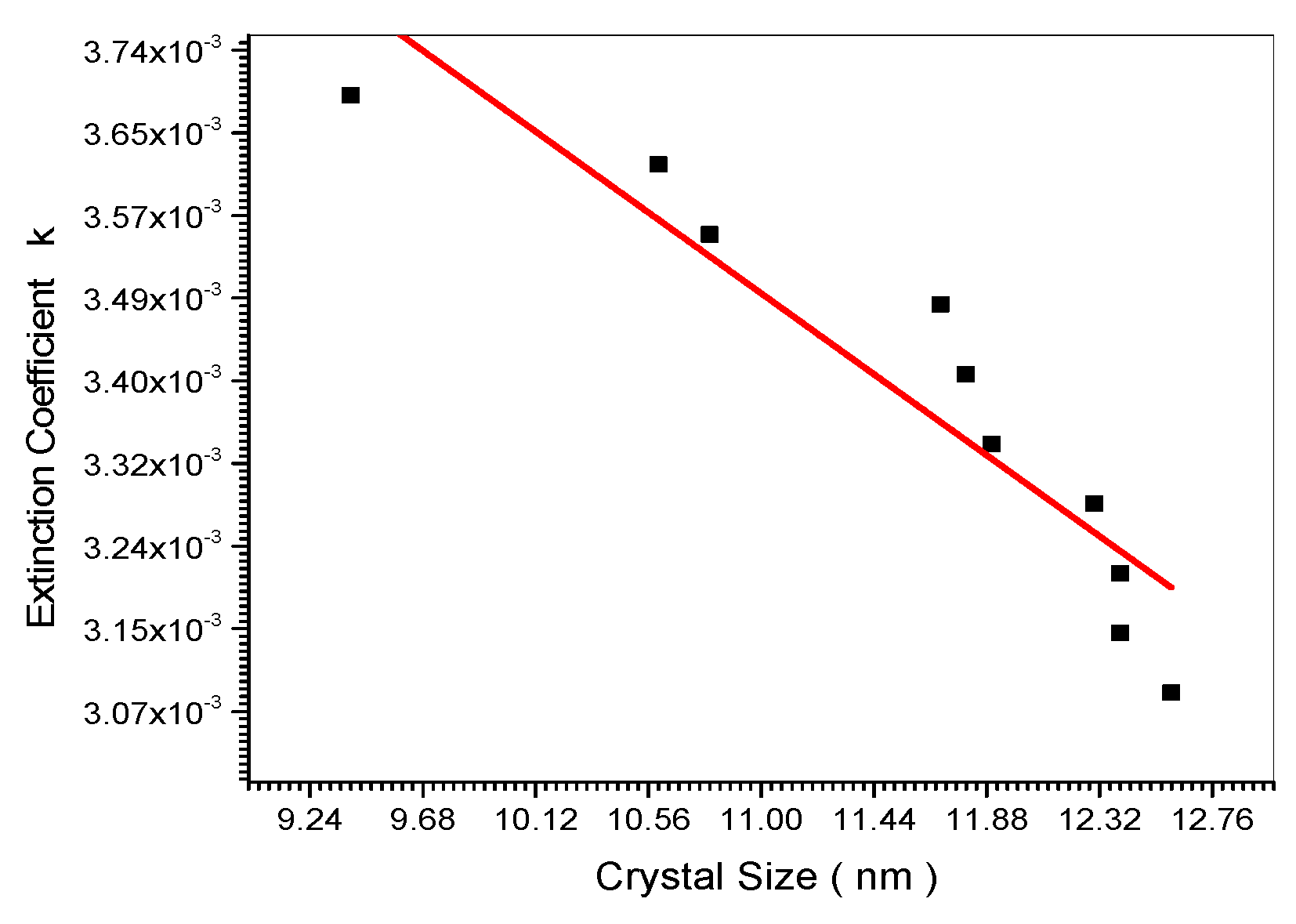

Figure 15.

Relation between Extinction Coefficient and crystal size.

Figure 15.

Relation between Extinction Coefficient and crystal size.

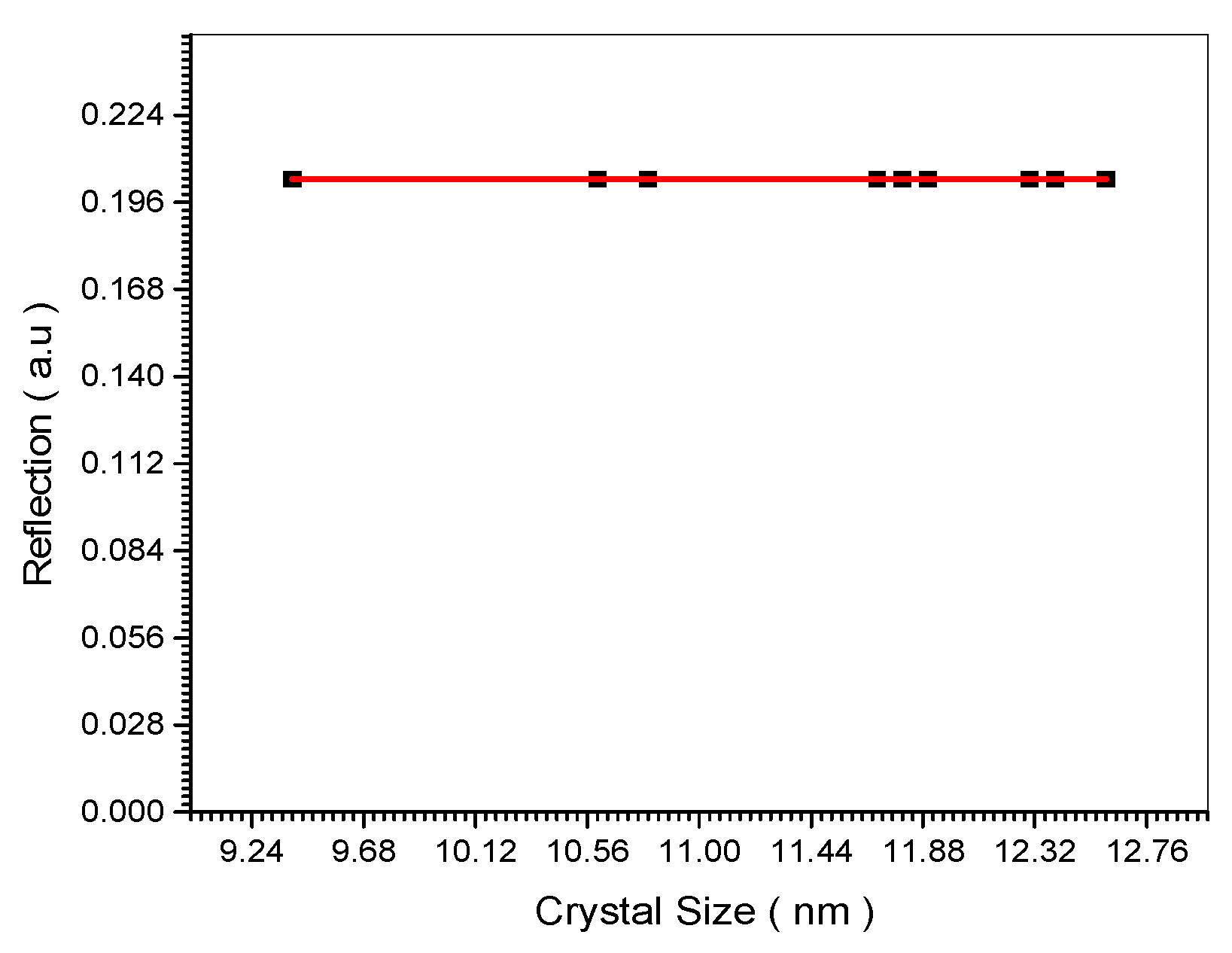

Figure 16.

Relation between Reflection and crystal size.

Figure 16.

Relation between Reflection and crystal size.

Figure 17.

Relation between Electrical Conductive and crystal size.

Figure 17.

Relation between Electrical Conductive and crystal size.

Figure 18.

Relation between Magnetic Permeability and crystal size.

Figure 18.

Relation between Magnetic Permeability and crystal size.