Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

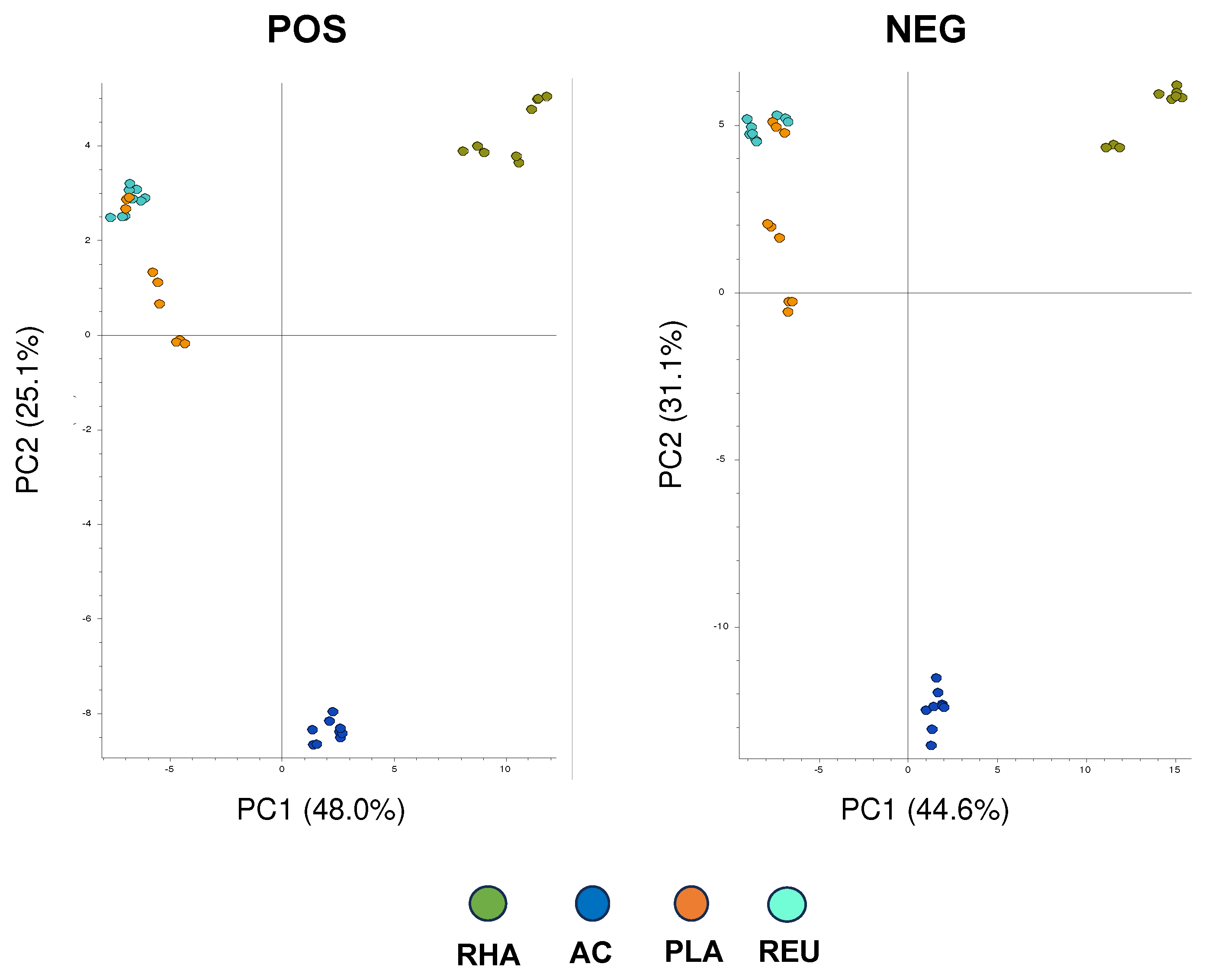

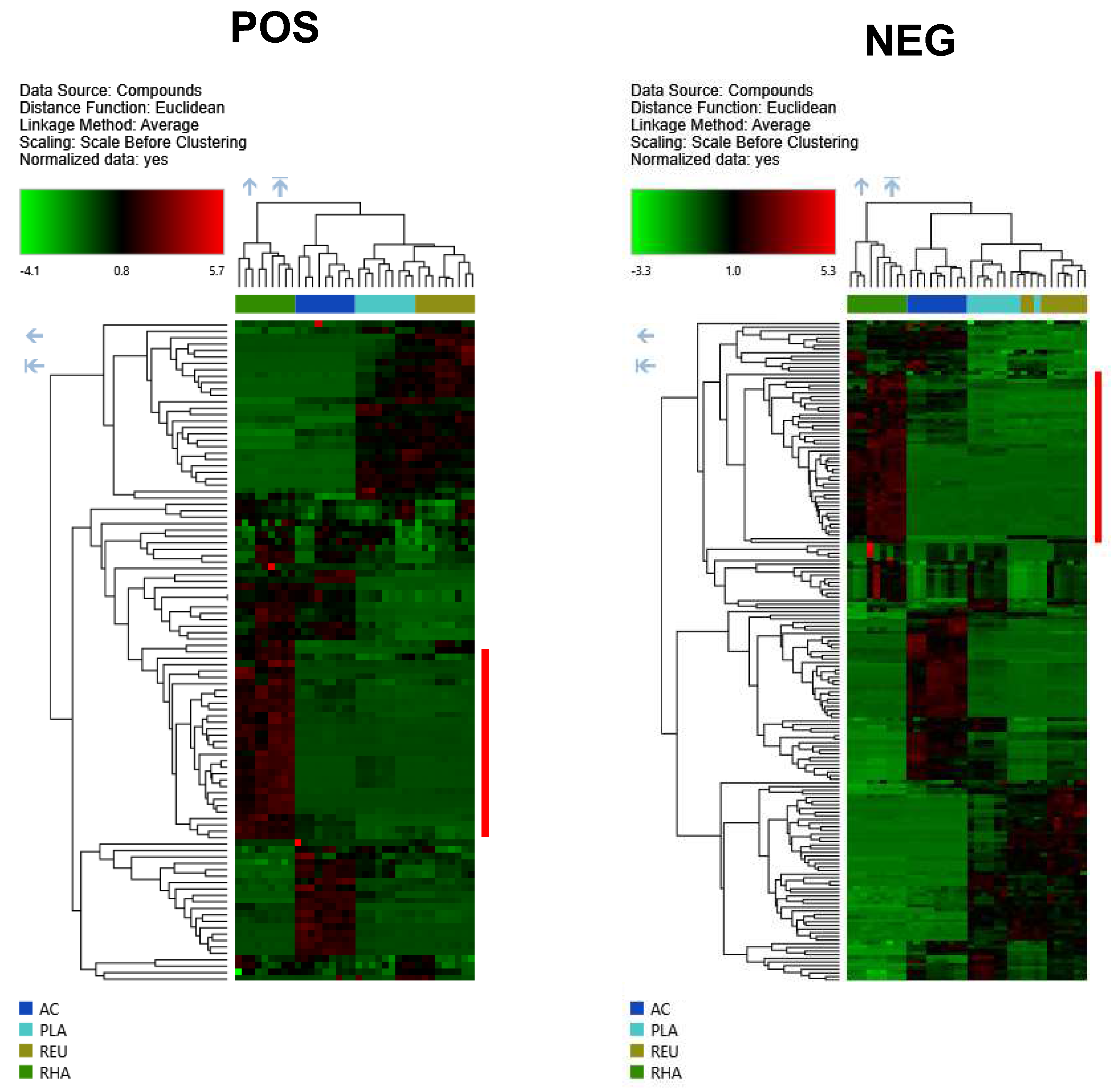

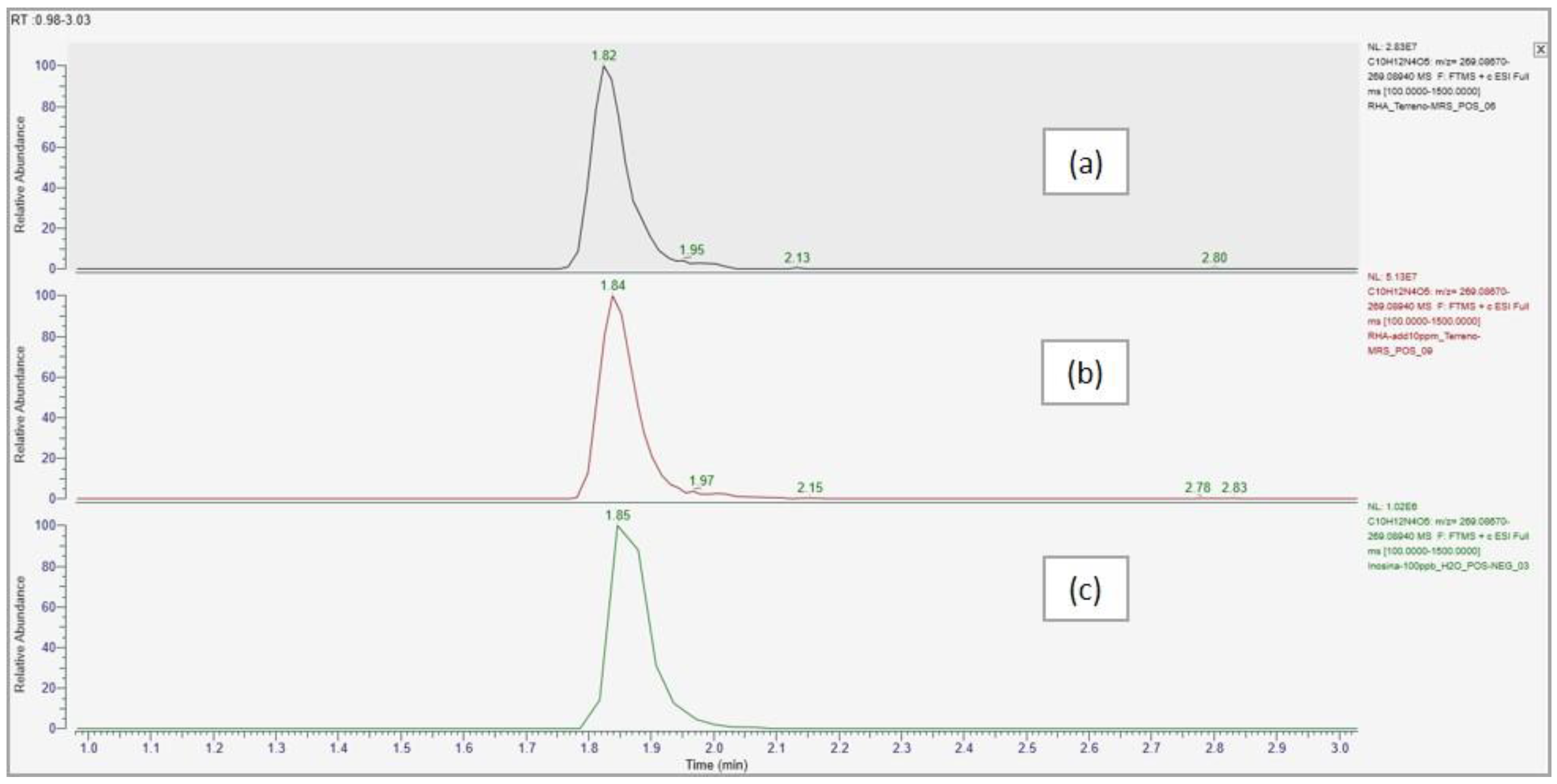

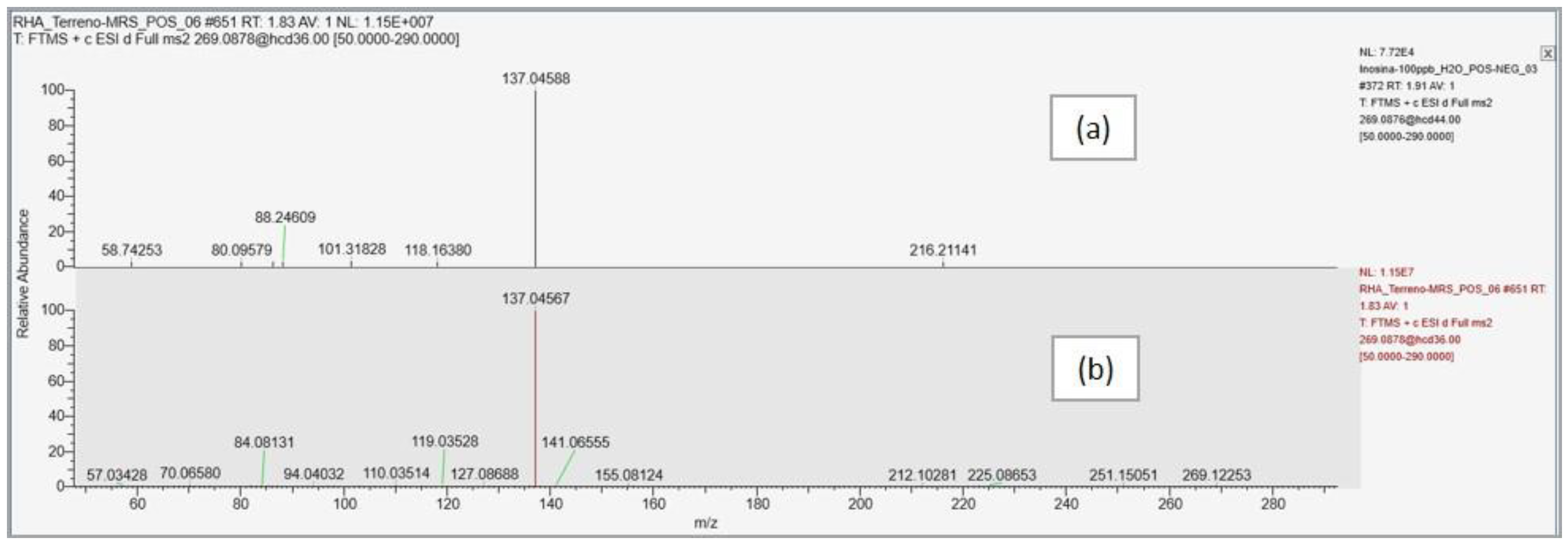

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latif, A.; Shehzad, A.; Niazi, S.; Zahid, A.; Ashraf, W.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rehman, A.; Riaz, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Khan, I.M.; et al. Probiotics: Mechanism of Action, Health Benefits and Their Application in Food Industries. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1216674. [CrossRef]

- Ayivi, R.D.; Gyawali, R.; Krastanov, A.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Worku, M.; Tahergorabi, R.; Silva, R.C.D.; Ibrahim, S.A. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Food Safety and Human Health Applications. Dairy 2020, 1, 202–232. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Lu, Z. Health Promoting Activities of Probiotics. J Food Biochem 2019, 43. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wu, F.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, W.; Yue, J.; Xiao, B.; Luo, Z. Lactobacillus and Intestinal Diseases: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Applications. Microbiological Research 2022, 260, 127019. [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Xing, D. The Current and Future Perspectives of Postbiotics. Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot. 2023, 15, 1626–1643. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Sieiro, P.; Montalbán-López, M.; Mu, D.; Kuipers, O.P. Bacteriocins of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Extending the Family. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 2939–2951. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.F.; Clarke, S.F.; Marques, T.M.; Hill, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; O’Doherty, R.M.; Shanahan, F.; Cotter, P.D. Antimicrobials: Strategies for Targeting Obesity and Metabolic Health? Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Abreu Y Abreu, A.T.; Gwee, K.A.; Ianiro, G.; Tack, J.; Nguyen, T.V.H.; Hill, C. The Clinical Evidence for Postbiotics as Microbial Therapeutics. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2117508. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Roman, R.; Last, A.; Mirhakkak, M.H.; Sprague, J.L.; Möller, L.; Großmann, P.; Graf, K.; Gratz, R.; Mogavero, S.; Vylkova, S.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus Colonisation Antagonizes Candida albicans by Forcing Metabolic Adaptations That Compromise Pathogenicity. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3192. [CrossRef]

- Thoda, C.; Touraki, M. Immunomodulatory Properties of Probiotics and Their Derived Bioactive Compounds. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4726. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hakim, B.N.; Xuan, N.J.; Oslan, S.N.H. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Compounds from Lactic Acid Bacteria: Potential Functions as Functional Food in Dietetics and the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 2850. [CrossRef]

- Spaggiari, L.; Sala, A.; Ardizzoni, A.; De Seta, F.; Singh, D.K.; Gacser, A.; Blasi, E.; Pericolini, E. Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, and L. reuteri Cell-Free Supernatants Inhibit Candida parapsilosis Pathogenic Potential upon Infection of Vaginal Epithelial Cells Monolayer and in a Transwell Coculture System In Vitro. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e02696-21. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.; Cristofaro, V.; Sullivan, M.P.; Adam, R.M. Inosine - a Multifunctional Treatment for Complications of Neurologic Injury. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 49, 2293–2303. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Kind, T.; Cajka, T.; Hazen, S.L.; Tang, W.H.W.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Irvin, M.R.; Arnett, D.K.; Barupal, D.K.; Fiehn, O. Systematic Error Removal Using Random Forest for Normalizing Large-Scale Untargeted Lipidomics Data. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 3590–3596. [CrossRef]

- Züllig, T.; Zandl-Lang, M.; Trötzmüller, M.; Hartler, J.; Plecko, B.; Köfeler, H.C. A Metabolomics Workflow for Analyzing Complex Biological Samples Using a Combined Method of Untargeted and Target-List Based Approaches. Metabolites 2020, 10, 342. [CrossRef]

- Shafy, A.; Molinié, V.; Cortes-Morichetti, M.; Hupertan, V.; Lila, N.; Chachques, J.C. Comparison of the Effects of Adenosine, Inosine, and Their Combination as an Adjunct to Reperfusion in the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction. ISRN Cardiology 2012, 2012, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Intestinal Health and Disease: From Biology to the Clinic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16, 605–616. [CrossRef]

- De Almada, C.N.; De Almada, C.N.; De Souza Sant’Ana, A. Paraprobiotics as Potential Agents for Improving Animal Health. In Probiotics and Prebiotics in Animal Health and Food Safety; Di Gioia, D., Biavati, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 247–268 ISBN 978-3-319-71948-1.

- Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Castro-López, C.; García, H.S.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Hernández-Mendoza, A. Postbiotics and Paraprobiotics: A Review of Current Evidence and Emerging Trends. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 94, pp. 1–34 ISBN 978-0-12-820218-0.

- Martín, R.; Langella, P. Emerging Health Concepts in the Probiotics Field: Streamlining the Definitions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1047. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhong, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, X. Therapeutic and Improving Function of Lactobacilli in the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular-Related Diseases: A Novel Perspective From Gut Microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 693412. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhou, G.; Yang, X.-M.; Chen, G.-J.; Chen, H.-B.; Liao, Z.-L.; Zhong, Q.-P.; Wang, L.; Fang, X.; Wang, J. Transcriptomic Analysis Revealed Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Lactobacillus rhamnosus SCB0119 against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15159. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.B.; Viñas, I.; Colás-Medà, P.; Collazo, C.; Serrano, J.C.E.; Abadias, M. Adhesion and Invasion of Listeria monocytogenes and Interaction with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG after Habituation on Fresh-Cut Pear. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 34, 453–460. [CrossRef]

- Muyyarikkandy, M.S.; Amalaradjou, M. Lactobacillus Bulgaricus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus paracasei Attenuate Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella Heidelberg and Salmonella typhimurium Colonization and Virulence Gene Expression In Vitro. IJMS 2017, 18, 2381. [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, K.M.; Bhunia, A.K. Salmonella enterica Serovar typhimurium Adhesion and Cytotoxicity during Epithelial Cell Stress Is Reduced by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Gut Pathog 2009, 1, 14. [CrossRef]

- Coman, M.M.; Verdenelli, M.C.; Cecchini, C.; Silvi, S.; Orpianesi, C.; Boyko, N.; Cresci, A. In Vitro Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Lactobacillus rhamnosus IMC 501 ® , Lactobacillus paracasei IMC 502 ® and SYNBIO ® against Pathogens. J Appl Microbiol 2014, 117, 518–527. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-G.; Lee, S.-H. Inhibitory Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus casei on Candida Biofilm of Denture Surface. Archives of Oral Biology 2017, 76, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.Y.; Cheah, Y.K.; Seow, H.F.; Sandai, D.; Than, L.T.L. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR -1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC -14 Exhibit Strong Antifungal Effects against Vulvovaginal Candidiasis-causing Candida glabrata Isolates. J Appl Microbiol 2015, 118, 1180–1190. [CrossRef]

- Alseth, I.; Dalhus, B.; Bjørås, M. Inosine in DNA and RNA. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2014, 26, 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Licht, K.; Hartl, M.; Amman, F.; Anrather, D.; Janisiw, M.P.; Jantsch, M.F. Inosine Induces Context-Dependent Recoding and Translational Stalling. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, L.I.; Jing, Y.; Tabibiazar, R.; Jo, S.A.; Petrausch, B.; Stuermer, C.A.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Irwin, N. Axon Outgrowth Is Regulated by an Intracellular Purine-Sensitive Mechanism in Retinal Ganglion Cells. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 29626–29634. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, N.; Li, Y.-M.; O’Toole, J.E.; Benowitz, L.I. Mst3b, a Purine-Sensitive Ste20-like Protein Kinase, Regulates Axon Outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 18320–18325. [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, L.I.; Goldberg, D.E.; Madsen, J.R.; Soni, D.; Irwin, N. Inosine Stimulates Extensive Axon Collateral Growth in the Rat Corticospinal Tract after Injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 13486–13490. [CrossRef]

- Muto, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Uwaya, A.; Park, J.; Nakajima, S.; Nagata, K.; Ohno, M.; Ohsawa, I.; Mikami, T. Oral Administration of Inosine Produces Antidepressant-like Effects in Mice. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4199. [CrossRef]

- Haskó, G.; Sitkovsky, M.V.; Szabó, C. Immunomodulatory and Neuroprotective Effects of Inosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2004, 25, 152–157. [CrossRef]

- Haskó, G.; Kuhel, D.G.; Németh, Z.H.; Mabley, J.G.; Stachlewitz, R.F.; Virág, L.; Lohinai, Z.; Southan, G.J.; Salzman, A.L.; Szabó, C. Inosine Inhibits Inflammatory Cytokine Production by a Posttranscriptional Mechanism and Protects Against Endotoxin-Induced Shock. The Journal of Immunology 2000, 164, 1013–1019. [CrossRef]

- Liaudet, L.; Mabley, J.G.; Soriano, F.G.; Pacher, P.; Marton, A.; Haskó, G.; Szabó, C. Inosine Reduces Systemic Inflammation and Improves Survival in Septic Shock Induced by Cecal Ligation and Puncture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164, 1213–1220. [CrossRef]

| Compound name | Predicted composition | mzCloud Search |

mzValue Search |

Metabolika Search | ChemSpider Search |

MassList Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inosine | Full Match | Full Match | Full Match | Full Match | Partial Match | Partial Match |

| Compound name | Formula | n° identified pathways |

Pathways | Mapped compounds |

Matched compounds |

Compounds in pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inosine | C10H12N4O5 | 1 | Superpathway of purine nucleotide salvage | 14 | 10 | 54 |

| 2 | Purine nucleotides degradation II (aerobic) | 12 | 8 | 27 | ||

| 3 | Purine nucleotides degradation I (plants) | 10 | 7 | 23 | ||

| 4 | Superpathway of purine degradation in plants | 10 | 7 | 34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).