Submitted:

01 February 2024

Posted:

01 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

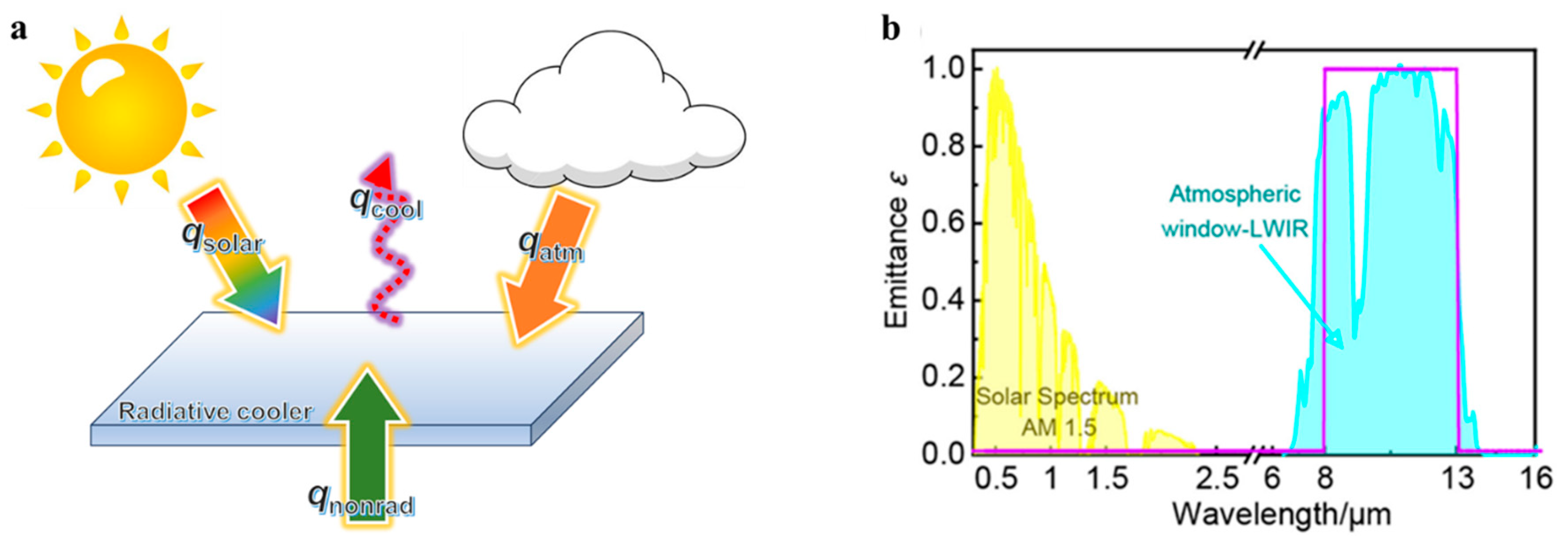

2. Fundamentals of Passive Radiative Cooling

3. Promising Applications of Passive Radiative Cooling

3.1. Building cooling

3.2. Personal thermal management

3.3. Other applications

4. Outlook

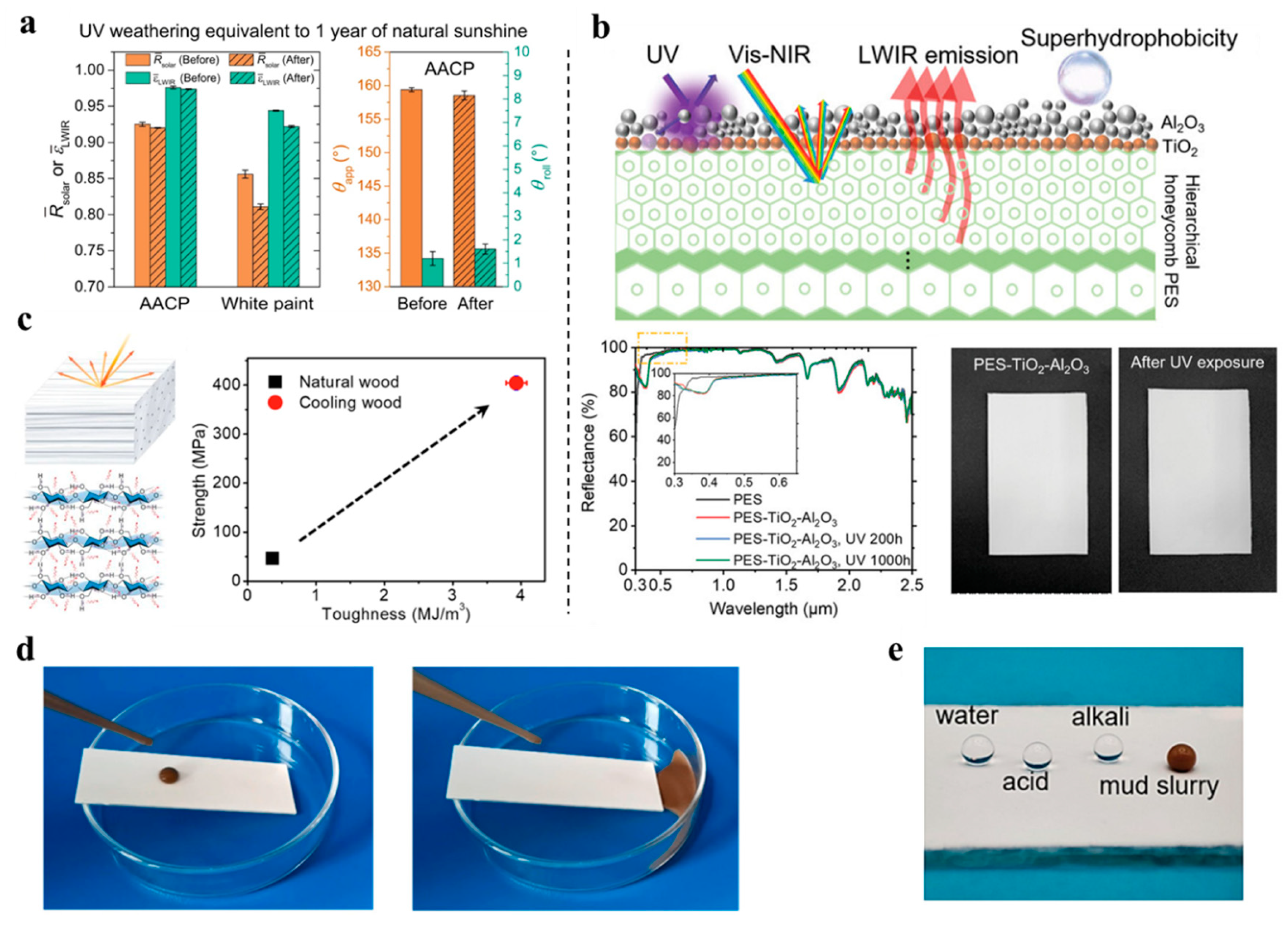

- Enhancement of Durability and Self-Cleaning Properties: The long-term performance of passive radiative coolers is mainly dependent on their ability to maintain their optical properties in the face of environmental challenges, such as pollutant deposition and chemical contamination. Nano-engineered surfaces with self-cleaning properties, such as employing superhydrophobic or photocatalytic mechanisms, represent a promising avenue for research that could help to alleviate these concerns. Consequently, future studies could explore the potential of such surfaces to sustain high levels of solar reflectivity and MIR emissivity after extended outdoor exposure. Moreover, conducting comprehensive sustainability assessments on the lifecycle of radiative cooling materials is crucial. This ensures the environmental footprint of passive radiative cooling technologies is thoroughly understood and minimized. Research directed towards understanding how these materials interact with a wide array of environmental stressors will be invaluable in determining the long-term stability and suitability of radiative coolers for large-scale implementation.

- Adaptive Cooling Power Modulation: The static nature of traditional passive radiative cooling technologies does not accommodate the dynamic cooling demand imposed by diurnal and seasonal temperature variations, nor does it account for the diverse climatic conditions across different geographical regions. The integration of adaptive mechanisms, capable of modulating radiative cooling power, is therefore a significant research frontier. Materials with tunable emissivity, such as thermochromic, shape-memory, and phase-change materials, offer promising pathways for achieving adaptive cooling capabilities. Research should delve into the synthesis and characterization of these materials to lower their transition temperatures and enhance their responsiveness. Additionally, the incorporation of smart control systems that automate the adjustment of radiative cooling power based on real-time feedback of ambient conditions represents an interdisciplinary challenge with vast implications for energy conservation and thermal comfort of users.

- Scalability and Manufacturing Research: Transitioning passive radiative cooling technologies from prototype to large-scale production is an essential research focus. Future work should concentrate on refining manufacturing processes to enhance the scalability of passive radiative coolers. Roll-to-roll fabrication and modular design are promising methods that could facilitate mass production, improving consistency and reducing costs. Additionally, developing methodologies for standardized quality control will be vital to ensure the reliability and performance of radiative coolers at scale. Addressing these manufacturing challenges is the key to enabling the commercial adoption of passive radiative cooling technologies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, J. Y.; Han, D. L.; Li, Z. C.; Yang, L.; Lu, S. G.; Zhong, Z. F.; Chen, J. P.; Zhang, Q. M.; Qian, X. S. , Electrocaloric Cooling Materials and Devices for Zero-Global-Warming-Potential, High-Efficiency Refrigeration. Joule 2019, 3 (5), 1200–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, C. H.; Duarte, W. M.; Rocha, T. T. M.; de Oliveira, R. N.; de Paoli Mendes, R.; Maia, A. A. T. , Thermo-economic and environmental analysis of a small capacity vapor compression refrigeration system using R290, R1234yf, and R600a. International Journal of Refrigeration 2020, 118, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, P.; Elmegaard, B.; Cortella, G., Energy and environmental performance assessment of R744 booster supermarket refrigeration systems operating in warm climates. International Journal of Refrigeration-Revue Internationale Du Froid 2016, 64, 61-79.

- Abas, N.; Kalair, A. R.; Khan, N.; Haider, A.; Saleem, Z.; Saleem, M. S. , Natural and synthetic refrigerants, global warming: A review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2018, 90, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumma, N.; Kruthiventi, S. S. H. , Current status of refrigerants used in domestic applications: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 114073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. M.; Gu, M. , Radiative Cooling: Principles, Progress, and Potentials. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2016, 3 (7), 1500360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalanotti, S.; Cuomo, V.; Piro, G.; Ruggi, D.; Silvestrini, V.; Troise, G. J. S. E. , The radiative cooling of selective surfaces. Solar Energy 1975, 17 (2), 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotti, S.; Cuomo, V.; Piro, G.; Ruggi, D.; Silvestrini, V.; Troise, G. , The radiative cooling of selective surfaces. Solar Energy 1975, 17 (2), 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, C. G.; Hjortsberg, A. , Radiative Cooling to Low-Temperatures - General-Considerations and Application to Selectively Emitting Sio Films. Journal of Applied Physics 1981, 52 (6), 4205–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A. P.; Anoma, M. A.; Zhu, L.; Rephaeli, E.; Fan, S. , Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature 2014, 515 (7528), 540–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, W.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, J. , Recent Progress in Daytime Radiative Cooling: Advanced Material Designs and Applications. Small Methods 2022, 6 (4), e2101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiganyanun, S.; Plumley, J. B.; Han, S. J.; Hsu, K.; Cytrynbaum, J.; Peng, T. L.; Han, S. M.; Han, S. E. , Effective Radiative Cooling by Paint-Format Microsphere-Based Photonic Random Media. ACS Photonics 2018, 5 (4), 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Kim, M.; Jung, P. H.; Son, S.; Seo, J.; Liu, Y.; Lee, B. J.; Lee, H. , Spectrally Selective Inorganic-Based Multilayer Emitter for Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12 (7), 8073–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, L.; Raman, A.; Fan, S. , Radiative cooling to deep sub-freezing temperatures through a 24-h day-night cycle. Nat Commun 2016, 7 (1), 13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Okada, K.; Jinno, K.; Ota, T. , Fabrication of radiative cooling devices using Si<sub>2</sub>N<sub>2</sub>O nano-particles. Journal of the Ceramic Society of Japan 2016, 124 (11), 1185–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Berdahl, P. , Radiative cooling with MgO and/or LiF layers. Appl Opt 1984, 23 (3), 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Lei, Z. Y.; Wu, K.; Chen, Y. P. , Reconfigurable and Renewable Nano-Micro-Structured Plastics for Radiative Cooling. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31 (21), 2100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili, A.; Wei, Z. Y.; Chen, Y. Z.; Zhao, D. L.; Yang, R. G.; Yin, X. B. , Selection of polymers with functional groups for daytime radiative cooling. Materials Today Physics 2019, 10, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, J.; Deng, X.; Cui, J. , Switchable Cavitation in Silicone Coatings for Energy-Saving Cooling and Heating. Adv Mater 2020, 32 (29), e2000870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R. Y. M.; Tso, C. Y.; Fu, S.; Chao, C. Y. H. , Maxwell-Garnett permittivity optimized micro-porous PVDF/PMMA blend for near unity thermal emission through the atmospheric window. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2022, 248, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. B.; Geng, J. L.; Tan, X. Y.; Liu, M.; Yao, S. M.; Tu, Y. T.; Li, S. S.; Qiao, Y. L.; Qi, G. G.; Xu, R. Z.; Nie, S. J. , A flexible PDMS@ZrO film for highly efficient passive radiative cooling. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 151, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H. T.; Fan, D. S.; Li, Q. , Scalable and paint-format colored coatings for passive radiative cooling. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2022, 245, 111853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, Y.; Shi, L.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, L. , A structural polymer for highly efficient all-day passive radiative cooling. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. Y.; Tso, C. Y.; Ha, J.; Wong, Y. M.; Chao, C. Y. H.; Huang, B. L.; Qiu, H. H. , Field investigation of a photonic multi-layered TiO passive radiative cooler in sub-tropical climate. Renewable Energy 2020, 146, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A. W.; Walton, M. R. , Radiative Cooling of Tio2 White Paint. Solar Energy 1978, 20 (2), 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, N. F.; Raman, A. P. , Paints as a Scalable and Effective Radiative Cooling Technology for Buildings. Joule 2020, 4 (7), 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Son, S.; Lim, H.; Jung, P.-H.; Ha, J.; Lee, H. , Scalable and paint-format microparticle–polymer composite enabling high-performance daytime radiative cooling. Materials Today Physics 2021, 18, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Peoples, J.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Bao, H.; Ruan, X. , Electronic and phononic origins of BaSO as an ultra-efficient radiative cooling paint pigment. Materials Today Physics 2022, 24, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peoples, J.; Yao, P.; Ruan, X. , Ultrawhite BaSO(4) Paints and Films for Remarkable Daytime Subambient Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13 (18), 21733–21739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A. S.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Y. F.; Gulfam, R. , Emerging radiative materials and prospective applications of radiative sky cooling - A review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2021, 144, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, T. M.; Niklasson, G. A.; Granqvist, C. G. , A solar reflecting material for radiative cooling applications: ZnS pigmented polyethylene. Solar Energy materials and Solar cells 1992, 28 (2), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, M. Z.; Fan, D. S. , Core-shell particles for devising high-performance full-day radiative cooling paint. Applied Materials Today 2021, 25, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J. P.; Tang, M. Z.; Quan, R. H.; Chai, Z. Y. , Synthesis of solar heat-reflective ZnTiO pigments with novel roof cooling effect. Ceramics International 2019, 45 (12), 15768–15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-F., Novel materials and concepts for regulating infra-red radiation: radiative cooling and cool paint. In Energy Saving Coating Materials, Elsevier: 2020; pp 113-131.

- Howell, J. R.; Mengüç, M. P.; Daun, K.; Siegel, R. , Thermal radiation heat transfer. CRC press: 2020.

- Zevenhoven, R.; Fält, M. , Radiative cooling through the atmospheric window: A third, less intrusive geoengineering approach. Energy 2018, 152, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, L.; Tenorio, J. A.; Revuelta, D.; Navarro, L.; Cabeza, L. F. , Developing a PCM-enhanced mortar for thermally active precast walls. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 181, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, P.; Wang, H. L.; Yang, T.; Hou, J. , Cooling potential and applications prospects of passive radiative cooling in buildings: The current state-of-the-art. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2016, 65, 1079–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, C.; Dennis, B. J. H. s. w. t. m. f. t. c., The Washington Post, The world is about to install 700 million air conditioners. 2016.

- Xu, L.; Shen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L. , Superhydrophobic and Ultraviolet-Blocking Cotton Fabrics Based on TiO(2)/SiO(2) Composite Nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2018, 18 (10), 6879–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Pan, M.; Tian, F.; Li, X.; Ye, M.; Deng, X. , Durable radiative cooling against environmental aging. Nat Commun 2022, 13 (1), 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Lin, C.; Li, K.; Ma, W.; Dopphoopha, B.; Li, Y.; Huang, B. , A UV-Reflective Organic-Inorganic Tandem Structure for Efficient and Durable Daytime Radiative Cooling in Harsh Climates. Small 2023, 19 (29), e2301159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhai, Y.; He, S.; Gan, W.; Wei, Z.; Heidarinejad, M.; Dalgo, D.; Mi, R.; Zhao, X.; Song, J.; Dai, J.; Chen, C.; Aili, A.; Vellore, A.; Martini, A.; Yang, R.; Srebric, J.; Yin, X.; Hu, L. , A radiative cooling structural material. Science 2019, 364 (6442), 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. D.; Xue, C. H.; Ji, Z. Y.; Huang, M. C.; Jiang, Z. H.; Liu, B. Y.; Deng, F. Q.; An, Q. F.; Guo, X. J. , Superhydrophobic Porous Coating of Polymer Composite for Scalable and Durable Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022, 14 (45), 51307–51317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, Z. C.; Qian, C. L.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. M. , Durable and mechanically robust superhydrophobic radiative cooling coating. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 478, 147341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mandal, J.; Li, W.; Smith-Washington, A.; Tsai, C. C.; Huang, W.; Shrestha, S.; Yu, N.; Han, R. P. S.; Cao, A.; Yang, Y. , Colored and paintable bilayer coatings with high solar-infrared reflectance for efficient cooling. Sci Adv 2020, 6 (17), eaaz5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Guan, F. Q.; Chen, F. H.; Chen, M. X.; Fang, Z. G.; Lu, C. H.; Xu, Z. Z. , Construction of colorful super-omniphobic emitters for high-efficiency passive radiative cooling. Composites Communications 2021, 28, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wan, R.; Xu, W.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, X.; Yang, R.; Yin, X. , Colored radiative cooling coatings using phosphor dyes. Materials Today Nano 2022, 19, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Liu, Y. D.; Zhao, W. X.; Hu, R.; Luo, X. B. , Colored radiative cooling: How to balance color display and radiative cooling performance. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2021, 170, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasarao, M. , Nano-Optics in the Biological World: Beetles, Butterflies, Birds, and Moths. Chem Rev 1999, 99 (7), 1935–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, K.; Kim, Y.; Mohd-Noor, S.; Hyun, J. K. , Mie Resonant Structural Colors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12 (5), 5300–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçın, R. A.; Blandre, E.; Joulain, K.; Drévillon, J. , Colored radiative cooling coatings with nanoparticles. ACS photonics 2020, 7 (5), 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Ma, R. , Photonic-Structure Colored Radiative Coolers for Daytime Subambient Cooling. Nano Lett 2022, 22 (12), 4925–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Droguet, B.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Parton, T. G.; Shan, X.; Parker, R. M.; De Volder, M. F. L.; Deng, T.; Vignolini, S.; Li, T. , Structurally Colored Radiative Cooling Cellulosic Films. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022, 9 (26), e2202061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xiao, P.; Li, S.; Deng, F.; Ni, F.; Zhang, C.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Kuo, S. W.; Geng, F.; Chen, T. , Engineering Structural Janus MXene-nanofibrils Aerogels for Season-Adaptive Radiative Thermal Regulation. Small 2023, e2302509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, B.; Sui, C.; Nandi, A.; Fang, H.; Peng, Y.; Tan, G.; Hsu, P. C. , Integration of daytime radiative cooling and solar heating for year-round energy saving in buildings. Nat Commun 2020, 11 (1), 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M.; Chen, K.; Li, W.; Fan, S. , Self-adaptive radiative cooling based on phase change materials. Opt Express 2018, 26 (18), A777–A787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Dong, K.; Li, J.; Gordon, M. P.; Reichertz, F. G.; Kim, H.; Rho, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lin, C. Y.; Grigoropoulos, C. P.; Javey, A.; Urban, J. J.; Yao, J.; Levinson, R.; Wu, J. , Temperature-adaptive radiative coating for all-season household thermal regulation. Science 2021, 374 (6574), 1504–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K. K.; Li, Q.; Lyu, Y. B.; Ding, J. C.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, Z. Y.; Qiu, M. , Control over emissivity of zero-static-power thermal emitters based on phase-changing material GST. Light Sci Appl 2017, 6 (1), e16194. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Luo, H.; Zhu, H.; Hong, Y.; Shen, W.; Ding, J.; Kaur, S.; Ghosh, P.; Qiu, M.; Li, Q. , Nonvolatile Optically Reconfigurable Radiative Metasurface with Visible Tunability for Anticounterfeiting. Nano Lett 2021, 21 (12), 5269–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahramezani, S.; Hemmatyar, O.; Taghinejad, H.; Krasnok, A.; Kiarashinejad, Y.; Zandehshahvar, M.; Alù, A.; Adibi, A. , Tunable nanophotonics enabled by chalcogenide phase-change materials. Nanophotonics 2020, 9 (5), 1189–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, S.; Ohnishi, A.; Okamoto, A.; Nakamura, Y. , Development of a variable emittance radiator based on a perovskite manganese oxide. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2003, 17 (2), 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, D. S.; Li, Q., Flexible perovskite-based photonic stack device for adaptive thermal management. Materials & Design 2022, 219, 110719.

- Granqvist, C. G. , Recent progress in thermochromics and electrochromics: A brief survey. Thin Solid Films 2016, 614, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, M.; An, Y. Z.; Tao, Y. J.; Sun, J. Y.; Ji, C. , All-season thermal regulation with thermochromic temperature-adaptive radiative cooling coatings. Sol Energ Mat Sol C 2022, 246, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. A.; Chen, M.; Gu, M.; Wu, L. M., Scalable and waterborne titanium-dioxide-free thermochromic coatings for self-adaptive passive radiative cooling and heating. Cell Reports Physical Science 2022, 3, (3).

- An, Y. D.; Fu, Y.; Dai, J. G.; Yin, X. B.; Lei, D. Y., Switchable radiative cooling technologies for smart thermal management. Cell Reports Physical Science 2022, 3, (10).

- Mei, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, M.; Wu, L. M. , A self-adaptive film for passive radiative cooling and solar heating regulation. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2022, 10 (20), 11092–11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastidar, S.; Alam, M. M.; Crispin, X.; Zhao, D.; Jonsson, M. P. , Janus cellulose for self-adaptive solar heating and evaporative drying. Cell Reports Physical Science 2022, 3 (12), 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Pian, S.; Su, M.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Cen, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, R.; Tunuhe, A.; Sun, X.; Xia, Z.; Tian, M.; Chen, M.; Ma, X.; Yang, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Tao, G. , Hierarchical-morphology metafabric for scalable passive daytime radiative cooling. Science 2021, 373 (6555), 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Catrysse, P. B.; Xu, W.; Fan, S.; Zhu, J. , Subambient daytime radiative cooling textile based on nanoprocessed silk. Nat Nanotechnol 2021, (12), 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P. C.; Li, X. , Photon-engineered radiative cooling textiles. Science 2020, 370 (6518), 784–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steketee, J. , Spectral emissivity of skin and pericardium. Phys Med Biol 1973, 18 (5), 686–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Song, A. Y.; Li, W.; Hsu, P. C.; Lin, D.; Catrysse, P. B.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Yang, A.; Fan, S.; Cui, Y. , Spectrally Selective Nanocomposite Textile for Outdoor Personal Cooling. Adv Mater 2018, 30 (35), e1802152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L. L.; Peng, Y. C.; Xu, J. W.; Zhou, C. Y.; Zhou, C. X.; Wu, P. L.; Lin, D. C.; Fan, S. H.; Cui, Y. , Temperature Regulation in Colored Infrared-Transparent Polyethylene Textiles. Joule 2019, 3 (6), 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P. C.; Song, A. Y.; Catrysse, P. B.; Liu, C.; Peng, Y.; Xie, J.; Fan, S.; Cui, Y. , Radiative human body cooling by nanoporous polyethylene textile. Science 2016, 353 (6303), 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Wang, X. W.; Yu, J. R.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. M. , A Novel Approach to Design Nanoporous Polyethylene/Polyester Composite Fabric via TIPS for Human Body Cooling. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2018, 303 (3), 1700456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. C.; Chen, J.; Song, A. Y.; Catrysse, P. B.; Hsu, P. C.; Cai, L. L.; Liu, B. F.; Zhu, Y. Y.; Zhou, G. M.; Wu, D. S.; Lee, H. R.; Fan, S. H.; Cui, Y. , Nanoporous polyethylene microfibres for large-scale radiative cooling fabric. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1 (2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-N.; Lei, M.-Q.; Lei, J.; Li, Z.-M. , Spectrally selective polyvinylidene fluoride textile for passive human body cooling. Materials Today Energy 2020, 18, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. N.; Li, Y.; Yan, D. X.; Lei, J.; Li, Z. M., Novel passive cooling composite textile for both outdoor and indoor personal thermal management. Composites Part a-Applied Science and Manufacturing 2020, 130, 105738.

- Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Shao, Z.; Li, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, C.; Wang, H. , A Moisture-Wicking Passive Radiative Cooling Hierarchical Metafabric. ACS Nano 2022, 16 (2), 2188–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberghini, M.; Hong, S.; Lozano, L. M.; Korolovych, V.; Huang, Y.; Signorato, F.; Zandavi, S. H.; Fucetola, C.; Uluturk, I.; Tolstorukov, M. Y.; Chen, G.; Asinari, P.; Osgood, R. M.; Fasano, M.; Boriskina, S. V. , Sustainable polyethylene fabrics with engineered moisture transport for passive cooling. Nature Sustainability 2021, 4 (8), 715–+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Wang, N.; Hou, L.; Liu, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y. , Bilayer Nanoporous Polyethylene Membrane with Anisotropic Wettability for Rapid Water Transportation/Evaporation and Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022, 14 (7), 9833–9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S. J.; Yi, L. M.; Zhang, J. W.; Xu, T. Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, T.; Cai, Y. , Self-cleaning and spectrally selective coating on cotton fabric for passive daytime radiative cooling. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 407, 127104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C. F.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S. Q.; Su, J. J.; Han, J. , Hierarchical-porous coating coupled with textile for passive daytime radiative cooling and self-cleaning. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2022, 247, 111954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P. C.; Liu, C.; Song, A. Y.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, K.; Wu, C. L.; Catrysse, P. B.; Cai, L.; Zhai, S.; Majumdar, A.; Fan, S.; Cui, Y. , A dual-mode textile for human body radiative heating and cooling. Sci Adv 2017, 3 (11), e1700895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, M. G.; De Corte, A.; Rosolen, G.; Maes, B. , Janus-Yarn Fabric for Dual-Mode Radiative Heat Management. Physical Review Applied 2021, 16 (5), 054013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. A.; Yu, S.; Xu, B.; Li, M.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z.; Ouyang, M.; Wang, Y. , Dynamic gating of infrared radiation in a textile. Science 2019, 363 (6427), 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, K.; Millar, D. L.; Smith, H. C. M. , Novel offshore application of photovoltaics in comparison to conventional marine renewable energy technologies. Renewable Energy 2013, 50, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, S. M.; Ran, N. A.; Bazan, G. C.; Friend, R. H. , Understanding Energy Loss in Organic Solar Cells: Toward a New Efficiency Regime. Joule 2018, 2 (1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otth, D. H.; Ross, R. In Assessing photovoltaic module degradation and lifetime from long term environmental tests, 29th Institute of Environmental Sciences Technical Meeting, Los Angeles, CA, 1983; 1983; pp 121-126.

- Radziemska, E. , The effect of temperature on the power drop in crystalline silicon solar cells. Renewable Energy 2003, 28 (1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoplaki, E.; Palyvos, J. A. , On the temperature dependence of photovoltaic module electrical performance: A review of efficiency/power correlations. Solar Energy 2009, 83 (5), 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentle, A.; Smith, G. , Is enhanced radiative cooling of solar cell modules worth pursuing? Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2016, 150, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. X.; Raman, A.; Wang, K. X.; Abou Anoma, M.; Fan, S. H. , Radiative cooling of solar cells. Optica 2014, 1 (1), 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. H.; Chen, Z. C.; Ai, L.; Zhang, X. P.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, W. Y.; Tan, R. Q.; Dai, N.; Song, W. J. , A Universal Route to Realize Radiative Cooling and Light Management in Photovoltaic Modules. Solar Rrl 2017, 1 (10), 1700084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Luo, T. F. , Black body-like radiative cooling for flexible thin-film solar cells. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2019, 194, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J. P.; Oliveira, P. B. D.; Cunha, J. B. , Greenhouse air temperature predictive control using the particle swarm optimisation algorithm. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2005, 49 (3), 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sanchez, J. A.; Velasco-Munoz, J. F.; Lopez-Felices, B.; Roman-Sanchez, I. M. , An Analysis of Global Research Trends on Greenhouse Technology: Towards a Sustainable Agriculture. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17 (2), 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddio, E.; Wang, L.; Thomas, Y.; McMorrow, G.; Denzer, A. , Energy efficient operation and modeling for greenhouses: A literature review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2020, 117, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y. H. , Evaluation of cooling property of high density polyethylene (HDPE)/titanium dioxide (TiO) composites after accelerated ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2015, 143, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. H.; Ay, C.; Tsai, C. Y.; Lee, M. T. , The Application of Passive Radiative Cooling in Greenhouses. Sustainability 2019, 11 (23), 6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Wang, C. X.; Yu, J. Q.; Huang, D. F.; Yang, R. G.; Wang, R. Z., Eliminating greenhouse heat stress with transparent radiative cooling film. Cell Reports Physical Science 2023, 4, (8).

- Tassou, S. A.; De-Lille, G.; Ge, Y. T., Food transport refrigeration - Approaches to reduce energy consumption and environmental impacts of road transport. Applied Thermal Engineering 2009, 29, (8-9), 1467-1477.

- Gemili, S.; Yemenicioglu, A.; Altinkaya, S. A. , Development of cellulose acetate based antimicrobial food packaging materials for controlled release of lysozyme. Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 90 (4), 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrez, D. A.; Abdelhamid, A. E.; Darwesh, O. M. , Eco-friendly cellulose acetate green synthesized silver nano-composite as antibacterial packaging system for food safety. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, D. M.; Mendonça, R. C. S.; Soto, M. L.; Cruz, R. S., Acetate cellulose film with bacteriophages for potential antimicrobial use in food packaging. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2015, 63, (1), 85-91.

- Li, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, N.; Zhu, B.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Fan, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J., Protecting ice from melting under sunlight via radiative cooling. Sci Adv 2022, 8, (6), eabj9756.

- Zhang, K.; Mo, C. Q.; Tang, X. L.; Lei, X. J., Hierarchically Porous Cellulose-Based Radiative Cooler for Zero-Energy Food Preservation. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, (20), 7745-7754.

- Chen, Y. N.; Wang, Z. Y.; Dai, Y. T.; Yang, D. Y.; Qiu, F. X.; Li, Y. Q.; Zhang, T., Green Food Packaging with Integrated Functions of High-Efficiency Radiation Cooling and Freshness Monitoring. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, (41), 15135-15145.

- Mishra, R. K. , Fresh water availability and its global challenge. British Journal of Multidisciplinary and Advanced Studies 2023, 4 (3), 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. C.; Thu, K.; Kim, Y.; Chakraborty, A.; Amy, G. , Adsorption desalination: An emerging low-cost thermal desalination method. Desalination 2013, 308, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, R. V.; Li, Z. Y.; Abu-Ghdaib, M.; Wei, C. H.; Amy, G.; Vrouwenvelder, J. S. , Water harvesting from municipal wastewater via osmotic gradient: An evaluation of process performance. Journal of Membrane Science 2013, 447, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, A.; Messalem, R., Solar-driven desalination with reverse osmosis: the state of the art. Desalination and Water Treatment 2009, 7, (1-3), 285-296.

- Tareemi, A. A.; Sharshir, S. W. , A state-of-art overview of multi-stage flash desalination and water treatment: Principles, challenges, and heat recovery in hybrid systems. Solar Energy 2023, 266, 112157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshrou, I.; Nasr, M. R. J.; Bakhtari, K. , New opportunities in mass and energy consumption of the Multi-Stage Flash Distillation type of brackish water desalination process. Solar Energy 2017, 153, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dessouky, H. T.; Ettouney, H. M.; Al-Roumi, Y. , Multi-stage flash desalination: present and future outlook. Chemical Engineering Journal 1999, 73 (2), 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A.; Ngo, H. H.; Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Chang, S. W.; Nguyen, D. D.; Nghiem, L. D.; Liang, H. , Can membrane bioreactor be a smart option for water treatment? Bioresource Technology Reports 2018, 4, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandin, G.; Verliefde, A. R.; Comas, J.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Le-Clech, P. , Efficiently combining water reuse and desalination through forward osmosis—reverse osmosis (FO-RO) hybrids: a critical review. Membranes 2016, 6 (3), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway, R. W.; Achilli, A.; Cath, T. Y., The osmotic membrane bioreactor: a critical review. Environmental Science-Water Research & Technology 2015, 1, (5), 581-605.

- Tu, Y. D.; Wang, R. Z.; Zhang, Y. N.; Wang, J. Y. , Progress and Expectation of Atmospheric Water Harvesting. Joule 2018, 2 (8), 1452–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejeian, M.; Wang, R. Z. , Adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting. Joule 2021, 5 (7), 1678–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, L. , The global atmospheric water cycle. Environmental Research Letters 2010, 5 (2), 025202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlgren, R. V. , Atmospheric water vapour processor designs for potable water production: a review. Water Res 2001, 35 (1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Song, H.; Xu, X.; Shahsafi, A.; Qu, Y.; Xia, Z.; Ma, Z.; Kats, M. A.; Zhu, J.; Ooi, B. S.; Gan, Q.; Yu, Z. , Vapor condensation with daytime radiative cooling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118 (14), e2019292118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haechler, I.; Park, H.; Schnoering, G.; Gulich, T.; Rohner, M.; Tripathy, A.; Milionis, A.; Schutzius, T. M.; Poulikakos, D. , Exploiting radiative cooling for uninterrupted 24-hour water harvesting from the atmosphere. Sci Adv 2021, 7 (26), eabf3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Yan, H.; Chen, M. , All-Day Freshwater Harvesting by Selective Solar Absorption and Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022, 14 (22), 26255–26263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, C.; Huang, J.; Chi, C.; Huang, B. , Spectrally Selective Absorbers/Emitters for Solar Steam Generation and Radiative Cooling-Enabled Atmospheric Water Harvesting. Glob Chall 2021, 5 (1), 2000058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, M.; Wang, C. , Passive interfacial photothermal evaporation and sky radiative cooling assisted all-day freshwater harvesting: System design, experiment study, and performance evaluation. Applied Energy 2024, 355, 122254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, B.; Song, C.; Shang, W.; Tao, P.; Deng, T. , All-Day Freshwater Harvesting through Combined Solar-Driven Interfacial Desalination and Passive Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12 (42), 47612–47622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).