Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

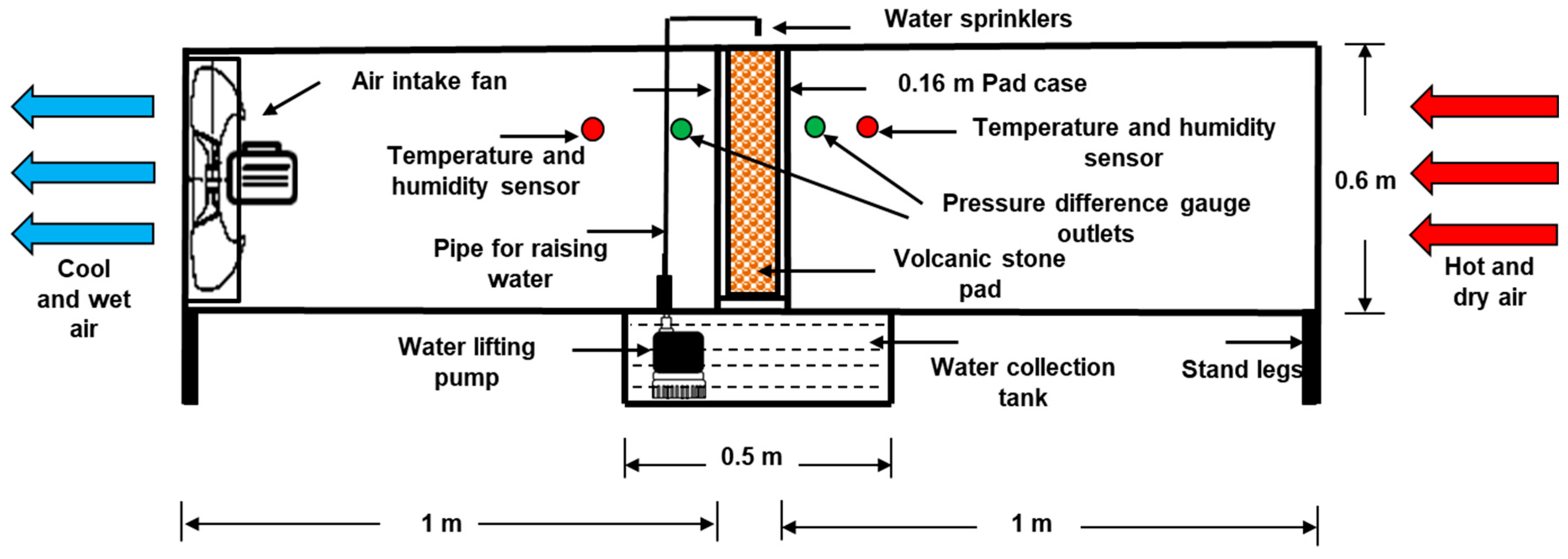

2.1. Evaporative Cooling System and Study Area

2.2. Volcanic Stone Cooling Pads

2.3. Experiment Planning

4. Results and Discussion

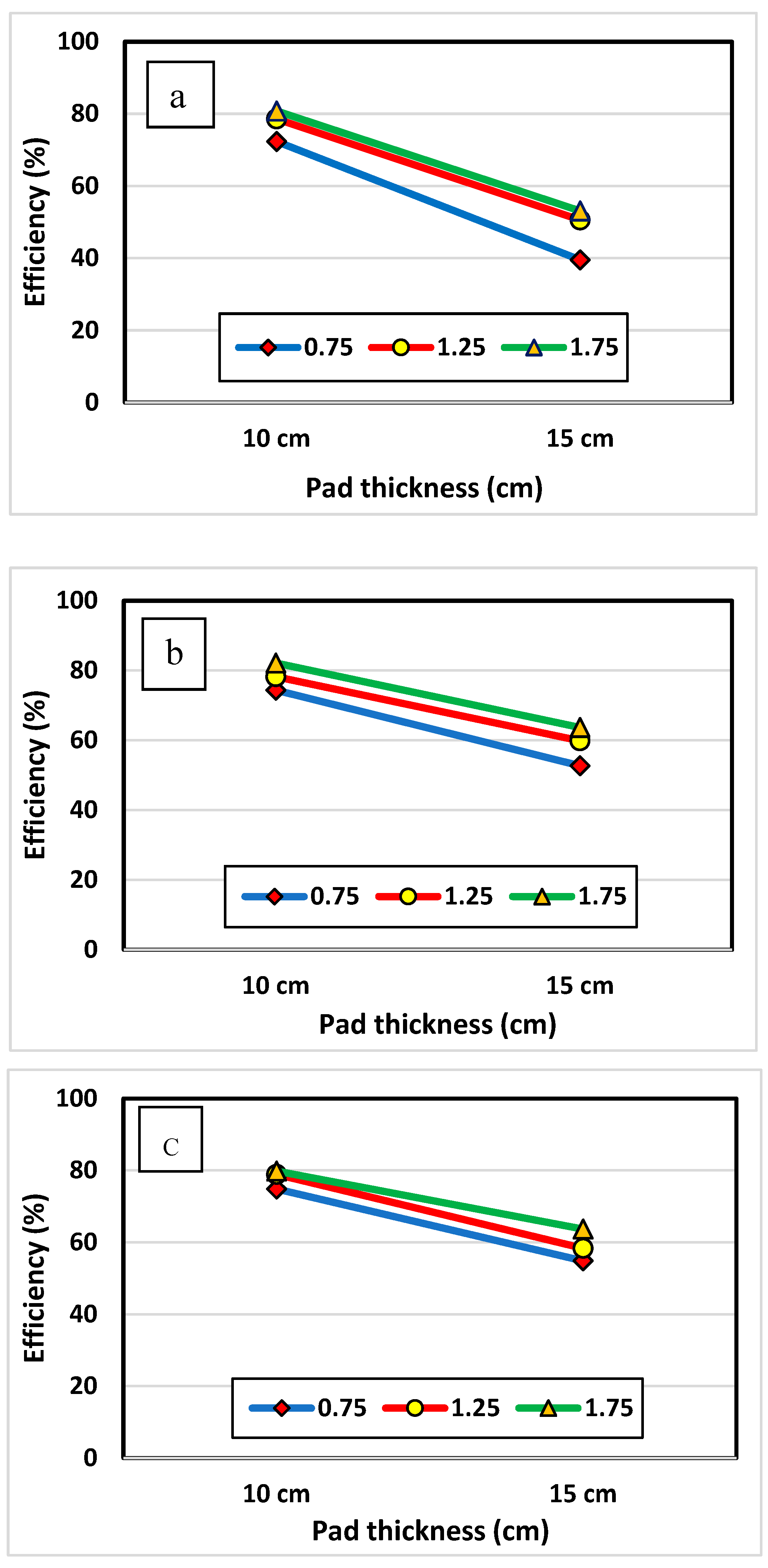

4.1. Effect of Pad Thickness on Cooling Efficiency

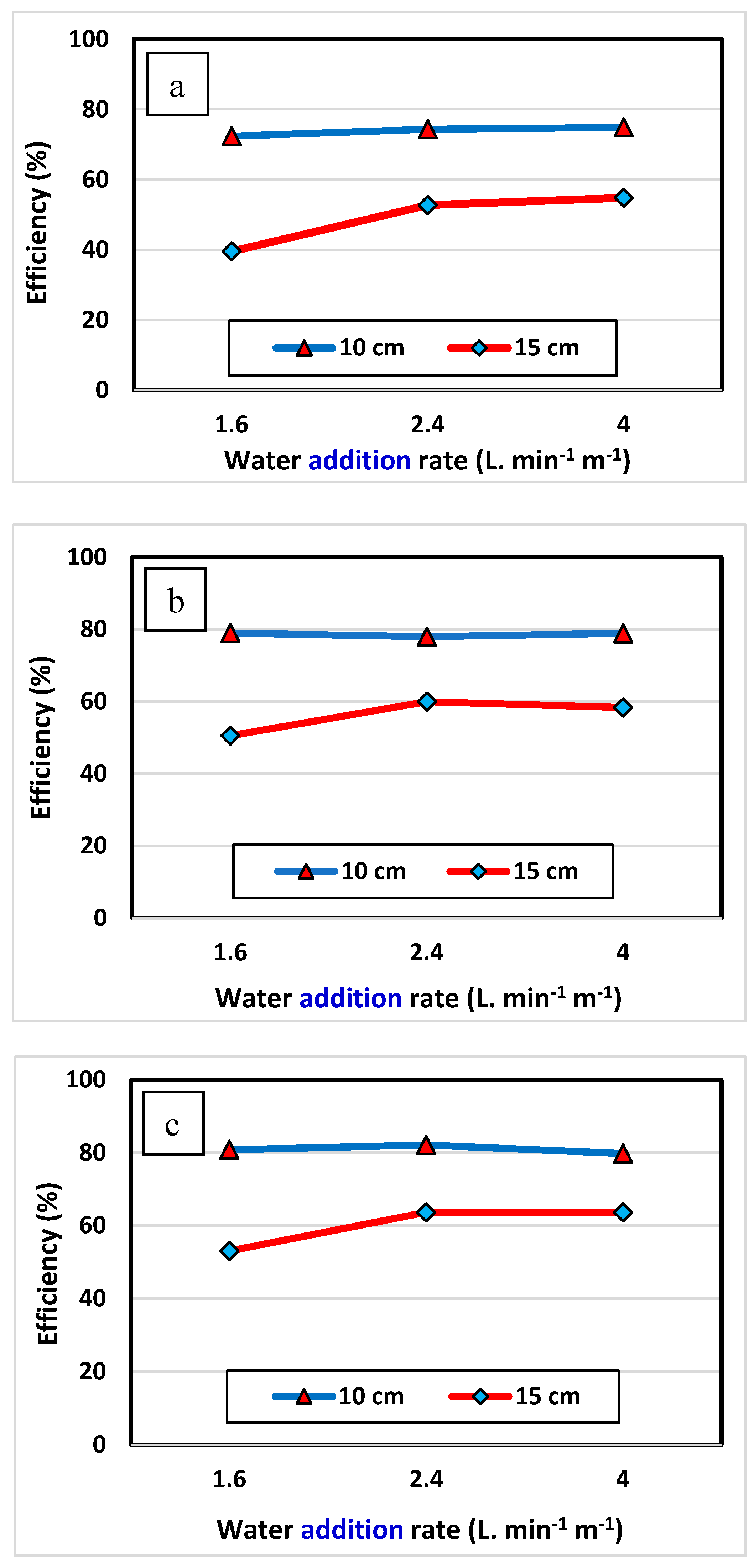

4.2. Effect of Water Addition Rate on Cooling Efficiency

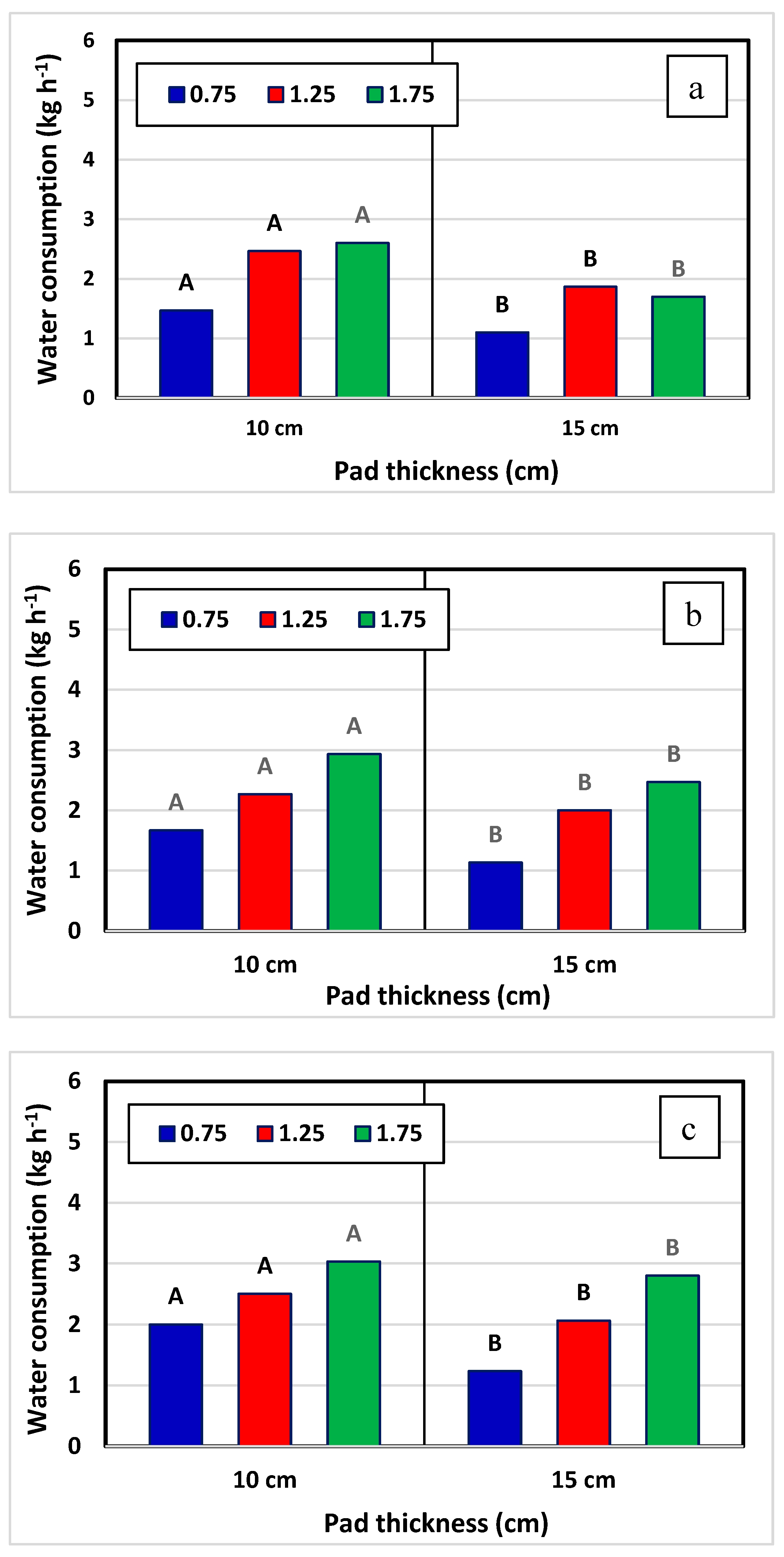

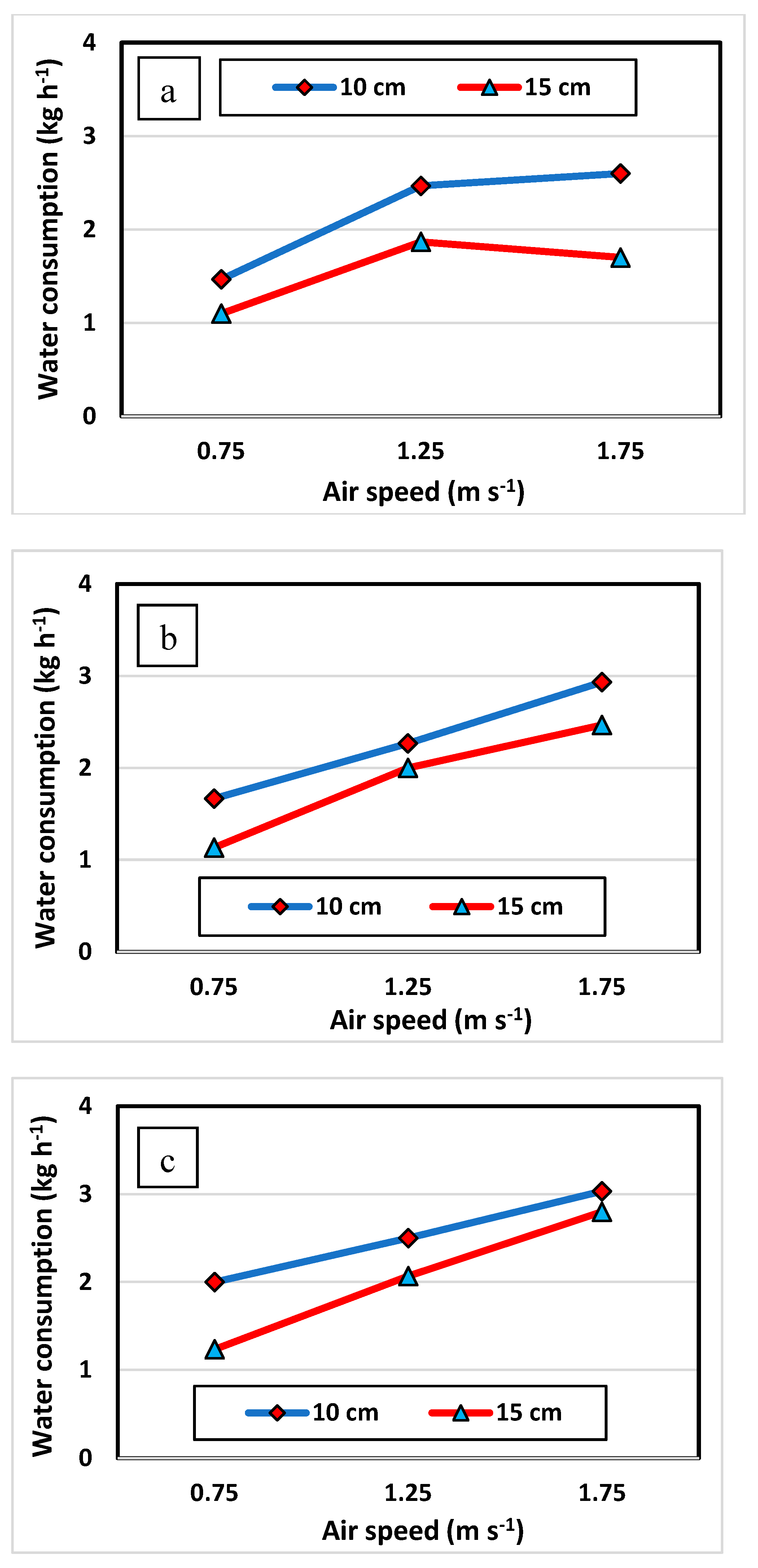

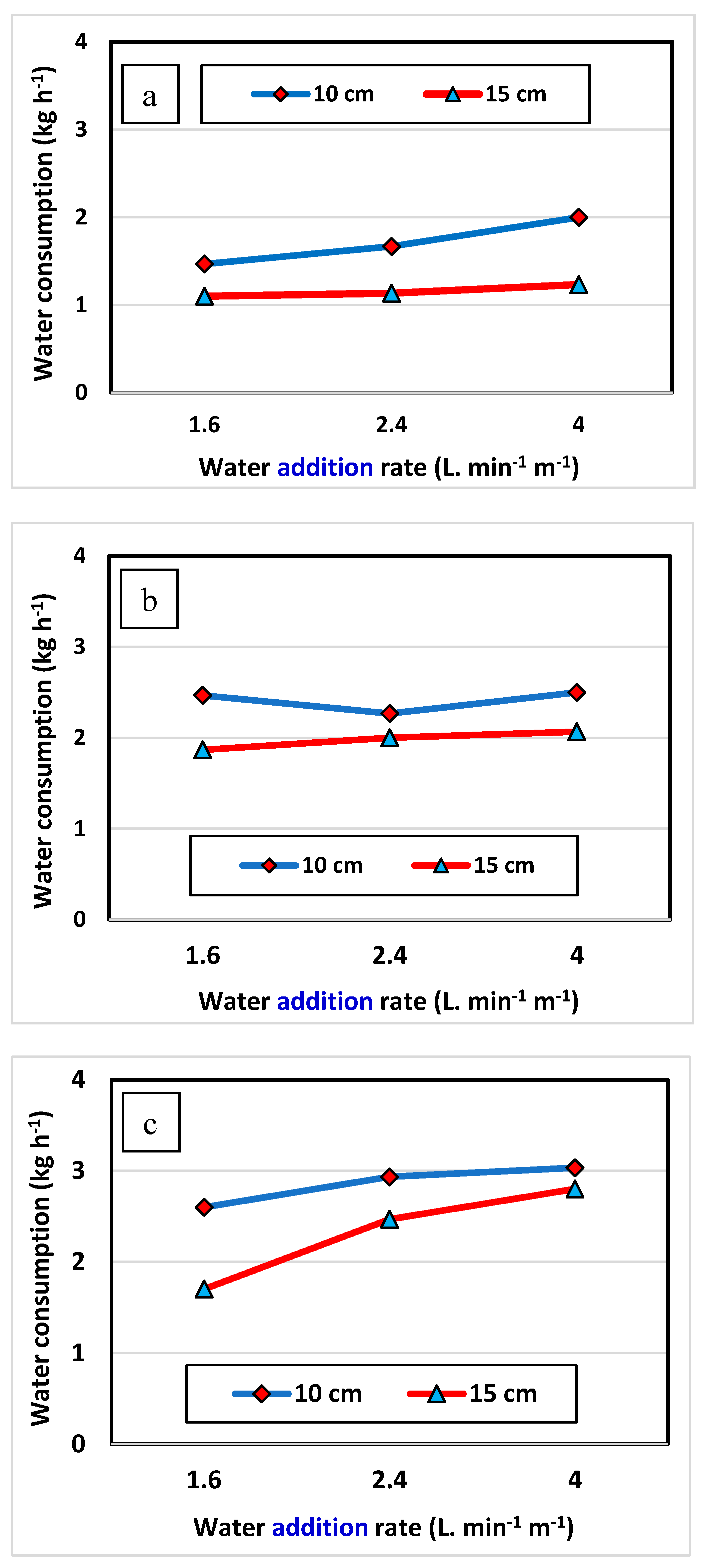

4.3. Effect of Pad Thickness on Water Consumption

4.4. Effect of Air Speed on Water Consumption

4.5. Effect of Water Addition Rate on Water Consumption

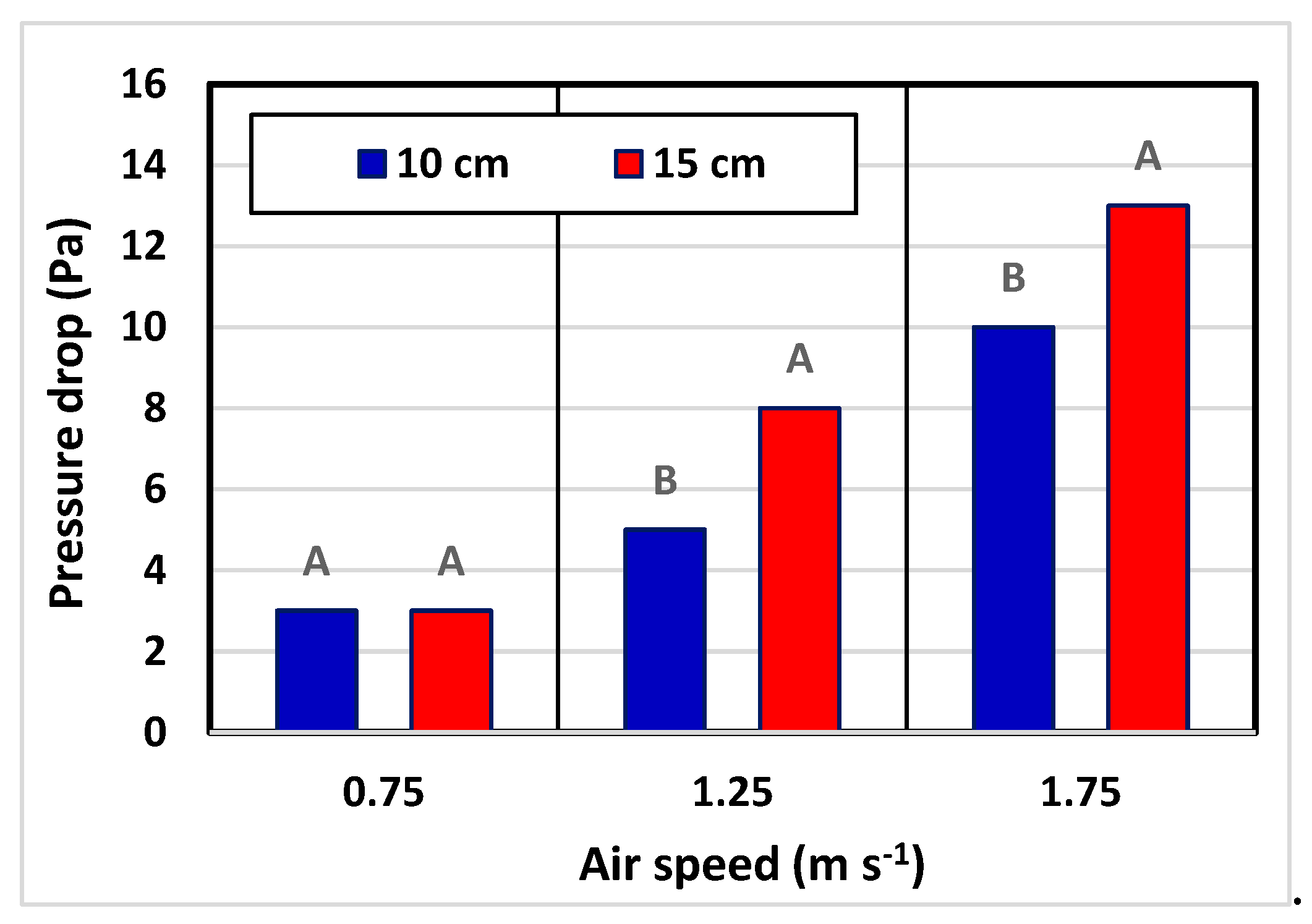

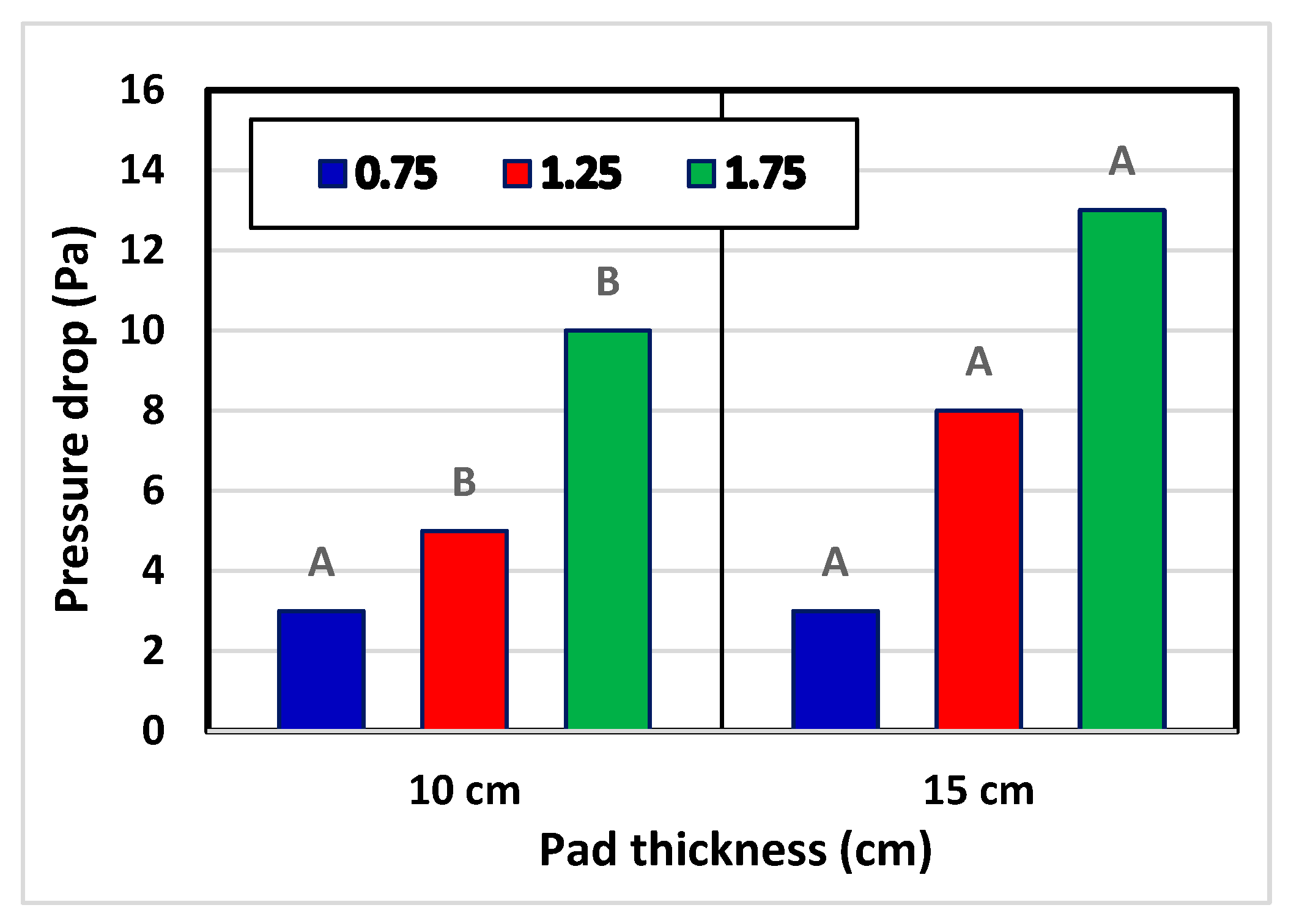

4.6. Effect of Pad Thickness on the Pressure Drop on Both Sides of the Pad

4.7. Effect of Air Speed on the Pressure Drop on Both Sides of the Pad

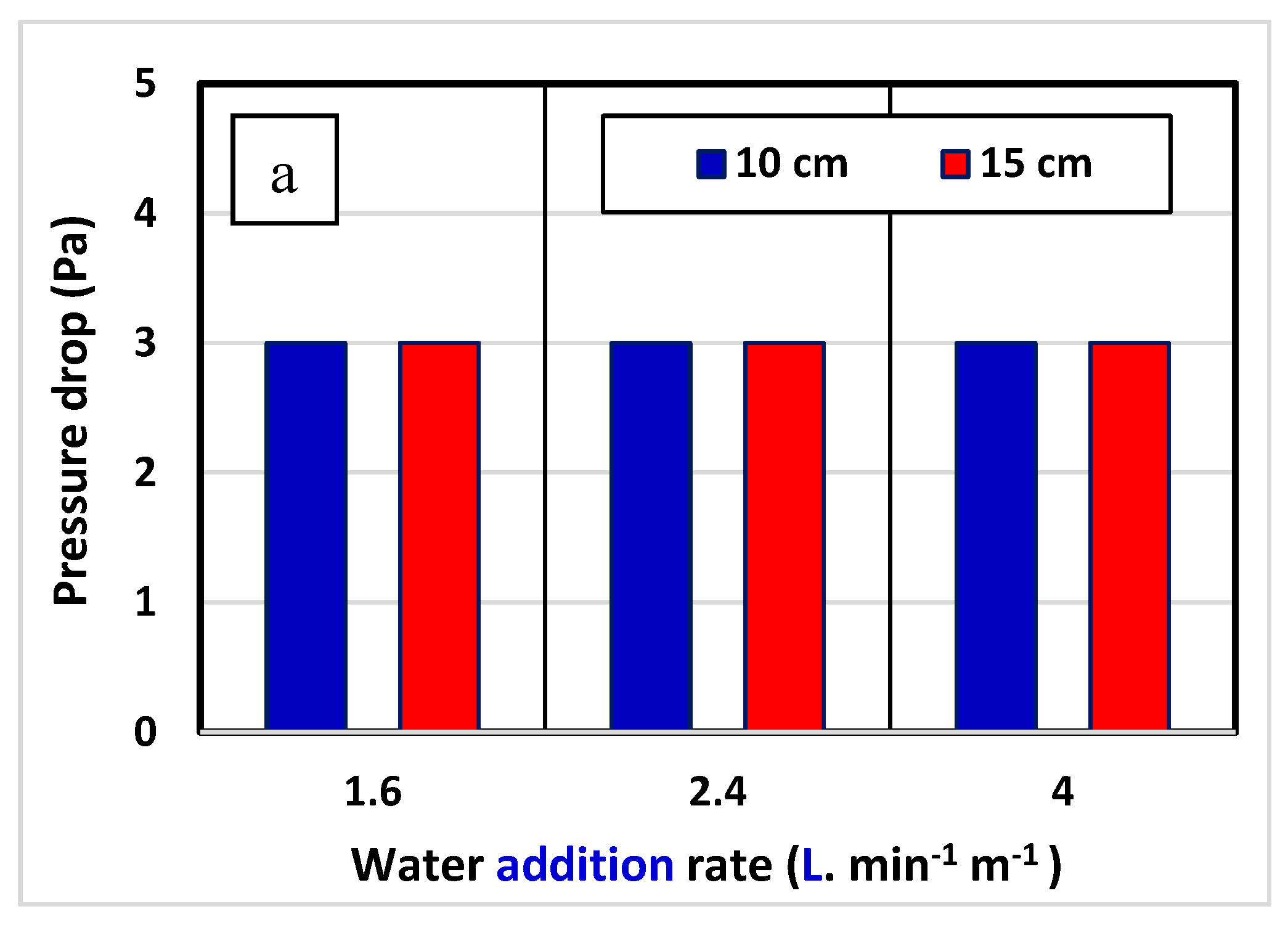

4.8. Effect of Water Adding Rate on the Pressure Drop on Both Sides of the Pad

4.9. Comparison Between Cooling Efficiency of Volcanic Stone Pads and Commercial Cellulosic Pads

| Pad type | Air speed (m s-1) |

Water addition rate (kg min-1 m-1) |

Pad thick. (cm) | Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volcanic stone | 1.75 | 2.4 | 10 | 82 | Current study |

| Cellulose pad | - | - | 7 | 64.38 | [9] |

| CELdek pad | 0.6 | - | 15 | 78 | [28] |

| CELdek pad | 1 | - | 10 | 68 | [28] |

| Cellulose pad | 1.27 | - | 10 | 70 | [33] |

| Cellulose pad | 1.4 | - | 10 | 75 | [34] |

| Cross – fluted Cellulose pad | 1.25 | 11 | 10 | 77 | [35] |

| Cellulose pad | 1 | 4 | 10 | 91 | [36] |

| Cellulose pad | 1.5 | 4 | 10 | 78 | [36] |

| Cellulose pad | 0.5 | - | 10 | 71 | [37] |

| CELdek pad | 1.3 2.7 |

3.6 | 10 | 67.73 65.57 |

[38] |

| Cellulose pad | 0.5 | - | 10 | 76 | [39] |

| CELdek pad | 1.75 | - | 30 | 75.6 | [40] |

| CELdek pad | 0.5-1.5 | 4 | 10 | 77-92 | [41] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghany, A. M., Al-Helal, I. M., Alzahrani, S. M., Alsadon, A. A., Ali, I. M., and Elleithy, R. M. 2012. Covering materials incorporating radiation-preventing techniques to meet greenhouse-cooling challenges in arid regions: a review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012(1-2): 906360. [CrossRef]

- Bucklin, R. A., J. D. Leary, D. B. McConnell, and E. G. Wilkerson, 2004. Fan and Pad Greenhouse Evaporative Cooling Systems (CIR1135, IFAS Extension, University of Florida) pp. 1-7.

- Bhatia, B. E. 2012. Instructor, PDH online Course M231 (4 PDH), “Principles of Evaporative Cooling System, 2012” pp. 1-56.

- Dzivama A.U., Bindir U. B. Aboaba F.O., 1999. Evaluation of pad materials in construction of active evaporative cooler for storage of fruits and vegetables in arid environments‖. Agricultural Mechanization in Asia, Africa and Latin America, AMA, Vol. 30(3), 51–55.

- Manoj Kumar Chopra, and Rahul Kumar, 2017. Design of New Evaporative Cooler and Usage of Different Cooling Pad Materials for Improved Cooling Efficiency, International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), Vol.04 (09) pp. 503-511.

- Kapilan N., Arun M. Isloor, Shashikantha Karinka. 2023. A comprehensive review on evaporative cooling systems. Results in Engineering, Vol 18, June 2023, 101059. [CrossRef]

- Edward A. Awafoa, Samuel Nketsiah, Mumin Alhassan, Ebenezer Appiah–Kubi, 2020. Design, construction, and performance evaluation of an evaporative cooling system for tomatoes storage, Agric. Eng. 24 (2020) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Akram, W. and Badholiya, S.K. 2024. Performance Analysis of Direct Evaporative Coolers Using Various Cooling Pad Materials: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews Vol (5 ) Issue ( 6) (2024) Page 5947-5954.

- Bucklin, R. A., Henley, R. W., and McConnell, D. B. 1993. Fan and pad greenhouse evaporative cooling systems. Circular (Florida Cooperative Extension Service) (USA). ISSN 0099-7676.

- Md. Ferdous, A., Ahmad, S., Asif, K., Gowtam, M., Nazmul, A. and Rahman, D. 2017. An Experimental Study on the Design, Performance and Suitability of Evaporative Cooling System using Different Indigenous Materials. 7th BSME International Conference on Thermal Engineering AIP Conf. Proc. 1851, 020075-1–020075-6. [CrossRef]

- Jain, J. K., and D.A. Hindoliya 2012. Development and Testing of Regenerative Evaporative Cooler. International J. of Engineering Trends and Technology, Vol 3 (6) pp. 694-697.

- Tinoco, I. D., Figueiredo, J. L., Santos, R. C., da Silva, J. N., Yanagi, T., de Paula, M. O., and Corderio, M. B. 2001. Comparison of the cooling effect of different materials used in evaporative pads. J. of Modern Manufacturing Systems and Technology, 1(1):61-68. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. M., and Chiu, K. H. 2002. Wind tunnel modeling the system performance of alternative evaporative cooling pads in Taiwan region. Building and environment, 37(2), pp. 177-187. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulaiman, F. 2002. Evaluation of the performance of local fibers in evaporative cooling. Energy conversion and management, 43(16), 2267-2273. [CrossRef]

- Kapish, T. D., Dharme M. R. and Gawande K. R. 2017. An Experimental Analysis of Direct evaporative Cooler by Varying materials of Cooling Pad. International J. of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development (IJMPERD), Vol. 7, Issue 6, pp. 585-590.

- Tejero-González, A., and Franco-Salas, A. 2021. Optimal operation of evaporative cooling pads: A review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 151, 111632. [CrossRef]

- Lefers, R., Davies, P.A. and Almadhoun N. 2018. Proof of Concept: Pozzolan Bricks for Saline Water Evaporative Cooling in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 34(6):929-937. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M. K., Al Turkey, A., and Al Zahrani, A. 2002. Water efficient irrigation method for horticulture in arid region. Water Resources Development and Management. 369-375.

- Fares, G. A. Alhozaimy, A. Al-Negheimish and O. A. Alawad. 2022. Characterization of scoria rock from Arabian lava fields as natural pozzolan for use in concrete, European J. of Environmental and Civil Engineering. 26:1, pp. 39-57. [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, M. S., Fares, G., and Ghrefat, H. A. (2019). Estimation of pozzolanic activity of scoria rocks using ASTER remote sensing. J. of Materials in Civil Engineering, 31(7), 04019100. [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar HS, Madhwesh N, Shankar Shenoy and Shiva Kumar. 2024. Performance evaluation of an indirect-direct evaporative cooler using biomass-based packing material. International J. of Sustainable Eng., 17:1, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Steel, R. G. D., and J. H. Torrie. 1980. Principles and procedures of statistics: A biometrical approach. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Wiersma, F and Benham, D. S. 1974. Design criteria for evaporative cooling. ASAE Paper No. 74-4527, ASAE, St. Joseph. MI 49085.

- Watt, John, R. 1953. Investigation Evaporative cooling. Report U.S. Naval civil Engineering Research and Evaluation Laboratory.

- He, S.; Guan, Z.; Gurgenci, H.; Hooman, K.; Alkhedhair, A.M. 2014. Experimental study of heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop of cellulose corrugated media. In Proceedings of the 19th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, Melbourne, Australia; pp. 8–11.

- Jawad, Salah Karim, and Imad Siddig Muhammad 2009. A study of the effect of changing some factors affecting the thermal performance of an evaporative air cooler. Iraqi J. of Mechanics and Engineering Materials. Volume (9) No. (2), pages 249-264.

- Gunhan, T., Demir, V., and Yagcioglu, A. 2007. Evaluation of the suitability of some local materials as cooling pads. Biosystems engineering, 96(3), pp. 369-377. [CrossRef]

- Al-Badri, A. R., and Al-Waaly, A. A. 2017. The influence of chilled water on the performance of direct evaporative cooling. J. of Energy and Buildings, 155, 143-150. [CrossRef]

- Ghoname, M. S., (2020). Effect of pad water flow rate on evaporative cooling system efficiency in laying hen housing. J. of Agricultural Engineering, vol LI: 1051. pp. 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M., He, S., Li, N., Huang, X., Gao, M., and Xu, M. 2020. Experimental investigation on a novel arrangement of wet medium for evaporative cooling of air. International Journal of Refrig., 2020:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Al-Helal and Al-Tuwaijri, 2001. Evaporative Cooling Efficiency of Palm Leaf Pads and Paper Pads with Cross Grooves under Dry Climate Conditions, Egyptian J. of Agricultural Engineering, 18(2), 469-483.

- Antonio Franco, Diego L. Valera and Araceli Peña. 2014. Energy Efficiency in Greenhouse Evaporative Cooling Techniques: Cooling Boxes versus Cellulose Pads, Energies, 7, 1427-1447. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Sattar, Sarmad Salem and Al-Badri, Samer Badri 2012. Rationalization of water consumption for evaporative cooling pads. Iraqi J. of Agric. Sciences, 43(6): 78-82.

- Al-Helal, M. 2009. A Pilot-Scale Study for Evaluating the Performance of a Fan-Pad Cooling System under Different Climatic Conditions of Saudi Arabia, Misr J. Ag. Eng., 26(1): 514- 533.

- Dağtekin M., Karaca C., Yıldız Y., Başçetinçelik A., Paydak Ö. 2011. The effects of air velocity on the performance of pad evaporative cooling systems. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 6:1813-22.

- Franco, A., Valera, D. L., Madueno, A., and Peña, A. 2010. Influence of water and air flow on the performance of cellulose evaporative cooling pads used in Mediterranean greenhouses. Transactions of the ASABE, 53(2), pp. 565-576. [CrossRef]

- Dhamneya, A. K., S. P. S. Rajput, and A. Singh. 2017. “Experimental Performance Analysis of Alternative Cooling Pad Made byAgricultural Waste for Direct Evaporative Cooling System. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology. 8: 7.

- Laknizi, A., Ben Abdellah, A., Mahdaoui, M., and Anoune, K. 2021. Application of Taguchi and ANOVA methods in the optimisation of a direct evaporative cooling pad. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 14(5), pp. 1218-1228. [CrossRef]

- Egbal Elmsaad, Abda Emam, Abdelnaser Omran. 2023. Effect of Utilization of Different Materials and Thicknesses Evaporative Cooling Pad on Cooling Efficiency in Greenhouses in Hot-Arid Regions. Egyptian Journal of Agronomy, 45(2), pp. 171-187.

- Metin Dağtekin, Cengiz Karaca, Y ilmaz Yildiz, Ali Basçetinçelik and Ömer Paydak. 2020. The effects of air velocity on the performance of pad evaporative cooling systems. African Journal of Agronomy, 8 (11), pp. 001-010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).