Submitted:

30 January 2024

Posted:

31 January 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

PD pathophysiology and current treatments

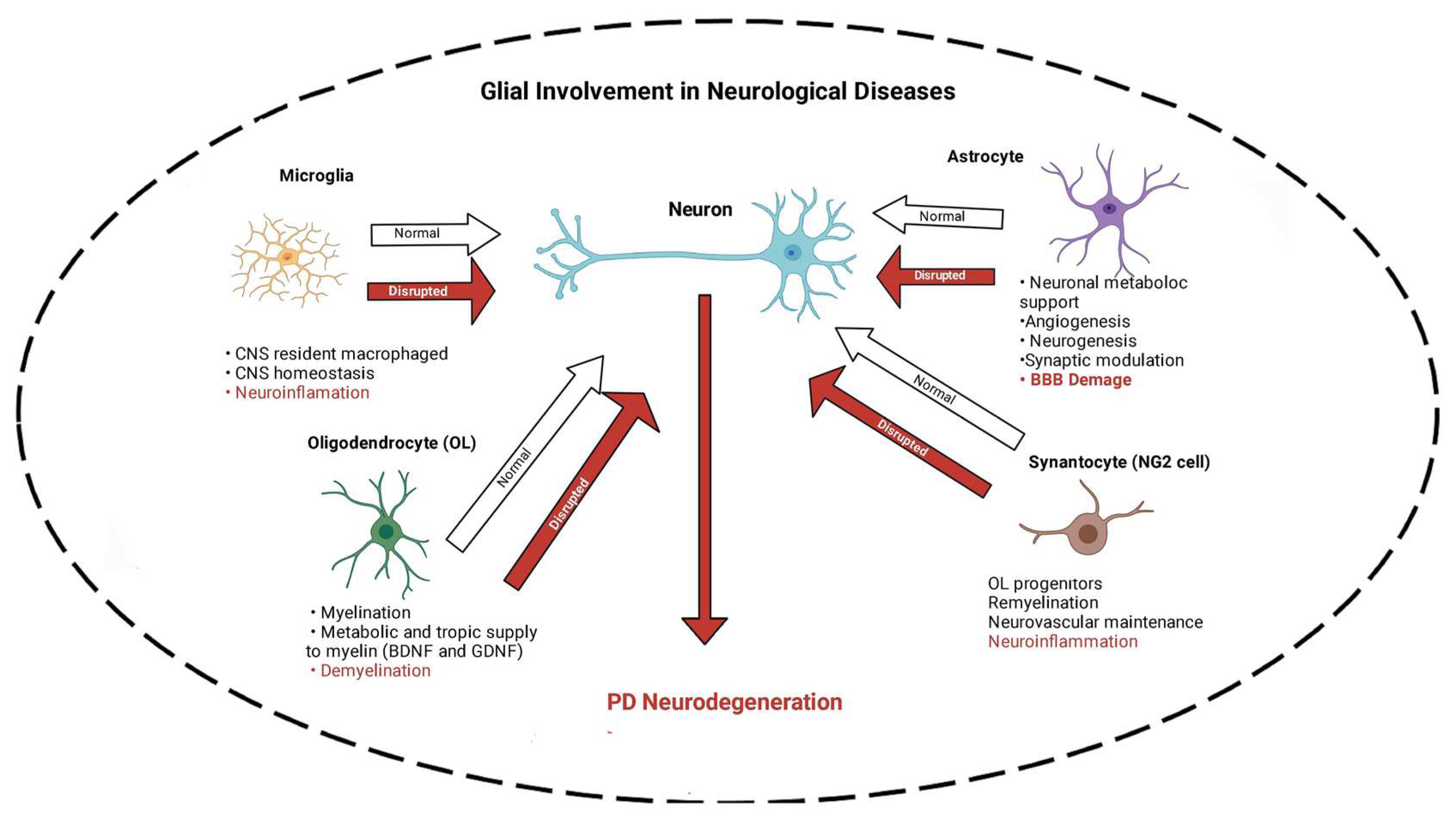

Glial Cells

Microglia

Microglia- Synucleinopathies

Astroglia

Oligodendrocytes

Synantocytes (NG2 cells)

Nicotine

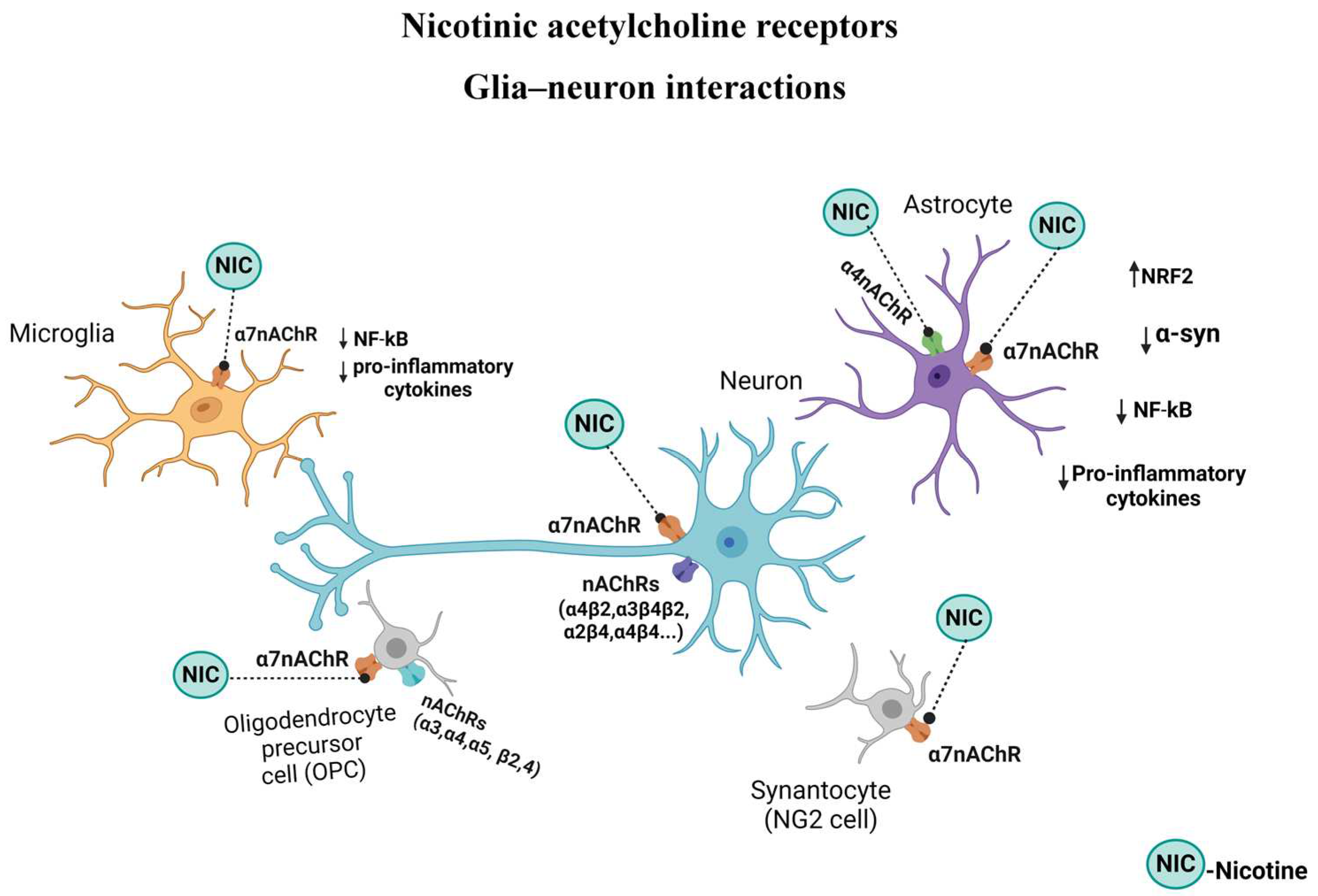

nAChRs

Nicotine for PD

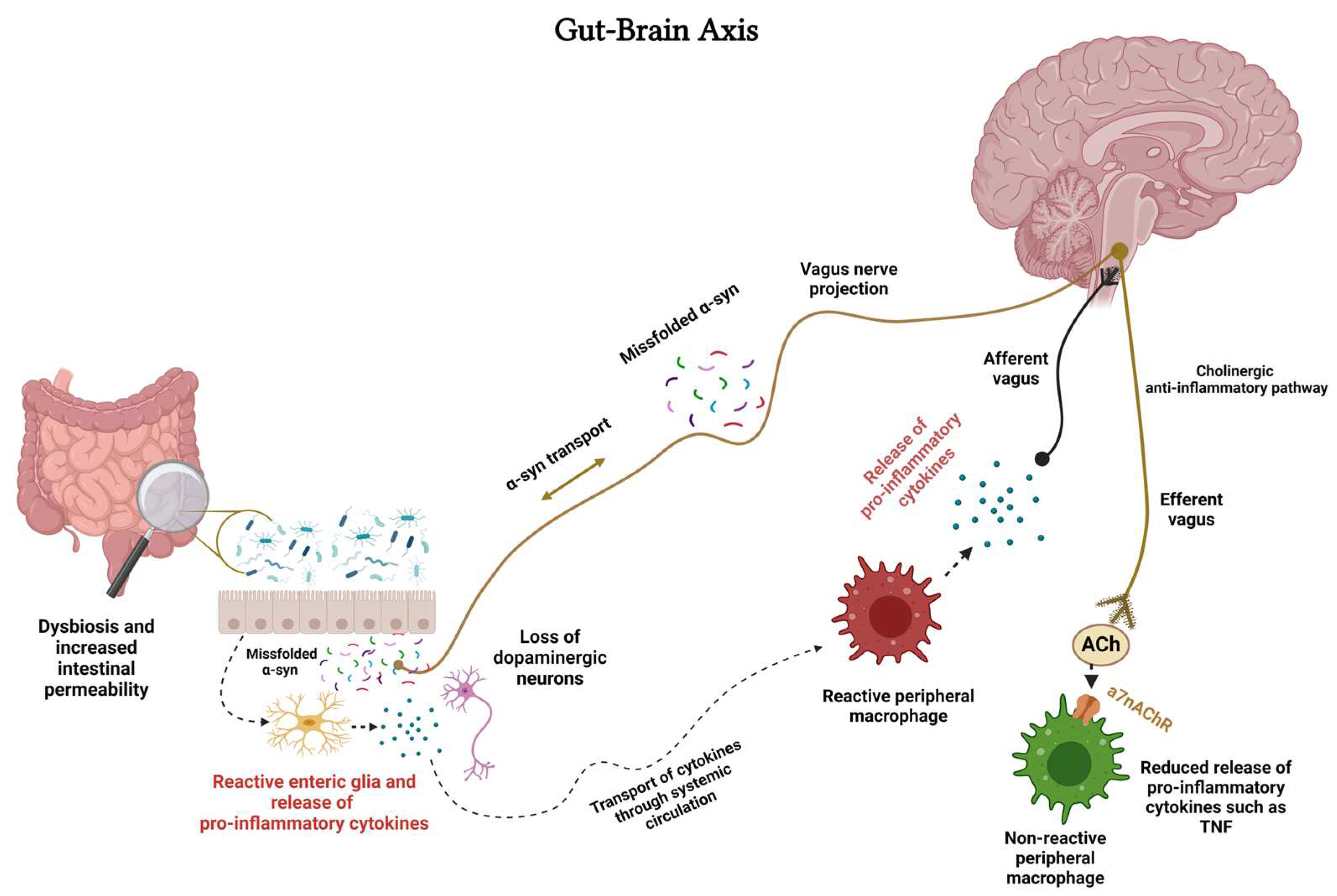

nAChRs - Microglia and Gut-Brain Axis

nAChRs - Astroglia

nAChRs – Oligodendrocytes (OLs)

nAChRs - NG2 cells

Conclusions

Ethical Approval

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Parkinson Disease Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Snijders, A.H.; Takakusaki, K.; Debu, B.; Lozano, A.M.; Krishna, V.; Fasano, A.; Aziz, T.Z.; Papa, S.M.; Factor, S.A.; Hallett, M. Physiology of Freezing of Gait. Ann Neurol 2016, 80, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B.; Aschner, M. Novel Pharmacotherapies in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2021, 39, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallés, A.S.; Barrantes, F.J. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Dysfunction in Addiction and in Some Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Cells 2023, Vol. 12, Page 2051 2023, 12, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinderi, K.; Bostantjopoulou, S.; Fidani, L. The Genetic Background of Parkinson’s Disease: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Acta Neurol Scand 2016, 134, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, P.; Jankovic, J. The Genetics of Parkinson Disease. Ageing Res Rev 2018, 42, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, A.; Divya, K.P.; Vijayaraghavan, A. Parkinson’s Disease - Genetic Cause. Curr Opin Neurol 2023, 36, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Paudel, Y.N.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Piperi, C. Environmental Impact on the Epigenetic Mechanisms Underlying Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis: A Narrative Review. Brain Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 175 2022, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, S.M. Environmental Toxins and Parkinson’s Disease. 2014, 54, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan-Montojo, F.; Reichmann, H. Considerations on the Role of Environmental Toxins in Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease Pathophysiology. Translational Neurodegeneration 2014 3:1 2014, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Mannervik, B. A Preclinical Model for Parkinson’s Disease Based on Transcriptional Gene Activation via KEAP1/NRF2 to Develop New Antioxidant Therapies. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, S.M.; Ng, K.Y.; Chye, S.M.; Ling, A.P.K.; Voon, K.G.L.; Yap, Y.J.; Koh, R.Y. The Mechanism of Action of Salsolinol in Brain: Implications in Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2021, 19, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, B.L.B.; de Souza, L.R.; Sousa, K.P.A.; Ferreira, J. V.; Padilha, E.C.; da Silva, C.H.T.P.; Taft, C.A.; Hage-Melim, L.I.S. Parkinson’s Disease: A Review from Pathophysiology to Treatment. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 20, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.T.; Oertel, W.H.; Surmeier, D.J.; Geibl, F.F. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease – a Key Disease Hallmark with Therapeutic Potential. Mol Neurodegener 2023, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizama, B.N.; Chu, C.T. Neuronal Autophagy and Mitophagy in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Aspects Med 2021, 82, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsager, J.; Andersen, K.B.; Knudsen, K.; Skjærbæk, C.; Fedorova, T.D.; Okkels, N.; Schaeffer, E.; Bonkat, S.K.; Geday, J.; Otto, M.; et al. Brain-First versus Body-First Parkinson’s Disease: A Multimodal Imaging Case-Control Study. Brain 2020, 143, 3077–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Ilyas, I.; Mahmood, A.; Hou, L. Microglia and Astrocytes Dysfunction and Key Neuroinflammation-Based Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, A.; Markiewicz-Gospodarek, A.; Markiewicz, R.; Chilimoniuk, Z.; Borowski, B.; Trubalski, M.; Czarnek, K. Distribution of Iron, Copper, Zinc and Cadmium in Glia, Their Influence on Glial Cells and Relationship with Neurodegenerative Diseases. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isik, S.; Yeman Kiyak, B.; Akbayir, R.; Seyhali, R.; Arpaci, T. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Pajarillo, E.; Nyarko-Danquah, I.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Role of Astrocytes in Parkinson’s Disease Associated with Genetic Mutations and Neurotoxicants. Cells 2023, 12, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesana, R.; Reid, A.J.; Tata, A.M. Emerging Roles of Cholinergic Receptors in Schwann Cell Development and Plasticity. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hustad, E.; Aasly, J.O. Clinical and Imaging Markers of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.K.; Tanner, C.M.; Brundin, P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med 2020, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajjwal, P.; Flores Sanga, H.S.; Acharya, K.; Tango, T.; John, J.; Rodriguez, R.S.C.; Dheyaa Marsool Marsool, M.; Sulaimanov, M.; Ahmed, A.; Hussin, O.A. Parkinson’s Disease Updates: Addressing the Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, along with the Medical and Surgical Treatment. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 2023, 85, 4887–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quik, M.; Boyd, J.T.; Bordia, T.; Perez, X. Potential Therapeutic Application for Nicotinic Receptor Drugs in Movement Disorders. Nicotine Tob Res 2019, 21, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, V.; Rossiter, R.; Blanchard, D. Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. Aust J Gen Pract 2021, 50, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrj, M.; Russo, M.; Carrarini, C.; Delli Pizzi, S.; Thomas, A.; Bonanni, L.; Espay, A.J.; Sensi, S.L. Functional Neurological Disorder and Somatic Symptom Disorder in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurol Sci 2022, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Biase, L.; Pecoraro, P.M.; Carbone, S.P.; Caminiti, M.L.; Di Lazzaro, V. Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesias in Parkinson’s Disease: An Overview on Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Therapy Management Strategies and Future Directions. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove, F.; Angeloni, B.; Sanginario, P.; Rossini, P.M.; Calabresi, P.; Di Iorio, R. Neuroplasticity in Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesias: An Overview on Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Targets. Prog Neurobiol 2024, 232, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Pal, G. Initial Management of Parkinson’s Disease. BMJ 2014, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakad, A.; Jankovic, J. Diagnosis and Management of Parkinson’s Disease. Semin Neurol 2017, 37, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, F. Tratamento Da Doença de Parkinson. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1995, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek, N. Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurol India 2019, 67, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bye, L.J.; Finol-Urdaneta, R.K.; Tae, H.-S.; Adams, D.J. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Key Targets for Attenuating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2023, 157, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, V.; Mendoza, C.; Iarkov, A. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and Learning and Memory Deficits in Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Front Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The Human Brain in Numbers: A Linearly Scaled-up Primate Brain. Front Hum Neurosci 2009, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Huang, S. Comparative Insight into Microglia/Macrophages-Associated Pathways in Glioblastoma and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.G.; Almeida, R.F.; Souza, D.O.; Zimmer, E.R. The Astrocyte Biochemistry. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2019, 95, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvento, G.; Bolaños, J.P. Astrocyte-Neuron Metabolic Cooperation Shapes Brain Activity. Cell Metab 2021, 33, 1546–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; Copperi, F.; Diano, S. Microglia in Central Control of Metabolism. Physiology 2024, 39, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, D.R.; Slevin, M.; Barcutean, L.; Forro, T.; Boghitoiu, T.; Balasa, R. Astrocyte Involvement in Blood–Brain Barrier Function: A Critical Update Highlighting Novel, Complex, Neurovascular Interactions. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.M.; Auld, V.; Klämbt, C. Glia as Functional Barriers and Signaling Intermediaries. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2024, 16, a041423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Tripartite Synapses: Astrocytes Process and Control Synaptic Information. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Eroglu, C. Cell Biology of Astrocyte-Synapse Interactions. Neuron 2017, 96, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, N.I.; Brazhnik, E.S.; Kitchigina, V.F. Pathological Correlates of Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease: From Molecules to Neural Networks. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2023, 88, 1890–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiacco, T.A.; Mccarthy, K.D.; Savtchouk, I.; Volterra, A. Gliotransmission: Beyond Black-and-White. Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 38, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalo, U.; Koh, W.; Lee, C.J.; Pankratov, Y. The Tripartite Glutamatergic Synapse. Neuropharmacology 2021, 199, 108758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasia-Filho, A.A.; Calcagnotto, M.E.; von Bohlen und Halbach, O. Dendritic Spines; Rasia-Filho, A.A., Calcagnotto, M.E., von Bohlen und Halbach, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Vol. 34, ISBN 978-3-031-36158-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dringen, R.; Pawlowski, P.G.; Hirrlinger, J. Peroxide Detoxification by Brain Cells. J Neurosci Res 2005, 79, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dringen, R.; Brandmann, M.; Hohnholt, M.C.; Blumrich, E.M. Glutathione-Dependent Detoxification Processes in Astrocytes. Neurochemical Research 2014 40:12 2014, 40, 2570–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, M.S.; Jackson, J.; Sheu, S.H.; Chang, C.L.; Weigel, A. V.; Liu, H.; Pasolli, H.A.; Xu, C.S.; Pang, S.; Matthies, D.; et al. Neuron-Astrocyte Metabolic Coupling Protects against Activity-Induced Fatty Acid Toxicity. Cell 2019, 177, 1522–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.M.; Blazer-Yost, B. Channels and Transporters in Astrocyte Volume Regulation in Health and Disease. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 56, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebling, F.J.P.; Lewis, J.E. Tanycytes and Hypothalamic Control of Energy Metabolism. Glia 2018, 66, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, K.A.; Huang, N.; Xie, Y.; LiCausi, F.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Sheng, Z.H. Oligodendrocytes Enhance Axonal Energy Metabolism by Deacetylation of Mitochondrial Proteins through Transcellular Delivery of SIRT2. Neuron 2021, 109, 3456–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.W.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Galichet, C. The Properties and Functions of Glial Cell Types of the Hypothalamic Median Eminence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, J.; Wiley, C.A. Microglia:Key Innate Immune Cells of the Brain. Toxicol Pathol 2011, 39, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Holtzman, D.M. Emerging Roles of Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Immunity 2022, 55, 2236–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Petidier, M.; Guerri, C.; Moreno-Manzano, V. Toll-like Receptors 2 and 4 Differentially Regulate the Self-Renewal and Differentiation of Spinal Cord Neural Precursor Cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wies Mancini, V.S.B.; Mattera, V.S.; Pasquini, J.M.; Pasquini, L.A.; Correale, J.D. Microglia-derived Extracellular Vesicles in Homeostasis and Demyelination/Remyelination Processes. J Neurochem 2024, 168, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Alzarea, S. Glial Mechanisms Underlying Major Depressive Disorder: Potential Therapeutic Opportunities. 2019; 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi, C.; Verkhratsky, A.; Parpura, V.; Li, B. Neuroglia in Psychiatric Disorders. 2021; 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hanslik, K.L.; Marino, K.M.; Ulland, T.K. Modulation of Glial Function in Health, Aging, and Neurodegenerative Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao G Shared and Disease-Specific Glial Gene Expression Changes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat Aging 2023, 3, 246–247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Guan, A.; Liu, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Noteworthy Perspectives on Microglia in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.; Fernandez-Villalba, E.; Izura, V.; Lucas-Ochoa, A.; Menezes-Filho, N.; Santana, R.; de Oliveira, M.; Araújo, F.; Estrada, C.; Silva, V.; et al. Combined 1-Deoxynojirimycin and Ibuprofen Treatment Decreases Microglial Activation, Phagocytosis and Dopaminergic Degeneration in MPTP-Treated Mice. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 2021, 16, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, Z.; Lu, G.; Chan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wong, G.C. Microglia Activation, Classification and Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammatory Modulators in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, F.; Munitic, I.; Vidatic, L.; Papić, E.; Rački, V.; Nimac, J.; Jurak, I.; Novotni, G.; Rogelj, B.; Vuletic, V.; et al. Overlapping Neuroimmune Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanism and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, D.; Sriram, K. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Elicited by Occupational Injuries and Toxicants. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitgareeva, A.R.; Bulygin, K. V.; Gareev, I.F.; Beylerli, O.A.; Akhmadeeva, L.R. The Role of Microglia in the Development of Neurodegeneration. Neurological Sciences 2020, 41, 3609–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, S.F.; Elbadry, A.M.M.; Elbokhomy, A.S.; Salama, G.A.; Salama, R.M. The Dual Face of Microglia (M1/M2) as a Potential Target in the Protective Effect of Nutraceuticals against Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Aging 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ma, Z.; Chen, X.; Shu, S. Microglia Activation in Central Nervous System Disorders: A Review of Recent Mechanistic Investigations and Development Efforts. Front Neurol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.-È.; Stevens, B.; Sierra, A.; Wake, H.; Bessis, A.; Nimmerjahn, A. The Role of Microglia in the Healthy Brain: Figure 1. The Journal of Neuroscience 2011, 31, 16064–16069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, A. Two-Photon Imaging of Microglia in the Mouse Cortex In Vivo. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2012, 2012, pdb–prot069294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyh, J.; Paeschke, S.; Mages, B.; Michalski, D.; Nowicki, M.; Bechmann, I.; Winter, K. Classification of Microglial Morphological Phenotypes Using Machine Learning. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebell, J.M.; Taylor, S.E.; Cao, T.; Harrison, J.L.; Lifshitz, J. Rod Microglia: Elongation, Alignment, and Coupling to Form Trains across the Somatosensory Cortex after Experimental Diffuse Brain Injury. J Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Morganti-Kossmann, C.; Lifshitz, J.; Ziebell, J.M. Rod Microglia: A Morphological Definition. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatoba, O.; Itokazu, T.; Yamashita, T. Microglia as Therapeutic Target in Central Nervous System Disorders. J Pharmacol Sci 2020, 144, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyell, J.S.; Sriparna, M.; Ying, M.; Mao, X. The Interplay between α-Synuclein and Microglia in α-Synucleinopathies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Meng, H. The Involvement of α-Synucleinopathy in the Disruption of Microglial Homeostasis Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Communication and Signaling 2024, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, W.; Sun, Y.; Wu, M. New Insight on Microglia Activation in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Therapeutics. Front Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramowicz, K.; Siwecka, N.; Galita, G.; Kucharska-Lusina, A.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Majsterek, I. Alpha-Synuclein Contribution to Neuronal and Glial Damage in Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Yoon, H.; Ha, S.; Kang, S.U. Molecular Crosstalk Between Circadian Rhythmicity and the Development of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Neurosci 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Ruiz, M.A.; Guerrero-Vargas, N.N.; Lagunes-Cruz, A.; González-González, S.; García-Aviles, J.E.; Hurtado-Alvarado, G.; Mendez-Hernández, R.; Chavarría-Krauser, A.; Morin, J.; Arriaga-Avila, V.; et al. Circadian Modulation of Microglial Physiological Processes and Immune Responses. Glia 2023, 71, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, L.; Irschick, R.; Schanda, K.; Reindl, M.; Klimaschewski, L.; Poewe, W.; Wenning, G.K.; Stefanova, N. Toll-like Receptor 4 Is Required for A-synuclein Dependent Activation of Microglia and Astroglia. Glia 2013, 61, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Acioglu, C.; Heary, R.F.; Elkabes, S. Role of Astroglial Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) in Central Nervous System Infections, Injury and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 91, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Rivas, L.A.; Madhivanan, K.; Aulston, B.D.; Wang, L.; Prakashchand, D.D.; Boyer, N.P.; Saia-Cereda, V.M.; Branes-Guerrero, K.; Pizzo, D.P.; Bagchi, P.; et al. Serine-129 Phosphorylation of α-Synuclein Is an Activity-Dependent Trigger for Physiologic Protein-Protein Interactions and Synaptic Function. Neuron 2023, 111, 4006–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Pishva, E.; Chouliaras, L.; Lunnon, K. Elucidating Distinct Molecular Signatures of Lewy Body Dementias. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 188, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Sriram, K. Neuron-Astrocyte Omnidirectional Signaling in Neurological Health and Disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E.F.; Hartnell, I.J.; Boche, D. Microglia and Astrocyte Function and Communication: What Do We Know in Humans? Front Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Fan, Y. Activation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Protects Against 1-Methyl-4-Phenylpyridinium-Induced Astroglial Apoptosis. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.P.; Fu, X.; Sandin, J.N.; Neupane, K.R.; Lakes, J.E.; Grady, M.E.; Richards, C.I. Nicotine Induces Morphological and Functional Changes in Astrocytes via Nicotinic Receptor Activity. Glia 2021, 69, 2037–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Schneider, A.M.; Mulloy, S.M.; Lee, A.M. Expression Pattern of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Transcripts in Neurons and Astrocytes in the Ventral Tegmental Area and Locus Coeruleus. European Journal of Neuroscience 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Si, T.; Wang, Z.; Wen, P.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, F.; Li, Q. Astrocytic A4-Containing NAChR Signaling in the Hippocampus Governs the Formation of Temporal Association Memory. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 112674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitmer, J.W. Strategies for Metabolic Exchange between Glial Cells and Neurons. Respir Physiol 2001, 129, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magistretti, P.J.; Allaman, I. Lactate in the Brain: From Metabolic End-Product to Signalling Molecule. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2018 19:4 2018, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Sastre, M.; Del Tredici, K. Development of α-Synuclein Immunoreactive Astrocytes in the Forebrain Parallels Stages of Intraneuronal Pathology in Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol 2007, 114, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erustes, A.G.; Stefani, F.Y.; Terashima, J.Y.; Stilhano, R.S.; Monteforte, P.T.; da Silva Pereira, G.J.; Han, S.W.; Calgarotto, A.K.; Hsu, Y. Te; Ureshino, R.P.; et al. Overexpression of α-Synuclein in an Astrocyte Cell Line Promotes Autophagy Inhibition and Apoptosis. J Neurosci Res 2018, 96, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Munõz, P.; Zavala, P.; Villa, M.; Cuevas, C.; Ahumada, U.; Graumann, R.; Nore, B.F.; Couve, E.; Mannervik, B.; et al. Glutathione Transferase Mu 2 Protects Glioblastoma Cells against Aminochrome Toxicity by Preventing Autophagy and Lysosome Dysfunction. Autophagy 2014, 10, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Muñoz, P.; Graumann, R.; Paris, I.; Segura-Aguilar, J. DT-Diaphorase Protects Astrocytes from Aminochrome-Induced Toxicity. Neurotoxicology 2016, 55, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, C.; Huenchuguala, S.; Muñoz, P.; Villa, M.; Paris, I.; Mannervik, B.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Glutathione Transferase-M2-2 Secreted from Glioblastoma Cell Protects SH-SY5Y Cells from Aminochrome Neurotoxicity. Neurotox Res 2015, 27, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, R.; Armijo, A.; Muñoz, P.; Hultenby, K.; Hagg, A.; Inzunza, J.; Nalvarte, I.; Varshney, M.; Mannervik, B.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Cellular Trafficking of Glutathione Transferase M2-2 Between U373MG and SHSY-S7 Cells Is Mediated by Exosomes. Neurotox Res 2021, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Muñoz, P.; Inzunza, J.; Varshney, M.; Nalvarte, I.; Mannervik, B. Neuroprotection against Aminochrome Neurotoxicity: Glutathione Transferase M2-2 and DT-Diaphorase. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabresi, P.; Mechelli, A.; Natale, G.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Ghiglieri, V. Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Synucleinopathies: From Overt Neurodegeneration Back to Early Synaptic Dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.K.; Saijo, K.; Winner, B.; Marchetto, M.C.; Gage, F.H. Mechanisms Underlying Inflammation in Neurodegeneration. Cell 2010, 140, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, F.; Quintana, F.J. The Role of Astrocytes in CNS Inflammation. Trends Immunol 2020, 41, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patani, R.; Hardingham, G.E.; Liddelow, S.A. Functional Roles of Reactive Astrocytes in Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurol 2023, 19, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bartheld, C.S.; Bahney, J.; Herculano-Houzel, S. The Search for True Numbers of Neurons and Glial Cells in the Human Brain: A Review of 150 Years of Cell Counting. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2016, 524, 3865–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.-Q.; Zhang, W.-J.; Su, D.-F.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Miao, C.-Y. Cellular Responses and Functions of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Activation in the Brain: A Narrative Review. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 509–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalski, J.-P.; Kothary, R. Oligodendrocytes in a Nutshell. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, D.; Sandor, C.; Volpato, V.; Caffrey, T.M.; Monzón-Sandoval, J.; Bowden, R.; Alegre-Abarrategui, J.; Wade-Martins, R.; Webber, C. A Single-Cell Atlas of the Human Substantia Nigra Reveals Cell-Specific Pathways Associated with Neurological Disorders. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4183–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menichella, D.M.; Majdan, M.; Awatramani, R.; Goodenough, D.A.; Sirkowski, E.; Scherer, S.S.; Paul, D.L. Genetic and Physiological Evidence That Oligodendrocyte Gap Junctions Contribute to Spatial Buffering of Potassium Released during Neuronal Activity. The Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 26, 10984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J. Neuronal Activity and Remyelination: New Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advancements. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bsibsi, M.; Nomden, A.; van Noort, J.M.; Baron, W. Toll-like Receptors 2 and 3 Agonists Differentially Affect Oligodendrocyte Survival, Differentiation, and Myelin Membrane Formation. J Neurosci Res 2012, 90, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Toll-like Receptors in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 332, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.-J.; Pérez-Acuña, D.; Rhee, K.H.; Lee, S.-J. Changes in Oligodendroglial Subpopulations in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Brain 2023, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.A.; Nishiyama, A. NG2 Cells (Polydendrocytes): Listeners to the Neural Network with Diverse Properties. Glia 2014, 62, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirdajova, D.; Anderova, M. NG2 Cells and Their Neurogenic Potential. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2020, 50, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.-P.; Zhao, J.; Li, S. Roles of NG2 Glial Cells in Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Neurosci Bull 2011, 27, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimou, L.; Gallo, V. <scp>NG</Scp> 2-glia and Their Functions in the Central Nervous System. Glia 2015, 63, 1429–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, G.; Errede, M.; Girolamo, F.; Morando, S.; Ivaldi, F.; Panini, N.; Bendotti, C.; Perris, R.; Furlan, R.; Virgintino, D.; et al. NG2, a Common Denominator for Neuroinflammation, Blood–Brain Barrier Alteration, and Oligodendrocyte Precursor Response in EAE, Plays a Role in Dendritic Cell Activation. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 132, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Gu, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Hou, J.; Chen, R.; Sun, Q.; Sun, Y.; et al. NG2 Glia Regulate Brain Innate Immunity via TGF-Β2/TGFBR2 Axis. BMC Med 2019, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Geng, P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C.; Guo, C.; Dong, W.; Jin, X. The NG2-Glia Is a Potential Target to Maintain the Integrity of Neurovascular Unit after Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 180, 106076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Fort, M.; Audinat, E.; Angulo, M.C. Functional A7-containing Nicotinic Receptors of NG2-expressing Cells in the Hippocampus. Glia 2009, 57, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Tascio, D.; Jabs, R.; Boehlen, A.; Domingos, C.; Skubal, M.; Huang, W.; Kirchhoff, F.; Henneberger, C.; Bilkei-Gorzo, A.; et al. Dysfunction of <scp>NG2</Scp> Glial Cells Affects Neuronal Plasticity and Behavior. Glia 2023, 71, 1481–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dani, J.A. Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Structure and Function and Response to Nicotine. Int Rev Neurobiol 2015, 124, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke, R.L.; Lindstrom, J.M. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Conventional and Unconventional Ligands and Signaling. Neuropharmacology 2020, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchini, M.; Changeux, J.P. Nicotinic Receptors: From Protein Allostery to Computational Neuropharmacology. Mol Aspects Med 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, S.; Yamaguti, Y.; Tsuda, I. Review: Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors to Regulate Important Brain Activity—What Occurs at the Molecular Level? Cogn Neurodyn 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasheverov, I.; Kudryavtsev, D.; Shelukhina, I.; Nikolaev, G.; Utkin, Y.; Tsetlin, V. Marine Origin Ligands of Nicotinic Receptors: Low Molecular Compounds, Peptides and Proteins for Fundamental Research and Practical Applications. Biomolecules 2022, Vol. 12, Page 189 2022, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugayar, A.A.; da Silva Guimarães, G.; de Oliveira, P.H.T.; Miranda, R.L.; dos Santos, A.A. Apoptosis in the Neuroprotective Effect of A7 Nicotinic Receptor in Neurodegenerative Models. J Neurosci Res 2023, 101, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keever, K.R.; Yakubenko, V.P.; Hoover, D.B. Neuroimmune Nexus in the Pathophysiology and Therapy of Inflammatory Disorders: Role of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol Res 2023, 191, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, P.; Kabbani, N. Ionotropic and Metabotropic Responses by Alpha 7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol Res 2023, 197, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, A.J.; McIntosh, J.M. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Therapeutic Targets for Novel Ligands to Treat Pain and Inflammation. Pharmacol Res 2023, 190, 106715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, Z.; Motlagh Ghoochani, B.F.N.; Hasani Nourian, Y.; Jamalkandi, S.A.; Ghanei, M. The Controversial Effect of Smoking and Nicotine in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2023, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelukhina, I.; Siniavin, A.; Kasheverov, I.; Ojomoko, L.; Tsetlin, V.; Utkin, Y. A7- and A9-Containing Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Functioning of Immune System and in Pain. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, L.; Ables, J.L.; Braunscheidel, K.M.; Caligiuri, S.P.B.; Elayouby, K.S.; Fillinger, C.; Ishikawa, M.; Moen, J.K.; Kenny, P.J. Neurobiological Mechanisms of Nicotine Reward and Aversion. Pharmacol Rev 2022, 74, 271–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Picciotto, M.R. Nicotine Addiction: More than Just Dopamine. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 83, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, L.; Milani, F.; Fabrizi, R.; Belli, M.; Cristina, M.; Zagà, V.; de Iure, A.; Cicconi, L.; Bonassi, S.; Russo, P. Nicotine: From Discovery to Biological Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B.; Csoka, A.B.; Manaye, K.F.; Copeland, R.L. Novel Targets for Parkinsonism-Depression Comorbidity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2019, 167, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Targeting the Cholinergic System in Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2020, 41, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandelman, J.A.; Newhouse, P.; Taylor, W.D. Nicotine and Networks: Potential for Enhancement of Mood and Cognition in Late-Life Depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.A.; Tolomeo, S.; Steele, J.D.; Baldacchino, A.M. Severity of Negative Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Occurring during Acute Abstinence from Tobacco: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 115, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouli, F.; Changeux, J.P. Do Nicotinic Receptors Modulate High-Order Cognitive Processing? Trends Neurosci 2020, 43, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nop, O.; Senft Miller, A.; Culver, H.; Makarewicz, J.; Dumas, J.A. Nicotine and Cognition in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, B.; Harvey, A.N.; Concheiro-Guisan, M.; Huestis, M.A.; Ross, T.J.; Stein, E.A. Nicotinic Receptor Modulation of the Default Mode Network. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2021, 238, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhao, C.; Li, G. The Regulation of Exosome Generation and Function in Physiological and Pathological Processes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Wang, Q.; Lai, R.; Zhang, D.; Diao, Y.; Yin, Y. Nicotine Induced Neurocognitive Protection and Anti-Inflammation Effect by Activating α 4β 2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Ischemic Rats. Nicotine Tob Res 2020, 22, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionov, I.D.; Pushinskaya, I.I.; Gorev, N.P.; Frenkel, D.D.; Severtsev, N.N. Anticataleptic Activity of Nicotine in Rats: Involvement of the Lateral Entorhinal Cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2021, 238, 2471–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, A. V.; Callahan, P.M. A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors as Therapeutic Targets in Schizophrenia: Update on Animal and Clinical Studies and Strategies for the Future. Neuropharmacology 2020, 170, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagdas, D.; Gurun, M.S.; Flood, P.; Papke, R.L.; Damaj, M.I. New Insights on Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors as Targets for Pain and Inflammation: A Focus on A7 NAChRs. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018, 16, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Collazo, P.; Diéguez, C.; Nogueiras, R.; Rahmouni, K.; Fernández-Real, J.M.; López, M. Nicotine’ Actions on Energy Balance: Friend or Foe? Pharmacol Ther 2021, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Kenny, P.J. Central and Peripheral Actions of Nicotine That Influence Blood Glucose Homeostasis and the Development of Diabetes. Pharmacol Res 2023, 194, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlivanidou, M.; Ninou, E.; Karagiorgou, K.; Tsantila, A.; Mantegazza, R.; Francesca, A.; Furlan, R.; Dudeck, L.; Steiner, J.; Tzartos, J.; et al. Autoimmunity to Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol Res 2023, 192, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.C.; Soler-Llavina, G.; Kambara, K.; Bertrand, D. The Importance of Ligand Gated Ion Channels in Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Biochem Pharmacol 2023, 212, 115532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, P.C.; Leong, R.W.L. Review Article: Ulcerative Colitis, Smoking and Nicotine Therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012, 36, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, N.; Hisaoka-Nakashima, K.; Nakata, Y. Regulation by Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors of Microglial Glutamate Transporters: Role of Microglia in Neuroprotection. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection 2018, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lin, H.; Zou, M.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, Z.; Pan, X.; Zhang, W. Nicotine in Inflammatory Diseases: Anti-Inflammatory and Pro-Inflammatory Effects. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, K.; Matsuo, K. Nicotine Exerts a Stronger Immunosuppressive Effect Than Its Structural Analogs and Regulates Experimental Colitis in Rats. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.; Auyeung, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Etiology, Pathogenesis and Current Therapy. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, J.P.; Watad, A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Nicotine and Autoimmunity: The Lotus’ Flower in Tobacco. Pharmacol Res 2018, 128, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B.; Copeland, R.L.; Aschner, M. Nicotine and the Nicotinic Cholinergic System in COVID-19. FEBS J 2020, 287, 3656–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bele, T.; Turk, T.; Križaj, I. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Cancer: Limitations and Prospects. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2024, 1870, 166875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, R.L.; Leggett, Y.A.; Kanaan, Y.M.; Taylor, R.E.; Tizabi, Y. Neuroprotective Effects of Nicotine against Salsolinol-Induced Cytotoxicity: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2005, 8, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, B.; Csoka, A.B.; Bhatti, A.; Copeland, R.L.; Tizabi, Y. Butyrate Protects Against Salsolinol-Induced Toxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells: Implication for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2020, 38, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B.; Aschner, M. Butyrate Protects and Synergizes with Nicotine against Iron- and Manganese-Induced Toxicities in Cell Culture. Neurotox Res 2024, 42, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getachew, B.; Csoka, A.B.; Aschner, M.; Tizabi, Y. Nicotine Protects against Manganese and Iron-Induced Toxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells: Implication for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem Int 2019, 124, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, P.; Huenchuguala, S.; Paris, I.; Cuevas, C.; Villa, M.; Caviedes, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J.; Tizabi, Y. Protective Effects of Nicotine Against Aminochrome-Induced Toxicity in Substantia Nigra Derived Cells: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2012, 22, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Bai, J. Nicotine Suppresses the Neurotoxicity by MPP +/MPTP through Activating A7nAChR/PI3K/Trx-1 and Suppressing ER Stress. Neurotoxicology 2017, 59, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Bi, W.; Zheng, K.; Zhu, E.; Wang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Chang, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, B.; Lu, Z.; et al. Nicotine Prevents Oxidative Stress-Induced Hippocampal Neuronal Injury Through A7-NAChR/Erk1/2 Signaling Pathway. Front Mol Neurosci 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Xie, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, W.; Ji, R.; Gong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Mao, J.; et al. Nicotine Alleviates MPTP-Induced Nigrostriatal Damage through Modulation of JNK and ERK Signaling Pathways in the Mice Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, M.B.; Alijevic, O.; Johne, S.; Overk, C.; Hashimoto, M.; Kondylis, A.; Adame, A.; Dulize, R.; Peric, D.; Nury, C.; et al. Nicotine-Mediated Effects in Neuronal and Mouse Models of Synucleinopathy. Front Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Ic.; Porcu, A.; Romoli, B.; Keisler, M.; Manfredsson, F.P.; Powell, S.B.; Dulcis, D. Nicotine-Mediated Recruitment of GABAergic Neurons to a Dopaminergic Phenotype Attenuates Motor Deficits in an Alpha-Synuclein Parkinson’s Model. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Emadi, S.; Shen, J.-X.; Sierks, M.R.; Wu, J. Human A4β2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor as a Novel Target of Oligomeric α-Synuclein. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Hirohata, M.; Yamada, M. Anti-Fibrillogenic and Fibril-Destabilizing Activity of Nicotine in Vitro: Implications for the Prevention and Therapeutics of Lewy Body Diseases. Exp Neurol 2007, 205, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, K.; Hirohata, M.; Yamada, M. Alpha-Synuclein Assembly as a Therapeutic Target of Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. Curr Pharm Des 2008, 14, 3247–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardani, J.; Sethi, R.; Roy, I. Nicotine Slows down Oligomerisation of α-Synuclein and Ameliorates Cytotoxicity in a Yeast Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, F.; Mutti, V.; Savoia, P.; Barbon, A.; Bellucci, A.; Missale, C.; Fiorentini, C. Nicotine Prevents Alpha-Synuclein Accumulation in Mouse and Human IPSC-Derived Dopaminergic Neurons through Activation of the Dopamine D3- Acetylcholine Nicotinic Receptor Heteromer. Neurobiol Dis 2019, 129, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Tao, T.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y. Activation of A7-NAChRs Promotes the Clearance of α-Synuclein and Protects Against Apoptotic Cell Death Induced by Exogenous α-Synuclein Fibrils. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgayar, S.A.M.; Hussein, O.A.; Mubarak, H.A.; Ismaiel, A.M.; Gomaa, A.M.S. Testing Efficacy of the Nicotine Protection of the Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta in a Rat Parkinson Disease Model. Ultrastructure Study. Ultrastruct Pathol 2022, 46, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, I.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Wen, H. Research Progress of α-Synuclein Aggregation Inhibitors for Potential Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 23, 1959–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.R.; Magen, I.; Bove, N.; Zhu, C.; Lemesre, V.; Dutta, G.; Elias, C.J.; Lester, H.A.; Chesselet, M.F. Chronic Nicotine Improves Cognitive and Social Impairment in Mice Overexpressing Wild Type α-Synuclein. Neurobiol Dis 2018, 117, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.-S.; Liu, S.C.-H.; Wu, R.-M. Alpha-Synuclein and Cognitive Decline in Parkinson Disease. Life 2021, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo Jurado-Coronel, J.; Avila-Rodriguez, M.; Capani, F.; Gonzalez, J.; Echeverria Moran, V.; E. Barreto, G. Targeting the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors (NAChRs) in Astrocytes as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Pharm Des 2016, 22, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.L.; Clemens, S.G.; Feany, M.B. Nicotine-Mediated Rescue of A-Synuclein Toxicity Requires Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2 in Drosophila. Movement Disorders 2023, 38, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B. Nicotinic Receptor Intervention in Parkinson’s Disease: Future Directions. Clin Pharmacol Transl Med 2017, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Khatri, S.N.; Maulik, M.; Bult-Ito, A.; Schulte, M. Allosterism of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Therapeutic Potential for Neuroinflammation Underlying Brain Trauma and Degenerative Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, D.; Dei, S.; Arias, H.R.; Braconi, L.; Gabellini, A.; Teodori, E.; Romanelli, M.N. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Allosteric Modulators. Molecules 2023, 28, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, V.R.; Millar, N.S. Potentiation and Allosteric Agonist Activation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: Binding Sites and Hypotheses. Pharmacol Res 2023, 191, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Wang, H.; Czura, C.J.; Friedman, S.G.; Tracey, K.J. The Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway: A Missing Link in Neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med 2003, 9, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, D.B. Cholinergic Modulation of the Immune System Presents New Approaches for Treating Inflammation. Pharmacol Ther 2017, 179, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa-Vidal, N.; Rodríguez-Aponte, A.S.; Lasalde-Dominicci, J.A.; Capó-Vélez, C.M.; Delgado-Vélez, M. Cholinergic Polarization of Human Macrophages. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. Fat Meets the Cholinergic Antiinflammatory Pathway. J Exp Med 2005, 202, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda Ruzafa, L.; Cedillo, J.L.; Hone, A.J. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Involvement in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Interactions with Gut Microbiota. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Gut Bacteria and Neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaliere, G.; Traina, G. Neuroinflammation in the Brain and Role of Intestinal Microbiota: An Overview of the Players. J Integr Neurosci 2023, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudino dos Santos, J.C.; Lima, M.P.P.; Brito, G.A. de C.; Viana, G.S. de B. Role of Enteric Glia and Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Parkinson Disease Pathogenesis. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 84, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, I.; Issac, P.K.; Rahman, Md.M.; Guru, A.; Arockiaraj, J. Gut-Brain Axis a Key Player to Control Gut Dysbiosis in Neurological Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.; Sokratian, A.; Chavez, K.R.; King, S.; Swain, S.M.; Snyder, J.C.; West, A.B.; Liddle, R.A. Gut Mucosal Cells Transfer α-Synuclein to the Vagus Nerve. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, S.; Rizza, S.; Federici, M. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Relationships among the Vagus Nerve, Gut Microbiota, Obesity, and Diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2023, 60, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takbiri Osgoei, L.; Parivar, K.; Ebrahimi, M.; Mortaz, E. Nicotine Modulates the Release of Inflammatory Cytokines and Expression of TLR2, TLR4 of Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, C.A.; Sun, D.; Randall, P.A. Differential Effects of Nicotine, Alcohol, and Coexposure on Neuroimmune-Related Protein and Gene Expression in Corticolimbic Brain Regions of Rats. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, K.; Kimura, H.; Yanagisawa, D.; Harada, K.; Nishimura, K.; Kitamura, Y.; Shimohama, S.; Tooyama, I. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and Microglia as Therapeutic and Imaging Targets in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lao, K.; Qiu, Z.; Rahman, M.S.; Zhang, Y.; Gou, X. Potential Astrocytic Receptors and Transporters in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 67, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, M.J.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Marashli, S.; Oglo, D.N.; Ojha, B.; Naser, P. V.; Gan, Z.; Kuner, R. Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Nucleus of Meynert Regulates Chronic Pain-like Behavior via Modulation of the Prelimbic Cortex. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulousakis, P.; Andrade, P.; Visser-Vandewalle, V.; Sesia, T. The Nucleus Basalis of Meynert and Its Role in Deep Brain Stimulation for Cognitive Disorders: A Historical Perspective. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 69, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, I.C.; Kumar, A.; Nordberg, A. The Role of Astrocytic A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2023, 19, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; McIntire, J.; Ryan, S.; Dunah, A.; Loring, R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Astroglial A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Are Mediated by Inhibition of the NF-ΚB Pathway and Activation of the Nrf2 Pathway. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesana, R.; Salazar Intriago, M.S.; Dini, L.; Tata, A.M. Cholinergic Modulation of Neuroinflammation: Focus on A7 Nicotinic Receptor. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, M.A.; Hughes, E.G. Neuron-Oligodendroglia Interactions: Activity-Dependent Regulation of Cellular Signaling. Neurosci Lett 2020, 727, 134916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Shu, S.; Zhai, L.; Xia, S.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; Bao, X.; Liu, P.; Xu, Y. Optogenetic Stimulation of MPFC Alleviates White Matter Injury-Related Cognitive Decline after Chronic Ischemia through Adaptive Myelination. Advanced Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, B.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Barzan, R.; Chen, T.-J.; Kukley, M. Different Patterns of Neuronal Activity Trigger Distinct Responses of Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells in the Corpus Callosum. PLoS Biol 2017, 15, e2001993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, D.A.; Angulo, M.C. Can Enhancing Neuronal Activity Improve Myelin Repair in Multiple Sclerosis? Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, O.; Arai, M.; Dateki, M.; Oishi, K.; Takishima, K. Donepezil-induced Oligodendrocyte Differentiation Is Mediated through Estrogen Receptors. J Neurochem 2020, 155, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, G.; Wennström, M.; Müller, M.B.; Treccani, G. NG2-Glia: Rising Stars in Stress-Related Mental Disorders? Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.A.; Wallis, G.J.; Wilcox, K.S. Reactivity and Increased Proliferation of NG2 Cells Following Central Nervous System Infection with Theiler’s Murine Encephalomyelitis Virus. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeckova, L.; Knotek, T.; Kriska, J.; Hermanova, Z.; Kirdajova, D.; Kubovciak, J.; Berkova, L.; Tureckova, J.; Camacho Garcia, S.; Galuskova, K.; et al. Astrocyte-like Subpopulation of <scp>NG2</Scp> Glia in the Adult Mouse Cortex Exhibits Characteristics of Neural Progenitor Cells. Glia 2024, 72, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, Y.; Inden, M.; Minamino, H.; Abe, M.; Takata, K.; Taniguchi, T. The 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Nigrostriatal Neurodegeneration Produces Microglia-like NG2 Glial Cells in the Rat Substantia Nigra. Glia 2010, 58, 1686–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology , Function , and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science (1979) 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Yu, A.; Cheng, K.; Ma, J.; Murphy, S.; McNutt, P.M.; Zhang, Y. Insights into Optimizing Exosome Therapies for Acute Skin Wound Healing and Other Tissue Repair. Front Med 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Shahzad, K.; Zheng, J. Clinical Applications of Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.C.; Bortolanza, M.; Bribian, A.; Leal-Luiz, G.C.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; López-Mascaraque, L.; Del-Bel, E. Dynamic Involvement of Striatal NG2-Glia in L-DOPA Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinsonian Rats: Effects of Doxycycline. ASN Neuro 2023, 15, 175909142311559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, A.; Matsubara, K.; Matsubara, Y.; Nakaoka, H.; Sugiyama, T. The Influence of Nicotine on Trophoblast-Derived Exosomes in a Mouse Model of Pathogenic Preeclampsia. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Emerging roles of O-GlcNAcylation in protein trafficking and secretion. J Biol Chem 2024, 23, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).