Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

24 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

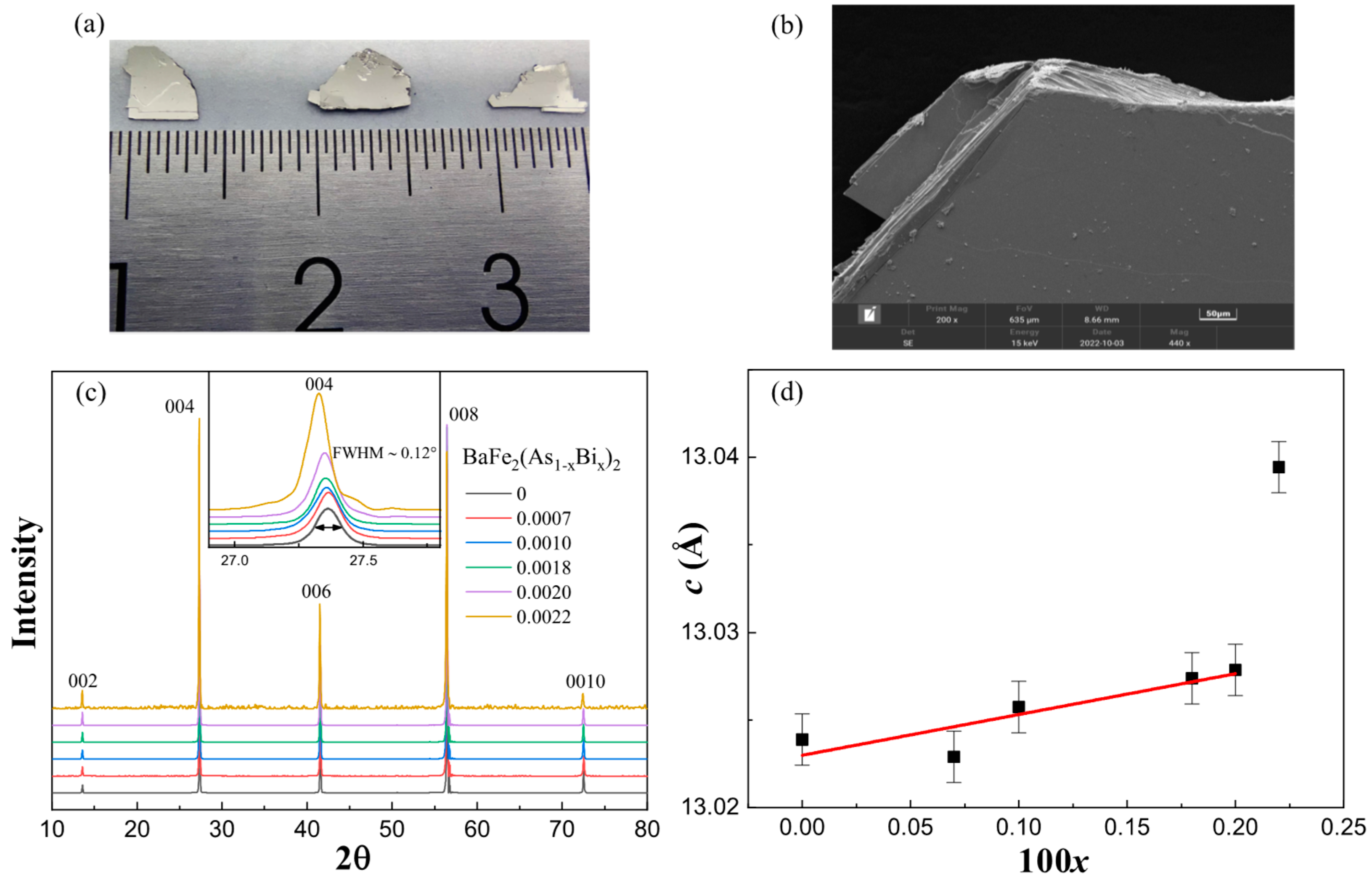

3.1. Actual doping concentration and lattice parameter c

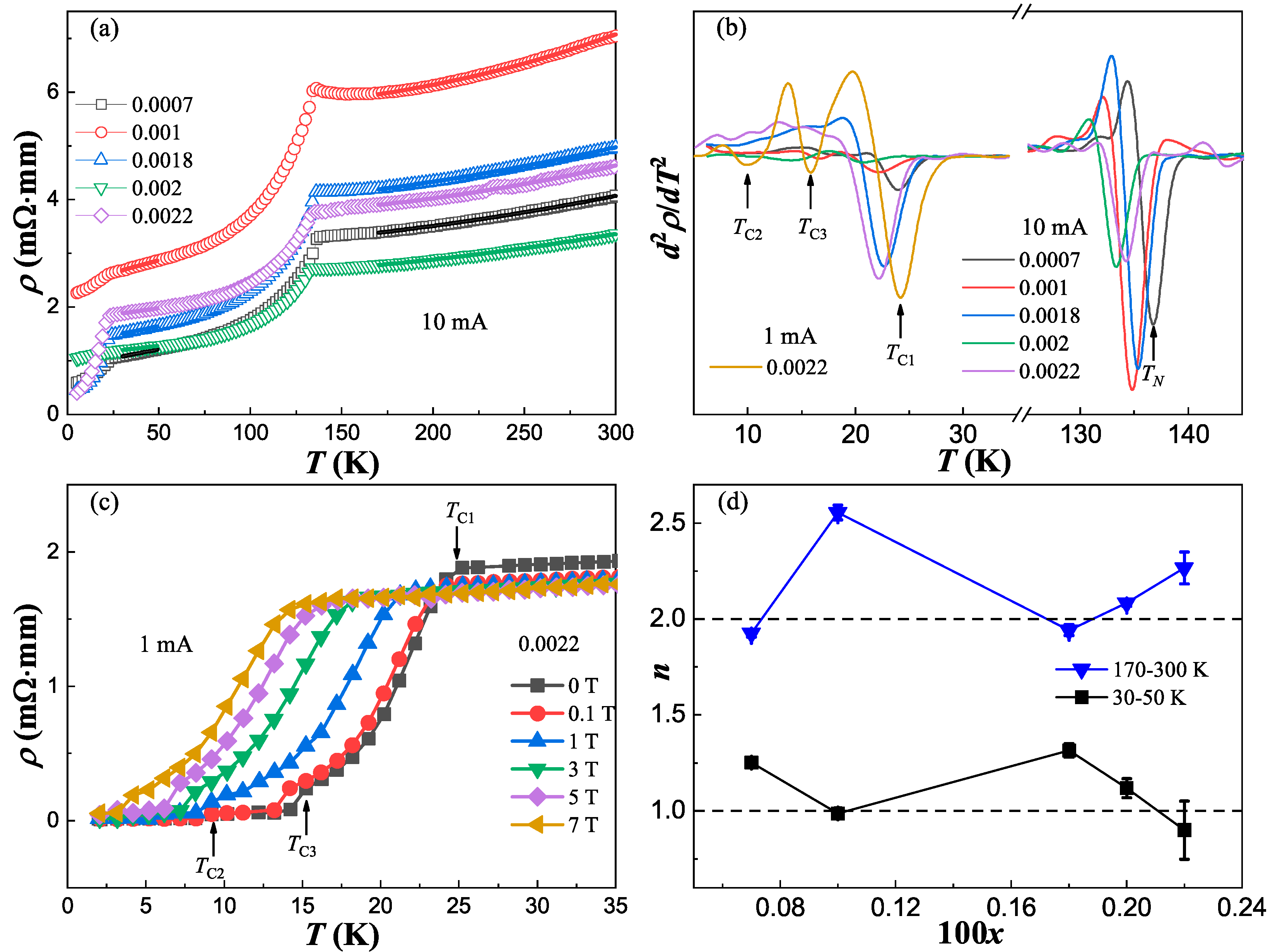

3.2. Superconducting transitions and non-Fermi liquid behavior

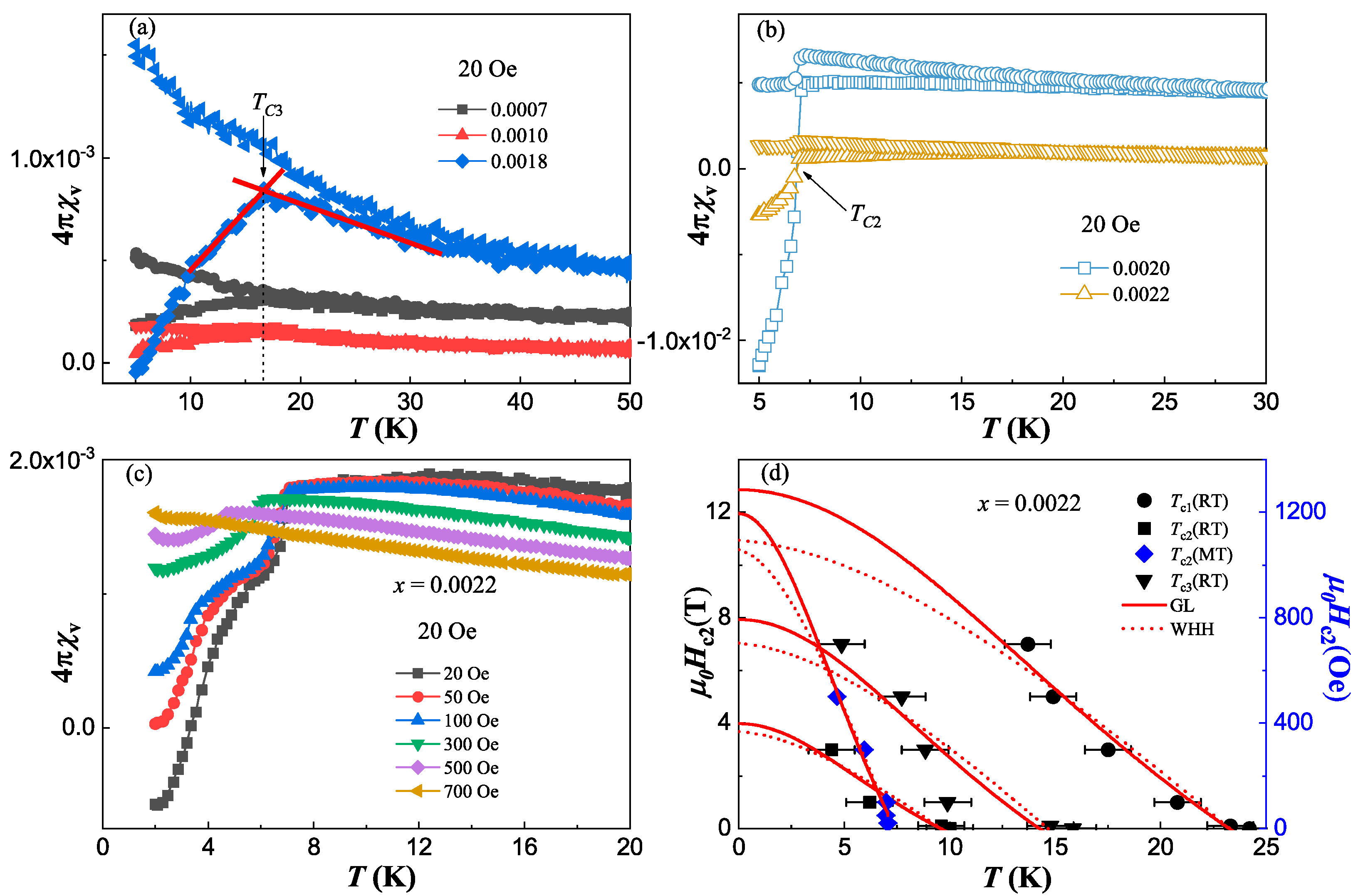

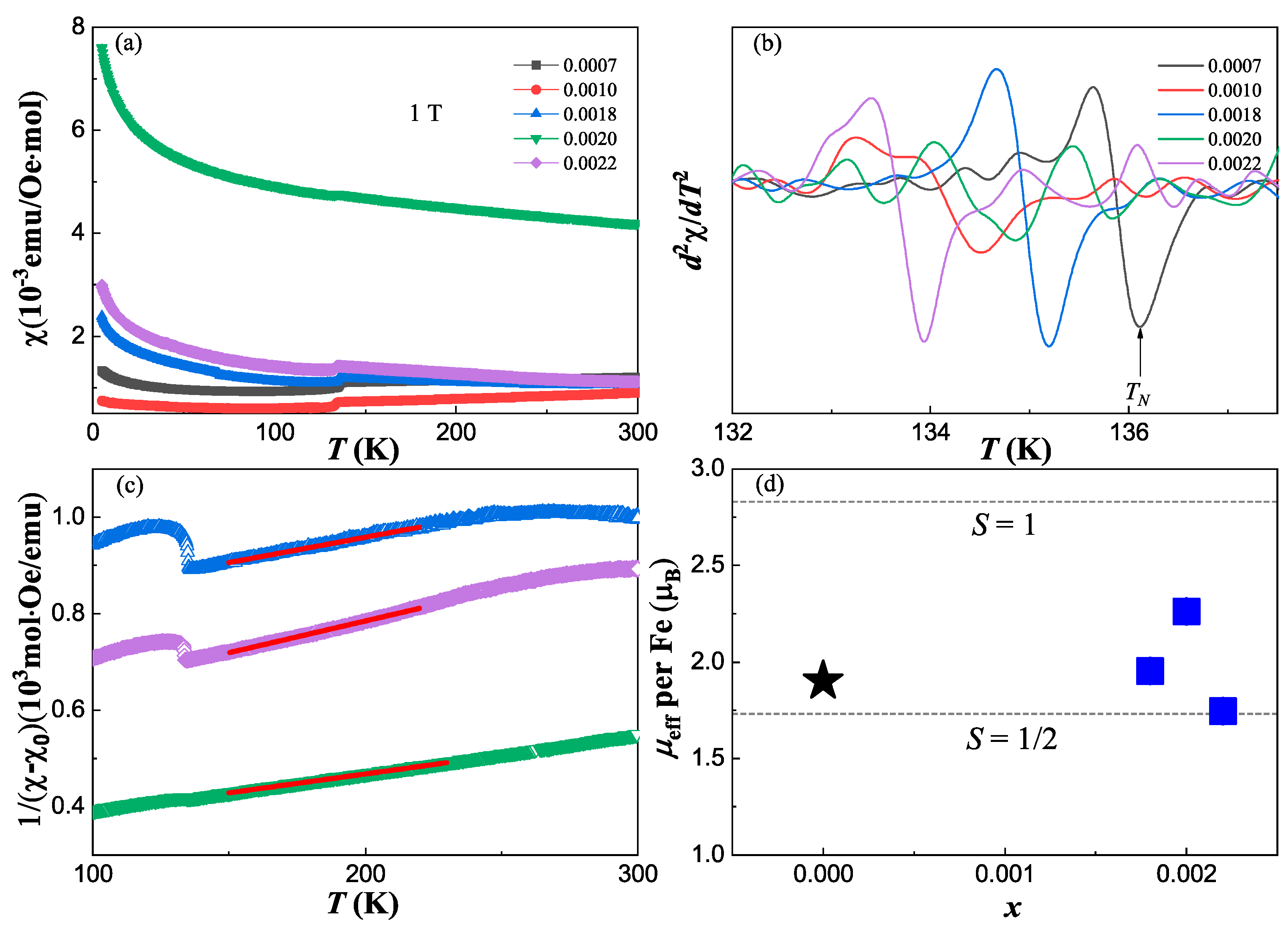

3.3. Superconducting volume and effective moment

3.4. Superconducting phasediagram

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. G. Bednorz; K. A. Muller. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba−La−Cu−O system. Zeitschrift Fur Physik B: Condensed Matter 1986, 64, 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Kamihara, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs (x=0.05-0.12) with Tc = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, M.; Tegel, M.; Johrendt, D. Superconductivity at 38 K in the iron arsenide (Ba1-xKx)Fe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, K.; Lv, B.; Lorenz, B.; Guloy, A. M.; Chen, F.; Xue, Y. Y.; Chu, C. W. Superconducting fe-based compounds (A1-xSrx)Fe2As2 with A = K and Cs with transition temperatures up to 37 K. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 107007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Liu, Q. Q.; Wang, X. C.; Deng, Z.; Lv, Y. X.; Zhu, J. L.; Li, F. Y.; Jin, C. Q. Superconductivity above 33 K in (Ca1 −xNax)Fe2As2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 222203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xing, H.; Xuan, G.; Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Feng, C.; Dai, J.; Xu, Z. a.; Cao, G. Superconductivity up to 30 K in the vicinity of the quantum critical point in BaFe2(As1−xPx)2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 382203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, A.; Ni, N.; Kracher, A.; Yan, J. Q.; Bud’ko, S. L.; Canfield, P. C. Physical and magnetic properties of Ba(Fe1−xRux)2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 014534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefat, A. S.; Jin, R. Y.; McGuire, M. A.; Sales, B. C.; Singh, D. J.; Mandrus, D. Superconductivity at 22 K in Co-doped BaFe2As2 crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 117004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L. J.; Luo, Y. K.; Wang, Q. B.; Chen, H.; Ren, Z.; Tao, Q.; Li, Y. K.; Lin, X.; He, M.; Zhu, Z. W.; Cao, G. H.; Xu, Z. A. Superconductivity induced by Ni doping in BaFe2As2 single crystals. New. J. Phys. 2009, 11, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, A.; Hodovanets, H.; Torikachvili, M. S.; Ran, S.; Kracher, A.; Straszheim, W.; Yan, J. Q.; Mun, E.; Canfield, P. C. Physical and magnetic properties of Ba(Fe1−xMnx)2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 144528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefat, A. S.; Singh, D. J.; VanBebber, L. H.; Mozharivskyj, Y.; McGuire, M. A.; Jin, R.; Sales, B. C.; Keppens, V.; Mandrus, D. Absence of superconductivity in hole-doped BaFe2−xCrxAs2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 224524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-G.; Sheng, J.-M.; Tian, C.-K.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Xia, T.-L.; Wang, L.; Ye, F.; Tian, W.; Wang, J.-C.; Liu, J.-J.; Zhang, H.-X.; Bao, W.; Cheng, P. Effects of vanadium doping on BaFe2As2. EPL 2018, 122, 67006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Yoshida, T.; Ideta, S.; Shibata, G.; Ishigami, K.; Kadono, T.; Fujimori, A.; Hashimoto, M.; Lu, D. H.; Shen, Z. X.; Ono, K.; Sakai, E.; Kumigashira, H.; Matsuo, M.; Sasagawa, T. Absence of superconductivity in the hole-doped Fe pnictide Ba(Fe1−xMnx)2As2: Photoemission and x-ray absorption spectroscopy studies. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, K.; Christianson, A. D.; Wang, C. H.; Matsuda, M.; Cao, H.; VanBebber, L. H.; Zarestky, J. L.; Singh, D. J.; Sefat, A. S.; Lumsden, M. D. Competing magnetic ground states in nonsuperconducting Ba(Fe1−xCrx)2As2 as seen via neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 060509(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefat, A. S.; Nguyen, G. D.; Parker, D. S.; Fu, M. M.; Zou, Q.; Li, A.-P.; Cao, H. B.; Sanjeewa, L. D.; Li, L.; Gai, Z. Local superconductivity in vanadium iron arsenide. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konzen, L. M.; Sefat, A. S. Lattice parameters guide superconductivity in iron-arsenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundareswari, M.; Jayalakshmi, D. S.; Viswanathan, E. A first principles study on newly proposed (Ca/Sr/Ba)Fe2Bi2 compounds with their parent compounds. Philos Mag 2016, 96, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, D. S.; Sundareswari, M.; Viswanathan, E.; Hemanand, D.; Pranesh, V. Computational study on unconventional superconductivity and mechanical properties of novel antiferrromagnetic (Ca,Sr,Ba)Fe2Bi2 compounds. Int J Mod Phys B 2019, 33, 1950341. [Google Scholar]

- Vegard, L. Die Konstitution der Mischkristalle und die Raumfüllung der Atome. Z Phys 1921, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S.; Blasius, T. D.; Kim, E. G.; Stewart, G. R. Superconductivity in undoped single crystals of BaFe2As2: field and current dependence. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 342201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Hu, T.; He, S. K.; Shen, B.; Zhang, W. J.; Xu, B.; He, K. F.; Han, J.; Singh, Y. P.; Wen, H. H.; Qiu, X. G.; Panagopoulos, C.; Almasan, C. C. Filamentary superconductivity across the phase diagram of Ba(Fe,Co)2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 064521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Hu, T.; Dioguardi, A. P.; apRoberts-Warren, N.; Shockley, A. C.; Crocker, J.; Nisson, D. M.; Viskadourakis, Z.; Tee, X.; Radulov, I.; Almasan, C. C.; Curro, N. J.; Panagopoulos, C. Evidence for filamentary superconductivity nucleated at antiphase domain walls in antiferromagnetic CaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 024530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. R.; Butch, N. P.; Kirshenbaum, K.; Paglione, J.; Zavalij, P. Y. Superconducting and ferromagnetic phases induced by lattice distortions in stoichiometric SrFe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 037005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, Y.-M.; Xu, B.; Yang, R.; Liu, J.-Y.; Sui, Q.-T.; Luo, H.-Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, X.-Y.; Yang, H.; Qiu, X.-G. Magnetoresistivity and filamentary superconductivity in nickel-doped BaFe2As2. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 047401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G. D.; Fu, M.; Zou, Q.; Sanjeewa, L. D.; Li, A. P.; Sefat, A. S.; Gai, Z. Nanoscale Superconducting States in the Fe-Based Filamentary Superconductor of Pr-Doped CaFe2As2. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Hashimoto; K. Cho; T. Shibauchi; S. Kasahara; Y.Mizukami; R. Katsumata; Y. Tsuruhara; T. Terashima; H.Ikeda; M. A. Tanatar; H. Kitano; N. Salovich; R. W. Giannetta; P. Walmsley; A. Carrington; R. Prozorov; Matsuda, Y. A Sharp Peak of the Zero-Temperature Penetration Depth at Optimal Composition in BaFe2(As1–xPx)2. Science 2012, 336, 1554. [Google Scholar]

- R. Zhou; Z.Li; J. Yang; D.L. Sun; Lin,, C. T.; Zheng, G.-q. Quantum criticality in electron-doped BaFe2−xNixAs2. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, S.; Shibauchi, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Nakai, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Terashima, T.; Matsuda, Y. Abrupt recovery of Fermi-liquid transport following the collapse of the c axis in CaFe2(As1−xPx)2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 060505(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthamer, N. R.; Helfand, E.; Hohenberg, P. C. Temperature and Purity Dependence of the Superconducting Critical Field,Hc2. III. Electron Spin and Spin-Orbit Effects. Phys Rev 1966, 147, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Nagalakshmi, R.; Kulkarni, R.; Paulose, P. L.; Nigam, A. K.; Dhar, S. K.; Thamizhavel, A. Anisotropic magnetic and superconducting properties of CaFe2−xCoxAs2(x=0,0.06) single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 012504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, H.; Fang, L.; Mu, G.; Wen, H.-H. Upper critical field, Hall effect and magnetoresistance in the iron-based layered superconductor LaFeAsO0.9F0.1−δ. Superconductor Science and Technology 2008, 21, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogston, A. M. Upper Limit for the Critical Field in Hard Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1962, 9, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriger, L. W.; Liu, M.; Luo, H.; Ewings, R. A.; Frost, C. D.; Perring, T. G.; Dai, P. Temperature dependence of the paramagnetic spin excitations in BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 140403(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. M.; Su, Y. H.; Lu, Z. Y.; Weng, Z. Y.; Lee, D. H.; Xiang, T. Universal linear-temperature dependence of static magnetic susceptibility in iron pnictides. EPL 2009, 86, 37006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, J. M.; Taddei, K. M.; Bugaris, D. E.; Avci, S.; Chung, D. Y.; Claus, H.; dela Cruz, C.; Kanatzidis, M. G.; Rosenkranz, S.; Osborn, R.; Chmaissem, O. Coincident structural and magnetic order in BaFe2(As1−xPx)2 revealed by high-resolution neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Luo, H.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Chen, G.; Han, F.; Banjara, S. R.; Sapkota, A.; Kreyssig, A.; Goldman, A. I.; Yamani, Z.; Niedermayer, C.; Skoulatos, M.; Georgii, R.; Keller, T.; Wang, P.; Yu, W.; Dai, P. Structural and Magnetic Phase Transitions near Optimal Superconductivity in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 157002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Bharathi, A.; Chandra, S.; Reddy, V. R.; Paulraj, S.; Satya, A. T.; Sastry, V. S.; Gupta, A.; Sundar, C. S. Superconductivity in Ru-substituted polycrystalline BaFe2−xRuxAs2. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 174512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bharathi, A.; Vinod, K.; Sundar, C. S.; Srihari, V.; Sen, S.; Ghosh, H.; Sinha, A. K.; Deb, S. K. Structural investigations in BaFe2-xRuxAs2 as a function of Ru and temperature. Acta Crystallogr B Struct Sci Cryst Eng Mater 2015, 71, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nominal x | Actual x |

|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.0007 |

| 0.05 | 0.0020 |

| 0.10 | 0.0018 |

| 0.20 | 0.0022 |

| 0.35 | 0.0010 |

| x = 0.0022 | WHH fit | GL fit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TC (K) |

µ0HC2 (T) |

TC (K) |

µ0HC2 (T) |

ξGL (Å) |

|

| SC I (RT) | 23.3 | 10.91 | 23.2 | 12.90 | 51 |

| SC II (RT) | 9.6 | 3.67 | 9.6 | 3.98 | 91 |

| SC II (MT) | 7.3 | 0.11 | 7.4 | 0.12 | 524 |

| SC III (RT) | 14.7 | 7.01 | 14.3 | 7.93 | 65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).