3. Results and discussions

Figure 1(a) displays a low-magnification BF-TEM image, showing the cross-sectional overview of the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) film on the MAO (001) substrate, viewed along the [1

0] zone axis of MAO. From the cross-sectional image, the thicknesses of NCO/CFO film are measured to be both about 40 nm. The film interfaces were distinguished to be visible according to contrast variation within the film, as indicated by two horizontal white arrows.

Figure 1(b) shows a typical SAED pattern of the NCO/CFO film and part of the MAO substrate, recorded along the [1

0] zone axis of MAO substrate. The splitting of the 026 and 004 reflections along out-of-plane directions is discerned, indicating that the mismatch strain between film and substrate relaxes along out-of-plane. In contrast, the splitting of 440 diffraction reflection along in plane is not observed, as shown by the magnified part in the insert in

Figure 1(b). Particularly, the reflection spot splitting between bilayer films is neither observed along in-plane and out-of-plane.

Figure 1(c–e) are EDS mapping images acquired from the regions marked by the white square in (a), representing the signals of Co−Kα1, Fe−Kα1, Al−Kα1, respectively. The EDS results imply the truth that NCO film is fabricated on the top of the CFO film. From the result of SAED, it seems that the relaxation of epitaxial mismatch strain between two films along in-plane does not occur. The further investigation needs to be performed to distinguish the microstructures within the bilayer films and across the interfaces.

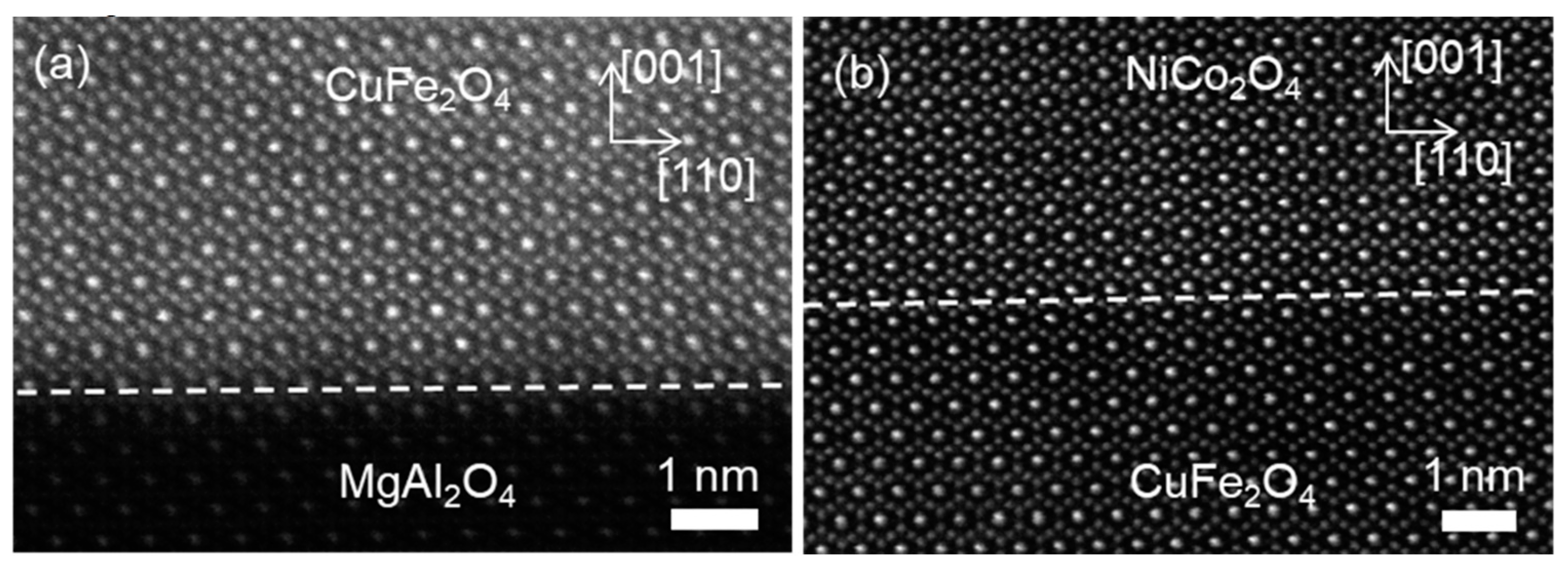

The bilayer heterostructure of NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm)/MAO is further examined by atomic resolution HAADF imaging as shown in

Figure 2, viewed along [1

0] zone axis of MAO. Based on the principle of Z contrast in HAADF imaging and element atom number (Z

Ni=28, Z

Co=27, Z

Cu=29, Z

Fe=26), the brighter spots in HAADF image are caused by the higher atom column density that is two times that of the darker spots along [1

0] zone axis [

30]. The HAADF images in

Figure 2(a, b) contains the interface between CFO film and MAO substrate and NCO film and CFO film, respectively, which shows the epitaxial interfaces at part of regions and no interfacial dislocations form at this region.

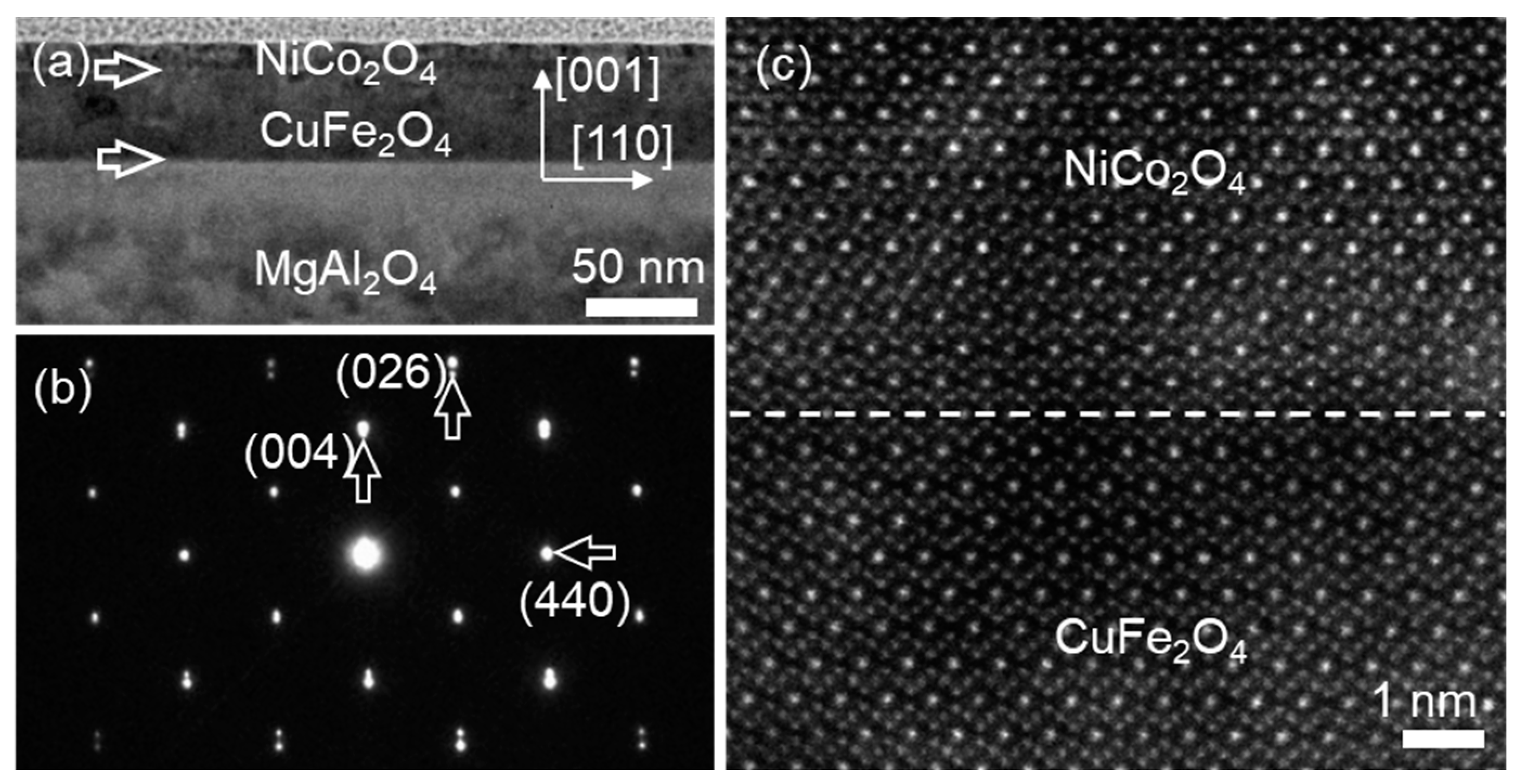

As a contrast, the high resolution HAADF images were acquired from other regions across the interface between NCO film and CFO film, viewed along [1

0] zone axis of MAO substrate, as shown in

Figure 3. The interface between NCO film and CFO film were denoted by the horizontal white dashed line. Remarkably, the interfacial dislocations and planar defects were both observed. The image in

Figure 3(a) contains an interfacial dislocation with the projected displacement of

an/8<112> (

an is lattice parameter of NCO film), acquired by the Burger circuit. This dislocation then induces an APB propagating into the NCO film as indicated by the oblique white arrow. The APB is located at (11

) plane and composed of octahedral B-site cations of the two domain regions separated by the APB. Neither overlapping of the two domains nor blurred area across the APB was observed. For clarity, this kind of APB is called a non-overlapping APB-I.

Figure 3(b) suggests that an

ac/4[110]-APB, which is edge-on along [1

0] viewing direction, marked by the white vertical arrow, forms within CFO film nearby the interface. The APB penetrated across the interface between NCO film and CFO film, propagated into the NCO film and decomposed into two APBs with the displacement vector of

an/4[01

] and

an/4[101], marked by two oblique white arrows, respectively. These two APBs have the projected displacement vector

an/8<112> along [1

0] direction. The regions across two APBs are blurred, both of which are the overlapping regions of the two domains, which was also observed in our previous work [

31]. In addition, a dislocation with the projected displacement vector of

an/4<00

> exists at the interface acquired by the Burger circuit. The dislocation core lies within NCO film, which is connected with the APB of

an/4[01

] in NCO film. Eventually, the dislocation terminates at this APB.

Figure 3(c) shows that an edge-on APB with the displacement of

ac/4[110] forms within the CFO film nearby the interface, as marked by the lower white arrow, which crosses the interface, penetrated into the NCO film and translates along the [

0] crystal direction, as marked by the upper white arrow. It is noticeable that there is no formation of interfacial dislocation in this region by the closed Burger circuit containing the interface and two APBs.

In NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterostructure, interfacial dislocations and the APBs within the film form to relax the epitaxial mismatch strain between NCO and CFO film. The heterostructure interface can both terminate the APBs formed in the CFO film and become the start point of the APB formation in the NCO film.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Atomic-resolution HAADF images of the heterostructure interfaces between NCO film and CFO film in different regions denoted by white dashed lines, showing the interfacial dislocations with different Burgers vectors. The oblique arrows marked the APBs in films.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Atomic-resolution HAADF images of the heterostructure interfaces between NCO film and CFO film in different regions denoted by white dashed lines, showing the interfacial dislocations with different Burgers vectors. The oblique arrows marked the APBs in films.

In addition, the structural transformation of non-overlapping APB is observed and resolved for the first time in the NCO films, which are shown in the HAADF images of

Figure 4(a–c), recorded along the [1

0] zone axis of the film. In

Figure 4(a), the white oblique arrow denotes the non-overlapping APB-I with the projected displacement of

an/8[112], which separated the film into domain I and domain II. It can be seen that the APB lies in (11

) plane and consists of B-site cations of both domain I and II. It should be noted that the present APB does not appear overlapped regions, but present the sharp boundary. In fact, the full displacement vector of this type of APB can be deduced to be

an/4[101] =

an/8[112] +

an/8[1

0] (or

an/4[011] =

an/8[112] +

an/8[

10]) taking account of the displacement along [1

0] zone axis, which suggests that the domains separated by this kind of APB is also displaced by 1/8 atomic plane in the [1

0] viewing direction, eventually forming the non-overlapping APB-I. Particularly, this type of APB was also observed in CFO film.

Figure 4(b) shows the atomic resolution HAADF image containing the translation of edge-on APBs. The two edge-on APBs both have the displacement vector of

an/4[110], recorded along [1

0] zone axis. The

an/4[110]-APB denoted by lower vertical arrow is displaced along [112] crystal orientation and formed the other

an/4[110]-APB denoted by upper vertical arrow. The area circled by the oval dotted box is the connection point at the two APBs before and after the translation, as shown by two connected brown diamonds in the

Figure 4(b) (the four vertices of brown diamond are the locations of octahedral B-site cations). Remarkably,

Figure 4(c) shows the continuous translation of

an/4[110]-APB along [112] crystal orientation, denoted by a series of brown diamonds, which generates the domain boundary. And it is called as non-overlapping APB-II for clarity, marked by the oblique white arrow. The non-overlapping APB-II also lies in (11

) plane and separates the film into domain I and domain II, and the boundary consists of the octahedral B-site cations of both domain I and II. However, it is different from the non-overlapping APB-I in

Figure 4(a). It appears that the non-overlapping APB-I in

Figure 4(a) shifted by 1/8 atomic plane along [112] crystal orientation would form non-overlapping APB-II in

Figure 4(c). For more clear explanation, the further investigation can be performed using structure models established by Vesta [

32].

Figure 4.

(a–c) Atomic-resolution HAADF images of NCO film in different regions, showing the non-overlapping APB located in (11) plane. The white arrows marked the APBs in films. The orange lozenges represent the shift of the APB.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Atomic-resolution HAADF images of NCO film in different regions, showing the non-overlapping APB located in (11) plane. The white arrows marked the APBs in films. The orange lozenges represent the shift of the APB.

On the basis of results in

Figure 4 and shift vector of

a/4[101] =

a/8[112] +

a/8[1

0], the atomic details of translation and transformation of non-overlapping APB can be understood by establishing the structural models along [1

0], [010] and [101] directions as shown in

Figure 5. In the APBs structural models, the tetrahedral sites (A-sites) in AB

2O

4 are highlighted in orange, and octahedral sites (B-site) highlighted in blue.

Figure 5(a) shows the structural model of the non-overlapping APB-I with the displacement of

a/4[101] projected along the [1

0] viewing direction. It can be seen that the oxygen sublattice in perfect lattice is maintained across such non-overlapping APB-I, while the regular cation arrangement is interrupted. The non-overlapping APB-I is denoted by a red dashed line and lies in (11

) plane, which consists of only B-site cations of two separated domain I and II. Then, rotating and seeing the structural model in [010] viewing direction, as shown in structural model of

Figure 5(b), the APB is marked by the red dashed line, while the displacement induced by this APB does not induce a visible difference across the APB in this viewing direction, as a result, the disturbance of the cation sublattice at the APB cannot be recognized. Continuously rotating the structural mode of in

Figure 5(a) and viewing it in [10

] direction, as shown in

Figure 5(c), it is obvious that the atomic structural model in

Figure 5(c) is the same as the atomic arrangement in

Figure 4(c). The formation of structural model in

Figure 5(c) can be understood by the continuous translation of edge-on

a/4[101]-APB along [121] crystal orientation, as shown in the brown diamonds and the connection point at the two APBs before and after the translation was also circled by the oval dotted box, which is consistent with the HAADF result in

Figure 4(b). The edge-on

a/4[101]-APB continuously translating along the [121] crystal orientation would result in the formation of non-overlap APB-II. Consequently, the non-overlapping APB-I with the displacement of

a/4[101] in the [1

0] viewing orientation can be formed by edge-on

a/4[101]-APB in the [10

] viewing orientation continuously translating along the [121] crystal orientation, eventually making non-overlapping APB-I lies in (11

) habit plane. Obviously, the non-overlapping APB-I in

Figure 5(a) projected in [1

0] shifted by 1/8 atomic plane along [112] crystal orientation would form the non-overlapping APB-II in

Figure 5(c) projected in [10

], which is consistent with the results of HAADF experiment in

Figure 4.

To further clarify the atomic arrangement at the non-overlapping APB observed in the film, the schematic model of this kind of APB is displayed in

Figure 5(d). In contrast to edge-sharing octahedra in perfect AB

2O

4 lattice, across the non-overlapping APB, both edge-sharing and corner-sharing octahedra coexist. For clear, the octahedra at the APB are marked as B1, B2 and B3, in fact, the cations located at these octahedra have the same coordination environment of oxygen octahedron. It can be seen that octahedra B1 and B3 (B2 and B3) share edge with bond angle of 90 degrees, and octahedra B1 and B2 share corner with bond angle of 180 degrees. As a result, a strong antiferromagnetic superexchange interaction occurs across the non-overlapping APB [

21], which is speculated to be an antiferromagnetic interface.

Figure 5.

(a, c) The structure models of APB, viewed along the [10] MAO zone axis. (b) The structure models of APB, viewed along the [010] MAO zone axis. The APB plane is marked by red dashed line, respectively. (d) the structure model showing the corner-shared octahedral cations at APB.

Figure 5.

(a, c) The structure models of APB, viewed along the [10] MAO zone axis. (b) The structure models of APB, viewed along the [010] MAO zone axis. The APB plane is marked by red dashed line, respectively. (d) the structure model showing the corner-shared octahedral cations at APB.

In order to understand the formation of dislocations and planar defects in different film thickness of NCO/CFO/MAO bilayer heterostructures, the NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) bilayer films were prepared on the MAO (001) substrate under the same deposition condition. The thickness of the NCO film changes, the heterojunction interface between the two films and the microstructures inside the film will change.

The cross-sectional overview of the NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) film prepared on the MAO (001) substrate, viewed along the [1

0] zone axis of MAO was shown in

Figure 6(a). The film interface was also visible according to contrast variation within the film, as indicated by two horizontal white arrows.

Figure 6(b) shows a typical SAED pattern of the NCO/CFO film and part of the MAO substrate, recorded along the [1

0] zone axis of MAO substrate. The splitting of the 026 and 004 reflections along out-of-plane directions is discerned, while the splitting of 440 diffraction reflection along in-plane is not observed. Particularly, the reflection splitting of bilayer films is neither observed along in-plane and out -of-plane. High resolution HAADF imaging was further conducted at the interface of bilayer film.

Figure 6(c) displays the smooth epitaxial interfaces, marked by the horizonal white line, without the formation of interfacial dislocations at this region. In contrast, the interfacial dislocations with different burgers vector were found at the interface in other interfacial regions.

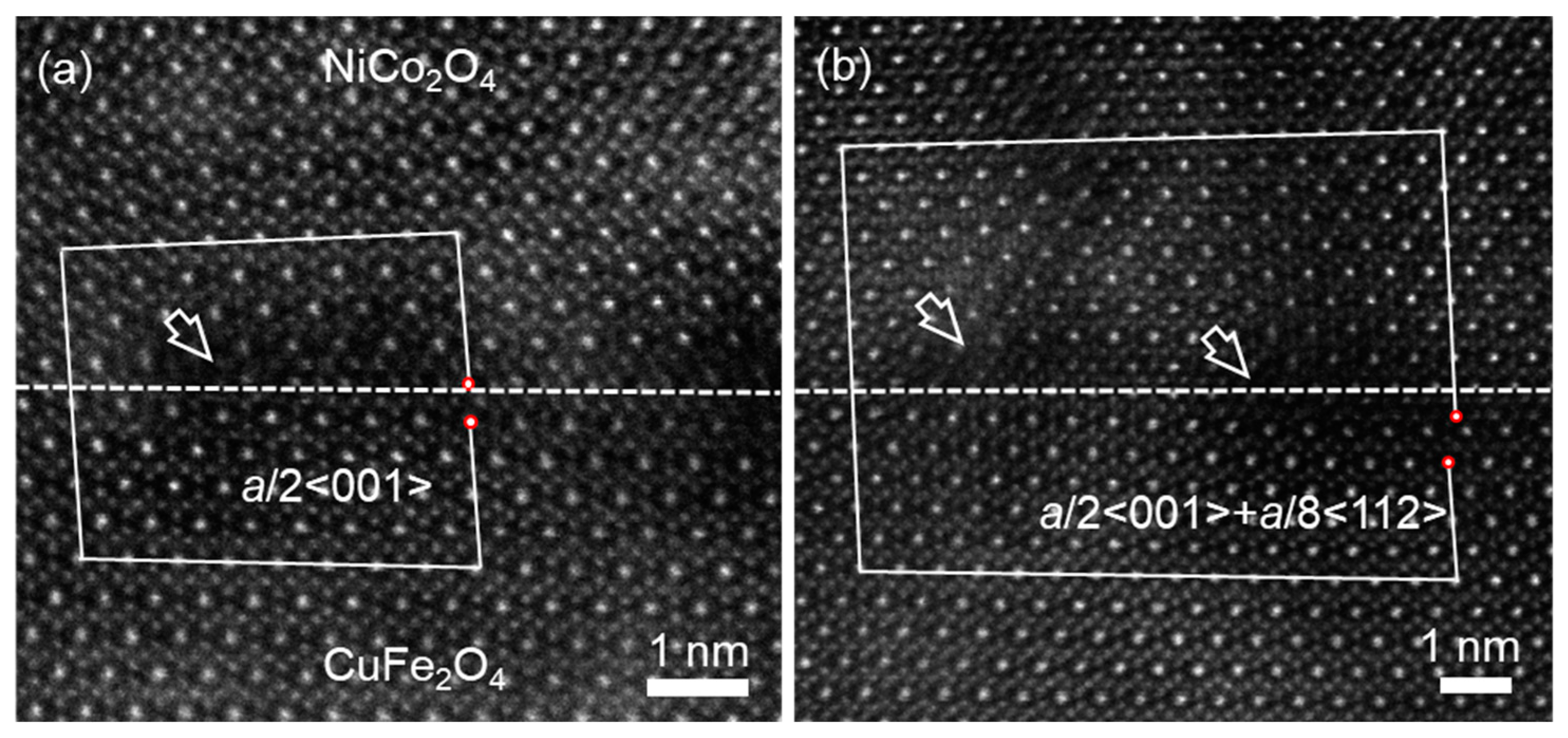

Figure 7(a) displays an atomic-resolution HAADF image of the NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) interface, recorded along the [1

0] zone axis of the MAO substrate, showing the existence of interfacial dislocations. Performing a Burger circuit around the isolated misfit dislocation core leads to a projected displacement vector of

ac/2<001>. It is obvious that dislocation core, marked by the white arrow, is located inside the NCO film near the interface. In addition, another kind of interfacial dislocation with the projected displacement vector of

ac/2<001>+

ac/8<112> was observed at interface shown in

Figure 7(b), acquired by the Burger circuit containing two dislocation cores, one core located inside the NCO film adjacent to the interface and another core located at the interface, as indicated by two white arrows in

Figure 7(b). It should be noted that these two dislocations neither does not further lead to the formation of APBs in two films, which is different from that in NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm)/MAO heterostructure. The formation of interfacial dislocation contributes to relaxation of epitaxial mismatch strain between NCO and CFO film.

Two NCO/CFO/MAO heterosystems with different film thickness were prepared under the same deposition condition. Different microstructural defects are generated inside and at the interface of the two films due to the different thickness of the upper film NCO.

In NCO/CFO bilayer heterostructure, the in-plane lattice mismatch between NCO and CFO materials is calculated to be −2.59% by using (

aN−

aC)/

aC*100%, where

aN and

aC are the parameters of bulk NCO and CFO materials, respectively. The formation of both interfacial dislocations and APBs within the film in the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterostructure contribute to epitaxial strain relaxation from lattice mismatch more effectively than that in NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterostructure. In some case, the misfit dislocations are nucleation sites of the APBs in the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterostructure. This means that the density of the APBs in the film depends on the density of the misfit dislocations. It is well known that the strain state in the heterosystem can be affected by the thickness of the films [

33], as a result, the density of the misfit dislocations and the formation of APBs changes with the film thickness, which is demonstrated that the density of interfacial dislocation in the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterosystem is greater than that in the NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterosystem and APBs form in the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) rather than NCO (10 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterosystem. Moreover, the edge-on APBs and non-overlapping APBs in the NCO (40 nm)/CFO (40 nm) heterostructure both exhibit antiferromagnetic coupling, which would affect the ferromagnetic properties of the films. Accordingly, atomic-scale structural properties including the formation of APBs in the heterostructure could be tuned by the film thickness, which may allow further manipulating the magnetic properties of films.