1. Introduction

The first millennium BC marks a moment of significant cultural and socio-economic changes that ultimately led to the emergence of early forms of urban life in the Tagus Estuary (Arruda 1999-2000). Our understanding of this period has seen notable progress in recent years, allowing us to expand our comprehension of the profound transformations that followed the arrival of Phoenician populations in the region on the 8th century BC, according to conventional chronology (Arruda 2015; Soares & Arruda 2017). In the context of the arrival of these exogenous groups, a new regional reality took shape, leading to a series of changes in material culture and productive practices that seemed to be well consolidated by the 7th century BC. Several factors illustrate this situation, including the development of wheel-pottery production in the Lower Tagus, which emerged between the 8th century and the early 7th century BC and witnessed a progressive intensification and diversification throughout the Iron Age (Sousa 2014).

The advent of the potter's wheel, coupled with advanced kilns that ensured precise temperature control and predominantly oxidizing firing atmospheres, led to a significant upswing in ceramic production (Mielke 2015). In contrast to preceding moments, the focus of production now shifts towards commercialization, primarily at a regional level, although supraregional trade is also attested. Furthermore, the new technologies allowed the development of a wide range of formal styles and unprecedented aesthetic finishes. The new ceramic corpus, which includes storage containers, transport vessels, tableware, and everyday ceramics, exhibits a notable degree of standardization and consistency, spanning the entire southern region of the Iberian Peninsula (Groot 2021).

Nevertheless, concrete evidence regarding production contexts in the Tagus Estuary is currently limited and, as of now, no identifiable production center has been pinpointed. A few isolated structures possibly linked to a low scale ceramic production were, however, already identified, namely the Miroiço kiln in the Cascais area (Cardoso & Encarnação 2013) and the Rua dos Correeiros structure, in Lisbon central area (Sousa 2014). In addition to these elements, the presence of objects referred to as "ceramic prisms" suggests the existence of additional production areas along the Tagus Estuary. These artifacts, designed for tasks related to the drying and firing phases - specifically, stabilizing and separating ceramic objects - are well documented in the Tagus estuary. Examples include findings at Quinta da Marquesa II in Vila-Franca de Xira (Pimenta e Mendes 2010/2011) and, precisely, in Almaraz.

Given the limited number of data available, analytical approaches, especially those rooted in systematic studies of ceramic assemblages, become particularly important for characterizing ceramic production (Tite 2008). These approaches enable the identification of the origins of the manufactures and the reconstruction of various aspects of production, such as raw material selection, treatment methods, composition of surface decorations, and firing temperature, which contribute to a deeper understanding of the technical developments associated with this period.

Previous compositional studies of pottery ceramic pastes, clay raw materials, and firing experiments enabled us to establish a limited number of clay sources and formulations for the Phoenician potteries found at S. Jorge Castle and amphorae from Almaraz archaeological site (Vieira Ferreira et al 2020a,b, 2018, 2015). Pliocene ceramic pastes (highly siliceous) or Miocene ceramic pastes (with a high content of calcium carbonate) were detected. Potters settled preferentially in vicinity areas with clayey soils. We could corroborate the identification of the sources of clay with the presence of archaeological finds existing in their closeness.

One should emphasize that in the Lisbon region, Miocene clays can be found in the North and South of the Tagus River, while Pliocene clays only exist on the South bank (Lepierre 1899; Vieira Ferreira et al. 2018, 2015; Zbyszewski 1963).

The systematic study of the ceramic assemblage from the Quinta do Almaraz archaeological site, conducted as part of a multi-annual research project, has yielded analytic data that provides further insights into the characterization of this local and regional ceramic production. It is precisely these new data that will now be presented in detail.

2. Archaeological Context and Framework

The settlement of Quinta do Almaraz is located in a long spur on the left bank of the Tagus mouth, opposite to Lisbon. Discovered in 1986, the site saw an initial phase of archaeological research conducted until 2001 (Barros & Henriques 2002). This was followed by a period of limited research activity, which was only resumed with the start of the project named Proj.In.QA, in 2020.

The assortment of artifacts recovered through the excavations distinctly emphasizes the Phoenician cultural imprint on the site. This influence is evident through the presence of characteristic ceramic types from this period, such as red slip and grey ware, pithoi, Cruz del Negro type urns and amphorae. Furthermore, the architectural features provide additional validation of this influence, manifesting in the layout of domestic structures, construction techniques, and the defensive system, all exhibiting a visible Mediterranean influence (Olaio et al. 2020).

Almaraz as played a crucial role in the economic and commercial framework of the Tagus estuary, reality that is substantiated by a notable collection of imported artifacts such as the Egyptian scarab, alabaster vases, ivory plaques and Middle Corinthian ceramic fragments (Cardoso 2004; Arruda 2005), as well as by the set of lead weights, some of which affiliated with the oriental measurement system (Vilaça 2011). Moreover, evidence strongly suggests that the settlement served as an important center for metallurgical production (Melo et al. 2014), which, along with other production activities indicated by a diverse range of artifacts, such as pottery, weaving, and fishing implements, underscores the economic importance of the settlement during the Iron Age (Olaio 2020).

Based on the available data, it is evident that the settlement of Almaraz came into existence between the latter part of the 8th century BC and the early 7th century BC, experiencing a significant phase of growth around the 6th century BC. However, this scenario underwent a shift at some point during the 5th century BC, marked by a progressive decline in the settlement’s vitality. This transition was reflected in various ways, including the deactivation of the defensive structure and the abandonment of the residential area adjacent to the river (Olaio et al. 2019).

Until recently, most of the ceramic set of Almaraz remained unknown, with only the amphorae set having undergone a complete comprehensive study (Olaio 2018), which was further subjected to an archaeometric approach (Vieira Ferreira

et al. 2018). However, within the scope of the new research project, it has been possible to conduct a detailed study and categorization of the entire ceramic set, which includes common ware, red slip ware, painted ware, grey ware, and hand-made pottery. It is precisely these ceramic categories that form the focus of the archaeometric analyses presented in this paper -

Figure 1.

3. The Ceramic Sample Set – Selection Methodology

The selection process began with a comprehensive macroscopic analysis of the various ceramic categories identified in Almaraz. The goal was to delineate the productive and technical diversity inherent to each category and subsequently propose preliminary Manufacturing Groups (MG).

To this end, we applied a set of criteria established within the realm of ceramic studies for macroscopic characterization of MGs (Picon 1973; Almeida 2008). These criteria encompassed factors such as the nature of the clay material, the color of both the external and interior surface, the appearance of the production in terms of hardness and texture, the frequency of inclusions, the presence of voids and cracks, as well as the firing technique.

These first observations led us to the identification of eight MGs for red slip ware, four MGs for painted pottery, four MGs for yellow slip pottery, six MGs for grey ware, four MGs, five MGs for common ware and for hand-made pottery. From these groups, specific samples from different contexts were chosen for the current analysis. Additionally, samples of coating techniques, specifically red-slip and yellow slip engobe surfaces, were also subjected to archaeometric analysis.

4. Experimental Techniques under Use

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted utilizing a Panalytical X’ PERT PRO diffractometer system equipped with a copper source. This method furnishes essential insights into the mineralogical and phase composition of the ceramic body of the sherds or raw materials. Micro-Raman investigations were carried out employing a Renishaw InVia Confocal Raman equipment in a back scattering configuration, using a 532 nm laser excitation. For elemental composition information on the studied pastes, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyses were performed using a Niton XL3T GOLDD spectrometer from Thermo Scientific. Ground state diffuse reflectance absorption spectra spectroscopy (GSDR) experiments were conducted employing a custom-built diffuse reflectance set-up, incorporating three standards: Spectralon white and grey disks, and barium sulfate powder.

Further details regarding all these techniques were described in previous publications (Vieira Ferreira et al 2015, 2018, 2020a,b).

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. XRD Studies

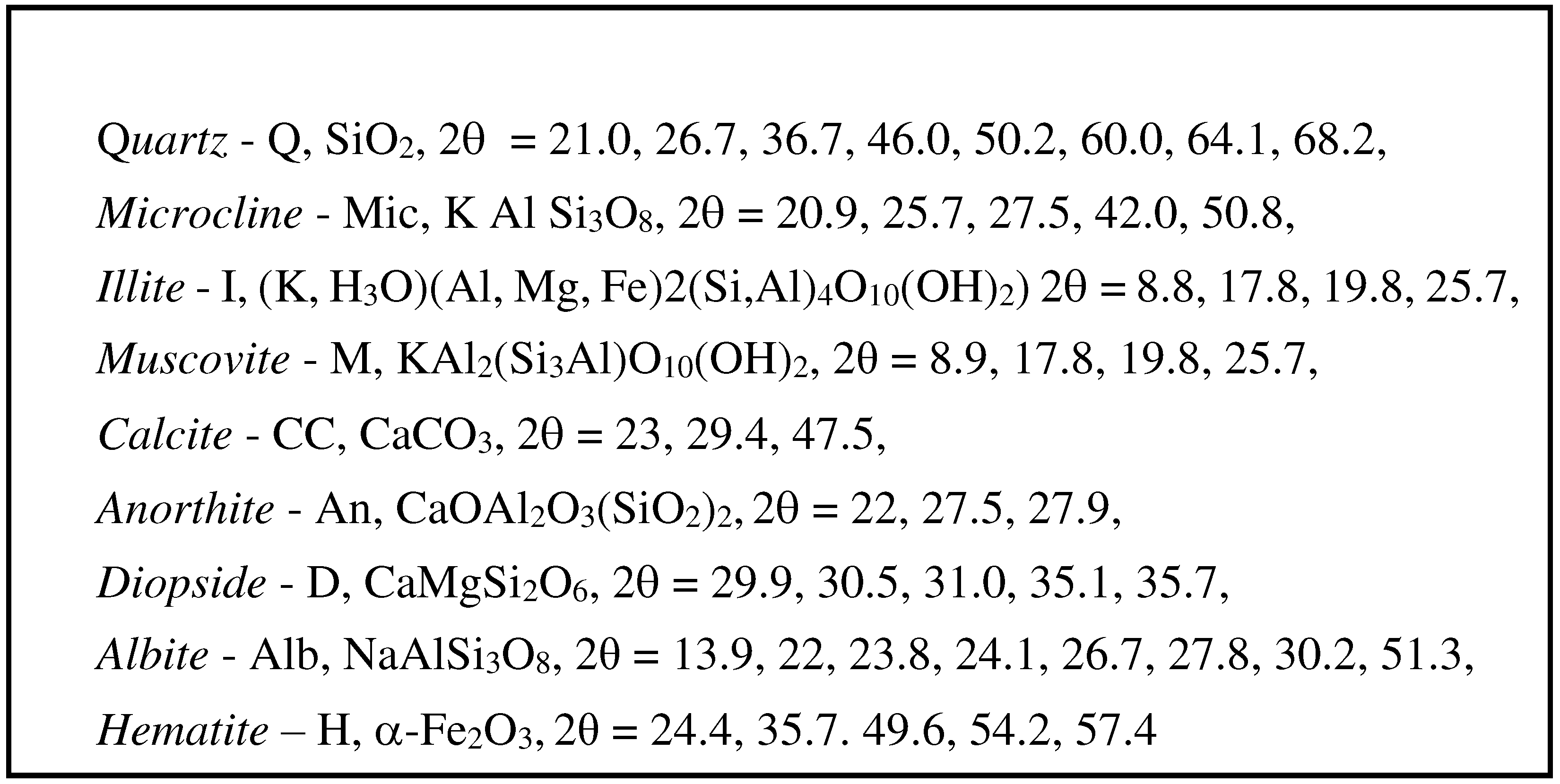

Ceramic bodies of the pottery recovered from the Almaraz archaeological site were grouped in two main types (

Figure 2). XRD diffractograms enabled us to establish the main characteristics of each type. The main XRD peaks observed for each sample are presented in

Table 1.

The Pliocene type pastes exhibit

quartz (Q),

albite (Alb) a sodium alumino silicate and

microcline (Mic) a potassium alumino silicate, (see

Figure 2), consistent with the use of high siliceous Pliocene clays as raw materials.

Muscovite (M) was also detected, and we must point that muscovite and illite diffractograms are indistinguishable. Nowadays it is still possible to collect the Pliocene clays in the surrounding areas of Almaraz. The presence of muscovite in the ceramic body shows that the firing temperatures inside the kiln did not exceed 850ºC, because above that value all muscovite (or illite) becomes unstable (Vieira Ferreira et al. 2020a,b 2018).

The third diffractogram in

Figure 2 exhibits a considerable amount of calcium carbonate. Again, it is possible to collect some clays in the left margin of the Tagus River that exhibit a Pliocene pattern but also include a large amount of calcium carbonate (calcite). Despite being less typical, these clays exhibit a Pliocene XRD pattern.

Now we should mention that very similar diffractograms were obtained in a previous study of red slip ware from the archaeological site of São Jorge Caste (samples R1 to R5 in the paper ref. Vieira Ferreira et al. 2020a). This means that most probably the workshops that produced this Phoenician pottery were located at Almaraz, since these Pliocene clays do not exist in the right margin of Tagus River. No traces of kilns were found at Almaraz thus far, but some trivets of triangular section were recovered from local pits, pointing to the existence of local workshops with kilns at Almaraz.

Palença type pastes were produced with clays of Miocene origin from sources located in the left margin of the Tagus River. These ceramic bodies have complex diffractograms, as

Figure 2 shows.

Quartz is the major mineral component, and

anorthite (An), a calcium alumino-silicate, is the second major component and appears as a typical fingerprint of the Palença ceramic bodies. The absence of calcite (CC) and the presence of D

iopside (D), a calcium and magnesium silicate, implies T

f ≥ 850ºC (Porras et al. 2012, Vieira Ferreira et al. 2020a). Diopside formation implies the existence of magnesium in the raw materials. Anorthite´s formation needs very high firing temperatures in the kiln (above ~900ºC - 950ºC) together with a long-lived firing (Vieira Ferreira et al. 2020a; Porras et al. 2012).

Samples RS1 to RS8, DC1 to DC4, G1 to G6, H1 and H4, C1 to C3 have siliceous pastes (Pliocene) while samples YS 1 to YS4, H2 and H3, and C5 are Palença (Miocene) type. Sample C4 exhibits a different diffractogram, not presented in

Figure 2, was produced in Lisbon workshops as can be seen in previously published diffractograms (Vieira Ferreira et al. 2018).

5.2. XRF Studies

The XRF results achieved for the ceramic bodies of sherds from the Almaraz archaeological site are presented in

Table 2.

Scatterplots for K/Si versus Ca/Si (% wt ratio) for all sherds (

Figure 3) clearly exhibits two groups: Pliocene type sherds, with low calcium content and Miocene type sherds with a much higher calcium content. Only one sherd is separated from these two groups, the sherd from tableware produced in Lisbon workshops, the one with the highest calcium content. The ratio, R, defined by:

was used in previous papers of our group (Vieira Ferreira et al. 2015, 2018, 2020a,b), to quantify the relative amounts of the structural components of the ceramic pastes, (SiO

2 + Al

2O

3 + K

2O), related to calcium fractions (CaO).

The plot in

Figure 3, allows us to view the differences between the ceramic bodies with clays of Pliocene origin (highly siliceous and calcium depleted, in most cases) in which the R parameter is very high (R= 10 to 70 – blue ellipse) (Vieira Ferreira et al. 2020a,b). Palença ceramic bodies produced with Miocene clays that show much smaller R values: R=5 to 10 (red ellipse). The Lisbon (C4) sample exhibits R=3. The compositional profile of decorative ceramics shows very low compositional variability, revealing the careful selection of raw materials and the manufacturing process. In contrast, handmade and common ceramics exhibit the maximum dispersion of values in certain chemical components, indicating a less careful and demanding use (

Table 2).

5.3. Micro-Raman Studies

Micro-Raman spectroscopy is an excellent technique to identify the compounds used to decorate the surface of the ceramic or the engobes. In the case of the red slip tableware the red colour is due to the use of hematite (H, α-Fe

2O

3) associated with brookite (TiO

2). All the red ware ceramics were made with Pliocene clays, highly siliceous, so is not a surprise that we could detect quartz in all samples. Also, the red engobe exhibit anatase (TiO

2) and carbon black in the darker surfaces. One should also mention that in some special cases, a remarkable amount of calcium carbonate was detected, as shown in

Figure 2 and also in the fifth curve of

Figure 4 a).

The major differences in the Raman in the case of the decorated ceramics (Part b) of

Figure 4) is that part of the surface is decorated, and another part is not. In the black stripes, the potters used the mineral jacobsite (Mn

2+Fe

3+2O

4), in the red stripes hematite and albite (NaAlSi

3O

8,) could be detected. Non-surprisingly anatase, quartz and albite/feldspar were detected in the non-coloured surface.

All yellow slip tableware sherds were obtained with the use of a yellow clay engobe (

Figure 4 c)). So, the Raman spectra reflect the mineralogical composition of this engobe, of siliceous nature in two samples (YS1 and YS2 – the first four curves) and also the Miocene nature of the ceramic bodies (YS3 and YS4 samples), where anorthite is abundant – fifth curve. Anorthite was observed in the parts of the sherds that are nor covered with the engobe.

Grey and Common Tableware Raman spectra are presented in part d) of

Figure 4. No engobe exist in these two groups of ceramics, so the Raman reflect the ceramic body composition of the siliceous pastes, with a major difference: huge amounts of carbon black is present in the grey tableware, which reflects the reductive conditions of the firing process inside the kiln.

Handmade Tableware - Anorthite exists in the Palença type sherds H2 and H3 (of Miocene origin). The other curves of part e) of

Figure 4 reflect the siliceous nature of the other two samples.

5.4. GSDR Studies

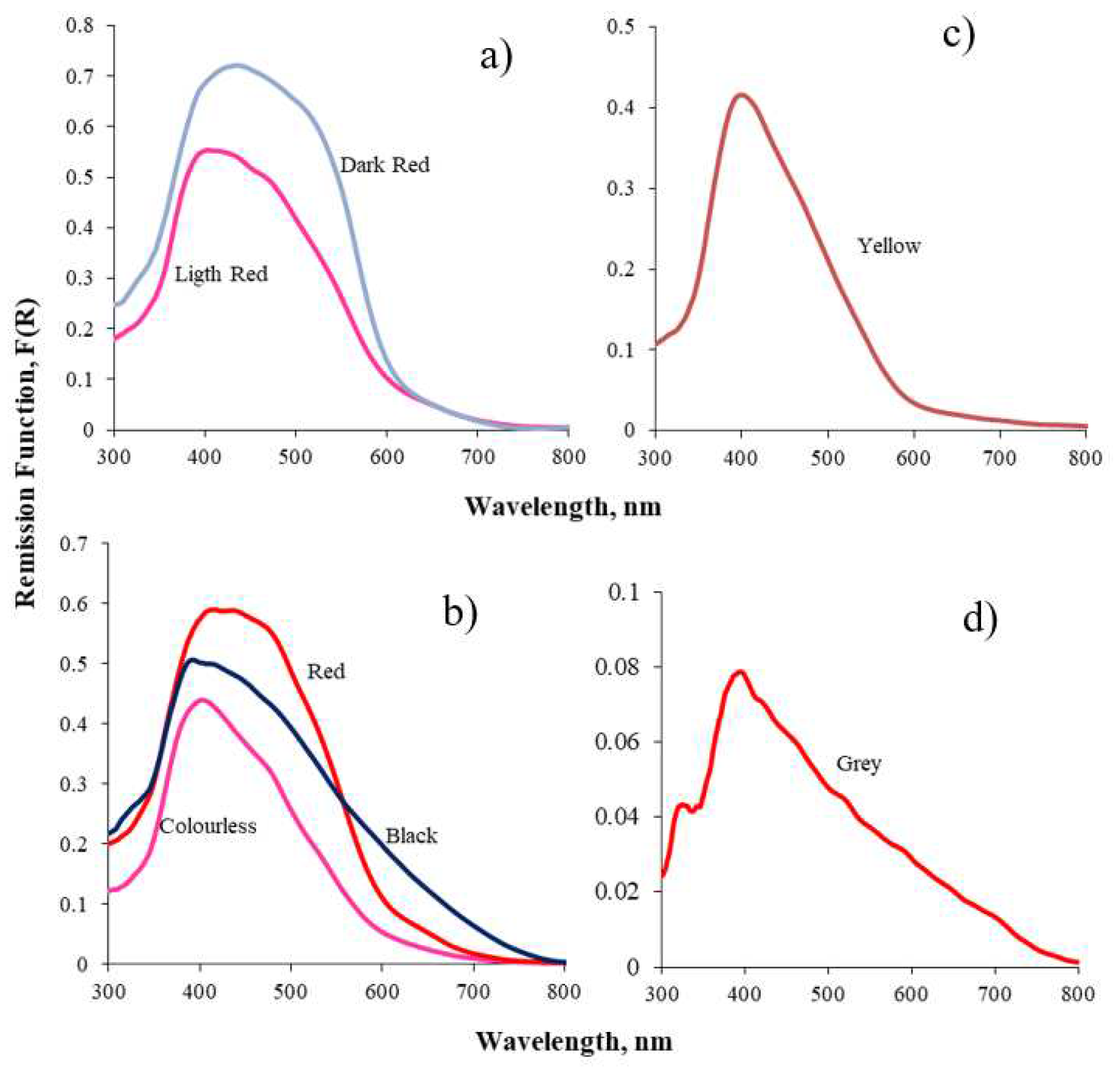

Ground state diffuse reflectance absorption spectra for all coloured samples in

Figure 1 are presented in

Figure 5, where the Remission Function is presented as an ordinate and the wavelength in nm is the abscissa. Part a) of

Figure 5 shows the absorption spectra of the red slip ware. The absorption of red maximizes at ca. 530 nm which is the green colour, the complementary colour of red. This absorption is larger in the dark red when compared with the light red.

Part b) of

Figure 5 presents the three colours, which exist in the surface of the decorated ceramics:

The red curve is similar to the one of part a) and a clear distinction can be observed for the colourless surface, which maximizes its absorption in the UV range at about 400 nm. This contrasts with the black absorption which is broad in all the wavelength range under study. Yellow tableware (Part c) shows the engobe which covers all the ceramic body and absorbs in the blue region, so it appears as a yellow surface. Finally, the grey absorption (Part d) is similar to the black curve of the decorated ceramic.

6. Conclusions

The mineralogical study of the pastes of all ceramic fragments found at Almaraz show two main types of pastes. The largest group were made with Pliocene clays collected south of the Tagus River, usually presenting a very low calcium content. In this case the dominant minerals detected in the diffractograms were quartz, microcline, and albite. The second group, also produced in local workshops used Miocene clays from Palença clay sources. Quartz, diopside and anorthite were detected as dominant mineral components of the second group.

Micro-Raman studies of the surfaces of the sherds revealed that for the red tableware engobe colour due to the use of hematite (H, α-Fe2O3) associated with brookite (TiO2). For the decorated ware the black stripes evidence the use of a manganese mineral, jacobsite and the red stripes evidence hematite. For the yellow slip group, the engobe is a yellowish clay and for the grey tableware the siliceous ceramic body evidences a high content of carbon black, entrapped into the ceramic body in the firing process in reductive conditions. The surface colour of the handmade and common wares varies with the origin of the raw materials used in each specific case.

Regarding the red pigment, with the association of hematite and brookite, its existence/production in the Lisbon region can be considered hypothetical, depending on terra rossa or levels of alteration of volcanic rocks. However, the black pigment, consisting of the manganese oxide jacobsite, does not occur in the geological formations of this region; therefore, its origin must be considered external. Despite the presence of various mineral deposits with manganese oxides exposed in Portuguese territory, especially in the South of Portugal, the origin of this type of pigment cannot be established now. Subsequent comparative studies with samples of ores and artifacts from various sources may help clarify this matter.

Our studies of the mineralogic composition of the sherds` body indicate that all ceramics were produced in local kilns, mostly located south of Tagus River.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to FCT, Portugal, for the funding of projects UID/NAN/50024/2019, UIDB/04028/2020 and M-ERA-MNT/0002/2015. A.O. is funded through doctoral scholarship from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (SFRH/BD/146563/2019).

References

- Almeida, R. Las Ánforas del Guadalquivir em “Scallabis” (Santarém, Portugal): uma aportación al conocimiento de los tipos minoritários. Colección Instrumenta 2008, 28. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona.

- Arruda, A. Los fenicios en Portugal: Fenicios y mundo indígena en el centro y sur de Portugal (siglos VIII-VI a.C.). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra 1999-2000.

- Arruda, A. O 1º milénio a.n.e. no Centro e Sul de Portugal: Leituras possíveis no início de um novo século. O Arqueólogo Português 2005, 4-5: 9-156.

- Arruda, A. A Idade do Ferro Orientalizante no vale do Tejo: as duas margens de um mesmo rio. In Celestino Pérez, S., Rodríguez González, E. (coord.), Territorios comparados: los valles del Guadalquivir, el Guadiana y el Tajo em época tartésica, Mérida 2015, 283-294.

- Barros, L., Henriques, F. Almaraz, primeiro espaço urbano em Almada. In Henriques, F.; Santos, M.; António, T. eds., Actas do 3º Encontro Nacional de Arqueologia Urbana. Almada: Câmara Municipal de Almada. Divisão dos Museus - Núcleo de Arqueologia e História 2002, 295-311.

- Cardoso, J. A Baixa Estremadura dos finais do IV milénio A. C. até à chegada dos romanos: um ensaio de História Regional, Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras 2004, 12, Oeiras.

- Cardoso, G. & Encarnação, J., O povoamento pré-romano de Freiria - Cascais. Cira Arqueologia 2013, 2, 133-180.

- Curià, E., Delgado, A., Fernández, A., & Párraga, M., La organización de la producción de cerámica en un centro colonial fenicio: El taller alfarero del siglo VI a.n.e. del Cerro del Villar. In M. BarthélemyAubet (eds.), Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos (Cádiz, 2 al 6 de Octubre de 1995. Universitat de Cádiz/Servicio de Publicaciones 2000, 1475-1485.

- Gutiérrez López, J., Sáez Romero, A., & Reinoso del Río, M., La tecnología alfarera como herramienta de análisis histórico: reflexiones sobre los denominados "prismas cerámicos". SPAL 2013, 22, 61-100.

- Groot, B., Material Methods; Considering Ceramic Raw Materials and the Spread of the Potter‘s Wheel in Early Iron Age Southern Iberia. Interdisciplinaria Archaeologica, XII 2021, 2, 331-342. [CrossRef]

- Lepierre C. Estudo Chimico e Technologico sobre a Cerâmica Portuguesa Moderna. Imprensa Nacional 1899, Lisboa.

- Melo, A., Valério, P., Barros, L., Araújo, M. Práticas metalúrgicas na Quinta do Almaraz (Cacilhas, Portugal): vestígios orientalizantes. In Arruda, A. M. (ed.), Fenícios e Púnicos, Por Terra e Mar. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos Fenícios e Púnicos, Lisboa 2014, 698-711.

- Mielke, D., Between transfer and interaction: Phoenician pottery technology on the Iberian Peninsula. In W. Gauss, G. Klebinder-Gauss & C. von Rüden (eds.), The transmission of technical knowledge in the production of ancient mediterranean pottery, Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut, 2015, 257-276.

- Pimenta, J. & Mendes, H., Novos dados sobre a presença fenícia no Vale do Tejo. As recentes descobertas na área de Vila Franca de Xira. Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras, 2010/2011, 18, 591-618.

- Simsek G, Casadio F, Colomban Ph, Bellot-Gurlet L, Faber KT, Zelleke G, Milande V, Moinet E. On-site identification of early Böttger red stoneware made at Meissen using portable XRF: 1, body analysis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc 2014, 97:2745-2754.

- https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.13032. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.,Arruda, A. Cronologia de radiocarbono para a Idade do Ferro Orientalizante no território português. Uma leitura crítica dos dados arqueométricos e arqueológicos. In Barcleó, J., Bogdanovic, I. e Morell, B. (eds.), IberCrono 2016 Cronometrías Para la Historia de la Península Ibérica (Chronometry for the History of the Iberian Peninsula) - Actas del Congrso de Cronometrias para la Historia de la Península Ibérica, Barcelona, 17-19 de octubre 2016, Barcelona 2017, 235-259.

- Sousa, E. A ocupação pré-romana da foz do Estuário do Tejo. Estudos & Memórias 7 2014. Lisboa: Uniarq – Centro de Arqueologia da Universidade de Lisboa.

- Tite, M., Ceramic production, provenance and use – a review. Archaeometry 2008, 50 (2), 216-231. [CrossRef]

- Olaio, A. O povoado da Quinta do Almaraz no âmbito da ocupação do Baixo Tejo durante o 1º milénio a.n.e.: os dados do conjunto anfórico., Spal 2018, 27-2: 125-163. [CrossRef]

- Olaio, A. Economia, produção e comércio na Quinta do Almaraz (Almada, Portugal) durante o 1º milénio a.n.e. – balanço e perspectivas de investigação. In Celestino Pérez, S. e Rodríguez González, E. (eds.) Actas IX Congreso Internacional de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos, MYTRA 5, Mérida 2020, 1375-1388.

- Olaio, A., Angeja, P., Soares, R., Valério, P. A ocupação da Idade do Ferro de Cacilhas (Almada, Portugal).”, Onoba 2019, 7: 133-159. [CrossRef]

- Picon, M.- Introduction a l’Étudie Technique des Ceramiques Sifillèes de Lenzou: Centre de recherches sur techniques fréco-romaines. Dijon: Université de Dijon 1973.

- Vieira Ferreira LF, Sousa E. De, Pereira MFC, Guerra S, Ferreira Machado I. An archaeometric study of the Phoenician ceramics found at the São Jorge Castle's hill in Lisbon. Ceram Intern 2020a, 46, 7659-7666. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira LF, Barros L, Ferreira Machado I, Pereira MFC, Casimiro TM. An archaeometric study of a Late Neolithic cup and coeval and Chalcolithic ceramic sherds found in the São Paulo Cave, Almada, Portugal. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2020b, 51, 483-492.

- https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.5802. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, LF, Barros, L., Machado, I., Gonzalez, A., Pereira, M., Casimiro, T. Spectroscopic characterization of amphorae from the 8th to the 7th c. BCE found at the Almaraz settlement in Almada, Portugal. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2018, 21: 166-174. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira LF, Gonzalez A, Pereira MFC, Santos LF, Casimiro TM, Ferreira DP, Conceição DS, Ferreira Machado I. Spectroscopy of 16th century Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware produced in the region of Lisbon. Ceram Intern. 2015, 41, 13433–13446. [CrossRef]

- Vilaça, R. Ponderais do Bronze Final-Ferro Inicial do Ocidente peninsular: novos dados e questões em aberto. In García-Bellido, M.P. e Jiménez Díez, A. (eds.), Barter, Money and Coinage in the Ancient Mediterranean (10th-1st centuries BC), Anejos de AEspA 2011, LVIII: 139-167.

- Zbyszewski G. Carta Geológica dos Arredores de Lisboa na escala 1/50 000 – notícia explicativa da folha 4 – Lisboa 1963. Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisboa.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).