Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

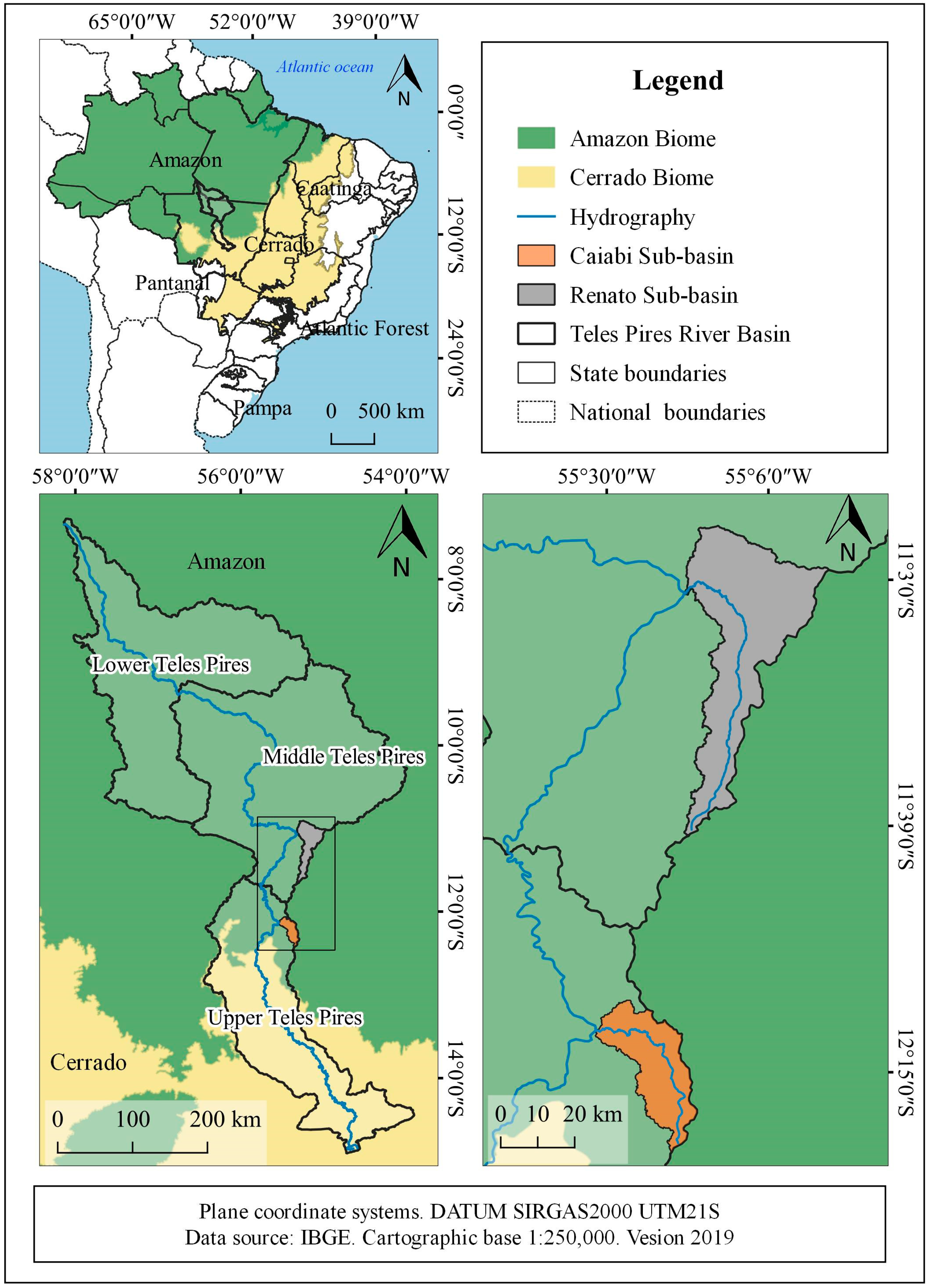

2.1. Study area

2.2. Treatments and experimental organization

2.3. Soil water infiltration models

2.4. Statiscal analyses

3. Results

3.1. Physical characterization of the soil

3.2. Initial and final infiltration rate

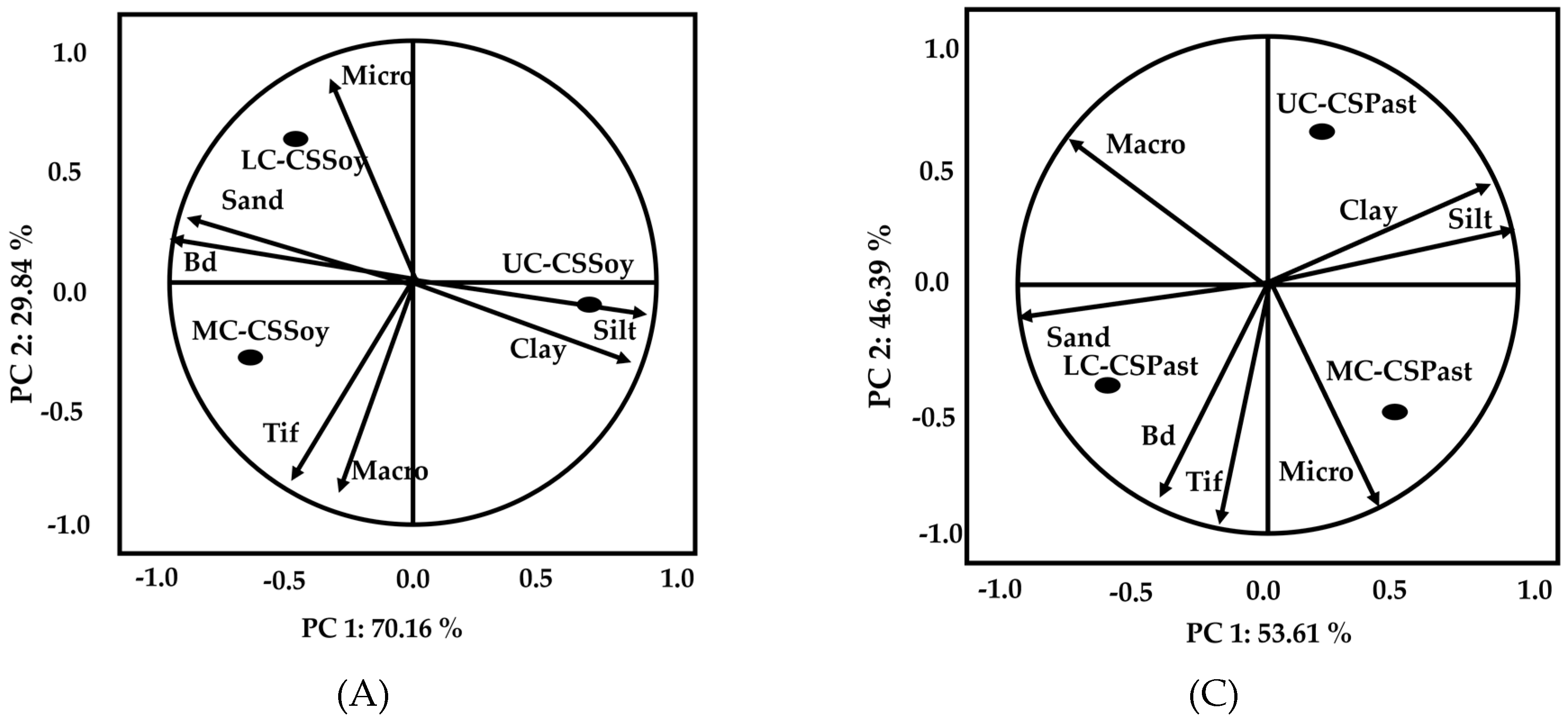

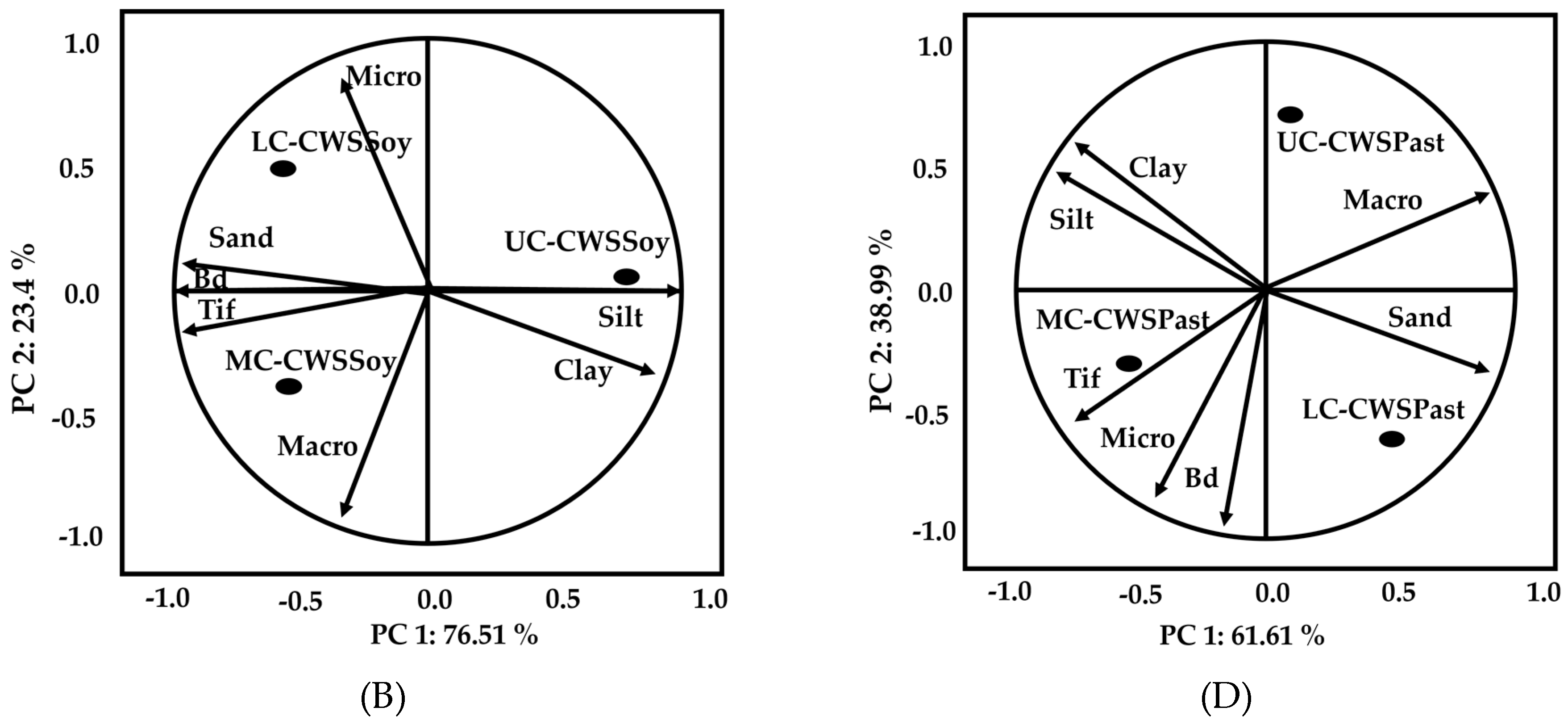

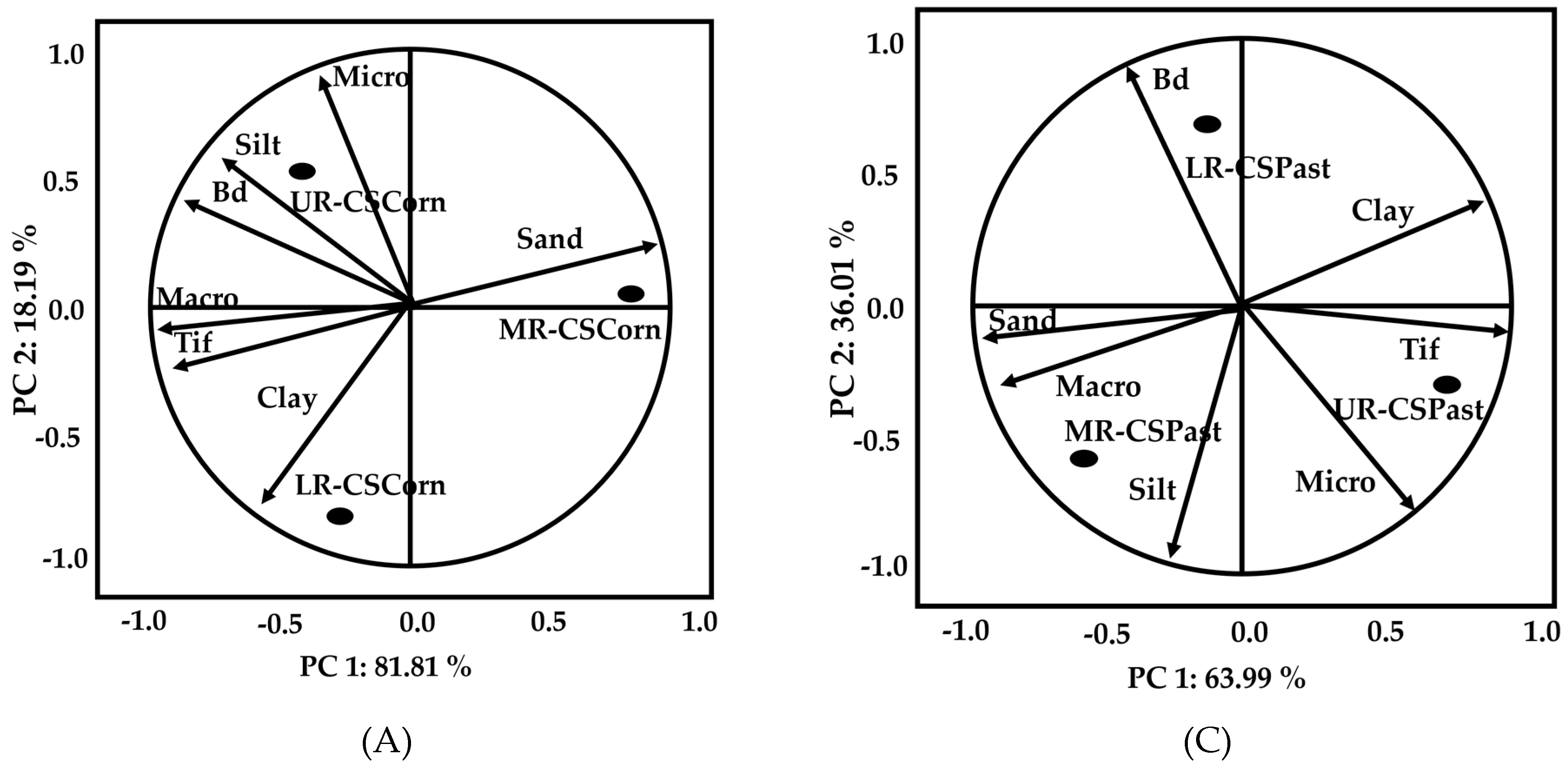

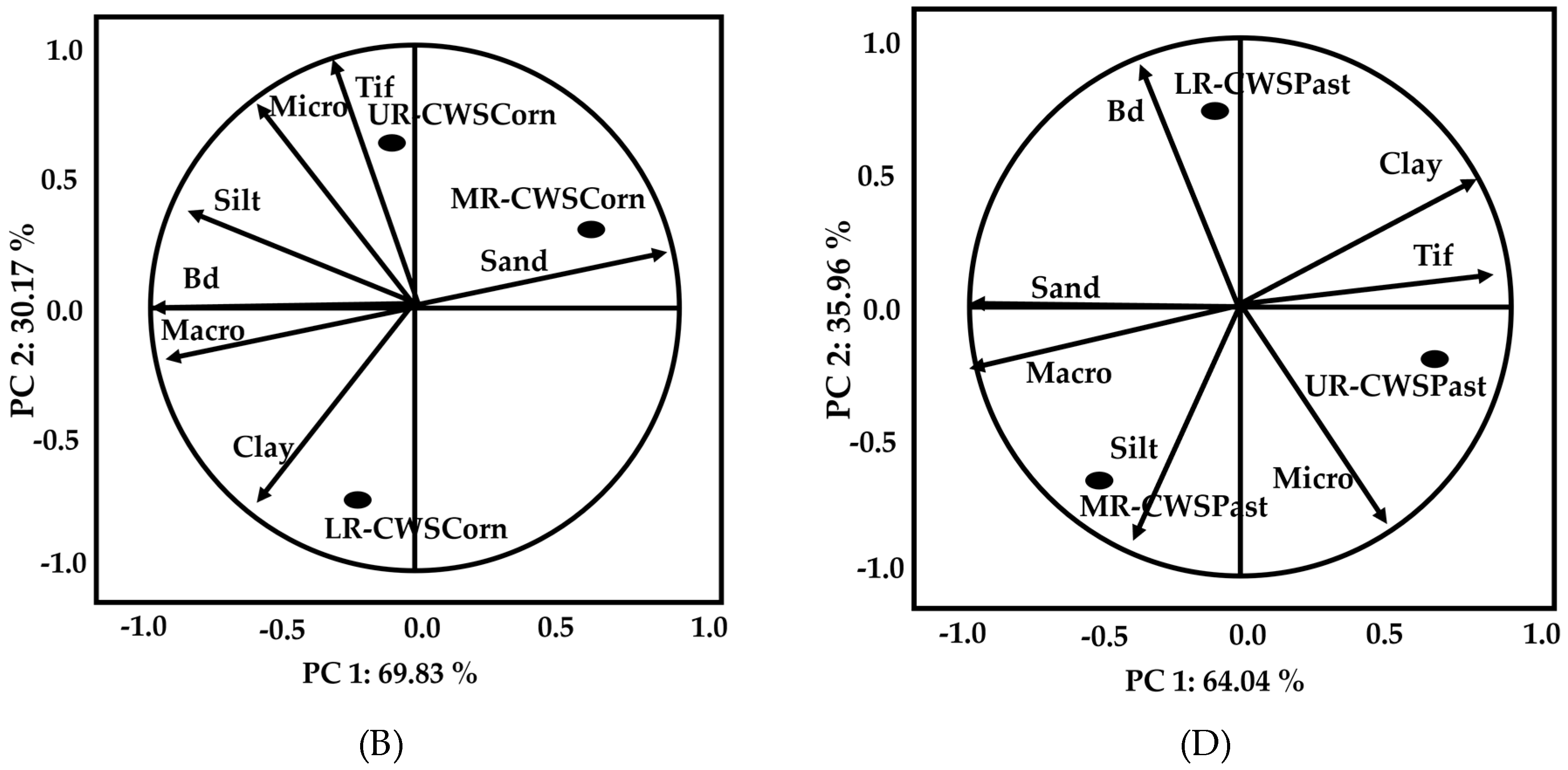

3.3. Principal component analysis (PCA)

| Principal component | CCSSoy | CCSPast | CWSSoy | CWSPast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | |

| Eigenvalues | 4.910 | 2.080 | 3.750 | 3.240 | 5.350 | 1.640 | 4.310 | 2.680 |

| Variation % | 70.160 | 29.830 | 53.610 | 46.390 | 76.510 | 23.490 | 61.600 | 38.390 |

| Attribute | Correlation | |||||||

| Sand | -0.984* | 0.178 | -0.258* | -0.076 | -0.999* | 0.051 | -0.186* | 0.031 |

| Clay | 0.956* | -0.295 | 0.254* | 0.092 | 0.985* | -0.170 | 0.184 | -0.104 |

| Silt | 0.993* | -0.121 | 0.264* | 0.040 | 0.990* | 0.007 | 0.187* | 0.004 |

| Micro | -0.274 | 0.962* | 0.135 | -0.265* | -0.395 | 0.919* | -0.074 | 0.559* |

| Macro | -0.609 | -0.794 | -0.205 | 0.197 | -0.502 | -0.865* | -0.094 | -0.526* |

| Bd | -0.991* | 0.130 | -0.072 | -0.2966* | -0.990* | 0.003 | -0.187* | 0.002 |

| Rif | -0.785* | -0.620 | -0.004 | -0.308* | -0.990* | -0.144 | -0.185* | -0.088 |

| Principal component | RCSCorn | RCSPast | RWSCorn | RWSPast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 1 | PC 2 | |

| Eigenvalues | 5.720 | 1.270 | 4.47 | 2.520 | 4.880 | 2.110 | 4.480 | 2.510 |

| Variation % | 81.810 | 18.190 | 63.990 | 33.010 | 69.830 | 30.170 | 64.030 | 35.960 |

| Attribute | Correlation | |||||||

| Sand | 0.975* | 0.223 | -0.984* | -0.177 | 0.930* | 0.367 | -0.728* | -0.068 |

| Clay | -0.821* | -0.570 | 0.938* | 0.347 | -0.726 | -0.688 | 0.638* | 0.176 |

| Silt | -0.936* | 0.352 | -0.242 | -0.970* | -0.978* | 0.207 | -1.116 | -3.260* |

| Micro | -0.528* | 0.849 | 0.629 | -0.777 | -0.650 | 0.760 | 15.968* | -23.576 |

| Macro | -0.996* | -0.092 | -0.971* | -0.237 | -0.971* | -0.241 | -49.408* | -7.670 |

| Bd | -0.989* | 0.150 | -0.485 | 0.874* | -0.990* | -0.001 | -3.593 | 8.025* |

| Rif | -0.989* | -0.150 | 0.999* | -0.052 | -0.417 | 0.909* | 0.089 | –0.003 |

3.4. Infiltration models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rápalo, L.M.C.; Uliana, E.M.; Moreira, M.C.; Da Silva, D.D.; De Melo Ribeiro, C.B.; Da Cruz, I.F.; Dos Reis Pereira, D. Effects of land-use and-cover changes on streamflow regime in the Brazilian Savannah. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2021, 38, e100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertol, I.; Barbosa, F.T.; Berto, C.; Luciano, R.V. Water infiltration in two cultivated soils in Southern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2015, 39, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, W.S.; Panachuki, E.; De Oliveira, P.T.S.; Da Silva Menezes, R.; Alves Sobrinho, T.; De Carvalho, D.F. Effect of soil tillage and vegetal cover on soil water infiltration. Soil and Tillage Research 2018, 175, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunke, P.; Roller, R.; Zeilhofer, P.; Schröder, B.; Mueller, E.N. Soil changes under different land-uses in the Cerrado of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Geoderma Regional 2015, 4, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Gao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Luo, J.; Fan, X. Vegetation influence on the soil hydrological regime in permafrost regions of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Geoderma 2019, 354, e113892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; Delonge, M.S. Comparing infiltration rates in soils managed with conventional and alternative farming methods: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Llanillo, R.; Telles, T.S.; Junior, D.S.; De Melo, T.R.; Friedrich, T.; Kassam, A. Expansion of no-tillage practice in conservation agriculture in Brazil. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 208, e104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.F.; Macedo, P.M.S.; Pinto, M.F.; Almeida, W.S.; Schultz, N. Soil loss and runoff obtained with customized precipitation patterns simulated by InfiAsper. Soil loss and runoff obtained with customized precipitation patterns simulated by InfiAsper. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2022, 10, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, J.S.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Montagner, D.B.; De Araujo, A.R.; Zamboni, P.A.P.; Sobrinho, T.A. Cienceationtrogen fertilization and stocking rates on soil erosion and water infiltration in a Brazilian Cerrado farm. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 304, e107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.M.; Guerreiro, M.J.S.; Palácio, H.A.Q.; Campos, D.A. Ecohydrology in a Brazilian tropical dry forest: thinned vegetation impact on hydrological functions and ecosystem services. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studeis 2020, 27, e100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, M.M.; Poozan, M.T.; Afrasiab, P. Modelling soil water infiltration variability using scaling. Biosystems Engineering 2020, 196, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiras, N.; Roth, C.H. Infiltration measurements with double-ring infiltrometers and a rainfall simulator under different surface conditions on an Oxisol. Soil and tillage research 1987, 9, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.C.S.; Almeida, W.S.; Souza, A.P.; Schultz, N.; Anache, J.A.A.; Carvalho, D.F. Simulated rainfall in Brazil: an alternative for the assessment of soil surface processes and opportunity for technological development. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2024, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Sobrinho, T.; Gómez-Macpherson, H.; Gómez, J.A. A portable integrated rainfall and overland flow simulator. Soil Use and Management 2008, 24, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panachuki, E.; Bertol, I.; Alves Sobrinho, T.; Oliveira, P.T.S.D.; Rodrigues, D.B.B. Perdas de solo e de água e infiltração de água em Latossolo Vermelho sob sistemas de manejo. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do solo 2011, 35, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, K.D.S.; Panachuki, E.; Monteiro, F.D.N.; Silva, R.; Rodrigues, D.B.; Sone, J.S.; Oliveira, P.T.S. Surface runoff and soil erosion in a natural regeneration area of the Brazilian Cerrado. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2020, 8, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.A.B.; Souza, A.P.; Almeida, F.T.; Hoshide, A.K.; Araújo, H.B.; Silva, A.F.; Carvalho, D.F. Effects of Land Use and Cropping on Soil Erosion in Agricultural Frontier Areas in the Cerrado-Amazon Ecotone, Brazil, Using a Rainfall Simulator Experiment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wichern, D.W. Applied multivariate statistical analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; 815p. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, G.A.; Metl, A.R. Soil property analysis using principal components analysis, soil line, and regression models. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2005, 69, 1782–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, e20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajik, S.; Ayoubi, S.; Khajehali, J.; Shataee, S. Effects of tree species composition on soil properties and invertebrates in a deciduous forest. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, M.K.; Abd-Elmabod, S.K.; Aldosari, A.A.; Elrys, A.S.; Mohamed, E.S. Multivariate analysis for assessing irrigation water quality: A case study of the Bahr Mouise Canal, Eastern Nile Delta. Water 2020, 12, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, M.K.; Mohamed, E.S.; Wagdi, E.M.; Shahin, S.A.; Aldosari, A.A.; Lasaponara, R.; Alnaimy, M.A. Quantitative evaluation of soil quality using Principal Component Analysis: The case study of El-Fayoum depression Egypt. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz, J.P.; De Santiago-Martín, A.; Valverde-Asenjo, I.; Quintana-Nieto, J.R.; González-Huecas, C.; López-Lafuente, A.L. Comparison of soil quality indexes calculated by network and principal component analysis for carbonated soils under different uses. Ecological Indicators 2022, 143, e109374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, F.A.; Alves, M.A.B.; Borella, D.R.; Kraeski, A.; Almeida, F.T.D.; Zolin, C.A.; Hoshide, A.K.; Souza, A.P. Effects of Land Use on Soil Physical-Hydric Attributes in Two Watersheds in the Southern Amazon, Brazil. Soil Systems 2023, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.A.B.; Borella, D.R.; Silva Luz, C.C.; Castagna, D.; Da Silva, W.C.; Silva, A.F.; Souza, A.P. Classes de solos nas bacias hidrográficas dos rios Caiabi e Renato, afluentes do rio Teles Pires, no sul da Amazônia. Nativa 2022, 10, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabino, M.; Souza, A.P.; Uliana, E.M.; Lisboa, L.; Almeida, F.T.; Zolin, C.A. Intensity-duration-frequency of maximum rainfall in Mato Grosso State. Revista Ambiente Água 2020, 15, e2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.C.; Donagemma, G.K.; Fontana, A.; Teixeira, W.G. Manual de métodos de análise de solo. 2017. 3 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Embrapa Solos, 573p. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/handle/doc/1085209.

- Kostiakov, A.N. On the dynamics of the coefficient of water percolation in soils and on the necessity of studying it from a dynamic point of view for purposes of amelioration. Transactions of the Sixth Commission of the International Society of Soil Science. 1932. Part A (Moscow) p.17–21.

- Lewis, M.R. The rate of infiltration of water in irrigation practice. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1937, 18, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Analysis of runoff plat experiments with varying infiltration capacity. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1939, 20, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. The role of infiltration in the hydrological cycle. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1933, 14, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.R. Theory of infiltration. Adv. Hydrosci. 1969, 5, 215–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.R. The theory of infiltration Sorptivity and algebraic infiltration equations. Soil Science 1957, 84, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models: part 1. A discussion of principles. Journal of Hydrology 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE_Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Estado do Mato Grosso: Pedologia (Mapa Exploratório de Solos); 2009. Available online: https://geoftp.ibge.gov.br/informacoes_ambientais/pedologia/mapas/unidades_da_federacao/mt_pedologia.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- EPE_Empresa de Pesquisa Energética. Avaliação Ambiental Integrada da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Teles Pires; 2009; 67p. Available online: https://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-248/topico-292/AAI%20Teles%20Pires%20-%20Relat%C3%B3rio%20Final%20-%20Sum%C3%A1rio%20Executivo[1].pdf#search=teles%20pires> (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Centeri, C. Effects of grazing on water erosion, compaction and infiltration on Grasslands. Hydrology 2022, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronti, S.; Ungaro, F.; Maienza, A.; Ugolini, F.; Lagomarsino, A.; Agnelli, A.E.; Calzolari, C.; Pisseri, F.; Robbiati, G.; Vaccari, F.P. Rotational pasture management to increase the sustainability of mountain livestock farms in the Alpine region. Regional Environmental Change 2022, 22, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.G.; Cogo, N.P.; Volk, L.B.D.S. Alterations in soil surface roughness by tillage and rainfall in relation to water erosion. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2006, 30, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.D.N.D.; Panachuki, E.; Alves Sobrinho, T.; Oliveira, P.T.S.D.; Rodrigues, D.B.B. Water infiltration in na ultisol after cultivation of common bean. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2014, 38, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.B.; Marasca, I.; Martins, M.B.; Sandi, J.; Da Silva, K.G.P.; Lanças, K.P. Effect of traffic in agricultural soil water infiltration and the physical atributes of the soil. Irriga 2022, 27, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döbert, T.F.; Bork, E.W.; Apfelbaum, S.; Carlyle, C.N.; Chang, S.X.; KhaI-Chhetri, U.; Silva Sobrinho, L.; Thompson, R.; Boyce, M.S. Adaptive multi-paddock grazing improves water infiltration in Canadian grassland soils. Geoderma 2021, 401, e115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.F.; Eduardo, E.N.; Almeida, W.S.; Santos, L.A.; Alves Sobrinho, T. Water erosion and soil water infiltration in different stages of corn development and tillage systems. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental 2015, 19, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sub-basin Region | Sand | Clay | Silt | Micro | Macro | TPo | Pd | Bd | K0 | Pdm |

| .............%........... | .........m3 m-3........... | ..... g cm-3...... | cm h-1 | Mg ha-1 | ||||||

| Caiabi River – Cultivated (soybean) | ||||||||||

| Upper | 42.49B | 27.9A | 29.61A | 0.28A | 0.08A | 0.36A | 2.14B | 1.02B | 1.21A | 11.91A |

| Middle | 76.56A | 17.8B | 5.64B | 0.27A | 0.11A | 0.38A | 2.54A | 1.50A | 1.12A | 10.20A |

| Lower | 78.5A | 15.6B | 5.9B | 0.35A | 0.08A | 0.43A | 2.52A | 1.50A | 1.28A | 10.99A |

| Caiabi River – Pasture | ||||||||||

| Upper | 49.24B | 36.1A | 14.66A | 0.27A | 0.10A | 0.38A | 2.44A | 1.41A | 0.33A | 8.24A |

| Middle | 49.21B | 34.6A | 16.19A | 0.35A | 0.02A | 0.37A | 2.33B | 1.58A | 0.67A | 8.90A |

| Lower | 84.37A | 11.0B | 4.63B | 0.29A | 0.11A | 0.39A | 2.61A | 1.58A | 1.70A | 7.26A |

| Renato River – Cultivated (corn) | ||||||||||

| Upper | 75.18B | 16.2A | 8.62A | 0.43A | 0.09A | 0.52A | 2.71A | 1.57A | 0.79A | 5.21B |

| Middle | 82.87A | 12.9B | 4.23A | 0.29B | 0.08A | 0.37B | 2.73A | 1.53A | 1.22A | 6.48B |

| Lower | 73.90B | 19.4A | 6.7A | 0.28B | 0.09A | 0.37B | 2.65A | 1.56A | 0.68A | 12.07A |

| Renato River – Pasture | ||||||||||

| Upper | 80.43A | 15.9A | 3.67A | 0.40A | 0.02A | 0.42A | 2.78A | 1.53B | 1.22A | 8.07A |

| Middle | 83.16A | 12.9A | 3.94A | 0.37A | 0.06A | 0.43A | 2.63A | 1.59B | 0.57A | 8.29A |

| Lower | 81.94A | 14.7A | 3.36A | 0.33A | 0.04A | 0.37A | 2.69A | 1.75A | 0.90A | 6.65A |

| Sub-basin | Trat | Upper | Middle | Lower | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rio | Rif | Rio | Rif | Rio | Rif | ||

| Caiabi | Cultivated | ||||||

| CS | 66.46Aa | 31.57Ab | 65.31Aa | 45.64Aa | 65.31Aa | 35.16Bb | |

| WCS | 61.82Aa | 15.04Bb | 63.51Aa | 35.67Aa | 44.77Bb | 32.41Ba | |

| SD | 68.54Aa | 34.39Ab | 61.34Aa | 30.98Bb | 71.06Aa | 60.22Aa | |

| Pasture | |||||||

| CS | 34.57Ba | 2.67Cb | 40.62Ba | 15.64Ba | 42.90Ba | 12.23Aba | |

| WCS | 44.14Ba | 3.96Cc | 55.57Aa | 21.29Ba | 40.59Ba | 5.94Bc | |

| SD | 69.86Aa | 56.71Aa | 61.34Aa | 30.98Ab | 61.20Aa | 18.70Ac | |

| Renato | Cultivated | ||||||

| CS | 61.63Aa | 17.92Aa | 39.00Bb | 11.77Ab | 58.38Ab | 18.35Aa | |

| WCS | 61.93Aa | 19.40Aa | 17.40Cc | 11.83Ab | 22.37Bc | 8.00Bb | |

| SD | 63.21Aa | 11.2ABa | 67.11Aa | 5.43Ab | 63.43Aa | 13.43Ba | |

| Pasture | |||||||

| CS | 68.14Aa | 38.64Ba | 26.79Cb | 4.19Cc | 54.01Aa | 12.46Bc | |

| WCS | 63.30Aa | 23.30Ba | 42.43Bb | 1.00Cc | 61.61Ac | 9.76Bb | |

| SD | 69.86Aa | 62.51Aa | 62.57Aa | 37.29Ab | 68.43Aa | 36.26Ab | |

| Land cover | Soil management | Model | R2 | RMSE | NSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated (soybean) | Upper | |||||

| CS | Ti = 31.57 +(66.46 – 31.57) e-0.14 t | Horton | 0.84 | 3.79 | 0.85 | |

| WCS | Ti = 4.55+ 116.70 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.86 | 3.27 | 0.86 | |

| SD | Ti = 34.39 +(68.54 – 34.39) e -7.52 t | Horton | 0.51 | 15.68 | -0.66 | |

| Middle | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 42.39+ 46.77t -0.5 | Philip | 0.78 | 1.37 | 0.79 | |

| WCS | Ti = 29.24+ 69.06 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.90 | 1.27 | 0.90 | |

| SD | Ti = 24.16+ 80.08 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.78 | 2.90 | 0.78 | |

| Lower | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 26.98+ 70.23 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.83 | 1.78 | 0.83 | |

| WCS | Ti = 28.58+ 18 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.66 | 1.91 | 0.66 | |

| SD | ------- | ------ | ||||

| Pasture | Upper | |||||

| CS | Ti = 2.67 +(34.57 – 2.67) e-0.15 t | Horton | 0.90 | 2.83 | 0.90 | |

| WCS | Ti = 3.96 + (2.70). 145.19 t -2.70 1 | KL | 0.85 | 3.79 | 0.84 | |

| SD | Ti = 56.71 +(69.86 – 56.71) e -0.13 t | Horton | 0.77 | 2.12 | 0.77 | |

| Middle | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 10.73+ 57.47 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.76 | 3.01 | 0.76 | |

| WCS | Ti = 13.80+ 84.91 t -0.5 | Philip | 082 | 3.71 | 0.82 | |

| SD | Ti = 30.98 +(61.34 -30.98) e -0.15 t | Horton | 0.79 | 3.86 | 0.79 | |

| Lower | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 0.82 + 121.34 t-0.5 | Philip | 0.87 | 3.56 | 0.87 | |

| WCS | Ti = 5.45 + 125.68 t-0.5 | Philip | 0.91 | 2.93 | 0.92 | |

| SD | Ti = 18.70 +(61.20 – 18.70) e-0.18 t | Horton | 0.91 | 2.47 | 0.91 | |

| Land cover | Soil management | Model | R2 | RMSE | NSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated (corn) | Upper | |||||

| CS | Ti = 17.92 +(61.63 – 17.92) e -0.11 t | Horton | 0.72 | 6.77 | 0.72 | |

| WCS | Ti = 19.40 +(61.93 – 19.40) e -0.85 t | Horton | 0.85 | 6.60 | 0.55 | |

| SD | Ti = 11.20+(63.21 – 11.20) e -0.90 t | Horton | 0.90 | 13.68 | 0.20 | |

| Middle | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 6.95+ 62.40 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.83 | 2.57 | 0.84 | |

| WCS | Ti = 9.96+ 12.74 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.23 | 2.12 | 0.24 | |

| SD | Ti = 11.35+ 116.40 t -0.5 | Philip | 0.87 | 5.07 | 0.90 | |

| Lower | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 11.26+ 101.87 t 0.5 | Philip | 0.94 | 2.38 | 0.94 | |

| WCS | Ti = 3.66+ 71.69 t 0.5 | Philip | 0.83 | 2.63 | 0.87 | |

| SD | Ti = Tif +(63.43 – 13.43) e-0.10 t | Horton | 0.92 | 4.13 | 0.92 | |

| Pasture | Upper | |||||

| CS | Ti = 38.64 +(68.14 – 38.64) e -0.27 t | Horton | 0.81 | 3.03 | 0.81 | |

| WCS | Ti = Tif + (0.05) 756.35 t -0.051 | KL | 0.91 | 2.42 | 0.92 | |

| SD | Ti = 62.51 +(69.86 – 62.51) e-0.04 t | Horton | 0.45 | 1.86 | 0.47 | |

| Middle | ||||||

| CS | Ti = 4.19 +(26.79 – 4.19) e-0.13 t | Horton | 0.82 | 2.50 | 0.82 | |

| WCS | Ti = 1.00 + (42.43 – 1.00) e-0.13 t | Horton | 0.82 | 4.48 | 0.85 | |

| SD | Ti = 37.29 + (0.38)79.05 t -0.381 | KL | 0.60 | 5.94 | 0.97 | |

| Lower | ||||||

| CS | Ti = Tif + (0.08) 509.14 t-0.081 | KL | 0.89 | 2.88 | 0.95 | |

| WCS | Ti = 9.76 +(61.61 -9.76) e-0.24 t | Horton | 0.88 | 4.67 | 0.86 | |

| SD | Ti = 36.26 +(68.43 -36.26) e-0.10 t | Horton | 0.84 | 4.69 | 0.84 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).