1. Introduction

Lymphoma is one of the most common types of cancer in cats, and chemotherapy is often the treatment of choice for this disease [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The expected survival rate in animals treated with multi-drug chemotherapy protocols is 6-9 months, and the remission rate is approximately 65-75% [

7]. The response to therapy can be considered a prognostic indicator, as animals that do not achieve complete remission have a shorter survival time [

1,

8,

9].

Another factor that influences a negative prognosis regarding the response to chemotherapy is feline leukemia virus (FeLV)-positive status [

1,

10], an important factor to consider in regions where there is still a high correlation between lymphomas and FeLV infection [

5]. In these animals, the survival time is usually much shorter (3-4 months) [

7].

The side effects of chemotherapy are also a significant concern. Leukopenia is a treatment-limiting factor, and cats may also experience anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, azotemia, and elevated Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) [

2,

5,

8,

11], this can result in delays in chemotherapy sessions and, consequently, an increased risk of relapses [

8,

12]. The effects presented are mainly related to the fact that the drugs used are non-specific, affecting healthy cells as well. Additionally, cats have specific metabolic pathways that can result in higher drug accumulation in the body, an extended half-life, and an increased risk of toxicity compared to dogs [

13]. As a result, there is a need to stimulate the development of new drugs that can extend survival time and ensure a good quality of life for patients with lymphoma.

The use of oncolytic viruses is a therapeutic approach that has gained prominence in recent years, as they can directly induce oncolysis and have effects on the immune system, thereby modulating the tumor microenvironment [

14,

15]. These viruses can selectively replicate, destroying tumor cells without causing harm to healthy cells[

16]. Most strains chosen for use in this type of treatment are attenuated strains or strains that can infect and replicate in the chosen species without causing significant harm [

17].

The genetically modified herpes simplex virus, Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), has been recognized by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicine Agency [

17]. This was a significant step in expanding research efforts aimed at the development of oncolytic virus-based therapies in human medicine and veterinary medicine, the latter of which has a smaller number of studies conducted in the field.

The Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) is another viral vector whose oncolytic activity has been observed in various types of cancer, including lymphoma in human cells [

18,

19] and canine cells [

18]. NDV is an enveloped, non-segmented virus with negative-sense RNA, belonging to the genus

Avulavirus and the family Paramyxoviridae (APMV-1) [

20,

21], exhibiting variable virulence and circulates in both domestic and wild bird species, with the more virulent strains causing Newcastle Disease [

22]. NDV has the ability to induce apoptosis through both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, as well as trigger innate and adaptive immunity [

23,

24]. Its selectivity for neoplastic cells is related to a low antiviral response mediated by type I interferon (IFN)[

24,

25] and the high expression of viral proteins by tumor cells, so that the abundant expression of sialoglycoproteins on the surface of cancer cells promotes preferential association with neoplastic cells at the expense of healthy cells [

26,

27].

Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the antitumor activity of a recombinant lentogenic NDV LaSota strain expressing the GFP protein (NDV-GFP) in a feline lymphoma cell line and a non-tumorigenic feline cell line.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell line

The cell line (FeLV3281) was previously isolated, characterized [

28] and acquired from the Cell Bank Riken (Japan). These cells originated from a cat (

Felis catus) with thymic T-cell lymphoma and were positive for the Feline Leukemia Virus subtype A. The cells were maintained in 75 cm

2 flasks at 37°C and 5% CO

2 in Gibco Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic. The cells were observed daily using optical microscopy (Axio Vert A1, Zeiss, Jena, Germany). All reagents used for cell culture were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (California, USA) unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Virus titration and morphological analysis

The virus used in this study was a genetically modified LaSota strain expressing GFP [

29] (NDV-GFP) and was kindly provided by Dr. Muhammad Munir (Lancaster University, UK). The virus titer was obtained by calculating the median tissue culture infectious dose per milliliter (TCID

50/mL) using the Reed and Muench method [

30]. Briefly, FeLV3281 cells (CEUAx Nº 7900110523) were seeded at 4.5x10

4 cells/well in 96-well plates containing RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic. The cells were exposed to different concentrations of the virus (10

-1-10

-11) and the cytopathic effects were monitored for five days. Images of the cells were captured in both bright-field and fluorescence field using ZEISS—Axio Vert A1 with an Axio Can 503 camera attached using a 520 nm wavelength filter for green color (ZEISS, Jena, Thuringia, Germany).

2.3. Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)

The blood samples used in this experiment were kindly provided by the Pet Nutrology Research Center (CEPEN Pet, FMVZ USP) for the isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) following the adapted protocol of Passarelli et al. [

31]. Briefly, 1 mL of total blood from each cat was collected in EDTA tubes, diluted 1:1 with 1x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), and then carefully layered on top of Histopaque®-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, Sao Paulo, Brazil). Isolation was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The cells were then suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic. Cells from one sample were promptly used for the NDV cytotoxicity analysis.

2.4. Virus infection and replication in cell lines

During viral titration, cells were periodically evaluated under a bright-field inverted microscope every 24 h for five days to assess any morphological effects possibly caused by the virus. Cells were also assessed under fluorescence using the same microscope to visualize the presence of the virus in the cells through GFP expression. For the cytotoxicity assessment assays, neoplastic cells and PBMCs were analyzed under a bright-field and fluorescent inverted microscope every 24 h for 1 day. In the bright field, differences between wells treated with different virus dilutions and the control wells (without the virus) were compared.

2.5. NDV cytotoxic assay

FeLV3281 cells were added to 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic, 2% GlutaMAX, and 1% HEPES. Then, cells were exposed to NDV-GFP that had undergone serial dilutions in pure RPMI 1640 with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 x 100, 2 x 10-1, 4 x 10-2, 8 x 10-3, 1.6 x 10-3, 3.2 x 10-4, 6.4 x 10-5, and 1.28 x 10-5 based on TCID50/mL. The assay was conducted in triplicates. The plates were incubated for up to 24h. The cells were observed under bright-field and fluorescence conditions, and images of each dilution were captured. To analyze the cytotoxicity of NDV-GFP, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the virus was determined using the CellTiter-Blue® reagent (Promega, USA) cell viability assay. At the end of the viral treatment, 20μL of CellTiter-Blue® was added to all wells, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The plates were analyzed using a spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 540 nm and 630 nm (LMR 96, Loccus, Brazil), and cell viability was measured in terms of absorbance. IC50 was determined using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0; San Diego, CA, USA).

2.6. Cell death assay

FeLV3281 cells were added to T25 cm

2 flasks at a concentration of 1x10

6 cells per flask in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic, 2% glutaMAX, and 1% HEPES. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to IC

50 values calculated in the cytotoxicity assay. The assay was conducted in triplicate, with three flasks treated with IC

50 (treatment) and three flasks left untreated (control). The flasks were maintained in a CO

2 incubator at 37°C for 24 h. The cells were observed under bright-field and fluorescent conditions, and images in each field were captured. To analyze whether the observed cytopathic effects were triggered by an increase in the number of apoptotic cells, a flow cytometry assay using propidium iodide (PI) was conducted following a protocol adapted from Riccardi et al. [

32]. For this, the cells were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded and resuspended in 500 µL of PBS. Cells were fixed in 4.5 mL of chilled 70% ethanol and stored at -20°C for at least 24 h. The cells were centrifuged at 400G for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were washed in 5 mL PBS and centrifuged at 400G for 5 min. The cells were then resuspended in 1 mL of PI staining solution (200 µg in 10 mL PBS and 2 mg DNAse-free RNAse) and incubated for half an hour at room temperature. 20.000 events were captured using a flow cytometer (S3

TM Cell Sorter, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) with a 488-nm laser line for excitation, measuring red fluorescence (4600 nm), and side scatter.

3. Results

3.1. Virus titration

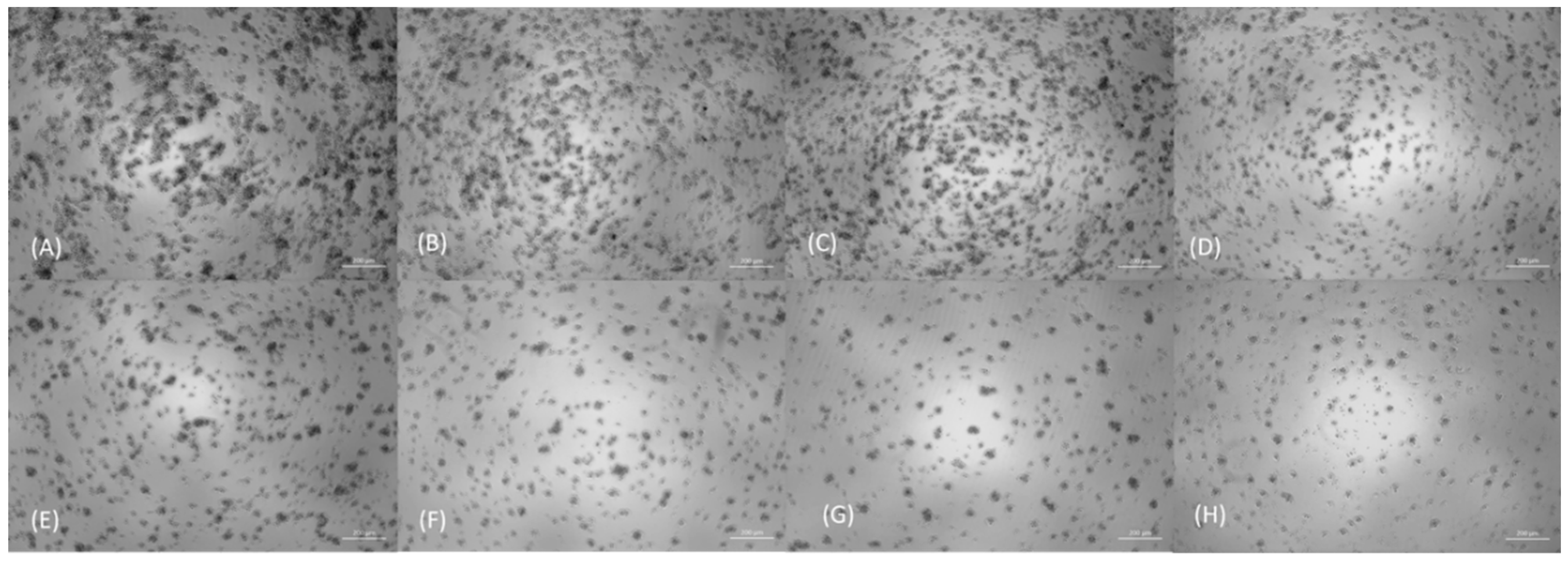

The titer obtained for NDV-GFP in FeLV3281 was 3.433x10

6 TCID

50/mL. The main cytopathic effects evaluated under bright-field inverted microscopy included cell rupture with debris release and cell retraction. We also observed a reduction in the number of cells per well in cells treated with higher concentrations of the virus (

Figure 1). Syncytium formation was not observed in this cell line. After 120 h of exposure, cytopathic effects were not observed in 50% of the wells from the seventh dilution onwards, whereas cytopathic effects were observed in all wells up to the third dilution.

3.2. NDV-GFP is cytotoxic and induces apoptosis in lymphoma cells

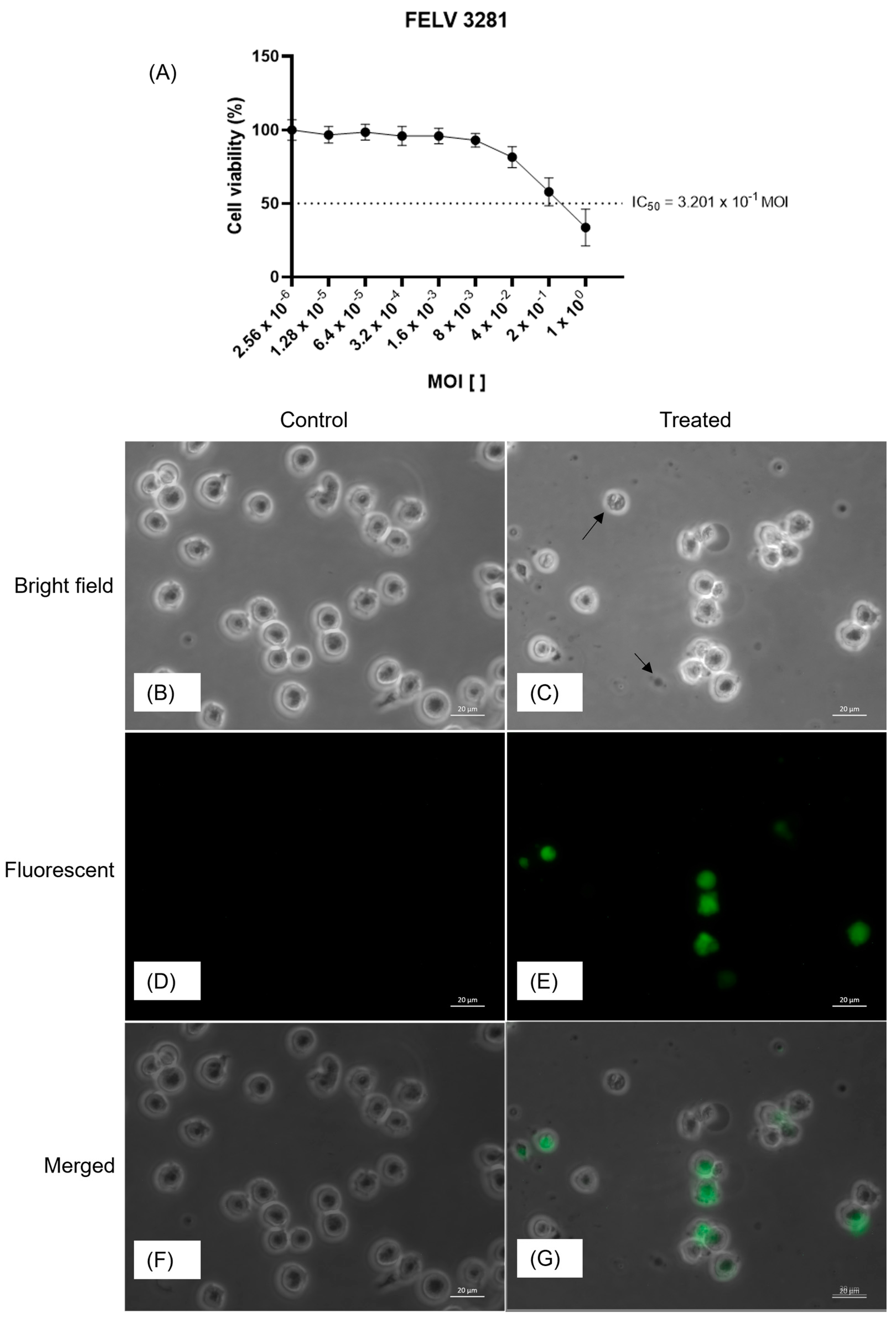

The oncolytic potential of NDV-GFP was assessed by determining its IC

50 value in FeLV3281 cells. A decrease in cell viability was observed at MOI= 4 x 10

-2 to MOI= 1 x 10

0 (

Figure 2). GFP expression was observed at all virus concentrations, except in the control, with higher expression and number of infected cells at higher virus concentrations. The calculated IC

50 value (MOI) was 3.201 x 10

-1 ± 0.04. In cells treated with the concentration corresponding to the IC

50, a reduction in cell confluence was observed, along with a higher presence of cellular

debris (

Figure 2). Additionally, GFP expression was observed at this same concentration (

Figure 2), indicating that the observed effects were triggered by viral infection.

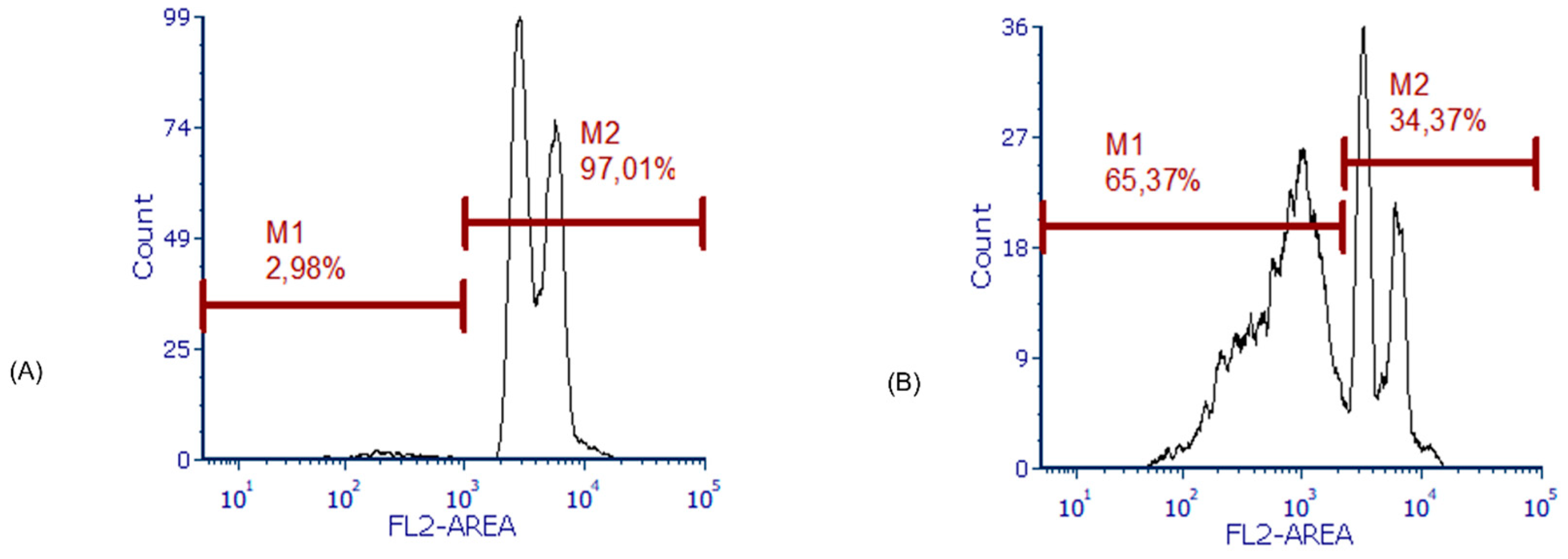

We also observed a significantly higher occurrence of apoptosis in cells treated with the IC

50 (61.95% ± 2.20%) compared to untreated cells (1.97% ± 0.54%, p < 0.01;

Figure 3).

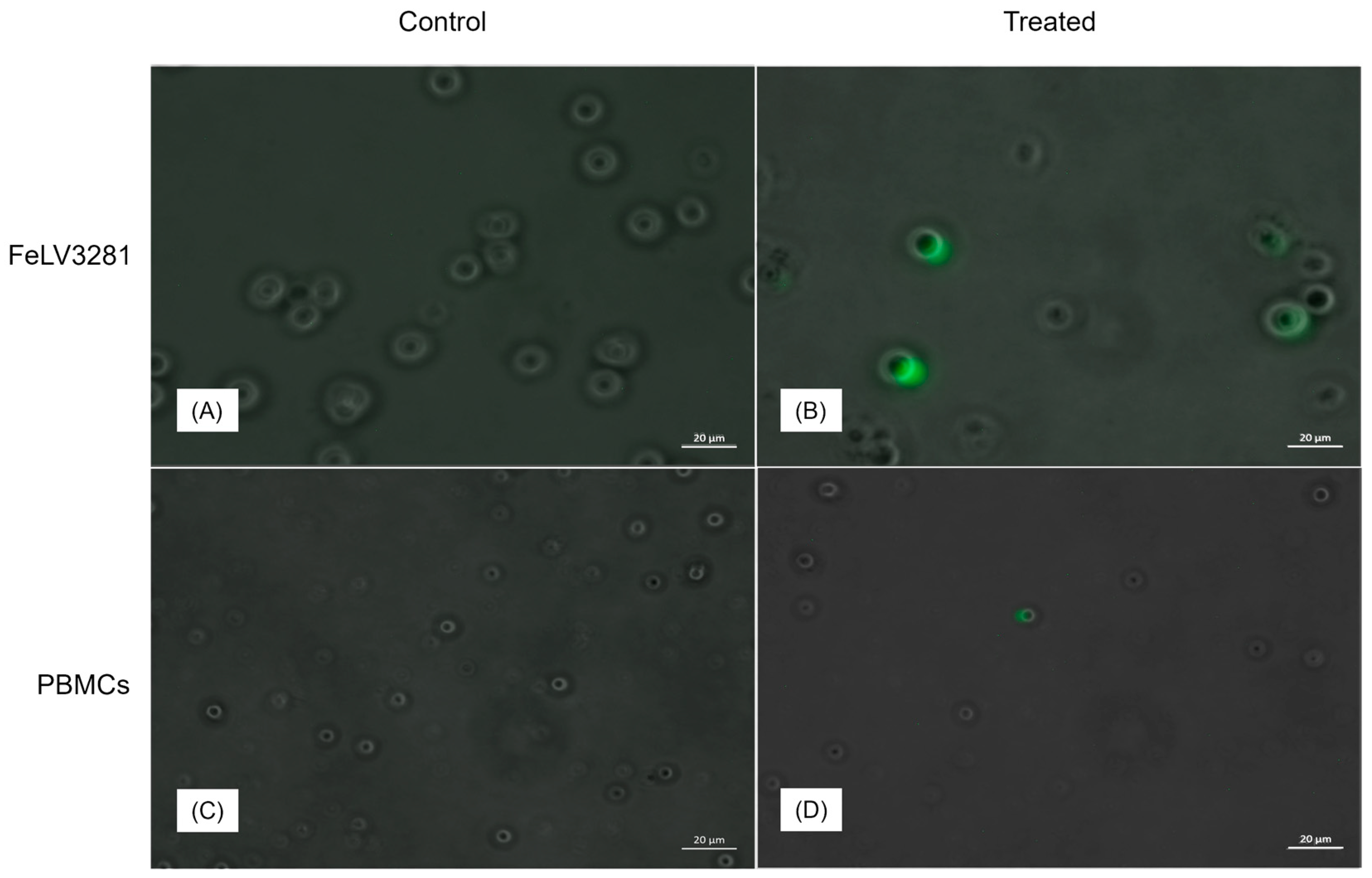

3.3. Lymphoma cells are prone to infection and replication by NDV-GFP

Based on the expression of GFP in cells after exposure to NDV-GFP, we observed that NDV had a greater capacity to infect and replicate in lymphoma cells than in control PBMC (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we provided evidence of the oncolytic properties of NDV-GFP in feline lymphoma cells, demonstrating that NDV exhibits a selective capability for invasion, replication, and elimination of cancer cells. Our findings demonstrate that NDV-GFP exhibits a discerning preference for cancer cells over peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), as NDV-GFP specifically induces apoptosis in cancer cells. This is supported by the limited viral infection and replication observed in non-cancer cells. Therefore, this study corroborates our (and others) previous findings on the high specificity of NDV for cancer cells in contrast to non-cancer cells in humans [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] and dogs [

18,

25,

39,

40].

Cats are particularly vulnerable to the development of blood-related tumors such as lymphoma, and there is an urgent need for new therapies. Given that animals may not respond or become resistant to standard therapy, some factors are also associated with a poorer response to treatment, and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infection is an important factor to be considered [

41]. FeLV can further worsen the quality of life for the patient, as the animal may present various clinical signs resulting from the infection, such as non-regenerative anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia [

42]. Therefore, in addition to the deterioration of the patient's overall condition, they also become more susceptible to secondary infections due to immunodeficiency resulting from chemotherapy and FeLV. Thus, FeLV poses an even greater obstacle for animals undergoing chemotherapy. Therefore, the search for new therapeutic approaches for these animals with a worse prognosis becomes urgent.

Interestingly, lymphomas in both humans and canines are susceptible to the lentogenic strain NDV-MLS compared to control cells (PBMCs), as shown by Sanchez et al. [

18]. These findings are similar to those observed in our study, where NDV-GFP decreased the survival of feline lymphoma cells in a dose-dependent manner. The use of NDV as an oncolytic agent can be considered safe, given that it is a type of virus that naturally affects domestic and wild birds. In a study conducted with non-human primates, intravenous administration of a high dose of NDV was considered safe, as it did not lead to the manifestation of severe disease or alterations in hematological and biochemical tests [

43]. More severe infections in mammals typically result in mild clinical signs, such as conjunctivitis when exposed to more virulent strains or higher doses of the virus [

44]. Additionally, NDV demonstrates selective viral replication, preferring to infect neoplastic cells.

To directly investigate the selective viral replication of NDV in cancer cells, some studies have employed a genetically modified virus for GFP expression, allowing the observation of green fluorescence only in infected cells at different time points post-infection through fluorescence microscopy. In a study conducted by Fiola et al., weak, or nonexistent fluorescence signals were observed in non-tumor cells, while tumor cell lineages exhibited an exacerbated and prolonged expression, similar to what was observed in our work. In the same study, it was found that the replication cycle of NDV stopped after the production of positive-sense RNA in non-tumor cells. Conversely, in tumor cells, replication commenced from 10 hours post-infection and continued up to 50 hours, with viral genome copying occurring within this timeframe [

45].

NDV replicates less efficiently in healthy cells, mostly because of the active interferon-response pathways [

25,

46]. The NDV-GFP used in this work is especially useful because it allows for the evaluation of virus infection and replication in cells by the detection of GFP. Therefore, when we compared GFP detection in feline lymphoma cells and healthy cells (PBMCs) exposed to NDV-GFP, it was possible to conclude that cancer cells are more susceptible to NDV-GFP replication and cell death by apoptosis. NDV induces cancer cell death through different mechanisms, including the induction of apoptosis in response to viral infection [

23,

47]. Although we could not perform a quantitative cytotoxicity assay with PBMCs, we detected less viral replication in PBMC via GFP expression. In addition, extensive literature demonstrates the selectivity of NDV for cancer cells in contrast to non-cancer cells in humans and other species.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate NDV as a potential oncolytic therapy for cancer in cats. The oncolytic effect of NDV-GFP in feline lymphoma cells is supported by the demonstration of viral infection and replication by GFP detection and confirmation of lymphoma cytotoxicity by the induction of apoptosis. Additionally, it was demonstrated that the virus preferentially replicates in lymphoma cells compared to healthy cells. In conclusion, these results support the development of new oncolytic therapies based on NDV candidates in this species, which is an urgent need owing to the disadvantages of the present adopted treatment modalities such as chemotherapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.F., T.G.L.A. and P.L.P.X.; Methodology: H.F., T.G.L.A., P.L.P.X; Formal analysis: H.F. and T.G.L.A.; Investigation: T.G.L.A., P.L.P.X., A.L.R.; Resources: H.F., M.M., T.H.A.V. and M.A.B.; Writing–original draft: H.F. and T.G.L.A.; Writing – Review & Editing: all authors; Supervision: H.F.; Project Administration: H.F.; Funding Acquisition: H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, grant number: 143954/2021-0; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP, Thematic grant: 2022/09378-5; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP, grant number: 2023/09122-3; and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP, Generation grant: 2022/06305-7.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Faculdade de Zootecnia e Engenharia de Alimentos from Universidade de São Paulo (protocol code CEUAx Nº 1537130919, approved 12/15/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Helena L. Ferreira for the initial contact between Fukumasu and Munir.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Teske, E.; Van Straten, G.; Van Noort, R.; Rutteman, G.R. Chemotherapy with Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, and Prednisolone (COP) in Cats with Malignant Lymphoma: New Results with an Old Protocol. J Vet Intern Med 2002, 16, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Horta, R.S.; Souza, L.M.; Sena, B. V.; Almeida, I.O.; Jaretta, T.A.; Pimenta, M.M.; Reche Júnior, A. LOPH: A Novel Chemotherapeutic Protocol for Feline High-Grade Multicentric or Mediastinal Lymphoma, Developed in an Area Endemic for Feline Leukemia Virus. J Feline Med Surg 2021, 23, 86–97. [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.; Harper, A.; Blackwood, L. Lomustine, Methotrexate and Cytarabine Chemotherapy as a Rescue Treatment for Feline Lymphoma. J Feline Med Surg 2021, 23, 722–729. [CrossRef]

- Martin, O.A.; Price, J. Mechlorethamine, Vincristine, Melphalan and Prednisolone Rescue Chemotherapy Protocol for Resistant Feline Lymphoma. J Feline Med Surg 2018, 20, 934–939. [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Eberle, N.; Laacke-Singer, L.; Nolte, I. Combination Chemotherapy in Feline Lymphoma: Treatment Outcome, Tolerability, and Duration in 23 Cats. J Vet Intern Med 2008, 22, 394–400. [CrossRef]

- Vail, D.M.; Thamm, D.H.; Liptak, J.M. Withrow & MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology; 6th ed.; Elsevier: Missouri, Estados Unidos, 2020; Vol. 1; ISBN 978-0-323-59496-7.

- Couto, G. Advances in the Treatment of the Cat with Lymphoma in Practice. In Proceedings of the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery; Ohio, 2000; Vol. 2, pp. 95–100.

- Waite, A.H.K.; Jackson, K.; Gregor, T.P.; Krick, E.L. Lymphoma in Cats Treated with a Weekly Cyclophosphamide-, Vincristine-, and Prednisone-Based Protocol: 114 Cases (1998–2008). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2013, 242, 1104–1108. [CrossRef]

- Collette, S.A.; Allstadt, S.D.; Chon, E.M.; Vernau, W.; Smith, A.N.; Garrett, L.D.; Choy, K.; Rebhun, R.B.; Rodriguez, C.O.; Skorupski, K.A. Treatment of Feline Intermediate- to High-Grade Lymphoma with a Modified University of Wisconsin-Madison Protocol: 119 Cases (2004-2012). Vet Comp Oncol 2016, 14, 136–146. [CrossRef]

- Kristal, O.; Lana, S.E.; Ogilvie, G.K.; Rand, W.M.; Cotter, S.M.; Moore, A.S. Single Agent Chemotherapy with Doxorubicin for Feline Lymphoma: A Retrospective Study of 19 Cases (1994-1997). J Vet Intern Med 2001, 15, 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Sunpongsri, S.; Kovitvadhi, A.; Rattanasrisomporn, J.; Trisaksri, V.; Jensirisak, N.; Jaroensong, T. Effectiveness and Adverse Events of Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, and Prednisolone Chemotherapy in Feline Mediastinal Lymphoma Naturally Infected with Feline Leukemia Virus. Animals 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.; Harper, A.; Blackwood, L. Lomustine, Methotrexate and Cytarabine Chemotherapy as a Rescue Treatment for Feline Lymphoma. J Feline Med Surg 2020, 23, 722–729. [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.S. Cats and Chemotherapy: Treat as “small Dogs” at Your Peril. J Feline Med Surg 2013, 15, 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Liang, T. Oncolytic Virotherapy: Basic Principles, Recent Advances and Future Directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, P.F.; Pala, L.; Conforti, F.; Cocorocchio, E. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-vec): An Intralesional Cancer Immunotherapy for Advanced Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, S.; Chen, N.G.; Fong, Y. Oncolytic Viruses and Immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2018, 51, 83–90.

- Mondal, M.; Guo, J.; He, P.; Zhou, D. Recent Advances of Oncolytic Virus in Cancer Therapy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 2389–2402.

- Sánchez, D.; Pelayo, R.; Medina, L.A.; Vadillo, E.; Sánchez, R.; Núñez, L.; Cesarman-Maus, G.; Sarmiento-Silva, R.E. Newcastle Disease Virus: Potential Therapeutic Application for Human and Canine Lymphoma. Viruses 2015, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Eli, N.; Giloh, H.; Schlesinger, M.; Zakay-Rones, Z.; Schlesinger, E.M. Preferential Cytotoxic Effect of Newcastle Disease Virus on Lymphoma Cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1996, 122, 409–415. [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, G.K.; Bào, Y.; Basler, C.F.; Bavari, S.; Beer, M.; Bejerman, N.; Blasdell, K.R.; Bochnowski, A.; Briese, T.; Bukreyev, A.; et al. Taxonomy of the Order Mononegavirales: Update 2017. Arch Virol 2017, 162, 2493–2504. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Roth, J.P.; Yu, Q. Generation of a Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus Expressing Two Foreign Genes for Use as a Multivalent Vaccine and Gene Therapy Vector. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4846–4850. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.L.; Taylor, T.L.; Dimitrov, K.M.; Sabra, M.; Afonso, C.L.; Suarez, D.L. Virulent Newcastle Disease Viruses from Chicken Origin Are More Pathogenic and Transmissible to Chickens than Viruses Normally Maintained in Wild Birds. Vet Microbiol 2019, 235, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Zamarin, D.; Palese, P. Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus for Cancer Therapy: Old Challenges and New Directions. Future Microbiol 2012, 7, 347–367. [CrossRef]

- Elankumaran, S.; Rockemann, D.; Samal, S.K. Newcastle Disease Virus Exerts Oncolysis by Both Intrinsic and Extrinsic Caspase-Dependent Pathways of Cell Death. J Virol 2006, 80, 7522–7534. [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.R.; Xavier, P.L.P.; Pires, P.R.L.; Rochetti, A.L.; Rosim, D.F.; Scagion, G.P.; de Campos Zuccari, D.A.P.; Munir, M.; Ferreira, H.L.; Fukumasu, H. Oncolytic Effect of Newcastle Disease Virus Is Attributed to Interferon Regulation in Canine Mammary Cancer Cell Lines. Vet Comp Oncol 2021, 19, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Schirrmacher, V. Molecular Mechanisms of Anti-Neoplastic and Immune Stimulatory Properties of Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, O. V.; Guo, Z.S.; Shabalina, S.A.; Chumakov, P.M. Oncolysis by Paramyxoviruses: Multiple Mechanisms Contribute to Therapeutic Efficiency. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2015, 2, 15011. [CrossRef]

- J L Rojko; G J Kociba; J L Abkowitz; K L Hamilton; W D Hardy Jr; J N Ihle; S J O’Brien Feline Lymphomas: Immunological and Cytochemical Characterization1. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 345–351.

- Al-Garib, S.O.; Gielkens, A.L.J.; Gruys, E.; Peeters, B.P.H.; Koch, G. Tissue Tropism in the Chicken Embryo of Non-Virulent and Virulent Newcastle Diseases Strains That Express Green Fluorescence Protein. Avian Pathology 2003, 32, 591–596. [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty Per Cent Endpoints. The American Journal of Hygine 1938, 27, 493–497.

- Passarelli, D. Proliferative Responses of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells against Red Blood Cells Antigens of Dogs with Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia and of Dogs Recently Vaccinated. Veterinary Clinics , University of Sao Paulo: Sao Paulo, 2011.

- Riccardi, C.; Nicoletti, I. Analysis of Apoptosis by Propidium Iodide Staining and Flow Cytometry. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 1458–1461. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Song, C.; Kong, L.; Hu, L.; Lin, G.; Ye, T.; Yao, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.; et al. Recombinant Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus Displays Antitumor Activities in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2018, 18. [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.; Burke, S.; Travers, J.; Rath, N.; Leinster, A.; Navarro, C.; Franks, R.; Leyland, R.; Mulgrew, K.; McGlinchey, K.; et al. Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus Immunotherapy Drives Oncolytic Effects and Durable Systemic Antitumor Immunity. Mol Cancer Ther 2021, 20, 1723–1734. [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, K.S.; Zhou, P.; Kovner, A. V.; Zavjalov, E.L.; Shestopalova, L. V.; Shestopalov, A.M. Oncolytic Effect of Wild-Type Newcastle Disease Virus Isolates in Cancer Cell Lines in Vitro and in Vivo on Xenograft Model. PLoS One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Buijs, P.R.A.; Van Eijck, C.H.J.; Hofland, L.J.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Van Den Hoogen, B.G. Different Responses of Human Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines to Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus Infection. Cancer Gene Ther 2014, 21, 24–30. [CrossRef]

- Alabsi, A.M.; Bakar, S.A.A.; Ali, R.; Omar, A.R.; Bejo, M.H.; Ideris, A.; Ali, A.M. Effects of Newcastle Disease Virus Strains AF2240 and V4-UPM on Cytolysis and Apoptosis of Leukemia Cell Lines. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 8645–8660. [CrossRef]

- Javaheri, A.; Bykov, Y.; Mena, I.; García-Sastre, A.; Cuadrado-Castano, S. Avian Paramyxovirus 4 Antitumor Activity Leads to Complete Remissions and Long-Term Protective Memory in Preclinical Melanoma and Colon Carcinoma Models. Cancer Research Communications 2022, 2, 602–615. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Li, M. Newcastle Disease Virus LaSota Strain Induces Apoptosis and Activates the TNFα/NF-ΚB Pathway in Canine Mammary Carcinoma Cells. Vet Comp Oncol 2023, 21, 520–532. [CrossRef]

- Numpadit, S.; Ito, C.; Nakaya, T.; Hagiwara, K. Investigation of Oncolytic Effect of Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus in Primary and Metastatic Oral Melanoma. Medical Oncology 2023, 40. [CrossRef]

- Cristo, T.G.; Biezus, G.; Noronha, L.F.; Pereira, L.H.H.S.; Withoeft, J.A.; Furlan, L. V.; Costa, L.S.; Traverso, S.D.; Casagrande, R.A. Feline Lymphoma and a High Correlation with Feline Leukaemia Virus Infection in Brazil. J Comp Pathol 2019, 166, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Biezus, G.; Grima de Cristo, T.; da Silva Casa, M.; Lovatel, M.; Vavassori, M.; Brüggemann de Souza Teixeira, M.; Miletti, L.C.; Maciel da Costa, U.; Assis Casagrande, R. Progressive and Regressive Infection with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) in Cats in Southern Brazil: Prevalence, Risk Factors Associated, Clinical and Hematologic Alterations. Prev Vet Med 2023, 216. [CrossRef]

- Buijs, P.R.A.; Van Amerongen, G.; Van Nieuwkoop, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Van Run, P.R.W.A.; Kuiken, T.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Van Eijck, C.H.J.; Van Den Hoogen, B.G. Intravenously Injected Newcastle Disease Virus in Non-Human Primates Is Safe to Use for Oncolytic Virotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther 2014, 21, 463–471. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.B.; Pomeroy, B.S.; Schrall, K.; Park, ; W E; Lindeman, R.J. An Outbreak of Conjunctivitis Due to Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) Occurring in Poultry Workers. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health 1952, 42. [CrossRef]

- Fiola, C.; Peeters, B.; Fournier, P.; Arnold, A.; Bucur, M.; Schirrmacher, V. Tumor Selective Replication of Newcastle Disease Virus: Association with Defects of Tumor Cells in Antiviral Defence. Int J Cancer 2006, 119, 328–338. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Sun, T.K.; Chen, M.S.; Munir, M.; Liu, H.J. Oncolytic Viruses-Modulated Immunogenic Cell Death, Apoptosis and Autophagy Linking to Virotherapy and Cancer Immune Response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Castano, S.; Sanchez-Aparicio, M.T.; García-Sastre, A.; Villar, E. The Therapeutic Effect of Death: Newcastle Disease Virus and Its Antitumor Potential. Virus Res 2015, 209, 56–66. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).