1. Introduction

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a naturally occurring lentivirus that infects domestic cats and is associated with life-long viral persistence and a progressive immunopathology. FIV infection of domestic cats is an important animal model of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) pathogenesis [

1,

2,

3] and these two viruses are phylogenetically related [

4].

FIV infection of cats is characterized by 3 sequential stages including an acute viremic stage, a prolonged asymptomatic phase, and a terminal immunodeficiency stage [

1]. The acute phase begins 1-4 weeks after initial FIV infection, may span a time period of 2-6 months [

5] and is characterized by fever, diarrhea and generalized lymphadenopathy [

6]. Although readily detectable during the initial acute phase of infection, plasma viremia becomes generally undetectable during the asymptomatic phase of infection [

7], which can last for multiple years or for a significant proportion of the remaining life span of the cat [

5,

6]. Although there is a progressive decline in peripheral blood CD4+ cells throughout the asymptomatic phase, infected cats generally remain clinically healthy [

5,

8,

9]. The terminal immunodeficiency stage of disease has also been referred to as feline acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (FAIDS) [

8,

10,

11]. Literature suggests that FIV-infected cats in the terminal phase of infection develop AIDS related complex symptoms including reemergence of generalized lymphadenopathy (lymphadenomegaly), severe wasting, opportunistic infections (cryptococcosis, toxoplasmosis and a variety of viral infections), neoplasia (especially lymphoma), neurological abnormalities, anemia and leukopenia [

5,

12]. FIV infection has also been associated with various diseases of the oral cavity [

13,

14,

15]. Viral loads have been reported to increase during the terminal phase and survival time is usually less than one year after the onset of FAIDS [

5].

There is controversy regarding the clinical relevance of FIV in naturally infected cats [

16] as some investigators believe that FIV itself does not cause severe clinical disease, and FIV-infected cats live many years without any health problems [

17]. In a recent single institution study of mortality in 3108 cats that underwent a postmortem examination, FIV status was determined to not be associated with decreased longevity [

18]. This clinical disconnect between experimental and naturally acquired FIV infection has not been adequately explained. Importantly, although the acute and early asymptomatic stages of experimental FIV infection have been extensively studied, the terminal stage of experimental infection has not, possibly because of the expense of maintaining a group of experimentally infected animals for protracted periods of time.

We experimentally infected a cohort of 4 specific pathogen free (SPF) cats with a biological isolate of FIV clade C and serially monitored these animals, along with 2 uninfected control cats, in an SPF feline research facility at the University of California, Davis for more than 13 years from the time of inoculation to death. Three of the infected cats became FIV progressor animals while one became a long term non-progressor (LTNP) animal, immunologically indistinguishable from the uninfected control cats. We found that FIV establishes a latent infection in peripheral CD4 cells and an active infection in circulating monocytes [

7]. We also found that CD4 cellular latency was associated with epigenetic modification of histone proteins physically associated with the FIV 5’ long terminal repeat (LTR, viral promoter) [

19,

20]. Despite the absence of detectable viral replication within circulating CD4 cells, peripheral CD4 cell numbers precipitously declined in the progressor animals [

21,

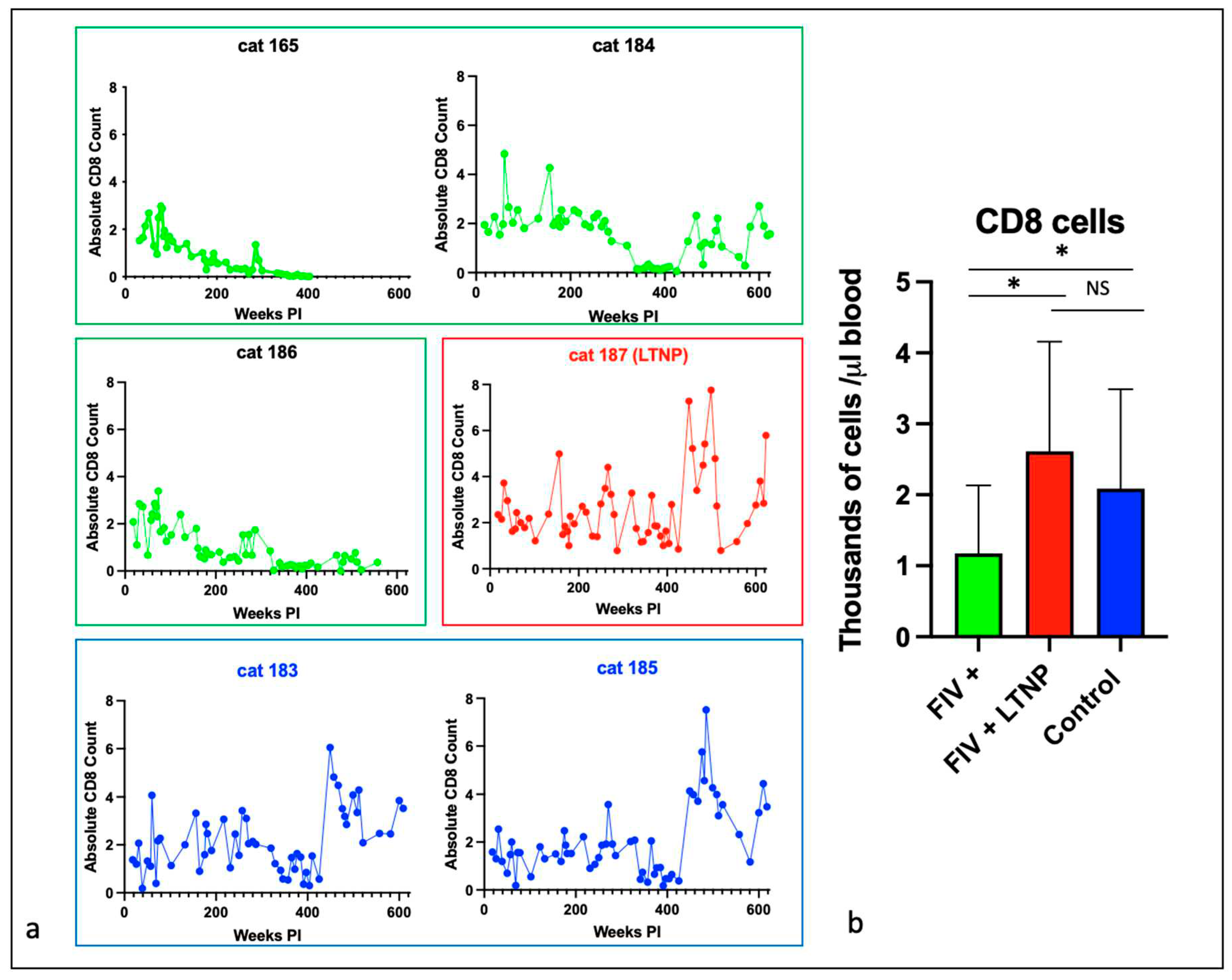

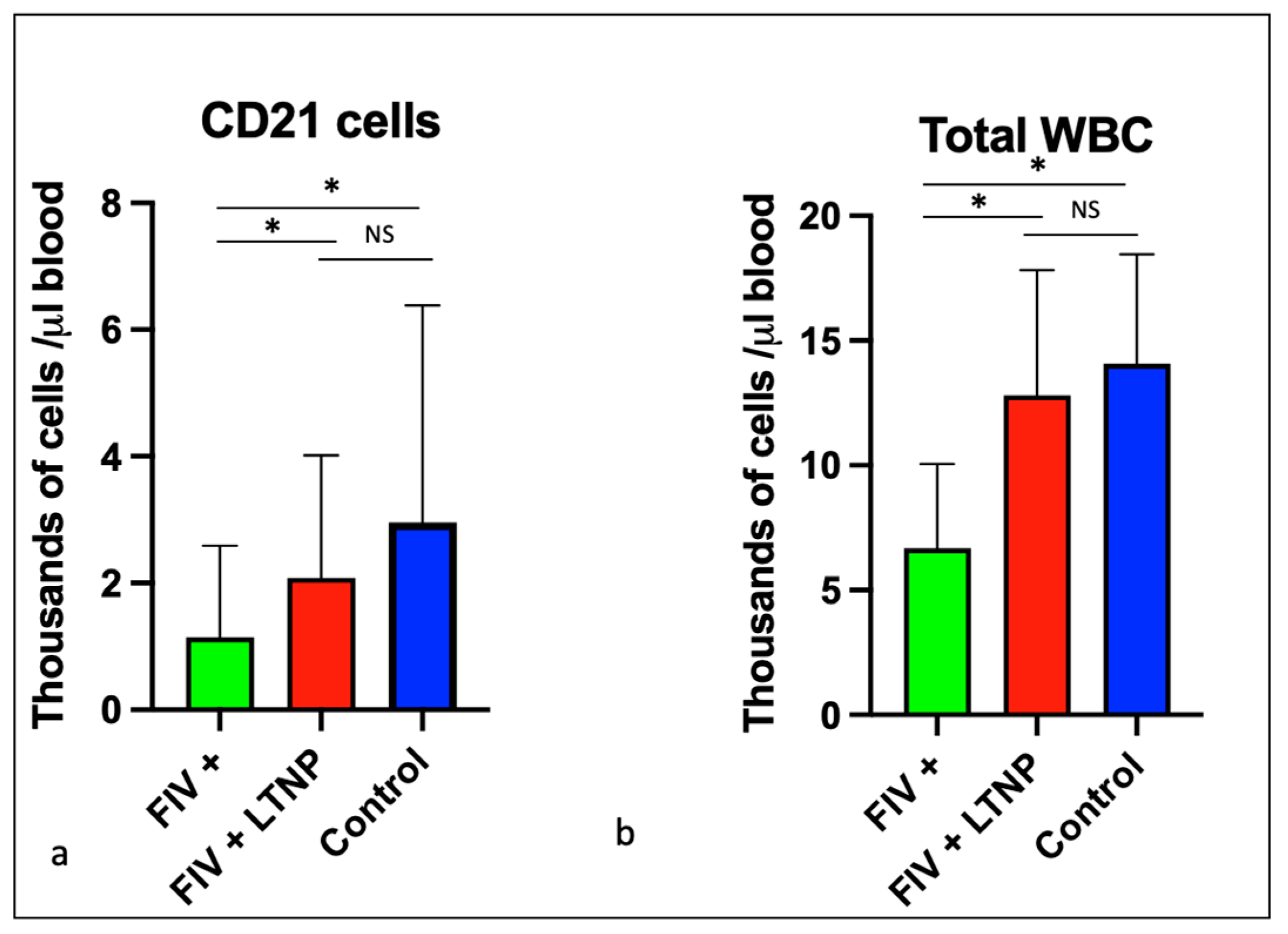

22]. We also identified a progressive loss of both CD8 and CD20 lymphocytes [

21] and a concurrent increase in CD11b monocytes [

22].

In our cohort of experimentally infected progressor cats, the proviral LTR and

gag sequences derived from peripheral leukocytes was determined to be unstable over time, despite low to undetectable viral replication in the peripheral blood [

23]. No variation from the inoculating viral sequence was identified in the proviral LTR derived from CD4 cells isolated from the peripheral blood and lymph nodes of the LTNP cat [

23]. A survival study focused on surgical biopsies of central lymph node, spleen and small intestine revealed that these tissues support ongoing viral replication, despite highly restricted viral replication in peripheral blood [

22].

Serial immunologic and virologic monitoring of each animal continued until predetermined clinical criteria were met requiring humane euthanasia. At the terminal phase of disease, the cats eventually succumbed to either lymphoma or chronic renal disease. The single LTNP cat outlived the three progressor animals. The LTNP cat was eventually euthanized for chronic renal disease that was clinically indistinguishable from one of the uninfected control animals. None of the FIV-infected cats had any evidence of terminal opportunistic infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and pathology

Six FIV specific pathogen free kittens were purchased in 2009 from the breeding colony of the Feline Nutrition and Pet Care Center, University of California, Davis (UC Davis). At the time of purchase, kittens ranged in age from 4 to 5 months and were housed in the Feline Research Laboratory of the Center for Companion Animal Health, UC Davis. Four kittens were intramuscularly inoculated with FIV-C-Pgmr viral inoculums (kittens 165, 184, 186 and 187) and two control kittens (183 and 185) were mock-inoculated intramuscularly with 1 ml of sterile culture media and monitored as previously described [

13]. The FIV-C-Pgmr biological isolate was provided by Drs. E. Hoover (Colorado State University) and N. Pedersen (University California, Davis). The experimental study protocols were approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC 21706). The cats were monitored and housed as two separate cohorts in an SPF facility (FIV infected/uninfected, Feline Research Laboratory) throughout their lives. The rooms had multiple perches and a variety of cat toys and boxes for enrichment, play and exercise. The cats were fed, observed and litter boxes changed daily. Room lighting cycles were seasonally adjusted.

Periodic physical examinations, chemistry panels, complete blood counts and urinalyses were performed dependent upon clinical signs. Humane criteria for euthanasia were established by the principal investigator (Murphy) in collaboration with Campus Veterinary Services and were approved by IACUC. The euthanasia criteria included a combination of the following: severe clinical signs for at least one month that were not responsive to treatment, prolonged anorexia resulting in greater than 20% loss of optimal body weight, a hematocrit less than 15% for two consecutive measurements, dehydration requiring fluid therapy 3 or more times in a 7-day period, or a hematological malignancy. A goal was to not prematurely euthanize any cat for a disease process determined to be treatable or recoverable. Euthanasia was performed by intravenous administration of phenytoin sodium/pentobarbitol sodium (Beuthanasia, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) administered at >100 mg/kg body weight. A complete necropsy and tissue collection was performed for each cat within 1-5 hours of euthanasia.

Gross lesions were identified and described during the necropsy examination and a complete set of tissues was collected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for microscopic examination. In addition, two additional sets of fresh tissue samples were collected, including brain, lymph node, bone marrow, small intestine, and spleen (<1 g tissue per sample). Tissues from one of these sets were packaged into individual Whirl-Pac bags (Nasco, Toronto, ON, USA) and archived at −80 C. Tissues from the other sample set were placed into individual sterile microcentrifµge tubes containing 1.5 mL RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and frozen at −20 C. Formalin-fixed tissues were trimmed, placed in cassettes, routinely paraffin embedded, and processed for 5 μm-thick sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All resulting histopathology slides were examined by veterinary anatomic pathologists (Murphy, Eckstrand, Cook).

2.2. Isolation and Enumeration of Peripheral Leukocytes

Monthly peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plasma were harvested from whole blood in EDTA or heparin by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) density gradient centrifugation. Plasma was archived at -80C until further utilized. The total number of peripheral white blood cells (total WBC) was serially determined as described previously, using either an automated Coulter Counter (Coulter ACT Diff, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) or LeukoCheck Kit (Biomedical Polymers, Inc., Gardner, MA, USA) and manual hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA, USA) [

24,

25]. The relative proportions of specific peripheral leukocyte subsets were determined by flow cytometry from 100 μL of whole blood, as described previously [

25]. This procedure utilized the following antigen-specific antibodies, anti-feline CD4 (clone FE1.7B12), anti-feline CD8 (clone FE1.10E9), and anti-canine CD21 (B cells, clone CA2.1D6). All of the antibodies were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. P. Moore (UC Davis). Absolute cell counts were calculated by multiplying the total WBC count by the percent of cells expressing the specific antigen marker. CD4 cells were isolated from feline PBMC by immunomagnetic columns as described previously [

7].

2.3. Isolation, Quantification, and Sequencing of Viral Nucleic Acids

Serial attempts were made to isolate viral RNA from clarified plasma and amplify it using real-time RT-PCR, as described previously [

25]. Quantification of plasma viral RNA was based on a standard curve generated from viral transcripts, prepared by in-vitro transcription of a plasmid (pCR2.1, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing a 101 nucleotide FIV-C

gag amplicon [

7]. The amount of FIV gag RNA was expressed relative to volume of blood (mL).

DNA and RNA were isolated from frozen abdominal (mesenteric) lymph node archived in RNAlater at the time of necropsy examination and stored at -20C until utilized. For each node, approximately 30 mg of tissue was thawed on ice and mechanically disrupted, using a disposable Closed Tissue Grinder System (02-542-09, Fisher scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in Buffer RLT with β-mercaptoethanol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The disrupted tissue was subsequently homogenized using a QIAshredder column (Qiagen), and RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue-associated RNA was DNAse treated and reverse-transcribed to cDNA, as described previously [

7]. The number of cells associated viral DNA and viral RNA (cDNA) was quantified and normalized to cellular GAPDH via real-time PCR, as described previously [

7]. The real-time PCR assay has a detection limit of approximately 10 copies of FIV

gag-complementary DNA (cDNA) per tissue sample, or 8 × 10

2 copies of FIV

gag cDNA per mL plasma [

23].

A proviral subgenomic fragment containing the long terminal repeat (LTR) and the first ~1000 nucleotides of the FIV leader,

gag capsid (CA) and 5’ terminus of

gag matrix (MA) were PCR amplified from genomic DNA isolated from PBMC, peripheral CD4 cells and lymph node and cloned using a commercial system (pCR2.1 TA cloning system, Invitrogen) [

25]. Plasmid DNA was purified using a commercial kit (Promega) and sequenced by a local vendor (Davis Sequencing, Davis, CA).

Viral sequences were analyzed for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, and deletions relative to the inoculating viral sequence. Viral sequences were determined at multiple time points throughout the infection. Nucleotide sequence of the initial FIV-C-Pgmr virus was determined from cDNA generated from inoculum viral RNA. Viral sequences were aligned and compared using MacVector 18.0 software (MacVector, Inc., Apex North Carolina).

2.4. Antibody studies

Serial plasma samples were isolated by centrifugation from anticoagulant treated whole blood (EDTA or heparin) and archived at -80C until utilized for serological assays using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) as described below. Feline plasma was assessed for 1. immunoglobulin specificity to a variety of FIV antigens and the viral host cell receptor; and 2. FIV-specific immunoglobulin isotypes.

2.5. Specificity to FIV antigens and CD134 host cell receptor

Three FIV antigens (Gag p24, Env SU and Env TM) and the primary FIV binding receptor, CD134 (OX40), were individually coated onto the wells of a 96-well ELISA plate (all antigens were obtained from Custom Monoclonals, Sacramento, CA). Each antigen was diluted in coating buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 9.6) at 0.3 µg/well, 0.3 µg/well, 0.15 µg/well and 0.15 µg/well, for p24, SU, TM and CD134, respectively. 100 µL of each antigen was aliquoted into each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature (RT) overnight. Coated wells were washed twice with PBS-T wash solution (1 liter phosphate buffered saline, 1 mL tween 20) and 100 µL of feline plasma was added to each well to a final dilution of 1:300 in PBS-T/BSA (28 mL PBS/T, 2 mL 7.5% bovine serum albumin). Plates were incubated 45 minutes at RT and washed three times with PBS-T. One hundred µL of murine anti-cat IgG (GPB2-2B1, BioRad) was added at 1.0 µg/well diluted in PBS-T/BSA, incubated 45 minutes at RT, and washed 3 times with PBS-T. One hundred µL of goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (BioRad) was added at 1:1000 dilution in PBS-T/BSA to each well, incubated 45 minutes at RT, and washed 3 times with PBS-T. The plate was developed with the HRP substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD, Thermo Scientific) using standard protocols and 12 minutes of incubation at RT. The reaction was stopped with 2M H2SO4 and scanned for absorbance at 493 nm with a plate reader. One hundred optical density units of background was subtracted from the reading of each well.

2.6. FIV-specific immunoglobulin isotypes

To determine the relative amount of isotype-specific anti-FIV antibody in each plasma sample, a set of ELISA reactions were conducted with plates coated with FIV virus and utilized a set of murine anti-cat isotype specific monoclonal antibodies. Target FIV virus was harvested from Crandell-Rees Feline Kidney (CRFK) cells infected with FIV-petaluma. The virus-containing culture supernatant was centrifuged and cell-free fluid harvested, diluted 1:2 in coating buffer (0.1M sodium carbonate, pH 9.6) and 100µL/well was applied to an ELISA plate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and incubated overnight at 4C. Virus-coated wells were washed twice with PBS-T and feline plasma samples added to each well to a final dilution of 1:300, as described above. Plates were incubated 45 minutes at RT, washed three times, and 100µL of murine anti-isotype antibody was added per well (FDG1-2A1 anti-IgG, anti-IgG kappa, IgA9-6A anti-IgA or CM7 anti-IgM, all from Custom Monoclonals, Sacramento, CA) at 1.0 µg/ well and incubated for one hour at RT. Wells were then washed, treated with goat anti-mouse peroxidase conjugate, developed with OPD reagent, and scanned for absorbance with an ELISA plate reader, as described above.

2.7. Statistical Tests

Graphical numerical data is presented as the mean of three or more values, with the standard deviation or range represented by error bars. Statistical differences were determined by unpaired Student’s t-tests. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistics were performed with Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

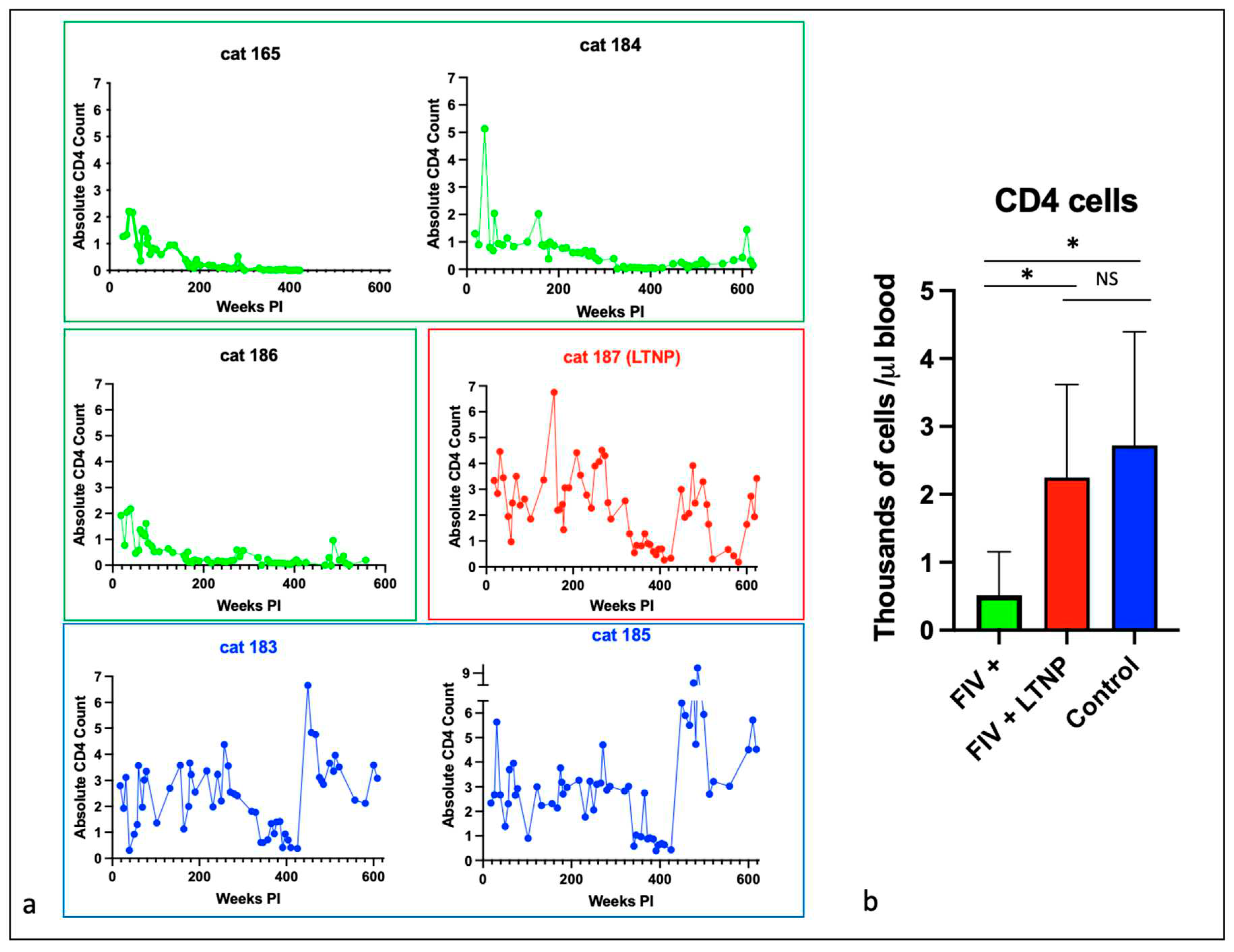

In progressor animals, experimental infection with FIV lentivirus resulted in a progressive and profound immunodeficiency characterized by an initial loss of peripheral CD4 lymphocytes [

7], and eventually followed during the mid to late asymptomatic phase by loss of both CD8 and CD21 lymphocyte subsets. Although the U.S. Center for Disease Control definition of Stage 3 AIDS in human patients (< 200 CD4 lymphocytes/µL blood; CDC.gov) is satisfied in FIV progressor cats, these cats nevertheless enter a prolonged asymptomatic phase featuring minimal to no clinical morbidity. During the late asymptomatic phase, the three progressor cats in this study, 165, 184 and 186, all had average CD4 counts less than 200 cells/µL blood for 200 or more weeks (~4 years) without clinical evidence of substantive morbidity.

There is an apparent disconnect between humans infected with HIV and cats infected with FIV. Although both lentiviruses are associated with comparable lymphocyte depletion in their mammalian hosts, for undetermined reasons, the clinical effect of profound CD4 depletion on the feline host’s overall health is much attenuated relative to human patients. As a result, the asymptomatic phase is prolonged and the terminal (FAIDS) stage of FIV infection is relatively short. It is notable that this cohort of experimentally FIV-infected cats was housed and maintained in a controlled environment and protected from exposure to other animals at the UC Davis Feline Research Laboratory. In a somewhat analogous manner, client-owned FIV-positive cats isolated from exposure to other cats and maintained indoors likely have limited exposure to infectious microbial agents. It is therefore possible that restricted exposure to pathogens in such “protected” animals might help explain why FIV infection does not seem to have a clinically relevant effect in naturally infected cats [

17] and the conundrum of a lack of evidence for opportunistic infections in the face of profound lymphopenia.

CRF, often attributed to renal atrophy and tubulointerstitial nephritis, is common in aged cats, and most client-owned domestic cats older than 10 years of age have evidence of some degree of renal inflammation and parenchymal loss (personal observation, BGM). Three of the cats in this study, progressor 186, LTNP 187 and control cat 183, were euthanized due to CRF-associated morbidity. The cause of CRF in domestic cats is controversial and likely multifactorial, but a direct etiological role for FIV in CRF would seem unlikely.

The mechanism of lymphomagenesis in FIV-infected cats is controversial and both direct (insertional mutagenesis) and indirect mechanisms (impaired immunosurveillance) have been proposed. In a study examining the rapid occurrence of lymphoma in 4 experimentally FIV-infected cats, the investigators reached the conclusion that neoplastic pathogenesis was secondary to FIV immune dysregulation [

28]. Our research group reached the same conclusion of an indirect role for FIV in the pathogenesis of lymphoma for progressor cat 165 [

21].

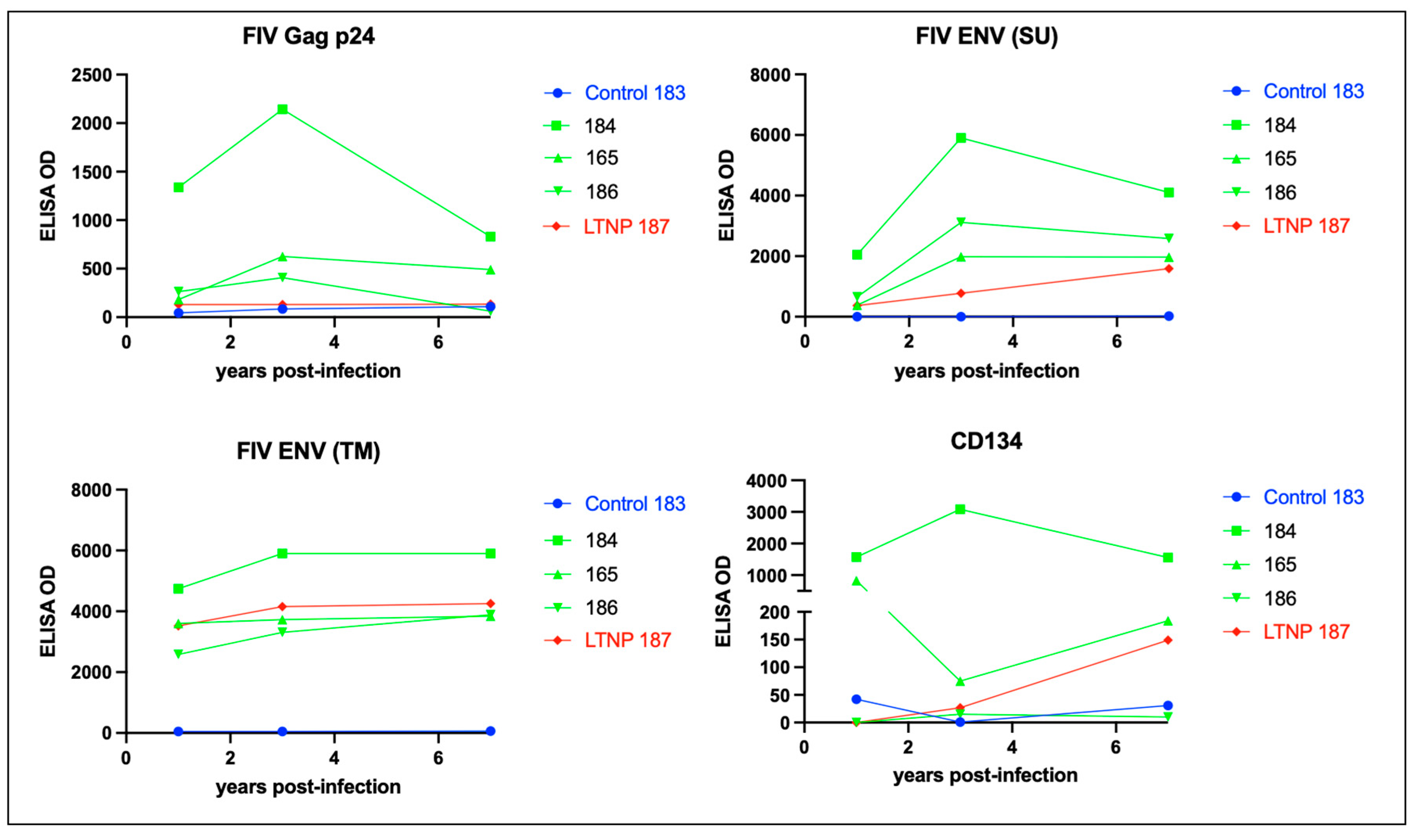

Studies have indicated that antibodies directed against CD134 have been associated with improved health and survival as these antibodies have been shown to indirectly block FIV entry

ex vivo and the presence of antibodies to CD134 have been associated with lower viral loads [

35]. As a result, we were interested to determine the anti-CD134 status in our FIV infected cohort. Unexpectedly, we found that the LTNP cat 187 did not have elevated CD134 titers relative to the progressors and that cat 184 had the highest titers against CD134. Interestingly, profound CD8 lymphocyte depletion in cat 184 from 340-425 weeks PI eventually recovered to the normal range (500-2500 cells/µL blood) from 450 weeks PI onward. Whether there is any association between this unusual CD8 cell rebound and elevated anti-CD134 titers was not determined.

HIV-infected controllers and long term non-progressor patients have been extensively studied in human medicine [

36,

37]. To our knowledge, cat 187 is one of the few, or perhaps only, experimentally FIV-infected animal that has had consistent, long-term documentation supportive of LTNP status. We have previously defined an FIV LTNP as a persistently asymptomatic animal that maintains a peripheral blood CD4 T cell count indistinguishable from FIV negative control cats [

32]. Our prior investigations have indicated that, relative to the FIV progressors, cat 187 had lower proviral loads in PBMC and tissue (lymph node, LN) and viral RNA was detected at a lower copy number in LNs [

32]. Although it was possible to reactivate replication competent virus from cat 187’s LN, viral reactivation took longer than the 3 progressor cats [

32]. In the data presented here, LTNP 187 had lower immunoglobulin titers directed against Gag p24 and Env (SU) than the FIV progressor cats and we did not identify elevated CD134 titers (“protective antibodies”) in LTNP 187 relative to the FIV progressors. In addition, there was no distinct genetic signature in the amplified proviral LTR or

gag gene (e.g. large deletion or rearrangement) clearly delineating the LTNP from the progressor animals in the tissue and PBMC-derived sequences. The inoculating viral swarm was the same for all the infected animals [

7].

The mechanisms conferring LTNP status have been extensively studied for HIV patients and appear to involve multiple host factors: production/destruction of T cells, IL-7/IL-7R, status of lymphoid architecture, balance of pro-/anti-inflammatory cells, lentivirus-specific immune response, size of the viral reservoir [

37] and host MHC genotype [

38]. Viral genotype affecting replication fitness can also play a role in host control of viral replication [

38]. Extensive data unambiguously show that HIV-1 controllers are immunologically different from progressors in production, destruction, and regulation of CD4 cells [

37]. The mechanism(s) governing LTNP status in FIV-infected cats may involve similar host factors but requires further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, BGM and ES; methodology, DC, SC, CE, CG and SE; data interpretation, BGM, DC, SC, CE, SE, CG and ES; Figures and tables, BGM; writing—original draft preparation, BGM; review and editing, BGM, DC, CE, SE, SC and ES; funding acquisition, BGM, SC, CE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

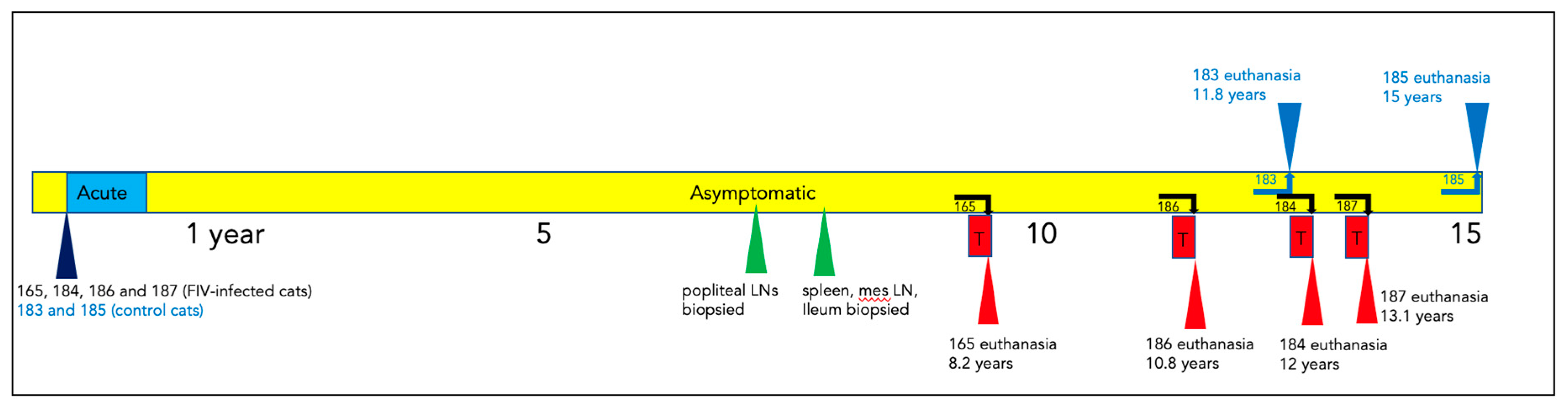

Figure 1.

Clinical timeline for all of the study animals. The acute (blue box), asymptomatic (yellow) and terminal (red) phases of FIV infection are depicted for each animal. Survival surgical biopsy procedures are depicted by green triangles. The age of each animal at the time of euthanasia is indicated (blue and red triangles). Mes LN- mesenteric lymph node.

Figure 1.

Clinical timeline for all of the study animals. The acute (blue box), asymptomatic (yellow) and terminal (red) phases of FIV infection are depicted for each animal. Survival surgical biopsy procedures are depicted by green triangles. The age of each animal at the time of euthanasia is indicated (blue and red triangles). Mes LN- mesenteric lymph node.

Figure 2.

Peripheral CD4 cells decline over time in FIV progressor cats, but not in non-progressor and control animals. (a) The absolute number of peripheral CD4 cells in progressor cats (165, 184, 186- green), long term non-progressor (LTNP, 187, red) and uninfected control cats (183 and 185, blue) are depicted vs. time post infection (PI). (b) The aggregated average of all CD4 lymphocyte data is depicted as a colored bar with standard deviations for progressor (FIV+, green), LTNP (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates a lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

Figure 2.

Peripheral CD4 cells decline over time in FIV progressor cats, but not in non-progressor and control animals. (a) The absolute number of peripheral CD4 cells in progressor cats (165, 184, 186- green), long term non-progressor (LTNP, 187, red) and uninfected control cats (183 and 185, blue) are depicted vs. time post infection (PI). (b) The aggregated average of all CD4 lymphocyte data is depicted as a colored bar with standard deviations for progressor (FIV+, green), LTNP (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates a lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

Figure 3.

Peripheral CD8 cells decline over time in most FIV progressor cats but not in non-progressor and control animals. (a) The absolute number of peripheral CD8 cells in progressor cats (165, 184, 186- green), long term non-progressor (LTNP, 187, red) and uninfected control cats (183 and 185, blue) are depicted vs. time post infection (PI). (b) The aggregated average of all CD8 lymphocyte data is depicted as a colored bar with standard deviations for progressor (FIV+, green), LTNP (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates the lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

Figure 3.

Peripheral CD8 cells decline over time in most FIV progressor cats but not in non-progressor and control animals. (a) The absolute number of peripheral CD8 cells in progressor cats (165, 184, 186- green), long term non-progressor (LTNP, 187, red) and uninfected control cats (183 and 185, blue) are depicted vs. time post infection (PI). (b) The aggregated average of all CD8 lymphocyte data is depicted as a colored bar with standard deviations for progressor (FIV+, green), LTNP (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates the lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

Figure 4.

CD21 cells and total white blood cells are reduced in progressor cats relative to non-progressor and control animals. The aggregated average and standard deviations of (a) peripheral CD21 cells (b) and total WBC for progressor cats (FIV+, green), long term non-progressor (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates the lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

Figure 4.

CD21 cells and total white blood cells are reduced in progressor cats relative to non-progressor and control animals. The aggregated average and standard deviations of (a) peripheral CD21 cells (b) and total WBC for progressor cats (FIV+, green), long term non-progressor (red) and control animals (blue). An asterisk indicates a significant difference of means (*, p<.05) while NS indicates the lack of a significant difference (p>.05, Not Significant).

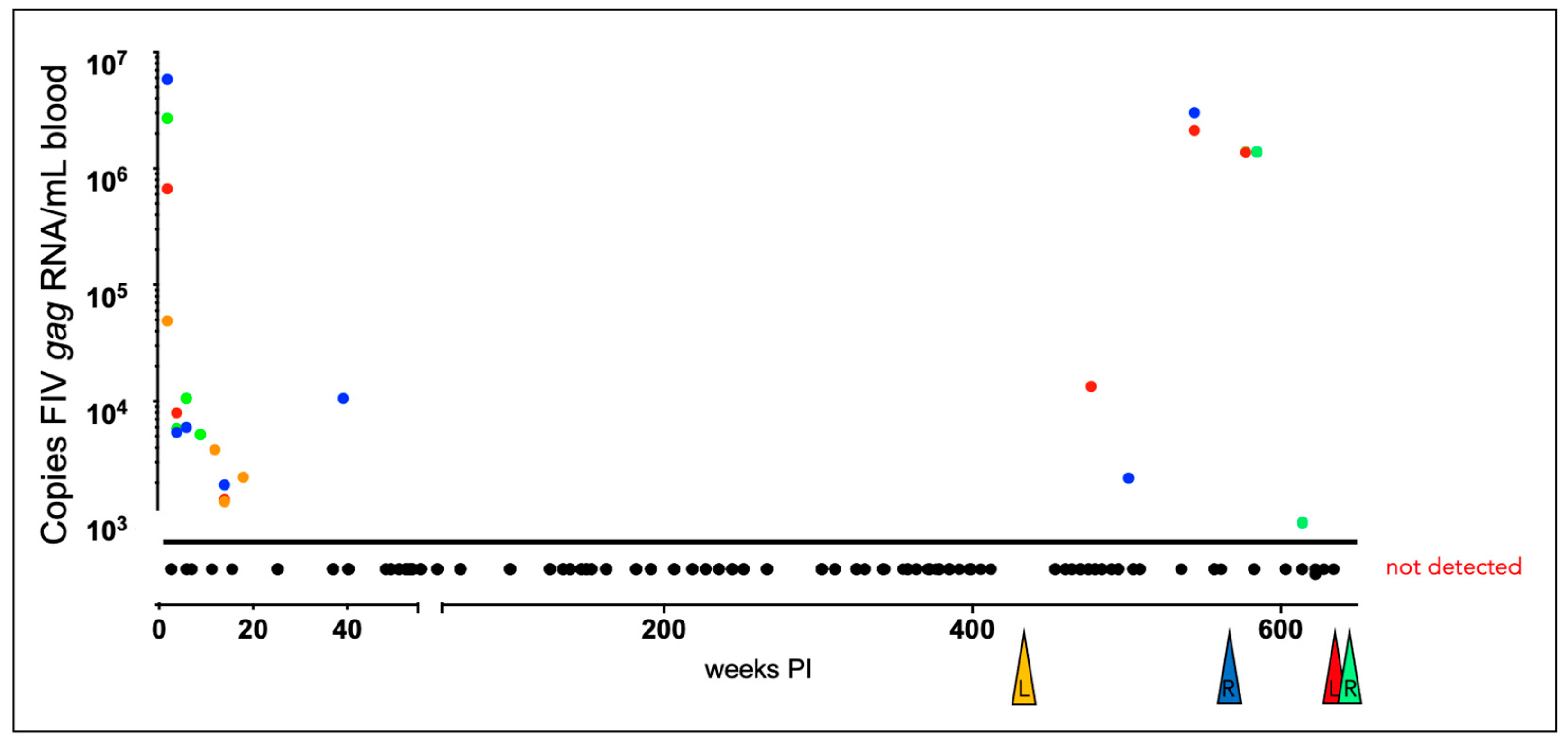

Figure 5.

Viral gag RNA is detectable in all of the FIV-infected cats during the acute and late asymptomatic phases of infection. Real time RT-PCR data from individual cats are indicated by color: yellow (165), green (187), 184 (red), 186 (blue). Samples are plotted as copies FIV gag RNA/mL blood vs. the number of weeks post infection (PI). Samples below the limit of detection (not detected, 800 copies RNA/ml blood) are plotted below the x-axis and colored triangles indicate the time of euthanasia for each FIV-infected animal (L-lymphoma; R- renal failure).

Figure 5.

Viral gag RNA is detectable in all of the FIV-infected cats during the acute and late asymptomatic phases of infection. Real time RT-PCR data from individual cats are indicated by color: yellow (165), green (187), 184 (red), 186 (blue). Samples are plotted as copies FIV gag RNA/mL blood vs. the number of weeks post infection (PI). Samples below the limit of detection (not detected, 800 copies RNA/ml blood) are plotted below the x-axis and colored triangles indicate the time of euthanasia for each FIV-infected animal (L-lymphoma; R- renal failure).

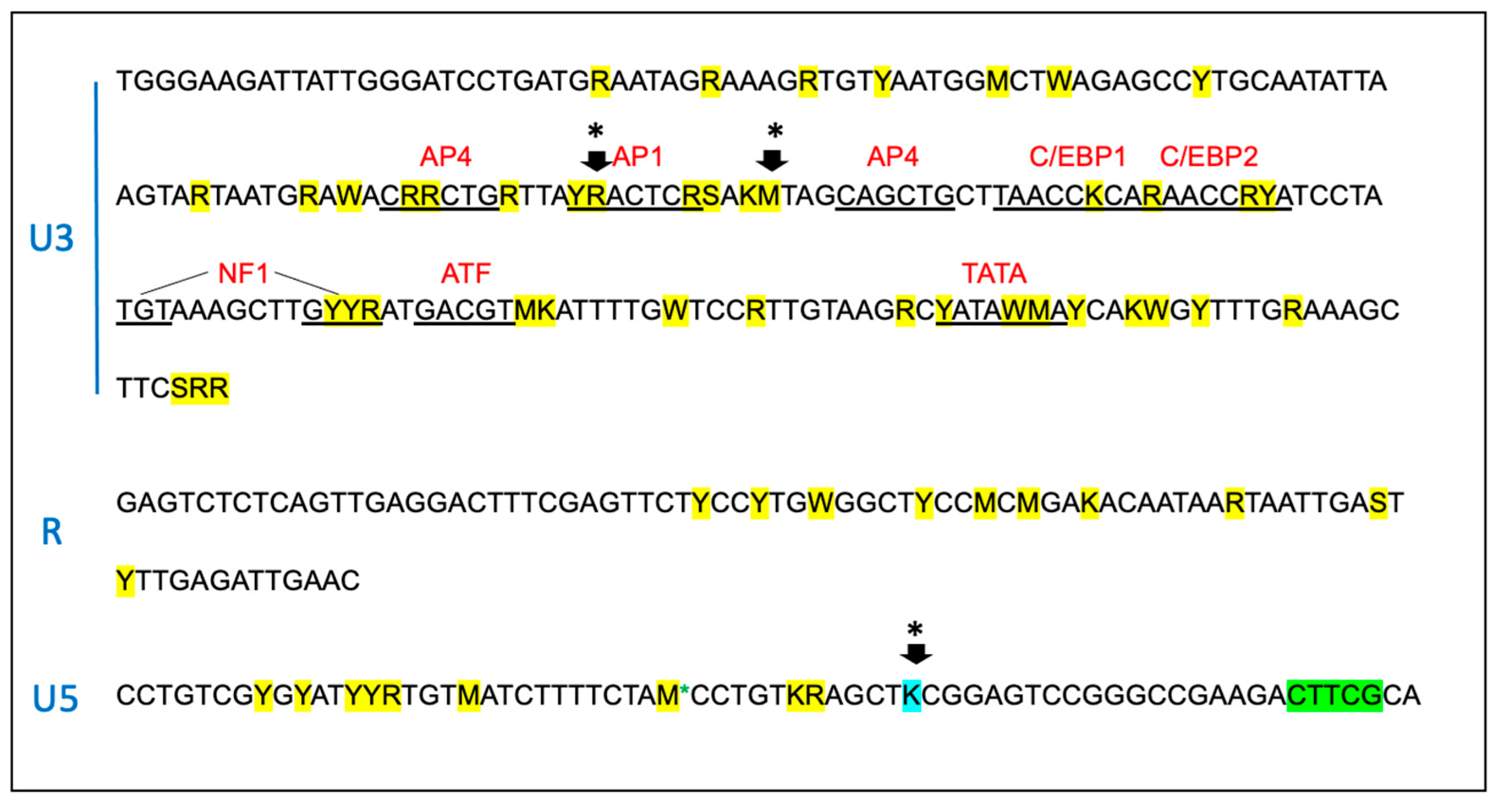

Figure 6.

The sequence of the proviral promoter amplified from the tissues of the FIV-infected cats is unstable over time. The sequence of the entire long terminal repeat (LTR) is depicted for the inoculating virus. SNPs identified within the amplified and cloned sequences of tissue-derived provirus are indicated by yellow highlights, green indicates a block of deleted nucleotides in the U5 region and blue indicates a SNP in the inoculating viral sequence. Short arrows with an asterisk (*) represents common SNPs isolated from multiple cats at multiple time points. The standard IUPAC nucleotide code is used. Recognized transcription factor binding motifs are indicated in red. .

Figure 6.

The sequence of the proviral promoter amplified from the tissues of the FIV-infected cats is unstable over time. The sequence of the entire long terminal repeat (LTR) is depicted for the inoculating virus. SNPs identified within the amplified and cloned sequences of tissue-derived provirus are indicated by yellow highlights, green indicates a block of deleted nucleotides in the U5 region and blue indicates a SNP in the inoculating viral sequence. Short arrows with an asterisk (*) represents common SNPs isolated from multiple cats at multiple time points. The standard IUPAC nucleotide code is used. Recognized transcription factor binding motifs are indicated in red. .

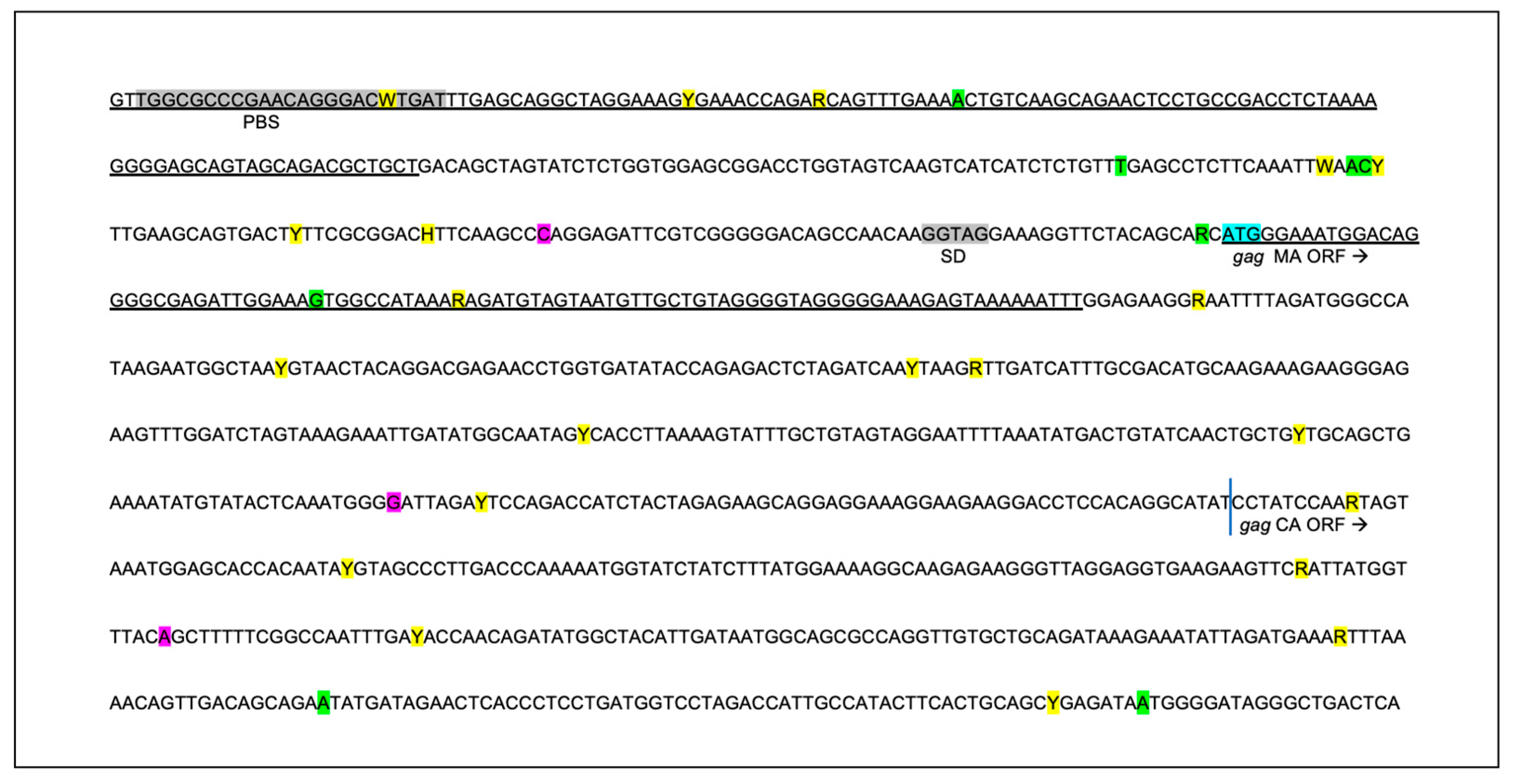

Figure 7.

The sequence of the 5’ aspect of the proviral gag region amplified from the tissues of the FIV-infected cats is unstable over time. Approximately 1000 nucleotides of the FIV gag gene encompassing the primer binding site (PBS), gag matrix (MA) and gag capsid (CA) are indicated. Sequences known to be important for efficient encapsidation are underlined and the splice donor site (SD) is indicated in grey. SNPs are indicated by yellow highlight, deletions by green and insertions are indicated by purple. The initiating ATG codon for gag matrix (MA ORF) is indicated by blue highlight. The standard IUPAC nucleotide code is used. .

Figure 7.

The sequence of the 5’ aspect of the proviral gag region amplified from the tissues of the FIV-infected cats is unstable over time. Approximately 1000 nucleotides of the FIV gag gene encompassing the primer binding site (PBS), gag matrix (MA) and gag capsid (CA) are indicated. Sequences known to be important for efficient encapsidation are underlined and the splice donor site (SD) is indicated in grey. SNPs are indicated by yellow highlight, deletions by green and insertions are indicated by purple. The initiating ATG codon for gag matrix (MA ORF) is indicated by blue highlight. The standard IUPAC nucleotide code is used. .

Figure 8.

FIV-infected cats mount a strong humoral response against Env TM and a variably strong response to Env SU, Gag p24 and CD134. ELISA titers are plotted against time post-infection for the FIV progressors (green), non-progressor (red) and uninfected control (blue). The non-progressor cat (LTNP 187) has a high Env TM antibody titer and a relatively weak humoral response against Env-SU, Gag p24 and the primary FIV receptor CD134.

Figure 8.

FIV-infected cats mount a strong humoral response against Env TM and a variably strong response to Env SU, Gag p24 and CD134. ELISA titers are plotted against time post-infection for the FIV progressors (green), non-progressor (red) and uninfected control (blue). The non-progressor cat (LTNP 187) has a high Env TM antibody titer and a relatively weak humoral response against Env-SU, Gag p24 and the primary FIV receptor CD134.

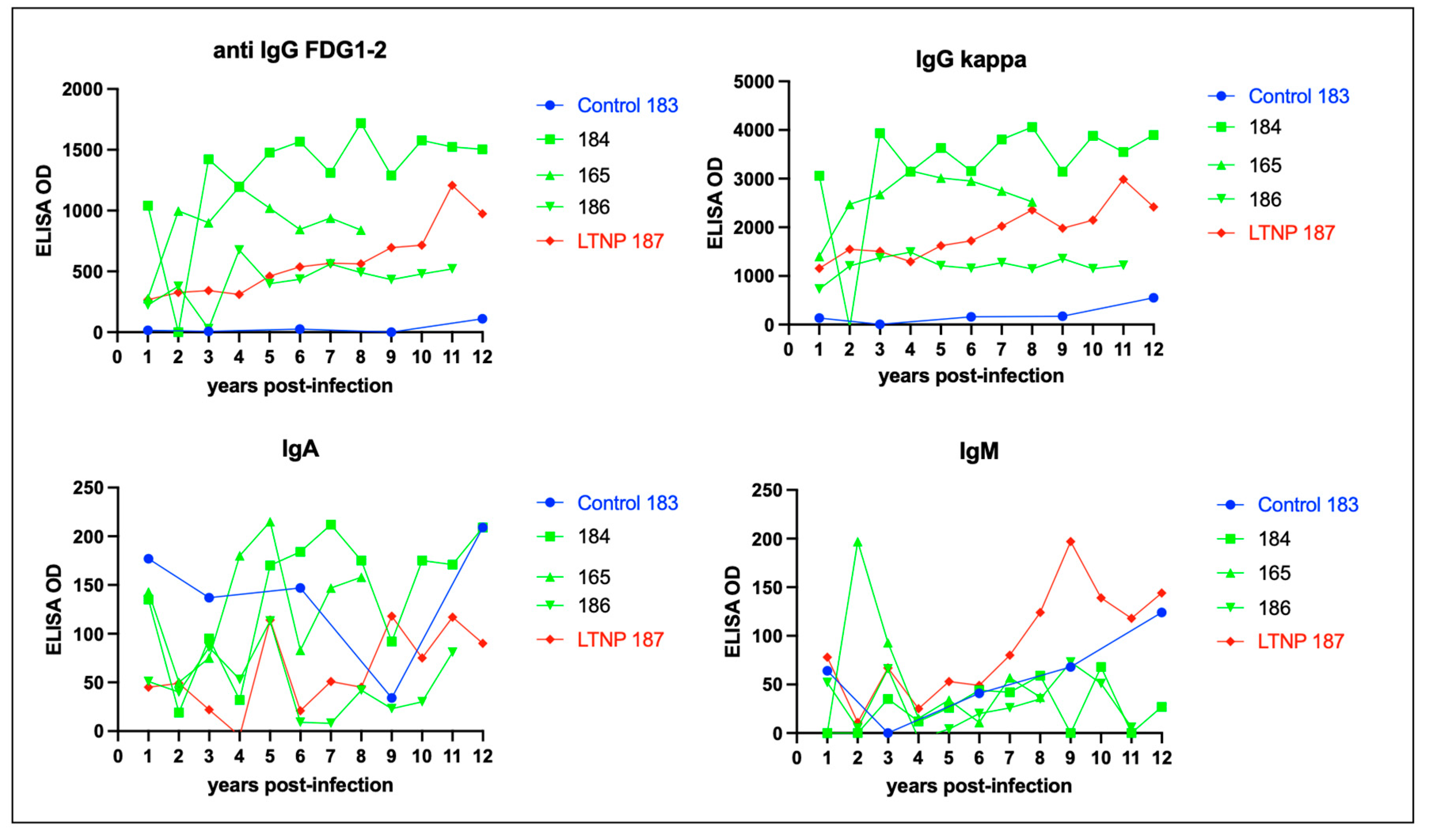

Figure 9.

The isotype of the humoral response against FIV is IgG, and not IgA or IgM. ELISA titers for anti-FIV IgG (FDG1-2 and kappa), IgA and IgM are plotted against time post-infection for the FIV progressors (green), non-progressor (red) and uninfected control (blue). .

Figure 9.

The isotype of the humoral response against FIV is IgG, and not IgA or IgM. ELISA titers for anti-FIV IgG (FDG1-2 and kappa), IgA and IgM are plotted against time post-infection for the FIV progressors (green), non-progressor (red) and uninfected control (blue). .

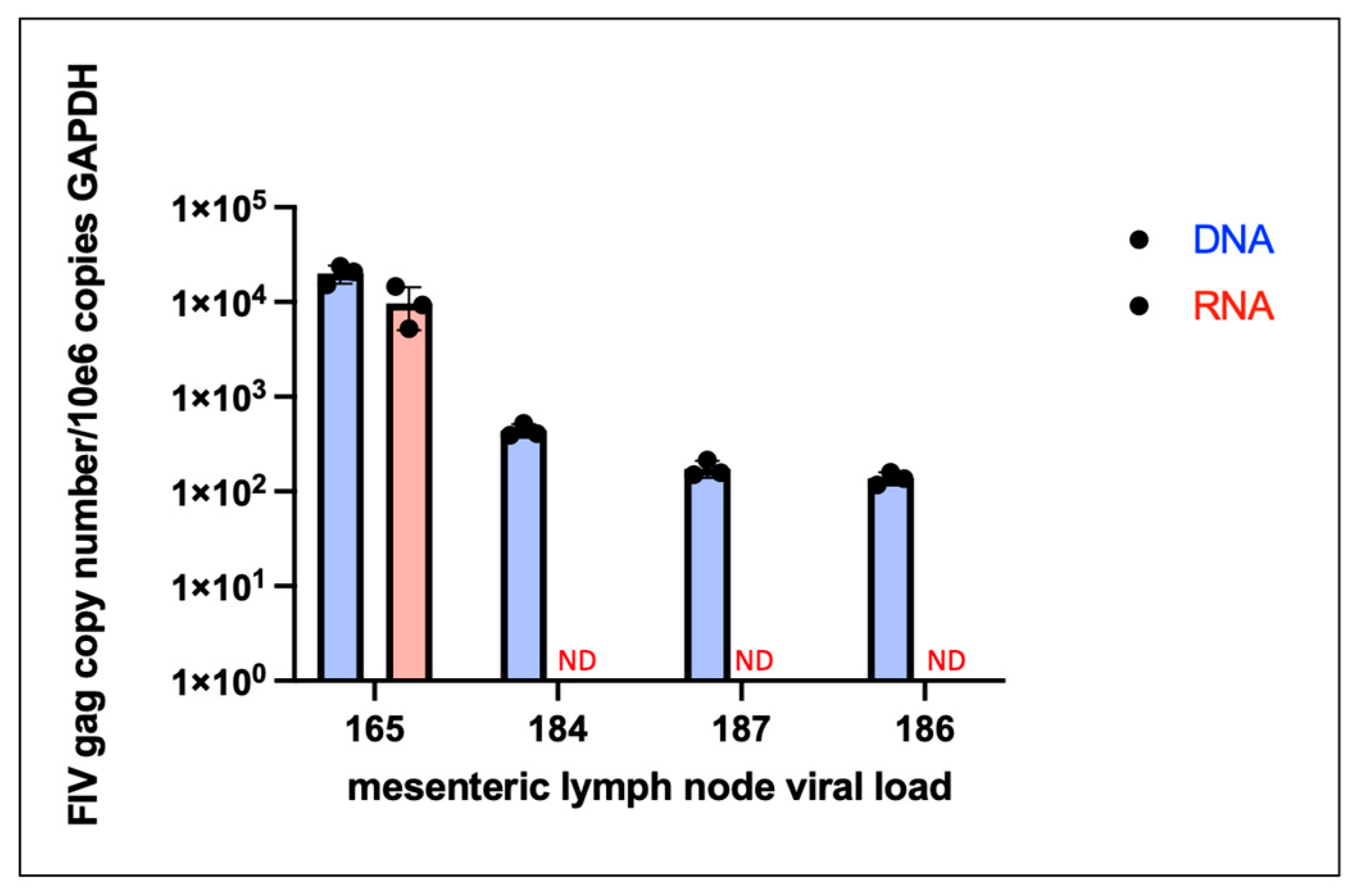

Figure 10.

Proviral DNA (blue bars) is detected in the mesenteric lymph node tissue in all of the FIV infected cats while viral RNA (cDNA, pink bar) is only detectable in the LN tissue of progressor cat 165. Mesenteric lymph node was harvested at the time of necropsy. Real time PCR data is normalized to copies of host feline GAPDH. ND- not detected.

Figure 10.

Proviral DNA (blue bars) is detected in the mesenteric lymph node tissue in all of the FIV infected cats while viral RNA (cDNA, pink bar) is only detectable in the LN tissue of progressor cat 165. Mesenteric lymph node was harvested at the time of necropsy. Real time PCR data is normalized to copies of host feline GAPDH. ND- not detected.

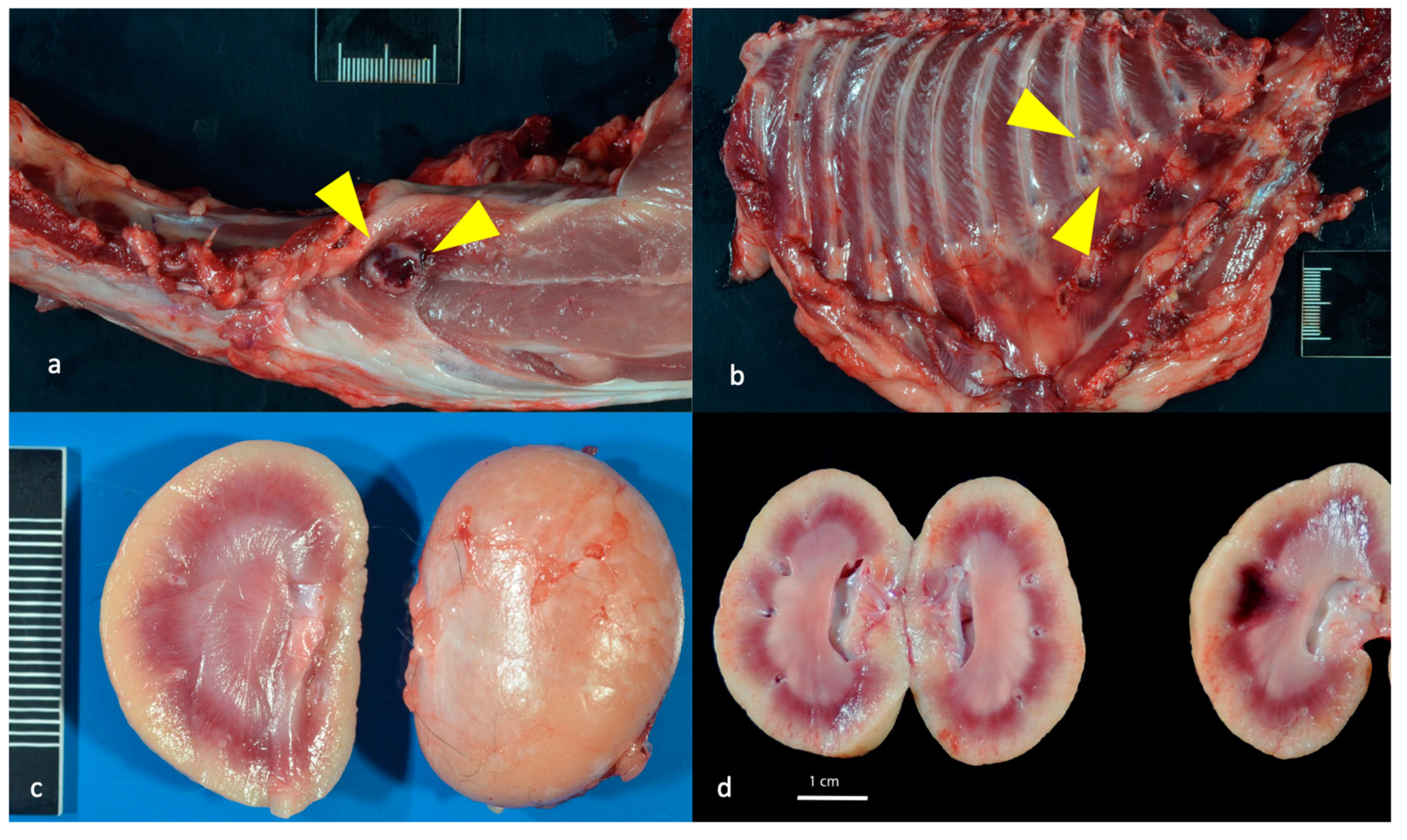

Figure 11.

Gross lesions identified at the time of necropsy include lymphoma and renal atrophy. (a and b) Discrete, purple to tan neoplastic nodules identified within the diaphragm and intercostal musculature of progressor cat 184 are depicted by yellow triangles. (c) Bilateral kidneys of control cat 183 were small firm and rounded. The right kidney is 6.8 grams and is 3 x 2.7 x 2.5 cm (renal atrophy). (d) In progressor cat 186, bilateral kidneys are moderately atrophied with an undulating cortical surface. Bilateral kidneys have multiple, small (less than 1 mm) diameter cyst-like structures in the outer cortical parenchyma and the right kidney has a pale, bulging outer cortex and a dark purple inner cortex (acute infarct).

Figure 11.

Gross lesions identified at the time of necropsy include lymphoma and renal atrophy. (a and b) Discrete, purple to tan neoplastic nodules identified within the diaphragm and intercostal musculature of progressor cat 184 are depicted by yellow triangles. (c) Bilateral kidneys of control cat 183 were small firm and rounded. The right kidney is 6.8 grams and is 3 x 2.7 x 2.5 cm (renal atrophy). (d) In progressor cat 186, bilateral kidneys are moderately atrophied with an undulating cortical surface. Bilateral kidneys have multiple, small (less than 1 mm) diameter cyst-like structures in the outer cortical parenchyma and the right kidney has a pale, bulging outer cortex and a dark purple inner cortex (acute infarct).

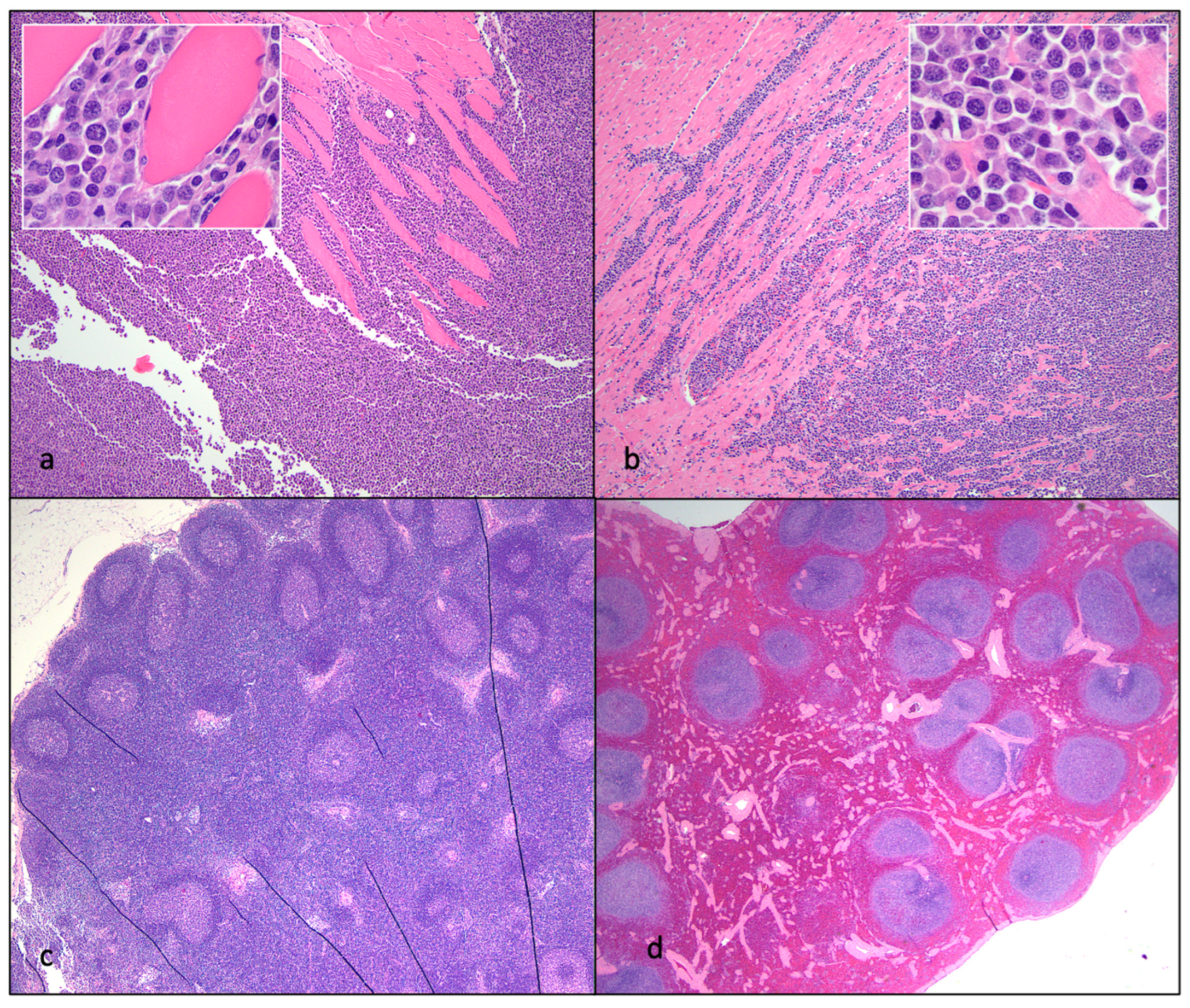

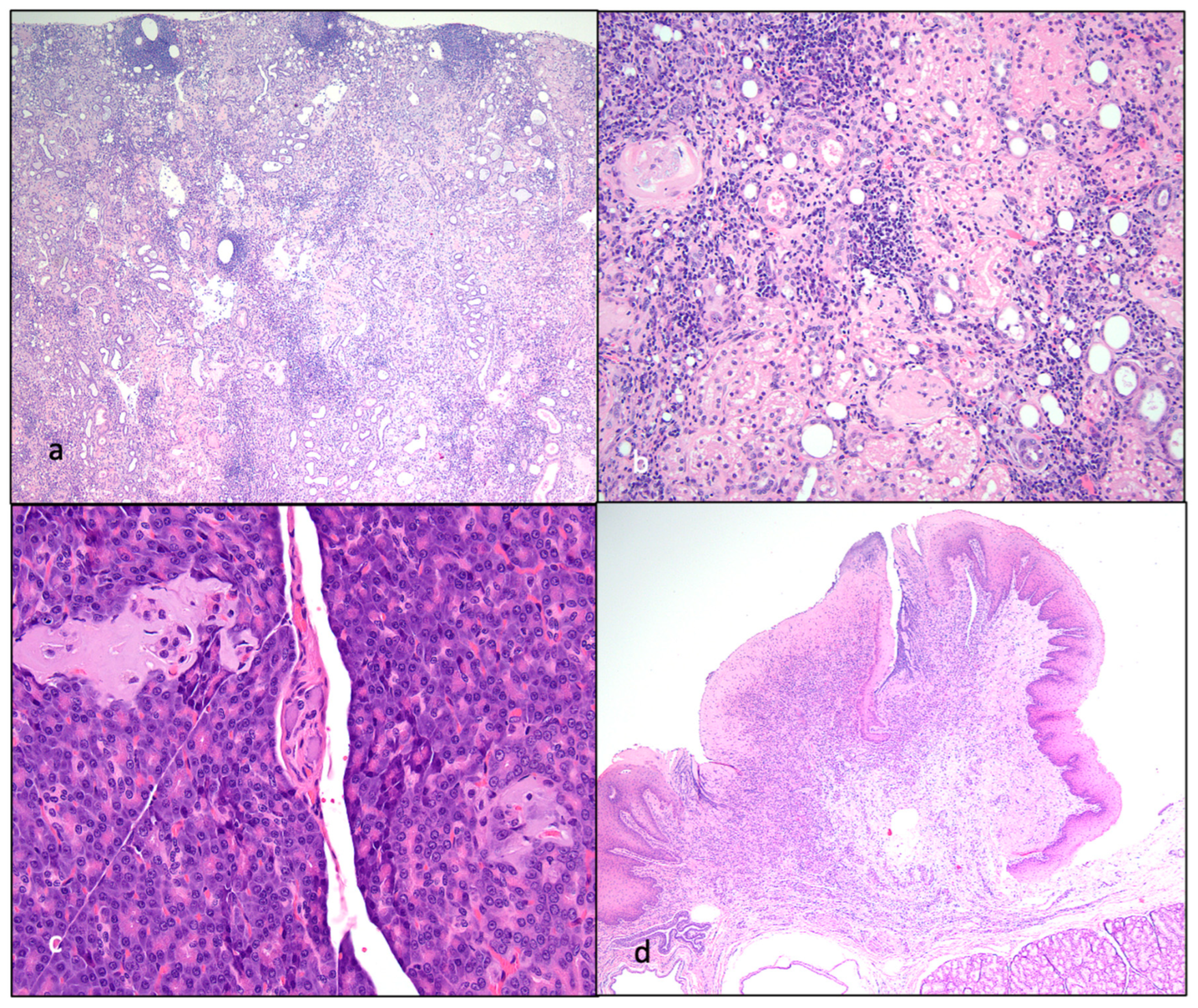

Figure 12.

Histological features of lymphoma and lymphoid hyperplasia in FIV-infected cats. (a and b) Disruption of the intercostal (a) and cardiac (b) musculature by sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes is evident in tissues from progressor 184 (lymphoma). Insets- Neoplastic lymphoblasts (blue cells) infiltrate and isolate skeletal myocytes and cardiac myocytes (pink cells). (c) The mesenteric lymph node has numerous well-organized cortical follicles with a germinal center and peripheral mantle zone (lymphoid hyperplasia, non-progressor cat 187). (d) The splenic white pulp has numerous hyperplastic lymphoid follicles (lymphoid hyperplasia, progressor 186).

Figure 12.

Histological features of lymphoma and lymphoid hyperplasia in FIV-infected cats. (a and b) Disruption of the intercostal (a) and cardiac (b) musculature by sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes is evident in tissues from progressor 184 (lymphoma). Insets- Neoplastic lymphoblasts (blue cells) infiltrate and isolate skeletal myocytes and cardiac myocytes (pink cells). (c) The mesenteric lymph node has numerous well-organized cortical follicles with a germinal center and peripheral mantle zone (lymphoid hyperplasia, non-progressor cat 187). (d) The splenic white pulp has numerous hyperplastic lymphoid follicles (lymphoid hyperplasia, progressor 186).

Figure 13.

Histological features of nephritis, islet amyloidosis and ulcerative stomatitis in FIV-infected cats. (a) The renal cortex has a loss of tubules and numerous interstitial aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells (interstitial nephritis, progressor cat 186). (b) The renal interstitium is multifocally infiltrated by lymphocytes and scattered glomeruli are sclerotic (interstitial nephritis, non-progressor cat 187). (c) Endocrine cells within the pancreatic Islets of Langerhans are largely replaced by amphophilic amyloid material (islet amyloidosis, non-progressor cat 187). (d) The oral mucosa adjacent to the tonsil and diffuse salivary gland tissue is necrotic and ulcerated, the lamina propria is infiltrated by large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells (peritonsillar ulcerative stomatitis, progressor cat 186).

Figure 13.

Histological features of nephritis, islet amyloidosis and ulcerative stomatitis in FIV-infected cats. (a) The renal cortex has a loss of tubules and numerous interstitial aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells (interstitial nephritis, progressor cat 186). (b) The renal interstitium is multifocally infiltrated by lymphocytes and scattered glomeruli are sclerotic (interstitial nephritis, non-progressor cat 187). (c) Endocrine cells within the pancreatic Islets of Langerhans are largely replaced by amphophilic amyloid material (islet amyloidosis, non-progressor cat 187). (d) The oral mucosa adjacent to the tonsil and diffuse salivary gland tissue is necrotic and ulcerated, the lamina propria is infiltrated by large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells (peritonsillar ulcerative stomatitis, progressor cat 186).

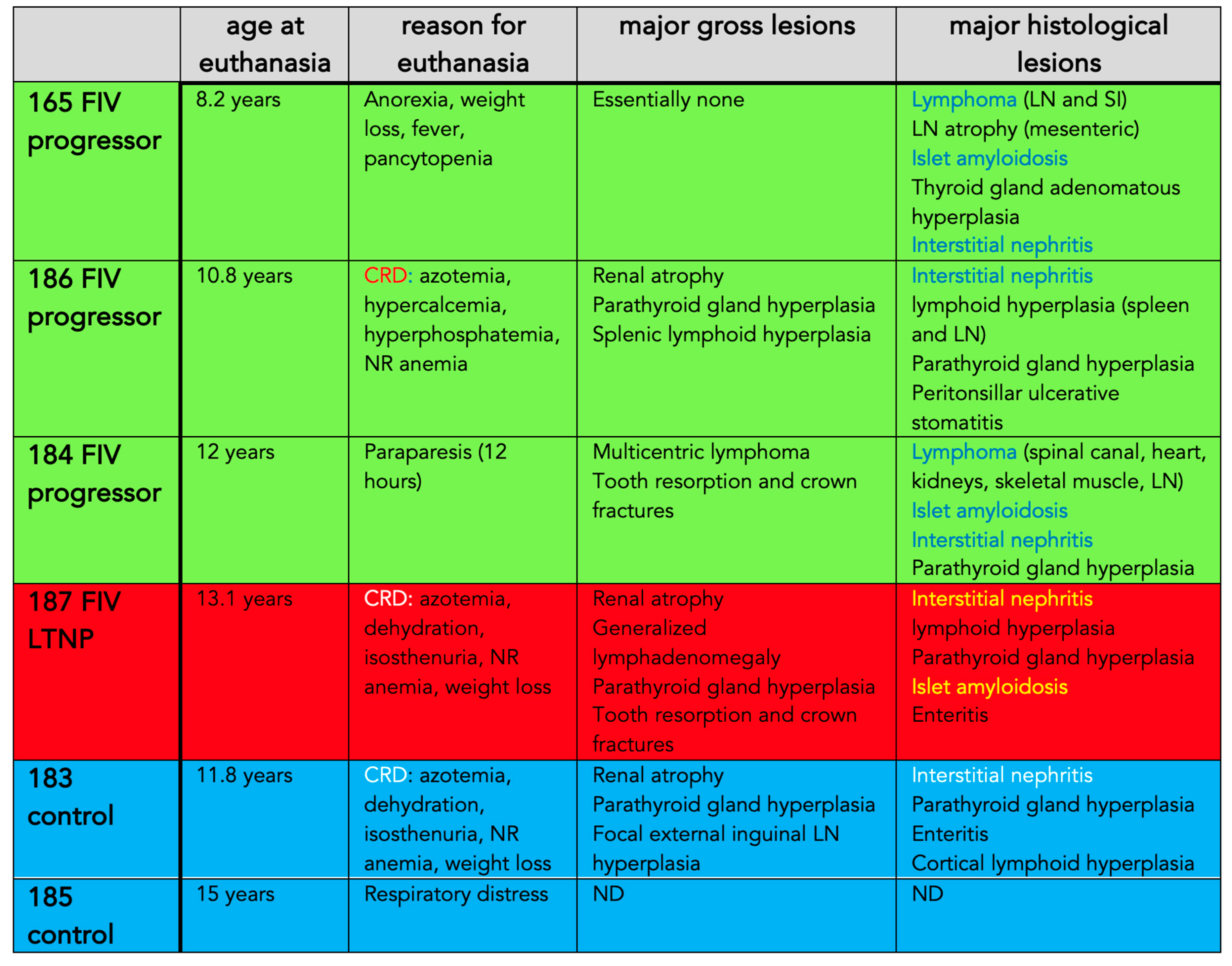

Table 1.

Terminal clinical abnormalities and pathologic findings. CRD- chronic renal disease, LN- lymph node, SI- small intestine, ND- not determined.

Table 1.

Terminal clinical abnormalities and pathologic findings. CRD- chronic renal disease, LN- lymph node, SI- small intestine, ND- not determined.