1. Introduction

Feline Panleukopenia (FPL), historically termed feline distemper [

1,

2], or feline infectious enteritis [

3,

4] represents one of the earliest documented parvovirus infections in Felids[

5]. FPL exhibits near-ubiquitous prevalence across global feline populations, with phylogenetic evidence tracing its origins to the early 20th century [

6]. It’s hallmark clinical triad-hemorrhagic enteritis, cerebellar hypoplasia in neonates [

7], and panleukopenia-drives morbidity rate exceeding 90% in naïve populations, while mortality escalates to 50–90% in kittens due to secondary sepsis [

8]. Vaccine administration, also known as vaccination, remains the most reliable approach for preventing and controlling this debilitating condition[

9,

10].

Despite the historic success of inactivated vaccines or attenuated live vaccines on FPL in the America or European Union[

10,

11], just only a killed combination vaccine (Fel-O-Vax

® PCT) for cats was introduced into China so far. Surveillance studies (2018–2024) document a 27% rise in FPLV breakthrough infections among vaccinated cohorts [

12,

13], reveal alarming gaps in cross-protection between commercial vaccines. and the FPLV newly epidemic strain (carrying Ala91Ser, Ile101Thr substitution in VP2 protein) that currently widely circled cats in China [

14,

15]. This immunological dissonance underscores the urgent need for next-generation platforms capable of eliciting broader, strain-agnostic immunity.

The advent of virus-like particles (VLPs) has redefined vaccinology by merging structural virology with precision immunology. Unlike traditional vaccines, VLPs harness the evolutionary refinement of viral architecture while eliminating replicative risks, positioning them as a paradigm-shifting technology for both prophylactic and therapeutic applications [

16]. Virus-like particles (VLPs) are self-assembling one or more viral structural proteins, and differ from other subunit vaccines in they have strong immunogenicity because they present repetitive antigenic epitopes to the immune system [

17,

18].

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV), the primary etiological agent of FPL, is a single-stranded, negative-sense DNA virus [

19]. The viral protein (VP2) serves as the major immunogen of FPLV, response for eliciting the production of neutralizing antibodies in the host. It also critical for receptor binding, host range determination, and virulence [

14]. Additionally, VP2 represent the key target antigen in the development of novel FPLV vaccine [

20].

Several platforms have been used for VLP production. The choice of the preferred platform provides flexibility in the manufacturing conditions required for the scaled-up production of VLP [

16]. The baculovirus expression system (BES) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for producing structurally authentic VLPs, owning to its unique capacity to preserve post-translational modifications (PTMs) (glycosylation) and scale cost-effectively [

16,

21].

This study pioneers the use of BES to generate VLPs by expression of the VP2 proteins of a FPLV Chinese epidemic strain (Ala91Ser) of feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV-VP2-VLPs) and an investigation to characterize and assess the immunogenicity of these FPLV-VLPs was conducted. The results gained from this research could offer fundamental data for the development of innovative FPLV vaccines. These findings position FPLV-VLPs as a cornerstone for pan-parvovirus vaccine development, with translational potential extending to canine parvovirus (CPV) and porcine parvovirus (PPV).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virus and Cells

Feline panleukopenia virus (named FPLV-CC19-02), used in this study, was previously isolated from a severe diarrhea cat in Changchun city, Jilin Provine, which harboring a Ala91Ser substitution in VP2 protein and widely circled in cats in China since 2017 [

14,

15]. The complete genome sequence of FPLV-CC19-02 are publicly available (Gene Bank number: OR921195.1).

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) were maintained in suspension in Sf9-900 II SFM medium (Gibco, MD, USA) at 28 °C. Cellfectin™ II transfection reagent was purchased from Gibco (Beijing, China). The BacPAK Baculovirus Rapid Titer Kit was purchased from Takara (Dalian, China). Anti-CPV-2c-VP2 monoclonal antibody (clone 5B18) was also prepared in our laboratory.

2.2. Construction of Recombinant Baculoviruses

The sequence encoding the VP2 protein of a FPLV-CC19-02 was optimized for Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (Sf9) and synthesized by Nanjing Zoonbio Biotech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) based on specific primers: VP2-F:5’-GATTATTCAACCGTCCCACC

ATCGGGCGCGGATCCGCCACCATGCTGCTGGTGAACCAGAGCCACCAG-3’, and VP2-R: 5’-GCTGATTATGATCCTCTAGTACTTCTCGACAAGCTTTTAGGCGTAGTCA

GGCACGTCGTAGGGGTAGTA-3’.

The synthesized target gene was identified by PCR and subcloned into the donor plasmid pFastBac by homologous recombination. After confirmed by double restriction enzyme digestion (BamH I and Hind III) and PCR identification, the recombinant plasmids (pFastBac-FPLV-VP2) were transformed into E. coli DH10Bac competent cells to produce the rBacmid-FPLV-VP2. Blue-white screening was used to detect colonies containing recombinant bacmid DNA, which were further identified by PCR amplification using the M13 primers. The recombinant bacmids were isolated and purified by using Endo Free Plasmid Maxi kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the protocol of manufacture.

2.3. Acquisition of Recombinant Baculovirus

Sf9 cells suspension (5×106 cells/mL) were seeded into 6-well plates (2 mL/well) and culture at 27 °C for 12 h. 4 µg bacmid-FPLV-VP2 and 8 µL Cellfectin™ II transfection reagent (Gibco, MD, USA) were added to 100 µL of Grace’s medium (no serum, no antibiotic), respectively, and incubated it for 30 min at 37°C incubators. Next, the two reagents were gently mixed and incubated for another 30 min at room temperature before dispensing onto Sf9 cells. The mixture (approximately 210 µL) was added to the cell culture plate and incubated at 28°C for 4 h before replacing with 2 mL Sf-900 II SFM medium. After two serially passaged, virus-infected Sf9 cells shows typically phenotypic symptom of viral infection, like increase in cell diameter, and detachment from the plate.

2.4. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA) analysis of Recombinant Baculoviruses

A suspension of Sf9 cells (2×106 cells/mL) were seeded in 6-well plates and infected with the four-generation recombinant baculoviruses. Uninfected Sf9 cells was served as a negative control. After two days of infection, the culture medium was discarded and Sf9 cells were washed three times with PBST (5 minutes/time). Then, the Sf9 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 minutes at room temperature. After three times washes with PBST, 0.5% Triton X-100 was added to permeabilize the cells. Discarded the solution and washed the cells another three times. Subsequently, the cells were blocked with 5% skim milk for 60 min at 37°C, and followed by three times washes. After that, the cells were incubated with a homemade mouse anti-CPV-2c monoclonal antibody (clone 5B18) in a dilution of 1:200 for 1h at 37 °C. Washed the cells three times, and incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:2, 000) for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, the cells were washed three times and observed under a fluorescence microscope ((Leica AF 6000, Wetzlar, Germany). x

2.5. Generation and Purification of FPLV-VP2-VLPs

To generate the FPLV-VP2-VLPs, 5×108 of Sf9 cells (100 mL) were infected with four-generation recombinant baculoviruses at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, and incubated at 28 °C for 4-5 days. After that, the Sf9 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8 000 ×g for 20 minutes (Rotator type F-34-6-38, Eppendorf, Germany). The collected cells were further lysed with 25 mM NaHCO3 at 4 °C for 2 hours, and the supernatant (FPLV-VP2-VLPs) was collected by centrifugation at 8, 000 ×g again. The expression of FPLV-VP2 was detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were employed to analyze the expression of the VP2 protein through utilizing a homemade anti-CPV-2c monoclonal antibody (clone 5B18) as the primary antibody.

2.6. Antigenicity Analysis of FPLV-VP2-VLPs

The antigenicity of the FPLV-VP2-VLPs protein (designated as P4) was evaluated using rapid test immunochromatographic strips developed by SHANGHAI QUICKING Biotech CO., Ltd. for feline panleukopenia virus antigens.

2.7. Hemagglutinin Activity Analysis of FPLV-VP2-VLPs

The hemagglutinin activity of the FPLV-VP2-VLPs was assessed through the hemagglutinin assay (HA) [

22] on a 96-well ‘V’ bottom microtiter plate. Briefly, 25 µL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.4) was dispensed in well A and thereafter across the rows (1-4) and columns (A-G) using 10-100 µL variable volume multichannel micro-pipette. Then, 25 of FPLV-VP2-VLPs were put into first well of microtiter plate, set one biological replicates and control group. Then, they were serially diluted from1:2

1 to 1:2

20 across through the first column. Next, 25 µL of PBS was dispensed all working wells and thereafter, 50 µL of 1% porcine red blood cells (RBCs) suspension was placed. The plate was agitated at 150 rpm for 2 min to ensure proper mixing of reactants. After that, the plate was put at 4 °C for 45 minutes and formation of serrated edged mat or bottom were recorded as negative and positive results, respectively. The titer was calculated as reciprocal of the last well with agglutination.

2.8. Transmission Electron Microscopy

The morphology of the FPLV-VP2-VLPs protein (P4) was observed under transmission electron microscopy (TEM) after negative staining as previously described by Gao et.al., [

23]. Briefly, 1 mL of FPLV-VP2-VLPs protein and 20 µL of CaHPO4 solution were placed into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube, mixed well, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Then, the tube was centrifuged at 15,000 r/min for 15 minutes, and the sediment was dissolved with 15 µL of EDTA saturated solution to create a droplet. The droplet was dropped onto a copper grid, allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 minutes, and stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid staining solution (pH 6.8) for 1 minute. The excess staining solution was removed with filter paper, and the virus morphology was observed on a JEOL 2010 transmission electron microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV.

2.9. Animal Immunization and Challenge

Fifteen seronegative cats, British shorthair breed and 3 to 4 months of age, were randomly assigned to five groups. Group I: VLPs vaccine (Seppic adjuvant, 9:1). Group II: killed FPLV vaccine (Seppic adjuvant, 9:1). Group III: Fel-O-Vax® PCT, Group IV: control, Minimum essential medium (MEM). All cats were initially inoculated with a single dose of 1.0 mL of their respective sample. Blood samples were taken from each cat at various time points post-vaccination, including 0-, 7-, 14-, 21-, 24-, 28-, 35-, 42-, and 50-days. Serum antibody titers against FPLV were then determined using a hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI).

Three weeks after vaccination, all cats were orally challenged with 5 mL of FPLV-CC19-02 strain cell culture (HA=210, TCID50=106.5/mL). Subsequently, a continuous observation and record of the cats’ performances, including their mental state, food and water intake, excrement shape, and rectal temperature, were conducted for 10 days post-challenge (dpc) to assess the immune efficacy of the vaccines. This monitoring helped evaluate the vaccines’ ability to provide protection and generate an effective immune response in the cats.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the collected data was performed using GraphPad Prism Software version 9.5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare the data among three or more groups.

3. Results

3.1. Construction and Identification of rBacmid-VP2

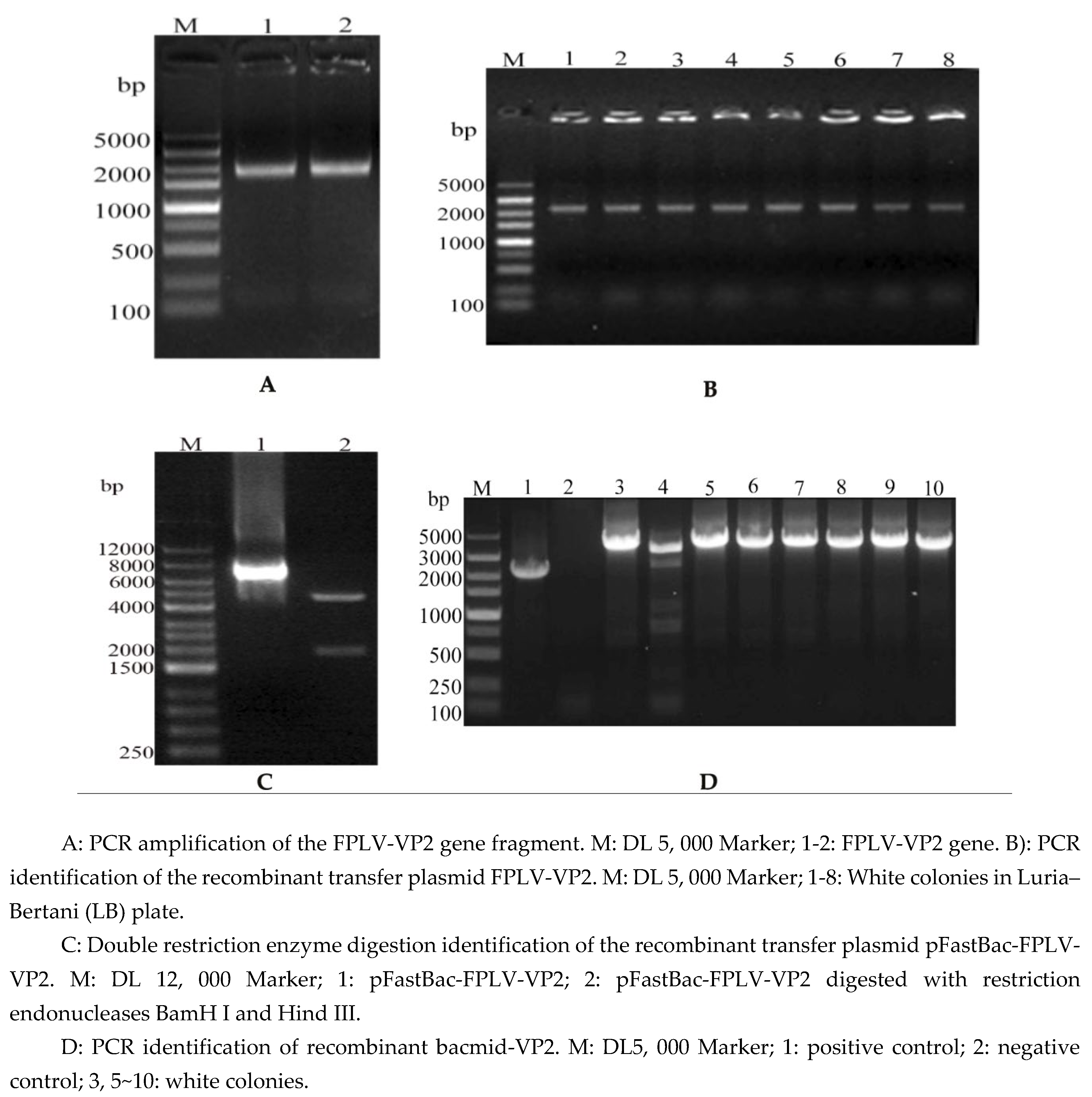

A gene fragment of approximately 2,000 base pairs (bp) in size was obtained by overlapping extension PCR amplification (

Figure 1a, lanes 1 and 2). Subsequently, the VP2 gene was subcloned into the

pFastBac-I vector via homologous recombination and identified through PCR (

Figure 1B, about 2200 bp, lane 1-8) and double enzyme digestion (

Figure 1C, lane 2, 1, 926 bp and 4, 671 bp), respectively. Ultimately, the

pFastBac-VP2 was transferred into

E. coli DH10Bac competent cells to generate rBacmid-VP2. After successful amplification of the target band, approximately 4,100 bp (

Figure 1D, lanes 3, 5-10), suggested the successful construction of rBacmid-VP2.

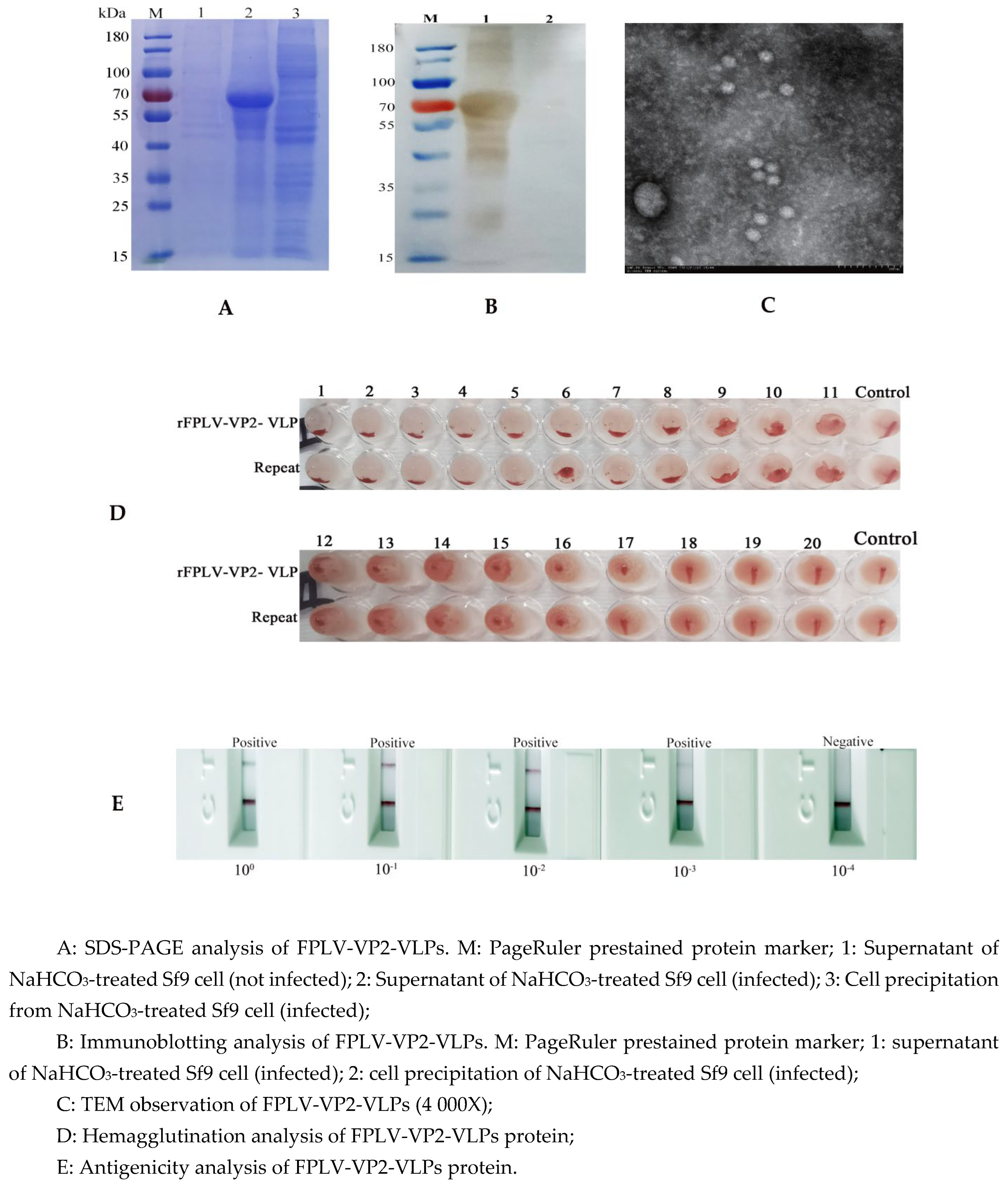

3.2. Analysis of FPLV-VP2-VLPs

According to SDS-PAGE analysis, the FPLV-VP2-VLPs protein (approximately 70 kDa) was predominantly present in the supernatant of NaHCO

3-treated infected Sf9 cells (

Figure 2A, lane 2). Furthermore, immunoblotting analysis revealed that the expression of FPLV-VP2-VLPs was intracellular (

Figure 2B, lane 1, arrows).

Under Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), numerous circular and spherical virus-like structures with a diameter of approximately 20-30 nm, resembling the native FPLV virus, were observed in the supernatant of NaHCO

3-treated infected Sf9 cells (

Figure 2C).

When FPLV-VP2-VLPs were seriously diluted (10

0 to 10

-3), it could still be detected by the FPLV antigen rapid test immunochromatographic strips, indicating its high antigenicity (

Figure 2E). Additionally, the hemagglutination (HA) titer of FPLV-VP2-VLPs (P4) reached a high level of 1:2

14~1:2

16 (

Figure 2D).

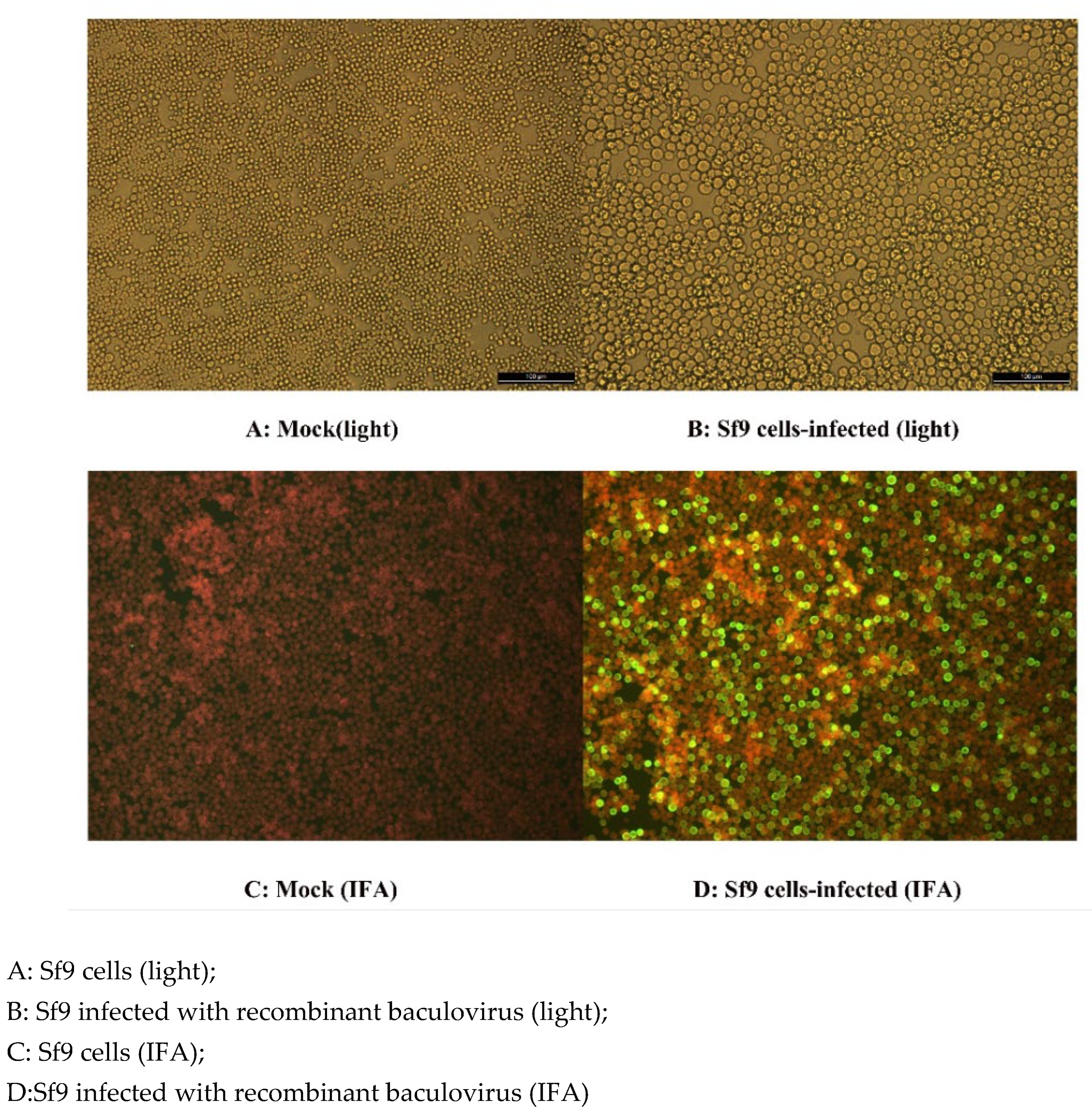

3.3. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay

Infected Sf9 with the recombinant baculovirus FPLV-VP2-VLP showed increase in diameter and exhibited a high-intensity green fluorescence (

Figure 3B,D), whereas the control group cells demonstrated no cytopathic effect (CPE) or no visible fluorescence (

Figure 3A,C). This observation clearly indicates that the Sf9 cells infected with the recombinant baculovirus correctly expressed the FPLV-VP2 protein.

3.4. Change in Hemagglutination Inhibition (HI) Antibody after vaccination

The hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer of all cats following vaccination and challenge is illustrated in

Figure 4. 7 days post vaccination (dpv), two cats in group II (FPLV inactivated vaccine) exhibited detectable hemagglutination inhibition antibodies (red line/scatter). At 14 dpv, all cats in groups I (green line/scatter) and II (red line/scatter) showed elevated levels of HI antibodies. By 21 dpv, cats in all groups, except the control group (black line/scatter), had elevated levels of HI antibodies. Following the challenge, the titer of HI antibodies continued to increase in all cats, reaching a new peak value unless they succumbed to the challenge.

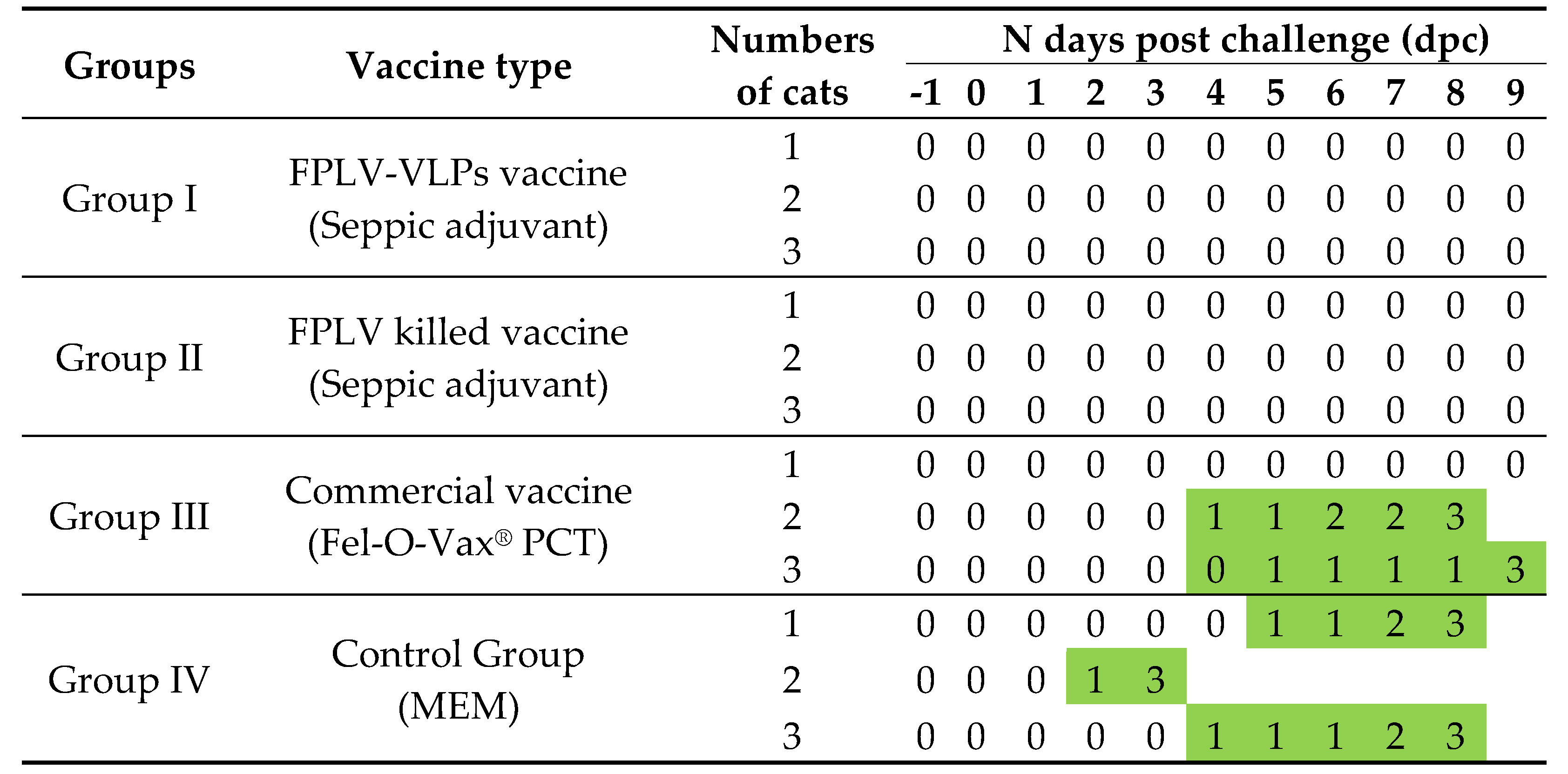

3.5. Clinical characteristic of Cats after Challenge

The results of challenge-protection statistics are presented in

Table 1. Both the VLP vaccine and FPLV killed vaccine, prepared with Seppic adjuvant, offered 100% protection to the cats. However, the commercial vaccine (Fel-O-Vax

® PCT) provided only partial protection to cats (33%),. All cats in the control group succumbed to the challenge either at 3 or 8 dpc.

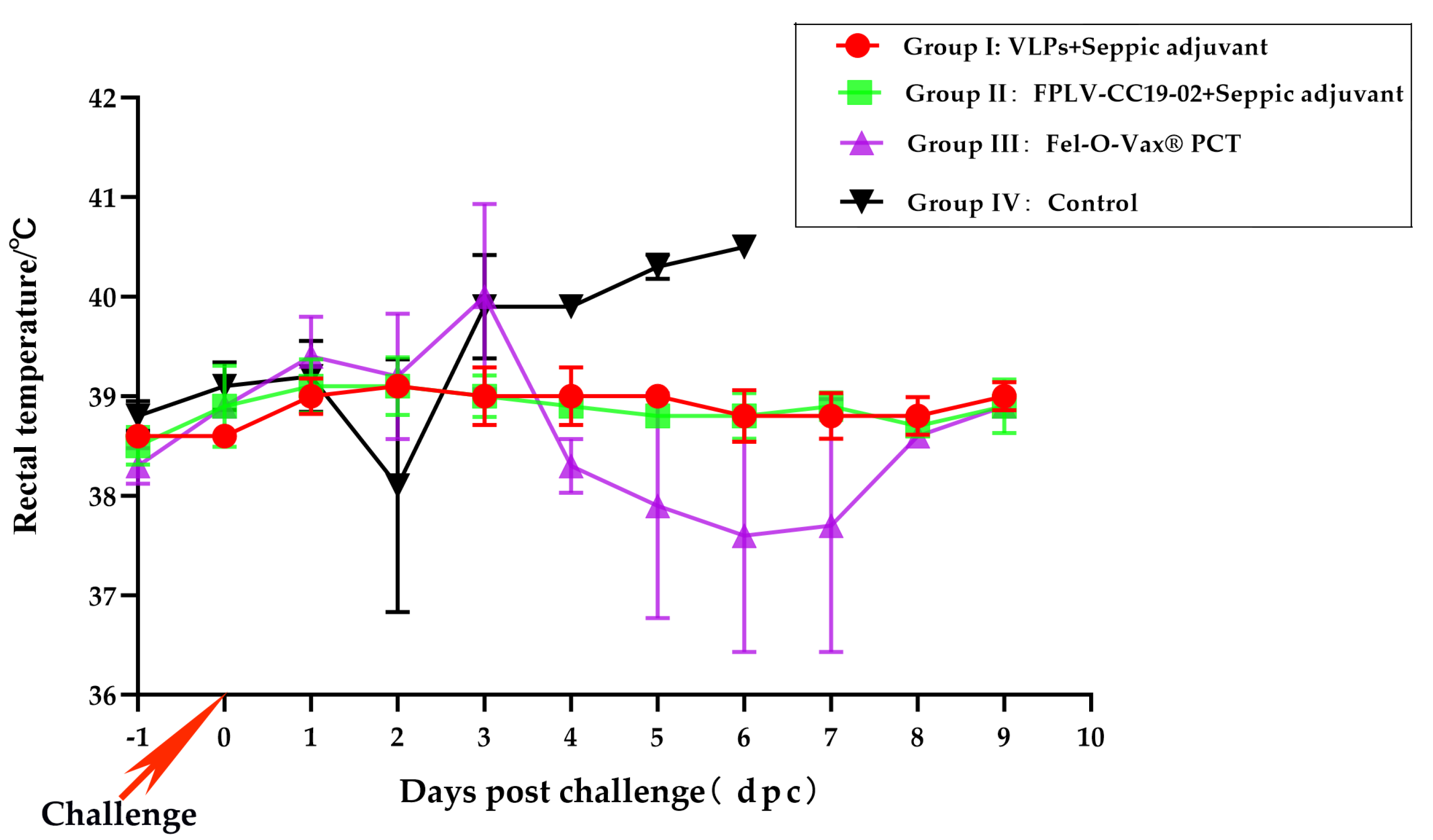

The changes in body temperature for cats in all groups after the challenge are depicted in

Figure 5. Approximately 67% of the cats vaccinated with the commercial vaccine (Fel-O-Vax

® PCT) exhibited hyperpyrexia (>40°C in average),(Group III, pink line/scatter). The temperature of cats in groups I (red line/scatter) and II (green line/scatter) float within a normal range. Interestingly, the body temperature of cats in the control group initially decreased before increasing to higher temperatures (>40°C). Some cats’ body temperatures dropped to lower levels before they passed away (pink line/scatter).

Furthermore, after the virus challenge, cats in group III and IV displayed clinical manifestations of feline panleukopenia (FPL). These signs included fever, depression or lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, unconsciousness, and even fatal outcomes (

Table 2). In contrast, the cats in groups I and II remained asymptomatic.

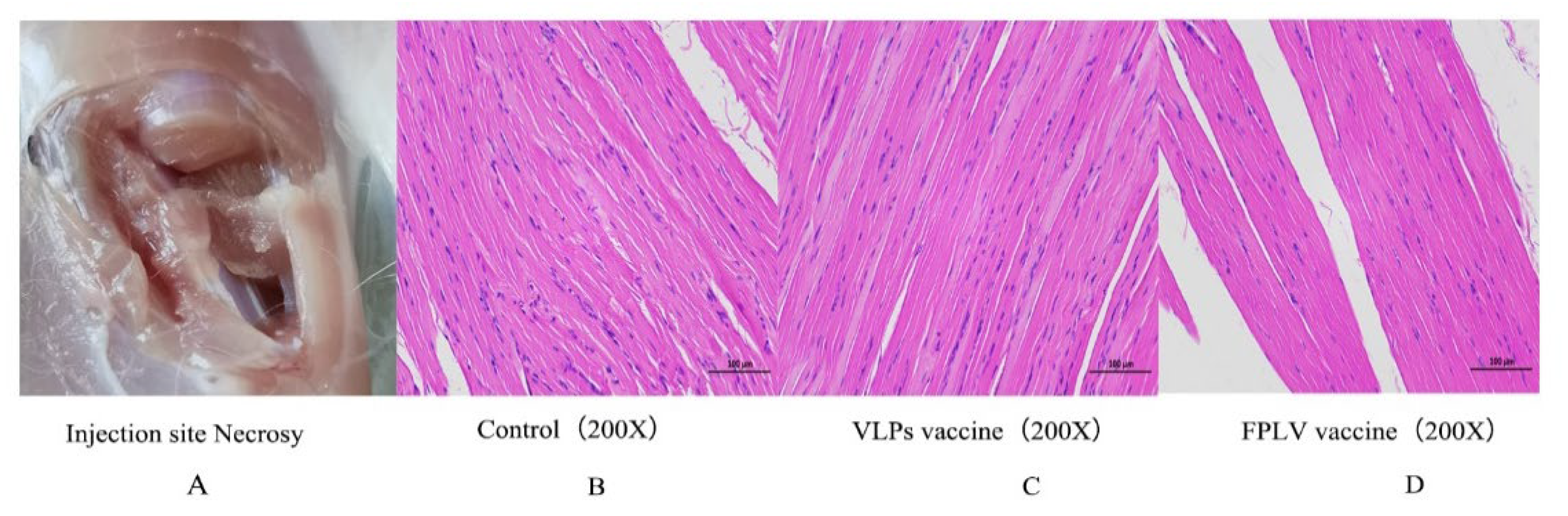

3.6. Safety Evaluation of Vaccines

After necropsy, there were no sarcomas detected at the injection site (

Figure 6A). In both the control group (

Figure 6B) and the vaccine group (

Figure 6C,D), the muscle cells were neatly and tightly arranged, with distinct cell boundaries and consistent orientation. The horizontal lines of muscle cells were clearly visible, alternating between light and dark, and there were no abnormalities in the stroma. Furthermore, there was no obvious infiltration of inflammatory cells observed in any of the tissue samples.

4. Discussion

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are multimeric self-assembling structural composed of virus capsid protein (eg. VP2) devoid of viral genetic materials, which structurally resemble their parental viruses[

17]. Due to the unique properties of parvovirus structural proteins, such as their ability to spontaneously self-assemble into VLPs, these particles are recognized as ideal templates for novel vaccine development, particularly in veterinary application[

23,

24,

25,

26].

In this study, we successfully expressed the VP2 protein of FPLV in an insect cell baculovirus expression system (

Figure 2A). The expressed VP2 protein correctly folded into VLPs (

Figure 2C), which were identified using a monoclonal antibody specific to the expressed VP2 of canine parvovirus 2c (

Figure 2B and

Figure 3D) and confirmed via FPLV antigen rapid test immunochromatographic strips (

Figure 2E). These results demonstrated high antigenicity of the expressed protein. Furthermore, the VLPs exhibited enhanced hemagglutination activity, achieving titers of 1:2

14 to 1:2

16 (

Figure 2D), surpassing the HA titer of the epidemic strain of FPLV, which ranged from 1:2

8 to 1:2

10.

FPLV-VP2-VLPs demonstrate robust immunogenicity, eliciting a significant humoral immune response in vaccinated cats. At 14 days post vaccination(dpv) with the Seppic-adjuvanted VLPs vaccine, cats exhibited a high hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer of 1:2

12, consistent with prior research [

25]. By 21 dpv, all vaccinated cats achieved HI titers exceeding 2

10, indicating robust and sustained immunity. Notably, the whole virus inactivated vaccine also induced a positive immune, with some cats showing detectable HI antibodies as early as 7 dpv. These findings suggest that VLPs-based vaccines are comparable in efficacy to traditional vaccines. In contrast, cats administered the commercial Fel-O-Vax

® PCT vaccine demonstrated delayed antibody detection, with HI titers remaining below 2

8 until 21 dpv(

Figure 4, blue line/scatter).

The level of antibodies generated by vaccines is a crucial determinant of protective efficacy against viral challenges. In this study, both VLPs-based vaccine (Seppic adjuvant) and whole virus inactivated vaccine elicited significant protection against virulent FPLV challenge, as evidenced by 100% survival rates in vaccinated cohorts. In contrast, the commercial vaccine demonstrated only 33% protection, potentially attributable to suboptimal immunization protocols (single-dose administration). These findings align with broader vaccine research indicating that antibody titers≥1:64 are generally required for feline panleukopenia protection, while suboptimal dosing strategies may compromise immune response.

The safety of companion animal vaccinations has been a topic of significant debate over the past decade, particularly regarding the association between vaccine and sarcoma development in cats [

26,

27] . To evaluate the safety profile of our FPLV-VP2-VLPs vaccine, we performed histopathological analysis of muscle tissue samples collected from the inoculation sites of vaccinated cats. Notably, no sarcomas or pathological alterations were observed in any animals (

Figure 6), confirming the absence of vaccine-associated sarcoma formation. Additionally, all vaccinated cats maintained clinically normal body temperature throughout the study period. These finding collectively demonstrate that the FPLV-VP2-VLPs vaccine exhibits an exceptional safety profile, with no adverse histopathological findings or measurable febrile responses.

5. Conclusions

In summary, a novel pet vaccine against FPL with a higher effectiveness and safety profile was developed in this study. In subsequent applications, the FPLV-VLPs vaccine can be used as a single vaccine or in combination with other vaccines to vaccinate cats for phylaxis against FPL. This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization E.F. and G.L., methodology, and investigation, E.F., data curation, W.L., C.W., and R. Y., writing—original draft preparation, E.F.; writing—review and editing, X.B., and. Y.C.; funding acquisition, E.F. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2023YFD1800700.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Jilin Province Laboratory Animals Regulations. The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (protocol code: ISAPSAEC-2022-60C, and date of approval at march 03.22, 2022, every possible effort was made to minimize animal suffering throughout the experiment.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable, for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| dpc |

Days Post Challenge |

| dpv |

Days Post Vaccination |

| VLPs |

Virus-like Particles |

References

- Gendreau, L.A. Sulphanilamide in Feline Distemper. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci 1941, 5, 56–57.

- Hindle, E.; Findlay, G.M. Studies on Feline Distemper. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics 1932, 45, 11–26.

- Leasure EE, L.H. Feline Infectious Enteritis. North Am Vet 1934, 15, 30–34.

- O’Reilly, K.J. Study of an Attenuated Strain of Feline Infectious Enteritis (Panleucopaenia) Virus. I. Spread of Vaccine Virus from Cats Affected with Feline Respiratory Disease. J Hyg (Lond) 1971, 69, 627–635.

- Fairweather, J. Epidemic among Cats in Delhi, Resembling Cholera. The Lancet 1876, 108, 115–117.

- Verge J, C.N. La Gastroenterite Infectieuse Des Chats Est Elle Due a Uvirus Filtrable? In Proceedings of the Comptes rendus des seances de la Societe de biologie (Paris); 1928; Vol. 99, pp. 312–314.

- Csiza, C.K.; De Lahunta, A.; Scott, F.W.; Gillespie, J.H. Spontaneous Feline Ataxia. Cornell Vet 1972, 62, 300–322.

- Kruse, B.D.; Unterer, S.; Horlacher, K.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Prognostic Factors in Cats with Feline Panleukopenia. Journal of veterinary internal medicine 2010, 24, 1271–1276.

- Jacobson, L.S.; Janke, K.J.; Ha, K.; Giacinti, J.A.; Weese, J.S. Feline Panleukopenia Virus DNA Shedding Following Modified Live Virus Vaccination in a Shelter Setting. The Veterinary Journal 2022, 279, 105783.

- Stone, A.E.; Brummet, G.O.; Carozza, E.M.; Kass, P.H.; Petersen, E.P.; Sykes, J.; Westman, M.E. 2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2020, 22, 813–830.

- Squires, R.A.; Crawford, C.; Marcondes, M.; Whitley, N. 2024 Guidelines for the Vaccination of Dogs and Cats - Compiled by the Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA). J Small Anim Pract 2024, 65, 277–316.

- Cao, L.; Chen, Q.; Ye, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Jin, J.; Cao, S.; et al. Epidemiological Survey of Feline Viral Infectious Diseases in China from 2018 to 2020. Animal Research and One Health 2023, 1, 233–241.

- Pan, S.; Jiao, R.; Xu, X.; Ji, J.; Guo, G.; Yao, L.; Kan, Y.; Xie, Q.; Bi, Y. Molecular Characterization and Genetic Diversity of Parvoviruses Prevalent in Cats in Central and Eastern China from 2018 to 2022. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1218810.

- Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Tian, L.; Zhao, J.; Peng, Q.; Bi, Z. Prevalence and Molecular Evolution of Parvovirus in Cats in Eastern Shandong, China, between 2021 and 2022. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2024, 2024, 5514806.

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, H.; Zhou, N.; Tang, C. Circulation of Heterogeneous Carnivore Protoparvovirus 1 in Diarrheal Cats and Prevalence of an A91S Feline Panleukopenia Virus Variant in China. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, e2913–e2925.

- Gupta, R.; Arora, K.; Roy, S.S.; Joseph, A.; Rastogi, R.; Arora, N.M.; Kundu, P.K. Platforms, Advances, and Technical Challenges in Virus-like Particles-Based Vaccines. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1123805.

- Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Ma, X.; Sun, X.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y. Virus-like Particles as Antiviral Vaccine: Mechanism, Design, and Application. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 2023, 28, 1–16.

- Chackerian, B. Virus-like Particles- Flexible Platforms for Vaccine Development. 2007.

- Barrs, V.R. Feline Panleukopenia: A Re-Emergent Disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2019, 49, 651–670.

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Liang, R.; Yang, M.; Yan, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, M.; Shen, Z.; et al. Novel Mutation N588 Residue in the NS1 Protein of Feline Parvovirus Greatly Augments Viral Replication. J Virol 2024, 98, e0009324.

- Chambers, A.C.; Aksular, M.; Graves, L.P.; Irons, S.L.; Possee, R.D.; King, L.A. Overview of the Baculovirus Expression System. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 2018, 91, 5.4.1-5.4.6.

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xin, T.; Yuan, W.; Guo, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Jia, H. Genetic Characterization and Evolutionary Analysis of Canine Parvovirus in Tangshan, China. Arch Virol 2022, 167, 2263–2269.

- Gao, T.; Gao, C.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Zeng, W.; Bergmann, S.M.; Wang, Q. Recombinant Baculovirus-Produced Grass Carp Reovirus Virus-Like Particles as Vaccine Candidate That Provides Protective Immunity against GCRV Genotype II Infection in Grass Carp. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9.

- Jin, H.; Xia, X.; Liu, B.; Fu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Xia, Z. High-Yield Production of Canine Parvovirus Virus-like Particles in a Baculovirus Expression System. Arch Virol 2016, 161, 705–710.

- Jiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Jin, H.; Liu, D.; Zhao, J.; Feng, N.; Zhang, C.; Shi, J. Construction and Immunogenicity of Virus-Like Particles of Feline Parvovirus from the Tiger. Viruses 2020, 12.

- Pereira, S.T.; Gamba, C.O.; Horta, R.S.; Cunha, R.M. de C.; Lavalle, G.E.; Cassali, G.D.; Araújo, R.B. Histomorphological and Immunophenotypic Characterization of Feline Injection Site-Associated Sarcoma. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae 2021, 49.

- Brearley, M.J. Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma—an Emerging Problem. Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery 1999, 1, 5–6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).