1. Introduction

In the field of climate change adaptation, the future matters [

1,

2]. Mills-Novoa et al. [

3] show that - through participatory practices - certain futures that are deemed desired by those who rule, are linked to required actions in the current era by those who are to follow. For this, these attitudes, behaviours and actions are internalized and normalized as the best way to adapt to climate change. Future climate change projections, therefore, justify the way adaptation projects come into being. Muiderman et al. [

4] formulate this practice as a strong anticipatory governance paradigm, in which the use and power of future projections are central. In this context, the scientific adaptation community focusses on concepts like resilience, vulnerability, adaptive capacity and mitigation, with a recently added interest in green infrastructure or ‘nature based solutions’ that are all proposed as solutions to climate change impacts [

5]. In river research, many studies focus on future increases in floods and drought as a consequence of climate change [

6]. Generally, the simulated impacts of climate change describe an increase in floods and droughts that impact, amongst others, rivers.

Beyond climate projections, river futures are also shaped by ideas around the way rivers are managed. Duarte-Abadía [

7], for instance, describes how river futures in Spain and Colombia standardized water governance practices towards a specific idea of progress, namely capital growth. Moreover, Jaramillo and Carmona [

8] describe how dominant mining futures led to the reallocation of a Colombian river by presenting normalized, inescapable futures. Hommes et al. [

9] furthermore describe how large infrastructural river projects reflect specific ideas, morals and values on how rivers should be managed. As such, we follow the call by Jasanoff and Kim [

10] (p. 14) that “

more needs to be done to explain why societies opt for particular directions of choice and change over others and why those choices gain stability or not.”

While we deeply acknowledge the empirical existence and rapidly proliferating impacts of climate change and align ourselves with the urgent need to act, we challenge the ways in which dominant paradigms and expert claims monopolise the truth concerning policies and designs of river futures, side-lining and delegitimizing alternative river futures. Currently, very limited work is done to critically reflect on the power of river futures in the context of climate change adaptation. This brings forward the need to scrutinise and decipher the future-making processes in climate change adaptation, and to elucidate power structures that shape such future making processes. We argue that George Orwell’s famous quote “Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present, controls the past” [

11] (p. 87) can be extended to ‘Who controls the future, controls how we see and act in the present, and how we rediscover the past’.

To study future making processes and their influence on river management we take an interpretive and empirical approach in which we use a combination of concepts to make sense of empirical findings. We combine a conceptualization of sociotechnical imaginaries [

10] with that of hydrosocial territories [

12]. We adopt a Foucauldian understanding on the relationship between power, knowledge and truth taking shape in specific epistemic communities [

13,

14]. As a case study we focus on the European Meuse river, specifically on the Border-Meuse trajectory in the Netherlands. A large nature-based solution project is being implemented, legitimized by a variety of river futures. We first empirically ask what river futures and truth regimes are present in the case study? And secondly how the power of river futures is at work in truth regimes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical framework: River Imaginaries

To study the power of river futures in the context of climate change adaptation, we integrate the concepts of ‘sociotechnical imaginaries’ [

10] and ‘hydrosocial territories’ [

12] which we align with the concepts of ‘epistemic communities’ [

14,

15] and ‘truth regimes’ [

13]. We adopt an interpretative approach and use these concepts as lenses to make sense of empirical findings. Combining the four concepts, we define the concept of river imaginaries. The intention is not to develop a new conceptual approach, but rather to introduce the groundwork for a novel way to study the power of futures in river management.

River Futures: sociotechnical imaginaries and hydrosocial territories

The concept of sociotechnical imaginaries has been used to study how ideas on technology and their contribution to ‘progress’ , reinforce specific ideas on what progress is, could be, or should be. Davoudi and Machen [

16] for instance, studied how imaginaries materialise specific ideas on how to cope with climate change. For us, this materialisation is key; sociotechnical imaginaries are more than the imagination and exist beyond the mind [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Jasanoff and Kim [

10] (p19), in their definition of sociotechnical imaginaries, for instance emphasize that imaginaries are about

performed visions: “

Collectively held and performed visions of desirable futures (or of resistance against the undesirable), animated by shared understanding about social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology”.

Their definition also makes clear that imaginaries, in their collective nature, surpass the individual. With regards to ‘visions of desirable futures’, in our understanding of imaginaries, we extend beyond the desirable, as they also include assumptions about what is possible, probable, plausible, imaginable and unimaginable. Sociotechnical imaginaries provide an entire demarcated framework in which some elements fit well, and others do not. Moreover, futures are shaped through histories, past memories and actively constructed memories about the past, often influenced by idealized wishes to go back to the past by redefining and so prioritising pasts, presents and futures [

22]. Rulers in every society, moreover, have always legitimatised their power by actively devising ‘convenient histories’ that confirm their origin, position, knowledge and authority. These all codetermine river imaginaries: river imaginaries are about what a river is, what a river was, what a river ought to be and what a river cannot be.

The concept of hydrosocial territories helps us to think-through the intertwined sociomaterial nature of rivers. They are defined as: “

The contested imaginary and socio-environmental materialization of a spatially bound multi-scalar network in which humans, water flows, ecological relations, hydraulic infrastructure, financial means, legal-administrative arrangements and cultural institutions and practices are interactively defined, aligned and mobilized through epistemological belief systems, political hierarchies and naturalizing discourses.” [

12] (p. 2).

Rivers thus entail more than water. Understandings of riverine socio-natural life and socio-natural order include both human and non-human elements, particular ways of defining and entwining social and ecological communities. These understandings can be shared, but are also contested [

23,

24].

Power of river futures: epistemic communities and truth regimes

Both concepts, sociotechnical imaginaries and hydrosocial territories, state that these shared or contested understanding(s) of riverine socionature are mobilised through “

advances in science and technology” and through “

epistemological belief systems, political hierarchies and naturalizing discourses”. To operationalize the idea of collectively held (and contested) sociotechnical visions we employ the notion of epistemic communities, which Haas [

14] (p. 3) defines as: “

a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area”.

Obviously, such communities are not restricted to the professionals’ worlds but equally applies to groups who know rivers through different practices and ontologies. Members of an epistemic community share a trust or faith in the existence of a certain truth and the applicability of certain methods to come to specific knowledge or truth.

Truths become powerful through regimes that couple power to particular knowledge; while disempowering other forms and agents of knowledge. We understand power as omnipresent, “…

not because it would be in the privileged position of being able to group everything under its invincible unity, but because it is produced at every moment, at every point or, rather, in every relationship between different points” [

13] (p. 98). Power is thus relational, in networks, and often exists unintentionally. Foucault connects power to knowledge and truth by introducing discourses. For Foucault, a discourse establishes what is ‘true’ based on socially accepted modes of knowledge production. By separating legitimate forms of truth production and illegitimate forms, epistemic communities determine how and which ‘truth’ is reproduced, empowering or disempowering other forms of knowing.

We distinguish three dimensions of power and knowledge: visible, hidden and normalising power (adapted from [

25,

26]; see also [

27,

28]). Visible power is power that is demonstrated through formal rules, visible hierarchical valuation of expert epistemes, and recognition of established knowledge institutes. Hidden power refers to the manipulative and purposeful exclusion of alternative epistemes that aim for agenda setting. Normalising power links to the control of knowledge and truth production, to unconsciously shape legitimacy of those in power and demoralise others. In this normalising approach to power, those who produce the dominant, most trusted knowledge thus have the power to shape the legitimacy, probability, plausibility and imaginability of river futures.

In riverine struggles over knowledge and intervention projects, each of these three forms of power and knowledge gain respondence or are actively contested in their own way [

29]. Visible power may often be contested by presenting counter-facts that are presented as ‘more objective’ or ‘more grounded’ through the production of social and environmental information and data. Hidden power may be challenged by involving side-lined or marginalised actors (e.g. class, gender, ethnic groups that hold alternative river wisdoms) into the dominant river debate, challenging unequal (institutional) epistemic structures. Normalising power may be contested through scrutinising dominant knowledge production practices and steering towards their de-normalisation while building and advocating for other ontologies, thus challenging the way a shared understanding of social/natural life and order is produced.

In conclusion, we study the power of river futures through river imaginaries which we define as: Collectively performed and publicly envisioned reproductions of riverine socionatures, mobilized through truth claims of social life and social order.

2.2. Methods

We can gain insight in the content of imaginaries by comparing the holders of certain imaginaries [

10]. For instance, imaginaries can be found in the expression of values, symbols, norms, institutions, perceptions, emotions and social relationships. In the context of climate change, Davoudi & Machen [

16] describe how visual images, fiction, metaphors, stories and calculations shape imaginaries of climate change, and how different mediums (models and poems) materialise different climate imaginaries.

For this research we adopted a case study approach focusing on the Border Meuse case. Although this river trajectory forms the border between Belgium and the Netherlands, we study the Dutch context and its Border Meuse Project, because “projects may themselves reflect animating sociotechnical imaginaries” [

10] (p. 20). Within the formal water expert community the project is presented as a ‘best practices’ example of nature based solutions for climate change adaptation. This case study therefore lends itself well for studying how normative statements of ‘best practices’ are linked to futures, knowledge and truth.

Case study; truth regime of climate change adaptation in The Netherlands

The Dutch water sector has recognised a need for climate change adaptation and has formalised this in a national delta plan, developed by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water. The executive branch of the national water authority (Rijkswaterstaat) and the regional water authorities (Waterschappen) are responsible for its implementation. The national authority is responsible for the large water courses and rivers, while the regional authorities are responsible for the tributaries and smaller rivers and channels outside of urban areas. The ministry states that: “

Doing nothing [on climate change adaptation

] means that until 2050, between €77.5 and €173.6 billion of climate damage can occur. This is why climate change adaptation is needed” [

30].

The national policy that describes how to adapt to climate change through river management, argues that “

a forceful interplay of giving space to rivers and dike reinforcement” is the way to adapt to climate change [

31] (p. 6).

The national and regional authorities focus on determining water ‘risks’, ‘vulnerability’ and ‘safety’ through the consultation of experts from different fields. By law, it is the authorities’ responsibility to guarantee a certain water safety for periods of high water levels. Water safety is calculated through statistics that determine return periods of high water levels that caused damaging floods in the past. In this process, numerical models are a common tool to simulate the effect of high water events that determine the flood risk. Risk, in this context, refers to the risk of societal and economic losses implying that protection measures are more strict in relation to areas and activities with a high economic value and dense population. For instance, dikes and other protection measures against high water have stricter specifications for areas with critical economic infrastructures and were more people live, such as in the densely populated west of the country. Potential economic impacts of climate change is made visible in a public platform ‘de klimaatschadeschatter’ (the climate damage estimator), initiated by the Delta Comission, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water, the national water authority (Rijkswaterstaat), the applied water science association (STOWA), regional water authorities, the Dutch association for scientific research (NWO), the Topsector Water, water knowledge institute Deltares, Wageningen University, applied natural science institute TNO, Royal Dutch Meteorology Institute (KNMI) and the (water) business community [

32]. Historically, water management was mainly approached through technocratic solutions provided by engineers, yet a turn in green technocratic solutions invited ecologist to join the safety debate, as nature is seen as potentially contributing to flood and drought solutions [

33].The formal policies around climate adaptation and the implementation of solutions are thus shaped by a (eco)technocratic alliance.

The national and regional authorities implementing flood measures often operate through participatory processes that are framed to be inclusive, though crucial decisions are already taken and the methods rather serve to mobilise allies for the project [

34]. Experts from the field of behavioural change, e.g. applied psychology or participatory arts, are asked to be involved in change management that for instance emphasises on what citizens can do themselves, in a process of slowly moving away from guaranteeing safety at all time [

35]. By stating that climate change and the adaptation towards climate change is a common problem that can only be solved together, ‘good citizenship’ is normalised.

Case study; the Meuse river and the Border Meuse section

The Meuse river is born in France, flows north through Belgium and the Netherlands and meets the North Sea in the port of Rotterdam. The water level of the Meuse in the majority of the river is stabilised through weirs and dams for navigation purposes. Flood events in 1993 and 1995 in the south of the Netherlands brought a focus on flood-management and the development of flood scenarios, reinforced by floods in 2021. The Border Meuse trajectory of the river Meuse marks the Belgium/Netherlands frontiers. The Meuse enters the Netherlands south of Maastricht and is named the Border Meuse from the upstream Borgharen dam till the downstream Linne dam. In this stretch the river is free-flowing. The Meuse is rain-fed and has a mean flow of 230 m

3/s (Borgharen station) with fluctuations between 20m

3/s and 3000m

3/s [

36]. Historically, this stretch of the river was navigable, but the many meanders and accidents let to the building of the Dutch Juliana channel and the Belgian Albert channel. These two channels were built to optimise navigation through Belgium and the Netherlands, and currently the Border Meuse is not used for navigation any more. The agreement between water use sectors and the governments is that the Border Meuse receives a base flow of 10m

3/s. Minor daily fluctuation (hydro peaks) are caused by the hydroelectric power-plants and the opening and closing of the weirs upstream.

This section of the Meuse has seen substantial changes over the last decade through the implementation of the Border Meuse project (2008-2027). This project is one of the proclaimed success stories of climate change adaptation through nature based solutions in the Netherlands. A key framing of the project’s success, is that it combines improving flood safety and nature without society having to pay for the costs. The Border Meuse consortium (the Grensmaas consortium) is the public-private partnership in which the national water authority, nature organisations, the province and gravel extraction companies worked together on the design of the river. Gravel extraction has widened the riverbed to increase space for flood events, with the sale of gravel co-financing the project.

Research activities

Primary data collection was through semi-structured interviews, co-organizing student/practitioner fieldwork activities, observations during public river events, and ecological fieldwork-sampling activities with ecologists and activists in the area. Secondary data was collected through unstructured grey document analysis, as well as academic literature research. An interview protocol was designed to inform interview participants - prior to their participation in the research - of the goal of the research, the use and privacy of data and the aftercare. Oral consent to use anonymised quotes was collected for all individual interactions.

Interviews were conducted between the period of May and August 2022. A total of six river walks were organized in which semi-structured interviews of two hours alongside the river course were conducted. The method of interviewing during river walks was chosen because it visually highlights the materiality of the river and the project, it enables making observations interconnecting the interviewee and the river, and it is a shared experience and not solely an extractive information method. It is an embodied way of connecting self and place, there is room for spontaneity, silence and awkwardness. Through walking, a different balance between the interviewee and the interviewer is created. Two additional semi-structured interviews were conducted with those who physically did not have the capacity for long walks. The interview questions were set up according to themes that reflect our conceptualization of river imaginaries: the river and the river project, past-present-future dynamics, future and future ontology, and epistemic communities.

Additionally, two Climate Cafés were organized in June 2021 and April 2022, involving one week in which a group of students and practitioners learn and talk about water management (for details on activities, see [

37]). The organisation and execution of Climate Cafés provided insights in differences and interactions between communities that hold certain imaginaries. The co-organization of the activities together with practitioners and scientists in a LivingLab setting gave insight into current (applied research) interests and debates in the river, and facilitated a base to build relations around these debates. Moreover, the combination of (young) students and practitioners made the topic of the future for new generations central and embodied.

Further observations during river symposia and ecological fieldwork sampling activities gave insights in current struggles around the river and specific ecological knowledge-production methods. Ethnographic observations and embodied experiences were used to understand truth regimes dynamics, for instance, in knowledge production processes and the role of generally accepted truths. Moreover, topics that brought discussion or emotion were thickly documented.

Finally, the unstructured grey document analysis included events and policy documents that were mentioned or that were related to the information given during the interviews and observations. These included policy documents, news articles, laws and outcomes of legal processes, future visions, social media platforms, art installations and websites of organizations and their activities. Data was processed through a qualitative thematic analysis.

3. Results

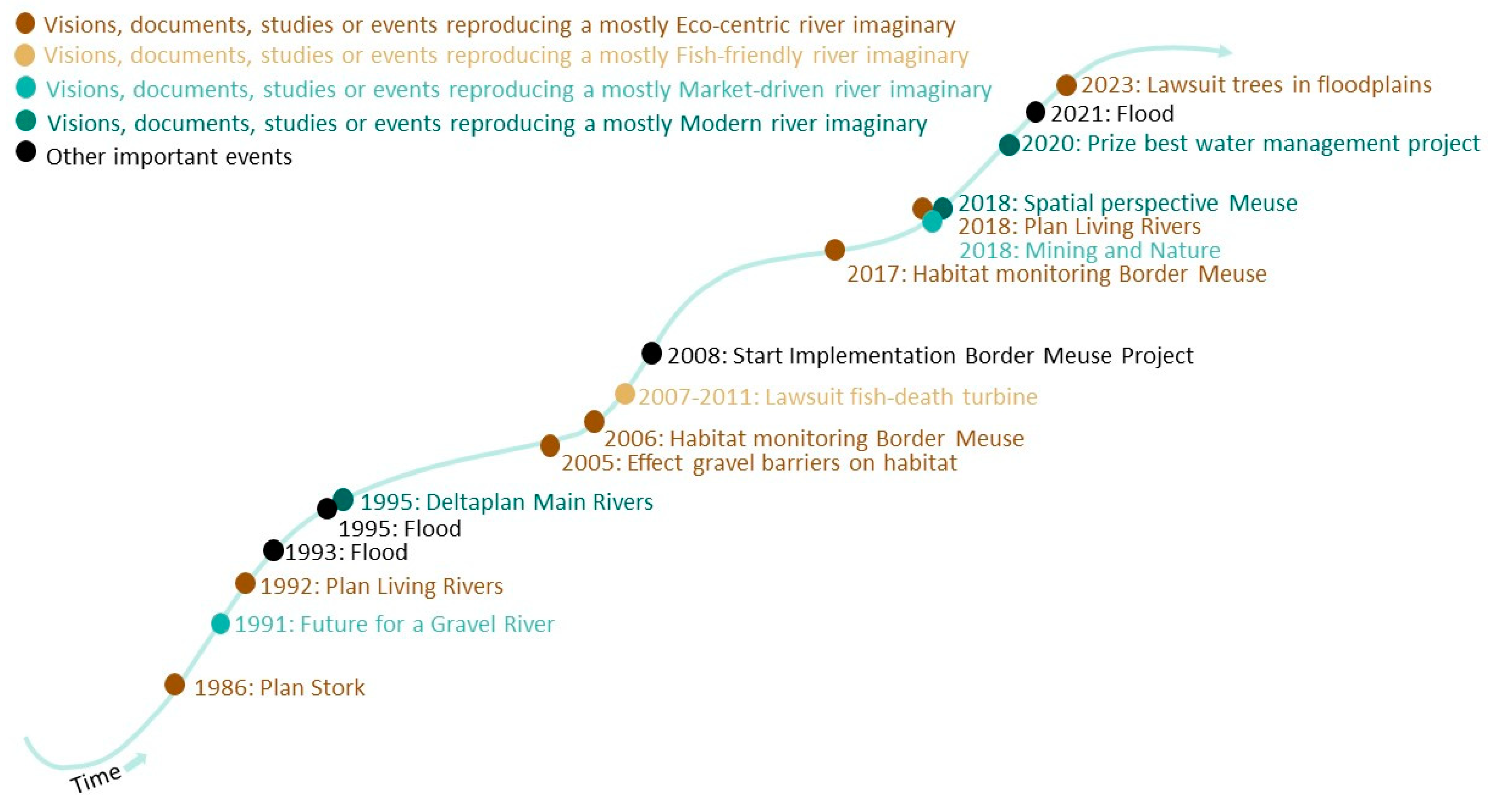

3.1. The emergence and merger of three river futures

In the mid-1980’s, the Dutch landscape was seen as vulnerable and boring; acid rain, dead rivers and biodiversity loss were all coupled to human behaviour [

38]. Recognition of the overexploiting effects on nature gained weight in the political debate. In a national contest with the theme “the Netherlands-river land” a plan named “Stork” presented a new unconventional ecological view on river management and agricultural development. The project team won the contest in May 1986 [

38]. The plan sketched ideas around rivers as connecting features of a landscape, in which ecology could thrive in the riparian zones and valley lands of the rivers. In their vision, rivers were seen as wild and free, full of life, and with space to meander. Specifically, forest and marshland development in the floodplain combined with mineral and sediment extraction was seen as bold, as nature and gravel extraction were seen as two opposite river futures. The plan focussed on new interactions between the natural dynamics of the river, land use, and landscape quality.

In 1987, a book was published to elaborate on the plan with the same name: Stork (Ooievaar) [

39]. Out of this, two organizations emerged: a consultancy office named “Bureau Stroming” and an environmental management/lobby/research foundation named “stichting ARK” which first operated together and later split [

40]. Moreover, the plan led to a more detailed national plan developed by the Dutch part of the World Wildlife Foundation, named “Plan Living Rivers” in 1992 [

41]. Because their visions were seen as unconventional and sceptical questions were asked about the feasibility of the plans, several strategies were employed to convince others of their future river vision. For instance, campaigns were organised for policy makers to visit other rivers in Europe, such as the Allier in France, to show how the aesthetics of such a river could become a potential future river in the Netherlands. Similarities in hydrological and morphological characteristics between the Border Meuse and the Allier river, for instance in bathymetry, hydrological regime and sediment type (gravel), were further explored. Moreover, historical studies were done to understand how the natural river was in the past, for instance which vegetation was growing on the sides of the river, and how old river meanders were situated. From this, the overall vision on the Border Meuse was that the river could be rewilded: a free-flowing river in which ecology could develop freely; where flow regimes could be determined based on ecology instead of navigation because there is no navigation on this stretch of the river, as the canal runs in parallel.

At the same time, the province of Limburg was obliged to supply a large amount of gravel to the national government. Extracting gravel was a sensitive issue in this specific province due to problems with historical deep mining, deep gravel extraction and other pollution cases [

42]. This part of the Meuse is one of the few places in the Netherlands where gravel can be excavated. The national government put pressure on excavation because The Netherlands has to source a certain amount of gravel from its own territory in order to be able to buy gravel from Germany (pers. comm. local authorities, 22-08-2022). Not being able to buy gravel was naturalised as a problem as it would be problematic for the Netherlands being a highly infrastructuralised state (personal communication gravel industry, 19-08-2022). In 1991 the province commissioned the newly emerged consultancy company Bureau Stroming to develop a plan for the development of nature in combination with gravel extraction called “Future for a Gravel River” for this specific trajectory of the Meuse [

43]. The covers of both this plan and that of the earlier plan Stork carry romantic images of a river with vegetation around it, feeding into both historic and futuristic images of the river as a free, wild and romantic place (

Figure 1a,b)

The national ministry supported the call for a more eco-centric way of water management in combination with gravel extraction. Yet, the legal obligation of the national water authority (Rijkswaterstaat) was limited to ‘robust and adequate’ water safety. This meant that the organisation did not have the legal role to develop nature unless it would contribute to a safer river. And, at the bare minimum, nature development and gravel mining should not hamper water safety in any way. The extreme high water events in 1993 and 1995 flooded many households in the Border Meuse area and showed that current safety was not up to the desired standards. This provided the political incentive for the water authority to improve the water safety against flooding in this part of the river, resulting in the development of the Deltaplan Main Rivers in 1995 [

44]. In order to realise this, studies on flood safety were implemented that heavily leaned on hydraulic and hydrological models.

The obligation for gravel extraction, an increased political will to pursue increased flood-safety, and the lobby for eco-centric water management, together made it possible to negotiate designs for the future of the Border Meuse. Crucially, the gravel revenue would pay these ‘win-win-win’ scenarios (pers. comm. gravel industry, 19-08-2022). The negotiation process over the future river design stilted a few times. In 2001 the project almost collapsed because of a sudden increase in the planned amount of gravel extraction. Inhabitants contested and protest groups started to rise, but motivated key people remained to negotiate and in 2008, the first work began (pers. comm. local authorities, 22-08-2022).

Three river futures had to be entwined in one project. The main claim from the gravel miners to be involved was that a total of 35 million tonnage of gravel would be made available for the gravel company, as this amount was needed to make the investments profitable for them. The main requirement for the national water authority was that new flood safety standards would be developed and achieved. And the principal demand from the nature organizations that created the initial Stork river vision was that the floodplain would contribute to rewilding the river. In order to realise this, land owners close to the river, mainly farmers, needed to be bought out. The project and excavation was set to finish in 2021 and the targets for flood safety were set to be reached in 2017. After this, the nature targets were set to be reached in 2018. Yet an economic crisis with low gravel prices around the start of the work in 2008 made that the project was gradually delayed to run up to 2027 in order to make the project economically feasible.

3.2. Contestation and negotiation of rewilding principles

Throughout the process of developing this future river, the vision of a free flowing river was contested. For instance, because it is posited that a flexible river course is not possible according to international agreements between Belgium and the Netherlands, as the deepest point of the river should remain the border between the two countries (pers. comm. local authorities 22-08-2022). Following this reasoning, the river can only be free flowing as long as the deepest point stays in the same place. While in Belgium some villages are gradually deserted to give room to a free flowing river, on the Dutch side all villages along the river remain protected:

“We cannot destroy all the villages to let the natural river exist, but within the constrains we succeeded doing the optimum. A natural river is a river which can do its thing while we look how things evolve”

(pers. comm. Grensmaas consortium, 23-08-2022)

Furthermore, gravel barriers were included in the design of the river which push up the water level of the river. This aimed to prevent the drainage and subsequent lowering of the ground water table in a Belgium nature reserve close by. In 2005, a study was done to determine the effects of the barriers on the ecosystem next to the river, and it was found that it would have a positive impact on the Belgian nature reserve and would not have a negative impact on the river ecology [

45]. Yet, a counter study in 2006 advised against the implementation of high gravel barriers as it may negatively affect aquatic ecology [

46].

This and other counter studies fuel resistance against the designs, most vocally expressed by the anglers association (Sportvisserij Limburg and Visstandverbetering Maas). With some 600.000 members the Dutch anglers organisation is at national level the 2

nd largest sport association in the Netherlands. They systematically collect and share information on fish population and fish spotting. They are critical towards the established nature organisations that initiated plan “Stork”. For instance, at the inlet of the trajectory, a fish nursery was designed, but the lack of water and hydropeaking events made that not many fish survive. The organisation actively campaigned to raise this issue, amongst others through a social media campaign using pictures of rapid hydro peaks that cause fish deaths (

Figure 2a). Established nature organisations responded sceptically towards this and stated that, as it is a rainfed river, fluctuations are natural and also good for the birds and other parts of the ecosystem because they can eat the fish. Moreover, the angler’s morality was questioned by stating that catching fish is not fish-friendly at all (pers. comm. nature organisation, 24-04-2022).

The fish-voice, as represented through the anglers association, was thus largely ignored in the designs. When visiting an area where a fish nursery was planned, a representative of the anglers organisation described that: “This is the only place [in the Border Meuse] where fish-ecology was even a point of discussion (in other parts of the river, fish-ecology was no agenda point). There has been discussions about the inlet, on how much water should be let into Boscherveld [the fish nursery]. For fish, more water is better, but this was chosen differently” (pers. comm. anglers organisation, 24-08-2022)

This inlet has been subject to more fish-debates. The anglers association filed a court trial in 2007 against permits for a hydroelectric installation. The association researched how the propellors of the plant were killing fish (

Figure 2b), and stated that this was not according to the allowed fish-death that a turbine can cause. Representatives of the anglers’ association stated that, in the first part of the trial, the court considered the anglers association as not knowledgeable enough because their research was not formalised. It considered the organisation to be too biased for the results to be trusted in court. Only in 2011, following new studies conducted by organisations with recognised authority (VisAdvies, Deltares and Vivion) [

47], the court decided in favour of the anglers association and against the construction of the hydroelectric installation.

There have been an increased amount of studies on fish wellbeing, specifically for the Salmon as it is one of the target species to realise in the vision. Discussion remains to be evolving around the question ‘what is optimal for what fish?’ as fish are not a homogeneous group. In 2017, another study indicated that low discharge is not ideal for the wished-for fish-types [

48]. When new research on fish was announced, representatives of the anglers organisations decried, “

again a new study” indicating their scepticism on the need for more research by the state only to prove a point they already find clear.

Started a few years earlier, but formalised in 2016, the idea emerged to rename the Border Meuse as the ‘Common Meuse’. The framing was to view the river on both sides as one natural area and to break with the constrains set by the middle of the river being an international border (pers. comm. nature-culture organisation, 02-08-2022). Political and discursive inclusion had clear results; the influence of the fish-ecology lobby increased when dominant nature organisations provided room to contribute to debates about river futures. A vision of the river emerged that connected a living river with fish and underwater life. As fish came to be seen as representing this ‘liveliness’, the fish friendly river vision found its way into the national water authority, where expertise on freshwater ecology increased. Slowly anglers gained more trust in the water governing bodies.

In 2018, 25 years after the first Plan Living Rivers of the Dutch World Wildlife Foundation, a new national river-vision document was published by established Dutch nature organisations [

49]. This document is presented as a counter-document to the dominating national delta plan [

50], as they state the dominant plan does not couple landscape quality with water safety. In their new plan, more attention is paid to a living river, including the development of reserves for underwater life (

Figure 3). Moreover, the background document includes an elaborate history that describes how the natural river started to be canalised and diked to protect people against flooding, thereby breaking away from the rivers’ natural behaviour. In this reflection, the Border Meuse project is seen as a positive example of nature development and water safety by the nature organisations, because ecological targets were present in an early stage of the process. The absence of navigation in this stretch of the river made it easier to focus on such ecological targets.

3.3. The Border Meuse as a success story

In 2020 the project received a price from the Dutch water sector and was presented as one of the best examples of a ‘nature based solution’ for inclusive flood protection and climate change adaptation. The price was awarded based on “

effective, innovative and promising implementation of the national Delta program” [

51]. Overall, public acceptance for the project was high. In order to facilitate a smooth implementation of the project, the Border Meuse consortium was established which carried out an extensive participatory process.

The Border Meuse consortium had the status of a private entity and can therefore be flexible in spending money. In almost all villages near the river, local citizen groups (Klankbordgroepen) were created to include local wishes and doubts during the execution of the project. The participatory process was designed to facilitate a smooth execution of the work and to create local alliance for the project’s objectives. This resulted in formal, but most of all in myriad informal, subtle, strategic actions. Deviants and opponents had to be converted into proponents. An example: in one of the villages there were a dozen of people who would experience nuisance due to the installation of sheet piles during the day. Because they had to sleep during the day due to their night-jobs, the company compensated the whole street and gave them a free stay in a holiday-park for a few days. This would have been far more difficult if the consortium were only a bureaucratic public entity. On initiation, critical groups, such as the BOM (see [

42]) existed, but strong gravel contestation slowly vaporised. Many inhabitants of river villages from the Dutch side of Grensmaas were gradually embraced, adopting the ontological perspective of the consortium’s epistemic community: (person 1)

“The consortium is very open with information so they are to be trusted. Also because the project did end-up the way they said. Before the implementation there was some unrest. Because of stupid people. Fear for change.” (person 2):

“But I find it really beautiful. I feel way less fearful when there is high water. From the house you can see the water increase. Also in ‘93 this was very scary. Now it is safe and it feels better.” (pers. comm., 26-07-2022)

Through this process, the image of the consortium and national water authority shifted as they were previously seen as mere technocrats and now were also seen as nature creators who cared for the river and the people around the river. The consortium and the national water authority actively supported the dream-like rewilding future as an absolute solution to the problems of flooding and biodiversity loss. The studies that supported environmental findings were supported and were framed as additional benefits to secure flood safety and gravel extraction. An activist on the Dutch side of the river states this image shift like this: “RWS’ [the national water authorities’] view on the river in the past was very different, because of stichting ARK [the nature organization] the wild nature is the base.” (personal communication activist and inhabitant Dutch side of the Grensmaas, 04-08-2022)

Moreover, the (self)image of gravel extraction companies shifted. By positioning themselves as the creators of wild nature, they aligned with the dream-like future of a wild and natural river. Reports in collaboration with the butterfly-association positioned the gravel industry as nature creators, as they changed the previous agricultural grounds on the sides of the river into ‘wild nature’ by exploiting the ground [

52]. Supported by this report, the gravel industry describes this image shift like this: “

We [the gravel miners]

create nature by our activities, mining is therefore good for biodiversity and we are the largest nature-development organization.” (pers. comm. gravel industry, 19-08-2022)

These examples illustrate how the Border Meuse became a story of inclusive water governance through normalising practices that aligned with the dominant dream-like river future.

3.4. Continued debates on river futures – a dominant eco-modern river imaginary

It is interesting and important to see how Dutch society, policy-makers and institutions have historically embraced their self-image of a ‘poldering’ and participatory ‘waterboard culture’, convinced by the idea that they have a tradition of solving the core problems by open discussions and inclusive stakeholder negotiations. Dutch water governance is a prime example of this. This water-history based self-image connected to ‘participatory pride’ has remained sturdy even when challenged by, for instance, critical scholars or outsiders who would point at the discrepancies and power plays behind the Dutch ‘polder model’. The relational, network-like and omni-present power in Dutch water thinking (‘we Dutch have water in our genes’ and ‘God made the world but the Dutch made The Netherlands’ -- as if it were not a selective group of rule makers and power institutes who decide on water governance) is deeply ingrained in rule-makers and rule-undergoers. How, herein, norms and behaviour are normalized, shows that Foucauldian discursive power and epistemological belief systems are not just ‘soft’ but have real, material effects, also in river intervention projects.

Illustratively, a few months earlier, an article in The Guardian described the Border-Meuse project as a nice example of river management but also one that would have been impossible to implement in the political context of the United Kingdom [

53]. Contrary to the Dutch citizens’ and water governance self-image, and to the deeply ingrained self-perspective of the Grensmaas as an strongly participatory project and process, the interviewee of the Rivers Trust characterised it as heavily top-down and stated that the United Kingdom “

tend to take a much more bottom-up approach and look to incentivize landowners and farmers by working collaboratively”[

53].

Illustrations of this paradoxical divergence between participatory self-image and actual practice are abundant. For instance, in 2022, two of the Dutch nature organisations filed a lawsuit against the plan of the water authority to remove trees in the riparian flood-zones of the Border-Meuse for flood-safety reasons [

54]. As a result of model studies, the trees were found to hamper flood safety, and thus needed to be cut down. The nature organisations contested this, but without sufficient proof. Early 2023 the court decided in favour of the national water authority and the trees had to be cut. The national water authority responded in one of the practitioners’ news journals: “

We give as much space as possible to nature, but we have to take high-water safety into account” (spokesman national water authority, 08-02-2023 [

55]). The nature organizations reacted disappointedly, but were still convinced that poldering-style collaboration would be possible: “

We hope that despite this ruling, Rijkswaterstaat will still join us in our efforts to give natural processes along the river more time and space” (van Schijndel, 08-02-2023 [

55]).

Since the development of plan “Stork”, an ecological research agenda has been added to the dominant technocratic research agenda which broadened traditional river truth regimes.

Figure 4 summarises the events, visions and studies that were part of this process. Where ecological research initially was seen as biased, it became more and more formalised because established institutions adopted facts and truths that neatly aligned technocentric and eco-centric futures. Through the newly developed trust that nature could contribute to water safety, dominant actors were able to execute within their legal responsibilities. As such, the dominated technocratic truth regime was broadened with more eco-centric sciences, supported by market-driven, exploitative river use.

As was mentioned, the deep trust in, and interconnection of, consensus-based participation and top down-water management led to the adoption of diverse participatory methods. The involved parties in the consortium employed a variety of strategies to create acceptance and allies for the project: from organising trips for policy makers in the planning process, to the compensation of whole streets during the implementation of the project, to framing river management as a common problem that has to be solved in consensus.

In summary, the historically dominant truth regime that focuses on safety is using past flooding events to construct river futures in which the water safety of the river is dominant. The court case about the removal of trees after the 2021 flood indicates that, even in the new constellation of actors, interests and objectives, safety still prevails above nature. This corresponds to a strong modern and market-driven river imaginary in which the river has to be controlled for the purpose of safeguarding and optimizing economic use and minimizing economic and personal losses. Reproducing the past is central in the modern imaginary and the episteme is based on this reproduction in combination with empirical evidence of the current. Through the past and the current, future visions are assessed on (im)probability. This has historically materialized in the form of canalized, fast-draining rivers. The truth regime that contested this, has provided a strong counter river future, which started in the ‘80s and which introduced formalized studies on water quality and biodiversity. It also added new river histories to the river’s future-making process: of riverine histories with deeply ecological values and functions, of pristine-like wild river-nature.

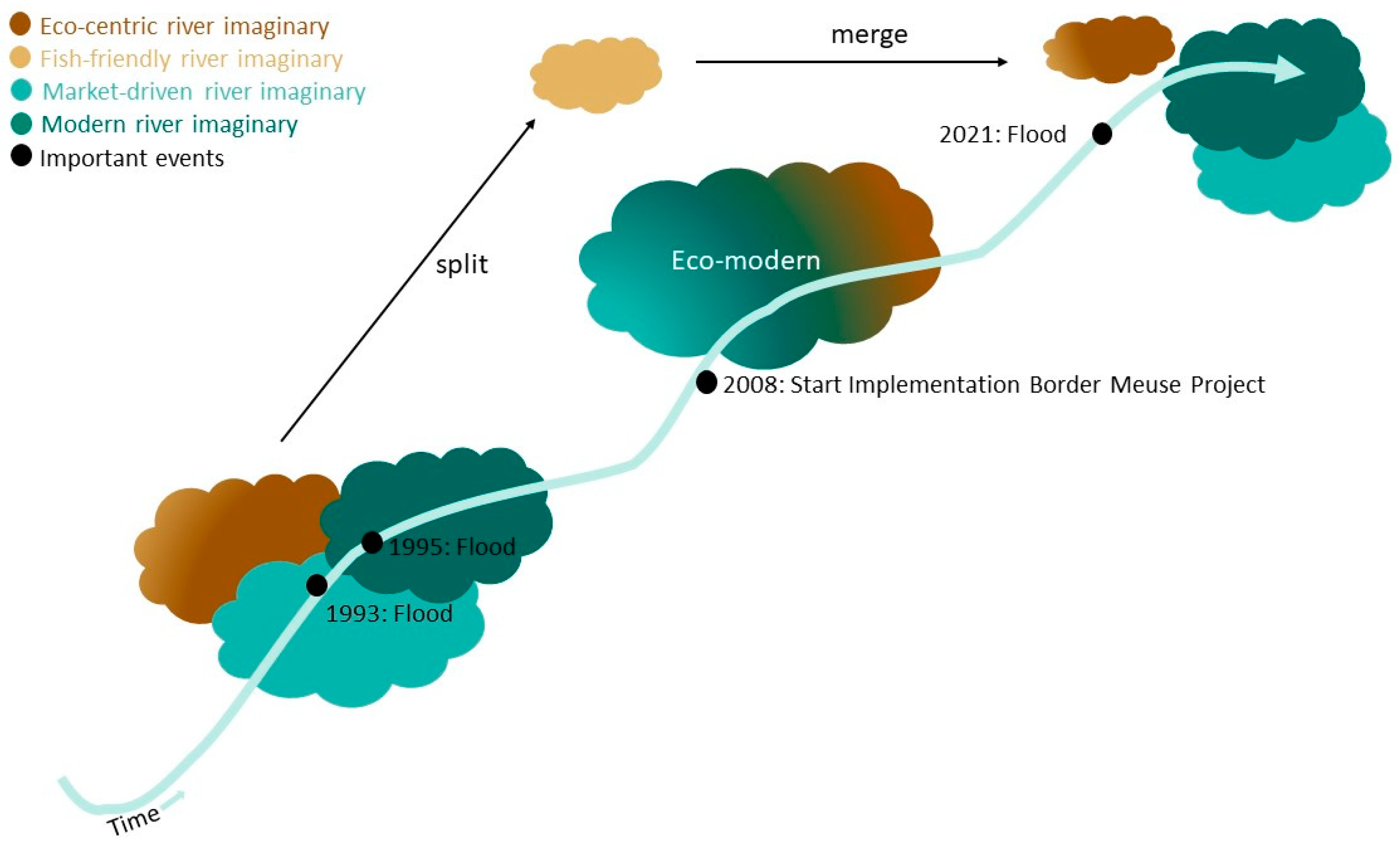

Throughout the process of the project, in which an eco-modernist river was materialized, the truth regimes ‘borrowed’ arguments from one another. For instance, nature as a contribution to safety has helped to develop the idea of nature based solutions and the gravel industry as ‘creators of wild nature’ maintained their privileged position. In this process of borrowing arguments, the three imaginaries (the modern river, the market-driven river and the eco-centric river) merged into an eco-modern river imaginary: a river that is controlled and optimized for safety and ecology, in which the execution is financed by the private sector.

4. Discussion

Through this research, we aimed to understand why societies choose particular directions of change over others, in the context of climate change adaptation in river management. To this end, we scrutinized the future making process of river futures in the Border Meuse river adaptation project, as river futures legitimize and steer adaptation in rivers. The power of river futures, conceptualized as river imaginaries, show how visible power, hidden power, and normalizing power are employed by different epistemic communities to support their river truth. The results tell us that the dominant mode of river knowledge revolved around a modern and market-driven river imaginary: safe and economically sound. The contesting river knowledge revolved around an eco-centric river imaginary: wild and free flowing. In this section, we further interpret how the truth regimes use visible, hidden, and normalizing structures and strategies, to combat for their river future to dominate. We summarize this in

Table 1. The outcome of this confrontation materialized in the Border Meuse as an eco-modern river imaginary: a controlled river that is safe, economically sound, and somewhat biodiverse.

Figure 5 shows how three imaginaries merged, while the fish-friendly imaginary split from the eco-centric imaginary during the project. Yet, in 2018 the fish-friendly imaginary aligned again with the eco-centric imaginary and after the floods of 2021 and close to the finalisation of the project in 2027, the modern, eco-centric and market-driven imaginary split.

Visible power: power over river futures

The dominant mode of river knowledge lies within the realm of the national water authorities. They have the legal role to secure water safety and have to use a set of tools that are pre-determined by national water law to asses water safety. Water safety is inevitably about the future, therefore this type of future dominates visibly. The experts at the institutes, concerned with water safety estimations, have backgrounds in civil engineering, hydrology and hydraulics and have epistemic dominance in producing a river truth. Water safety levels are informed by potential economic and life losses, influenced by a market-driven river imaginary. The visible river future is formalised in the national delta plan, developed under the supervision of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water, which is led by a minister in the government. The respective epistemic community relies on a combination of historical empirical observations and model simulations to formulate probable futures. Interventions to adapt to the river futures are calculated through cost-benefit analyses.

Visible power is contested by the plans that relate to the living rivers future. Counter-facts are produced by presenting alternative ideas on water safety. In this case by widening the riverbed, driven by a market-driven imaginary, and emphasizing that this was also economically feasible. Accepting these counter-facts surfaced several knowledge gaps in the water safety paradigm, for instance on how to calculate water safety with a widened river bed and with vegetation in the flood plains.

Hidden power: power to river futures

The water authorities (at ministry, national and regional level) set the agenda on the questions that are of importance to study. The national water authority primarily involved views and agents of those who are willing to work on water safety. Studies that address other issues were seen as biased and unimportant, as the lawsuit of the anglers association illustrates. In this lawsuit, the anglers were first seen as not knowledgeable enough and after they presented formalised studies, these were seen as biased. Additionally, the lawsuit of the nature organisations against the national water authorities illustrates how, again, alternative views on water safety are marginalised. As such, authorities employed their hidden power by silencing counter facts.

The sole focus on water safety in river management was, however, shortly contested, introducing the relevance of water quality and biodiversity. This was done by showing what happens to water quality and biodiversity if only water safety is taken into account, for example with studies on the influence of the gravel barriers on the Belgian nature reserve. Other type of studies by the ecology epistemic community challenge unequal prioritization of safety and state that safety should also include the ecological quality.

Normalizing power: power within river futures

Water safety is unquestionably moralized through actively framing flood protection as a the only way to not let people drown in a flood. Market-driven arguments are used to define the way to adapt to this by technocratic design of (green) infrastructure. The use of water safety is supported by arguments of feasibility (the economic feasibility of the project/local support, creating allies/subjects), desirability (a clean/safe river), probability (chances of flood/ chances of invasive species that come), and plausibility (reproduction of the past).

Inhabitants are approached as subjects, and are made into allies during the intensive participatory process where internalisation and externalisation of the imaginary takes place. In this process, safety, defined in a statistical way as being protected to events with a certain return period, and the believe in knowing this safety is naturalized. This makes it hard to propose something that does not comply with safety, creating moral superiority. Those that are made allies of a certain future are also the ones who further seek for allies. First the imaginary is internalized, then normalized and finally externalized.

Yet, a debate within the rewilding river future led to the contestation of the eco-modern river imaginary. The particular position of the anglers association in the debate indicates that, although they are invited to the debate on river futures, they had to use the legal system to contest decisions. Nature organisations weakened the position of the anglers association by framing fish death as a natural process and by ridiculing anglers as actually being fish friendly. A fish-friendly river future as foreseen by the anglers association therefore became a counter imaginary. Contestation of river knowledge through own data collection was considered biased at first, which then was formalised to be used in court. Despite their activism, they aligned with the way knowledge is produced by the dominant actors. They first conducted studies deploying their own vernacular methods, but later adopted methods that were recognised and found resonance within the national water authority.

5. Conclusions

We scrutinized the future making processes in the context of climate change adaptation in river management. We conceptualized the power of river futures as river imaginaries to understand our climate change adaptation case study. Through the Border Meuse project, a climate change adaptation project in a stretch of the river Meuse in the south of the Netherlands, we elucidated how three river imaginaries: a modern river imaginary, a market-driven imaginary and an eco-centric river imaginary, merged and materialized as an eco-modern river imaginary. Importantly, not only the river futures merged, also their aligned truth regimes merged. We have shown how the emerging eco-modern river was normalized through extensive participatory practices. Yet, we also found subtle contestation that influences the river agenda and river futures.

The current-day powerful support those imaginaries that keep them in power. For instance, widening the riverbed is perfect for the exploitation of gravel, as it allows to change the perception of gravel extraction from a solely economic activity to a societal activity. To come back to Orwell, we can see how those that control the present, control the future: those that control the future, reinvent the past. Yet, also those that do not have control in the present, have some control on the future, as parts of their futures are borrowed to be used by those who are dominant in the present. For instance, the gravel industry leaned on the eco-centric river imaginary as they supported the widening of the river bed and leaving the area to ‘rewilded’ after they were done with their activities. As such, futures matter, even for those who are not dominating the present, as they can inspire, can change morality and can make the dominant practices change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Methodology, L.J, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Validation, L.J, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Formal Analysis, L.J, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Investigation, L.J.; Resources, L.J.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, L.J.; Writing – Review & Editing, L.J, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Visualization, L.J.; Supervision, GJ.V, L.A.M and R.B.; Project Administration, L.J.; Funding Acquisition, R.B and dr. A.P. Richter. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with support from the Dutch Research Council NWO [Crossing Borders at the Grensmaas project Grant Number 17596]; see also

www.livinglabgrensmaas.nl and was also supported by the ERC European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme [Riverhood, Grant Number 101002921], and the Wageningen University INREF Fund; see also

www.movingrivers.org.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no (steering) role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Farbotko, C.; Boas, I.; Dahm, R.; Kitara, T.; Lusama, T.; Tanielu, T. Reclaiming open climate adaptation futures. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 750-751. [CrossRef]

- Muiderman, K.; Zurek, M.; Vervoort, J.; Gupta, A.; Hasnain, S.; Driessen, P. The anticipatory governance of sustainability transformations: Hybrid approaches and dominant perspectives. Global Environ. Change 2022, 73, 102452. [CrossRef]

- Mills-Novoa, M.; Boelens, R.; Hoogesteger, J.; Vos, J. Governmentalities, hydrosocial territories & recognition politics: The making of objects and subjects for climate change adaptation in Ecuador. Geoforum 2020, 115, 90-101. [CrossRef]

- Muiderman, K.; Gupta, A.; Vervoort, J.; Biermann, F. Four approaches to anticipatory climate governance: Different conceptions of the future and implications for the present. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2020, 11, e673. [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Verrall, B. Mapping the evolution and current trends in climate change adaptation science. Climate Risk Management 2021, 32, 100290. [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Hall, J.; Viglione, A.; Perdigão, R. A.; Parajka, J.; Merz, B.; Lun, D.; Arheimer, B.; Aronica, G. T.; Bilibashi, A. Changing climate both increases and decreases European river floods. Nature 2019, 573, 108-111. [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Abadía, B. Utopian River Planning and Hydrosocial Territory Transformations in Colombia and Spain. Water 2023, 15, 2545. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, P.; Carmona, S. Temporal enclosures and the social production of inescapable futures for coal mining in Colombia. Geoforum 2022, 130, 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L.; Hoogesteger, J.; Boelens, R. (Re) making hydrosocial territories: Materializing and contesting imaginaries and subjectivities through hydraulic infrastructure. Political geography 2022, 97, 102698. [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S.; Kim, S. Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power; University of Chicago Press: 2015; .

- Orwell, G.; Macmillan, D. Nineteen eighty-four; Secker & Warburg: London, 2013; .

- Boelens, R.; Hoogesteger, J.; Swyngedouw, E.; Vos, J.; Wester, P. Hydrosocial territories: a political ecology perspective. Water Int. 2016, 41, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The will to knowledge: The history of sexuality vol. I. 1998.

- Haas, P. M. Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International organization 1992, 46, 1-35. [CrossRef]

- Haas, P. Epistemic communities. 2021.

- Davoudi, S.; Machen, R. Climate imaginaries and the mattering of the medium. Geoforum 2022, 137, 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L.; Hoogesteger, J.; Boelens, R. (Re) making hydrosocial territories: Materializing and contesting imaginaries and subjectivities through hydraulic infrastructure. Political geography 2022, 97, 102698.

- Beck, S.; Jasanoff, S.; Stirling, A.; Polzin, C. The governance of sociotechnical transformations to sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2021, 49, 143-152. [CrossRef]

- Hoogesteger, J.; Konijnenberg, V.; Brackel, L.; Kemink, S.; Kusters, M.; Meester, B.; Mehta, A. S.; van der Poel, M.; Van Ommen, P.; Boelens, R. Imaginaries and the commons: insights from irrigation modernization in Valencia, Spain. International Journal of the Commons 2023, 17, 109-124. [CrossRef]

- Manosalvas, R.; Hoogesteger, J.; Boelens, R. Imaginaries of place in territorialization processes: Transforming the Oyacachi páramos through nature conservation and water transfers in the Ecuadorian highlands. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2023, 23996544231168050. [CrossRef]

- Escate, L. R.; Hoogesteger, J.; Boelens, R. Water assemblages in hydrosocial territories: Connecting place, space, and time through the cultural-material signification of water in coastal Peru. Geoforum 2022, 135, 61-70. [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Goodman, M. K.; Suzunaga, J.; Soler, J. Collective memories, place-framing and the politics of imaginary futures in sustainability transitions and transformation. Geoforum 2023, 138, 103668. [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L.; Boelens, R.; Maat, H. Contested hydrosocial territories and disputed water governance: Struggles and competing claims over the Ilisu Dam development in southeastern Turkey. Geoforum 2016, 71, 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Hoogesteger, J.; Boelens, R.; Baud, M. Territorial pluralism: Water users’ multi-scalar struggles against state ordering in Ecuador’s highlands. Water Int. 2016, 41, 91-106. [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, J.; Cornwall, A. Power and knowledge. The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice 2008, 2, 172-189.

- Gaventa, J. Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis. IDS bulletin 2006, 37, 23-33. [CrossRef]

- Shah, E.; Boelens, R.; Bruins, B. Reflections: Contested epistemologies on large dams and mega-hydraulic development. Water 2019, 11, 417. [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Shah, E.; Bruins, B. Contested knowledges: Large dams and mega-hydraulic development. Water 2019, 11, 416. [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Escobar, A.; Bakker, K.; Hommes, L.; Swyngedouw, E.; Hogenboom, B.; Huijbens, E. H.; Jackson, S.; Vos, J.; Harris, L. M. Riverhood: Political ecologies of socionature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. The Journal of Peasant Studies 2023, 50, 1125-1156. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Nederland voorbereiden op gevolgen klimaatverandering . (accessed 19-12-, 2022).

- AnonymousAdaptieve Uitvoeringsstrategie Maas. Deltaprogramma Maas 2019.

- AnonymousDe Klimaatschadeschatter. https://klimaatschadeschatter.nl/ (accessed 09-01-, 2024).

- Disco, C. Remaking “nature”: the ecological turn in Dutch water management. Science, Technology, & Human Values 2002, 27, 206-235.

- Roth, D.; Vink, M.; Warner, J.; Winnubst, M. Watered-down politics? Inclusive water governance in the Netherlands. Ocean Coast. Manage. 2017, 150, 51-61. [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Warner, J. F.; Winnubst, M. Een noodverband tegen hoog water: waterkennis, beleid en politiek rond noodoverloopgebieden; Wageningen UR: 2006; .

- Asselman, N.; Barneveld, H.; Klijn, F.; van Winden, A. Het verhaal van de Maas. 2018.

- de Jong, L.; Boogaard, F.; Daumal, M.; Lima, R. Klimaat-café: samen denken en praten over waterbeheer. 2015, 10-11.

- de Bruin, D.; Hamhuis, D.; van Niewenhuijze, L.; Overmars, W.; Sijmons, D.; Vera, F. Het plan "Ooievaar": een bespreking. 1987.

- Bruin, D. d.; Hamhuis, D.; Nieuwenhuijze, L. v.; Overmars, W.; Sijmons, D.; Vera, F. Ooievaar: de toekomst van het rivierengebied. Stichting Gelderse Milieufederatie, Arnhem 1987, 29-40.

- Anonymous25 Jaar Ark: Hoe het begon. https://www.ark.eu/over-ark/ark-organisatie/25-jaar-ark/hoe-het-begon (accessed 29-09-, 2023).

- AnonymousRuimte voor levende rivieren. Achtergronddocument. Stichting ARK, Natuurmonumenten, Vogelbescherming, Landschappen NL, World Wildlife Foundation 2018.

- Warner, J. In Framing and linking space for the Grensmaas: Opportunities and limitations to boundary spanning in Dutch River management; Water governance as connective capacity; Routledge: 2016; pp 89-108.

- Helmer, W.; Overmars, W.; Litjens, G. Toekomst voor een grindrivier. Hoofdrapport.Stroming BV, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 1991.

- Valkering, P.; Rotmans, J.; Krywkow, J.; van der Veen, A. Simulating stakeholder support in a policy process: An application to river management. Simulation 2005, 81, 701-718. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; de Vocht, A. Effectbeoordeling van grinddrempels op beschermde soorten en habitattypen in de bedding van de Grensmaas; Bureau Drift: 2005; .

- AnonymousRapport bedding Grensmaas. Maas in Beeld 2006.

- Seerden, R. J. G. H.; Schelfhout, T. M.; Sledders, J. N. F. Hoger beroep: ECLI:NL:RVS:2012:BV3249, Bekrachtiging/bevestiging. 2011.

- Liefveld, W. M.; van Kessel, N.; Achterkamp, B.; Dorenbosch, M. Maas in Beeld Grensmaas - Zomerbed Gebiedsrapportage 2017. Bureau Waardenburg 2017.

- Beekers, B.; Van den Bergh, M.; Braakhekke, W.; Haanraads, K.; Litjens, G.; van Loenen Martinet, R.; van Winden, A. Ruimte voor Levende Rivieren—Want levende rivieren geven ruimte. Ruimte voor Levende Rivieren—Want levende rivieren geven ruimte 2018.

- Deltaprogramma Maas Ruimtelijk Perspectief Maas Positionering, kansen en ambities in relatie tot maatregelen hoogwaterveiligheid. 2018.

- Glas, P. Award session. https://magazines.deltaprogramma.nl/deltanieuws/2020/04/zonnetje (accessed 29-09-, 2023).

- Vliegenthart, A.; van der Zee, F. Delfstofwinning en natuur. 2018.

- Weston, P. ‘This is what a river should look like’: Dutch rewilding project turns back the clock 500 years. The Guardian 2022.

- Visser, V. E. H. G.; de Vries, E.; Klijn, A. R. Zaaknummer UTR 22/1262. 2023.

- AnonymousNatuurmonumenten en ARK verliezen rechtszaak riviernatuur Grensmaas. https://www.h2owaternetwerk.nl/h2o-actueel/natuurmonumenten-en-ark-verliezen-rechtszaak-riviernatuur-grensmaas (accessed 29-09-, 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).