1. Introduction

The major contours of human induced changes in the earths’ atmosphere and biosphere are well established, including the interdependent acceleration in climate change, the loss of species and genetic diversity, land and soil degradation, and decline of water quality (Steffen et al., 2015; Diaz et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2023). To enhance the resilience of life support systems to shocks in the face of climate change we need a widespread engagement in place-based regenerative action and improved approaches to governance that empower local actors. Most recent expert reports suggest we have a ten-year window to effect such fundamental changes (IPCC, 2023). The need for novel approaches to social coordination in governance systems with multiple levels is demonstrated by the limitation of existing mechanisms including government regulation and market competition to maintain vital ecological systems in cases where humans depend on their services (Dietz et al. 2003; Ostrom 2009). One reason that these mechanisms have not delivered better outcomes is their exclusive adherence to a scientific approach which valorises abstract knowledge and sectoral perspectives over other knowledge traditions (Hulme 2010; Turnhout et al. 2016). Within scientific disciplines, technical, social and ecological systems are often considered apart, and universal applicability of knowledge is considered a quality criterion. This often blinds to cross-sectoral influences, for example, a wide range of current sectoral approaches for mitigation of climate change with technological innovation in energy and transport systems to reduce carbon emissions often increasing pressure on land and biodiversity. Instead, the challenges of clean energy, a resilient biosphere, and sustainable food and social welfare systems should be considered as inseparable and embedded in a dynamic and tightly coupled social-ecological-technological system (Benett and Reyers, 2024; Folke et al., 2016). Greater reflexivity of how we know associated blindspots is paramount. Moreover, improved coordination across different levels of social organisation is also required, also in view of the need to consider telecoupling of local and global changes (Munroe et al., 2019; Oberlack et al., 2018), and the value of different approaches to understanding environmental change across levels (Tengö et al., 2014).

To address these challenges, this paper advances the concept of regenerative governance and a purposefully designed scenario approach to improve social coordination for regenerative action across adequate spatial scales. Regenerative governance is conceived as a novel form of social coordination for pluralist societies, that is decentralized to better cope with place-based complexities, whilst also being well-connected across governance levels to allow for mutual learning across diverse landscapes, social groups, and levels of social organisation. Building on the concept of transformative governance (Chaffin et al. 2016), regenerative governance is designed to contribute to intentional shifts to alternative systems (or regimes) with different structures and processes, and new actor-constellations that change prevailing social norms and values that are ordering principles in societies. Regenerative governance is however unique in that it has a clear ethical axiology to provide a shared sense of direction through its tie to the ethical premises of ‘multi-species sustainability’ (Rupprecht et al. 2022) that details human responsibilities towards the web of all living species. Such responsibilities may be understood and met in adaptive and self-regulating governance systems that are polycentric (Ostroem, 2010) and emphasise place-based action by diverse interest groups. In such multi-stakeholder participatory processes for regenerative sustainability with net positive outcomes (in this case for multiple species), we should however also make explicit different assumptions and ‘understandings of what matters in shaping behavioural patterns’ that need to be changed or reinforced (Robinson and Cole, 2015). Such different understandings, or ‘ontologies’, deeply affect how we view our own human agency, and therefore what actions we can conceive of and prefer to prioritise. This paper therefore posits that engagement in regenerative governance and action requires building societies’ capabilities, structures and processes that help us to reflect, deliberate on and transcend our own ontologies, and paradigms that arise from them, when circumstances in our rapidly changing world make this necessary. This according to Donella Meadows is the highest order leverage point for societal transformations (Meadows 1999).

More specifically, this paper proposes design attributes for scenario-based governance processes, that leverage scenario approaches to foster the capability of transcending prevailing paradigms and engaging in such an ontological shift. The role of scenario approaches in transformative governance has been discussed (Chaffin et al. 2016; Garmestani et al. 2020, Walker et al. 2004). Different approaches to futures beyond simulation modelling, including participatory visioning and narrative scenario approaches are increasingly drawn upon in policy and practice (Wiebe et al. 2018; Andersson 2018). Scholars however also point out the lack of reflexivity in scenario approaches on how decisions on boundaries of processes and contents can influence the outcomes and impacts (Lazurko et al., 2023; Rutting et al., 2024), and highlight recurrent patterns and a lack of diversity in resulting scenarios. Lazurko et al., 2023 developed a framework for more reflexive scenario practice based on a literature review.

Building on this work this paper presents improved guidance based on a set of design criteria for reflexive scenario-based governance approaches that are suitable for multi-level governance processes, embrace complexity, ambiguity and ontological plurality, and highlight different understandings of human agency associated with different ontologies. This guidance was iteratively refined in a four-year transdisciplinary approach (König 2018; Vienni-Baptista, 2024; Deurderwaerdere, 2024) involving a participatory scenario approach to develop possible diverse futures in how we engage with water and land in Luxembourg in 2045. This process engaged over 100 opinion leaders and decision-makers from public authorities, NGOs, farmers, and scientific experts. The resulting set of three ontologically differentiated scenarios is designed for scaffolding dialogues across a plurality of viewpoints to enable a more reflexive governance process (Popa et al. 2015). Each of the narrative scenarios shows how a disparate set of values tied to a different ontology and associated understandings of human agency plays a significant role in the distribution of attention and resources. This distribution shapes the unfolding future in tandem with coupled cross-scale phenomena such as accelerating global environmental change, social instabilities, and disruptive technologies. The trajectories of these futures emerge from dynamics and disruptive events in tightly coupled complex social ecological systems. The results section then also describes two situations of application of this scenario set. Implications and outcomes of working with an ontologically differentiated scenario set, and their potential to counter effects of polarization and inaction from unstructured plurality in diverse groups, are critically discussed. The conclusions draw more generalized recommendations on the design of scenario approaches for regenerative governance and discuss needs capability building to engage in relational ontologies, transcend prevailing paradigms, and work with scenarios that enable this in practice.

2. Seven Design Attributes for Cross-Scale Scenario-Based Regenerative Governance

In the field of sustainability science, scenario approaches are increasingly used in transdisciplinary and participatory research processes, to equip participants with shared reference points in the future that go above and beyond extrapolations based on individual past lived experiences and current knowledge. Scenarios are often defined as coherent, internally consistent and plausible descriptions of potential futures of a system that are developed for a specific purpose (Drenth et al., 2018; Ramirez and Wilkinson, 2016). Scenarios can be used exploratively or normatively (Wiek et al., 2014). Choices in process design, methodology and characteristics of scenarios all matter in determining the outcomes and impacts of the scenario process (Lazurko et al., 2023). Beyond the question of whose perspectives are represented in the process, like any conception of a complex system, scenarios include choices of focal spheres, elements, and influences across these. Such judgments determine what aspects of realities the scenarios reveal, suggest, distort or conceal, and thus also affect their transformative or regenerative potential. Scenario processes in sustainability science and multi-level governance contexts have however been criticised in that they often lack the reflexivity required to make explicit the basis on which such choices and judgments are made (Lazurko et al., 2023). Similarly, Rutting et al.’s (2024) critical review pointed to a lack of reflexivity and alternative view points and a domination of scenarios with neoliberal tendencies. Lazurko’s literature analysis of seventy-two cases of social ecological scenarios demonstrates clear biases that prohibit open exploration of how suites of framing and methodological judgments delimit the boundaries of the future in particular ways. Explorations across multiple systemic scales were often developed in a more positivist epistemology, whereas pluralism was often associated with more normative and localised aspirational visioning processes that did not embrace complexity. The study proposed a reflexive framework guiding researchers through ten boundary judgements that allows amongst other things to design scenario approaches with enhanced transformative potential. The frameworks’ focus on linear trajectories however leads to a neglect of understandings of different forms of human agency in systems. Secondly, the focus on how system boundaries are defined in abstract terms does not consider boundaries that naturally arise from and interplay between participant perspectives and real-world situations or places. Thirdly, this framework does not accommodate more dynamic understandings of change, such as in process-relational ontologies that describe phenomena as emergent properties at specific points in time from diverse intersecting processes that have different time scales.

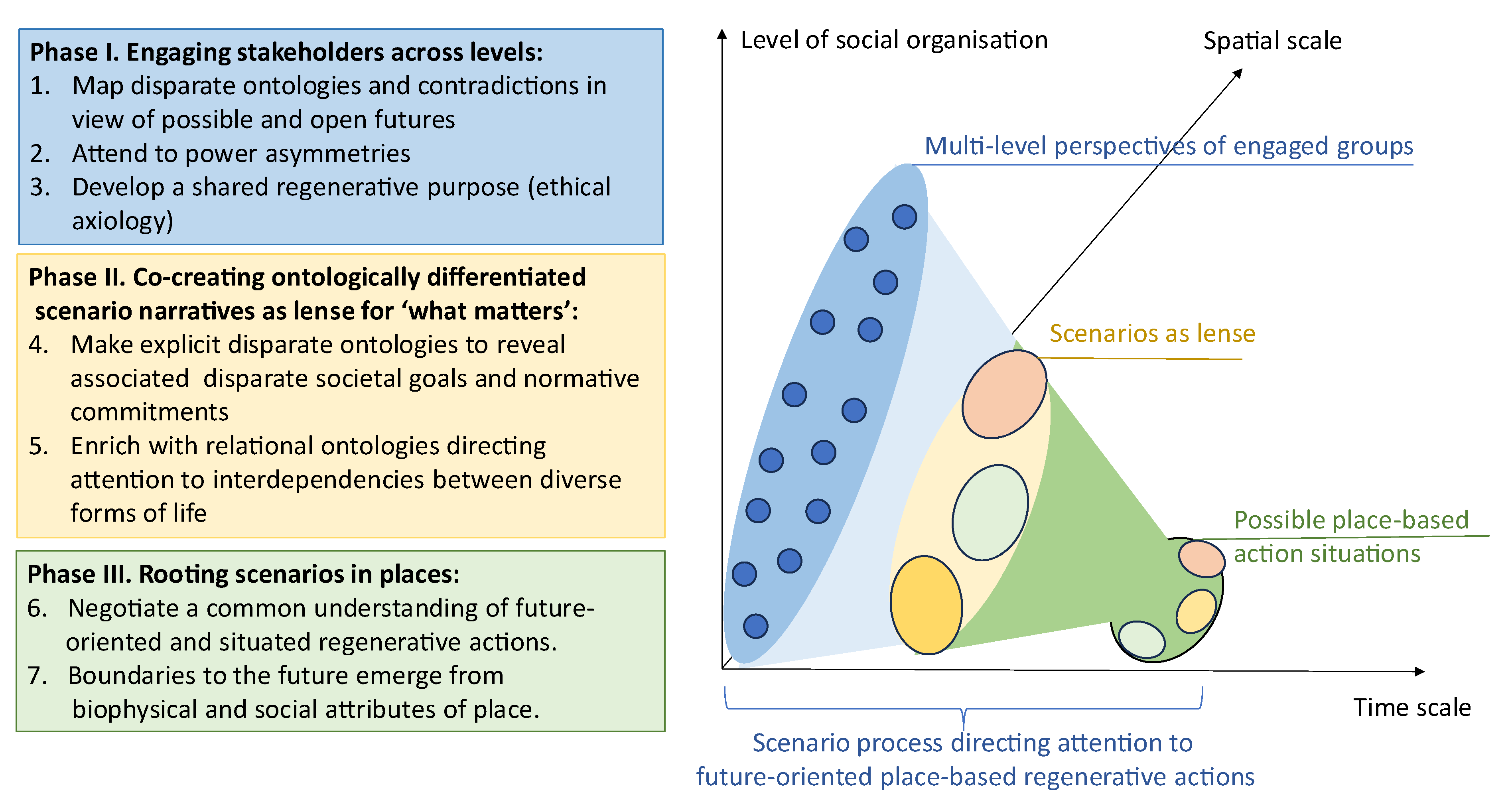

This paper develops improved guidance based on a set of design criteria for a scenario approach that was trialled and refined in practice. The resulting scenario set breaks with prior described patterns in scenario development in significant ways. In this approach, scenarios are differentiated at the ontological level to enable participants to reflect on and make explicit their ontological assumptions and different views on human agency. The resulting simple framework for making reflexive judgments and choices in scenario-based regenerative governance processes distinguishes three phases with key design attributes (see

Figure 1): Phase I involves the mapping and engagement of key stakeholders, understanding the diversity of viewpoints, and conveying a shared purpose for their engagement in the process, in a way that is sensitive to power asymmetries. Phase II provides guidance on the co-creation of ontologically differentiated scenarios in a way that attends to the intricate intertwining of power and knowledge and puts emphasis on different understandings of human agency in societal transformations. The main scenario scaffolds are defined (some call this scenario skeletons), including the drivers and their interactions across different spheres (social. ecological, technological), which are considered across different scales. Phase III highlights the type of boundary work that can be mediated through the consideration of place and place-based (human and more than human) communities. The resulting scenarios can then be used in multi-stakeholder processes considering diverse action situations with different biophysical constraints or limitations from local capabilities or interests, whilst avoiding unnecessary abstract conceptual boundaries or constraints. Each phase is considered in more detail in turn.

The seven design attributes of each phase of the prototype scenario approach are detailed in the boxes on the left. The scenario process starts by engaging stakeholders active across different levels in multi-level governance systems (e.g., local farmers, representatives of municipalities, national public authorities, or ministries, NGOs, scientific experts, and others). The development of the shared purpose of empowering place-based ‘regenerative actions’ presents the first normative boundary – or better - an ethical axiology – to direct gazes towards shared overarching goals. The co-creation of ontologically disparate scenarios reveals different objectives and normative commiemtnst within that overarching goals highlighting different understandings of human agency. Last, rooting scenarios in place-based understadings reveals boundaries to futures emerging from human interactions embedded in biophysical and social attributes of place.

2.1. Phase I. Engagement of Stakeholders Across Multiple Governance Levels

Building on the concept of transformative governance (Chaffin et al. 2016), regenerative governance is designed to contribute to intentional shifts to alternative systems (or regimes) with different structures and processes, and new actor-constellations that change prevailing social norms and values that are ordering principles in societies. If successful, such processes can change relations between people and how people relate to their environments (Moore and Milkoreit 2020). Central to transformative governance processes (Chaffin et al. 2016) is therefore that they seek to engage and connect different groups across governance levels, including actors with place-based knowledge. Key is also the inclusion of salient local ‘seeds of change’ and social innovations capable of disrupting current prevailing structures, practices, and norms (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2020; Pereira et al. 2021).

Mapping ontological pluralism: Regenerative governance requires including different types of knowledge in deliberative processes. Relying solely on scientific experts’ ‘objective’ science and knowledge can lead to the neglect of more fundamental questions at the centre of just agricultural transformation because they bracket out prevailing norms and other conditions that stabilise existing paradigms and social-cultural dynamics (Turnhout et al., 2016; Hulme et al., 2009). This neglect can make regenerative practices prone to discursive hijacking and undermine the transformative potential of regenerative practice in general (Sanford, 2023; Gorissen et al., 2024). Regenerative governance, like regenerative sustainability therefore requires making explicit the disparate assumptions and understandings of the world that underpin different forms of knowledge and practice (Robinson and Cole, 2015). It is therefore a governance process that needs to accommodate ontological pluralism (Stengers, 2010; Escobar, 2018).

Therefore, we argue in this paper, that it is useful to have some notion of how different ontological assumptions held by different (groups of) stakeholders may help or hinder their mutual understanding and agreement on possible pathways for concerted action. We therefore develop a scenario approach that helps making such ontological assumptions and associated implications for how issues are understood and acted upon in different ways, explicit and subject to discussion. Careful conduct, documentation and analysis of interviews and multi-stakeholder workshops can help to discern different belief systems and underlying ontological assumptions. Approaches to analysis can involve discerning the use of certain ‘constitutive’ metaphors in narratives, which can be indicative of fundamental ontological assumptions about a problem settings or ‘framing’ (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Schmitt 2005). The use of key framing metaphors can suggest patterns of relationships associated with actions along a certain direction (Dorst 2015; Newell 2012).

In this project Lakoff and Johnsons (1980) distinction of three fundamental understandings and assumptions of ‘what matters in the world’ proved very helpful in identifying a set of three clearly differentiated narratives that emerged from the analysis from different interviews and workshops. Their simplified distinction of the three (archaetypal) ontologies of positivism (objective truth mirrors reality, science can represent reality), constructivism (truth is social convention), and experiential realism (truth is what works for embodied beings in interaction and cognitive connection with their environments) has been widely criticised. Critiques include that it is an oversimplification that does not reflect the complexity of individual ontologies (Schmitt 2005), and that it is biased towards distinct Western scientific modes of understanding the world. However, in the Luxembourg setting, with stakeholders with educations in different disciplines and belonging to different professions, narratives by stakeholders proved relatively well-aligned and grouped accordingly. Different patterns in problem-description and preferences for courses of action could be discerned for different groups of stakeholders.

Attend to power asymmetries by highlighting links between power and knowledge: The more differentiated view of different actor groups that are engaged and active at different governance levels however also requires attending to power asymmetries (Dinesh et al. 2021). For example, whilst traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) has now gained a foothold within international assessments such as IPBES reports, the mainstream of environmental, agricultural, and ecological decision-making and governance does not (as yet) develop a space for such ways of understanding (Tengö et al., 2017). Potential contradictions between experts, and mismatches in power are rarely adequately discussed. The need to avoid the production of representations that reinforce problematic existing ontological commitments which sustain and enforce the instrumental use of land and agricultural resources are generally ignored. Therefore, it is key that scenarios highlight and make explicit links between power and knowledge. How knowledge is produced and legitimised and whose knowledge is considered relevant in such cases are inseparably intertwined (Jasanoff 2004). Using heuristics such as ‘Socio-technical imaginaries’ (Jasanoff and Kim 2015) in scenario approaches for structuring differentiated scenario meta-narratives can help to craft compelling narratives on how science and technologies can enable or restrict thinking about different possible worlds, affect distribution of rights, responsibilities, and voice, and how they can mediate between different interests and viewpoints, or how values can be enacted through certain technologies but not through others. STIs are collectively held, institutionally stabilised, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, with a shared understanding of social life and social order attained by and for advancing science and technology (Jasanoff and Kim 2015). This heuristic is particularly helpful for the differentiation of scenarios with respect to the role of science in governance. In a similar vein, this heuristic can also be adapted to highlight how changing imaginaries of human-ecology relations to an understanding of multi-species sustainability and interdependence can also present a “deep leverage point” (Vervoort et al., 2024; Chhetri et al., 2023). (Ideally, stakeholders can ideally engage in a plurality of knowledge generating processes, for example with citizen or community science, that produce evidence that is legitimised, credible and actionable across interest groups (including other species above and below soil who are represented by proxy) and human actors engaged at different levels of social coordination and spatial scales. But this consideration is beyond the scope of the present paper).

Developing a shared purpose: Regenerative governance is a unique conception of governance in that whilst it supports ontological pluralism, it has a clear ethical axiology to provide a shared sense of direction. For this purpose, it is tied to the ethical premises of ‘multi-species sustainability’ (Rupprecht et al. 2022) that details human responsibilities towards the web of all living species. Such responsibilities may be understood and met in adaptive and self-regulating governance systems that are polycentric (Ostroem) and emphasise place-based action by diverse interest groups. Regenerative design and practice promote engagement with land and other species to create whole systems of mutually beneficial relationships across different species, with self-reinforcing cycles of wellbeing (Hawkins, 1991; Reed, 2007; Mang and Haggard, 2016; Wahl, 2016). Rooted in living systems theory and radical ecologism, regenerative design has evolved over 40 years mainly as practice-based approach in community work. A recent surge of theoretic re-interpretations seeks to give it more traction in academia (Buckton et al., 2023; Fischer et al., 2023 and Tabara, 2023). Practices of adopting nature-based solutions with attention to equity in environmental governance and spatial planning, such as to establish riparian buffer strips along water courses to prevent flooding and capture nutrient run off, as well as establishing Greenbelts around cities to enhance food sovereignty and resilience to climate change are common examples. Similarly, regenerative agriculture comprises design and practice aim to improve the health of ecosystems and people by attending to biodiversity, healthy soil, and working with nature’s cycles (Siegfried 2020; Seymour and Connelly 2023). Such regenerative farming initiatives that are in general well aligned with principles of agroecology, including agroforestry, that seek to harness ecological interactions and social innovations to replace chemical inputs and enhance social justice in food production.

The resulting purposeful inherent tension in the proposed governance approach - between the goal to be supportive of and make explicit ontological pluralism and a strong normative axiology of a multi-species sustainability ethics provides a creative dialogic space that invites reframing current thinking and doing by all who engage in it.

2.2. Phase II. Co-Creating Ontologically Differentiated Scenario-Narratives

The proposed scenario approach is designed to ensure that governance can support multiple narratives (Wyborn, 2015). Narrative scenarios offer a promising way to enhance the transformative potential of governance processes by highlighting a diversity of understandings of what matters in increasingly culturally diverse societies and thereby enhance the sensitivity to ontological and epistemological pluralism in policymaking and in society at large (Hulme, 2009; Turnhout et al., 2016; Lehtonen et al., 2016; Escobar, 2018; Diaz et al., 2019). If purposefully designed, such scenarios can help us challenge perceptions, assumptions and worldviews and open a dialogic space between ‘what is and what if’ and between the known and the unknown (Ramirez and Wilkinson 2016; Kahane 2012; Ogilvy 2002; Muiderman et al. 2020; Mangnus et al. 2021). Narratives, that are coherent sets of stories, serve as fundamental communication mechanisms to construct individual and collective meanings (Bruner 1991). They can communicate reflections on community or identity or ways we make meaning of certain experiences. Whilst narratives as such are perhaps the most common medium of cultural expression, organisation and learning, dominant narratives in turn create and can strengthen existing cultural contexts. This presents strong systemic feedback loops that can be used to reinforce or break prevailing patterns of behaviour (Chabay 2019). Moreover, overarching narratives can frame the way we understand our cognitive process and our relation to knowledge and particular ways of knowing such as Western science (Lakoff 2010; Schön and Rein 1994). On the other hand, irreconcilable underlying assumptions and structures that shape beliefs, perceptions and appreciation that are usually not made explicit may prevent different groups with different interests and stakes to share a common understanding of and arrive at concerted action on the situation (Schön and Rein, 1994). Systemic transformations will benefit from open spaces for reflection and a higher order dialogue about our language, concepts, how we make meaning and how we associate values with such meanings. Such higher order dialogues are a prerequisite for attributing new meaning, new realities and new coordinated behavior.

In this project we argued that revealing of different ontologies is helpful for reflexive engagements: Just focusing on producing ‘objective knowledge’ we all too easily forget that everything we see is filtered through our individual and collective cognitive apparatus and conceptual systems (Maggs and Robinson, 2016). Such assumptions deeply affect how we understand the world and view our own human agency. Therefore, the challenge we face in the 21st century is about developing an enhanced reflexivity about why we know, how we know, what we wish to know, what we know, and how we act (Mangnus et al. 2021; Popa et al. 2015; van Mierlo 2010). This may be best illustrated by the map-making metaphor: The maps we draw shape our interaction with the mapped territories and evoke in turn that we change these territories once they are mapped. In other words, the systems we seek to understand are created by the questions we raise (Allenby and Sarewitz 2011; Maggs and Robinson 2020; Robinson 1991). We therefore decided to differentiate our set of three scenario meta-narratives according to the patterns we had mapped across interviews and workshops, loosely corresponding to Lakoff and Johnsons triad of Western archetypal ontologies.

Enriching with relational ontologies: Scenarios can be designed to relate profound changes in understandings of human-ecology relations towards seeing humans as part of a web of diverse life forms who co-constitute each other as in regenerative design and resilience thinking (Reed, 2007; Folke et al., 2016; Raymond, 2017; Benett and Reyers, 2023). This shift in understanding directs human attention back to the most fundamental conditions of existence. In the context of better understanding human-multispecies relations across scales, recent literatures on social ecological systems research and sustainability science have witnessed an ontological turn: Scholars advocate a switch from studying interacting entities to thinking and analysing in terms of continually unfolding processes and embodied experiences that inform our ethics (West et al. 2020, Benett and Reyers, 2022). This ontological shift calls for a fundamental reconstruction of language, concepts and representations. An individual scenario meta-narrative can be designed in support of a relational understanding of the world highlighting mutual influences between disparate elements and entities over time. As part of a set of ontologically differentiated scenarios implications of how disparate ontologies suggest different courses of action will become clear. Neither Whitehead’s (1929) process relational ontology that is now often cited in sustainability science, or Varela et al. (1992) enactivism that sees reality as emergent from structurally coupled embodied cognitive processes and biophysical environments, neatly fit into the Lakoff and Johnson’s triad of archetypal ontologies. The triad represents loose guidance only and can of course be modified according to patterns observed in stakeholder discourses in different settings.

2.3. Phase III. Rooting Scenarios in Places- Negotiate Possibilities and Scenario/ System Boundaries with Reference to Diverse Understandings

Negotiate a common understanding of possible place-based actions: It is necessary to overcome barriers to mutual understanding due to the lack of shared experiences between diverse actor groups. Stimulating metaphorical imagination and making references to places that all participants know and can relate to experientially can help. In designing participatory scenario approaches it can therefore be helpful to consider social interactions as situated in different settings or ‘stagings’ (Oomen et al. 2022) and to reflect on the situatedness of the process and how settings – or environments – can influence the quality of social interactions. The selection of places for staging a scenario process can also be done in view of creating spaces for experimentation and local diversification and strategically selecting places where smaller scale changes can potentially feed into innovation in larger scale systems.

Staging negotiations on the meaning of different scenarios in the content of specific places we can gain a new understanding of territories and places as ‘hybrid realities’ that we shape as we perceive them, and that in turn shape us. Latour warns of the societal inertia from polarization between conflicting world views of those pursuing modern ideals in terms of globalization with the help of abstract science and technology and those who aim at regional autarchy and building local communities and identities. He asserts that we will only survive as a species if we all learn to fashion our territories as dwelling places for webs of different life forms that we are part of and dependent on (Latour 2018). Using scenarios as overarching conceptual frames that make explicit such disparate underlying assumptions allows such differences to become subject to deliberation.

Understanding place-based boundaries to future possibilities: Understanding place and specific biophysical and social-cultural attributes will allow to negotiate boundaries with respect to realities that can be experienced and hence can make sense to all engaged.

3. Research Approach and Methods

Transformative sustainability research develops concepts, methods, processes and spaces for knowledge co-creation and action across different interests and expertise, to improve the self-organisation of systems that are not sustainable (König & Ravetz, 2018). The participatory multi-stakeholder scenario approach was a first example of transformative sustainability research in Luxembourg. The aim was promoting systemic thinking about our future engagements with water and land in diverse stakeholder groups that reveals different and sometimes conflicting problem framings with their possible ontological roots, to foster reframing and identification of promising courses of action that resonate across different stakeholder groups. This transdisciplinary research approach (Vienni-Baptista, 2023; Deurderwaedere, 2023) was situated in already established sites of two river-partnerships with promising seed projects. The design of the scenario process drew on insights from the body of literature on transformative sustainability science and future studies (Schneidewind and Singer-Brodowski 2013; Miller 2013; Wiek and Lang 2016; König 2018) and scenarios (Normann 2001; Ramirez and Wilkinson 2016; Ogilvy 2002; Kahane 2012; Elahi 2011; Van der Heijden 1996; Vervoort et al. 2015).

Similar to the participatory inquiry paradigm described in Heron and Reason (1997), the ontology that is the basis for this research design is close to Varela’s (1992) enactivism and is founded on beliefs in an emergent and participative reality that is co-created by structurally coupled embodied cognitive processes and biophysical environments. Accordingly, primacy is given to the practical: Participants are involved in goal setting and co-creating locally salient systems knowledge, as well as in the iterative development of methods based on feedback. The role of researchers in transformative science is to design spaces and processes for participatory inquiry, for example in the form of a series of interviews and workshops with stakeholders, assuming responsibility for the moderation of the exchanges, documentation and presentations to encourage reflection drawing in insights from diverse disciplines and practice (König et al., 2021; Vienni-Battista and Klein 2023). Both problem-oriented dialogue and reflection on mutual causality in complex social-ecological-technological systems are considered intrinsically valuable and a suitable basis for planning and implementing concerted action on sustainability challenges in diverse groups. All interactions with participants were conducted according to current codes of conduct for ethical and responsible research. The project’s participatory process to co-create the scenarios distinguished three main phases (See

Table 1).

3.1. Phase I: Multi-Level Engagement

The first action by the research team was to set up a ‘Project Reference Group’ charged with defining the main project objectives, identifying salient research questions and stakeholders, and contributing to the interviews. In subsequent stages the group was consulted on workshops, strategic decisions, and draft texts. The fifteen members of the project reference group were chosen strategically both to represent different professions with different framings of the situation of water quality management in Luxembourg and to represent different levels of governance. Members included a ministerial official, the co-director of a national public authority, as well as municipal actors and non-governmental organisations and farmers, and representatives of three of the five river partnerships. The local actors included people who had instituted pioneering projects such as river restoration projects and the introduction of new fertilizer application approaches in Luxembourg. A Scientific Advisory Board with four international experts was set up and met twice to provide advice on salient cutting-edge theory and methods, and to develop quality criteria and a quality control process for these transdisciplinary projects that value place-based knowledge as well as academic concepts and methods.

Over 50 stakeholders were interviewed between February 2017 and May 2018, including regulators, administrators national and local governments, informal organizational actors such as the river partnerships, consultants, teachers, forestry, nature protection as well as users in the private sector and in private households and organized civil society. Focal questions in the analysis concerned uncertainties, contradictions, value conflicts and tensions. A semi-open interview questionnaire was developed in consultation with the Reference Group and refined through pilot interviews. Thirteen overarching themes to start the collaborative orientation process were identified. For the interpretation of interviews, the ‘chorus of voices’ (Ramirez and Wilkinson 2016) method was used. This approach refers to capturing quotes from interview material and collating them in such a way that it foregrounds differences of view. For each theme, a range of quotes was selected to highlight tensions and contradictions as well as common points of agreement.

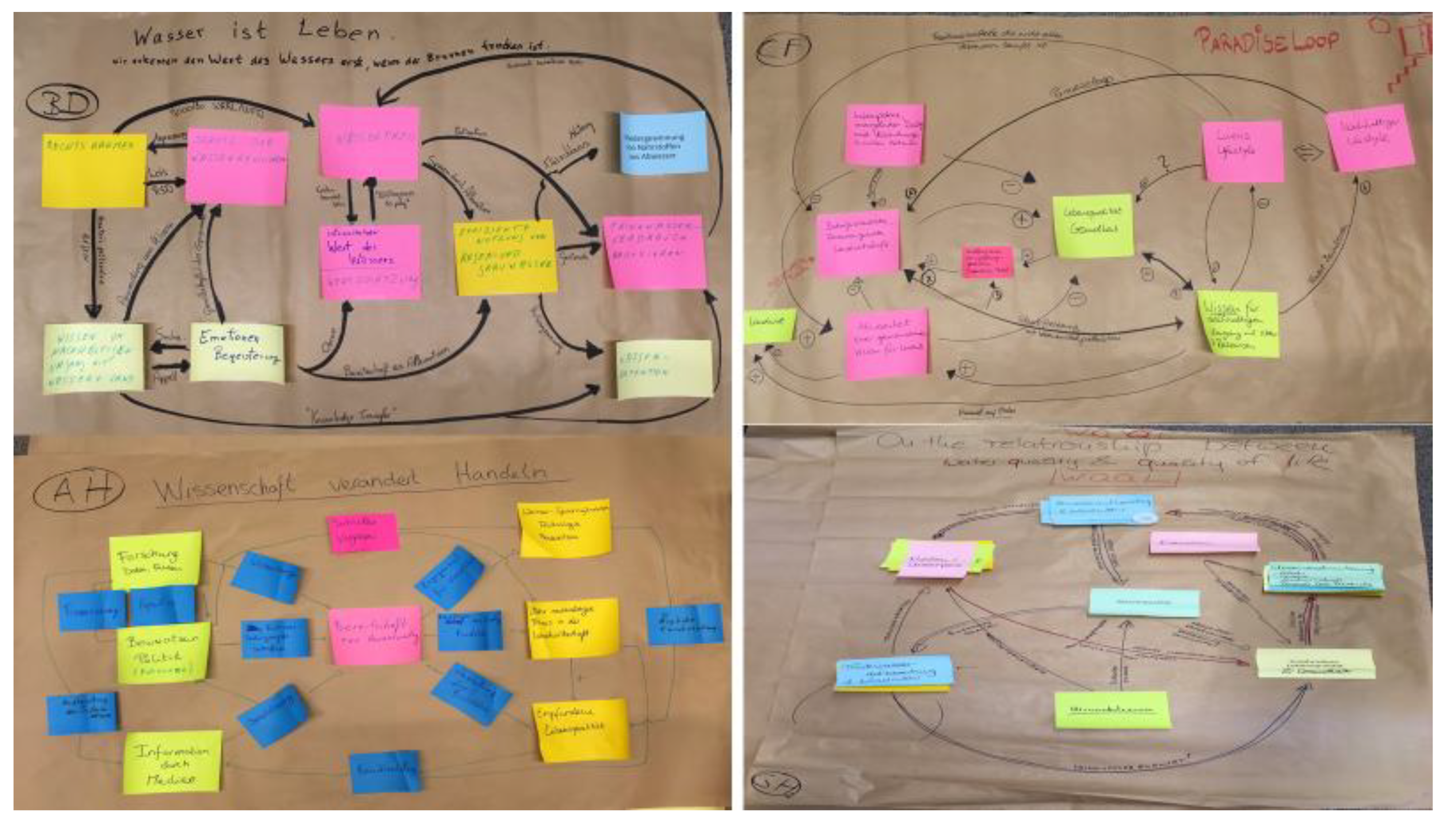

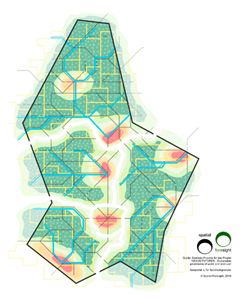

Throughout the project a total of three dedicated scenario development workshops with 40 to 50 participants from diverse organisations were organized. Participants attended from public agencies involved in water and forest management and agricultural advice, actors from river partnerships, municipalities, and the farming communities, as well as environmental NGOs and intergovernmental actors. We collected participant feedback after each workshop. The broader participatory phase of the scenario development started with a two-day workshop in June 2018, at which over 53 stakeholders created the basis for three different worlds, each highlighting future challenges and opportunities. We discussed diverse viewpoints from the interviews and amongst workshop attendees with respect to water and land and identified drivers of change and used the method of collaborative conceptual systems mapping adapted from Newell and Proust (2018) to identify main interactions and interdependencies between drivers of change (see

Figure 2. in

Section 4 below).

A significant share of the interviews and three additional workshops that informed the scenario approach was conducted as part of a narrative research approach to better understand factors helping or hindering the adoption of participatory governance approaches in two river catchment areas). The study found that conflicting framings of problem situations with respect to water quality and promising measures to improve it were associated with different organisations and professions (farmers, public authorities, municipalities, drinking water providers or environmental NGOs) who were engaged in the governance processes.

3.2. Phase II: Co-Creating Ontologically Differentiated Scenarios

A second workshop in November 2018 started with discussions on toxic assumptions and uncertainties in relation to our engagement with water and land in the face of potential impacts of climate change, population and economic growth. A world café approach was used to explore how different uncertain factors may play out differently at different governance levels (local/municipal; national/regional and EU). In the workshop we staged an art exhibition that featured caricatures and other works depicting human-environment interactions highlighting tensions and challenging prevailing assumptions (works of this exhibition were published as a book). Furthermore, the artist captured salient dialogues in a second painting.

On this basis we proceeded to drawing up micro-narratives with methods for an ‘inductive’ creation of short story logics, each short story bringing together a small subset of key elements and their interactions (Kurtz et al. 2014; Mosier and Fischer 2010). Six groups with four to five participants were asked to select and relate four to five uncertain factor cards to each other, and then to give their story a title. Each group was asked to create at least three micro-narratives, each time with a different leader to ensure a more level playing field. Within two hours, a total of eighteen diagrams were created by six groups, of which eight diagrams were presented in plenary, presentations were recorded transcribed.

The research team compared, grouped and analysed the results based on the three different forms of presentation of the micro-narratives: Diagrams, Templates, and Transcripts. Seventeen of these ‘micro-narratives were then grouped into three main clusters, which were the basic scaffolds for the three narrative frameworks and the differentiation of the scenario’s narratives according to the archetypal ontological assumptions (see

Table 2). The eighteenth micronarrative presented a dystopia of an accident at the nuclear power station Cattenom on the border to Luxembourg, which wiped out a large part of the population and the rest left the contaminated territory and founded a Luxembourg diaspora in Iceland. Whilst an important opening to ‘possible futures’, disagreements on the significance of this micronarrative led to it being cast aside.

3.3. Phase III: Situating and Bounding the Scenarios

A workshop in January 2019 served to challenge and further elaborate the proposed scenario meta-narratives. Subsequently the research team commissioned five experts to contribute quantitative and qualitative studies, exploring different aspects and implications of the three scenarios in more detail. A quantitative study by XXXX provided plausible modelled ranges for frequency of occurrence of extreme weather events and seasonal distributions of temperatures and rainfall that served as basis to differentiate the climatic conditions in the three scenarios. A second quantitative study by XXXX concerned water demand and supply. This study suggests that water will become a primary constraining factor for population growth and economic development at the latest in 2030 in spite a large new installation for water treatment of the lake water in the North of Luxembourg. Based on this modelling approach, three different scenarios for water use and sourcing systems have been developed. XXXX addressed possible implications of the three meta-narratives concerning land use and the overall spatial organisation of Luxembourg. Contradictions in terms of multiple competing land uses on certain areas of the country were resolved into three scenarios with different underlying logics for spatial organisation. XXXX developed three differentiated scenarios for implementing the circular economy. XXXX provided studies on the legal and historical context of water governance with a focus on governance and public participation.

In parallel, three co-author teams worked on detailing the scenario narratives. This involved identifying relevant seed projects and plausible stories set in the future to which readers can relate. In addition to desktop research, they drew on all materials from the co-design process. Specific barriers to transformations for sustainability and trade-offs that are associated with each of the three archetypal narratives were also effectively revealed in the expert contributions and by the scenario author teams. This was only one part of the situating of the scenarios. In each application described below the ontologically differentiated scenario set and the way they were used were further adapted to specific situations and places.

All detailed expert reports and scenario working papers and further resources and materials produced throughout the scenario process can be downloaded from the following website: XXXXX. Whilst the project had two working languages, German and English, most reports are in English.

4. Results—The NEXUS FUTURES Scenarios- an Ontologically Differentiated Scenario Set

Apart from viewing the path as the goal like Mahatma Ghandi, this three-phase scenario process resulted in a set of possible and very different scenarios. This set makes explicit ontological plurality amongst the participants, foregrounds associated assumptions about human agency in societal transformation processes and reflects the high level of complexity of and key feedback loops within the social-ecological water-land systems from which problematic patterns of behaviour emerge (

Figure 2). Whilst the three scenario narratives that are differentiated across five main drivers portray differences across multiple scales and are oriented as reference points across a longer temporal scale of several decades, they can also serve as scaffolds for the exploration of relevant cross-scale interactions and their short-term implications in more situated negotiations about what matters in respect to place-based regenerative actions. Two of the scenarios include selective aspirational elements for discussion, and the set builds on two quantitative studies. Surveys completed by participants after all workshops and the repeated return of many of the participants suggest that the scenario practice achieved triggering ‘AHA moments’ required for transformative learning and changes in perspectives.

Break out groups with 4-6 participants developed influence diagrams in dialogues about which factors affect how we engage with water and land, looking at factors from the social, ecological, technological and personal spheres. Factors are entities that can increase or decrease. Influences between arrows are processes or activities (biophysical or social) through which the influences that are easily intuitively grasped are manifested. The method is adapted from Newell and Proust (2018).

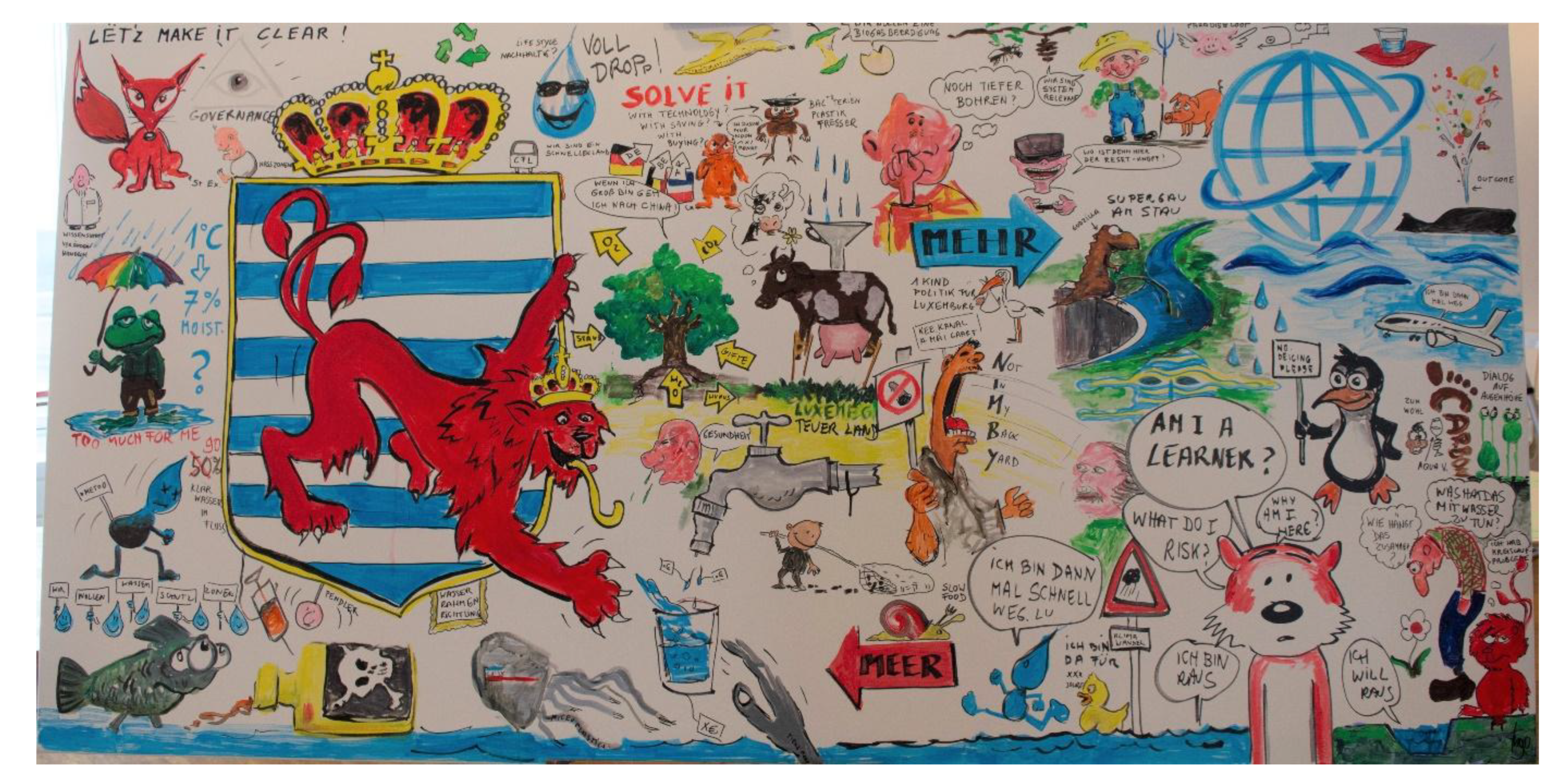

Furthermore, during the workshop an artist illustrated main points in the dialogues, challenging prevailing social norms and highlighting contradictions in the workshops deliberations with caricatures (

Figure 3) in support of stimulating questioning of our systems of meaning-making and subverting prevailing ways of directing attention and resources (Vervoort et al., 2024).

The artist Ingo Schandler captured tensions, contradictions and critical perspectives regarding prevailing social norms throughout the workshop. Participants in breaks gathered around the 3mx1.50m painting and reflected his work. © Ingo Schandler

In this section we first present the scenario set with its ontologically differentiated story lines. Secondly, we discuss the expert contribution on spatial planning as example how this differentiation helped the experts to develop a set of territorial master plans that clearly illustrate trade-offs between giving primacy to specific logics and principles in spatial planning. Thereafter we discuss the use the scenario set in two situations: in a virtual workshop with municipalities during the first lock-down of the pandemic in 2020, and in the context of a multi-stakeholder workshop with a strong contingent of scientific researchers on the co-design of a Greenbelt around the city of Luxembourg.

4.1. The Ontological Differentiation

From the interviews and workshops, but also in particular from the inductive micronarrative activity emerged three metanarratives that could be associated with a prevailing ontology and a suitable constitutive metaphor set (see

Table 3).

In the scenario ‘Smart Sustainability’, an objectivist understanding of our world prevails. Objectivism starts from the premise that objects have properties independent from people or other sentient beings who experience them. We understand the world in categories and concepts that correspond to properties that objects inherently have. In such a world view, words have fixed meanings, independent from the context they are used in that allow us to describe a reality correctly (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, p. 186). In this scenario, knowledge is power, and science provides control over nature. Planetary boundaries to human actions are recognised as potential biophysical tipping points of the earth system (Rockström et al., 2009). Governments and corporate actors are called upon to act in unison to keep to these limits. Progress, including to combat climate change is strongly associated with technological developments and economic growth is an important societal goal, as depicted in a coherent set of six micronarratives with titles such as ‘Growth: Origins and consequences’; ‘Flood prevention for dummies’; ‘Technology as instrument’.

In the scenario ‘Common Good and Knowledge’, a subjectivist understanding of the world prevails. Subjectivism assumes that meaning is always to a person and depends on rational knowledges as well as experiences, feelings, values and intuitive insights (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p.187). It seeks to overcome alienation from viewing man as separate from his environment from objectivism by embracing individual feelings and using ones senses to appreciate nature. Planetary boundaries are conceived in terms of both biophysical limits and a social foundation that is required to leave no one behind in the strife for sustainable lifestyles (Raworth, 2016). Humans are no longer considered just rational utilitarian actors, but capable of organising for reciprocity in social communities. Progress in this world is associated with improvements in human well-being and good governance, as suggested by five micronarratives with titles such as ‘Responsibilities associated with health’, and ‘On the edge: each opinion counts’.

Grounded in an experientialist understanding of the world, in the scenario ‘A Web of Life’, truth is relative to our conceptual system which is grounded in and constantly tested by our experiences in our interactions with other people and our physical and cultural environment. We understand the world through our interactions with it. Humans are seen as an integral part of the environments they live in and constantly interact with – we shape our environments according to our concepts and intentions, and our environment shapes us (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, p. 229). Planetary boundaries are described in terms of optimising mutually beneficial influences across different life forms who share agency in co-constituting the biosphere (Rupprecht et al., 2022).

The resulting set of three scenarios offers a new systemic framework for future-oriented deliberations that helps to reveal ontological plurality in diverse interest groups and professions. It is derived from and thus most relevant to the cultural setting of Luxembourg. The scenario set shows how sets of different values relating to efficiency, the common good, or our relationship to nature can orient us to alternative futures. These values can provide a direction for innovation and the allocation of resources and attention, because they shape collective and individual ideas about ‘progress’ and ‘the good life’ that in turn shape the intentions and actions of individual citizens, organisations and professions. The ontological differentiation and set of metaphors used to describe the human-environment relations and different notions of the role of humans within these are similar surprisingly similar to those described by Raymond et al. (2013). The archetypal character of this scenario set can be however easily contested, as of course such ontological differentiation comes with gross oversimplification. Moreover, the participants in the Luxembourg scenario process – decision-makers, opinion leaders and environmental activists and farmers whilst professionally and educationally diverse are culturally a somewhat homogenous group – for example there were no non-Western viewpoints represented. Still – of relevance for highly Westernised setting, there are interesting similarities to Nature Futures Framework (NFF), a set of three scenarios developed in parallel without our knowledge at the fringes of meetings of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (Pereira et al., 2020). The NFF was also developed as transformative multi-scale set of scenarios. The quality of attending to indigenous voices in this process was however debated. This set of scenarios is developed to capture diverse positive relationships of human with nature, the scenarios are therefore more akin to different visions, intended as action framework. The process and underlying narratives of the scenarios have not made explicit possible divergent ontologies of different participants, and the process was not designed in view of the need for reflexivity on disparate assumptions of ‘what matters most’ in changing human-ecological relations.

4.2. Three Different Understandings of Space and Their Consequences for Planning

In the process of detailing the scenarios with inputs from different experts, on the circular economy, water systems, spatial planning, and on climate change, working within three different ontologies helped each of the experts to develop three differentiated contributions on what the future might hold for their sector. Each contribution suggested different understandings of human agency, prevailing values and social norms, and practices, associated with different sets of design criteria for technologies and infrastructures and social structures (such as welfare or pricing systems). Moreover, each scenario offered different potential seeds of change in terms of promising innovations (social or technological), and different ways in which these would play out in the respective scenario.

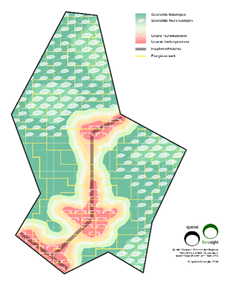

This summary of content and representations of the three scenarios focuses on the contribution on spatial planning (see

Table 4). Development of the three scenarios built on insights in the evolving field of territorial foresight applying territorial impact assessment techniques to future trends (e.g., Böhme et al. 2020).

The scenarios illustrate different spatial developments in terms of an emphasis on globalization, regionalization, or national organisation, highlighting differences in social coordination and distribution of power and voice. Moreover, the spatial planning dimension and differentiated planning principles illustrates that there are fundamental differences in scope for action by disparate actor groups at different levels of governance. The territorial master plans also highlight trade-offs and different areas of tension between developments in society, technology and the environment that play out in very different ways: For example, pressures on ecosystems and land in general, regional/municipal autonomy, distributive justice. For a more comprehensive summary of each scenario see

Appendix A. For detailed reports on each scenario and all workshops, please follow this link XXXX.

4.3. Municipal Climate Adaptation Plans

An early version of the resulting scenario set was used in a virtual workshop with municipalities in Luxembourg during the COVID pandemics’ second lockdown phase on adaptation and mitigation of climate change on 9.12.2020.

Framing of process and situation: The objective of the workshop was to provide a platform to discuss possibilities for municipal climate change adaptation plans. The fifteen participants included staff from ministries, administrations, and municipalities.

Scenario contents and characterisation: The NEXUS FUTURES scenarios were presented at the start of the workshop to present shared reference points in the future as basis for dialogues between technical staff, implementation oriented, and strategy-oriented participants. Additional handouts with emphasis on the differentiated spatial planning approaches were provided and participants were grouped in break-out groups discussing one of the scenarios as reference frame.

Rooting the scenarios in place-based considerations: Reference to the scenarios as a safe space in the future, usual patterns of thought seemed to be extended, if not disrupted. Some individuals were prepared to stick their necks out on what may be thinkable and doable further than was observed in more conventional settings to discuss climate change adaptation: for example talking about larger investments in river renaturation projects for flood control, or in urban gardening for enhanced food security, or larger municipal PV installations and car sharing facilities was ‘normalised’ with reference to the narratives of future impacts of climate change. It was notable that discussions in all groups centred around ‘low hanging fruit’ as opposed to more complex or strategic measures. Whilst the different ontologies / belief systems of the scenarios were to some extent reflected in different logics to propose actions in the different break out groups, taken together, the different actions by the three groups also helped to illustrate trade-offs between prioritisation of different courses of action. These complementarities were not discussed in detail. There was a lack of time and the virtual format was not conducive to asking more personal follow-up questions to participants about their assumptions.

Evaluation: Four completed evaluation questionnaires after the workshop suggested that the urgency and need for transformative action is clarified through the scenarios. The workshop received good ratings in a survey of participants and positive informal feedback after the event, also in comparison to other Workshops.

One lesson of the workshop was the need for improved ways to convey the scenario set with time for reflection before a multi-stakeholder workshop. For ease of communication and work with the scenario set an animated video was developed with a team of German journalists with expertise in science and environmental communication. YouTube link: XXXX (provides indications on authors).

4.4. The Greenbelt Luxembourg Project

Process and its situation: The scenarios were deployed as part of a project on designing a Greenbelt around the capital to improve climate resilience in terms of fostering water security and quality, food sovereignty and optimized microclimates. The four-hour workshop was situated in one of the focal areas on an industrial site, a former steel production centre, next to the river Alzette that flows through the capital. Twenty-seven participants included architects and planners, experts on aquatic pollution management, climate and air flow modelling, remediation of industrial sites, architects, planners, ministerial officials from the ministerial and departments of the environment and spatial planning, experts on complex social-ecological systems and transformation, representatives of NGOs, and private consultants active in relevant areas. To provide an experiential anchor and reference point for subsequent groupwork, participants then took a reflective walk on the site along the river Alzette, being invited to first focus on sensory experience and then reflect on impressions.

What matters/ framing: Design goals of the Greenbelt project include the development of place-based regenerative initiatives to secure clean, cool air flows into denser settlements and the city, as well as enhancing the functions of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in view of flood prevention, water retention, and water quality and pollution management. Biodiversity corridors to enhance health and resilience of these ecosystems are central to both these design goals. The main objective of the workshop was to gather expert and local place-based knowledge to identify concrete needs and potential seed projects for the Greenbelt at large and in three focal areas.

Content and scaffolding: Participants received a link with the scenario video ten days in advance of the workshop. About 40% of participants claimed to have watched all or most of it (this was relatively low; in other workshops this proportion was closer to 90%). In a plenary activity to consider open futures we briefly introduced selected aspects of the scenarios with a focus on their spatial dimension. On this basis we brainstormed on drivers of change that will impact the development of Luxembourg city and its surroundings. It was noteworthy how far reaching many of the drivers listed were, including war, social instabilities, artificial intelligence, and extreme weather events; two participants referred to the scenarios for legitimacy of including less immediate concerns. Uncertainties about what the area around the capital might look like in 2045 were discussed. Three break-out groups then worked with templates to brainstorm on needs for regeneration and developed one or two ideas in more detail using a collaborative conceptual system mapping approach (Newell and Proust 2018). Relevant maps from the Greenbelt project were available to all groups (insert website before publication – XXXX).

Outcomes - Break-outgroup presentations: In two out of three groups the scientific experts in modelling asserted their authority and focused the proposals on the need for funding integrated modelling for evidence-based priority setting for the selection of places for regenerative initiatives. A range of specific place-based projects had been considered, but had been dismissed, as they were perceived as too contested and fraught with barriers. Therefore, experts in modelling proposed that associated decision-aid tools should be developed that can compute and make visible complex information relating to the likely effectiveness of investments in river restoration, constructed wetlands and planting trees for cool air flows and pollution management. It was also interesting how quickly the consideration of developing more specific place-based project proposals was closed down in all three break-out groups. The situation of this workshop in an ‘extreme site’ in terms of a polluted former steel production area site might have pronounced barriers to place-based action rather than make such projects seem ‘low hanging fruit’.

The biodiversity group emphasised the need for a national plan for a strategic ecological meshwork with corridors that can connect diverse species populations for genetic diversity. This would include woody lines, buzz lines for insects, and fishlines across urban and rural areas, as outlined in the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law. This plan would provide a reference for spatial planning at the national and municipal level. More detailed planning and implementation should rely on participatory processes to make calls to private owners of relevant land parcels to collaborate on making keystone species relevant connections. Social coordination across the national, municipal levels and private owners was also considered challenging.

Outcomes - Plenary Discussion: During the plenary in response to presentations by two the first two working groups who emphasized computer model-based decision-making, representatives from the NGOs and the social-ecological research groups voiced concerns about purely scientific expert-driven decision-making. They highlighted the democratic deficit in this approach, which often leads to challenges in or lack of implementation through local actors.

The facilitator could refer to the three scenarios and highlight that greater ‘social robustness’ can be achieved with measures that perform well across all three scenarios: the Smart Sustainability world in which AI has authority, the Common Good scenario in which participative decision-making is required at the local level for legitimation of decisions, and the Web of Life scenario in which such decisions rely on co-created data pools including with citizen science that include actors across different governance levels. Furthermore, examples of challenges in the reception and implementation of new water protection zones, largely relying on recommendations from a team of engineers and hydrologists from Germany (Hondrila 2021) could be pointed to, to highlight the lack of local acceptance and limitations to implementation from purely modelling-based proposals for regenerative initiatives. Accordingly, with reference to the scenarios, the facilitator could invite some of the experts to switch from a first focus on ‘data-driven’ decision making based on a positivist world view to open up to other requirements of more complex realities of complex situated decision-processes with diverse stakeholder groups who might view and evaluate data sets and their representations differently. An integrated approach could then be proposed by the facilitator that relies on some modelling but also addresses the democratic deficit by engaging actors to collaborate across governance levels and draw in scientific and place-based knowledge. This led to the proposal by an NGO member that such modelling and decision tools should be publicly accessible and provide windows of accountability on land-use change. The workshop concluded with reflections on how regenerative action for climate resilient development for the public good will increasingly have implications for municipal and private decision making on land use and land cover change. Further analysis and a resulting summary with recommendations were circulated to participants for comments before submission to the ministry who had commissioned the study.

4.5. Merits and Limitations of Applying the Scenarios

These outcomes also echo other researchers experiences in which it was noted that dominant narratives and purely ‘science-based’ narratives focusing on quantification as opposed to opening different participatory approaches to the issues were difficult to question. In short workshops there was insufficient time to discuss the inherently restrictive nature of underlying assumptions (Galafassi et al. 2018). The scenario set allowed the facilitator to more easily leverage and make explicit different narrative logics and different types of knowledge production systems to propose an integrated and arguably more socially robust solution. This situation proved similar to urban planning workshops described by Quick (2021), in which prior narrative analysis also helped the facilitator in proposing acceptable new frames for concerted action across groups defending different interests.

The main challenges and limitations in both workshops were linked a lack of time for consideration of deeper implications of different ontologies and opening spaces for exploring underlying assumptions of prevailing paradigms and the potential role of stories in revealing axiology of paradigms and in generating shared meanings from which new paradigms may emerge. One way to stimulate interest in dedicating the required time and resources for more profound engagement in such participatory workshops could include capacity building efforts that engage actors across different governance levels in courses on future-oriented systems thinking. Such courses could for example be made part of obligatory training for civil servants or any staff employed in publicly funded projects and ventures (see also Ferrone et al. 2023). Specifically, capacity building approaches with diverse actor groups have been highlighted as having potential to create a more level playing field across diverse actor groups active at different governance levels and with different types of knowledge at the science-policy practice interface (Turnhout et al. 2016; Perrings et al. 2011), promising conditions to engage in critical reflection on prevailing paradigms, potential incongruencies across them, and offering opportunities for transcending these and developing new ones. It will be helpful to distinguish between capacity building for transcending paradigms and for developing proposals for concerted action with more practiced participants.

To achieve wider transformations across space and time, transformative governance processes would require means for connecting multiple place-based regenerative interventions over time and space, such that they can be evaluated in terms of their ontological agency and social performativity. Linking engagement activities and ‘projects’ across spatial and time scales such that they can be considered part of a social learning process promises to create a mutually reinforcing dynamic for regeneration. Such a multi-level approach would bear some similarity to work and proposals by Raudsepp-Hearne 2020) in terms of approaching the need to link processes and actors across different governance levels and spatial scales. The literature of living labs and transformation labs is relevant for further development of such more comprehensive procedural approaches over time and space (McRory et al. 2020).

5. Conclusion and Outlook

Transformations to regenerative societies have been recognized as deeply ontological in nature (Maggs and Robinson 2020; Escobar, 2018; Latour, 2018; Stengers, 2010). Polarization between those who seek to modernize, place primacy on technological innovation and science-based reasoning in a way that is often associated with neo liberalism and globalization, and those who are reactionary and pursue autarchy at regional or local scales cause detrimental inertia (Latour 2018). Many of these dominant assumptions reflect past realities, that no longer apply to the present or future circumstances. The shift from both these viewpoints to a new appreciation for place that considers ecological and human health as inseparable requires a shift to a new understanding of our world as a web of interdependence mutual causality between what we wish to know, and the effects of our actions demands a level of ontological reflexivity that has hitherto never been asked of humanity.

In a time of increasing social and ecological instabilities and ever more disruptive technologies the design of future-oriented and systemic approaches to social coordination that provide a foundation for new paradigms and invite widespread engagement in regenerative action is becoming ever more urgent. Political measures developed in compartmentalised policy settings or silos, often lack sufficiently structured knowledge to inform future-oriented regenerative actions that must be meaningful when considered in a place-based or situated manner. Approaches and practices that enable collaboration across differences resulting in recommendations that transcend prevailing framings and ontologies, with respect to the role of science in informing policies and place-based actions are needed. Accordingly, we need to become more proficient in diverse groups to take free flowing information on complex situations and developments and transform this into coherent systemic concepts and frameworks which then can serve to deliberate on shared stakes and focalize concerted place-based action. And, in the face of such complexity and ontological plurality it is needful to embed action in a territory, otherwise meaning is easily lost. We also need inspirational goals (not some abstract and potentially misleading promise that net zero emissions will lead to climate stabilisation), if we wish to effectively engage such diverse actor groups in an ontological shift and a new purpose (Robinson and Cole, 2015).

To address these challenges, this paper advances the concept of regenerative governance and a purposefully designed scenario approach with an axiology aligned with a multi-species sustainability ethics (Rupprecht et al. 2022) highlighting human responsibilities towards the web of all living species. Regenerative governance is conceived as a novel form of social coordination for pluralist societies, that is decentralized to better cope with place-based complexities, whilst also being well-connected across governance levels to allow for mutual learning across diverse landscapes, social groups, and levels of social organisation. The resulting purposeful inherent tension in the proposed governance approach - between the goal to be explicitly supportive of ontological pluralism and a strong normative axiology of a multi-species sustainability ethics provides a creative space that invites reframing current thinking and doing by all who engage in it.

The seven design attributes for scenario approaches in support of regenerative governance aim to improve social coordination for regenerative action across adequate spatial scales (see

Figure 1). Intended outcomes include transformative learning experiences of participants as well as transformative and regenerative scenarios that complement prevailing patterns in current scenario practice. Such scenario sets can make explicit ontological plurality amongst the participants and foreground associated assumptions about human agency in societal transformation processes (

Figure 2). Scenarios can also be designed as scaffolds to facilitate the exploration of relevant cross-scale interactions and their short-term implications in more situated negotiations about what matters in respect to place-based regenerative actions. Moreover, scenarios can include both selective aspirational elements for discussion, as well as quantitative studies and empirical observations that seek to bridge human sensory awareness with aspirations in relation to better living in alignment with nature’s processes. The procedural design attributes were proven and refined in a multi-level scenario approach implemented in Luxembourg.

A first set of ontologically differentiated outlines of scenarios helped experts engage with different but coherent sets of understandings and prevailing values when proposing accordingly differentiated plausible futures for their expert domain. In using the scenario set in different workshop situations to date, time was usually short and prevented using the scenario set to their full potential to foster ontological switching amongst workshop participants. A full day workshop would be required. Accordingly, there was no in-depth dialogue on different world views and underlying assumptions in the scenarios. However, reference to the scenario set helped to reconcile alternative understandings of the roles of science and local actors in spatial planning by proposing an integrated and transparent participatory planning process with open data and publicly accessible modelling results.

Further research should explore the possibility for using such scenario approaches for the purpose of capacity building in systems and future-oriented deliberations for regenerative actions and at the same time better connecting actors from across different governance levels, and to foster ontological reflexivity more broadly across different groups in society. One other challenge to associated transformative and transdisciplinary research that seeks to stimulate social learning will be to develop compelling frameworks to assess and evaluate the capacity for ontological reflexivity in engaged individuals and organisations, as well as the social performativity of the scenario approaches and impacts from engagement in such scenario practice over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ariane König (scenario approach and its ontological differentiation), Kai Böhme (differentiation of the three scenarios for the purpose of spatial planning), Kristina Hondrila (engage perspectives from river basin organisations). Formal analysis, Ariane König, Kristina Hondrila and Isabel Sebastian; Funding acquisition, Ariane König; Investigation, Kristina Hondrila, Maria Toptsidou; Methodology, Kai Böhme, Kristina Hondrila and Isabel Sebastian, Ariane König; Supervision, Ariane König and Kai Böhme; Visualization, Ariane König, Kai Böhme and Sebastian Hans; Writing – original draft, Ariane König; Writing – review & editing, Ariane König, Kai Böhme, Sebastian Hans, Kristina Hondrila, Maximilian Klein, Isabel Sebastian and Maria Toptsidou. Project Administration: Andrea Klein. Funding Acquisition: Ariane König.

Funding Sources and Other Acknowledgements

The NEXUS FUTURES project was co-funded by the Ministry for Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development and the University of Luxembourg. The AGGLO CENTRE Project was funded by the Ministry of Energy and Spatial Planning of Luxembourg. We are grateful to all stakeholders across Luxembourg, who gave their time and expertise in interviews and workshops. We could not have completed the project without this engagement. We would also like to highlight the invaluable contributions made by Mr Ciaran McGinley, who sadly passed away shortly after the project ended. There is no conflict of interest with respect to the research goals, approach, or funding sources.

Data Availability Statement

Most data described in

Table 1 with an overview on the three phases of the scenario approach are available at a public website:

https://transformation-lab.lu/projekte/nexus-futures-szenarien/. This data includes one report with a detailed description of procedures and results of the main three dedicated scenario workshops, as well as all five expert contributions, and the detailed scenario documents developed by the scenario author teams. Data from the interviews and workshops in the form of recordings and transcripts are in German and are not made publicly available to protect the privacy of all who agreed to be recorded for the purpose of this research. Investigations were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)-Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, as well as guidelines on research integrity. A conditional approval was obtained from the ‘Ethics Review Panel of the University of Luxembourg’ then chaired by Prof. Dr Klaus Vögele on 6 November 2017. All requested modifications to the research approach were introduced and approved by the panel prior to conducting the research, ensuring that the study adheres to both national and international guidelines. Informed consent forms were completed by participants for all our interviews and workshops part of the NEXUS FUTURES research project. We also ensured participants gain returns of interest to them for their time investments by providing regular feedback and updates in the form of interim reports on all activities.

Appendix A. Summaries of the Three NEXUS FUTURES Narrative Scenarios

Smart Sustainability

The Smart Sustainability scenario is characterised by globally coordinated and rapidly advancing technological innovation. Prosperity is driven by economic growth and consumption. Online transaction taxes constitute the main source of public revenue. Around the world, economic and political interests function together like clockwork. They are the motor of a global economy that aims to reduce material flows and waste through technological innovation. Large multinational companies largely shape the fight against climate change themselves as a result of environmental rules and regulations such as emissions trading. Artificial intelligence and learning machines control a wide range of economic and social domains, subjecting them uncompromisingly to the dictates of efficiency. Amongst the 1.2 million inhabitants of Luxembourg, experts in energy, material flows and industrial design enjoy considerable influence. Amongst the rest of the population, convenience and dullness dominate. Inequality in incomes and opportunities are also growing rapidly, whilst the costs of water and food rise steadily. Resource-saving technologies are thus not available to everyone.

Smart spatial planning; Increasing population and economic activities are inexorably driving the construction of ever more homes, offices and industrial plants. The sealed land area is growing by 0.5 hectares per day; areas of housing and roads continue to expand, increasingly displacing forests and arable and undeveloped areas. Five ‘smart’ highly digitalised development centres, which are particularly important for economic development, have emerged. 432,000 people live there, that is 37% of the population. Access to high-speed internet varies greatly across geographical locations and is mainly concentrated in these centres. There are also ten other development centres, in which a further 30% of the population is concentrated. Most jobs and shops are also located in the cities, particularly in Luxembourg City. They are all close to the city, meaning that urban sprawl has increased greatly.

Engagement with water; Lxembourg’s ecosystems are more fragmented than anywhere else in Europe.