Submitted:

07 January 2024

Posted:

09 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. The Dual Ontology Conjecture and Synopsis

1.1. Introduction

- Reconciles fundamental issues in Special Relativity and quantum mechanics by explaining why all quantum states (a) dynamically evolve in 4D spacetime subject to the speed of light and (b) instantaneously collapse in a physical Planck Space that is not subject to Special Relativity.

- Holds that the temporal and physical asymmetry between the dynamic evolution of quantum states in a 4D spacetime governed by the speed of light and the collapse of all quantum states in a Planck Space where Special Relativity is inapplicable is the physical source of quantum path irreversibility and the arrow of time.

- Explains why, at or near 4D spacetime’s heat death, the instantaneous collapse of the energy content of Planck Space and the simultaneous transition of 4D spacetime's widely dispersed energy content to a non-singular, generally localized volume at t = 0 is the physical cause for 4D spacetime's isotropy, homogeneity, extremely high energy, pressure and temperature, flatness, and low gravitational entropy. The collapse process also explains the horizon and fine-tuning problems.

1.2. The Dual Ontology's Structure

1.3. The Dual Ontology and Quantum State Dynamics

1.4. Quantum Path Irreversibility

1.5. The Dual Ontology at t = 0 and Heat Death

1.5.1. 4D Spacetime at t = 0 and Heat Death

1.5.2. Planck Space at t = 0 and Heat Death

1.5.3. The Collapse of the Planck Energy Hyper-Point

1.5.4. The Horizon Problem and Causality

1.5.5. The Flatness Problem and Fine-Tuning

1.6. Analytical Structure

2. The Physical Structure of the Universe

2.1. The State of Absolute Nothingness

2.2. Planck Spheres, 4D Spacetime, and Planck Space

3. Quantum States and the Dual Ontology

3.1. Single Quantum States and 4D Spacetime

3.1.1. The Collapse of a Single Quantum State

3.1.2. The Einstein/de Broglie Box Thought Experiment

3.2. N-Body Quantum States

3.2.1. Evolution and Collapse of N-Body Quantum States

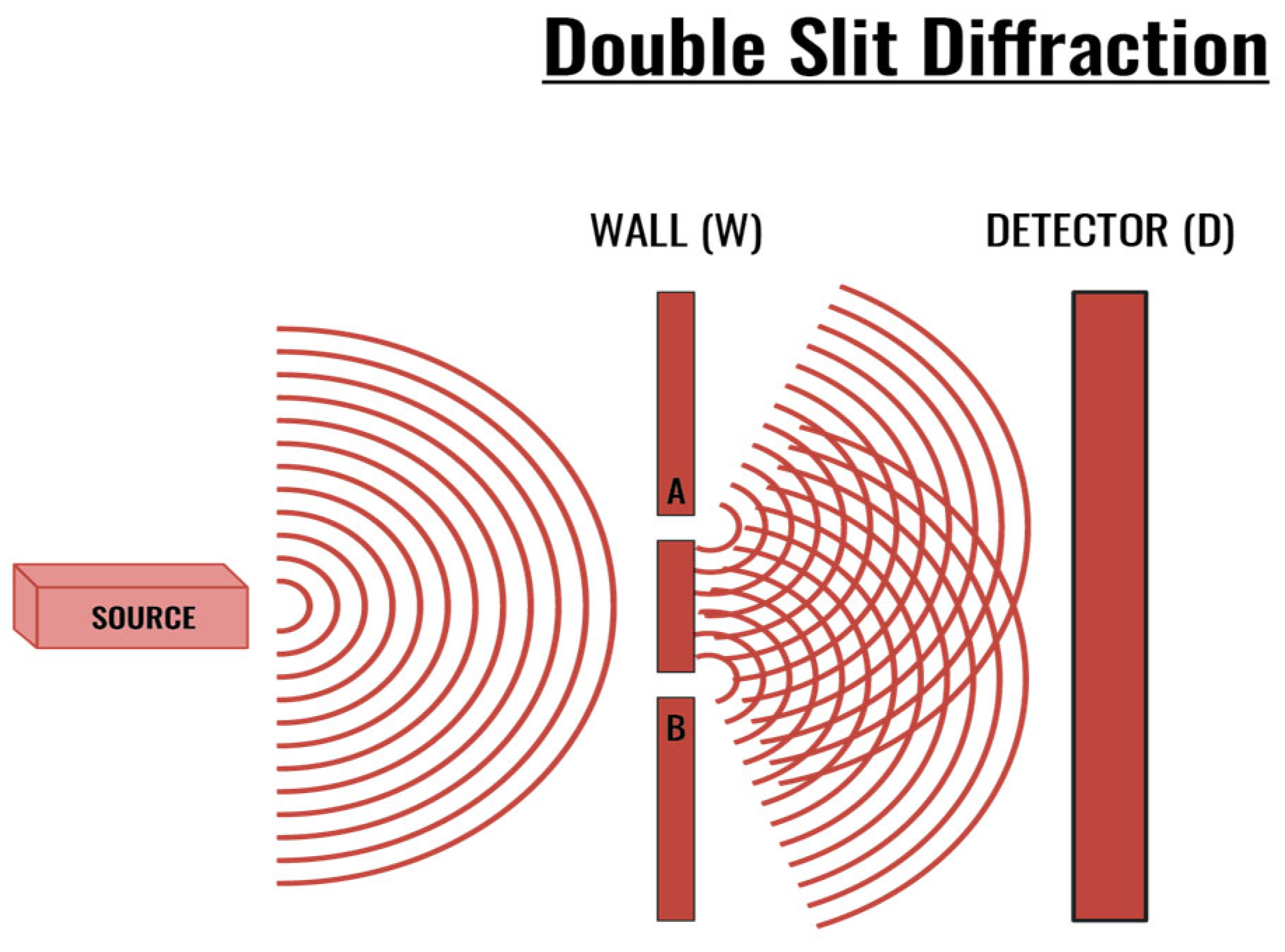

3.2.2. The Double-slit Experiment

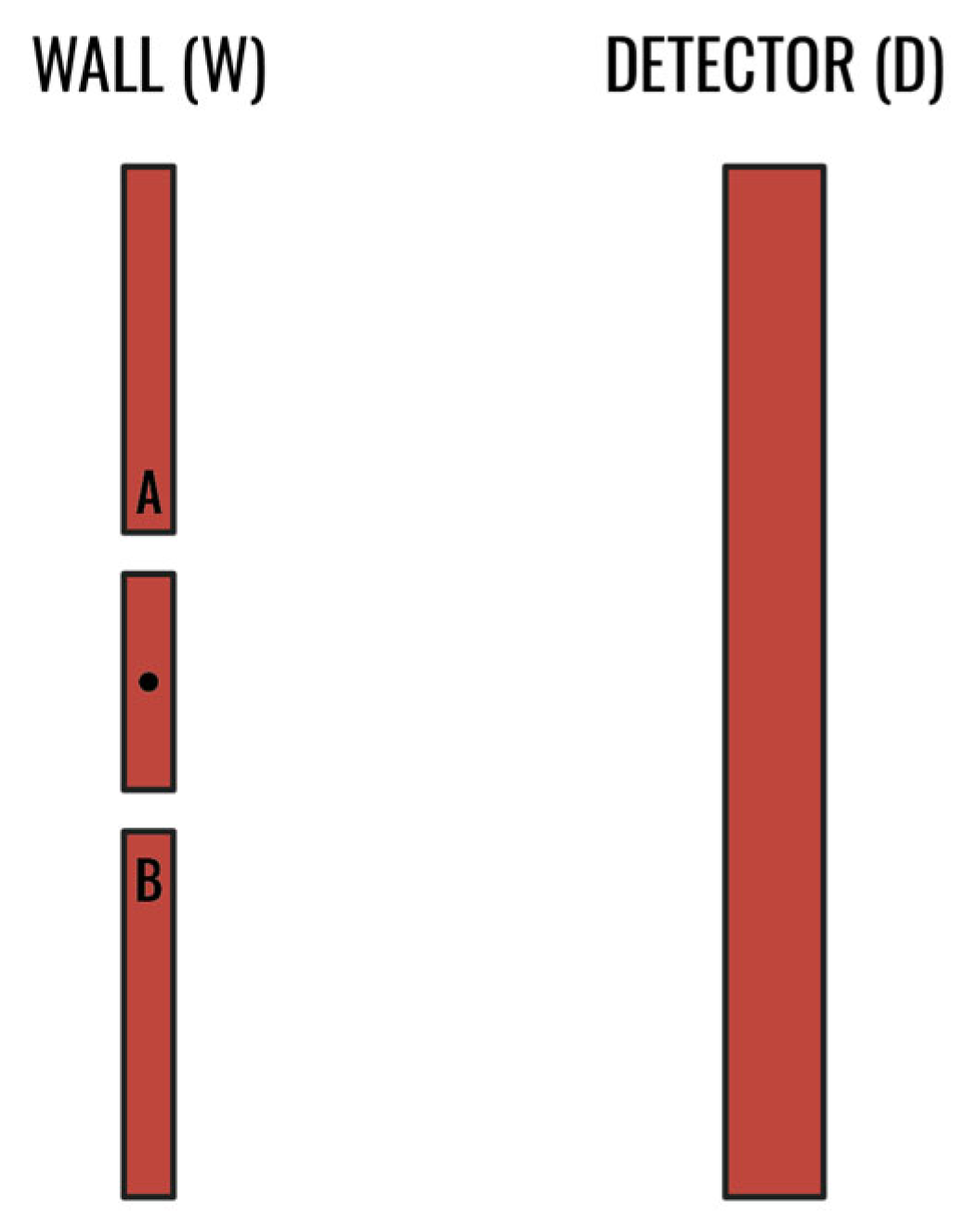

3.2.3. A Simple Which-Way Experiment

4. Physical Considerations

4.1. Indeterminacy and the Bell Quantum Hyper-Point

4.2. Quantum State Emergence and Annihilation

4.3. Physical Triggers

4.4. The Generalized Localization of a Quantum State

4.5. The Dual Ontology, Time, and Instantaneous Collapse

5. Special Relativity and Quantum Mechanics

5.1. Space-Like Separated

5.2. Non-separability

5.3. Instantaneous, Superluminal, and Faster than Light

5.4. The Quantum Connection

5.5. Locality, Bell's Theorem, and Bell Quantum Hyper-Points

5.6. The Relativity of Simultaneity

5.7. Relativistic Energy Increase

6. Quantum Path Irreversibility and The Arrow of Time

7. Quantum Cosmology, Cosmogony, and the Dual Ontology

7.1. 4D spacetime at t = 0 and Heat Death

7.2. Planck Space at t = 0 and Heat Death

7.3. Planck Energy Hyper-Point Collapse and t = 0

7.4. The Horizon Problem and Causality

7.5. The Flatness Problem and Fine-Tuning

8. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Adams, F. C. (2019). The degree of fine-tuning in our universe — and others. Physics Reports, 807, 1–111. [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N., et al. (2019). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.06209.

- Aerts, D. (1984). The missing elements of reality in the description of quantum mechanics of the EPR paradox situation. Helvetica Physica Acta, 57(4), 421–428.

- Albert, D. Z. (1992). Quantum mechanics and experience. Harvard University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1bzfptv.

- Albert, D. Z. (1996). Elementary quantum metaphysics. In J. T. Cushing, A. Fine, & S. Goldstein (Eds.), Bohmian Mechanics and Quantum Theory: an Appraisal 184, 277–284. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [CrossRef]

- Albert, D. Z. (2003). Time and chance. Harvard University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvjsf57g.

- Albert, D. Z., & Loewer, B. (1996). Tails of Schrodinger’s cat. In R. Clifton (Ed.), Perspectives on Quantum Reality: Non-relativistic, Relativistic, and Field-Theoretic (pp. 81–92). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-015-8656-6_7.

- Albert, D. Z., & Ney, A. (2013). The wave function: Essays on the metaphysics of quantum mechanics. Oxford University Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/ALBTWF.

- Albert, D., & Loewer, B. (1990). Wanted dead or alive: Two attempts to solve Schrödinger’s paradox. In PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association (pp. 277–285). University of Chicago Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/192710.

- Alberto, P., Das, S., & Vagenas, E. C. (2011). Relativistic particle in a three-dimensional box. Physics Letters A, 375(12), 1436–1440. [CrossRef]

- Allori, V. (2022). What is it like to be a relativistic GRW theory? Or: Quantum mechanics and relativity, still in conflict after all these years. Foundations of Physics, 52(4), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Allori, V. (2013a). On the metaphysics of quantum mechanics. In S. Lebihan (Ed.), Precis de la Philosophie de la Physique (pp. 116–151). Vuibert. https://philpapers.org/rec/ALLOTM-2.

- Allori, V. (2013b). Primitive ontology and the structure of fundamental physical theories. In A. Ney & D. Alberts (Eds.), The Wave Function: Essays on the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanic (pp. 58–75). Oxford University Press. https://philarchive.org/rec/ALLPOA.

- Allori, V. (2015). Primitive ontology in a nutshell. International Journal of Quantum Foundations, 1(3), 107–122. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/11651/.

- Allori, V. (2016). How to make sense of quantum mechanics: Fundamental physical theories and primitive ontology. PhilPapers. https://philpapers.org/rec/ALLQTM.

- Allori, V. (2020). Scientific realism without the wave-function: An example of naturalized quantum metaphysics. In S. French & J. Saatsi (Eds.), Scientific Realism and the Quantum (pp. 212–228). Oxford University Press. https://philarchive.org/rec/ALLSRW.

- Allori, V. (2022). Spontaneous localization theories. In G. Bacciagaluppi & O. Freire Jr. (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of the History of Interpretations and Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 1103–1134). Oxford University Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/ALLSLT-3.

- Allori, V., Bassi, A., Durr, D., & Zanghi, N. (2021). Do wave functions jump?: perspectives of the work of GianCarlo Ghirardi. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-46777-7.

- Allori, V., Goldstein, S., Tumulka, R., & Zanghi, N. (2008). On the common structure of Bohmian mechanics and the Ghirardi-Rimini-Weber theory. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 59(3), 353–389. [CrossRef]

- Allori, V., Goldstein, S., Tumulka, R., & Zanghi, N. (2010). Many worlds and Schrodinger’s first quantum theory. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 62(1), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A., & Barrau, A. (2015). Loop quantum cosmology: From pre-inflationary dynamics to observations. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 32(23), 234001. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A., & Sloan, D. A. (2011). Probability of inflation in loop quantum cosmology. General Relativity and Quantum Cosmology, 43(12), 3619–3655. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, F., & Loeb, A. (2021). Finely tuned models sacrifice explanatory depth. Foundations of Physics, 51(5), 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Bacciagaluppi, G., & Valentini, A. (2009). Quantum theory at the crossroads: Reconsidering the 1927 Solvay conference. ArXiv (Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0609184.

- Bahrami, M., Bassi, A., Donadi, S., Ferialdi, L., & León, G. (2015). Irreversibility and collapse models. In A. von Müller & T. Filk (Eds.), Re-Thinking Time at the Interface of Physics and Philosophy, (Vol. 4, pp. 125–146). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. J. (2009). Against field interpretations of quantum field theory. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 60(3), 585–609. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., Bera, S., & Singh, T. P. (2016). Quantum nonlocality and the end of classical spacetime. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 25(12), 1644005–1644005. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J. A. (2005). The preferred-basis problem and the quantum mechanics of everything. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 56(2), 199–220. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J. D. (2001). The book of nothing. Vintage. https://philpapers.org/rec/BARTBO-11.

- Bassi, A. (2009). Collapse models: Analysis of the free particle dynamics. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A. (2021). Philosophy of quantum mechanics: Dynamical collapse theories. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Physics. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A., & Ghirardi, G. (2003). Dynamical reduction models. Physics Reports, 379(5-6), 257–426. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A., Lochan, K., Satin, S., Singh, T. P., & Ulbricht, H. (2013). Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Reviews of Modern Physics, 85(2), 471–527. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A., & Ulbricht, H. (2014). Collapse models: From theoretical foundations to experimental verifications. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 504. [CrossRef]

- Becker, A. (2018). What is real? Basic Books.

- Bedingham, D. (2021). Collapse models, relativity, and discrete spacetime. In V. Allori, A. Bassi, D. Durr, & N. Zanghi (Eds.), Do Wave Functions Jump? Perspectives of the Work of GianCarlo Ghirardi (pp. 191–203). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bedingham, D. (2016). Collapse models and spacetime symmetries. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. (2004). Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics: collected papers on quantum philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, M., & Gao, S. (2016). Quantum nonlocality and reality: 50 years of Bell’s theorem. Cambridge University Press. about:blank.

- Belot, G. (2011). Quantum states for primitive ontologists. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 2(1), 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R. D., Dunkley, J., Frenk, C. S., Lahav, O., & Shapley, A. E . (2020). Coming of age of the standard model. Nature Astronomy, 4(2), 122–123. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. (1952a). Quantum theory. Prentice-Hall; Constable.

- Bohm, D. (1952b). A suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of “hidden” variables. I. Physical Review, 85(2), 166–179. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D., & Broglie, L. de. (2016). Causality and chance in modern physics. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Bohr, N., & Einstein, A. (1949). Discussion with Einstein on epistemological problems in atomic physics. Open Court Publishing Company. https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/dk/bohr.htm.

- Bojowald, M. (2008). Loop quantum cosmology. Living Reviews in Relativity, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Bojowald, M. (2015). Quantum cosmology: A review. Reports on Progress in Physics, 78(2). [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R. W. (2014). Did the universe emerge from nothing? Reductive vs. holistic cosmology. NeuroQuantology, 12(4), 424–454. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L., Finn, K., & Turok, N. (2018). CPT-symmetric universe. Physical Review Letters, 121(25). [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L., & Turok, N. (2022). Thermodynamic solution of the homogeneity, isotropy, and flatness puzzles (and a clue to the cosmological constant). ArXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, R. H., & Martin, J. (2013). Trans-Planckian issues for inflationary cosmology. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 30(11), 113001. [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, R., & Peter, P. (2017). Bouncing cosmologies: Progress and problems. Foundations of Physics, 47(6), 797–850. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, A. (2016). What do we mean when we ask “why is there something rather than nothing?” Erkenntnis, 81(6), 1305–1322. https://philarchive.org/rec/BREWDW.

- Bricmont, J. (2016). Making sense of quantum mechanics. Springer. https://philpapers.org/rec/BRIMSO.

- Brunner, N., Cavalcanti, D., Pironio, S., Scarani, V., & Wehner, S. (2014). Bell nonlocality. Reviews of Modern Physics, 86(2), 419–478. [CrossRef]

- Broglie, L. de. (1964). The current interpretation of wave mechanics. Elsevier Publishing Company.

- Callender, C. (2014). One world, one beable. Synthese, 192(10), 3153–3177. [CrossRef]

- Callender, C. (2020). Can we quarantine the quantum blight? In Scientific Realism and the Quantum (pp. 57–77). Oxford University Press. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/15450/.

- Callender, C. (2021). Quantum mechanics: Keeping it real? The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. [CrossRef]

- Calmet, X. (2008). On the precision of a length measurement. European Physical Journal C, 54(3), 501–505. [CrossRef]

- Calmet, X., Graesser, M., & Hsu, S. (2005). Minimum length from first principles. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 14(12), 2195–2199. [CrossRef]

- Carrol, S. M. (2019). Something deeply hidden: Quantum worlds and the emergence of spacetime. Dutton.

- Carroll, S. (2018, October 31). What is nothing? Vice Magazine Online. https://www.vice.com/en/article/vbk5va/what-is-nothing.

- Carroll, S. M. (2014). In what sense is the early universe fine-tuned? ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S. M. (2018). Why is there something, rather than nothing? ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S. M., & Chen, J. (2004). Spontaneous inflation and the origin of the arrow of time. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0410270.

- Carroll, S. M., & Singh, A. (2018). Mad-dog Everettianism: Quantum mechanics at its most minimal. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Castro, P., Gatta, M., Croca, J. R., & Moreira, R. N. (2018). Spacetime as an emergent phenomenon: A possible way to explain entanglement and the tunnel effect. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 6, 2107–2118. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. K. (2017). Our fundamental physical space: An essay on the metaphysics of the wave function. The Journal of Philosophy, 114(7), 333–365. https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.14531.

- Chen, E. K. (2018). The intrinsic structure of quantum mechanics. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. K. (2019). Realism about the wave function. Philosophy Compass, 14(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. K. (2020a). The past hypothesis and the nature of physical laws. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. K. (2020b). Bell’s theorem, quantum probabilities, and superdeterminism. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Clifton, R., & Monton, B. (1999). Losing your marbles in wavefunction collapse theories. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 50(4), 697–717. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S., & De Luccia, F. (1980). Gravitational effects on and of vacuum decay. Physical Review D, 21(12), 3305–3315. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A. (2001). Realism and underdetermination: Some clues from the practices-up. Philosophy of Science, 68(S3), S301–S312. [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, F. A. B., & Wreszinski, W. F. (2016). Instantaneous spreading versus space localization for nonrelativistic quantum systems. Brazilian Journal of Physics, 46(4), 462–470. [CrossRef]

- Crouse, D. T. (2016). On the nature of discrete space-time: The atomic theory of space-time and its effects on Pythagoras’s theorem, time versus duration, inertial anomalies of astronomical bodies, and special relativity at the Planck scale. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Crouse, D., & Skufca, J. (2018). On the nature of discrete space-time: Part 1: The distance formula, relativistic time dilation, and length contraction in discrete space-time. [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. (1996, April 27). The day time began. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg15020274-200-the-day-time-began/.

- Davies, P. (1997). The last three minutes: Conjectures about the ultimate fate of the universe. Phoenix.

- Davies, P. (2011, November 16). Nothingness: The turbulent life of empty space. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21228390-800-nothingness-the-turbulent-life-of-empty-space/.

- Davis, T. M., & Lineweaver, C. H. (2004). Expanding confusion: Common misconceptions of cosmological horizons and the superluminal expansion of the universe. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 21(1), 97–109. [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B. S. (1967). Quantum theory of gravity. I. the canonical theory. Physical Review, 160(5), 1113–1148. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Tejedor, A., & Sudarsky, D. (2012). Towards a formal description of the collapse approach to the inflationary origin of the seeds of cosmic structure. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2012(07), 045–045. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, R. (2014). The origin of irreversibility. Department of Astronomy, Harvard University. https://www.informationphilosopher.com/problems/reversibility/Irreversibility.pdf.

- Durham, I. T. (2018). Bell’s theory of beables and the concept of `universe’. ArXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Dürr, D., Goldstein, S., Taylor, J. O., Tumulka, R., & Zanghi, N. (2006). Topological factors derived from Bohmian mechanics. Annales Henri Poincaré, 7(4), 791–807. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F. J. (1979). Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe. Reviews of Modern Physics, 51(3), 447–460. [CrossRef]

- Eddington, A. S. (1929). The nature of the physical world. Cambridge University Press. https://henry.pha.jhu.edu/Eddington.2008.pdf.

- Egg, M. (2021). Quantum ontology without speculation. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Egg, M., & Esfeld, M. (2014). Primitive ontology and quantum state in the GRW matter density theory. Synthese, 192(10), 3229–3245. [CrossRef]

- Egg, M., & Saatsi, J. (2021). Scientific realism and underdetermination in quantum theory. Philosophy Compass, 16(11). [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (2011). Letters on wave mechanics: Correspondence with H.A. Lorentz, Max Planck, and Erwin Schrodinger (K. Przibram, Ed.). Open Road Integrated Media.

- Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., & Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Physical Review, 47(10), 777–780. [CrossRef]

- Esfeld, M. (2012). Ontic structural realism and the interpretation of quantum mechanics. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 3(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Esfeld, M. (2014). Science and metaphysics: The case of quantum physics. In A. Reboul (Ed.), Mind, Values, and Metaphysics Vol.1 (pp. 267–285). Springer International Publishing. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/3401/1/Esfeld-MetScience.pdf.

- Esfeld, M. (2016). Collapse or no collapse? What is the best ontology of quantum mechanics in the primitive ontology framework? In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin, and Implications. Cambridge University Press. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/12666/.

- Esfeld, M. (2019). From the measurement problem to the primitive ontology programme. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11058.

- Esfeld, M., & Gisin, N. (2014). The GRW flash theory: A relativistic quantum ontology of matter in space-time? Philosophy of Science, 81(2), 248–264. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P. (2017). The character of physical law. The MIT Press. https://www.ling.upenn.edu/~kroch/courses/lx550/readings/feynman1-4.pdf (Original work published 1967).

- Fine, A. (1996). The shaky game. University of Chicago Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2215622.

- Fleming, G. (1996). Just how radical is hyperplane-dependence? In R. Clifton (Ed.), Perspectives on Quantum Reality: Non-Relativistic, Relativistic and Field Theoretic (pp. 11–28). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-015-8656-6_2.

- Forrest, P. (1988). Quantum metaphysics. Blackwell. https://philpapers.org/rec/FORQM.

- Fortin, S., Alberto, J., & Arriaga, J. (2018). About the nature of the wave function and its dimensionality: The case of quantum chemistry. PhilSci Archive. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/14868/1/3N-Dimensions.pdf.

- Frigg, R. (2018). Properties and the Born rule in GRW theory. In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin, and Implications. (pp. 124–133). Cambridge University. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/20933/.

- Gao, S. (2013). A discrete model of energy-conserved wavefunction collapse. Royal Society Publishing. https://arxiv.org/abs/1304.0439.

- Gao, S. (2013b). Three possible implications of spacetime discreteness. PhilArchive. https://philarchive.org/archive/GAOTIOv1.

- Gao, S. (2016). The meaning of the wave function: In search of the ontology of quantum mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.02738.

- Gao, S. (2017). Is an electron a charge cloud? A reexamination of Schrödinger’s charge density hypothesis. Foundations of Science, 23(1), 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. (2018a). Against the field ontology of quantum mechanics. PhilSci Archive. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/id/eprint/15476.

- Gao, S. (2018b). Collapse of the wave function: Models, ontology, origin, and implications. Cambridge University Press.

- Gao, S. (2019). Quantum theory is incompatible with relativity: A new proof beyond Bell’s theorem and a test of unitary quantum theories. PhilSci Archive. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/16155/.

- Gao, S. (2020). A puzzle for the field ontologists. Foundations of Physics, 50(11), 1541–1553. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. (2022). Reality of mass and charge and its implications for the meaning of the wave function. PhilSci Archive. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/21317/.

- Garfinkle, D., Ijjas, A., & Steinhardt, P. J. (2023). Initial conditions problem in cosmological inflation revisited. Physics Letters B, 843, 138028. [CrossRef]

- Geert, D. (2006). The ontology of spacetime (D. Dieks, Ed.). Elsevier. https://philpapers.org/rec/DIETOO.

- Genovese, M. (2016). Experimental tests of Bell inequalities. In S. Gao & M. Bell (Eds.), Quantum Nonlocality and Reality: 50 Years of Bells Theorem. Cambridge University Press. https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.1804.

- Genovese, M. (2023). Can quantum non-locality be connected to extra-dimensions? International Journal of Quantum Information, 21(07), 2340003. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M., & Gramegna, M. (2019). Quantum correlations and quantum non-locality: A review and a few new ideas. Applied Sciences, 9(24), 5406. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G. (2009a). The interpretation of quantum mechanics: Where do we stand? Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 174, 012013. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G. (2009b). Does quantum nonlocality irremediably conflict with special relativity? Foundations of Physics, 40(9-10), 1379–1395. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G. (2021). Sneaking a look at god’s cards. Princeton University Press.

- Ghirardi, G. C., Pearle, P., & Rimini, A. (1990). Markov processes in Hilbert space and continuous spontaneous localization of systems of identical particles. Physical Review A, 42(1), 78–89. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G. C., Rimini, A., & Weber, T. (1986). Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems. Physical Review D, 34(2), 470–491. [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S. B. (2019). Black holes in the quantum universe. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 377(2161), 20190029. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S. (1998a). Quantum theory without observers—part one. Physics Today, 51(3), 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S. (1998b). Quantum theory without observers—part two. Physics Today, 51(4), 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S., Norsen, T., Tausk, D., & Zanghi, N. (2011). Bell’s theorem. Scholarpedia, 6(10), 8378. [CrossRef]

- Graham, P. W., Kaplan, D. E., & Rajendran, S. (2018). Born again universe. Physical Review D, 97(4). [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, D. M., Horne, M. A., & Zeilinger, A. (2007). Going beyond Bell’s theorem. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/0712.0921.

- Griffiths, D. J., & Schroeter, D. F. (2018). Introduction to quantum mechanics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Gröblacher, S., Paterek, T., Kaltenbaek, R., Brukner, Č., Żukowski, M., Aspelmeyer, M., & Zeilinger, A. (2007). An experimental test of non-local realism. Nature, 446(7138), 871–875. [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, A. (2009). Why is there a world AT ALL, rather than just nothing? Ontology Studies, 9, 7–19.

- Guerreiro, T., Sanguinetti, B., Zbinden, H., Gisin, N., & Suárez, A. (2012). Single-photon space-like antibunching. Physics Letters, 376(32), 2174–2177. [CrossRef]

- Guth, A. H. (2007). Eternal inflation and its implications. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 40(25), 6811–6826. [CrossRef]

- Hagar, A. (2015). Discrete or continuous?: The quest for fundamental length in modern physics. Choice Reviews Online, 52(06), 52–3157. [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, N., & Spekkens, R. W. (2010). Einstein, incompleteness, and the epistemic view of Quantum states. Foundations of Physics, 40(2), 125–157. [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J. B. (1997). Quantum cosmology: Problems for the 21st century. Physics in the 21st Century, 179–199. [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J. B., & Hawking, S. W. (1983). Wave function of the universe. Physical Review D, 28(12), 2960–2975. [CrossRef]

- awking, S. W., & Penrose, R. (1970). The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 314(1519), 529–548. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B. (2012). The science of sticky spheres. American Scientist, 100(6), 442–442. [CrossRef]

- Hegerfeldt, G. C. (1998). Instantaneous spreading and Einstein causality in quantum theory. Annalen Der Physik, 7(7-8), 716–725. about:blank.

- Hitchcock, C. (2004). Contemporary debates in philosophy of science. Blackwell Pub.

- Hobson, A. (2013). There are no particles, there are only fields. American Journal of Physics, 81(3), 211–223. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, A. (2019). Realist analysis of six controversial quantum issues. In M. R. Matthews (Ed.), Mario Bunge: A Centenary Fetschrift (pp. 329–348). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://browse.arxiv.org/pdf/1901.02088.pdf.

- Holman, M. (2018). How problematic is the near-Euclidean spatial geometry of the large-scale universe? Foundations of Physics, 48(11), 1617–1647. [CrossRef]

- Holt, J. (2012). Why does the world exist?: An existential detective story. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hooft, G. t. (2018). Time, the arrow of time, and quantum mechanics. Frontiers in Physics, 6. [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. (2013). Minimal length scale scenarios for quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. (2014). Theory and phenomenology of space-time defects. Advances in High Energy Physics, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. (2018). Lost in math. Basic Books.

- Howard, D. (1985). Einstein on locality and separability. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 16(3), 171–201. [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. (1989). Holism, separability, and the metaphysical implications of the bell experiments. In E. McMullin (Ed.), Philosophical consequences of quantum theory: Reflections on Bell’s theorem (pp. 224–253). University of Notre Dame Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/HOWHSA-2.

- Howard, D. (1990). “Nicht sein kann was nicht sein darf,” or the prehistory of EPR, 1909–1935: Einstein’s early worries about the quantum mechanics of composite systems. In A. I. Miller (Ed.), Sixty-Two Years of Uncertainty (pp. 61–111). Cambridge University. [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. (2004). Who invented the “Copenhagen Interpretation”? A study in mythology. Philosophy of Science, 71(5), 669–682. [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M., & Romano, D. (2018). The wave-function as a multi-field. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 8(3), 521–537. [CrossRef]

- Huggett, N., & Wuthrich, C. (2021). Out of nowhere: Introduction: The emergence of spacetime. PhilArchive. [CrossRef]

- Huggett, N., & Wüthrich, C. (2013). Emergent spacetime and empirical (in)coherence. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 44(3), 276–285. [CrossRef]

- Ijjas, A., & Steinhardt, P. J. (2022). Entropy, black holes, and the new cyclic universe. Physics Letters B, 824, 136823. [CrossRef]

- Ijjas, A., Steinhardt, P. J., & Loeb, A. (2013). Inflationary paradigm in trouble after Planck2013. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Isam, A. (2018). Spacetime discreteness: Shedding light on two of the simplest observations in physics. Journal of Modern Physics, 09(07), 1415–1431. [CrossRef]

- Jammer, M. (1974). The philosophy of quantum mechanics. Wiley-Interscience.

- Jones, R. H. (2018). Mystery 101: Introduction to the big questions and the limits of human knowledge. State University of New York. https://philpapers.org/rec/JONMA-2.

- Karam, R. (2020). Why are complex numbers needed in quantum mechanics? Some answers for the introductory level. American Journal of Physics, 88(1), 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Kastner, R. (2017). On quantum collapse as a basis for the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy, 19(3), 106. [CrossRef]

- Klevgard, P. A. (2020). The Mach-Zehnder interferometer and photon dualism. In J. A. Shaw, K. Creath, & V. Lakshminarayanan (Eds.), In Light in Nature VIII (pp. 61–81). SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S., & Specker, E. (1967). The problem of hidden variables in quantum mechanics. Indiana University Mathematics Journal, 17(1), 59–87. [CrossRef]

- Kragh, H. (2013). What’s in a name: History and meanings of the term “big bang.” ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, L. M. (2012). A universe from nothing: Why is there something rather than nothing? Free Press.

- Kumar, M. (2011). Quantum : Einstein, Bohr, and the great debate about the nature of reality. W.W. Norton & Co.

- Lam, V., & Wüthrich, C. (2018). Spacetime is as spacetime does. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 64, 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Landsman, K., & Reuvers, R. (2013). A flea on Schrodinger’s cat. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, R. L., & Sudarsky, D. (2023). Eternal inflation and collapse theories. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Leggett, A. J. (2003). Nonlocal hidden-variable theories and quantum mechanics: An incompatibility theorem. Foundations of Physics, 33(10), 1469–1493. [CrossRef]

- Leifer, M. S. (2014). Is the quantum state real? An extended review of ψ-ontology theorems. Quanta, 3(1), 67. [CrossRef]

- León, G., Landau, S. J., & Piccirilli, M. P. (2014). Quantum collapse as a source of the seeds of cosmic structure during the radiation era. Physical Review, 90(8). [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J., & Kuhn, R. L. (2013). The mystery of existence. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lewis, P. (1995). GRW and the tails problem. Topoi, 14(1), 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. (2004). Life in configuration space. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 55(4), 713–729. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. J. (2013). Dimension and illusion. In A. Ney & D. Albert (Eds.), The Wave Function: Essays on the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 110–125). Oxford University Press. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/8841/.

- Lewis, P. J. (2016). Quantum ontology: A guide to the metaphysics of quantum mechanics. Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, P. J. (2017). On the status of primitive ontology. In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin, and Implications (pp. 154–166). Cambridge University. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/14421/.

- Lineweaver, C. H., & Davis, T. M. (2005, March). Misconceptions about the Big Bang. Scientific American, 292(3), 36–45. [CrossRef]

- Lucia, U., & Grisolia, G. (2022). Thermodynamic definition of time: Considerations on the EPR paradox. Mathematics, 10(15), 2711. [CrossRef]

- Mack, K. (2020). The end of everything: (Astrophysically speaking). Scribner.

- Mariani, C. (2022a). Does the primitive ontology of GRW rest on shaky ground? In V. Allori (Ed.), Quantum Mechanics and Fundamentality (pp. 127–139). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, C. (2022b). Non-accessible mass and the ontology of GRW. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 91, 270–279. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J., & Brandenberger, R. H. (2001). Trans-Planckian problem of inflationary cosmology. 63(12). ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0005209.

- Maudlin, T. (1995). Three measurement problems. Topoi, 14(1), 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2007). Completeness, supervenience, and ontology. Journal of Physics A, 40(12), 3151–3171. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2010). Can the world be only wavefunction? In S. Saunders, J. Barrett, A. Kent, & D. Wallace (Eds.), Everett, Quantum Theory, & Reality (pp. 121–143). [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2011). Quantum non-locality & relativity : Metaphysical intimations of modern physics. (3rd ed.). John Wiley.

- Maudlin, T. (2013a). Philosophy of physics: Space and time. Princeton University Press, 50(05), 50–2595. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2013b). The nature of the quantum state. In D. Albert & A. Ney (Eds.), The Wave Function: Essays on the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 126–153). [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2014). What Bell did. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 47(42), 424010. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2015). The universal and the local in quantum theory. Topoi, 34(2), 349–358. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2016). Local beables and the foundations of physics. In M. Bell & S. Gao (Eds.), Quantum Nonlocality and Reality: 50 Years of Bell’s Theorem (pp. 317–330). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2018). Ontological clarity via canonical presentation: Electromagnetism and the Aharonov–Bohm effect. Entropy, 20(6), 465. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. (2019). Philosophy of physics: Quantum theory (Vol. 9). Princeton University Press.

- Maudlin, T. (2020). Appreciating what he did. In V. Allori, A. Bassi, D. Durr, & N. Zanghi (Eds.), Do Wave Functions Jump? Perspectives of the Work of GianCarlo Ghirardi (pp. 55–61). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T., Okon, E., & Sudarsky, D. (2020). On the status of conservation laws in physics: Implications for semiclassical gravity. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 69, 67–81. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, C. D. (2015). Does inflation solve the hot Big Bang model’s fine-tuning problems? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 51, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- McQueen, K. J. (2015). Four tails problems for dynamical collapse theories. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 49, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Melia, F. (2020). The cosmic spacetime. CRC Press.

- Melia, F. (2021a). Thermodynamics of the rh = ct universe: A simplification of cosmic entropy. The European Physical Journal C, 81(234). [CrossRef]

- Melia, F. (2021b). Classicization of quantum fluctuations at the Planck scale in the rh = ct universe. Physics Letters B, 818, 136362. [CrossRef]

- Melia, F. (2022a). A candid assessment of standard cosmology. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 134(1042), 121001. [CrossRef]

- Melia, F. (2022b). Initial energy of a spatially flat universe -- a hint of its possible origin. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Melia, F. (2023). The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric and the principle of equivalence. Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung, 78(6), 525–533. [CrossRef]

- Mermin, N. D. (1981). Quantum mysteries for anyone. The Journal of Philosophy, 78(7), 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Monton, B. (2002). Wave function ontology. Synthese, 130(2), 265–277.

- Monton, B. (2004). The problem of ontology for spontaneous collapse theories. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 35(3), 407–421. [CrossRef]

- Monton, B. (2006). Quantum mechanics and 3n-dimensional space. Philosophy of Science, 73(5), 778–789. [CrossRef]

- Monton, B. (2013). Against 3n-dimensional space. In A. Ney & D. Albert (Eds.), The Wave Function: Essay in the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 154–167). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Musser, G. (2015). Spooky action at a distance: The phenomenon that reimagines space and time and what it means for black holes, the big bang, and theories of everything. Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Myrvold, W. C. (2002). On peaceful coexistence: Is the collapse postulate incompatible with relativity? Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 33(3), 435–466. [CrossRef]

- Myrvold, W. C. (2015). What is a wavefunction? Synthese, 192(10), 3247–3274. [CrossRef]

- Myrvold, W. C. (2017). Ontology for collapse theories. In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin, and Implications (pp. 97–123). Cambridge University Press. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/13318/.

- Myrvold, W. C. (2019a). Ontology for relativistic collapse theories. In O. Lombardi, S. Fortin, & C. Lopez (Eds.), Quantum Worlds: Perspectives on the Ontology of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 9–31). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Myrvold, W. C. (2019b). How could relativity be anything other than physical? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 67, 137–143. [CrossRef]

- Myrvold, W. C. (2019c). On the status of quantum state realism. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, A., Chopra, D., & Kafatos, M. C. (2019). The nature of the Heisenberg-von Neumann cut: Enhanced orthodox interpretation of quantum mechanics. Activitas Nervosa Superior, 61(12-17), 12–17. [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, A. (2019). Foundations of quantum physics I. A critique of the tradition. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Ney, A. (2016). Separability, locality, and higher dimensions in quantum mechanics. Philarchive.org. https://philarchive.org/rec/NEYSLA.

- Ney, A. (2021). The world in the wave function : A metaphysics for quantum physics. Oxford University Press.

- Ney, A. (2023). Three arguments for wave function realism. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Norsen, T. (2005). Einstein’s boxes. American Journal of Physics, 73(2), 164–176. [CrossRef]

- Norsen, T. (2010). The theory of (exclusively) local beables. Foundations of Physics, 40(12), 1858–1884. [CrossRef]

- Norsen, T. (2011). John S. Bell’s concept of local causality. American Journal of Physics, 79(12), 1261–1275. [CrossRef]

- Norsen, T. (2016). Quantum solipsism and nonlocality. In M. Bell & S. Gao (Eds.), Quantum Nonlocality and Reality: 50 Years of Bell’s Theorem (pp. 204–237). Cambridge University Press.

- Norsen, T. (2017). Foundations of quantum mechanics: An exploration of the physical meaning of quantum theory. Springer.

- Norsen, T. (2018). On the explanation of Born-rule statistics in the de Broglie-Bohm Pilot-Wave theory. Entropy, 20(6), 422. [CrossRef]

- Norsen, T., Marian, D., & X. Oriols. (2014). Can the wave function in configuration space be replaced by single-particle wave functions in physical space? Synthese, 192(10), 3125–3151. [CrossRef]

- North, J. (2013). The structure of a quantum world. In A. Ney & D. Albert (Eds.), The Wave Function Essays on the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanics (pp. 183–202). Oxford University Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/NORTSO-5.

- Ojo, A. (2005). On a thermodynamic basis for inflationary cosmology. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Okon, E., & Sudarsky, D. (2014). Benefits of objective collapse models for cosmology and quantum gravity. Foundations of Physics, 44(2), 114–143. [CrossRef]

- Oldofredi, A. (2018). Particle creation and annihilation: Two Bohmian approaches. Lato Sensu: Revue de La Société de Philosophie Des Sciences, 5(1), 77–85. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat.

- Patel, V., & Lineweaver, C. (2017). Solutions to the cosmic initial entropy problem without equilibrium initial conditions. Entropy, 19(8), 411. [CrossRef]

- Pearle, P. (1989). Combining stochastic dynamical state-vector reduction with spontaneous localization. Physical Review E, 39(5), 2277–2289. [CrossRef]

- Pearle, P. (2000). Wavefunction collapse and conservation laws. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0004067.

- Pearle, P. (2009). How stands collapse II. In W. Myrvold & J. Christian (Eds.), Quantum Reality, Relativistic Causality and Closing the Epistemic Circle: Essays in Honor of Abner Shimony (pp. 257–292). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1989a). The emperor’s new mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics. Oxford University Press.

- Penrose, R. (1989b). Difficulties with inflationary cosmology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 571(1), 249–264. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1996). On gravity’s role in quantum state reduction. General Relativity and Gravitation, 28(5), 581–600. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1997). Physics and the mind. In M. Longair (Ed.), The Large, the Small and the Human Mind (pp. 93–143). Cambridge University Press.

- Penrose, R. (2006). Before the big bang: An outrageous new perspective and its implications for particle physics. Proceedings of EPAC 2006, 060626, 2759–2767.

- Penrose, R. (2009). Black holes, quantum theory and cosmology. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 174, 012001. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (2018). The big bang and its dark-matter content: Whence, whither, and wherefore. Foundations of Physics, 48(10), 1177–1190. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A., Sahlmann, H., & Sudarsky, D. (2006). On the quantum origin of the seeds of cosmic structure. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 23(7), 2317–2354. [CrossRef]

- Price, H. (1995). Cosmology, time’s arrow, and that old double standard. In S. Savitt (Ed.), Time’s Arrows Today: Recent Physical and Philosophical Work on the Direction of Time (pp. 66–94). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Price, H. (1996). Time’s arrow & Archimedes’ point : New directions for the physics of time. Oxford University Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/PRITAA-2.

- Price, H. (2004). On the origins of the arrow of time: Why there is still a puzzle about the low entropy past. In C. Hitchcock (Ed.), Contemporary Debates in the Philosophy of Science (pp. 219–239). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://philpapers.org/rec/PRIOTO-2.

- Pusey, M. F., Barrett, J., & Rudolph, T. (2012). On the reality of the quantum state. Nature Physics, 8(6), 475–478. [CrossRef]

- Redd, N. T. (2013). What is dark energy? Space.com. https://www.space.com/20929-dark-energy.html.

- Renou, M.-O., Trillo, D., Weilenmann, M., Thinh, L. P., Tavakoli, A., Gisin, N., Acín, A., & Navascués, M. (2021). Quantum physics needs complex numbers. Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348802613_Quantum_physics_needs_complex_numbers.

- Romano, D. (2020). Multi-field and Bohm’s theory. Synthese, 198(11), 10587–10609. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2006). The disappearance of space and time. In D. Dieks (Ed.), The Ontology of Spacetime (Vol. 1, pp. 25–36). Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871177406010023.

- Rovelli, C. (2011). “Forget time.” Foundations of Physics, 41(9), 1475–1490. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2019). Where was past low-entropy? Entropy, 21(5), 466. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C., Carnell, S., & Segre, E. (2018). Reality is not what it seems: The journey to quantum gravity. Riverhead Books.

- Rovelli, C., & Smolin, L. (1995). Discreteness of area and volume in quantum gravity. Nuclear Physics B, 442(3), 593–619. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C., & Speziale, S. (2003). Reconcile Planck-scale discreteness and the Lorentz-Fitzgerald contraction. Physical Review D, 67(6). [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C., & Vidotto, F. (2022). Philosophical foundations of loop quantum gravity. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M. (2005). Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 76(4), 1267–1305. [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M. (2019). The quantum-to-classical transition and decoherence. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Sebens, C. T. (2021). Electron charge density: A clue from quantum chemistry for quantum foundations. Foundations of Physics, 51(4). [CrossRef]

- Sebens, C. T. (2023). Eliminating electron self-repulsion. Foundations of Physics, 53(4). [CrossRef]

- Sedley, D. (1982). Two conceptions of vacuum. Phronesis, 27(1-2), 175–193. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R. (1994). Principles of quantum mechanics (2nd ed.). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. P. (2017). Wave function collapse, non-locality, and space-time structure. In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology Origin, and Implications (pp. 295–311). [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. P. (2018). Space-time from collapse of the wave-function. Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung A, 74(2), 147–152. [CrossRef]

- Slowik, E. (2016). A historical defense of non-spacetime hypotheses: Non-Local beables and Leibnizian Ubeity. Philosophia Scientiae, 20(3), 149–166. [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. (2004). Atoms of space and time. Scientific American, 290(1), 66–75. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26172656.

- Smolin, L. (2008). Generic predictions of quantum theories of gravity. In D. Oriti (Ed.), Approaches to Quantum Gravity: Toward a New Understanding of Space, Time, and Matter (pp. 548–570). Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0605052.

- Smolin, L. (2017). Three roads to quantum gravity. Basic Books.

- Snyder, D. M. (2000). Irreversibility and measurement in quantum mechanics. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Solé, A. (2013). Bohmian mechanics without wave function ontology. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 44(4), 365–378. [CrossRef]

- Solé, A., & Hoefer, C. (2015). Introduction: Space–time and the wave function. Synthese, 192(10), 3055–3070. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, R. (2020). Nothingness. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/nothingness/.

- Srinivas, M. (1980). Collapse postulate for observables with continuous spectra. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 71(2), 131–158. [CrossRef]

- Stapp, H. P. (2017). Quantum theory and free will. In Springer eBooks. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P. J. (2011, April 1). The inflation debate: Is the theory at the heart of modern cosmology deeply flawed? Scientific American, 18–25. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-inflation-summer/.

- Steinhardt, P. J., & Turok, N. (2007). Endless universe : Beyond the big bang. Broadway Books.

- Stoica, O. C. (2019). Representation of the wave function on the three-dimensional space. Physical Review A, 100(4). [CrossRef]

- Sudarsky, D. (2010). The quantum origin of the seeds of cosmic structure: The case for a missing link. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1256, 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsky, D. (2011). Shortcomings in the understanding of why cosmological perturbations look classical. International Journal of Moder Physics D, 20(04), 509–552. [CrossRef]

- Tatum, E. T. (2018). Why flat space cosmology is superior to standard inflationary cosmology. Journal of Modern Physics, 09(10), 1867–1882. [CrossRef]

- Tatum, E. T., & Seshavatharam, U. (2021). Flat space cosmology. Universal-Publishers.

- Torre, A. (2016). Do we finally understand quantum mechanics? ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Tumulka, R. (2017). Paradoxes and primitive ontology in collapse theories of quantum mechanics. In S. Gao (Ed.), Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin and Implications (pp. 134–153). Cambridge University Press. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1102.5767.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

- Turok, N., & Boyle, L. (2022). Gravitational entropy and the flatness, homogeneity and isotropy puzzles. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Turok, N., & Boyle, L. (2023). A minimal explanation of the primordial cosmological perturbations. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Unger, R. M., & Smolin, L. (2015). The singular universe and the reality of time : A proposal in natural philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

- Vagnozzi, S., & Loeb, A. (2022). The challenge of ruling out inflation via the primordial graviton background. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 939(2), L22. [CrossRef]

- Vaidman, L. (2020). Derivations of the born rule. In M. Hemmo & O. Shenko (Eds.), Jerusalem Studies in Philosophy and History of Science (pp. 567–584). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Vaidman, L. (2021a). Many-Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/qm-manyworlds.

- Vaidman, L. (2021b). Wave function realism and three dimensions. In V. Allori (Ed.), Quantum Mechanics and Fundamentality; Naturalizing Quantum Theory between Scientific Realism and Ontological Indeterminacy . Springer. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/19979/.

- Verlinde, E. (2000). On the holographic principle in a radiation dominated universe. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. (2011). On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics, 4, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A. (1982). Creation of universes from nothing. Physics Letters B, 117(1-2), 25–28. [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. (1955). Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics (R. Beyer, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

- Wald, R. M. (2006). The arrow of time and the initial conditions of the universe. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 37(3), 394–398. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. (2010). Gravity, entropy, and cosmology: In search of clarity. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 61(3), 513–540. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. (2017). Against wavefunction realism. In S. Dasgupta, R. Dotan, & B. Weslake (Eds.), Current Controversies in Philosophy of Science (pp. 63–74). Routledge. https://philpapers.org/rec/WALAWR-3.

- Wallace, D. (2018). On the plurality of quantum theories: Quantum theory as a framework, and its implications for the quantum measurement problem. In S. French & J. Saatsi (Eds.), Scientific Realism and the Quantum Measurement Problem (pp. 78–102). Oxford University Press. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/15292/.

- Wallace, D. (2019). What is orthodox quantum mechanics? In A. Cordero (Ed.), Philosophers Look at Quantum Mechanics (pp. 285–312). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. (2018). Why black hole information loss is paradoxical. ArXiv.org. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D., & Timpson, C. G. (2010). Quantum mechanics on spacetime I: Spacetime state realism. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 61(4), 697–727. [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, J. O. (2016). Void. Yale University Press.

- Webb, J. (2014). Nothing : Surprising insights everywhere from zero to oblivion. Profile Books Ltd.

- Wechsler, S. (2021). About the nature of the quantum system—an examination of the random discontinuous motion interpretation of the quantum mechanics. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 11(03), 99–111. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, S. D. (2020). In praise and in criticism of the model of continuous spontaneous localization of the wave-function. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 10(04), 73–103. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, S. D. (2021). The quantum mechanics needs the principle of wave-function collapse—but this principle shouldn’t be misunderstood. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 11(01), 42–63. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, H. M. (2006). From Einstein’s theorem to Bell’s theorem: a history of quantum non-locality. Contemporary Physics, 47(2), 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Witherall, A. (2001). The fundamental question. Journal of Philosophical Research, 26, 53–87. https://philpapers.org/rec/WITTFQ.

- Wittgenstein, L., & Russell, B. (2021). Tractatus logico-philosophicus (C. K. Ogden, Trans.). Routledge. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5740/5740-pdf.pdf (Original work published 1921).

- Wolf, W. J., & Thébault, K. P. Y. (2023). Explanatory depth in primordial cosmology: A comparative study of inflationary and bouncing paradigms. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Despite the Dual Ontology’s unique structure, “It may be that a real synthesis of quantum and relativity theories requires not just technical developments but radical conceptual renewal.” (Bell, 2004, p. 171). |

| 2 | See (Monton, 2002, 2006) regarding mixed ontologies and the problems associated with ontologies that are not based upon a one-to-one identity and mapping. See also (Maudlin, 2013b). |

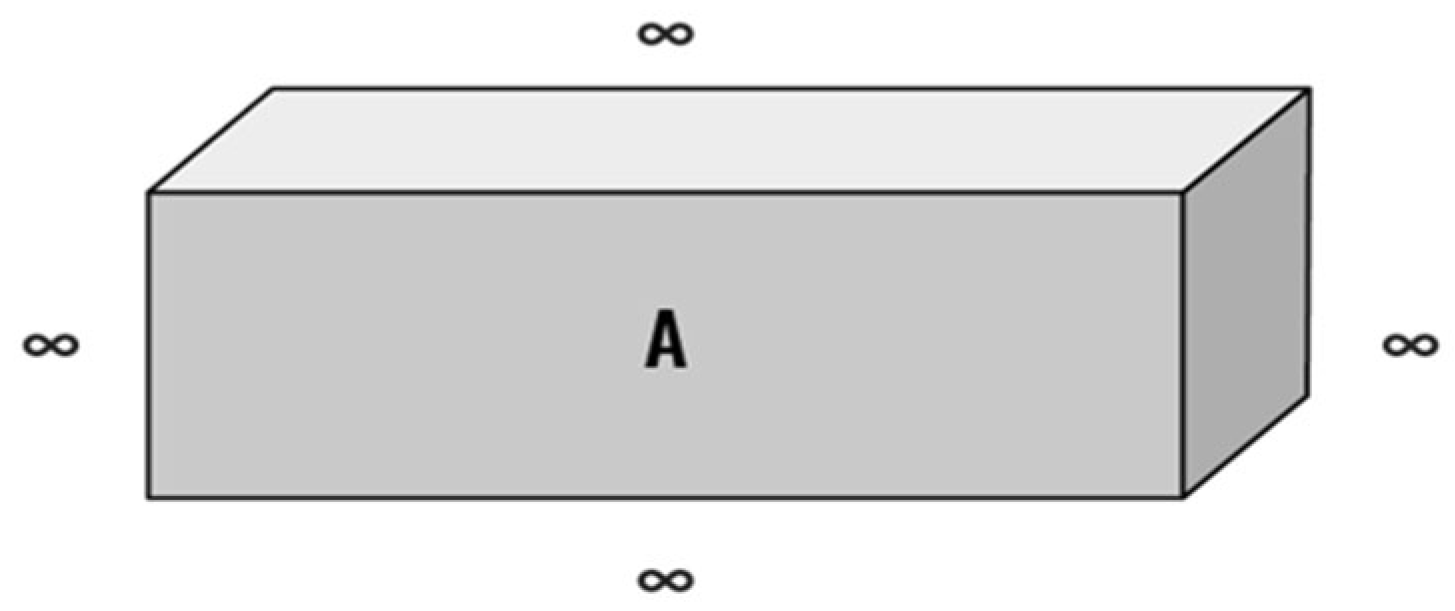

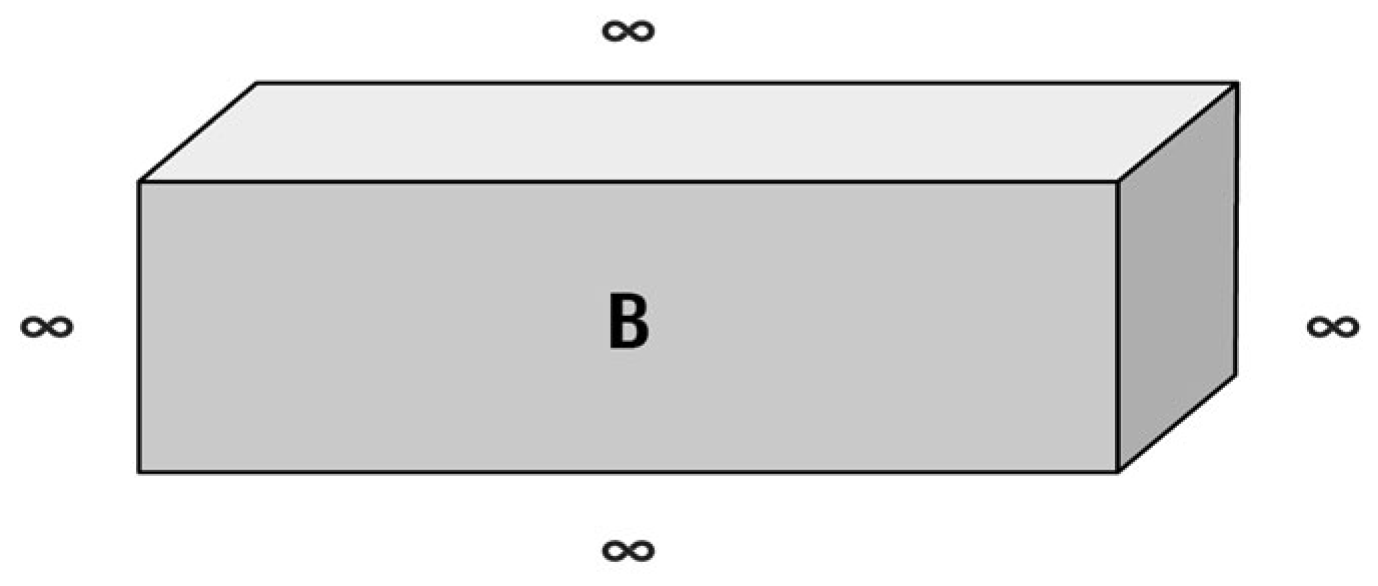

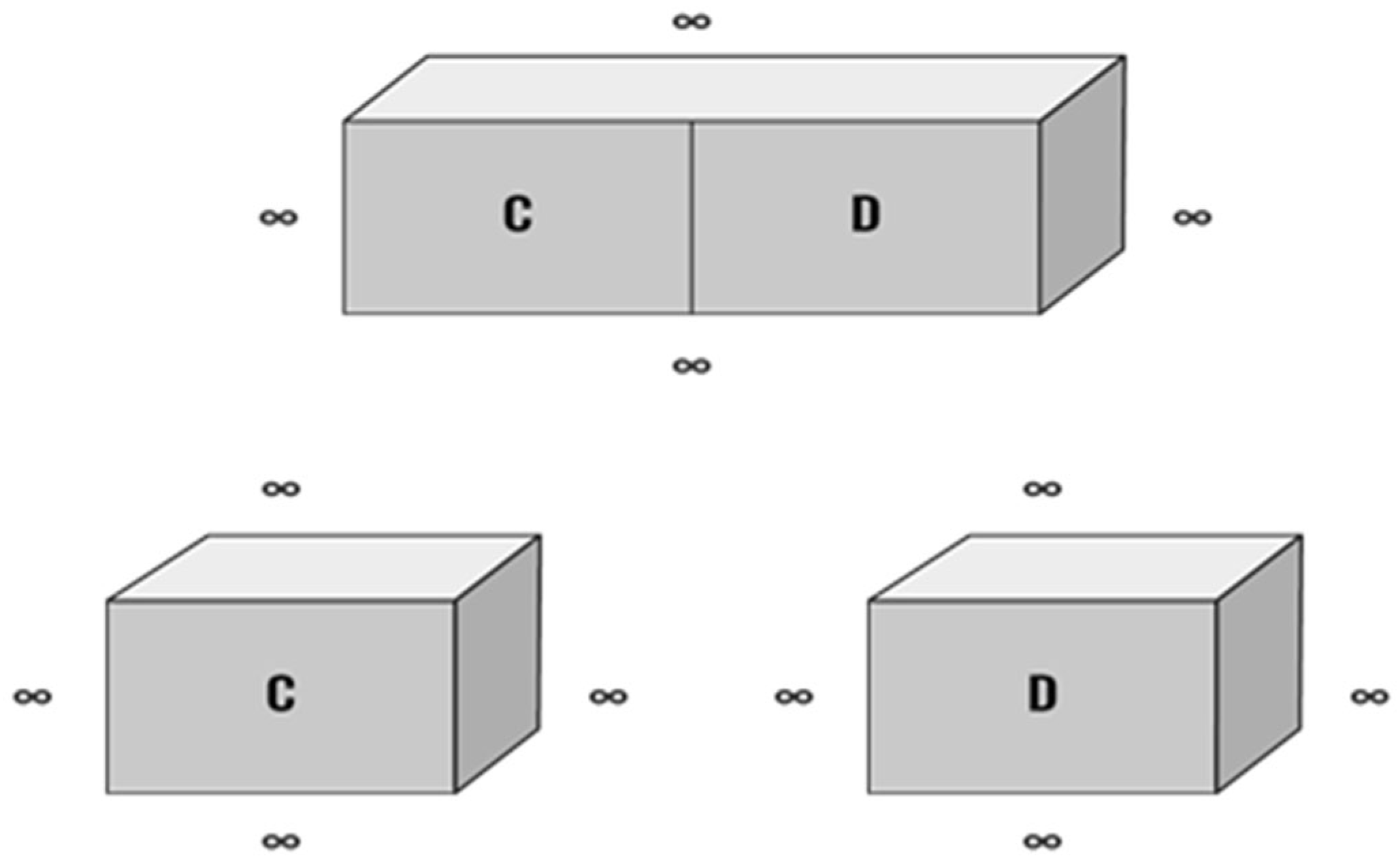

| 3 | In the abstract, a ((3 x N) + 3) hyperspace formed by a (3 x N) Planck Space and the three spatial dimensions of 4D spacetime appears to be an imposing physical structure. From a non-technical perspective, however, the closed universe formed by the Dual Ontology is a combination of the 4D spacetime of everyday experience and a many-dimensional Planck Space. The Planck Spheres that comprise 4D spacetime on a one-to-one basis also comprise Planck Space. As a simple example, assume that there are 5 Planck Spheres in 4D spacetime, one each somewhere on Venus, Mars, the Milky Way Galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy, and the Orion Constellation. The 5 Planck Spheres in 4D spacetime form a (3 x N) space in Planck Space where N equals five, and the number of dimensions equals 15. Unlike 4D spacetime, the Planck Spheres in Planck Space are not separated by time, space, or volume. All of the Planck Spheres in 4D spacetime and the corresponding Planck Spheres in Planck Space form a closed ((3 x N) +3) hyperspace where (3 x N) represents Planck Space and “3” represents the three spatial dimensions of 4D spacetime. |

| 4 | For a discussion regarding a mathematical (3 x N) dimensional space composed of an ordered N-tuple of ordered triples and the difference between a (3 x N) space and a 3N space, see (Lewis, 2013, pp. 116-118). |

| 5 | “My own view is that…belief in the completeness of Relativity as an account of space-time structure has been irrationally fetishized just as belief in the completeness of the quantum-mechanical description had been by Bohr and company.” (Maudlin, 2014, p. 24). |

| 6 | See generally (Maudlin, 2013b, 2019, pp. 36-37 and 79-93); (Monton, 2006); (Pusey et al., 2012). |

| 7 | (Barrow, 2002); (Grunbaum, 2009); (Holt, 2012). The existence of the SOAN turns one of the greatest philosophical questions of all time on its head. The question is not, “Why is there something rather than nothing.” Rather, the question is, “Why is there something AND nothing.” |

| 8 | See section 2.1 for a complete definition. |

| 9 | See generally (Bedingham, 2021); (Gao, 2018, pp. 248-253); (Smolin, 2004). |

| 10 | The calculation assumes the diameter of a Planck Sphere equals the Planck length. The designation of a Planck Sphere as the smallest unit of space is illustrative only. The actual shape and size of the smallest unit of space may differ. |

| 11 | See (Howard, 1989, pp. 247-253) for an early consideration of higher dimensional spaces. |

| 12 | See also (Albert, 1992, 2013); (Chen, 2019); (Ney, 2021) regarding the ontic nature of a wave function in higher dimensional 3N spaces. |

| 13 | See also (Genovese, 2023); (Genovese and Gramenga, 2022). |

| 14 | See Section 4.3 for a discussion on the physical triggers for quantum state collapse and Section 4.5 for a more comprehensive discussion regarding instantaneity. |

| 15 | The location of a quantum state following its collapse is unknown. Accordingly, the term “generally localized” denotes the general location of a quantum state in 4D spacetime. See Section 4.4 for a more complete discussion. |

| 16 | For a mathematical 3N notation the transition would be ∣ψ 1,2⟩→∣ψ 1⟩⊗∣ψ 2⟩. The (3 x N) notation describes the transition of an entangled state to a product state in a physical (3 x N) Planck Space in which there is a one-to-one mapping and identity between a Planck Sphere in 4D spacetime and Planck Space. |

| 17 | See also (Ney, 2021, pp. 10-11). |

| 18 | This conclusion is at odds with the Born rule and its probability density interpretation of wave-function collapse for continuous variables. Not only does the physical structure of the Dual Ontology differ from the ontology used to derive the Born Rule, but the collapse of a quantum state to a discrete subset of the Bell Quantum Spheres occupied by the quantum state prior to collapse is a probability, not a probability density. Rather than integrating a density function of the quantum state over a continuous space, the likelihood of generally locating the electron in a “discrete, constrained space” is a probability based on the square modulus of the quantum state’s wave function. OpenAI. (2023). Background information on the Born Rule. See also (Norsen, 2017, pp. 238-239) regarding the use of two real functions to replace a complex wave function in 4D spacetime. |

| 19 | Note that the “Planck Energy Hyper-Point” and “4D Energy Field” include dark energy and any other form of energy not yet identified. |

| 20 | For extensive information regarding the Planck data, see (Aghanim et al., 2018). |

| 21 | More technically, data from the Planck satellite and other sources indicates that the curvature parameter Ωk is -0.0005 ± 0.0005, corresponding to a 4D spacetime within 0.1% of being flat. Accordingly, ρ4D =

|

| 22 | See generally (Carroll & Chen, 2004); (Penrose, 1991, 2006). |

| 23 | The CMB and related data indirectly indicate that the spatial geometry of 4D spacetime was nearly homogeneous and isotropic near t = 0. The FLRW metric supports a spatial geometry that is homogeneous and isotropic at each 3D time slice. |

| 24 | The generalized localization of 4D Spacetime at t = 0 does not involve the destruction or localization of the Planck Spheres that comprise Planck Space, nor does it affect the SOAN. Although the energy content of the 4D Energy Field and the Planck Energy Hyper-Point are localized at t = 0, Planck Spheres and the SOAN continue to form an ultra-high dimensional (3 x N) space. See Section 7. |

| 25 | See (Holt, 2012) for an extensive discussion on the issues associated with a physical state of nothingness. See also (Barrow, 2002); (Kuhn, 2013). |

| 26 | The SOAN is a difficult concept to grasp fully. For example, see (Davies, 2013, p. 126). “The concept of a true void…strikes many people as preposterous or even meaningless. If two bodies are separated by nothing, should they not be in contact? How can ‘emptiness’ keep things apart or have properties such as size or boundaries?” |

| 27 | See also, Interview with Sean Carroll, Vice Magazine On Line. What is Nothing? with Nick Rose, October 31, 2018. |

| 28 | (Bedingham, 2016); (Hagar, 2014); Hossenfelder, 2013); (Rovelli, 2017); OpenAI (2023). |

| 29 | Arguments in favor of the discretization of space have been proposed based upon mathematics, electrodynamics, quantum electrodynamics, loop quantum gravity, loop quantum cosmology, string theory, discrete lattice, asymptotic safe gravity, causal sets, spin foams, deformed special relativity, causal dynamical triangulation, quantum graphity, and black hole theory among others. (Crouse, 2016); (Crouse & Skufca, 2018); (Hagar, 2014); (Hossenfelder, 2014). |

| 30 | (Hossenfelder, 2013). |

| 31 | The non-relativistic Schrödinger equation is based on a continuous 3D space and treats time as a separate parameter. |

| 32 | Black holes are also composed of Planck Spheres. |

| 33 | See also footnote 4. |

| 34 | (Lewis, 2013, p. 116); (Ney, 2013). Note also that a (3N + 3) hyperspace raises serious theoretical and mathematical issues. A wavefunction that describes a quantum state in a 3N space cannot simultaneously describe the same quantum state in a discrete 3D space. |

| 35 | “We first note that most authors agree that habitable universes should have only one time dimension [56, 84, 506, 507]. If space-time had more than one temporal dimension, then closed time-like loops could be constructed. Such loops, in turn, allow for observers to revisit the “past” and thereby affect causality. In addition to violations of causality, multiple time dimensions can lead to violations of unitarity, tachyons, and ghosts [212].” (Adams, 2019, p. 158). |

| 36 | Unlike quantum mechanics, quantum chemistry often approaches N-body quantum states differently. See generally (Fortin et al., 2018); (Sebens, 2021). |

| 37 | For an alternative approach, see (Norsen et al., 2015). |

| 38 | The preferred basis for all observations of a quantum state is the position basis. “The second moral is that in physics the only observations we must consider are position observations, if only the positions of instrument pointers.” (Bell, 204, p. 161). See also (Maudlin, 2019, pp. 48-50). |

| 39 | See section 4.3 below for additional information on “physical triggers.” |

| 40 | See section 4.4 for additional information on generalized localization. |

| 41 | (Allori, 2022); (Bricmont, 2016); (Broglie, 1964); (Norsen, 2005). |

| 42 | See generally (Allori et al., 2021). |

| 43 | Despite its metaphorical usefulness, “quantum tunneling” is neither a jump nor a tunneling process. The instantaneous collapse of a quantum state at some point after the quantum state’s leading edge has passed through a physical barrier that is classically impenetrable reflects the collapse of the quantum state’s Bell Quantum Hyper-Point, not the tunneling of the entire quantum state through an otherwise impassible barrier. Following the quantum state’s collapse, its Bell Quantum Field is generally localized on the other side of the physical barrier. See generally (Castro et al., 2018). |

| 44 | The dynamic evolution and collapse of quantum states also apply to black hole information loss. See generally (Giddings, 2019); (Wallace D., 2018). |

| 45 | (Bohm, 1951, pp. 611-619). |

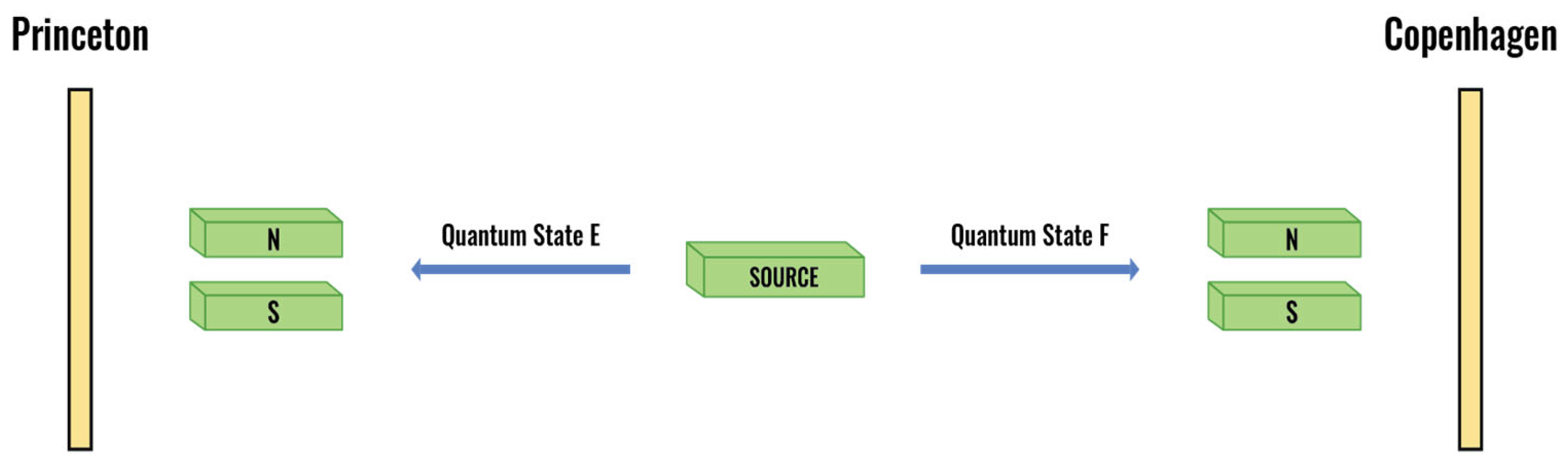

| 46 | Although the Stern-Gerlach experiment in the z direction is conducted in 4D spacetime on either Bell Quantum Field E in Princeton or Bell Quantum Field F in Copenhagen, the Bell Identity ensures that the experiment is simultaneously reflected on Bell Quantum Hyper-Point EF in Planck Space. More generally, any quantum experiment in 4D spacetime is always reflected simultaneously on the quantum state’s Bell Quantum Hyper-Point in Planck Space. |

| 47 | Double-slit experiments describe a quantum state by its wave function rather than the considerably more amorphous terms “charge density” or “energy content.” Nevertheless, since all quantum states are real if an electron passes through slits A and B, the charge density, and the energy content of the electron, however ill-defined after it has passed through slits A and B, must also do so. See (Sebens C. T., 2021). |

| 48 | The “which way” monitoring experiment is based upon the example discussed in (Maudlin, 2019). |

| 49 | (Lewis, 2016, pp. 72-107). |

| 50 | In Planck Space, a single Bell Quantum Hyper-Point is neither space-like separated nor a separable system. See Sections 5.1 and 5.2 below. See also (Ney, 2021, pp. 112-128); (Howard, 1985, p. 197). |

| 51 | For a detailed discussion, see (Ney, 2021). |

| 52 | The unobservable Universe is considerably larger than the observable universe and may be infinite. |

| 53 | Although decoherence extensively considers environmental triggers and the loss of coherence rather than a specific quantum collapse mechanism, the Dual Ontology conjecture supports a very specific collapse mechanism initiated exclusively by 4D spacetime Physical Interactions. |

| 54 | No assumptions are made regarding dark matter or dark energy. |

| 55 | See also (Licata & Chiatti, 2019). |

| 56 | Although physical triggers such as nuclear interactions on the sun may be statistically determinable, individual quantum state collapses are still time and location-dependent. |

| 57 | The collapse rate of individual quantum states on the sun is directly related to temperature and location. |

| 58 | Humans can, at will, use a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to control and precisely vary the collapse rate of electrons. |

| 59 | (Bassi, et al., 2012). |

| 60 | (Ghirardi, 2004, p. 406). |

| 61 | Note that the Dual Ontology conjecture conflicts with mathematical models that describe quantum state collapse to a single dimensionless point, a Dirac delta function, or an eigenstate of position with a single discrete value. |

| 62 | From the perspective of the Dual Ontology conjecture, "The problem is that mathematics has become too dominant in physics. We have become so focused on finding mathematical descriptions of nature that we have forgotten to ask if these descriptions are actually true. We have become so entranced by the beauty of mathematics that we have lost sight of the goal of physics, which is to understand the real world." (Hossenfelder, 2018, p. 8). “Physics is not mathematics, and mathematics is not physics.” (Feynman, 1985, p. 55). |

| 63 | (Bell, 2004, p. 171); See also (Norsen, 2011, p. 1216). |

| 64 | The terminology that describes 4D spacetime may confirm Ludwig Wittgenstein’s concern that “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.” (Wittgenstein, 1922, p. 74). |

| 65 | Although the term “non-separable” has multiple definitions, a stronger version of that term holds that “…the non-separability of states is the claim that spatio-temporal separation is not a sufficient condition for the individuating systems themselves, that under certain circumstances the contents of two spatio-temporally separated regions of space-time constitute just a single system”. (Howard, 1989). For a slightly different perspective, see (Ney, 2016). Einstein’s primary concern was not with non-separability per se but with the possibility that non-separability implied a violation of his theory of Special Relativity. (Howard, 1985, pp. 172-173); (Howard, 1989, p. 232). |

| 66 | See also (Ney, 2016, 2021). |

| 67 | The non-separability of a Bell Quantum Hyper-Point addresses a concern raised by Einstein. Einstein questioned whether spatially separated quantum states in 4D spacetime had an independent reality. (Wiseman, 2006). The existence of a single ultra-high dimensional Bell Quantum Hyper-Point would prove two points. First, space-like quantum states separated in 4D spacetime are “real,” and second, they are not physically independent. |

| 68 | See (Maudlin, 2011, pp. 21-22). |

| 69 | The ability of a Bell Quantum Hyper-Point to maintain a “quantum connection” also answers the self-interference puzzle outlined in (Gao, 2020). An electron’s Bell Quantum Hyper-Point contains all of the information regarding an electron’s charge distribution regardless of whether the electron is or is not space-like separated in 4D spacetime. The electron’s Bell Quantum Hyper-Point not only contains the charge distribution of the electron, but it also quantum discriminates and is non-attenuated. In this sense, all electrons are not the same. The electron’s Bell Quantum Hyper-point does not interfere with itself. See also (Sebens, 2021, 2022); (Wechsler S. D., 2021). |

| 70 | (Brunner et al., 2014). |

| 71 | (Goldstein et al., 2011); (Maudlin, 2014, p. 21); See also (Bell & Gao, 2016). |

| 72 | See (Maudlin, 2011, pp. 53, Note 1). |

| 73 | (Ney, 2021, p. 96). See (Allori, 2022) regarding different uses of the term “non-local” in Einstein/de Broglie Box experiments. |

| 74 | See Banerjee et al. 2016: “We conclude that the problem of time in quantum theory is intimately connected with the vexing issue of quantum non-locality and acausality in entangled states. Addressing the former compels us to revise our notions of space-time structure, which in turn provides a resolution for the latter.” |

| 75 | See also (Genovese, 2023). |

| 76 | Stated somewhat differently, Planck Space is “extra” local. |

| 77 | See also (Ney, 2021 Sections 3.7 - 3.8). |

| 78 | See also (Penrose, 1997, p. 137): “My own view is that, to understand quantum non-locality, we shall require a radical new theory. This theory will not just be a slight modification of quantum mechanics but something as different from standard quantum mechanics as General Relativity is different from Newtonian gravity. It would have to be something which has a completely different conceptual framework. In this picture, quantum non-locality would be built into the theory”. |

| 79 | (Maudlin. 2011, p. 185). |

| 80 | The mass of a body is always reference frame-dependent. See generally (Maudlin T., 2011, pp. 58-64). |

| 81 | OpenAI (2023). Background information on Special Relativity. |

| 82 | See (Bahrami, et al., 2015); (Doyle, 2014); (Lucia & Grisolia, 2022). |

| 83 | (Albert D. Z., 2000, pp. 150-162); (Doyle, 2014). |

| 84 | See generally (Price, 2004). |

| 85 | See also (Snyder, 2000) Footnote 1: “Generally, this irreversibility means that it is highly unlikely that the physical interaction that is the measurement could occur in the opposite direction of time to the one in which it is occurring or has occurred.” |

| 86 | Moreover, the Bell Identity does not support path reversibility. Instead, it simply posits that the Bell Quantum Spheres comprising the Bell Quantum Hyper-Point z1 in Planck Space are identical to those comprising Bell Quantum Field z1 on Mars and the Bell Quantum Spheres comprising Bell Quantum Hyper-Point z2 in Planck Space are identical to those comprising Bell Quantum Field z2 on Earth. |

| 87 | For a general introduction to quantum cosmology, see (Bojowald, 2015). |

| 88 | Including Type Ia Supernovae Observations, Hubble's Law and Redshift Observations, Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, Galaxy Redshift Surveys, Stellar Evolution Models, and Globular Cluster Age Estimates. |

| 89 | See generally (Davies, 1994); (Aghanim, 2018); Background source. OpenAI (2023). |

| 90 | The FLRW metric also assumes a homogeneous and isometric spatial structure. |

| 91 | “The Planck satellite data reported in 2013 … shows with high precision that we live in a remarkably simple universe. The measured spatial curvature is small; the spectrum of fluctuations is nearly scale-invariant; there is a small spectral tilt, consistent with there having been a simple dynamical mechanism that caused the smoothing and flattening; and the fluctuations are nearly Gaussian, eliminating exotic and complicated dynamical possibilities, such as inflationary models with noncanonical kinetic energy and multiple fields.” (Ijjas et al., 2013). |

| 92 | OpenAI (2023). Background on 4D spacetime’s heat death. |

| 93 | Changes may still occur at the microstate level. |

| 94 | Note that the terms “spatial curvature” and “spatial isometry” do not apply to an ultra-high dimensional Planck Space without space, volume, or distance. |

| 95 | See section 4.3 above. |

| 96 | The collapse of the Planck Energy Hyper-Point and the reduction in the number of Planck Spheres that comprise the new 4D Energy Field does not involve the destruction or localization of the Planck Spheres that comprise Planck Space, nor does it affect the SOAN. Although the energy content of the 4D Energy Field and the Planck Energy Hyper-Point are localized at t = 0, Planck Spheres and the SOAN continue forming an ultra-high dimensional (3 x N) space. |

| 97 | The collapse of the Planck Energy Hyper-Point and the generalized localization of 4D spacetime at t = 0 differs in two important respects from the collapse of a single or N-body quantum state. First, the collapse includes all of the energy content of the Planck Energy Hyper-Point, including, without limitation, dark energy. Second, the collapse generally localizes all of 4D spacetime without regard to a specific subset of Planck Spheres. |

| 98 | See (Melia, 2023) regarding the cosmological principle and the constant expansion rate of 4D spacetime. |

| 99 | The Dual Ontology conjecture also posits that the ubiquity of quantum state collapse plays a central role in the existence of the anisotropies and inhomogeneities at the last scattering of the CMB and the formation of the large-scale structure of 4D spacetime. See generally (Le´on et al., 2014); (Perez et al., 2006); (Sudarsky, 2010). |

| 100 | The theory of General Relativity regards the expansion of spacetime as an intrinsic process rather than an extrinsic expansion. Although the vast majority of the Planck Spheres that comprise all of Planck Space at t =0 are extrinsic to 4D spacetime, the existence of an ultra-high dimensional Planck Space composed of Planck Spheres does not appear to violate General Relativity. |

| 101 | See (Azhar & Loeb, 2021) regarding explanatory depth. (Adams, 2019); (Wolf & Thebault, 2022). |

| 102 | (Wald, 2005): “[T]he presently observed universe should not merely be a (highly unlikely) possibility that is allowed in the model but rather should be a prediction of the model.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).