1. Introduction

1.1. Preservation of historical memory and cultural identity

The preservation of historical memory and cultural identity is crucial for community development, cultural tourism, and sustainability. Cities with historical and cultural heritage attract tourism, driving economic and social development while respecting their history and culture. The conservation of sites and historical monuments is fundamental for understanding the evolution of the city [

1].

The conservation of historical memory includes tangible elements and the compilation of personal testimonies through interviews, documents, and photographs, contributing to archives and museums. These narratives enrich historical understanding and reinforce cultural identity, while cultural preservation promotes traditions and education to maintain identity among future generations [

1].

1.2. Historical Context: The air raid shelters of the Spanish Civil War in Alicante and the Second World Wa

The failed coup d'état of 1936 in Spain against the Government of the Second Republic initiated a civil war and a dictatorship until 1975 under the orders of Francisco Franco. During the conflict (1936-1939), Spain experienced bombings from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, resulting in over 500,000 deaths and devastation, especially in coastal cities like Alicante, a strategic enclave[

2,

3], being the last province to be conquered.

Since November 1936, Alicante faced intense bombings, including the significant '8-hour bombing' on November 28. Faced with a shortage of air raid shelters, they were constructed in densely populated and strategic areas, equipped with surveillance systems, alarms, and telephone communications. The distribution of these shelters was based on population density and proximity to essential services[

2]. By August 1937, Alicante had 41 shelters, with a capacity for 24,020 people[

3]. The increase in number, quality, and capacity of the shelters during the war reflects the escalation of bombings, especially in 1938, marked by the attack on the Central Market on May 25. This event drove an improvement in the city's organizational capacity for defense, resulting in the construction of nearly a hundred shelters [

3].

The air raid shelters were specifically designed to protect the civilian population from bombings. For instance, a study documents the design of private air raid shelters to safeguard the civilian population, analyzing the materials, construction, and structural system of these shelters during the Spanish Civil War [

4].

During the Second World War, a study by the Architectural Research Group evaluated the effectiveness of various air raid shelters, also during the Spanish Civil War, focusing on experiences from Great Britain and Spain. It highlighted their significance in civil protection, symbolizing resistance and population survival [

5,

6].

1.3. Study Objectives

This study focuses on analyzing the contribution of the rehabilitation of air raid shelters to the preservation of intangible cultural heritage in Alicante, Spain. It involves investigating their role as testimonies of the Spanish Civil War, examining interviews with 'children of the war' to understand how their restoration and opening to the public help maintain historical memory and local cultural identity. Furthermore, it will evaluate the impact of public management on the rehabilitation and promotion of their history and culture, including the analysis of financial decisions, community involvement, and strategies to promote cultural tourism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

The research approach used in this study is of a mixed nature, combining both primary and secondary data collection [

7]. This mixed methodology allows for a comprehensive approach to the various aspects related to the rehabilitation of air raid shelters from the Spanish Civil War in Alicante[

3] and their impact on the preservation and promotion of intangible cultural heritage [

8].

With regards to the collection of primary data, interviews were conducted with witnesses of the Spanish Civil War who had direct experience in air raid shelters[

9,

10]. These interviews were conducted in a structured manner, following a set of previously established questions, aimed at obtaining relevant and comparable data.

On the other hand, the collection of secondary data was based on documentary and bibliographic sources. Historical documents, restoration reports, academic studies, and other resources were reviewed to provide contextual information about the Spanish Civil War, the architecture of air raid shelters [

3], and public management in the rehabilitation of these spaces [

11].

The analysis of the collected data was carried out systematically and rigorously, using qualitative analysis techniques[

12,

13]. Patterns, trends, and relationships among the data were sought to address the research objectives. The obtained results are presented clearly and concisely, supported by empirical evidence and contextualized within the existing theoretical framework using hermeneutic analysis [

14,

15,

16].

In the realm of interpretative qualitative research, hermeneutics, focused on analyzing the cultural context of texts and cultural expressions, plays a crucial role [

17]. Within this context, the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) stands out as a qualitatively significant method [

18,

19,

20]. Within the framework of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the selection of interviews has been conducted for meticulous analysis using the Atlas.ti software. Combining textual, contextual, and cultural analysis, it concludes with a comprehensive hermeneutic interpretation.

2.1. Primary Data Collection: Interviews with War Witnesses and Hermeneutic Analysis

This research, therefore, will use a hermeneutic approach to analyze interviews related to the air raid shelters of the Spanish Civil War in Alicante. It will explore personal perceptions and emotions, such as fear and uncertainty, and daily life under wartime conditions to understand the human impact of the shelters. Changes in routines and urban structures will be examined, along with the interaction with the physical space of the shelters, and the long-term emotional and psychological impact. Furthermore, it will study how these narratives contribute to historical memory and the perception of the shelters, seeking interpretations beyond the explicit.

Therefore, to significantly enrich the hermeneutic analysis in the context of our study on the air raid shelters of the Spanish Civil War, it is necessary to address the following issues:

Cultural Semiotics: This approach is useful for unraveling the meanings of symbols and metaphors in the interviewee's narratives [

21].

Cultural Comparison: Comparing the interview narratives with other perceptions and expectations of that era [

22] can provide a more comprehensive insight into how the shelters were seen and experienced in different cultural and social contexts.

Hermeneutics Proper: On one hand, Contextual Interpretation, which is an essential approach to understanding testimonies in their historical and cultural context [

23].

On the other hand, Critical Reflection: The questioning of biases will be analysed, as it is crucial to be aware of our own prejudices and perspectives when analysing these interviews [

24].

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) focuses on exploring how individuals interpret and understand their significant experiences. [

18,

19,

25], being particularly useful in exploring how individuals perceive and comprehend events and phenomena, thus allowing for a deep understanding of their subjective experiences [

26,

27,

28].

3. Results

3.1. Hermeneutic Analysis of Interviews with People Who Lived Through the War

Based on the aforementioned methodology, we proceeded to conduct a hermeneutic analysis of a series of interviews with elderly individuals who, during the Spanish Civil War, were children in the city of Alicante. In this work, due to space constraints, we will only present the first of seven interviews. We will extensively analyze this interview hermeneutically to demonstrate its high scientific potential: Interview with a woman from the San Antón neighbourhood. Shelter gardens and Central Market bombing.

Voice 0:

The shelter on Calle La Huerta. Who made it? Did the neighbors make it or did someone come to do it?

Voice 1:

There was one that the neighbors made, which was the one we entered on the slopes of the castle, that's where I took refuge. The neighbors made that one. But the real shelter, the one on Calle La Huerta, was made by the City Council. They would have done it because there were refugees in many streets.

Voice 0:

And for the children, were they given instructions on what to do when the sirens sounded, or did each child already know what to do?

Voice 1:

I don't know because I used to run to the shelter. However, something happened to me during a bombing. After a short time, a few days later, there was another bombing, and a bomb fell on Calle La Huerta, right on the shelter's door. There was a relative of my sister's. Well, it was as if he were mine too, this boy. They had three children, two boys, yes, two boys and a girl. The woman had given birth two days before, so they were already four. And she tells him: 'You go ahead with the three, and I'll take care of the baby girl I had just given birth to, and I'll follow you while she was getting ready to leave, as she had just given birth.' Her husband went to the shelter, unfortunately, a bomb fell right at the entrance of the shelter where they were waiting, killing the three children and injuring the husband. No, not the husband, the three children. The husband became disabled because he spent a long time in the hospital, losing his memory. So he went crazy because he was holding one of his sons and had two others by the hand, but they couldn't find one of them, Pedrín. After everything passed, and things calmed down, they started looking to see if there were any wounded or dead. One of the children was here, near the shelter, but they were outside, on the street. And here, there were houses too. Well, the boy they couldn't find was up on a roof, a more handsome boy! He was whole, a piece of shrapnel hit him there (in the head), and I know because I saw it.

Voice 0:

What can you tell me about the terrible bombing on May 25, 1938, the massacre caused by that bombing at the Central Market of Alicante, which killed more than 300 people instantly and more than a thousand in the days that followed, especially women, children, and the elderly.

Voice 1:

Yes, on the twenty-fifth of May, all the doctors, myself included, and another friend of mine, who were always together as we lived in the San Antón neighbourhood, very close to the market, we approached to see what had happened. 'There, look!' Toni, who worked at the port. This man worked at the port and that day was working. Like the rest of the men, they wore long underpants with a hem where they tied food inside and then wore their trousers on top. So they used to put chickpeas that they brought from the port in there and took it home. This boy already had his underpants full of chickpeas because he was coming from work. While he was walking down San Vicente Street, the bombing hit him and killed him. He was whole, and all us girls said, 'Let's go see if we find Antonio!' And we walked to the cemetery. They were coming along the path with the cypresses. There were small houses there, small houses for the peasants for work and such, but at that time, if someone had a relative there, they would go to live or sleep there because we believed they wouldn't bomb there, and we would sleep there. We stopped taking refuge in the shelter and went there to sleep. And when the bombing happened, the girl says, 'Let's go to the cemetery to see how they bring the dead and see if we can find Antonio.' We had the courage to be there, on the path where the dead were being carried in stretchers and carts, watching. And I said, 'Look, look, Antonio.' And the chickpeas he had in his pants were still falling. That's how it was.

3.2. Integration of Cultural Semiotics in Perceptions and Feelings about the Shelters

3.2.1. Shelters as Symbols of Tragedy and Loss:

The interviewee's account of the bombing and tragic losses in the shelter on Calle La Huerta reflects how these spaces, meant to be sanctuaries of safety, become symbols of tragedy and loss. This duality in the perception of shelters illustrates the unpredictable and cruel nature of war.

3.2.2. The Shelters in the Community Context:

The mention that neighbors built some shelters highlights community solidarity and collective effort in times of crisis. These shelters represent not only physical places of protection but also the spirit of cooperation and mutual support among neighbors, a key element of resistance and survival during the war.

3.2.3. The Impact of Sirens and Bombings:

The description of the sirens and bombings highlights the constant threat and fear that characterized life during the war. The sirens become a symbol of imminent danger, marking the transition from everyday life to a state of alert and emergency.

3.2.4. The Shelters and the Loss of Innocence:

The experience of children in shelters, especially in the context of bombings, reflects a loss of innocence and an abrupt introduction to the reality of war. The description of how children learned to seek refuge for themselves underscores how even the youngest were forced to adapt to the harsh realities of the conflict.

3.2.5. Construction of the Cultural Meaning of Shelters:

These narratives enrich the cultural meaning of shelters, extending it beyond their physical function. They transform into complex symbols that encapsulate the experience of war, including aspects of community, fear, survival, and tragedy. These personal stories provide a deeper understanding of life during the war and the importance of preserving these accounts in historical memory.

3.3. Cultural Comparison and Daily Life During the War

3.3.1. Cultural Expectations vs. the Reality of War:

During the Spanish Civil War, cultural expectations of safety and normalcy at home were drastically altered, as reflected in the interview. Shelters, which in normal times might not be necessary, became an essential part of daily life. This contrasts with the usual perception of life in peacetime, where safety in one's own home is taken for granted.

3.3.2. Life in Shelters:

The narrative about life in shelters and the response to bombings illustrates a forced adaptation to a new reality. The necessity for even children to understand and react to the sirens shows how war invaded every aspect of life, compelling continuous adaptation to a persistent threat.

3.3.3. Community Response to the War:

The mention of shelters built by neighbors highlights an important aspect of the culture of the time: solidarity and community cooperation in times of crisis. This may contrast with contemporary perceptions of individualism or self-sufficiency, emphasizing how extreme circumstances can strengthen community bonds.

3.3.4. Impact of Bombings on Urban Perception:

The experience of bombings in urban areas such as the Central Market of Alicante changed the perception of spaces that are normally considered safe or neutral. These tragic events altered how urban spaces were experienced and perceived, injecting a sense of fear and caution into everyday life.

3.3.5. Change in Family and Social Dynamics:

The personal stories of loss and survival reflect how war altered family and social dynamics. The war imposed a significant emotional and psychological burden, affecting relationships and social interaction within communities.

3.4. Contextual Interpretation of Changes in Routine and Urban Infrastructure

3.4.1. Transformation of Daily Routines:

The interview reveals how daily routines were profoundly affected by the war. The need to rush to shelters at the sound of sirens and the experience of bombings near places like markets, traditionally considered safe, show a significant disruption of daily life. This reflects how the war imposed a constant state of alert and a change in normal activities, replacing the everyday with a new 'normalcy' marked by urgency and danger.

3.4.2. Reconfiguration of the Urban Landscape:

The bombings and construction of shelters altered the urban landscape of cities like Alicante. Spaces that were once centers of community and commercial life became areas of risk and destruction. This physical reconfiguration of the urban environment symbolizes the invasion of war into all aspects of city life.

3.4.3. Impact on Infrastructure:

The destruction caused by bombings and the need to construct shelters reveal how urban infrastructure was adapted or damaged in response to the conflict. This not only affected the architecture and design of the city but also how inhabitants interacted with their environment, altering movement patterns and areas of activity.

3.4.4. Changes in Social and Community Dynamics:

The construction of shelters by neighbors and the collective response to bombings show a strengthening of community bonds. These dynamics reflect how, in times of crisis, communities can come together to support each other, contrasting with interactions in times of peace.

3.4.5. Perception of Security and Vulnerability:

The experiences recounted in the interview underscore a changing perception of security and vulnerability within the urban environment. Familiar and everyday places, such as streets and markets, were now perceived as potentially dangerous, transforming the experience of living in the city.

3.5. Reconstructing Meaning in the Relationship with the Physical Space of Shelters

3.5.1. Shelters as Spaces of Protection and Tragedy:

The interview describes the shelters not only as places of physical protection but also as scenes of personal and collective tragedies. This duality underscores how shelters, despite their purpose of safeguarding life, couldn't always fully protect from the horrors of war. Therefore, the shelters become complex symbols encapsulating both security and vulnerability.

3.5.2. The Construction of Shelters and the Community:

The mention of shelters built by neighbors and others provided by the local council reflects different forms of community and governmental responses to the crisis. These efforts showcase how the community and local authorities sought to adapt to the imminent threat, emphasizing the interaction between individual initiative and collective action in times of conflict.

3.5.3. Emotional Impact and Personal Experience:

The interviewee's narrative, encompassing stories of loss and how children learned to seek shelter, reveals the emotional impact and psychological burden associated with these spaces. The shelters, in this sense, are remembered not only for their protective function but also for the intense, often traumatic experiences they harbored.

3.5.4. Shelters in the Urban and War Context:

The integration of shelters into the urban landscape during the Spanish Civil War altered how inhabitants interacted with their surroundings. The shelters became a crucial part of the urban fabric, changing the perception and utilization of space in the city.

3.5.5. The preservation of historical memory and the significance of shelters:

These descriptions of the shelters enrich historical memory, providing a deeper understanding of the everyday experience during the war. They offer a valuable perspective on human resilience, adaptability, and the emotional cost of the conflict, aspects that are fundamental for a comprehensive understanding of history.

3.6. Memory of History, Critical Reflection, and Present-day

3.6.1. Enrichment of Historical Memory:

The interview contributes personal stories and experiences to the historical memory of the Spanish Civil War, complementing the official history and historical records with specific human experiences. These personal testimonies offer a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective on the impact of the war on people's daily lives, beyond political and military events.

3.6.2. Critical reflection on the interpretation:

That's a really important aspect to consider when interpreting historical testimonies. It's vital to approach these interviews with an open mind, understanding how our own biases and contemporary viewpoints might influence our understanding of the past. Striving for objectivity and empathy allows us to comprehend these experiences within their specific historical and cultural contexts, ensuring a more accurate interpretation of the past.

3.6.3. Current Relevance of Testimonials:

In the current context, these testimonies hold significant value in terms of education and historical awareness. They provide lessons about the human impacts of war and the importance of collective memory to prevent repeating past mistakes. These personal stories can foster a deeper understanding of the consequences of past and present conflicts, offering valuable perspectives in a world where similar challenges remain relevant.

3.6.4. Impact on Collective Memory and Lessons Learned:

Keeping the memory of individual experiences during the war alive contributes to a collective understanding of history and helps forge a shared cultural identity. This is crucial for future generations seeking to understand the legacy of conflicts such as the Spanish Civil War.

Reflecting on these narratives can promote a dialogue on how societies can learn from their past, especially in terms of resilience, adaptation, and solidarity in the face of adversities.

3.7. Emotional and Psychological Long-Term Impact with Questioning of Biases

3.7.1. Identification of Emotional and Psychological Impact:

The interview reveals a profound emotional and psychological impact stemming from living under constant threat during the war. Stories of tragic losses, such as those of the children in the bombed shelter, highlight the trauma and grief that affected individuals. This account underscores how traumatic events can leave lasting scars, impacting mental and emotional health.

3.7.2. Challenging Personal Biases:

When analyzing these narratives, it's important to acknowledge and challenge any personal biases, including preconceived notions about resilience and people's ability to cope with trauma. It's crucial not to downplay the emotional impact of these experiences or assume that individuals simply "get over" such events.

We should avoid projecting contemporary norms of understanding trauma and mental health onto past experiences, recognizing that ways of processing and expressing pain can vary based on cultural and temporal contexts.

3.7.3. Influence of Cultural and Social Experiences:

The experiences and narratives of the interviewee are shaped by the cultural and social context of the time. Cultural norms about expressing grief, mourning, and resilience, as well as the societal expectations of that era, may have influenced how individuals experienced and subsequently recalled the war.

Understanding and managing trauma in the context of the Spanish Civil War might have differed from current expectations, which should be considered when interpreting these testimonies.

3.7.4. Reflection on Perspectives Shaped by Experiences:

Acknowledging that the interviewee's perspectives are influenced by their cultural and social environment helps contextualize their narratives. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of their experiences and how these were shaped by the environment in which they lived.

Reflecting on these narratives within their historical and cultural context provides a better understanding of the emotional and psychological impact of war, highlighting the complexity of human responses in extreme situations.

3.8. Perspective on the Rehabilitation of Shelters and Their Current Cultural Relevance

3.8.1. Opinions and Emotions Towards Shelters:

The interview reflects a complex mix of emotions towards the shelters: on one hand, they are remembered as places of refuge and community solidarity; on the other, as scenes of tragedies and profound losses. This duality underscores the importance of shelters not only as physical structures but also as spaces laden with historical and emotional memory.

3.8.2. Rehabilitation of Shelters in the Current Context:

The preservation and rehabilitation of shelters in the current context can serve as a powerful means to remember and educate about the Spanish Civil War. These spaces, transformed into museums or memorial sites, can help newer generations understand the complexities and human impact of the conflict.

The way these shelters are treated today reflects society's attitudes towards its past and the importance given to historical memory. Preserving these sites can indicate a commitment to truth, recognition of past suffering, and the necessity to learn from history.

3.8.3. Importance of Preserving Memory Sites:

Maintaining shelters as memory sites contributes to a more comprehensive historical narrative, including not only political and military events but also personal and collective experiences [

29]. These places are tangible testimonies to history, fostering a deeper and empathetic understanding of the past.

Preserving these spaces can promote reflection on relevant contemporary issues, such as the effects of war, resilience in times of crisis, and the importance of peace and solidarity.

3.8.4. Cultural and Educational Relevance:

The rehabilitation of shelters has significant educational value, providing a tangible context for teaching about war, its consequences, and the importance of avoiding future conflicts. These spaces can serve as tools to foster critical and constructive dialogue about history and its lessons.

3.9. Conclusions from the hermeneutic analysis

The interviews on the Spanish Civil War reveal a radical transformation of daily life, marked by changes in routines, childhood, urban space, and survival strategies. A lasting emotional and psychological impact is observed, highlighting the importance of addressing the psychological aftermath of conflicts. The narratives emphasize human resilience and adaptation, demonstrating solidarity and mutual support in the shelters, which become symbols of the war experience and essential sites of historical memory. The war altered social and community dynamics, reflecting how crises can redefine social interactions. These experiences provide lessons on crisis management and solidarity, enriching the contemporary understanding of similar challenges. These personal accounts complement official history, offering a more human and nuanced perspective of historical events.

3.10. Rehabilitation of Air-Raid Shelters

Under the ERDF Operational Program "Sustainable Growth 2014-2020," the Alicante City Council implemented the DUSI Strategy "Las Cigarreras Area" for sustainable urban development, co-financed by the European Commission. This project focused on the rehabilitation of air-raid shelters from the Civil War in various neighborhoods, improving their accessibility and contributing to cultural and touristic revitalization. The DUSI Strategy, aligned with the ERDF Thematic Objective 6, seeks to protect and develop cultural and natural heritage. With a budget of €600,000 and a five-year timeline, the project included the rehabilitation of shelters and activities to reconstruct Historical Memory, aiming to increase sustainable tourism and improve cultural heritage. The first phase involved the planning of the opening and accessibility to six shelters in the Alicante DUSI area.

Figure 1.

The Project was to be carried out on the following six shelters:

3.11. Strategies for promoting cultural tourism.

Between 2021 and 2022, several activities took place in refurbished anti-aircraft shelters, including installations such as videomapping in Tordera, exhibitions about the history of water in Palmeretes, and historical photographs in Tabacalera, accompanied by a detailed model. Theatrical visits were also conducted.

Figure 4. These initiatives contribute to the revitalisation and promotion of historical heritage through interactive and educational tools.

Specific events have taken place within the rehabilitated shelters, including theatre, music, poetry, dance at Tabacalera, and architectural performances at Marvá. These activities are part of a strategy to enrich the cultural and educational experience, diversifying artistic expressions and enhancing historical heritage. Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Micro-theatre in the anteroom of the tobacco factory air-raid shelter, performed by Vicente de Ramón Producciones.

Figure 6.

Micro-theatre in the anteroom of the tobacco factory air-raid shelter, performed by Vicente de Ramón Producciones.

Within the EDUSI project, guided tours to air-raid shelters and historical sites were organized, some of which were theatrical, by the Professional Association of Official Guides of the Valencian Community. Short films about significant local events were produced, and educational materials were published, including a comic book for young people. Additionally, a website (

https://refugiosalicante360.com) was launched to provide a virtual and immersive experience of the shelters, featuring photographs, floor plans, and 360-degree views, expanding access to a global audience.

Figure 6.

At the Marvá shelter, students, particularly from the 2nd GIAT of the IES Miguel Hernández, have developed guided tours and educational exhibitions, including one about the Holocaust.

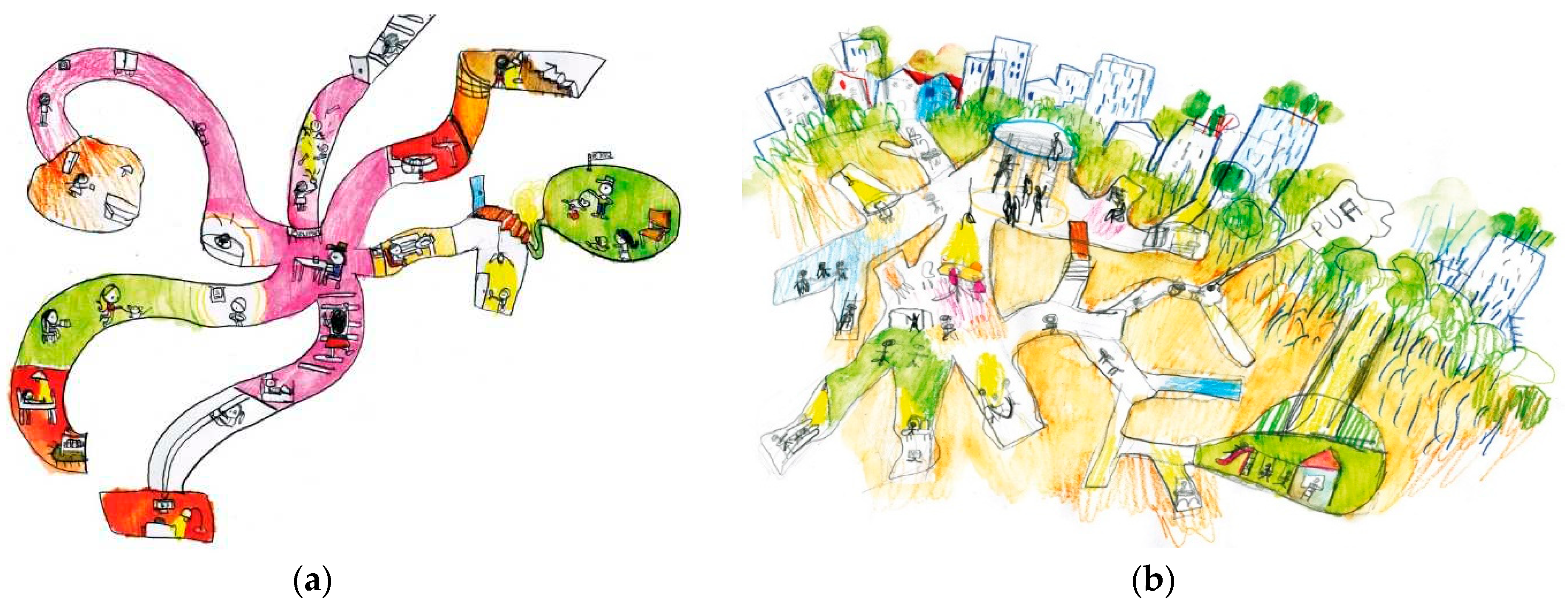

3.12. The Cultural Heritage of Memory (PCM) as a driving element, also for the awareness and citizen participation of adults and children.

Under the DUSI strategy, two objectives were established: to protect and develop cultural and natural heritage in tourist urban areas and to revitalize the area socially, economically, and physically. Faced with the disconnection between residents and their heritage, and the lack of collective identity, a plan for socialization and community involvement was implemented, including the participatory reconstruction of the historical narrative and consolidation of collective identity. This plan incorporated environmental, historical, and sustainable workshops and creative activities for children, focused on connecting them with Alicante's heritage through imaginary characters based on heritage elements.

Figure 7.

4. Discussion.

4.1. Importance of shelters as promoters of the recovery of the intangible heritage of the Spanish Civil War

Heritage encompasses current interpretations and symbolism about objects, environments, myths, memories, and customs inherited from the past. It constitutes an essential factor in identity formation, especially in societies characterized by their increasing cultural diversity [

29,

30,

31]. The past is crucial in the creation of identity narratives in the present. The significant influence of monuments and cultural landscapes as spaces of cultural heritage is very important. The view of certain places and constructions with historical value has evolved, as well as their function in the formation and reformulation of specific identities [

32]. The air-raid shelters of the Spanish Civil War are an example of this and play a crucial role in the recovery and preservation of the intangible heritage associated with this historical conflict [

2,

3,

33,

34]. These underground spaces, used as refuge by the civilian population during bombings, are tangible witnesses of the experiences of that period, and their rehabilitation and opening to the public allow reliving and understanding the history and culture of that time [

34,

35,

36].

Firstly, the air-raid shelters are places that evoke the protective practices and survival strategies that took place during the Spanish Civil War. These underground spaces represent the resistance and struggle of the civilian population against bombings and the violence of the war[

3]. By rehabilitating and opening these shelters to the public, current and future generations are allowed to learn and understand the strategies used by those who lived during that time, as well as the emotional and psychological impact they had on society[

36,

37].

The air-raid shelters, as sites of memory from the historical period of the Spanish Civil War, their restoration and opening, promote the preservation of memory and cultural identity in Alicante. They enable a connection with the past and an understanding of its influence on current society and culture[

37]. Furthermore, visiting the air-raid shelters can generate a sense of empathy and solidarity with the people who lived through those difficult times, thus fostering appreciation and respect for the intangible heritage of the civil war [

38].

Finally, the rehabilitation of the air-raid shelters and their opening to the public contribute to the promotion of cultural tourism and the dissemination of the history and culture associated with the Spanish Civil War. These spaces become tourist attractions that draw visitors interested in learning and understanding the history and culture of Alicante during the civil war. This, in turn, generates economic and social benefits for the local community, promoting sustainable development and the valorization of its cultural heritage [

33,

37].

4.2. The Upcycling Process: Impact of Public Management in Shelter Rehabilitation¡

The upcycling process, utilized in our project, refers to the creative and sustainable transformation of an existing space to provide it with a new purpose or function. Instead of discarding or demolishing a space, upcycling aims to maximize available resources and minimize environmental impact [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

The air-raid shelters from the Nazi era in Szczecin, Poland, have been recognized as a planning challenge for the city due to their history associated with World War [

39].

The space upcycling process involves rethinking and reusing materials, structures, and existing features of the space in an innovative manner. This may include refurbishing an old building into residences or workspaces, transforming a warehouse into an event space, or revitalizing an abandoned garden into a community park [

44,

45].

Space upcycling can also involve the integration of sustainable technologies, such as installing solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems, or natural ventilation systems, to make the space more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly [

39,

43,

47].

Ultimately, the space upcycling process is a creative and conscious way to breathe new life into an existing space, maximizing available resources, and reducing environmental impact [

49].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R. and S.S.; methodology, P.R. and S.S.; software, S.S.; validation, P.R.; formal analysis, P.R. and S.S.; investigation, P.R. and S.S.; resources, P.R. and S.S.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, P.R. and S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge, 2006; ISBN 9781134368037.

- Rosser, P.; Soriano, R. Alicante En Guerra; Ayuntamiento de Alicante: Alicante, 2018; Vol. 1 y 2;.

- Rosser, P. Bombas Sobre Alicante. Los Diarios de La Guerra y Las Comisiones Internacionales de No Intervención e Inspección de Bombardeos; Universidad de Alicante, 2023; ISBN 9788413022215.

- Guardiola-Villora, A.; Basset-Salom, L.; Pérez-García, A. Private Air-Raid Shelters Designed by the Valencian Architect Joaquín Rieta during the Spanish Civil War. J. Archit. 2021, 26, 286–315. doi:10.1080/13602365.2021.1897646.

- Leaflet - “Air Raid Precautions: Shelters”, World War II, Jan 1942 Available online: https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/1987871 (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Envelope of Documents - Civilian Air Raid Defence Association, Feb 1942 Available online: https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/1991076 (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage publications., 2017;

- Stone, S. UnDoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory; Routledge, 2019; ISBN 9781315397207.

- Crespi, D.R. Fuentes de Contraste y Juego de Espejos. Una Aproximación Metodológica al Estudio de La Experiencia Bélica En La Guerra Civil Española. Huarte de San Juan. Geografía e Historia 2023, 19–38.

- Vázquez, D.G.; Vergés, O.A.; Martín, A.B. Análisis estratégico de un recurso patrimonial territorial: los refugios antiaéreos de la Guerra Civil española en la provincia de Girona (Cataluña). invest. tur 2022, 379–401. doi:10.14198/INTURI2022.23.17.

-

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Preservation, Maintenance and Rehabilitation of Historical Buildings and Structures; Rogério Amoêda, S.L.&. C.P., Ed.; REHAB, 2017; ISBN 9789898734242.

- Maher, C.; Hadfield, M.; Hutchings, M.; de Eyto, A. Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Design Research Approach to Coding Combining NVivo With Traditional Material Methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2018, 17, 1609406918786362. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C. Rapid and Rigorous Qualitative Data Analysis: The “RADaR” Technique for Applied Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917712131. [CrossRef]

- Guarate, Y.C. Análisis de las entrevistas en la investigación cualitativa: Metodología de Demaziére D. y Dubar C. Enferm. investig. 2019, 4, 14–23.

- Carabajo, R.A. Formación de investigadores de las ciencias sociales y humanas en el enfoque fenomenológico hermenéutico (de van manen) en el contexto hispanoamericano. EducXX1 2016, 19. [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.D.; Rodas, S.; Ospina, S.; Restrepo, S.; Avendaño, M. Creencias Sociales y Orientaciones Emocionales Colectivas Sobre La Protesta Social En Ciudadanos de Medellín (Colombia) y Su Área Metropolitana. Investigación & Desarrollo 2023, 31. [CrossRef]

- Muganga, L. The Importance of Hermeneutic Theory in Understanding and Appreciating Interpretive Inquiry as a Methodology. Sex. Res. Social Policy 2016, 6, 65–88.

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, England, 2022; ISBN 9781529753806.

- Smith, J.A.; Nizza, I.E. Essentials of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; Essentials of Qualitative Methods; American Psychological Association: Washington, D.C., DC, 2021; ISBN 9781433835650.

- Roberts, T. Understanding the Research Methodology of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. British Journal of Midwifery 2013, 21, 215–218. [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, S.F. El recurso metalingüístico y la performatividad en la samba. Una propuesta de análisis desde la semiótica cultural. REB 2019, 6, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- de Mariscal, B.L. Viajeros y Transferencia Cultural Gilliam y Flandrau En El México Del Siglo XIX. Revista de Humanidades: Tecnológico de Monterrey 2009.

- Romañá, T.; Saura Carulla, M.; Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Departament de Projectes Arquitectònics Arquitectura Institucional y Pedagogía de Habilitación Social : Interpretación Del Desarrollo de La Arquitectura de Reformatorio En El Contexto Socio Cultural Brasileño, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2014.

- Ramírez, J.P.; Becerra, J.I.R. Recursos culturales y objetos contra-patrimoniales: Apuntes exploratorios sobre las posibilidades de una antropología crítica del patrimonio a partir de la reflexión sobre una práctica religiosa transnacional. Sphera publica: revista de ciencias sociales y de la comunicación 2010, 373–394.

- Smith, J.A.; Breakwell, G.M.; Wright, D.B.; Clark, A.; Weeks, M. Research Methods in Psychology; Sage Publications Ltd, 2012;

- Zaghi, A.E.; Grey, A.; Hain, A.; Syharat, C.M. “It Seems Like I’m Doing Something More Important”—An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the Transformative Impact of Research Experiences for STEM Students with ADHD. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 776. [CrossRef]

- Sak, M.; Gurbuz, N. Unpacking the Negative Side-Effects of Directed Motivational Currents in L2: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Language Teaching Research 2022, 13621688221125996. [CrossRef]

- Rajasinghe, D. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as a Coaching Research Methodology. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice 2020, 13, 176–190. [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2012; ISBN 9781409487609.

- Micic, D.; Ehrlichman, H.; Chen, R.; Ansuini, C.; Begliomini, C.; Ferrari, T.; Castiello, U.; Moustafa, A.A.; Keri, S.; Herzallah, M.M.; et al. Why do we move our eyes while trying to remember? The relationship between non-visual gaze patterns and memory Available online: https://es.zlib-articles.se/book/16554813/0427b8/why-do-we-move-our-eyes-while-trying-to-remember-the-relationship-between-nonvisual-gaze-patterns.html (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Rosser, P. El Concepto de Memoria y La Memoria En Alicante. In Recuperación de la memoria histórica y la identidad colectiva del área de las Cigarreras, Alicante; Rosser, P., Ed.; Ayuntamiento de Alicante, 2020; pp. 5–54.

- Moore, N.; Whelan, Y.; Bullard, L.; Beiter, K.D. Heritage, Memory and the Politics of Identity: New Perspectives on the Cultural Landscape; Heritage, Culture & Identity) Heritage, Culture and Identity; Ashgate Publishing, 2007;

- Avilés, A.B.G.; Millan, M.I.P.; Ruiz, A.L.R. Reuse of Spanish Civil War Air-Raid Shelters in Alicante: The R46 Balmis and R31 Seneca Shelter. In Proceedings of the Defence Sites III: Heritage and Future; WIT Press: Southampton UK, May 4 2016; Vol. 158, pp. 107–116.

- Soler, S.; Rosser., P. Empatizar Con Los Conflictos Bélicos Para Trabajar El ODS 16. Creación de Una Situación de Aprendizaje a Partir de La Simulación Urbana. In Hacia una Educación con basada en las evidencias de la investigación y el desarrollo sostenible; DYKINSON, 2023 ISBN 9788411704274.

- Soler, S.; Rosser, P.; Gavilán, D. La Investigación Del ODS 16 “Paz, Justicia e Instituciones Sólidas”: La Necesidad de Su Integración En La Educación. In Investigación e innovación educativa en contextos diferenciados; DYKINSON, 2023; pp. 499–509 ISBN 9788411705585.

- Soler, S.; Rosser., P. Desafiando Los Límites Del Aprendizaje Histórico: Una Propuesta Educativa Innovadora Basada En La Pedagogía Crítica, Ia y Chatgpt Para Comprender La Guerra Civil Española, La Dictadura Franquista y La Transición Democrática. In Las ciencias sociales, las humanidades y sus expresiones artísticas y culturales: una tríada indisoluble desde un enfoque educativo; Dykinson, 2024 ISBN 9788411705844.

-

Recuperación de La Memoria Histórica y La Identidad Colectiva Del Área de Las Cigarreras, Alicante; Rosser, P., Ed.; Ayuntamiento de Alicante, 2020.

- Broseta Palanca, M.T. Defence Heritage of the Spanish Civil War: Preservation of Air-Raid Shelters in Valencia. Int. J. Herit. Archit. Stud. Repairs Maintence 2017, 1, 624–639. [CrossRef]

- Matacz, P.; Świątek, L. The Unwanted Heritage of Prefabricated Wartime Air Raid Shelters—Underground Space Regeneration Feasibility for Urban Agriculture to Enhance Neighbourhood Community Engagement. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 12238. [CrossRef]

- Le Pavec, A.; Zerhouni, S.; Leduc, N.; Kuzmenko, K.; Brocato, M. Friction Magazine: The Upcycling of Manufacture for Structural Design. Int. J. Space Struct. 2021, 36, 281–293. [CrossRef]

- 유현주; Lee, J. A Study on the Upcycling Marketing Strategy of the Brand Space Design. Journal of Korea Intitute of Spatial Design 2015, 10, 177–188. [CrossRef]

- Kimin yoo; Kim, J.Y.; 김지현 A Study on the Characteristics of Upcycling Space Design from the Perspective of the Spatial Marketing. Journal of Korea Intitute of Spatial Design 2017, 12, 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.; Sbarcea, M.; Panagopoulos, T. Creating Green Space Sustainability through Low-Budget and Upcycling Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1857. [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.Y.; Kim, K.C. A Study on the Characteristics of Upcycling Space Reflecting Newtro Trend Characteristic Focused on Complex Cultural Space -. Journal of Basic Design & Art 2020, 21, 347–358. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R. A Study on the Space Planning of Creative Studio for Upcycling Creators - Focusing on the Case Analysis of the Upcycling Creative Studio -. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2022, 31, 134–146. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. A Study on Space Upcycling Design Characteristics in Retrotopia Concept. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2022, 31, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Lucanto, D.; Nava, C. The Contribution of the Green Responsive Model to the Ecological and Digital Transition in the Built Environment. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Lecture notes in networks and systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 357–377 ISBN 9783031342103.

- Ham, J.; Sunuwar, M. Experiments in Enchantment: Domestic Workers, Upcycling and Social Change. Emot. Space Soc. 2020, 37, 100715. [CrossRef]

- Fivet, C.; Baverel, O. Upcycling Space Structures. Int. J. Space Struct. 2021, 36, 251–252. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).