Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

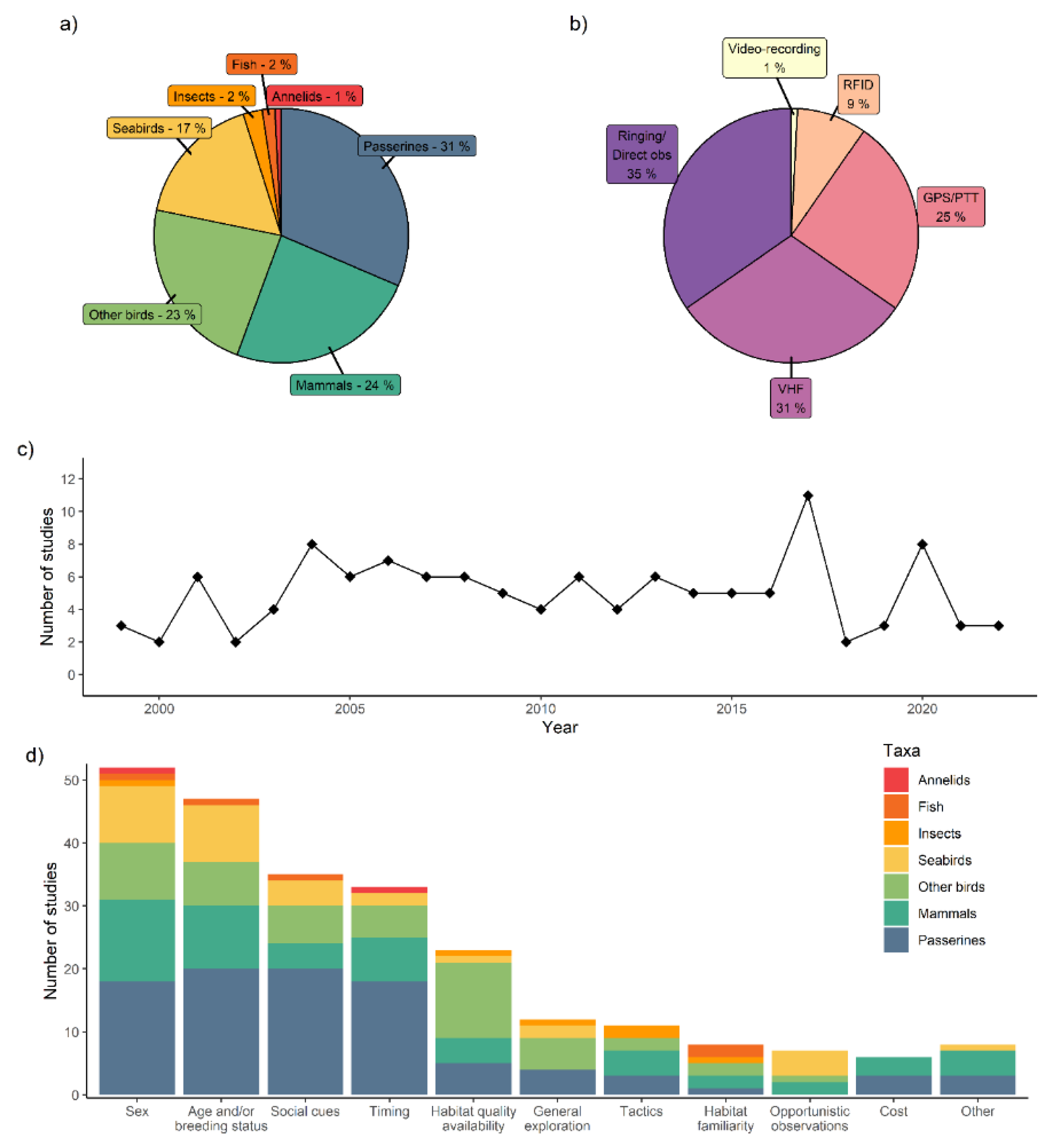

II. Study of Prospecting Movements over the Last Two Decades

II.1. Why? Function of Prospecting for Breeding Habitat Selection

II.2. Who? Classes of Prospectors

II.3. When and What? Timing of Prospecting and Available Cues

II.4. How? Patterns of Prospecting

II.5. How? Costs of Prospecting

III. Future Research Directions

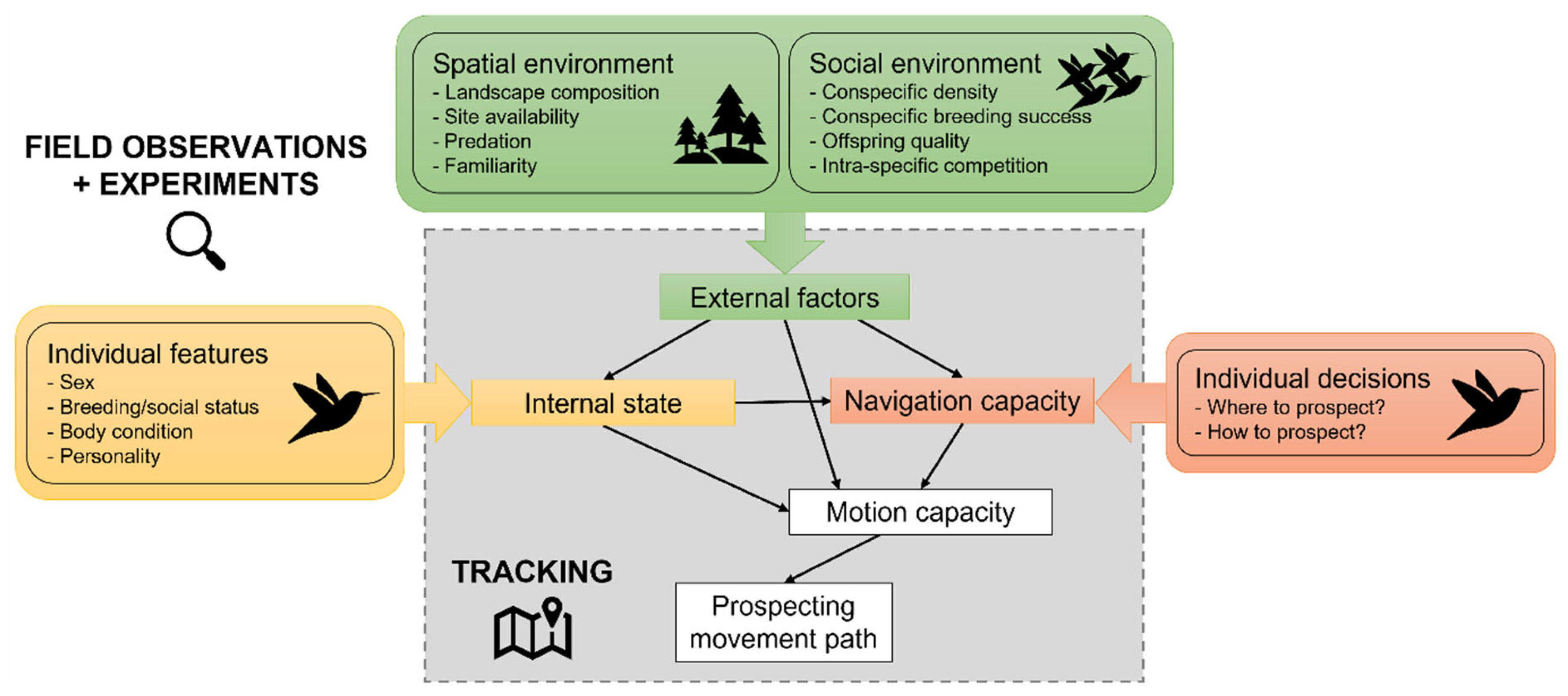

III.1. Prospecting as Both a Behavioural and Movement Process

III.2. How to Fill the Persisting Gaps?

III.3. Prospecting in a Changing World

IV. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Ahlering, M. A.; Arlt, D.; Betts, M. G.; Fletcher, R. J.; Nocera, J. J.; Ward, M. Research needs and recommendations for the use of conspecific-attraction methods in the conservation of migratory songbirds. The Condor 2010, 112, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhein, V.; Kunc, H. P.; Naguib, M. Non–territorial nightingales prospect territories during the dawn chorus. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2004, 271, S167–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt, D.; Pärt, T. Post-breeding information gathering and breeding territory shifts in northern wheatears. Journal of Animal Ecology 2008, 77, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, J. D.; Braithwaite, V. A.; Huntingford, F. A. Spatial Strategies of Wild Atlantic Salmon Parr: Exploration and Settlement in Unfamiliar Areas. Journal of Animal Ecology 1997, 66, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, J.; Ferrer, M. Movements of juvenile Bonelli’s Eagles Aquila fasciata during dispersal. Bird Study 2009, 56, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barve, S.; Hagemeyer, N. D. G.; Winter, R. E.; Chamberlain, S. D.; Koenig, W. D.; Winkler, D. W.; Walters, E. L. Wandering woodpeckers: foray behavior in a social bird. Ecology 2020, 101, e02943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P. H.; Bradley, J. S. The role of intrinsic factors for the recruitment process in long-lived birds. Journal of Ornithology 2007, 148, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, R. V.; Siegel, R. B.; Webb, E. B.; Dillingham, C. P.; Bauer, R. L.; Johnson, M.; Kesler, D. C. Space use, forays, and habitat selection by California Spotted Owls (Strix occidentalis occidentalis) during the breeding season: New insights from high resolution GPS tracking. Forest Ecology and Management 2019, 432, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, S.; Clobert, J.; Danchin, E. The role of public information in ecology and conservation: an emphasis on inadvertent social information. Annals of the New-York Academy of Sciences 2010, 1195, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, D. S.; Vercruijsse, H. J. P.; Stienen, E. W. M.; Vincx, M.; Lens, L. Age of first breeding interacts with pre- and post-recruitment experience in shaping breeding phenology in a long-lived gull. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e82093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulinier, T.; Kada, S.; Ponchon, A.; Dupraz, M.; Dietrich, M.; Gamble, A.; Bourret, V.; Duriez, O.; Bazire, R.; Tornos, J.; Tveraa, T.; Chambert, T.; Garnier, R.; McCoy, K. D. Migration, Prospecting, Dispersal? What Host Movement Matters for Infectious Agent Circulation? Integrative and Comparative Biology 2016, 56, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracis, C.; Bildstein, K. L.; Mueller, T. Revisitation analysis uncovers spatio-temporal patterns in animal movement data. Ecography 2018, 41, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J. S.; Gunn, B. M.; Skira, I. J.; Meathrel, C. E.; Wooller, R. D. Age-dependent prospecting and recruitment to a breeding colony of Short-tailed Shearwaters Puffinus tenuirostris. Ibis 1999, 141, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinzeel, L. W.; van de Pol, M. Site attachment of floaters predicts success in territory acquisition. Behavioral Ecology 2004, 15, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhalter, J. C.; Fefferman, N. H.; Lockwood, J. L. The impact of personality on the success of prospecting behavior in changing landscapes. Current Zoology 2015, 61, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadahía Lorenzo, L.; López-López, P.; Urios, V.; Soutullo, A.; Balmaseda, J. J. Negro. Natal dispersal and recruitment of two Bonelli’s Eagles Aquila fasciata: a four-year satellite tracking study. Acta Ornithologica 2009, 44, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabuig, G.; Ortego, J.; Aparicio, J. M.; Cordero, P. J. Intercolony movements and prospecting behaviour in the colonial lesser kestrel. Animal Behaviour 2010, 79, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campioni, L.; Granadeiro, J. P.; Catry, P. Albatrosses prospect before choosing a home: intrinsic and extrinsic sources of variability in visit rates. Animal Behaviour 2017, 128, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Vorisek, S.; Ritchison, G. Extra-territorial movements by female Indigo Buntings (Passerina cyanea). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 2018, 130, 1032–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazza, M. L.; McDuie, F.; Lorenz, A. A.; Keiter, D.; Yee, J.; Overton, C. T.; Peterson, S. H.; Feldheim, C. L.; Ackerman, J. T. Good prospects: high-resolution telemetry data suggests novel brood site selection behaviour in waterfowl. Animal Behaviour 2020, 164, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choden, K.; Ravon, S.; Epstein, J. H.; Hoem, T.; Furey, N.; Gely, M.; Jolivot, A.; Hul, V.; Neung, C.; Tran, A.; Cappelle, J. Pteropus lylei primarily forages in residential areas in Kandal, Cambodia. Ecology and Evolution 2019, 9, 4181–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaglo, M.; Calhoun, R.; Yanco, S. W.; Wunder, M. B.; Stricker, C. A.; Linkhart, B. D. Evidence of postbreeding prospecting in a long-distance migrant. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clobert, J., M. Baguette, T. G. Benton, and J. M. Bullock. 2012. Dispersal ecology and evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Conradt, L.; Bodsworth, E. J.; Roper, T. J.; Thomas, C. D. Non-random dispersal in the butterfly Maniola jurtina: implications for metapopulation models. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2000, 267, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, N. W.; Marra, P. P. Hidden Long-Distance Movements by a Migratory Bird. Current Biology 2020, 30, 4056–4062.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A. S.; Kesler, D. C. Prospecting behavior and the influenceof forest cover on natal dispersal in aresident bird. Behavioral Ecology 2012, 23, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, D. L.; Monaghan, P.; Gillespie, R.; Dantzer, B.; Duncan, C.; Spence-Jones, H.; Clutton-Brock, T. Rank-Related Contrasts in Longevity Arise from Extra-Group Excursions Not Delayed Senescence in a Cooperative Mammal. Current Biology 2018, 28, 2934–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J. Conspecific Aggression by Beavers (Castor canadensis) in the Sangamon River Basin in Central Illinois: Correlates with Habitat, Age, Sex and Season. The American Midland Naturalist 2015, 173, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, S.; Steifetten, Ø.; Osiejuk, T. S.; Losak, K.; Cygan, J. P. How do birds search for breeding areas at the landscape level? Interpatch movements of male ortolan buntings. Ecography 2006, 29, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall, S. R. X.; Giraldeau, L. A.; Olsson, O.; McNamara, J. M.; Stephens, D. W. Information and its use by animals in evolutionary ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchin, E.; Giraldeau, L. A.; Valone, T. S.; Wagner, R. H. Public information: from nosy neighbors to cultural evolution. Science 2004, 305, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeffe, L.; Focardi, S.; Bonenfant, C.; Hewison, A. J. M.; Morellet, N.; Vanpé, C.; Heurich, M.; Kjellander, P.; Linnell, J. D. C.; Mysterud, A.; Pellerin, M.; Sustr, P.; Urbano, F.; Cagnacci, F. A one night stand? Reproductive excursions of female roe deer as a breeding dispersal tactic. Oecologia 2014, 176, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debeffe, L.; Morellet, N.; Cargnelutti, B.; Lourtet, B.; Coulon, A.; Gaillard, J. M.; Bon, R.; Hewison, A. J. M. Exploration as a key component of natal dispersal: dispersers explore more than philopatric individuals in roe deer. Animal Behaviour 2013, 86, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M. M.; Bartoń, K. A.; Bonte, D.; Travis, J. M. J. Prospecting and dispersal: their eco-evolutionary dynamics and implications for population patterns. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2014, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M.; Ratikainen, I. I.; Kokko, H. Inertia: the discrepancy between individual and common good in dispersal and prospecting behaviour. Biological Reviews 2011, 86, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuel, N.; Conner, L. M.; Miller, K. V.; Chamberlain, M.; Cherry, M.; Tannenbaum, L. Gray fox home range, spatial overlap, mated pair interactions and extra-territorial forays in southwestern Georgia, USA. Wildlife Biology 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dique, D. S.; Thompson, J.; Preece, H. J.; de Villiers, D. L.; Carrick, F. N. Dispersal patterns in a regional koala population in south-east Queensland. Wildlife Research 2003, 30, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doligez, B.; Berthouly, A.; Doligez, D.; Tanner, M.; Saladin, V.; Bonfils, D.; Richner, H. Spatial scale of local breeding habitat quality and adjustment of breeding decisions. Ecology 2008, 89, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doligez, B.; Cadet, C.; Danchin, E.; Boulinier, T. When to use public information for breeding habitat selection? The role of environmental predictability and density-dependance. Animal Behaviour 2003, 66, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doligez, B.; Danchin, E.; Clobert, J.; Gustafsson, L. The use of conspecific reproductive success for breeding habitat selection in a non-colonial, hole-nesting species, the collared flycatcher. Journal of Animal Ecology 1999, 68, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doligez, B.; Pärt, T.; Danchin, E. Prospecting in the collared flycatcher : gathering public information for future breeding habitat selection? Animal Behaviour 2004, 67, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolan, S. P.; Macdonald, D. W. Dispersal and extra-territorial prospecting by slender-tailed meerkats (Suricata suricatta) in the south-western Kalahari. Journal of Zoology 1996, 240, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducros, D.; Morellet, N.; Patin, R.; Atmeh, K.; Debeffe, L.; Cargnelutti, B.; Chaval, Y.; Lourtet, B.; Coulon, A.; Hewison, A. J. M. Beyond dispersal versus philopatry? Alternative behavioural tactics of juvenile roe deer in a heterogeneous landscape. Oikos 2020, 129, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikenaar, C.; Richardson, D. S.; Brouwer, L.; Komdeur, J. Sex biased natal dispersal in a closed, saturated population of Seychelles warblers Acrocephalus sechellensis. Journal of Avian Biology 2008, 39, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.; Krone, O. Movement patterns of the White-tailed Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla): post-fledging behaviour, natal dispersal onset and the role of the natal environment. Ibis 2022, 164, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasciolo, A.; Delgado, M. D. M.; Cortés, G.; Soutullo, Á.; Penteriani, V. Limited prospecting behaviour of juvenile Eagle Owls Bubo bubo during natal dispersal: implications for conservation. Bird Study 2016, 63, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijn, R. C.; Wolf, P.; Courtens, W.; Verstraete, H.; Stienen, E. W. M.; Iliszko, L.; Poot, M. J. M. Post-breeding prospecting trips of adult Sandwich Terns Thalasseus sandvicensis. Bird Study 2014, 61, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J.-M.; Hebblewhite, M.; Loison, A.; Fuller, M.; Powell, R. A.; Basille, M.; Van Moorter, B. Habitat–performance relationships: finding the right metric at a given spatial scale. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2010, 365, 2255–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughran, A.; MacWhite, T.; Mullen, E.; Maher, P.; Kelly, D. J.; Good, M.; Marples, N. M. Dispersal patterns in a medium-density Irish badger population: Implications for understanding the dynamics of tuberculosis transmission. Ecology and Evolution 2019, 9, 13142–13152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P. J. Mating systems, philopatry and dispersal in birds and mammals. Animal Behaviour 1980, 28, 1140–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D. J.; Harrison, J. A.; O’Donoghue, M. Predispersal Movements of Coyote (Canis latrans) Pups in Eastern Maine. Journal of Mammalogy 1991, 72, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughland, D. L.; Larsen, K. W. Exploration correlates with settlement: red squirrel dispersal in contrasting habitats. Journal of Animal Ecology 2004, 73, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honza, M.; Taborsky, B.; Taborsky, M.; Teuschl, Y.; Vogl, W.; Moksnes, A.; Røskaft, E. Behaviour of female common cuckoos, Cuculus canorus, in the vicinity of host nests before and during egg laying: a radiotelemetry study. Animal Behaviour 2002, 64, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, A.; Walker, J.; Taborsky, M. Prospecting precedes dispersal and increases survival chances in cooperatively breeding cichlids. Animal Behaviour 2015, 106, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D. J.; Gaughran, A.; Mullen, E.; MacWhite, T.; Maher, P.; Good, M.; Marples, N. M. Extra Territorial Excursions by European badgers are not limited by age, sex or season. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesler, D. C.; Haig, S. M. Territoriality, Prospecting, and Dispersal in Cooperatively Breeding Micronesian Kingfishers (Todiramphus Cinnamominus Reichenbachii). The Auk 2007, 124, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, S. A.; Bebbington, K.; Hammers, M.; Richardson, D. S.; Komdeur, J. Delayed dispersal and the costs and benefits of different routes to independent breeding in a cooperatively breeding bird. Evolution 2016, 70, 2595–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivelä, S. M.; Seppänen, J.-T.; Ovaskainen, O.; Doligez, B.; Gustafsson, L.; Mönkkönen, M.; Forsman, J. T. The past and the present in decision-making: the use of conspecific and heterospecific cues in nest site selection. Ecology 2014, 95, 3428–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloskowski, J. Win-stay/lose-switch, prospecting-based settlement strategy may not be adaptive under rapid environmental change. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, H.; Lopéz-Sepulcre, A. From individual dispersal to species ranges: perspectives for a changing world. Science 2006, 313, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodzinski, J. J.; Tannenbaum, Lawrence V.; Muller, Lisa I.; Osborn, David A.; Adams, Kent A.; Conner, Mark C.; Ford, W. Mark; Miller, Karl V. Excursive Behaviors by Female White-tailed Deer during Estrus at Two Mid-Atlantic Sites. The American Midland Naturalist 2010, 163, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, J.; Ponchon, A.; Oro, D.; Amadesi, B.; Arizaga, J.; Baccetti, N.; Boulinier, T.; Cecere, J. G.; Corcoran, R. M.; Corman, A.-M.; Enners, L.; Fleishman, A.; Garthe, S.; Grémillet, D.; Harding, A. M. A.; Igual, J. M.; Jurinović, L.; Kubetzki, U.; Lyons, D. E.; Orben, R.; Paredes, R.; Pirello, S.; Recorbet, B.; Shaffer, S. A.; Schwemmer, P.; Serra, L.; Spelt, A.; Tavecchia, G.; Tengeres, J.; Tome, D.; Williamson, C.; Windsor, S.; Young, H.; Zenatello, M.; Fijn, R. C. Active breeding seabirds prospect alternative breeding colonies. Oecologia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-Y.; Kokko, H. Sex-biased dispersal: a review of the theory. Biological Reviews 2019, 94, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabry, K. E.; Stamps, J. A. Searching for a New Home: Decision Making by Dispersing Brush Mice. The American Naturalist 2008, 172, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancinelli, S.; Ciucci, P. Beyond home: Preliminary data on wolf extraterritorial forays and dispersal in Central Italy. Mammalian Biology 2018, 93, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, R.; Bateman, A. W.; English, S.; Clutton-Brock, T. H.; Young, A. J. Timing of predispersal prospecting is influenced by environmental, social and state-dependent factors in meerkats. Animal Behaviour 2014, 88, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinović, M.; Galov, A.; Svetličić, I.; Tome, D.; Jurinović, L.; Ječmenica, B.; Basle, T.; Božič, L.; Kralj, J. Prospecting of breeding adult Common terns in an unstable environment. Ethology Ecology & Evolution 2019, 31, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Zedrosser, A.; Rosell, F. Extra-territorial movements differ between territory holders and subordinates in a large, monogamous rodent. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 15261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, B. T.; Michelot, T. momentuHMM: R package for generalized hidden Markov models of animal movement. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 9, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J. M.; Barta, Z.; Klaassen, M.; Baue, S. Cues and the optimal timing of activities under environmental changes. Ecology Letters 2011, 14, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Altenkamp, R.; Griessmann, B. Nightingales in space: song and extra-territorial forays of radio tagged song birds. Journal für Ornithologie 2001, 142, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.; Getz, W. M.; Revilla, E.; Holyoak, M.; Kadmon, R.; Saltz, D.; Smouse, P. E. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 19052–19059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, R.; Monk, C. T.; Arlinghaus, R.; Adam, T.; Alós, J.; Assaf, M.; Baktoft, H.; Beardsworth, C. E.; Bertram, M. G.; Bijleveld, A. I.; Brodin, T.; Brooks, J. L.; Campos-Candela, A.; Cooke, S. J.; Gjelland, K. Ø.; Gupte, P. R.; Harel, R.; Hellström, G.; Jeltsch, F.; Killen, S. S.; Klefoth, T.; Langrock, R.; Lennox, R. J.; Lourie, E.; Madden, J. R.; Orchan, Y.; Pauwels, I. S.; Říha, M.; Roeleke, M.; Schlägel, U. E.; Shohami, D.; Signer, J.; Toledo, S.; Vilk, O.; Westrelin, S.; Whiteside, M. A.; Jarić, I. Big-data approaches lead to an increased understanding of the ecology of animal movement. Science 2022, 375, eabg1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocera, J. J.; Forbes, G. J.; Giraldeau, L. A. Inadvertent social information in breeding site selection of natal dispersing birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2006, 273, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northrup, J. M.; Vander Wal, E.; Bonar, M.; Fieberg, J.; Laforge, M. P.; Leclerc, M.; Prokopenko, C. M.; Gerber, B. D. Conceptual and methodological advances in habitat-selection modeling: guidelines for ecology and evolution. Ecological Applications 2022, 32, e02470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orians, G. H.; Wittenberger, J. F. Spatial and temporal scales in habitat selection. The American Naturalist 1991, 137, S29–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, D.; Bécares, J.; Bartumeus, F.; Arcos, J. M. High frequency of prospecting for informed dispersal and colonisation in a social species at large spatial scale. Oecologia 2021, 197, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärt, T.; Doligez, B. Gathering public information for habitat selection: prospecting birds cue on parental activity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2003, 270, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchett, R.; Styles, P.; King, J. Robins; Kirschel, A. N. G.; Cresswell, W. The potential function of post-fledging dispersal behavior in first breeding territory selection for males of a migratory bird. Current Zoology 2022, 68, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péron, C.; Grémillet, D. Tracking through life stages: adult, immature and juvenile autumn migration in a long-lived seabird. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e72713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poessel, S. A.; Woodbridge, B.; Smith, B. W.; Murphy, R. K.; Bedrosian, B. E.; Bell, D. A.; Bittner, D.; Bloom, P. H.; Crandall, R. H.; Domenech, R.; Fisher, R. N.; Haggerty, P. K.; Slater, S. J.; Tracey, J. A.; Watson, J. W.; Katzner, T. E. Interpreting long-distance movements of non-migratory golden eagles: Prospecting and nomadism? Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Aulert, C.; Le Guillou, G.; Gallien, F.; Péron, C.; Grémillet, D. Spatial overlaps of foraging and resting areas of black-legged kittiwakes breeding in the English Channel with existing marine protected areas. Marine Biology 2017a, 164, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Chambert, T.; Lobato, E.; Tveraa, T.; Grémillet, D.; Boulinier, T. Breeding failure induces large scale prospecting movements in the black-legged kittiwake. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2015a, 473, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Garnier, R.; Grémillet, D.; Boulinier, T. Predicting population responses to environmental change: the importance of considering informed dispersal strategies in spatially structured population models. Diversity and Distributions 2015b, 21, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Grémillet, D.; Doligez, B.; Chambert, T.; Tveraa, T.; González-Solís, J.; Boulinier, T. Tracking prospecting movements involved in breeding habitat selection: insights, pitfalls and perspectives. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2013, 4, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Iliszko, L.; Grémillet, D.; Tveraa, T.; Boulinier, T. Intense prospecting movements of failed breeders nesting in an unsuccessful breeding subcolony. Animal Behaviour 2017b, 124, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Scarpa, A.; Bocedi, G.; Palmer, S. C. F.; Travis, J. M. J. Prospecting and informed dispersal: Understanding and predicting their joint eco-evolutionary dynamics. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 15289–15302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponchon, A.; Travis, J. M. J. Informed dispersal based on prospecting impacts the rate and shape of range expansions. Ecography 2022, 2022, e06190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöysä, H. Public information and conspecific nest parasitism in goldeneyes: targeting safe nests by parasites. Behavioral Ecology 2006, 17, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöysä, H.; Milonoff, M.; Ruusila, V.; Virtanen, J. Nest-Site Selection in Relation to Habitat Edge: Experiments in the Common Goldeneye. Journal of Avian Biology 1999, 30, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. M.; Boulinier, T.; Danchin, E.; Oring, L. W. Informed dispersal: prospecting by birds for breeding sites. Current Ornithology 1999, 15, 189–259. [Google Scholar]

- Rémy, A.; Le Galliard, J.-F.; Gundersen, G.; Steen, H.; Andreassen, H. P. Effects of individual condition and habitat quality on natal dispersal behaviour in a small rodent. Journal of Animal Ecology 2011, 80, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehl, C. Communal Calling And Prospecting By Black-Headed Trogons Trogon melanocephalus. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 2008, 120, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, T. J.; Ostler, J. R.; Conradt, L. The process of dispersal in badgers Meles meles. Mammal Review 2003, 33, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.; Sprau, P.; Schmidt, R.; Naguib, M.; Amrhein, V. Sex-specific timing of mate searching and territory prospecting in the nightingale: nocturnal life of females. Proceeedings of the Royal Society B 2009, 276, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldanha, S.; Cox, S. L.; Militão, T.; González-Solís, J. Animal behaviour on the move: the use of auxiliary information and semi-supervision to improve behavioural inferences from Hidden Markov Models applied to GPS tracking datasets. Movement Ecology 2023, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelius, G.; Andrén, H.; Liberg, O.; Linnell, J. D. C.; Odden, J.; Ahlqvist, P.; Segerström, P.; Sköld, K. Spatial and temporal variation in natal dispersal by Eurasian lynx in Scandinavia. Journal of Zoology 2012, 286, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tójar, A.; Winney, I.; Girndt, A.; Simons, M. J. P.; Nakagawa, S.; Burke, T.; Schroeder, J. Winter territory prospecting is associated with life-history stage but not activity in a passerine. Journal of Avian Biology 2017, 48, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardamaglia, R. C.; Fiorini, V. D.; Kacelnik, A.; Reboreda, J. C. Planning host exploitation through prospecting visits by parasitic cowbirds. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2016, 71, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuett, W.; Laaksonen, J.; Laaksonen, T. Prospecting at conspecific nests and exploration in a novel environment are associated with reproductive success in the jackdaw. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2012, 66, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selonen, V.; Hanski, I. K. Habitat exploration and use in dispersing juvenile flying squirrels. Journal of Animal Ecology 2006, 75, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selonen, V.; Hanski, I. K. Decision making in dispersing Siberian flying squirrels. Behavioral Ecology 2010, 21, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicotte, P.; Andrew, J. M. Inter-group encounters and male incursions in Colobus vellerosus in Central Ghana. Behaviour 2004, 141, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsbury, C. D.; Iossa, G.; Baker, P. J.; White, P. C. L.; Harris, S. Behavioral and spatial analysis of extraterritorial movements in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Journal of Mammalogy 2011, 92, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, O.; Leu, S. T.; Bull, C. M.; Sih, A. What’s your move? Movement as a link between personality and spatial dynamics in animal populations. Ecology Letters 2017, 20, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamps, J. A.; Krishnan, V. V.; Reid, M. L. Search costs and habitat selection by dispersers. Ecology 2005, 86, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutchbury, B. J. M.; Pitcher, T. E.; Norris, D. R.; Tuttle, E. M.; Gonser, R. A. Does male extra-territory foray effort affect fertilization success in hooded warblers Wilsonia citrina? Journal of Avian Biology 2005, 36, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichroeb, J. A.; Wikberg, E. C.; Sicotte, P. Dispersal in male ursine colobus monkeys (Colobus vellerosus): influence of age, rank and contact with other groups on dispersal decisions. Behaviour 2011, 148, 765–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, J.-F.; Pinaud, D.; Gauthier, G.; Lecomte, N.; Bildstein, K. L.; Bety, J. Is pre-breeding prospecting behaviour affected by snow cover in the irruptive snowy owl? A test using state-space modelling and environmental data annotated via Movebank. Movement Ecology 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R. L.; Sirkiä, P. M.; Villers, A.; Laaksonen, T. Temporal peaks in social information: prospectors investigate conspecific nests after a simulated predator visit. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2013, 67, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, A. M.; Walters, J. R.; Morris, W. F.; Sexton, J.; Moody, A. Empirical estimation of dispersal resistance surfaces: a case study with red-cockaded woodpeckers. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M. C.; Bocedi, G.; Hendry, A. P.; Mihoub, J.-B.; Pe’er, G.; Singer, A.; Bridle, J. R.; Crozier, L. G.; De Meester, L.; Godsoe, W.; Gonzalez, A.; Hellmann, J. J.; Holt, R. D.; Huth, A.; Johst, K.; Krug, C. B.; Leadley, P. W.; Palmer, S. C. F.; Pantel, J. H.; Schmitz, A.; Zollner, P. A.; Travis, J. M. J. Improving the forecast for biodiversity under climate change. Science 2016, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valone, T. J.; Templeton, J. J. Public information for the assessment of quality: a widespread social phenomenon. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2002, 357, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangen, K. M.; Persson, J.; Landa, A.; Andersen, R.; Segerström, P. Characteristics of dispersal in wolverines. Canadian Journal of Zoology 2001, 79, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, J. P.; Polo, V.; Arenas, M.; Sánchez, S. Intruders in Nests of the Spotless Starling: Prospecting for Public Information or for Immediate Nesting Resources? Ethology 2012, 118, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votier, S.; Grecian, W.; Patrick, S.; Newton, J. Inter-colony movements, at-sea behaviour and foraging in an immature seabird: results from GPS-PPT tracking, radio-tracking and stable isotope analysis. Marine Biology 2011, 158, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. Habitat selection by dispersing yellow-headed blackbirds: evidence of prospecting and the use of public information. Oecologia 2005, 145, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. P.; Alessi, M.; Benson, T. J.; Chiavacci, S. J. The active nightlife of diurnal birds: extraterritorial forays and nocturnal activity patterns. Animal Behaviour 2014, 88, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D. J.; Davies, H. B.; Agyapong, S.; Seegmiller, N. Nest prospecting brown-headed cowbirds “parasitize” social information when the value of personal information is lacking. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 284, 20171083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J. A. Population responses to patchy environments. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 1976, 7, 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. A.; Rabenold, K. N. Male-biased dispersal, female philopatry, and routes to fitness in a social corvid. Journal of Animal Ecology 2005, 74, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, D. W.; Fieberg, J. R.; Andersen, D. E. Juvenile Sandhill Cranes exhibit wider ranging and more exploratory movements than adults during the breeding season. Ibis 2020, 162, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. J.; Carlson, A. A.; Clutton-Brock, T. Trade-offs between extraterritorial prospecting and helping in a cooperative mammal. Animal Behaviour 2005, 70, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. J.; Monfort, S. L. Stress and the costs of extra-territorial movement in a social carnivore. Biology Letters 2009, 5, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A. J.; Spong, G.; Clutton-Brock, T. Subordinate male meerkats prospect for extra-group paternity: alternative reproductive tactics in a cooperative mammal. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2007, 274, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Scientific name | Taxon | Class of prospectors | Tracking device | Maximal prospecting distance (km) | Reference |

| Black-legged kittiwake | Rissa tridactyla | seabird | Failed breeders | GPS-UHF | 550 | (Boulinier et al. 2016) |

| Bonelli's eagle | Aquila fasciata | raptor | Juveniles | PTT | 435 | (Cadahía Lorenzo et al. 2009) |

| Audouin's gull | Larus audouinii | seabird | Failed and successful breeders | GPS + PTT | 360 | (Oro et al. 2021) |

| Golden eagle | Aquila chrysaetos | raptor | Juveniles and subadults | PTT | > 300 | (Poessel et al. 2022) |

| Black-legged kittiwake | Rissa tridactyla | seabird | Failed breeders | GPS-UHF | 220 | (Ponchon et al. 2017a) |

| White-tailed sea eagle | Haliaeetus albicilla | raptor | Juveniles | GPS-GSM | 200 | (Engler and Krone 2022) |

| Sandwich tern | Thalasseus sandvicensis | seabird | Failed breeders | GPS-UHF | 170 | (Fijn et al. 2014) |

| Black-browed albatross | Thalassarche melanophris | seabird | Immatures | GPS | 160 | (Campioni et al. 2017) |

| Wolf | Canis lupus | mammal | Adults | GPS | 147 | (Mancinelli and Ciucci 2018) |

| Northern gannet | Morus bassanus | seabird | Immatures | GPS-PTT+VHF | > 100 | (Votier et al. 2011) |

| Cory's shearwater | Calonectris diomedea | seabird | Immatures | PTT | > 100 | (Péron and Grémillet 2013) |

| European badger | Meles meles | mammal | Subadults (2-3 years-old) | GPS | > 100 | (Gaughran et al. 2019) |

| Black-legged kittiwake | Rissa tridatyla | seabird | Failed breeders | GPS | 40 | (Ponchon et al. 2015a) |

| Roe deer | Capreolus capreolus | mammal | Juveniles | GPS | 25 | (Debeffe et al. 2013) |

| Gray fox | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | mammal | Adults | GPS | 23.2 | (Deuel et al. 2017) |

| Common tern | Sterna hirundo | seabird | Successful and failed breeders | GPS-UHF | 19.5 | (Martinović et al. 2019) |

| Eurasian beaver | Castor fiber | mammal | Dominants and subordinates | GPS | 11.3 | (Mayer et al. 2017) |

| Californian spotted owl | Strix occidentalis occidentalis | raptor | Female breeders | GPS-UHF | > 10 | (Blakey et al. 2019) |

| Mallard, gadwall, cinnamon teal |

Anas platyrhynchos - Mareca strepera – Spatula cyanoptera |

waterfowl | Juveniles, immatures and adult females | GPS-GSM | 3 | (Casazza et al. 2020) |

| European badger | Meles meles | mammal | Juveniles and adults | GPS | 2 | (Kelly et al. 2020) |

| White-tailed deer | Odocoileus virginianus | mammal | Breeding females | GPS | < 2 | (Kolodzinski et al. 2010) |

| Class of factors | Factors | Class of prospectors | Example of references |

| Individual factors | Sex | Males, females | (Selonen and Hanski 2010, Jungwirth et al. 2015, Blakey et al. 2019) |

| Age | Juveniles, immatures, subadults, adults | (Campioni et al. 2017, Wolfson et al. 2020) | |

| Breeding status | Failed or successful breeders, non-breeders (=floaters) | (Kingma et al. 2016, Ponchon et al. 2017b, Martinović et al. 2019) | |

| Dispersal status | Philopatric or dispersing individuals | (Debeffe et al. 2013, Oro et al. 2021) | |

| Social factors | Social status | Dominants, helpers, subordinates | (Kingma et al. 2016, Cram et al. 2018) |

| Inbreeding | Kin-related individuals | (Eikenaar et al. 2008, Kingma et al. 2016) | |

| Environmental factors | Habitat size/quality | Territory owners | (Haughland and Larsen 2004, Mayer et al. 2017) |

| Habitat familiarity | All | (Armstrong et al. 1997, Bruinzeel and van de Pol 2004) | |

| Territory quality | Territory owners | (Barve et al. 2020) | |

| Predation risk | All | (Thomson et al. 2013) |

| Type of information | Cues | Species | Availability over time | Examples of references |

| Personal information | Habitat physical structure | All | Permanent | (Therrien et al. 2015) |

| Presence/activity of predators | All | Permanent | (Vangen et al. 2001) | |

| Vacant breeding sites | Territorial, colonial | Breeding season | (Bruinzeel and van de Pol 2004, Veiga et al. 2012) | |

| Empty breeding sites | Territorial, colonial | Non-breeding season | (Pöysä 2006, Ciaglo et al. 2021) | |

| Individual own breeding status/performance | All | Permanent | (Ponchon et al. 2015a, 2017b) | |

| Social information | Conspecific presence/activity | All | Breeding season | (Williams and Rabenold 2005) |

| Conspecific breeding performance | Territorial, colonial | Breeding season | (Calabuig et al. 2010) | |

| Number of eggs in nests | Birds | Incubation period | (Pöysä 2006, Martinović et al. 2019) | |

| Number and quality of offspring | All | Offspring rearing | (Pärt and Doligez 2003, Ward 2005, Veiga et al. 2012) | |

| Host body condition | Parasitic birds | Laying season | (Scardamaglia et al. 2016) | |

| Group composition | Social or cooperative | Permanent | (Mayer et al. 2017, Barve et al. 2020) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).