1. Introduction

The definition of home range is still widely accepted: an area crossed by an animal during its normal foraging activities, mating and parental care [

1]. Later studies refined this concept by emphasising its ecological and social dimensions, highlighting that the home range not only reflects resource distribution but also the spatial strategies animals adopt to meet reproductive and survival needs [

2]. In addition, analysing the degree of spatial overlap among individuals provides valuable insights into social organisation, competition, and cooperative behaviours, especially in group-living species such as wild boar [

3,

4]. Sex- and group-specific home ranges of wild boars have been reported in Italy [

5]: adult males’ range between 870 and 1,750 hectares, adult females between 360 and 560 hectares, while family groups of similarly aged individuals can reach up to 2,400 hectares. More fine-scale evidence was provided by a radiotracking study on adult wild boars in the Maremma Natural Park (Central Italy), which highlighted relatively small daily home ranges and a consistent pattern of activity concentrated during twilight and nighttime hours; the study did not detect differences between sexes or across months, a result likely influenced by the absence of breeding females and of significant human disturbance in the area, conditions that may also account for the higher degree of diurnally observed compared to other populations [

6]. These differences in space use reflect distinct reproductive strategies of males and female, which are in turn associated with the concept of allometric scaling of spatial requirements [

7,

8]. Seasonal changes in behavioural and the environmental conditions affect spatial dynamics and may influence inter- and intra-species interactions [

9,

10], home range size and habitat use [

9,

11]. Variation in spatial interactions between individuals may reveal selective pressures shaping spatial use [

12]; such dynamics are influenced by a combination of behavioural traits and environmental variables, which in turn affect spatial organisation within a population. The specific interactions influence the individual spatial pattern and these drive population processes such as disease transmission [

13], reproduction [

14], survival [

15,

16] and competition [

17]. Despite the growing trend that spatial relationships influence different socio-ecological processes [

18], variation in spatial patterns between sexes and age is poorly understood for wild boar in Apennine Mountains and identifying factors influencing this heterogeneity in spatial pattern can improve management and conservation decisions, including disease transmission [

19], intraspecific competition [

17] and management actions [

20]. Uncovering the factors influencing spatial overlap heterogeneity can refine ecological knowledge and improve conservation planning, especially during critical phases such as farrowing and early parental care. To improve understanding of spatial ecology and home range dynamics of wild boar, we conducted a telemetry study on pregnant wild boar females from March to June to assess space use during farrowing and early postnatal periods.

3. Results

3.1. Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR) Analysis

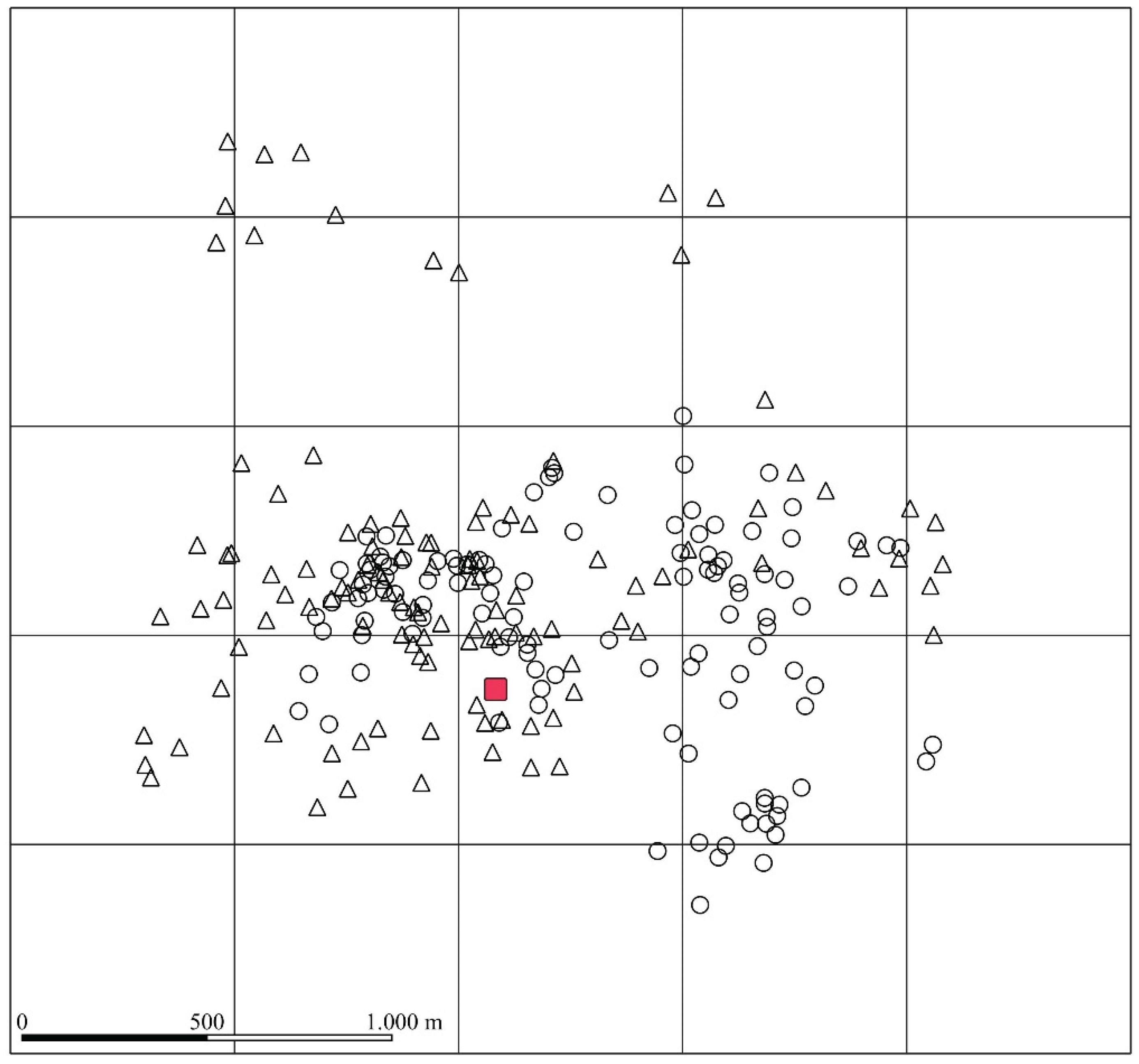

The quadrat method (χ2 = 497.61, p-value = 0.000) reject the null hypothesis of complete spatial randomness; the wild boars exhibit a strong clustered pattern. A clustered pattern is also present if we carry out the tests for the Farukka (χ2 = 327.83, p-value = 0.000) and Hermione (χ2 = 268.26, p-value = 0.000) localizations (

Figure 2). Dispersal distances are very low; the two female wild boars had average dispersal distances ranging between 550 and 650 m, with maximum values not exceeding 2 km from the capture site (

Table 2).

The analysis of dispersal distances from the capture site showed no significant difference between the two females (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: W = 6703, p = 0.858). Hermione’s fixes have an interquartile range (IQR) of 370.3 m (Q1 = 385.5 m; Q3 = 755.8 m), while Farukka’s ones spanned a broader range, from 65.9 to 1,648.9 meters, with a larger IQR of 571.7 m (Q1 = 310.9 m; Q3 = 882.6 m). Although Farukka exhibited slightly higher mean and maximum distances, as well as a wider variability, the strong overlap between the two distributions (

Figure 2) suggests that both females displayed broadly similar dispersal patterns from the capture site.

3.2. Home Range Analysis

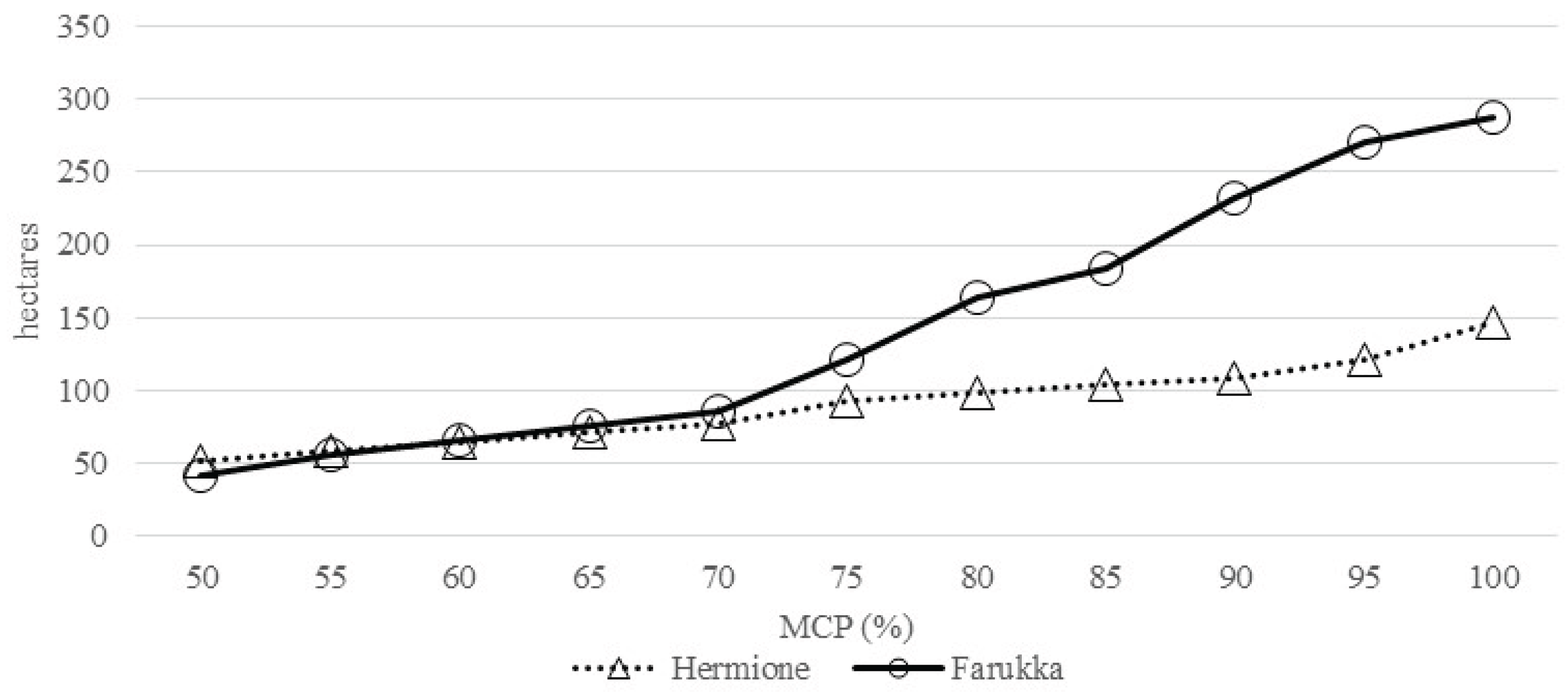

Home range (HR) values were measured using the minimum convex polygon method (MCP) at various percentile levels representing different extent of their home range. The two females exhibit slightly different overall dispersal behaviours (

Figure 3): Hermione seems to be more territorial, with a home range varying from a minimum of 51.3 ha (MCP50) to a maximum of 146.8 ha (MCP100). On the other hand, Farukka displays a broader dispersal pattern, with minimum home range values comparable to those of Hermione (41.9 ha MCP50) but significantly larger maximum values (287.3 ha MCP100).

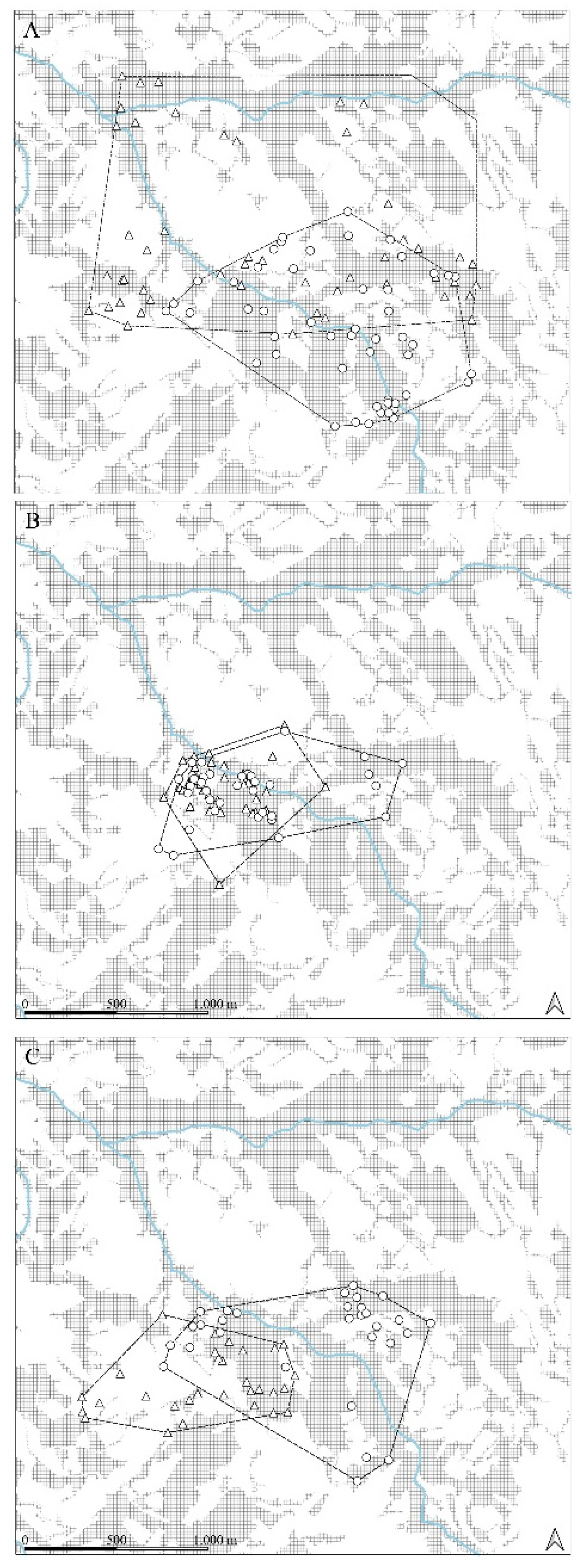

The comparative analysis of the HR size at percentile levels shows a difference in spatial behaviour between the two females across three distinct phases (

Table 3). The data reveal differences in the HR of Farukka and Hermione before births; for Hermione, the HR ranges from 49.7 hectares at the 50th percentile to 121.6 hectares at the 100th percentile, in contrast, Farukka exhibits a considerably larger HR, ranging from 125.5 hectares at the 50th percentile to 275.0 hectares at the 100th percentile. This indicates that Farukka has a more extensive home range compared to Hermione before giving birth, suggesting a possible difference in individual ranking and relative territorial or foraging behaviour. During the birthing phase both females exhibit a reduction of over 50% in their home range sizes, which could be attributed to the increased need for proximity to birthing sites and reduced mobility. The post-birth data suggest that both females slightly expand their home range (approximately 20-30% of the size observed during births), but this does not suggest a return to the normal activities observed before births; Hermione exhibits a greater expansion compared to Farukka (

Table 3).

The

Table 4 presents the breadth (Levin’s index), overlap (Pianka’s index) of habitat uses and distributions affinity indices for both females (Bhattacharyya index), across the three different temporal phases. The breadth in habitat use of Hermione shows variations across the different phases, with the lowest values occurring during births (L=0.11); this indicates a marginally narrower and potentially more specific resources utilization during the birthing period. This situation seems to be temporary because Hermione in the post-birth phase increases the use of landcover type with values higher than that pre-birth phase. Conversely, Farukka exhibits a noticeable reduction in habitat use during and after births (L=0.12 and L=0.13, respectively), suggesting a more constrained resources utilization during these times compared to the pre-birth period (L=0.17). The Pianka’s overlap index (

Table 4) indicates significant temporal fluctuations between the two wild boar females; the overlap is highest during pre-birth phase (O

hf=0.87), nearly complete, suggesting a common preference for specific resources during this critical period (

Figure 4B). During births and in the post-birth phase the overlap is moderate (O

hf=0.58 and O

hf=0.52 respectively), indicating that when the geometric overlap is maximum due to births and parental care (0.91 and 0.81) the females still partially differentiate the habitat use (

Figure 4A) to optimize trophic resources by minimizing interspecific competition. After giving birth, spatial overlap values decrease slightly but remain quite high (0.81), but Hermione, the dominant female, significantly increases the breadth of her landcover type, exceeding the pre-giving birth values. Farukka, subordinate in the rank, shows a post-giving situation very similar to that of giving birth.

In conclusion, the analysis reveals that both females, adjust their spatial breadth based on temporal changes, particularly around the birthing period; these variations appear to be partly determined by the social rank they occupy in the population. Hermione maintains a relatively consistent breadth values throughout, while Farukka's spatial occupancy becomes notably restricted during and after births. The near-complete overlap during births suggests a low degree of spatial competition or shared spatial requirements during this critical period. Finally, it is important to note that the maximum Pianka values are observed when geometric overlap is minimal; this indicates that, always, the two females reduce intraspecific competition to a minimum: in the pre-partum phase the overlap in habitat use is maximum, which indicates that they exploit the same resources, but most of the time in different spaces (Fig. 4A).

3.3. Environmental Analysis

Differences in landcover composition were observed between the two females, confirming variations in habitat use strategies; before births, Farukka and Hermione (

Table 5 and

Table 6) primarily utilized crops and Hornbeam Forest, but Farukka exhibited a greater reliance on permanent meadows (10.8 ± 4.2%) compared to Hermione (0.2 ± 0.2%, Wilcoxon W = 1,095, p < 0.01), while Hermione had a significantly higher presence in grassland (5.7 ± 1.9%, Wilcoxon W = 1,101, p < 0.01).

During the birthing phase, no differences in the frequency of vegetation types are observed; both females seem to prefer Hornbeam Forest and riverside forests.

After births, the two individuals displayed divergent habitat selection strategies; Farukka increased its reliance on permanent meadows (22.4 ± 5.4%) compared to Hermione (0%), marking a significant shift from the birth period (Wilcoxon W = 273, p < 0.001). In contrast, Hermione showed an increased preference for Broom shrubland (25.5 ± 7.1%, Wilcoxon W = 336, p < 0.001), likely due to the need for denser cover post-births. Hornbeam forest uses significantly decreased for Hermione (19.9 ± 5.8%), whereas Farukka continued selecting this habitat (48.8 ± 7.4%, Wilcoxon W = 343, p< 0.01). Pastures were significantly more used by Hermione (3.3 ± 1.6%) compared to Farukka, where they were completely absent (Wilcoxon W = 367, p < 0.01).

Habitat selection analysis based on Jacobs’ Index [

44] revealed distinct patterns of preference across the three phenological stages. During the birth period, a clear shift in habitat selection was observed, with both individuals increasing their use of Hornbeam Forest (D = 0.2870 for Farukka and D = 0.3362 for Hermione) but riverside vegetation became selected by both individuals (D = 0.6918 for Farukka and D = 0.6748 for Hermione), indicating its importance during births (

Table 7 and

Table 8). The use of crops significantly declined (

Table 5 and

Table 6) compared to the pre-birth period, dropping to 13.9 ± 3.5% (p < 0.01) for Farukka and 12.6 ± 3.0% for Hermione, reinforcing a transition away from open agricultural areas.

Key results from Jacobs’ Index for births: riparian vegetation, initially avoided, became one of the most strongly selected habitats (D = 0.6918 for Farukka, D = 0.6748 for Hermione, p < 0.001); crops continued to be avoided (-0.4835 for Farukka, -0.5239 and for Hermione) and Pre-wood forests remained strongly avoided (-0.9701 for Farukka, -0.9649 for Hermione, p < 0.001). Both individuals strongly avoided urban areas (

Table 7 and

Table 8); crops were used by Farukka (D = 0.0430), whereas Hermione slightly avoided them (-0.3376, p < 0.05). Farukka strongly avoided riparian vegetation (-0.9839), while Hermione also showed strong avoidance (-0.9887), despite its low availability.

Jacobs’ Index results highlighted that Farukka strongly selected permanent meadows (D = 0.5235, p < 0.001) while Hermione exhibited strong selection for shrubland (D = 0.8137 and 0.8188, p < 0.001). Riparian vegetation, previously selected during births, was now avoided by Farukka (-0.3440, p < 0.01), while Hermione continued to select it (D = 0.5590, p < 0.001).

Hornbeam forest was consistently used throughout all phenological periods, with moderate positive selection; riparian vegetation transitioned from strong avoidance before births to strong selection during births and after births, particularly for Hermione. Permanent meadows were highly selected by Farukka post-birth, whereas shrubland became crucial for Hermione. Crops were used before births but consistently avoided during and after births, during May months the crops are not ripe and therefore this type of habitat does not provide abundant food for the survival of the young wild boars.

These findings suggest that habitat selection is strongly influenced by reproductive needs and environmental constraints, with individual-specific preferences playing a role in shaping movement and resource use.

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight significant temporal variations in the home range of pregnant wild boar females before, during, and after births. The home range of both females was significantly reduced during the birthing period, consistent with previous research indicating that female wild boars adopt more restricted movement patterns near births to ensure safety and resource accessibility for their offspring [

4,

46]. The reduction in home range size by over 50% during the birthing phase confirms that parturient females limit movement to minimize predation risk and energy expenditure [

9,

19].

These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that spatial requirements and behaviour differ between sexes because of reproductive strategies and body size allometry [

11]. While male wild boars often exhibit expansive home ranges (870 - 1,750 ha) to maximize mating opportunities, females prioritize spatial stability, particularly during reproduction [

5]. Our telemetry data showed that Farukka maintained a larger home range before birth compared to Hermione (275.0 ha vs. 121.6 ha at MCP100), which may indicate individual variation in dominance rank or foraging strategy. This supports previous studies that suggest dominant females tend to occupy larger territories with higher-quality food resources [

14].

After births, both individuals expanded their home ranges, although this did not return to pre-birth levels, indicating a gradual reintroduction of movement associated with offspring development [

15,

16,

47]. However, Hermione exhibited greater post-birth expansion than Farukka, possibly due to different resource distribution strategies; this divergence may be influenced by intraspecific competition or maternal experience, as younger or subordinate females may adopt more mobile foraging tactics to compensate for reduced access to high-quality habitats [

17].

The Jacobs’ Index analysis revealed distinct habitat selection patterns across the three phenological periods. Before birth, both females exhibited a preference for forested environments, with Farukka selecting croplands (D = 0.0430) more than Hermione (D = -0.3376, p < 0.05). This suggests that croplands were important food sources prior to births, which is consistent with findings that pregnant wild boars increase their intake of high-energy foods to support foetal development [

48]. However, during the birthing phase, both individuals significantly reduced their use of croplands, likely due to increased human disturbance and a preference for secluded areas [

20].

One of the most striking results was the strong selection for riverside vegetation during births (D = 0.6918 for Farukka and D = 0.6748 for Hermione, p < 0.001); these findings confirm that dense riverside habitats offer optimal cover and reduced predation risk for neonates, as observed in other studies on ungulate births sites [

13]. Riparian areas likely provide thermoregulation benefits and proximity to water, crucial for lactating females. However, after birth, Farukka abandoned riparian areas (-0.3440, p < 0.01), whereas Hermione continued selecting them (D = 0.5590, p < 0.001). This suggests individual variability in post-birth habitat use, possibly influenced by offspring vulnerability, predator pressure, or maternal investment strategies.

The post-birth phase revealed divergent habitat use strategies: Farukka selected permanent meadows (D = 0.5235, p < 0.001), while Hermione strongly preferred shrubland (D = 0.8137, p < 0.001). Hornbeam forest use decreased for Hermione (p < 0.01), while Farukka continued to rely on it. Crops were avoided by both individuals, likely due to their seasonal availability (May–June) when young boars require alternative food sources. These differences may reflect their social hierarchy: Hermione, probably the dominant female, exploited shrubland areas that provide both cover and protective structure for offspring, while Farukka, being subordinate, was more frequently observed in permanent meadows, possibly as a strategy to reduce direct competition. Similar patterns have been observed in other social ungulates, where dominance influences access to safer or higher-quality habitats [

49,

50]. These results highlight the complexity of maternal habitat selection in wild boars, demonstrating adaptive flexibility shaped by both environmental conditions and social status [

8], and suggest that the two females adopt distinct post-birth strategies to optimize resource use and minimize competition.

Our results indicate that the post-birth divergence in habitat use is closely linked to the social hierarchy within the family group. Rather than focusing solely on the specific environments selected, the contrast between the two females should be interpreted as a reflection of dominance-driven strategies: Hermione, as the leading sow, had priority access to habitats offering structural protection and concealment for neonates, whereas Farukka, constrained by her subordinate status, adapted by exploiting more accessible areas with reduced cover. This interpretation is consistent with previous findings that wild boar social units are organised along matrilineal hierarchies, where dominant females exert a disproportionate influence on spatial organisation and habitat access [

51,

52]. Similar processes have been reported in other ungulates, where maternal rank determines access to habitats that maximise offspring survival and minimise predation risk [

49,

53]. In our case, the divergent strategies of Hermione and Farukka illustrate how reproductive needs interact with social asymmetries to produce differentiated habitat selection patterns, emphasising the importance of considering intra-group dominance relationships when interpreting fine-scale spatial behaviour in wild boar.

Our analysis of spatial niche breadth (Levin’s index) and niche overlap (Pianka’s index) confirm that maternal wild boars exhibit dynamic spatial strategies depending on reproductive phase. Before birth, spatial overlap between the two females was moderate (Ojk = 0.46), but during births, overlap increased significantly (Ojk = 0.95). This near-total overlap implies that both individuals shared similar births sites, likely due to limited availability of optimal birthing habitats [

12]. However, after birth, spatial overlap declined drastically (Ojk = 0.19), suggesting that post-births dispersal helps reduce intra-group competition for resources [

17].

The reduction in spatial niche breadth during births (L = 0.10 - 0.15) further supports the idea that wild boar females prioritize a more localized and protective environment for neonates; this pattern is commonly observed in other socially structured ungulates, where females adjust movement patterns to balance protection and resource availability for offspring [

15].

Understanding maternal home range dynamics and habitat selection has crucial implications for wild boar management in agricultural landscapes. Given that crop damage is primarily caused by females with offspring, identifying preferred birthing habitats can inform targeted mitigation strategies. Our findings suggest that riparian areas serve as key births sites, and management plans should focus on balancing conservation efforts with potential conflicts in these regions. Crop depredation risk is highest before births, when females utilize agricultural fields more extensively; strategies such as non-lethal deterrents or seasonal exclusion zones could reduce human-wildlife conflicts.

Post-birth dispersal patterns indicate that young wild boars remain with their mothers in resource-rich areas, making localized control efforts more effective during this period.

These findings support a spatially explicit approach to wild boar management, emphasizing female movement patterns as key drivers of human-wildlife interactions.

Author Contributions

G.A.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, resources, supervision, project administration. F.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation. C.S: writing—review and editing, supervision. A.B.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

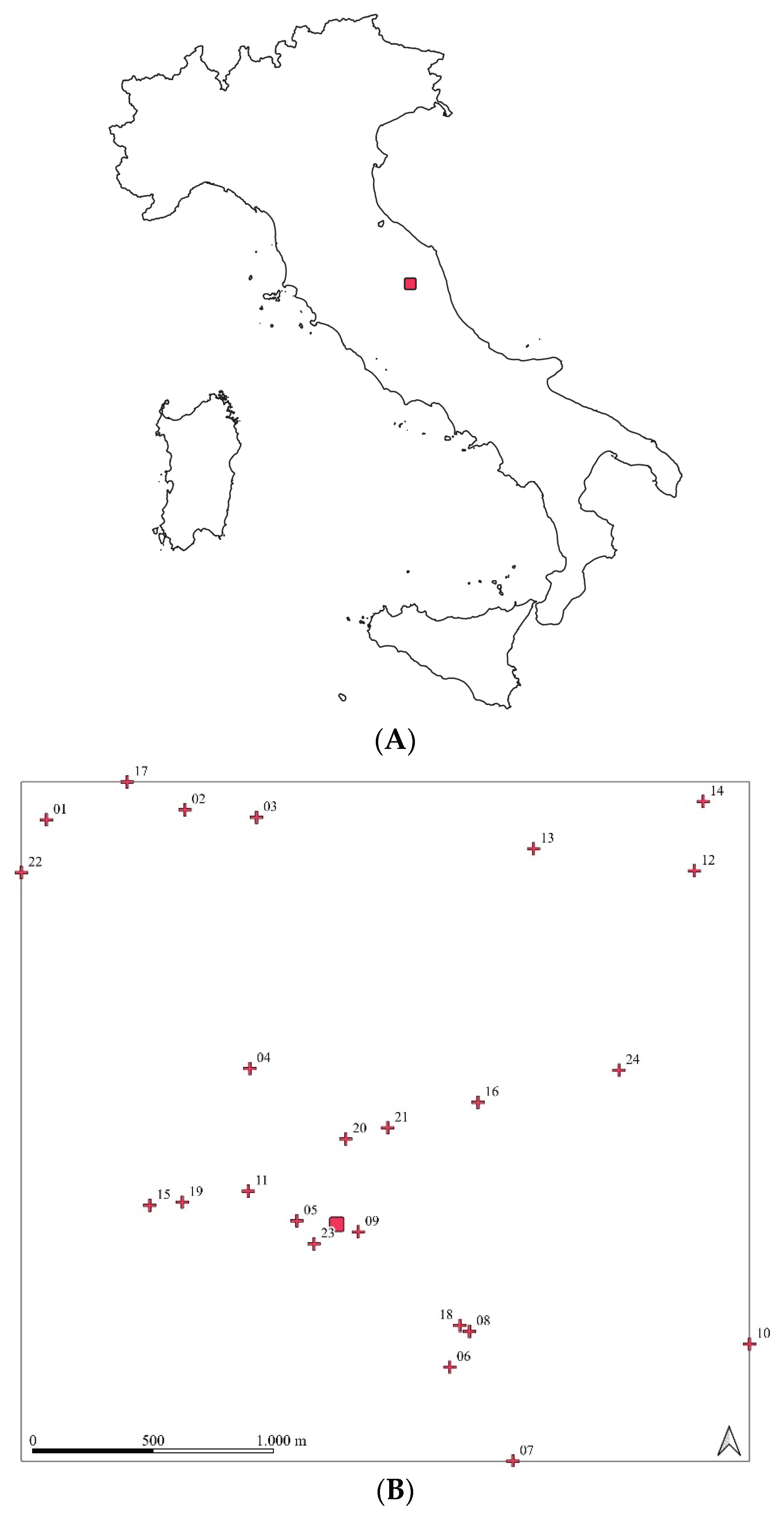

Figure 1.

A) Red square: location of the study area; B) Extent of spatial dataset: red cross: VHF receiving stations; red square: capture site.

Figure 1.

A) Red square: location of the study area; B) Extent of spatial dataset: red cross: VHF receiving stations; red square: capture site.

Figure 2.

Extent of spatial dataset: triangle, Farukka VHF fixes; circle, Hermione VHF fixes; red square: capture site.

Figure 2.

Extent of spatial dataset: triangle, Farukka VHF fixes; circle, Hermione VHF fixes; red square: capture site.

Figure 3.

Computation of home range size for various choices of the number of extreme locations to be excluded. With minimum values of up to 70% of the locations, the two females have the same home range size.

Figure 3.

Computation of home range size for various choices of the number of extreme locations to be excluded. With minimum values of up to 70% of the locations, the two females have the same home range size.

Figure 4.

Home range (MCP100) overlapping for the two wild boar females; wooded areas in grey; hydrographic network in blue; Hermione (triangle), Farukka (circle); before births (A), births (B) and after births (C).

Figure 4.

Home range (MCP100) overlapping for the two wild boar females; wooded areas in grey; hydrographic network in blue; Hermione (triangle), Farukka (circle); before births (A), births (B) and after births (C).

Table 1.

Summary of study area land cover.

Table 1.

Summary of study area land cover.

| Landcover |

Dominant Plant Species |

COD |

Ha |

% |

| Blackthorn Shrubland |

Prunus spinosa |

Shrub_Bl |

25,8 |

3,0 |

| Broom Shrubland |

Spartium junceum |

Shrub_Br |

28,4 |

3,3 |

| Cropland |

Triticum sp.pl., Hordeum sp.pl., Helianthus annus

|

Crops |

261,9 |

30,6 |

| Walnut |

Juglans regia |

Walnut |

2,6 |

0,3 |

| Permanent meadows |

Medicago sativa, Onobrychis vicifolia |

P_mead |

69,1 |

8,1 |

| Grassland |

Bromopsis erecta, Brachypodium rupestre |

Past |

42,2 |

4,9 |

| Pre_wood vegetation |

Quercus sp.pl., Ostrya carpinifolia, Acer campestre

|

P_wood |

48,5 |

5,7 |

| Riverside vegetation |

Quercus sp.pl., Acer campestre, Fraxinus ornus

|

Rv |

77,5 |

9,0 |

| Hornbeam Forest |

Ostrya carpinifolia, Quercus pubescens |

Horn_forest |

280,1 |

32,7 |

| Pinus nigra reforestation |

Pinus nigra |

Pinus |

9,9 |

1,2 |

| Urban settlement |

|

Urban |

10,4 |

1,2 |

| |

|

|

|

856,4 |

|

Table 2.

Dispersal distances (meters) from capture site. N, number of locations; SD, Standard Deviation.

Table 2.

Dispersal distances (meters) from capture site. N, number of locations; SD, Standard Deviation.

| VHF nickname |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Farukka |

115 |

622,68 |

399,28 |

65,91 |

1.648,89 |

| Hermione |

115 |

574,25 |

252,30 |

90,94 |

1.191,64 |

Table 3.

Home range values (hectares) measured using the minimum polygon convex (MCP) method at various percentile levels. The two females show significant difference in spatial behaviour across three distinct periods.

Table 3.

Home range values (hectares) measured using the minimum polygon convex (MCP) method at various percentile levels. The two females show significant difference in spatial behaviour across three distinct periods.

| MCP% |

Hermione |

Farukka |

| pre-birth |

birth |

post-birth |

pre-birth |

birth |

post-birth |

| 50 |

49.7 |

7.3 |

32.1 |

125.5 |

6.3 |

13.3 |

| 55 |

59.2 |

8.2 |

33.0 |

140.5 |

6.7 |

17.6 |

| 60 |

63.2 |

9.1 |

35.7 |

153.3 |

7.8 |

20.4 |

| 65 |

68.2 |

11.0 |

37.4 |

160.9 |

8.8 |

22.8 |

| 70 |

70.0 |

11.3 |

40.2 |

174.8 |

8.8 |

26.8 |

| 75 |

75.0 |

15.9 |

41.6 |

185.1 |

9.6 |

34.3 |

| 80 |

81.5 |

24.8 |

46.4 |

202.2 |

10.4 |

36.9 |

| 85 |

88.0 |

30.0 |

51.7 |

208.0 |

10.7 |

37.9 |

| 90 |

105.1 |

44.6 |

74.2 |

219.6 |

14.4 |

46.2 |

| 95 |

112.6 |

49.7 |

78.9 |

250.5 |

19.6 |

49.2 |

| 100 |

121.6 |

58.7 |

95.5 |

275.0 |

42.1 |

51.7 |

Table 4.

Resource niche breadth (Levin’s index) for Farukka and Hermione, resource niche overlapping (Pianka’s index) and affinity between the two distributions (Bhattacharyya’s index), across three different temporal phases: pre-birth, birth and post-birth.

Table 4.

Resource niche breadth (Levin’s index) for Farukka and Hermione, resource niche overlapping (Pianka’s index) and affinity between the two distributions (Bhattacharyya’s index), across three different temporal phases: pre-birth, birth and post-birth.

| . |

Levin’s index |

Pianka’s index |

Bhattacharyya’s index |

| |

Hermione |

Farukka |

| Pre-birth |

0.15 |

0.17 |

0.87 |

0.51 |

| Birth |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.58 |

0.91 |

| Post-birth |

0.18 |

0.13 |

0.52 |

0.81 |

Table 5.

Environmental parameters of Farukka by phenological phases. SD, Standard deviation; pj,s, statistic differences between before births and births phase; ps,a, statistic differences between births and after births phases.

Table 5.

Environmental parameters of Farukka by phenological phases. SD, Standard deviation; pj,s, statistic differences between before births and births phase; ps,a, statistic differences between births and after births phases.

| Parameters |

Before births |

Births |

pj,s

|

After births |

ps,a

|

| mean ± SD |

mean ± SD |

mean ± SD |

| Shrub_Br |

9.5 ± 3.8 |

- |

< 0.05 |

- |

- |

| Shrub_Bl |

2.4 ± 1.4 |

4.4 ± 1.1 |

< 0.05 |

1.0 ± 0.6 |

< 0.05 |

| Horn_forest |

30.1 ± 4.8 |

44.0 ± 6.5 |

- |

48.8 ± 7.4 |

- |

| Crops |

33.5 ± 4.5 |

13.9 ± 3.5 |

< 0.01 |

12.9 ± 4.9 |

- |

| P_wood |

0.7 ± 0.4 |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

- |

9.1 ± 3.9 |

< 0.05 |

| Walnut |

0.5 ± 0.5 |

- |

- |

0.6 ± 0.5 |

- |

| Past |

0.8 ± 0.5 |

0.3 ± 0.1 |

.- |

- |

< 0.05 |

| P_mead |

10.8 ± 4.2 |

1.2 ± 0.8 |

- |

22.4 ± 5.4 |

< 0.001 |

| Pinus |

- |

- |

- |

0.4 ± 0.3 |

- |

| Urban |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Rv |

11.9 ± 4.1 |

36.3 ± 7.2 |

< 0.001 |

4.8 ± 2.3 |

< 0.001 |

Table 6.

Environmental parameters of Hermione by phenological phases. SD, Standard deviation; pj,s, statistic differences between before births and births phase; ps,a, statistic differences between births and after births phases.

Table 6.

Environmental parameters of Hermione by phenological phases. SD, Standard deviation; pj,s, statistic differences between before births and births phase; ps,a, statistic differences between births and after births phases.

| Parameters |

Before births |

Births |

pj,s

|

After births |

ps,a

|

| mean ± SD |

mean ± SD |

mean ± SD |

| Shrub_Br |

6.1 ± 3.4 |

- |

< 0.001 |

25.5 ± 7.1 |

< 0.01 |

| Shurb_Bl |

3.8 ± 1.4 |

3.2 ± 1.1 |

< 0.01 |

1.8 ± 0.8 |

< 0.01 |

| Horn_forest |

37.5 ± 5.0 |

46.7 ± 6.6 |

< 0.05 |

19.9 ± 5.8 |

< 0.01 |

| Crops |

18.6 ± 3.2 |

12.6 ± 3.0 |

< 0.001 |

21.4 ± 4.6 |

< 0.001 |

| P_wood |

0.2 ± 0.2 |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

- |

- |

< 0.01 |

| Walnut |

0.3 ± 0.3 |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

< 0.01 |

0.3 ± 0.3 |

< 0.05 |

| Past |

5.7 ± 1.9 |

2.0 ± 1.1 |

< 0.001 |

3.3 ± 1.6 |

< 0.05 |

| P_mead |

0.2 ± 0.2 |

0.5 ± 0.5 |

- |

- |

- |

| Pinus |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

- |

0.4 ± 0.3 |

- |

| Urban |

0.1 ± 0.1 |

- |

- |

0.5 ± 0.4 |

- |

| Rv |

27.4 ± 2.1 |

34.8 ± 7.7 |

- |

26.8 ± 5.9 |

- |

Table 7.

Jacobs’ index for Farukka habitat selection according to the three phenological periods. p= proportion of habitat available in the study area; r= proportion of the habitat used by animal (e.g. % home range occupied by habitat); D= Jacobs’s index; i= indifferent; s= selected; ss= strongly selected; a= avoided; sa= strongly avoided.

Table 7.

Jacobs’ index for Farukka habitat selection according to the three phenological periods. p= proportion of habitat available in the study area; r= proportion of the habitat used by animal (e.g. % home range occupied by habitat); D= Jacobs’s index; i= indifferent; s= selected; ss= strongly selected; a= avoided; sa= strongly avoided.

| Parameter |

|

Pre-birth |

Birth |

Post-birth |

| p |

r |

D |

|

r |

D |

|

r |

D |

|

| Shrub_Br |

0.034 |

0.0925 |

0.4867 |

i |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

| Shurb_Bl |

0.033 |

0.0240 |

-0.1620 |

i |

0.0437 |

0.1454 |

i |

0.0097 |

-0.5530 |

a |

| Horn_forest |

0.303 |

0.3009 |

-0.0051 |

i |

0.4397 |

0.2870 |

i |

0.4878 |

0.3733 |

i |

| Crops |

0.316 |

0.3349 |

0.0430 |

i |

0.1386 |

-0.4835 |

i |

0.1291 |

-0.5142 |

a |

| P_wood |

0.058 |

0.0073 |

-0.7860 |

sa |

0.0009 |

-0.9701 |

sa |

0.0913 |

0.2400 |

i |

| Walnut |

0.003 |

0.0047 |

0.2218 |

i |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

0.0057 |

0.3078 |

i |

| Past |

0.051 |

0.0083 |

-0.7317 |

a |

0.0026 |

-0.9076 |

sa |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

| P_mead |

0.083 |

0.1075 |

0.1421 |

i |

0.0117 |

-0.7689 |

sa |

0.2244 |

0.5235 |

s |

| Pinus |

0.012 |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

0.0038 |

-0.5259 |

a |

| Urban |

0.013 |

0.0008 |

-0.8801 |

sa |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

0.0000 |

-1.0000 |

sa |

| Rv |

0.094 |

0.0008 |

-0.9839 |

sa |

0.3628 |

0.6918 |

s |

0.0482 |

-0.3440 |

i |

Table 8.

Jacobs’ index for Hermione habitat selection according to the three phenological periods. p= proportion of habitat available in the study area; r= proportion of the habitat used by animal (e.g. % home range occupied by habitat); D= Jacobs’s index; i= indifferent; s= selected; ss= strongly selected; a= avoided; sa= strongly avoided.

Table 8.

Jacobs’ index for Hermione habitat selection according to the three phenological periods. p= proportion of habitat available in the study area; r= proportion of the habitat used by animal (e.g. % home range occupied by habitat); D= Jacobs’s index; i= indifferent; s= selected; ss= strongly selected; a= avoided; sa= strongly avoided.

| Parameter |

|

Before births |

Births |

After births |

| p |

r |

D |

|

r |

D |

|

r |

D |

|

| Shrub_Br |

0.034 |

0,0611 |

0,2978 |

i |

0,0000 |

-1,0000 |

sa |

0,2552 |

0,8137 |

ss |

| Shurb_Bl |

0.033 |

0,0386 |

0,0806 |

i |

0,0318 |

-0,0184 |

i |

0,2552 |

0,8188 |

ss |

| Horn_forest |

0.303 |

0,3752 |

0,1601 |

i |

0,4667 |

0,3362 |

i |

0,1991 |

-0,2724 |

i |

| Crops |

0.316 |

0,1862 |

-0,3376 |

i |

0,1261 |

-0,5239 |

a |

0,2137 |

-0,2593 |

i |

| P_wood |

0.058 |

0,0002 |

-0,9929 |

sa |

0,0011 |

-0,9649 |

sa |

0,0000 |

-1,0000 |

sa |

| Walnut |

0.003 |

0,0033 |

0,0407 |

i |

0,0007 |

-0,6349 |

a |

0,0031 |

0,0109 |

i |

| Past |

0.051 |

0,0572 |

0,0606 |

i |

0,0201 |

-0,4483 |

i |

0,0335 |

-0,2162 |

i |

| P_mead |

0.083 |

0,0019 |

-0,9585 |

sa |

0,0046 |

-0,9026 |

sa |

0,0000 |

-1,0000 |

sa |

| Pinus |

0.012 |

0,0085 |

-0,1710 |

i |

0,0006 |

-0,9024 |

sa |

0,0037 |

-0,5358 |

a |

| Urban |

0.013 |

0,0006 |

-0,9144 |

sa |

0,0000 |

-1,0000 |

sa |

0,0050 |

-0,4439 |

i |

| Rv |

0.094 |

0,0006 |

-0,9887 |

sa |

0,3483 |

0,6748 |

s |

0,2684 |

0,5590 |

s |