Submitted:

27 December 2023

Posted:

27 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Catalytic system

3.1.1. Heterogeneous catalytic system

3.1.2. Reaction conditions in heterogeneous catalytic systems

3.1.3. Resistance and deactivation of heterogeneous catalyst

3.1.4. Biphasic aqueous/organic system catalytic system

3.2. Partial hydrogenation methods

3.2.1. Conventional partial hydrogenation

3.2.2. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation

3.2.3. Simultaneous transesterification and partial hydrogenation under supercritical methanol

3.2.4. Partial hydrogenation in biphasic aqueous/organic system

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| BMIM-NTf2 | 1-butyl-3-methylimdazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| BPhDS | Bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid disodium salt |

| CFPP | Cold Filter Plugging Point |

| CN | Cetane Number |

| CP | Cloud Point |

| DBD | Dielectric-Barrier Discharge |

| DTPPA | Diethylenetriaminepentakis(methyl-phosphonic acid) |

| EDTANa4 | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt |

| FAMEs | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters |

| H-FAMEs | Hydrogenated Fatty Acid Methyl Esters |

| ImS3-12 | 3-(1-dodecyl-3-imidazolio)propanesulfonate |

| IV | Iodine Value |

| MCM-41 | Mobil Composition of Matter No. 41 |

| OS | Oxidative Stability |

| PP | Pour Point |

| SBA-15 | Santa Barbara Amorphous-15 |

| TOF | Turn Over Frequency |

| TPPTS | Triphenylphosphinetrisulfonic acid trisodium salt |

References

- Zhang, L.; Xin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, G.; Li, Z.; Ou, Y. Mechanistic Study of the Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Biodiesel Catalyzed by Raney-Ni under Microwave Heating. Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 695–704. [CrossRef]

- Poyadji, K.; Stylianou, M.; Agapiou, A.; Kallis, C.; Kokkinos, N. Determination of Quality Properties of Low-Grade Biodiesel and Its Heating Oil Blends. Environments - MDPI 2018, 5, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Emmanouilidou, E.; Lazaridou, A.; Mitkidou, S.; Kokkinos, N.C. Biodiesel Production from Edible and Non-Edible Biomasses and Its Characterization. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 436, 04003. [CrossRef]

- Emmanouilidou, E.; Mitkidou, S.; Agapiou, A.; Kokkinos, N.C. Solid Waste Biomass as a Potential Feedstock for Producing Sustainable Aviation Fuel: A Systematic Review. Renewable Energy 2023, 206, 897–907. [CrossRef]

- Adu-Mensah, D.; Mei, D.; Zuo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. A Review on Partial Hydrogenation of Biodiesel and Its Influence on Fuel Properties. Fuel 2019, 251, 660–668. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, N.; Papadopoulos, C.E.; Lazaridou, A.; Koutsoumba, A.; Bouriazos, A.; Papadogianakis, G. Partial Hydrogenation of Methyl Esters of Sunflower Oil Catalyzed by Highly Active Rhodium Sulfonated Triphenylphosphite Complexes. Catalysis Communications 2009, 10, 451–455. [CrossRef]

- Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Chen, S.-Y.; Yoshimura, Y. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil-Derived Fatty Acid Methyl Esters over Pd Supported on Zr-SBA-15 with Various Zr Loading Levels for Enhanced Oxidative Stability. Fuel Processing Technology 2018, 179, 422–435. [CrossRef]

- Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Jitjamnong, J.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Numwong, N.; Chollacoop, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Influence of Mg Modifier on Cis-Trans Selectivity in Partial Hydrogenation of Biodiesel Using Different Metal Types. Applied Catalysis A: General 2016, 520, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.R.; Haas, M.J.; Winkler, J.K.; Jackson, M.A.; Erhan, S.Z.; List, G.R. Evaluation of Partially Hydrogenated Methyl Esters of Soybean Oil as Biodiesel. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2007, 109, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.E.; Lazaridou, A.; Koutsoumba, A.; Kokkinos, N.; Christoforidis, A.; Nikolaou, N. Optimization of Cotton Seed Biodiesel Quality (Critical Properties) through Modification of Its FAME Composition by Highly Selective Homogeneous Hydrogenation. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, 1812–1819. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.; Lazaridou, A.; Stamatis, N.; Orfanidis, S.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Christoforidis, A.; Nikolaou, N. Biodiesel Production from Selected Microalgae Strains and Determination of Its Properties and Combustion Specific Characteristics. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Review 2015, 8, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Pratama, D.F.; Susanto, B.H.; Ramayeni, E. Application of Modified Microwave Polyol Process Method on NiMo/C Nanoparticle Catalyst Preparation for Hydrogenated Biodiesel Production.; 2018; Vol. 105.

- Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Catalytic Upgrading of Soybean Oil Methyl Esters by Partial Hydrogenation Using Pd Catalysts. Fuel 2016, 163, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Numwong, N.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Effect of Metal Type on Partial Hydrogenation of Rapeseed Oil-Derived FAME. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2013, 90, 1431–1438. [CrossRef]

- Erenturk, S.; Korkut, Ö. Effectiveness of Activated Mistalea (Viscum Album L.) as a Heterogeneous Catalyst for Biodiesel Partial Hydrogenation. Renewable Energy 2018, 117, 374–379. [CrossRef]

- Numwong, N.; Prabnasak, P.; Prayoonpunratn, P.; Triphatthanaphong, P.; Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Mochizuki, T.; Chen, S.-Y.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Sooknoi, T. Effect of Pd Particle Size on Activity and Cis-Trans Selectivity in Partial Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil-Derived FAMEs over Pd/SiO2 Catalysts. Fuel Processing Technology 2020, 203. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, G. Partial Hydrogenation of Sunflower Oil-Derived Fames Catalyzed by the Efficient and Recyclable Palladium Nanoparticles in Polyethylene Glycol. Journal of Oleo Science 2017, 66, 1161–1168. [CrossRef]

- Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Jitjamnong, J.; Chollacoop, N.; Chen, S.-Y.; Yoshimura, Y. Influence of Alkaline and Alkaline Earth Metal Promoters on the Catalytic Performance of Pd- M /SiO2 (M = Na, Ca, or Ba) Catalysts in the Partial Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil-Derived Biodiesel for Oxidative Stability Improvement. Energy and Fuels 2018, 32, 9744–9755. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-Y.; Ryu, J.-H.; Bae, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.C. Biodiesel Production from Highly Unsaturated Feedstock via Simultaneous Transesterification and Partial Hydrogenation in Supercritical Methanol. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2013, 82, 251–255. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.; Theochari, G.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Angelova, D.; Toteva, V.; Lazaridou, A.; Mitkidou, S. Biodiesel Production from High Free Fatty Acid Byproduct of Bioethanol Production Process.; 2022; Vol. 1123.

- Chen, S.-Y.; Attanatho, L.; Chang, A.; Laosombut, T.; Nishi, M.; Mochizuki, T.; Takagi, H.; Yang, C.-M.; Abe, Y.; Toba, M.; et al. Profiling and Catalytic Upgrading of Commercial Palm Oil-Derived Biodiesel Fuels for High-Blend Fuels. Catalysis Today 2019, 332, 122–131. [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z. Catalytic Upgrading of Jatropha Oil Biodiesel by Partial Hydrogenation Using Raney-Ni as Catalyst under Microwave Heating. Energy Conversion and Management 2018, 163, 208–218. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO, W.; HUA, C.; ZHANG, X.; QI, X.; TANONGKIAT, K.; WANG, J. Study of Selective Hydrogenation of Biodiesel in a DBD Plasma Reactor. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 095506. [CrossRef]

- Souza, B.S.; Pinho, D.M.M.; Leopoldino, E.C.; Suarez, P.A.Z.; Nome, F. Selective Partial Biodiesel Hydrogenation Using Highly Active Supported Palladium Nanoparticles in Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid. Applied Catalysis A: General 2012, 433–434, 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Bouriazos, A.; Sotiriou, S.; Vangelis, C.; Papadogianakis, G. Catalytic Conversions in Green Aqueous Media: Part 4. Selective Hydrogenation of Polyunsaturated Methyl Esters of Vegetable Oils for Upgrading Biodiesel. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 2010, 695, 327–337. [CrossRef]

- Bouriazos, A.; Vasiliou, C.; Tsichla, A.; Papadogianakis, G. Catalytic Conversions in Green Aqueous Media. Part 8: Partial and Full Hydrogenation of Renewable Methyl Esters of Vegetable Oils. Catalysis Today 2015, 247, 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.C. Modeling and Simulation of Biphasic Catalytic Hydrogenation of a Hydroformylated Fuel. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19731–19736. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.C. Alternative Refinery Process of Fuel Catalytic Upgrade in Aqueous Media. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability 2022, 59–76. [CrossRef]

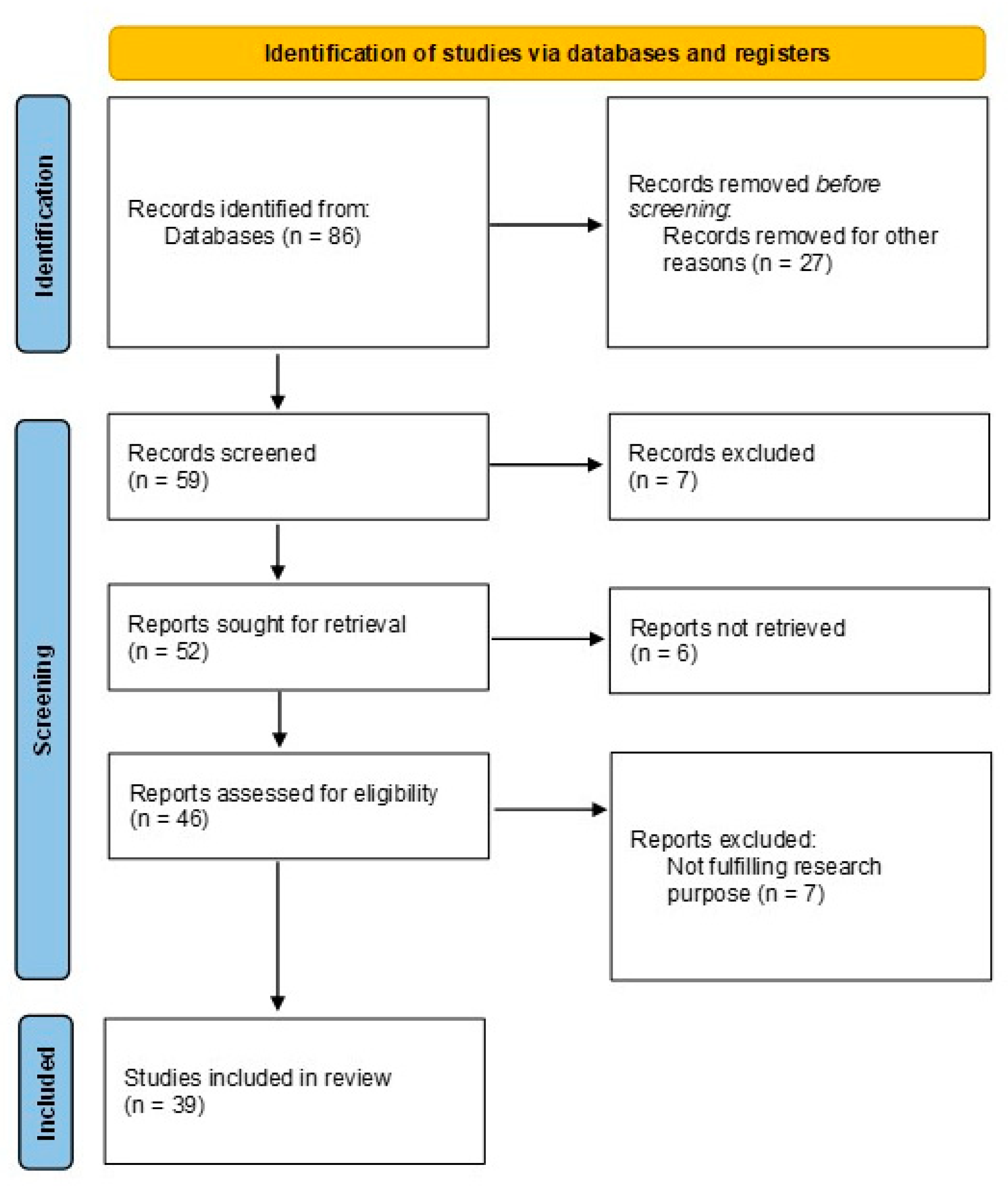

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Udomsap, P.; Meesiri, S.; Chollacoop, N.; Eiad-Ua, A. Biomass Nanoporous Carbon-Supported Pd Catalysts for Partial Hydrogenation of Biodiesel: Effects of Surface Chemistry on Pd Particle Size and Catalytic Performance. Nanomaterials 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Numwong, N.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Effect of SiO2 Pore Size on Partial Hydrogenation of Rapeseed Oil-Derived FAMEs. Applied Catalysis A: General 2012, 441–442, 72–78. [CrossRef]

- Wadumesthrige, K.; Salley, S.O.; Ng, K.Y.S. Effects of Partial Hydrogenation, Epoxidation, and Hydroxylation on the Fuel Properties of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. Fuel Processing Technology 2009, 90, 1292–1299. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Lee, J.; Seo, H.; Kang, H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, Y.-W. Evaluation of Pd/ZSM-5 Catalyst for Simultaneous Reaction of Transesterification and Partial Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil under Supercritical Methanol. Fuel Processing Technology 2021, 218. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Seo, H.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.-W. One-Pot Supercritical Transesterification and Partial Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil in the Presence of Pd/Al2O3 or Cu or Ni Catalyst without H2. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2020, 156. [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Abe, Y.; Chen, S.-Y.; Toba, M.; Yoshimura, Y. Oxygen-Assisted Hydrogenation of Jatropha-Oil-Derived Biodiesel Fuel over an Alumina-Supported Palladium Catalyst To Produce Hydrotreated Fatty Acid Methyl Esters for High-Blend Fuels. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 2633–2637. [CrossRef]

- Ramayeni, E.; Susanto, B.H.; Pratama, D.F. Palm H-FAME Production through Partially Hydrogenation Using Nickel/Carbon Catalyst to Increase Oxidation Stability.; 2018; Vol. 156.

- Quaranta, E.; Cornacchia, D. Partial Hydrogenation of a C18:3-Rich FAME Mixture over Pd/C. Renewable Energy 2020, 157, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Dibenedetto, A.; Colucci, A.; Cornacchia, D. Partial Hydrogenation of FAMEs with High Content of C18:2 Dienes. Selective Hydrogenation of Tobacco Seed Oil-Derived Biodiesel. Fuel 2022, 326. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Wei, G.; Zhang, L.; Gao, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, W. Partial Hydrogenation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters under Mild Conditions Using Sodium Borohydride as Hydrogen Donor. Fuel 2021, 299. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Wei, G.; Xin, Z.; Xiong, D.; Ou, Z. Partial Hydrogenation of Jatropha Oil Biodiesel Catalyzed by Nickel/Bentonite Catalyst. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 465–474. [CrossRef]

- Phumpradit, S.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Kuchonthara, P.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C.; Hinchiranan, N. Partial Hydrogenation of Palm Oil-Derived Biodiesel over Ni/Electrospun Silica Fiber Catalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Numwong, N.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Partial Hydrogenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Methyl Esters over Pd/Activated Carbon: Effect of Type of Reactor. Chemical Engineering Journal 2012, 210, 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Na Rungsi, A.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chollacoop, N.; Chen, S.-Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Takagi, H.; Yoshimura, Y. Preparation of MCM-41-Supported Pd–Pt Catalysts with Enhanced Activity and Sulfur Resistance for Partial Hydrogenation of Soybean Oil-Derived Biodiesel Fuel. Applied Catalysis A: General 2020, 590, 117351. [CrossRef]

- Falk, O.; Meyer-Pittroff, R. The Effect of Fatty Acid Composition on Biodiesel Oxidative Stability. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2004, 106, 837–843. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Attanatho, L.; Mochizuki, T.; Abe, Y.; Toba, M.; Yoshimura, Y.; Kumpidet, C.; Somwonhsa, P.; Lao-ubol, S. Upgrading of Palm Biodiesel Fuel over Supported Palladium Catalysts. Comptes Rendus Chimie 2016, 19, 1166–1173. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Chang, A.; Rungsi, A.N.; Attanatho, L.; Chang, C.-L.; Pan, J.-H.; Suemanotham, A.; Mochizuki, T.; Takagi, H.; Yang, C.-M.; et al. Superficial Pd Nanoparticles Supported on Carbonaceous SBA-15 as Efficient Hydrotreating Catalyst for Upgrading Biodiesel Fuel. Applied Catalysis A: General 2020, 602, 117707. [CrossRef]

- Bouriazos, A.; Mouratidis, K.; Psaroudakis, N.; Papadogianakis, G. Catalytic Conversions in Aqueous Media. Part 2. A Novel and Highly Efficient Biphasic Hydrogenation of Renewable Methyl Esters of Linseed and Sunflower Oils to High Quality Biodiesel Employing Rh/TPPTS Complexes. Catalysis Letters 2008, 121, 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Stathis, P.; Stavroulaki, D.; Kaika, N.; Krommyda, K.; Papadogianakis, G. Low Trans-Isomers Formation in the Aqueous-Phase Pt/TPPTS-Catalyzed Partial Hydrogenation of Methyl Esters of Linseed Oil. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 209, 579–590. [CrossRef]

| Feedstock | Method/ Catalyst | Reaction conditions | Upgrade | Highlights | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiesel derived from Kemiri Sunan oil | Partial hydrogenation/ NiMo/C nanocrystal catalyst Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 110 °C Pressure: 4 bar Stirring rate: 800 rpm Time: 3 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAMEs: 20.41% Selectivity to monounsaturated FAMEs: 8.87% |

Low activity and selectivity at operating conditions | [12] | ||

| Soybean oil | Simultaneous transesterification and partial hydrogenation under supercritical methanol/Cu in powder form Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 10% |

Stainless steel autoclave Temperature: 320 °C Pressure: 20 MPa Stirring rate: 1000 rpm Time: 0.5 h Methanol/oil molar ratio: 45:1 |

OS (h): 8.5 (4.6) IV (g/100g): 78 (121.3) CN: 59.4 (47.5) CFPP (°C): -1.5 (-3.1) |

Production and upgrade of biodiesel were achieved in a single step |

[19] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/C (biomass nanoporous carbon) activated with H3 PO 4 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0,1% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 0.5 MPa Stirring rate: 700 rpm Time: 0.75 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 90% Selectivity to monounsaturated FAME: 84% OS (h): 65 (13) CP (°C): 16 (14) |

Low-cost nanoporous carbon from cattail flower proved to be an effective catalyst support | [30] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/Zr-SBA-15 (Zr/Si=0.07) Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0.75% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 100 °C Pressure: 4 bar Time: 2h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 80% after 1.8 h OS (h): 53 (2) CP (°C): 7 (2) PP (°C): 3 (0) |

The presence of Zr in catalyst's surface increased its activity | [7] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from jatropha oil | Catalytic transfer hydrogenation (CTH)/ Raney-Ni Catalyst dosage: 8 %wt |

Microwave chemical reactor Temperature: 85 °C Stirring rate: 400 rpm Time: 0.83 h Hydrogen donor: isopropyl alcohol 24 g |

Mass conversion ratio of 18:2 FAME: 91.98 %wt Selectivity to monounsaturated FAMEs: 63% IV (g/100g): 70.21 (97.08) |

Microwave heating increased activity and selectivity of CTH | [22] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/SiO2 (Q30) Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1% |

batch reactor Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 4 bar Stirring rate: 1000 rpm Time: 2.5 h |

OS (h): 30.4 (1.4) CP (°C): 6 (1) |

Pd catalyst proved more suitable for the partial hydrogenation than Pt and Ni catalysts | [13] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from rapeseed oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/SiO2 (Q30) 0.3 g catalyst 180 ml biodiesel |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 0.3 MPa Stirring rate: 1000 rpm Time: 1 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 91.6% OS (h): 39 (1.9) CP (°C): 11 (-3) PP (°C): 5 (-11) |

Pd catalyst proved more suitable for the partial hydrogenation than Pt and Ni catalysts | [14] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/MCM-41 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0.5% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 100 °C Pressure: 0.4 MPa Stirring rate: 500 rpm Time: 4 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 93.4 Selectivity to cis-monounsaturated FAME: 55.2% OS (h): 11.71 (1.94) CP (°C): 15 (4) |

Catalysts with small particle sizes presented higher selectivity | [16] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from rapeseed oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/SiO2 (Q30) Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0.2% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 0.3 MPa Stirring rate: 1000 rpm Time: 1 h |

OS (h): 38.98 (1.89) CP (°C): 11 (-3) PP (°C): 5 (-11) |

Non porous and microporous supports improved the selectivity | [31] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from poultry fat | Hydrogenation/ 4%wt Pd/C catalyst B113W from Sigma Aldrich Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 3.9% |

Laboratory reactor model Parr 4575 Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 4 atm Time: 2 h |

OS (h): 11.8 (0.71) CN: 58.4 (47.3) |

The hydrogenated product was unsuitable for cold weather conditions | [32] | ||

| Soybean oil | Simultaneous transesterification and catalytic transfer hydrogenation (CTH) under supercritical methanol/ 0.5%wt Pd/ZSM-5 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0.05% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 300 °C Pressure: 10 MPa Horizontal shaking: 0.85 Hz Time: 0.5 h Methanol/oil molar ratio: 45:1 |

OS (h): 8 (4.6) CN: 60.5 (50) CFPP (°C): -4.1 (-3.8) |

High-quality biodiesel was obtained in a single step and a short time | [33] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd-Ba/SiO2 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 4 bar Stirring rate: 500 rpm Time: 4 h |

OS (h): 11.8 (2.2) CP (°C): 5.3 (4) PP (°C): 0 (-2) |

Catalyst with proper basicity presented higher activity | [18] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd-Mg/SiO2 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 4 bar Stirring rate: 1000 rpm Time: 4 h |

OS (h): 11 (2) CP (°C): 10 (7) CFPP (°C): -2 (-6) |

Catalysts with higher basicity presented higher selectivity | [8] | ||

| Soybean oil | Simultaneous transesterification and partial hydrogenation under supercritical methanol, without the use of H2 gas/ Cu Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 10% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 300 °C Pressure: 20 MPa Horizontal shaking: 0.85 Hz Time: 0.5 h Methanol/oil molar ratio: 45:1 |

OS (h): 6.3 (4.6) CN: 66.1 (50.6) CFPP (°C): -3.9 (-4.6) |

High-quality biodiesel was obtained in a single step |

[34] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from jatropha oil | Oxygen-assisted hydrogenation/ Pd/γ-Al2O3 | Up-flow fixed bed reactor Temperature: 100 °C Pressure: 0.5 MPa Time: 2 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 89% OS (h): 13.2 (0.8) PP (°C): 13 (3) |

Co-feeding of O2 the reduced the deactivation rate Drawback: not economically feasible method |

[35] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Ni/C Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 5% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 6 bar Stirring rate: 200 rpm Time: 2.5 h |

Yield of monounsaturated FAME: 9.87% Selectivity to monounsaturated FAME: 10.58 OS (h): 10.3 (9.75) IV (g/100g): 82.38 (91.78) CN: 55.59 (52.51) |

Low activity and selectivity | [36] | ||

| Biodiesel model from pure compounds | Partial hydrogenation/ 5.7%wt Pd/C commercial catalyst 50 mg Catalyst 1 ml FAME mixture |

Schlenck tube Temperature: 50 °C Pressure: 1 atm Time: 1 h Solvent: 5 ml n-heptane |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 82.9% Yield of monounsaturated FAME: 81.1% Selectivity to monounsaturated FAME: 97.8% Selectivity to cis-monounsaturated FAME: 51.5% |

Successful partial hydrogenation was achieved under uncommon mild conditions using n-heptane as solvent | [37] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from tobacco seed oil | Partial hydrogenation/ 5.7%wt Pd/C commercial catalyst |

Schlenck tube Temperature: 15 °C Pressure: 0.1 MPa Stirring rate: 300 rpm Time: 1 h Solvent: 5 ml n-heptane |

Conversion of 18:2-FAME: 97% Yield of monounsaturated FAME: 91.3% Selectivity to monounsaturated FAME: 94.1% Selectivity to cis-monounsaturated FAME: 43% OS (h): 61.8 (4.3) IV (g/100g): 82.9 (145.6) CN: 55 (40.8) CP (°C): -2.8 (-2.7) PP (°C): -9.8 (-9.8) CFPP (°C): -6.4 (-12.4) |

Successful partial hydrogenation was achieved under uncommon mild conditions using n-heptane as solvent | [38] | ||

| Biodiesel model from pure compounds | Catalytic transfer hydrogenation using NaBH4 as hydrogen donor/ Ni-La-B Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 10 %wt |

Three-neck glass flask Temperature: 85 °C Time: 2.5 h Hydrogen donor: 1.14 g NaBH 4 |

Conversion of 18:2-FAME: 95.4% OS (h): 35.3 (4.1) IV (g/100g): 76.1 (151.9) |

NaBH4 is an effective hydrogen donor for CTH process | [39] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from jatropha oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Ni/ Bentonite Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 3.33 %wt |

Temperature: 200 °C Pressure: 0.3 MPa Stirring rate: 400 rpm Time: 1 h |

Conversion of 18:2-FAME: 75% OS (h): 18 (6.5) CP (°C): 0.8 (0.8) CFPP (°C): 10 (-3.5) |

The catalyst did not show any decrease in its activity after 5 reuses | [40] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ 30%wt Ni/Electrospun silica fiber 0.4 g catalyst |

Continuous fixed bed reactor Temperature: 140 °C Pressure: 1 bar Time 4 h Biodiesel feed rate: 0.44 g min-1 |

Conversion of 18:2-FAME: 71.3% OS (h): 23 (16) PP (°C): 20 (16) FP (°C): 184 (184) |

The catalyst is not stable enough for commercial application | [41] | ||

| Commercial biodiesel | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/activated carbon Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1.5% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 0.4 MPa Stirring rate: 500 rpm Time: 1.5 h |

Conversion of polyunsaturated-FAME: 94.5% OS (h): 32.5 (1.49) CP (°C): 23 (16) PP (°C): 22 (16) |

Hydrogenation in batch type reactor was more selective than in continuous flow-type reactor | [42] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ in situ sulfur poisoned Pd-Pt/MCM-41(1:1) Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 1% |

Semi-batch reactor Temperature: 100 °C Pressure: 0.4 MPa Stirring rate: 500 rpm Time: 4 h Additional sulphur content: 2 ppm |

OS (h): 65 (0.6) CP (°C): 7 (2) |

Bimetallic Pd-Pt (1:1) catalyst was more active than Pd and Pt catalysts. Poisoned Pd-Pt/MCM-41(1:1), catalyst presented higher selectivity. |

[43] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/ Pd/ImS3-12@Al2O3 in BMIM-NTf2 ionic liquid 1.3 μmol Pd 6 mL biodiesel |

Stainless steel autoclave Temperature: 27 °C Pressure: 75 atm Stirring rate: 500 rpm Time: 4 h 1 mL BMIM-NTf2 |

OS (h): 28 (<1) | The catalyst was obtained easily and showed good recyclability due to phase separation between ionic liquids and the hydrogenated products | [24] | ||

| a) Biodiesel derived from used cooking oils and b) Biodiesel derived from fats from rendering plants |

Hydrogenation/ Nickel catalyst B113W from Degussa Ni content: 0.4 %wt Hydrogen content: 5 %wt |

Laboratory autoclave Temperature: 180 °C Pressure: 400 kPa Time: a) 2 h and b) 3 h |

OS (h): a) 93.6 (3.9) and b) 35.3 (1.3) |

Hydrogenation increased biodiesel's oxidative stability | [44] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ 0.5wt% Pd/SBA-15 | Fixed bed reactor Temperature: 100 °C Pressure: 0.3 MPa TOS: 28 h 0.37 g min-1 biodiesel |

Conversion of poly-FAME: 36.4% Selectivity to cis-monounsaturated FAME: 86.4% OS (h): 27.9 (19.4) CP (°C): 13 (12) PP (°C): 12 (12) |

Catalyst with high metal dispersion, weak acidity framework, and fast molecular diffusion presented higher activity and selectivity | [45] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ 1%wt Pd/SBA-15 Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 0.3% |

Batch reactor Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 0.5 MPa Stirring rate: 1000 rpm |

OS (h): 28 (5.1) CP (°C): 17 (13) PP (°C): 16 (13) |

Catalyst with higher Pd particle dispersion and well-ordered pore channels exhibited higher activity and tolerance to impurities | [21] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation using DBD plasma reactor/ Raney-Nickel Catalyst/oil mass ratio: 3% |

DBD plasma reactor Biodiesel Temperature: 25 °C Pressure: 0.1 MPa Time: 1.5 h Circulation flow rate: 40 mL/min Working Voltage: 17.68 kV |

Conversion of poly-unsaturated FAME: 57.04% Selectivity to mono-unsaturated FAME: 77.75% |

Successful biodiesel upgrade took place under room temperature and atmospheric pressure in DBD plasma reactor | [23] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from palm oil | Partial hydrogenation/ Pd/SBA-15 Pd/oil mass ratio: 6.67*10 -5 |

Batch type reaction system Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 0.5 MPa Stirring rate: 1000 rpm |

Conversion of polyunsaturated FAME: 90% after 0.3 h | The Pd/SBA-15 prepared catalyst presented higher activity and selectivity than the commercial Pd/C catalyst | [46] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from linseed oil | Partial hydrogenation in biphasic aqueous/organic system / Rh/TPPTS TPPTS/Rh molar ratio: 4 C=C/Rh molar ratio: 500 |

Autoclave Temperature: 80 °C Pressure: 10 bar Stirring rate: 770-850 rpm Time: 2 h |

Selectivity to mono-unsaturated FAME: 79.8% | Easy catalyst by simple two -phase separation. Activity remained at the same level after consecutive runs | [47] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation in biphasic aqueous/organic system / Rh/TPPTS TPPTS/Rh molar ratio: 5 C=C/Rh molar ratio: 2500 |

Autoclave Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 10 bar Stirring rate: 770 rpm Time: 0.17 h |

Increase of monounsaturated FAME (mol%): 68.6 (26.6) | Activity and selectivity remained at the same levels after three consecutive runs | [25] | ||

| Biodiesel derived from soybean oil | Partial hydrogenation in biphasic aqueous/organic system / Pd/BPhDS BPhDS/Pd molar ratio: 1 C=C/Pd molar ratio: 10 000 |

Autoclave Temperature: 120 °C Pressure: 20 bar Stirring rate: 620-850 rpm Time: 0.08 h |

Selectivity to monoun-saturated FAME: 78.4% | The use of water-soluble nitrogen containing ligands increased the catalytic activity | [26] | ||

| FAMEs mixture derived from linseed oil | Partial hydrogenation in biphasic aqueous/organic system / Pt/TPPTS TPPTS/Pt molar ratio: 12 C=C/Pt molar ratio: 1000 |

Autoclave Temperature: 60 °C Pressure: 30 bar Stirring rate: 700 rpm Time: 0.33 h |

IV: 85 (202) | Very low selectivity to trans-monounsaturated FAMEs and saturated FAMEs. Drawback: the catalyst decomposes |

[48] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).