Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

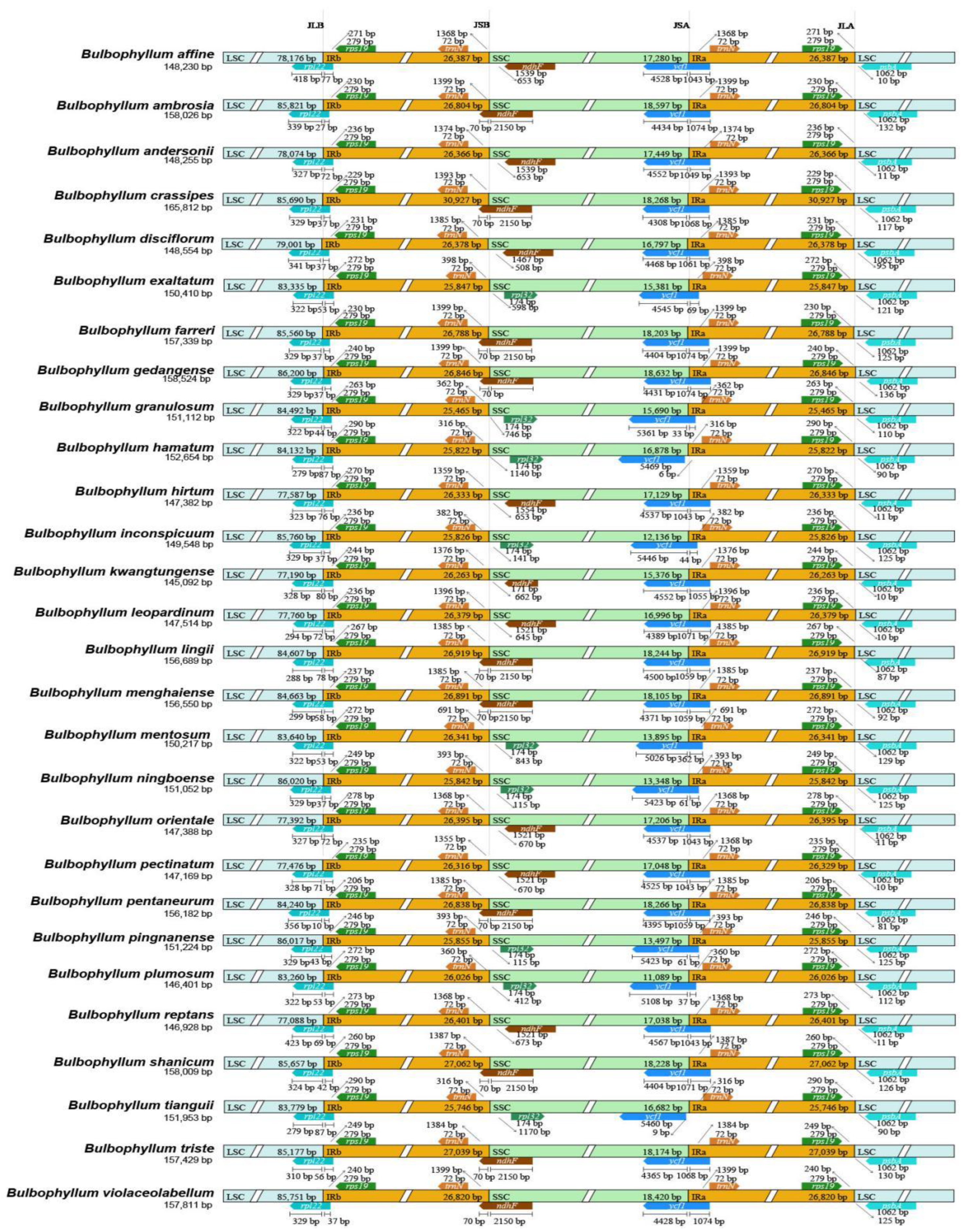

2.1. General Characteristics of the Chloroplast Genomes

2.2. Repeat Sequence Characterization

2.3. Relative Synonymous Codon Usage Analysis

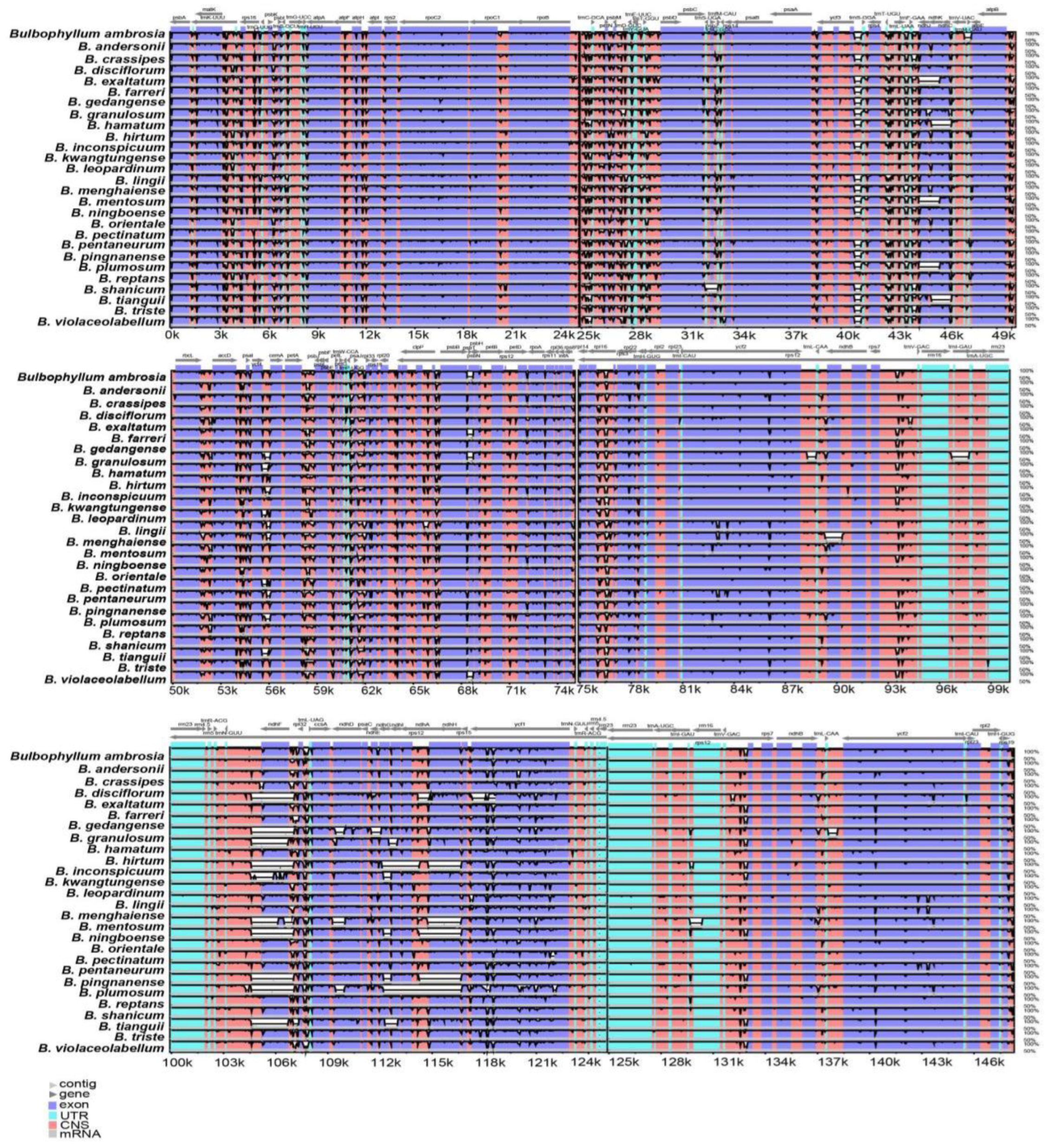

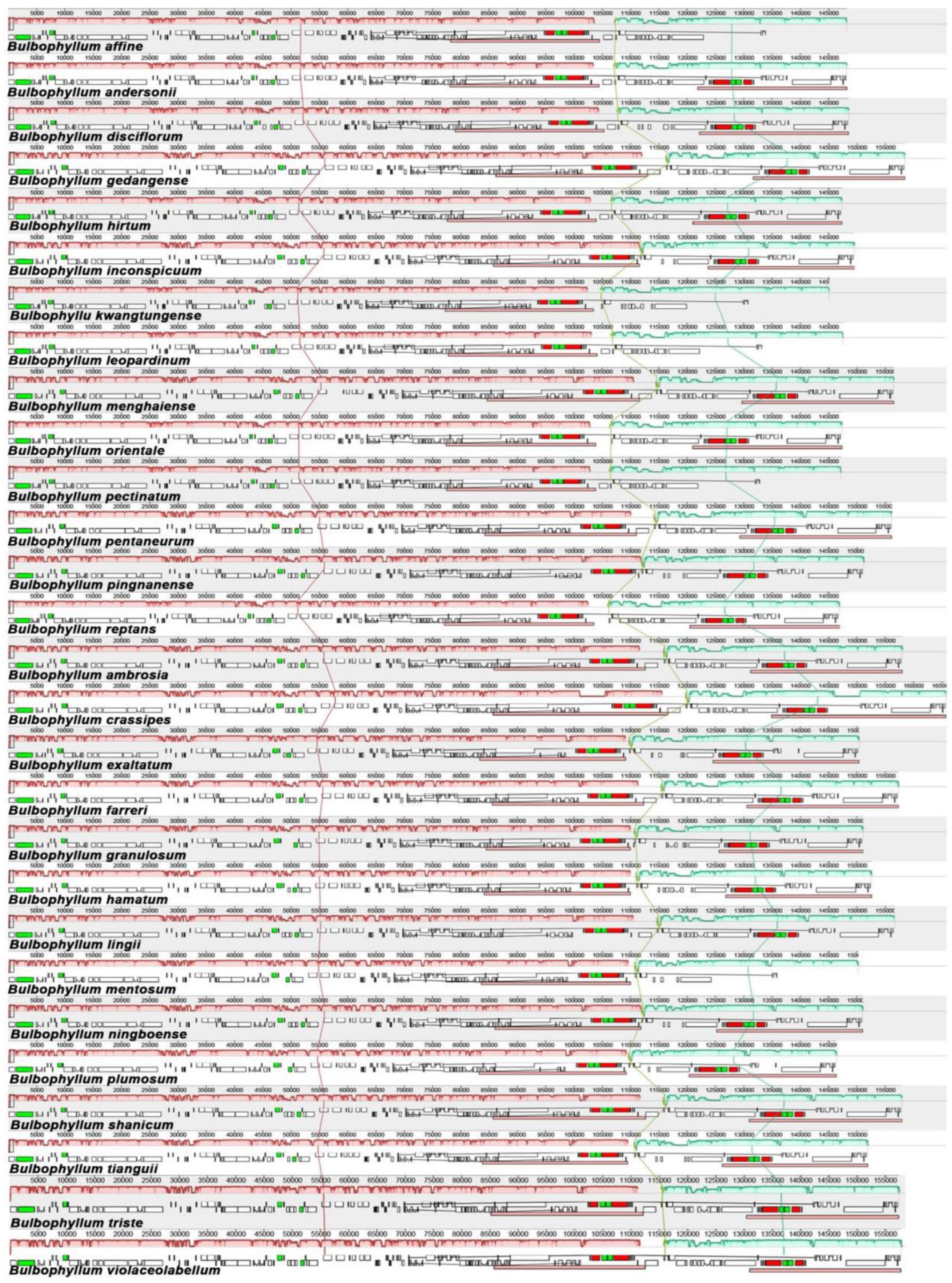

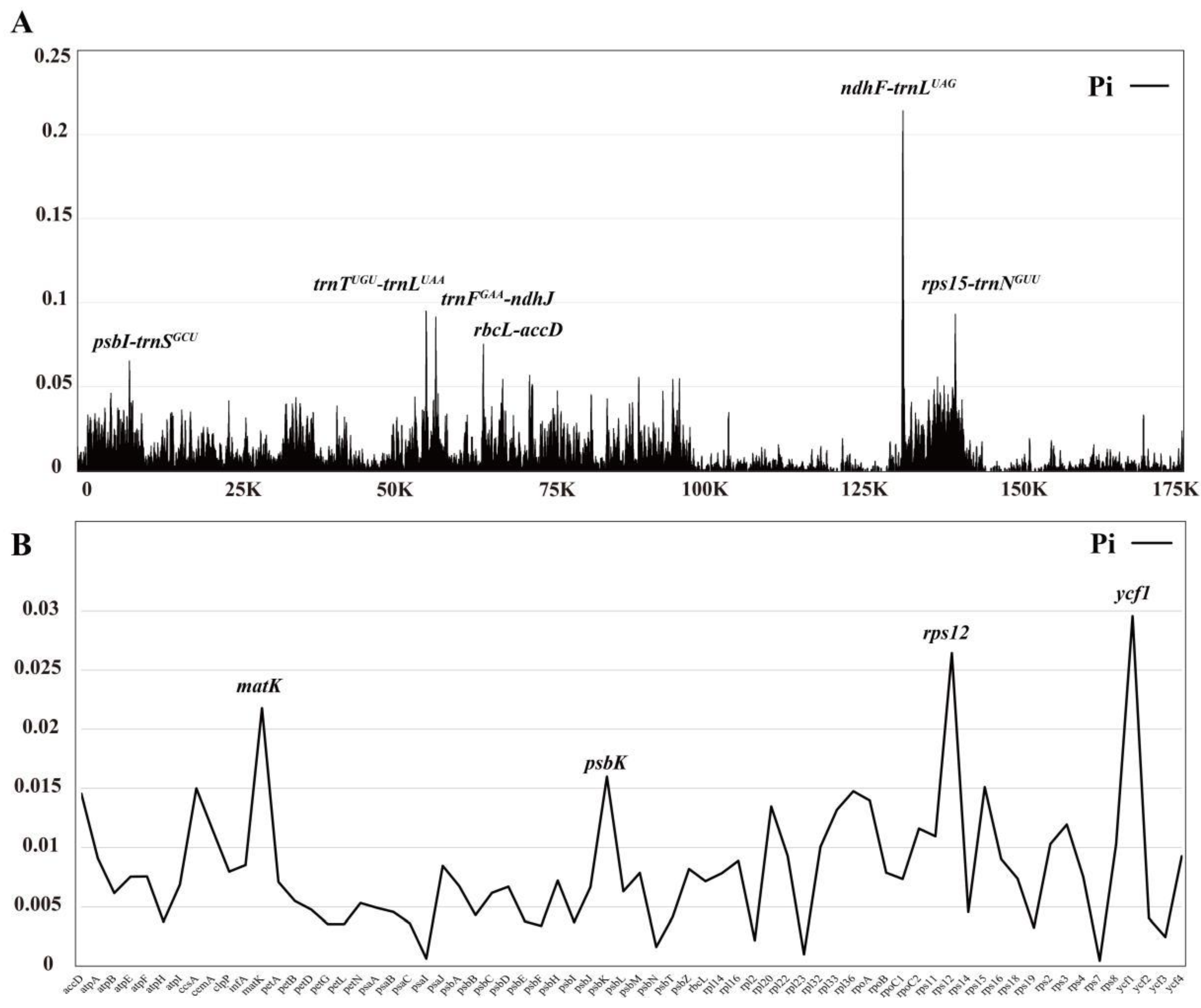

2.4. Expansion and Contraction of IRs, Sequence Divergence and Nucleotide Diversity

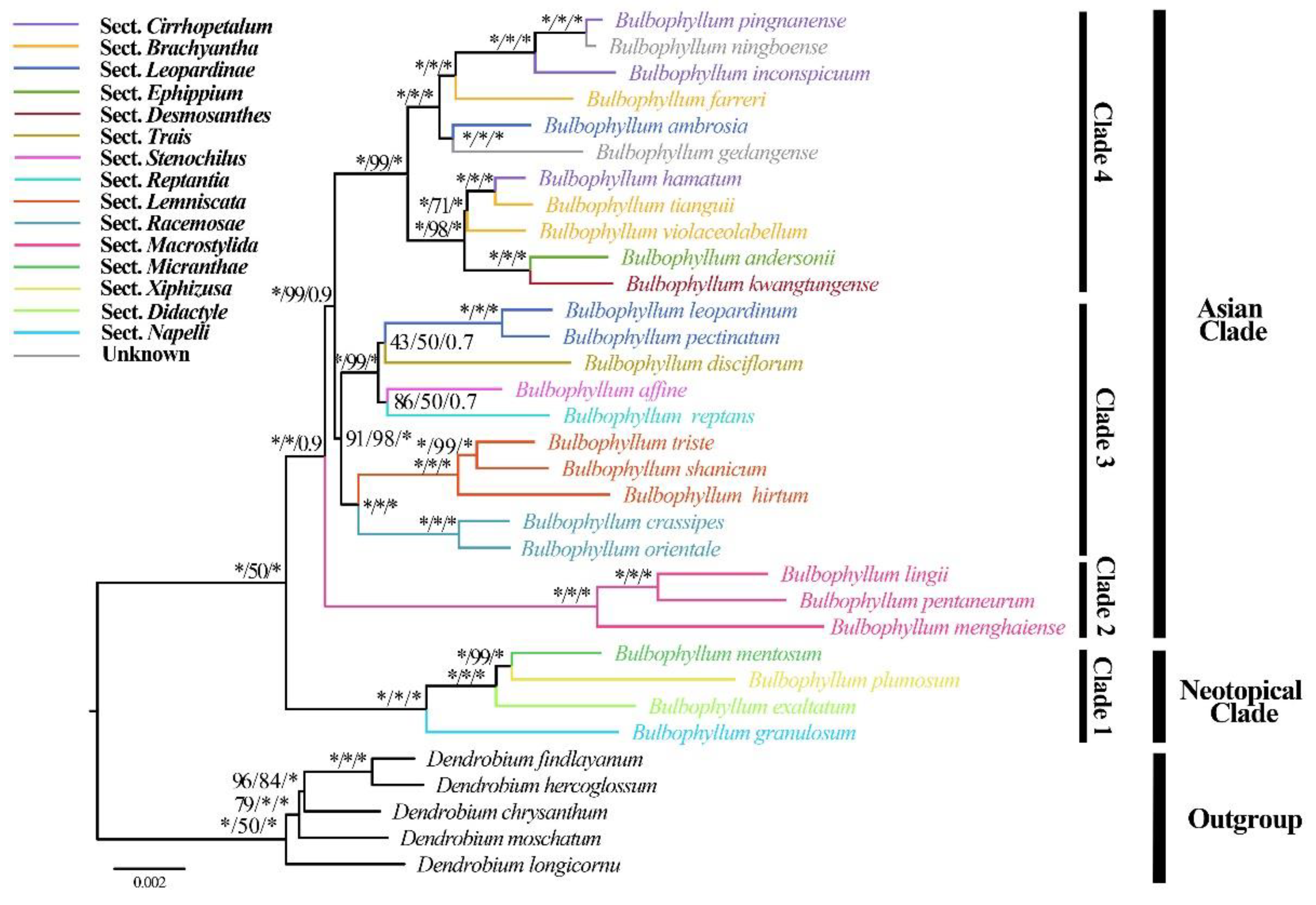

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. The Characteristics of Chloroplast Genomes

3.2. Repeat Sequence Analysis

3.3. Codon Usage Analysis

3.4. Expansion and Contraction of IRs, Sequence Divergence and Nucleotide Diversity

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Taxon Sampling and DNA Sequencing

4.2. Chloroplast Genome Assembly and Annotation

4.3. Repeat sequence Characterization

4.4. Relative Synonymous Codon Usage Analysis

4.5. Genome Structure Comparisons and Sequence Divergence Analysis

4.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gravendeel, B.; Smithson, A.; Slik, F.J.W.; Schuiteman, A. Epiphytism and pollinator specialization: Drivers for orchid diversity? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamisch, A.; Comes, H.P. Clade-age-dependent diversification under high species turnover shapes species richness disparities among tropical rainforest lineages of Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae). BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Pridgeon, A.M.; Cribb, P.J.; Chase, M.W.; Rasmussen, F.N. Genera Orchidacearum Vol. 6 Epidendroideae; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–687. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A.-Q.; Gale, S.W.; Liu, Z.-J.; Suddee, S.; Hsu, T.-C.; Fischer, G.A.; Saunders, R.M.K. Molecular phylogenetics and floral evolution of the Cirrhopetalum alliance (Bulbophyllum, Orchidaceae): Evolutionary transitions and phylogenetic signal variation. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2020, 143, 106689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, R.L. Phylogeny and Classification of the Orchid Family; Dioscorides Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1993; pp. 1–311. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-G.; Xu, J.-J.; Yu, H.; Qing, C.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Wang, L.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.-H. Cytotoxic phenolics from Bulbophyllum odoratissimum. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitharani, S.; Mohan, V.R.; Maruthupandian, A. Pharmacognostic investigations on Bulbophyllum albidum (Wight) Hook. F. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2011, 3, 556–562. [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach, H.G. Catalog der Orchideen-Sammlung von G.W. Schiller zu Overlgönne an der Elbe. Annal, Botan. System. 1861, 6, 264. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, G. Notes on Orchideæ. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1881, 18, 281–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentham, G.; Hooker, J.D. Orchideae. In Genera Plantarum: Ad Exemplaria Imprimis in Herberiis Kewensibus Servata Definite, 1st ed.; Lovell Reeve & Co., Limited: London, UK, 1883; Volume 3, pp. 466–636. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/186440#page/768/mode/1up (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Seidenfaden, G.; Wood, J.J.; Holttum, R.E. The Orchids of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore; Olsen: Tokyo, Japan, 1992; pp. 1–779. [Google Scholar]

- Garay, L.A.; Hamer, F.; Siegerist, E.S. The genus Cirrhopetalum and the genera of the Bulbophyllum alliance. Nord J Bot. 1994, 14, 609–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.A.; Jones, D.L. Nomenclatural changes in the Australian and New Zealand Bulbophyllinae and Eriinae (Orchidaceae). The orchadian 2002, 13, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, J.J.; Schuiteman, A.; De Vogel, E.F. Nomenclatural changes in Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae). Phytotaxa 2014, 166, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidenfaden, G. Orchid Genera in Thailand VIII: Bulbophyllum Thou. Dansk Bot. Ark. 1979, 33, 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, M.W.; Cameron, K.M.; Freudenstein, J.V.; Pridgeon, A.M.; Salazar, G.; Van den Berg, C.; Schuiteman, A. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 177, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamisch, A.; Winter, K.; Fischer, G.A. Evolution of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) as an escape from ecological niche conservatism in Malagasy Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae). New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Li, X.-W.; Wu, J. Bulbophyllum hamatum (Orchidaceae), a new species from Hubei, central China. Phytotaxa 2021, 523, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wu, P.-Y.; Xu, X.-W.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Y.-J.; Liu, Z.-J. Bulbophyllum contortum (Orchidaceae, Malaxideae), a new species from Yunnan, China. Phytotaxa 2022, 560, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.-L.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Zhu, W.-T.; Liu, Z.; Ji, H.-Y.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zhai, J.-W. Bulbophyllum deergongense (Dendrobiinae; Malaxideae; Epidendroideae; Orchidaceae), a new species from Tibet, China. Phytotaxa 2023, 619, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Xu, C.; Cheng, T.; Lin, K.; Zhou, S. Sequencing Angiosperm Plastid Genomes Made Easy: A Complete Set of Universal Primers and a Case Study on the Phylogeny of Saxifragales. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013, 5, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Shi, T.; Luo, W.; Ni, X.; Iqbal, S.; Ni, Z.; Huang, X.; Yao, D.; Shen, Z.; Gao, Z. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome among Prunus mume, P. armeniaca, and P. salicina. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.-K.; Tu, X.-D.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, M.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Wang, M.-M.; Liu, Z.-J.; Lan, S.R.; et al. Plastid phylogenomic data yield new and robust insights into the phylogeny of Cleisostoma-Gastrochilus clades (Orchidaceae, Aeridinae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 145, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Wu, K.; Fang, L.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, S. Comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationships of thirteen Pholidota species (Orchidaceae) inferred from complete chloroplast genomes. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Peng, D. Complete Chloroplast Genomes and Comparative Analyses of Three Paraphalaenopsis (Aeridinae, Orchidaceae) Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-P.; Zhang, F.-W.; Ge, Y.-J.; Yu, W.-H.; Xue, Q.-Q.; Wang, M.-T.; Wang, H.-M.; Xue, Q.-Y.; Liu, W.; Niu, Z.-T.; et al. Effects of geographic isolation on the Bulbophyllum chloroplast genomes. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.-N.; Lao, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.-X.; He, W.; Zhong, C.; Xie, J.; Zhang, S.-H.; Jin, J. Characterization of the chloroplast genome of medicinal herb Polygonatum cyrtonema and identification of molecular markers by comparative analysis. Genome 2023, 66, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-H.; Ding, L.-N.; Zong, X.-Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, W.-B.; Ding, R.; Qu, B. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of four Liparis species (Orchidaceae) and phylogenetic implications. Gene 2023, 888, 147760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Tang, L.; Shao, S.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Luo, Y. Chloroplast genomic diversity in Bulbophyllum section Macrocaulia (Orchidaceae, Epidendroideae, Malaxideae): Insights into species divergence and adaptive evolution. Plant Divers. 2021, 43, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, F.; Logacheva, M.; Le Clainche, I.; Berard, A.; Zheleznaia, E.; May, M.; Jakalski, M.; Delannoy, E.; Le Paslier, M.C.; Selosse, M.A. Thirteen new plastid genomes from mixotrophic and autotrophic species provide insights into heterotrophy evolution in Neottieae orchids. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.-D.; Liu, D.-K.; Xu, S.-W.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Gao, X.-Y.; Zeng, M.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.-L.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Plastid phylogenomics improves resolution of phylogenetic relationship in the Cheirostylis and Goodyera clades of Goodyerinae (Orchidoideae, Orchidaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 164, 107269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavala-Páez, M.; Vieira, L.D.N.; Baura, V.A.D.; Balsanelli, E.; Souza, E.M.D.; Cevallos, M.C.; Smidt, E.D.C. Comparative plastid genomics of neotropical Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mower, J.P.; Vickrey, T.L. Structural diversity among plastid genomes of land plants. In Advances in Botanical Research; Chaw, S.M., Jansen, R.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 58, pp. 263–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shao, B.; Li, J.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Jin, X. The extremely reduced, diverged and reconfigured plastomes of the largest mycoheterotrophic orchid lineage. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-K.; Tang, L.; Deng, J.-P.; Tang, H.-Q.; Shao, S.-C.; Xing, Z.; Luo, Y. Comparative chloroplast genomics of three species of Bulbophyllum section Cirrhopetalum (Orchidaceae), with an emphasis on the description of a new species from Eastern Himalaya. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, F.; Chen, Y.; Ding, X. Comparative plastomic analysis of three Bulbophyllum medicinal plants and its significance in species identification. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2020, 55, 2736–2745. [Google Scholar]

- Sazanov, L.A.; Burrows, P.A.; Nixon, P.J. The plastid ndh genes code for an NADH-specific dehydrogenase: isolation of a complex I analogue from pea thylakoid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.L.; Wicke, S.; Li, J.W.; Han, Y.; Lin, C.S.; Li, D.Z.; Zhou, T.T.; Huang, W.C.; Huang, L.Q.; Jin, X.H. Lineage-specific reductions of plastid genomes in an orchid tribe with partially and fully mycoheterotrophic species. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Pan, J.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Ding, X. Comparative analysis of Dendrobium plastomes and utility of plastomic mutational hotspots. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2073. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, I.C.; Liao, D.C.; Wu, F.H.; Daniell, H.; Singh, N.D.; Chang, C.; Shih, M.C.; Chan, M.T.; Lin, C.S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of an orchid model plant candidate: Erycina pusilla apply in tropical Oncidium breeding. PloS one 2012, 7, e34738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Sabater, B. Plastid ndh genes in plant evolution. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, D.D.; D'Andrea, L.; Bock, R. The plastid NAD (P) H dehydrogenase-like complex: structure, function and evolutionary dynamics. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 2743–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Zhang, S.-N.; Xiong, J.-S.; Lin, Z.G.; Cheng, Z.-M.; Liu, Z.-J. Origin and mechanism of crassulacean acid metabolism in orchids as implied by comparative transcriptomics and genomics of the carbon fixation pathway. The Plant J. 2016, 86, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, A.-Q.; Gale, S.W.; Liu, Z.-J.; Fisher, G.A.; Saunders, R.M.K. Diversification slowdown in the Cirrhopetalum alliance (Bulbophyllum, Orchidaceae): Insights from the evolutionary dynamics of crassulacean acid metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 794171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjala, C.; Wanga, V.O.; Odago, W.; Mutinda, E.S.; Waswa, E.N.; Oulo, M.A.; Mkala, E.M.; Kuja, J.; Yang, J.X.; Dong, X.; et al. Plastome structure of 8 Calanthe s.l. species (Orchidaceae): comparative genomics, phylogenetic analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, D.A.; Yaradua, S.S.; Albokhari, E.J.; Abba, A. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Barleria prionitis, comparative chloroplast genomics and phylogenetic relationships among Acanthoideae. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, J.; Powell, W.; Hollingsworth, P.M. Chloroplast microsatellites: New tools for studies in plant ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, S.L.; Chan, W.S.; Janna, O.A.; Parameswari, N. Development of expressed sequence tag resources for Vanda Mimi Palmer and data mining for EST-SSR. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 3903–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanga, J.Y.; Lua, J.J.; Qiua, S.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, H.Z. Dendrobium SSR markers play a good role in genetic diversity and phylogenetic analysis of Orchidaceae species. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 183, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablok, G.; Mudunuri, S.B.; Patnana, S.; Popova, M.; Fares, M.A.; Porta, N.L. ChloroMitoSSRDB: open source repository of perfect and imperfect repeats in organelle genomes for evolutionary genomics. DNA Res. 2013, 20, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.L.; Gao, L.M.; Lu, L. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Magnolia kwangsiensis (Magnoliaceae): Implication for DNA barcoding and population genetics. Genome Biol. 2011, 54, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, S.T.; Udayasuriyan, V.; Bhadana, V. Codon usage bias. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, L.; Gu, X.; Zhong, Y. Comparative Analysis of Codon Usage Patterns Among Mitochondrion, Chloroplast and Nuclear Genes in Triticum aestivum L. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, J.; Yang, J.; Dong, X.; Zhong, Z.; Mwachala, G.; Zhang, C.; Hu, G.; Wang, Q. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of six Kenya Polystachya (Orchidaceae) species based on the complete chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Duan, H.; Tao, K.; Luo, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, L. Complete chloroplast genome structural characterization of two Phalaenopsis (Orchidaceae) species and comparative analysis with their alliance. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, A.; Ul Rehman, W.; Kaur, A.; Das, S.; Joseph, J.; Singh, A.; Bhardwaj, P. Comprehensive Codon Usage Analysis Across Diverse Plant Lineages. bioRxiv 2023, 567812. [Google Scholar]

- Chumley, T.W.; Palmer, J.D.; Mower, J.P.; Fourcade, H.M.; Calie, P.J.; Boore, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium × hortorum: Organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006, 23, 2175–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.; Resende-Moreira, L.C.; Buzatti, R.; Nazareno, A.G.; Carlsen, M.; Lobo, F.P. Chloroplast genomes of Byrsonima species (Malpighiaceae): Comparative analysis and screening of high divergence sequences. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.-L.; Wang, R.-N.; Zhang, N.-Y.; Fan, W.-B.; Fang, M.-F.; Li, Z.-H. Molecular evolution of chloroplast genomes of orchid species: Insights into phylogenetic relationship and adaptive evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.A.; Sieder, A.; Cribb, P.J.; Kiehn, M. Description of two new species and one new section of Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) from Madagascar. Adansonia sér 2007, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.; Dadkhah, K.; Go, R. Molecular systematics of genus Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) in Peninsular Malaysia based on combined nuclear and plastid DNA sequences. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 65, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-L.; Li, X.-P.; Zhang, J.-H.; Shen, B. Bulbophyllum ningboense, a new species of Orchidaceae from Zhejiang, China. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University 2014, 31, 847–849. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J.-P.; Peng, Y.-L.; Li, J.-W. Bulbophyllum gedangense (Orchidaceae, Epidendroideae, Malaxideae), a new species from Tibet, China. Phytotaxa, 2020, 453, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Y.; Liu, Z.-J.; Wu, X.-Y.; Huang, J.-X. Bulbophyllum lipingtaoi, a new orchid species from China: evidence from morphological and DNA analyses. Phytotaxa 2017, 295, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S. A Modified CTAB Protocol for Plant DNA Extraction. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2013, 48, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Schultz, M.B.; Zobel, J.; Holt, K.E. Bandage: Interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3350–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.-J.; Moore, M.J.; Li, D.-Z.; Yi, T.-S. PGA: A software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, S.K.; Jansen, R.K.; Boore, J.L. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3252–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Choudhuri, J.V.; Ohlebusch, E.; Schleiermacher, C.; Stoye, J.; Giegerich, R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 4633–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, R.A.M.; Chen, Z.J. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (2nd Ed.). Measurement 2019, 17, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, J.F. Analysis of Codon Usage. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 1, W273–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, A.C.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Bio. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutierrez, S.; Silla-Martinez, J.M.; Gabaldon, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Gatew. Comput. Environ. Workshop. 2010, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A.; Hoover, P.; Rougemont, J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 2008, 57, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits of phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. Mrbayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Specimen voucher | Accession No. |

Size (bp) | Number of genes (unique) |

Protein-coding genes (unique) |

tRNA genes (unique) | rRNA genes (unique) | ndh genes loss/pseudogenization | GC% (Total) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | LSC | SSC | IR | |||||||||

| B. affine | - | LC556091 | 148,230 | 78,178 | 17,280 | 26,386 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.86 |

| B. ambrosia | * | * | 158,026 | 85,821 | 18,622 | 26,804 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.95 |

| B. andersonii | Yang202201 | LC703293 | 148,255 | 78,074 | 17,449 | 26,366 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.83 |

| B. crassipes | * | * | 165,812 | 85,690 | 18,293 | 30,927 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.29 |

| B. disciflorum | - | LC498826 | 148,554 | 79,001 | 16,797 | 26,378 | 131 (112) | 77 (70) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 1/8 | 37.94 |

| B. exaltatum | Fiorini 218 (HBCB) | NC_048480 | 150,410 | 83,335 | 15,380 | 25,847 | 129 (110) | 76 (70) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 3/7 | 36.80 |

| B. farreri | * | * | 157,339 | 85,560 | 18,228 | 26,788 | 132 (113) | 86(79) | 38(30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.96 |

| B. gedangense | Y. Luo et al., 1239 | MW161053 | 158,524 | 86,200 | 18,632 | 26,846 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38(30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.80 |

| B. granulosum | Mancinelli 1059 (UPCB) | NC_048481 | 151,112 | 84,492 | 15,690 | 25,465 | 128 (110) | 76 (69) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 7/2 | 36.70 |

| B. hamatum | * | * | 152,654 | 84,132 | 16,881 | 25,822 | 128 (113) | 80 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 4/2 | 36.95 |

| B. hirtum | Yang202105 | LC642724 | 147,382 | 77,587 | 17,129 | 26,333 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.96 |

| B. inconspicuum | PDBK2012-0213 | MN200377 | 149,548 | 85,760 | 12,136 | 25,826 | 127 (108) | 78 (71) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 5/3 | 37.00 |

| B. kwangtungense | Yang202107 | LC642722 | 145,092 | 77,192 | 15,376 | 26,262 | 129 (110) | 82 (75) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 3/1 | 37.98 |

| B. leopardinum | Yang202102 | LC642723 | 147,514 | 77,762 | 16,996 | 26,378 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 38.04 |

| B. lingii | Y. Luo et al., 2247 | MW161052 | 156,689 | 84,607 | 18,244 | 26,919 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.80 |

| B. menghaiense | XY Wang & ZF Xu 202,003 | MW161050 | 156,550 | 84,663 | 18,105 | 26,891 | 131 (112) | 85 (78) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.70 |

| B. mentosum | Fiorini 323 (HBCB) | NC_048482 | 150,217 | 83,640 | 13,895 | 26,341 | 125 (106) | 74 (68) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 7/5 | 36.70 |

| B. ningboense | - | MW683325 | 151,052 | 86,020 | 13,348 | 25,842 | 128 (109) | 80 (73) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 4/2 | 37.00 |

| B. orientale | Yang202104 | LC642725 | 147,388 | 77,392 | 17,206 | 26,395 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 38.01 |

| B. pectinatum | - | LC556092 | 147,169 | 77,478 | 17,529 | 26,081 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 38.01 |

| B. pentaneurum | Y. Luo et al., 2252 | MW161051 | 156,182 | 84,240 | 18,266 | 26,838 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.80 |

| B. pingnanense | J.F. Liu 201312 | MW822749 | 151,224 | 86,017 | 13,497 | 25,855 | 128 (109) | 80 (73) | 38 (30) | 8(4) | 4/2 | 37.00 |

| B. plumosum | Imig 606 (HAC) | NC_048479 | 146,401 | 83,260 | 11,089 | 26,026 | 125 (106) | 74 (68) | 38 (30) | 8(4) | 7/5 | 36.60 |

| B. reptans | Yang202106 | LC642726 | 146,928 | 77,088 | 17,038 | 26,401 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.98 |

| B. shanicum | * | * | 158,009 | 85,657 | 18,253 | 27,062 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.99 |

| B. tianguii | - | MZ983368 | 151953 | 83,780 | 16,683 | 25746 | 127 (108) | 77 (70) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | 5/4 | 37.00 |

| B. triste | * | * | 157,429 | 87,177 | 18,199 | 27,039 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 37.04 |

| B. violaceolabellum | * | * | 157,811 | 85,751 | 18,445 | 26,820 | 132 (113) | 86 (79) | 38 (30) | 8 (4) | -/- | 36.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).