1. Introduction

Arsenic is considered one of the most harmful elements against humans and the environment, moreover, this element is labelled as one of the

metals of murder [

1]. Its presence in the environment is due both natural and anthropogenic causes, being its toxicity depending upon the form in which appeared in gases or liquid effluents, and whereas arsine gas is one of the most toxic gases, in liquid effluents arsenic can occurred as arsenic(III) and arsenic(V), and both oxidations states also as inorganic and organic species. The order of toxicity can be established as: inorganic As(III)> organic As(III)> inorganic As(V)> organic As(V).

Thus, the presence of these species in liquid effluents and drinking waters is the responsible of humans and life poisoning around the world, problem that does not only exists in less developed countries, but also in industrialized ones [

2]. Upon

ingesta, the presence of the above arsenic species in the organism causes different diseases including cancer [

3,

4]. The máximum contaminant limit for arsenic in drinking water set by the EPA is 10 μg/L [

5].

Besides the above, arsenic is also presented in metallurgical plants, being probably the most noticeable example the case of copper pyrometallurgical plants. Arsenic is one of the impurities normally found in copper concentrates, and usually accompanied to copper along all the pyrometallurgical process (reverberation, conversion and electrorefining operations), until its appearance in the copper electrolyte. At this stage, the increase of arsenic concentration in the electrolyte resulted in the loss of electrolyte properties, thus, it is necessary a bleed-off to maintain electrolyte properties. From this bleeding, arsenic is separate from sulphuric acid by solvent extraction and recovered in the best suitable form.

From the above, the removal of arsenic from the various arsenic-bearing solutions if of a necessity, and in the particular arsenic(V) case, several technologies has been proposed, first to isolate the element in a solution, and after to recover it in the most suitable form.

Thus, some very recent investigations aimed to the removal of arsenic(V) from aqueous solutions included: solvent extraction, ion exchange, adsorption and bioadsorption, etc [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Though neglected by some authors, solvent extraction, if properly conducted, has the advantages, from other separation technologies, that provided a reasonable easiness of scaling up, selectivity, very short operational times and the possibility of the treatment of large volumes of contaminated waters (solutions) at these short times.

This work presented an investigation about the removal of arsenic(V) from aqueous wastes using liquid-liquid extraction with Cyanex 923 extractant. Several variables influencing the extraction step are consider as well as these relative to the stripping step. The extraction of arsenic was compared with these of other metals and with the performance of other solvation extractants. Finally, the recovery of arsenic from strip solutions is proposed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Arsenic (V) and Sulphuric Acid Extraction

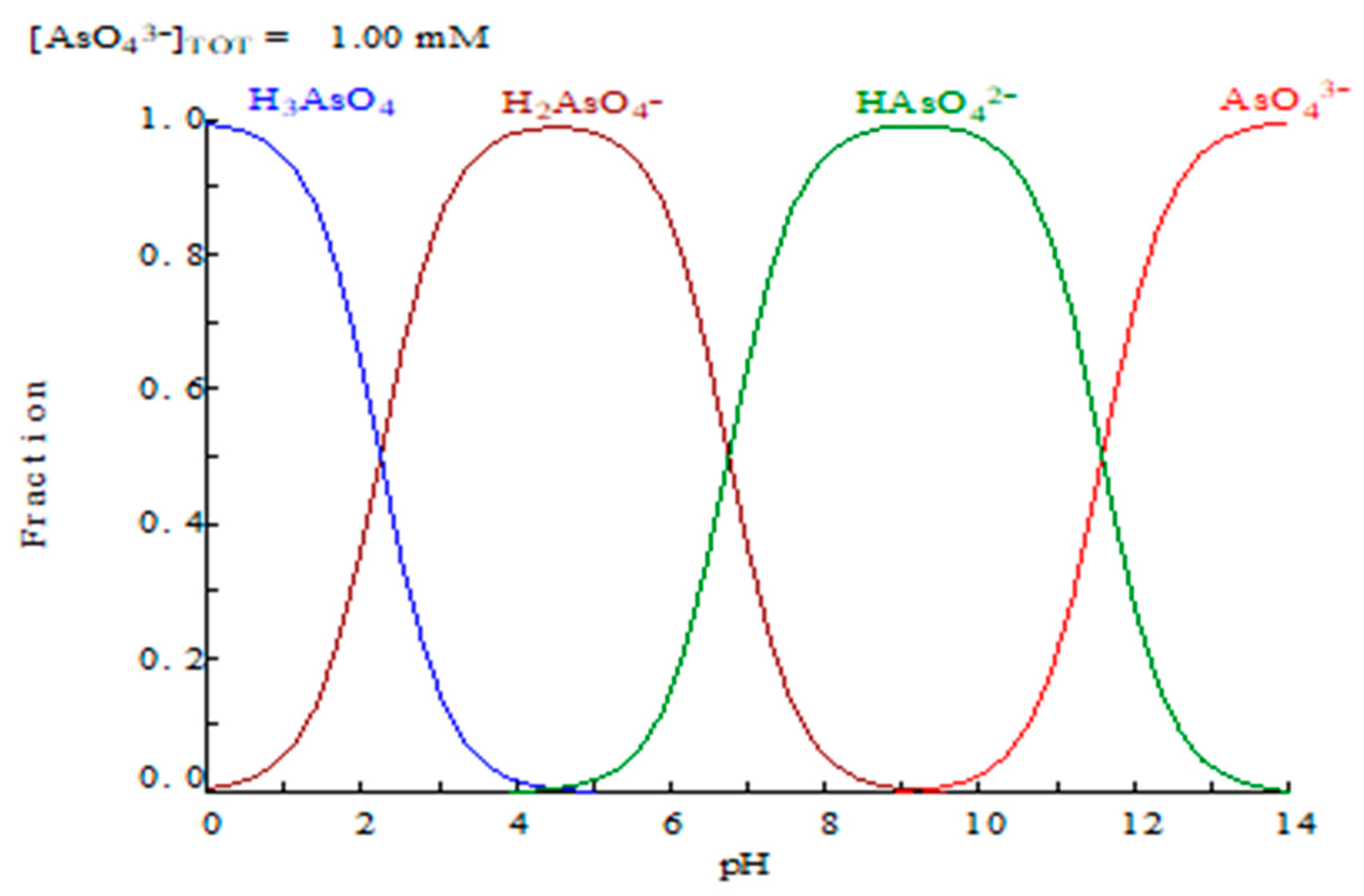

At a first instance, the extraction of arsenic(V) is expected to be greatly dependent on the As(V) speciation in the aqueous phase

versus the pH of this phase (

Figure 1) [

12]. Thus, being Cyanex 923 a solvation reagent, extracting only neutral species, it is logical to suppose, that the affinity of this reagent towards As(V) will be only in the pH range in which H3AsO4 species is going to be predominant.

2.1.1. Influence of the Equilibration Time

Preliminary tests demonstrated that the extraction of arsenic from acidic medium (pH<2.2) reached equilibrium with five minutes of contact, independently of the extractant concentration in the organic phase or arsenic and sulphuric acid concentrations in the aqueous solution. Sulphuric acid extraction reached equilibrium even at shorter time, it was demonstrate that Cyanex 923 extracted sulphuric acid from aqueous media [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

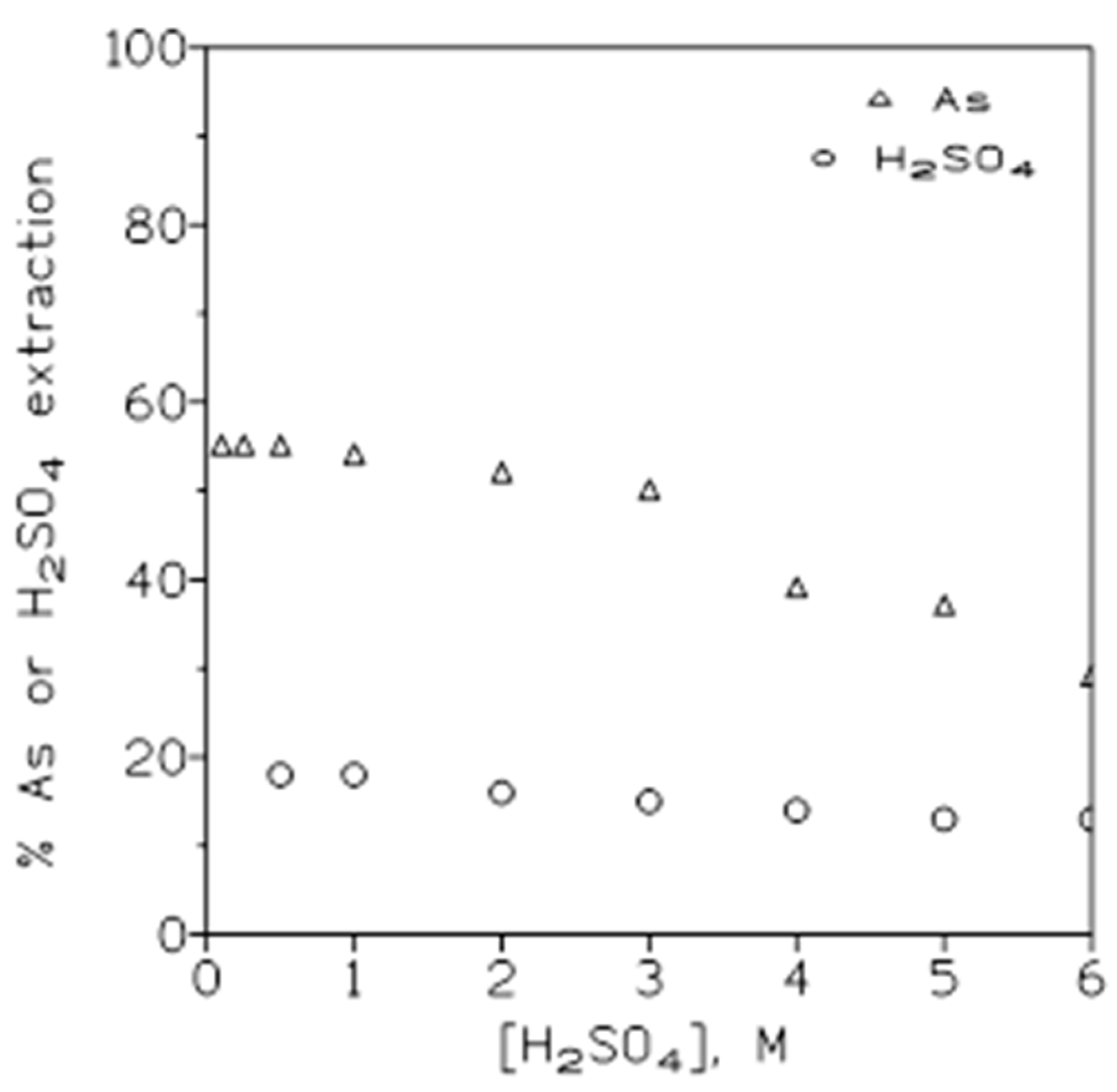

2.1.2. Influence of Acidity of the Aqueous Phase

The variation on arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid extraction with Cyanex 923 at various sulphuric acid concentrations in the aqueous phase was next investigated. In this case, the aqueous phase contained 1.5 g/L As(V) in sulphuric acid medium (0.1-6 M), and the organic phases were of 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100. The results from these experiments were illustrate in

Figure 2, showing that there was a continuous decrease in both arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction as the initial sulphuric acid concentration in the aqueous phase was increased.

Table 1 showed the sulphuric acid to arsenic concentrations (molar scale) in the organic phase relationship at the various initial acid concentration in the aqueous solution, these results showed that this ratio was far to be constant since increased with the increase of the initial acid concentration in the solution. This lack of consistency should be indicative that the extraction of arsenic and sulphuric acid onto the organic phase was independent from one to another.

Other experimental results indicated that from sulphuric acid concentrations below 0.1 M, the percentage of arsenic(V) extraction decreased, probably due to the increase of H

3AsO

4 deprotonation, and formation of the non-extractable H

2AsO

4- species in the aqueous phase (

Figure 1). Thus, Cyanex 923 can not be used to remove arsenic(V) from liquid effluents with a pH value near or greater than 2. Against the above, Cyanex 923 was suitable for its use to remove arsenic(V) from acidic solutions, i.e. copper refineries, though potential sources of arsenic-contaminated acidic solutions were not limited to these specific refineries [

18].

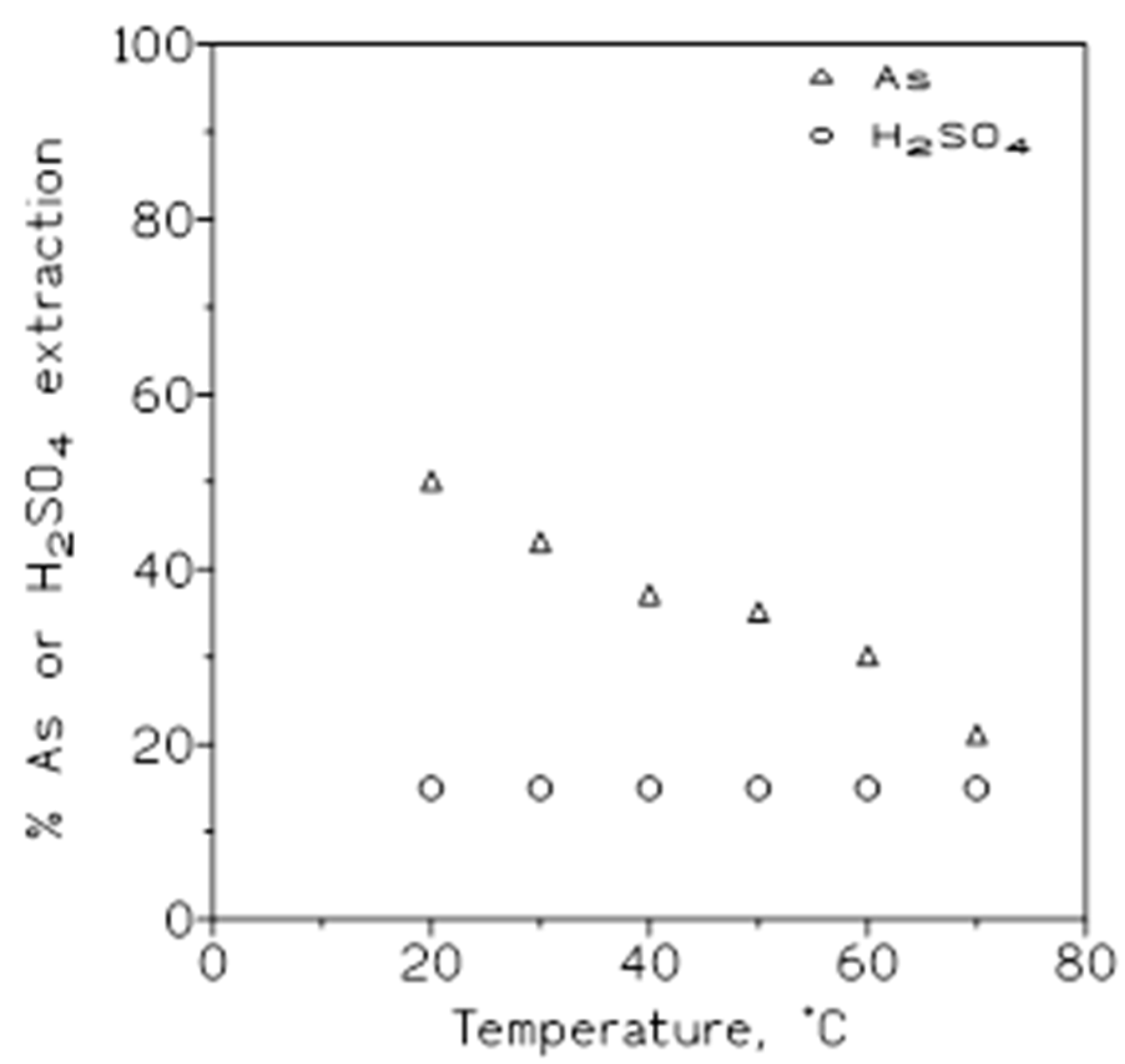

2.1.3. Influence of the Temperature

To establish the influence of the variation of temperature (20-70 ºC) on arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid removal from solutions, a series of extraction experiments were carried out using aqueous phase of 1.5 g/L As(V) in 3 M sulphuric acid medium, and organic phases of 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100. The results from these experiments were shown in

Figure 3, plotting the percentage of arsenic or sulphuric acid extracted onto the organic phase versus temperature. It can be seen, that the percentage of arsenic extraction decreased as the temperature is increased, whereas in the case of sulphuric acid this percentage of extraction remained almost constant.

The Vant Hoff equation established a relationship within the extraction constant (K

ext) and the temperature, however, a series of investigations often used an approximation to the above in which the relation of the temperature is established with the distribution coefficient of the given element [

19,

20,

21,

22], thus:

and by plotting log D

As versus 1/T it is possible estimate the value of the change in enthalpy and enthropy associated with the corresponding system. Moreover, it was described that this expression can be used in systems when the given component exists in the system as more than one species [

23]. In the above equation, D

As (arsenic distribution coefficient) is defined as:

where [As]

org and [As]

aq are the arsenic concentrations in the organic and aqueous phases at equilibrium, respectively, R is the gas constant. The results from this plot (r

2= 0.9644) indicated that arsenic extraction had an exothermic character (ΔHº= -19 kJ/mol), with ΔSº of -65 J/mol·K, indicating an increase of the order in the system as consequence of arsenic loading onto the organic phase.

Since:

and taking into consideration the value of K

ext= 0.80 (see

Table 3), it was found that the extraction process was not spontaneous.

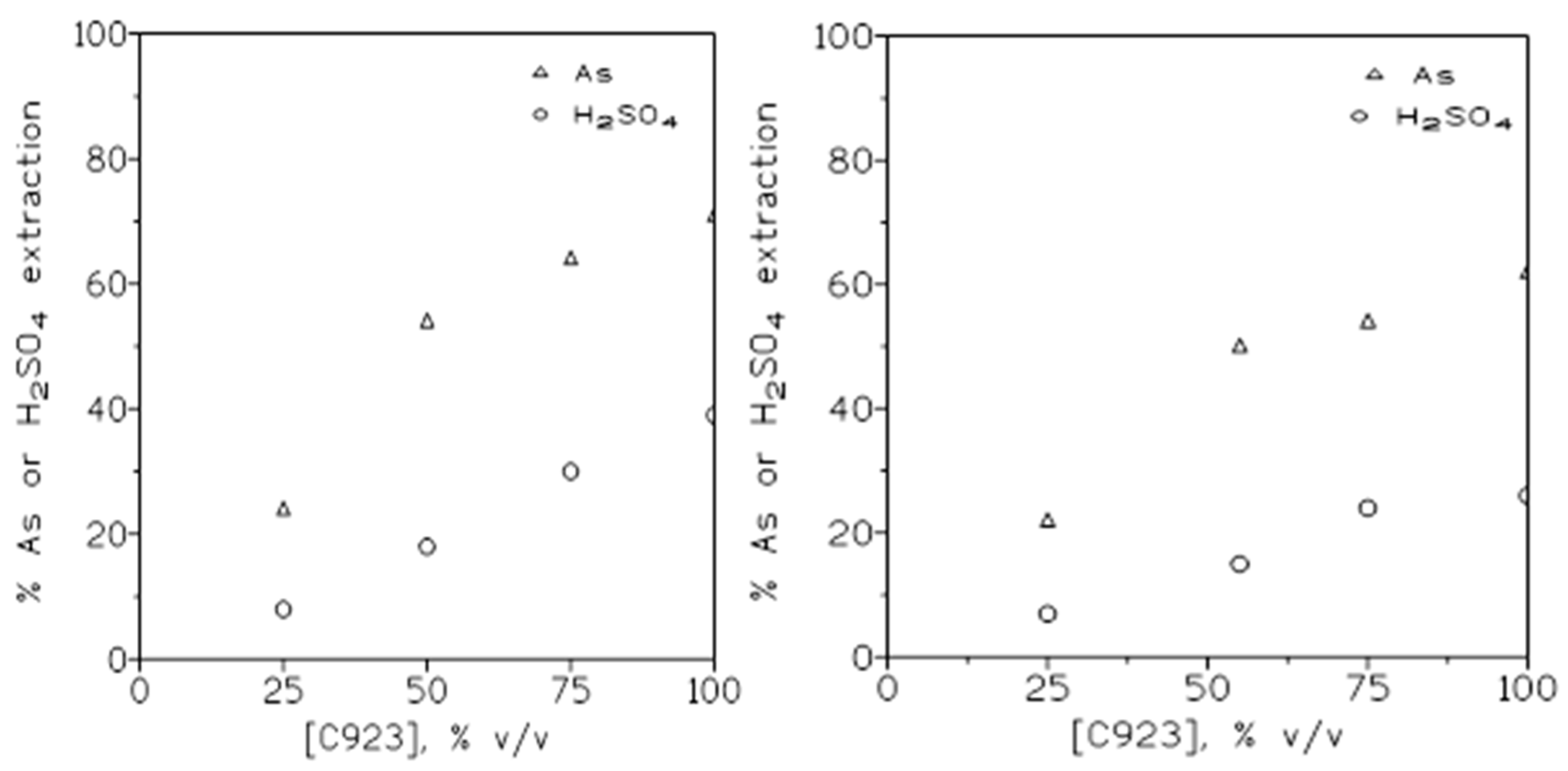

2.1.4. Influence of the Extractant Concentration

The influence of the variation of the extractant concentration on arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid extraction was also investigated. In these experiments aqueous solutions contained 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M H2SO4, whereas the organic phases were of 25-75 %v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100 and undiluted Cyanex 923 (previously saturated with water to avoid changes in the volume of the solutions); the possibility of the practical use of this undiluted extractant is an advantage over others reagents, since allowed to use, if necessary, all of its chemical potential and avoided the use of the organic diluent.

The results from these set of experiments were shown in

Figure 4 (left). These results indicated that the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction increased with the increase of the extractant concentration in the organic phase.

If the aqueous solution contained 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M H

2SO

4, the tendency found (

Figure 4 (right)) was the same than in the above case, however, and as it was expected from results showed in

Figure 2, the percentage of extraction for both arsenic and sulphuric acid was lower than in the case of using the more diluted sulphuric acid solution.

Table 2 summarized the [H

2SO

4]

org/[As]

org molar relationship for the results showed in Fig. 4. The results indicated that, at the various extractant concentrations, there was not a direct relationship between these molar concentrations in the organic phase, thus, again the extraction of both solutes by Cyanex 923 was independent from one to another.

In order to define the species formed in the organic phase and its extraction constants, experimental results were numerically treated by the use of a tailored computer program which minimizes the U function defined as:

where D

exp and D

cal were the experimental distribution coefficients (eq. (2)) and the coefficients calculated by the program, respectively. In these calculations, the extraction of sulphuric acid by Cyanex 923 was also considered [

13], whereas the formation of Cyanex 923 aggregates in the organic phase was not considered [

24], it can be generally stated that the formation of aggregates is more possible in aliphatic diluents rather than in aromatic ones. The results from these calculations were summarized in

Table 3. Accordingly, the extraction of arsenic(V) by Cyanex 923 responded to the formation of two species: H

3AsO

4·L and H

3AsO

4·2L at 1.5 M sulphuric acid, and a single species (H

3AsO

4·L) at 3 M sulphuric acid. Sulphuric acid was extracted by formation of H

2SO

4·L species in the organic phase [

13].

Table 3.

Arsenic(V) species formed in the organic phase and extraction constants.

Table 3.

Arsenic(V) species formed in the organic phase and extraction constants.

| Sulphuric acid, M |

Species |

Kext

|

U |

1.5

3 |

H3AsO4·L

H3AsO4·2L

H3AsO4·L |

0.36

0.67

0.80 |

0.012

0.011 |

2.1.5. Influence of the Initial Arsenic Concentration in the Aqueous Phase

Also the influence of the variation in the arsenic(V) concentration in the aqueous phase on metal extraction was investigated. In this case, the organic solutions were as above, whereas the aqueous phase contained 5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M sulphuric acid. The results of these experiments were shown in

Table 4; the results showed that the variation of the arsenic concentration had very little influence on the percentage of arsenic extraction, whereas the percentage of sulphuric acid extraction remained the same that the values obtained when the aqueous phase was of 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M sulphuric acid.

With respect to the variation of the [H

2SO

4]

org/[As]

org molar concentrations relationship at the various extractant concentrations, results in

Table 5 showed that again there was not a direct relationship between both solutes, and that this ratio was also different than that resulting with extractions carried out with the aqueous phase of 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M sulphuric acid (see

Table 2).

The almost identical percentages of extraction, and thus, in the distribution coefficients values, indicated that in the extraction of arsenic(V) there was not formation of polynuclear complexes in the organic phase, these results were in accordance with the stoichiometries of the arsenic(V)-Cyanex 923 species showed in

Table 3.

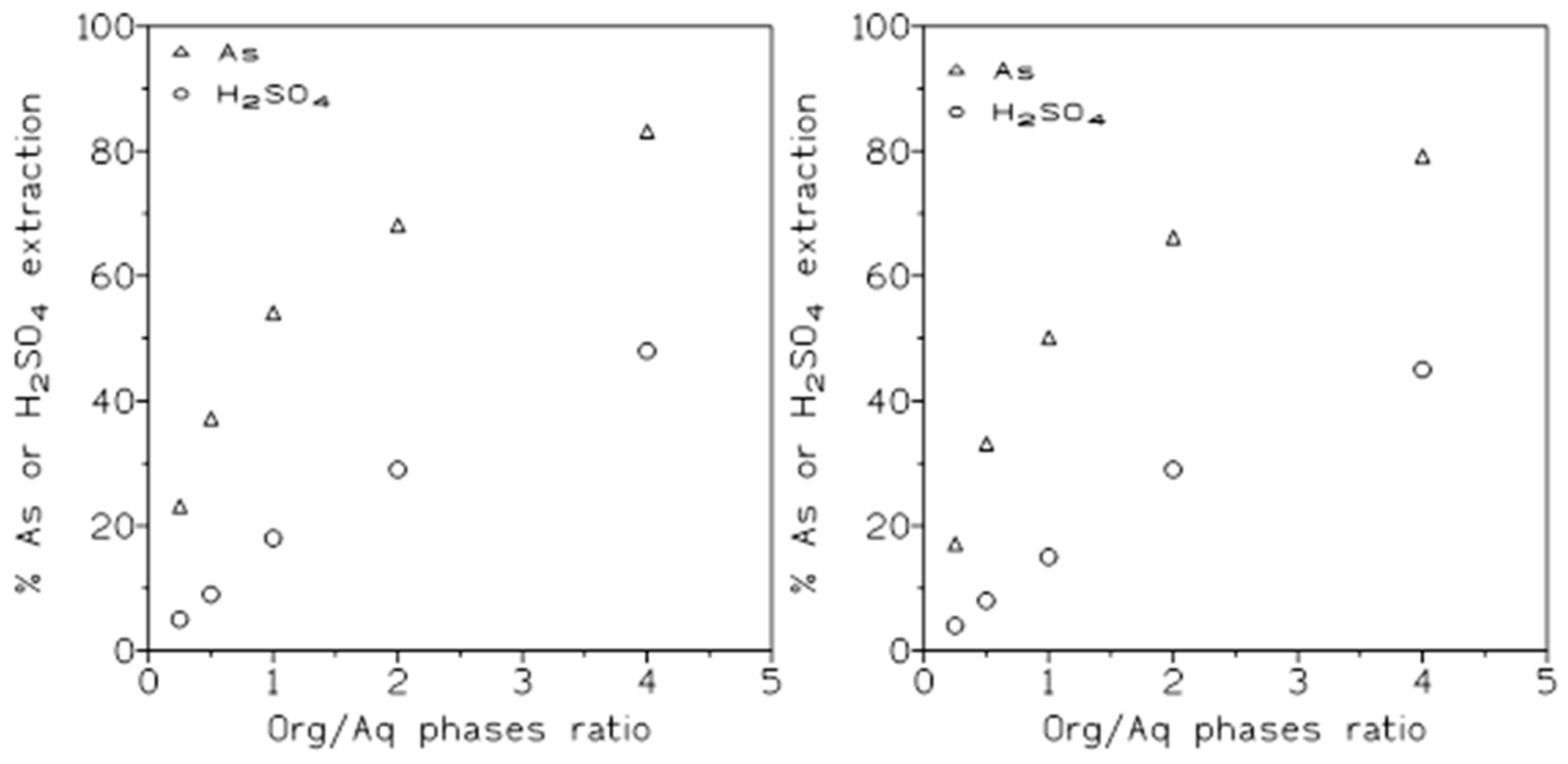

2.1.6. Influence of the O/A Relationship

Next was investigated the influence of the continuous variation of the O/A ratio on arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction by Cyanex 923. In these series of experiments, aqueous solutions, contained 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M H

2SO

4 or 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M H

2SO

4, were contacted with organic phases of 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100 at various (0.5-4) O/A ratios. The results derived from these set of experiments were summarized in

Figure 5 (l.5 M sulphuric acid, left) and (3 M sulphuric acid, right). Both Figures, showed the same pattern of increasing the percentage of solute extraction as the O/A ratio increased, however, and in accordance with previous results (

Figure 2), the percentages of arsenic or sulphuric acid extraction were slightly lower in the case of 3 M sulphuric acid than when the 1.5 M sulphuric acid solution was used in the experiments.

With respect to the separation of arsenic from sulphuric acid,

Table 6 showed the values of the arsenic-sulphuric acid separation factors, defined as:

where D were the corresponding distribution coefficients.

The results presented in this

Table 6 indicated that arsenic can be best separated from the acid at low O/A ratios, though a co-extraction of both solutes was also a possibility, since they can be separated conveniently in the stripping stage (see below).

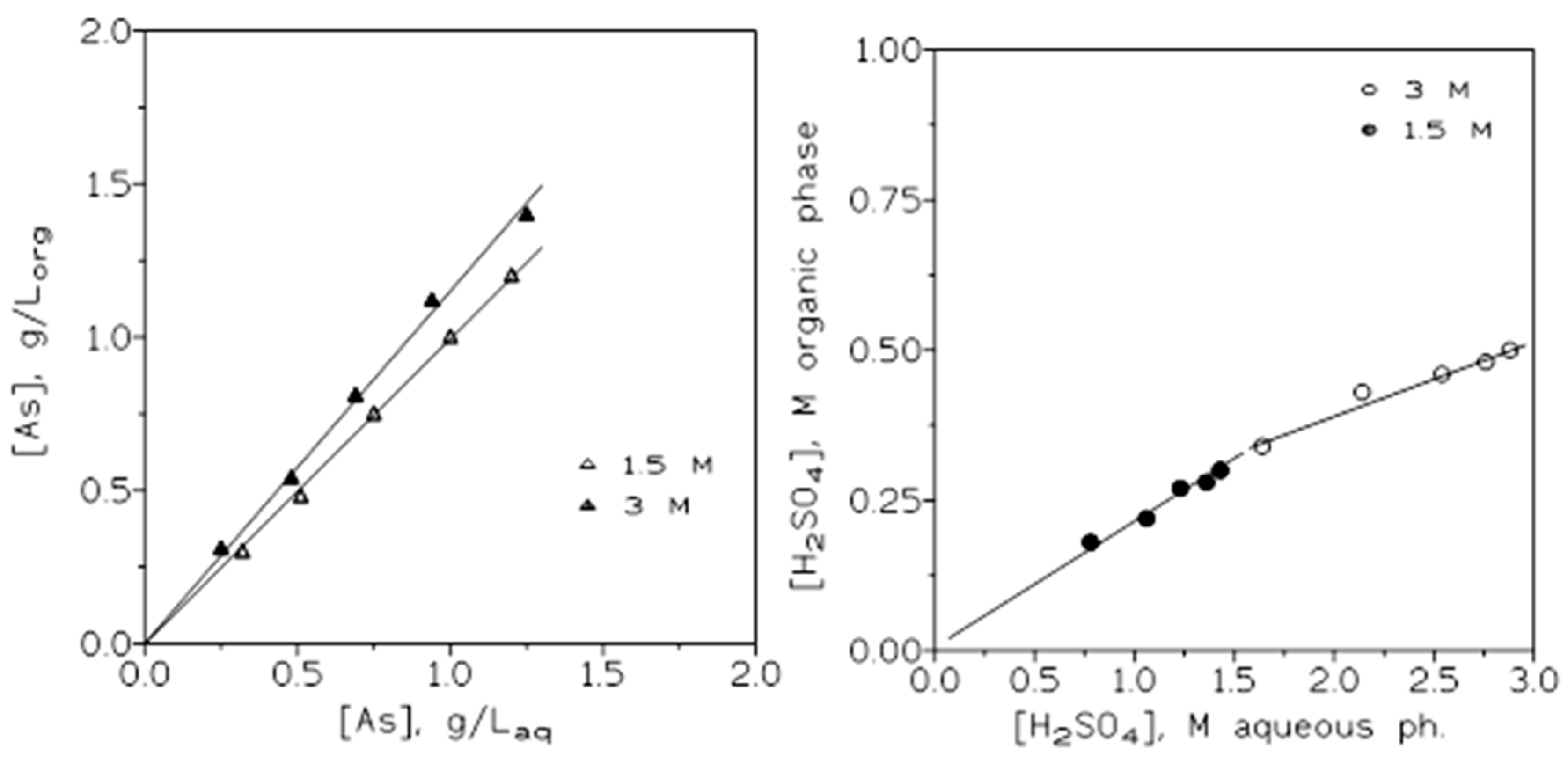

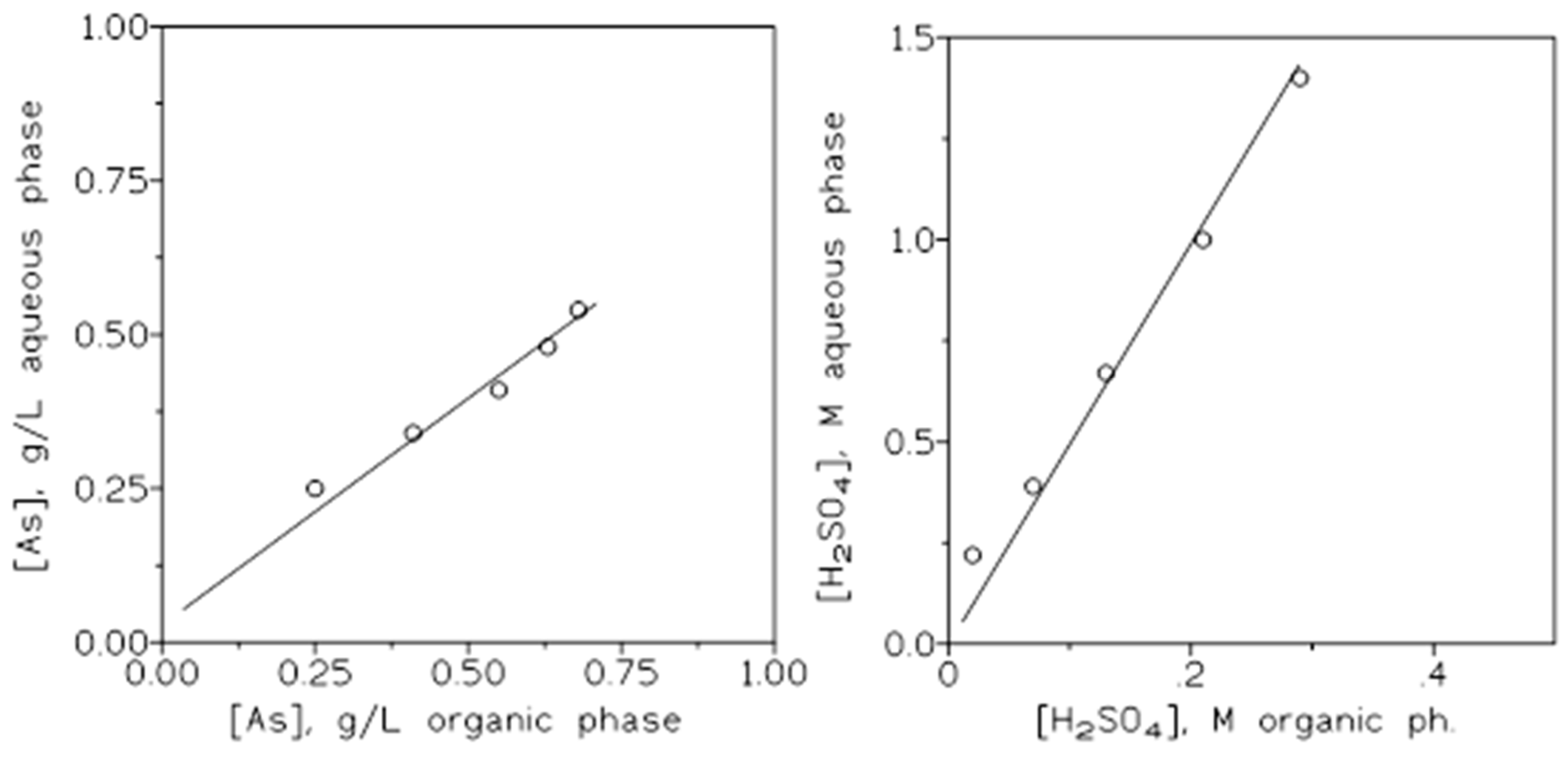

Figure 6 showed the corresponding arsenic (left) and sulphuric acid (right) extraction isotherms for the present system at the two sulphuric acid concentrations investigated in this work.

2.2. Arsenic(V) and Sulphuric Acid Stripping

Previous experiments showed that water was an effective strippant both for arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid, thus, not other chemical was investigated in this stage. Also, previous experimentation showed that in this stage, equilibrium was reached within few minutes of contact between the As/H2SO4-loaded organic phase and the stripping phase.

In the case of arsenic(V) the stripping equilibrium can be represented by the next overall reaction:

this is, in water medium the equilibrium was shifted to the right due to the formation of the non-extractable anionic arsenic species. In the above equation, n= 1 or 2.

In the case of sulphuric acid, and due to the water medium, the corresponding extraction equilibrium, was shifted to the left:

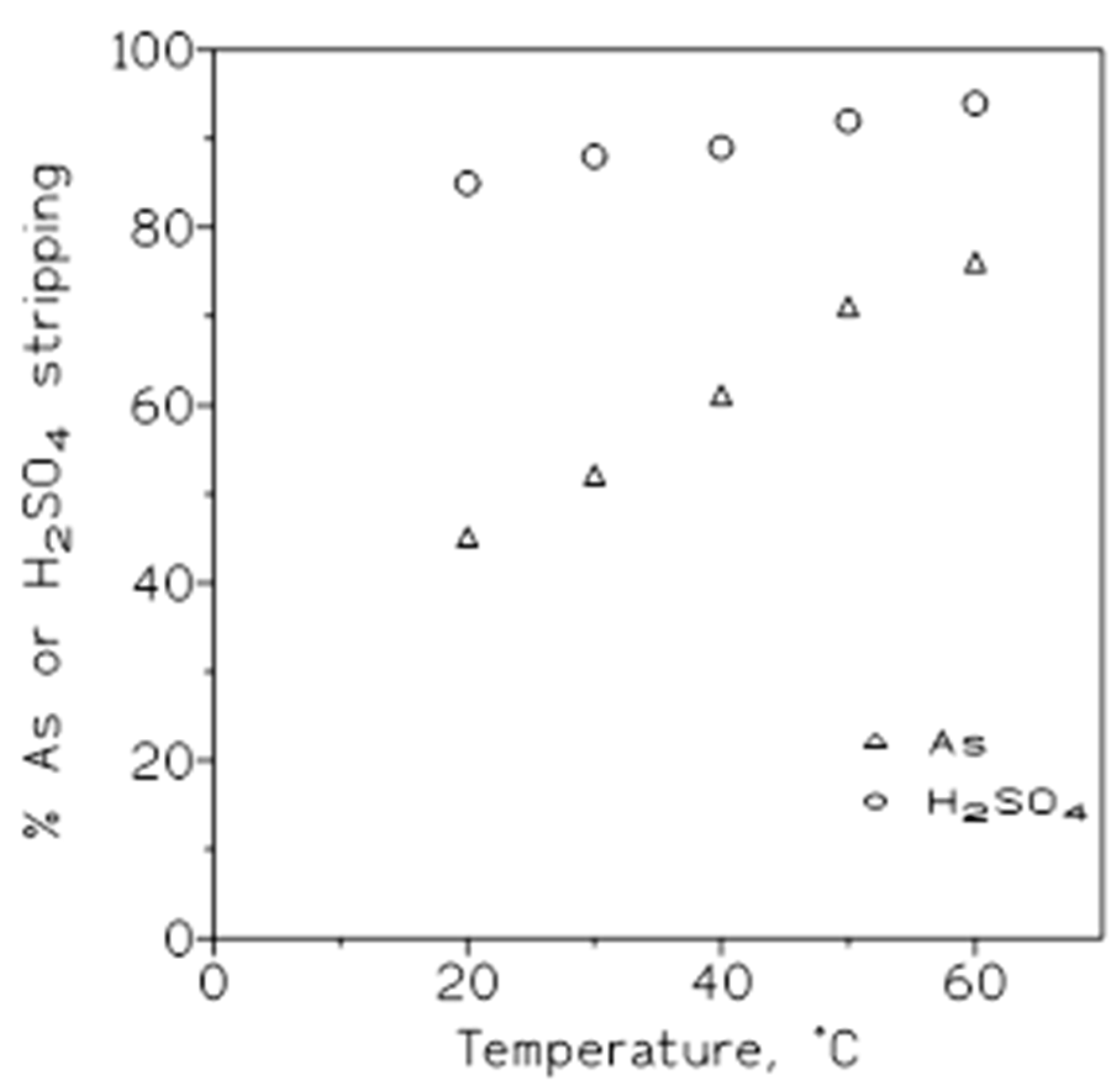

2.2.1. Influence of the Temperature

The influence of this variable, on the stripping of arsenic and sulphuric acid loaded onto the organic phase, was investigated using a 50 % v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100 organic phase loaded with 0.75 g/L As(V) and 0.46 M sulphuric acid. The results from these experiments were shown in

Figure 7, plotting the percentage of arsenic or sulphuric acid stripped versus the temperature; it can be seen that with both solutes, the increase of the temperature produced an increase in the percentage of stripping.

In the stripping stage, it was defined the distribution coefficient as:

thus, if D

st>1 it means that the stripping stage favoured the removal of the solute from the organic phase to the stripping solution.

Table 7 summarized the distribution coefficients for arsenic and sulphuric acid in the stripping operation at various temperatures.

Thus, and in accordance with results represented in

Figure 7, the increase of the temperature was accompanied by an increase of the corresponding distribution coefficient values. In this same

Table 7, the values of the separation factors (β) H

2SO

4/As at each temperature were given. The separation factor was defined as the ratio of the sulphuric acid to arsenic distribution coefficients:

where D values were defined as in eq.(8). If β>1, the separation of sulphuric acid from arsenic was favoured. Thus, from the results showed in

Table 7, at a first instance, 20 ºC seemed to be the most favoured temperature to accomplish this separation since the value of β was the greatest.

Using the same thermodynamic expressions than in the extraction stage, it was concluded that, in the case of arsenic, the stripping stage had an endothermic character (ΔHº= 28 kJ/mol), with ΔSº of 94 J/mol·K, indicating an increase of the randomness in the system. With respect to the stripping of sulphuric acid, the process was also endothermic (ΔHº= 19 kJ/mol), with ΔSº of 78 J/mol·K, indicative of an increase of the system randomness.

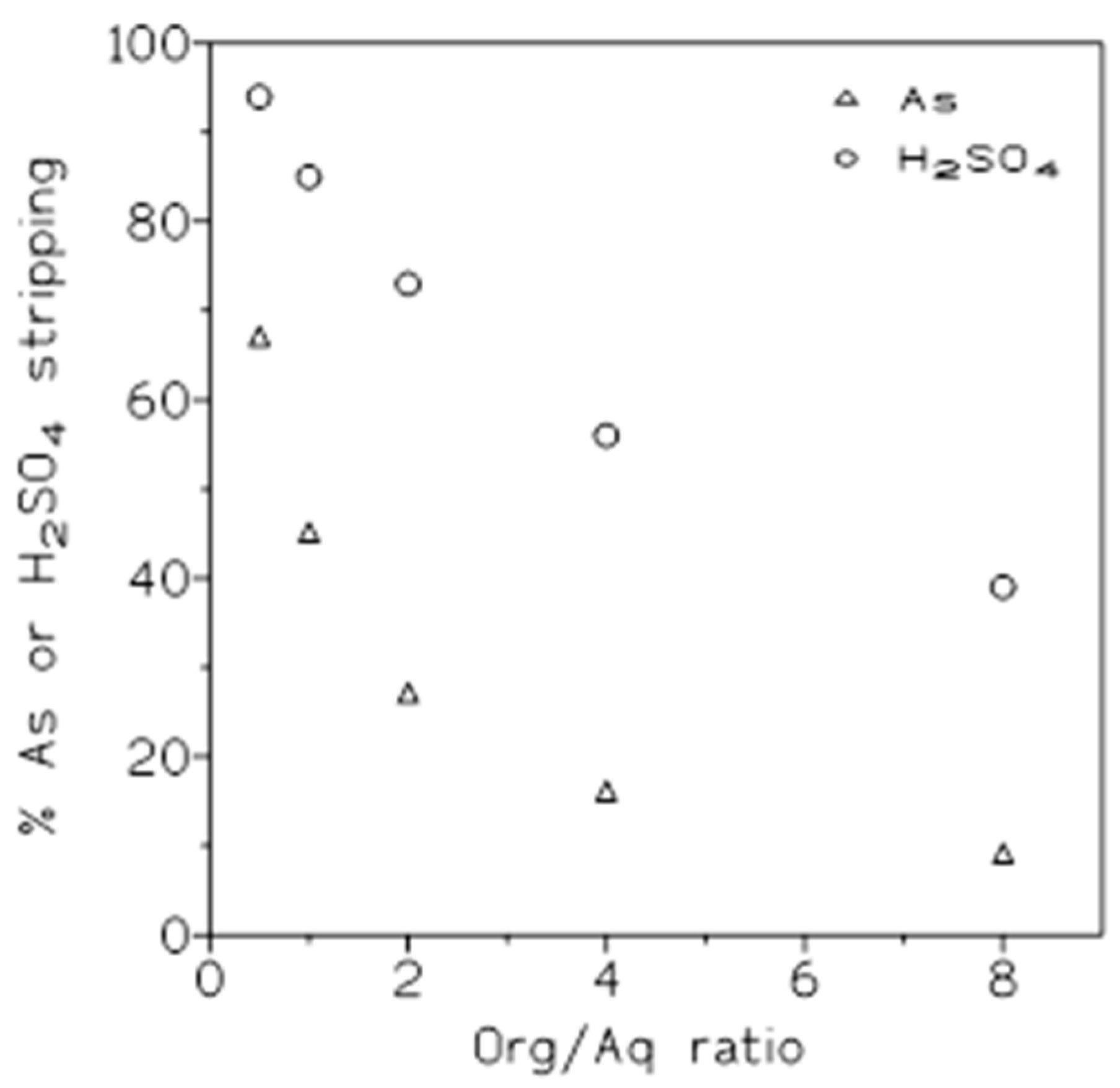

2.2.2. Influence of the O/A Relationship

Several experiments were carried out, with the same organic and stripping phases than above, to investigate the influence of the O/A ratio on the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid stripping. The results from these experiments were shown in

Figure 8, it was shown that the

Similarly to above,

Table 8 summarized the distribution coefficients and the separation factors values at these various O/A ratios. These results showed that in both cases, the distribution coefficient value decreased with the increase of the O/A ratio; with respect to the separation factor values, the greatest value was obtained when an O/A ratio of 0.5 was applied, thus, sulphuric acid was best separated from arsenic using this ratio, and after, arsenic was stripped from the organic phase using greater O/A ratios.

Lastly,

Figure 9 showed the corresponding stripping isotherms.

2.3. Selectivity of the System

It was previously mentioned that Cyanex 923 can not be used to remove arsenic(V) from aqueous solutions with pH values near or greater than 2, instead this extractant can be effectively used to remove this harmful element from acidic solutions, and one clear situation of potential use is in the removal of arsenic(V) from spent copper electrorefining solutions. Thus, in the present work organic phases of 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100 were put into contact with aqueous solutions containing Cu(II), Bi(III), Sb(III) and Ni(II), being these elements representative of metals presented in these electrorefining solutions.

Table 9 summarized the results derived from these set of experiments, it can be seen that only Sb(III) was appreciably extracted by Cyanex 923, being the percentage of extraction increased with the increase of the acidity of the aqueous phase. In all the cases, the extraction of sulphuric acid was near constant, suggesting again that the extractions of this mineral acid and that of the metal were independent from one to another.

Based in the results derived from this investigation, a possible sequence of steps for the treatment of these copper electrolytes included:

(i) treatment of the copper electrolyte to remove antimony and bismuth. It was proposed several procedures for the removal of these elements [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33],

(ii) coextraction of arsenic and sulphuric acid with Cyanex 923,

(iii) stripping of sulphuric acid with water, with the possibility of reuse of the acidic solution,

(iv) stripping of arsenic with water, Cyanex 923 recycled to another extraction step,

(v) precipitation of arsenic in the form of a salt to be safely dumped, preferably in a crystalline form such as scorodite [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

2.4. Comparison with Other Solvation Extractants

In order to compare the performance of Cyanex 923 against other solvation reagents containing the P=O donor group, several experiments were carried out using Cyanex 923 (phosphine oxide), dibutyl butylphosphonate (DBBP, phosphonic ester) and tri-butyl phosphate (TBP, phosphoric ester), all were used in the undiluted form, thus, a previous presaturation step with water was accomplished in all the cases, and these organic phases were put into contact with an aqueous solution containing 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M H2SO4.

The results from these experiments (

Table 10) indicated that with Cyanex 923 the highest percentages of extraction, both for arsenic and sulphuric acid), were reached, and a general extraction tendency was derived as Cyanex 923>DBBP>TBP, sequence which was attributable to the greater electron-donor capacity of Cyanex 923 (R

3PO) respect to DBBP (R´(RO)

2PO) and TBP ((RO)

3PO), representing R various alkyl chains.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Cyanex 923 was used as received from the vendor (Cytec Ind, now Solvay), its composition was given elsewhere [

39], and being described as composed by four tryalkyl phosphine oxides, but normally considered as one extractant composed by the average of the fourth reagents. Diluent Solvesso 100 (aromatic) was obtained from Exxon Chem. Iberia, and also was used as received by the manufacturer, All other chemicals were of AR grade.

3.2. Solvent Extraction Procedure

Liquid-liquid extraction experiments were carried out in thermostatted separatory funnels (100 mL) provided of mechanical shaking via four blades glass impellers. In these funnels, aqueous and organic solutions, at 1:1 volume ratio (unless otherwise stated) were mixed. After phase disengagement, arsenic was analysed in the aqueous solution by ICP-OES (Agilent Technologies 5100), whereas sulphuric acid loaded onto the organic phase was analysed by direct titration of the corresponding phase with standard NaOH solutions, in ethanol medium, using bromothymol blue as indicator. Others concentrations were estimated by the mass balance.

4. Conclusions

The extraction of arsenic(V) by Cyanex 923 extractant was investigated. The results showed that optimal arsenic recovery was around 0.5-2 M sulphuric acid, and that the extraction of arsenic was accompanied by the extraction of sulphuric acid, though it was demonstrated along the investigation that both extraction processes were independent from one to another. The ability of Cyanex 923 to extract arsenic(V) from aqueous solutions decreased at pH values of 2 or greater than 2, thus its practical use it was not possible to extract arsenic(V) from slightly acidic or neutral As(V)-contaminated waters. The increase of temperature (20-70 ºC) affected negatively the percentage of arsenic loaded onto the organic phase, which demonstrated the exothermic character of the extraction process. Arsenic(V) was extracted onto the Cyanex 923 organic phase by formation of H3AsO4·nL (n= 1or 2) from 1.5 M sulphuric acid solutions, and H3AsO4·L from 3 M sulphuric acid medium. Sulphuric acid was extracted by formation of H2SO4·L species in the organic phase. Extraction isotherms were provided from the experimental study.

Both arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid can be stripped from loaded organic phases by the use of water as strippant, and stripping isotherms were also derived from the experimental study. Based in the above results, the separation of sulphuric acid from arsenic was better accomplished in the strip operation, first, sulphuric acid was stripped at low O/A ratios and secondly, arsenic can be recovered from the As-loaded organic phase.

Experimental results showed that from a series of metals, only antimony(III) was extracted by Cyanex 923 from acidic solutions, increasing the extraction with the increase of the sulphuric acid concentration in the aqueous feed solution, though this extraction was also lower than that of arsenic(V).

Cyanex 923 was a stronger extractant with respect to arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid than other solvation reagents, such as dibutyl butylphosphonate and tri-butylphosphate, being the above attributable to the higher electron-donor capacity of Cyanex 923 in comparison with that of dibutyl butylphosphonate and tributylphosphate.

A sequence of steps for the treatment of an acidic copper electrolyte was proposed.

Author Contributions

F.J.Alguacil: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft. J.I.Robla: Investigation, Funding. E.Escudero: Investigation, Analytical work. Writing-original draft.

Acknowledgements

To the CSIC (Spain) by support via Project 202250E019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have not known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Emsley, J. The Elements of Murder, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005.

- Hackethal, C.; Pabel, U.; Jung, C.; Schwerdtle, T.; Lindtner, O. Chronic dietary exposure to total arsenic, inorganic arsenic and water-soluble organic arsenic species based on results of the first German total diet study. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2023, 859, 160261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro De Oliveira, E.C; Siqueira Caixeta, E.; Santana Vieira Santos, V.; Barbosa Pereira, B. Arsenic exposure from groundwater: environmental contamination, human health effects, and sustainable solutions. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part B. 2021, 24, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, D.; Ganesan, N.; Boffetta, P.; Labgaa, I. Arsenic-contaminated drinking water and cholangiocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 32, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glade, S.; Bandaru, S.R.S.; Nahata, M.; Majmudar, J.; Gadgil, A. Adapting a drinking water treatment technology for arsenic removal to the context of a small, low-income California community. Water Res. 2021, 204, 117595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayub, A.; Srithilat, K.; Fatima, I.; Panduro-Tenazoa, N.M.; Ahmed, I.; Akhtar, M.U.; Shabbir, W.; Ahmad, K.; Muhammad, A. Arsenic in drinking water: overview of removal strategies and role of chitosan biosorbent for its remediation. Environ, Sci. Poll. Res. 2022, 29, 64312–64344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Chauhan, S.; Varjani, S.; Pandey, A.; Bhargava, P. C. Integrated approaches to mitigate threats from emerging potentially toxic elements: A way forward for sustainable environmental management. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somayaji, A.; Sarkar, S.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Raval, R. Synthetic biology techniques to tackle heavy metal pollution and poisoning. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alguacil, F.J.; Escudero, E. The removal of toxic metals from liquid effluents by ion exchange resins. Part XVII: arsenic(V))/H+/Dowex 1x8. Rev. Metal. 2022, 58, e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, N.; Luo, D.; Hadj, Y.M.; Lopez, J.; Fernández de Labastida, M.; Sastre, A.M.; Valderrama, C.A.; Cortina, J.L. Increasing the circularity of the copper metallurgical industry: Recovery of Sb(III) and Bi(III) from hydrochloric solutions by integration of solvating organophosphorous extractants and selective precipitation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, A.; Qi, X.; Yan, G.; Zhi, G. Arsenic removal from aqueous solution by chitosan loaded with Al/Ti elements. Ser. Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 2298–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigdomenech, I. Chemical equilibrium software Hydra/Medusa. 2023. https://sites.google.com/site/chemdiagr/home.

- Alguacil, F.J.; Lopez, F.A. The extraction of mineral acids by the phosphine oxide Cyanex 923. Hydrometallurgy 1996, 42, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacki, M.B.; Wiśniewski, M.; Szymanowski, J. Effect of extractant on arsenic(V) recovery from sulfuric acid solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1998, 228, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberhan, L.; Wisniewski, M. Removal of arsenic(III) and arsenic(V) from sulfuric acid solution by liquid-liquid extraction. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2003, 78, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, M. Extraction of arsenic from sulphuric acid solutions by Cyanex 923. Hydrometallurgy 1997, 46, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, M. Removal of arsenic from sulphuric acid solutions. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 1998, 228, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, N.; Virolainen, S.; Latostenmaa, P.; Salminen, J.; Haapalainen, M.; Sainio, T. Removal and recovery of arsenic from concentrated sulfuric acid by solvent extraction. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 187, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Wakil, A.F.; Zaki, S.A.; Ismaiel, D.A.; Salem, H.M.; Orabi, A.H. Extraction and separation of gallium by solvent extraction with 5-nonyl-2-hydroxyacetophenone oxime: Fundamentals and a case study. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 216, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusty, S.; Pradhan, S.; Mishra, S. Extraction and separation studies of Nd/Fe and Sm/Co by deep eutectic solvent containing Aliquat 336 and glicerol. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadbad, M.R.A.; Zaheri, P.; Abolghasemi, H.; Fazel Zahakifar, F. The performance evaluation of Alamine336 in solvent extraction and polymer inclusion membrane methods for valuable ions extraction: A case study of Te(IV) separation intensification. Chem. Eng. Proc. 2023, 184, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sang, Z.; Li, Q.; Gong, J.; Shi, R.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, X. Palladium(II) extraction from acidic chloride media using an ionic liquid-based aqueous two-phase system (IL-ATPS) in the presence of dipotassium hydrogen phosphate salting-out agent and reductive stripping with hydrazine hydrate to recover palladium metal. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 216, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distler, P.; Stamberg, K.; John, J.; Harwood, L.M.; Lewis, F.W. Thermodynamic parameters of Am(III), Cm(III) and Eu(III) extraction by CyMe4-BTPhen in cyclohexanone from HNO3 solutions. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 141, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Liao, W. Physicochemical properties, surface active species and formation of reverse micelles in the Cyanex 923-n-heptane/cerium(IV)-H2SO4 extraction system. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisinger, D.B.; Scholey, B.J.Y. Ion exchange removal of antimony and bismuth from copper refinery electrolytes, in: Proceedings of the Copper 95 International Conference, Santiago (Chile), pp. 26–29, 1995.

- Navarro, P.; Simpson, J.; Alguacil, F. J. Removal of antimony (III) from copper in sulphuric acid solutions by solvent extraction with LIX 1104SM. Hydrometallurgy 1999, 53, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, P.; Alguacil, F.J. Adsorption of antimony and arsenic from a copperelectrorefining solution onto activated carbon. Hydrometallurgy 2002, 66, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, S.; Chen, T.T.; Dutrizac, J.E. Behaviour of antimony and bismuth in copper electrorefining circuits, Can. Metall. Q. 2008, 47, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Yin, Z.; Wang, M.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, F. Homogeneous precipitation of As, Sb and Bi impurities in copper electrolyte during electrorefining. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 105, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Torralvo, F.; Rodríguez-Almansa, A.; Ruiz, I.; Gonzalez, A.I.; Ríos, G.; Ferńandez-Pereira, C.; Vilches-Arenas, L.F. Optimizing operating conditions in an ion-exchange column treatment applied to the removal of Sb and Bi impurities from an electrolyte of a copper electro-refining plant. Hydrometallurgy 2027, 171, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artzer, A.; Moats, M.; Bender, J. Removal of antimony and bismuth from copper electrorefining electrolyte: Part II—An investigation of two proprietary solvent extraction extractants. JOM 2018, 70, 2856–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez de las Torres, A.I.; Moats, M.S.; Ríos, G.; Rodríguez Almansa, A.D.; Śanchez-Rodas, D. Removal of Sb impurities in copper electrolyte and evaluation of As and Fe species in an electrorefining plant. Metals 2021, 11, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez de las Torres, A.I.; Ríos, G.; Rodriguez Almansa, A.; Sánchez-Rodas, D.; Moats, M.S. . Solubility of bismuth, antimony and arsenic in synthetic and industrial copper electrorefining electrolyte. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 208, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monhemius, A.J.; Swash, P.M. Removing and stabilizing As from copper refining circuits by hydrothermal processing. JOM 1999, 51, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, P.; Vargas, C.; Araya, E.; Martín, I.; Alguacil, F.J. Arsenic precipitation from metallurgical effluents. Rev. Metal. 2004, 40, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, R.J.; Feldmann, T.; Daenzer, R.; Demopoulos, G.P. Continuous circuit coprecipitation of arsenic(V) with ferric iron by lime neutralization: The effect of circuit staging, co-ions and equilibration pH on long-term arsenic retention. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 151, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfelt, C.; Feldmann, T.; Roy, R.; Demopoulos, G.P. Stability of arsenate-bearing Fe(III)/Al(III) co-precipitates in the presence of sulfide as reducing agent under anoxic conditions. Chemosphere 2026, 151, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanova, V.; Stefanov, E.; Planska, B.; Dimitrova, R.; Valtcheva, I.; Kadiyski, M.; Stoyanova, V. Arsenic removal in a stable form from industrial wastewater in the copper industry. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2022, 57, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Dziwinski, E.; Szymanowski, J. Composition of CYANEX 923, CYANEX 925, CYANEX 921 and TOPO. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 1998, 16, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of arsenic(V) species versus pH (Puigdomenech, 2001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of arsenic(V) species versus pH (Puigdomenech, 2001).

Figure 2.

Variation in the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various acid concentrations in the aqueous phase. Equilibration time: 5 min. Temperature: 20º C. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 2.

Variation in the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various acid concentrations in the aqueous phase. Equilibration time: 5 min. Temperature: 20º C. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 3.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid concentrations at various temperatures. Aqueous phase: 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M H2SO4. Organic phase: 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100. Equilibration time: 5 min. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 3.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid concentrations at various temperatures. Aqueous phase: 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M H2SO4. Organic phase: 50% v/v Cyanex 923 in Solvesso 100. Equilibration time: 5 min. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 4.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various Cyanex 923 concentrations in the organic phase. Fig. 4 (left): 1.5 g/L As(V) in 1.5 M sulphuric acid. Fig. 4 (right): 1.5 g/L As(V) in 3 M sulphuric acid. Equilibration time: 5 min. Temperature: 20º C. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 4.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various Cyanex 923 concentrations in the organic phase. Fig. 4 (left): 1.5 g/L As(V) in 1.5 M sulphuric acid. Fig. 4 (right): 1.5 g/L As(V) in 3 M sulphuric acid. Equilibration time: 5 min. Temperature: 20º C. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 5.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various O/A ratios. Left figure: extractions carried out with 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M sulphuric acid. Right figure: extractions using 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M sulphuric acid. Equilibration time; 5 min. Temperature: 20 ºC.

Figure 5.

Arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at various O/A ratios. Left figure: extractions carried out with 1.5 g/L As(V) and 1.5 M sulphuric acid. Right figure: extractions using 1.5 g/L As(V) and 3 M sulphuric acid. Equilibration time; 5 min. Temperature: 20 ºC.

Figure 6.

Arsenic (left) and sulphuric acid (right) extraction isotherms.

Figure 6.

Arsenic (left) and sulphuric acid (right) extraction isotherms.

Figure 7.

Plot of the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid stripping versus temperature. Stripping phase: water. Equilibration time: 5 min. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 7.

Plot of the percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid stripping versus temperature. Stripping phase: water. Equilibration time: 5 min. O/A ratio: 1.

Figure 8.

Percentages of arsenic and sulphuric acid stripped at various O/A ratios. Organic phase: 50% Cyanex 923 in Solvesso loaded with 0.75 g/L As(V) and 0.46 M sulphuric acid. Stripping phase: water. Temperature: 20 º C. Equilibration time: 5 min.

Figure 8.

Percentages of arsenic and sulphuric acid stripped at various O/A ratios. Organic phase: 50% Cyanex 923 in Solvesso loaded with 0.75 g/L As(V) and 0.46 M sulphuric acid. Stripping phase: water. Temperature: 20 º C. Equilibration time: 5 min.

Figure 9.

Arsenic (left( and sulphuric acid (right) stripping isotherms. Temperature: 20 º C. Equilibration time: 5 min.

Figure 9.

Arsenic (left( and sulphuric acid (right) stripping isotherms. Temperature: 20 º C. Equilibration time: 5 min.

Table 1.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org relationship (molar scale) at various sulphuric acid concentrations in the aqueous phase.

Table 1.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org relationship (molar scale) at various sulphuric acid concentrations in the aqueous phase.

| [H2SO4], M |

[H2SO4]org/[As]org

|

0.5

1

2

3

4

5

6 |

8

16

32

46

75

89

129 |

Table 2.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org molar relationship at the various extractant and sulphuric acid concentrations.

Table 2.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org molar relationship at the various extractant and sulphuric acid concentrations.

| Cyanex 923, % v/v |

1.5 M H2SO4

|

3 M H2SO4

|

25

50

75

100 |

25

25

35

39 |

50

46

65

69 |

Table 4.

Percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at two initial metal concentrations in the aqueous phase.

Table 4.

Percentage of arsenic and sulphuric acid extraction at two initial metal concentrations in the aqueous phase.

| Cyanex 923, % v/v |

Arsenic |

Sulphuric acid |

25

50

75

100 |

28 (24)

52 (54)

64 (64)

69 (71) |

8 (8)

18 (18)

30 (30)

39 (39) |

Table 5.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org molar relationship at the various extractant concentrations.

Table 5.

Variation in the [H2SO4]org/[As]org molar relationship at the various extractant concentrations.

| Cyanex 923, % v/v |

[H2SO4]org/[As]org

|

25

50

75

100 |

6

8

10

13 |

Table 6.

Values of the arsenic-sulphuric acid separation factors at the various O/A ratios.

Table 6.

Values of the arsenic-sulphuric acid separation factors at the various O/A ratios.

| O/A ratio |

1.5 M sulphuric acid |

3 M sulphuric acid |

0.25

0.5

1

2

4 |

5.74

5.78

5.32

5.46

5.39 |

5.55

5.55

5.55

4.70

4.48 |

Table 7.

Variation of DAs and DH2SO4 with the temperature and the separation factors.

Table 7.

Variation of DAs and DH2SO4 with the temperature and the separation factors.

| Temperature, ºC |

DAs

|

DH2SO4

|

βH2SO4/As

|

20

30

40

50

60 |

0.83

1.08

1.59

2.40

3.17 |

5.57

6.70

8.20

10.5

14.3 |

6.7

6.2

5.2

4.4

4.5 |

Table 8.

Values of the distribution coefficients and separation factors at various O/A ratios.

Table 8.

Values of the distribution coefficients and separation factors at various O/A ratios.

| O/A ratio |

DAs

|

DH2SO4

|

βH2SO4/As

|

0.5

1

2

4

8 |

1

0.83

0.75

0.76

0.79 |

11

5.6

5.3

4.8

4.8 |

11

6.7

7.1

6.3

6.1 |

Table 9.

Using Cyanex 923 to extract different metals.

Table 9.

Using Cyanex 923 to extract different metals.

| Element |

Concentration, g/L |

H2SO4, M |

% extraction |

% H2SO4 extraction |

Cu(II)

Cu(II)

Bi(III)

Bi(III)

Sb(III)

Sb(III)

Ni(II)

Ni(II)

As(V)

As(V) |

0.1

10

0.1

1

0.07

0.07

7

7

1.5

1.5 |

3

1.5

3

1.5

3

1.5

3

1.5

3

1.5 |

2

5

nil

nil

25

26

nil

nil

50

54 |

16

18

16

18

16

17

16

17

15

18 |

Table 10.

Arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid extraction using various solvation extractants.

Table 10.

Arsenic(V) and sulphuric acid extraction using various solvation extractants.

| Extractant |

O/A ratio |

% As extraction |

% H2SO4 extraction |

TBP

DBBP

Cyanex 923 |

1

2

1

2

1

2 |

18

26

46

54

73

88 |

2

4

10

14

39

50 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).