1. Introduction

Antimonite (Sb

2S

3) is the principal industrial mineral of antimony, and often, in one way or another, is connected with gold. Depending on the gold and antimony content, ores can be classified by groups [

1]. The choice of technology is considered depending on the predominance of the valuable compounds (gold or antimony) in the ore or the concentrate. For sulphide- antimony ores and concentrates with a low arsenic content (up to 1%) and gold, pyrometallurgical technologies are mainly used [

2]. Choosing and justifying pyrometallurgical technology, in the first instance, depends on antimony content in the source concentrate. Gold is a side product at the antimony refining [

3,

4].

For gold containing ores, even small concentrations of antimony, influence the process of gold cyanidation negatively. Antimonite is oxidized to compounds such as antimonites (HSbO

32-), antimonates (HSbO

42-), thioantimonates (SbS

3) and others, this affects the targets negatively: a low gold extraction in solution increased cyanide and lime consumption [

5,

6]. Thus, preliminary preparation of raw materials is required.

At the present time the proportion of gold antimony complex ores is increasing and economically justified. The use of traditional technologies of antimony and gold extraction can provoke big losses of the second valuable component, and high operating costs. Such complex ores are processed first to remove antimony materials followed by the gold extraction [

7,

8]. However, gold -antimony ores are often characterized by refractoriness: association of gold with sulphides – antimonite (Sb

2S

3), pyrite (FeS

2) and arsenopyrite (FeAsS). Thin gold inclusion in rock-forming minerals is the most common cause of hardness of such ores; and a significant arsenic, antimony and iron compounds content increases the operating costs on its extraction because of the additional preliminary preparation for cyanidation of the concentrate [

9]. It limits the use of the existing methods of gold-antimony materials processing [

10] and leads to the fact that these concentrates are stacked on the special podiums or sold to the countries where their recycling is possible because of the low environmental requirements.

The existing acidic methods have a number of disadvantages: low extraction of antimony into solution and the formation of elemental sulphur which influences the consequent gold cyanidation negatively [

11].

It is worth noting that the alkaline method is promising, for it is highly selective and possesses the ability to process complex raw materials, what makes it possible to achieve a high antimony extraction to solution, and with no environmental impact. In the meantime, the known results cannot be used for processing of refractory gold – containing raw materials where gold is closely related to sulphide minerals. For sulphide matrix recovery, in practice the following technologies are used; oxidative roasting, ultra -fine grinding, autoclave oxidation (AOX), bioleaching (BIOX), nitric acid oxidation, and others. [

12,

13].

The use of the existing pyrometallurgical technologies is limited because of high toxicity of the volatile arsenic compounds; it requires additional dust and gas cleaning systems costs. For its part, it increases the capital commitments of the production [

14,

15,

16].

The use of the hydrometallurgical methods [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] allows poor raw materials to be recycled to eliminate disposal problems of toxic elements, and also a high loss of the valuable components with exhaust gases [

25,

26,

27]. The use of AOX [

28,

29] and BIOX [

30,

31] methods have been found in Russia; however, due to many limiting factors, such as the complexity of the oxidation process and capital intensity, the introduction of these processes at gold mining companies remains limited. Besides, these methods are not applicable to the materials with a high antimony content; hence the search for alternative technologies are necessary.

The technology of nitrous oxide leaching [

32,

33,

34,

35] is a developing alternative to the existing technologies. The sulphide material is treated with a solution with nitric or/and nitrogen oxides [NSC] [

36,

37]. The heat generated at the time of the exoteric reaction intensifies the oxidation process [

38].

Considering the above factors, the aim of this study is to develop the combination of hydrometallurgical technologies of gold-antimony concentrates recycling which ensures a high degree of extraction by ecologically matured ways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.1.1. Initial Flotation Concentrate

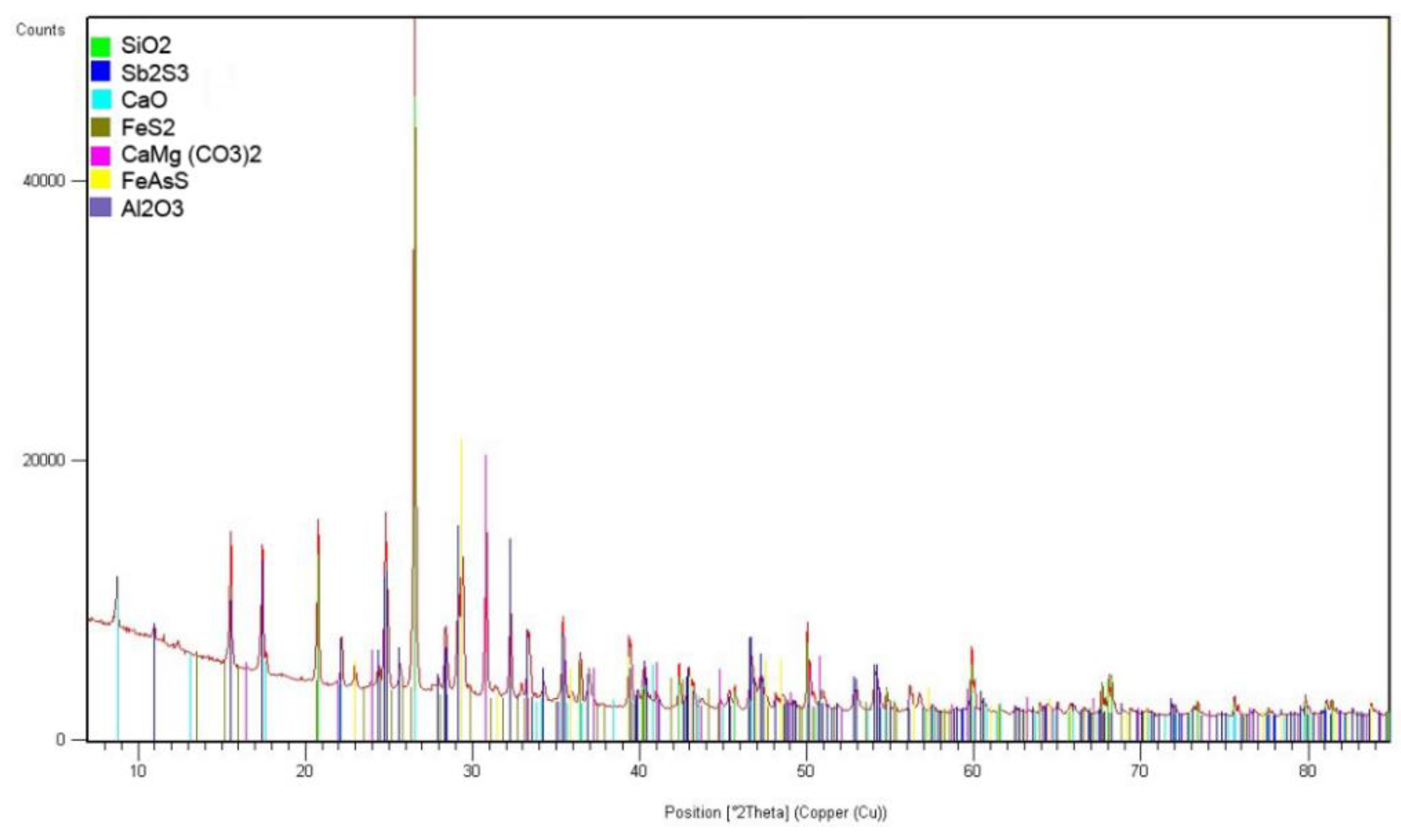

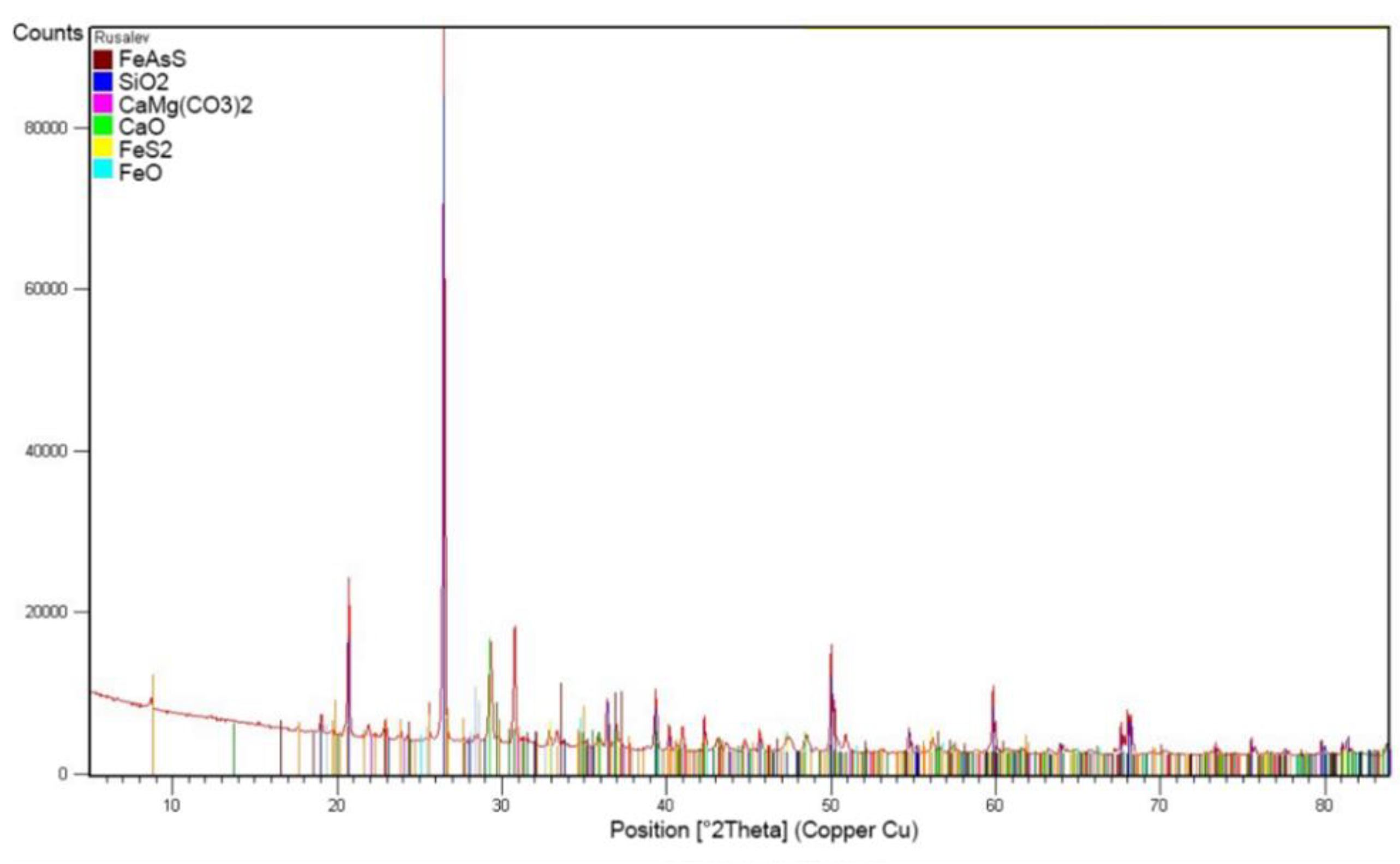

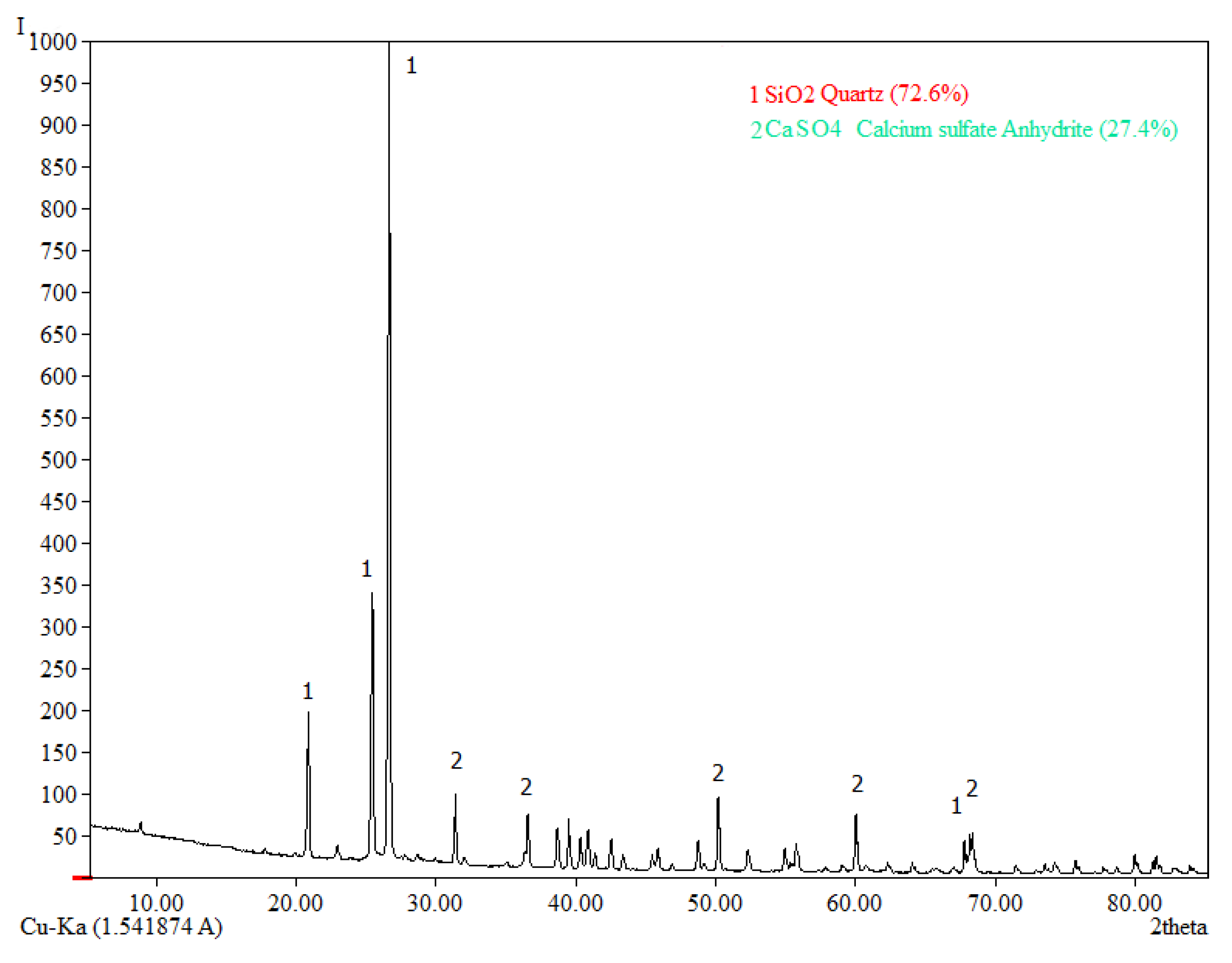

The flotation concentrate of the Olimpiadinskoe deposit was used as the main raw material (Krasnoyarsky Krai, Russia). The concentrate is the quarts antimonite semi-sulphuride rock. The chemical composition of the concentrate is shown in

Table 1, an X-ray of the phase composition is shown in

Figure 1. On the basis of the result, it has been established that quarts (SiO

2) – 33,6 %, antimonite (Sb

2S

3) – 26,7 %, dolomite (CaMg(CO

3)

2) – 5,3 %, calcium oxide (CaO) 15,0%, pyrite (FeS

2) – 5,7%, arsenopyrite (FeAsS) – 4,7%, corundum (Al

2O

3) – 3,1% they are the main minerals of the raw materials to be studied.

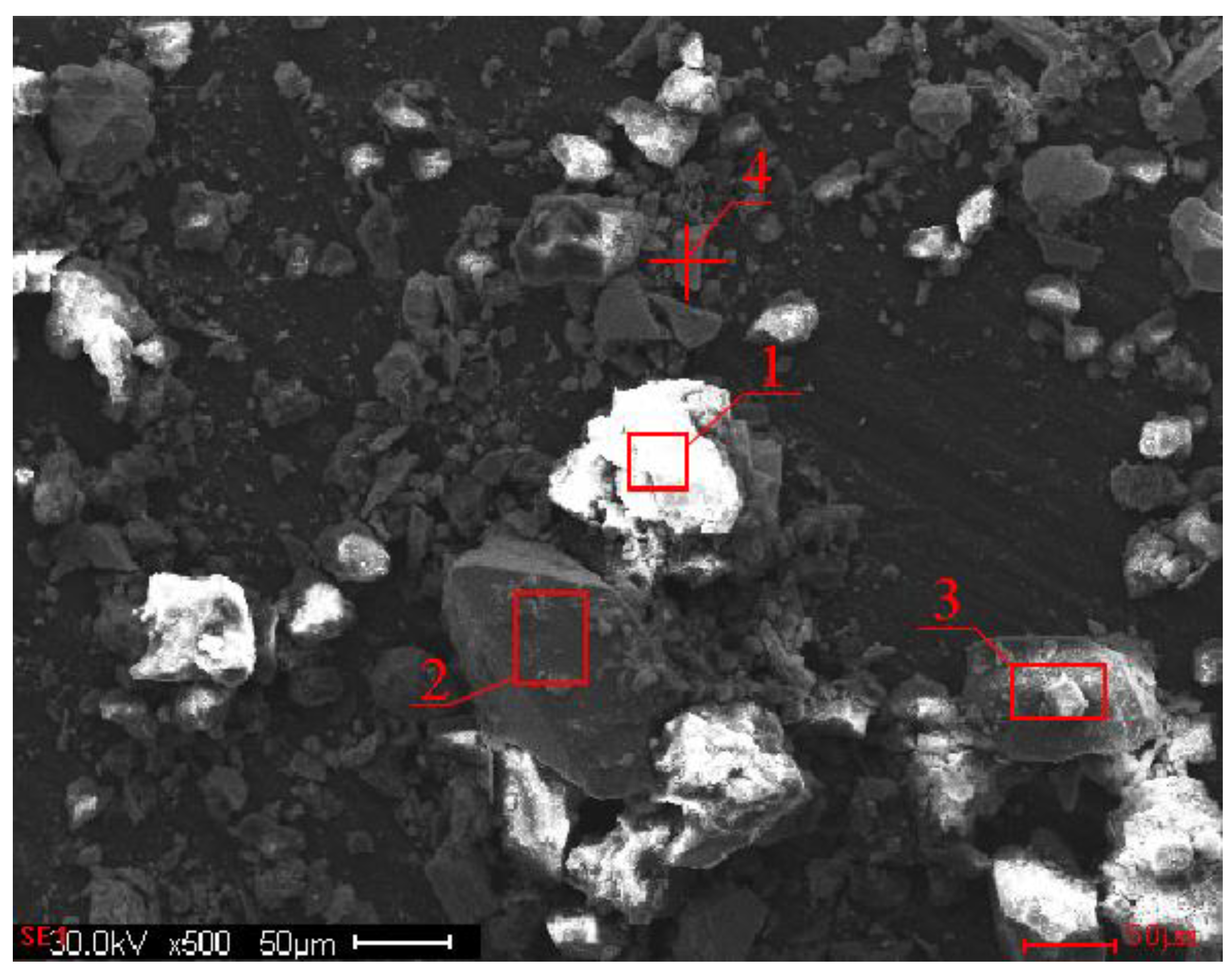

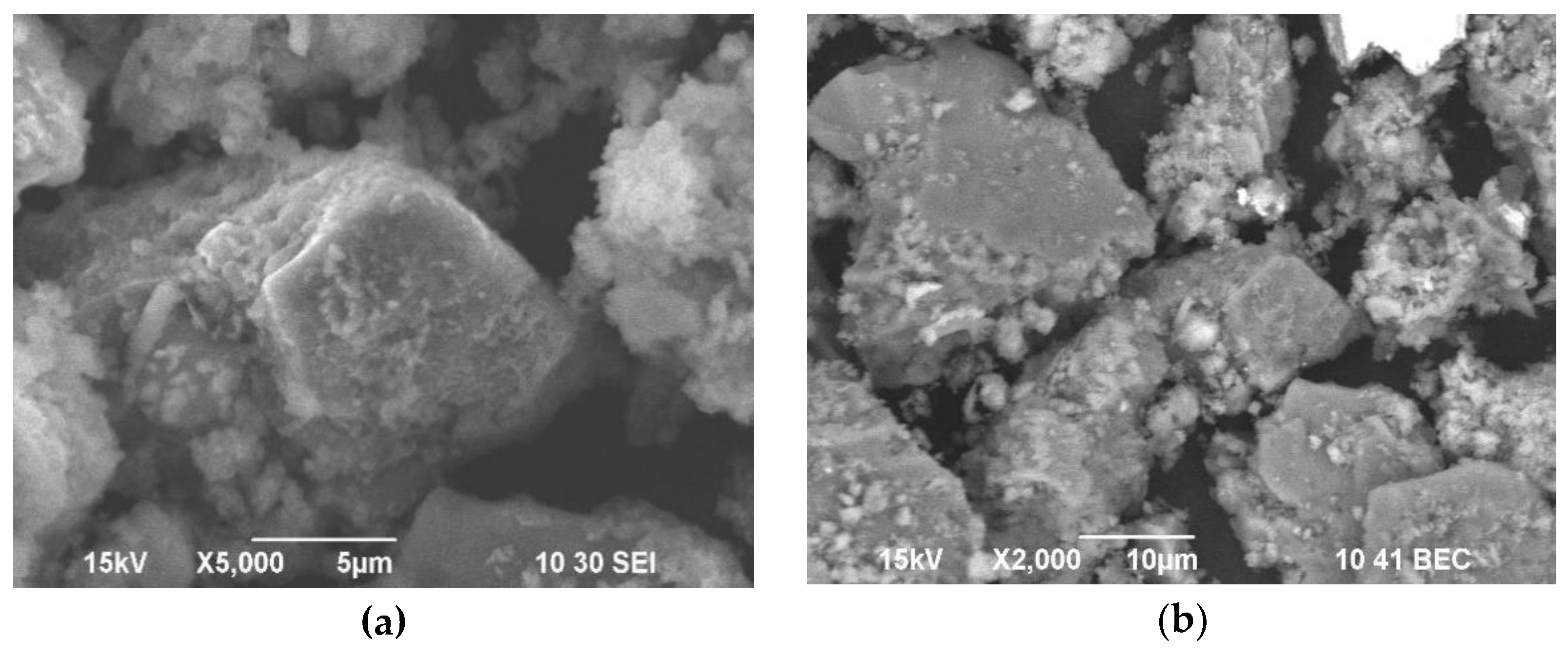

In

Figure 2 and

Table 2 the results of the study of the compositions of individual grains of flotation sulphide concentrate are shown.

It follows from the analysis of the data of

Table 2; the Area 1 of the predominance of Sb

2S

3 and FeS

2 (S 22,29 %, Sb 48,65 %, Fe 12,10 %) has been recorded. In addition to antimonite and pyrite, the presence of SiO

2, CaO (O 8,65%, Si 1,36% and Ca 4,14%) and gold associated with sulphides is probable (Au 1,4 %).

The main elements in area 2 that make up the grain mass of the flotation concentrate are, %: 18,81 As, 10,63 Sb, 39,97 Fe. The content 6,79 % O and 3,21 % Si in the study area shows the presence of silicon. (SiO2). The presence of 0,92 % Au points to the possible association of sulphides.

S – 28,80 %, Sb – 11,72 %, Fe – 36,39 %, O – 10,41 % are the prevailing elements in area 3. Sb2S3, FeS2 have been found in this area. The presence of Fe2O3, SiO2 and CaO is probable.

The spectrum in the point 4 shows peaks characteristic of Sb (67,64 %) and S (22,65 %) indicating the presence of Sb2S3, at this area. Presence of Au in amount 2,34 % indicates it is associated with sulphide minerals.

2.2. Analysis

Chemical analysis of the initial flotation concentrate, sulfide-alkaline and nitric acid leaching cakes was performed using the Axios MAX X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Spectris plc., London, UK). The gold content in the feedstock and leaching products was determined by assay analysis and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry on a NexION 350D (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Phase analysis was carried out on the XRD 7000 Maxima diffractometer (Shimadzu Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The grain size and morphology of the resulting cakes were analyzed using a JEOL JSM-6390LA scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a JED-2300 energy dispersive analyzer. The chemical analysis of the solutions was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass-spectrometry (ICP-MS) using the Elan 9000 instrument (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3. Experimental Procedure

2.3.1. Alkaline Sulphide and Nitric Acid Leaching

The laboratory experiments on alkaline sulphide and nitric acid leaching were implemented at atmospheric pressure in the thermostatted glass reactor with the outer jacket Lenz Minni – 60 (Lenz Laborglas GmbH & Co. KG, Wertheim, Germany) with the volume 500 cm3 at the temperature 50 and 80 °С respectively. Mixing was carried out with a top mounted agitator at 400 rpm. The material portion were added in water and heated up to the set temperature; then alkali/acid was added in gradually. At the end of the experiment the leach pulp was filtered in a Buchner funnel (ECROSKHIM Co., Ltd., St. Petersburg, Russia). The leach cake was washed with distilled water, dried at the temperature 80 °C up to the steady mass, grained on the planetary mill Pulverisette 6 classic line (Fritsch GmbH & Co. KG, Welden Germany), pressed on the backing plate with the help of the hydraulic Vaneox 40t Automatic (Fluxana GmbH & Co. KG., Bedburg-Hau, Germany) and sent for the XRF analysis. Gained solutions”were’diluted to the required concentrations Fe, As and Sb in measuring flasks 25, 50 and 100 dm3 with 1 % nitric acid solution and sent for analysis.

Calculations of free Gibbs energy values and Eh-pH charting were carried out at HSC Chemistry Software v. 9.9 (Metso Outotec Finland Oy, Tampere, Finland).

2.3.2. Electroextraction and Smelting of Cathode Antimony

The electrolysis cell consisted of separate cathode chambers connected in series with the current source. The material of the containers – steel grade DIN 17100. The useful volume of each container was 2,5 dm3. The anode was made of a steel rod which was immersed to the full depth of the reactor. The anode was fixed strictly perpendicular to the bottom of the cathode container on the cover manufactured from polymethilmethocrilate. Electric supply to the bathtub was carried out from the rectifier transformer unit. At the end of the process the cathode antimony together with the electrolyte was separated on Nutch filter. The cathode sediment was washed and dried. The spent electrolyte was analyzed for ballast salts and antimony contain.

The dried cathode sediment was mixed with technical soda and sodium hydroxide in the ratio of 1:1; then it was put in the crucible and smelted in the laboratory muffle furnace Nabertherm L 3/11 (Nabertherm GmbH, Lilienthal, Germany) during 80 minutes at 1000 °С. The melt was chilled to room temperature, antimony and slag were mechanically separated. The attained metallic antimony was sent for XRF analysis.

2.3.3. Decarbonisation

Due to the presence of 15 % dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) and 16 % CaO in cakes after alkaline leaching the consumption of nitric acid increased sufficiently. The operation of decarbonisation is used to remove them.

Sulphuric acid was used in an open glass container at room temperature (25 °С). Mixing was carried out with an agitator (400 rpm). The material was pulped with water before adding sulphuric acid at L:S ratio = 4:1. Sulphuric acid was added in portions till the end of carbon dioxide emission. At the end of the process the pulp obtained was filtered. The received cakes were washed with distilled water, dried at 80 °C until the constant mass was reached, and sent for XRF analysis.

2.3.4. Arsenic Precipitation

After nitric acid leaching the solutions obtained were directed to arsenic precipitation as As2S3. The change of the pH system was recorded with the help of the universal pH-meter Seven2Go (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, Ohio, USA). Filtrate in a volume of 70 cm3 was poured into a glass vessel of 200 cm3 and mixed. Sodium hydrosulphide with a concentration of 72 g/L NaHS was added. The time of sulphuric-arsenic precipitation process was about one hour determined at []. After the precipitation process, the pulp was filtered. The obtained sediment was dried at 60 °С up to the steady mass and was sent for XRF analysis. After the precipitation, the solution was analyzed for the residual As content.

2.3.5. Cyanidation of the Nitric Acid Leach Cake

A leach solution with the concentration NaCN – 2 g/L, NaОН – 2 g/L was poured to a plastic container and portion of nitric leach cake with a mass 100 g was added. The L:S ratio was 3:1, pH = 11. In 24 hours, the pulp was filtered, the cake was washed with distilled water until a washing solution was obtained with a neutral value, dried, weighed, and sent for an gold assay analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theoretical Overview of Sulphide-Alkaline Leaching

Due to amphoterity, antimony is soluble in both acidic and alkaline solutions. However, in industry, a water mixture of sodium- sulphide and caustic soda are used to dissolve antimonite. Alkaline solutions of sodium sulphide act as a universal selective solvent for most of antimony minerals [

39,

40,

41]. Arsenic, tin and mercury minerals dissolve rather slowly [

41,

42,

43,

44]. The dissolution of antimonite can be described as follows (Equation (1)):

Sodium dioxide (NaOH) plays an important role in antimony dissolving – it prevents hydrolysis Na

2S, and the reaction can be proceeded in two stages [

40] (Equations (2)-(3)):

the total reaction is as follows (Equation (4)):

When there is not enough sodium sulphide – the main solvent in the mixture of Na

2S and NaOH, then NaOH is not only as a hydrolysis Na

2S but also an additional solvent for antimony, according to the reaction [

39] (Equation (5)):

Sodium sulphide can also react with oxygen and carbon dioxide in the air atmosphere [

40] (Equations (6)-(7)):

Reaction equations 1 and 5 – antimonite dissolving in sulphide-alkaline solutions. However, side reactions 6 and 7 are undesirable, since they lead to the formation of ballast salts, and it reduces the productivity of the process. In addition to these reactions, thiosulphates are formed in the solution; they are structural analogues of sulphates, where one oxygen atom is replaced by a sulphur atom. The uniqueness of thiosulphates lies in their ability to complex [

45]. Thiosulphates are formed by the following reaction (Equation (8)):

The formation of thiosulphate compounds make strong complex connections with gold (reaction 9) similar to the cyanide process [

45]. Gold and thiosulphate –ion form a strong complex [Au(S

2O

3)

2]

-3 which does not decompose with the release of sulphure when acidified. The gold dissolving process in thiosulphate solution in the presence of oxygen proceeds by the following reaction (Equation (9)):

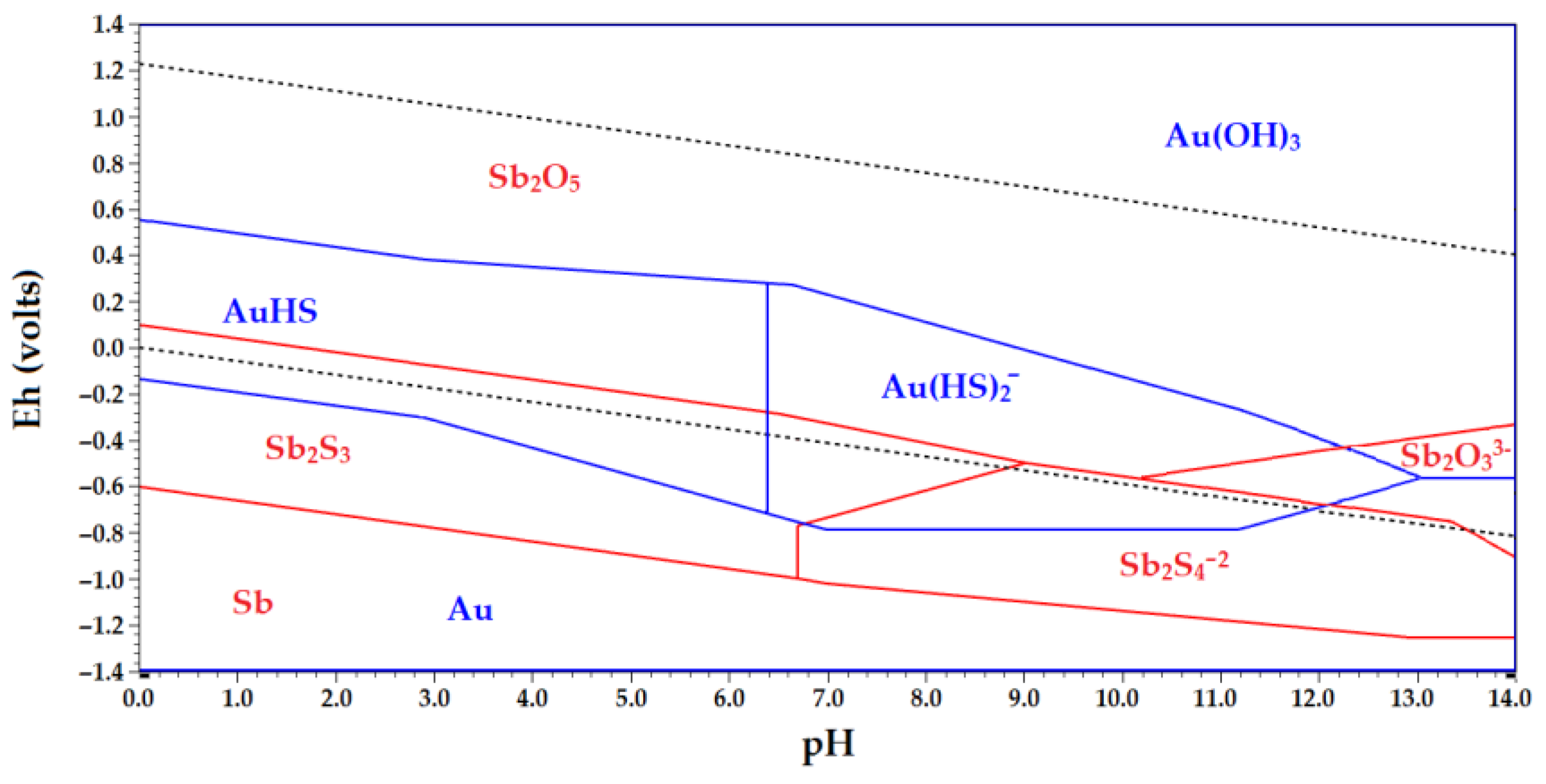

Eh-pH diagram of stable forms for the Sb-Au-S-H

2O system is shown in

Figure 3. According to the thermodynamic data obtained, gold forms soluble compounds Au(HS)

2- AuS

- at pH from 0 to 13. At pH > 13 gold will not pass into solution. In the alkaline area at negative potentials, the solution contains a complex ion [Sb

2S

4]

2-, and also a complex ion of a full oxolydant [Sb

2O

3]

3- [

46].

At the molar concentration at a ratio of (Sb)/(S) = 1/3 the stability area for the strong Sb

2S

3 is shown on the opposite side of the diagram. According to the data [

46,

47], when ratio of (Sb)/(S) reduces to 0,25 25 or less, most of the area represented in the diagram Sb

2S

3 disappears, and the area of water-soluble compounds Sb increases. It follows that antimony leaching from its mineral is most effective at a ratio of (Sb)/(S) ≤ 0,25. For its part, if this ratio will be increased, the potential of antimony electrodeposition will increase, which is beneficial for the subsequent electrolysis of antimony from sulphide electrolytes The practical difficulty with this is that the excessive amount of sulphide-ions is necessary for effective dissolving of antimony from its minerals, and on the other hand, an excess of free sulphide-ion prevents the electrolysis process reducing antimony current output [

41].

3.2. The results of Refined Antimony Production

3.2.1. Alkaline Sulphide Leaching

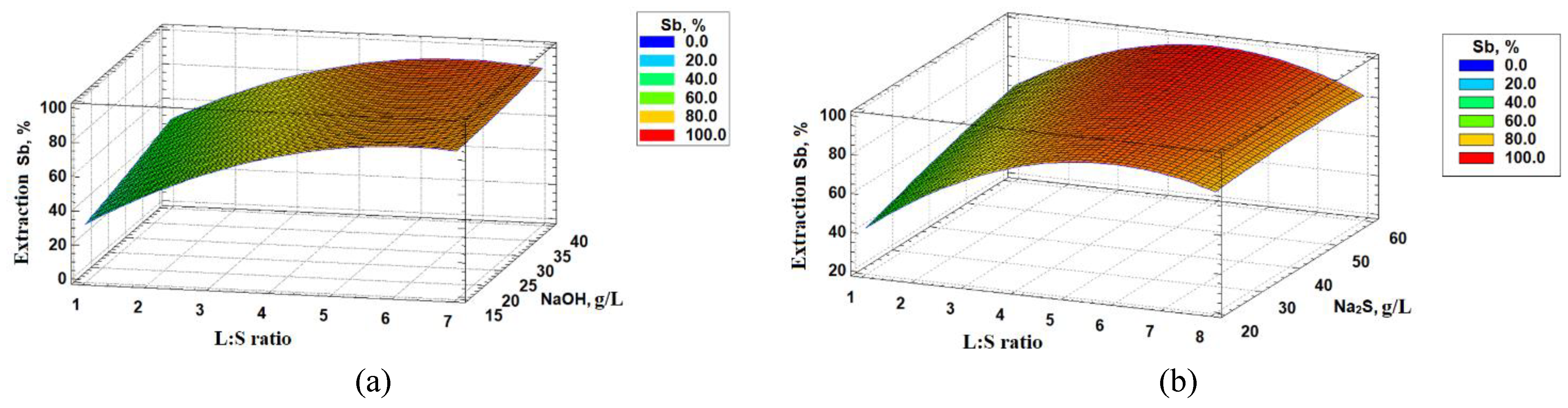

To determine the parameters of alkaline sulphide leaching with the help of Statgraphics software, a central positioning phase with three variable parameters in seventeen experiments has been made. A full quadratic model for processing of the results has been chosen. Antimony extraction in solution is the resultant function. The following factors were chosen as variables: L:S ratio in the pulp which was changed within 1,2 – 6,7, the consumption NaOH – 16,4–43,5 g/L and Na2S – 16,2–61,1 g/L. The leaching time and the temperature were constant – 180 minutes and 50 °С respectively. These ranges were chosen on the basis of the preliminary test experiments.

Obtained response surfaces (Figure. 4) illustrates the extent of antimony recovery at different solvent concentrations and L:S ratio. The increase of L:S ratio raises the index of antimony extraction maximum at the L:S ratio = 4,5:1. However, if this parameter is further increased, a decrease in extraction can be observed. Antimony extraction grows as the solvent concentration increases.

The received results presented as a complete polynomial allow for the assessment of the impact of each factor of antimony extraction (U

Sb) (Equation (10)).

Where X – L:S ratio; Y – the concentration NaOH g/L; Z – the concentration Na2S, g/L.

The determination coefficients R2 equals 95,4%. A high R2 value indicates the adequacy of the chosen quadratic model and the resulting regression equation.

Based on the results obtained, the optimum parameters of the process of alkaline sulphide leaching of the initial flotation concentrate providing maximum antimony extraction in solution have been determined: L:S ratio = 4,5:1; sodium-sulphide – 61 g/L; sodium- hydroxide concentration –16,5 g/L the time – 3 hours and the temperature 50 °С. Antimony extraction in solution in these parameters amounts to 99%.

Chemical composition of the cake after alkaline sulphide leaching presented in

Table 3. The radiograph of the phase analysis is given in

Figure 5.

Based on the results obtained, leach cakes are presented mainly by quarts (SiO2 – 35,41 %), dolomite CaMg(CO3)2 –15,17 %, calcium CaO – 16,34 %, (FeS2 – 7,53 %), arsenopyrite (FeAsS – 7,17) and iron oxide (FeO – 6,1 %).

According to

Figure 6, the particles of the cake under study have pores and caverns on their surface which is connected with the influence of alkaline sulphide solution.

Figure 6 Individual particles after alkaline sulphide leaching at 2000 times (a); and 5000 times (b) magnification.

3.2.2. Antimony Electroextraction

For electrolysis, 8.5 dm3 of a productive solution with an antimony content of 30 g/L was taken. Electrolysis was carried out at the cathode current density 140-150 А/m2, at the anode current density 900-1000 А/m2, bath voltage 2,4-4,0 V, amperage 12 A, the duration 16 hours, the electrolyte temperature 50-55 °С. To increase the efficiency of the process, alkaline and sodium-sulphide were added to the electrolyte (to a concentration in the electrolyte 30 and 60 g/L respectively).

At the end of the process, the antimony cathode was separated together with the electrolyte on Nuthc-filter. The cathode sediment was washed and dried. The spent electrolyte was analyzed for salts and antimony. The weight of the the antimony cathode was 183,6 g. Residual antimony content in the electrolyte – 8,4 g/L; the current output – 63,1 %; the efficiency – 11,4 g/(m2•h), power consumption – 4190 kWh/t.

3.2.3. Refining of Cathode Antimony

The dried cathode was stacked with technical soda and sodium hydroxide in the proportion 1:1 (22,94 g –NaOH and 57,35 g – Na

2CO

3) and placed in a crucible. Smelting was carried out in an induction furnace for 80 minutes at a temperature of 1000 °C [

48].

The melt was cooled to room temperature and the slag was mechanically separated from antimony. The mass of the obtained metallic antimony and slag are 73,98 and 86,62 g respectively. The results of antimony refining are shown in

Table 4.

The refined antimony corresponds to the grade 2N for the manufacture of antifriction, battery, typographic alloys, and alloys for cable sheaths [

49,

50].

3.3. Obtaining gold-bearing residue applicable for cyanidation

3.3.1. Thermodynamic analysis of nitric acid leaching

The main reactions of the disantymonied cake in nitric acid at temperature 353 К are shown in reactions (Equation (11)-(14)).

The oxidation reaction of sulphides has a significant thermoeffect. Reaction 11 is the main reaction in the oxidation of pyrite. This reaction proceeds relatively quickly at a temperature of more than 60 °С and pH is lower than 1,7 [

38]. With a high concentration of nitric acid (more than 50 g/L) a small amount of elemental sulphur is formed even at the relatively low temperatures. At lower concentrations of nitric acid the amount of elemental sulphur increases, especially at low temperatures [

32].

Arsenopyrite is more reactive, so oxidation is probable at room temperature depending on nitric acid concentration. Decomposition of arsenopyrite in nitric acid is accompanied by the formation of elemental sulphur (Equation 14).

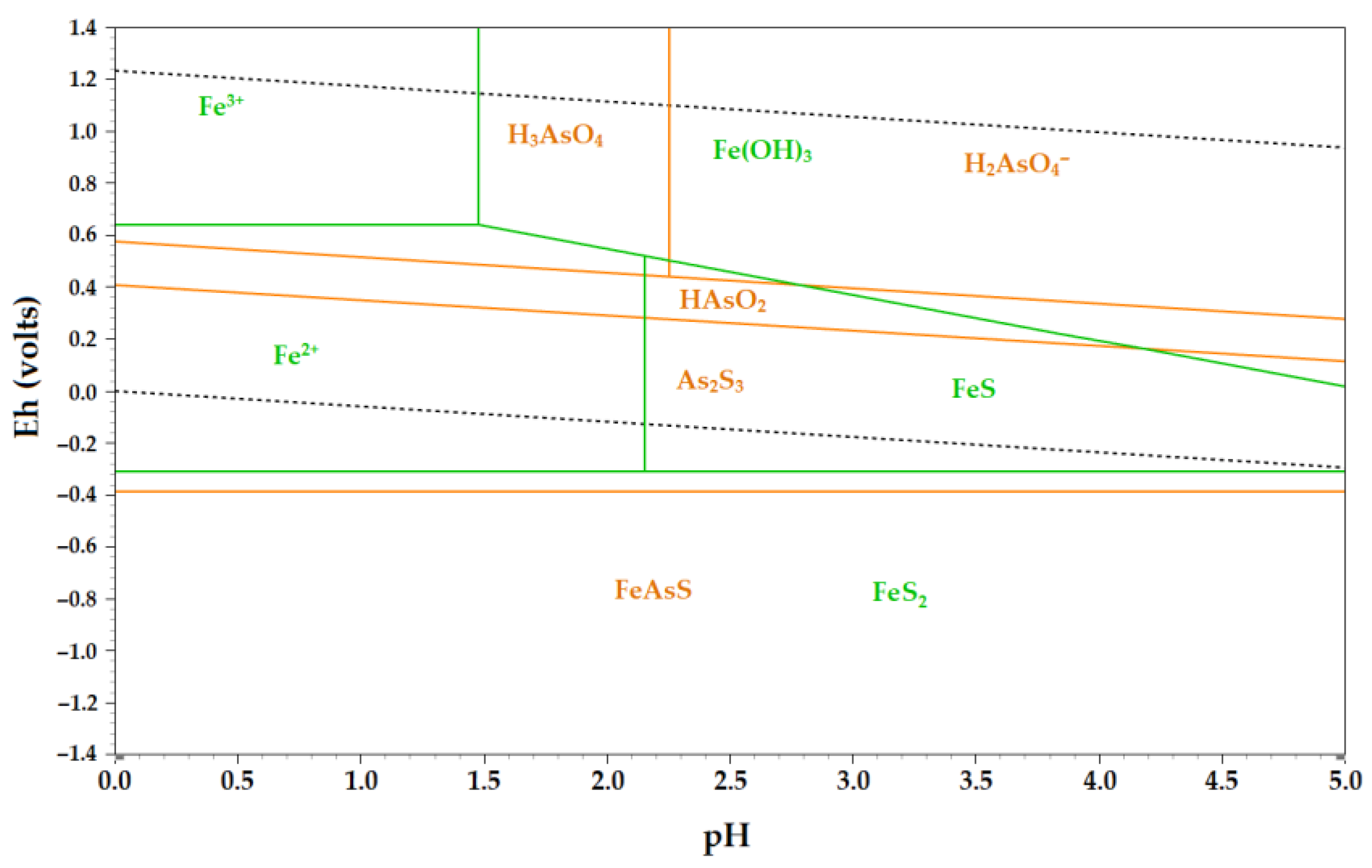

Thermodynamic assessment of pyrite and arsenopyrite behavior in nitric acid was carried out by drawing a Eh-pH diagram (

Figure 7).

It is seen in Fe-S-N-H2O system arsenopyrjte starts dissolving when system potential is 0,39 V with the formation of arsenic sulphide; at a further system protentional increase up to 0,4 V arsenic is converted to the form of meta-arsenic acid, and upon reaching ~ 0,6 V – to the form of ortho-arsenic acid. For its part, pyrite starts decomposing at the value of potential -0,3 V with the formation of cations Fe2+ and FeS, in the further, when reaching the potential of more 0,63 V iron (II) cations transfers to the form Fe (III).

3.3.2. Decarbonisation

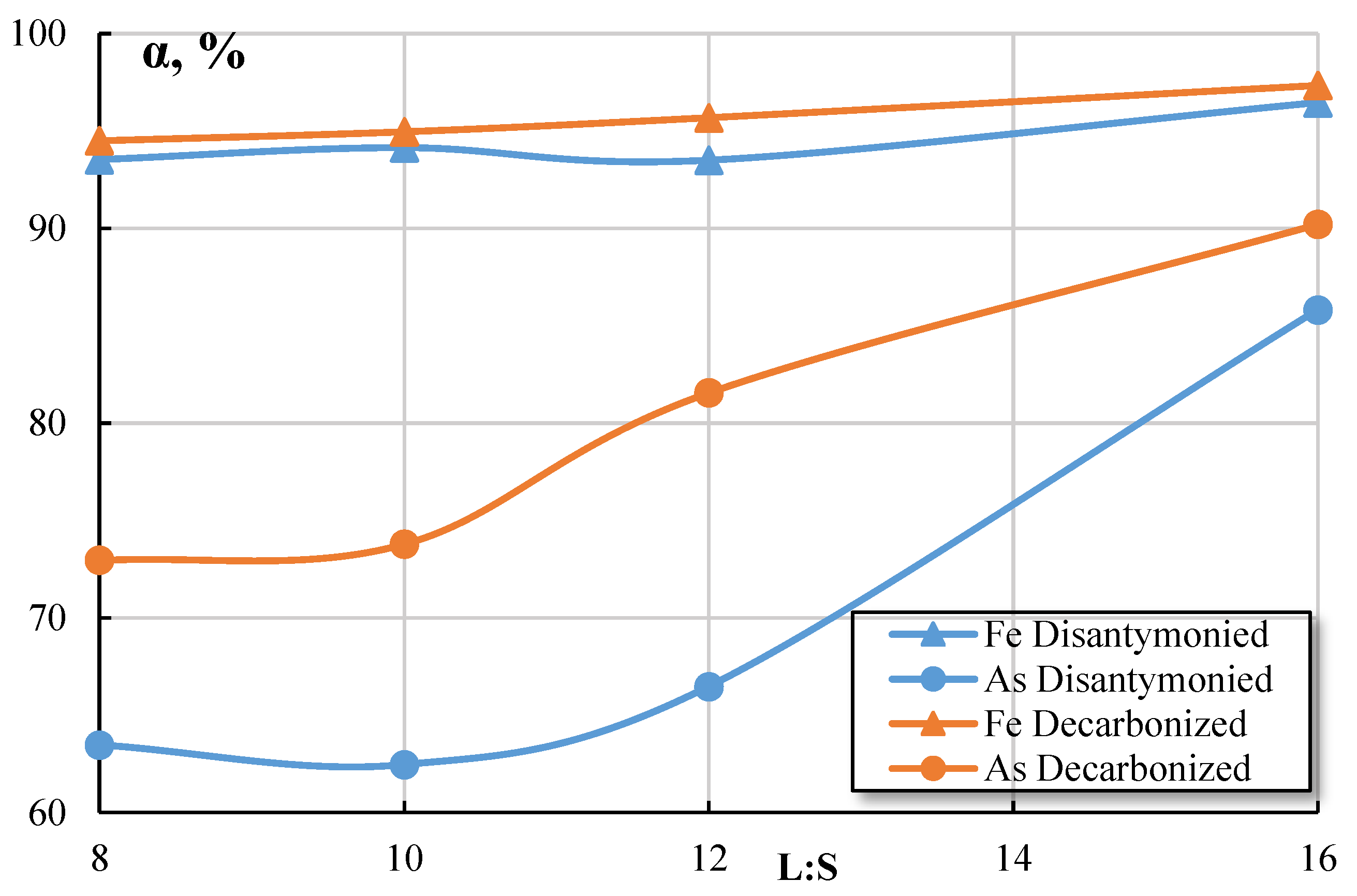

For the purpose of comparison, nitric acid leaching efficiency of the materials obtained (disantymonied and decarbonised cakes) a series of experiments were conducted with the following parameters: nitric acid concentration– 265-900 g/L; L:S ratio = 5-16:1; leaching duration – 80-150 minutes.

The results of nitric acid leaching are shown in

Table 5. According to the data received, extraction of iron and arsenic to the solution when decarbonized cake is leached higher. During cake leaching, nitric acid is primarily used to dissolve CaO and CaMg(CO

3)

2, which reduces the oxidising potential of the system.

Decarbonisation allows to decompose dolomite in form CaSO4, MgSO4 and CO2. Calcium sulphate passes into the cake and does not interfere nitric acid leaching.

Dependencies of iron and arsenic extraction to solution with nitric acid concentration 600 g/L and the time 80 min are shown in

Figure 8. Increasing of the L:S ratio from 8 to 16 influences iron transfer in solution insignificantly: extraction increased from 93,52 to 96,45 % for the disantymonied cakes and from 94,5 to 97,33 % for the decarbonized cake. The extraction of arsenic into solution is higher during leaching of decarbonized cake: with the growth of L:S ratio the extraction increased from 72,95 to 90,2 %. Without additional processing (sulphuric acid), the maximum extraction of arsenic does not exceed 85,81 %.

The composition of disantymonied cake after sulfuric acid treatment is presented in table 6.

3.3.3. Results of Optimizing the Parameters of Nitric Acid Leaching of Decarbonized Cake

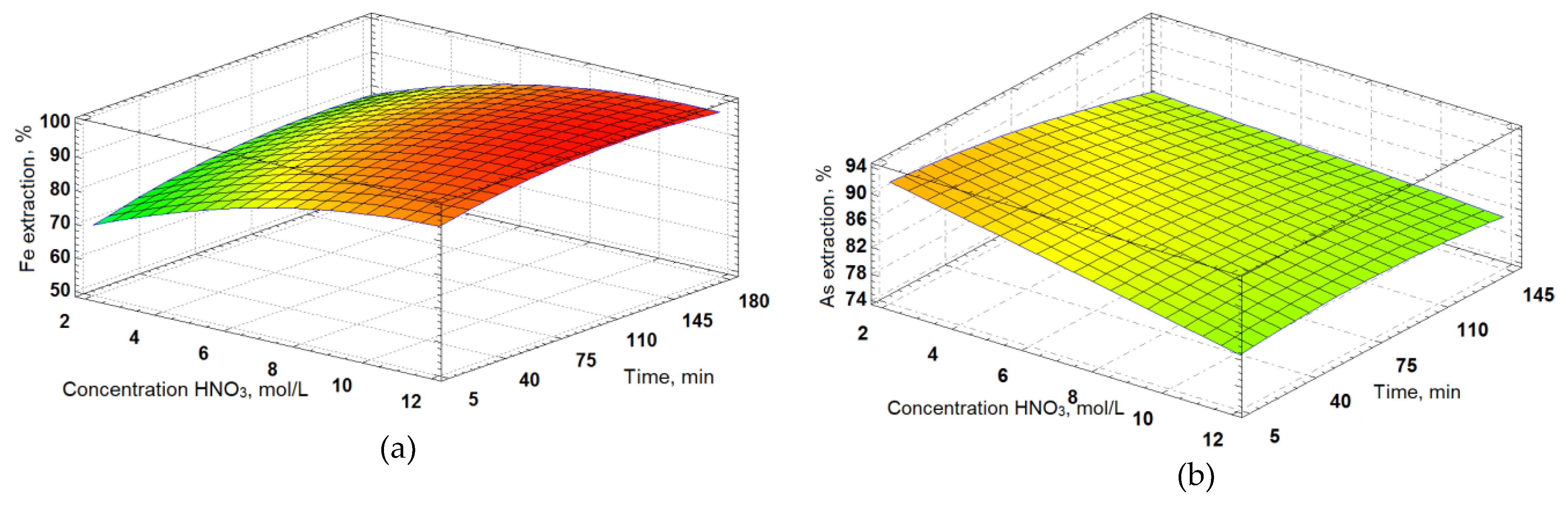

To determine the parameters of nitric acid leaching with the help of Statgraphics software a composition plan with three changeable parameters in 17 experiments was made; a full quadratic model was chosen to process the results. The results obtained were presented as response surfaces (

Figure 9). A general regression equation was derived; the values of determination coefficients R

2 were received. Nitric acid concentration was varied from. 2,5 to 13,4 mol/L, L:S ratio from 2,3–22:1, the leaching time was changed in the range from 8 to 171 minutes.

where X – the value of L:S ratio;

Y – concentration HNO3, mol/L;

Z – the leaching time, min.

The determination coefficients for iron and arsenic R2 were 96,7 and 93,2 %, respectively. This demonstrates the adequacy of the chosen full quadratic model and the regression equation derived.

On the basis of these results, the optimum parameters of the nitric acid leaching of decarbonized sulphide leach cakes that maximize iron and arsenic recovery in solution: L:S ratio = 9:1, nitric acid concentration – 6 mol/L, the leaching time 90 min. Iron and arsenic extraction at these parameters are 98% and 92%, respectively. Chemical composition of the received leach cake is shown in

Table 7. According to the XRD analysis, (

Figure 10), the main phases detected in the residue are anhydride (CaSO

4) and quarts (SiO

2).

3.3.4. The Results of Arsenic Precipitation from the Productive Nitric Acid Leaching Solution

When running the process in one stage, the solution after the nitric acid leaching of the decarbonized cake contains free nitric acid, which has a negative effect on the subsequent stage of arsenic precipitation (sedimenting) from the solution. It leads to increased reagent consumption. To remove free nitric acid and increase the degree of its use, a new portion of the cake was added in abundance (t = 85 °C) after leaching until nitrous gas emission was completed. It stimulates the second stage of the leaching process. The solution obtained had iron and arsenic concentration 41,5 and 23,4 g/L in the solution respectively. Based on the past research [

27] arsenic sedimenting was carried out under the following conditions: stoichiometric flow rate NaHS/As 1,6 at pH 1,96. The sedimenting process completed, the pulp was held for metabolic reactions between iron and arsenic for 10-20 minutes. The extraction of arsenic into the sediment was up to 99,9%.

3.3.5. Gold Cyanidation

The results of cyanidation of the nitric acid leach cake are shown in

Table 8. The degree gold extraction into the solution was 95%.

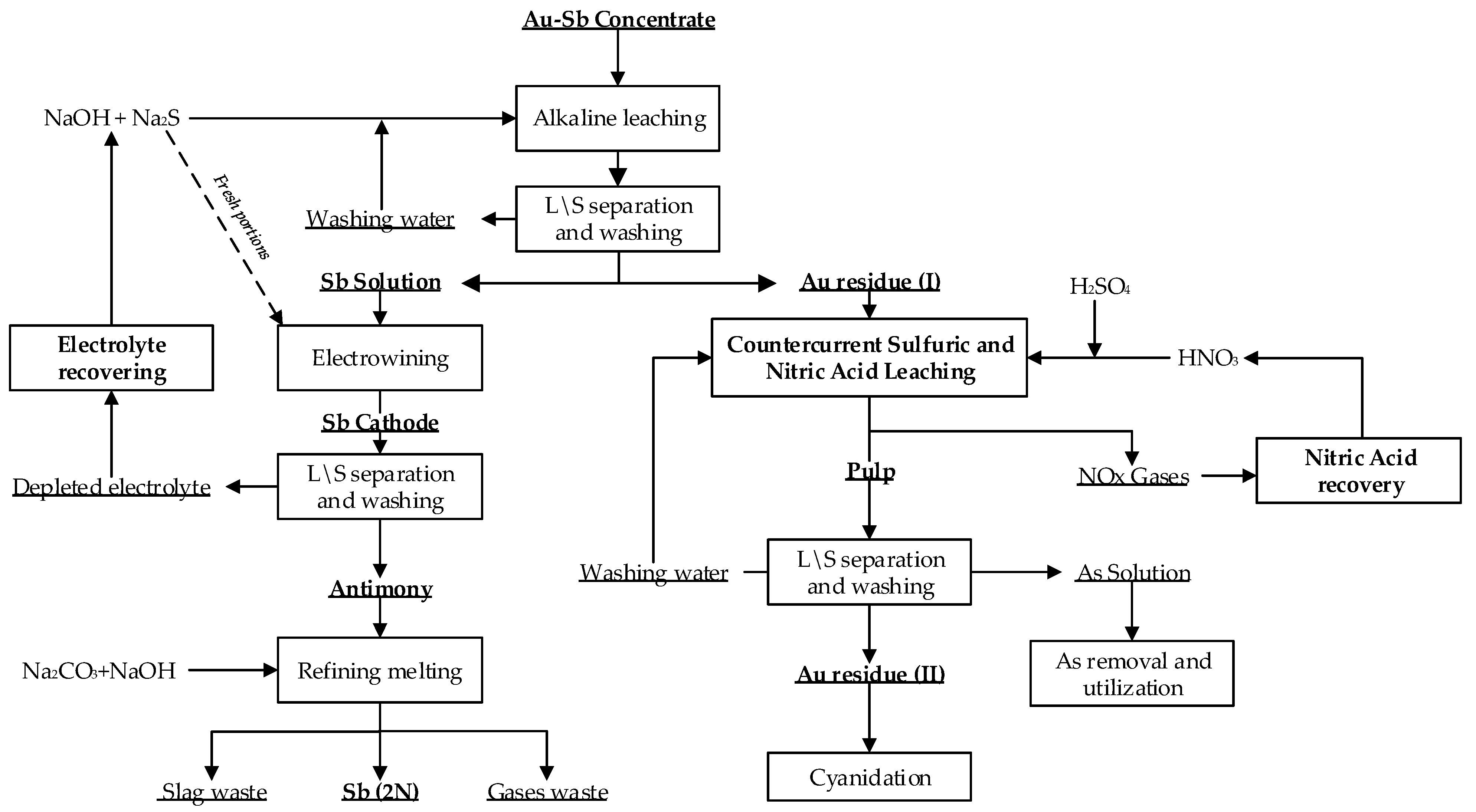

3.3.6. The Principal Technological Flowsheet of Gold-Antimony Concentrate Recycling at the Olimpiadinskoe Deposit

The data obtained during laboratory studies made it possible to propose a basic technological flowsheet for the processing of refractory complex gold-antimony concentrates from the Olimpiadinskoe deposit (

Figure 11)

To increase the efficiency of alkaline sulphide leaching, the process is carried out in a closed cycle. Antimony extraction is carried out on the recycled solutions and reconditioned electrolyte. A part of the solution is drained periodically to remove ballast salts and is directed in circulation again. Purge water is directed to repulping of new batches of concentrates, and the correction of sulphide- alkaline solutions.

The cake obtained after alkaline sulphide leaching is directed to the two-stage countercurrent sulphuric-nitrate leaching. In the first stage, decarbonisation with the help of sulphuric acid and leaching by the enrich of solution from the second stage of leaching takes place. So the excessive amounts of nitric acid is neutralized, and nitric acid regeneration is increased. In the second stage of leaching in the reactor, the process of pre-oxidation of sulphides in the more concentrated nitric acid solutions 5 mol/L takes place. The nitric oxides are directed to nitric acid regeneration. The received undissolved sediment is filtered and washed. The resulting wash water is directed for regeneration of nitric acid and/or for preparation of the new pulp of a new cake batch. The washed gold-bearing cake is sent to cyanidation. The filter is sent to arsenic precipitating after the first stage of leaching.

4. Conclusions

A complex two-stage hydrometallurgical technology of gold-containing concentrate processing with a high antimony and arsenic content at the Olimpiadinskoe deposit has been developed. The findings lead to the following conclusions:

For maximum extracting of antimony to the solution in the alkaline sulphide-leaching and gold transition to cake, it is necessary to support pH>13 to avoid dissociation of sulphide ions with component gold particles.

The recommended parameters for the alkaline sulphide leaching process of the flotation concentrate from the Olimpiadinskoe deposit to ensure maximum antimony into solution at 99 %: L:S ratio = 4,5:1; the sodium sulphide concentration – 61 g/L; sodium hydroxide concentration –16,5 g/L the time-3 hours and the temperature 50 °С.

The synergetic effect of combined treatment of sulphide-alkaline leach cakes with sulphuric and nitric acids has been established. Pre-treatment with sulphuric acid allows to reduce nitric acid consumption by converting carbonates into gypsum and increase arsenic extraction at a later stage of nitric acid leaching by 15%.

The laboratory tests on the nitric acid leaching of the decarbonated cake have identified the main iron and arsenic extraction parameters in the solution (98 and 92 % respectively),: L:S ratio = 9:1; nitric acid concentration – 6 mol/L; the time-90 min. The complete polynomial equations for iron and arsenic extraction from the decarbonised cake were obtained. The model is adequate, since the value of coefficient determination for iron and arsenic R2 96,7 % and 93,2 %. It was found that a high value of gold extraction from the cake of the two-stage alkaline sulphide and nitric acid leaching equals 95%.

A basic technological flowchart for flotation gold-antimony concentrate processing from the Olimpiadinskoe deposit has been developed, including two processes: metallic antimony extraction and gold extraction from the nitric acid leaching cake.

The first process step consists of a alkaline sulphide leaching process, electric antimony extraction and cathode precipitate refining to produce metallic antimony with purity of 2N.

The second process includes decarbonisation of the sulphide-alkaline leach cake, countercurrent nitric acid leaching with nitric acid generation, acidification of solutions with the release of a hard-to-dissolve arsenic sulphide (As2S3), suitable for burial; gold extraction from the resulting cakes from nitric acid leaching.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and D.R.; methodology, O.D.; validation, D.G.; formal analysis, O.D.; investigation, K.K. and R.R.; resources, D.R.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing, D.R. and O.D.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, D.R.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation Project No. 22-79-10290. The XRF, XRD analysis were funded by State Assignment, grant № 075-03-2021-051/5 (FEUZ-2021-0017).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lodeishchikov, V. V. Technology of Gold and Silver Recovery from Refractory Ores; JSC "Irgiredmet" Irkutsk, Russia, 1999; Vol. 2, p. 342.

- Moosavi-Khoonsari, E.; Mostaghel, S.; Siegmund, A.; Cloutier, J.-P. A Review on Pyrometallurgical Extraction of Antimony from Primary Resources: Current Practices and Evolving Processes. Processes 2022, 10, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, S. M. Antimony; Publisher: Moscow, Russia, 1977; p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- Kanarskii, A.V.; Adamov, E.V.; Krylova, L.N. Flotation Concentration of the Sulfide Antimony-arsenic Gold-bearing Ore. Tsvetn. Met. 2012, 53, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.D.; Wills, B.A. Advances in Gold Ore Processing, 1nd ed.; Guildford, Western Australia, 2005; Vol. 15, pp. 907-908.

- Larrabure, G.; Rodríguez-Reyes, J.C.F. A Review on the Negative Impact of Different Elements during Cyanidation of Gold and Silver from Refractory Ores and Strategies to Optimize the Leaching Process. Minerals Engineering 2021, 173, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Rao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; Chen, L. A selective process for extracting antimony from refractory gold ore. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 169, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalev, R.E.; Golovkin, D.I.; Rogozhnikov, D.A. Reducing of Gold Loss in Processing Au-Sb Sulfide Concentrates. AIP "Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Industrial Manufacturing and Metallurgy", Nizhny Tagil, Russia, 17–19 June 2021; Publisher: Nizhny Tagil, Russia, 2022; Vol. 2456, Art. num. 020040. [CrossRef]

- Piervandi, Z. Pretreatment of Refractory Gold Minerals by Ozonation Before the Cyanidation Process: A review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Malfliet, A.; Blanpain, B.; Guo, M. A Review of the Technologies for Antimony Recovery from Refractory Ores and Metallurgical Residues. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalev, R.E.; Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Koblik, A.A. Optimization of Alkaline Sulfide Leaching of Gold-antimony Concentrates. International Russian Conference on Materials Science and Metallurgical Technology, Chelyabinsk, Russia, 1–4 October 2019; Publisher: Chelyabinsk, Russia, 2020; Vol. 989, pp. 525-531. [CrossRef]

- Kuzas, E.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Dizer, O.; Karimov, K.; Shoppert, A.; Suntsov, A.; Zhidkov, I. Kinetic Study on Arsenopyrite Dissolution in Nitric Acid Media by the Rotating Disk Method. Minerals Engineering 2022, 187, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsev, P.; Fomenko, I.; Chugaev, V.L.; Shneerson, M.Y. Pressure Oxidation of Double Refractory Raw Materials in the Presence of limestone. Tsvetn. Met. 2015, 105, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; He, Y. Improving Gold Recovery from a Refractory Ore Via Na2SO4 Assisted Roasting and Alkaline Na2S Leaching. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 185, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.A.; Serrano, J.; Leiva, E. Bioleaching of Arsenic-Bearing Copper Ores. Minerals 2018, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Abashina, T.; Vainshtein, M. Review on Arsenic Removal from Sulfide Minerals: An Emphasis on Enargite and Arsenopyrite. Min. Eng. 2021, 172, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, P.; Dutrizac, J. The Leaching of Tennantite, Tetrahedrite and Enargite in Acidic Sulfate and Chloride Media. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly 2008, 47, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.M.; Radzinski, R.; Ghahreman, A. Review of Arsenic Metallurgy: Treatment of Arsenical Minerals and the Immobilization of Arsenic. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 174, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, S.; Abdollahi, H.; Gharabaghi, M.; Mirmohammadi, M. Selective Leaching of Antimony from Tetrahedrite Rich Concentrate Using Alkaline Sulfide Solution With Experimental Design: Optimization and Kinetic Studies. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2021, 119, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, S.; Sandström, A. Selective Leaching of Arsenic and Antimony from a Tetrahedrite Rich Complex Sulphide Concentrate Using Alkaline Sulphide Solution. Minerals Engineering 2010, 23, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, S.; Samuelsson, C.; Sandström, A. Dissolution Kinetics of Tetrahedrite Mineral in Alkaline Sulphide Media. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 103, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritskii, A.; Naboichenko, S.; Karimov, K.; Agarwal, V.; Lundström, M. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Chalcopyrite Concentrate with Copper Sulfate Solution. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 195, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritskii, A.; Naboichenko, S. Hydrothermal Treatment of Arsenopyrite Particles with CuSO4 Solution. Materials 2021, 23, 7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Li, Q.; Meng, F.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yin, H.; Jiang, T. Bio-Oxidation of a Double Refractory Gold Ore and Investigation of Preg-Robbing of Gold from Thiourea Solution. Metals 2020, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M. The Fate of the Arsenic Species in the Pressure Oxidation of Refractory Gold Ores: Practical and Modelling Aspects. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review 2022, 44, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.; Cézac, P.; Hoadley, A.F.A.; Contamine, F.; D'Hugues, P. A Review of Sulfide Minerals Microbially Assisted Leaching in Stirred Tank Reactors. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation Society 2017, 119, 118–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Kuzas, E.; Dizer, O.; Golovkin, D.; Tretiak, M. Deposition of Arsenic from Nitric Acid Leaching Solutions of Gold-Arsenic Sulphide Concentrates. Metals 2021, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, V.K.; Shneerson, Y.M.; Afanasiev, A.V.; Klementiev, M.V.; Fomenko, V. Short Summary of First Year of the Pokrovskiy Pressure Oxidation Hub Operation. Tsvetn. Met. 2020, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filyanin, G.А.; Vorobev-Desyatovskiy, N.V. Amursk Hydrometallurgical Plant is a Key Element of Processing Unit of Far Eastern “Polymetal” JSC. Tsvetn. Met. 2014, 6, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Artykova, A.; Elkina, Y.; Nechaeva, A.; Melamud, V.; Boduen, A.; Bulaev, A. Options for Increasing the Rate of Bioleaching of Arsenic Containing Copper Concentrate. Microbiology Research 2022, 13, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovmen, V.K.; Belyi, A.V.; Danneker, M.Yu.; Gish, A.A.; Teleutov, A.N. Biooxidation of Refractory Gold Sulfide Concentrate of Olympiada Deposit. Advanced Materials Research 2009, 71–73, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Shoppert, A.A.; Dizer, O.A.; Karimov, K.A.; Rusalev, R.E. Leaching Kinetics of Sulfides from Refractory Gold Concentrates by Nitric Acid. Metals 2019, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsev, P.; Fomenko, I.; Chugaev, V.L.; Shneerson, M.Y. Pressure oxidation of double refractory raw materials in the presence of limestone. Tsvetn. Met. 2015, 8, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisinger, D. Hydrometallurgical process development for complex ores and concentrates. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2009, 109, 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Twidwell, L. Hydrometallurgical processing of gold-bearing copper enargite concentrates. The Canadian Journal of Metallurgy and Materials Science 2008, 47, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G.; Fayram, T.S.; Twidwell, L.G. NSC Hydrometallurgical Pressure Oxidation of Combined Copper and Molybdenum Concentrates. Journal of Powder Metallurgy and Mining 2013, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G. NSC Pressure Leaching: Industrial and Potential Applications. Hydrometallurgy 2008: Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium, SME, 858−885.

- Sudakov, D.V.; Chelnokov, S.Yu.; Rusalev, R.E.; Elshin, A.N. Technology and Equipment for Hydrometallurgical Oxidation of Refractory Gold-Bearing Concentrates (ES-Process). Tsvetn. Met. 2017, 3, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sminčáková, E. Leaching of Natural Stibnite Using Na2S and NaOH Solutions. International Journal of Energy Engineering 2011, 1, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sminčáková, E.; Raschman, P. Leaching of Stibnite by Mixed Na2S and NaOH Solutions. ACTA TECHNICA CORVINIENSIS–Bulletin of Engineering 2012, 5, 35–37, ISSN 2067-3809. [Google Scholar]

- Awe, S.A.; Sandström, Å. Selective Leaching of Arsenic and Antimony from a Tetrahedrite Rich Complex Sulphide Concentrate Using Alkaline Sulphide Solution. Minerals Engineering 2010, 23, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfini, M.; Ferrini, M.; Manni, A.; Massacci, P.; Piga, L. Arsenic Leaching by Na2S to Decontaminate Tailings Coming from Colemanite Processing. Minerals Engineering 2003, 16, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaldini, S.; Veglio, F.; Fornari, P.; Abbruzzese, C. Process Flow–sheet for Gold Antimony Recovery From. Hydrometallurgy 2000, 57, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Qin, W. Selective leaching of arsenic from enargite concentrate using alkaline leaching in the presence of pyrite. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 181, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakovskii, I.A.; Yu. M. Potashnikov Yu. M. The Kinetics of the Dissolution of Cupric Sulfide in Aqueous Potassium Cyanide Solutions. Dokl. Chem. Technol 1964, 158, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Avraamides, J.; Drok, K.; Durack, G.; Ritchie, I.M. Effect of Antimony (III) on Gold leaching in Aerated Cyanide Solutions: a rotating electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance study. Processing and Environmental Aspects of As, Sb, Se, Te, and Bi. International Journal of Surface Mining, Reclamation and Environment 2000, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solozhenkin, P.M.; Alekseev, A.N. Innovative Processing and Hydrometallurgical Treatment Methods for Complex Antimony Ores and Concentrates. Part II: Hydrometallurgy of Complex Antimony Ores. Journal of Mining Science 2010, 46, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, I.; Nasir, S.; Zahra, S.; Aamir, M.; Mahmood, Z.; Akram, A. Metal Extraction Process for High Grade Stibnite of Kharan (Balochistan Pakistan). Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering 2017, 5, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.G.; Yang, G.H.; Tang, C.B. The Membrane Electrowinning Separation of Antimony from a Stibnite Concentrate. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions 2010, 41, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembele, S.; Akcil, A.; Panda, S. Technological Trends, Emerging Applications and Metallurgical Strategies in Antimony Recovery from Stibnite. Minerals Engineering 2022, 175, 107304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the gold-antimony concentrate phase composition.

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the gold-antimony concentrate phase composition.

Figure 2.

A microphotography of universal particles of the initial concentrate at the Olimpiadinskoe deposit.

Figure 2.

A microphotography of universal particles of the initial concentrate at the Olimpiadinskoe deposit.

Figure 3.

Eh-pH diagram for Au-Sb-S-H2O system at 25°С.

Figure 3.

Eh-pH diagram for Au-Sb-S-H2O system at 25°С.

Figure 4.

Dependencies of antimony extraction (a) on L:S ratio and concentration NaOH (b) on L:S ratio and concentration Na2S.

Figure 4.

Dependencies of antimony extraction (a) on L:S ratio and concentration NaOH (b) on L:S ratio and concentration Na2S.

Figure 5.

The diffractogram of the cake after alkaline sulphide leaching.

Figure 5.

The diffractogram of the cake after alkaline sulphide leaching.

Figure 6.

Individual particles after alkaline sulphide leaching at 2000 times (a); and 5000 times (b) magnification.

Figure 6.

Individual particles after alkaline sulphide leaching at 2000 times (a); and 5000 times (b) magnification.

Figure 7.

Eh-pH diagram for Fe-As-S-N-H2O system.

Figure 7.

Eh-pH diagram for Fe-As-S-N-H2O system.

Figure 8.

Dependences of Fe and As extraction on L:S ratio.

Figure 8.

Dependences of Fe and As extraction on L:S ratio.

Figure 9.

Dependencies of (a) iron extraction at L:S ratio 2:1 and (b) arsenic extraction at L:S ratio 9:1 on the time of the experiments and acid consumption

Figure 9.

Dependencies of (a) iron extraction at L:S ratio 2:1 and (b) arsenic extraction at L:S ratio 9:1 on the time of the experiments and acid consumption

Figure 10.

The radiograph of the undissolved residue after nitric acid leaching.

Figure 10.

The radiograph of the undissolved residue after nitric acid leaching.

Figure 11.

The principal technological flowsheet of processing of Au-Sb flotation concentrate at the Olimpiadinskoe deposit.

Figure 11.

The principal technological flowsheet of processing of Au-Sb flotation concentrate at the Olimpiadinskoe deposit.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the gold-antimony concentrate.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the gold-antimony concentrate.

| Element |

As |

Ca |

Fe |

Mg |

S |

Sb |

Si |

Al |

Others |

Au (g/t) |

| Wt., % |

1,9 |

13,4 |

8,95 |

1,46 |

11,46 |

19,18 |

18,6 |

1,69 |

23,36 |

66,00 |

Table 2.

The study results of individual grains of the initial concentrate from Olympiadinsky deposit.

Table 2.

The study results of individual grains of the initial concentrate from Olympiadinsky deposit.

| Element |

Area 1 |

Area 2 |

Area 3 |

Point 4 |

| Wt.% |

At.% |

Wt.% |

At.% |

Wt.% |

At.% |

Wt.% |

At.% |

|

OK

|

8,65 |

26,63 |

6,79 |

19,34 |

10,41 |

25,14 |

2,48 |

9,97 |

|

AsL

|

1,42 |

0,93 |

18,81 |

11,44 |

1,64 |

0,84 |

0,4 |

0,34 |

|

SiK

|

1,36 |

2,38 |

3,21 |

5,21 |

1,63 |

2,25 |

1,48 |

3,38 |

|

AuM

|

1,40 |

0,35 |

0,92 |

0,21 |

1,16 |

0,23 |

2,34 |

0,76 |

|

SK

|

22,29 |

34,25 |

17,03 |

24,2 |

28,8 |

34,69 |

22,65 |

45,39 |

|

SbL

|

48,65 |

19,69 |

10,63 |

3,98 |

11,72 |

3,72 |

67,64 |

35,69 |

|

CaK

|

4,14 |

5,09 |

2,64 |

3,00 |

8,26 |

7,96 |

2,21 |

3,54 |

|

FeK

|

12,10 |

10,67 |

39,97 |

32,62 |

36,39 |

25,17 |

0,80 |

0,92 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the cake after alkaline sulphide leaching.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the cake after alkaline sulphide leaching.

| Element |

As |

Ca |

Fe |

Mg |

S |

Sb |

Si |

Others |

Au (g/t) |

| Wt., % |

1,73 |

12,4 |

6,84 |

1,54 |

6,84 |

0,08 |

18,6 |

39,67 |

78,00 |

Table 4.

Antimony melting results, Wt. %.

Table 4.

Antimony melting results, Wt. %.

| Product Name |

Sb |

S |

As |

Fe |

Al |

Ca |

Si |

| Antimony cathode |

92,1 |

2,6 |

0,73 |

3,35 |

0,23 |

0,1 |

0,95 |

| Refined antimony |

99,759 |

0,05 |

0,02 |

0,03 |

0,02 |

0,05 |

0,1 |

| Slag |

0,24 |

2,37 |

0,66 |

3,08 |

0,20 |

5,04 |

0,80 |

Table 5.

The results of nitric acid leaching of decarbonized and disantymonied cakes.

Table 5.

The results of nitric acid leaching of decarbonized and disantymonied cakes.

| № |

HNO3, g/L |

L:S |

Duration, min |

Extraction, % |

| Fe |

As |

| Decarbonized cakes |

| 1 |

265 |

5 |

150 |

93,11 |

77,62 |

| 2 |

630 |

5 |

120 |

92,17 |

69,78 |

| 3 |

900 |

7 |

150 |

96,23 |

72,11 |

| 4 |

600 |

8 |

80 |

94,5 |

72,95 |

| 5 |

600 |

10 |

80 |

94,36 |

73,78 |

| 6 |

600 |

12 |

80 |

95,68 |

81,55 |

| 7 |

600 |

16 |

80 |

97,33 |

90,2 |

| Disantymonied cakes |

| 8 |

265 |

5 |

150 |

86,42 |

68,49 |

| 9 |

630 |

5 |

120 |

90,58 |

46,41 |

| 10 |

900 |

7 |

150 |

90,66 |

52,72 |

| 11 |

600 |

10 |

80 |

94,13 |

62,45 |

| 12 |

600 |

8 |

80 |

93,52 |

63,46 |

| 13 |

600 |

12 |

80 |

92,49 |

66,46 |

| 14 |

600 |

16 |

80 |

97,45 |

85,81 |

Table 6.

Chemical composition of decarbonized cake.

Table 6.

Chemical composition of decarbonized cake.

| Element |

As |

Ca |

Fe |

S |

Sb |

Si |

Others |

| Wt.,% |

3,40 |

14,80 |

11,10 |

19,00 |

4,40 |

16.40 |

30,9 |

Table 7.

Chemical composition of nitric acid leach cake.

Table 7.

Chemical composition of nitric acid leach cake.

| Element |

As |

Ca |

Fe |

K |

Mg |

S |

Sb |

Si |

O |

Au (g/t) |

| Wt.,% |

0,39 |

11,3 |

0,25 |

0,58 |

0,12 |

14,5 |

3,14 |

16,20 |

54,22 |

101,40 |

Table 8.

Gold cyanidation results.

Table 8.

Gold cyanidation results.

| Material |

Au |

| g/t |

Extraction, % |

| Cake after HNO3 |

101,4 |

0 |

| Cake after cyanidation |

5,07 |

95 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).