1. Introduction

Although the interactions between two ferromagnetic (FM) thin films separated by a non-magnetic metallic spacer layer were a point of interest in the last two decades, it is still receiving notable consideration due to their potential applications [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The interplay of magnetic ordering and exchange coupling continues to play an important role in technological advancements. The investigation of long-range exchange coupling in heterogeneous structures, such as transition metal /rare earth compounds, continues to attract the attention of scientists due to the potential to harvesting antiferromagnetic (AFM) ordering via the RKKY interaction [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The orbital contribution to the total magnetic moment from rare earth metal and the oscillating nature of the long-range exchange interaction provide great avenue to engineer a structure that exhibits no net magnetic moment while possessing a spin polarization. This would effectively separate the spin degree of freedom from the net magnetization and allow us to explore the hypothetical spin-spin and spin-mass interactions. These interactions are due to as yet unobserved force mediating bosons which result in Yukawa-like potentials and are possible dark matter candidates [

18,

19,

20,

21]. This provides an interesting platform for spintronic applications.

Among other consequences, the exchange interaction is responsible for the FM and AFM phases of the compound matter [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Multilayered structure oscillatory exchange-coupling across a non-magnetic spacer layer can be used to engineer synthetic magnetic structures. A magnetic multilayer structure consists of a sequence of different thin films growing on top of each other. Thin films of FM material are separated from each other by a non-magnetic material (spacer layer). A non-magnetic layer with a small thickness plays a crucial role in the FM and AFM coupling between two magnetic thin films [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The magnetizations of the FM layers separated by the non-magnetic spacer layers are coupled by the electrons in the spacer layers. To create a multilayer structure with nonzero spin and zero magnetization, here we explore the multilayer system composed of a transition metal FM layer and a rare earth FM layer with AFM alignment between two layers. The Nd-Fe-B-based thin films have been widely investigated in both industry and research labs due to their applications in nanomagnetic devices, nanomechanical devices, and magnetic recording media [

31,

32,

33]. Crystalline phases of Nd-Fe-B show different characteristics such as magnetization and coercivity. To take advantage of these great features, it is essential to optimize the nano-crystallization of the deposited amorphous films. So far, various approaches have been utilized to prepare high-quality Nd-Fe-B thin films [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In the case of magnetron sputtering fabrication, several preparation parameters, such as the pressure in the chamber, deposition temperature, post-deposition treatment, target composition, substrate material, and thickness of the buffer layer, can significantly affect the structure of the films and their final magnetic properties. Achieving a well-crystalized magnetic hard phase Nd-Fe-B thin film is crucial to develop a structure with spin-polarized mass with zero magnetization.

2. Materials and Methods

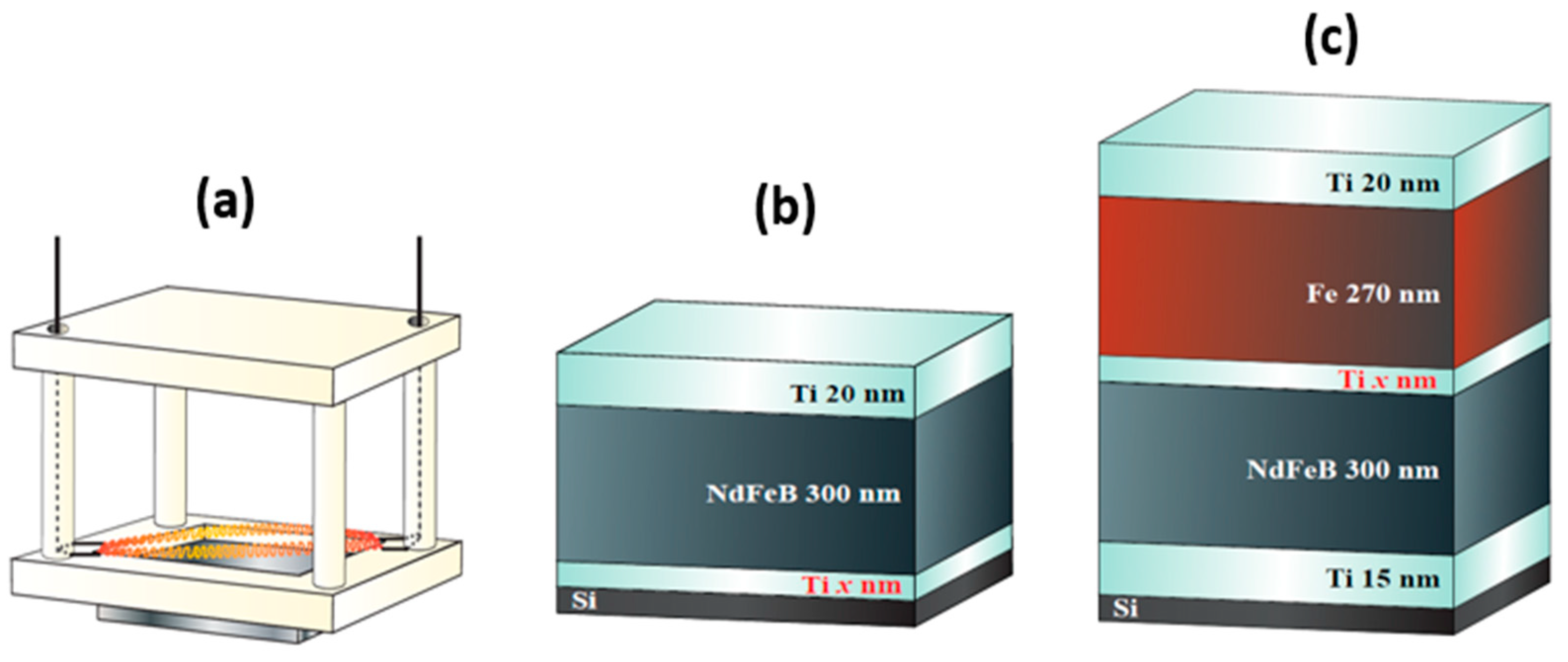

The process of creating the multilayered structures with a well-defined interface for our study evolved into an investigation of the optimal approach for thin film growth. In order to prepare high-quality crystalized Nd-Fe-B thin films a vacuum heater was designed and developed using vacuum-compatible ceramic materials. This heater enables us to fabricate thin films at temperatures up to 700◦C during sputtering. Heating the sample during deposition leads to a better interface for multilayer structure compared to post-annealing outside of the deposition chamber. Moreover, post-annealing of all layers would lead to diffusion between layers and dramatically influence the quality of the multilayered structure. In our design, various parameters were considered to achieve a stable high temperature with minimum fluctuations during heating inside the vacuum chamber. To improve the efficiency, two parallel tungsten filaments were used, and a Molybdenum plate was utilized as a sample holder due to its high thermal conductivity, as shown in

Figure 1a. The heater’s power depends on the parameters of the filament such as length, cross-section area, and the purity of the tungsten used. With the optimal parameters such as two parallel 11 cm tungsten (99.9% purity) filaments wires with the cross-section of 0.025 mm

2, the maximum power of the heater is around 700 W with a maximum voltage of 20 volts provided by the accessible power supply. Furthermore, to increase the efficiency of the heater a ceramic shielding box covered by reflective tantalum foil was installed. This configuration enhances the reflection of photons from the walls of the heater to the sample holder, therefore leading to high heating efficiency. Our experiments have shown that the ceramic box increased the efficiency of the heater by about 25%. Furthermore, the shielding box prevents photons and hot electrons from emitting everywhere in the chamber, resulting in better control of the stability of the temperature and the pressure of the chamber during the deposition. The temperature was stable over the deposition and was read continuously with a thermometer connected to the sample holder by a thermocouple.

In a high vacuum environment with the base pressure of 7 ×10

-7 Torr, several Nd-Fe-B monolayer structures with a thickness of 300 nm were created using a sputtering target with the composition of Nd

20Fe

64B

16 (

Figure 1b). All the samples were deposited on single-crystal silicon substrates while they were annealed in situ at different temperatures (600°C and 650°C). Annealing continued for 20 more minutes after finishing deposition to create a homogeneous crystalline of Nd

2Fe

14B phases. Finally, after cooling down, a 20 nm Ti layer was added, and a 20 nm Ti layer was added after cooling down to prevent oxidation for subsequent characterization. The effect of Ti buffer layer thickness on the crystalline formation of Nd

2Fe

14B was also investigated.

Magnetic coupling between two ferromagnets, a soft phase Fe and a hard phase Nd-Fe-B primarily in the Nd

2Fe

14B phase was systematically studied through a house-developed vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) [

40] and X-ray diffraction (XRD). All samples were grown via DC magnetron sputtering in a high vacuum environment. All three targets, Nd

20Fe

64B

16, iron (Fe), and titanium (Ti) targets were installed in the same sputtering chamber, which facilitated the in-situ growth of the entire structure, intending to minimize the oxidation. For the exchange interaction study, multilayered structures are shown in

Figure 1C, with different thicknesses of the Ti spacer layer, were fabricated. 300 nm of Nd

2Fe

14B was sputtered onto a silicon substrate with a 15 nm Ti buffer layer and annealed at 650◦C from the results of single layer Nd-Fe-B thin film studies, followed by a Ti spacer layer of X (0 - 5) nm thickness, and a 270 nm Fe layer, which will be presented in the result section. A thin Ti capping layer (20 nm) was added to avoid oxidation. The growth ratio for all three targets of Ti, Fe and Nd-Fe-B were calibrated while the pressure of introduced pressure of Ar gas was fixed on 4 mTorr, however, for the Ti layer used as a spacer layer the deposition growth rate was relatively a smaller number (1 nm/min) to achieve a more uniform film without a pinhole. In situ annealing processing was performed based on the results from single-layer test samples. Then samples were cool cooled down at the rate of 3◦C/ min until room temperature. The next day Ti spacer layer, Fe layer, and Ti capping layer sputtered at room temperature. Fabrication of the thickness of each FM layer of multilayered structure to achieve a zero magnetization while possessing net spin while FM layers interact with each other completely antiferromagnetically from RKKY theory is calculated in the supplementary materials.

3. Results and Discussion

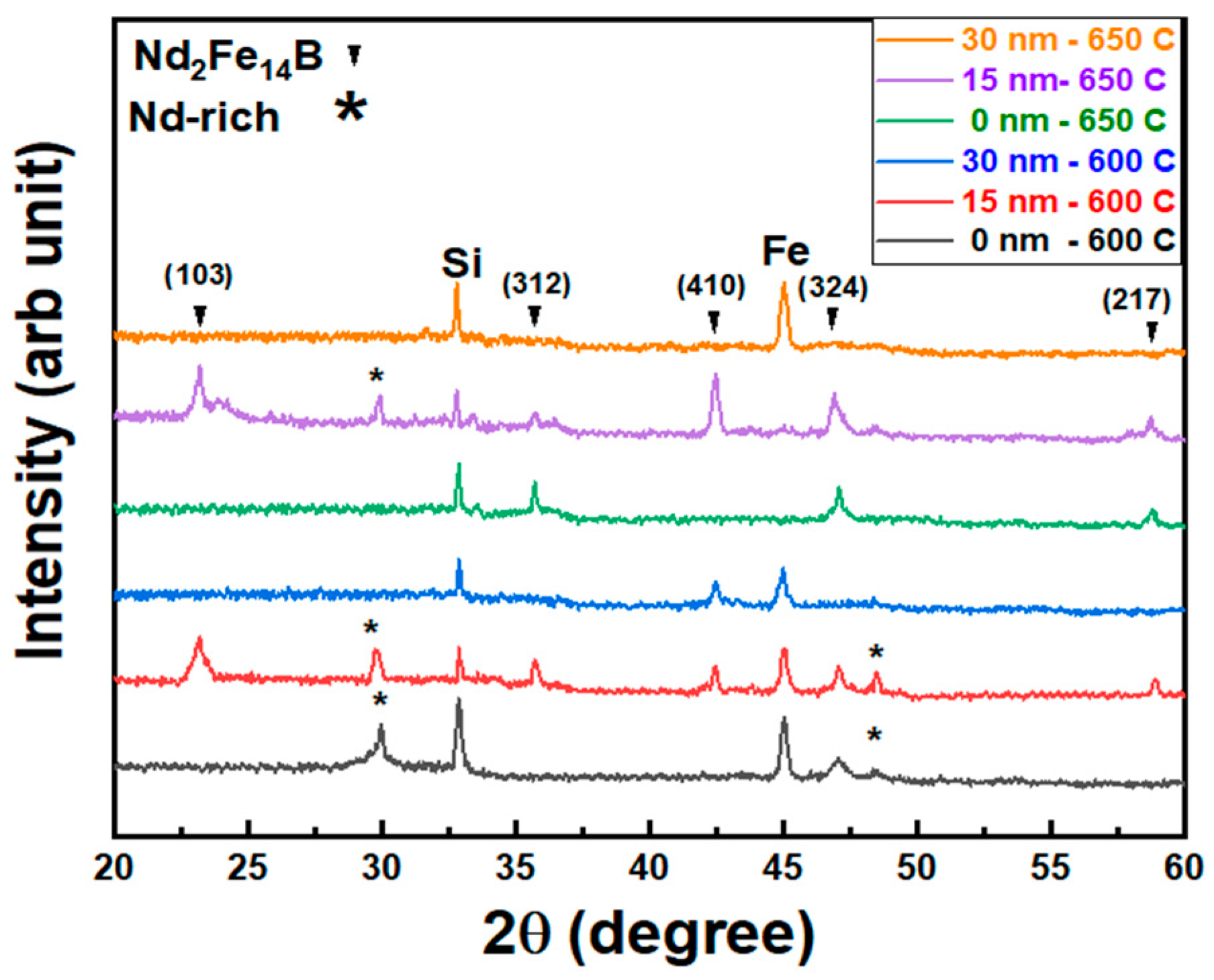

Various phases of single-layer Nd-Fe-B thin film fabricated with different thicknesses of the Ti buffer layer and annealed in situ at different temperatures are studied using XRD. As shown in

Figure 2, the marked points indicate the XRD peaks corresponding to the tetragonal Nd

2Fe

14B phase. The XRD data indicates that the structure of the thin films depends upon the in situ annealing temperature and the buffer layer thickness. Nano-crystalline Nd

2Fe

14B formation does not occur at temperatures below 600°C. It is known that an amorphous SiO

2 layer with a thickness below 30 nm can form on the Si surface. If the Nd-Fe-B film is directly deposited on the bare Si substrate, the Nd atoms will react with the SiO

2 layer at high temperatures, and it can lead to defects in the Nd

2Fe

14B phase formation.

Based on the XRD data of samples fabricated with different buffer layers at 600°C and 650°C, more crystalline phases of Nd2Fe14B formed when the thickness of the buffer layer is 15 nm. The sample with a 30 nm Ti buffer layer and annealed in situ at 600°C exhibits only (410) peak of Nd2Fe14B at around a 2-theta value of 43°. A sample with the same Ti buffer layer thickness annealed at 650°C does not show an obvious Nd2Fe14B peak, however, a Fe peak with high intensity suggests that Fe atoms were not coupled with rare earth Nd and B atoms to form Nd2Fe14B crystalline phase. Samples created with a 15 nm Ti and in situ annealed at 650°C showed the most crystalline phase of Nd2Fe14B. A proper thickness of the buffer layer can reduce the roughness of the film and protect the thin film from oxidization. An excessively thick buffer layer leads to large surface roughness. The optimal buffer layer thickness is determined to be 15 nm.

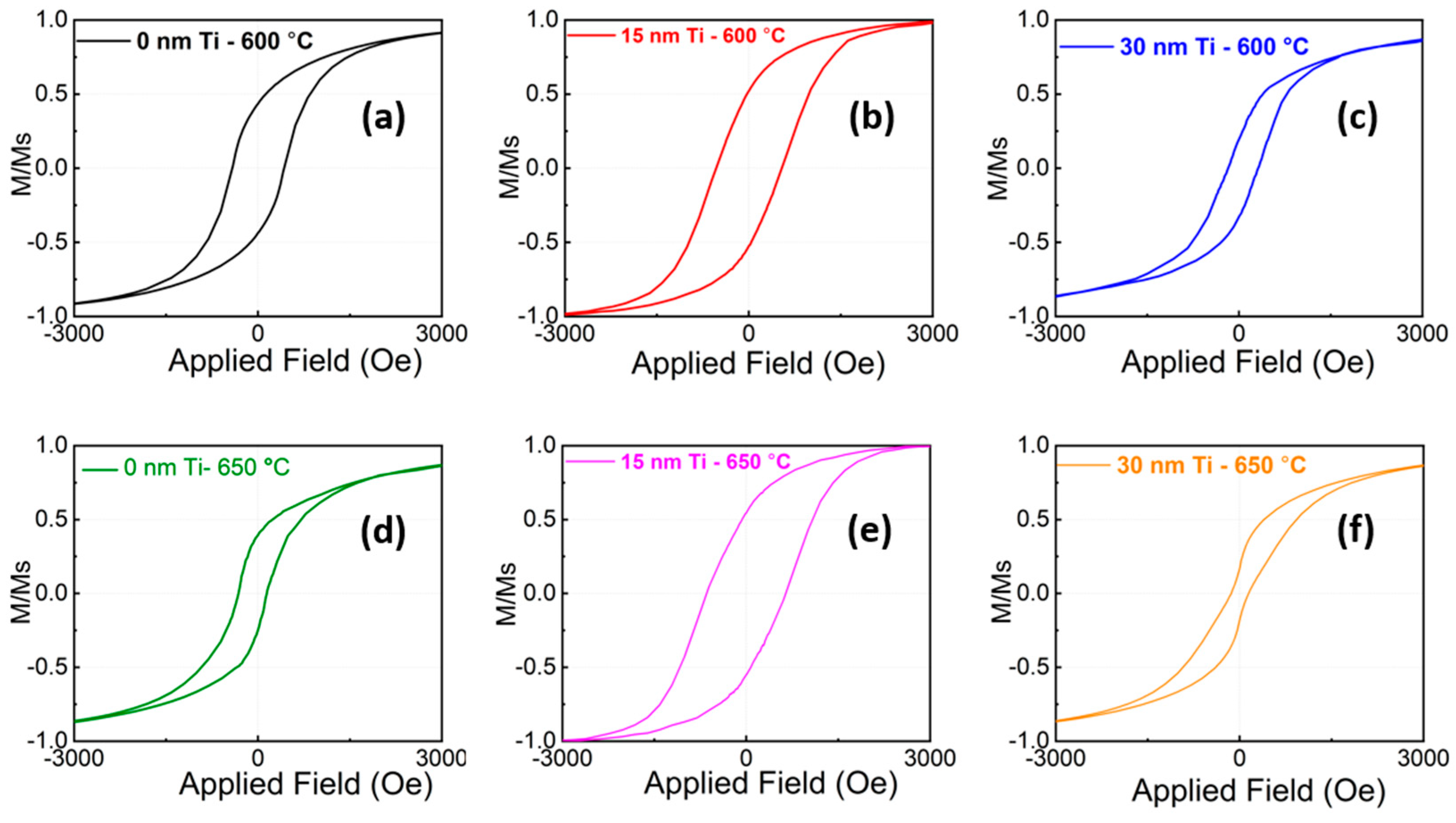

Magnetic data of Nd-Fe-B thin films were measured using a VSM for samples annealed at different temperatures and fabricated with different thicknesses of the Ti buffer layer (

Figure 3). The VSM data for samples annealed in situ at 600°C and 650°C indicate that those with a 15 nm Ti buffer layer exhibit noticeable magnetic remanence and a relatively large coercivity field. All the samples were measured with the magnetic field applied in the plane and the data indicating an in-plane magnetic easy axis. In the single-layer Nd-Fe-B thin film, the coercivity for the sample annealed at 650 °C and with a 15 nm Ti buffer layer is the highest among samples which is very consistent with XRD data.

Figure 3c,f show if a thick Ti buffer layer is annealed in situ at a high temperature it can cause diffusion between layers and diffusion may cause FM grains separated by Ti grains and the magnetic coupling could happen between those FM grains and results in a low coercivity/remanence.

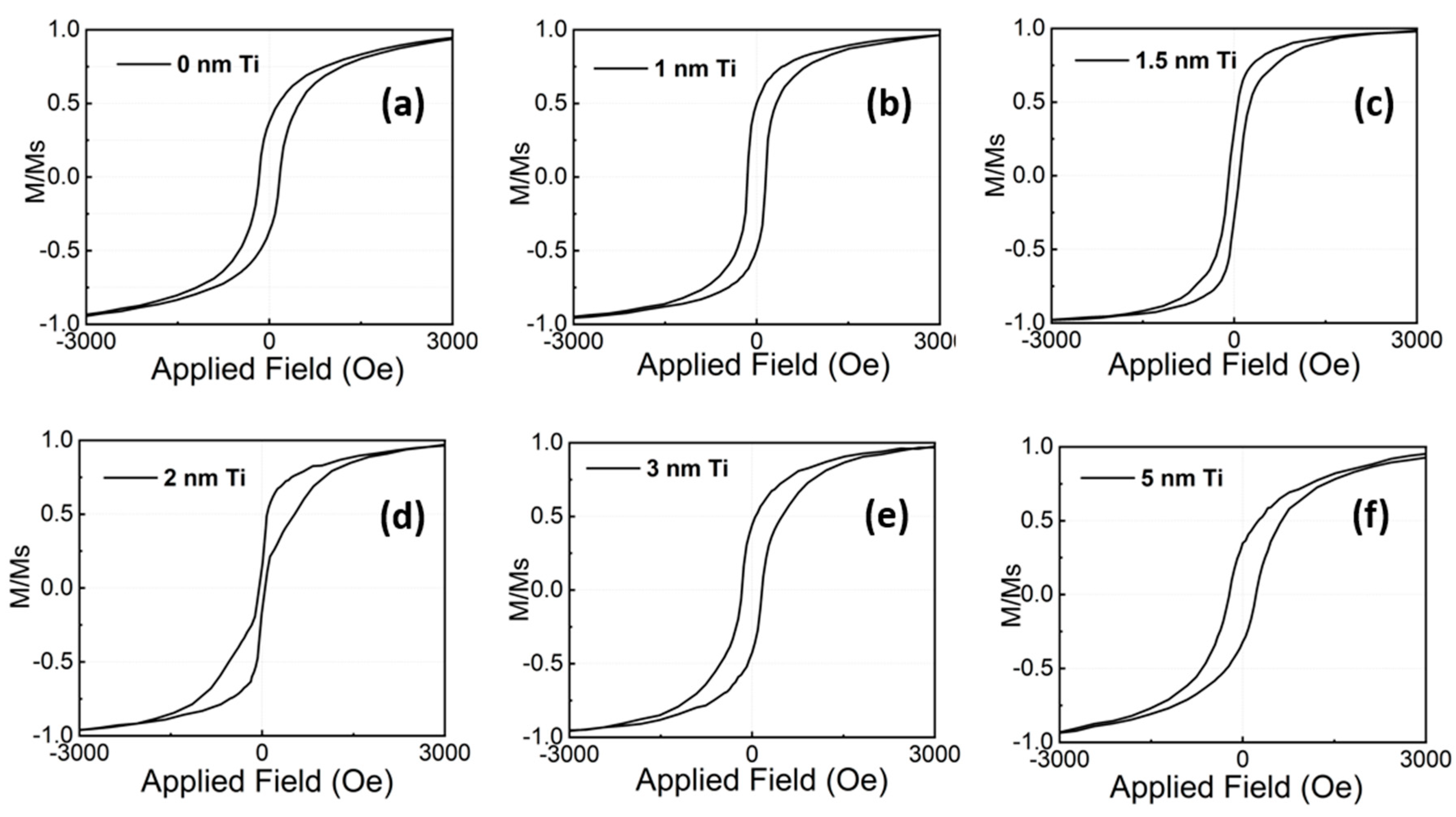

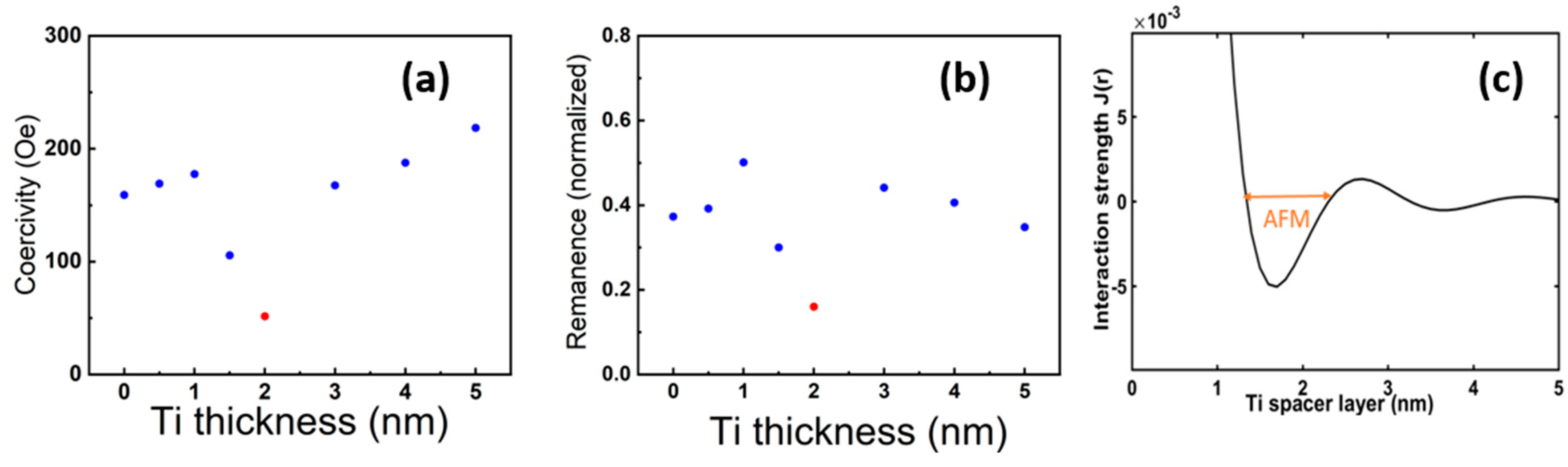

The magnetic properties of the multilayer films are very sensitive to the thickness of the spacer layer Ti. The VSM data is shown in

Figure 4 for [Si/15 nm Ti / Nd-Fe-B (300 nm)/ Ti (x nm)/ Fe (270 nm)/ Ti (20 nm)] thin films with various Ti spacer layer thickness.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the hysteresis loops have a strong dependence upon the thickness of the Ti layer. At 0 to 1 nm thicknesses, both Fe and Nd-Fe-B layers switch at the same field and the two layers are strongly FM coupled. As the thickness of the Ti layer goes to 1.5 nm, Fe, the magnetically soft layer, and Nd-Fe-B, the magnetically hard layer, switch at a relatively smaller field, indicating a weak AFM coupling. Here a kink as a sign of weak AFM coupling was noticed. For 2 nm Ti thickness, the magnetic hysteresis loop exhibits a stepwise switching field, and it corresponds to antiparallel alignment, a harsh kink in the hysteresis loop indicating a strong AFM coupling between soft and hard thin film. The 2 nm spacer layer is in the range of values predicted by the RKKY exchange coupling theoretical calculation. When the thickness of the spacer layer was more than 2 nm, FM layers coupled ferromagnetically again due to the periodic oscillation of RKKY interaction. The kink was mild when the Ti spacer layer thickness was 3 nm and smoother when the Ti thickness increased to 5 nm.

Figure 5 a,b show the remanence and coercivity of multilayer thin films as a function of Ti spacer layer thickness. The coercivity of the multilayer films with a spacer layer from 0.5 nm to 5 nm was between 51.5 Oe, corresponding to the sample with a 2 nm spacer layer, and 218 Oe, corresponding to the sample with a 5 nm spacer layer. This coercivity field range is much smaller than 700 Oe, corresponding to the single-layer film made on a 15 nm spacer layer and annealed in situ at 650 ◦C. This observation emphasizes strong magnetic coupling between multilayer samples has occurred. For the film made with a 5 nm spacer layer since the Fe moment is decoupled from the Nd-Fe-B layer and rotates easier in the presence of the external magnetic field, so Fe layer did not completely interact with the Nd-Fe-B layer and did not lead to a rotation of the moments in the NdFeB layer, so the coercivity of the film was larger relatively due to its most dependence to Nd-Fe-B layer. RKKY model considers that localized magnetic moments interact mediated by a conducting electron. Dynamic calculations between localized magnetic moments of the Ti spacer layer are shown in

Figure 5c, indicating that the maximum AFM interaction strength occurs when the thickness of the spacer layer is around 2 nm, which is verified experimentally [

41].

Moreover, although these results were obtained for a simplified model where local spins were considered, it perfectly agrees with RKKY interaction strength for 2D and 3D systems and thin films, which predicts a ferroelectric interaction would result when the thickness of the spacer layer is between 1 nm to 2 nm [

42]. Our calculation results, shown in

Figure 5c, indicate for the multilayered structure we used experimentally the maximum AFM interaction occurs when the thickness of the Ti spacer layer is between 1.3 to 2.2 nm.

4. Conclusions

In this study, an engineered multi-layered thin film with AFM ordering between multilayers could potentially lead to a net spin moment with negligible magnetization. The magnetization of the FM layers, separated by spacer layers, is indirectly coupled by electrons in the spacer layer based on RKKY theory. The crystalline properties of the structure are characterized using XRD, and the magnetic properties are studied using a VSM. The data indicates that when the thickness of the spacer layer is 2 nm, the magnetic coupling switches from FM coupling to AFM coupling, which agrees with simulations and other experimental works [

41]. Magnetic measurements along the easy axis direction indicate that when the thickness of the Ti spacer layer was 2 nm a kink was evidenced in the hysteresis loop, implying an AFM coupling between soft and hard magnetic phases of Fe and Nd-Fe-B thin films.

Supplementary Materials

The calculations of thicknesses of soft and hard FM layers in the multilayered structure to achieve a zero net magnetization and uncompensated pure spin is provided in the supplementary file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.; and R.C.; methodology, R.D.; and R.C.; software, S.Y.; and J.P.; formal analysis, S.Y..; A.M.; R.C.; R.D.; and T.B.; investigation, S.Y.; and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y; writing—review and editing, S.Y.; R.C; and A.M.; visualization, S.Y.; J.P.; A.M.; R.C.; supervision, R.C.; and R.D.; funding acquisition, R.D.; and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, grant number 1607360.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Betancourt, I.; Davies, H. A. Exchange coupled nanocomposite hard magnetic alloys. Materials Science and Technology 2010, 26, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ortega, A.; Estrader, M.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Roca, A. G.; Nogués, J. Applications of exchange coupled bi-magnetic hard/soft and soft/hard magnetic core/shell nanoparticles. Physics Reports 2015, 553, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ortega, A.; Estrader, M.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Estradé, S.; Golosovsky, I. V.; Dumas, R. K.; Keavney, D. J.; Vasilakaki, M.; Trohidou, K. N.; Sort, J.; Peiró, F.; Suriñach, S.; Baró, M. D.; Nogués, J. Strongly exchange coupled inverse ferrimagnetic soft/hard, MNXFE3−XO4/FEXMN3−XO4, core/shell heterostructured nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, X.-H.; Cui, W.-B.; Gong, W.-J.; Zhang, Z.-D. Exchange couplings in magnetic films. Chinese Physics B 2013, 22, 027104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, G. C. P.; Chagas, E. F.; Pereira, R.; Prado, R. J.; Terezo, A. J.; Alzamora, M.; Baggio-Saitovitch, E. Exchange coupling behavior in bimagnetic COFE2O4/COFE2 nanocomposite. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2012, 324, 2711–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, F.; Kameli, P.; Salamati, H.; Esmaeily, A. S. Tuning the exchange coupling in pulse laser deposited cobalt ferrite thin films by hydrogen reduction. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2019, 484, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, A.; Torkian, S.; Ghasemi, A.; Tavoosi, M.; Gordani, G. R. Magnetic properties improvement through exchange-coupling in hard/soft SRFE12O19/CO nanocomposite. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 2463–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, S.; Moradabadi, A.; Gorji, S.; Fawey, M. H.; Hildebrandt, E.; Radulov, I.; Wang, D.; Zhang, H.; Kübel, C.; Alff, L. Correlation of interface structure with magnetic exchange in a hard/soft magnetic model nanostructure. Physical Review Applied 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usarov, U. T.; Shakarov, K. O. Semi-empirical study of implicit exchange interaction in rare tarth metal-weakly magnetic metal system. Theoretical & Applied Science 2020, 81, 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Singh, A.; Sarkar, S.; Peter, S. C. Diversity in crystal structure and physical properties of RETX3 (re – rare earth, t – transition metal, X – main group element) intermetallics. The Chemical Record 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, D.; Chatterjee, J.; Jang, H.; Bokor, J. Analysis of ultrafast magnetization switching dynamics in exchange-coupled ferromagnet–ferrimagnet heterostructures. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2023, 574, 170680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Baldauf, T.; Mattauch, S.; Paul, N.; Paul, A. Topologically stable helices in exchange coupled rare-earth/rare-earth multilayer with superspin-glass like ordering. Communications Physics 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, A. K.; Igoshev, P. A.; Irkhin, V. Y. Incommensurate magnetic order in rare earth and transition metal compounds with local moments. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2021, 33, 375802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Pang, C. M.; Wang, X. M.; Yuan, C. C. The role of rare earth elements in tailorable thermal and magnetocaloric properties of re-co-al (re = gd, tb, and Dy) Metallic Glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2023, 600, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebs, M.; Fähnle, M. On the mechanism of the intersublattice exchange couplings in rare-earth-transition-metal intermetallics. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1993, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, N. H.; Hien, T. D.; Brommer, P. E.; Franse, J. J. M. The magnetic behaviour of rare-earth—transition metal compounds. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1992, 104–107, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.; Hussain, A.; Zafar, M.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, M. I.; Masood, M. K.; Majid, A. Ferromagnetism in Gan doped with transition metals and rare-earth elements: A Review. Chinese Journal of Physics 2018, 56, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledbetter, M. P.; Romalis, M. V.; Kimball, D. F. Constraints on short-range spin-dependent interactions from scalar spin-spin coupling in deuterated molecular hydrogen. Physical Review Letters 2013, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrescu, B. A.; Mocioiu, I. Spin-dependent macroscopic forces from New Particle Exchange. Journal of High Energy Physics 2006, 2006, 005–005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.-H.; Ristoff, N.; Smits, J.; Jackson, N.; Kim, Y. J.; Savukov, I.; Acosta, V. M. Proposal for the search for new spin interactions at the micrometer scale using diamond quantum sensors. Physical Review Research 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescini, N.; Carugno, G.; Falferi, P.; Ortolan, A.; Ruoso, G.; Speake, C. C. Search of spin-dependent fifth forces with precision magnetometry. Physical Review D 2022, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, M. P.; Syzdykova, A. B.; Abrikosov, I. A. Temperature-dependent lattice dynamics of antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic phases of FeRh. Physical Review B 2020, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Decker, M. M.; Meier, T. N.; Chen, X.; Song, C.; Grünbaum, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Back, C. H. Spin pumping during the antiferromagnetic–ferromagnetic phase transition of iron–rhodium. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Medapalli, R.; Mentink, J. H.; Mikhaylovskiy, R. V.; Blank, T. G.; Patel, S. K.; Zvezdin, A. K.; Rasing, Th.; Fullerton, E. E.; Kimel, A. V. Ultrafast kinetics of the antiferromagnetic-ferromagnetic phase transition in FeRh. Nature Communications 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, H.; Crabtree, G. W.; Joss, W.; Hulliger, F. Fermi surface study of CeSb in the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1985, 52, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.; Sort, J.; Rodmacq, B.; Auffret, S.; Dieny, B. Large anomalous enhancement of Perpendicular exchange bias by introduction of a nonmagnetic spacer between the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic layers. Applied Physics Letters 2003, 83, 3537–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomonay, H. V.; Loktev, V. M. Spin transfer and current-induced switching in antiferromagnets. Physical Review B 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S. G.; Rizwan, S.; Qin, Q. H.; Han, X. F. Magnetoresistance effect in antiferromagnet/nonmagnet/antiferromagnet multilayers. Applied Physics Letters 2009, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, M.; Bose, E.; Pal, S. Impact of non-magnetic zn2+ doping on the structural, magnetic and magnetocaloric properties of Nd0.5Ca0.5Mn1-Zn O3 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.10) compounds. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2023, 575, 170752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekawa, H.; Shen, J.; Toyoki, K.; Nakatani, R.; Shiratsuchi, Y. Gate-induced switching of perpendicular exchange bias with very low coercivity in Pt/CO/IR/CR2O3/PT epitaxial film. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri-Amin, H.; Hirosawa, S.; Hono, K. Advances in nd-fe-B based permanent magnets. Handbook of Magnetic Materials 2018, 269–372. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, Y. Recent development of Nd–Fe–B sintered magnets and their applications. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2006, 303, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, S. V.; Bartashevich, M. I.; Pushkarsky, V. I.; Maltsev, V. N.; Pamyatnykh, L. A.; Tarasov, E. N.; Kudrevatykh, N. V.; Goto, T. Law of approach to saturation in highly anisotropic ferromagnets application to ndfeb melt-spun ribbons. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 1997, 260, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, N.; Gao, X. Magnetohydrodynamic electrochemistry in the field of Nd−Fe−B magnets. theory, experiment, and application in self-powered flow delivery systems. Analytical Chemistry 2001, 73, 3981–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, T.; Kamegawa, A.; Aoyagi, E.; Hayasaka, Y.; Fujimori, H. Magnetic properties and structure of Nd-Fe-B thin films with Cr and ti underlayers. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1998, 177–181, 911–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N. M.; Woodcock, T. G.; Sepehri-Amin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kennedy, H.; Givord, D.; Hono, K.; Gutfleisch, O. High-coercivity nd–fe–B thick films without heavy rare earth additions. Acta Materialia 2013, 61, 4920–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C. Y.; Takahashi, Y. K.; Hono, K. Fabrication and characterization of highly textured Nd–fe–B thin film with a nanosized columnar grain structure. Journal of Applied Physics 2010, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W. B.; Takahashi, Y. K.; Hono, K. Microstructure optimization to achieve high coercivity in anisotropic Nd–fe–b thin films. Acta Materialia 2011, 59, 7768–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Li, Y. F.; Hong, F.; You, C. Y. Fabrication of high coercive Nd–Fe–B based thin films through annealing nd–fe–B/nd–fe multilayers. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2015, 477, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J. P.; Yazdani, S.; Highland, W.; Cheng, R. A high sensitivity custom-built vibrating sample magnetometer. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W. B.; Sepehri-Amin, H.; Takahashi, Y. K.; Hono, K. Hard magnetic properties of spacer-layer-tuned NDFEB/ta/fe nanocomposite films. Acta Materialia 2015, 84, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, T. A comparison of the RKKY interaction for the 2D and 3D systems and thin films. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2007, 310, 1651–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).