Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

21 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model

3.2. Survey Design and Data

4. Results

5. Conclusions

References

- Gao, Z.; Schroeder, T. C. Effects of Label Information on Consumer Willingness-to-Pay for Food Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Louviere, J. J.; Burke, P. F. Modeling the Effects of Including/Excluding Attributes in Choice Experiments on Systematic and Random Components. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swait, J.; Louviere, J. The Role of the Scale Parameter in the Estimation and Comparison of Multinomial Logit Models. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30(3), 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Boyer, T. A.; Palma, M.; Ghimire, M. Economic Impact of Drought- and Shade-Tolerant Bermudagrass Varieties. HortTechnology 2018, 28, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, M.; Boyer, T. A.; Chung, C.; Moss, J. Q. Consumers’ Shares of Preferences for Turfgrass Attributes Using a Discrete Choice Experiment and the Best–Worst Method. HortScience 2016, 51, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, M.; Boyer, T. A.; Chung, C. Heterogeneity in Urban Consumer Preferences for Turfgrass Attributes. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugie, K.; Yue, C.; Watkins, E. Consumer Preferences for Low-Input Turfgrasses: A Conjoint Analysis. HortScience 2012, 47, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Hugie, K.; Watkins, E. Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Low-Input Turfgrasses on Residential Lawns? Evidence from Choice Experiments. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Wang, J.; Watkins, E.; Bonos, S. A.; Nelson, K. C.; Murphy, J. A.; Meyer, W. A.; Horgan, B. P. Heterogeneous Consumer Preferences for Turfgrass Attributes in the United States and Canada. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. Agroeconomie 2017, 65, 347–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, D. S.; Klein, R. A.; Clark, M. P. USE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF MUNICIPAL WATER RESTRICTIONS DURING DROUGHT IN COLORADO. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2004, 40, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozan, L. A.; Alsharif, K. A. The Effectiveness of Water Irrigation Policies for Residential Turfgrass. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichman, C. J.; Taylor, L. O.; Von Haefen, R. H. Conservation Policies: Who Responds to Price and Who Responds to Prescription? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 79, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meas, T.; Hu, W.; Batte, M. T.; Woods, T. A.; Ernst, S. Substitutes or Complements? Consumer Preference for Local and Organic Food Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 1044–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rezende, C. E.; Kahn, J. R.; Passareli, L.; Vásquez, W. F. An Economic Valuation of Mangrove Restoration in Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, S. T. M.; Ando, A. W. Valuing Grassland Restoration: Proximity to Substitutes and Trade-Offs among Conservation Attributes. Land Econ. 2014, 90, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilava, D.; Foster, K. Quality Certification vs. Product Traceability: Consumer Preferences for Informational Attributes of Pork in Georgia. Food Policy 2009, 34, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, I.; Nunes, L. C.; Madureira, L.; Fontes, M. A.; Santos, J. L. Beef Credence Attributes: Implications of Substitution Effects on Consumers’ WTP. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 65, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Rose, J.; Crase, L. Does Anybody like Water Restrictions? Some Observations in Australian Urban Communities. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2012, 56, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Thiene, M.; Train, K. Utility in Willingness to Pay Space: A Tool to Address Confounding Random Scale Effects in Destination Choice to the Alps. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Sun, S.; Penn, J.; Qing, P. Dummy and Effects Coding Variables in Discrete Choice Analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 104, 1770–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. N.; Shearman, R. C. NTEP Turfgrass Evaluation Guidelines, NTEP Turfgrass Evaluation Workshop, Beltsville, Maryland, 1998; 1-5. https://www.ntep.org/pdf/ratings.pdf.

- Fessler, A.; Thorhauge, M.; Mabit, S.; Haustein, S. A Public Transport-Based Crowdshipping Concept as a Sustainable Last-Mile Solution: Assessing User Preferences with a Stated Choice Experiment. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2022, 158, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.; Lusk, J. L. RELEASING THE TRAP: A METHOD TO REDUCE INATTENTION BIAS IN SURVEY DATA WITH APPLICATION TO U.S. BEER TAXES. Econ. Inq. 2019, 57, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, K.; Chung, C.; Boyer, T. A.; Palma, M. Does Change in Respondents’ Attention Affect Willingness to Accept Estimates from Choice Experiments? Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 3279–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Gilbride, T. J.; Campbell, D.; Hensher, D. A. Modelling Attribute Non-Attendance in Choice Experiments for Rural Landscape Valuation. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2009, 36, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, E.; Adjenughwure, K.; De Bruyn, M.; Cats, O.; Warffemius, P. Does Conducting Activities While Traveling Reduce the Value of Time? Evidence from a within-Subjects Choice Experiment. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.; Palma, D. Apollo: A Flexible, Powerful and Customisable Freeware Package for Choice Model Estimation and Application. Journal of Choice Modelling 2019, 32, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.; Hess, S.; Patruni, B.; Potoglou, D.; Rohr, C. Using Ordered Attitudinal Indicators in a Latent Variable Choice Model: A Study of the Impact of Security on Rail Travel Behaviour. Transportation 2012, 39, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.; Spitz, G.; Bradley, M.; Coogan, M. Analysis of Mode Choice for Intercity Travel: Application of a Hybrid Choice Model to Two Distinct US Corridors. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2018, 116, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

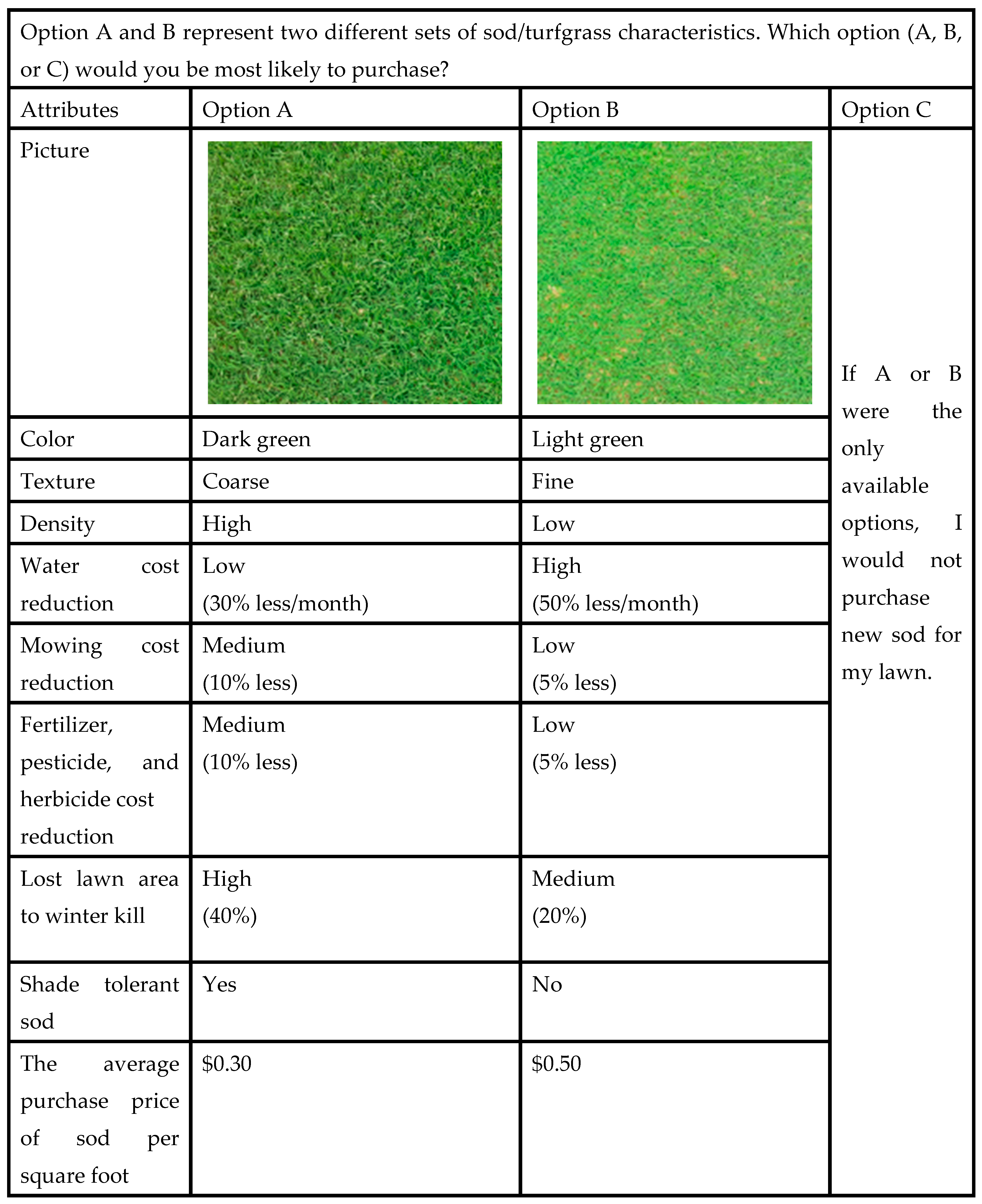

| Attributes | Attribute levels |

|---|---|

| Water cost reduction | Low (30% less/month) Medium (40% less/month) High (50% less/month) |

| Mowing cost reduction | Low (5% less) Medium (10% less) High (15% less) |

| Fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | Low (5% less) Medium (10% less) High (15% less) |

| Lost lawn area to winter kill | Low (0%) Medium (20%) High (40%) |

| Shade tolerance | No Yes |

| Color | Light green Dark green |

| Density | Low High |

| Texture | Fine Coarse |

| The purchase price of sod per square foot | $0.20, $0.30, $0.40, $0.50 |

| Variables | Mean/Proportion | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.56 | 17.90 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.49 | - |

| Female | 0.51 | - |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 0.01 | - |

| High school graduate | 0.26 | - |

| Undergraduate degree | 0.43 | - |

| Graduate degree | 0.31 | - |

| Income | ||

| <$25,000 | 0.12 | - |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 0.21 | - |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 0.21 | - |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 0.14 | - |

| $100,000-$124,999 | 0.08 | - |

| $125,000-$149,999 | 0.09 | - |

| $150,000-$174,999 | 0.06 | - |

| $175,000-$199,999 | 0.04 | - |

| >$200,000 | 0.06 | - |

| Without interaction terms | With interaction terms |

|||

| Attributes | Color (light green) | Density (low) | Texture (fine) | |

|

Direct effect | ||||

| ASC | -1.2968*** (0.1457) |

-1.2721*** (0.1726) |

-1.3211*** (0.1045) |

-1.3044*** (0.1140) |

| 40% water cost reduction | 0.0713*** (0.0168) |

0.0517*** (0.0241) |

0.0790*** (0.0229) |

0.0765*** (0.0219) |

| 50% water cost reduction | 0.1228*** (0.0223) |

0.1139*** (0.0314) |

0.1225*** (0.0314) |

0.1322*** (0.0270) |

| 10% mowing cost reduction | 0.0009 (0.0154) |

0.0131 (0.0190) |

0.0037 (0.0316) |

-0.0015 (0.0168) |

| 15% mowing cost reduction | 0.0261* (0.0144) |

0.0366* (0.0165) |

0.0202* (0.0159) |

0.0183 (0.0154) |

| 10% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | 0.0016 (0.0181) |

0.0027 (0.0162) |

-0.0030 (0.0221) |

0.0117 (0.0239) |

| 15% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | 0.0226 (0.0189) |

0.0264** (0.0191) |

0.0430** (0.0242) |

0.0363** (0.0199) |

| 20% lost lawn area to winter kill | 0.1290*** (0.0212) |

0.1211*** (0.0247) |

0.1251*** (0.0425) |

0.1174*** (0.0241) |

| 0% lost lawn area to winter kill | 0.1843*** (0.0299) |

0.1741*** (0.0323) |

0.1701*** (0.0447) |

0.1696*** (0.0330) |

| Shade tolerance | 0.1129*** (0.0175) |

0.1277*** (0.0216) |

0.1366*** (0.0167) |

0.1264*** (0.0213) |

| Light green | -0.1829*** (0.0293) |

-0.1785*** (0.0252) |

-0.1506*** (0.0192) |

-0.1869*** (0.0403) |

| Low density | -0.1660*** (0.0326) |

-0.1607*** (0.0216) |

-0.1563*** (0.0242) |

-0.1716*** (0.0238) |

| Fine texture | -0.0080 (0.0167) |

-0.0053 (0.0190) |

-0.0065 (0.0337) |

0.0067 (0.0187) |

| Indirect effect (from interaction terms with aesthetic attributes) | ||||

| 40% water cost reduction | - | 0.0014 (0.0301) |

0.0228 (0.0261) |

-0.0150 (0.0301) |

| 50% water cost reduction | - | -0.0214 (0.0314) |

0.0414 (0.0305) |

0.0190 (0.0281) |

| 10% mowing cost reduction | - | 0.0016 (0.0325) |

-0.0069 (0.0644) |

-0.0244 (0.0258) |

| 15% mowing cost reduction | - | 0.0441 (0.0355) |

0.0217 (0.0285) |

0.0165 (0.0266) |

| 10% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | - | -0.0261 (0.0320) |

-0.0086 (0.0364) |

-0.0024 (0.0299) |

| 15% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | - | -0.0209 (0.0347) |

-0.0010 (0.0212) |

0.0050 (0.0250) |

| 20% lost lawn area to winter kill | - | 0.0043 (0.0283) |

-0.0236 (0.0277) |

-0.0005 (0.0281) |

| 0% lost lawn area to winter kill | - | -0.0238 (0.0280) |

-0.0261 (0.0335) |

-0.0181 (0.0281) |

| Shade tolerance | - | -0.0457 (0.0436) |

-0.0890*** (0.0275) |

0.0201 (0.0297) |

| Number of observations | 10,980 | 10,980 | 10,980 | 10,980 |

| Attributes | Color (light green) | Density (low) | Texture (fine) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40% water cost reduction | 0.0531 (0.0401) |

0.1018*** (0.0353) |

0.0614* (0.0364) |

| 50% water cost reduction | 0.0924** (0.0444) |

0.1639*** (0.0408) |

0.1512*** (0.0394) |

| 10% mowing cost reduction | 0.0146 (0.0390) |

-0.0032 (0.0637) |

-0.0259 (0.0309) |

| 15% mowing cost reduction | 0.0807** (0.0397) |

0.0418 (0.0319) |

0.0348 (0.0308) |

| 10% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | -0.0234 (0.0364) |

-0.0115 (0.0506) |

0.0093 (0.0377) |

| 15% fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | 0.0055 (0.0409) |

0.0421 (0.0379) |

0.0413** (0.0315) |

| 20% lost lawn area to winter kill | 0.1253*** (0.0360) |

0.1015** (0.0504) |

0.1168*** (0.0373) |

| 0% lost lawn area to winter kill | 0.1503*** (0.0405) |

0.1440*** (0.0511) |

0.1515*** (0.0438) |

| Shade tolerance | 0.0819* (0.0479) |

0.0477 (0.0314) |

0.1466*** (0.0362) |

| Without interaction terms | With interaction terms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color (light green) | Density (low) | Texture (fine) | ||||||

| Attributes | Relative importance (%) | Ranking | Relative importance (%) | Ranking | Relative importance (%) | Ranking | Relative importance (%) | Ranking |

| Water cost reduction | 19.37 | 3 | 19.75 | 2 | 46.98 | 1 | 33.79 | 2 |

| Mowing cost reduction | 5.43 | 4 | 17.24 | 4 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.00 | 4 |

| Fertilizer, pesticide, and herbicide cost reduction | 0.00 | 5 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.00 | 4 |

| Lost lawn area to winter kill | 51.72 | 1 | 45.50 | 1 | 42.58 | 2 | 38.99 | 1 |

| Shade tolerance | 23.47 | 2 | 17.51 | 3 | 10.43 | 3 | 27.22 | 3 |

| Policy scenario | Attribute | WTPbefore | WTPafter | T-test for comparing WTPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% water rate increase | 50% water cost reduction | 0.0912*** (0.0335) |

0.9267*** (0.1384) |

0.8356*** (0.1424) |

| 50% water rate increase | 50% water cost reduction | 0.0720* (0.0431) |

0.3326*** (0.1179) |

0.2606** (0.1255) |

| 100% water rate increase | 50% water cost reduction | 0.1800*** (0.0468) |

0.2128*** (0.0488) |

0.0328 (0.0676) |

| Restriction for the watering lawn: Even or odd days a week | 50% water cost reduction | 0.0811** (0.0323) |

0.0932*** (0.0305) |

0.0121 (0.0445) |

| Restriction for the watering lawn: Two days a week | 50% water cost reduction | 0.2495 (0.7274) |

0.2629*** (0.0400) |

0.0134 (0.7285) |

| Restriction for the watering lawn: One day a week | 50% water cost reduction | 0.2663*** (0.0614) |

0.4117** (0.1978) |

0.1454 (0.2071) |

| [1] | Many studies find that, among non-price policies, mandatory water restriction policies are more effective than voluntary water conservation policies [10,12]. Kenney et al. (2004) [10] show that once a week watering restriction decreases water consumption more than twice a week restriction. On the other hand, Ozan and Alsharif (2013) [11] find that water consumption decreases with the number of watering restriction, i.e., twice a week watering restriction is more effective than once a week restriction.

|

| [2] | Yue et al. (2012) [8] note that homeowners would prefer drought-tolerant plants under the water price increasing policy. However, the study does not estimate the effect of water-conservation policy on consumer preference for turfgrass attributes. |

| [3] | Subscripts, i, j, and t, are henceforth suppressed for the sake of notational simplicity. |

| [4] | In many studies using effect coding, the WTP from effect coding multiplied by 2 is typically considered the same as the WTP from the dummy coding due to the difference in base coding. However, Hu et al. (2022) [20] demonstrate that this interpretation is appropriate only when the attribute level is two. When the level of attribute is more than two, more general method such as equation (7) needs to be used for the interpretation of estimated WTPs from effect coding. |

| [5] | The survey (IRB-21-93) was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Oklahoma State University. |

| [6] | Fessler et al. (2022) [22] removed respondents who spent less than 4 minutes to complete the whole survey (including four choice tasks and demographic questions) and who showed questionable responses during choice experiments. Previous studies also used trap questions [23], eye-tracking [24], and attribute non-attendance (ANA) analysis [25] to address participants’ inattention problem. |

| [7] | Irrigation restriction policies typically include a combination of total irrigation hours a week, time of irrigation, and voluntary or mandatory participation. Since it is difficult to consider all these combinations in our experimental design, this study focuses on the frequency of outdoor watering. |

| [8] | We tried both the Halton draw method and the pseudo-Monte Carlo draw method and found that both methods yielded almost the same results. We here present results from the Halton draw method. |

| [9] | We also estimated the same water policy effects on the attribute of 40% water cost reduction and found similar results (the policy of 25% water rate increase effectively raised the WTP at the 1% level), but overall the policy effects were lower than the results from the attribute of 50% water cost reduction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).