Submitted:

14 December 2023

Posted:

15 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Reaction Scheme and Experimental Set Up

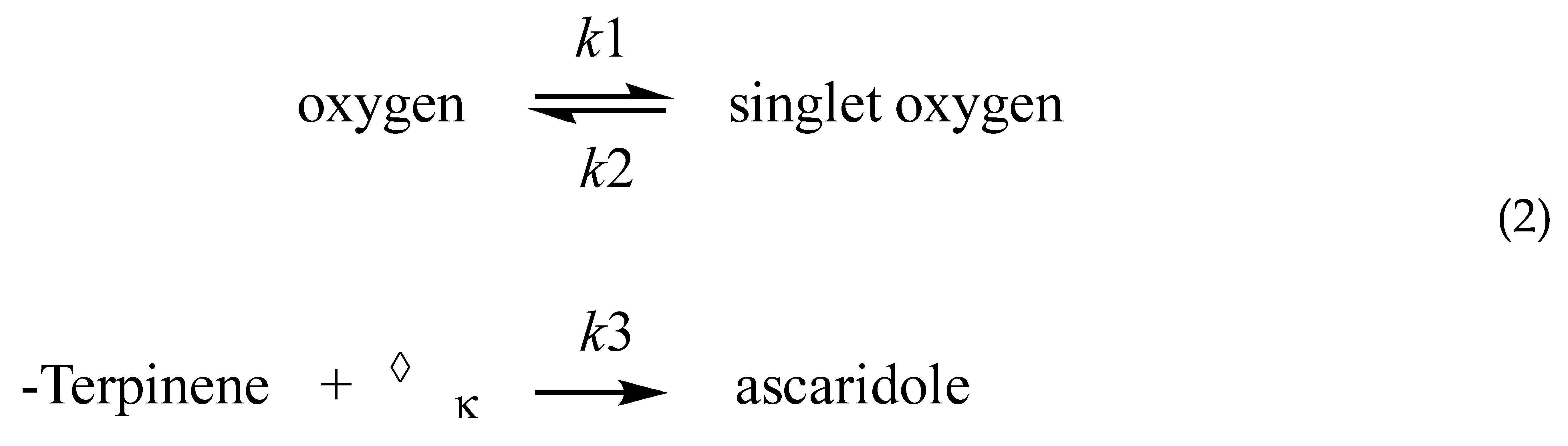

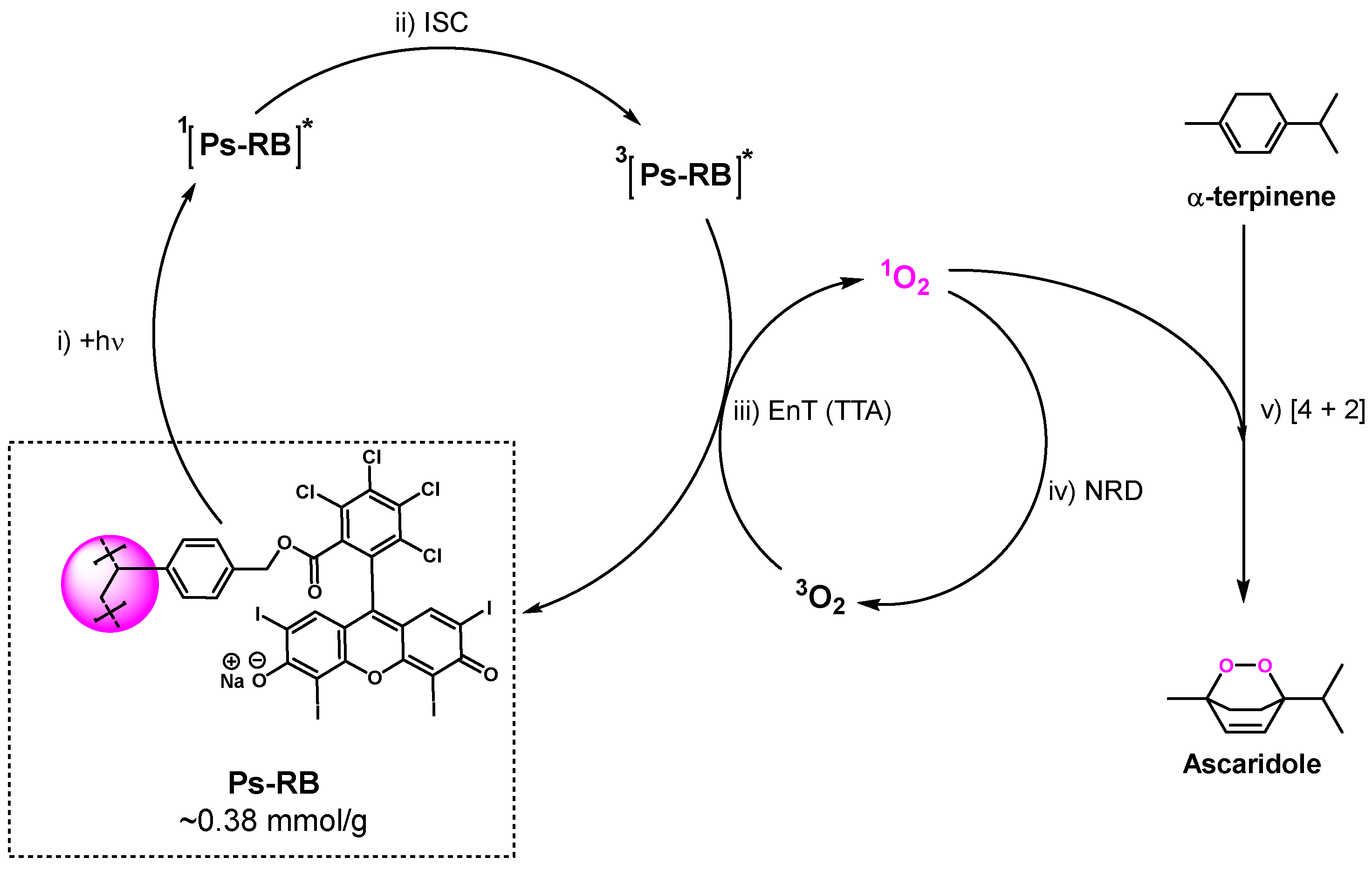

2.1. Reaction Scheme

2.2. Materials

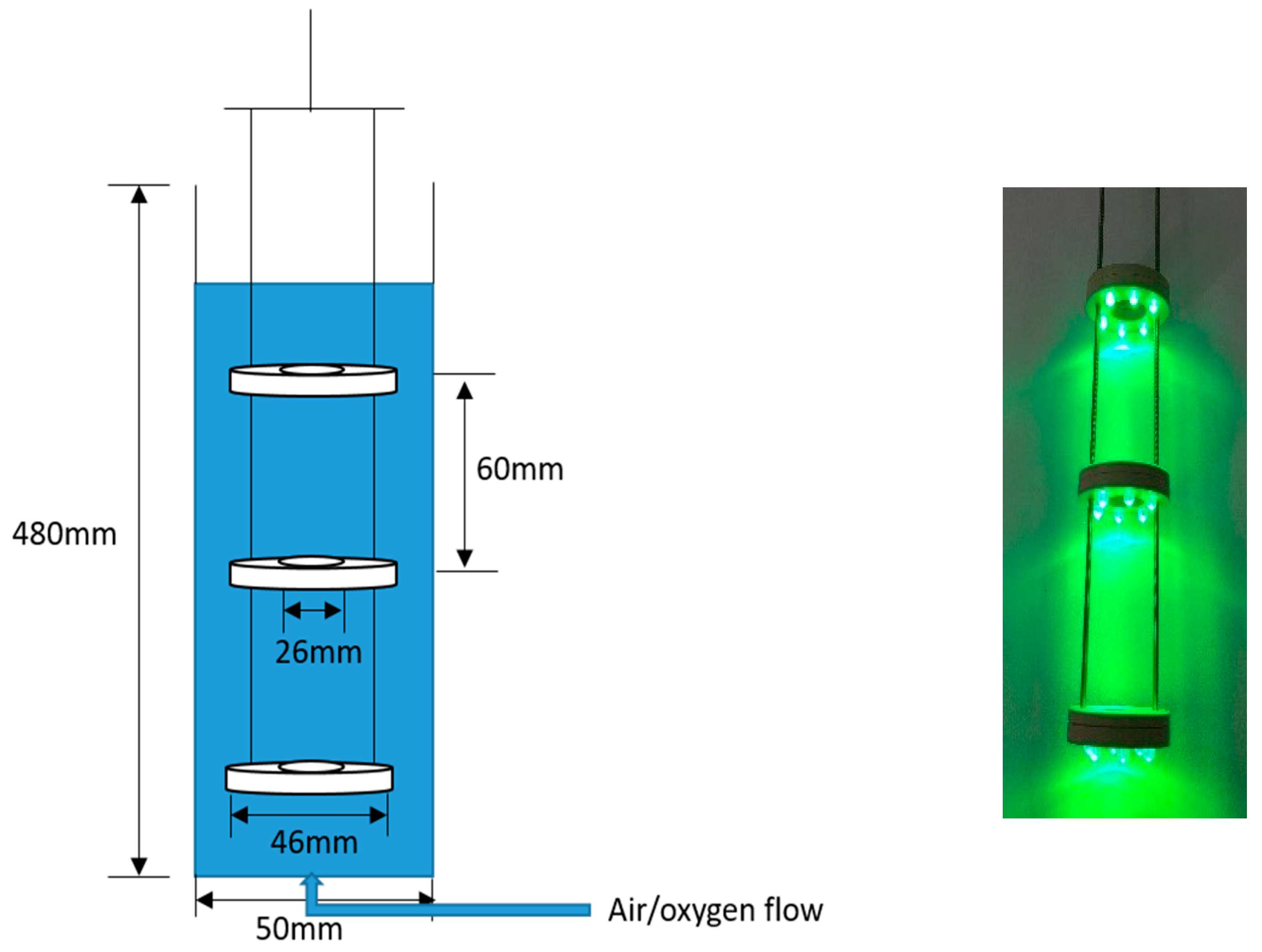

2.3. Reactor Setup

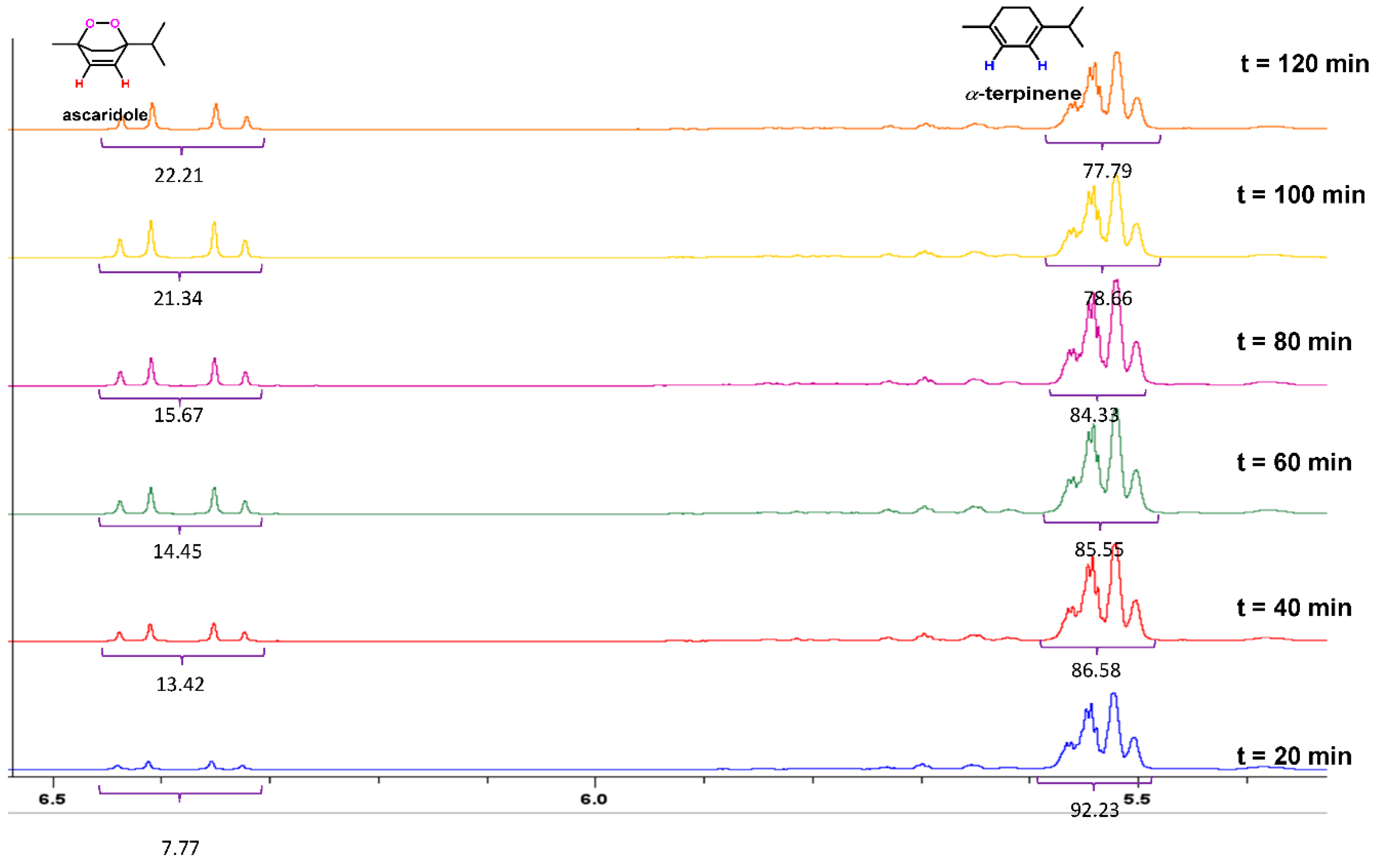

2.4. Analytic Method

- Each 2 mL sample containing CHCl3 + α-terpinene + ascaridole was injected to a dark vial to stop the reaction (reaction stops when light is off)

- The sample was placed into a round bottom flask and the solvent (CHCl3) removed under reduced pressure on a rotary evaporator (40°C, 365 mbar for ~5 minutes)

- The oily residue was dissolved in 0.5 mL of deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) and a 1H NMR was obtained (300 MHz Bruker AVIII spectrometer)

- Peaks in the region between 6.70 and 5.40 ppm were used to determine the conversion of α-terpinene and the appearance of ascaridole

3. Results and Discussion

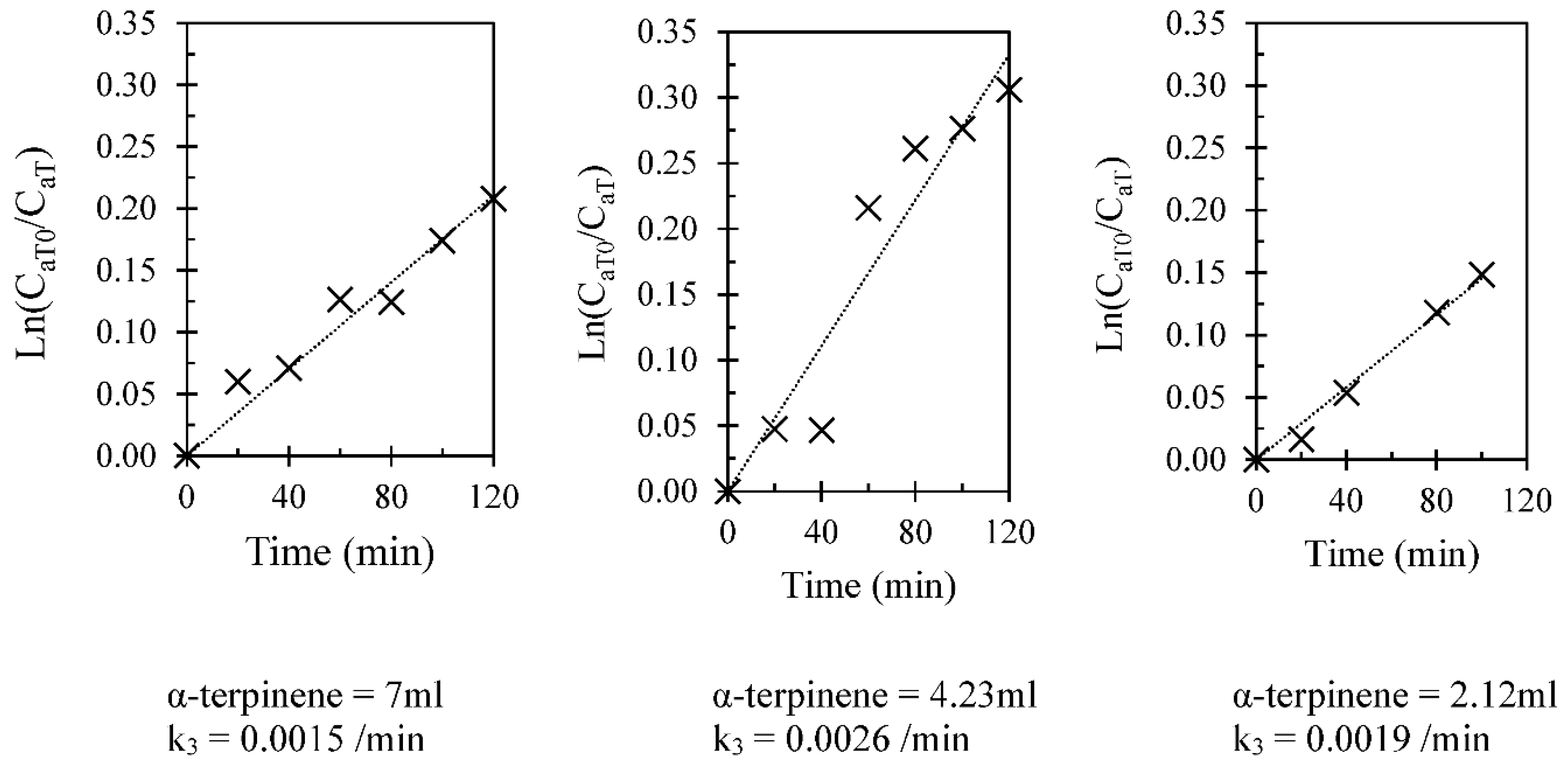

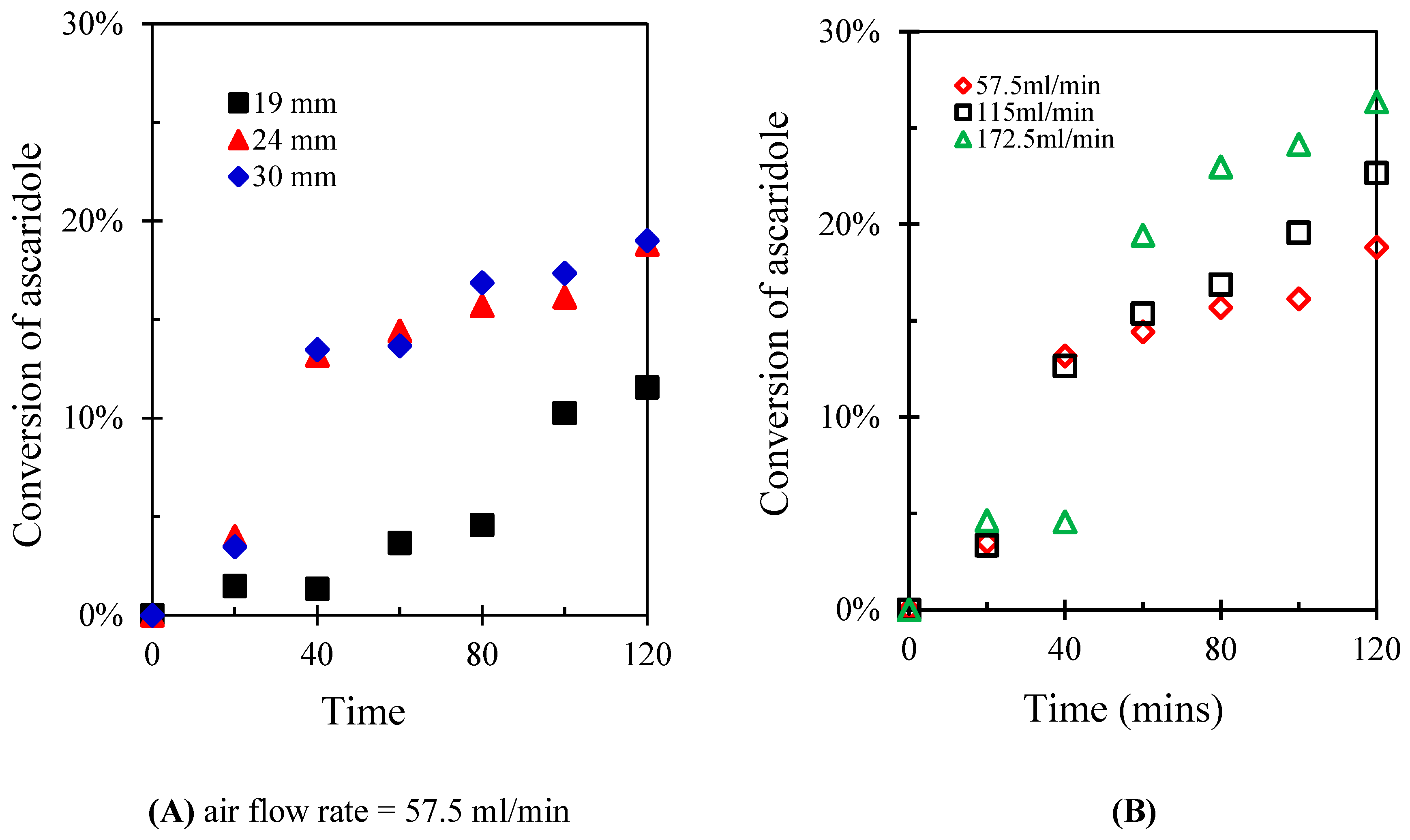

3.1. Kinetic Assessment

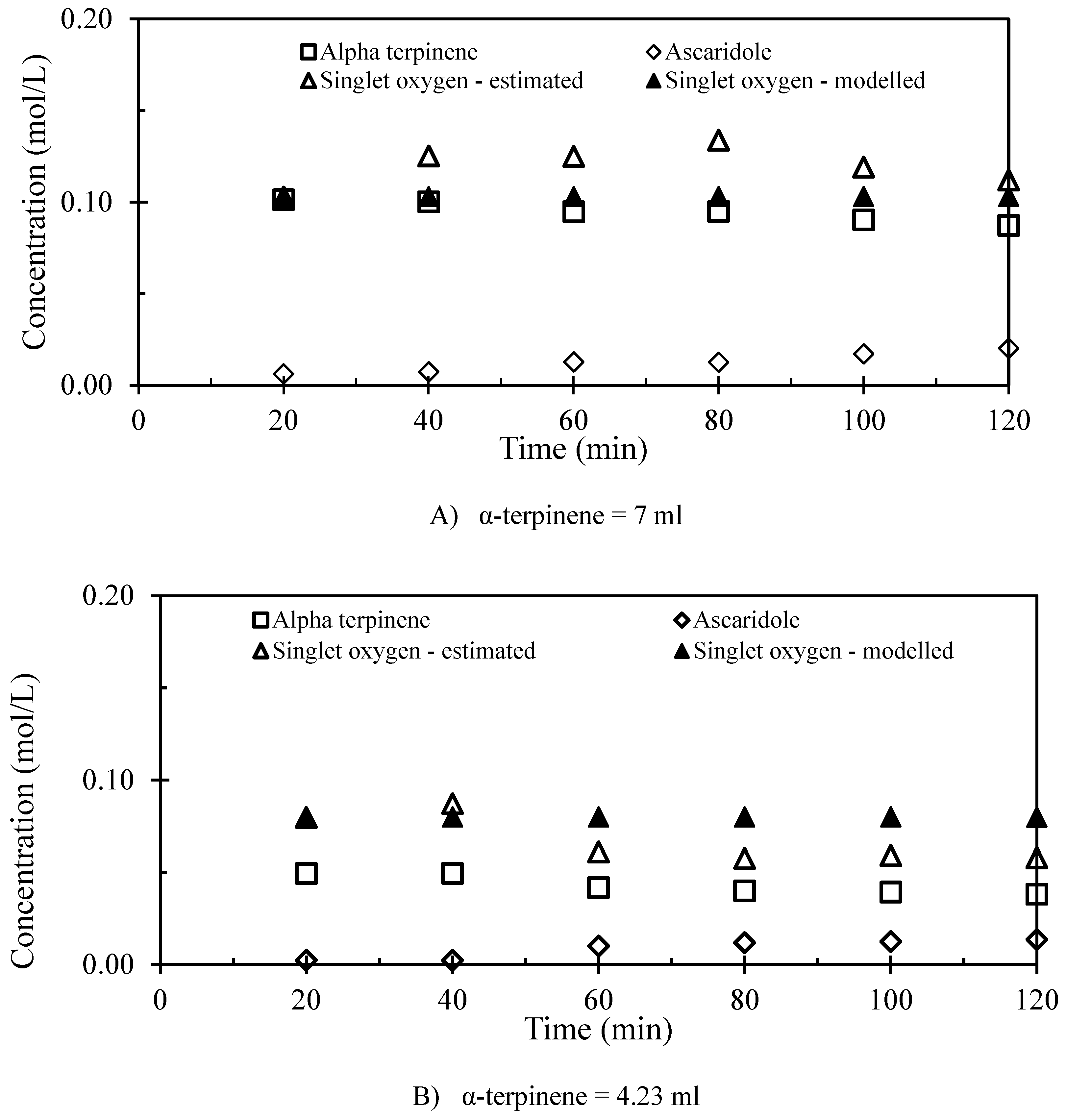

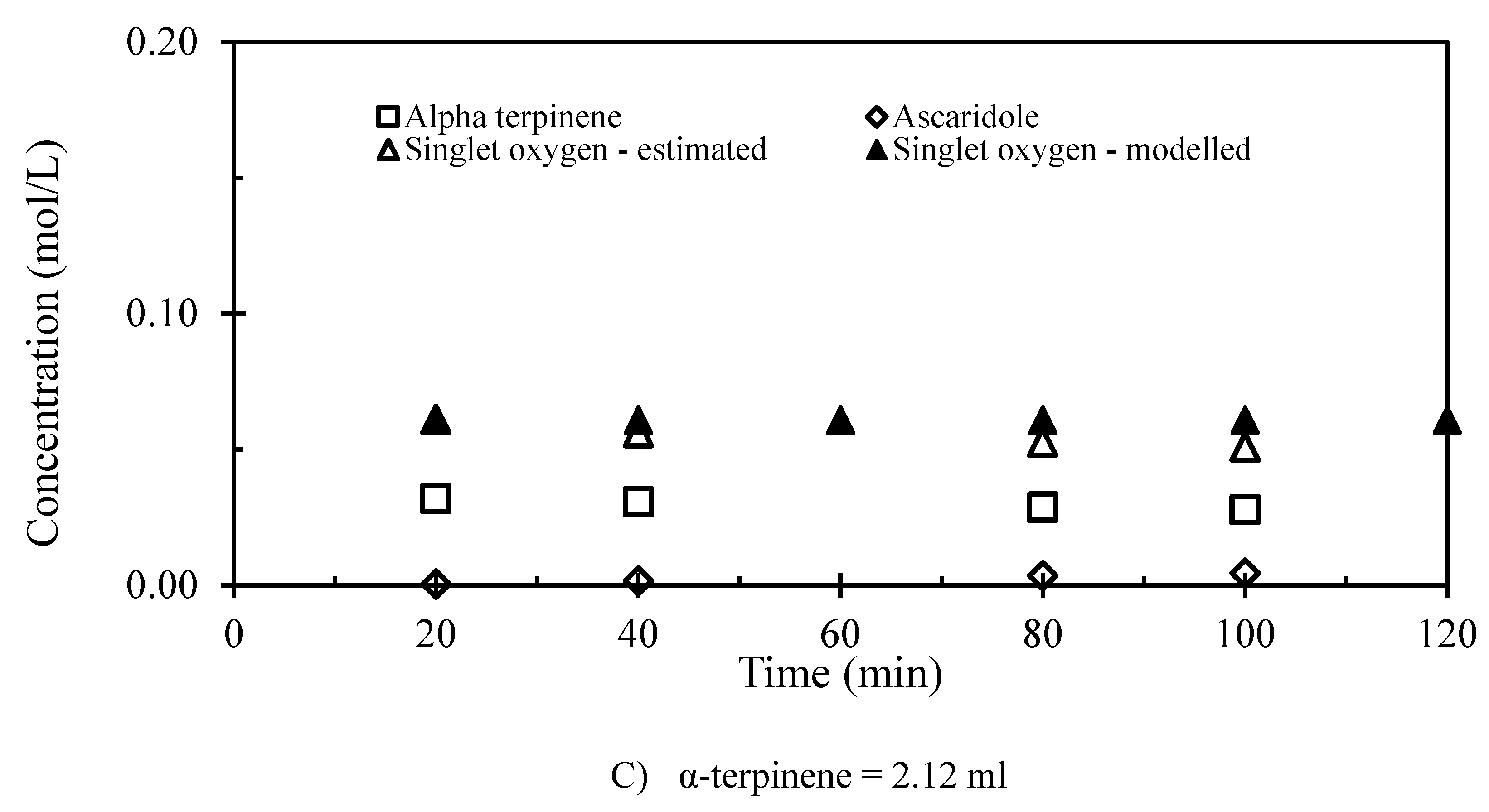

3.2. The 1st Step of the Reaction

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

Nomenclature

| Areaas | integrated NMR area of ascaridole |

| AreaαT | integrated NMR area of α-Terpinene |

| Cas | concentration of ascaridole (mol L-1) |

| CαT | concentration of α-Terpinene (mol L-1) |

| D | tube diameter (m) |

| f | oscillation frequency (Hz) |

| Reo | oscillatory Reynolds number |

| St | Strouhal number |

| xo | oscillatory center-to-peak amplitude (m) |

| ρ | density (kg m-3) |

References

- L. Buglioni, F. Raymenants, A. Slattery, S. D. A. Zondag, T. Noël, Chem Reviews 2022, 122, 2752-2906.

- aF. Ronzani, N. Costarramone, S. Blanc, A. K. Benabbou, M. L. Bechec, T. Pigot, M. Oelgemöller, S. Lacombe, Journal of Catalysis 2013, 303, 164-174; bM. S. Baptista, J. Cadet, P. D. Mascio, A. A. Ghogare, A. Greer, M. R. Hamblin, C. Lorente, S. C. Nunez, M. S. Ribeiro, A. H. Thomas, M. Vignoni, T. M. Yoshimura, 2017, 93, 912-919.

- aS. D. A. Zondag, D. Mazzarella, T. Noël, Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 2023, 14, 283-300; bE. Kayahan, M. Jacobs, L. Braeken, L. C. J. Thomassen, S. Kuhn, T. V. Gerven, M. Enis Leblebici, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2484–2504; cA. Chaudhuri, K. P. L. Kuijpers, R. B. J. Hendrix, P. Shivaprasad, J. A. Hacking, E. A. C. Emanuelsson, T. Noël, J. V. D. Schaaf, Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 400; dK. Donnelly, M. Baumann, J Flow Chem 2021, 11, 223–241; eD. S. Lee, Z. Amara, C. A. Clark, Z. Xu, B. Kakimpa, H. P. Morvan, T. J. Pickering, M. Poliakoff, M. W. George, Organic Process Research & Development 2017, 21, 1042-1050.

- J. M. Tobin, J. Liu, H. Hayes, M. Demleitner, D. Ellis, V. Arrighi, Z. Xu, F. Vilela, Polymer Chemistry 2016, 7, 6662-6670.

- O. Shvydkiv, K. Jähnisch, N. Steinfeldt, A. Yavorskyy, M. Oelgemöller, Catalysis Today 2018, 308, 102-118.

- Z. Dong, Z. Wen, F. Zhao, S. Kuhn, T. Noël, Chemical Engineering Science: X 2021, 10.

- aY. Su, K. Kuijpers, V. Hessela, T. Noël, Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2015, 1, 73-81; bK. P. L. Kuijpers, M. A. H. van Dijk, Q. G. Rumeur, V. Hessel, Y. Su, T. Noël, Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2017, 2, 109-115.

- E. G. Moschetta, S. M. Richter, S. J. Wittenberger, ChemPhotoChem 2017, 1, 539-543.

- aG. I. Taylor, Royal Society 1954, 225, 473–477; bG. I. Taylor, Royal Society 1953, 219, 186-203.

- X. Ni, in WO2022013348A1, 2022.

- aaM. R. Mackley, X. Ni, 1991, 46, 3139-3151; bX. Ni, H. Jian, A. W. Fitch, Chemical Engineering Science 2001, 57, 2849-2862; cX. Ni, M. R. Mackley, A. P. Harvey, P. Stonestreet, M. H. I. Baird, N. V. Rama Rao, Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2003, 81, 373-383; dA. W. Dickens, M. R. Mackley, H. R. Williams, 1989, 44, 1471–1479.

- aH. Jian, X. Ni, 2005, 83 1163-1170; bX. Ni, Y. S. Gélicourt, J. Neil, T. Howes, Chemical Engineering Journal 2002, 85, 17-25.

- aG. Jimeno, Y. C. Lee, X. Ni, The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2021, 100, S258-S271; bM. Jiang, X. Ni, Organic Process Research & Development 2019, 23, 882-890.

- NiTech.

- aM. I. Burguete, F. Galindo, R. Gavara, S. V. Luis, M. Moreno, P. Thomas, D. A. Russell, 2008, 8, 37-44; bV. Fabregat., M. I. Burguete., F. Galindo., S. V. Luis., Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2013, 21, 11884–11892.

- aJ. M. Aubry, B. Mandard-Cazin, M. Rougee, R. V. Bensasson, Journal of the American Chemical Society 1995 117, 9159-9164; bW. Adam, M. Prein, Journal of the American Chemical Society 1993, 115, 3766-3767; cM. Bauch, W. Fudickar, T. Linker, Molecules 2021, 26, 804.

- A. Ghogare, G. Greer, Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 9994-10034.

- L. Villén, F. Manjón, D. García-Fresnadillo, G. Orellana, Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2006, 69, 1-9.

- M. A. J. Rodgers, NATO ASI Series A, Vol. 85, Life Sciences, 1984.

- P. R. Ogilby, C. S. Foote, Journal of the American Chemical Society 1983, 105, 3423-3430.

- aE. Gianotti, B. M. Estevão, F. Cucinotta, N. Hioka, M. Rizzi, F. Renò, L. Marchese, An Efficient Rose Bengal Based Nanoplatform for Photodynamic Therapy, Vol. 20, Chemistry : a European journal, 2014; bC. Whitmire, Photosensitizers: Types, Uses and Selected Research, Nova Science Publishers, 2016.

- M. S. Deshpande., V. B. Rale., J. M. Lynch., Enzyme and Microbial Technology 1992, 14, 514-527.

- Y. L. Wong, J. M. Tobin, Z. Xua, F. Vilela, Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 18677-18686.

- K. Zhang, D. Kopetzki, P. H. Seeberger, M. Antonietti, F. Vilela, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2013, 52, 1432-1436.

- K. S. Elvira, R. C. R. Wootton, N. M. Reis, M. R. Mackley, A. J. deMello, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 2013, 1.

- aJ. Shen, R. Roman Steinbach, J. Tobin, M. M. Nakata, M. Bower, M. R. S. McCoustra, H. Bridle, V. Arrighi, F. Vilela, Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2016, 193, 226-233; bC. G. Thomson, C. M. S. Jones, G. Rosair, D. David Ellis, J. M. Hueso, A. L. Lee, F. Vilela, Journal of Flow Chemistry 2020, 10, 327-345.

- S. Hoops, S. Sahle, R. Gauges, C. Lee, J. Pahle, N. Simus, M. Singhal, L. Xu, P. Mendes, U. Kummer, Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 3067-3074.

- aS. Alofi, O’Rourke., C. Mills, Photochem Photobiol Sci 2022, 21; bV. L. Luke, L. V. , S. S. Rickenbach, T. M. McCormick, Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2019, 378, 131-135.

- P. R. Erickson, K. J. Moor, J. J. Werner, D. E. Latch, W. A. Arnold, K. McNeill, Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 9170-9178.

- R. M. Hockey, J. M. Nouri, Chemical Engineering Science 1996, 51, 4405-4421.

- J. Zhao, W. Wu, J. Suna, S. Guo, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5323-5351.

- aW. R. Midden, S. Y. Wang, American Chemical Society 1983, 105, 13; bM. O. Sunday, H. Sakugawa, Science of The Total Environment 2020, 746.

- M. S. N. Oliveira, X. Ni, AIChE Journal 2004, 50, 3019-3033.

- S. M. R. Ahmed, A. N. Phan, A. P. Harvey, Chemical Engineering & Technology 2017, 40, 907-914.

- C. G. Thomson, C. M. S. Jones, G. Rosair, D. Ellis, J. Marques-Hueso, A. L. Lee, F. Vilela, Journal of Flow Chem 2020, 10.

| Run number | Chloroform (mL) | α-terpinene (mL) | Number of repeated runs |

| 1 | 397.88 | 2.12 | 1 |

| 2 | 395.77 | 4.23 (default) | 2 |

| 3 | 393.00 | 7.00 | 2 |

| 4 | 391.53 | 8.47 | 3 |

| 5 | 390.00 | 10.00 | 2 |

| 6 | 383.10 | 16.90 | 2 |

| 7 | 374.50 | 25.50 | 3 |

| α-terpinene (ml) | Efficiency of 1O2 utilization (%) | Efficiency of photo conversion (%) |

| 7 | 10.7 | 0.10 |

| 4.23 | 14.6 | 0.07 |

| 2.12 | 4.9 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).