Submitted:

12 December 2023

Posted:

13 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection and selection of phenotypically extreme animals

2.2. SNP genotyping and GWAS analysis

2.3. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

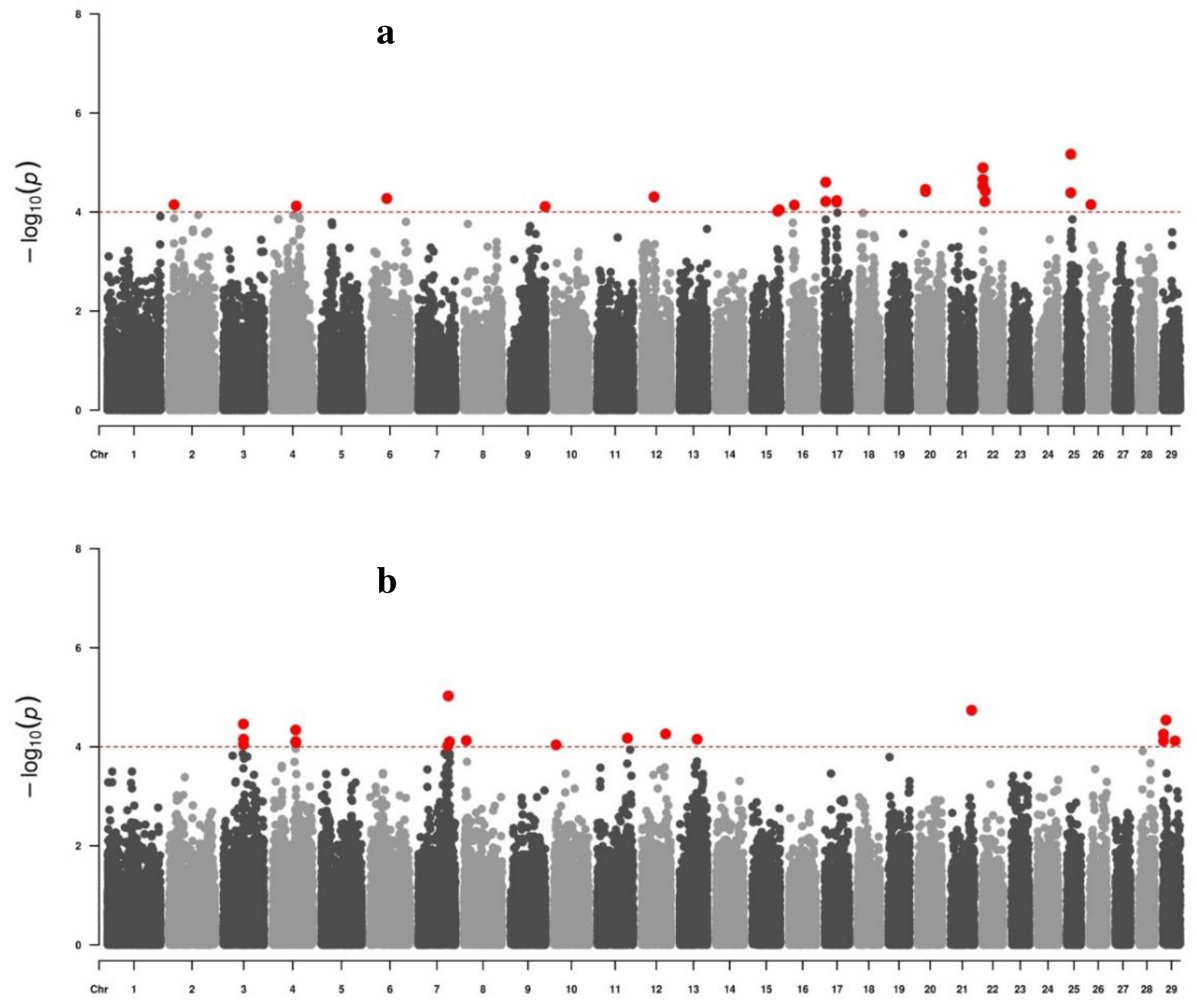

3.2. Genome-wide associations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gharbi, M.; Aziz, M.D.; Khawla, E.; Al-Hosary, A.A.T.; Ayadi, O.; Salih Diaeldin, A.; et al. Current status of tropical theileriosis in Northern Africa: A review of recent epidemiological investigations and implications for control. Transbound Emerg Dis 2020, 67, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, V.; Nigam, R.; Bachan, R.; Sudan, V.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Shankar, D.; et al. Oxidative and haemato-biochemical alterations in theileriosis affected cattle from semi-arid endemic areas of India. Indian J Anim Sci 2017, 87, 846–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Akbar, H.; Rashid, I.; Saeed, K.; Ahmad, L.; Ahmad, A.S.; et al. Economic Significance of Tropical Theileriosis on a Holstein Friesian Dairy Farm in Pakistan. J Parasitol 2018, 104, 310–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyma, K.P.; Gupta, J.P.; Singh, V. Breeding strategies for tick resistance in tropical cattle: a sustainable approach for tick control. J Parasit Dis 2015, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, C. Bovine theileriosis in Australia: a decade of disease. Microbiol Aust 2017, 15–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaija, P.D.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Contreras, M.; Kirunda, H.; Fuente J de, la. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases Cattle ticks and tick-borne diseases: a review of Uganda’s situation. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2021, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, W.I. The aetiology, pathogenesis and control of theileriosis in domestic animals Diseases caused by Theileria species. Rev Sci técnica 2015, 34, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, D.; Gomes, J.; Coelho, A.C.; Carolino, I. Genetic Resistance of Bovines to Theileriosis. Animals 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzemo, W.D.; Thekisoe, O.; Vudriko, P. Development of acaricide resistance in tick populations of cattle: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahbahani, H.; Hanotte, O. Genetic resistance: tolerance to vector-borne diseases and the prospects and challenges of genomics. Rev Sci Tech - Off Int des épizooties 2015, 34, 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, E.J.; Jensen, K. Resistance and susceptibility to a protozoan parasite of cattle — Gene expression differences in macrophages from different breeds of cattle. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2007, 120, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Gaur, G.K.; Gandham, R.K.; Panigrahi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Saravanan, B.C.; et al. Global gene expression profile of peripheral blood mononuclear cells challenged with Theileria annulata in crossbred and indigenous cattle. Infect Genet Evol 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazifi, S.; Razavi, S.M.; Reiszadeh, M.; Esmailnezhad, Z.; Ansari-Lari, M.; Hasanshahi, F. Evaluation of the resistance of indigenous Iranian cattle to Theileria annulata compared with Holstein cattle by measurement of acute phase proteins. Comp Clin Path 2010, 19, 155–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, E.J.; Preston, P.M.; Springbett, A.; Craigmile, S.; Kirvar, E.; Wilkie, G.; et al. Bos taurus and Bos indicus (Sahiwal) calves respond differently to infection with Theileria annulata and produce markedly different levels of acute phase proteins. Int J Parasitol 2005, 35, 337–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabor, A.E.; Santos, I.K.F.D.M.; Boulanger, N. Editorial: Ticks and Host Immunity – New Strategies for Controlling Ticks and Tick-Borne Pathogens. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 10–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, P.I.; Guimarães, S.E.F.; Verardo, L.L.; Azevedo, A.L.S.; Vandenplas, J.; Soares, A.C.C.; et al. Genome-wide association studies for tick resistance in Bos taurus × Bos indicus crossbred cattle: A deeper look into this intricate mechanism. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 11020–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, V.; Madder, M.; Labuschagne, M.; Callaby, R.; Zhao, R.; Djikeng, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of heritability estimates and genome-wide association for tick-borne haemoparasites in African cattle. Front Genet 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapholi, N.O.; Maiwashe, A.; Matika, O.; Riggio, V.; Bishop, S.C.; Macneil, M.D.; et al. Genome-wide association study of tick resistance in South African Nguni cattle. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2016, 7, 487–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, L.; Prakapenka, D.; Vanraden, P.M.; Cole, J.B.; Da, Y. A Large-Scale Genome-Wide Association Study in U. S. Holstein Cattle. Front Genet 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsson, M. Genomics in animal breeding from the perspectives of matrices and molecules. Hereditas 2023, 160, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, D.; Dutra, A.P.; Carolino, N.; Gomes, J.; Coelho, A.C.; Espadinha, P.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Theileria annulata Infection in Two Bovine Portuguese Autochthonous Breeds. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- República D da. Portaria n.o 54-C/2023. Portugal; 2023 p. 332-(75)-332-(146).

- Rodrigues, F.T. Estrutura demográfica e genética da raça bovina Alentejana. Escola Superior Agrária de Santarém; 2021.

- Carolino, N.; Vitorino, A.; Pais, J.; Henriques, N.; Silveira, M.; Vicente, A. Genetic Diversity in the Portuguese Mertolenga Cattle Breed Assessed by Pedigree Analysis. Animals 2020, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Soares, R.; Costa, P.; Amaro, A.; Inácio, J.; Gomes, J. Revisiting the Tams1-encoding gene as a species-specific target for the molecular detection of Theileria annulata in bovine blood samples. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2013, 4, 72–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007, 81, 559–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsik, C.; Unni, D.; Diesh, C.; Tayal, A.; Emery, M.; Nguyen, H.; et al. Bovine Genome Database: new tools for gleaning function from the Bos taurus genome [Internet]. Nucleic Acids Res; 2016. Available from: http://bovinemine-v16.rnet.missouri.edu:8080/bovinemine/begin.do.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

- Cao, M.; Shi, L.; Peng, P.; Han, B.; Liu, L.; Lv, X.; et al. Determination of genetic effects and functional SNPs of bovine HTR1B gene on milk fatty acid traits. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.P.; Yang, Z.; Weiss, R.B.; Wilson, D.J.; Rood, K.A.; Liu, G.E.; et al. A genome-wide association study for mastitis resistance in phenotypically well-characterized Holstein dairy cattle using a selective genotyping approach. Immunogenetics 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sahana, G.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Lund, M.S. Genome-wide association study for calving traits in Danish and Swedish Holstein cattle. J Dairy Sci 2011, 94, 479–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.O.; Kizilkaya, K.; Garrick, D.J.; Fernando, R.L.; Reecy, J.M.; Weber, R.L.; et al. Bayesian genome-wide association analysis of growth and yearling ultrasound measures of carcass traits in Brangus heifers. J Anim Sci 2012, 90, 3398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, R.G.; Garrick, D.J.; Reecy, J.M. Network Analysis Reveals Putative Genes Affecting Meat Quality in Angus Cattle. Front Genet 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanno, E.C.; Chen, L.; Ismail, M.K.A.; Crowley, J.J.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Genome-wide association scan for heterotic quantitative trait loci in multi-breed and crossbred beef cattle. Genet Sel Evol 2018, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, B.; Poulsen, N.A.; Gebreyesus, G.; Larsen, L.B. Estimation of genetic parameters and detection of chromosomal regions affecting the major milk proteins and their post translational modifications in Danish Holstein and Danish Jersey cattle. BMC Genet 2016, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrode, R.; Ojango, J.M.K.; Okeyo, A.M.; Mwacharo, J.M. Genomic Selection and Use of Molecular Tools in Breeding Programs for Indigenous and Crossbred Cattle in Developing Countries: Current Status and Future Prospects. Front Genet 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, M.D.R.S. Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology. Int J Radiat Oncol - Biol - Phys 2004, 59, 21–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamouchi, M.; Philipp, S.; Flockerzi, V.; Wissenbach, U.; Mamin, A.; Raeymaekers, L.; et al. Properties of heterologously expressed hTRP3 channels in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Physiol 1999, 518, 345–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.A.; Xu, A.; Ishikawa, H.O.; Irvine, K.D. Report Modulation of Fat:Dachsous Binding by the Cadherin Domain Kinase Four-Jointed. Curr Biol 2010, 20, 811–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, H.; Brass, A.; Obara, I.; Anderson, S.; Archibald, A.L.; Bradley, D.G.; et al. Genetic and expression analysis of cattle identifies candidate genes in pathways responding to Trypanosoma congolense infection. PNAS 2011, 108, 9304–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares-silva, M.; Diniz, F.F.; Gomes, G.N.; Bahia, D. The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway: Role in Immune Evasion by Trypanosomatids. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, M.; Mceligot, H.A.; Mutua, V.N.; Walsh, P.; Chaigneau, F.R.C.; Gershwin, L.J. Analysis of lung transcriptome in calves infected with Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus and treated with antiviral and/or cyclooxygenase inhibitor. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümer, K.Ç.; Kızıl, M. Circulatory cytokines during the piroplasm stage of natural Theileria annulata infection in cattle. Parasite Immunol 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyda, J.; Mielczarek, M.; Fr, M.; Minozzi, G.; Williams, J.L.; Wojdak-Maksymiec, K. The genetic background of clinical mastitis in Holstein- Friesian cattle. Animal 2019, 13, 2156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Hu, N.; Zhang, J.; Yi, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. bta-miR-2904 inhibits bovine viral diarrhea virus replication by targeting viral-infection-induced autophagy via ATG13. Arch Virol 2023, 168, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilev, V.B.; Donis, R.O. Bovine viral diarrhea virus-induced apoptosis correlates with increased intracellular viral RNA accumulation. Virus Res 2000, 69, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qu, K.; Ma, Z.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, F.; Shen, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Genomic Loci Associated With Neurotransmitter Concentration in Cattle. Front Genet 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.; Kemler, R. Protocadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2022, 14, 557–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI. OR1S8 olfactory receptor family 1 subfamily S member 8 [Bos taurus (cattle)] [Internet]. National Library of Medicine. 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/?term=107133203.

- Favia, M.; Gerbino, A.; Notario, E.; Tragni, V.; Sgobba, M.N.; Elena, M.; et al. The Non-Gastric H+/K+ ATPase (ATP12A) Is Expressed in Mammalian Spermatozoa. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; An, B.; Du, L.; Chang, T.; Liang, M.; Yang, B.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Growth Curve Parameters in Chinese Simmental Beef Cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Møller, V.L.L.; Groote, E.D.; Bojsen-møller, K.N.; Davey, J.; Henríquez-olguin, C.; et al. Mechanisms involved in follistatin-induced hypertrophy and increased insulin action in skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 1241–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianti, I. Molecular genetics of cattle muscularity. University of Adelaide; 2010.

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Wu, M.; Ma, X.; Liu, Z. Genome-Wide Specific Selection in Three Domestic Sheep Breeds. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.; Lee, M.; Ryoo, S.; Seo, S.; Choi, I. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms related to heifer fertility in Hanwoo (Korean cattle). Anim Biotechnol 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Qi, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies loci and candidate genes for meat quality traits in Simmental beef cattle. Mamm Genome 2016. [CrossRef]

- Thyrion, L.; Portelli, J.; Raedt, R.; Glorieux, G.; Larsen, L.E.; Sprengers, M.; et al. Disruption, but not overexpression of urate oxidase alters susceptibility to pentylenetetrazole- and pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 146–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, A.; Singla, L.D.; Sharma, A.; Mandeep, S.B.; Filia, G.; Kaur, P. Molecular epidemiology, risk factors and hematochemical alterations induced by Theileria annulata in bovines of Punjab (India). Acta Parasitol 2015, 60, 378–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurima, K.; Ebrahim, S.; Pan, B.; Holt, J.R.; Griffith, A.J.; Kachar, B. TMC1 and TMC2 Localize at the Site of Mechanotransduction in Mammalian Inner Ear Hair Article TMC1 and TMC2 Localize at the Site of Mechanotransduction in Mammalian Inner Ear Hair Cell Stereocilia. CellReports 2015, 12, 1606–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurima, K.; Yang, Y.; Sorber, K.; Griffith, A.J. Characterization of the transmembrane channel-like (TMC) gene family: functional clues from hearing loss and epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Genomics 2003, 82, 300–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, S.; Trujano-chavez, M.Z.; Gallegos-s, J.; Becerril-p, M.; Cadena-villegas, S.; Cortez-romero, C. Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes. Animals 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Malvisi, M.; Palazzo, F.; Morandi, N.; Lazzari, B.; Williams, L.J.; Pagnacco, G.; et al. Responses of Bovine Innate Immunity to Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis Infection Revealed by Changes in Gene Expression and Levels of MicroRNA. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M.P.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Wolf, V.; Laithier, C.; Jabri, M.E.; Michenet, A.; et al. Sequence-based GWAS, network and pathway analyses reveal genes co - associated with milk cheese - making properties and milk composition in Montbéliarde cows. Genet Sel Evol 2019, 51, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, R.M.; Goldkamp, A.K.; Patel, B.N.; Hagen, D.E.; Joel, E.; Moreno, S.; et al. Identification of large offspring syndrome during pregnancy through ultrasonography and maternal blood transcriptome analyses. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Raey, M.; Geshi, M.; Somfai, T.; Kaneda, M.; Hirako, M.; Abdel-Ghaffar, A.E.; et al. Evidence of Melatonin Synthesis in the Cumulus Oocyte Complexes and its Role in Enhancing Oocyte Maturation In Vitro in Cattle. Mol Reprod Dev 2011, 78, 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haegeman, A.; Williams, J.L.; Law, A.; Zeveren, A.; Van Peelman, L.J. Characterization and mapping of bovine dopamine receptors 1 and 5. Anim Genet 2003, 34, 290–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juszczuk-Kubiak, E.; Flisikowski, K.; Wicinska, K. Nucleotide sequence and variations of the bovine myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) gene promoter in Bos taurus cattle. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38, 1269–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszczuk-kubiak, E.; Wicinska, K.; Starzynski, R.R. Postnatal expression patterns and polymorphism analysis of the bovine myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2C) gene. Meat Sci 2014, 98, 753–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlawat, S.; Choudhary, V.; Kaur, R.; Arora, R.; Sharma, R.; Chhabra, P.; et al. Unraveling the genetic mechanisms governing the host response to bovine anaplasmosis. Gene 2023, 877, 147532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Alentejana | Mertolenga | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

T. annulata infection |

Positive | 30 (31.25%) | 48 (50.00%) |

| Negative | 66 (68.75%) | 48 (50.00%) | |

| Age | Youngest animal | 8 months | 1 month |

| Oldest animal | 14 years and 2 months | 8 years and 5 months | |

| Sex | Male | 5 (5.20%) | 3 (3.10%) |

| Female | 91 (94.8%) | 93 (96.90%) | |

| Number of farms | 14 | 13 | |

| Alentejana Breed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Chr | Position/ Variant |

p-value | A1 | BETA | Protective allele | Reference allele/ alternative allele |

| rs29016369 | 25 | 11866965 Intergenic |

6,80x10-6 | T | 2,045 | C | C/T |

| rs382748014 | 22 | 1175689 Intergenic |

1,28x10-5 | A | 2,190 | G | A/G |

| rs136686350 | 22 | 1079338 Intron |

2,19x10-5 | T | 2,162 | C | C/T |

| rs42824138 | 17 | 3176994 Intron |

2,50x10-5 | A | 1,767 | G | A/G |

| rs42349624 | 22 | 1012010 Intron |

2,97x10-5 | C | 2,017 | T | T/C |

| rs110733319 | 22 | 1130073 Intergenic |

2,97x10-5 | T | 2,017 | G | G/T |

| rs41580257 | 20 | 22411430 Intron |

3,48x10-5 | A | 2,100 | G | G/A |

| rs109220983 | 22 | 8175191 Intergenic |

3,77x10-5 | C | 2,152 | T | T/C |

| rs110456301 | 20 | 22270511 Intergenic |

3,85x10-5 | T | 1,842 | G | T/G |

| rs136677596 | 20 | 22278044 Upstream gene variant |

3,85x10-5 | T | 1,842 | C | T/C |

| rs134209239 | 25 | 11945164 Intergenic |

4,08x10-5 | C | 1,751 | T | C/T |

| rs110136753 | 12 | 36966751 Intergenic |

4,94x10-5 | T | 1,621 | C | T/C |

| rs137404731 | 6 | 49298093 Intergenic |

5,33x10-5 | A | -2,453 | A | G/A |

| rs135649048 | 17 | 35855903 Intergenic |

5,89x10-5 | T | 1,481 | C | C/T |

| rs110248505 | 17 | 3089327 Intron |

6,12x10-5 | A | 1,688 | G | A/G |

| rs378877063 | 22 | 6853730 Intron |

6,12x10-5 | T | 1,937 | C | C/T |

| rs133854848 | 17 | 35658672 Intergenic |

6,29x10-5 | A | 1,615 | G | G/A |

| rs42082138 | 26 | 4547983 Intergenic |

7,09x10-5 | A | -1,996 | A | G/A |

| rs42238085 | 2 | 14716248 Intron |

7,11x10-5 | A | -1,701 | A | G/A |

| rs134193812 | 16 | 15787680 Intergenic |

7,24x10-5 | C | -1,530 | C | C/T |

| rs137244944 | 4 | 70697022 Upstream gene variant |

7,53x10-5 | G | -1,827 | G | G/A |

| rs41657708 | 9 | 103006480 Intergenic |

7,74x10-5 | T | -1,743 | T | C/T |

| rs136575474 | 15 | 81387903 Intron |

8,99x10-5 | G | 1,340 | T | G/T |

| rs41782203 | 15 | 76586569 Intron |

9,60x10-5 | A | 1,656 | G | G/A |

| Mertolenga Breed | |||||||

| rs41625107 | 7 | 89404622 Intergenic |

9,40x10-6 | G | 1,584 | A | A/G |

| rs385061716 | 21 | 62178639 Intergenic |

1,82x10-5 | T | 1,776 | C | C/T |

| rs137077511 | 29 | 9372082 Intergenic |

2,88x10-5 | T | 1,638 | G | T/G |

| rs210844007 | 3 | 59423141 Intron |

3,46x10-5 | G | 1,580 | A | A/G |

| rs136003479 | 4 | 68835630 Downstream gene variant |

4,55x10-5 | A | 1,330 | G | G/A |

| rs42966583 | 12 | 71327190 Intron |

5,51x10-5 | A | -1,378 | A | A/C |

| rs109210201 | 29 | 1806321 Intergenic |

5,53x10-5 | C | 1,784 | A | C/A |

| rs110183014 | 11 | 89708117 Intergenic |

6,69x10-5 | A | -1,494 | A | G/A |

| rs43338206 | 3 | 59696522 Intron |

7,01x10-5 | T | 1,532 | C | T/C |

| rs110582951 | 13 | 52653719 Intergenic |

7,05x10-5 | G | 1,397 | A | G/A |

| rs41588323 | 8 | 7368884 Intergenic |

7,46x10-5 | C | 2,140 | T | T/C |

| rs42492357 | 29 | 1982095 Intergenic |

7,59x10-5 | G | 1,490 | A | A/G |

| rs41651830 | 29 | 36432759 Upstream gene variant |

7,59x10-5 | C | 1,490 | T | T/C |

| rs109072096 | 4 | 68841016 Upstream and Downstream gene variant |

7,84x10-5 | A | 1,246 | G | G/A |

| rs109619291 | 7 | 92837313 Intergenic |

7,91x10-5 | T | 1,301 | C | C/T |

| AX-212327028* | 4 | 69412929 * |

8,15x10-5 | C | 2,039 | A | A/C |

| rs43338222 | 3 | 59690463 Missense variant and intron |

9,01x10-5 | T | 1,508 | C | C/T |

| rs110062605 | 10 | 6197570 Intergenic |

9,14x10-5 | A | 1,340 | C | C/A |

| rs133541497 | 7 | 88255064 Intron |

9,41x10-5 | A | -1,278 | A | C/A |

| rs137232658 | 7 | 88256048 Intron |

9,41x10-5 | G | -1,278 | G | A/G |

| Marker | Chr | QTL ID | QTL Trait | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs43338206 | 3 | 22779 | Average daily gain B. taurus | [32] |

| rs41625107 | 7 | 151659 | Muscle carnosine content | [33] |

| rs41625107 | 7 | 151673 | Muscle creatine content | [33] |

| rs41625107 | 7 | 164401 | Body weight (birth) | [34] |

| rs41625107 | 7 | 164580 | Longissimus muscle area | [34] |

| rs41588323 | 8 | 151760 | Muscle creatinine content | [33] |

| rs137077511 | 29 | 116645 | Milk glycosylated kappa-casein percentage | [35] |

| Marker | p-value | Chr | Position | Gene | Gene Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs29016369 | 6,80x10-6 | 25 | 11866965 | SHISA9 - shisa family member 9 | 11633241-11647753 |

| 11633245-12158399 | |||||

| rs382748014 | 1,28x10-5 | 22 | 1175689 | EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor | 905960-1121554 |

| RF00003 | 1258027-1258168 | ||||

| rs136686350 | 2,19x10-5 | 22 | 1079338 | EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor | 905960-1121554 |

| rs42824138 | 2,50x10-5 | 17 | 3176994 | ENSBTAG00000024545 | 3009649-3332773 |

| DCHS2 - dachsous cadherin-related 2 | 3137604-3333575 | ||||

| rs42349624 | 2,97x10-5 | 22 | 1012010 | EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor | 899974-1121540 |

| 905960-1121554 | |||||

| rs110733319 | 2,97x10-5 | 22 | 1130073 | EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor | 899974-1121540 |

| 905960-1121554 | |||||

| RF00003 | 1258027-1258168 | ||||

| rs41580257 | 3,48x10-5 | 20 | 22411430 | MAP3K1 - mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 | 22340163-22417428 |

| rs109220983 | 3,77x10-5 | 22 | 8175191 | ENSBTAG00000051119 | 8163685-8167126 |

| RF00026 | 8222734-8222838 | ||||

| rs110456301 | 3,85x10-5 | 20 | 22270511 | LOC112443032 - uncharacterized | 22159612-22183599 |

| MIER3 - MIER family member 3 | 22279228-22305654 | ||||

| rs136677596 | 3,85x10-5 | 20 | 22278044 | LOC112443032 - uncharacterized | 22159612-22183599 |

| MIER3 - MIER family member 3 | 22279228-22305654 | ||||

| rs134209239 | 4,08x10-5 | 25 | 11945164 | SHISA9 - shisa family member 9 | 11633245-12158399 |

| rs110136753 | 4,94x10-5 | 12 | 36966751 | ATP12A - ATPase H /K transporting non-gastric alpha2 subunit | 36642635-36664187 |

| ENSBTAG00000049928 | 37397698-37398144 | ||||

| rs137404731 | 5,33x10-5 | 6 | 49298093 | RF00156 | 49020641-49020774 |

| RF00019 | 49412387-49412498 | ||||

| rs135649048 | 5,89x10-5 | 17 | 35855903 | TRPC3 - transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily C member 3 | 35728366-35800211 |

| FSTL5 - follistatin like 5 | 36260758-37189201 | ||||

| rs110248505 | 6,12x10-5 | 17 | 3089327 | LOC107133268 - protocadherin-16-like | 3009266-3011829 |

| ENSBTAG00000024545 | 3009649-3332773 | ||||

| rs378877063 | 6,12x10-5 | 22 | 6853730 | CMTM7 - Bos taurus CKLF like MARVEL transmembrane domain containing 7 | 6821672-6869727 |

| 6821790-6869725 | |||||

| rs133854848 | 6,29x10-5 | 17 | 35658672 | LOC782754 - mpv17-like protein 2 | 35638835-35639137 |

| TRPC3 - transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily C member 3 | 35728366-35800211 | ||||

| rs42082138 | 7,09x10-5 | 26 | 4547983 | PCDH15 - protocadherin related 15 | 4509270-5569299 |

| rs42238085 | 7,11x10-5 | 2 | 14716248 | SSFA2 - sperm specific antigen 2 | 14654230-14750696 |

| ITPRID2 - Bos taurus ITPR interacting domain containing 2 | 14654230-14751034 | ||||

| rs134193812 | 7,24x10-5 | 16 | 15787680 | BRINP3 - BMP/retinoic acid inducible neural specific 3 | 15141936-15631140 |

| RF00001 | 16102665-16102785 | ||||

| rs137244944 | 7,53x10-5 | 4 | 70697022 | C4H7orf31 - chromosome 4 C7orf31 homolog | 70687353-70727845 |

| rs41657708 | 7,74x10-5 | 9 | 103006480 | LOC101907681 -uncharacterized | 102848965-102870347 |

| LOC112448098 -uncharacterized | 103129637-103132019 | ||||

| rs136575474 | 8,99x10-5 | 15 | 81387903 | LOC107133203 - olfactory receptor 1S1-like | 81383730-81385093 |

| LOC104974344 - olfactory receptor 10Q1 | 81397109-81421347 | ||||

| rs41782203 | 9,60x10-5 | 15 | 76586569 | ATG13 - Bos taurus autophagy related 13 | 76578054-76620037 |

| 76578279-76620035 |

| Marker | p-value | Chr | Position | Gene | Gene Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs41625107 | 9,40 x10-6 | 7 | 89404622 | MIR3660 - microRNA 3660 | 89558103-89558182 |

| ENSBTAG00000048981 | 88840369-88848347 | ||||

| rs385061716 | 1,82x10-5 | 21 | 62178639 | RF00003 - RNA, U1 small nuclear 85, pseudogene | 62091713-62091865 |

| LOC112443166 - uncharacterized | 62865898-62974123 | ||||

| rs137077511 | 2,88x10-5 | 29 | 9372082 | EED - embryonic ectoderm development | 9265439-9296624 |

| LOC112444890 -uncharacterized | 9426391-9430563 | ||||

| rs210844007 | 3,46x10-5 | 3 | 59423141 | SSX2IP - Bos taurus SSX family member 2 interacting protein | 59398296-59456577 |

| rs136003479 | 4,55x10-5 | 4 | 68835630 | RF02043 | 68836226-68836391 |

| rs42966583 | 5,51x10-5 | 12 | 71327190 | ENSBTAG00000026070 | 71263913-71411435 |

| LOC107131273 - multidrug resistance-associated protein 4-like | 71265415-71400436 | ||||

| rs109210201 | 5,53x10-5 | 29 | 1806321 | SLC36A4 - solute carrier family 36 member 4 | 1701573-1743386 |

| MTNR1B - melatonin receptor 1B | 1901714-1916511 | ||||

| rs110183014 | 6,69x10-5 | 11 | 89708117 | RF00017 - RNA, 7SL, cytoplasmic 825, pseudogene | 89685923-89686207 |

| ENSBTAG00000052434 | 89823864-89861691 | ||||

| rs43338206 | 7,01x10-5 | 3 | 59696522 | UOX - Bos taurus urate oxidase | 59636716-59736408 |

| DNASE2B - deoxyribonuclease 2 beta | 59681735-59700078 | ||||

| RPF1 - ribosome production factor 1 homolog | 59600697-59617167 | ||||

| rs110582951 | 7,05x10-5 | 13 | 52653719 | TMC2 - transmembrane channel like 2 | 52539174-52640959 |

| SNRPB - small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptides B and B1 | 52666459-52675562 | ||||

| rs41588323 | 7,46x10-5 | 8 | 7368884 | ENSBTAG00000039873 | 7325501-7331864 |

| TRNAC-GCA - tRNA-Cys | 7430900-7430971 | ||||

| rs42492357 | 7,59x10-5 | 29 | 1982095 | MTNR1B - melatonin receptor 1B | 1901714-1916511 |

| FAT3 - FAT atypical cadherin 3 | 1991657-2638923 | ||||

| rs41651830 | 7,59x10-5 | 29 | 36432759 | ZBTB44 - zinc finger and BTB domain containing 44 | 36401292-36460165 |

| 36408247-36429241 | |||||

| rs109072096 | 7,84x10-5 | 4 | 68841016 | RF02041 | 68840319-68840692 |

| RF02040 | 68842022-68842077 | ||||

| rs109619291 | 7,91x10-5 | 7 | 92837313 | ENSBTAG00000054282 | 92782983-92822683 |

| LOC100848699 -uncharacterized | 92887690-92904398 | ||||

| AX-212327028* | 8,15x10-5 | 4 | 69412929 | RF00100 | 69383582-69383863 |

| LOC112446335 -uncharacterized | 69487699-69491861 | ||||

| rs43338222 | 9,01x10-5 | 3 | 59690463 | DNASE2B - deoxyribonuclease 2 beta | 59681735-59700078 |

| 59681727-59699694 | |||||

| rs110062605 | 9,14x10-5 | 10 | 6197570 | DRD1 - Bos taurus dopamine receptor D1 | 5715882-5718113 |

| LOC112448549 -uncharacterized | 6357822-6363522 | ||||

| rs133541497 | 9,41x10-5 | 7 | 88255064 | MEF2C - myocyte enhancer factor 2C | 88250023-88407702 |

| rs137232658 | 9,41x10-5 | 7 | 88256048 | MEF2C - myocyte enhancer factor 2C | 88250023-88407702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).